- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- Is a Thesis Writing Format Easy? A Comprehensive Guide to Thesis Writing

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- How to Use AI in Essay Writing: Tips, Tools, and FAQs

- Copy Editing Vs Proofreading: What’s The Difference?

- How Much Does It Cost To Write A Thesis? Get Complete Process & Tips

- How Much Do Proofreading Services Cost in 2024? Per Word and Hourly Rates With Charts

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

How to structure an essay

(Last updated: 13 May 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

This guide is for anyone looking to vastly improve their essay writing skills through better knowledge what is meant by good 'essay structure'.

Essay writing is a key component to academic success at every level. It is, essentially, the way in which people within the academic community communicate with each other. Thus, there are fundamental ways in which academics structure their work and formal ways of communicating what they have to say. Writing essays is not simply a hoop for students to jump through. The vast majority of instructors and professors also write essays at a professional level, and they do not ask of their students anything less than the standard that is asked of them.

Where too many students go wrong in writing their essays is in either failing to plan ahead (not giving sufficient, care, thought, or time to the process) or in not understanding the expectations of essay writing. Of these expectations, appropriate and effective essay structure is critical. Students often lose valuable marks by failing to structure their essays clearly and concisely to make the best of their ideas.

So how do you structure academic writing? What is the best essay structure format?

First, consider what an essay is . What is it supposed to do? At its core an essay is simply an argument . Now, by argument we don’t mean a slanging match between two angry people. Rather, we are talking about a formal argument. An idea or a claim, which is supported by logic and/or evidence.

Imagine the following scenario: you feel the time has come to approach your boss about getting a raise at work. Imagine yourself walking into your supervisor’s office and requesting that raise. Almost automatically, your mind formulates a rhetorical structure. There are effective and ineffective ways of asking of making such a request. The effective strategy will have a logic and an order. You will firstly claim that you deserve a raise. And you will give evidence to support why you deserve that raise. For example: you are a hard worker, you are never late, you have the admiration and respect of your colleagues, you have been offered another position elsewhere and you want the pay matched. And so on. And you would probably wrap up your discussion with an overview of of why giving you more money is important.

And that is fundamentally an essay. Every good essay has three basic parts: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

This simple guide will show you how to perfect your essay structure by clearly introducing and concluding your argument, and laying out your paragraphs coherently in between. Your essay writing can be dramatically improved overnight simply by using the correct essay structure, as explained below.

Where the essay starts

When you are writing an essay , every sentence and every paragraph is important. But there is something extra important about introductions. Just like going out on a date for the first time, you want the introduction to be just right, almost perfect. You want to put your best self forward and create a great first impression.

You should already know this, but most professors and instructors will start grading your work in their head as soon as they begin reading it. They will be sorting your essay, maybe not in terms of a grade, but most definitely in terms of strong/weak, interesting/dull, or effective/ineffective. And most will have some notion of where your essay falls on that scale before they even finish the introduction. It will be the rarest of markers who withholds judgement until the end. The introduction is something you absolutely must start strong.

Always develop an introduction that clearly sets out the aims of what you are about to write and, if applicable, refers to the subject under investigation. State what the essay will try to achieve and briefly mention some of the main points you will consider. The idea is to give the marker an overview of your argument, to show that your thought process is logical and coherent and that you have carefully thought the question through. Don’t try to go into any of your key points in depth in your introduction – they will each be covered by a full paragraph later on. If the question is an ‘either or’ or a ‘how far do you agree’ question, it is useful to set out both sides of the argument briefly in the introduction in preparation for exploring the two sides later in the essay.

Think of your introduction as a thumbnail picture of the whole essay. Anyone, but especially the marker, should know the essay subject and how you intend to prove or disprove it, just from having read just the introduction.

Take the following example:

You have been given this assignment: The main purpose of Gothic fiction is to break normal moral and social codes. Discuss.

A strong introduction should read something like this:

It is certainly true that many works of Gothic fiction manifest the transgression of normal moral and social codes as their major theme. Their emphasis on female sexuality, their breaking of the boundaries between life and death and their shocking displays of immoral religious characters would all suggest that this is indeed the case. However, it is also important to consider other major aspects of the genre that might be considered equally important in purpose, such as its fascination with the supernatural, its portrayal of artificial humanity and its satirical social attacks. This essay will explore these conflicting purposes with reference to several different Gothic texts to discover what might be best described as the ‘main’ purpose of the genre.

Reread that paragraph. Does it tell you what the topic of the essay is? What the point is? What the essay plans to do? Now, without reading think about just the size of that paragraph. If a marker were to see an introduction that were any less than that they would automatically know, without even reading a word, that the topic was not going to be well introduced. That is not to suggest you simply fill up the paragraph, but that a certain amount of information in the introduction is expected.

It is worth pointing out that in a much longer essay an introduction does not need to be limited to a single paragraph. Generally, however, it will be.

The body of your essay

The second part of the essay is the body. This is the longest part of the essay. In general, a short essay will have at least three full paragraphs; a long essay considerably more.

Each paragraph is a point that you want to make that relates to the topic. So, going back to the ‘give me more money’ example from earlier, each reason you have for deserving a raise should be a separate paragraph, and that paragraph is an elaboration on that claim.

Paragraphs, like the essay overall, also have an expected structure. You should start a new paragraph for each major new idea within your essay, to clearly show the examiner the structure of your argument. Each paragraph should begin with a signpost sentence that sets out the main point you are going to explore in that section. It is sometimes helpful to refer back to the title of the essay in the signpost sentence, to remind the examiner of the relevance of your point. Essay writing becomes much easier for you too this way, as you remind yourself exactly what you are focusing on each step of the way.

Here's a signpost sentence example: One important way in which Gothic fiction transgresses normal moral and social codes is in its portrayal of the female heroine.

Further sentences in this paragraph would then go on to expand and back up your point in greater detail and with relevant examples. The paragraph should not contain any sentences that are not directly related to the issue set out in the signpost sentence. So you are writing an essay that clearly separates its ideas into structured sections. Going back to the wage-raise example: in the middle of talking about how punctual you are, would you start talking about how you are a good colleague, then about that client you impressed, and then talk about your punctuality again? Of course not. The same rules apply: each paragraph deals with one idea, one subject.

The end of your essay

The last section of your essay is the conclusion. In general, this will also be a single paragraph in shorter essays, but can go on to two or three for slightly longer discussions.

