Gender-affirming care has a long history in the US – and not just for transgender people

Associate Professor of History, Roanoke College

Disclosure statement

G. Samantha Rosenthal is co-founder of the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project

View all partners

In 1976, a woman from Roanoke, Virginia, named Rhoda received a prescription for two drugs: estrogen and progestin. Twelve months later, a local reporter noted Rhoda’s surprisingly soft skin and visible breasts. He wrote that the drugs had made her “so completely female.”

Indeed, that was the point. The University of Virginia Medical Center in nearby Charlottesville had a clinic specifically for women like Rhoda. In fact, doctors there had been prescribing hormones and performing surgeries – what today we would call gender-affirming care – for years.

The founder of that clinic, Dr. Milton Edgerton , had cut his teeth caring for transgender people at Johns Hopkins University in the 1960s. There, he was part of a team that established the nation’s first university-based Gender Identity Clinic in 1966.

When politicians today refer to gender-affirming care as new, “ untested ” or “ experimental ,” they ignore the long history of transgender medicine in the United States.

It’s been nearly 60 years since the first transgender medical clinic opened in the U.S. , and 47 years since Rhoda started her hormone therapy. Understanding the history of these treatments in the U.S. can be a helpful guide for citizens and legislators in a year when a record number of bills in statehouses target the rights of transgender people.

Treating gender in every population

As a trans woman and a scholar of transgender history , I have spent much of the past decade studying these issues . I also take several pills each morning to maintain the proper hormonal balance in my body: spironolactone to suppress testosterone and estradiol to increase estrogen.

When I began HRT, or hormone replacement therapy, like many Americans I wasn’t aware that this treatment had been around for generations. What I was even more surprised to learn was that HRT is often prescribed to cisgender women – women who were assigned female at birth and raised their whole lives as women. In fact, many providers in my region already had a long record of prescribing hormones to cis women , primarily women experiencing menopause.

I also learned that gender-affirming hormone therapies have been prescribed to cisgender youths for generations – despite what contemporary politicians may think. Disability scholar Eli Clare has written of the history and continued practice of prescribing hormones to boys who are too short and girls who are too tall for what is considered a “normal” range for their gender. Because of binary gender norms that celebrate height in men and smallness in women, doctors, parents and ethicists have approved the use of hormonal therapies to make children conform to these gender stereotypes since at least the 1940s .

Clare describes a severely disabled young woman whose parents – with the approval of doctors and ethicists from their local children’s hospital – administered puberty blockers so that she would never grow into an adult. They deemed her mentally incapable of becoming a “real” woman.

The history of these treatments demonstrates that hormone therapies and puberty blockers have been used on cisgender children in this country – for better or for worse – with the goal of regulating the passage from girlhood to womanhood and from boyhood to manhood. Gender stereotypes concerning the presence or absence of secondary sex characteristics – too tall, too short, too much body hair – have all led parents and doctors to perform gender-affirming care on cisgender children.

For over half a century, legal and medical authorities in the U.S. have also approved and administered surgeries and hormone therapies to force the bodies of intersex children to conform to binary gender stereotypes. I myself had genital surgery in infancy to bring my anatomy into alignment with expectations for what a “male” body should look like. In most cases, intersex surgeries are unnecessary for the health or well-being of a child.

Historians such as Jules Gill-Peterson have shown that early advances in transgender medicine in this country are deeply interwoven with the nonconsensual treatment of intersex children . Doctors at Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia practiced reconstructing the genitalia of intersex people before applying those same treatments on transgender patients.

Given these intertwined histories, I contend that the current political focus on prohibiting gender-affirming care for transgender people is evidence that opposition to these treatments is not about the safety of any specific medications or procedures, but rather their use specifically by transgender people.

How transgender people access care

Many transgender people in the U.S. have deeply complicated feelings about gender-affirming care. This complexity is a result of over half a century of transgender medicine and patient experiences in the U.S.

In Rhoda’s time, medical gatekeeping meant that she had to live “full time” as a woman and prove her suitability for gender-affirming care to a team of primarily white, cis male doctors before they would give her treatment. She had to mimic language about being “ born in the wrong body ” – language invented by cis doctors studying trans people, not by trans people themselves. She had to affirm she would be heterosexual and seek marriage and monogamy with a man. She could not be a lesbian or bisexual or promiscuous.

Many trans people still need to jump through similar hoops today to receive gender-affirming care. For example, a diagnosis of “ gender dysphoria ,” a designated mental disorder, is sometimes required before treatment. Many trans people argue that these preconditions for access to care should be removed because being trans is an identity and a lived experience, not a disorder.

Feminist activists in the 1970s also critiqued the role of medical authority in gender-affirming care. Writer Janice Raymond decried “ the transsexual empire ,” her term for the physicians, psychologists and other professionals who practice transgender medicine. Raymond argued that cis male doctors were making an army of trans women to satisfy the male gaze: promoting iterations of womanhood that reinforced sexist gender stereotypes, ultimately ushering in the displacement and eradication of the world’s “biological” women. The origins of today’s gender-critical, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist , movement are visible in Raymond’s words. But as trans scholar Sandy Stone wrote in her famous reply to Raymond , it’s not that trans women are unwilling dupes of cis male medical authority, but rather that we have to strategically perform our womanhood in certain ways to access the care and treatments we need.

The future of gender-affirming care

In many states, especially in the South, where I live, governors and legislatures are introducing bills to ban gender-affirming care – even for adults – in ignorance of history. The consequences of hurried legislation extend beyond trans people, because access to hormones and surgeries is a basic medical service many people may need to feel better in their body.

Prohibitions on hormone therapy and gender-related surgeries for minors could mean ending the same treatment options for cisgender children . The legal implications for intersex children may directly clash with proposed legislation in several states that aims to codify “male” and “female” as discrete biological sexes with certain anatomical features.

Prohibitions on hormone replacement therapy for adults could affect access to the same treatments for menopausal women or limit access to hormonal birth control. Prohibitions of gender-affirming surgeries could affect anyone’s ability to access a hysterectomy or a mastectomy . So-called cosmetic surgeries such as breast implants or reductions, and even facial feminization procedures such as lip fillers or Botox, could also come under question.

These are all different types of gender-affirming procedures. Are most Americans willing to live with this level of government intrusion into their bodily autonomy?

Almost every major medical organization in the U.S. has come out against new government restrictions on gender-affirming care because, as doctors and professionals, they know that these treatments are time-tested and safe . These treatments have histories reaching back over 50 years.

Trans and intersex people are important voices in this debate, because our bodies are the ones politicians opposing gender-affirming care most frequently treat as objects of ridicule and disgust . Legislators are developing policies about us despite the fact that most Americans say they do not even know a trans person .

But trans and intersex people know what it is like to have to fight to access the care and treatment we need. And we know the joy of finally feeling comfortable in our own skin and being able to affirm our gender on our own terms.

- Gender stereotypes

- Transgender

- Health care

- Gender dysphoria

- History of medicine

- Hormone therapy

- Johns Hopkins University

- Transgender rights

- Transgender health

- Trans rights

- LGBTQ history

- gatekeepers

- US health care

- Gender-affirming healthcare

- Trans healthcare

- Gender disparities

- Anti-trans legislation

- University of Virginia

- trans history

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Business Improvement Lead

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Gender-affirmation care

Development, advances in gender-affirming care.

