- (855) 776-7763

Training Maker

All Products

Qualaroo Insights

ProProfs.com

- Sign Up Free

Do you want a free Survey Software?

We have the #1 Online Survey Maker Software to get actionable user insights.

How To Write a Good Research Question: Guide with Definition, Tips & Examples

Sameer Bhatia

Founder and CEO - ProProfs

Review Board Member

Sameer Bhatia is the Founder and Chief Executive Officer of ProProfs.com. He believes that software should make you happy and is driven to create a 100-year company that delivers delightfully ... Read more

Sameer Bhatia is the Founder and Chief Executive Officer of ProProfs.com. He believes that software should make you happy and is driven to create a 100-year company that delivers delightfully smart software with awesome support. His favorite word is 'delight,' and he dislikes the term 'customer satisfaction,' as he believes that 'satisfaction' is a low bar and users must get nothing less than a delightful experience at ProProfs. Sameer holds a Masters in Computer Science from the University of Southern California (USC). He lives in Santa Monica with his wife & two daughters. Read less

Market Research Specialist

Emma David, a seasoned market research professional, specializes in employee engagement, survey administration, and data management. Her expertise in leveraging data for informed decisions has positively impacted several brands, enhancing their market position.

Research questions form the backbone of any study, guiding researchers in their search for knowledge and understanding. Framing relevant research questions is the first essential step for ensuring the research is effective and produces valuable insights.

In this blog, we’ll explore what research questions are, tips for crafting them, and a variety of research question examples across different fields to help you formulate a well-balanced research questionnaire.

Let’s begin.

What Is a Research Question?

A research question is a specific inquiry or problem statement guiding a research study, outlining the researcher’s intention to investigate. Think of it as a roadmap for your paper or thesis – it tells you exactly what you want to explore, giving your work a clear purpose.

A good research question not only helps you focus your writing but also guides your readers. It gives them a clear idea of what your research is about and what you aim to achieve. Before you start drafting your paper and even before you conduct your study, it’s important to write a concise statement of what you want to accomplish or discover.

This sets the stage for your research and ensures your work is focused and purposeful.

Why Are Research Questions Important?

Research questions are the cornerstone of any academic or scientific inquiry. They serve as a guide for the research process, helping to focus the study, define its goals, and structure its methodology.

Below are some of its most significant impacts, along with hypothetical examples to help you understand them better:

1. Guidance and Focus

Research questions provide a clear direction for the study, enabling researchers to narrow down the scope of their investigation to a manageable size. Research efforts can become scattered and unfocused without a well-defined question without a well-defined question, leading to wasted time and resources.

For example, consider a researcher interested in studying the effects of technology on education. A broad interest in technology and education could lead to an overwhelming range of topics to cover. However, by formulating a specific research question such as, “ How does the use of interactive digital textbooks in high school science classes affect students’ learning outcomes?” the researcher can focus their study on a specific aspect of technology in education, making the research more manageable and directed.

2. Defining the Research Objectives

A well-crafted research question helps to clearly define what the researcher aims to discover, examine, or analyze. This clarity is crucial for determining the study’s objectives and ensures that every step of the research process contributes toward achieving these goals.

For example, in a study aimed at understanding the impact of remote work on employee productivity, a research question such as “ Does remote work increase productivity among information technology professionals? ” directly sets the objective of the study to measure productivity levels among a specific group when working remotely.

3. Determining the Research Methodology

The research question influences the choice of methodology, including the design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. It dictates whether the study should be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods and guides the selection of tools and procedures for conducting the research.

For example, in a research question like “ What are the lived experiences of first-generation college students? ” a qualitative approach using interviews or focus groups might be chosen to gather deep, nuanced insights into students’ experiences. In contrast, a question such as “ What percentage of first-generation college students graduate within four years?” would require a quantitative approach, possibly utilizing existing educational data sets for analysis.

4. Enhancing Relevance and Contribution

A well-thought-out research question ensures that the study addresses a gap in the existing literature or solves a real-world problem. This relevance is crucial for the contribution of the research to the field, as it helps to advance knowledge, inform policy, or offer practical solutions.

For example, in a scenario where existing research has largely overlooked the environmental impacts of single-use plastics in urban waterways, a question like “ What are the effects of single-use plastic pollution on the biodiversity of urban waterways?” can fill this gap, contributing valuable new insights to environmental science and potentially influencing urban environmental policies.

5. Facilitating Data Interpretation and Analysis

Clear research questions help in structuring the analysis, guiding the interpretation of data, and framing the discussion of results. They ensure that the data collected is directly relevant to the questions posed, making it easier to draw meaningful conclusions.

For example, in a study asking, “ How do social media algorithms influence political polarization among users? ” the data analysis would specifically focus on the mechanisms of algorithmic content delivery and its effects on user behavior and political views. This focus makes it straightforward to interpret how algorithm-induced echo chambers might contribute to polarization.

Types of Research Questions

Understanding the different types of research questions is essential for researchers to effectively design and conduct studies that align with their research objectives and methodologies

These questions can be broadly categorized into three main types: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method research questions.

Let’s explore each type in-depth, along with some examples.

Type A: Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to answer specific research questions or hypotheses. It focuses on quantifying relationships, patterns, and phenomena, often using statistical methods for analysis. Quantitative research questions are typically structured and aim to explore relationships between variables or assess the impact of interventions.

Quantitative research questions can again be subcategorized into three distinct types:

1. Descriptive Questions :

Descriptive questions aim to describe characteristics, behaviors, or phenomena within a population. These questions often start with words like “ how much ,” “ how many ,” or “ what is the frequency of .” They provide a snapshot of a particular situation or phenomenon.

Example: “ What is the average age of first-time homebuyers in the United States?”

2. Comparative Questions :

Comparative questions seek to compare two or more groups, conditions, or variables to identify differences or similarities. They often involve the use of statistical tests to determine the significance of observed differences or associations.

Example: “Is there a significant difference in academic performance between students who receive tutoring and those who do not?”

3. Relationship Questions:

Relationship questions explore the associations or correlations between variables. They aim to determine the strength and direction of relationships, allowing researchers to assess the predictive power of one variable on another.

Example: “What is the relationship between exercise frequency and levels of anxiety among adults?”

Type B: Qualitative Research Questions

Qualitative research involves the exploring and understanding of complex phenomena through an in-depth examination of individuals’ experiences, behaviors, and perspectives. It aims to uncover meaning, patterns, and underlying processes within a specific context, often through techniques such as interviews, observations, and content analysis.

Types of qualitative research questions:

1. Exploratory Questions:

Exploratory questions seek to understand a particular phenomenon or issue in depth. They aim to uncover new insights, perspectives, or dimensions that may not have been previously considered.

Example: “What are the experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in accessing healthcare services in rural communities?”

