World’s #1 Research Paper Generator

Over 5,000 research papers generated daily

Have an AI Research and write your Paper in just 5 words

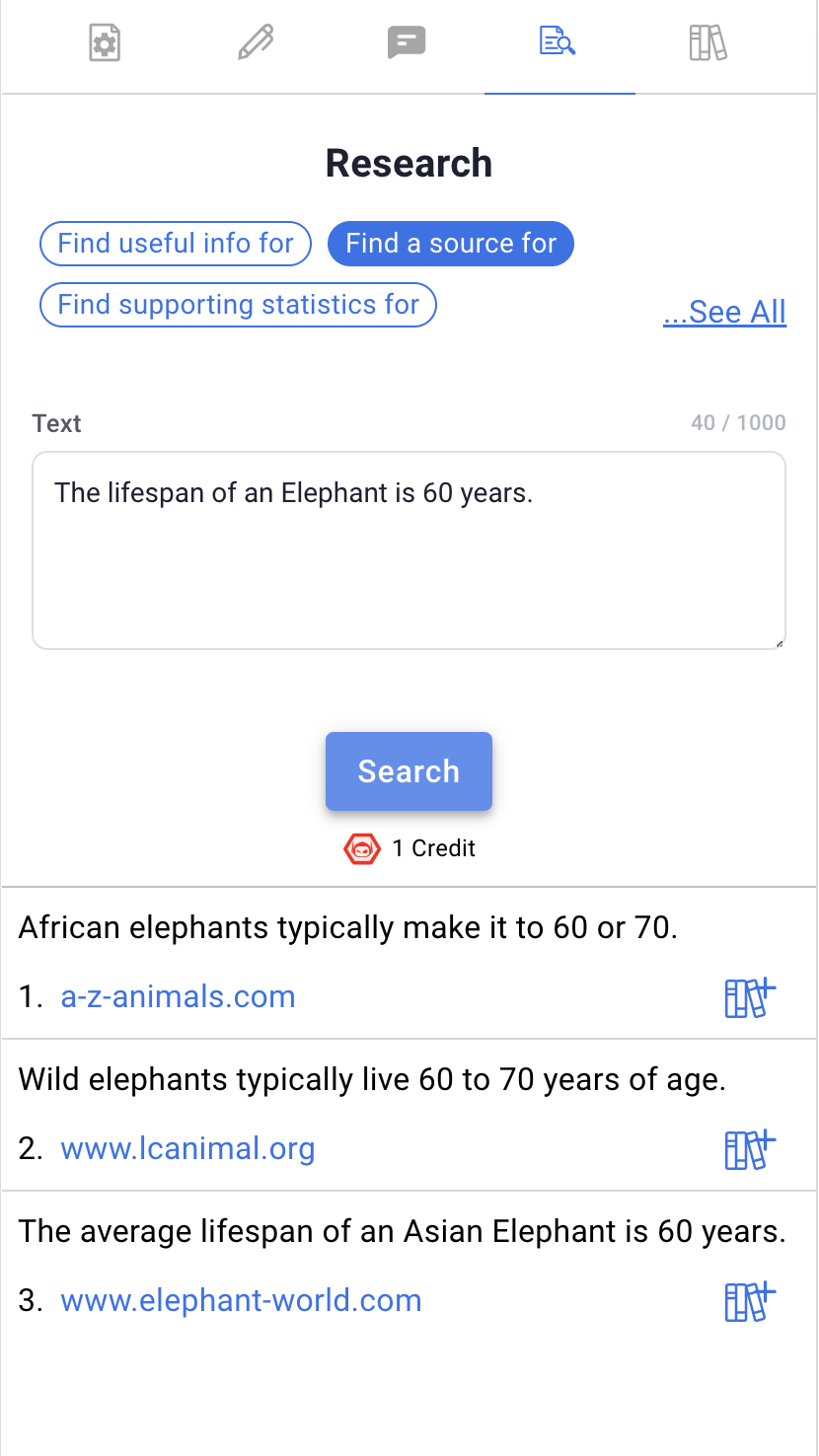

See it for yourself: get your free research paper started with just 5 words, how smodin makes research paper writing easy, instantly find sources for any sentence.

Our AI research tool in the research paper editor interface makes it easy to find a source or fact check any piece of text on the web. It will find you the most relevant or related piece of information and the source it came from. You can quickly add that reference to your document references with just a click of a button. We also provide other modes for research such as “find support statistics”, “find supporting arguments”, “find useful information”, and other research methods to make finding the information you need a breeze. Make research paper writing and research easy with our AI research assistant.