Every well-structured essay ends with a conclusion . Its purpose is to summarise the main points of your argument and, if appropriate, to draw a final decision or judgement about the issues you have been discussing. Sometimes, conclusions attempt to connect the essay to broader issues or areas of further study.

It is important not to introduce any new ideas in the conclusion – it is simply a reminder of what your essay has already covered. It may be useful again to refer back to the title in the conclusion to make it very clear to the examiner that you have thoroughly answered the question at hand. Make sure you remind them of your argument by very concisely touching on each key point.

Here an example of an essay conclusion:

Overall, whilst it is certainly true that the characters, plots and settings of Gothic fiction seem firmly intended to break normal moral and social codes, the great incidence within the genre of the depiction of the supernatural, and in particular its insistent reference to social injustice and hypocrisy might suggest that in fact its main purpose was the criticism and reform of society.

But where do I start???

Now you should have a solid grasp of a typical essay structure but might not know how to actually begin structuring your essay. Everyone works differently. Some people have no trouble thinking everything out in their head, or putting together a plan, and starting with the introduction and finishing with the conclusion.

One surefire way to make your life easier is to, in the first instance, write out an essay plan . Jotting down a plan where you create a structure, which details what your essay will cover, will save you time in the long run - so we highly recommend you do this!

When planning your essay structure, we suggest writing from the inside out and doing the body paragraphs first. Since each body paragraph is a main idea, then once you know what your main ideas are, these should come fairly easily. Then the introduction and conclusion after that.

If you're really struggling - or just curious - you can also look into the Essay Writing Service from ourselves here at Oxbridge Essays. We can put together a comprehensive essay plan for you, which maps out your essay and outlines the key points in advance, and in turn makes the writing process much easier.

One final thought to remember: good essays are not written, they are rewritten . Always go over your first draft and look for ways to improve it before handing it in.

Essay exams: how to answer ‘To what extent…’

How to write a master’s essay

- essay structure

- writing a good essay

- writing tips

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Format and Structure Your College Essay

←What Is a College Application Theme and How Do You Come Up With One?

How to Write a Personal Statement That Wows Colleges→

Does your Common App essay actually stand out?

Your essay can be the difference between an acceptance and rejection — it allows you to stand out from the rest of applicants with similar profiles. Get a free peer review or review other students’ essays right now to understand the strength of your essay.

Submit or Review an Essay — for free!

College essays are an entirely new type of writing for high school seniors. For that reason, many students are confused about proper formatting and essay structure. Should you double-space or single-space? Do you need a title? What kind of narrative style is best-suited for your topic?

In this post, we’ll be going over proper college essay format, traditional and unconventional essay structures (plus sample essays!), and which structure might work best for you.

General College Essay Formatting Guidelines

How you format your essay will depend on whether you’re submitting in a text box, or attaching a document. We’ll go over the different best practices for both, but regardless of how you’re submitting, here are some general formatting tips:

- There’s no need for a title; it takes up unnecessary space and eats into your word count

- Stay within the word count as much as possible (+/- 10% of the upper limit). For further discussion on college essay length, see our post How Long Should Your College Essay Be?

- Indent or double space to separate paragraphs clearly

If you’re submitting in a text box:

- Avoid italics and bold, since formatting often doesn’t transfer over in text boxes

- Be careful with essays meant to be a certain shape (like a balloon); text boxes will likely not respect that formatting. Beyond that, this technique can also seem gimmicky, so proceed with caution

- Make sure that paragraphs are clearly separated, as text boxes can also undo indents and double spacing

If you’re attaching a document:

- Use a standard font and size like Times New Roman, 12 point

- Make your lines 1.5-spaced or double-spaced

- Use 1-inch margins

- Save as a PDF since it can’t be edited. This also prevents any formatting issues that come with Microsoft Word, since older versions are sometimes incompatible with the newer formatting

- Number each page with your last name in the header or footer (like “Smith 1”)

- Pay extra attention to any word limits, as you won’t be cut off automatically, unlike with most text boxes

Conventional College Essay Structures

Now that we’ve gone over the logistical aspects of your essay, let’s talk about how you should structure your writing. There are three traditional college essay structures. They are:

- In-the-moment narrative

- Narrative told over an extended period of time

- Series of anecdotes, or montage

Let’s go over what each one is exactly, and take a look at some real essays using these structures.

1. In-the-moment narrative

This is where you tell the story one moment at a time, sharing the events as they occur. In the moment narrative is a powerful essay format, as your reader experiences the events, your thoughts, and your emotions with you . This structure is ideal for a specific experience involving extensive internal dialogue, emotions, and reflections.

Here’s an example:

The morning of the Model United Nation conference, I walked into Committee feeling confident about my research. We were simulating the Nuremberg Trials – a series of post-World War II proceedings for war crimes – and my portfolio was of the Soviet Judge Major General Iona Nikitchenko. Until that day, the infamous Nazi regime had only been a chapter in my history textbook; however, the conference’s unveiling of each defendant’s crimes brought those horrors to life. The previous night, I had organized my research, proofread my position paper and gone over Judge Nikitchenko’s pertinent statements. I aimed to find the perfect balance between his stance and my own.

As I walked into committee anticipating a battle of wits, my director abruptly called out to me. “I’m afraid we’ve received a late confirmation from another delegate who will be representing Judge Nikitchenko. You, on the other hand, are now the defense attorney, Otto Stahmer.” Everyone around me buzzed around the room in excitement, coordinating with their allies and developing strategies against their enemies, oblivious to the bomb that had just dropped on me. I felt frozen in my tracks, and it seemed that only rage against the careless delegate who had confirmed her presence so late could pull me out of my trance. After having spent a month painstakingly crafting my verdicts and gathering evidence against the Nazis, I now needed to reverse my stance only three hours before the first session.

Gradually, anger gave way to utter panic. My research was fundamental to my performance, and without it, I knew I could add little to the Trials. But confident in my ability, my director optimistically recommended constructing an impromptu defense. Nervously, I began my research anew. Despite feeling hopeless, as I read through the prosecution’s arguments, I uncovered substantial loopholes. I noticed a lack of conclusive evidence against the defendants and certain inconsistencies in testimonies. My discovery energized me, inspiring me to revisit the historical overview in my conference “Background Guide” and to search the web for other relevant articles. Some Nazi prisoners had been treated as “guilty” before their court dates. While I had brushed this information under the carpet while developing my position as a judge, it now became the focus of my defense. I began scratching out a new argument, centered on the premise that the allied countries had violated the fundamental rule that, a defendant was “not guilty” until proven otherwise.

