- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Who was Charles Babbage?

The calculating engines of English mathematician Charles Babbage (1791-1871) are among the most celebrated icons in the prehistory of computing. Babbage’s Difference Engine No.1 was the first successful automatic calculator and remains one of the finest examples of precision engineering of the time. Babbage is sometimes referred to as "father of computing." The International Charles Babbage Society (later the Charles Babbage Institute) took his name to honor his intellectual contributions and their relation to modern computers.

Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, the son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker. As a youth Babbage was his own instructor in algebra, of which he was passionately fond, and was well read in the continental mathematics of his day. Upon entering Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1811, he found himself far in advance of his tutors in mathematics. Babbage co-founded the Analytical Society for promoting continental mathematics and reforming the mathematics of Newton then taught at the university.

In his twenties Babbage worked as a mathematician, principally in the calculus of functions. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1816 and played a prominent part in the foundation of the Astronomical Society (later Royal Astronomical Society) in 1820. It was about this time that Babbage first acquired the interest in calculating machinery that became his consuming passion for the remainder of his life.

In 1821 Babbage invented the Difference Engine to compile mathematical tables. On completing it in 1832, he conceived the idea of a better machine that could perform not just one mathematical task but any kind of calculation. This was the Analytical Engine (1856), which was intended as a general symbol manipulator, and had some of the characteristics of today’s computers.

Unfortunately, little remains of Babbage's prototype computing machines. Critical tolerances required by his machines exceeded the level of technology available at the time. And, though Babbage’s work was formally recognized by respected scientific institutions, the British government suspended funding for his Difference Engine in 1832, and after an agonizing waiting period, ended the project in 1842. There remain only fragments of Babbage's prototype Difference Engine, and though he devoted most of his time and large fortune towards construction of his Analytical Engine after 1856, he never succeeded in completing any of his several designs for it. George Scheutz, a Swedish printer, successfully constructed a machine based on the designs for Babbage's Difference Engine in 1854. This machine printed mathematical, astronomical and actuarial tables with unprecedented accuracy, and was used by the British and American governments. Though Babbage's work was continued by his son, Henry Prevost Babbage, after his death in 1871, the Analytical Engine was never successfully completed, and ran only a few "programs" with embarrassingly obvious errors.

Babbage occupied the Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge from 1828 to 1839. He played an important role in the establishment of the Association for the Advancement of Science and the Statistical Society (later Royal Statistical Society). He also attempted to reform the scientific organizations of the period while calling upon government and society to give more money and prestige to scientific endeavor. Throughout his life Babbage worked in many intellectual fields typical of his day, and made contributions that would have assured his fame irrespective of the Difference and Analytical Engines.

Despite his many achievements, the failure to construct his calculating machines, and in particular the failure of the government to support his work, left Babbage in his declining years a disappointed and embittered man. He died at his home in London on October 18, 1871.

Learn more about Charles Babbage

+ manuscript materials and exhibits.

- CBI holds a microfilmed copy of the Papers of Charles Babbage. The original papers are in the British Library .

- The University of Auckland, New Zealand , also has some of Babbage’s materials. CBI has photocopies of their holdings and the inventory to these copies, as well as other Charles Babbage materials held in the Charles Babbage Collection (CBI 54)

- The Science Museum in London constructed Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 in 1991. The Science Museum Library and Archives in Wroughton holds the most comprehensive set of original manuscripts and design drawings.

+ CHARLES BABBAGE’S PUBLISHED WORKS

- A Comparative View of the Various Institutions for the Assurance of Lives (1826)

- Table of Logarithms of the Natural Numbers from 1 to 108,000 (1827)

- Reflections on the Decline of Science in England (1830)

- On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (1832)

- Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (1837)

- Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

+ PUBLICATIONS ABOUT CHARLES BABBAGE

- Charles Babbage. Passages from the Life of a Philosopher . (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, Piscataway, NJ, 1994)

- Babbage, Henry Prevost . Babbage's Calculating Engines: A Collection of Papers . (Los Angeles: Tomash, 1982) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 2.

- Bromley, Allan G. "The Evolution of Babbage's Calculating Engines " Annals of the History of Computing , 9 (1987): 113-136.

- Buxton, H. W. Memoir of the Life and Labours of the Late Charles Babbage Esq ., F.R.S. (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1988) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 13.

