- Newsletters

These scientists are working to extend the life span of pet dogs—and their owners

Anti-aging drugs are being trialed in companion dogs—but the goal is to find ways to have people, as well as beloved pets, live longer, healthier lives.

- Jessica Hamzelou archive page

Matt Kaeberlein is what you might call a dog person. He has grown up with dogs and describes his German shepherd, Dobby, as “really special.” But Dobby is 14 years old—around 98 in dog years. “I’m very much seeing the aging process in him,” says Kaeberlein, who studies aging at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Kaeberlein is co-director of the Dog Aging Project , an ambitious research effort to track the aging process of tens of thousands of companion dogs across the US. He is one of a handful of scientists on a mission to improve, delay, and possibly reverse that process to help them live longer, healthier lives.

The Dog Aging Project is just one of several groups seeking to understand and improve dog aging. Biotech company Loyal has plans to offer life extension for dogs. And a third group, running a project called Vaika, is looking for ways to lengthen life span through a study on retired sled dogs.

But dogs are just the beginning. Because they are a great model for humans, anti-aging or life-span-extending drugs that work for dogs could eventually benefit people, too. In the meantime, attempts to prolong the life of pet dogs can help people get onboard with the idea of life extension in humans, say researchers behind the work. “It will go a long way to convincing people that this is possible [in humans],” says Kaeberlein. “Aging is modifiable.”

For the love of dog

“I love dogs,” says Kate Creevy, who studies dog aging and infectious disease in animals at Texas A&M University in College Station. “You’re not motivated to do this work if you don’t love dogs.” Creevy, who is also chief veterinary officer of the Dog Aging Project, is one of around 40,000 people with a dog enrolled in the study.

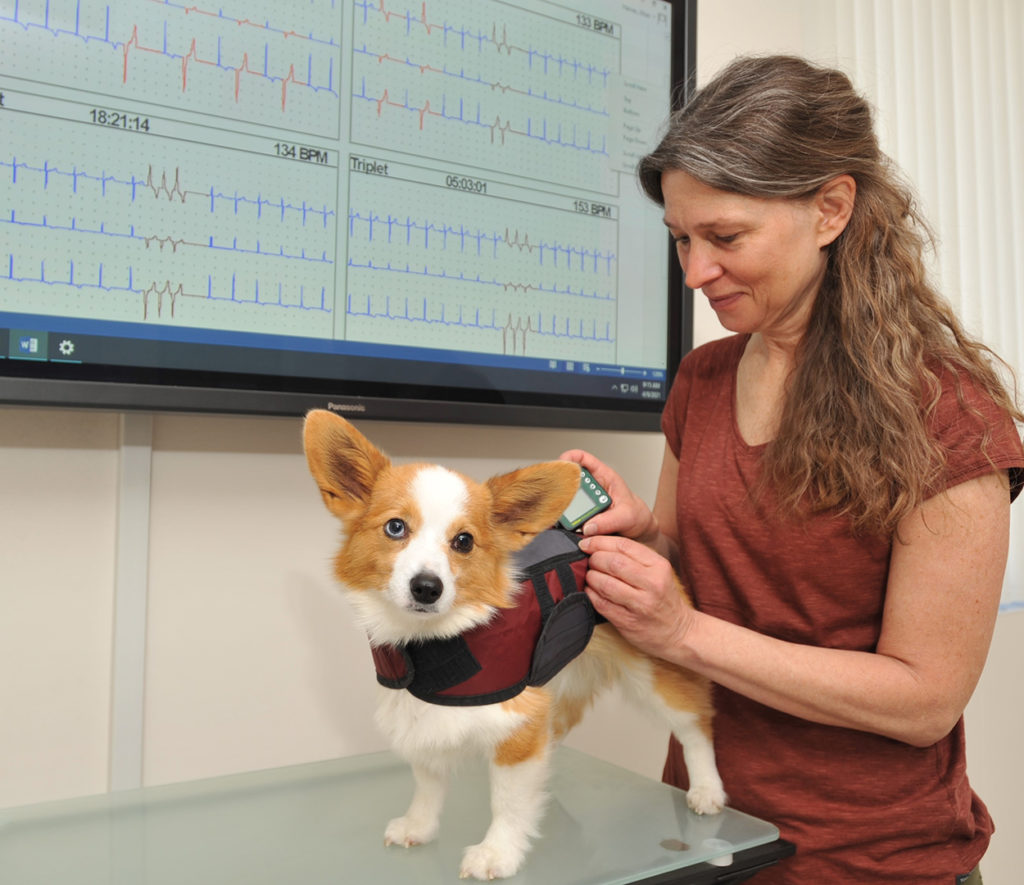

All participants provide their pet dog’s medical history and complete detailed surveys on an annual basis. “It takes about three hours,” says Creevy. A subset of around 8,500 dogs will have their genomes sequenced, and some of these will have their hair, blood, and urine studied as well.

Smaller groups of dogs are being more closely studied for specific disorders. The team will assess 200 dogs with a form of dementia known as canine cognitive dysfunction, or CCD, for example.

The idea is to find biological clues that might help identify which dogs might be at risk of developing such diseases in the future—and eventually aid the discovery of drugs that might prevent or treat them. The team also hopes to find out which aspects of a dog’s lifestyle might help extend its “health span,” the number of years lived in good health.

“We expect to learn which types of diets, which types of exercise regimes, and which types of husbandry are associated with better long-term outcomes,” says Creevy, “so that we can do things that help them have a better quality of life into their later years.”

“I was like, man, I would love if I could slow aging in my dog.” Matt Kaeberlein, co-director of the Dog Aging Project

But the research has another goal. Kaeberlein says his “lightbulb moment” occurred around 10 years ago, when he suddenly realized that not only would such research reveal how dogs age—it might identify ways to slow the process. “I was like, man, I would love if I could slow aging in my dog,” he recalls.

The Dog Aging Project will trial potential anti-aging drugs among groups of pets. The first being studied is rapamycin , a drug that has been found to extend the lives of flies, worms, and mice in the lab. Rapamycin is thought to mimic the effects of caloric restriction, which has been shown to help multiple species live longer . The drug works by blocking a molecule called mTOR, which controls cell growth and metabolism and responds to nutrient intake. “I’m convinced that some of the interventions that we know extend life span and health span in mice will work in dogs,” says Kaeberlein. “It’s really just a matter of showing it through clinical trials.”

Kaeberlein and his colleagues are currently trialing the drug in dogs age seven or older. So far, they have only run a couple of small trials designed to test its safety. In the latest—a six-month study involving around 17 dogs that has not yet been published—the drug appeared to be safe, says Kaeberlein.

Neither trial was large enough to test the effects of the drug. But the owners of dogs given rapamycin tended to report that the dogs became more active. These owners didn’t know whether their pet was being given the drug or a placebo. “So we think that’s probably a real effect,” says Kaeberlein. But he doesn’t know exactly what the effect might be. “It could be a decrease in pain or arthritis, or it could be that the drugs make dogs hyperactive,” he says.

To get a better idea, the team is currently enrolling 580 dogs in a larger clinical trial. For one year, half the dogs will get the drug, and half will be given a placebo. The team will then follow the health of the animals for another two years. They aim to find out whether the drug can extend the animals’ life span, but they will also look at the animals’ overall health—whether they develop cancer or heart disease, for example.

Saving sled dogs

Creevy, Kaeberlein, and their colleagues aren’t the only ones seeking to extend the life span of humans’ closest furry friend. Andrei Gudkov and his colleagues are taking a different approach.