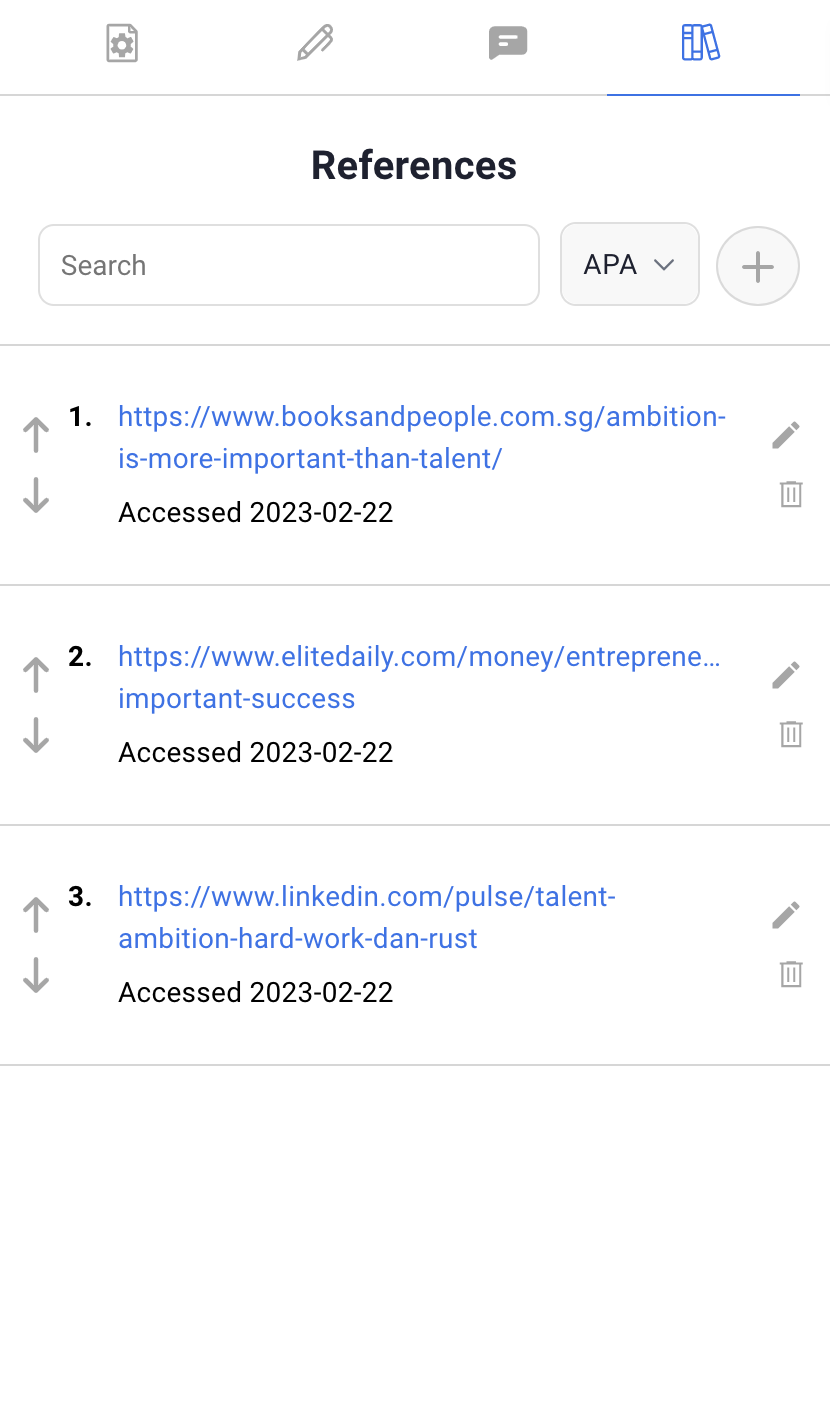

Easily Cite References

Our research paper generator makes citing references in MLA and APA styles for web sources and references an easy task. The research paper writer works by first identifying the primary elements in each source, such as the author, title, publication date, and URL, and then organizing them in the correct format required by the chosen citation style. This ensures that the references are accurate, complete, and consistent. The product provides helpful tools to generate citations and bibliographies in the appropriate style, making it easier for you to document your sources and avoid plagiarism. Whether you’re a student or a professional writer, our research paper generator saves you time and effort in the citation process, allowing you to focus on the content of your work.

Free AI Research Paper Generator & Writer - Say Goodbye to Writer's Block!

Are you struggling with writer's block? Even more so when it comes to your research papers. Do you want to write a paper that excels, but can't seem to find the inspiration to do so? Say goodbye to writer's block with Smodin’s Free AI Research Paper Generator & Writer!

Smodin’s AI-powered tool generates high-quality research papers by analyzing millions of papers and using advanced algorithms to create unique content. All you need to do is input your topic, and Smodin’s Research Paper generator will provide you with a well-written paper in no time.

Why Use Smodin Free AI Research Paper Generator & Writer?

Writing a research paper can be a complicated task, even more so when you have limited time and resources. A research paper generator can help you streamline the process, by quickly finding and organizing relevant sources. With Smodin's research paper generator, you can produce high-quality papers in minutes, giving you more time to focus on analysis and writing

Benefits of Smodin’s Free Research Paper Generator

- Save Time: Smodin AI-powered generator saves you time by providing you with a well-written paper that you can edit and submit.

- Quality Content: Smodin uses advanced algorithms to analyze millions of papers to ensure that the content is of the highest quality.

- Easy to Use: Smodin is easy to use, even if you're not familiar with the topic. It is perfect for students, researchers, and professionals who want to create high-quality content.

How to Write a Research Paper?

All you need is an abstract or a title, and Smodin’s AI-powered software will quickly find sources for any topic or subject you need. With Smodin, you can easily produce multiple sections, including the introduction, discussion, and conclusion, saving you valuable time and effort.

Who can write a Research Paper?

Everyone can! Smodin's research paper generator is perfect for students, researchers, and anyone else who needs to produce high-quality research papers quickly and efficiently. Whether you're struggling with writer's block or simply don't have the time to conduct extensive research, Smodin can help you achieve your goals.

Tips for Using Smodin's Research Paper Generator

With our user-friendly interface and advanced AI algorithms, you can trust Smodin's paper writer to deliver accurate and reliable results every time. While Smodin's research paper generator is designed to be easy to use, there are a few tips you can follow to get the most out of Smodinl. First, be sure to input a clear and concise abstract or title to ensure accurate results. Second, review and edit the generated paper to ensure it meets your specific requirements and style. And finally, use the generated paper as a starting point for your research and writing, or to continue generating text.

The Future of Research Paper Writing

As technology continues to advance, the future of research paper writing is likely to become increasingly automated. With tools like Smodin's research paper generator, researchers and students can save time and effort while producing high-quality work. Whether you're looking to streamline your research process or simply need a starting point for your next paper, Smodin's paper generator is a valuable resource for anyone interested in academic writing.

So why wait? Try Smodin's free AI research paper generator and paper writer today and experience the power of cutting-edge technology for yourself. With Smodin, you can produce high-quality research papers in minutes, saving you time and effort while ensuring your work is of the highest caliber.

© 2024 Smodin LLC

- Argumentative

- Ecocriticism

- Informative

- Explicatory

- Illustrative

- Problem Solution

- Interpretive

- Music Analysis

- All Essay Examples

- Entertainment

- Law, Crime & Punishment

- Artificial Intelligence

- Environment

- Geography & Travel

- Government & Politics

- Nursing & Health

- Information Science and Technology

- All Essay Topics

AI Research Paper Generator

Transform your research journey with groundbreaking ai technology, effortlessly crafting academic papers that meet professional standards..

Streamlining Your Academic Writing Process Using EssayGPT

EssayGPT's AI research paper generator simplifies the process of crafting well-structured, comprehensive research papers. Here is how to do it in simple steps:

- 1. Get started by entering the central theme of your research in the 'Essay Topic' box.

- 2. Add up to five specific keywords related to your research topic to create relevant and focused content.

- 3. Enter your desired format including APA, MLA, or Harvard for accurate citation and formatting.

- 4. Use the 'Outline Suggestions' and 'Essay Title' boxes to tailor the structure and title to your specific needs.

- 5. Pick your target audience, tone of voice, and language. Then, hit the 'Generate' button to create your paper.

Try Our Powerful, All-in-One AI Writing Copilot

Empower your writing with 120+ AI writing tools

Bypass AI detection with 100% undetectable AI content

Create undetectable, plagiarism-free essays with accurate citations

Browser Extension

The all-in-one ChatGPT copilot: rewrite, translate, summarize, Chat with PDF anywhere

Choosing EssayGPT's AI Research Paper Generator: A Cut Above the Rest

When it comes to crafting a research paper, the choice of tools can be a game-changer. With cutting-edge features, EssayGPT's AI research paper generator stands out as a superior choice for researchers seeking an efficient, versatile, and high-quality AI research paper writer.

This AI research paper generator from EssayGPT distinguishes itself from other AI writers for numerous compelling reasons such as:

Advanced AI Capabilities: At the heart of EssayGPT's AI research paper generator lies the integration of both GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 technologies. This dual AI power ensures not only advanced capabilities in generating research content but also guarantees versatility and depth in analysis, making it an unparalleled AI paper writer.

Full Customizability: Unlike standard research paper writers, EssayGPT's AI research paper generator provides complete control over the creation process. Whether it's adjusting the style, format, or specific content requirements, EssayGPT's AI research paper generator caters to all your unique academic needs.

Professional Citations and Reference Format: Catering to diverse academic standards, EssayGPT's AI paper generator offers a variety of professional paper reference formats. From APA to MLA or custom formats, the tool ensures your research paper meets the highest academic criteria.

Multi-Language Support: Breaking language barriers, EssayGPT's research paper writer extends its support to over 30 languages. This feature not only broadens the tool's accessibility but also makes it an invaluable asset for international research communities.

Advanced Context-Aware Technology: Understanding the importance of context in academic writing, EssayGPT's AI research paper generator employs advanced context-aware technology. This ensures that each paper generated is not only relevant but also resonates with the intended research topic, making it more than just an ordinary AI paper generator.

How Can You Benefit From EssayGPT's AI Research Paper Generator?

Embrace the future of research with EssayGPT's AI research paper generator. This tool is not just an advanced AI paper writer; it's a revolution in academic writing. Designed to cater to a diverse range of research needs, it offers an unparalleled blend of efficiency, customization, and quality, ensuring your research stands out.

Let's explore how it can significantly benefit users in the academic and professional fields:

Innovative Idea Cultivation: The AI research paper generator serves as a springboard for your research ideas. It helps conceptualize diverse topics, offering unique perspectives and thought-provoking angles, essential for groundbreaking research papers.