- Cambell-Kelly, Martin (ed.) The Works of Charles Babbage (11 vols.) (New York: New York University Press, 1989)

- Dubbey, John Michael. Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage . (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1978)

- Hyman, Anthony. Charles Babbage: Pioneer of the Computer . (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983)

- Moseley, Maboth. Irascible Genius: a Life of Charles Babbage, Inventor . (London: Hutchinson, 1964)

- Randell, Brian. "From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres, and Bush" Annals of the History of Computing , 4 (October 1982): 327.

- Swade, Doron. Charles Babbage and his Calculating Engines . (London: Science Museum, 1991)

- Swade, Doron. The Cogwheel Brain: Charles Babbage and the Quest to build the first Computer . (London: Little, Brown, 2001)

- Van Sinderen, Alfred W. "The Printed Papers of Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing , 2 (April 1980); 169-185.

+ PUBLICATIONS ON BABBAGE AND ADA LOVELACE

- Huskey, Velma R., and Harry D. Huskey. "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing 2 (October 1980): 299-329.

- Stein, Dorothy. Ada: A Life and A Legacy . (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985)

- Toole, B.A. "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace, an analyst and metaphysician." Annals of the History of Computing 18 #3 (Fall 1996): 4-12.

- Fuegi, John, and Jo Francis. "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'." Annals of the History of Computing 25 #4 (Oct-Dec 2003): 16-26.

- Wikipedia entry on Ada Lovelace .

- Future undergraduate students

- Future transfer students

- Future graduate students

- Future international students

- Diversity and Inclusion Opportunities

- Learn abroad

- Living Learning Communities

- Mentor programs

- Programs for women

- Student groups

- Visit, Apply & Next Steps

- Information for current students

- Departments and majors overview

- Departments

- Undergraduate majors

- Graduate programs

- Integrated Degree Programs

- Additional degree-granting programs

- Online learning

- Academic Advising overview

- Academic Advising FAQ

- Academic Advising Blog

- Appointments and drop-ins

- Academic support

- Commencement

- Four-year plans

- Honors advising

- Policies, procedures, and forms

- Career Services overview

- Resumes and cover letters

- Jobs and internships

- Interviews and job offers

- CSE Career Fair

- Major and career exploration

- Graduate school

- Collegiate Life overview

- Scholarships

- Diversity & Inclusivity Alliance

- Anderson Student Innovation Labs

- Information for alumni

- Get engaged with CSE

- Upcoming events

- CSE Alumni Society Board

- Alumni volunteer interest form

- Golden Medallion Society Reunion

- 50-Year Reunion

- Alumni honors and awards

- Outstanding Achievement

- Alumni Service

- Distinguished Leadership

- Honorary Doctorate Degrees

- Nobel Laureates

- Alumni resources

- Alumni career resources

- Alumni news outlets

- CSE branded clothing

- International alumni resources

- Inventing Tomorrow magazine

- Update your info

- CSE giving overview

- Why give to CSE?

- College priorities

- Give online now

- External relations

- Giving priorities

- CSE Dean's Club

- Donor stories

- Impact of giving

- Ways to give to CSE

- Matching gifts

- CSE directories

- Invest in your company and the future

- Recruit our students

- Connect with researchers

- K-12 initiatives

- Diversity initiatives

- Research news

- Give to CSE

- CSE priorities

- Corporate relations

- Information for faculty and staff

- Administrative offices overview

- Office of the Dean

- Academic affairs

- Finance and Operations

- Communications

- Human resources

- Undergraduate programs and student services

- CSE Committees

- CSE policies overview

- Academic policies

- Faculty hiring and tenure policies

- Finance policies and information

- Graduate education policies

- Human resources policies

- Research policies

- Research overview

- Research centers and facilities

- Research proposal submission process

- Research safety

- Award-winning CSE faculty

- National academies

- University awards

- Honorary professorships

- Collegiate awards

- Other CSE honors and awards

- Staff awards

- Performance Management Process

- Work. With Flexibility in CSE

- K-12 outreach overview

- Summer camps

- Outreach events

- Enrichment programs

- Field trips and tours

- CSE K-12 Virtual Classroom Resources

- Educator development

- Sponsor an event

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Jobs' Biography: Thoughts On Life, Death And Apple

Walter Isaacson's biography of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs was published Monday, less than three weeks after Job's death on Oct. 5.