2. Descriptive Questions:

Descriptive questions aim to provide a detailed description or portrayal of a phenomenon or social context. They focus on capturing the intricacies and nuances of a particular situation or setting.

Example: “What are the communication patterns within multicultural teams in a corporate setting?”

3. Explanatory Questions:

Explanatory questions delve into the underlying reasons, mechanisms, or processes that influence a phenomenon or behavior. They aim to uncover the ‘why’ behind observed patterns or relationships.

Example: “What factors contribute to employee turnover in the hospitality industry?”

Type C: Mixed-Methods Research Questions

Mixed-methods research integrates both quantitative and qualitative approaches within a single study, allowing researchers to gain a comprehensive understanding of a research problem. Mixed-method research questions are designed to address complex phenomena from multiple perspectives, combining the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

Types of Mixed-Methods Research Questions:

1. Sequential Questions:

Sequential questions involve the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data in separate phases or stages. The findings from one phase inform the design and implementation of the subsequent phase.

Example: “Quantitatively, what are the prevalence rates of mental health disorders among adolescents? Qualitatively, what are the factors influencing help-seeking behaviors among adolescents with mental health concerns?”

2. Concurrent Questions:

Concurrent questions involve the simultaneous collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. Researchers triangulate findings from both methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

Example: “How do students’ academic performance (quantitative) correlate with their perceptions of school climate (qualitative)?”

3. Transformative Questions:

Transformative questions aim to use mixed-methods research to bring about social change or inform policy decisions. They seek to address complex societal issues by combining quantitative data on prevalence rates or trends with qualitative insights into lived experiences and perspectives.

Example: “What are the barriers to accessing healthcare services for underserved communities, and how can healthcare policies be redesigned to address these barriers effectively?”

Steps to Developing a Good Research Question

Developing a good research question is a crucial first step in any research endeavor. A well-crafted research question serves as the foundation for the entire study, guiding the researcher in formulating hypotheses, selecting appropriate methodologies, and conducting meaningful analyses.

Here are the steps to developing a good research question:

Identify a Broad Topic

Begin by identifying a broad area of interest or a topic that you would like to explore. This could stem from your academic discipline, professional interests, or personal curiosity. However, make sure to choose a topic that is both relevant and feasible for research within the constraints of your resources and expertise.

Conduct Preliminary Research

Before refining your research question, conduct preliminary research to familiarize yourself with existing literature and identify gaps, controversies, or unanswered questions within your chosen topic. This step will help you narrow down your focus and ensure that your research question contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

Narrow Down Your Focus

Based on your preliminary research, narrow down your focus to a specific aspect, problem, or issue within your chosen topic. Consider the scope of your study, the availability of resources, and the feasibility of addressing your research question within a reasonable timeframe. Narrowing down your focus will help you formulate a more precise and manageable research question.

Define Key Concepts and Variables

Clearly define the key concepts, variables, or constructs that are central to your research question. This includes identifying the main variables you will be investigating, as well as any relevant theoretical or conceptual frameworks that will guide your study. Clarifying these aspects will ensure that your research question is clear, specific, and focused.

Formulate Your Research Question

Based on your narrowed focus and defined key concepts, formulate your research question. A good research question is concise, specific, and clearly articulated. It should be phrased in a way that is open-ended and leads to further inquiry. Avoid vague or overly broad questions that are difficult to answer or lack clarity.

Consider the Type of Research

Consider whether your research question is best suited for quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research. The type of research question will influence your choice of methodologies, data collection techniques, and analytical approaches. Tailor your research question to align with the goals and requirements of your chosen research paradigm.

Evaluate the Significance and Relevance

Evaluate the significance and relevance of your research question within the context of your academic discipline, field of study, or practical implications. Consider how your research question fills gaps in knowledge, addresses practical problems, or advances theoretical understanding. A good research question should be meaningful and contribute to the broader scholarly conversation.

Refine and Revise

Finally, refine and revise your research question based on feedback from colleagues, advisors, or peers. Consider whether the question is clear, feasible, and likely to yield meaningful results. Be open to making revisions as needed to ensure that your research question is well-constructed and aligned with the goals of your study.

Examples of Research Questions

Below are some example research questions from various fields to provide a glimpse into the diverse array of inquiries within each field.

1. Psychology Research Questions:

- How does childhood trauma influence the development of personality disorders in adulthood?

- What are the effects of mindfulness meditation on reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression?

- How does social media usage impact self-esteem among adolescents?

- What factors contribute to the formation and maintenance of romantic relationships in young adults?

- What are the cognitive mechanisms underlying decision-making processes in individuals with addiction?

- How does parenting style affect the development of resilience in children?

- What are the long-term effects of early childhood attachment patterns on adult romantic relationships?

- What role does genetics play in the predisposition to mental health disorders such as schizophrenia?

- How does exposure to violent media influence aggressive behavior in children?

- What are the psychological effects of social isolation on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic?

2. Business Research Questions:

- What are the key factors influencing consumer purchasing behavior in the e-commerce industry?

- How does organizational culture impact employee job satisfaction and retention?

- What are the strategies for successful international market entry for small businesses?

- What are the effects of corporate social responsibility initiatives on brand reputation and consumer loyalty?

- How do leadership styles influence organizational innovation and performance?

- What are the challenges and opportunities for implementing sustainable business practices in emerging markets?

- What factors contribute to the success of startups in the technology sector?

- How do economic fluctuations affect consumer confidence and spending behavior?

- What are the impacts of globalization on supply chain management practices?

- What are the determinants of successful mergers and acquisitions in the corporate sector?

3. Education Research Questions:

- What teaching strategies are most effective for promoting student engagement in online learning environments?

- How does socioeconomic status impact academic achievement and educational attainment?

- What are the barriers to inclusive education for students with disabilities?

- What factors influence teacher job satisfaction and retention in urban schools?

- How does parental involvement affect student academic performance and school outcomes?

- What are the effects of early childhood education programs on later academic success?

- How do culturally responsive teaching practices impact student learning outcomes in diverse classrooms?

- What are the best practices for implementing technology integration in K-12 education?

- How do school leadership practices influence school climate and student outcomes?

- What interventions are most effective for addressing the achievement gap in STEM education?

4. Healthcare Research Questions:

- What are the factors influencing healthcare-seeking behavior among underserved populations?

- How does patient-provider communication affect patient satisfaction and treatment adherence?

- What are the barriers to implementing telemedicine services in rural communities?

- What interventions are effective for reducing hospital readmissions among elderly patients?

- How does access to healthcare services impact health disparities among marginalized communities?

- What are the effects of nurse staffing levels on patient outcomes in acute care settings?

- How do socioeconomic factors influence access to mental healthcare services?

- What are the best practices for managing chronic disease patients in primary care settings?

- What are the impacts of healthcare reform policies on healthcare delivery and patient outcomes?

- How does cultural competence training for healthcare providers affect patient trust and satisfaction?

