Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Matching Hypothesis

The matching hypothesis is a theory of interpersonal attraction which argues that relationships are formed between two people who are equal or very similar in terms of social desirability. This is often examined in the form of level of physical attraction. The theory suggests that people assess their own value and then make ‘realistic choices’ by selecting the best available potential partners who are also likely to share this same level of attraction.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Example Answers for Relationships: A Level Psychology, Paper 3, June 2019 (AQA)

Exam Support

Relationships: Physical Attractiveness

Study Notes

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Matching Hypothesis

Matching hypothesis definition.

The matching hypothesis refers to the proposition that people are attracted to and form relationships with individuals who resemble them on a variety of attributes, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity, and education level), personality traits, attitudes and values, and even physical attributes (e.g., attractiveness).

Background and Importance of Matching Hypothesis

Evidence for Matching Hypothesis

There is ample evidence in support of the matching hypothesis in the realm of interpersonal attraction and friendship formation. Not only do people overwhelmingly prefer to interact with similar others, but a person’s friends and associates are more likely to resemble that person on virtually every dimension examined, both positive and negative.

The evidence is mixed in the realm of romantic attraction and mate selection. There is definitely a tendency for men and women to marry spouses who resemble them. Researchers have found extensive similarity between marital partners on characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, education level, socioeconomic status, religion, and physical attractiveness as well as on a host of personality traits and cognitive abilities. This well-documented tendency for similar individuals to marry is commonly referred to as homogamy or assortment.

The fact that people tend to end up with romantic partners who resemble them, however, does not necessarily mean that they prefer similar over dissimilar mates. There is evidence, particularly with respect to the characteristic of physical attractiveness, that both men and women actually prefer the most attractive partner possible. However, although people might ideally want a partner with highly desirable features, they might not possess enough desirable attributes themselves to be able to attract that individual. Because people seek the best possible mate but are constrained by their own assets, the process of romantic partner selection thus inevitably results in the pairing of individuals with similar characteristics.

Nonetheless, sufficient evidence supports the matching hypothesis to negate the old adage that “opposites attract.” They typically do not.

References:

- Berscheid, E., & Reis, H. T. (1998). Attraction and close relationships. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 193-281). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kalick, S. M., & Hamilton, T. E. (1996). The matching hypothesis re-examined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 673-682.

- Murstein, B. I. (1980). Mate selection in the 1970s. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 777-792.

Open Education Sociology Dictionary

matching hypothesis

Table of Contents

Definition of Matching Hypothesis

( noun ) The theory that people select romantic and sexual partners who have similar statuses such as physical attraction and social class.

Matching Hypothesis Pronunciation

Pronunciation Usage Guide

Syllabification : match·ing hy·poth·e·sis

Audio Pronunciation

Phonetic Spelling

- American English – /mAch-ing hie-pAHth-uh-suhs/

- British English – /mAch-ing hie-pOth-i-sis/

International Phonetic Alphabet

- American English – /ˈmæʧɪŋ haɪˈpɑθəsəs/

- British English – /ˈmæʧɪŋ haɪˈpɒθɪsɪs/

Usage Notes

- Plural: matching hypotheses

- A type of homogamy.

- Also called matching phenomenon .

Additional Information

- Sex and Gender Resources – Books, Journals, and Helpful Links

- Word origin of “match” and “hypothesis” – Online Etymology Dictionary: etymonline.com

- Rosenblum, Karen Elaine, and Toni-Michelle Travis. 2016. The Meaning of Difference: American Constructions of Race, Sex and Gender, Social Class, Sexual Orientation, and Disability . 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Related Terms

- ascribed status

- discrimination

Works Consulted

Branscombe, Nyla R., and Robert A. Baron. 2017. Social Psychology . 14th ed. Harlow, England: Pearson.

Encyclopædia Britannica. (N.d.) Britannica Digital Learning . ( https://britannicalearn.com/ ).

Wikipedia contributors. (N.d.) Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia . Wikimedia Foundation. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/ ).

Cite the Definition of Matching Hypothesis

ASA – American Sociological Association (5th edition)

Bell, Kenton, ed. 2016. “matching hypothesis.” In Open Education Sociology Dictionary . Retrieved May 16, 2024 ( https://sociologydictionary.org/matching-hypothesis/ ).

APA – American Psychological Association (6th edition)

matching hypothesis. (2016). In K. Bell (Ed.), Open education sociology dictionary . Retrieved from https://sociologydictionary.org/matching-hypothesis/

Chicago/Turabian: Author-Date – Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition)

Bell, Kenton, ed. 2016. “matching hypothesis.” In Open Education Sociology Dictionary . Accessed May 16, 2024. https://sociologydictionary.org/matching-hypothesis/ .

MLA – Modern Language Association (7th edition)

“matching hypothesis.” Open Education Sociology Dictionary . Ed. Kenton Bell. 2016. Web. 16 May. 2024. < https://sociologydictionary.org/matching-hypothesis/ >.

Relationship Theories Revision Notes

Will Goulder

Psychology A-level Teacher

BSc (Hons), Psychology

Psychology and performing arts teacher in Canterbury. Deputy head of language and arts, and digital technology leader.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

What do the examiners look for?

- Accurate and detailed knowledge

- Clear, coherent, and focused answers

- Effective use of terminology (use the “technical terms”)

In application questions, examiners look for “effective application to the scenario,” which means that you need to describe the theory and explain the scenario using the theory making the links between the two very clear. If there is more than one individual in the scenario you must mention all of the characters to get to the top band.

Difference between AS and A level answers

The descriptions follow the same criteria; however, you have to use the issues and debates effectively in your answers. “Effectively” means that it needs to be linked and explained in the context of the answer.

Read the model answers to get a clearer idea of what is needed.

Exam Paper Advice

In the exam, you will be asked a range of questions on relationships, which may include questions about research methods or using mathematical skills based on research into relationships.

As in Paper One and Two, you may be asked a 16-mark question, which could include an item (6 marks for AO1 Description, 4 marks for AO2 Application, and 6 marks for AO3 Evaluation) or simply to discuss the topic more generally (6 marks AO1 Description and ten marks AO2 Evaluation).

There is no guarantee that a 16-mark question will be asked on this topic, though, so it is important to have a good understanding of all of the different areas linked to the topic.

There will be 24 marks for relationship questions, so you can expect to spend about 30 minutes on this section, but this is not a strict rule.