Time-Saving and Cost-Effective Solution: Reduce the hours spent on research and writing significantly. This free tool streamlines the writing process, allowing more focus on analysis and less on structuring, making efficient use of your valuable time and resources.

Simplifying the Writing Journey: Experience a transformed writing process with our AI paper writer. From outlining to drafting, the tool organizes and structures your thoughts, turning complex ideas into well-articulated research papers with ease.

Educational Enhancement: Beyond just generating papers, the AI research paper generator is a learning tool. It exposes users to varied writing styles and structures, enhancing their understanding of academic writing norms and encouraging skill development in research methodology.

EssayGPT AI Research Paper Generator’s Innovations in AI Paper Writing

| 🤖 AI research expertise | Advanced, intelligent paper crafting |

|---|---|

| 📊 Data-driven insights | Incorporates accurate research findings |

| 📝 Seamless writing aid | Efficient, user-friendly interface |

| 🌐 Global language support | Caters to a worldwide audience |

| ✍️ Creative academic solutions | Generates unique, scholarly content |

Expand Your Academic Horizons with HIX.AI's Suite of AI Writing Tools

Research paper summarizer, ai essay writer, essay checker, chatgpt essay writer, essay extender, essay introduction generator, essay paraphraser, essay rewriter, essay outline generator, essay topic generator, dive into a world of inspiration.

- Customer Segmentation Netflix

- Douglas Mcgregor Developed Two Theories That Help Us Understand The Relationship Between People The Organization They Work

- Reasons For The Revolution Of 1848

- Cause And Effect Of Extra-Curricular Activities

- Advantages And Disadvantages Of Xiaomi Wireless Bluetooth 4.1 Music Sport Earbud

- Camus Literary Devices

- Benefits Of Single Sex Schools

- The Major Driving Forces For European Imperialism In Africa

- Business Analysis : Brick And Mortar Stores

- Metamorphosis Kafka Analysis

- Breaking Bad Fits Under The Crime Drama Genre

- Choices In Night By Elie Wiesel

- Cultural Diversity In The United States

- Richer And Poorer Accounting For Inequality, By Jill Lepore

- Racial Bias In Education

- The Pros And Cons Of Jigsaw

1. How does the EssayGPT AI research paper generator ensure data accuracy in the generated papers?

The EssayGPT AI research paper generator utilizes an advanced AI algorithm to fetch relevant and credible information. It employs sophisticated contextual understanding and keyword analysis to maintain accuracy. However, this tool is designed to augment rather than replace comprehensive manual research.

2. How does the EssayGPT AI research paper generator address plagiarism concerns?

The tool employs machine learning algorithms to synthesize information, ensuring each output is unique and original. Additionally, EssayGPT recommends users utilize its plagiarism checker, for thorough plagiarism verification.

3. Can the EssayGPT AI research paper generator handle complex academic disciplines?

Yes, the AI research paper generator is equipped with algorithms capable of handling a wide range of subjects, including advanced and specialized academic disciplines. It understands the complexity of various subjects and structures the research paper accordingly. Users are always advised to review and edit the generated content for precision.

4. What should I do if I find issues with the paper generated by EssayGPT's tool?

If you encounter any issues with the generated paper, you can always modify your inputs and regenerate them for better results. For specific concerns or improvement suggestions, you can always contact our support .

Get High-quality Paper with AI Research Paper Generator

Elevate your academic journey and let our AI research paper generator from EssayGPT turn your ideas into polished, scholarly works. Begin your transformative writing adventure now.

Research Paper Generator: Free + Intuitive

Writing a research paper is one of the most challenging objectives you’ll encounter during your studies. With the help of our research paper generator, you’ll be able to complete this assignment quickly and easily. Let’s see how it works!

- ✅ How to Use

- 🏆 What Is the Best Generator?

- 🔬 Research Paper Definition

- ️✍️ How to Write

- ️🏅 Winning Tips

🔗 References

✅ free research paper generator: how to use.

- Choose your assignment type.

- Type in your topic.

- Indicate how many body paragraphs you need.

- Press “Generate” and receive your perfect research paper just like that.

🏆 What Is the Best Free Research Paper Generator?

With many other AI research generators online, you might wonder, "Why pick this one?”

Well, that’s because our tool is truly the best! It has every feature of a perfect research paper generator:

| 👍 Accessible | It’s free, limitless, and doesn't require registration. |

|---|---|

| 🚀 Advanced | Our generator is based on a powerful GPT language model. |

| 💡 Customizable | You can choose the number of paragraphs for your paper sample. |

| 📚 Informative | We provide additional tips to help the potential user. |

All of these benefits are included in our GPT-powered tool. So, why not try it right now?

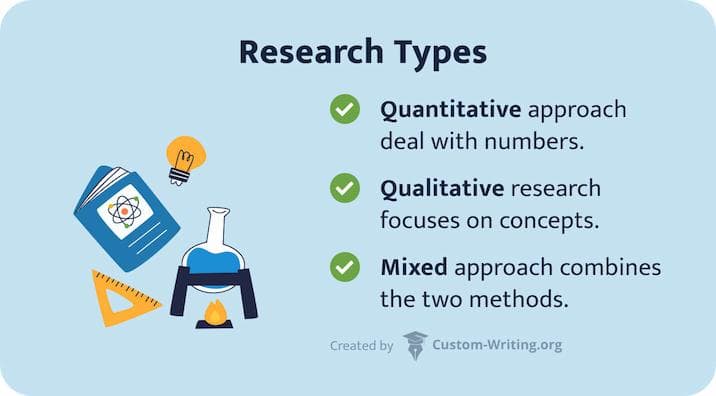

🔬 What Is a Research Paper?

A research paper is an academic work where you provide an in-depth analysis or interpretation of something. Writing a research paper involves expanding your existing knowledge on the topic and purposefully incorporating the expertise of other people who studied it.

The research itself can be quantitative or qualitative :

- Quantitative studies use data that is countable, measurable, and dependent on numbers.

- Qualitative research is descriptive and rooted in interpretation.

Some research papers use a mixed approach combining qualitative and quantitative methods.

Did you know our generator can create research paper samples using any of the above methods? Try it now, and see for yourself!

✍️ How to Write a Research Paper

So, how can you write an outstanding research paper? Check out our handy step-by-step guide below!

1. Get Ready

Before you start writing, you should choose a topic , conduct preliminary research, and build a roadmap for your paper.

When looking for a good topic, follow these tips:

- Pick something you find interesting.

- Scan how much information is available on the chosen topic.

- Avoid topics that are too obvious or complicated.

After you’ve picked a research topic , it’s time to do some digging. For that, go through scientific literature and recent publications. It’s a good idea to use various types of sources, from scholarly articles to books. Make sure to write down any important information in your notes.

Once you’ve learned enough about your topic, you can create an outline . It will serve as a roadmap for your research paper. In your outline:

- Include the key findings and your thoughts on the subject.

- Group the information logically.

- Discard everything you find redundant or irrelevant.

2. Write a Thesis Statement

Using the collected information, write a concise, well-defined thesis statement . To do it, formulate your topic as a question and answer it. This answer will be the key sentence that will determine your work's overall structure and flow.

💡 Pro Tip: Using a thesis generator will help you ace this task.

3. Do the Research

Now, it’s time to conduct your research. While doing it, note the sources of all important information. We also recommend to avoid relying too much on online encyclopedias. They are more likely to contain misinformation than peer-reviewed articles .

After gathering enough data, do the following:

- Expand your outline with details and examples.

- Conduct additional research if necessary.