Gudkov, a professor of oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, has long been interested in understanding aging. “Studying this in humans is … very impractical, because usually your own life is not long enough to see the fruits of your work,” he says. “A dog’s life is sufficiently shorter than a human life, and allows us to do reasonable experiments and see the results.”

He, Katerina Adrianova, and Daria Fleyshman are the founders of Vaika, a project to study aging—and attempt to slow or reverse it—in a group of dogs that have retired from sled racing. For the last four years or so, the team has collected dogs between eight and 11 years old from kennels in northern US states and Canada. The dogs are cared for at a site in Ithaca, New York, and carefully monitored until the end of their lives.

Gudkov’s focus is on DNA damage, which accumulates in an animal with age. This damage can provide a signal to the immune system to destroy affected cells, resulting in damage to tissues. Some of this DNA damage is caused by what Gudkov calls the retrobiome—fragments of ancient viruses that have been incorporated into our DNA over millions of years of evolution.

The parts of an animal’s DNA that contain these fragments are usually kept “silent” by epigenetic markers, says Gudkov, but the system seems to break down with age. Gudkov believes that these ancient virus fragments are a major cause of age-related decline in humans and other animals, including dogs.

His team is trialing an experimental anti-aging drug that he believes will stifle the activity of the retrobiome in the 103 dogs collected so far. If the drug can prevent DNA damage, it should allow the animals to live longer, healthier lives, says Gudkov. As part of the trial, half the dogs will receive the drug, while the other half will be given a placebo, and the team will look for signs of aging in all of them. Gudkov says he has some preliminary results but doesn’t want to make them public yet.

The Vaika study is a not-for-profit endeavor, and Gudkov describes it as a “hobby.” But Celine Halioua plans to make a business out of life extension in pet dogs. Halioua, another avowed “animal person,” founded the biotech startup Loyal to “explicitly develop drugs intended to increase life span and health span.”

Like the members of the Dog Aging Project and Vaika, Halioua’s team at Loyal is looking for biological clues that might hint at which animals are prone to faster aging and which are likely to enjoy a longer, healthier life.

As well as searching for markers in blood, saliva, and urine, Halioua’s team will look at epigenetic markers—chemical groups that attach to DNA and control how genes make proteins. These patterns appear to change over a lifetime, and some scientists have developed “aging clocks” to guess an organism’s biological age from that information.

The team at Loyal will soon be launching clinical trials of two drugs, which the company refers to as LOY-001 and LOY-002. Halioua won’t give much away about either one but says that the first is an implant aimed at larger dogs, which tend to have shorter life spans, while the second, a pill, will be trialed in older dogs of various breeds. The second drug works in a similar way to rapamycin, says Halioua.

Model behavior

If either drug works in dogs, it could also be tested in people—an eventual goal for Halioua. Dogs are an excellent model for studying human aging and any drugs that might slow or reverse it, say researchers contacted by MIT Technology Review .

Until fairly recently, most aging research has focused on yeast, worms, and mice in a lab. The work has revealed plenty of fascinating insights into how these organisms age —but the relevance of the findings to humans is up for debate.

Dogs provide a much better model for studying human aging. They are unique in sharing our environment. Pet dogs live in our homes with us, breathe the same air we do, and often share our exercise routines, to some degree. “They’re eating our food, they’re walking on our lawns with pesticide, they’re drinking whatever is in our water,” says Elaine Ostrander, who leads a team studying human and dog genetics at the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

They also develop many of the same age-related diseases that we do. Technically, most pet dogs die as a result of euthanasia. But in most of these cases, the animals have cancer, says Kaeberlein. Dogs can also develop heart disease in later life, just like humans. There are some differences—dog brains aren’t the same as human ones, although the animals do seem to develop a form of dementia. And dogs don’t tend to develop vascular diseases as humans do.

But there are plenty of similarities. Both dogs and people experience aging of the immune system and an increased risk of kidney disease as they get older, says Kaeberlein. “It seems like at the level of individual age-related diseases, it’s very, very similar,” he says.

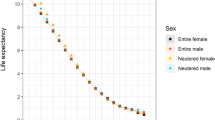

One main difference is that aging is a much quicker process in dogs—it happens around seven times faster than in humans, though small dogs generally live longer than larger ones. (It’s not quite the case that one year of dog life is equivalent to seven human years, however. Dogs seem to age more rapidly than humans do in their first years of life, and the pace slows as they get older.)

While this can be devastating for devoted owners, it is useful for researchers, who are able to study the effects of potential anti-aging drugs over the entire life span—something that is much more difficult to achieve in people.

Another unique feature of dogs is their incredible diversity. Only in dogs do we see such extreme differences in size and appearance within a single species. A Great Dane is around 20 times heavier than a Chihuahua, for example. A Pomeranian looks nothing like a Staffordshire bull terrier.

This variation makes the animals particularly fascinating to geneticists like Ostrander. “Dogs were only domesticated around 30,000 years ago, and most breeds have only been around since the Victorian times,” she says. It was around the mid-1800s that modern dog breeding took off, and owners bred dogs for aspects of their appearance, such as a curly coat or a flat face. Breeders essentially selected dogs with genes for these features.

Because many such modifications only occurred in the last hundred or so years, genetic differences between today’s dog breeds are likely to have a significant impact on these traits—and on the risks of certain diseases that vary between breeds.

This makes it much easier to identify genes of interest in dogs than in humans, says Ostrander. “For me as a geneticist, it’s kind of like being a kid in a candy shop,” she says. “I can figure out the main players [among genes] … then we can look at human health and human biology.”

Ostrander studies cancer, which affects different dog breeds differently. To learn more about bladder cancer, for example, she and her colleagues will study Scottish terriers and West Highland white terriers, which appear particularly prone to developing the disease. Her team will then compare the genomes of these dogs with those of other breeds that don’t get bladder cancer. “It becomes much, much easier to find those genes [linked to bladder cancer],” she says. “We don’t have a way to do that very efficiently in humans.”

Once the team has identified genes linked to a particular cancer, they inform other scientists who are working on human disease. “We can say … ‘These are the genes you want to look for [in humans] to see if you can develop targeted therapeutics,’” she says.

Researchers hope the same is true of aging—that in discovering genes linked to long, healthy life in dogs, we might also learn what might help humans live longer.

They also hope that any successful attempts at life extension in pet dogs will make human life extension more palatable. Halioua feels the field has “suffered from a branding issue” owing to outlandish claims made in the 1990s and 2000s. “Big names in the field were yelling about 1,000-year life spans and immortality,” she says. “To be clear, we’re not creating 1,000-year-old dogs.”

Not only were these claims unfounded, but they also led to concerns about economic equality. Who would get to live such a long life? And how would they be supported? “There is no societal strife caused by your dog living a few extra healthy years,” says Halioua. “It’s a nonthreatening way to introduce what is otherwise a very foreign idea.”

Biotechnology and health

This grim but revolutionary dna technology is changing how we respond to mass disasters.

After hundreds went missing in Maui’s deadly fires, rapid DNA analysis helped identify victims within just a few hours and bring families some closure more quickly than ever before. But it also previews a dark future marked by increasingly frequent catastrophic events.

- Erika Hayasaki archive page

Google helped make an exquisitely detailed map of a tiny piece of the human brain

A small brain sample was sliced into 5,000 pieces, and machine learning helped stitch it back together.