5. Computer Science Research Questions:

- What are the security vulnerabilities of blockchain technology, and how can they be mitigated?

- How can machine learning algorithms be used to detect and prevent cyber-attacks?

- What are the privacy implications of data mining techniques in social media platforms?

- How can artificial intelligence be used to improve medical diagnosis and treatment?

- What are the challenges and opportunities for implementing edge computing in IoT systems?

- How can natural language processing techniques be applied to improve human-computer interaction?

- What are the impacts of algorithmic bias on fairness and equity in decision-making systems?

- How can quantum computing algorithms be optimized for solving complex computational problems?

- What are the ethical considerations surrounding the use of autonomous vehicles in transportation systems?

- How does the design of user interfaces influence user experience and usability in mobile applications?

Create a Compelling Research Question With the Given Examples

Understanding research questions is essential for any successful research endeavor. We’ve explored the various research questions – quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods – each with unique characteristics and purposes.

Through various examples, tips, and strategies, we’ve seen how research questions can be tailored to specific fields of study.

By following these guidelines, we are confident that your research questions will be well-designed, focused, and capable of yielding valuable insights.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some good research question examples.

Good research questions are clear, specific, relevant, and feasible. For example, “How does childhood trauma influence the development of personality disorders in adulthood?”

What are some examples of good and bad research questions?

Good research questions are focused and relevant, such as “What factors influence employee job satisfaction in the hospitality industry?” Bad research questions are vague or trivial, like “What is the favorite color of employees in the hospitality industry?”

Watch: How to Create a Survey Using ProProfs Survey Maker

About the author

Emma David is a seasoned market research professional with 8+ years of experience. Having kick-started her journey in research, she has developed rich expertise in employee engagement, survey creation and administration, and data management. Emma believes in the power of data to shape business performance positively. She continues to help brands and businesses make strategic decisions and improve their market standing through her understanding of research methodologies.

Popular Posts in This Category

11 SoGoSurvey Alternatives & Competitors in 2024

10 Best Form Builder Software to Simplify Data Collection

Cluster Sampling: Definition, Methods & Applications

What Is a Customer Satisfaction Score and How to Measure It

20 Strategies to Improve Customer Satisfaction

8 Best Cognito Forms Alternatives in 2024

Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Think Like a Researcher: Instruction Resources: #6 Developing Successful Research Questions

- Guide Organization

- Overall Summary

- #1 Think Like a Researcher!

- #2 How to Read a Scholarly Article

- #3 Reading for Keywords (CREDO)

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research (Alternate)

- #5 Integrating Sources

- Research Question Discussion

- #7 Avoiding Researcher Bias

- #8 Understanding the Information Cycle

- #9 Exploring Databases

- #10 Library Session

- #11 Post Library Session Activities

- Summary - Readings

- Summary - Research Journal Prompts

- Summary - Key Assignments

- Jigsaw Readings

- Permission Form

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence

Goal: Develop students’ ability to recognize and create successful research questions

Specifically, students will be able to

- identify the components of a successful research question.

- create a viable research question.

What Makes a Good Research Topic Handout

These handouts are intended to be used as a discussion generator that will help students develop a solid research topic or question. Many students start with topics that are poorly articulated, too broad, unarguable, or are socially insignificant. Each of these problems may result in a topic that is virtually un-researchable. Starting with a researchable topic is critical to writing an effective paper.

Research shows that students are much more invested in writing when they are able to choose their own topics. However, there is also research to support the notion that students are completely overwhelmed and frustrated when they are given complete freedom to write about whatever they choose. Providing some structure or topic themes that allow students to make bounded choices may be a way mitigate these competing realities.

These handouts can be modified or edited for your purposes. One can be used as a handout for students while the other can serve as a sample answer key. The document is best used as part of a process. For instance, perhaps starting with discussing the issues and potential research questions, moving on to problems and social significance but returning to proposals/solutions at a later date.

- Research Questions - Handout Key (2 pgs) This document is a condensed version of "What Makes a Good Research Topic". It serves as a key.

- Research Questions - Handout for Students (2 pgs) This document could be used with a class to discuss sample research questions (are they suitable?) and to have them start thinking about problems, social significance, and solutions for additional sample research questions.

- Research Question Discussion This tab includes materials for introduction students to research question criteria for a problem/solution essay.

Additional Resources

These documents have similarities to those above. They represent original documents and conversations about research questions from previous TRAIL trainings.

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? - Original Handout (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan. 2016 (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan 2016 with comments

Topic Selection (NCSU Libraries)

Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigues. " Writing from sources, writing from sentences ." Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177-192.

Research Journal

Assign after students have participated in the Developing Successful Research Topics/Questions Lesson OR have drafted a Research Proposal.

Think about your potential research question.

- What is the problem that underlies your question?

- Is the problem of social significance? Explain.

- Is your proposed solution to the problem feasible? Explain.

- Do you think there is evidence to support your solution?

Keys for Writers - Additional Resource

Keys for Writers (Raimes and Miller-Cochran) includes a section to guide students in the formation of an arguable claim (thesis). The authors advise students to avoid the following since they are not debatable.

- "a neutral statement, which gives no hint of the writer's position"

- "an announcement of the paper's broad subject"

- "a fact, which is not arguable"

- "a truism (statement that is obviously true)"

- "a personal or religious conviction that cannot be logically debated"

- "an opinion based only on your feelings"

- "a sweeping generalization" (Section 4C, pg. 52)

The book also provides examples and key points (pg. 53) for a good working thesis.

- << Previous: #5 Integrating Sources

- Next: Research Question Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/think_like_a_researcher

Influencers on YouTube: a quantitative study on young people’s use and perception of videos about political and societal topics

- Open access

- Published: 18 November 2020

- Volume 41 , pages 6808–6824, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Daniel Zimmermann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3311-4138 1 ,

- Christian Noll 2 ,

- Lars Gräßer 3 ,

- Kai-Uwe Hugger 2 ,

- Lea Marie Braun 2 ,

- Tine Nowak 2 &

- Kai Kaspar 1

41k Accesses

30 Citations

Explore all metrics

The roles of YouTube videos and YouTubers for getting information about political and societal topics are becoming gradually more important to young people. Quantitative research about young people’s use and perception of YouTube-videos and their potential effects on opinion formation is sparse though. This cross-sectional quantitative study addresses this empirical gap. We examined young people’s analytic-critical evaluations of YouTubers and their videos about political and societal topics (YTPS-videos), and how these are affected by the young people’s age and gender. We analysed questionnaire data of 562 participants and divided them into three different age groups. Overall, the participants reported a moderate watching frequency of YTPS-videos. They also rated YTPS-videos as moderately credible and considered specific characteristics of YTPS-videos and their producers as being moderately indicative for fake news. When comparing to traditional TV news, YTPS-videos were perceived as more entertaining, emotional, funny, exciting, modern, and motivating but also as more subjective and manipulating. Regarding YouTubers, the participants ascribed them an important role model function, but criticised them for handling it rather irresponsibly. Concerning opinion formation processes, the participants reported of a rather unimportant role of YTPS-videos for their learning about political and societal topics. They also perceived themselves as less influenceable than other peers and younger people. Still, they prefer talking with friends instead of teachers about YTPS-videos. Age and gender also had effects on various scales. These results deliver essential data for future research and educational measures and opened up unexplored areas in this research field.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Drivers of Video Popularity on YouTube: An Empirical Investigation