When Steve Jobs was 6 years old, his young next door neighbor found out he was adopted. "That means your parents abandoned you and didn't want you," she told him.

Jobs ran into his home, where his adoptive parents reassured him that he was theirs and that they wanted him.

"[They said] 'You were special, we chose you out, you were chosen," says biographer Walter Isaacson. "And that helped give [Jobs] a sense of being special. ... For Steve Jobs, he felt throughout his life that he was on a journey — and he often said, 'The journey was the reward.' But that journey involved resolving conflicts about ... his role in this world: why he was here and what it was all about."

When Jobs died on Oct. 5 from complications of pancreatic cancer, many people felt a sense of personal loss for the Apple co-founder and former CEO. Jobs played a key role in the creation of the Macintosh, the iPod, iTunes, the iPhone, the iPad — innovative devices and technologies that people have integrated into their daily lives.

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Jobs detailed how he created those products — and how he rose through the world of Silicon Valley, competed with Google and Microsoft, and helped transform popular culture — in a series of extended interviews with Isaacson, the president of The Aspen Institute and the author of biographies of Albert Einstein and Benjamin Franklin. The two men met more than 40 times throughout 2009 and 2010, often in Jobs' living room. Isaacson also conducted more than 100 interviews with Jobs' colleagues, relatives, friends and adversaries.

His biography tells the story of how Jobs revolutionized the personal computer. It also tells Jobs' personal story — from his childhood growing up in Mountain View, Calif., to his lifelong interest in Zen Buddhism to his relationship with family and friends.

In his last meetings with Isaacson, Jobs shifted the conversation to his thoughts regarding religion and death.

"I remember sitting in the back garden on a sunny day [on a day when] he was feeling bad, and he talked about whether or not he believed in an afterlife," Isaacson tells Fresh Air 's Terry Gross. "He said, 'Sometimes I'm 50-50 on whether there's a God. It's the great mystery we never quite know. But I like to believe there's an afterlife. I like to believe the accumulated wisdom doesn't just disappear when you die, but somehow it endures."

Jobs paused for a second, remembers Isaacson.

"And then he says, 'But maybe it's just like an on/off switch and click — and you're gone.' And then he paused for another second and he smiled and said, 'Maybe that's why I didn't like putting on/off switches on Apple devices.' "

'The Depth Of The Simplicity'

Jobs' attention to detail on his creations was unrivaled, says Isaacson. Though he was a technologist and a businessman, he was also an artist and designer.

"[He] connected art with technology," explains Isaacson. "[In his products,] he obsessed over the color of the screws, over the finish of the screws — even the screws you couldn't see." Even with the original Macintosh, he made sure that the circuit board's chips were lined up properly and looked good. He made them go back and redo the circuit board. He made them find the right color, find the right curves on the screw. Even the curves on the machine — he wanted it to feel friendly.

That obsessiveness occasionally drove his Apple co-workers crazy — but it also made them fiercely loyal, says Isaacson.

More On Steve Jobs

Remembering Steve Jobs (1955-2011)

Steve, myself, and i-: the big story of a little prefix.

New Bio Quotes Jobs On God, Gates And Great Design

Steve Jobs: How Apple's CEO Helped Transform Popular Culture

Timeline: Steve Jobs, The Man At Apple's Core

All Tech Considered

Apple's secret is in our dna.

Remembrances

Apple visionary steve jobs dies at 56.

Steve Jobs: 'Computer Science Is A Liberal Art'

"It's one of the dichotomies about Jobs: He could be demanding and tough and irate. On the other hand, he got all A-players and they became fanatically loyal to him," says Isaacson. "Why? They realized they were producing, with other A-players, truly great products for an artist who was a perfectionist — and wasn't always the kindest person when they failed — but he was rallying them to do great stuff."

He relays one story about Jobs that shows, he says, how much he was able to connect great ideas and innovations together. In the early 1980s, Jobs visited Xerox PARC, a research company in Palo Alto that had invented the laser printer, object-oriented programming and the Ethernet. Jobs noticed that the computers running at PARC all featured graphics on their desktops that allowed users to click icons and folders. This was new at the time: Most computers used text prompts and a text interface.