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

gender-affirming surgery

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

gender-affirming surgery , medical procedure in which the physical sex characteristics of an individual are modified. Gender-affirming surgery typically is undertaken when an individual chooses to align their physical appearance with their gender identity , enabling the individual to achieve a greater sense of self and helping to reduce psychological distress that may be associated with gender dysphoria .

An individual’s physical sex may not match their gender identity when the person is intersex , having been born outside the binary of male and female and thus having ambiguous genitalia, or when the person identifies as transgender . Parents of an intersex child may elect to have surgical procedures carried out in order to have the child’s anatomy conform to binary notions of gender . A person’s ascribed legal sex may not match their gender identity as they mature. However, this situation raises serious concerns regarding the appropriateness of performing unnecessary medical procedures on the bodies of minors. Intersexuality is a normal biological variation and is not considered a medical condition. Therefore, medical interventions such as surgery and hormone therapy are typically unnecessary for intersex children.

Transgender individuals may seek gender-affirming surgery to align their physical body with their perception of their gender identity. Gender identity refers to an individual’s perception of their own gender, which may or may not correspond to their designated gender at birth. Gender identity encompasses the identification as male, female, both, neither, or somewhere else on the spectrum of gender. It is distinct from biological sex, which is determined by the sex chromosomes and anatomy of an individual. While the gender identity of most individuals corresponds to their ascribed biological sex, the gender identity of some individuals differs from their ascribed sex at birth, which can result in gender dysphoria and thereby lead the individual to seek gender-affirming surgery.

Individuals assigned male at birth may undergo one or more procedures to feminize their anatomy, including facial feminization surgery, penectomy (removal of the penis ), orchidectomy (removal of the testicles ), vaginoplasty (construction of a vagina ), and a tracheal shave (reduction of the Adam’s apple). Individuals who are assigned female at birth and who desire surgical intervention to masculinize their anatomy may seek breast reduction surgery, hysterectomy (removal of the uterus ), oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries ), and phalloplasty (construction of a penis).

Gender-affirming surgeries were performed during the 1920s and ’30s, primarily in Europe. These procedures were experimental and not extensively accepted by the medical community . At the time, it was widely believed that gender identity was immutable and that surgery could not alter it. However, Magnus Hirschfeld , a German sexologist and vocal advocate for sexual and gender diversity , assisted with the care of several transgender individuals.

Dora Richter was the first transgender individual to undergo complete male-to-female genital surgery under Hirschfeld’s supervision. Richter was one of several transgender individuals under Hirschfeld’s care at the Berlin Institute for Sexual Research. In 1922 Richter underwent an orchidectomy and, in 1931, a penectomy and vaginoplasty.

In 1930 and 1931 Lili Elbe also underwent several gender-affirming surgeries. These procedures included an orchidectomy, an ovarian transplant , and a penectomy. Elbe underwent a fourth surgery in June 1931, which consisted of an experimental uterine transplant and vaginoplasty. Elbe’s body rejected the transplanted uterus, and she died of postoperative complications in 1931.

During the 1950s and ’60s, significant advancements were made in the field of gender-affirming surgery, including the establishment of several major medical centres and the refinement of surgical techniques. Christian Hamburger, a Danish endocrinologist, performed a gender-affirming surgery in 1952 on Christine Jorgensen , a transgender individual, who underwent hormone replacement therapy and surgery to remove her testicles and create a vagina. Jorgensen became a public figure advocating for transgender rights and promoting awareness about gender-affirming surgery after their case received significant media attention.

Other medical centres in Europe and the United States began conducting gender-affirming surgeries around the same time, including the Johns Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic, founded in 1966. The founder of the clinic, psychiatrist John Money, believed that gender was a social construct and that gender-affirming surgery could be an effective treatment for individuals with gender dysphoria. Money’s theories had a significant impact on the field of gender-affirming surgery and helped to change the attitudes of the medical community regarding the procedure.

During the 1960s, new surgical techniques were developed, including advances in vaginoplasty and phalloplasty. In the 1950s Belgian surgeon Georges Burou devised a technique involving the use of skin grafts from the patient’s thigh to create a vaginal canal lining. For penises, he attached the phallus to a blood supply using tissue . This technique improved tissue perfusion and decreased the risk of complications such as tissue necrosis . These procedures marked a turning point in the development of gender-affirming care because they demonstrated the potential for successful genital reconstruction in transgender patients.

- Health Tech

- Health Insurance

- Medical Devices

- Gene Therapy

- Neuroscience

- H5N1 Bird Flu

Health Disparities

- Infectious Disease

- Mental Health

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Chronic Disease

- Alzheimer's

- Coercive Care

- The Obesity Revolution

- The War on Recovery

- Adam Feuerstein

- Matthew Herper

- Jennifer Adaeze Okwerekwu

- Ed Silverman

- CRISPR Tracker

- Breakthrough Device Tracker

- Generative AI Tracker

- Obesity Drug Tracker

- 2024 STAT Summit

- Wunderkinds Nomination

- STAT Madness

- STAT Brand Studio

Don't miss out

Subscribe to STAT+ today, for the best life sciences journalism in the industry

‘History is repeating itself’: The story of the nation’s first clinic for gender-affirming surgery