Exploring the community of older adult viewers on YouTube

Analysing YouTube Audience Reactions and Discussions: A Network Approach

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social media is an important information source for young people (Gangadharbatla, Bright, & Logan, 2014 ; Kaspar & Müller-Jensen, 2019 ), and YouTube seems to be especially relevant. Young people consume YouTube-videos to obtain new information and forming their own opinion (Schmidt, Hölig, Merten, & Hasebrink, 2017 ). In this context, the role of YouTube creators and their videos on political and societal topics become gradually more important (Lewis, 2020 ). However, research on how young people use and perceive such videos and how they perceive the potential effects of such videos on their opinion formation is sparse, primarily quantitative approaches. The present study aims to fill this empirical gap by exploring (1) how intensively young people watch YouTuber videos about political and societal topics (YTPS-videos), (2) how young people evaluate YouTube creators (YouTubers) and the content of their videos, (3) how young people perceive their influenceability by YTPS-videos, (4) with whom and via which channels they communicate about the content of YTPS-videos, and (5) how these aspects are affected by young people’s age and gender. Importantly, in the present study, YTPS-videos are not restricted to a specific format (e.g., commentary, interview, report) and cover any kind of news about political or societal events being of potential interest to the audience.

Intensity of YouTube Usage

In April 2020, YouTube had the second-highest number of active users worldwide after Facebook, making it the most popular and most important online video platform to date (Statista, 2020 ). Nearly two-thirds of 12- to 19-year-old German teenagers indicated YouTube as their favourite online platform in 2019 (MPFS, 2020 ), with 90% of them watched videos on YouTube regularly. Similar results were found in Britain (Jiménez, García, & de Ayala, 2016 ) and Israel (Zilka, 2018 ). Also, Zilka ( 2018 ) found significant gender and age effects regarding preferred media content. Consequently, and concerning the present study, the question arises how intensively young people watch YTPS-videos and how this is related to their general YouTube usage intensity, visiting frequency of YouTuber channels as well as gender and age:

How frequently do young people of different age and gender watch YouTube and how intensively do they watch YTPS-videos in particular?

Evaluation of YouTubers and YTPS-Videos

When it comes to the evaluation of YouTubers and the content of YTPS-videos, credibility is one central aspect. Beyond a positive relationship between the perception of media credibility and news consumption (Nelson & Kim, 2020 ), credibility affects the persuasiveness of media content. The Source Credibility Model (cf. Lowry, Wilson, & Haig, 2013 ) emphasises that the source of a message and its perceived expertise and trustworthiness are determinants of the message’s persuasiveness and perceived usefulness, as shown for various scenarios in the context of social media (e.g., Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017 ; Lou & Yuan, 2019 ). Besides, credibility was also found to be positively related to the general liking of YouTuber videos (Xiao, Wang, & Chan-Olmsted, 2018 ). Moreover, the evaluation of the credibility of online information depends on the recipient’s age. For example, college students perceived online information as more credible and verified them more rarely than older adults did (Metzger, Flanagin, & Zwarun, 2003 ). Hence, we examined the following research question concerning YTPS-videos:

How do young people of different age and gender evaluate YTPS-videos’ credibility, how much do they like these videos, and how are these variables correlated with watching frequency?

The Source Credibility Model stresses the importance of the message’s source for its persuasiveness. However, the ‘source’ can refer to both the video and the YouTuber who produces and promotes the video. The question arises which characteristics of YTPS-videos and YouTubers young people use when evaluating credibility aspects and when checking for fake news. This question is particularly important in the context of videos about political and societal topics. Some studies have already examined (non-)credibility in terms of fake news during periods of a political election. Grinberg, Joseph, Friedland, Swire-Thompson, and Lazer ( 2019 ) and Guess, Nagler, and Tucker ( 2019 ) examined the sharing of and exposure to fake news on Twitter and Facebook, respectively, during the 2016 United States presidential campaign. The authors found that mostly conservative, older people were most likely to be engaged in fake news sources.

When it comes to the detection of fake news on social media, previous research often examined characteristics of news content which might be indicative of fake news, such as linguistic- and visual-based content features of news (Shu, Sliva, Wang, Tang, & Liu, 2017 ). However, young people’s strategy to detect fake news is still unclear. A first qualitative study delivered some hints: Hugger et al. ( 2019 ) found that young people’s credibility evaluation of the content of YTPS-videos appears to be strongly interlinked with perceived authenticity of the YouTubers; the perceived authenticity seems to be promoted by perceived individuality and autonomy of the YouTuber but is compromised by an increasing professionality of editorial work and news presentation. The present study hence further explored the characteristics of YTPS-videos that young people use to assess the news’ validity:

Which characteristics of YTPS-videos do young people of different age and gender consider indicative of fake news?

Additionally, young people seem to use traditional TV news as a reference to evaluate the credibility and the news value of YTPS-videos. Hugger et al. ( 2019 ) found that in order to assess the credibility of YouTubers and YTPS-videos, young people at the age of 15 to 16 reported that they compare YouTube with traditional mass media such as TV news, which are perceived as more objective and reliable. The authors speculate that this result may indicate a relatively low ability of young adolescents to analyse and reflect media content critically. In contrast, young adults explicitly perceived the mixing of personal opinions and objective information in mass media more strongly, indicating a significant role of the user’s age on media criticism. Though, it is unclear how this result pattern is quantitatively represented:

How do young people of different age and gender evaluate YTPS-videos compared to traditional TV news?

Besides the video itself, its producer plays a vital role as an information source. Recent research supports this claim: Lou and Yuan ( 2019 ) found influencer’s trustworthiness, attractiveness, and similarity to their followers being factors that positively affect followers’ trust in the messages and postings. Xiao et al. ( 2018 ) found that the trustworthiness and the social influence of YouTubers affect the perceived information credibility on YouTube. Furthermore, Balaban and Mustățea ( 2019 ) showed that attractiveness, trustworthiness, expertise, and similarity are essential factors affecting the perceived information credibility, at least in Romania and Germany. The evaluation of these factors may be additionally moderated by the gender of both the media user and the influencer (Todd & Melancon, 2018 ).