At the end of the three hours, I felt better prepared. The first session began, and with bravado, I raised my placard to speak. Microphone in hand, I turned to face my audience. “Greetings delegates. I, Otto Stahmer would like to…….” I suddenly blanked. Utter dread permeated my body as I tried to recall my thoughts in vain. “Defence Attorney, Stahmer we’ll come back to you,” my Committee Director broke the silence as I tottered back to my seat, flushed with embarrassment. Despite my shame, I was undeterred. I needed to vindicate my director’s faith in me. I pulled out my notes, refocused, and began outlining my arguments in a more clear and direct manner. Thereafter, I spoke articulately, confidently putting forth my points. I was overjoyed when Secretariat members congratulated me on my fine performance.

Going into the conference, I believed that preparation was the key to success. I wouldn’t say I disagree with that statement now, but I believe adaptability is equally important. My ability to problem-solve in the face of an unforeseen challenge proved advantageous in the art of diplomacy. Not only did this experience transform me into a confident and eloquent delegate at that conference, but it also helped me become a more flexible and creative thinker in a variety of other capacities. Now that I know I can adapt under pressure, I look forward to engaging in activities that will push me to be even quicker on my feet.

This essay is an excellent example of in-the-moment narration. The student openly shares their internal state with us — we feel their anger and panic upon the reversal of roles. We empathize with their emotions of “utter dread” and embarrassment when they’re unable to speak.

For in-the-moment essays, overloading on descriptions is a common mistake students make. This writer provides just the right amount of background and details to help us understand the situation, however, and balances out the actual event with reflection on the significance of this experience.

One main area of improvement is that the writer sometimes makes explicit statements that could be better illustrated through their thoughts, actions, and feelings. For instance, they say they “spoke articulately” after recovering from their initial inability to speak, and they also claim that adaptability has helped them in other situations. This is not as engaging as actual examples that convey the same meaning. Still, this essay overall is a strong example of in-the-moment narration, and gives us a relatable look into the writer’s life and personality.

2. Narrative told over an extended period of time

In this essay structure, you share a story that takes place across several different experiences. This narrative style is well-suited for any story arc with multiple parts. If you want to highlight your development over time, you might consider this structure.

When I was younger, I was adamant that no two foods on my plate touch. As a result, I often used a second plate to prevent such an atrocity. In many ways, I learned to separate different things this way from my older brothers, Nate and Rob. Growing up, I idolized both of them. Nate was a performer, and I insisted on arriving early to his shows to secure front row seats, refusing to budge during intermission for fear of missing anything. Rob was a three-sport athlete, and I attended his games religiously, waving worn-out foam cougar paws and cheering until my voice was hoarse. My brothers were my role models. However, while each was talented, neither was interested in the other’s passion. To me, they represented two contrasting ideals of what I could become: artist or athlete. I believed I had to choose.

And for a long time, I chose athlete. I played soccer, basketball, and lacrosse and viewed myself exclusively as an athlete, believing the arts were not for me. I conveniently overlooked that since the age of five, I had been composing stories for my family for Christmas, gifts that were as much for me as them, as I loved writing. So when in tenth grade, I had the option of taking a creative writing class, I was faced with a question: could I be an athlete and a writer? After much debate, I enrolled in the class, feeling both apprehensive and excited. When I arrived on the first day of school, my teacher, Ms. Jenkins, asked us to write down our expectations for the class. After a few minutes, eraser shavings stubbornly sunbathing on my now-smudged paper, I finally wrote, “I do not expect to become a published writer from this class. I just want this to be a place where I can write freely.”

Although the purpose of the class never changed for me, on the third “submission day,” – our time to submit writing to upcoming contests and literary magazines – I faced a predicament. For the first two submission days, I had passed the time editing earlier pieces, eventually (pretty quickly) resorting to screen snake when hopelessness made the words look like hieroglyphics. I must not have been as subtle as I thought, as on the third of these days, Ms. Jenkins approached me. After shifting from excuse to excuse as to why I did not submit my writing, I finally recognized the real reason I had withheld my work: I was scared. I did not want to be different, and I did not want to challenge not only others’ perceptions of me, but also my own. I yielded to Ms. Jenkin’s pleas and sent one of my pieces to an upcoming contest.

By the time the letter came, I had already forgotten about the contest. When the flimsy white envelope arrived in the mail, I was shocked and ecstatic to learn that I had received 2nd place in a nationwide writing competition. The next morning, however, I discovered Ms. Jenkins would make an announcement to the whole school exposing me as a poet. I decided to own this identity and embrace my friends’ jokes and playful digs, and over time, they have learned to accept and respect this part of me. I have since seen more boys at my school identifying themselves as writers or artists.

I no longer see myself as an athlete and a poet independently, but rather I see these two aspects forming a single inseparable identity – me. Despite their apparent differences, these two disciplines are quite similar, as each requires creativity and devotion. I am still a poet when I am lacing up my cleats for soccer practice and still an athlete when I am building metaphors in the back of my mind – and I have realized ice cream and gummy bears taste pretty good together.

The timeline of this essay spans from the writer’s childhood all the way to sophomore year, but we only see key moments along this journey. First, we get context for why the writer thought he had to choose one identity: his older brothers had very distinct interests. Then, we learn about the student’s 10th grade creative writing class, writing contest, and results of the contest. Finally, the essay covers the writers’ embarrassment of his identity as a poet, to gradual acceptance and pride in that identity.

This essay is a great example of a narrative told over an extended period of time. It’s highly personal and reflective, as the piece shares the writer’s conflicting feelings, and takes care to get to the root of those feelings. Furthermore, the overarching story is that of a personal transformation and development, so it’s well-suited to this essay structure.

3. Series of anecdotes, or montage

This essay structure allows you to focus on the most important experiences of a single storyline, or it lets you feature multiple (not necessarily related) stories that highlight your personality. Montage is a structure where you piece together separate scenes to form a whole story. This technique is most commonly associated with film. Just envision your favorite movie—it likely is a montage of various scenes that may not even be chronological.

Night had robbed the academy of its daytime colors, yet there was comfort in the dim lights that cast shadows of our advances against the bare studio walls. Silhouettes of roundhouse kicks, spin crescent kicks, uppercuts and the occasional butterfly kick danced while we sparred. She approached me, eyes narrowed with the trace of a smirk challenging me. “Ready spar!” Her arm began an upward trajectory targeting my shoulder, a common first move. I sidestepped — only to almost collide with another flying fist. Pivoting my right foot, I snapped my left leg, aiming my heel at her midsection. The center judge raised one finger.