- Modify your thesis statement to represent your findings more accurately.

4. Draft Your Paper

Once you're done researching and unraveling your thesis, you can start making the first draft. We recommend writing the main body first. Then, you can revise it, add more specifics, and complete the remaining parts.

5. Write the Final Draft

Now, you’re ready to make the final draft. The following checklist will help you ensure everything is perfect:

- Have you appropriately cited the sources ?

- Does every citation follow the proper format?

- Does each paragraph focus on a single topic?

- Have you achieved the primary goal of your research?

- Did you include all the necessary paragraphs?

- Are your arguments logically connected?

6. Proofread and Edit

Finally, proofread your work for grammar, punctuation, appropriate word choice, seamless transitions, sentence structure, and variety. If possible, give yourself a few days after finishing your final draft before making any edits. Doing so will allow you to notice more things and proofread more thoroughly.

🏅 Winning Tips for Research Paper Writing

Want to take your research to the next level? Check out our helpful tips below:

- Always consider your target audience. Adapt your vocabulary and writing style to your readers' degree of experience and understanding. It's best to refrain from employing technical phrases or jargon your audience might not understand.

- Provide definitions for key terms. This way, your readers will understand your research better.

- Employ an active voice. This will make your essay more readable. For instance, instead of writing "the experiment was conducted by the researchers," state "the researchers conducted the experiment."

- Ask for feedback. Have a mentor, professor, or friend review your writing. They can provide insightful advice and recommendations for enhancing coherence and clarity.

And here’s our final tip: use our free research paper generator to get inspiration for your next project! It can assist you with research on any topic absolutely free of charge.

We also recommend using our abstract creator and transition phrase generator to enhance your writing even further.

- Writing a Research Paper: Purdue OWL

- The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Research Paper: Grammarly

- Writing a Research Paper: UW–Madison

- Research Paper Structure: UCSD Psychology

- What Is a Research Paper?: ThoughtCo

Join the academic and scientific writing revolution

Create impactful manuscripts and fast-track journal submissions with our smart writing tools for researchers

Paperpal It

Want practical strategies and expert advice on writing, editing, and submission?

Check our Blog

RAxter is now Enago Read! Enjoy the same licensing and pricing with enhanced capabilities. No action required for existing customers.

Your all in one AI-powered Reading Assistant

A Reading Space to Ideate, Create Knowledge, and Collaborate on Your Research

- Smartly organize your research

- Receive recommendations that cannot be ignored

- Collaborate with your team to read, discuss, and share knowledge

From Surface-Level Exploration to Critical Reading - All in one Place!

Fine-tune your literature search.

Our AI-powered reading assistant saves time spent on the exploration of relevant resources and allows you to focus more on reading.

Select phrases or specific sections and explore more research papers related to the core aspects of your selections. Pin the useful ones for future references.

Our platform brings you the latest research related to your and project work.

Speed up your literature review

Quickly generate a summary of key sections of any paper with our summarizer.

Make informed decisions about which papers are relevant, and where to invest your time in further reading.

Get key insights from the paper, quickly comprehend the paper’s unique approach, and recall the key points.

Bring order to your research projects

Organize your reading lists into different projects and maintain the context of your research.

Quickly sort items into collections and tag or filter them according to keywords and color codes.

Experience the power of sharing by finding all the shared literature at one place.

Decode papers effortlessly for faster comprehension

Highlight what is important so that you can retrieve it faster next time.

Select any text in the paper and ask Copilot to explain it to help you get a deeper understanding.

Ask questions and follow-ups from AI-powered Copilot.

Collaborate to read with your team, professors, or students

Share and discuss literature and drafts with your study group, colleagues, experts, and advisors. Recommend valuable resources and help each other for better understanding.

Work in shared projects efficiently and improve visibility within your study group or lab members.

Keep track of your team's progress by being constantly connected and engaging in active knowledge transfer by requesting full access to relevant papers and drafts.

Find papers from across the world's largest repositories

Testimonials

Privacy and security of your research data are integral to our mission..

Everything you add or create on Enago Read is private by default. It is visible if and when you share it with other users.

You can put Creative Commons license on original drafts to protect your IP. For shared files, Enago Read always maintains a copy in case of deletion by collaborators or revoked access.

We use state-of-the-art security protocols and algorithms including MD5 Encryption, SSL, and HTTPS to secure your data.

- How it Works

- Member Area

“Write your paper 10x faster”

The #1 AI Research Tool for Students, Teachers, Scholars, and those in Academia

Generate study guides, outlines, research topics, key findings, hypotheses, and exam questions in seconds..

Streamline your planning and preparation with the top AI-generated answers for your specific academic field.

How Research Panda Works

1. pick the research template, 2. fill out the form in less than 2 minutes, 3. generate your academic content.

Save Hours and Days of Research Work

What You Get

Topic and idea selection.

Retrieve topics and subtopics, a longside possible ideas to e nforce and expand upon. Simplify and expand any topic or subtopic of reference.

Brainstorm and Outline Build

Have a thought flow built out s o you’re not mentally stuck. C reate a concrete outline and structure f or your research paper.

Research Questions, Gaps, and Hypothesis Generator

Based on a topic and keywords, g et a list of questions, gaps in research, a nd possible hypotheses t o utilize.

Methodology and Techniques Creator

Explain how the qualitative or quantitive approach can be used to address the topic. Get the top data collection practices.

Research Paper and Article Locator

Literature Review – Based on a given topic and keywords, p roduce articles for reference.

Summary and Analysis Generator

Get the main arguments and key findings of a given text. Describe the theoretical framework and methodology used.

Personal Study Guide and Plan Build

Create a step-by-step c omprehensive guide and plan b ased on y our timeframe to study.

Exam Preparation Creator

Generate multiple choice questions based on your given research topic

…ranging in various difficulties.

Book Summarizer

Give the title and author. Condense books into concise and comprehensive summaries for effortless learning.

Lesson Plan Generator

Structured lesson plans for any subject, idea, course, or concept. Just plug in the topic and grade level. AI will provide the rest.

Educational Handout Writer

Efficiently create comprehensive handouts encompassing all the essential information about a particular topic, concept, or subject area for both yourself and a student.

Gaps in Understanding Identifier

Provide your own understanding of a given topic, idea, or concept. An analysis will take place pointing out the gaps in knowledge of the said topic.

Bonus #1: The Quick Learner

Pick the topic, keywords, and main points you want to focus on and learn about. Be broad or specific as need be. Use the 80/20 principle to learn faster than ever.

Bonus #2: The Proofreader

Improvise your writing. Proofread, correct, and get tailored feedback to what you need to do to better your writing. This detailed feedback will give you the steps needed to take next.

Bonus #3: The Detailer

Completely understand a topic, idea, or research point. Have a concept broken down to have a strong mental grasp on it, being able to speak and write on it intelligently.

Why Research Panda?

Enhance your planning and preparation process through the power of comprehensive AI. Discover streamlined templates for study guides and receive tailored writing prompts and answers for each section of your paper that cater to your specific academic field. Research Panda was built for the academic .

Pick a Plan

Optimize your research and writing, get all the ai research tools, built for students, teachers, scholars, and academics.

1. Topic Selection and

Idea Generator

2. Brainstorm and Outline Generator

3. Research Questions, Research Gaps,

and Hypothesis Generator

4. Methodology and Technique Generator

5. Research Paper

and Article Locator Generator

6. Summary and Analysis Generator

7. Study Guide and Plan Generator

8. Exam Preparation Generator

Research Panda works for education levels ranging from high school students to doctoral academics. Nevertheless, it is for any academic looking to further their research in any given field.