- Cassandra Willyard archive page

What’s next for bird flu vaccines

If we want our vaccine production process to be more robust and faster, we’ll have to stop relying on chicken eggs.

FDA advisors just said no to the use of MDMA as a therapy

The studies demonstrating MDMA’s efficacy against PTSD left experts with too many questions to greenlight the treatment.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 02 February 2022

An open science study of ageing in companion dogs

- Kate E. Creevy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4169-374X 1 ,

- Joshua M. Akey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4411-1330 2 ,

- Matt Kaeberlein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1311-3421 3 ,

- Daniel E. L. Promislow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7088-4495 3 , 4 &

The Dog Aging Project Consortium

Nature volume 602 , pages 51–57 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

52 Citations

914 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Genome-wide association studies

- Predictive markers

- Translational research

An Author Correction to this article was published on 08 August 2022

This article has been updated

The Dog Aging Project is a long-term longitudinal study of ageing in tens of thousands of companion dogs. The domestic dog is among the most variable mammal species in terms of morphology, behaviour, risk of age-related disease and life expectancy. Given that dogs share the human environment and have a sophisticated healthcare system but are much shorter-lived than people, they offer a unique opportunity to identify the genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors associated with healthy lifespan. To take advantage of this opportunity, the Dog Aging Project will collect extensive survey data, environmental information, electronic veterinary medical records, genome-wide sequence information, clinicopathology and molecular phenotypes derived from blood cells, plasma and faecal samples. Here, we describe the specific goals and design of the Dog Aging Project and discuss the potential for this open-data, community science study to greatly enhance understanding of ageing in a genetically variable, socially relevant species living in a complex environment.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death

Life tables of annual life expectancy and mortality for companion dogs in the United Kingdom

Going beyond established model systems of Alzheimer’s disease: companion animals provide novel insights into the neurobiology of aging

Data availability.

The data used to generate Fig. 1b, c are freely available for download at https://data.dogagingproject.org .

Change history

08 august 2022.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05179-x

Kaeberlein, M., Rabinovitch, P. S. & Martin, G. M. Healthy aging: the ultimate preventative medicine. Science 350 , 1191–1193 (2015). This paper makes a compelling argument that treatments that target the underlying causes of ageing could ameliorate the effects of multiple age-related diseases .

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Melzer, D., Hurst, A. J. & Frayling, T. Genetic variation and human aging: progress and prospects. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62 , 301–307 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Manolio, T. A. et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461 , 747–753 (2009).

Kaeberlein, M., Creevy, K. E. & Promislow, D. E. L. The Dog Aging Project: translational geroscience in companion animals. Mamm. Genome 27 , 279–288 (2016).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Boyko, A. R. et al. A simple genetic architecture underlies morphological variation in dogs. PLoS Biol. 8 , e1000451 (2010). This paper demonstrated the tremendous power of the domestic dog as a model for mapping natural variation for complex traits .

Minnema, L. et al. Correlation of artemin and GFRα3 with osteoarthritis pain: early evidence from naturally occurring osteoarthritis-associated chronic pain in dogs. Front. Neurosci. 14 , 77 (2020).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42 , 377–381 (2009).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 95 , 103208 (2019).

Li, J. H., Mazur, C. A., Berisa, T. & Pickrell, J. K. Low-pass sequencing increases the power of GWAS and decreases measurement error of polygenic risk scores compared to genotyping arrays. Genome Res. 31 , 529–537 (2021).

Franceschi, C. & Campisi, J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 , S4–S9 (2014).

Lippi, G. et al. Preanalytical challenges—time for solutions. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 57 , 974–981 (2019).

Haumann, R. & Verspaget, H. W. Quality-assured biobanking: the Leiden University Medical Center model. Methods Mol. Biol. 1730 , 361–370 (2018).

Simeon-Dubach, D., Zeisberger, S. M. & Hoerstrup, S. P. Quality assurance in biobanking for pre-clinical research. Transfus Med. Hemother. 43 , 353–357 (2016).

US Department of the Census. American Community Survey (ACS): Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), 2009. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR33802.v1 (Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2013).

Kim, S.-Y. et al. Concentrations of criteria pollutants in the contiguous U.S., 1979–2015: role of prediction model parsimony in integrated empirical geographic regression. PLoS ONE 15 e0228535 (2020).

Vose, R. S. et al. NOAA Monthly U.S. Climate Divisional Database (NClimDiv). https://doi.org/10.7289/V5M32STR (NOAA National Climatic Data Center, 2014).

Mooney, S. J. et al. Residential neighborhood features associated with objectively measured walking near home: revisiting walkability using the Automatic Context Measurement Tool (ACMT). Health Place 63 , 102332 (2020).

Wilfond, B. S., Porter, K. M., Creevy, K. E., Kaeberlein, M. & Promislow, D. Research to promote longevity and health span in companion dogs: a pediatric perspective. Am. J. Bioeth. 18 64–65 (2018).

Taylor, H. A., Morales, C., Johnson, L.-M. & Wilfond, B. S. A randomized trial of rapamycin to increase longevity and healthspan in companion animals: navigating the boundary between protections for animal research and human subjects research. Am. J. Bioeth. 18 , 58–59 (2018).

Bisong, E. in Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners (ed. Bisong, E.) 7–10 (Apress, 2019).

Salvin, H. E., McGreevy, P. D., Sachdev, P. S. & Valenzuela, M. J. The canine cognitive dysfunction rating scale (CCDR): a data-driven and ecologically relevant assessment tool. Vet. J. 188 , 331–336 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

All dog research described here, including informed owner consent, is approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, under AUPs 2018-0401 CAM and 2018-0368 CAM. The DAP is supported by grant U19AG057377 from the National Institute on Aging, a part of the National Institutes of Health, and by private donations. We thank S. Moon for help in preparing figures.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, College Station, TX, USA

Kate E. Creevy, Brian G. Barnett, Lucy Chou, Jeremy Evans, Jonathan M. Levine, Kellyn E. McNulty, Amanda K. Tinkle & M. Katherine Tolbert

Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA

Joshua M. Akey & William Thistlethwaite

Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

Matt Kaeberlein, Daniel E. L. Promislow, Brooke Benton, Erica C. Jonlin & Silvan R. Urfer

Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Daniel E. L. Promislow

Department of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Elhanan Borenstein

Blavatnik School of Computer Science, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM, USA

Cornell Veterinary Biobank, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Marta G. Castelhano

Department of Sociology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Devin Collins, Kyle Crowder & Hannah Lee

Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, Athens, GA, USA

Amanda E. Coleman

Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology, Seattle, WA, USA

Kyle Crowder & Matthew D. Dunbar

Department of Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, College Station, TX, USA

Virginia R. Fajt

Department of Family Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Annette L. Fitzpatrick

Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Annette L. Fitzpatrick & Stephen M. Schwartz

Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, College Station, TX, USA

Unity Jeffery

Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Erica C. Jonlin

Bioinformatics and Integrative Biology, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

Elinor K. Karlsson & Kathleen Morrill

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA

Elinor K. Karlsson

Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Kathleen F. Kerr, Robyn L. McClelland & Yunbi Nam

Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Department of Population Health Sciences, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Audrey Ruple

Epidemiology Program, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Stephen M. Schwartz

Collaborative Health Studies Coordinating Center, Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Sandi Shrager

School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Noah Snyder-Mackler

Center for Evolution and Medicine, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

School for Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA, USA

Benjamin S. Wilfond

Division of Bioethics and Palliative Care, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Kate E. Creevy