There was no time to celebrate, not in the traditional sense at least. Master Pollard gave a brief command greeted with a unanimous “Yes, sir” and the thud of 20 hands dropping-down-and-giving-him-30, while the “winners” celebrated their victory with laps as usual.

Three years ago, seven-thirty in the evening meant I was a warrior. It meant standing up straighter, pushing a little harder, “Yes, sir” and “Yes, ma’am”, celebrating birthdays by breaking boards, never pointing your toes, and familiarity. Three years later, seven-thirty in the morning meant I was nervous.

The room is uncomfortably large. The sprung floor soaks up the checkerboard of sunlight piercing through the colonial windows. The mirrored walls further illuminate the studio and I feel the light scrutinizing my sorry attempts at a pas de bourrée , while capturing the organic fluidity of the dancers around me. “ Chassé en croix, grand battement, pique, pirouette.” I follow the graceful limbs of the woman in front of me, her legs floating ribbons, as she executes what seems to be a perfect ronds de jambes. Each movement remains a negotiation. With admirable patience, Ms. Tan casts me a sympathetic glance.

There is no time to wallow in the misery that is my right foot. Taekwondo calls for dorsiflexion; pointed toes are synonymous with broken toes. My thoughts drag me into a flashback of the usual response to this painful mistake: “You might as well grab a tutu and head to the ballet studio next door.” Well, here I am Master Pollard, unfortunately still following your orders to never point my toes, but no longer feeling the satisfaction that comes with being a third degree black belt with 5 years of experience quite literally under her belt. It’s like being a white belt again — just in a leotard and ballet slippers.

But the appetite for new beginnings that brought me here doesn’t falter. It is only reinforced by the classical rendition of “Dancing Queen” that floods the room and the ghost of familiarity that reassures me that this new beginning does not and will not erase the past. After years spent at the top, it’s hard to start over. But surrendering what you are only leads you to what you may become. In Taekwondo, we started each class reciting the tenets: honor, courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control, courage, humility, and knowledge, and I have never felt that I embodied those traits more so than when I started ballet.

The thing about change is that it eventually stops making things so different. After nine different schools, four different countries, three different continents, fluency in Tamil, Norwegian, and English, there are more blurred lines than there are clear fragments. My life has not been a tactfully executed, gold medal-worthy Taekwondo form with each movement defined, nor has it been a series of frappés performed by a prima ballerina with each extension identical and precise, but thankfully it has been like the dynamics of a spinning back kick, fluid, and like my chances of landing a pirouette, unpredictable.

This essay takes a few different anecdotes and weaves them into a coherent narrative about the writer’s penchant for novel experiences. We’re plunged into her universe, in the middle of her Taekwondo spar, three years before the present day. She then transitions into a scene in a ballet studio, present day. By switching from past tense to present tense, the writer clearly demarcates this shift in time.

The parallel use of the spoken phrase “Point” in the essay ties these two experiences together. The writer also employs a flashback to Master Pollard’s remark about “grabbing a tutu” and her habit of dorsiflexing her toes, which further cements the connection between these anecdotes.

While some of the descriptions are a little wordy, the piece is well-executed overall, and is a stellar example of the montage structure. The two anecdotes are seamlessly intertwined, and they both clearly illustrate the student’s determination, dedication, reflectiveness, and adaptability. The writer also concludes the essay with a larger reflection on her life, many moves, and multiple languages.

Unconventional College Essay Structures

Unconventional essay structures are any that don’t fit into the categories above. These tend to be higher risk, as it’s easier to turn off the admissions officer, but they’re also higher reward if executed correctly.

There are endless possibilities for unconventional structures, but most fall under one of two categories:

1. Playing with essay format

Instead of choosing a traditional narrative format, you might take a more creative route to showcase your interests, writing your essay:

- As a movie script

- With a creative visual format (such as creating a visual pattern with the spaces between your sentences forming a picture)

- As a two-sided Lincoln-Douglas debate

- As a legal brief

- Using song lyrics

2. Linguistic techniques

You could also play with the actual language and sentence structure of your essay, writing it:

- In iambic pentameter

- Partially in your mother tongue

- In code or a programming language

These linguistic techniques are often hybrid, where you write some of the essay with the linguistic variation, then write more of an explanation in English.

Under no circumstances should you feel pressured to use an unconventional structure. Trying to force something unconventional will only hurt your chances. That being said, if a creative structure comes naturally to you, suits your personality, and works with the content of your essay — go for that structure!

←What is a College Application Theme and How Do You Come Up With One?

Want help with your college essays to improve your admissions chances? Sign up for your free CollegeVine account and get access to our essay guides and courses. You can also get your essay peer-reviewed and improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Essay Writing Guide

Essay Format

Last updated on: Jun 16, 2023

Essay Format: Detailed Writing Tips & Examples

By: Nova A.

Reviewed By: Jacklyn H.

Published on: Jan 22, 2019

Essay writing is an inevitable part of a student’s life. Students dread it the most as they get overwhelmed with the thought of crafting several essays in a short amount of time.

What students don’t realize is that writing a good essay isn’t as difficult as it sounds. Academic essays are a product of grouping different ideas, arguments and presenting them logically with the help of a format.

So let’s begin with the blog!

On this Page

What is an Essay Format?

A proper essay format defines a set of guidelines that will be used to create an overall structure and how the elements of your paper will be arranged.

A standard format for essay writing follows a linear approach where each idea is presented to make it more reader-friendly. If you learn how to structure an essay effectively, half of the work will be taken care of.

The essay structure dictates the information presented to the reader and how it will be presented. Your professor defines the essay format that needs to be followed, as it is unique for a different essay.

Formatting an Essay - Standard Guidelines

To format an essay properly, you must have a proper structure, including an introduction, thesis statement, body of your essay, and conclusion. Also, a title page, works cited page, text capitalization, proper citations, and in-text citations using MLA or APA format.

Here, we have discussed the standard essay formatting guidelines that you should follow.

- The one-inch margin on all sides of the page.

- Line spacing (e.g., single spacing or double spacing).

- Specific font style and size like New Times Roman 12pt.

- Page headers containing the author’s last name, page numbers, and essay title.

- Heading and subheading.

- The indentation should be half an inch.