By Theresa Gaffney Oct. 3, 2022

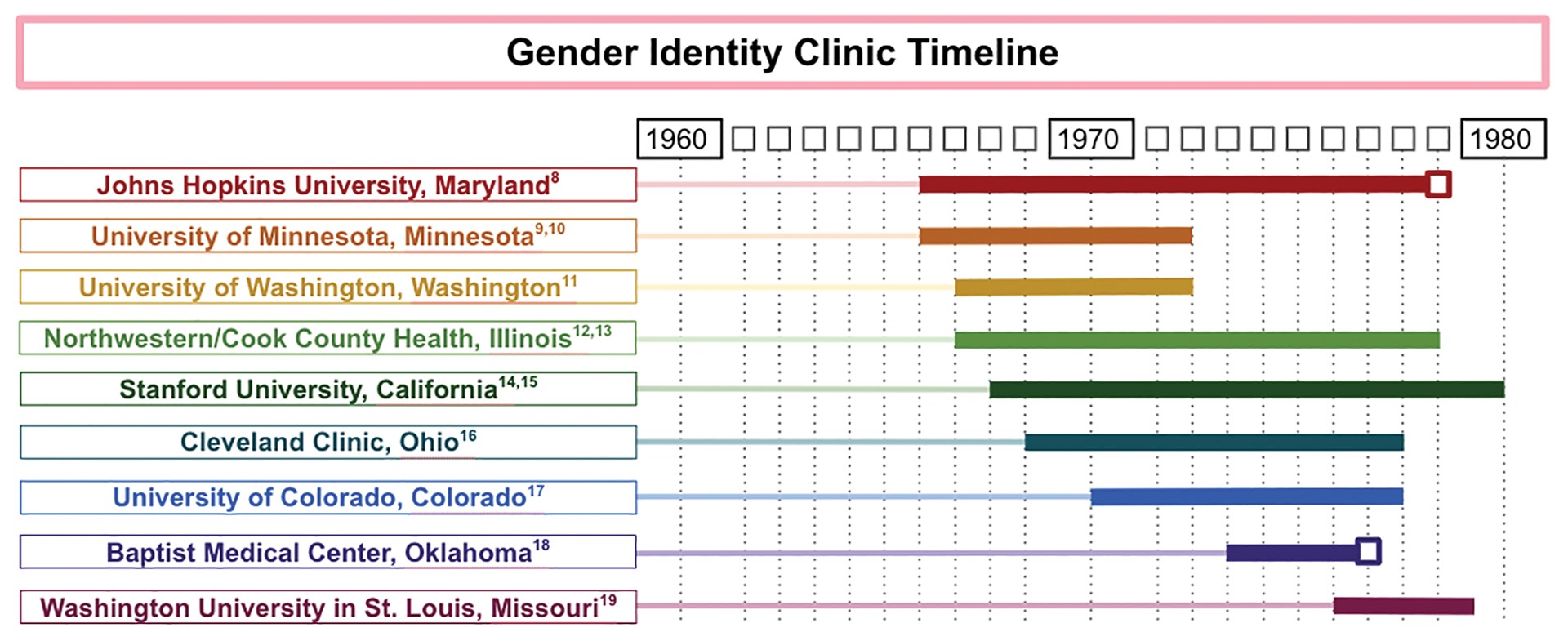

N early 60 years ago, Johns Hopkins Hospital opened a first-of-its-kind clinic to provide gender-affirming surgery. The Gender Identity Clinic blazed a new trail, with more than a dozen new clinics opening across the country in the decade that followed.

But in 1979, the clinic shut its doors. And while the institution claimed for years that the decision was made based on the evidence — which, they argued, showed such surgeries didn’t benefit patients — new research by a Johns Hopkins medical school student reveals a different story. The student, Walker Magrath, dug through years of archived correspondence and notes at both Johns Hopkins and Harvard University, and found that internal politics and pushback from hospital leadership ultimately caused the clinic to close.

advertisement

“It’s important for Johns Hopkins as an institution to reckon with its harmful history with LGBTQ patients,” said Magrath,who authored a new paper documenting the history of the center published Monday in Annals of Internal Medicine. For decades after the center closed, Johns Hopkins didn’t provide gender-affirming surgeries for trans patients — but it recently opened a center for transgender care.

In light of recent threats made to hospitals that provide gender-affirming care to trans patients and the closures of gender-affirming and reproductive health clinics across the country over the last year, Magrath felt that it was critical to make clear that this isn’t the first time gender-affirming clinics have faced backlash and closures.

Related: Harassment prompts children’s hospitals to strip websites, threatening access to gender-affirming care

“We need to be critical of mainstream medical institutions that wield a lot of power because their influence causes a [ripple] effect,” Magrath said. When the clinic at Johns Hopkins closed, others around the country began to shutter too. While there were 20 similar clinics in 1979, only two or three were still operating by the mid-1990s, according to Magrath.

“History is repeating itself,” said Alex Keuroghlian, of Massachusetts General Hospital and the Fenway Institute, who co-authored an editorial on Magrath’s paper with Asa Radix, of New York University and the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center. “We’re seeing the exact same tactics being used — defamation, sensationalist transphobia, intimidation of providers who want to offer this care,” Keuroghlian said.

Magrath found documentation that showed the clinic was met with bias and stigma from hospital leaders such as Paul McHugh, who became the hospital’s chief of psychiatry in 1975. McHugh arrived at Hopkins intending to stop gender-affirming surgery, according to Magrath. But Magrath also noted that McHugh, known for his pathologizing and homophobic statements on LGBTQ+ health, is just one of many leaders at the institution who fought against the clinic’s mission.

John Hoopes, the hospital’s chief of plastic surgery while the clinic operated, originally supported gender-affirming surgery and served as the GIC’s inaugural director, saying “there exists reasonably good evidence” that surgery could lead to positive results. But his opinions adapted as plastic surgery became a higher-profile specialty, leaving him worried that the slower progress around gender-affirming surgery would become a liability to his department. He later described transgender patients as “hysterical,” “freakish,” and “artificial.” Years before the closure, Hoopes ordered that the GIC be separated from the surgery department, depriving the clinic of valuable resources and leaving its physicians to operate under obstetrics department, which was mired in its own set of controversies that made it difficult to support the GIC’s work.

Related: Gender-affirming care should be embraced, not met with vitriol and bomb threats

When the clinic closed, the mainstream narrative was that research performed at Johns Hopkins had concluded that gender-affirmative surgery had no advantage for patients’ “social rehabilitation.” But the methods of the study were swiftly questioned by experts, who noted the conclusions may be unreasonable based on the statistics used. Magrath notes that the sample of patients included in that study were those treated in the earliest days of the clinic’s work, when surgical techniques were new and evolving. The clinic’s co-founder, psychologist John Money, admitted that some of those early cases were not successful, but was never given funding to do his own follow-up research.

In their accompanying editorial, Keuroghlian and Radix also point out that the metrics that researchers used to define rehabilitation focused more on fitting trans people into a limited, traditional model of success, rather than measuring their actual well-being.

“Studies are often used to fuel political agendas,” Magrath said. “Science often can be manipulated, and you can see that in our modern society.” It happened decades ago when the GIC was closed, he noted, and it’s happening now as pressure builds on facilities that provide gender-affirming care.

Historically, marginalized communities like trans and nonbinary people haven’t been included in providing care for their own communities, said Keuroghlian, who helps to train physicians across the country to provide gender-affirming care as part of their work at the Fenway Institute. This was part of the problem with the GIC, they said.

Related: ‘Critically important work’: Adm. Rachel Levine on efforts to combat gender-based discrimination in health care

“There was a real paternalism to how decisions were made by leadership, which is how a lot of medicine is characterized,” Keuroghlian said.

The health system still has a service in the Department of Plastic Surgery at Johns Hopkins named after Hoopes, and McHugh is still listed as a University Distinguished Service Professor on the institution’s website.

Liz Vandendriessche, a spokesperson for Johns Hopkins, said that while the institution supports its community members sharing their perspectives, the paper represents only Magrath’s personal opinion. She added that the hospital’s Center for Transgender Health provides care in line with the standards from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

To Keuroghlian and Magrath, there’s a need for more accountability from leading institutions like Johns Hopkins, which help to set the standard for health care.

“If our major, well-resourced academic teaching hospitals don’t set the example of providing care for the most marginalized in our communities, and don’t lead with health equity and social justice as organizing principles, then nobody else is going to do it,” Keuroghlian said.

This story has been updated to include a statement from a Johns Hopkins Medicine spokesperson.

About the Author Reprints

Theresa gaffney.

Morning Rounds Writer and Podcast Producer

Theresa Gaffney is the lead Morning Rounds writer and a podcast producer at STAT.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page .

Recommended

Recommended Stories

Telling new stories can help people see the value of vaccines

Walgreens executive says it is ‘doubling down’ on recruiting customers into clinical trials

STAT Plus: The inside story of how Lykos’ MDMA research went awry

STAT Plus: Google’s Verily to offer GLP-1 drugs through Lightpath, its retooled chronic care app

STAT Plus: At BIO, signs Congress’ tough stance on China is chilling biotech relationships

- Nation & World

Key dates for transgender rights in the US

Share story.