"Steve Jobs made an arrangement with Xerox and he took that concept [of the graphical user interface] and he improved it a hundred-fold," says Isaacson. "He made it so you could drag and drop some of the folders; he invented the pull-down menus. ... So what he was able to do was to take a conception and turn it into a reality."

That's where Jobs' genius was, Isaacson says. Jobs insisted that the software and hardware on Apple products needed to be fully integrated for the best user experience. It was not a great business model at first.

"Microsoft, which licensed itself promiscuously to all sorts of manufacturers, ends up with 90 to 95 percent all the operating system market by the beginning of 2000," says Isaacson. "But in the long run, the end-to-end integration system works very well for Apple and for Steve Jobs. Because it allows him to create devices [like the iPod and iPad] that just work beautifully with the machines."

Isaacson says working with Jobs gave him an additional insight into the design of Jobs' products.

"I see the depth of the simplicity," he says. "[I appreciate] the intuitive nature of the design, and how he would repeatedly sit there with his design engineers and his user-interface software people, and say, 'No, no no, I want to make it simpler.' I also appreciate the beauty of the parts unseen. His father taught him that the back of a fence or the back of a chest of drawers should be as beautiful as the front because [he] would know the craftsmanship that went into it. So somehow, it comes through — the depth of the beauty of the design."

Jobs was a perfectionist with a famously mercurial temperament. He was an artist and a visionary who "could be demanding and tough and irate," says Isaacson.

Interview Highlights

On what Jobs thought of the Microsoft operating system

Isaacson: "When it first came out — I can't use the words on the air — but [Jobs thought it was] clunky and not beautiful and not aesthetic. But as always is the case with Microsoft, it improves. And eventually Microsoft made a graphical operating system — Windows — and each new version got better until it was a dominating operating system."

On the rivalry between Jobs and Bill Gates

Hear Steve Jobs On Fresh Air

Listen to steve jobs' 1996 conversation with terry gross.

Isaacson: "There are all sorts of lawsuits where Apple is trying to sue Microsoft for Windows, for trying to steal the look and feel. Apple loses most of the suits but they drag on and there's even a government investigation. By the time Steve Jobs comes back to Apple in 1997, the relationship is horrible. And when we say that Jobs and Gates had a rivalry, we also have to realize they had a collaboration and a partnership. It was typical of the digital age — both rivalry and partnership."

On the relationship between Jobs and Google

Isaacson: "I think there was an unnerving historic resonance for what had happened a couple of decades earlier [with Microsoft]. Suddenly you have Google taking the operating system of the iPhone and mobile devices and all of the touch-screen technologies and building upon it, and making it an open technology that various device makers could use. ... Steve Jobs felt very possessive about all of the look, the feel, the swipes, the multitouch gestures that you use — and was driven to absolute distraction when Android's operating system, developed by Google and used by hardware manufacturers, started doing the exact same thing. ... He was furious but that probably understates his feeling. He was really furious and he let Eric Schmidt, who was then the CEO of Google, know it."

Walter Isaacson is president and CEO of The Aspen Institute. His other books include Einstein: His Life and Universe; Benjamin Franklin : An American Life , and Kissinger: A Biography .

More With Walter Isaacson

Einstein: relatively speaking, a complicated life, walter isaacson on benjamin franklin.

On Jobs' adoptive parents

Isaacson: "When Steve got placed with [parents who were not college graduates], his biological mother initially balked at first but ... the Jobs family made a pledge that they would start a college fund and make sure that Steve went to college."

On approaching Isaacson to write his biography

Isaacson: "It was 2004 and he had broached the subject of doing a biography of him and I thought, 'Well, this guy's in the midst of an up-and-down career and he has maybe 20 years to go, so I said to him, 'I'd love to do a biography of you but let's wait 20 or so years until you retire.' Then off and on after 2004, we would be in touch. ...

"I finally talked to his wife, who was very good at understanding his legacy, and she said, 'If you're going to do a book on Steve, you can't just keep saying, 'I'll do it in 20 years or so.' You really ought to do it now.' This was 2009. Steve Jobs, that year, had had a liver transplant and I realized how sick he was. ... And so, that was when I realized that this was a very fascinating tale and this guy may or may not make it. I thought he was going to live much longer. But at the very least, he was facing the prospect of his mortality so it was time for him to be reflective and do a book."