The evolutionary explanations for partner preferences

The relationship between sexual selection and human reproductive behavior.

Evolutionary approaches state that animals are motivated to select a ‘mate’ with the best possible genes who will best be able to ensure the offspring’s future health and survival.

Anisogamy means two sex cells (or gametes) that are different coming together to reproduce. Men have sperm cells, which can reproduce quickly with little energy expenditure, and once they start being produced, they do not usually stop until the man dies.

Female gametes (eggs or ova) are, in contrast, much less plentiful; they are released in a limited time frame (between puberty and menopause) and require much more energy to produce.

This difference (anisogamy) means that men and women use different strategies when choosing partners.

Inter-sexual Selection

Intersexual selection is the preferred strategy of the female. They value quality over quantity.

Intersexual selection is when one gender makes mate choices based on a specific characteristic of the other gender: e.g., peahens choosing peacocks with larger tails. As a result, peacock tails become larger across the population because peacocks with larger tails will mate more, thus passing these characteristics on.

Females lose more resources than men if they choose a sub-standard partner, so they are pickier about who they select. They are more likely to pick a partner who is genetically fit and willing to offer the maximum resources to raise their offspring (a man who will remain by her side as the child grows to protect them both and potentially provide more children).

Females tend to seek a man who displays physical health characteristics and is a high-status individual who controls resources within the social group. Thus male partners are able to protect, provide and control food and resources. Although this ability may have equated to muscular strength in our evolutionary past, in modern society, it is more likely to relate to occupation, social class, and wealth.

If they have made a good choice, then their offspring will inherit the positive features of their father and are therefore also more likely to be chosen by women or men in the next generation.

Intra-sexual Selection

Intrasexual selection is the preferred strategy of the male. They value quantity over quality. Anisogamy suggests that men’s best evolutionary strategy is to have as many partners as possible.

To succeed, men must compete with other males to present themselves as the most attractive mate, encouraging features such as muscles that indicate to the opposite sex an ability to protect both themselves and their offspring.

Intrasexual selection refers to competition between members of the same sex for access to a mate of the opposite sex. Whatever characteristics led to success in mating will be passed on to the next generation, thus becoming more widespread in the gene pool.

Buss (1989) surveyed over 10,000 adults in 33 countries and found that females reported valuing resource-based characteristics when choosing a male (such as their jobs) whilst men valued good looks and preferred younger partners more than females did.

Although the size and scale of Buss’s work are impressive, his use of questionnaires could lead to social desirability bias, with participants answering in socially desirable ways rather than honestly. Also, 77% of participants were from Western industrial nations, meaning Buss might have been measuring the effects of culture rather than an evolutionary-determined behavior.

Clark and Hatfield (1989) conducted a now infamous study where male and female psychology students were asked to approach fellow students of Florida State University (of the opposite sex) and ask them for one of three things; to go on a date, to go back to their apartment, or to go to bed with them.

About 50% of men and women agreed to the date, but 69% of men agreed to visit the apartment, and 75% agreed to go to bed with them; only 6% of women agreed to go to the apartment, and 0% accepted the more intimate offer.

The evolutionary approach is determinist suggesting that we have little free will in partner choice. However, everyday experience tells us we have some control over our preferences. Evolutionary approaches to mate preferences are socially sensitive in that they promote traditional (sexist) views regarding what are ‘natural’ male and female roles and behaviors.

Gender bias – In today’s society, women are more career orientated and, therefore,, will not look for resourceful partners as much – Evolutionary theory does not apply to modern society.

Finally, the evolutionary theory makes little attempt to explain other types of relationships, e.g., gay and lesbian relationships, and cultural variations in relationships that exist across the world, e.g., arranged marriages.

Factors Affecting Attraction

Self disclosure.

This refers to the extent to which a person reveals thoughts, feelings, and behaviors which they would usually keep private from a potential partner. This increases feelings of intimacy.

In the initial stages of a relationship, couples often seek to learn as much as they can about their new partner and feel that this sharing of information brings them closer together. But can too much sharing scare your partner away? Is not sharing very much information intriguing or frustrating?

Altman and Taylor (1973) identified breadth and depth as important factors of self-disclosure . At the start of a relationship, self-disclosure is likely to cover a range of topics as you seek to explore the key facts about your new partner. “What do you do for work” and “Where did you last go on holiday” but these topics are relatively superficial.

As the relationship develops, people tend to share more detailed and personal information, such as past traumas and desires for the future. If this sharing happens too soon, however, an incompatibility may be found before the other person has reached a suitable level of investment in the relationship. Altman and Taylor referred to this sharing of information as social penetration .

An important aspect of this is the reciprocity of the process; if one person shares more than the other is willing to, there may be a breakdown of trust as one person establishes themselves as more invested than the other.

Aron et al. (1997) found that by providing a list of questions to pairs of people that start with superficial information (Who would be your perfect dinner party guest) and moving over 36 questions to more intimate information (Of all the people in your family, whose death would you find the most disturbing) people grew closer and more intimate as the questions progressed.

Aron’s research also included a four-minute stare at the end of the question sequence, which may have also contributed to the increased intimacy.

Sprecher and Hendrick (2004) observed couples on dates and found a close correlation between the amount of satisfaction each person felt and the overall self-disclosure that occurred between the partners.

However, much of the research into self-disclosure is correlational, which means that a causal relationship cannot be easily determined; in short, it may be that it is the attraction between partners which leads to greater self-disclosure, rather than the sharing of information, that leads to greater intimacy.

Physical attractiveness: including the matching hypothesis

Physical attractiveness is viewed by society as one of the most important factors of relationship formation, but is this view supported by research?

Physical appearance can be seen as a range of indicators of underlying characteristics. Women with a favorable waist-to-hip ratio are seen as attractive because they are perceived to be more fertile (Singh, 2002), and people with more symmetrical features are seen to be more genetically fit.

This is because our genes are designed to make us develop symmetrically, but diseases and infections during physical development can cause these small imperfections and asymmetries (Little and Jones, 2003).

The halo effect is a cognitive bias (mental shortcut) that occurs when a person assumes that a person has positive traits in terms of personality and other features because they have a pleasing appearance.

Dion, Berscheid, and Walster (1972) asked participants to rate photographs of three strangers for a number of different categories, including personality traits such as overall happiness and career success.

When these results were compared to the physical attraction rating of each participant (from a rating of 100 students), the photographs which were rated the most physically attractive were also rated higher on the other positive traits.