Research Panda is capable of generating educational guides, study plans, academic content, and much more. If you can think it, Research Panda can create it. This includes materials related to mathematics, English Language Arts (reading, writing, grammar), science (biology, chemistry, physics), social Studies (history, geography, civics, economics), computer science, political science, and any subject you work in.

To use Research Panda, simply click one of the membership options above to “Try for 3 Days Free” to access the sign up page. From there, you can give Research Panda detailed instructions using any of the 8+ premium AI tools. Once you’ve generated your first AI content, go ahead and edit it to your liking, and copy it for your research use.

Yes! All Research Panda users get unlimited usage and access to all AI tools as long as they are a member. This means you can create as many guides, handouts, article reviews, outlines, and academic content as you’d like.

We offer a 3-day free trial with both membership tiers, Monthly and Quarterly. If you are not 100% satisfied, no worries! Just cancel before your free trial ends. Because of the work in the upkeep of Research Panda, we do not offer any refunds.

Feel free to send us a message using the form below! We will get back to you within 48 hours.

Get in Touch

©2023 by ResearchPanda.io | All Rights Reserved | Site Built by Nathan Schweikart

Research Paper Abstract Generator

Writing the abstract for your research paper, dissertation, or book chapter is usually one of the final steps before you submit your work. It’s also the activity that many students and researchers find most difficult. A strong abstract must be clear, succinct and informative, but how do you decide what to include?

Structuring your abstract

Many journals require the abstract to be structured according to

whereas the abstract for your dissertation or chapter may just be a short narrative paragraph. Either way, the abstract should contain key information from the study and be easy to read. Creating an abstract is as much an art as a science.

Happily, Scholarcy can help by identifying exactly the right information to include in your abstract.

Abstract in numbers

4 steps to generate an abstract with scholarcy, upload your article.

Simply upload your article to Scholarcy Library to generate a summary flashcard that outlines your research and contains the information needed to create your abstract.

View Scholarcy Highlights

The Scholarcy Highlights tab contains 5-7 bullet points comprising the background to the study, the key findings, and the conclusion.

View Scholarcy Summary

If your paper contains standard IMRaD sections, then the Scholarcy Summary will automatically be structured to follow these headings and will include any study objectives that you have written.

And the Study subjects and participants tab extracts key information about study participants, interventions, and quantitative results. Perfect for your abstract!

Try Smart Synopsis

Alternatively, for your dissertation or book chapter, you can use our Smart Synopses tool to create a more naturally flowing, narrative abstract.

What People Are Saying

“Quick processing time, successfully summarized important points.”

“It’s really good for case study analysis, thank you for this too.”

“I love this website so much it has made my research a lot easier thanks!”

“The instant feedback I get from this tool is amazing.”

“Thank you for making my life easier.”

Privacy Overview

Hypothesis Maker Online

Looking for a hypothesis maker? This online tool for students will help you formulate a beautiful hypothesis quickly, efficiently, and for free.

Are you looking for an effective hypothesis maker online? Worry no more; try our online tool for students and formulate your hypothesis within no time.

- 🔎 How to Use the Tool?

- ⚗️ What Is a Hypothesis in Science?

👍 What Does a Good Hypothesis Mean?

- 🧭 Steps to Making a Good Hypothesis

🔗 References

📄 hypothesis maker: how to use it.

Our hypothesis maker is a simple and efficient tool you can access online for free.

If you want to create a research hypothesis quickly, you should fill out the research details in the given fields on the hypothesis generator.

Below are the fields you should complete to generate your hypothesis:

- Who or what is your research based on? For instance, the subject can be research group 1.

- What does the subject (research group 1) do?

- What does the subject affect? - This shows the predicted outcome, which is the object.

- Who or what will be compared with research group 1? (research group 2).

Once you fill the in the fields, you can click the ‘Make a hypothesis’ tab and get your results.

⚗️ What Is a Hypothesis in the Scientific Method?

A hypothesis is a statement describing an expectation or prediction of your research through observation.

It is similar to academic speculation and reasoning that discloses the outcome of your scientific test . An effective hypothesis, therefore, should be crafted carefully and with precision.

A good hypothesis should have dependent and independent variables . These variables are the elements you will test in your research method – it can be a concept, an event, or an object as long as it is observable.

You can observe the dependent variables while the independent variables keep changing during the experiment.

In a nutshell, a hypothesis directs and organizes the research methods you will use, forming a large section of research paper writing.

Hypothesis vs. Theory

A hypothesis is a realistic expectation that researchers make before any investigation. It is formulated and tested to prove whether the statement is true. A theory, on the other hand, is a factual principle supported by evidence. Thus, a theory is more fact-backed compared to a hypothesis.

Another difference is that a hypothesis is presented as a single statement , while a theory can be an assortment of things . Hypotheses are based on future possibilities toward a specific projection, but the results are uncertain. Theories are verified with undisputable results because of proper substantiation.

When it comes to data, a hypothesis relies on limited information , while a theory is established on an extensive data set tested on various conditions.

You should observe the stated assumption to prove its accuracy.

Since hypotheses have observable variables, their outcome is usually based on a specific occurrence. Conversely, theories are grounded on a general principle involving multiple experiments and research tests.

This general principle can apply to many specific cases.

The primary purpose of formulating a hypothesis is to present a tentative prediction for researchers to explore further through tests and observations. Theories, in their turn, aim to explain plausible occurrences in the form of a scientific study.

It would help to rely on several criteria to establish a good hypothesis. Below are the parameters you should use to analyze the quality of your hypothesis.

| Testability | You should be able to test the hypothesis to present a true or false outcome after the investigation. Apart from the logical hypothesis, ensure you can test your predictions with . |

|---|---|

| Variables | It should have a dependent and independent variable. Identifying the appropriate variables will help readers comprehend your prediction and what to expect at the conclusion phase. |

| Cause and effect | A good hypothesis should have a cause-and-effect connection. One variable should influence others in some way. It should be written as an “if-then” statement to allow the researcher to make accurate predictions of the investigation results. However, this rule does not apply to a . |

| Clear language | Writing can get complex, especially when complex research terminology is involved. So, ensure your hypothesis has expressed as a brief statement. Avoid being vague because your readers might get confused. Your hypothesis has a direct impact on your entire research paper’s quality. Thus, use simple words that are easy to understand. |

| Ethics | Hypothesis generation should comply with . Don’t formulate hypotheses that contravene taboos or are questionable. Besides, your hypothesis should have correlations to published academic works to look data-based and authoritative. |

🧭 6 Steps to Making a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis becomes way simpler if you follow a tried-and-tested algorithm. Let’s explore how you can formulate a good hypothesis in a few steps:

Step #1: Ask Questions

The first step in hypothesis creation is asking real questions about the surrounding reality.

Why do things happen as they do? What are the causes of some occurrences?

Your curiosity will trigger great questions that you can use to formulate a stellar hypothesis. So, ensure you pick a research topic of interest to scrutinize the world’s phenomena, processes, and events.

Step #2: Do Initial Research

Carry out preliminary research and gather essential background information about your topic of choice.

The extent of the information you collect will depend on what you want to prove.

Your initial research can be complete with a few academic books or a simple Internet search for quick answers with relevant statistics.

Still, keep in mind that in this phase, it is too early to prove or disapprove of your hypothesis.

Step #3: Identify Your Variables

Now that you have a basic understanding of the topic, choose the dependent and independent variables.

Take note that independent variables are the ones you can’t control, so understand the limitations of your test before settling on a final hypothesis.

Step #4: Formulate Your Hypothesis

You can write your hypothesis as an ‘if – then’ expression . Presenting any hypothesis in this format is reliable since it describes the cause-and-effect you want to test.