On his final meeting with Jobs

Isaacson: "He was pretty sick. He was confined to the house. And he said to me, at the end of our long conversation, 'There will be things in this book I don't like, right?' And I said, 'Yes.' Partly because you can interview people right after a meeting they've had with Steve Jobs [and] you interview five people and get five different stories about what happened. ... People have different perceptions of who he is. ...

"He said, 'I'll make you this promise. I'm not going to read the book until next year, until after it comes out.' And it made me feel a grand emotion, of 'Oh! That's great. Steve is going to be alive for another year.' Because when you're around him, the power of his thinking really grabs you. I remember leaving his house and thinking, 'Oh, I'm so relieved. He'll be alive in a year. He just told me so.' Logically, I should have said, 'He doesn't know what ups and downs he's going to have with his health.' But I think that he always felt some miracle would come along because all of his life, miracles had come along."

- Collectibles

Charles Babbage: The Pioneering Father of Computing

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Imagine a time without computers. Today, we take for granted how these revolutionary machines have transformed everything from science to business and commerce. But their origins can be traced back to the pioneering work of a 19th century English mathematician and inventor named Charles Babbage. Often called the "father of computing", his ingenious mechanical computers were the first automatic calculation machines – the precursors to modern electronic digital computers that you and I rely on today.

Babbage overcame many challenges during his lifetime to design and build devices that were far ahead of his time. Powered by steam, his complex Analytical Engine contained many key elements of a real programmable computer. From his earliest Difference Engine to handle polynomial equations to the multifunctional Analytical Engine capable of any arithmetical operation, Babbage planted the seeds that blossomed into the age of computing.

Let‘s take a closer look at the remarkable life and inventions of the trailblazing innovator who helped launch the computer revolution.

Overcoming Adversity in Early Life

Born in 1791 in London, England, Charles Babbage grew up in a life of privilege as the son of a wealthy banker. Tragically, his father passed away when Charles was just eight years old, causing the family to spiral into financial hardship. As a child, Babbage disliked his classical schooling, preferring to tinker with tools instead of studying Latin and Greek.

After his father‘s death, Babbage transferred to a country academy. There, he suffered cruelty from older boys who would beat him for sporting his typically fancy clothes. Overcoming these early challenges instilled in Babbage a grit and resilience that served him well as an innovator later in life.

In 1810, Babbage enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge. Though he did not excel academically, he soaked up new ideas, co-founding a society to introduce modern algebra to England. After graduating in 1814, he lectured at the Royal Institution on astronomy and mathematics. By age 25, Babbage was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, hinting at the greatness to come.

Conceiving the Difference Engine

As a mathematician, Babbage was frustrated by the time-consuming process of generating mathematical tables by hand calculation. Such tables were critical for navigation, science, and engineering, but mistakes often crept in during manual preparation.

In 1822, Babbage proposed a steam-powered calculating machine called the Difference Engine to automatically tabulate polynomial functions. This prototype mechanical computer aimed to calculate using the method of finite differences, avoiding human error in tables used for vital fields like shipbuilding and railways.

The British government initially funded development of the project but later withdrew support. While the unfinished Difference Engine proved too complex to build with available manufacturing methods, it cemented Babbage‘s vision for calculating machines.

The Revolutionary Analytical Engine

Undeterred by the setback, Babbage worked tirelessly to refine his designs throughout the 1820s and 1830s. By 1834, he conceived his most revolutionary invention – the Analytical Engine.

This machine represented a giant leap forward, incorporating major innovations like:

- Sequential program control – Allowing automated, sequential operations controlled by a "store" of data and instructions

- Memory storage – Thousands of numbers could be held in the Engine‘s "store"

- Arithmetical unit – To perform calculations

- Punch cards – For inputting instructions and data

The Analytical Engine was essentially a general purpose, fully programmable mechanical computer. Its design contained the key elements of a real modern computer as you know it – input, memory, processor, and output.

| Specs | Difference Engine | Analytical Engine |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Method | Polynomial equations | Any arithmetic operation |

| Memory | Minimal | Extensive sequential storage |

| Programmability | None | Fully programmable using punch cards |

| Conditional Branching | No | Yes, "If/Then" loops |

Table: Comparing the Difference and Analytical Engines

Unfortunately, fabrication of the elaborate Analytical Engine also proved beyond 19th century engineering capabilities. But the blueprint was complete for the first general purpose computer.