How to Format an Essay Title Page?

When writing a paper’s title page, keep in mind the following guidelines for different formatting styles:

MLA Style Essay Format

- Use double-spacing. Do not single-space your page

- Use 12 pt. font, Times New Roman font style

- Write your high school/college name centered and top

- Title of your essay, centered. Followed by a subtitle

- Your name, course name and number, your instructor’s name, and the submission date

Check out this video to learn how to setup your MLA format essay!

APA Essay Format

- Running head - TITLE 1 (written in ALL CAPS)

- 1” margins from all sides of the page

- Times New Roman, 12 pt. size font

- Title of your essay

- Name of your institute

Chicago Essay Format

- Center the title of your research paper.

- Center your name directly under the title.

- Your teacher's name, the course title, and the date should be written in three lines.

- Use Times or Times New Roman 12 pt font

- Do not put a page number

Formatting the First Page of an Essay

Consider the following tips to format the first page of your essay.

- Add the header to write your last name and the page number. The header goes on the right-hand corner of the page, leaving half-inch space from the top. This holds for all pages of the essay except for the works cited page.

- In the upper left-hand corner, state your name, instructor’s name, followed by the course, and the date.

- Write the title in the center.

- Use double-space and start writing the essay.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Essay Outline Format

A typical essay is a five-paragraph essay with an introduction, body, and conclusion. Here, the body comprises three paragraphs that hold the main argument, ideas, and supporting evidence.

Once you get the hang of crafting such essays, writing longer, complex essays will become simpler. A 5 paragraph essay format looks like this:

Introduction

- Start your introduction by introducing your topic, provide some background information on it.

- Use a linking sentence to connect it with the thesis.

- Your thesis statement should provide a description of the paper and the main argument.

- Keep the font size 12, Times New Roman.

Body Paragraphs

In each body paragraph, highlight and discuss a separate idea. Start with a topic sentence and provide supporting facts and evidence to support it logically. And indent the first line of every body paragraph.

In this section, you summarize the entire paper and restate the thesis statement. Avoid introducing new ideas at this stage of the essay. Instead, give the reader something to ponder over or a call to action.

Don't forget to add the header and the page numbers to every page.

Have a look at the detailed blog about the essay outline to give you a better understanding.

Outline Your Way to Writing Excellence!

How to Cite an Essay?

It is necessary to cite different sources when using someone else’s words in your paper. It could be in the form of a direct quote, paraphrased, or summarized text. To avoid plagiarism and show the reader the authenticity of what you are talking about, you must cite your sources.

There are different citation styles and rules. Make sure to use the one specified by your teacher.

Here we will discuss in-text citations in APA and MLA format. With in-text citations, the sources are cited within the body paragraphs. Let’s have a look at how it is done:

- Author or publisher’s last name, followed by the date and paragraph number.

- List the author name or publisher, date, and page number.

- Include a comma after the author’s name and date.

For example,

“Darwin's theory of evolution is false and inconsistent. (Taylor, 2018, p. 5).”

- Mention the author’s last name.

- It is followed by the page number.

“Darwin's theory of evolution is false and inconsistent. (Taylor, p. 5).”

Chicago Style Format

- Mention the first name of the author, followed by the last name.

- Mention the title of the essay after this.

Albert Einstein, The Meaning of Relativity, (p. 44–45).

To know more regarding the differences between these two citation formats, we have a detailed guide on APA vs. MLA that will help you clarify the concepts further.

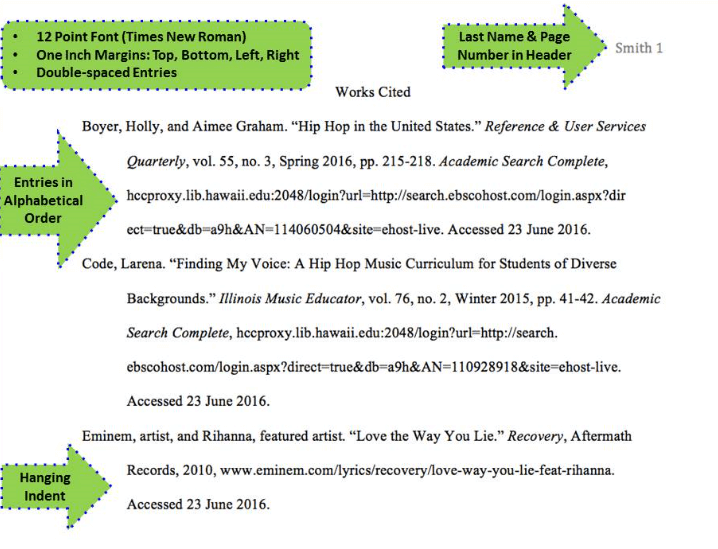

How to Draft the Works Cited Page?

Once you are done writing your essay, the last page is for the works cited. Here you enlist all the sources used to write the essay.

- Arrange the sources in alphabetical order.

- Use double spaces for the entire list.

- Use hanging indention.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Essay Format Examples

To increase your understanding of the format required for different essay types and formats, we have added a few examples. Below are sample essays with the proper essay format that you can use.

College Essay Format Template

MLA Format Essay Example

Short Essay Format Example

Essay Format For University

Different types of Essays Format:

Argumentative Essay Format

Persuasive Essay Format

Narrative Essay Format

Expository Essay Format

Compare and Contrast Essay Format

Descriptive Essay Format

If you are still confused about the essay writing format, it is advisable to seek professional assistance. The expert essay writers at 5StarEssays.com are equipped to draft an essay according to different formatting styles.

All you have to do is to reach out to them and request ‘ write an essay for me ’ In return, you will get an A-grade-worthy paper in no time.

Place your order now and get rid of all your academic worries.

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- How to Write an Essay - A Complete Guide with Examples

- The Art of Effective Writing: Thesis Statements Examples and Tips

- Writing a 500 Word Essay - Easy Guide

- What is a Topic Sentence - An Easy Guide with Writing Steps & Examples

- A Complete Essay Outline - Guidelines and Format

- 220 Best Transition Words for Essays

- How to Write a Conclusion - Examples & Tips

- Essay Topics: 100+ Best Essay Topics for your Guidance

- How to Title an Essay: A Step-by-Step Guide for Effective Titles

- How to Write a Perfect 1000 Word Essay

- How To Make An Essay Longer - Easy Guide For Beginners

- Learn How to Start an Essay Effectively with Easy Guidelines

- Types of Sentences With Examples

- Hook Examples: How to Start Your Essay Effectively

- Essay Writing Tips - Essential Do’s and Don’ts to Craft Better Essays

- How To Write A Thesis Statement - A Step by Step Guide

- Art Topics - 200+ Brilliant Ideas to Begin With

- Writing Conventions and Tips for College Students

People Also Read

- compare and contrast essay topics

- research paper topics

- persuasive speech topics

- types of research

- essay writing service

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

- By Akshat Biyani

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

What are the Hardest GCSEs? Should You Avoid or Embrace Them?