Walster et al. proposed The Matching Hypothesis that similar people end up together. The more physically desirable someone is, the more desirable they would expect their partner to be. An individual would often choose to date a partner of approximately their own attractiveness.

The matching hypothesis (Walster et al., 1966) suggests that people realize at a young age that not everybody can form relationships with the most attractive people, so it is important to evaluate their own attractiveness and, from this, partners who are the most attainable.

If a person always went for people “out of their league” in terms of physical attractiveness, they may never find a partner, which would be evolutionarily foolish. This identification of those who have a similar level of attraction, and therefore provide a balance between the level of competition (intra-sexual) and positive traits, is referred to as matching.

Modern dating in society is increasingly visual, with the rise of online dating, particularly using apps such as Tinder.

In Dion et al.’s (1972) study, those who were rated to be the most physically attractive were not rated highly on the statement “Would be a good parent,” which could be seen to contradict theories about inter and intra-sexual selection.

Landy and Aronson (1969) show how the halo effect occurs in other contexts. They found that when victims of crime were perceived to be more attractive, defendants in court cases were more likely to be given longer sentences by a simulated jury.

When the defendants were unattractive, they were more likely to be sentenced by the jury, which supports the idea that we generalize physical attractiveness as an indicator of other, less visual traits such as trustworthiness.

Feingold (1988) conducted a meta-analysis of 17 studies and found a significant correlation between the perceived attractiveness of actual partners rated by independent participants.

Individual differences – Towhey et al. found that some people are less sensitive to physical attractiveness when making judgments of personality and likeability – The effects of physical attractiveness can be moderated by other factors and is not significant.

The Filter Theory

Kerckhoff and Davis (1962) suggested that when selecting partners from a range of those who are potentially available to them (a field of availability), people will use three filters to “narrow down” the choice to those who they have the best chance of a sustainable relationship with.

The filter model speaks about three “levels of filters” which are applied to partners.

The first filter proposed when selecting partners were social demography . Social variables such as age, social background, ethnicity, religion, etc., determine the likelihood of individuals meeting and socializing, which will, in turn, influence the likelihood of a relationship being formed.

We are also more likely to prefer potential partners with whom we share social demography as they are more similar to us, and we share more in common with them in terms of norms, attitudes, and experiences.

The second filter that Kerckhoff and Davis suggested was similarity in attitudes . Psychological variables to do with shared beliefs and attitudes are the best predictor of a relationship becoming stable. Disclosure is essential at this stage to ensure partners really do share genuine similarities.

This was supported by their original 1962 longitudinal study of two groups of student couples (those who had been together for more or less than 18 months).

Over seven months, the couples completed questionnaires based on their views and attitudes, which were then compared for similarities. Kerckhoff and Davis suggested that the similarity of attitudes was the most important factor in the group that had been together for less than 18 months. This is supported by the self-disclosure research described elsewhere on this topic.

The third filter was complementarity which goes a step further than similarity. Rather than having the same traits and attitudes, such as dominance or humor, a partner who complements their spouse has traits that the other lacks. For example, one partner may be good at organization, whilst the other is poor at the organization but very good at entertaining guests.

Kerchoff and Davis found that this level of the filter was the most important for couples who had been together for more than 18 months. This may be the origin of the classic phrase “opposites attract,” though we may add the condition “although not for the first 18 months of the relationship.

This theory may be interpreted as similar to the matching hypothesis but for personality rather than physical traits.

Some stages of this model may now be seen as less relevant; for example, as modern society is much more multicultural and interconnected (by things such as the internet) than in the 1960s, we may now see social demography as less of a barrier to a relationship. This may lead to the criticism that the theory lacks temporal validity.

This lack of temporal validity is supported by Levinger (1978), who, even only 16 years after the study, pointed out that many studies had failed to replicate Karchkoff and Davis’ original findings, although this may be down to methodological issues with operationalizing factor such as the success of a relationship or complementarity of traits.

Again, investigating the second and third levels of the filter theory looks at correlation which cannot easily explain causality. Both Davis and Rusbult (2001) and Anderson et al. (2003) found that people become more similar in different ways the more time that they spend in a relationship together.

So it may be that the relationship leads to an alignment of attitudes and also a greater complementarity as couples assign each other roles: “He does the cooking, and I do the hoovering.”

Theories of Romantic Relationships

Social exchange theory.

This is an economic theory of romantic relationships. Many psychologists believe that the key to maintaining a relationship is that it is mutually beneficial.

Psychologists Thibault and Kelley (1959) proposed the Social Exchange Theory , which stipulates that one motivation to stay in a romantic relationship, and a large factor in its development, is the result of a cost-benefit analysis that people perform, either consciously or unconsciously.

Thibaut and Kelley assume that people try to maximize the rewards they obtain from a relationship and minimize the costs (the minimax principle).

In a relationship, people gain rewards (such as attention from their partner, sex, gifts, and a boost to their self-esteem) and incur costs (paying money for gifts, compromising on how to spend their time or stress).

There is also an opportunity cost in relationships, as time spent with a partner that does not develop into a lasting relationship could have been spent with another partner with better long-term prospects.

How much value is placed on each cost and benefit is subjective and determined by the individual. For example, whilst some people may want to spend as much time as possible with their partner in the early stages of the relationship and see this time together as a reward of the relationship, others may value their space and see extended periods spent together as more of a necessary investment to keep the other person happy.

Thibault and Kelley also identified a number of different stages of a relationship which progress from the sampling stage, where couples experiment with the potential costs and rewards of a relationship through direct or indirect interactions, through the bargaining and commitment stages as negotiations of each partner’s role in the relationship occur.

The rewards and costs are established and become more predictable, and finally arriving at the institutionalization stage, where the couple is settled. The norms of the relationship are heavily embedded.

Comparison Levels (CL) and (CLalt)

The comparison level (CL) in a relationship is a judgment of how much profit an individual is receiving (benefits minus costs). The acceptable CL needed to continue to pursue a relationship changes as a person matures and can be affected by a number of external and internal factors.

External factors may include the media (younger people may want more from a relationship after being socialized by images of romance on films and television), seeing friends and families in relationships (people who have divorced or separated parents may have a different CL to those with parents who are still married), or experiences from prior relationships, which have taught the person to expect more or less from a partner. Internal perceptions of self-worth, such as self-esteem, will directly affect the CL that a person believes they are entitled to in a relationship.