Some important events in the history of transgender rights in the United States:

1952: Christine Jorgensen completes sex-reassignment surgery in Denmark; she was the first American known for undergoing such a transition.

1969: Transgender people are in the forefront of the Stonewall Inn riots in New York City, which helped spark the U.S. gay-rights movement.

1977: The New York Supreme Court rules in favor of transgender physician/athlete Renee Richards in her bid to play pro tennis as a woman.

Most Read Nation & World Stories

- Oprah Winfrey hospitalized, Gayle King (over)shares

- Concerns about Princess Kate ramping up again

- Jimmy Carter not awake every day, 15 months into hospice

- Large whale group spotted off New England includes orca eating a tuna, dozens of endangered species VIEW

- Nevada man accused of interfering with crew on flight from Seattle to Anchorage is arrested

1993: Transgender man Brandon Teena is raped and murdered in Nebraska; his story is later made into the film “Boys Don’t Cry.” Minnesota becomes the first state to ban anti-transgender discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.

1999: Observance of the first international Day or Remembrance, an annual event honoring victims of anti-transgender violence.

2005: A pioneering California law bars health insurance companies from discriminating against transgender people.

2008: Isis King becomes first transgender model featured in the reality TV show “America’s Next Top Model.”

2009: President Obama signs a federal hate-crimes law that covers crimes motivated by anti-transgender bias.

2010: In response to a lawsuit, players of the Ladies Professional Golf Association vote to allow transgender players to compete on tour.

2012: Miss Universe opens its competition to transgender contestants. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission rules that discrimination based on transgender status is sex discrimination in violation of the Civil Rights Act.

2013: The American Psychiatric Association updates its diagnostic manual to stipulate that being transgender is no longer considered a mental disorder.

2014: Actress Laverne Cox becomes first transgender person featured on the cover of Time magazine. Maine’s highest court rules that a transgender fifth-grader should have been allowed to use the girls’ bathroom at her school.

2015: Caitlyn Jenner completes her gender transition, appears on the cover of Vanity Fair. Voters in Houston defeat an ordinance that would have extended nondiscrimination protections to transgender people.

2016: The U.S. military lifts its ban on transgender service members. The U.S. Supreme Court agrees to hear a Virginia case involving Gavin Grimm, a transgender boy seeking the right to use the boys’ restroom at his high school. The Obama administration advises public schools that transgender students should be allowed to use restrooms and locker rooms of their choice.

2017: The Trump administration revokes the Obama-era directive, saying policies for transgender students’ bathroom access should be set at the state and local level.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission Site

- Book Reviews

- Why Submit?

- About American Journal of Legal History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Lawfulness of Gender Reassignment Surgery

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Penney Lewis, The Lawfulness of Gender Reassignment Surgery, American Journal of Legal History , Volume 58, Issue 1, March 2018, Pages 56–85, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajlh/njx032

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In the common law world, both the medical and legal professions initially considered gender reassignment surgery to be unlawful when first practised and discussed in the first half of the twentieth century. While most medical procedures are covered by the medical exception to the law governing serious offences against the person, many doctors and the lawyers they consulted doubted that this exception applied to gender reassignment surgery. In this article I trace the differing and changing interpretations of the medical exception as applied to gender reassignment surgery, and the shift towards legal acceptance in the two common law jurisdictions that led the way in both performing gender reassignment surgery and debating its legality, the United States and the United Kingdom. Although this shift occurred without formal legal intervention either through legislation or judicial decision (for example on a test case), inferences of legality drawn from related civil-law decisions bolstered the legal acceptance of gender reassignment surgery.

By increasing the suffering of patients and potential patients, the criminal law played both an important and primarily malign role prior to the eventual public, professional and legal acceptance of GRS. A real threat of criminal prosecution inhibited doctors from proceeding, distorted diagnoses and affected the kinds of procedures performed. After-care was expanded and manipulated to avoid the risk of prosecution or the appearance of unlawful surgery. By contrast, civil and administrative law played a more positive, albeit indirect, role in interpreting the medical exception and its application to gender reassignment surgery.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2017 | 19 |

| January 2018 | 18 |

| February 2018 | 19 |

| March 2018 | 20 |

| April 2018 | 17 |

| May 2018 | 13 |

| June 2018 | 6 |

| July 2018 | 2 |

| August 2018 | 17 |

| September 2018 | 9 |

| October 2018 | 9 |

| November 2018 | 14 |

| December 2018 | 25 |

| January 2019 | 6 |

| February 2019 | 10 |

| March 2019 | 23 |

| April 2019 | 9 |

| May 2019 | 5 |

| June 2019 | 4 |

| July 2019 | 6 |

| August 2019 | 1 |

| September 2019 | 8 |

| October 2019 | 5 |

| November 2019 | 16 |

| December 2019 | 6 |

| January 2020 | 6 |

| February 2020 | 15 |

| March 2020 | 10 |

| April 2020 | 11 |

| May 2020 | 5 |

| June 2020 | 11 |

| July 2020 | 8 |

| August 2020 | 2 |

| September 2020 | 3 |

| October 2020 | 4 |

| November 2020 | 3 |

| December 2020 | 4 |

| January 2021 | 10 |

| February 2021 | 5 |

| March 2021 | 8 |

| April 2021 | 4 |

| May 2021 | 6 |

| June 2021 | 2 |

| July 2021 | 1 |

| August 2021 | 1 |

| September 2021 | 6 |

| October 2021 | 10 |

| November 2021 | 29 |

| December 2021 | 29 |

| January 2022 | 8 |

| February 2022 | 9 |

| March 2022 | 5 |

| April 2022 | 7 |

| May 2022 | 10 |

| June 2022 | 1 |

| July 2022 | 1 |

| August 2022 | 3 |

| September 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 5 |

| December 2022 | 7 |

| January 2023 | 3 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 11 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 7 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 17 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2161-797X

- Print ISSN 0002-9319

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Origins of Gender Affirmation Surgery: The History of the First Gender Identity Clinic in the United States at Johns Hopkins

Affiliation.

- 1 Office of Diversity and Inclusion, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD.

- PMID: 30557186

- DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001684

Background: Gender-affirming care, including surgery, has gained more attention recently as third-party payers increasingly recognize that care to address gender dysphoria is medically necessary. As more patients are covered by insurance, they become able to access care, and transgender cultural competence is becoming recognized as a consideration for health care providers. A growing number of academic medical institutions are beginning to offer focused gender-affirming medical and surgical care. In 2017, Johns Hopkins Medicine launched its new Center for Transgender Health. In this context, history and its lessons are important to consider. We sought to evaluate the operation of the first multidisciplinary Gender Identity Clinic in the United States at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, which helped pioneer what was then called "sex reassignment surgery."

Methods: We evaluated the records of the medical archives of the Johns Hopkins University.

Results: We report data on the beginning, aim, process, outcomes of the clinic, and the reasons behind its closure. This work reveals the function of, and the successes and challenges faced by, this pioneering clinic based on the official records of the hospital and mail correspondence among the founders of the clinic.

Conclusion: This is the first study that highlights the role of the Gender Identity Clinic in establishing gender affirmation surgery and reveals the reasons of its closure.