- By Clarissa Joshua

1:1 tutoring to unlock the full potential of your child

More great reads:.

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

A clear, arguable thesis will tell your readers where you are going to end up, but it can also help you figure out how to get them there. Put your thesis at the top of a blank page and then make a list of the points you will need to make to argue that thesis effectively.

For example, consider this example from the thesis handout : While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake”(54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well”(51) is less convincing.

To argue this thesis, the author needs to do the following:

- Show what is persuasive about Sandel’s claims about the problems with striving for perfection.

- Show what is not convincing about Sandel’s claim that we can clearly distinguish between medically necessary enhancements and other enhancements.

Once you have broken down your thesis into main claims, you can then think about what sub-claims you will need to make in order to support each of those main claims. That step might look like this:

- Evidence that Sandel provides to support this claim

- Discussion of why this evidence is convincing even in light of potential counterarguments

- Discussion of cases when medically necessary enhancement and non-medical enhancement cannot be easily distinguished

- Analysis of what those cases mean for Sandel’s argument

- Consideration of counterarguments (what Sandel might say in response to this section of your argument)

Each argument you will make in an essay will be different, but this strategy will often be a useful first step in figuring out the path of your argument.

Strategy #2: Use subheadings, even if you remove them later

Scientific papers generally include standard subheadings to delineate different sections of the paper, including “introduction,” “methods,” and “discussion.” Even when you are not required to use subheadings, it can be helpful to put them into an early draft to help you see what you’ve written and to begin to think about how your ideas fit together. You can do this by typing subheadings above the sections of your draft.

If you’re having trouble figuring out how your ideas fit together, try beginning with informal subheadings like these:

- Introduction

- Explain the author’s main point

- Show why this main point doesn’t hold up when we consider this other example

- Explain the implications of what I’ve shown for our understanding of the author

- Show how that changes our understanding of the topic

For longer papers, you may decide to include subheadings to guide your reader through your argument. In those cases, you would need to revise your informal subheadings to be more useful for your readers. For example, if you have initially written in something like “explain the author’s main point,” your final subheading might be something like “Sandel’s main argument” or “Sandel’s opposition to genetic enhancement.” In other cases, once you have the key pieces of your argument in place, you will be able to remove the subheadings.

Strategy #3: Create a reverse outline from your draft

While you may have learned to outline a paper before writing a draft, this step is often difficult because our ideas develop as we write. In some cases, it can be more helpful to write a draft in which you get all of your ideas out and then do a “reverse outline” of what you’ve already written. This doesn’t have to be formal; you can just make a list of the point in each paragraph of your draft and then ask these questions:

- Are those points in an order that makes sense to you?

- Are there gaps in your argument?

- Do the topic sentences of the paragraphs clearly state these main points?

- Do you have more than one paragraph that focuses on the same point? If so, do you need both paragraphs?

- Do you have some paragraphs that include too many points? If so, would it make more sense to split them up?

- Do you make points near the end of the draft that would be more effective earlier in your paper?

- Are there points missing from this draft?

- picture_as_pdf Tips for Organizing Your Essay

Academic Editing and Proofreading

- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Journal Article Proofreading: Process, Cost, & Checklist

- The A–Z of Dissertation Editing: Standard Rates & Involved Steps

- Research Paper Editing | Guide to a Perfect Research Paper

- Dissertation Proofreading | Definition & Standard Rates

- Thesis Proofreading | Definition, Importance & Standard Pricing

- Research Paper Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Essay Proofreading | Options, Cost & Checklist

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 2024’s Best Proofreaders for Authors, Students & Businesses

- Top 10 English Correctors to Perfect Your Text in 2024

- Top 10 Essay Editing Services of 2024

Academic Research

- Research Paper Outline: Templates & Examples

- How to Write a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- Research Methodology Guide: Writing Tips, Types, & Examples

- The 10 Best Essential Resources for Academic Research

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- Sampling Methods Guide: Types, Strategies, and Examples

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

Academic Writing & Publishing

- Difference Between Paper Editing and Peer Review

- What are the different types of peer review?

- How to deal with rejection from a journal?

- Editing and Proofreading Academic Papers: A Short Guide

- How to Carry Out Secondary Research

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Checklist: Is my Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- Types of Research Articles to Boost Your Research Profile

- 8 Types of Peer Review Processes You Should Know

- The Ethics of Academic Research

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- How to Improve Your Scientific Writing: A Short Guide

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- The A-Z Of Publishing Your Article in A Journal

- What is Journal Article Editing? 3 Reasons You Need It

- 5 Powerful Personal Statement Examples (Template Included)

- Complete Guide to MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Book in APA Style | Format & Examples

- How to Start a Research Paper | Step-by-step Guide

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2024

- Academic Writing in 2024: 5 Key Dos & Don’ts + Examples

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- What Is an Open Access Journal? 10 Myths Busted!

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources: Definition, Types & Examples

- How To Write a College Admissions Essay That Stands Out

- How to Write a Dissertation & Thesis Conclusion (+ Examples)

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- What Is Predatory Publishing and How to Avoid It!

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Dissertation & Thesis Introduction

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best AI Conclusion Generators (Features & Pricing)

- Additional Resources

- Plagiarism: How to avoid it in your thesis?

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- The 10 Best Citation Generators in 2024 | Free & Paid Plans!

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Citation and Referencing

- Citing References: APA, MLA, and Chicago

- How to Cite Sources in the MLA Format

- MLA Citation Examples: Cite Essays, Websites, Movies & More

- Citations and References: What Are They and Why They Matter

- APA Headings & Subheadings | Formatting Guidelines & Examples

- Formatting an APA Reference Page | Template & Examples

- Research Paper Format: APA, MLA, & Chicago Style

- How to Create an MLA Title Page | Format, Steps, & Examples

- How to Create an MLA Header | Format Guidelines & Examples

- MLA Annotated Bibliography | Guidelines and Examples

- APA Website Citation (7th Edition) Guide | Format & Examples

- APA Citation Examples: The Bible, TED Talk, PPT & More

- APA Header Format: 5 Steps & Running Head Examples

- APA Title Page Format Simplified | Examples + Free Template

- How to Write an Abstract in MLA Format: Tips & Examples

- 10 Best Free Plagiarism Checkers of 2024 [100% Free Tools]

- 5 Reasons to Cite Your Sources Properly | Avoid Plagiarism!