CLalt stands for the Comparison Level for Alternatives and refers to a person’s judgment of if they could be getting fewer costs and greater rewards from another alternative relationship with another partner. Steve Duck (1994) suggested that a person’s CLalt is dependent on the level of reward and satisfaction in their current relationship. If the CL is positive, then the person may not consider the potential benefits of a relationship with another person.

Operationalizing rewards and costs are hugely subjective, making comparisons between people and relationships in controlled settings very difficult. Most studies that are used to support Social Exchange Theory account for this by using artificial procedures in laboratory settings, reducing the external validity of the findings.

Michael Argyle (1987) questions whether it is the CL that leads to dissatisfaction with the relationship or dissatisfaction which leads to this analysis. It may be that Social Exchange Theory serves as a justification for dissatisfaction rather than the cause of it.

Social Exchange Theory ignores the idea of social equity explained by the next relationship theory concerning equality in a relationship – would a partner really feel satisfied in a relationship where they received all of the rewards and their partner incurred all of the costs?

Real-world application – Social Exchange Theory is used in Integrated Behavioural Couples Therapy where couples are taught how to increase the proportion of positive exchanges and decrease negative exchanges – This shows high mundane realism in terms of the practical, real-world application of the theory therefore, SET is really beneficial at improving real relationships.

Equity Theory

This is an economic theory of romantic relationships. Equity means fairness.

Equity Theory (Walster ‘78) is an extension of Social Exchange Theory but argues that rather than simply trying to maximize rewards/minimize losses. Couples will experience satisfaction in their relationship if there is an equal ratio of rewards to losses between both partners: i.e., there is equity/fairness.

If one partner is benefiting from more profit (benefits-costs) than the other, then both partners are likely to feel unsatisfied.

If one partner’s reward: loss ratio is far greater than their partner’s, they may experience guilt or shame (they are giving nothing and getting lots in return).

If one partner’s reward: loss ratio is far lower than their partner’s, they may experience anger or resentment (they are giving a lot and getting little in return).

A partner who feels that they are receiving less profit in an inequitable relationship may respond by either working hard to make the relationship more equitable or by shifting their own perception of rewards and costs to justify the relationship continuing.

Principles of equity theory:

- Distribution – Trade-offs and compensations are negotiated to achieve fairness in a relationship e.g., one partner may cook and the other may clean; each has their own role.

- Dissatisfaction – The greater the perceived inequity, the greater the dissatisfaction e.g., someone who over-benefits in their relationship will feel guilty, and one who under-benefits will feel angry.

- Realignment – The more unfair the relationship feels, the harder the partner will work to restore equity. Or they may revise their perceptions of rewards and costs, e.g., what was once seen as a cost (abuse, infidelity) is now accepted as the norm.

Huseman et al. (1987) suggested that individual differences are an important factor in equity theory. They make a distinction between entitleds who feel that they deserve to gain more than their partner in a relationship and benevolents who are more prepared to invest by working harder to keep their partner happy.

Clark and Mills (2011) argue that we should differentiate between the role of equity in romantic relationships and other types of relationships, such as business or casual, friendly relationships. They found in a meta-analysis that there is more evidence that equity is a deciding factor in non-romantic relationships, the evidence being more mixed in romantic partnerships.

Social Equity Theory does not apply to all cultures; couples from collectivist cultures (where the group needs are more important than those of the individual) were more satisfied when over-benefitting than those from individualistic cultures (where the needs of the individual are more important than those of the individual) in a study conducted by Katherine Aumer-Ryan et al. (2007).

Some cultures have traditions and expectations that one member of a romantic relationship should benefit more from the partnership. The traditional nuclear family, typical in the early to mid-20th century, was patriarchal, and the woman was often expected to contribute to more tasks, such as housework and raising the children, than the man for whom providing money to the family was perceived to be the primary role.

Rusbult’s Investment Model

Rusbult et al.’s (2011) model of commitment in a romantic relationship builds upon the Social Exchange Theory discussed above and proposes that three factors contribute to the level of commitment in a relationship.

Satisfaction level . The sum total of positive and negative emotions experienced and how much each partner fulfills the other’s needs (financial, sexual, etc.)

Investment size . This relates to the number of investments made in the relationship to date in terms of time, money, and effort, which would be lost if the relationship stopped. Investments increase dependency on the relationship due to the costs caused by the loss of what has been invested. Therefore, investments are a powerful influence in preventing relationship breakdown.

Commitment level . This refers to the likelihood the relationship will continue. In new romantic relationships, partners tend to have high levels of commitment as they have (i) high levels of satisfaction, (ii) they would lose a lot if the relationship ended, (iii) they don’t expect any gains, (iv) they tend not to be interested in alternative relationships. However, as the relationship continues, these factors may change, resulting in lower levels of commitment.

Le and Agnew’s (2003) meta-analysis of studies relating to similar investment models found that satisfaction, comparison with alternatives, and investment were all strong indicators of commitment to a relationship. This importance was the same across cultures and genders and also applied to homosexual relationships.

Many of the studies relating to an investment in relationships rely on self-report techniques. Whilst this would be perceived as a less reliable and overly-subjective method in other areas when looking at the amount an individual feels they are committed to a relationship, their own opinion and the value that they place on behaviors and attributes are more relevant than objective observations.

Again, investment models tend to give correlational data rather than causal; it may be that a commitment established at an earlier stage leads inevitably to the partner viewing comparisons more favorably and investing more into the relationship.

Rusbult’s investment model has important real-world applications in that it can help explain why partners suffering abuse continue to stay in abusive relationships – although satisfaction may be very low, investment size (for example, children) may be very high, and they may lack alternative potential partners.

Rusbult (1995) found that for women living in a shelter for abused women, lack of alternatives and high investment were the major factors underlying why women returned to abusive relationships.

Duck’s Phase Model

Duck’s (2007) phase model suggests that the breakdown of a relationship is not a single event but rather a system of stages or phases in which a couple progresses, incorporating the end of the relationship.

Intra-Psychic Phase

Literally ‘within one’s own mind.’ In this phase, one of the partners begins to have doubts about the relationship. They spend time thinking about the pros and cons of the relationship and possible alternatives, including being alone. They may either internalize these feelings or confide in a trusted friend.

Dyadic Phase

The partners discuss their feelings about the relationship; this usually leads to hostility and may take place over a number of days or weeks. Over this period, the discussions will often focus on the equity in the relationship and will either culminate in a renewed resolution to invest in the relationship or the realization that the relationship has broken down.