Moreover, recent studies shifted their focus to the perceived role model function of influencers. To put it briefly, recipients tend to identify more with, feel more similar to, and trust influencers more than celebrities (Schouten, Janssen, & Verspaget, 2020 ). In a recent literature review, De Veirman, Hudders, and Nelson ( 2019 ) stressed the importance of influencers as relatable and approachable role models, as children are willing to build (parasocial) relationships and to identify with them, which in turn can lead to the adoption of the influencers’ behaviour and opinion. In contrast, Martínez and Olsson ( 2019 ) showed in their qualitative study that children are capable of critically reflecting upon YouTubers, regarding their celebrity status and commercialisation especially. Interestingly, the degree of reflexivity differed between children. Thus, children do not seem to be a homogenous group when it comes to critical perceptions of YouTubers. Moreover, young people and women tend to have more trust in other people on social media, as compared to older people and men, respectively (Warner-Søderholm et al., 2018 ). Consequently, with regard to young people’s capability of media criticism in the context of YTPS-videos, we asked the following question:

To what extent do young people of different age and gender perceive YouTubers as reliable and responsible role models?

Learning with and Perceived Influenceability by YTPS-Videos

According to the core idea of uses-and-gratification models, people use media to satisfy particular needs such as the need for information and they hence actively link need gratification to media choice. Kaspar and Müller-Jensen ( 2019 ) summarised that uses-and-gratification models “usually assume that media recipients have certain psychological and societal needs (and associated motives), eliciting specific expectations about how mass media can fulfil these needs and leading to corresponding behavioural patterns of media use in order to obtain the desired gratifications at the end” (p. 2). So, it can be assumed that users might watch YTPS-videos specifically for acquiring new information and expand content-specific knowledge. Several studies highlighted the use of YouTube for learning purposes concerning students’ academic learning (Moghavvemi, Sulaiman, Jaafar, & Kasem, 2018 ), teenagers’ knowledge and skill acquisition (Pires, Masanet, & Scolari, 2019 ), and as an informal learning tool for children (Dyosi & Hattingh, 2018 ). Use motives also seem to differ between genders, with men showing more information-seeking intentions when using social networks than women (Krasnova, Veltri, Eling, & Buxmann, 2017 ). Accordingly, we examined the following research question:

How important do young people of different age and gender perceive YTPS-videos for knowledge acquisition about politics and societal topics?

In addition to the purposeful and intentional use of YouTube for knowledge acquisition (RQ3a), it is unclear as yet how young people assess the general potential of YTPS-videos to (unintentionally) influence their opinion formation. In recent years, a similar realm of this process was frequently examined under the terms of dispositional and situational advertising literacy in the field of marketing (Hudders, Cauberghe, & Panic, 2016 ): The ability to critically reflect upon advertising depends on the recipients’ coping skills. These skills thereby include recognising, analysing, and evaluating persuasion attempts as well as choosing an effective coping strategy against them. Interestingly, media literacy seems to improve with age (De Jans, Hudders, & Cauberghe, 2018 ), because older children (ten to eleven years) are better in detecting commercial attempts and brand placements than younger children (seven to eight years) (Hudders & Cauberghe, 2018 ). Besides, eight- to twelve-year-old children did not show the same level of media literacy as 18- to 30-year-old adults (Rozendaal, Buijzen, & Valkenburg, 2010 ). In contrast, results of previous studies show that even older adolescents show engagement in the activities of influencers instead of critically reflecting upon them (van Dam & van Reijmersdal, 2019 ). However, they perceive themselves as capable of understanding advertising and being somewhat resistant to it (De Jans et al., 2018 ).

Furthermore, psychological research in several domains revealed that one’s influenceability by mass media is often perceived as less pronounced than the influenceability of other peers. This phenomenon has been labelled the third-person effect in communication (Davison, 1983 ). The third-person effect describes the persistent phenomenon that people perceive communication effects on others as stronger than on oneself. This phenomenon applies to a variety of communication forms, including social media effects and online news perception (e.g., Banning & Sweetser, 2007 ; Houston, Hansen, & Nisbett, 2011 ; Schweisberger, Billinson, & Chock, 2014 ). We thus expected similar results with respect to YTPS-videos and explored the following question:

How strongly do young people of different age and gender perceive their own as well as other young people’s influenceability by the content of YTPS-videos?

Communication about the Content of YTPS-Videos

Finally, seeking the advice of others is a vital strategy to verify, evaluate and validate online information (Metzger et al., 2003 ). People use interpersonal communication via social media to confirm their own opinion, to obtain personal recommendations, or to orientate themselves by feedback systems (Metzger, Flanagin, & Medders, 2010 ). Thereby, some sources are perceived as more trustworthy than others: People prefer the recommendations and opinions of friends and family. Indeed, online comments of users affect news processing and credibility perception of news content and sources (Duong, Nguyen, & Vu, 2020 ; Waddell, 2018a , 2018b ). Referring to the communication channels, the use of a particular communication channel apparently depends on the type of friend (strong versus weak ties) and the communication subject (school subject versus no school subject) (Van Cleemput, 2010 ). In line with that, when sharing emotions, Flemish adolescents were found to prefer talking face-to-face, followed by texting, calling, and posting on social networks (Vermeulen, Vandebosch, & Heirman, 2018 ). Additionally, males seem to tend to communicate more frequently via public comments on YouTube videos but show less video-sharing behaviour with others than females do (Khan, 2017 ). Therefore, concerning YTPS-videos, we examined with whom and via which channels young people of different age and gender talk about the content of such videos.

With whom do young people of different age and gender communicate about the content of YTPS-videos?

Which channels do young people of different age and gender use to communicate with others about YTPS-videos?

We created both a pencil-paper and an online version of the survey with the software Unipark (Questback, 2017 ). The pencil-paper version was distributed among pupils of cooperating schools and students of a large German university. Written informed consent to participate was provided by the pupils’ legal guardians/next of kin, and all of them participated voluntarily in this study in the context of formal school teaching. An online version of the questionnaire was additionally distributed via specific participant recruitment groups on Facebook in order to reach groups of older people with a serious interest in participating in scientific research. After clicking on the link to open the study, we pointed out that participation in the online survey required a minimum age of 16 years, following the guidelines of the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Parliament (GDPR, 2016 ). We also informed the participants that they could stop the study whenever they want, and that completion of the survey would indicate informed consent. We did not collect any identifying personal data.