For instance: If I study every day, then I will get good grades.

Step #5: Gather Relevant Data

Once you have identified your variables and formulated the hypothesis, you can start the experiment. Remember, the conclusion you make will be a proof or rebuttal of your initial assumption.

So, gather relevant information, whether for a simple or statistical hypothesis, because you need to back your statement.

Step #6: Record Your Findings

Finally, write down your conclusions in a research paper .

Outline in detail whether the test has proved or disproved your hypothesis.

Edit and proofread your work, using a plagiarism checker to ensure the authenticity of your text.

We hope that the above tips will be useful for you. Note that if you need to conduct business analysis, you can use the free templates we’ve prepared: SWOT , PESTLE , VRIO , SOAR , and Porter’s 5 Forces .

❓ Hypothesis Formulator FAQ

Updated: Oct 25th, 2023

- How to Write a Hypothesis in 6 Steps - Grammarly

- Forming a Good Hypothesis for Scientific Research

- The Hypothesis in Science Writing

- Scientific Method: Step 3: HYPOTHESIS - Subject Guides

- Hypothesis Template & Examples - Video & Lesson Transcript

- Free Essays

- Writing Tools

- Lit. Guides

- Donate a Paper

- Referencing Guides

- Free Textbooks

- Tongue Twisters

- Job Openings

- Video Contest

- Writing Scholarship

- Discount Codes

- Brand Guidelines

- IvyPanda Shop

- Online Courses

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Copyright Principles

- DMCA Request

- Service Notice

Use our hypothesis maker whenever you need to formulate a hypothesis for your study. We offer a very simple tool where you just need to provide basic info about your variables, subjects, and predicted outcomes. The rest is on us. Get a perfect hypothesis in no time!

The best AI tools for research papers and academic research (Literature review, grants, PDFs and more)

As our collective understanding and application of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to evolve, so too does the realm of academic research. Some people are scared by it while others are openly embracing the change.

Make no mistake, AI is here to stay!

Instead of tirelessly scrolling through hundreds of PDFs, a powerful AI tool comes to your rescue, summarizing key information in your research papers. Instead of manually combing through citations and conducting literature reviews, an AI research assistant proficiently handles these tasks.

These aren’t futuristic dreams, but today’s reality. Welcome to the transformative world of AI-powered research tools!

This blog post will dive deeper into these tools, providing a detailed review of how AI is revolutionizing academic research. We’ll look at the tools that can make your literature review process less tedious, your search for relevant papers more precise, and your overall research process more efficient and fruitful.

I know that I wish these were around during my time in academia. It can be quite confronting when trying to work out what ones you should and shouldn’t use. A new one seems to be coming out every day!

Here is everything you need to know about AI for academic research and the ones I have personally trialed on my YouTube channel.

My Top AI Tools for Researchers and Academics – Tested and Reviewed!

There are many different tools now available on the market but there are only a handful that are specifically designed with researchers and academics as their primary user.

These are my recommendations that’ll cover almost everything that you’ll want to do:

| Find literature using semantic search. I use this almost every day to answer a question that pops into my head. | |

| An increasingly powerful and useful application, especially effective for conducting literature reviews through its advanced semantic search capabilities. | |

| An AI-powered search engine specifically designed for academic research, providing a range of innovative features that make it extremely valuable for academia, PhD candidates, and anyone interested in in-depth research on various topics. | |

| A tool designed to streamline the process of academic writing and journal submission, offering features that integrate directly with Microsoft Word as well as an online web document option. | |

| A tools that allow users to easily understand complex language in peer reviewed papers. The free tier is enough for nearly everyone. | |

| A versatile and powerful tool that acts like a personal data scientist, ideal for any research field. It simplifies data analysis and visualization, making complex tasks approachable and quick through its user-friendly interface. |

Want to find out all of the tools that you could use?

Here they are, below:

AI literature search and mapping – best AI tools for a literature review – elicit and more

Harnessing AI tools for literature reviews and mapping brings a new level of efficiency and precision to academic research. No longer do you have to spend hours looking in obscure research databases to find what you need!

AI-powered tools like Semantic Scholar and elicit.org use sophisticated search engines to quickly identify relevant papers.

They can mine key information from countless PDFs, drastically reducing research time. You can even search with semantic questions, rather than having to deal with key words etc.

With AI as your research assistant, you can navigate the vast sea of scientific research with ease, uncovering citations and focusing on academic writing. It’s a revolutionary way to take on literature reviews.

- Elicit – https://elicit.org

- Litmaps – https://www.litmaps.com

- Research rabbit – https://www.researchrabbit.ai/

- Connected Papers – https://www.connectedpapers.com/

- Supersymmetry.ai: https://www.supersymmetry.ai

- Semantic Scholar: https://www.semanticscholar.org

- Laser AI – https://laser.ai/

- Inciteful – https://inciteful.xyz/

- Scite – https://scite.ai/

- System – https://www.system.com

If you like AI tools you may want to check out this article:

- How to get ChatGPT to write an essay [The prompts you need]

AI-powered research tools and AI for academic research

AI research tools, like Concensus, offer immense benefits in scientific research. Here are the general AI-powered tools for academic research.

These AI-powered tools can efficiently summarize PDFs, extract key information, and perform AI-powered searches, and much more. Some are even working towards adding your own data base of files to ask questions from.

Tools like scite even analyze citations in depth, while AI models like ChatGPT elicit new perspectives.

The result? The research process, previously a grueling endeavor, becomes significantly streamlined, offering you time for deeper exploration and understanding. Say goodbye to traditional struggles, and hello to your new AI research assistant!

- Consensus – https://consensus.app/

- Iris AI – https://iris.ai/

- Research Buddy – https://researchbuddy.app/

- Mirror Think – https://mirrorthink.ai

AI for reading peer-reviewed papers easily

Using AI tools like Explain paper and Humata can significantly enhance your engagement with peer-reviewed papers. I always used to skip over the details of the papers because I had reached saturation point with the information coming in.

These AI-powered research tools provide succinct summaries, saving you from sifting through extensive PDFs – no more boring nights trying to figure out which papers are the most important ones for you to read!

They not only facilitate efficient literature reviews by presenting key information, but also find overlooked insights.

With AI, deciphering complex citations and accelerating research has never been easier.

- Aetherbrain – https://aetherbrain.ai

- Explain Paper – https://www.explainpaper.com

- Chat PDF – https://www.chatpdf.com

- Humata – https://www.humata.ai/

- Lateral AI – https://www.lateral.io/

- Paper Brain – https://www.paperbrain.study/

- Scholarcy – https://www.scholarcy.com/

- SciSpace Copilot – https://typeset.io/

- Unriddle – https://www.unriddle.ai/

- Sharly.ai – https://www.sharly.ai/

- Open Read – https://www.openread.academy

AI for scientific writing and research papers

In the ever-evolving realm of academic research, AI tools are increasingly taking center stage.

Enter Paper Wizard, Jenny.AI, and Wisio – these groundbreaking platforms are set to revolutionize the way we approach scientific writing.

Together, these AI tools are pioneering a new era of efficient, streamlined scientific writing.

- Jenny.AI – https://jenni.ai/ (20% off with code ANDY20)

- Yomu – https://www.yomu.ai

- Wisio – https://www.wisio.app

AI academic editing tools

In the realm of scientific writing and editing, artificial intelligence (AI) tools are making a world of difference, offering precision and efficiency like never before. Consider tools such as Paper Pal, Writefull, and Trinka.

Together, these tools usher in a new era of scientific writing, where AI is your dedicated partner in the quest for impeccable composition.