PubMed Disclaimer

- The Legacy of Gender-Affirming Surgical Care Is Complex. Edmiston EK. Edmiston EK. Ann Plast Surg. 2019 Oct;83(4):371. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002008. Ann Plast Surg. 2019. PMID: 31524723 No abstract available.

- Reply to: The Legacy of Gender-Affirming Surgical Care Is Complex. Neira PM, Siotos C, Coon D. Neira PM, et al. Ann Plast Surg. 2019 Oct;83(4):372. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002009. Ann Plast Surg. 2019. PMID: 31524724 No abstract available.

Similar articles

- A History of Gender-Affirming Surgery at the University of Michigan: Lessons for Today. Roblee C, Keyes O, Blasdel G, Haley C, Lane M, Marquette L, Hsu J, Kuzon WM Jr. Roblee C, et al. Semin Plast Surg. 2024 Jan 19;38(1):53-60. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-1778042. eCollection 2024 Feb. Semin Plast Surg. 2024. PMID: 38495068 Review.

- Age at First Experience of Gender Dysphoria Among Transgender Adults Seeking Gender-Affirming Surgery. Zaliznyak M, Bresee C, Garcia MM. Zaliznyak M, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 2;3(3):e201236. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1236. JAMA Netw Open. 2020. PMID: 32176303 Free PMC article.

- Gender-Affirming Surgery in Persons with Gender Dysphoria. Weissler JM, Chang BL, Carney MJ, Rengifo D, Messa CA 4th, Sarwer DB, Percec I. Weissler JM, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Mar;141(3):388e-396e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004123. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018. PMID: 29481407

- The Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria Study (1972-2015): Trends in Prevalence, Treatment, and Regrets. Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJM, Klaver M, de Vries ALC, Wensing-Kruger SA, de Jongh RT, Bouman MB, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis P, Gooren LJG, Kreukels BPC, den Heijer M. Wiepjes CM, et al. J Sex Med. 2018 Apr;15(4):582-590. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.016. Epub 2018 Feb 17. J Sex Med. 2018. PMID: 29463477

- A Historical Review of Gender-Affirming Medicine: Focus on Genital Reconstruction Surgery. Frey JD, Poudrier G, Thomson JE, Hazen A. Frey JD, et al. J Sex Med. 2017 Aug;14(8):991-1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.06.007. J Sex Med. 2017. PMID: 28760257 Review.

- Decoding the Misinformation-Legislation Pipeline: an analysis of Florida Medicaid and the current state of transgender healthcare. Lockmiller C. Lockmiller C. J Med Libr Assoc. 2023 Oct 2;111(4):750-761. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2023.1724. J Med Libr Assoc. 2023. PMID: 37928129 Free PMC article. Review.

- Journeying Through the Hurdles of Gender-Affirming Care Insurance: A Literature Analysis. Patel H, Camacho JM, Salehi N, Garakani R, Friedman L, Reid CM. Patel H, et al. Cureus. 2023 Mar 29;15(3):e36849. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36849. eCollection 2023 Mar. Cureus. 2023. PMID: 37123806 Free PMC article. Review.

- On, With, By-Advancing Transgender Health Research and Clinical Practice. Streed CG Jr, Perlson JE, Abrams MP, Lett E. Streed CG Jr, et al. Health Equity. 2023 Mar 3;7(1):161-165. doi: 10.1089/heq.2022.0146. eCollection 2023. Health Equity. 2023. PMID: 36895704 Free PMC article.

- Classification of Transgender Man's Breast for Optimizing Chest Masculinizing Gender-affirming Surgery. Wolf Y, Kwartin S. Wolf Y, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021 Jan 25;9(1):e3363. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003363. eCollection 2021 Jan. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021. PMID: 33564589 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Transgender Legal Battles: A Timeline

New laws regarding transgender youth are based on the assumption that the gender binary is natural.

In 1952, Christine Jorgensen stepped off of a plane from Denmark, where she had received groundbreaking medical care and had grown into herself as a “blonde beauty,” as the New York Daily News declared upon her return to the United States. By most accounts, she was accepted whole-heartedly into mainstream society and fawned upon as an ideal feminine figure, a somewhat unexpected response to the first well-known transgender woman in the country. In a 2011 article in Feminist Studies , historian Emily Skidmore argues that Christine Jorgensen’s success stemmed from her ability to uphold cultural norms of whiteness and femininity , both by playing the part expected of her, and rejecting any associations with “sex deviates” such as gay men, or transgender women without access to sex reassignment surgeries. Ironically, the first key congressional mention of gender identity came almost sixteen years later in 1968, during a hearing of the House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations in which Dr. Stanley F. Yolles, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, described the use of federal funds to study and treat these same “sex deviates” .

The contrast between the experience of Christine Jorgensen and other lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the 1950s and 60s—who were routinely discriminated against, harassed, and arrested—emphasizes the way that legislation is designed to enforce heteronormative gender roles and expectations. At the time, legislation was still focused on the criminalization of homosexuality through “gay behavior” in the bedroom and otherwise, with violent police harassment in private and public settings. Political campaigns at the time depicted gay people as dangerous and harmful , and enforcement of laws designed to control and oppress them disproportionately affected gender non-conforming people over those who “passed” as straight. Arrests of effeminate gay men, butch lesbians, low-income transgender women, “street queens,” and other gender non-conforming people were commonplace under laws that criminalized dressing or behaving in a way that the police officers deemed inappropriate for someone of a certain sex.

Both public opinion at the time and anti-LGBT legislation hinged upon the the belief that people could verify another’s gender identity through real or hypothetical cues, or “determine gender,” as researchers Laurel Westbrook and Kristen Schilt term it in their 2014 Gender and Society article. During this process, individuals use visual cues such as facial hair and clothing as proxies for biological validation of one’s sex , and when such cues conflict or become ambiguous, it may “create an interactional breakdown, generating anxiety, concern, and even anger.” This provides an incentive for cisgender people, whose own internal concept of their gender identity (as a man or woman) aligns with the sex they were assigned by a doctor at birth (male or female), to maintain and enforce a system in which “heterosexuality is positioned as the only natural and desirable sexual form.” On the other side of the same coin that allowed Christine Jorgensen to be accepted, there are implied and explicit forms of violence against people who do not fit neatly into heteronormative gender and sexuality boxes, with a harsher consequences for non-white or lower income communities.

In June 1969, patrons at a dodgy New York City gay bar called the Stonewall Inn began to fight back, creating a scene during a routine police raid of the premises. An event that purportedly started with a butch resisting arrest soon drew a crowd and turned into a six-day rebellion that would become a catalyst for gay rights movements around the country. Notably, the Stonewall Uprising was only one of a series of backlashes against inhumane police treatment of gay bar clientele at the time, including raids of Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco and the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles, but the context around the Stonewall Uprising in particular situated it as notable and memorable , allowing it to live on in historical accounts as the spark for gay liberation . On the first anniversary of Stonewall, the first gay liberation marches were held in New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, to commemorate the event. Those annual celebrations were the foundation for today’s pride parades and festivals, held across the country in the summer months.