Overall 739 participants (577 pencil-paper, 162 online) took part in the survey. We initially excluded 135 participants (18.27%) from the analyses as they reported neither using YouTube in general nor consuming YouTuber videos about political or societal issues (YTPS-videos), further 7 participants (0.95%) for not completing the survey, further 11 participants (1.49%) due to missing data regarding age or gender, further 9 participants (1.22%) for defining their gender as ‘others’, which was an insufficient subsample for the gender-related statistical analyses, and further 15 participants (2.03%) for reporting being older than 35 years. Therefore, the data of 562 participants (440 pencil-paper, 122 online) with 59.07% females were included in the analyses. The mean age was M age = 18.87 ( SD age = 4.86). The number of subscribed YouTube channels reported by these participants showed a median of 10. At the time of the survey, 55.0% of the participants were pupils of secondary schools, 40.2% were students of a University, and 4.8% attended neither of these. We divided participants into three different age groups to examine age effects: Participants who were under the age of 16 and therefore not authorized by law to vote in Germany ( n = 205, 48.29% female; M age = 14.39, SD age = 0.64), young people from 16 to 20 years of age ( n = 156, 62.18% female; M age = 17.64, SD age = 1.66), and participants older than 20 years of age (range from 21 to 35 years) and therefore legally get full criminal responsibility as an adult in Germany ( n = 201, 67.66% female; M age = 24.39, SD age = 3.34). The number of participants slightly varied across the analyses due to occasional missing data.

Questionnaire

The introduction of the survey included our definitions of the terms “YouTuber” and their “YTPS-videos”. We defined YouTubers as people who run their own YouTube channel and upload regularly or irregularly self-produced videos on YouTube. Thus, we clarified that the survey is not about videos produced by professional news broadcasters that additionally disseminate their news via YouTube. We defined YTPS-videos as videos of any kind of format addressing political or societal topics.

We initially asked the participants to indicate a few demographical information: age, gender, school, previous graduation (if they already had one), and their occupational status (if they were not attending any school). If not stated otherwise, each of the following questions was answered on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (“not at all” or “never”) to 5 (“very much” or “very often”).

First, we assessed participants’ YouTube usage intensity. We asked them how intensively they use YouTube in general, how frequently they watch YTPS-videos, and how frequently they visit YouTuber channels on a 6-point scale (1 = “every day”, 2 = “every week, but not every day”, 3 = “every month, but not every week”, 4 = “every year, but not every month”, 5 = “less than once a year”, 6 = “never”), see Table 1 .

Second, we assessed participants’ evaluation of the credibility of YouTubers and their videos. As shown in Table 1 , we asked them to estimate the credibility of YTPS-videos in general, how much they appreciate it when YouTubers present their own opinion in their YTPS-videos, and to evaluate their personal liking of YTPS-videos in general (−2 = “very negative”, 0 = “neutral”, +2 = “very positive”). Furthermore, the participants rated several characteristics of YouTubers and their videos they potentially regard as indicative of Fake News (1 = “no indicator at all”, 3 = “medium indicator”, 5 = “very strong indicator”). The full list of evaluated characteristics can be seen in Table 1 .

Third, participants compared YTPS-videos with classic TV news. To do so, they assessed 20 characteristics whether these apply rather to YTPS-videos or to TV news (1 = “applies much more to YTPS-videos”, 3 = “applies equally to both formats”, 5 = “applies much more to TV news”). Importantly, numeric markers were introduced for the analyses but were not shown to the participants in order not to bias their ratings. We only presented the verbal markers to the participants. The full list of evaluated characteristics is presented in Table 2 .

Fourth, we assessed participants’ learning and perceived influenceability by YTPS-videos. On the one hand, participants rated the importance of YTPS-videos for their learning about politics and societal topics. We asked them how important YTPS-videos are to them as a source of information, how much they learn by watching such videos, and how strongly they use the content of YTPS-videos for their opinion formation. We calculated a mean score across these items (Cronbach’s α = .811). On the other hand, participants assessed how strongly they let themselves be influenced by YTPS-videos and to what extent other people of the same age, younger people, and older people are influenced by such videos.

Fifth, we assessed the extent to which YouTubers are perceived as role models. Participants rated several items regarding their perception of YouTubers’ role model function. The full list of items is presented in Table 3 .

Finally, we examined participants’ communication about the content of YTPS-videos. Participants rated the frequency of talking with certain communication partners and the communication channels they use. The full list of communication partners and channels is presented in Table 4 .

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 27. In order to quantify the extent of participants’ evaluations of YouTubers and YTPS-videos as below-average, average, or above-average compared to the scale’s midpoint, we conducted one-sample t -tests. We analysed possible main and interaction effects of age group (< 16 years, 16–20 years, > 20) and gender using 3 × 2 ANOVAs. In case of a significant main effect of age group, we performed pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni-corrected familywise error rate). All tables display the means and standard deviations for age and gender groups, indicate the results of the one-sample t -tests, and present the results of the ANOVAs including pairwise comparisons for age groups. Moreover, due to multiple testing and accumulated Type I error, we further report Bonferroni-adjusted significance levels for each set of t -tests and each set of ANOVAs associated with a research question. However, due to the explorative nature of the present study and because several authors have already pointed out that the Bonferroni method is unnecessarily conservative in case of many tests and hence increases the false-negative rate (e.g., Jafari & Ansari-Pour, 2019 ; Lee & Lee, 2018 ), we also discuss effects being significant only in the case of unadjusted significance levels. As the results are the first of its kind, applying a stricter criterion could otherwise obscure essential effects. Nevertheless, we additionally indicate the more conservative (adjusted) significance levels in the tables and figure for transparency reasons.

YouTube Watching Habits (RQ1)

As shown by Table 1 , the general YouTube usage intensity was consistently rated as above average across age groups and genders. Visiting frequency of YouTuber channels was consistently under the scale’s midpoint, indicating an above-average frequency due to reversed item coding (1 = “every day”, 6 = “never”). The watching frequency of YTPS-videos was stated to be either average or below average across groups. Besides, males reported a higher general usage intensity of YouTube, a higher visiting frequency of YouTube channels, and a higher watching frequency of YTPS-videos. The 16- to 20-year-old participants stated a higher usage intensity of YouTube compared to the other two age groups. The over-20-years-old group stated a lower visiting frequency of YouTuber channels than the other two groups (reversed coding) but reported to watch YTPS-videos more frequently than the under-16-year-old group. Since the scale measuring the visiting frequency of YouTuber channels was rather ordinal level, we also performed non-parametric analyses that verified the parametric results reported in Table 1 .

Evaluation of YTPS-Videos and Fake News Indicators (RQ2a, RQ2b)

Only the under-16-year-old males evaluated the credibility of YTPS-videos above average (see Table 1 ), whereas each of the other groups rated the credibility as either average or below average (RQ2a). The appreciation of the presentation of YouTubers’ own opinion in YTPS-videos was average or above average, while the liking of YTPS-videos was rated as above average (scale’s midpoint was zero). The over-20-year-old evaluated YTPS-videos as less credible and reported a lower appreciation of YouTubers’ own opinion than both younger age groups. Further, they stated a lower liking of YTPS-videos than the 16- to 20-year-old group. There was no effect of gender. Additionally, we found significant positive correlations between the credibility evaluation and the watching frequency of YTPS-videos for over-20-year-old males, r = .283, p = .023, and females, r = .287, p < .001. There were no significant correlations in the other age groups regardless of gender, all r s ≤ .194, p s ≥ .057. Besides, we found significant positive correlations between the credibility evaluation and the appreciation of the presentation of YouTubers’ own opinion in all groups, with the highest values for over-20-year-old males, r = .406, p < .001, and females, r = .331, p < .001. Except for 16- to 20-year-old males, we also found significant positive correlations between the credibility evaluation and liking of YTPS-videos in all groups, with the highest expression for over-20-year-old males, r = .374, p = .002, and females, r = .480, p < .001.