- Dissertation Writing Guide

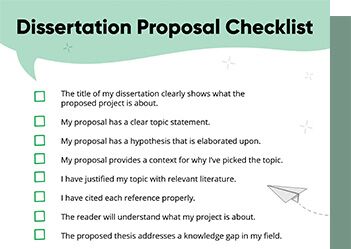

- Writing a Dissertation Proposal

- The Acknowledgments Section of a Dissertation

- The Table of Contents Page of a Dissertation

- The Introduction Chapter of a Dissertation

- The Literature Review of a Dissertation

- The Only Dissertation Toolkit You’ll Ever Need!

- 5 Thesis Writing Tips for Master Procrastinators

- How to Write a Dissertation | 5 Tips from Academic Editors

- The Title Page of a Dissertation

- The 5 Things to Look for in a Dissertation Editing Service

- Top 10 Dissertation Editing & Proofreading Services

- Why is it important to add references to your thesis?

- Thesis Editing | Definition, Scope & Standard Rates

- Expert Formatting Tips on MS Word for Dissertations

- A 7-Step Guide on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- 350 Best Dissertation Topic Ideas for All Streams in 2024

- A Guide on How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- Dissertation Defense: What to Expect and How to Prepare

- Essay Writing Guide

- Essential Research Tips for Essay Writing

- What Is a Mind Map? Free Mind Map Templates & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Outline: 5 Examples & Free Template

- How to Write an Essay Header: MLA and APA Essay Headers

What Is an Essay? Structure, Parts, and Types

- How to Write an Essay in 8 Simple Steps (Examples Included)

- 8 Types of Essays | Quick Summary with Examples

- Expository Essays | Step-by-Step Manual with Examples

- Narrative Essay | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay (Examples Included)

- Guide to a Perfect Descriptive Essay [Examples & Outline Included]

- How to Start an Essay: 4 Introduction Paragraph Examples

- How to Write a Conclusion for an Essay (Examples Included!)

- How to Write an Impactful Personal Statement (Examples Included)

- Literary Analysis Essay: 5 Steps to a Perfect Assignment

- Compare and Contrast Essay | Quick Guide with Examples

- Top 10 Essay Writing Tools in 2024 | Plan, Write, Get Feedback

- Top AI Essay Writers in 2024: 10 Must-Haves

- 100 Best College Essay Topics & How to Pick the Perfect One!

- College Essay Format: Tips, Examples, and Free Template

- Structure of an Essay: 5 Tips to Write an Outstanding Essay

Still have questions? Leave a comment

Add Comment

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Need editing and proofreading services.

- Tags: Academic Writing , Essay , Essay Writing

Writing an effective and impactful essay is crucial to your academic or professional success. Whether it’s getting into the college of your dreams or scoring high on a major assignment, writing a well-structured essay will help you achieve it all. But before you learn how to write an essay , you need to know its basic components.

In this article, we will understand what an essay is, how long it should be, and its different parts and types. We will also take a detailed look at relevant examples to better understand the essay structure.

Get an A+ with our essay editing and proofreading services! Learn more

What is an essay?

An essay is a concise piece of nonfiction writing that aims to either inform the reader about a topic or argue a particular perspective. It can either be formal or informal in nature. Most academic essays are highly formal, whereas informal essays are commonly found in journal entries, social media, or even blog posts.

As we can see from this essay definition, the beauty of essays lies in their versatility. From the exploration of complex scientific concepts to the history and evolution of everyday objects, they can cover a vast range of topics.

How long is an essay?

The length of an essay can vary from a few hundred to several thousand words but typically falls between 500–5,000 words. However, there are exceptions to this norm, such as Joan Didion and David Sedaris who have written entire books of essays.

Let’s take a look at the different types of essays and their lengths with the help of the following table:

How many paragraphs are in an essay?

Typically, an essay has five paragraphs: an introduction, a conclusion, and three body paragraphs. However, there is no set rule about the number of paragraphs in an essay.

The number of paragraphs can vary depending on the type and scope of your essay. An expository or argumentative essay may require more body paragraphs to include all the necessary information, whereas a narrative essay may need fewer.

Structure of an essay

To enhance the coherence and readability of your essay, it’s important to follow certain rules regarding the structure. Take a look:

1. Arrange your information from the most simple to the most complex bits. You can start the body paragraph off with a general statement and then move on to specifics.

2. Provide the necessary background information at the beginning of your essay to give the reader the context behind your thesis statement.

3. Select topic statements that provide value, more information, or evidence for your thesis statement.

There are also various essay structures , such as the compare and contrast structure, chronological structure, problem method solution structure, and signposting structure that you can follow to create an organized and impactful essay.

Parts of an essay

An impactful, well-structured essay comes down to three important parts: the introduction, body, and conclusion.

1. The introduction sets the stage for your essay and is typically a paragraph long. It should grab the reader’s attention and give them a clear idea of what your essay will be about.

2. The body is where you dive deeper into your topic and present your arguments and evidence. It usually consists of two paragraphs, but this can vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing.

3. The conclusion brings your essay to a close and is typically one paragraph long. It should summarize the main points of the essay and leave the reader with something to think about.

The length of your paragraphs can vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing. So, make sure you take the time to plan out your essay structure so each section flows smoothly into the next.

Introduction

When it comes to writing an essay, the introduction is a critical component that sets the tone for the entire piece. A well-crafted introduction not only grabs the reader’s attention but also provides them with a clear understanding of what the essay is all about. An essay editor can help you achieve this, but it’s best to know the brief yourself!

Let’s take a look at how to write an attractive and informative introductory paragraph.

1. Construct an attractive hook

To grab the reader’s attention, an opening statement or hook is crucial. This can be achieved by incorporating a surprising statistic, a shocking fact, or an interesting anecdote into the beginning of your piece.

For example, if you’re writing an essay about water conservation you can begin your essay with, “Clean drinking water, a fundamental human need, remains out of reach for more than one billion people worldwide. It deprives them of a basic human right and jeopardizes their health and wellbeing.”