Social Phase

Other people are involved in the process; friends are encouraged to choose a side and may urge for reconciliation with their partner or may encourage the breakdown through the expression of opinion or hidden facts (“I heard they did this…”). Each partner may seek approval from their friends at the expense of their previous romantic partner. At this point, the relationship is unlikely to be repaired as each partner has invested in the breakdown to their friends, and any retreat from this may be met with disapproval.

Grave-Dressing Phase

When the relationship has completely ended, each partner will seek to create a favorable narrative of the events, justifying to themselves and others why the relationship breakdown was not their fault, thus retaining their social value and not lowering their chances of future relationships.

Their internal narrative will focus more on processing the events of the relationship, perhaps reframing memories in the context of new discoveries about the partner. For example, an initial youthfulness may now be seen as immaturity.

Duck’s model may be a relevant description of the breakdown of relationships, but it does not explain what leads to the initial stages of the model, which other models of relationships discussed earlier attempt to do.

Duck’s phase model has useful real-life applications. When relationship therapists can identify the phase of a breakdown that a couple are in, they can identify strategies that target the issues at that particular stage. Duck (1994) recommends that couples in the intra-psychic phase should be encouraged to think about the positive rather than the negative aspects of their partner.

Rollie and Duck (2006) added a fifth stage to the model, the resurrection phase, where people take the experiences and knowledge gained from the previous relationship and apply it to future relationships they have. When Rollie and Duck revisited the model, they also emphasized that progression from one stage to the next is not inevitable and effective interventions can prevent this.

Virtual Relationships in Social Media

The development of social media sites since Facebook launched in 2004 has meant that people can initiate, maintain and dissolve relationships online without ever physically meeting the other person.

Research indicates important differences in the way in which people conduct virtual relationships compared to face-to-face relationships in terms of:

Self-Disclosure

This tends to vary according to whether the individual feels they are presenting information privately (e.g., private messaging) or publicly (e.g., their Facebook account). Disclosures to a public audience where the author’s identity is known are usually heavily edited.

Disclosures to ‘private’ audiences, particularly when the author’s identity is anonymous, are often marked by quicker and more revealing disclosures.

Online anonymity means that people do not fear the negative social consequences of disclosure in that they will not be judged negatively/punished for what would normally be judged as socially inappropriate disclosures.

Rubin (’75) found a similar phenomenon when studying personal disclosure of information in normal relationships, with people being far more likely to disclose highly personal information to strangers as they knew (a) they would probably never see the person again and (b) the stranger could not report disclosures to the individual’s social group.

Absence of Gating

A gate is any feature/obstacle that could interfere with the development of a relationship.

Gating in relationships refers to a peripheral feature becoming a barrier to the connection between people. This gate could be a physical feature, such as somebody’s weight or disfigurement, or a feature of one’s personality, such as introversion or shyness.

It may be that two people’s personalities are very compatible, and attraction would occur if they spoke for any length of time, but a gate prevents this from happening.

In face-to-face relationships, various factors influence the likelihood of a relationship starting in the 1st place: e.g., geographic location, social class, ethnicity, attractiveness, etc. These ‘gates’ are not present in virtual relationships and, in fact, people may mislead others online to form a false impression of their true identity: e.g., fake/photoshopped photos, females posing as males, etc.

McKenna and Bargh (1999) propose the idea that CmC relationships remove these gates and mean that there is little distraction from the connection between people that might not otherwise have occurred. Some people use the anonymity available on the internet to compensate for these gates by portraying themselves differently than they would do in FtF relationships.

People who lack confidence may use the extra time available in messaging to consider their responses more carefully, and those who perceive themselves to be unattractive may choose an avatar or edited picture which does not show this trait.

Gender bias – Theory assumes that gates affect people in the same way, but age and level of physical attractiveness are probably more gating factors for females seeking male partners than males seeking female partners – Research has suffered from a beta bias and oversimplified how gates are used in virtual relationships and are therefore less valid.

Zhao (2008) found that Facebook users often present highly edited, fictional representations of their true identity, presenting a false version of their ‘ideal’ self which they consider more likely to be attractive to others. Yurchisin (’05) interviewed online daters and found that although people would ‘stretch’ the truth about their true selves, they did not present completely imaginary identities to others for fear of rejection and ridicule if and when they met someone for a physical date.

Baker (2010) found that online relationships allowed shy people to overcome the lack of confidence that normally prevented them from forming face-to-face relationships. A survey of 207 male and female students found that high shyness and use of Facebook scores correlated with a higher perception of friend quality.

Low shyness and high Facebook use were not correlated with friendship quality. This seems to indicate that shy people may find virtual relationships particularly rewarding, presumably as the negative emotions brought about by face-to-face relationships are lessened or removed.

McKenna (2000) surveyed 568 internet users and found that just under 10% had gone on to physically meet friends who they had met online, and just over 10% had talked on the phone. After a 2-year gap, 57% revealed that their virtual relationship had increased intimacy. In terms of romantic relationships, 70% lasted 2 years or more compared to only 50% of relationships formed face-to-face.

A current danger in society relates to individuals assuming false identities online to deceive others into disclosing private information/images and then, possibly, blackmailing the individual who disclosed. School-delivered and online awareness campaigns aim to highlight the dangers of disclosing too much and putting trust in online relationships that may turn out to be based on false identities and/or dangerous/exploitative.

Parasocial Relationships

Levels of Parasocial Relationships

Parasocial relationships are one-sided relationships where one partner is unaware that they are apart of it.

Parasocial relationships may be described as those which are one-sided, Horton and Wohl (1956) defined them as relationships where the ‘fan’ is extremely invested in the relationships but the celebrity is unaware of their existence.

Parasocial relationships may occur with any dynamic which elevates someone above the population in a community, making it difficult for genuine interaction; this could be anyone from fictitious characters to teachers.

PSRs are usually directed toward media figures (musicians, bloggers, TV presenters, etc.). The object of the PSR becomes a meaningful figure in the individual’s life, and the ‘relationship’ may occupy a lot of the individual’s time.

PSRs are often formed because the individual lacks the social skills or opportunities to form a real relationship. PSRs do not involve risks present in real relationships, such as criticism or rejection.

PSRs are likely to form because the individual views the object of the PSR as (i) attractive and (ii) similar to themselves.