Regarding characteristics of YouTubers and their videos considered as potentially indicative of fake news (RQ2b), most mean ratings were average or below average (see Table 1 ). As an exception, the citation of information sources was considered as indicative above average by over-20-year-old males and females. The extent of visible commercialisation of YTPS-videos was considered as indicative above average by under-16-year-old males as well as by 16- to 20-year-old and over-20-year-old females. The ANOVAs did not find differences between males and females, but some main effects of age group: The under-16-year-old group rated the YouTubers’ language style as a less strong indicator than the 16- to 20-year-old group. Concerning the citation of information sources, YouTubers’ attempt to be a role model, and the extent of personal advice given by the YouTubers, the under-16-year-old group perceived them as less strong indicators of fake news than the over-20-year-old group did. Furthermore, we found an interaction between age and gender regarding the extent to which YouTubers’ express their own opinion in YTPS-videos: Females showed a higher rating than males in the group of the under-16-year-old group, t (202) = 2.76, p = .006, d = 0.386, whereas no gender difference was found in the other two age groups. There was also an interaction effect between age and gender relating to the extent of visible commercialisation in YTPS-videos, as females showed a higher rating than males only in the 16- to 20-year-old group, t (149) = 2.03, p = .044, d = 0.343.

YTPS-Videos Versus TV News (RQ2c)

Participants rated whether several characteristics apply rather to YTPS-videos or traditional TV news (RQ2c), see Table 2 . Ratings that significantly differed from 3 indicate that the corresponding characteristic was attributed more to YouTuber news (below 3) or more to TV news (above 3). Overall, TV news was seen as more objective, facts-oriented, informative, boring, credible, neutral, reputable, and professional, independently of participants’ age and gender. In contrast, YTPS-videos were generally seen as more subjective, opinion-oriented, entertaining, emotional, funny, exciting, modern, motivating, and manipulative. Both formats were rated as equally interesting. The characteristics “compact” and “exhausting” were equally attributed to both news formats or rather to TV news, depending on age and gender. Moreover, the ANOVAs revealed some main effects of gender and age group: In contrast to male participants, female participants rated TV news as more objective, facts-oriented, informative, exciting, credible, neutral, reputable, and compact, but they rated YTPS-videos as more subjective, opinion-oriented, emotional and manipulative. Regarding age, the over-20-year-old group rated YTPS-videos as less opinion-oriented, entertaining, and motivating than the other two age groups, but they also rated TV news as less neutral. Besides, they also perceived YTPS-videos as less exciting than the 16–20-year-old group, and as less manipulative than the under-16-year-old group. At last, they rated TV news as less exhausting compared to the under-16-year-old group. There was no interaction effect between age and gender on any of the characteristic ratings.

YouTubers as Role Models (RQ2d)

According to participants’ perception, YouTubers have a role model function, are important as role models, are aware of their role model function and their influence on viewers, and they are similar to music and movie stars regarding their role model function (see Table 3 ). Corresponding ratings showed an at least average mean value in all genders and age groups (with one exception). In contrast, participants rather denied that YouTubers show responsible handling of their role model function. Moreover, females perceived a greater role model function of YouTubers than males did. Regarding age effects, the under-16-year-old group perceived a weaker role model function but better responsible handling than the 16- to 20-year-old group. Finally, the perceived importance of YouTubers as role models and their similarity to music and movie stars significantly increased from age group to age group.

Learning and Influenceability (RQ3a, RQ3b)

Regarding the importance of YTPS-videos for participants’ learning about politics and societal topics (RQ3a), we found below-average ratings independently of age and gender, all t s ≤ −2.72, p s ≤ .009, d s ≤ −.354 (adjusted significance level p = .0083). However, YTPS-videos were rated as more important for learning by male participants ( M = 2.56, SD = 0.91) than by female participants ( M = 2.33, SD = 0.93), F (1, 556) = 7.28, p = .007, η p 2 = .013. There were no further main or interaction effects, all F s ≤ 2.59, p s ≥ .076, η p 2 ≤ .009.

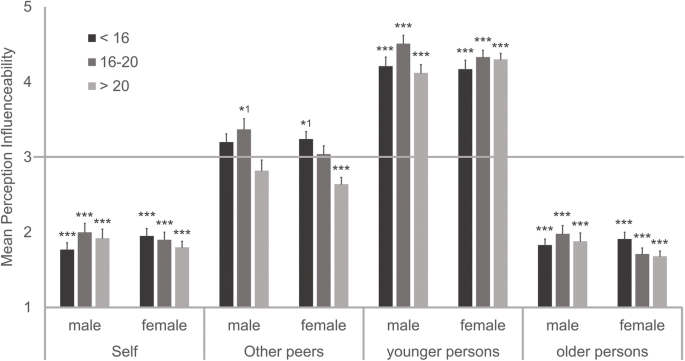

Regarding the perceived influenceability by YTPS-videos (RQ3b), Fig. 1 shows participants’ assessments of how strongly they let themselves be influenced and to what extent other people of the same age, younger people, and older people are presumed to be influenceable by such videos. Males and females in all age groups consistently perceived their own and older people’s influenceability as below average, whereas younger persons’ influenceability was consistently rated as above average. In contrast, the three age groups perceived a different influenceability of other people of the same age (i.e., other peers): The under-16-year-old males, the over-20-years-old males, and 16- to 20-years-old females rated them as averagely influenceable. The over-20-year-old females reported a below-average rating, and the other two groups an above-average rating. Next, we extended our usual two-way ANOVA to a 3 (age group) × 2 (gender) × 4 (valuation subject) ANOVA with valuation subject as a within-subject factor (self vs. other people of same age vs. younger people vs. older people) and perceived influenceability by YTPS-videos as dependent variable. We also calculated Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons in case of a significant main effect of valuation subject. We found a main effect of valuation subject, F (2.64, 1459.50) = 894.23, p < .001, η p 2 = .618: The participants perceived themselves and older people as less influenceable than younger people and people of the same age. Besides, the influenceability of younger people was rated higher than that of people of the same age. We found a main effect of age group, F (2, 552) = 5.32, p = .005, η p 2 = .019: The over-20-year-old group estimated people’s influenceability lower than the other two age groups. However, we also found an interaction between age group and valuation subject, F (5.29, 1459.50) = 4.17, p < .001, η p 2 = .015: The effect of age group was only significant regarding the evaluation of other people of the same age, F (2, 556) = 14.50, p < .001, η p 2 = .050.