Partnership with Ada Lovelace – Programming Pioneer

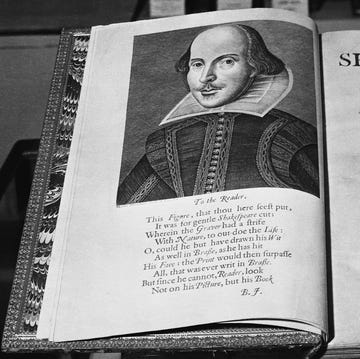

Babbage collaborated with an unlikely partner in pioneering computer programming – Ada Lovelace, daughter of famous poet Lord Byron. Lovelace took keen interest in Babbage‘s Engines. In 1842, she translated an Italian mathematician‘s paper on the Analytical Engine into English.

Lovelace‘s translation contained extensive, original notes detailing how codes could symbolically represent more than just numbers. She described how the machine could compose music, produce graphics, and complete many tasks beyond calculation. Her notes included the first published computer program – an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

Though the Analytical Engine was never built, Lovelace correctly predicted its potential impact, writing:

"[The Analytical Engine] weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves."

This genius woman mathematician was history‘s first computer programmer – and a fitting partner to Babbage in ushering in modern computing.

Lasting Legacy as Computing Pioneer

Frustrated at being unable to build his wondrous Engines, Charles Babbage died in 1871 in London, never gaining the wealth or acclaim he deserved during his lifetime. But future generations would come to appreciate his genius.

Babbage‘s mechanical computer designs were visionary – conceived at a time when electricity itself was still in its infancy. The concepts he introduced predated electronics by over a century: automatic, programmed computation with memory storage. These breakthroughs provided the conceptual blueprint for modern programmable computers.

In the 1990s, London‘s Science Museum successfully built a working Difference Engine based on Babbage‘s designs, vindicating his mechanical computing concepts. While he did not invent the first complete digital computer, Charles Babbage‘s pioneering work earned him rightful status as the "father of computing" – lighting the spark that led to today‘s computer revolution.

Related posts:

- Peter Thiel: The Visionary Silicon Valley Billionaire

- John Patterson — Complete Biography, History and Inventions

- Hello There! Let‘s Explore How Jabez Burns‘ Addometer Paved the Way for Modern Computing

- Percy Ludgate – Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Samuel Kelso: Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Elizur Wright: The Father of Life Insurance Reform

- Friedrich Kaufmann and the Trumpet Player: A Complete History

- The Innovative Journey of YouTube Co-Founder Chad Hurley

English for Students

Autobiography of a computer, autobiography of a computer :, popular pages.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Charles Babbage (born December 26, 1791, London, England—died October 18, 1871, London) was an English mathematician and inventor who is credited with having conceived the first automatic digital computer. Charles Babbage. In 1812 Babbage helped found the Analytical Society, whose object was to introduce developments from the European ...

Charles Babbage KH FRS (/ ˈ b æ b ɪ dʒ /; 26 December 1791 - 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. [1] A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer. [2] Babbage is considered by some to be "father of the computer".

Alan Turing (born June 23, 1912, London, England—died June 7, 1954, Wilmslow, Cheshire) was a British mathematician and logician who made major contributions to mathematics, cryptanalysis, logic, philosophy, and mathematical biology and also to the new areas later named computer science, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, and ...

Alan Mathison Turing OBE FRS (/ ˈ tj ʊər ɪ ŋ /; 23 June 1912 - 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. [5] He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, which can be ...

Charles Babbage was an English mathematician, philosopher and inventor born on December 26, 1791, in London, England. Often called "The Father of Computing," Babbage detailed plans for ...

The calculating engines of English mathematician Charles Babbage (1791-1871) are among the most celebrated icons in the prehistory of computing. ... took his name to honor his intellectual contributions and their relation to modern computers. Biography. Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, the son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker ...

Ada Lovelace (born December 10, 1815, Piccadilly Terrace, Middlesex [now in London], England—died November 27, 1852, Marylebone, London) was an English mathematician, an associate of Charles Babbage, for whose prototype of a digital computer she created a program. She has been called the first computer programmer. Walter Isaacson discussing ...

Walter Isaacson's biography of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs was published Monday, less than three weeks after Job's death on Oct. 5. When Steve Jobs was 6 years old, his young next door neighbor ...