The Attachment Theory Explanation

Bowlby’s theory of attachment suggests that those who do not have a secure attachment earlier in life will have emotional difficulties and attachment disorders when they grow up.

Parasocial relationships are often associated with teenagers and young adults who may have had less genuine relationships to build an internal working model which allows them to recognize parasocial relationships as abnormal.

For example, it may be that those with insecure resistant attachment types are drawn to parasocial relationships because they do not offer the threat of rejection or abandonment.

The Absorption-Addiction Model

McCutcheon (2002) proposed that parasocial relationships form due to deficiencies in people’s lives. They look to the relationship to escape from reality, perhaps due to traumatic events or to fill the gap left by a real-life attachment ending.

Absorption refers to behavior designed to make the person feel closer to the celebrity. This could be anything from researching facts about them, both their personal life and their career, to repeatedly experiencing their work, playing their music or buying tickets to see them live, or paying for their merchandise to strengthen the apparent relationship.

As with other Addictions, this refers to the escalation of behavior to sustain and strengthen the relationship. The person starts to believe that the ‘need’ for the celebrity and behaviors become more extreme and more delusional. Stalking is a severe example of this behavior.

The absorption-addiction model can be viewed as more of a description of parasocial relationships than an explanation; it states how a parasocial relationship may be identified and the form it may take, but not what it is caused by.

Methodologically, many studies into parasocial relationships, such as Maltby’s 2006 survey, rely on the self-report technique. This can often lack validity, whether this is due to accidental inaccuracies, due to a warped perception of the parasocial relationship by the participant, genuine memory lapses, or more deliberate actions.

For example, the social desirability bias makes the respondents under-report their abnormal behavior. There is often competition between fans of celebrities to see who is the ‘biggest’ fan, which may lead to an exaggeration of the behaviors and attitudes when reporting the relationship.

McCutcheon et al. (2006) used 299 participants to investigate the links between attachment types and attitudes toward celebrities. They found no direct relationship between the type of attachment and the likelihood that a parasocial relationship will be formed.

Portrays a negative view of human behavior – PSRs are portrayed as psychopathological behavior like calling them ‘borderline pathological’ – Theory may be socially sensitive as it implies that such behavior is a bad thing when it may actually provide support for those who struggle with real-life relationships, it may be more appropriate to adopt a positive, humanistic approach.

Altman, I., Taylor, D. A., & Actman, I. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships (2nd ed.) . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Anderson, C., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2003). Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5) , 1054–1068. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1054

Aron, A., Melinat, E., Aron, E. N., Vallone, R. D., & Bator, R. J. (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4) , 363–377. doi:10.1177/0146167297234003

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(01) , 1. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00023992

Clark, R. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2(1) , 39–55. doi:10.1300/j056v02n01_04

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1) , 65–84. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.65

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3) , 285–290. doi:10.1037/h0033731

Feingold, A. (1988). Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2) , 226–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.226

Flanagan, C., Berry, D., & Jarvis, M. (2016). AQA psychology for A level year 2 – student book . United Kingdom: Illuminate Publishing.

Gallagher, M., Nelson, R., J, Y., & Weiner, I. B. (2003). Handbook of psychology: V. 3: Biological psychology . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Huston, T. L., & Levinger, G. (1978). Interpersonal attraction and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 29(1) , 115–156. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000555

Kerckhoff, A. C., & Davis, K. E. (1962). Value consensus and need Complementarity in mate selection. American Sociological Review,27(3) , 295. doi:10.2307/2089791

Landy, D., & Aronson, E. (1969). The influence of the character of the criminal and his victim on the decisions of simulated jurors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(2) , 141–152. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(69)90043-2

Little, A. C., & Jones, B. C. (2003). Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 270(1526) , 1759–1763. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2445

Singh, D. (1993). Adaptive significance of female physical attractiveness: Role of waist-to-hip ratio. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2) , 293–307. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.293

Sprecher, S., & Hendrick, S. S. (2004). Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,23(6) , 857–877. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.6.857.54803

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(5) , 508–516. doi:10.1037/h0021188

Waynforth, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1995). Conditional mate choice strategies in humans: Evidence from ‘lonely hearts’ advertisements. behavior, 132(9) , 755–779. doi:10.1163/156853995×001 andura’s Bobo Doll studies are laboratory experiments and therefore criticizable on the grounds of lacking ecological validity.’

Related Articles

A-Level Psychology

A-level Psychology AQA Revision Notes

Aggression Psychology Revision Notes

Psychopathology Revision Notes

Addiction in Psychology: Revision Notes for A-level Psychology

Psychology Approaches Revision for A-level

Forensic Psychology Revision Notes

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.8: Descriptive Research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59848

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between descriptive, experimental, and correlational research

- Explain the strengths and weaknesses of case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions to extensive, in-depth interviews—to well-controlled experiments.

The three main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. It aims to determine if one variable directly impacts and causes another. Correlational and experimental research both typically use hypothesis testing, whereas descriptive research does not.

Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected.

Correlational research can find a relationship between two variables, but the only way a researcher can claim that the relationship between the variables is cause and effect is to perform an experiment. In experimental research, which will be discussed later in the text, there is a tremendous amount of control over variables of interest. While this is a powerful approach, experiments are often conducted in very artificial settings. This calls into question the validity of experimental findings with regard to how they would apply in real-world settings. In addition, many of the questions that psychologists would like to answer cannot be pursued through experimental research because of ethical concerns.

The three main types of descriptive studies are case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Case Studies

In 2011, the New York Times published a feature story on Krista and Tatiana Hogan, Canadian twin girls. These particular twins are unique because Krista and Tatiana are conjoined twins, connected at the head. There is evidence that the two girls are connected in a part of the brain called the thalamus, which is a major sensory relay center. Most incoming sensory information is sent through the thalamus before reaching higher regions of the cerebral cortex for processing.

Link to Learning

To learn more about Krista and Tatiana, watch this video about their lives as conjoined twins.

The implications of this potential connection mean that it might be possible for one twin to experience the sensations of the other twin. For instance, if Krista is watching a particularly funny television program, Tatiana might smile or laugh even if she is not watching the program. This particular possibility has piqued the interest of many neuroscientists who seek to understand how the brain uses sensory information.

These twins represent an enormous resource in the study of the brain, and since their condition is very rare, it is likely that as long as their family agrees, scientists will follow these girls very closely throughout their lives to gain as much information as possible (Dominus, 2011).