- PaperPal – https://paperpal.com/

- Writefull – https://www.writefull.com/

- Trinka – https://www.trinka.ai/

AI tools for grant writing

In the challenging realm of science grant writing, two innovative AI tools are making waves: Granted AI and Grantable.

These platforms are game-changers, leveraging the power of artificial intelligence to streamline and enhance the grant application process.

Granted AI, an intelligent tool, uses AI algorithms to simplify the process of finding, applying, and managing grants. Meanwhile, Grantable offers a platform that automates and organizes grant application processes, making it easier than ever to secure funding.

Together, these tools are transforming the way we approach grant writing, using the power of AI to turn a complex, often arduous task into a more manageable, efficient, and successful endeavor.

- Granted AI – https://grantedai.com/

- Grantable – https://grantable.co/

Best free AI research tools

There are many different tools online that are emerging for researchers to be able to streamline their research processes. There’s no need for convience to come at a massive cost and break the bank.

The best free ones at time of writing are:

- Elicit – https://elicit.org

- Connected Papers – https://www.connectedpapers.com/

- Litmaps – https://www.litmaps.com ( 10% off Pro subscription using the code “STAPLETON” )

- Consensus – https://consensus.app/

Wrapping up

The integration of artificial intelligence in the world of academic research is nothing short of revolutionary.

With the array of AI tools we’ve explored today – from research and mapping, literature review, peer-reviewed papers reading, scientific writing, to academic editing and grant writing – the landscape of research is significantly transformed.

The advantages that AI-powered research tools bring to the table – efficiency, precision, time saving, and a more streamlined process – cannot be overstated.

These AI research tools aren’t just about convenience; they are transforming the way we conduct and comprehend research.

They liberate researchers from the clutches of tedium and overwhelm, allowing for more space for deep exploration, innovative thinking, and in-depth comprehension.

Whether you’re an experienced academic researcher or a student just starting out, these tools provide indispensable aid in your research journey.

And with a suite of free AI tools also available, there is no reason to not explore and embrace this AI revolution in academic research.

We are on the precipice of a new era of academic research, one where AI and human ingenuity work in tandem for richer, more profound scientific exploration. The future of research is here, and it is smart, efficient, and AI-powered.

Before we get too excited however, let us remember that AI tools are meant to be our assistants, not our masters. As we engage with these advanced technologies, let’s not lose sight of the human intellect, intuition, and imagination that form the heart of all meaningful research. Happy researching!

Thank you to Ivan Aguilar – Ph.D. Student at SFU (Simon Fraser University), for starting this list for me!

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

🔬 AI Research Generators

Boost your research capabilities with AI research generators. Utilize AI-powered solutions designed for research use cases. Enhance analysis, gain insights, and foster innovation through cutting-edge AI technology.

AI Data Collection Plan Generator

Unleash the true power of your data! Our Data Collection Plan generator organizes and streamlines your data collection process, saving you time and energy, while elevating the quality of your decision-making. One click, and you’re on your way to a hassle-free data journey!

AI Literature Review Generator

Unleash the power of AI with our Literature Review Generator. Effortlessly access comprehensive and meticulously curated literature reviews to elevate your research like never before!

AI Research Proposal Generator

Seize the opportunity to revolutionize AI research with our AI Research Proposal Generator. Craft compelling and comprehensive proposals that will secure funding and set your project on the path to success.

AI Thesis Statement Generator

Master the art of crafting a powerful AI thesis with our AI Thesis Statement Generator. Unleash the potential of AI to generate concise and compelling statements that lay the foundation for exceptional academic work.

AI Bibliography Generator

Elevate your AI research with ease using our AI Bibliography Generator. Effortlessly create accurate and perfectly formatted bibliographies, leaving more time for groundbreaking discoveries.

AI Research Grant Proposal Generator

Unlock funding for your AI research dreams with our AI Research Grant Proposal Generator. Craft compelling grant proposals that captivate reviewers and secure the support your project deserves.

AI Research Timeline Generator

Chart your course to AI research success with our AI Research Timeline Generator. Seamlessly create well-structured timelines that keep your research on track and ensure timely achievements.

AI Quantitative Data Analysis Plan Generator

Unlock the potential of your quantitative data with our AI Quantitative Data Analysis Plan Generator. Effortlessly design data analysis strategies that reveal the true insights hidden within your research.

AI Research Presentation Generator

Captivate your audience and showcase your AI research brilliance with our AI Research Presentation Generator. Elevate your presentations to new heights, leaving a lasting impact on every viewer.

AI Fieldwork Plan Generator

Elevate your research with our cutting-edge Fieldwork Plan generator!

AI Research Collaboration Plan Generator

Unleash the potential of AI collaboration with our AI Research Collaboration Plan Generator. Seamlessly design strategic and fruitful partnerships to amplify the impact of your AI research.

AI Research Publication Plan Generator

Elevate your AI research dissemination with our AI Research Publication Plan Generator. Strategize and optimize your publication journey, ensuring your groundbreaking findings reach the widest audience.

AI Research Impact Assessment Generator

Unlock the true potential of your AI research with our revolutionary AI Research Impact Assessment Generator. Maximize your impact and soar above the competition!

AI Research Evaluation Plan Generator

Unlock the roadmap to AI research success with our AI Research Evaluation Plan Generator. Effortlessly design robust evaluation plans and pave the way for groundbreaking discoveries.

View All Generator Categories

AI Research Tools

Qonqur is an innovative software that allows you to control your computer and digital content using hand gestures, without the need for expensive virtual reality

Ai Summary Generator

Ai Summary Generator is a text summarization tool that can instantly summarize lengthy texts or turn them into bullet point lists. It uses AI to

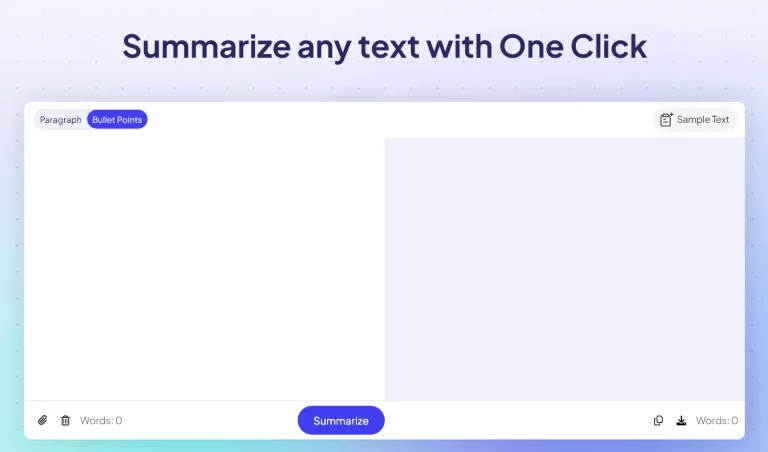

Glasp is a free Chrome and Safari extension that lets you easily highlight and annotate text on websites and PDFs. Its key features include syncing

SciSpace is an AI research assistant that simplifies researching papers through AI-generated explanations and a network showing connections between relevant papers. It aims to automate

Genei is a research tool that automates the process of summarizing background reading and can also generate blogs, articles, and reports. It allows you to

Afforai is an AI research assistant designed to help researchers collect, organize, and analyze academic materials. Afforai allows you to upload papers, automatically extract metadata

Otio is an AI-powered research and writing assistant designed to help students, researchers, analysts and professionals alike. It can easily summarize your documents and web

ChatPDF allows you to talk to your PDF documents as if they were human. It’s perfect for quickly extracting information or answering questions from large

Lumina Chat

Lumina Chat is an AI-powered search engine that lets you instantly get detailed answers from over 1 million journal articles and research papers. It allows

WhiteBridge.ai

WhiteBridge is an AI-powered research platform that consolidates data from over 100 public sources to provide you with comprehensive background information on individuals. You can

HyperWrite is an AI-powered writing assistant that helps you create high-quality content quickly and easily. It can also provide personalized suggestions as you write to

scite is an AI-powered research tool that helps researchers discover and evaluate scientific articles. It analyzes millions of citations and shows how each article has

Discover the latest AI research tools to accelerate your studies and academic research. Search through millions of research papers, summarize articles, view citations, and more.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Copyright © 2024 EasyWithAI.com

Top AI Tools

- Best Free AI Image Generators

- Best AI Video Editors

- Best AI Meeting Assistants

- Best AI Tools for Students

- Top 5 Free AI Text Generators

- Top 5 AI Image Upscalers

Readers like you help support Easy With AI. When you make a purchase using links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the latest AI tools !