Despite these instances of protest and growing resistance, legislative progress lagged for nearly three more decades. While arrests for “cross-dressing” tapered off, police found new ways to use “sodomy laws,” which outlawed certain types of sexual conduct, to harass and arrest gay people. Although many of these laws applied to straight–and even married–couples, they were focusing on LGBT circles, as a way to continue policing proper gender roles and identities. In 1982, 27-year-old bartender Michael Hardwick was arrested in Georgia for consensual sex in his own bedroom, after a police officer entered his house on a false warrant. The district attorney chose not to prosecute the case, but Hardwick and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) took the Bowers v. Hardwick case to the federal courts, until ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that the sodomy law in question was constitutional and allowed to stand, along with existing sodomy laws in 24 other states. These laws slowly toppled over time, but 14 states still criminalized sodomy when Bowers v. Hardwick was overturned by Lawrence v. Texas in 2003 , after police entered John Lawrence’s apartment on a false report of a weapon on the premises and found him engaged in so-called “homosexual conduct” with Tyron Garner.

Other legislation in the 1990s and early 2000s restricted financial means and support of the LGBT community, allowing discrimination against “transvestites” in housing and disability coverage, and criticizing use of funds toward LGBT art and film . In 1996, Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), invalidating any marriage between individuals of the same sex and enacting officially for the purposes of federal law, definitions of both “marriage” and “spouse” to avoid any interpretive gray area. Simultaneously, and in contrast to restrictive laws being created, the plight and suffering of LGBT people began to enter the public and legislative arena. In 1998, Representative Tom Lantos of California, Holocaust survivor and human rights champion, stood before Congress and urged them to fight for the fair treatment of LGBT people globally . He argued, eloquently, in his opening statement,

Whatever our views on our own domestic laws, Mr. Speaker, the Caucus and all Members of Congress should be standing together in decrying the persecution of individuals and the denial of human rights for any reason, including sexual orientation. … Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered people in communities all around the world have been brutally punished both physically and mentally for exercising their fundamental human rights to freedom of speech, freedom of association, and freedom of belief. Mr. Speaker, these violations fall squarely within the scope of international human rights laws.

Just two months after Tom Lantos called attention to the suffering of LGBT people in other areas of the world, the disfigured, nearly lifeless body of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, was discovered by a kid in Laramie, Wyoming. Matthew Shepard passed away in the hospital six days later, without waking from an injury-induced coma, and his death triggered a large-scale change in the public opinion of gay people and hate crime legislation. Awareness of the unfair treatment of LGBT individuals continued to grow in the 2000s, and in 2009, forty years after the original Stonewall Uprising, President Barack Obama designated June as LGBT Pride Month . That same year, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act amended the wording of the Federal Hate Crimes Law to include crimes based on real or perceived sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, or disability.

As the legislative landscape moved toward prohibiting explicit discrimination against LGBT people in the bedroom, the workforce, the military, and the nation’s schools, the social and legal system maintaining the heterosexual status quo of sex, gender, and sexuality began to lose control. The Obama Administration (2009-2017) was marked by the push and pull of progressive laws allowing more freedoms for LGBT Americans alongside restrictive laws with a new focus on controlling the lives of gender non-conforming youth. In stark juxtaposition, laws benefiting transgender adults passed as waves of attacks on transgender kids were introduced. The passing of the School Success and Opportunity Act in California, allowing students to participate in programs and use facilities consistent with their gender identity , regardless of sex assigned at birth, was quickly followed by the first proposed “bathroom bill” in Arizona, criminalizing use of facilities that did not align with one’s sex assigned at birth . Although this bill in Arizona ultimately failed, it set the precedent for a series of similar bills in other states.

In 2018, the first bills were introduced in New Hampshire explicitly prohibiting insurance coverage and performance of gender-affirming healthcare –such as hormone replacement treatment (HRT), puberty blockers, and “sex reassignment surgeries”–for transgender youth. Simultaneously, the world-wide discussion around sex enforcement in women’s sports , which had previously focused on testing endogenous testosterone levels in cisgender women, refocused onto banning transgender women and girls from participation. In 2019, Georgia introduced the first bill designed to limit the participation of athletes , specifically youth, in sports based on biological sex. In the following years, attempted legal restrictions on gender-affirming healthcare and participation in sports would soar, reaching highs of 34 and 67 introduced bills, respectively, in 2021. So far in 2022, bills have been introduced in Florida and passed the House in Idaho that would criminally prosecute any medical providers who provide gender-affirming care. Texas has gone so far as to introduce a bill that classifies the acceptance and affirmation of transgender children as child abuse and criminalizes parents who support a child’s.

With the focus on controlling the ability of transgender youth to express or affirm their identities through healthcare, participation in activities, or acceptance from adults in their lives, the pertinent question becomes: why do these issues warrant such strict restrictions on the affirmation and validation of transgender children and youth? Is it truly harmful or dangerous to do so, either for the transgender youth or their cisgender peers?

Proponents of laws restricting gender-affirming care access generally cite concerns that children are too young to understand their own gender and the implications of taking hormones or undergoing surgery, or that they will come to accept their gender identity as aligning with their sex assigned at birth and will regret transitioning. For example, in a 2017 article in The New Atlantis , a journal funded by a conservative advocacy group and not peer reviewed, lead author Paul Hruz and colleagues argue that the disruption of puberty, even when temporary, may be harmful , because “gender identity is shaped during puberty and adolescence as young people’s bodies become more sexually differentiated and mature”. The authors find this especially relevant in the context of scientific unknowns and conflicting findings on the outcomes of gender non-conforming children; although most adolescents that experience gender dysphoria continue to report these feelings through adulthood, the same finding does not hold up for young children under 12 who express discomfort with their assigned sex or gender role.

On the contrary, S Giordano argues that failing to delay puberty for transgender children has the potential to harm children equally , or more. Blocking puberty allows children to alleviate the distress of gender dysphoria while allowing them the time to consider whether they want to continue with a medical transition. In his 2008 article in the Journal for Medical Ethics , he describes, “if the child does not wish to transition, puberty suppressant drugs can be withheld and development restarts as normal. If the child decides to change sex, transition is much smoother if puberty has been arrested.” Giordano further concludes,

If allowing puberty to progress appears likely to harm the child, puberty should be suspended. There is nothing unethical with interfering with spontaneous development, when spontaneous development causes great harm to the child. Indeed, it is unethical to let children suffer, when their suffering can be alleviated.

Although they ultimately disagree on the path forward, both authors acknowledge that transgender populations are particularly vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation–making improved care an important public health issue. The most recent, large-scale survey of transgender adults in the United States found that 81.7 percent of respondents had seriously considered suicide in their lifetimes , and the surveyed population had a past-year prevalence of suicide attempts 18 times higher than the general US population. In addition, the study identified unique risk factors for transgender populations, concluding,

It’s clear that minority stress experiences, such as family rejection, discrimination experiences, and lack of access to gender affirming health care, create added risks for transgender people. Furthermore, the cumulative effect of experiencing multiple minority stressors is associated with dramatically higher prevalence of suicidality.