2. Provide sufficient context or background information

An effective introduction should begin with a brief description or background of your topic. This will help provide context and set the stage for your discussion.

For example, if you’re writing an essay about climate change, you start by describing the current state of the planet and the impact that human activity is having on it.

3. Construct a well-rounded and comprehensive thesis statement

A good introduction should also include the main message or thesis statement of your essay. This is the central argument that you’ll be making throughout the piece. It should be clear, concise, and ideally placed toward the end of the introduction.

By including these elements in your introduction, you’ll be setting yourself up for success in the rest of your essay.

Let’s take a look at an example.

Essay introduction example

- Background information

- Thesis statement

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane in 1903 revolutionized the way humans travel and explore the world. Prior to this invention, transportation relied on trains, boats, and cars, which limited the distance and speed of travel. However, the airplane made air travel a reality, allowing people to reach far-off destinations in mere hours. This breakthrough paved the way for modern-day air travel, transforming the world into a smaller, more connected place. In this essay, we will explore the impact of the Wright Brothers’ invention on modern-day travel, including the growth of the aviation industry, increased accessibility of air travel to the general public, and the economic and cultural benefits of air travel.

Body paragraphs

You can persuade your readers and make your thesis statement compelling by providing evidence, examples, and logical reasoning. To write a fool-proof and authoritative essay, you need to provide multiple well-structured, substantial arguments.

Let’s take a look at how this can be done:

1. Write a topic sentence for each paragraph

The beginning of each of your body paragraphs should contain the main arguments that you’d like to address. They should provide ground for your thesis statement and make it well-rounded. You can arrange these arguments in several formats depending on the type of essay you’re writing.

2. Provide the supporting information

The next point of your body paragraph should provide supporting information to back up your main argument. Depending on the type of essay, you can elaborate on your main argument with the help of relevant statistics, key information, examples, or even personal anecdotes.

3. Analyze the supporting information

After providing relevant details and supporting information, it is important to analyze it and link it back to your main argument.

4. Create a smooth transition to the next paragraph

End one body paragraph with a smooth transition to the next. There are many ways in which this can be done, but the most common way is to give a gist of your main argument along with the supporting information with transitory words such as “however” “in addition to” “therefore”.

Here’s an example of a body paragraph.

Essay body paragraph example

- Topic sentence

- Supporting information

- Analysis of the information

- Smooth transition to the next paragraph

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane revolutionized air travel. They achieved the first-ever successful powered flight with the Wright Flyer in 1903, after years of conducting experiments and studying flight principles. Despite their first flight lasting only 12 seconds, it was a significant milestone that paved the way for modern aviation. The Wright Brothers’ success can be attributed to their systematic approach to problem-solving, which included numerous experiments with gliders, the development of a wind tunnel to test their designs, and meticulous analysis and recording of their results. Their dedication and ingenuity forever changed the way we travel, making modern aviation possible.

A powerful concluding statement separates a good essay from a brilliant one. To create a powerful conclusion, you need to start with a strong foundation.

Let’s take a look at how to construct an impactful concluding statement.

1. Restructure your thesis statement

To conclude your essay effectively, don’t just restate your thesis statement. Instead, use what you’ve learned throughout your essay and modify your thesis statement accordingly. This will help you create a conclusion that ties together all of the arguments you’ve presented.

2. Summarize the main points of your essay

The next point of your conclusion consists of a summary of the main arguments of your essay. It is crucial to effectively summarize the gist of your essay into one, well-structured paragraph.

3. Create a lasting impression with your concluding statement

Conclude your essay by including a key takeaway, or a powerful statement that creates a lasting impression on the reader. This can include the broader implications or consequences of your essay topic.

Here’s an example of a concluding paragraph.

Essay conclusion example

- Restated thesis statement

- Summary of the main points

- Broader implications of the thesis statement

The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane forever changed history by paving the way for modern aviation and countless aerospace advancements. Their persistence, innovation, and dedication to problem-solving led to the first successful powered flight in 1903, sparking a revolution in transportation that transformed the world. Today, air travel remains an integral part of our globalized society, highlighting the undeniable impact of the Wright Brothers’ contribution to human civilization.

Types of essays

Most essays are derived from the combination or variation of these four main types of essays . let’s take a closer look at these types.

1. Narrative essay

A narrative essay is a type of writing that involves telling a story, often based on personal experiences. It is a form of creative nonfiction that allows you to use storytelling techniques to convey a message or a theme.

2. Descriptive essay

A descriptive essay aims to provide an immersive experience for the reader by using sensory descriptors. Unlike a narrative essay, which tells a story, a descriptive essay has a narrower scope and focuses on one particular aspect of a story.

3. Argumentative essays

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that aims to persuade the reader to adopt a particular stance based on factual evidence and is one of the most common forms of college essays.

4. Expository essays

An expository essay is a common format used in school and college exams to assess your understanding of a specific topic. The purpose of an expository essay is to present and explore a topic thoroughly without taking any particular stance or expressing personal opinions.

While this article demonstrates what is an essay and describes its types, you may also have other doubts. As experts who provide essay editing and proofreading services , we’re here to help.

Our team has created a list of resources to clarify any doubts about writing essays. Keep reading to write engaging and well-organized essays!

- How to Write an Essay in 8 Simple Steps

- How to Write an Essay Header

- How to Write an Essay Outline

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between an argumentative and an expository essay, what is the difference between a narrative and a descriptive essay, what is an essay format, what is the meaning of essay, what is the purpose of writing an essay.

Found this article helpful?

Leave a Comment: Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Your vs. You’re: When to Use Your and You’re

Your organization needs a technical editor: here’s why, your guide to the best ebook readers in 2024, writing for the web: 7 expert tips for web content writing.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Get carefully curated resources about writing, editing, and publishing in the comfort of your inbox.

How to Copyright Your Book?

If you’ve thought about copyrighting your book, you’re on the right path.

© 2024 All rights reserved

- Terms of service

- Privacy policy

- Self Publishing Guide

- Pre-Publishing Steps

- Fiction Writing Tips

- Traditional Publishing

- Academic Writing and Publishing

- Partner with us

- Annual report

- Website content

- Marketing material

- Job Applicant

- Cover letter

- Resource Center

- Case studies

11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

How do you structure a paragraph in an essay?

If you’re like the majority of my students, you might be getting your basic essay paragraph structure wrong and getting lower grades than you could!