- , Joshua M. Akey

- , Matt Kaeberlein

- , Daniel E. L. Promislow

- , Brian G. Barnett

- , Brooke Benton

- , Elhanan Borenstein

- , Marta G. Castelhano

- , Lucy Chou

- , Devin Collins

- , Amanda E. Coleman

- , Kyle Crowder

- , Matthew D. Dunbar

- , Jeremy Evans

- , Virginia R. Fajt

- , Annette L. Fitzpatrick

- , Unity Jeffery

- , Erica C. Jonlin

- , Elinor K. Karlsson

- , Kathleen F. Kerr

- , Hannah Lee

- , Jonathan M. Levine

- , Robyn L. McClelland

- , Kellyn E. McNulty

- , Kathleen Morrill

- , Yunbi Nam

- , Audrey Ruple

- , Stephen M. Schwartz

- , Sandi Shrager

- , Noah Snyder-Mackler

- , William Thistlethwaite

- , Amanda K. Tinkle

- , M. Katherine Tolbert

- , Silvan R. Urfer

- & Benjamin S. Wilfond

Contributions

K.E.C., M.K. and D.E.L.P. conceived of the DAP; J.M.A., K.E.C., M.K. and D.E.L.P. wrote the initial draft of this paper. All authors, including consortium authors, have been involved in the design and implementation of DAP goals, infrastructure and activities, and they have had the opportunity to participate in editing both form and content of this paper and have approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel E. L. Promislow .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature thanks Steven Austad, Dario Valenzano and Eric Verdin for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Creevy, K.E., Akey, J.M., Kaeberlein, M. et al. An open science study of ageing in companion dogs. Nature 602 , 51–57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04282-9

Download citation

Received : 27 May 2021

Accepted : 24 November 2021

Published : 02 February 2022

Issue Date : 03 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04282-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The companion dog as a model for inflammaging: a cross-sectional pilot study.

- Sarah M. Schmid

- Jessica M. Hoffman

GeroScience (2024)

Generating Detailed Spectral Libraries for Canine Proteomes Obtained from Serum and Urine

- Hee-Sung Ahn

- Jeonghun Yeom

- Kyunggon Kim

Scientific Data (2023)

Targeting the biology of aging with mTOR inhibitors

- Joan B. Mannick

- Dudley W. Lamming

Nature Aging (2023)

Body size awareness matters when dogs decide whether to detour an obstacle or opt for a shortcut

- Péter Pongrácz

- Petra Dobos

- Rita Lenkei

Scientific Reports (2023)

- Alexandra A. de Sousa

- Brier A. Rigby Dames

- Christine J. Charvet

Communications Biology (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

- Biological Mechanisms of Healthy Aging Training Program

- UW Nathan Shock Center

- HALO Director

- Administration

- HALO Faculty

- HALO Executive Committee

- BMHA Post-Doctoral Trainee

- BMHA Pre-Doctoral Trainee

The Dog Aging Project

The Dog Aging Project is an innovative project that brings together a community of dogs, owners, veterinarians, researchers, and volunteers to carry out the most ambitious canine science health study in the world. Our work is centered on two fundamental goals: understanding how biology, lifestyle, and environment influence aging and intervening to increase healthspan, the period of life spent free from disease.

The DAP team of 40+ researchers is led by HALO Faculty Member Dr. Daniel Promislow and Former HALO Director Dr. Matt Kaeberlein at the University of Washington and Dr. Kate Creevy at Texas A&M. They have built a collaborative, open data research platform that harnesses the power of citizen science, allowing dog owners to participate in our research efforts. This culture of collaboration fosters creative partnerships, which include experts from diverse disciplines and top research institutions around the world. Major sources of funding include the Donner Foundation, the Irish Wolfhound Association of New England (IWANE), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant U19AG057377).

Currently there are four major research components:

Project 1. Defining frailty and successful aging in dogs. Unlike in humans, there are no clearly defined metrics to determine how well a dog is aging, no canine equivalent of the chair stand test or grip strength , nor predefined age-specific ranges for clinical chemistry measures. To fill this gap, we will develop new metrics of canine aging.

Project 2. Genetic analysis of aging in dogs. Genome sequence data for >10,000 canine participants will be integrated with health measures and behavioral traits to carry out comprehensive genome-wide association studies.

Project 3. Systems biology of healthy aging in dogs. We will identify molecular biological predictors of disease and longevity and develop an epigenetic clock that predicts biological age in dogs.

Project 4. TRIAD—Rapamycin Intervention Study. We will conduct a large-scale trial of FDA-approved rapamycin , a drug shown to increase lifespan and delay the negative effects of aging in mice. We will test the effects of the drug on cognitive function, heart function, immunity, and cancer incidence in 500 middle-aged dogs.

To learn more, please visit the Dog Aging Project website .

- Online Privacy Statement

- Policies and Notices

- Copyright And Healthcare Disclaimer

- Website Terms And Conditions Of Use

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Scientists Scramble to Keep Dog Aging Project Alive

The National Institute on Aging may let funding lapse for a yearslong study of nearly 50,000 pet dogs, which could also offer insight into human health.

By Emily Anthes

In late 2019, scientists began searching for 10,000 Americans willing to enroll their pets in an ambitious new study of health and longevity in dogs. The researchers planned to track the dogs over the course of their lives, collecting detailed information about their bodies, lifestyles and home environments. Over time, the scientists hoped to identify the biological and environmental factors that kept some dogs healthy in their golden years — and uncover insights about aging that could help both dogs and humans lead longer, healthier lives.

Today, the Dog Aging Project has enrolled 47,000 canines and counting, and the data are starting to stream in. The scientists say that they are just getting started.

“We think of the Dog Aging Project as a forever project, so recruitment is ongoing,” said Daniel Promislow, a biogerontologist at the University of Washington and a co-director of the project. “There will always be new questions to ask. We want to always have dogs of all ages participating.”

But Dr. Promislow and his colleagues are now facing the prospect that the Dog Aging Project might have its own life cut short. About 90 percent of the study’s funding comes from the National Institute on Aging, a part of the National Institutes of Health, which has provided more than $28 million since 2018. But that money will run out in June, and the institute does not seem likely to approve the researchers’ recent application for a five-year grant renewal, the scientists say.

“We have been told informally that the grant is not going to be funded,” said Matt Kaeberlein, the other director of the Dog Aging Project and a former biogerontology researcher at the University of Washington. (Dr. Kaeberlein is now the chief executive of Optispan, a health technology company.)

A spokeswoman for the National Institute on Aging said that the N.I.H. does not comment on the decision-making process for individual grant applications.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

September 1, 2015

15 Citizen Science Projects for Dog Lovers

You can help to advance studies of dog behavior

By Julie Hecht

Over the past few years public participation in science projects has surged, and research involving dogs is no exception. Often the work consists of online activities, but sometimes it requires participants to go into the world, do something and report back. Here's a list of online dog science projects that will be active through 2015 and that, in most cases, anyone in the world can join. All are in English at a minimum; a few are also bilingual.

Canid Howl Project

University of Tennessee and numerous institutions

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

http://howlcoder.appspot.com/HowlCoder.html

This project is trying to understand the range of canid vocalizations, involving primarily wolves, dogs and coyotes. Participants help by listening to vocalizations and analyzing the recordings. Ultimately the investigators hope to understand more about the social behavior of the entire range of canid species and breeds.