In observational research, scientists are conducting a clinical or case study when they focus on one person or just a few individuals. Indeed, some scientists spend their entire careers studying just 10–20 individuals. Why would they do this? Obviously, when they focus their attention on a very small number of people, they can gain a tremendous amount of insight into those cases. The richness of information that is collected in clinical or case studies is unmatched by any other single research method. This allows the researcher to have a very deep understanding of the individuals and the particular phenomenon being studied.

If clinical or case studies provide so much information, why are they not more frequent among researchers? As it turns out, the major benefit of this particular approach is also a weakness. As mentioned earlier, this approach is often used when studying individuals who are interesting to researchers because they have a rare characteristic. Therefore, the individuals who serve as the focus of case studies are not like most other people. If scientists ultimately want to explain all behavior, focusing attention on such a special group of people can make it difficult to generalize any observations to the larger population as a whole. Generalizing refers to the ability to apply the findings of a particular research project to larger segments of society. Again, case studies provide enormous amounts of information, but since the cases are so specific, the potential to apply what’s learned to the average person may be very limited.

Query \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Naturalistic Observation

If you want to understand how behavior occurs, one of the best ways to gain information is to simply observe the behavior in its natural context. However, people might change their behavior in unexpected ways if they know they are being observed. How do researchers obtain accurate information when people tend to hide their natural behavior? As an example, imagine that your professor asks everyone in your class to raise their hand if they always wash their hands after using the restroom. Chances are that almost everyone in the classroom will raise their hand, but do you think hand washing after every trip to the restroom is really that universal?

This is very similar to the phenomenon mentioned earlier in this module: many individuals do not feel comfortable answering a question honestly. But if we are committed to finding out the facts about hand washing, we have other options available to us.

Suppose we send a classmate into the restroom to actually watch whether everyone washes their hands after using the restroom. Will our observer blend into the restroom environment by wearing a white lab coat, sitting with a clipboard, and staring at the sinks? We want our researcher to be inconspicuous—perhaps standing at one of the sinks pretending to put in contact lenses while secretly recording the relevant information. This type of observational study is called naturalistic observation : observing behavior in its natural setting. To better understand peer exclusion, Suzanne Fanger collaborated with colleagues at the University of Texas to observe the behavior of preschool children on a playground. How did the observers remain inconspicuous over the duration of the study? They equipped a few of the children with wireless microphones (which the children quickly forgot about) and observed while taking notes from a distance. Also, the children in that particular preschool (a “laboratory preschool”) were accustomed to having observers on the playground (Fanger, Frankel, & Hazen, 2012).

It is critical that the observer be as unobtrusive and as inconspicuous as possible: when people know they are being watched, they are less likely to behave naturally. If you have any doubt about this, ask yourself how your driving behavior might differ in two situations: In the first situation, you are driving down a deserted highway during the middle of the day; in the second situation, you are being followed by a police car down the same deserted highway (Figure 1).

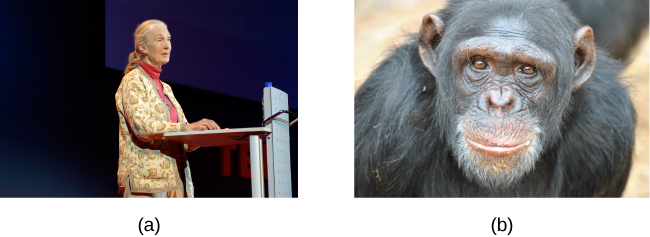

It should be pointed out that naturalistic observation is not limited to research involving humans. Indeed, some of the best-known examples of naturalistic observation involve researchers going into the field to observe various kinds of animals in their own environments. As with human studies, the researchers maintain their distance and avoid interfering with the animal subjects so as not to influence their natural behaviors. Scientists have used this technique to study social hierarchies and interactions among animals ranging from ground squirrels to gorillas. The information provided by these studies is invaluable in understanding how those animals organize socially and communicate with one another. The anthropologist Jane Goodall, for example, spent nearly five decades observing the behavior of chimpanzees in Africa (Figure 2). As an illustration of the types of concerns that a researcher might encounter in naturalistic observation, some scientists criticized Goodall for giving the chimps names instead of referring to them by numbers—using names was thought to undermine the emotional detachment required for the objectivity of the study (McKie, 2010).

The greatest benefit of naturalistic observation is the validity, or accuracy, of information collected unobtrusively in a natural setting. Having individuals behave as they normally would in a given situation means that we have a higher degree of ecological validity, or realism, than we might achieve with other research approaches. Therefore, our ability to generalize the findings of the research to real-world situations is enhanced. If done correctly, we need not worry about people or animals modifying their behavior simply because they are being observed. Sometimes, people may assume that reality programs give us a glimpse into authentic human behavior. However, the principle of inconspicuous observation is violated as reality stars are followed by camera crews and are interviewed on camera for personal confessionals. Given that environment, we must doubt how natural and realistic their behaviors are.

The major downside of naturalistic observation is that they are often difficult to set up and control. In our restroom study, what if you stood in the restroom all day prepared to record people’s hand washing behavior and no one came in? Or, what if you have been closely observing a troop of gorillas for weeks only to find that they migrated to a new place while you were sleeping in your tent? The benefit of realistic data comes at a cost. As a researcher you have no control of when (or if) you have behavior to observe. In addition, this type of observational research often requires significant investments of time, money, and a good dose of luck.

Sometimes studies involve structured observation. In these cases, people are observed while engaging in set, specific tasks. An excellent example of structured observation comes from Strange Situation by Mary Ainsworth (you will read more about this in the module on lifespan development). The Strange Situation is a procedure used to evaluate attachment styles that exist between an infant and caregiver. In this scenario, caregivers bring their infants into a room filled with toys. The Strange Situation involves a number of phases, including a stranger coming into the room, the caregiver leaving the room, and the caregiver’s return to the room. The infant’s behavior is closely monitored at each phase, but it is the behavior of the infant upon being reunited with the caregiver that is most telling in terms of characterizing the infant’s attachment style with the caregiver.

Another potential problem in observational research is observer bias . Generally, people who act as observers are closely involved in the research project and may unconsciously skew their observations to fit their research goals or expectations. To protect against this type of bias, researchers should have clear criteria established for the types of behaviors recorded and how those behaviors should be classified. In addition, researchers often compare observations of the same event by multiple observers, in order to test inter-rater reliability : a measure of reliability that assesses the consistency of observations by different observers.