Notably, this 2019 research report by the Williams Institute also emphasized factors that were associated with a lower risk of suicidal ideation and attempt for respondents, including supportive family, access to hormone therapy and/or surgical care, and the presence of gender identity nondiscrimination statutes. A more recent research report published by the same group indicated that gender-affirming medical care, including pubertal suppression treatment, is recommended and supported as evidence-based patient care for transgender youth by several large-scale pediatric and psychiatric organizations, as it improves overall mental and physical health. Similarly, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines for providing the highest standards of care, which are “based on the best available science and expert professional consensus,” ultimately stress that “ withholding puberty suppression and subsequent feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy is not a neutral option for adolescents. ” These reports arrive at an understanding that recognizes knowledge gaps in current scientific evidence and the potential risks of treatments, while accounting for the known risks of denying or delaying care to transgender youth and adults.

Research in the Human Diversity Lab led by Kristina Olson, currently at Princeton University, has shown that the development of transgender children and their understanding of their gender matches cisgender children with the same gender identity, rather than sex assigned at birth. In a 2015 paper published in Psychological Science , they conclude, “ transgender children show responses that look largely indistinguishable from those of cisgender children, who match transgender children’s gender expression on both more- and less-controllable measures. ” The group further found in a 2019 study, published in PNAS, that gender identity of transgender children is “self-socialized” based on observations in all facets of their lives , rather than socialized based on how they are treated at home. They note,

Transgender children’s gender development does not appear to show lingering impact of early sex-assignment or sex-specific socialization. That is, a 10-y-old transgender girl who was labeled a boy at birth and raised for 9 y as a boy, a 10-y-old transgender girl who was labeled a boy at birth and raised for 5 y as a boy, and a 10-y-old cisgender girl … who was labeled a girl at birth and was raised for 10 y as a girl did not significantly differ in their identification and preferences…. These findings therefore provide preliminary evidence that neither sex assignment at birth nor direct or indirect sex-specific socialization and expectations … necessarily define how a child later identifies or expresses their gender.

In light of these findings and the many unanswered questions about gender development and outcomes of care in youth, researchers have developed the “gender affirmative model” of care, which advocates for “ listen[ing] to the child and decipher[ing] with the help of parents or caregivers what the child is communicating about both gender identity and gender expressions .” In this model, children are supported through the process of exploring their gender expression as they mature, and ultimately, making informed decisions about their care at appropriate ages.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Overall, research relating to physical and mental health outcomes in transgender youth indicates that rejection by family and community predicts negative outcomes, and that positive support from family, friends, and community protects youth and predicts positive outcomes . Current legislation restricting access of transgender youth to activities and facilities consistent with their gender identity, prohibiting gender-affirming care, and criminalizing family support functionally confines them in all aspects of their lives. Together, these sets of legislation would prohibit both social and medical transition for transgender youth to live and express themselves in a way that is consistent with their gender identity. As Laurel Westbrook and Kristen Schilt described, attempts to police participation in sex-segregated spaces and deny support to transgender people are designed to “uphold the logic of gender segregation” and “reassert the naturalness of a male-female binary”, which averts and subdues any panic or uncertainty around determining where transgender and gender non-conforming people fit into this system.

Through this lens, new waves of laws allowing discrimination and controlling access to social support for transgender youth may be reinventions of the cross-dressing and sodomy laws that enforced heterosexual and cisgender norms of behavior. As society struggles to reinforce a rigid gender binary in the face of growing dissent, the battle lines are formed by the lives, bodies, and health of transgender youth–all while their voices often go unheard.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Biobanking the Victims of Nuclear War

The Olive Trees of Palestine

The Race to Be the Tallest Building in the World

Eleutheria: A Lost Utopia in the Caribbean

Recent posts.

- Sex (No!), Drugs (No!), and Rock and Roll (Yes!)

- Revolutionary Writing in Carlos Bulosan’s America

- Saturn’s Ocean Moon Enceladus Is Able to Support Life

- Pas de Deux With Cancel Culture

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Name Search

- Browse Legal Issues

- Browse Law Firms

State Laws on Gender-Affirming Care

By Vaishali Gaur, Esq. | Legally reviewed by Laura Temme, Esq. | Last reviewed June 14, 2023

Legally Reviewed

This article has been written and reviewed for legal accuracy, clarity, and style by FindLaw’s team of legal writers and attorneys and in accordance with our editorial standards .

Fact-Checked

The last updated date refers to the last time this article was reviewed by FindLaw or one of our contributing authors . We make every effort to keep our articles updated. For information regarding a specific legal issue affecting you, please contact an attorney in your area .

Gender-affirming medical care helps nonbinary or transgender people with their physical transition. But many states have restricted access to this type of medical care for minors. Some states have even criminalized providing minors with gender-affirming care.

Gender-affirming care is crucial for the well-being of many transgender and nonbinary people. However, access to gender-affirming care has become inconsistent across the United States. This is especially true for minors.

Almost half of the state legislatures in the country recently passed laws restricting or banning such care. Some states have even criminalized providing minors with gender-affirming care.

This article provides an overview of what gender-affirming care is and which states have restricted access.

What is Gender-Affirming Care?

Gender-affirming care refers to many types of treatment for gender transitions and gender dysphoria. It can focus on psychiatric care, physical medical care, or multidisciplinary treatment. Gender dysphoria is the feeling of distress or discomfort a person feels when their gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. It negatively impacts a person's mental health, often leading to depression and other issues.

Gender transitions can involve:

- Social transition (dressing according to gender identity, using a different name or pronouns)

- Medical transition (any combination of hormone therapy, surgical medical procedures, and nonsurgical medical procedures)

- Legal transition (legally changing name and gender marker )

Gender-affirming medical care helps nonbinary or transgender people with their physical transition. It can include hormone replacement therapy, gender-affirming surgery, or both. Gender-affirming surgery might involve:

- “Top" surgery (reconstructive surgery for the chest area)

- “Bottom" surgery (reconstructive surgery for the genital area, also known as gender confirmation, sex reassignment, or gender reassignment surgery)

- Facial feminization or masculinization procedures

- Voice surgery procedures

For many, gender-affirming care is a life-saving course of treatment. A transgender or nonbinary person's gender identity is still valid even if they have not pursued this type of care.

Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Minors

For children and adolescents, gender-affirming care often focuses on social transition. However, in some cases, transgender children will be prescribed puberty blockers . These medications temporarily halt the changes young people experience during puberty.

For someone identified as male at birth, puberty blockers can prevent the deepening of their voice and the growth of facial and body hair. For those identified at birth as female, puberty blockers stop menstruation and breast development. But if young people stop taking the medication, puberty resumes, and they will go through the expected physical changes.

Puberty blockers are also used to treat precocious puberty . This condition, unrelated to gender dysphoria, causes a child to go through puberty too early.

Many major medical organizations support gender-affirming health care for minors, including:

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- American Medical Association

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- American Psychological Association

- American Psychiatric Association

- Endocrine Society

These organizations view gender-affirming care as appropriate “evidence-based" transgender health care. This describes an approach where doctors and medical providers rely on the best available scientific evidence from clinical research to decide what is best for their patients. Still, lawmakers in some states have passed laws in recent legislative sessions that limit or even ban gender-affirming care.

Types of Laws on Gender-Affirming Care

The map above depicts the level of restrictions on gender-affirming care in different states (as of the date of this article). States that appear in light blue currently restrict access to gender-affirming care for minors. Those states are:

Mississippi

North carolina, north dakota.