Participants’ assessments of the influenceability of themselves, other peers, younger persons, and older persons by YTPS-videos. Vertical lines indicate the standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate the results of one-sample t -tests against the scales’ midpoint of 3. 1 The respective test result is not significant when applying the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level ( p = .002) to the set of t -tests

Communication about YTPS-Videos (RQ4a, RQ4b)

Concerning the participants’ communication partners regarding the content of YTPS-videos (RQ4a), we found that participants of both genders and all age groups reported a below-average communication frequency with the presented communication partners, but preferred communicating with their friends instead of teachers, see Table 4 . The ANOVAs revealed that males communicated more often with friends and classmates. Furthermore, the over-20-year-old group talked with their family members (including parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents) less often about the content of YTPS-videos than the younger age groups did. We additionally found two interactions between age group and gender: In the 16- to 20-year-old group, males communicated more often with their family than females did, t (153) = 2.35, p = .020, d = .390. Furthermore, males communicated more often with their friends than females in the under-16-year-old group, t (192.31) = 2.36, p = .019, d = .328, and in the 16–20-year-old group, t (154) = 22.19, p = .030, d = .362.

In terms of the communication channels the participants use when communicating about the content of YTPS-videos (RQ4b), face-to-face communication was the most preferred modus, see Table 4 . All other channels were used relatively rarely. We found several main effects of gender and age group, but no interactions: Males, compared to females, communicated more frequently via YouTube comments, Facebook’s news feed, E-Mail, Skype, and face-to-face. The over-20-year-old group used the Facebook’s news feed and phone calls more often, but they communicated via Snapchat and Instagram less frequently about the content of YTPS-videos than the other two age groups. Also, the over-20-year-old group communicated via E-Mail and Skype more often than the under-16-year-old group. Additionally, the 16- to 20-year-old group talked face-to-face more frequently compared to the other two age groups.

The present study examined the role of YTPS-videos and YouTubers for young people’s opinion formation on political and societal topics.

First, we found that young people reported a generally high YouTube usage intensity and a moderate watching frequency of YTPS-videos (RQ1), indicating that YouTube was an important information source in our sample. While general usage intensity was exceptionally high in the 16- to 20-year-old group, the over-20-year-old group less often visited YouTube channels but showed an even higher watching frequency of YTPS-videos compared to the under-16-year-old group. Notably, males reported an overall higher YouTube consumption.

Second, participants’ responses reflected some critical perceptions of YTPS-videos and YouTubers, as already found in other subject areas (Martínez & Olsson, 2019 ). Though the liking of YTPS-videos was relatively high, participants perceived them as only moderately credible (RQ2a). The over-20-year-old evaluated YTPS-videos as less credible and reported a lower appreciation of YouTubers’ own opinion than both younger age groups. Further, they stated a lower liking of YTPS-videos than the 16- to 20-year-old group. These results indicate that young people’s critical perception of YTPS-videos increases with age, while there was no effect of gender. Interestingly, credibility evaluation was positively correlated with viewing frequency in the oldest age group. Also, we found positive correlations between the credibility evaluation and the appreciation of the presentation of YouTubers’ own opinion in all groups, but the highest correlations were found in the over-20-year-old group. Hence, credibility seems to become a more critical factor for consumption frequency and media acceptance with increasing age, supporting previous findings (Nelson & Kim, 2020 ).

Third, participants moderately agreed to all characteristics of YTPS-videos and their producers as being indicative of fake news (RQ2b). This result also considerably varied between age groups. Again, the over-20-year-old group appeared to be more critical than the under-16-year-old group regarding the citation of information sources, YouTubers’ attempt to be a role model, and the extent of personal advice given by the YouTubers. Gender differences were negligible. Very young people may struggle with the evaluation of online news as already observed in previous studies (Flanagin & Metzger, 2000 ; McGrew, Breakstone, Ortega, Smith, & Wineburg, 2018 ; Metzger et al., 2003 ; Nee, 2019 ). This would also underline the importance of a tool for reconnaissance to improve media criticism in the context of fake news on YouTube, as it was suggested by McGrew et al. ( 2018 ). Young people could also refer to other characteristics than those addressed in the present study and previously reported by Hugger et al. ( 2019 ), for example design, graphics, and multimedia content (Agosto, 2002 ; Shenton & Dixon, 2004 ; Wobbrock, Hsu, Burger, & Magee, 2019 ).

Fourth, we found a very pronounced difference in participants’ evaluation of YTPS-videos compared to traditional TV news (RQ2c). The latter was perceived as more objective, facts-oriented, informative, credible, neutral, reputable, and professional but also more boring, independently of participants’ age and gender. In contrast, YTPS-videos were generally seen as more entertaining, emotional, funny, exciting, modern, motivating, but also more subjective, opinion-oriented, and manipulative than traditional TV news, independently of age and gender. This result pattern is compatible with the findings of Elvestad, Phillips, and Feuerstein ( 2017 ) who surveyed students from Israel, Norway, and the United Kingdom, all reporting higher trust in traditional news media than in social media. Such results may reflect a critical perception or even scepticism of YTPS-news on the one hand. On the other hand, it also indicates a rather uncritical perception of TV news and only a little critical reflection on traditional journalism processes. With respect to age, we found that the over-20-year-old group showed a more balanced comparison between traditional TV news and YTPS-news. Surprisingly, female participants, compared to male participants, rated TV news as more objective, facts-oriented, informative, exciting, credible, neutral, reputable, and compact, and they rated YTPS-videos as more subjective, opinion-oriented, emotional, and manipulative. We may speculate that this result pattern either shows a higher capacity for media criticism in young females or a greater orientation towards supposedly valid media standards. Future research should disentangle these possibilities in more detail.

Fifth, participants ascribed YouTubers an important role model function and a high awareness of their influence, independently of gender and age (RQ2d). In addition, they criticised YouTubers’ rather irresponsible handling of their role model function. The perceived importance of YouTubers as role models and their similarity to music and movie stars increased from age group to age group. De Veirman et al. ( 2019 ) already stressed the importance of influencers as relatable and approachable role models as children are willing to build (parasocial) relationships and to identify with them. Thus, this is a critical mixture. On the one hand, YouTubers are vital role models, but in contrast to traditional celebrities, the perceived distance is less pronounced, increasing their potential effects on the young audience. As found by Schouten et al. ( 2020 ), recipients tend to identify more with, feel more similar to, and trust influencers more compared to celebrities. Interestingly, participants of the present study, independently of age and gender, also assumed that YouTubers would be only moderately aware of their role model function. To sum up, the participants seem to (partially) understand and critically reflect on the YouTubers’ roles and potential effects.