Canine Microbiome and Behavior Project

Human-Animal Interaction Lab, Oregon State University

www.thehumananimalbond.com/Microbiome.html

Did you know that the thing your dog does at least once a day can help researchers learn more about the relations among gut bacteria, health and behavior? The Oregon study aims to identify microbiome behavior that could help improve the life of dogs with certain physical or behavioral disorders. Researchers are seeking samples of your dog's stool, along with information on the dog's health and behavior.

Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Attachment Bond between Humans and Pet Dogs

www.thehumananimalbond.com/KutzlerAttachment

You may be able to help reveal similarities and differences in the attachments between pet dogs and their owners across cultures and environments. Researchers are seeking participants who are Latinos or non-Latinos living in the U.S. and Latinos living in Mexico.

Long-Term Dog Owners Survey

Animal Behaviour Cognition and Welfare Group, University of Lincoln, England

http://bit.do/longtermdog ownerssurvey

Have you lived with your dog for at least three years? Your answers to the survey will offer insight into the factors that lead people and dogs to stay companions over many years.

Dog Relinquishment Survey

http://bit.dodogrelinquishersurvey

Scientists lack a solid grasp of the factors that contribute to the reasons people sometimes give up their dogs. This judgment-free study aims to better understand the motivation. If you have voluntarily given up a dog for any reason to another individual, party or organization, this project would like to hear from you.

Dog Personality Survey

http://uoldogtemperament.co.uk/dogpersonality

The questions investigators have about dog personality are endless. This Web site features projects aiming to identify robust personality traits in dogs and to trace their biology from the level of genes through the brain to their behavior. By exploring common core traits in dogs, researchers can work to manage problems relating to these traits.

Dog Personality and Vocalization Project

Family Dog Project, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest

http://goo.gl/forms/ZDIXfDsr1M

Are there links among dog genetic profiles, personality and vocal behaviors? Help researchers by completing a short questionnaire about your dog's environment, personality and vocalizations. You can also elect to provide two additional pieces of information: conduct a short behavior test with your dog and report back on the result; send in a sample of your dog's saliva for DNA analysis.

Project: Your Dog, Inside and Out

http://goo.gl/forms/hGKC8tczcZ

Food hound? Activity seeker? Help researchers investigate the relation among activity level, feeding and body condition in dogs. If you like, you can add to the study of trait inheritance by (as with the previous project) providing a sample of your dog's saliva for DNA analysis.

Jealousy in Dogs

http://goo.gl/forms/3IWCBZguCe

You may have thought your dog is sometimes happy or angry, but how about jealous? The Family Dog Project questionnaire aims to gather details about jealousy in dogs, including the context in which it appears and the behaviors that express it. You can also choose to share a video in which you believe your dog is showing jealous behavior.

Is Your Dog Loud?

English: http://goo.gl/forms/1FzM07wpsR

German: http://goo.gl/forms/ye7wZnIEkD

Dutch: http://goo.gl/forms/hdCxW5GkxV

Italian: http://goo.gl/forms/6JKgpwMNzH

Spanish: http://goo.gl/forms/mlXoMre3ZH

Hungarian: http://goo.gl/forms/w1blAU2Pah

Does your dog growl, whine, bark, woof, cough or howl? Your dog's vocalizations are meaningful, and researchers want to hear all about them.

Emotional Content of Sounds

www.inflab.bme.hu/∼viktor/soundrating/index.html

What do you hear in these sounds? The project, with instructions in English and Hungarian, asks participants to listen to and rate different vocalizations on how arousing they think the vocalization is and whether it seems positive or negative.

Acoustic Engineering, University of Salford, England

www.sound101.org/woof/index.php

This project explores how people respond to dog barks. Scientists are trying to better understand how we react to everyday sounds.

Canine Behavior Assessment & Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ)

Center for the Interaction of Animals and Society, University of Pennsylvania

http://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq

C-BARQ is a questionnaire designed to provide dog owners and professionals with standardized evaluations of canine temperament and behavior. It has been extensively tested for reliability and validity on large samples of dogs of many breeds. C-BARQ data are used by numerous researchers around the world to investigate a variety of dog-related questions, such as those related to aggression, fear and trainability, among others. Live with a dog? Add to the dataset by telling C-BARQ.

Canines, Inc.

www.dognition.com

Participants can engage in different science-based games created by scientists, trainers and behavioral specialists. Dognition members can play the games with their dog and compare their dog's performance with that of other Dognition players. Membership requires a fee.

Co-Sleeping with Dogs

Clever Dog Lab, University of Veterinary Medicine, Messerli Research Institute, Vienna

English: https://goo.gl/5JPOzv

German: https://goo.gl/PFjaTK

Hungarian: https://goo.gl/3X8MHh

General Web site in German: www.iswf.at/de/projekte-publikationen

Whom do you hunker down with at night? The aim of this study is to find out more about the sleeping habits of owners and their pets, especially if you share the same bed or room (co-sleeping). Before you go to sleep tonight, consider completing this questionnaire.

Did you know that participants in dog studies tend to be women? Men should consider participating in such research, too. You could say that many canine studies are “looking for a few good men.”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Vet Sci

Dogs Supporting Human Health and Well-Being: A Biopsychosocial Approach

Nancy r. gee.

1 Department of Psychiatry, Center for Human Animal Interaction, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

Kerri E. Rodriguez

2 Human-Animal Bond in Colorado, School of Social Work, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States

Aubrey H. Fine

3 Department of Education, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA, United States

Janet P. Trammell

4 Division of Social Sciences and Natural Sciences, Seaver College, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, United States

Humans have long realized that dogs can be helpful, in a number of ways, to achieving important goals. This is evident from our earliest interactions involving the shared goal of avoiding predators and acquiring food, to our more recent inclusion of dogs in a variety of contexts including therapeutic and educational settings. This paper utilizes a longstanding theoretical framework- the biopsychosocial model- to contextualize the existing research on a broad spectrum of settings and populations in which dogs have been included as an adjunct or complementary therapy to improve some aspect of human health and well-being. A wide variety of evidence is considered within key topical areas including cognition, learning disorders, neurotypical and neurodiverse populations, mental and physical health, and disabilities. A dynamic version of the biopsychosocial model is used to organize and discuss the findings, to consider how possible mechanisms of action may impact overall human health and well-being, and to frame and guide future research questions and investigations.

Introduction – A Historical Perspective on Dog-Human Relationships

The modern relationship between humans and dogs is undoubtedly unique. With a shared evolutionary history spanning tens of thousands of years ( 1 ), dogs have filled a unique niche in our lives as man's best friend. Through the processes of domestication and natural selection, dogs have become adept at socializing with humans. For example, research suggests dogs are sensitive to our emotional states ( 2 ) as well as our social gestures ( 3 ), and they also can communicate with us using complex cues such as gaze alternation ( 4 ). In addition, dogs can form complex attachment relationships with humans that mirror that of infant-caregiver relationships ( 5 ).

In today's society, dog companionship is widely prevalent worldwide. In the United States, 63 million households have a pet dog, a majority of which consider their dog a member of their family ( 6 ). In addition to living in our homes, dogs have also become increasingly widespread in applications to assist individuals with disabilities as assistance dogs. During and following World War I, formal training of dogs as assistance animals began particularly for individuals with visual impairments in Germany and the United States ( 7 ). Following World War II, formal training for other roles, such as mobility and hearing assistance, started to increase in prevalence. Over the decades, the roles of assistance dogs have expanded to assist numerous disabilities and conditions including medical conditions such as epilepsy and diabetes and mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). At the same time, society has also seen increasing applications of dogs incorporated into working roles including detection, hunting, herding, and protection ( 8 , 9 ).