- South Carolina*

South Dakota

West virginia.

States in this list with an asterisk (*) have legislation pending that restricts access for minors.

States Without Restrictions on Gender-Affirming Care

States that appear in medium blue currently have no restrictions on gender-affirming care. Those states are:

District of Columbia

New hampshire, pennsylvania, rhode island.

The only state that appears in white is Missouri, which has restricted gender-affirming care for both minors and adults. A dark blue dot near the border of Missouri and Kansas indicates that Kansas City, Missouri, has declared itself a sanctuary city.

Some of these states are currently considering competing legislation. In New Hampshire, Republican-sponsored bills aim to ban gender-affirming care for minors and would even define it as child abuse. Meanwhile, Democrats in the state proposed a bill to make New Hampshire a sanctuary state (discussed below).

Sanctuary States

State legislation banning gender-affirming care for minors has caused worry for many. Families of nonbinary and transgender youth might feel displaced or unsafe. In response, a handful of states have designated themselves as safe harbors or "sanctuary states." These states appear in dark blue on the map above.

Sanctuary states protect access to gender-affirming care for residents of that state. Plus, they are a safe haven for trans and nonbinary people from other states. These states will not enforce penalties from another state relating to gender-affirming care:

Connecticut

Massachusetts.

Below, we provide a detailed look at the laws currently in effect in each state.

Access to Gender-Affirming Care by State

Note: The laws surrounding gender-affirming care are changing quickly. While we aim to provide the most up-to-date information on this topic, it's best to check your state legislature's website for the most recent information if you or a loved one wish to pursue gender-affirming care.

Alabama banned gender-affirming care for minors in April 2022. The law criminalizes giving puberty blockers and other gender-affirming treatments to anyone under 19. A charge under this law could result in up to 10 years in prison.

Alaska has no ban on gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

In 2022, Arizona prohibited minors from obtaining gender-affirming care ( SB 1138 ). The bill allows exceptions in the case of physical injury or illness that places the individual in imminent danger of death or for intersex individuals. The state does not have any laws prohibiting adults from receiving gender-affirming care.

Arkansas was the first state to pass a law outlawing gender-affirming care for minors ( HB 1570 ). In 2021, the state legislature passed a bill banning gender surgery and hormone therapy for minors. The law was challenged in federal court and barred by a preliminary injunction. The state's appellate court upheld the injunction . This means the ban will not take effect until the district court makes its final determination. The state does not have any laws prohibiting adults from receiving gender-affirming care.

California is a sanctuary state. In 2023, a state law providing protections for trans youth and their families went into effect (SB 107). Some states are removing minors from their parent's care if they allow the child to receive gender-affirming care. But California will not enforce another state's order to remove a minor from their parent or guardian's care.

Colorado is a sanctuary state. In 2023, a bill defining gender-affirming care as a “legally protected health-care activity" was signed into law . Under this law, state courts will not issue subpoenas connected to another state's lawsuit against a doctor who provides gender-affirming care.

Connecticut is a sanctuary state. In 2022, the state passed a law protecting individuals against out-of-state judgments based on gender-affirming care they receive in Connecticut. The state has no ban on gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

Delaware has no ban on gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

The District of Columbia has no ban on gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

Florida bans minors from receiving gender-affirming care . The Florida Board of Medicine also prohibited health care providers from performing gender-affirming care for minors unless the minor has already undergone surgery.

Georgia bans minors from receiving gender-affirming care. In 2023, a bill prohibiting medical professionals from providing gender-affirming care to minors was signed into law . The law provides exceptions for:

- Intersex individuals

- Situations where the treatment is deemed medically necessary

- Cases where minors are being treated with irreversible hormone replacement therapy

Hawai'i does not ban gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

Idaho passed a law in 2023 that makes it a felony for a medical professional to provide gender-affirming care to minors. The law includes exceptions for intersex individuals and the treatment of any infection or injury caused by prior gender-affirming care. The state does not have any laws prohibiting adults from receiving gender-affirming care.

Illinois is a sanctuary state and passed a law in 2023 that increased protections for medical professionals providing and individuals receiving gender-affirming care. The law defines gender-affirming care as “lawful health care." It prohibits the enforcement of subpoenas related to the enforcement of another state's gender-affirming care laws.

An Indiana law restricted minors from accessing gender-affirming care in 2023 and mandated any minors currently taking gender-affirming medications to cease doing so by the end of 2023.

The law provides exceptions for intersex minors, procedures necessary to treat an injury or illness caused by prior gender-affirming care, and the imminent threat of death.

The state does not have any laws prohibiting adults from receiving gender-affirming care.

In 2023, Iowa passed a law prohibiting medical professionals from providing gender-affirming care to minors.

Kansas does not ban gender-affirming care for minors or adults. However, the governor recently vetoed a proposed state law that would have required the state's medical board to revoke the medical licenses of physicians providing gender-affirming care to minors.

Kentucky recently passed a law prohibiting minors from accessing gender-affirming care and requiring medical professionals to end any gender-affirming care for minors. Although the bill was originally vetoed by the governor, the veto was ultimately overridden by the legislature. The state does not ban adults from seeking gender-affirming care.

A bill was recently introduced in Louisiana aimed at banning gender-affirming care for minors. In addition to banning hormone replacement therapy and gender-affirming surgery, the bill would also ban minors from undergoing cosmetic procedures, such as hair transplants and liposuction, if the goal of the procedures is to “promote the development of feminizing or masculinizing features in the opposite sex." Lawmakers in Louisiana's House of Representatives passed the bill. However, it was rejected by a state Senate committee in May 2023 . The state does not ban adults from accessing gender-affirming care.

Maine does not ban gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

Maryland does not ban gender-affirming care for minors or adults.

Massachusetts is a sanctuary state. It passed a law in 2022 , expanding protections for individuals seeking gender-affirming care. Among other things, the law defined gender-affirming care as “legally protected health care" and protected individuals from out-of-state legal action for seeking gender-affirming care.

In October 2022, a bill was introduced in Michigan that could make it a first-degree felony of child abuse for a parent or guardian to allow minor children to access gender-affirming care. However, that measure was unsuccessful. In March 2023, the state's House of Representatives passed an amendment to the Eliot-Larsen Civil Rights Act . This bill expands the state's protections against discrimination to include gender identity and sexual orientation. Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed the bill into law on March 16, 2023.

Minnesota is a sanctuary state. Recently, the state governor signed a bill protecting gender-affirming care . Among other things, the law prohibits the use of subpoenas to gather information about individuals that are related to out-of-state laws banning gender-affirming care. It also provides custody protections to parents or guardians who assist their minor children in accessing gender-affirming care.

Mississippi recently banned health care professionals from providing gender-affirming care to minors .

In April 2023, Missouri's Attorney General issued an emergency regulation to ban gender-affirming care for minors and adults. The rule was temporarily blocked by a state judge after being challenged in court .

In 2023, state lawmakers passed a bill banning gender-affirming care for minors. It also restricts access to care for adults who rely on Medicare for their health care costs. Governor Mike Parson signed the bill into law, and it will take effect on August 28, 2023.

However, officials in Kansas City declared the state's largest city as a sanctuary for gender-affirming care . For more details on how this affects access to care, it's best to consult with a local civil rights or health care attorney .