Query \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Often, psychologists develop surveys as a means of gathering data. Surveys are lists of questions to be answered by research participants, and can be delivered as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, administered electronically, or conducted verbally (Figure 3). Generally, the survey itself can be completed in a short time, and the ease of administering a survey makes it easy to collect data from a large number of people.

Surveys allow researchers to gather data from larger samples than may be afforded by other research methods . A sample is a subset of individuals selected from a population , which is the overall group of individuals that the researchers are interested in. Researchers study the sample and seek to generalize their findings to the population.

There is both strength and weakness of the survey in comparison to case studies. By using surveys, we can collect information from a larger sample of people. A larger sample is better able to reflect the actual diversity of the population, thus allowing better generalizability. Therefore, if our sample is sufficiently large and diverse, we can assume that the data we collect from the survey can be generalized to the larger population with more certainty than the information collected through a case study. However, given the greater number of people involved, we are not able to collect the same depth of information on each person that would be collected in a case study.

Another potential weakness of surveys is something we touched on earlier in this module: people don’t always give accurate responses. They may lie, misremember, or answer questions in a way that they think makes them look good. For example, people may report drinking less alcohol than is actually the case.

Any number of research questions can be answered through the use of surveys. One real-world example is the research conducted by Jenkins, Ruppel, Kizer, Yehl, and Griffin (2012) about the backlash against the US Arab-American community following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Jenkins and colleagues wanted to determine to what extent these negative attitudes toward Arab-Americans still existed nearly a decade after the attacks occurred. In one study, 140 research participants filled out a survey with 10 questions, including questions asking directly about the participant’s overt prejudicial attitudes toward people of various ethnicities. The survey also asked indirect questions about how likely the participant would be to interact with a person of a given ethnicity in a variety of settings (such as, “How likely do you think it is that you would introduce yourself to a person of Arab-American descent?”). The results of the research suggested that participants were unwilling to report prejudicial attitudes toward any ethnic group. However, there were significant differences between their pattern of responses to questions about social interaction with Arab-Americans compared to other ethnic groups: they indicated less willingness for social interaction with Arab-Americans compared to the other ethnic groups. This suggested that the participants harbored subtle forms of prejudice against Arab-Americans, despite their assertions that this was not the case (Jenkins et al., 2012).

Query \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{11}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{12}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{13}\)

Think It Over

A friend of yours is working part-time in a local pet store. Your friend has become increasingly interested in how dogs normally communicate and interact with each other, and is thinking of visiting a local veterinary clinic to see how dogs interact in the waiting room. After reading this section, do you think this is the best way to better understand such interactions? Do you have any suggestions that might result in more valid data?

clinical or case study: observational research study focusing on one or a few people

correlational research: tests whether a relationship exists between two or more variables

descriptive research: research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables; they are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured

experimental research: tests a hypothesis to determine cause and effect relationships

generalize inferring that the results for a sample apply to the larger population

inter-rater reliability: measure of agreement among observers on how they record and classify a particular event

naturalistic observation: observation of behavior in its natural setting

observer bias: when observations may be skewed to align with observer expectations

population: overall group of individuals that the researchers are interested in

sample: subset of individuals selected from the larger population

survey: list of questions to be answered by research participants—given as paper-and-pencil questionnaires, administered electronically, or conducted verbally—allowing researchers to collect data from a large number of people

Licenses and Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Approaches to Research. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:iMyFZJzg@5/Approaches-to-Research . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Descriptive Research. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/researching-psychology-2/types-of-research-studies-27/descriptive-research-124-12659/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.1: Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 23459

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The actual test begins by considering two hypotheses . They are called the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . These hypotheses contain opposing viewpoints.

\(H_0\): The null hypothesis: It is a statement of no difference between the variables—they are not related. This can often be considered the status quo and as a result if you cannot accept the null it requires some action.

\(H_a\): The alternative hypothesis: It is a claim about the population that is contradictory to \(H_0\) and what we conclude when we reject \(H_0\). This is usually what the researcher is trying to prove.

Since the null and alternative hypotheses are contradictory, you must examine evidence to decide if you have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis or not. The evidence is in the form of sample data.

After you have determined which hypothesis the sample supports, you make a decision. There are two options for a decision. They are "reject \(H_0\)" if the sample information favors the alternative hypothesis or "do not reject \(H_0\)" or "decline to reject \(H_0\)" if the sample information is insufficient to reject the null hypothesis.

\(H_{0}\) always has a symbol with an equal in it. \(H_{a}\) never has a symbol with an equal in it. The choice of symbol depends on the wording of the hypothesis test. However, be aware that many researchers (including one of the co-authors in research work) use = in the null hypothesis, even with > or < as the symbol in the alternative hypothesis. This practice is acceptable because we only make the decision to reject or not reject the null hypothesis.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- \(H_{0}\): No more than 30% of the registered voters in Santa Clara County voted in the primary election. \(p \leq 30\)

- \(H_{a}\): More than 30% of the registered voters in Santa Clara County voted in the primary election. \(p > 30\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A medical trial is conducted to test whether or not a new medicine reduces cholesterol by 25%. State the null and alternative hypotheses.

- \(H_{0}\): The drug reduces cholesterol by 25%. \(p = 0.25\)

- \(H_{a}\): The drug does not reduce cholesterol by 25%. \(p \neq 0.25\)

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

We want to test whether the mean GPA of students in American colleges is different from 2.0 (out of 4.0). The null and alternative hypotheses are:

- \(H_{0}: \mu = 2.0\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu \neq 2.0\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

We want to test whether the mean height of eighth graders is 66 inches. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Fill in the correct symbol \((=, \neq, \geq, <, \leq, >)\) for the null and alternative hypotheses.

- \(H_{0}: \mu \_ 66\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu \_ 66\)

- \(H_{0}: \mu = 66\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu \neq 66\)

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

We want to test if college students take less than five years to graduate from college, on the average. The null and alternative hypotheses are:

- \(H_{0}: \mu \geq 5\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu < 5\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

We want to test if it takes fewer than 45 minutes to teach a lesson plan. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Fill in the correct symbol ( =, ≠, ≥, <, ≤, >) for the null and alternative hypotheses.

- \(H_{0}: \mu \_ 45\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu \_ 45\)

- \(H_{0}: \mu \geq 45\)

- \(H_{a}: \mu < 45\)

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)