In addition to these working roles, dogs have also been instrumental in supporting humans in other therapeutic ways. In the early 1960s, animal-assisted interventions (AAI) began to evolve with the pioneering work of Boris Levinson, Elizabeth O'Leary Corson, and Samuel Corson. Levinson, a child psychologist practicing since the 1950s, noticed a child who was nonverbal and withdrawn during therapy began interacting with his dog, Jingles, in an unplanned interaction. This experience caused Levinson to begin his pioneering work in creating the foundations for AAI as an adjunct to treatment ( 10 ). In the 1970s, Samuel Corson and Elizabeth O'Leary Corson were some of the first researchers to empirically study canine-assisted interventions. Like Levinson, they inadvertently discovered that some of their patients with psychiatric disorders were interested in the dogs and that their patients with psychiatric disorders communicated more easily with each other and the staff when in the company of the dogs ( 11 , 12 ). Over the following decades, therapy dogs have been increasingly found to provide support for individuals with diverse needs in a wide array of settings ( 13 ).

Theoretical Framework for Dog Interaction Benefits

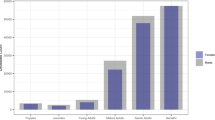

For over 40 years, the biopsychosocial model ( 14 ) has been widely used to conceptualize how biological, psychological, and social influences combine to determine human health and well-being. Biological influences refer to physiological changes such as blood pressure, cortisol, and heart rate, among others; psychological influences include personality, mood, and emotions, among others; and social influences refer to cultural, socio-economic, social relationships with others, family dynamics, and related matters. Figure 1 presents a graphical illustration of the relationship among these three influences in determining overall health and well-being. Although the model has dominated research and theory in health psychology for decades, more recently, it was re-envisioned as a more dynamic system ( 15 ) that construes human health as the result of the reciprocal influences of biological, psychological and social factors that unfold over personal and historical time. For example, if a person breaks his/her arm, there will be a biological impact in that immune and muscle systems respond and compensate. Social, or interpersonal, changes may occur when support or assistance is offered by others. Psychological changes will occur as a result of adjusting to and coping with the injury. Thus, the injury represents a dynamic influence initiated at one point in time and extending forward in time with diminishing impact as healing occurs.

A biopsychosocial perspective of how biological, psychological, and social influences may impact one another (solid lined arrows) and influence human health and well-being (represented here by the large thick circular shape).

This dynamic biopsychosocial approach to understanding health and well-being is appealing to the field of human-animal interaction (HAI) because of the dynamic nature of the relationship between humans and animals. For example, a person may acquire many dogs over his/her lifetime, perhaps from childhood to old age, and each of those dogs may sequentially develop from puppyhood to old age in that time. Behaviorally, the way the human and the dog interact is likely to be different across the lifespans of both species. From a biopsychosocial model perspective, the dynamic nature of the human-canine relationship may differentially interact with each of the three influencers (biological, psychological, and social) of human health and well-being over the trajectories of both beings. Notably, these influencers are not fixed, but rather have an interactional effect with each other over time.

While a person's biological, psychological, and social health may affect the relationship between that person and dogs with whom interactions occur, the focus of this manuscript is on the reverse: how owning or interacting with a dog may impact each of the psychological, biological, and social influencers of human health. We will also present relevant research and discuss potential mechanisms by which dogs may, or may not, contribute to human health and well-being according to the biopsychosocial model. Finally, we will emphasize how the biopsychosocial theory can be easily utilized to provide firmer theoretical foundations for future HAI research and applications to therapeutic practice and daily life.

Psychological Influences

Much research has been conducted on the impact of dog ownership and dog interactions on human psychological health and functioning. Frequent interactions with a dog, either through ownership or through long-term interventions, have been associated with positive psychological outcomes across the lifespan [for a systematic review of this evidence see ( 16 )]. One psychological aspect of interest to many HAI researchers is depression, especially among older adults. However, the relationship of pet dog ownership and depression over the lifespan continues to have inconsistent and inconclusive findings ( 16 ). Nevertheless, there are examples in the literature highlighting the beneficial role of dog ownership in reducing depression. As is frequently the case in HAI, the evidence from intervention studies is stronger than that of pet ownership studies ( 16 ), with the preponderance of this evidence linking animal-assisted interventions to a decrease in depression, as measured by self-report indices. Among the mechanisms for this reduction in depression are biological and social influences. For example, one such study found that an attachment relationship with a pet dog may serve as a coping resource for older women by buffering the relationship between loneliness (also measured by self-report indices) and depression, such that the presence of the pet dog appears to ameliorate the potential for loneliness to exacerbate depression ( 17 ). A causal relationship between dog ownership and mental health is difficult to determine. Not only may owning a pet dog increase stress, but those who are already suffering from loneliness or depression may be more inclined to have a pet dog than those who do not.

Another psychological outcome related to dog interaction that receives considerable research attention is anxiety. Studies have found that short-term, unstructured interactions with a therapy dog can significantly reduce self-reported anxiety and distress levels [e.g., ( 18 )]. For example, children with their pet dog or a therapy dog present during a stressful task exhibit lower perceived stress and more positive affect compared to when alone ( 19 ), when a parent was present ( 20 ), or when a stuffed dog was present ( 21 ). In addition to psychological mechanisms, there are social and biological mechanisms at play as well. In these short-term stressful contexts, a dog may serve as both a comforting, nonjudgmental presence as well as a positive tactile and sensory distraction. Dog interaction might also reduce anxiety and distress by influencing emotion regulation while coping with a stressor ( 22 ). During animal-assisted therapy, having a dog present during psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy can aid in decreasing self-reported anxious arousal and distress for patients who have experienced trauma, making the therapeutic treatment process more effective ( 23 ).

In addition to the negative aspects of psychological functioning, HAI research has also aimed to quantify the effects of dog interaction and ownership on positive psychological experiences such as happiness and well-being. Some studies have found that dog ownership is associated with higher life satisfaction and greater well-being ( 24 ), while other studies show that this is the case only when the dog provided social support ( 25 ) or satisfied the owner's needs ( 26 ). However, other large-scale surveys have found no significant differences in self-reported happiness between dog owners, cat owners, and non-pet owners ( 27 ), contributing to mixed findings. Recent discussions argue that too much focus has been placed on the relationship between mental health and the simple variable of dog ownership, when the specific activities that owners engage in with their dogs (e.g., walking, tactile interaction, and shared activities,) may be more important in explaining positive well-being ( 28 ). Further, many other factors may be driving these inconsistent findings in depression, anxiety, and well-being, including the owner's personality ( 24 ), gender and marital status ( 29 ), and attachment to the dog ( 30 ).

Dogs may also provide a source of motivation; for example, people with dogs are more likely to comply with the rigors of their daily life ( 31 ). The relationship with a pet dog may provide motivation to do things that may be less desirable. For example, for older adults who own pets, it is not uncommon for them to be more involved in daily life activities because of the need to take care of their animals ( 32 ). Likewise, children also complete less desired activities due to their relationship with the dog [for a discussion of this topic see ( 33 )].