We don’t spam! Read our privacy policy for more info.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Please check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription. Thank you!

Free Research Title Generator

Looking for a creative and catchy title for a research proposal, thesis, dissertation, essay, or other project? Try our research title maker! It is free, easy to use, and 100% online.

Welcome to our free online research title generator. You can get your title in 3 simple steps:

- Type your search term and choose one or more subjects from the list,

- Click on the “Search topic” button and choose among the ideas that the title generator has proposed,

- Refresh the list by clicking the button one more time if you need more options.

Please try again with some different keywords or subjects.

- ️✅ Research Title Generator: 4 Benefits

- ️👣 Making a Research Title in 3 Steps

- ️🔗 References

Creating a topic for the research is one of the most significant events in a researcher’s life. Whether it is a thesis, dissertation, research proposal , or term paper, all of these assignments are time-consuming and require a lot of effort.

It is essential to choose a topic that you like and are genuinely interested in because you will spend a lot of time working on it. Our research title generator can help you with this crucial task. By delegating this work to our research title maker, you can find the best title for your research.

✅ Research Title Generator: 4 Benefits

There are many different research title makers online, so what makes our thesis title generator stand out?

| 🤑 It is 100% free | You don’t have to spend money. You can use our service absolutely for free. Make as many titles as you want for an unlimited number of assignments and pages. |

|---|---|

| 🌐 It is 100% online | No need to take any free space on your laptop! The Internet has changed our lives and made studying convenient. There are many different online tools and checkers that you can use to study, and we are no exception. |

| 🏆 It is 100% effective | You don’t need to worry about your research’s title anymore. Our thesis title generator can do all the work for you. You can refresh your research title list as many times as you want to find a title that suits your work the best. |

| 🌈 It is 100% intuitive | Our research title generator is easy-to-use and functional. Try it out to check it yourself! |

👣 How to Make a Research Title: 3 Simple Steps

Research can be the most stressful period in a student’s life. However, creating a title is not as hard as it may seem. You can choose a topic for your paper in three simple steps.

Step 1: Brainstorm

The first step to take before getting into your research is to brainstorm . To choose a good topic, you can do the following:

- Think of all your interests related to your field of study. What is the reason you've chosen this field? Think of the topics of your area that you like reading about in your free time.

- Go through your past papers and choose the ones you enjoyed writing. You can use some lingering issues from your previous work as a starting point for your research.

- Go through current events in your field to get an idea of what is going on. Whether you are writing a literary analysis , gender studies research, or any other kind of paper, you can always find tons of articles related to your field online. You can go through them to see what issue is getting more attention.

- Try to find any gaps in current researches in your field. Use only credible sources while searching. Try to add something new to your field with your research. However, do not choose a completely new issue.

- Discuss what topic is suitable for you with your professors. Professor knows a lot of information about current and previous researches, so try to discuss it with them.

- Discuss lingering issues with your classmates. Try to ask what questions do they have about your field.

- Think of your desired future work . Your research might serve as a starting point for your future career, so think of your desired job.

- Write down 5-10 topics that you might be interested in. Ph.D. or Master’s research should be specific, so write down all the appropriate topics that you came up with.

Step 2: Narrow It Down

As you are done brainstorming, you have a list of possible research topics. Now, it is time to narrow your list down.

Go through your list again and eliminate the topics that have already been well-researched before. Remember that you need to add something new to your field of study, so choose a topic that can contribute to it. However, try not to select a topic not researched at all, as it might be difficult.

Once you get a general idea of what your research will be about, choose a research supervisor. Think of a professor who is an expert in your desired area of research. Talk to them and tell them the reason why you want to work with them and why you chose this area of study.

As you eliminated some irrelevant topics and shortened your list to 1-3 topics, you can discuss them with your supervisor. Since your supervisor has a better insight into your field of study, they can recommend a topic that can be most suitable for you. Make sure to elaborate on each topic and the reason you chose it.

Step 3: Formulate a Research Question

The next step is to create a research question. This is probably the most important part of the process. Later you'll turn your research question into a thesis statement .

Learn as many materials as you can to figure out the type of questions you can ask for your research. Make use of any articles, journals, libraries, etc. Write notes as you learn, and highlight the essential parts.

First, make any questions you can think of. Choose the ones that you have an interest in and try to rewrite them. As you rewrite them, you can get a different perspective on each of the questions. An example of the potential question:

How did the economic situation in the 19th century affect literature?

Think of a question that you can answer and research best. To do it, think of the most convenient research process and available materials that you have access to. Do you need to do lab testing, quantitative analysis, or any kind of experiment? What skills do you have that can be useful?

Discuss the question that you came up with your supervisor. Get their feedback as they might have their own opinion on that topic and give you creative advice.

❓ Research Title Maker FAQ

❓ how to make a research title.

To make a research title:

- Brainstorm your field of study first.

- Think of the topics that you are interested in.

- Research current events in your study area and discuss your possible topics with your professors and classmates.

- Avoid random topics that are not well-researched.

❓ What is a working title for a research paper?

To make a good research paper title, analyze your area of study and all the related current events. Discuss your possible topics with your classmates and professors to get their opinion on them. You can also use our research title maker for free.

❓ What is the title page of a research paper?

The title page of the research paper is the first paper of your work. It includes your name, research type, and other essential information about your research.

❓ How to title a research proposal?

The research proposal title should be clear enough to showcase your research. Think of a statement that best describes your work and try to create a title that reflects it.

Updated: Jun 5th, 2024

🔗 References

- Research Topics | Frontiers

- Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Strategies for Selecting a Research Topic - ResearchGate

- The First Steps: Choosing a Topic and a Thesis Supervisor

- How to Pick a Masters Thesis Topic | by Peter Campbell

Research Hypothesis Generator

Generate research hypotheses with ai.

- Academic Research: Formulate a hypothesis for your thesis or dissertation based on your research topic and objectives.

- Data Analysis: Generate a hypothesis to guide your data collection and analysis strategy.

- Market Research: Develop a hypothesis to guide your investigation into market trends and consumer behavior.

- Scientific Research: Create a hypothesis to direct your experimental design and data interpretation.

New & Trending Tools

Text corrector and formatter, strategic planning and decision-making in healthcare tutor, healthcare organizational structures and governance tutor.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

| and describe frequencies, averages, and correlations about relationships between variables |

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed-methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships

- Descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | relationships effect on a |

| Quasi-experimental | ) |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analyzing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study—plants, animals, organizations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

- Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalize your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study , your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalize to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question .

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviors, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews .

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

| ) |

Observation methods

Observational studies allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviors or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what kinds of data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected—for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are high in reliability and validity.

Operationalization

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalization means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in—for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity