- Help & FAQ

Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature

- Department of Management

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › Research › peer-review

Since the concept of psychological safety was introduced, empirical research on its antecedents, outcomes, and moderators at different levels of analysis has proliferated. Given a burgeoning body of empirical evidence, a systematic review of the psychological safety literature is warranted. As well as reviewing empirical work on psychological safety, the present article highlights gaps in the literature and provides direction for future work. In doing so, it highlights the need to advance our understanding of psychological safety through the integration of key theoretical perspectives to explain how psychological safety develops and influences work outcomes at different levels of analysis. Suggestions for future empirical research to advance our understanding of psychological safety are also provided.

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 521-535 |

| Number of pages | 15 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 27 |

| Issue number | 3 |

| DOIs | |

| Publication status | Published - 1 Sept 2017 |

- Measurement issues

- Psychological safety

- Work outcomes

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Press/Media

Employee wellbeing: building a psychologically safe place for all.

30/11/18 → 11/11/19

2 items of Media coverage

Press/Media : Article/Feature

Human Resource Management Review Scholarly Impact Award Winner (2017-2022)

Newman, Alex (Recipient), Donohue, Ross (Recipient) & Eva, Nathan (Recipient), 2022

Prize : Other distinction

T1 - Psychological safety

T2 - A systematic review of the literature

AU - Newman, Alexander

AU - Donohue, Ross

AU - Eva, Nathan

PY - 2017/9/1

Y1 - 2017/9/1

N2 - Since the concept of psychological safety was introduced, empirical research on its antecedents, outcomes, and moderators at different levels of analysis has proliferated. Given a burgeoning body of empirical evidence, a systematic review of the psychological safety literature is warranted. As well as reviewing empirical work on psychological safety, the present article highlights gaps in the literature and provides direction for future work. In doing so, it highlights the need to advance our understanding of psychological safety through the integration of key theoretical perspectives to explain how psychological safety develops and influences work outcomes at different levels of analysis. Suggestions for future empirical research to advance our understanding of psychological safety are also provided.

AB - Since the concept of psychological safety was introduced, empirical research on its antecedents, outcomes, and moderators at different levels of analysis has proliferated. Given a burgeoning body of empirical evidence, a systematic review of the psychological safety literature is warranted. As well as reviewing empirical work on psychological safety, the present article highlights gaps in the literature and provides direction for future work. In doing so, it highlights the need to advance our understanding of psychological safety through the integration of key theoretical perspectives to explain how psychological safety develops and influences work outcomes at different levels of analysis. Suggestions for future empirical research to advance our understanding of psychological safety are also provided.

KW - Learning

KW - Measurement issues

KW - Psychological safety

KW - Work outcomes

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85009816141&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

DO - 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:85009816141

SN - 1053-4822

JO - Human Resource Management Review

JF - Human Resource Management Review

- Access through your organization

- Purchase PDF

- Patient Access

- Other access options

Article preview

Section snippets, references (40), cited by (2), education and clinical practice: special features psychological safety : what it is, why teams need it, and how to make it flourish, psychological safety: an overview, psychological safety in pccm: safety and quality, psychological safety for the administrator: strategies to foster psychological safety on teams, conclusions, financial/nonfinancial disclosures, psychological safety: a systematic review of the literature, hum res manag rev, psychological safety and infection prevention practices: results from a national survey, am j infect control, resilience vs. vulnerability: psychological safety and reporting of near misses with varying proximity to harm in radiation oncology, jt comm j qual patient saf, patient safety: break the silence, the fearless organization: creating psychological safety in the work place for learning, innovation, and growth, psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct, annu rev organ psychol organ behav, managing the risk of learning: psychological safety in work teams, what google learned from its quest to build the perfect team, the clinician as leader: why, how, and when, ann am thorac soc, understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: a comparative perspective, res hum dev, psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work, acad manage j, to err is human: building a safer health system, speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: a literature review, bmc health serv res, dissecting communication barriers in healthcare: a path to enhancing communication resiliency, reliability, and patient safety, j patient saf, psychological safety on the healthcare team, nurs manage, the presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: an evidence synthesis, behavioral integrity for safety, priority of safety, psychological safety, and patient safety: a team-level study, j appl psychol, making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams, j organ behav, the role of continuous quality improvement and psychological safety in predicting work-arounds, health care manage rev, managing routine exceptions: a model of nurse problem solving behavior, mistakes are not an option: aggression from peers and other correlates of anxiety and depression in pediatricians in training, second victim experience: a dynamic process conditioned by the environment. a qualitative research.

- Social Perception

- Developmental Psychology

- Psychological Safety

Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature

- January 2017

- Human Resource Management Review 27(3)

- Deakin University

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Monash University (Australia)

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

Article Contents

Introduction, methodology.

- < Previous

A systematic review of factors that enable psychological safety in healthcare teams

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Róisín O’donovan, Eilish Mcauliffe, A systematic review of factors that enable psychological safety in healthcare teams, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 32, Issue 4, May 2020, Pages 240–250, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa025

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The current systematic review will identify enablers of psychological safety within the literature in order to produce a comprehensive list of factors that enable psychological safety specific to healthcare teams.

A keyword search strategy was developed and used to search the following electronic databases PsycINFO, ABI/INFORM, Academic search complete and PubMed and grey literature databases OpenGrey, OCLC WorldCAT and Espace.

Peer-reviewed studies relevant to enablers of psychological safety in healthcare setting that were published between 1999 and 2019 were eligible for inclusion. Covidence, an online specialized systematic review website, was used to screen records. Data extraction, quality appraisal and narrative synthesis were conducted on identified papers.

Thirty-six relevant studies were identified for full review and data extraction. A data extraction template was developed and included sections for the study methodology and the specific enablers identified within each study.

Identified studies were reviewed using a narrative synthesis. Within the 36 articles reviewed, 13 enablers from across organizational, team and individual levels were identified. These enablers were grouped according to five broader themes: priority for patient safety, improvement or learning orientation, support, familiarity with colleagues, status, hierarchy and inclusiveness and individual differences.

This systematic review of psychological safety literature identifies a list of enablers of psychological safety within healthcare teams. This list can be used as a first step in developing observational measures and interventions to improve psychological safety in healthcare teams.

When teams are psychologically safe, they have a shared belief that they can take interpersonal risks, such as speaking up, asking questions and sharing ideas [ 1 ]. Psychological safety is associated with improved team learning [ 1 , 2 ], workplace creativity [ 3 , 4 ] and team performance [ 5–7 ]. These outcomes make psychological safety particularly important within high stakes work environments, such as healthcare organizations. Healthcare professionals must work interdependently, within a highly complex and dynamic work environment, to provide safe care for patients [ 3 , 8 ]. This makes psychological safety particularly vital within healthcare settings.

Despite the importance of psychological safety in healthcare teams, it is often lacking. Healthcare professionals are reluctant to speak up about concerns due to fear of retribution, not being listened to or not wanting to cause trouble [ 9–12 ]. There is an absence of interventions to improve psychological safety within healthcare teams and a lack of clear objective measures to understand when psychological safety is low and to track changes over time [ 13 ]. Previous research has established the benefits of improving psychological safety in healthcare teams, and it is now time to shift our focus to building interventions to do so. Identifying practical enablers of psychological safety within healthcare teams is an important first step in developing interventions to improve and maintain psychological safety.

Previous research has established that inclusive leadership behaviours, good interpersonal relationships and supportive organizational practices can promote psychological safety [ 5 , 6 , 14 , 15 ]. Previous systematic reviews have explored antecedents of psychological safety in a variety of workplace contexts [ 6 , 7 ]. Most recently, Newman and colleagues [ 5 ] examined antecedents of psychological safety, including, supportive leadership, organizational practices, relationship networks, team characteristics and individual differences. However, only 6 (13%) of these studies were conducted in a healthcare environment [ 2 , 8 , 16–19 ]. Aranzamendez et al. [ 15 ] identified leaders’ behaviour as a major antecedent to psychological safety in healthcare settings. While leadership plays an important role in psychological safety, it is but one dimension of a complex system of organizational-, team- and individual-level factors that may influence an individual’s sense of psychological safety. This study seeks to advance our understanding of the concept of psychological safety by taking a systems approach to identify the practical enablers of psychological safety in the healthcare environment. This list of practical enablers can inform the development of observational measures of psychological safety and interventions to improve psychological safety, which are tailored for use within healthcare teams.

The protocol for this review has been published on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42018107650).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed studies that identified enablers of psychological safety, speaking up or voice behaviour, within healthcare teams were included in this review. Included studies were experimental or observational research from any country carried between 1999 and 2019. The relevant studies were extracted from systematic literature reviews, and the reviews were excluded to avoid duplication of data. Studies were excluded if they were not available in English or if they were not conducted within a healthcare setting.

Search strategy

Keywords were identified through a scoping review of the literature and were grouped together using the OR Boolean term. The search strategy was reviewed by a researcher with extensive systematic review experience. The final search is presented in Table 1 .

Search strategies used

| Database . | Search string . |

|---|---|

| PsychInfo and ABI/INFORM | AB,TI(“Psychological safe ” OR “speak up” OR voic OR silen ) |

| PubMed | (((“Psychological safe ”[Title/Abstract] OR “speak up”[Title/Abstract] OR voic [Title/Abstract] OR silen [Title/Abstract])) AND (“1999/01/01”[PDat]: “2018/12/31”[PDat])) |

| Academic search complete search string | AB “Psychological safe ” OR “speak up” OR voic OR silen |

| Database . | Search string . |

|---|---|

| PsychInfo and ABI/INFORM | AB,TI(“Psychological safe ” OR “speak up” OR voic OR silen ) |

| PubMed | (((“Psychological safe ”[Title/Abstract] OR “speak up”[Title/Abstract] OR voic [Title/Abstract] OR silen [Title/Abstract])) AND (“1999/01/01”[PDat]: “2018/12/31”[PDat])) |

| Academic search complete search string | AB “Psychological safe ” OR “speak up” OR voic OR silen |

Information sources

Electronic databases were searched between 19 March 2018 and 8 June 2018 and were then updated between 10 July 2019 and 19 August 2019. The electronic databases searched were PsycINFO, ABI/INFORM, Academic search complete and PubMed. The grey literature databases searched were OpenGrey, OCLC WorldCAT and Espace (Curtin’s institutional repository). The authors also hand-searched the reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field to identify any further eligible studies.

Study screening

Covidence, an online specialized systematic review website, was used to screen studies. One reviewer screened record titles and abstracts based on the eligibility criteria. Two reviewers then independently reviewed the identified full-text studies. If there was any disagreement or ambiguity, a third reviewer assessed the relevant records, and consensus was reached on eligibility through discussion.

Data extraction process

A data extraction template was developed based on the guidelines produced by the Cochrane Public Health Group (see Table 2 ).

Data extraction template

| Review title or ID | |||||

| Author(s) | |||||

| Date published | |||||

| Date extraction completed | |||||

| Publication type | |||||

| Notes | |||||

| Methods | |||||

| Descriptions as stated in report/paper | Location in text | ||||

| Aim of study | |||||

| Design | |||||

| Participants | |||||

| Data collection | |||||

| Variables of interest | |||||

| Key findings | |||||

| Ethical approval needed/obtained for study | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Yes | No | Unclear | |||

| Notes: | |||||

| Enabler 1 | |||||

| Description | Location in text | ||||

| Description/definition | |||||

| Relationship to other enablers | |||||

| Other evidence | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| Review title or ID | |||||

| Author(s) | |||||

| Date published | |||||

| Date extraction completed | |||||

| Publication type | |||||

| Notes | |||||

| Methods | |||||

| Descriptions as stated in report/paper | Location in text | ||||

| Aim of study | |||||

| Design | |||||

| Participants | |||||

| Data collection | |||||

| Variables of interest | |||||

| Key findings | |||||

| Ethical approval needed/obtained for study | □ | □ | □ | ||

| Yes | No | Unclear | |||

| Notes: | |||||

| Enabler 1 | |||||

| Description | Location in text | ||||

| Description/definition | |||||

| Relationship to other enablers | |||||

| Other evidence | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

Quality assessment

Depending on the study design, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist, the CASP Cohort Study Checklist, the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies or the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to assess the quality of included studies.

Study synthesis

Identified studies were reviewed using a narrative synthesis [ 20 ]. The iterative steps outlined in Popay et al. [ 20 ] were followed: familiarization with studies and organizing then into logical categories, comparing and synthesizing studies, exploring relationships within and between the studies and synthesizing data under the relevant themes.

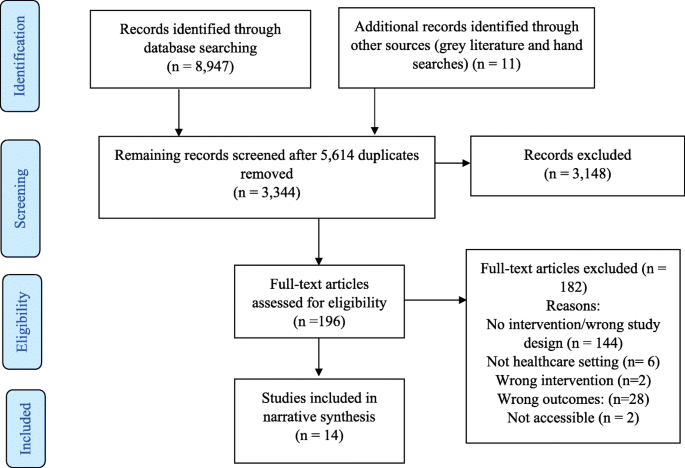

Thirty-six relevant studies were included for full review and data extraction. The PRISMA diagram included in Fig. 1 illustrates the full screening process. A summary of each article can be found in Table 3 . Table 4 presents the 13 enablers identified.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the inclusion and exclusion of identified studies.

The key themes identified in the literature are reported below.

Priority for patient safety

Thirteen studies suggested that a priority for patient safety can support psychological safety.

Safety culture . At the organizational level, studies identified safety culture as an enabler of psychological safety. Nurses’ with higher perceptions of safety climate also had higher psychological safety [ 21 ]. When hospitals have a safety culture, staff can speak up and discuss concerns openly [ 22–24 ]. Cultivating a safety culture among all healthcare professionals can help to make safe public spaces which can encourage newly graduated registered nurses to speak up [ 25 ].

Leader behavioural integrity for safety . Behavioural integrity is when leaders’ words and deeds relating to safety are in alignment. This signals to team members that their concern for safety is genuine and that it is safe to report errors. Leroy et al. [ 17 ] found that team psychological safety moderated the indirect relationship between leader behavioural integrity for safety and reported treatment error.

Professional responsibility . When healthcare professionals know that speaking up will result in meaningful change to patient safety, they are more likely to speak up [ 26 ]. Nursing staff have reported that their sense of responsibility and accountability for their patients motivated them to speak up to protect them, even when doing so was difficult or uncomfortable [ 10 , 24 , 27–31 ].

Summary of reviewed studies, sorted by year of publication

| Author . | Aims . | Participants . | Setting . | Enablers identified . | Methods of Evaluation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edmondson (2003) | Explore the impact of leader behaviours on speaking up within teams | 16 operating room teams | Hospital | Boundary spanning coaching leadership | Interviews: qualitative and quantitative data |

| Atwal and Caldwell (2005) | Record interactions of the team members using the Bales’ interaction process analysis | Healthcare professionals in two older persons multidisciplinary team meetings | Large acute NHS Trust | Hierarchy/status | Observations of meetings |

| Maxfield (2005) | Exploring concerns about communication that may contribute to avoidable errors and other problems in healthcare | 1700 nurses, physicians, clinical care and administrative staff | Urban, suburban and rural hospitals in the USA | Culture of safety | Focus groups, interviews, workplace observations and survey |

| Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) | Examine the relationship between status and psychological safety | 1440 healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, social workers, dieticians) | 23 neonatal intensive care units in the USA and Canada | Status Leader inclusiveness | Survey |

| Attree (2007) | Explore factors influencing nurses’ decisions to raise concerns | 142 nurses | Acute National Health Service (NHS) Trust in England | Professional responsibility Positive leadership | Survey |

| Dufresne (2007) | Explore the relationship between debriefing leaders, psychological safety and learning behaviours after critical incidents | 40 teams (227 resident anaesthesiologists) | Center for Medical Simulation in Cambridge | Positive leadership behaviours | Videotaped team debriefing |

| Halbesleben and Rathert (2008) | Examine continuous quality improvement and psychological safety in workarounds | 83 cancer registrars | Acute care hospitals in the USA | Continuous improvement | Survey |

| Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008) | Examine the cross-level effects of procedural justice climate on silence | 606 frontline hospital nurses from 30 workgroups | A large Midwestern hospital | Personal control | Survey |

| Carmeli and Zisu (2009) | Examine a three-pronged model of organizational trust, perceived organizational support and psychological safety | Employees who work in medical clinics and provide daily medical services | Large healthcare organization in Israel | Perceived organizational support | Survey |

| Rathert (2009) | Explore model linking the work environment to work engagement, organizational commitment, patient safety and psychological safety | 252 respondents: nurses (87%), allied health professionals (7%) and healthcare support personnel (6%) | Large metropolitan acute care hospital | Quality improvement and patient centred climate | Survey |

| Churchman and Doherty (2010) | Explore the extent to which nurses are willing to challenge doctors’ practice | 12 nurses | Acute NHS hospital in England | Supportive organization Status and hierarchy | Interviews |

| Adelman (2012) | Understanding CEO behaviours and actions that promote employee voice and upward communication in healthcare organizations | In each hospital, interviews took place with: the CEO, the Baldridge lead, a director and supervisor of a clinical service area and a frontline nurse | Four healthcare organizations who had received a performance award in the past 7 years | Leader: visibility, approachability, focus on continuous improvement, communication strategies | Document review and semi-structured interviews |

| Garon (2012) | Explore nurses’ perceptions of their own ability to speak up and be heard in the workplace | Staff registered nurses and managers | Magnet and non-magnet hospitals in California, USA | Experience and education organizational administration | Focus groups |

| Hirak (2012) | Investigate relationship between leader inclusiveness and psychological safety | 55 work unit leaders and a total of 224 unit members | Clinical units in a large hospital in Israel | Leader inclusiveness | Survey |

| Leroy (2012) | Explore how behavioural integrity for safety helps followers speak up | 54 nursing departments. An average of 11 nurses per department | Four Belgian hospitals | Leader behavioural integrity | Survey |

| Lyndon (2012) | Explore factors effecting whether clinicians to speak up about safety concerns | 125 obstetricians and registered nurses | Two moderately sized US labour and delivery units | Professional responsibility | Survey |

| Sayre (2012) | Evaluate intervention to develop speaking up behaviours among nurses | 58 (53 post-test) registered nurses in the intervention 87 (51 at post-test) in control group | Two acute care hospitals | Familiarity with leader | Survey list of individual nurse behaviours |

| Raes (2013) | Investigates when and how team engage in team learning behaviours | 28 divisional nursing teams | University hospital in Belgium | Transformational and laissez-faire leadership | Questionnaire |

| Ortega (2014) | Examine role of change-oriented leadership in learning process | 107 nursing teams ( = 689) from different hospital areas | 37 public hospitals in Spain | Change-oriented leadership | Survey |

| Schwappach and Gehring (2014) | Explore factors influencing voice or silence in oncology staff | 32 doctors and nurses from 7 oncology units | Six Swedish hospitals (seven oncology departments) | Professional responsibility Hierarchy/status | Interviews |

| Sundqvist and Carlsson (2014) | Describe advocacy in anaesthesia care during the perioperative phase | 112 registered nurse anaesthetists | Two hospitals in Sweden | Professional responsibility Experience | Interviews |

| Yanchus (2014) | Explore perceptions of communication in psychologically safe and unsafe environments | Clinical providers | USA veterans’ Health Administration | Communication Hierarchy/status Speaking up culture | Interviews and survey |

| Law and Chan (2015) | To explore the process of learning to speak up | Newly graduated registered nurses | Public hospital in Hong Kong | Speaking up training Mentoring Safety culture | Interviews Email conversation |

| Aydon (2016) | Identify factors influencing nurse’s decisions to question medication administration | 103 nurses | Neonatal care units in two public hospitals in Western Australia | Organizational support Professional responsibility Knowledge | Interviews |

| Jain (2016) | Examine psychological safety through a patient case study | Single case study and discussion | Cancer care teams | Hierarchy/status Familiarity Boundary spanning Inclusive leadership | Case study |

| O’Leary (2016) | Examine effective communication, shared decision-making and knowledge sharing | Teams of care providers ( = 24) and one client | Two private facilities for older people in Ireland | Leadership behaviour | Field notes Interviews Group discussion |

| Reese (2016) | Understand barriers facilitating factors of assertion communication | 6 focus group with 36 nurses, residents and attending physicians | 373 beds in academic children’s hospital | Hierarchy Familiarity | Focus group |

| Etchegaray (2017) | Examine association between willingness to speak up and perception teamwork and safety organizational cultures | Healthcare professionals with direct patient care responsibility | Large healthcare system in the USA | Leadership and cultural enablers | Survey: qualitative and quantitative |

| Martinez (2017) | Compare factors related to interns’ and residents’ speaking up about traditional versus professionalism safety threats | 1800 medical and surgical interns and residents (47% responded) | Across 6 US academic medical centres | Professional responsibility Leadership behaviour Peer support | Survey |

| Munn (2016) | Examine effect of safety climate, leader inclusiveness and psychological safety on nurses’ error reporting | Nurses ( = 814) Nurse manager ( = 43) | Large academic medical centre in the USA | Leadership Safety climate | Self-administrated surveys |

| Ng (2017) | Explore perceptions of communication openness communication issues and speaking up | 80 ICU staff members | Large public hospital in Hong Kong | Familiarity Hierarchy/status | Questionnaire and interviews |

| Weiss (2017) | Test the effects of inclusive leader language on voice | 40 anaesthesia nurses, 16 recovery room nurses, 52 resident anaesthesiologists and 18 attending anaesthesiologists ( = 126) | Hospital setting | Leader inclusiveness | Participants completed simulation exercise and questionnaire Behavioural coding and leader language analyses |

| Farh & Chen (2018) | Assess effect of leader behaviours and familiarity on voice | 118 surgical team performance episodes (or cases) randomly sampled | Five hospitals within a large hospital system | Coaching leadership Familiarity | Observer ratings Survey data |

| Omura (2018) | Explore nurses’ perceptions of assertive communication and identify facilitating or impeding factors | 23 Japanese registered nurses | Workplace or university in Japan | Supportive environment Positive relationships Effective role models Experience and knowledge Professional responsibility | Interviews |

| Albritton (2019) | Explore effectiveness of new quality improvement (QI) teams | 122 hospital-based QI teams | Hospitals in Ghana | Team leadership | Survey observer-rated measures |

| Alingh (2019) | Explore relationships between control-based and commitment-based safety management, safety climate, psychological safety and speaking up | 302 nurse managers and 2627 nurses from 334 clinical wards in Dutch hospitals | 84 Dutch hospitals | Leadership behaviour: commitment-based management | Survey |

| Author . | Aims . | Participants . | Setting . | Enablers identified . | Methods of Evaluation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edmondson (2003) | Explore the impact of leader behaviours on speaking up within teams | 16 operating room teams | Hospital | Boundary spanning coaching leadership | Interviews: qualitative and quantitative data |

| Atwal and Caldwell (2005) | Record interactions of the team members using the Bales’ interaction process analysis | Healthcare professionals in two older persons multidisciplinary team meetings | Large acute NHS Trust | Hierarchy/status | Observations of meetings |

| Maxfield (2005) | Exploring concerns about communication that may contribute to avoidable errors and other problems in healthcare | 1700 nurses, physicians, clinical care and administrative staff | Urban, suburban and rural hospitals in the USA | Culture of safety | Focus groups, interviews, workplace observations and survey |

| Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) | Examine the relationship between status and psychological safety | 1440 healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, social workers, dieticians) | 23 neonatal intensive care units in the USA and Canada | Status Leader inclusiveness | Survey |

| Attree (2007) | Explore factors influencing nurses’ decisions to raise concerns | 142 nurses | Acute National Health Service (NHS) Trust in England | Professional responsibility Positive leadership | Survey |

| Dufresne (2007) | Explore the relationship between debriefing leaders, psychological safety and learning behaviours after critical incidents | 40 teams (227 resident anaesthesiologists) | Center for Medical Simulation in Cambridge | Positive leadership behaviours | Videotaped team debriefing |

| Halbesleben and Rathert (2008) | Examine continuous quality improvement and psychological safety in workarounds | 83 cancer registrars | Acute care hospitals in the USA | Continuous improvement | Survey |

| Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008) | Examine the cross-level effects of procedural justice climate on silence | 606 frontline hospital nurses from 30 workgroups | A large Midwestern hospital | Personal control | Survey |

| Carmeli and Zisu (2009) | Examine a three-pronged model of organizational trust, perceived organizational support and psychological safety | Employees who work in medical clinics and provide daily medical services | Large healthcare organization in Israel | Perceived organizational support | Survey |

| Rathert (2009) | Explore model linking the work environment to work engagement, organizational commitment, patient safety and psychological safety | 252 respondents: nurses (87%), allied health professionals (7%) and healthcare support personnel (6%) | Large metropolitan acute care hospital | Quality improvement and patient centred climate | Survey |

| Churchman and Doherty (2010) | Explore the extent to which nurses are willing to challenge doctors’ practice | 12 nurses | Acute NHS hospital in England | Supportive organization Status and hierarchy | Interviews |

| Adelman (2012) | Understanding CEO behaviours and actions that promote employee voice and upward communication in healthcare organizations | In each hospital, interviews took place with: the CEO, the Baldridge lead, a director and supervisor of a clinical service area and a frontline nurse | Four healthcare organizations who had received a performance award in the past 7 years | Leader: visibility, approachability, focus on continuous improvement, communication strategies | Document review and semi-structured interviews |

| Garon (2012) | Explore nurses’ perceptions of their own ability to speak up and be heard in the workplace | Staff registered nurses and managers | Magnet and non-magnet hospitals in California, USA | Experience and education organizational administration | Focus groups |

| Hirak (2012) | Investigate relationship between leader inclusiveness and psychological safety | 55 work unit leaders and a total of 224 unit members | Clinical units in a large hospital in Israel | Leader inclusiveness | Survey |

| Leroy (2012) | Explore how behavioural integrity for safety helps followers speak up | 54 nursing departments. An average of 11 nurses per department | Four Belgian hospitals | Leader behavioural integrity | Survey |

| Lyndon (2012) | Explore factors effecting whether clinicians to speak up about safety concerns | 125 obstetricians and registered nurses | Two moderately sized US labour and delivery units | Professional responsibility | Survey |

| Sayre (2012) | Evaluate intervention to develop speaking up behaviours among nurses | 58 (53 post-test) registered nurses in the intervention 87 (51 at post-test) in control group | Two acute care hospitals | Familiarity with leader | Survey list of individual nurse behaviours |

| Raes (2013) | Investigates when and how team engage in team learning behaviours | 28 divisional nursing teams | University hospital in Belgium | Transformational and laissez-faire leadership | Questionnaire |

| Ortega (2014) | Examine role of change-oriented leadership in learning process | 107 nursing teams ( = 689) from different hospital areas | 37 public hospitals in Spain | Change-oriented leadership | Survey |

| Schwappach and Gehring (2014) | Explore factors influencing voice or silence in oncology staff | 32 doctors and nurses from 7 oncology units | Six Swedish hospitals (seven oncology departments) | Professional responsibility Hierarchy/status | Interviews |

| Sundqvist and Carlsson (2014) | Describe advocacy in anaesthesia care during the perioperative phase | 112 registered nurse anaesthetists | Two hospitals in Sweden | Professional responsibility Experience | Interviews |

| Yanchus (2014) | Explore perceptions of communication in psychologically safe and unsafe environments | Clinical providers | USA veterans’ Health Administration | Communication Hierarchy/status Speaking up culture | Interviews and survey |

| Law and Chan (2015) | To explore the process of learning to speak up | Newly graduated registered nurses | Public hospital in Hong Kong | Speaking up training Mentoring Safety culture | Interviews Email conversation |

| Aydon (2016) | Identify factors influencing nurse’s decisions to question medication administration | 103 nurses | Neonatal care units in two public hospitals in Western Australia | Organizational support Professional responsibility Knowledge | Interviews |

| Jain (2016) | Examine psychological safety through a patient case study | Single case study and discussion | Cancer care teams | Hierarchy/status Familiarity Boundary spanning Inclusive leadership | Case study |

| O’Leary (2016) | Examine effective communication, shared decision-making and knowledge sharing | Teams of care providers ( = 24) and one client | Two private facilities for older people in Ireland | Leadership behaviour | Field notes Interviews Group discussion |

| Reese (2016) | Understand barriers facilitating factors of assertion communication | 6 focus group with 36 nurses, residents and attending physicians | 373 beds in academic children’s hospital | Hierarchy Familiarity | Focus group |

| Etchegaray (2017) | Examine association between willingness to speak up and perception teamwork and safety organizational cultures | Healthcare professionals with direct patient care responsibility | Large healthcare system in the USA | Leadership and cultural enablers | Survey: qualitative and quantitative |

| Martinez (2017) | Compare factors related to interns’ and residents’ speaking up about traditional versus professionalism safety threats | 1800 medical and surgical interns and residents (47% responded) | Across 6 US academic medical centres | Professional responsibility Leadership behaviour Peer support | Survey |

| Munn (2016) | Examine effect of safety climate, leader inclusiveness and psychological safety on nurses’ error reporting | Nurses ( = 814) Nurse manager ( = 43) | Large academic medical centre in the USA | Leadership Safety climate | Self-administrated surveys |

| Ng (2017) | Explore perceptions of communication openness communication issues and speaking up | 80 ICU staff members | Large public hospital in Hong Kong | Familiarity Hierarchy/status | Questionnaire and interviews |

| Weiss (2017) | Test the effects of inclusive leader language on voice | 40 anaesthesia nurses, 16 recovery room nurses, 52 resident anaesthesiologists and 18 attending anaesthesiologists ( = 126) | Hospital setting | Leader inclusiveness | Participants completed simulation exercise and questionnaire Behavioural coding and leader language analyses |

| Farh & Chen (2018) | Assess effect of leader behaviours and familiarity on voice | 118 surgical team performance episodes (or cases) randomly sampled | Five hospitals within a large hospital system | Coaching leadership Familiarity | Observer ratings Survey data |

| Omura (2018) | Explore nurses’ perceptions of assertive communication and identify facilitating or impeding factors | 23 Japanese registered nurses | Workplace or university in Japan | Supportive environment Positive relationships Effective role models Experience and knowledge Professional responsibility | Interviews |

| Albritton (2019) | Explore effectiveness of new quality improvement (QI) teams | 122 hospital-based QI teams | Hospitals in Ghana | Team leadership | Survey observer-rated measures |

| Alingh (2019) | Explore relationships between control-based and commitment-based safety management, safety climate, psychological safety and speaking up | 302 nurse managers and 2627 nurses from 334 clinical wards in Dutch hospitals | 84 Dutch hospitals | Leadership behaviour: commitment-based management | Survey |

Enablers identified across levels of healthcare organizations

| Organizational . | Team . | Individual . |

|---|---|---|

| Safety culture | Leader behavioural integrity | Professional responsibility |

| Continuous improvement culture | Status, hierarchy and inclusiveness | Individual differences |

| Organizational support | Change-oriented leadership | |

| Familiarity across teams | Leader support | |

| Peer support | ||

| Familiarity leader | ||

| Familiarity team members |

| Organizational . | Team . | Individual . |

|---|---|---|

| Safety culture | Leader behavioural integrity | Professional responsibility |

| Continuous improvement culture | Status, hierarchy and inclusiveness | Individual differences |

| Organizational support | Change-oriented leadership | |

| Familiarity across teams | Leader support | |

| Peer support | ||

| Familiarity leader | ||

| Familiarity team members |

Improvement or learning orientation

Four studies highlighted the positive impact of a learning orientation on psychological safety.

A culture of continuous improvement . Care providers who reported greater continuous quality improvement environments also reported greater psychological safety [ 2 ]. Halbesleben and Rathert [ 19 ] found that psychological safety mediated the relationship between a climate for continuous quality improvement and staff engaging in experimentation and suggesting improvements to work processes.

Change-orientated leadership . Leaders play an important role in encouraging continuous quality improvement and psychological safety [ 19 , 32 ]. Change-oriented leaders enable psychological safety by encouraging innovative thinking, envisioning change, taking personal risks and facilitating open discussion of errors and solutions [ 19 ].

Seventeen studies explored the role of support in creating psychological safety.

Organizational support . Supportive healthcare environments have an open and respectful culture; raising concerns is a professional duty that is received positively and supported by administration and policies [ 10 , 27 , 28 , 33 ]. This promotes speaking up and assertive communication [ 24 , 27 ]. Healthcare professionals, who believe that their organization values their contribution and cares about their wellbeing, experience a higher level of psychological safety [ 34 ].

Support from leader . Predicted level of support from manager influences nurses’ decisions to raise concerns [ 10 ]. Transformational and commitment-based leaders, who are positive role models and prioritize patient safety, facilitate psychological safety and assertiveness [ 24 , 35 , 36 ]. Laissez-faire leadership encourages psychological safety by giving team members shared authority to make decisions and resolve problems [ 35 ]. However, more directive leadership, such as coaching, also facilitates psychological safety [ 37 , 38 ]. Leaders, who listen and provide feedback, facilitate open communication across healthcare organizations [ 28 , 32 , 39 ]. To foster psychological safety, leaders can use more advocacy statements and less negative evaluative statement [ 40 ] and recognize the impact they have on psychological safety within their team [ 41 ].

Support from peers . In psychologically safe teams, shared co-worker norms and values about speaking up influence team members’ willingness to speak up [ 39 ]. Having positive relationships, effective role models [ 24 ] and higher teamwork climates [ 23 , 26 ] can encourage assertive communication and speaking up for safety. Stronger workgroup identification reduces silence in nursing teams, once the procedural justice climate, the perception of organisational authorities as making fair decisions, was high [ 42 ].

Familiarity with colleagues

Familiarity with colleagues as an enabler of psychological safety was mentioned by six studies.

Familiarity between team members . Familiarity and face-to-face communication between team members facilitates psychological safety [ 43 ]. To leverage the expertise of specialists who work in different areas, geographically dispersed teams are often required in healthcare. This reduces the direct communication needed to develop psychological safety [ 44 ]. Similarly, when new members are constantly joining the team, building and maintaining psychological safety becomes challenging [ 45 ]. Having a stable core team membership facilitates the development of trusting interpersonal relations and team psychological safety [ 45 ].

Familiarity across teams . Due to the complex and interdependent nature of healthcare teams, there is a growing need to communicate and collaborate across different teams. Boundary spanners are members of the team who integrate the work of other teams in order to facilitate communication and information sharing [ 38 ]. Both Edmondson [ 38 ] and Jain et al. [ 44 ] found a positive association between boundary spanning and team psychological safety.

Familiarity with team leaders . Hospital leaders who are visible and present on a regular basis promote employee voice [ 32 ]. This visibility creates familiarity between employees and their leader allowing trusting relationships to develop. Sayre et al. [ 46 ] created more leader visibility in order to improve speaking up behaviours among registered nurses.

Status, hierarchy and inclusiveness

Healthcare professionals find it easier to challenge those who have less experience than them [ 24 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 47 , 31 ]. Those with higher status report higher levels of psychological safety [ 29 , 43 , 44 , 48 ], while those lower in the hierarchy perceive a knowledge gap between themselves and their superiors and are less likely to assert themselves [ 29 , 43 , 48 ].

Inclusive leadership behaviours help to overcome the negative effects of low status on psychological safety by flattening hierarchical differences [ 8 , 16 , 21 , 32 , 23 , 45 , 49 ]. Inclusive leadership is when leaders’ words and deeds invite and appreciate their contributions and feedback from all team members [ 8 ]. In interventions to improve psychological safety, implicit inclusive leader language, such as ‘we’, ‘us’ or ‘our’, improved voice behaviour [ 49 ] and inclusive leadership behaviours helped to develop team psychological safety [ 45 ].

Individual differences . Individual differences can also enable psychological safety in healthcare teams. Three studies found that gender influences psychological safety. Females have a lower rate per minute of asking and giving opinions [ 48 ], while males are more likely to speak up about professionalism safety issues [ 26 ]. Personality also influences healthcare professionals’ likelihood of speaking up. Registered nurses and obstetricians were more inclined to speak up when they had higher bravery and assertiveness scores [ 30 ]. Courage was associated with speaking up among medical and surgical interns and residents [ 26 ]. Similarly, nurses perceive speaking up as a behaviour requiring bravery and courage [ 25 , 29 ].

Tangirala and Ramanujam [ 42 ] found that personal control positively affected the speaking up behaviour of nurses. This relationship was U-shaped meaning that when personal control was either high or low, there were higher levels of voice behaviour. This relationship was moderated by organisational identification, with those who had high levels of personal control and stronger identification having higher use of voice.

This review identified 13 enablers of psychological safety within healthcare contexts. Four were at the organizational level, seven were at the team level and two were at the individual level (see Table 4 ). These findings concur with previous research [ 5 , 6 , 14 , 15 ]. While this review has not identified any novel enablers of psychological safety, it adds value to previous research by adopting a systems lens to identify a comprehensive list of factors at organization, team and individual levels that enable psychological safety within healthcare teams. The review was driven by a desire to shift the focus from understanding the antecedents of psychological safety, to thinking more about how to enable and improve psychological safety in teams. We grouped our findings into five broad categories: priority for patient safety, improvement or learning orientation, support, familiarity with colleagues and status, hierarchy and inclusiveness and individual differences.

The category ‘priority for patient safety’ reflects this reviews’ specific focus on the healthcare environment. There is an important bidirectional relationship between psychological safety and safety culture, while a safety culture improves psychological safety in healthcare teams, psychologically safe healthcare professionals also become more engaged in behaviours that improve safety cultures [ 6 , 8 , 14 ]. Leader’s behavioural integrity for safety promotes psychological safety in healthcare teams, as well as improves overall safety culture within these teams [ 2 , 8 ]. These findings highlight that having a priority for safety can cultivate both a safe environment for patients and high psychological safety among staff.

When healthcare organizations have a climate of continuous improvement, it supports the development of psychological safety and encourages staff to become more engaged in improving team or organizational practices. At the team level, change-oriented leaders play a key role in enabling psychological safety by role modelling innovative thinking, taking interpersonal risks and discussing errors.

Support from organizations, leaders and peers all encourage psychological safety within healthcare settings. This can also be seen outside of the healthcare context [ 5 , 50 ]. Leader visibility can promote familiarity with their team members and is also an opportunity for leaders to role model supportive behaviours which cultivate psychological safety. While the familiarity that results from face-to-face contact and stable team membership facilitates psychological safety, creating these circumstances can be challenging within a complex and rapidly changing healthcare environment [ 3 , 8 , 44 ]. Healthcare teams need to engage in the active process of ‘teaming’, which occurs when diverse employees are brought together as needs demand and are then disbanded once the need has been addressed [ 51 ]. While teaming allows organizations to adapt to chaotic environments, it reduces the time teams have to develop familiarity and psychological safety. It is necessary to develop psychological safety alongside teaming in order for healthcare professionals to adapt to the demands of increasingly complex patient care [ 52 ]. The other enablers of psychological safety identified in this review, such as priority for safety, may be used in order to compensate for any lack of familiarity within and across healthcare teams.

Similar to the aviation industry [ 53 ], team members with high status, and more knowledge and experience, are more likely to feel psychologically safe. When staff are less experienced and have a lower status, inclusive leadership can support them to feel more psychologically safe. Although, psychological safety has been defined as a group level phenomenon [ 1 ], it is influenced by healthcare professionals’ individual differences such as gender, personality traits and individuals’ perceptions of personal control.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review presents factors which enable psychological safety within healthcare teams. While the enablers identified are not novel, this review takes a systems approach to develop a comprehensive list of practical enablers of psychological safety in the healthcare environment. This list can be applied to the development of more objective measures of psychological safety and interventions targeted at improving psychological safety in healthcare teams. To minimize the risk of publication bias, searches were conducted on academic and grey literature databases as well as through contacting experts.

Practical implications and future research

The list of practical enablers presented in this review aid the future development of objective measures of psychological safety and interventions to improve psychological safety within healthcare teams. Despite the important role played by psychologically safe healthcare teams, a culture of fear still exists [ 11 , 12 , 14 , 38 ]. There is a lack of guidance on how healthcare teams can improve and maintain psychological safety and, therefore, a need to develop and implement interventions to improve psychological safety within these teams [ 13 ]. The enablers of psychological safety presented in this review are a useful starting point for developing the necessary components of these interventions. It is recommended that future research draw on the enablers outlined by this review in order to develop effective interventions to improve psychological safety. Ensuring that future interventions focus on developing a priority for safety may be of particular importance to improving psychological safety in healthcare organizations. By incorporating intervention components that target the development of enablers of psychological safety, future interventions are more likely to be successful.

In order to understand whether an intervention is successful in improving psychological safety, there is a need for objective outcome measures. To date, most studies have relied on self-report survey measures which can be limited by self-report bias and response fatigue [ 5 , 54 ]. Therefore, there is a need for reliable objective measures of psychological safety, such as observational measures, which can offer a more holistic understanding of changes in psychological safety over time [ 5 , 13 ]. Understanding the enablers of psychological safety is necessary in order to develop these observational measures. Future research is needed in order to incorporate enablers of psychological safety into objective measures of psychological safety. By building on this review, future research can identify observable behaviours associated with the enablers of psychological safety in healthcare teams and include them as part of an observational measure of psychological safety.

The current systematic review identifies a list of enablers of psychological safety within healthcare teams. These findings provide a starting point for future research to develop objective measures and interventions to improve psychological safety within healthcare teams.

This work was supported by the Irish Research Council.

Edmondson A . Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams Amy Edmondson . Adm Sci Q 1999 ; 44 : 350 – 83 .

Google Scholar

Rathert C , Ishqaidef G , May DR . Improving work environments in health care: test of a theoretical framework . Health Care Manag Rev 2009 ; 34 : 334 – 43 .

Kessel M , Kratzer J , Schultz C . Psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and creative performance in healthcare teams . Creat Innov Manag 2012 ; 21 : 147 – 57 .

Lee YSH . Fostering creativity to improve health care quality. Unpublished doctoral dissertation . New Haven, Connecticut : Yale University 2017 .

Google Preview

Newman A , Donohue R , Eva N . Psychological safety: a systematic review of the literature . Hum Resour Manag Rev 2017 ; 27 : 521 – 35 .

Edmondson AC , Lei Z . Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct . Annu Rev Organ Psych Organ Behav 2014 ; 1 : 23 – 43 .

Singer S , Edmondson A . Confronting the tension between learning and performance . Refl: Syst Think 2012 ; 11 : 34 – 43 .

Nembhard IM , Edmondson AC . Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams . J Organ Behav 2006 ; 27 : 941 – 66 .

Maxfield D , Grenny J , Lavandero R et al. The Silent Treatment: Why Safety Tools and Checklists Aren’t Enough . Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare , 2011 . Available at: https://faculty.medicine.umich.edu/sites/default/files/resources/silent_treatment.pdf .

Attree M . Factors influencing nurses’ decisions to raise concerns about care quality . J Nurs Manag 2007 ; 15 : 392 – 402 .

Moore L , McAuliffe E . Is inadequate response to whistleblowing perpetuating a culture of silence in hospitals? Clin Govern Int J 2010 ; 15 : 166 – 78 .

Moore L , McAuliffe E . To report or not to report? Why some nurses are reluctant to whistleblow . Clin Govern Int J 2012 ; 17 : 332 – 42 .

O’Donovan R , McAuliffe E . A systematic review exploring the content and outcomes of interventions to improve psychological safety, speaking up and voice behaviour . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 1 – 11 .

Appelbaum NP , Dow A , Mazmanian PE et al. The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting . Med Educ 2016 ; 50 : 343 – 50 .

Aranzamendez G , James D , Toms R . Finding antecedents of psychological safety: a step toward quality improvement . Nurs Forum 2015 ; 50 : 171 – 8 .

Hirak R , Peng AC , Carmeli A et al. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures . Leadersh Q 2012 ; 23 : 107 – 17 .

Leroy H , Dierynck B , Anseel F et al. Behavioral integrity for safety, priority of safety, psychological safety, and patient safety: a team-level study . J Appl Psychol 2012 ; 97 : 1273 – 81 .

Ortega A , Van den Bossche P , Sánchez-Manzanares M et al. The influence of change-oriented leadership and psychological safety on team learning in healthcare teams . J Bus Psychol 2014 ; 29 : 311 – 21 .

Halbesleben JR , Rathert C . The role of continuous quality improvement and psychological safety in predicting work-arounds . Health Care Manag Rev 2008 ; 33 : 134 – 44 .

Popay J , Roberts H , Sowden A et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme, Version 1 , 2006 , b92 .

Munn LT . Team dynamics and learning behavior in hospitals: a study of error reporting by nurses . Unpublished Doctoral dissertation . Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina 2016 .

Maxfield D . Silence Kills: The Seven Crucial Conversations for Healthcare . Provo, UT : VitalSmarts , 2005 .

Etchegaray JM , Ottosen MJ , Dancsak T et al. Barriers to speaking up about patient safety concerns . J Patient Saf 2017 , doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000334 .

Omura M , Stone TE , Maguire J et al. Exploring Japanese nurses' perceptions of the relevance and use of assertive communication in healthcare: a qualitative study informed by the theory of planned behaviour . Nurse Educ Today 2018 ; 67 : 100 – 7 .

Law BYS , Chan EA . The experience of learning to speak up: a narrative inquiry on newly graduated registered nurses . J Clin Nurs 2015 ; 24 : 1837 – 48 .

Martinez W , Etchegaray JM , Thomas EJ et al. Speaking up about patient safety concerns and unprofessional behaviour among residents: validation of two scales . BMJ Qual Saf 2015 ; 24 : 671 – 80 .

Aydon L , Hauck Y , Zimmer M et al. Factors influencing a nurse's decision to question medication administration in a neonatal clinical care unit . J Clin Nurs 2016 ; 25 : 2468 – 77 .

Garon M . Speaking up, being heard: registered nurses’ perceptions of workplace communication . J Nurs Manag 2012 ; 20 : 361 – 71 .

Schwappach DL , Gehring K . Trade-offs between voice and silence: a qualitative exploration of oncology staff’s decisions to speak up about safety concerns . BMC Health Serv Res 2014 ; 14 : 303 .

Lyndon A , Sexton JB , Simpson KR et al. Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery . BMJ Qual Saf 2012 ; 21 : 791 – 9 .

Sundqvist AS , Carlsson AA . Holding the patient's life in my hands: Swedish registered nurse anaesthetists' perspective of advocacy . Scand J Caring Sci 2014 ; 28 : 281 – 8 .

Adelman K . Promoting employee voice and upward communication in healthcare: the CEO’s influence . J Healthc Manag 2012 ; 57 : 133 – 48 .

Churchman JJ , Doherty C . Nurses’ views on challenging doctors’ practice in an acute hospital . Nurs Stand 2010 ; 24 : 42 – 8 .

Carmeli A , Zisu M . The relational underpinnings of quality internal auditing in medical clinics in Israel . Soc Sci Med 2009 ; 68 : 894 – 902 .

Raes E , Decuyper S , Lismont B et al. Facilitating team learning through transformational leadership . Instr Sci 2013 ; 41 : 287 – 305 .

Alingh CW , van Wijngaarden JD , van de Voorde K et al. Speaking up about patient safety concerns: the influence of safety management approaches and climate on nurses’ willingness to speak up . BMJ Qual Saf 2019 ; 28 : 39 – 48 .

Farh CI , Chen G . Leadership and member voice in action teams: test of a dynamic phase model . J Appl Psychol 2018 ; 103 : 97 – 110 .

Edmondson AC , Woolley AW . Understanding outcomes of organizational learning interventions. In: International Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management . London : Blackwell , 2003 , 185 – 211 .

Yanchus NJ , Derickson R , Moore SC et al. Communication and psychological safety in veterans health administration work environments . J Health Organ Manag 2014 ; 28 : 754 – 76 .

Dufresne RL . Learning from critical incidents by ad hoc teams: The impacts of team debriefing leader behaviors and psychological safety . Dissertations and Theses . Boston College 2007 .

Albritton JA , Fried B , Singh K et al. The role of psychological safety and learning behavior in the development of effective quality improvement teams in Ghana: an observational study . BMC Health Serv Res 2019 ; 19 : 385 .

Tangirala S , Ramanujam R . Exploring nonlinearity in employee voice: the effects of personal control and organizational identification . Acad Manag J 2008 ; 51 : 1189 – 203 .

Reese J , Simmons R , Barnard J . Assertion practices and beliefs among nurses and physicians on an inpatient pediatric medical unit . Hosp Pediatr 2016 ; 6 : 275 – 81 .

Jain AK , Fennell ML , Chagpar AB et al. Moving toward improved teamwork in cancer care: the role of psychological safety in team communication . J Oncol Pract 2016 ; 12 : 1000 – 11 .

O’Leary DF . Exploring the importance of team psychological safety in the development of two interprofessional teams . J Interprof Care 2016 ; 30 : 29 – 34 .

Sayre MM , McNeese-Smith D , Leach LS et al. An educational intervention to increase “speaking-up” behaviors in nurses and improve patient safety . J Nurs Care Qual 2012 ; 27 : 154 – 60 .

Ng GWY , Pun JKH , So EHK et al. Speak-up culture in an intensive care unit in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional survey exploring the communication openness perceptions of Chinese doctors and nurses . BMJ Open 2017 ; 7 : e015721 .

Atwal A , Caldwell K . Do all health and social care professionals interact equally: a study of interactions in multidisciplinary teams in the United Kingdom . Scand J Caring Sci 2005 ; 19 : 268 – 73 .

Weiss M , Kolbe M , Grote G et al. We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams . Leadersh Q 2018 ; 29 : 389 – 402 .

May DR , Gilson RL , Harter LM . The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work . J Occup Organ Psychol 2004 ; 77 : 11 – 37 .

Edmondson AC . Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy . San Francisco : John Wiley & Sons , 2012 .

Nawaz H , Edmondson AC , Tzeng TH et al. Teaming: an approach to the growing complexities in health care AOA critical issues . J Bone Joint Surg 2014 ; 96 : 1 – 7 .

Bienefeld N , Grote G . Speaking up in ad hoc multiteam systems: individual-level effects of psychological safety, status, and leadership within and across teams . Eur J Work Organ Psy 2014 ; 23 : 930 – 45 .

Donaldson SI , Grant-Vallone EJ . Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research . J Bus Psychol 2002 ; 17 : 245 – 60 .

- patient care team

- patient safety

- health care safety

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2020 | 3 |

| April 2020 | 116 |

| May 2020 | 59 |

| June 2020 | 197 |

| July 2020 | 168 |

| August 2020 | 195 |

| September 2020 | 830 |

| October 2020 | 199 |

| November 2020 | 89 |

| December 2020 | 78 |

| January 2021 | 171 |

| February 2021 | 328 |

| March 2021 | 394 |

| April 2021 | 506 |

| May 2021 | 358 |

| June 2021 | 389 |

| July 2021 | 268 |

| August 2021 | 170 |

| September 2021 | 156 |

| October 2021 | 365 |

| November 2021 | 584 |

| December 2021 | 496 |

| January 2022 | 604 |

| February 2022 | 601 |

| March 2022 | 659 |

| April 2022 | 658 |

| May 2022 | 651 |

| June 2022 | 637 |

| July 2022 | 519 |

| August 2022 | 651 |

| September 2022 | 671 |

| October 2022 | 850 |

| November 2022 | 823 |

| December 2022 | 754 |

| January 2023 | 805 |

| February 2023 | 912 |

| March 2023 | 1,262 |

| April 2023 | 1,026 |

| May 2023 | 900 |

| June 2023 | 700 |

| July 2023 | 983 |

| August 2023 | 774 |

| September 2023 | 909 |

| October 2023 | 1,258 |

| November 2023 | 1,026 |

| December 2023 | 836 |

| January 2024 | 1,125 |

| February 2024 | 1,273 |

| March 2024 | 1,341 |

| April 2024 | 1,385 |

| May 2024 | 1,456 |

| June 2024 | 1,096 |

| July 2024 | 1,252 |

| August 2024 | 896 |

| September 2024 | 938 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior

Volume 1, 2014, review article, psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct.

- Amy C. Edmondson 1 , and Zhike Lei 2

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts 02163; email: [email protected] 2 European School of Management and Technology (ESMT), 10178 Berlin, Germany

- Vol. 1:23-43 (Volume publication date March 2014) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- First published as a Review in Advance on January 10, 2014

- © Annual Reviews

Psychological safety describes people’s perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a particular context such as a workplace. First explored by pioneering organizational scholars in the 1960s, psychological safety experienced a renaissance starting in the 1990s and continuing to the present. Organizational research has identified psychological safety as a critical factor in understanding phenomena such as voice, teamwork, team learning, and organizational learning. A growing body of conceptual and empirical work has focused on understanding the nature of psychological safety, identifying factors that contribute to it, and examining its implications for individuals, teams, and organizations. In this article, we review and integrate this literature and suggest directions for future research. We first briefly review the early history of psychological safety research and then examine contemporary research at the individual, group, and organizational levels of analysis. We assess what has been learned and discuss suggestions for future theoretical development and methodological approaches for organizational behavior research on this important interpersonal construct.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences, self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science, burnout and work engagement: the jd–r approach, employee voice and silence, psychological capital: an evidence-based positive approach, how technology is changing work and organizations, research on workplace creativity: a review and redirection, abusive supervision, alternative work arrangements: two images of the new world of work.

Publication Date: 21 Mar 2014

Online Option

Sign in to access your institutional or personal subscription or get immediate access to your online copy - available in PDF and ePub formats

Psychological Safety Comes of Age: Observed Themes in an Established Literature

Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, Vol. 10, Issue 1, pp. 55-78, 2023

Posted: 2 Feb 2023

Amy C. Edmondson

Harvard University

Derrick P. Bransby

Date Written: January 2023

Since its renaissance in the 1990s, psychological safety research has flourished—a boom motivated by recognition of the challenge of navigating uncertainty and change. Today, its theoretical and practical significance is amplified by the increasingly complex and interdependent nature of the work in organizations. Conceptual and empirical research on psychological safety—a state of reduced interpersonal risk—is thus timely, relevant, and extensive. In this article, we review contemporary psychological safety research by describing its various content areas, assessing what has been learned in recent years, and suggesting directions for future research. We identify four dominant themes relating to psychological safety: getting things done, learning behaviors, improving the work experience, and leadership. Overall, psychological safety plays important roles in enabling organizations to learn and perform in dynamic environments, becoming particularly relevant in a world altered by a global pandemic.

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Amy C. Edmondson (Contact Author)

Harvard university ( email ), do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, annual review of organizational psychology & organizational behavior.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A systematic review of factors that enable psychological safety in healthcare teams

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Midwifery & Health Systems, Health Sciences Centre, University College Dublin, Dublin 4, Ireland.

- PMID: 32232323

- DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa025

Purpose: The current systematic review will identify enablers of psychological safety within the literature in order to produce a comprehensive list of factors that enable psychological safety specific to healthcare teams.

Data sources: A keyword search strategy was developed and used to search the following electronic databases PsycINFO, ABI/INFORM, Academic search complete and PubMed and grey literature databases OpenGrey, OCLC WorldCAT and Espace.

Study selection: Peer-reviewed studies relevant to enablers of psychological safety in healthcare setting that were published between 1999 and 2019 were eligible for inclusion. Covidence, an online specialized systematic review website, was used to screen records. Data extraction, quality appraisal and narrative synthesis were conducted on identified papers.

Data extraction: Thirty-six relevant studies were identified for full review and data extraction. A data extraction template was developed and included sections for the study methodology and the specific enablers identified within each study.

Results of data synthesis: Identified studies were reviewed using a narrative synthesis. Within the 36 articles reviewed, 13 enablers from across organizational, team and individual levels were identified. These enablers were grouped according to five broader themes: priority for patient safety, improvement or learning orientation, support, familiarity with colleagues, status, hierarchy and inclusiveness and individual differences.

Conclusion: This systematic review of psychological safety literature identifies a list of enablers of psychological safety within healthcare teams. This list can be used as a first step in developing observational measures and interventions to improve psychological safety in healthcare teams.

Keywords: Enablers; Healthcare teams; Psychological safety.

© The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press in association with the International Society for Quality in Health Care. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected].

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- A systematic review exploring the content and outcomes of interventions to improve psychological safety, speaking up and voice behaviour. O'Donovan R, McAuliffe E. O'Donovan R, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Feb 10;20(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4931-2. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020. PMID: 32041595 Free PMC article.

- Health professionals' experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Eddy K, Jordan Z, Stephenson M. Eddy K, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016 Apr;14(4):96-137. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-1843. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016. PMID: 27532314 Review.

- The measurement of collaboration within healthcare settings: a systematic review of measurement properties of instruments. Walters SJ, Stern C, Robertson-Malt S. Walters SJ, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016 Apr;14(4):138-97. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2159. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016. PMID: 27532315 Review.

- Measuring psychological safety in healthcare teams: developing an observational measure to complement survey methods. O'Donovan R, Van Dun D, McAuliffe E. O'Donovan R, et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020 Jul 29;20(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01066-z. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020. PMID: 32727374 Free PMC article.

- Team interventions in acute hospital contexts: a systematic search of the literature using realist synthesis. Cunningham U, Ward ME, De Brún A, McAuliffe E. Cunningham U, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Jul 11;18(1):536. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3331-3. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018. PMID: 29996820 Free PMC article. Review.

- Motivation for patient engagement in patient safety: a multi-perspective, explorative survey. Raab C, Gambashidze N, Brust L, Weigl M, Koch A. Raab C, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024 Sep 11;24(1):1052. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11495-x. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024. PMID: 39261814 Free PMC article.

- Medical Professionals' Responses to a Patient Safety Incident in Healthcare. Kupkovicova L, Skoumalova I, Madarasova Geckova A, Dankulincova Veselska Z. Kupkovicova L, et al. Int J Public Health. 2024 Jul 26;69:1607273. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1607273. eCollection 2024. Int J Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39132384 Free PMC article.

- Psychological safety is associated with better work environment and lower levels of clinician burnout. de Lisser R, Dietrich MS, Spetz J, Ramanujam R, Lauderdale J, Stolldorf DP. de Lisser R, et al. Health Aff Sch. 2024 Jul 17;2(7):qxae091. doi: 10.1093/haschl/qxae091. eCollection 2024 Jul. Health Aff Sch. 2024. PMID: 39081721 Free PMC article.

- Improving departmental psychological safety through a medical school-wide initiative. Porter-Stransky KA, Horneffer-Ginter KJ, Bauler LD, Gibson KM, Haymaker CM, Rothney M. Porter-Stransky KA, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Jul 25;24(1):800. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05794-4. BMC Med Educ. 2024. PMID: 39061019 Free PMC article.

- Cultivating a psychological health and safety culture for interprofessional primary care teams through a co-created evidence-informed toolkit. Atanackovic J, Corrente M, Myles S, Eddine Ben-Ahmed H, Urdaneta K, Tello K, Baczkowska M, Bourgeault IL. Atanackovic J, et al. Healthc Manage Forum. 2024 Sep;37(5):334-339. doi: 10.1177/08404704241263918. Epub 2024 Jul 23. Healthc Manage Forum. 2024. PMID: 39042941 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Silverchair Information Systems

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- January 2023

- Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior

Psychological Safety Comes of Age: Observed Themes in an Established Literature

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 24

- Find it at Harvard

About The Author

Amy C. Edmondson

More from the authors.

- September 2024

- Faculty Research

Leading Culture Change at SEB

- September–October 2024

- Harvard Business Review

Where Data-Driven Decision-Making Can Go Wrong

- July 11, 2024

- Harvard Business Review Digital Articles

Research: New Hires’ Psychological Safety Erodes Quickly

- Leading Culture Change at SEB By: Amy C. Edmondson and Cat Huang

- Where Data-Driven Decision-Making Can Go Wrong By: Michael Luca and Amy C. Edmondson