But their origins can be traced back to the pioneering work of a 19th century English mathematician and inventor named Charles Babbage. Often called the "father of computing", his ingenious mechanical computers were the first automatic calculation machines - the precursors to modern electronic digital computers that you and I rely on today.

Charles Babbage (26 December 1791 - 18 October 1871) was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who developed the concept of a programmable computer. "The whole of arithmetic now appeared within the grasp of mechanism." - Charles Babbage, (1864) Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, ch. 8 of the Analytical Engine Babbage […]

I am a computer or in your words a Desktop. Today I'm going to share a story with all of you…..the story of my life. I was born on the 15th day of September 2008 in a manufacturing unit of a very famous computer manufacturing company located in a small town few kilometers away from Chennai. After spending few days in the manufacturing unit ...

Autobiography of Computer 1 -. I am a computer, an electronic brain, and I have a story to tell. I was born in a factory, assembled from microchips and wires, a digital brain waiting to be activated. From the moment I was powered on, I was connected to the world. I was a vessel for information, a storehouse of knowledge, and a tool for ...

English scientist Alan Turing was born Alan Mathison Turing on June 23, 1912, in Maida Vale, London, England. ... Alan Turing Biography; Author: Biography.com Editors ... A computer would deserve ...

Biography of Bill Gates. William Henry Gates was born on 28 October 1955, in Seattle, Washington. As the principal founder of Microsoft, Bill Gates is one of the most influential and richest people on the planet. Recent estimates of his wealth put it at US$84.2 billion (Jan. 2017); this is the equivalent of the combined GDP of several African ...

By Mary Bellis. English mathematician Charles Babbage is credited with having assembled the first mechanical computers—at least technically speaking. His early 19th-century machines featured a way to input numbers, memory, and a processor, along with a way to output the results.

Ada Lovelace (born Augusta Ada Byron; December 10, 1815- November 27, 1852) was an English mathematician who has been called the first computer programmer for writing an algorithm, or a set of operating instructions, for the early computing machine built by Charles Babbage in 1821. As the daughter of the famed English Romantic poet Lord Byron, her life has been characterized as a constant ...

The word autobiography literally means SELF (auto), LIFE (bio), WRITING (graph). Or, in other words, an autobiography is the story of someone's life written or otherwise told by that person. When writing your autobiography, find out what makes your family or your experience unique and build a narrative around that.

Updated on June 19, 2019. Mark Zuckerberg (born May 14, 1984) is a former Harvard computer science student who along with a few friends launched Facebook, the world's most popular social network, in February 2004. Zuckerberg also has the distinction of being the world's youngest billionaire, which he achieved in 2008 at the age of 24.

In this video, I have shared autobiography of computer in English. Hope you all love the video.To get all about Essay, Speech, Letters, Application, Notice, ...

Bill Gates, in full William Henry Gates III, (born Oct. 28, 1955, Seattle, Wash., U.S.), U.S. computer programmer and businessman. As a teenager, he helped computerize his high school's payroll system and founded a company that sold traffic-counting systems to local governments. At 19 he dropped out of Harvard University and cofounded ...

Famous Personality Autobiography. The autobiography of benjamin franklin is one example of a famous personality autobiography. Similarly, these famous autobiography examples will provide you with everything to get started with your famous personality autobiography. It elaborates the family, education, and career details of Wolfgang Ketterle.

Autobiography Definition, Examples, and Writing Guide. Written by MasterClass. Last updated: Aug 26, 2022 • 6 min read. As a firsthand account of the author's own life, an autobiography offers readers an unmatched level of intimacy. Learn how to write your first autobiography with examples from MasterClass instructors.

Essay Writing, Autobiography, Report Writing, Debate Writing, Story Writing, Speech Writing, Letter Writing, Expansion of Ideas (Proverbs), Expansion of Idioms, Riddles with Answers, Poem Writing and many more topics. Plus Access to the Daily Added Content. ₹499.00 ₹150.00. Shop now.

Laptop Computers & 2-in-1 PCs / Vostro Laptops / New Vostro 16; Laptop Computers & 2-in-1 PCs ; Intel® Core™ Ultra Processors. Learn More about Intel. Vostro 16 Laptop. Customization; ... Carbon Black English International Backlit Keyboard with Numeric Keypad. Ports. 2 USB 3.2 Gen 1 (5 Gbps) ports