An accumulation of research also suggests that dog interaction may have specific psychological benefits for individuals with physical disabilities and chronic conditions. Cohabitating with a specially trained assistance dog, including guide, hearing, and service dogs, can be associated with increased psychological and emotional functioning among individuals with disabilities ( 34 ). For individuals with mental disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), recent research has also found that having a psychiatric service dog is associated with fewer PTSD symptoms, less depression and anxiety, and better quality of life [For a review see ( 35 )]. These benefits appear to be due to a combination of the service dog's specific trained tasks and aspects inherent to cohabitating with a pet dog, including having a source of love, nonjudgmental social support, and companionship ( 36 ).

Similar research has also highlighted the value of dogs for children with disorders of executive functioning and self-regulation, especially autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). For some children with ASD, dogs may provide a calming and positive presence ( 37 ) and may both reduce anxiety ( 38 ) and improve problematic behaviors ( 39 ). Parents report that both pet dogs and service dogs can provide certain benefits for children with ASD, including benefits to children's moods, sleep, and behavior ( 40 , 41 ). Therapy dogs have also been found to be impactful in supporting children with ADHD in their emotional regulation ( 42 ) and aspects of character development ( 43 ). Nevertheless, the outcome of dog interactions may not be positive for all individuals with ASD and ADHD; despite evidence of psychological benefits of dog interaction for some children, others may be fearful or become over-stimulated by dogs ( 44 ).

In addition to impacts on psychological health, dog interaction can also impact psychological functioning, cognition, and learning. Among children, emerging research suggests short-term interactions with a therapy dog may lead to improvements in specific aspects of learning and cognition. A recent systematic review of research on therapy dog reading programs indicated that reading to a dog has a number of beneficial effects including improved reading performance ( 45 ). Studies suggest that interacting with a therapy dog may also improve speed and accuracy on cognitive (e.g., memory, categorization, adherence to instructions) and motor skills tasks among preschool-aged children compared to interacting with a stuffed dog or human ( 46 ). Similarly, a recent study showed that 10–14-year-old children had greater frontal lobe activity in the presence of a real dog as compared to a robotic dog, indicating a higher level of neuropsychological attention ( 47 ).

Among young adults, similar effects on cognition and learning have been found. Numerous colleges and universities now offer interactions with therapy dogs, typically during high stress times (such as before exams). In this sense, a biological mechanism through which dog interaction may positively impact cognition and learning is via stress reduction and improvement in positive affect. Even such short and infrequent interactions with therapy dogs may decrease perceived stress and increase perceived happiness in college students [e.g., ( 48 , 49 )]. Further, some institutions have permanent resident therapy dogs and/or long-term intervention programs; one such program showed that students who interacted with therapy dogs for 8 weeks reported significantly less homesickness and greater satisfaction with life than wait-listed controls ( 50 ). These effects may translate to additional effects on students' academic success, learning, and cognition. For instance, a recent randomized controlled trial ( 51 ) paired a standard academic stress management program with therapy dog interaction; the pairing produced significantly higher levels of self-reported enjoyment, usefulness, self-regulation, and behavior change than the stress management program or dog interaction alone. However, when therapy dog interaction is closely paired with more specific learning experiences, beneficial effects on stress remain, but benefits to academic performance may not manifest. For example, a recent study showed that interacting with a therapy dog resulted in significant improvements in students' perceived stress and mood, but not in actual exam scores ( 52 ). Similarly, interacting with a therapy dog during the learning and recall phase of a memory test did not improve memory compared to a control group ( 53 ). Taken together, dog interaction may improve stress and affect among college-aged adults as well as dimensions important for academic success and learning, but these results may or may not translate to cognitive performance benefits.

Biological Influences

The psychological and biological effects of HAI are often closely interwoven, as seen in the Psychological Influences section above and as demonstrated by the frequency with which psychological effects are evaluated using biological assessments of stress, anxiety, and arousal ( 54 ). For example, a plethora of studies have examined how short-term interactions with dogs can influence stress by measuring physiological biomarkers. Studies have found that dog interaction can influence parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, and electrodermal activity ( 55 ) as well as neurochemical indicators of affiliative behavior [e.g., beta-endorphins, prolactin, and dopamine; ( 56 )].

However, one of the most popular physiological measures in HAI research is the stress hormone cortisol ( 57 ). Studies have found that short-term interactions with a dog can decrease both subjective stress and circulating cortisol concentrations [e.g., ( 58 )]. Cohabitating with a dog has also been found to impact circulating cortisol after waking among children with ASD ( 39 ) and military veterans with PTSD ( 59 ). Experimental studies have also examined how having a dog present may modulate the stress response and cortisol secretion among individuals undergoing a stressful situation. Among adults, studies have found that having a dog present during a socially stressful paradigm can attenuate cortisol compared to when alone or with a human friend ( 60 ). A recent randomized controlled trial similarly found that interacting with a therapy dog, for 20 min, two times per week, over a 4-week period resulted in reduced cortisol (basal and diurnal measurement) among typically developing and special needs school children compared to the same duration and length of delivery for a yoga relaxation or a classroom as usual control group ( 61 ). However, it is of note that many methodologically rigorous studies have not found significant effects of interacting with a dog on physiological parameters, including salivary cortisol ( 21 , 62 , 63 ). A recent review of salivary bioscience research in human-animal interaction concluded that significant variation exists with regards to sampling paradigms, storage and assaying methods, and analytic strategies, contributing to variation in findings across the field ( 57 ).

As research quantifying the physiological outcomes from dog interaction continues to increase, so does research attempting to understand the underlying mechanisms of action leading to stress reduction. One theoretical rationale for dogs' stress-reducing benefits consists of the dog's ability to provide non-judgmental social support ( 60 ), improve positive affect ( 64 ), and provide a calming presence ( 22 ). Dogs may also contribute to a feeling of perceived safety and provide a tactile and grounding comfort ( 65 ). For these reasons, dogs are often incorporated into treatment and recovery for individuals who have experienced a traumatic event ( 66 ). Another mechanism contributing to these stress reducing benefits may be tactile stimulation and distraction derived from petting or stroking a dog. For example, Beetz et al. ( 67 ) found that the more time a child spent stroking the dog before a stressful task, the larger the magnitude of cortisol decrease. In fact, calming tactile interactions such as stroking, touching, and petting may be a key mechanism explaining animal-specific benefits to stress physiology, as touch is more socially appropriate in interactions with animals than as with other people ( 22 ). While there are many hypothesized mechanisms underlying positive psychophysiological change following human-dog interaction, more research is needed to determine how individual differences in humans, animals, and the human-animal relationship affects outcomes ( 21 , 57 , 62 , 63 ).

Another mechanism in which positive dog interaction may result in psychophysiological benefits is via the secretion of oxytocin. Oxytocin not only buffers the stress response and cortisol secretion ( 68 ) but is also involved emotion, trust, and bonding ( 69 ). The oxytocin system has been hypothesized to be a primary mechanistic pathway involved in human-dog interactions ( 70 ). Positive dog-owner interactions including stroking, petting, and talking have been shown to result in increased oxytocin levels in both dog owners and dogs, which has been related to the strength of the owner-dog relationship ( 71 ) and dog-human affiliative behaviors ( 72 , 73 ). Some studies have also found differential effects in oxytocin reactivity after dog interaction between human males and females ( 74 ), giving context to potential gender and/or hormonal differences in dog-human interactions. However, even though the oxytocin system exhibits potential as a pathway by which dogs provide psychophysiological benefits, it should be noted that mixed findings and methodological and measurement differences limit strong conclusions ( 75 ).

In regards to pet dog ownership, many studies have also sought to understand the biological effects of long-term interactions with a pet dog. Some research suggests that sharing animal-associated microbes with a pet dog can have long-term impacts on human health ( 76 ) while others have found that cohabitating with a pet dog can be beneficial for child allergies ( 77 ) and immune system development ( 78 ). However, most research on the long-term health impacts of pet dog ownership has focused on cardiovascular functioning. Epidemiological research suggests that dog ownership is linked to greater physical activity levels (presumably linked to dog-walking), and reduced risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality [for a summary see ( 79 )]. A recent meta-analysis of ten studies amassing data from over three million participants found that pet dog ownership was associated with a 31% risk reduction for mortality due to cardiovascular disease ( 80 ). However, dog ownership research of this nature will always suffer from an important chicken and egg type question: do dogs make us healthier, or do healthy people opt to own dogs?

Social Influences

A final way in which dog companionship and interaction may contribute to human health and well-being is through the social realm. Dogs may impact social functioning by providing direct social support ( 81 ) and a source of an attachment bond ( 82 ) which in turn may contribute to better social and mental health by providing companionship. Acquiring a pet dog has been reported to reduce both short-term and long-term self-reported loneliness ( 83 ). Particularly for those who live alone, dog ownership may serve as a protective factor against loneliness in times of social isolation, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic ( 84 ). Among older adults living in long-term care facilities or who live alone, dog visitation may also decrease loneliness by providing a source of meaningful companionship and social connectedness ( 85 , 86 ). However, the literature on pet dogs and loneliness is also characterized by mixed findings, raising the possibility that dog ownership may be a response to loneliness rather than protection from loneliness. Further, there remains a lack of high quality research in this area which limits any causal conclusions ( 87 ).

Another way in which the social support from a pet dog may benefit social functioning is by facilitating social interactions with others. For example, observational studies have found that being accompanied by a dog in public increases the frequency of received social interactions ( 88 ) and social acknowledgments [e.g., friendly glances, smiles; ( 89 )]. For those who engage in dog walking, social interactions are perceived as a rewarding side effect ( 90 ). Dogs can also provide a source of social capital, defined as the glue that holds society together ( 91 ). The research of Wood and colleagues ( 92 ) suggests that dogs can function as facilitators for social contact and interaction, with pet owners reporting higher perceptions of suburb friendliness and more social interactions with neighbors compared to non-pet owners.

For children and adolescents, pet dog ownership may contribute to healthy social development. Positive child–pet dog interactions have been shown to have benefits to children's social competence, interactions, and play behavior [for a review see ( 93 )]. Not only can children form attachment relationships with dogs ( 94 ), but pet dogs may promote feelings of safety and security ( 95 ) that can facilitate childhood social development. Pet ownership may also help children develop skills to form and maintain social relationships with their peers ( 96 ). For example, cross-sectional studies found that children with a pet dog in the home have fewer peer problems and have more prosocial behavior with children without a dog [e.g., ( 97 , 98 )].

Among children with developmental disorders, dog interaction has also been similarly shown to impact social functioning. For children with ADHD, two randomized controlled trials have found that 12 weeks of visits with a therapy dog, incorporated into curricula designed to improve skills and reduce behavioral problems, can result in improved social skills, prosocial behaviors, and perceptions of social competence ( 42 , 43 ). One potential explanation for these benefits is that children may interpret the dogs' nonverbal communication as less threatening and easier to interpret than human interaction ( 99 , 100 ). A recent eye-tracking study found that children with ASD exhibit a bias in social attention to animal faces, including dogs, compared to human faces ( 101 ). The presence of a dog in clinical applications may also promote more social engagement with a therapist while reducing negative behaviors ( 102 , 103 ). Further, there is some evidence that having a pet dog in the home can have a positive impact on social interactions of children with ASD, especially among verbal children, while teaching children responsibility and empathetic behavior ( 104 , 105 ).

Potential Mechanisms of Action

We have discussed how, in the psychological realm, interacting with a dog can positively relate to depression, anxiety, and well-being as well as psychological functioning in the areas of cognition, learning, and attention. It is interesting to note that most psychological constructs are measured using self-report indices, such as the Beck Depression Inventory ( 106 ) or the UCLA Loneliness Scale ( 107 ), while a smaller group of constructs are measured using speed and accuracy to detect targets (attention) or to remember information (learning and memory). In the biological realm, we discussed how interacting with dogs can influence stress-related physiological parameters and long-term biological and cardiovascular health. Biological measures are often recorded in real-time, such as heart rate or blood pressure, or are collected at critical time points during the study (e.g., saliva, urine, or blood samples for such measures as cortisol or oxytocin). Finally, we discussed the social realm, in which interacting with a dog can provide social support, facilitate social interactions, and improve social development and social skills. Measures used to assess variables in the social realm include self-report indices (e.g., demographics such as marital status, numbers of family members and friends), real time observations of social interactions (e.g., video analyses of interactions using ethograms), and parent/teacher reports of social functioning [e.g., Social Skills Rating System; ( 108 )]. To better understand and organize these various findings, we now consider potential mechanisms of action in the context of the biopsychosocial model, and as part of this discussion we will consider the potential for different types of measurement to have their own influence.

The mechanisms that underly positive human-dog interactions are likely to be interrelated and broadly, yet differentially, impactful across the three influencers of health (biological, psychological and social). According to the biopsychosocial model, impacts on one of the influencers of health is likely to impact the others ( 14 ). Further, an underlying mechanism of change may have a larger immediate impact on one realm than on the other two ( 15 ). Although this applies to the many influences we have discussed above, we will describe a reduction in stress as a more detailed example of how the biopsychosocial model can be considered. Stress is likely to have an immediate and measurable impact on the biological system through endocrinological (e.g., changes in cortisol) and psychophysiological (e.g., changes in blood pressure) processes. This same reduction in stress is likely to impact the psychological system through changes in mood or affect, concentration, and motivation, but that impact may not be immediately measurable or may be smaller in magnitude. This conjectured delay or reduction in effect size stems at least in part, from the way these changes are typically measured and the time course for potential effects to become measurable. For example, some biological changes indicative of increased stress (e.g., heart rate) can be measured in direct correspondence with the experimental manipulations (e.g., interacting with the dog vs. experiencing a control condition), and provide real time biological indications of changes in stress levels. Psychological indications of stress may be measured by a self-report survey instrument assessing state or trait anxiety. This type of measure cannot be completed in real time during the various experimental conditions (e.g., interacting with the dog vs. experiencing a control condition), but must be completed at some point following the experimental manipulation. It is possible that psychological measures are not as immediately sensitive to changes in the constructs they measure because of the required delay between manipulation and measurement. Such a delay may underestimate the real time effect as it may fade over time. Finally, reductions in stress have the potential to impact social systems by increasing social approaches and acceptance of approaches by others, but that impact may be of a small size or require even more time to be measurable. For example, exposure to stress may have immediate physiological effects, but it could take more time (prolonged exposure to stress) for those effects to impact some measures of social influence such as number of friends.

In Figure 2 , the mechanism of stress reduction is used as one example for the purposes of this discussion to exemplify how human-dog interactions may influence human health and well-being, as explained by the biopsychosocial model. Stress reduction may have a more immediate or larger impact on the biological realm as demonstrated by the larger arrow, while having a smaller (or perhaps delayed) impact on the psychological realm and an even smaller (or potentially more delayed) impact on the social realm.

An example of the potential for differential impact (represented by the different arrow thickness) of one mechanism of action (stress reduction) on the three realms of influence of overall health and well-being (depicted by the larger encompassing circle).