Evaluating Business Presentations: A Six Point Presenter Skills Assessment Checklist

Posted by Belinda Huckle | On April 18, 2024 | In Presentation Training, Tips & Advice

In this Article...quick links

1. Ability to analyse an audience effectively and tailor the message accordingly

2. ability to develop a clear, well-structured presentation/pitch that is compelling and persuasive, 3. ability to connect with and maintain the engagement of the audience, 4. ability to prepare effective slides that support and strengthen the clarity of the message, 5. ability to appear confident, natural and in control, 6. ability to summarise and close a presentation to achieve the required/desired outcome, effective presentation skills are essential to growth, and follow us on social media for some more great presentation tips:, don’t forget to download our presenter skills assessment form.

For many business people, speaking in front of clients, customers, their bosses or even their own large team is not a skill that comes naturally. So it’s likely that within your organisation, and indeed within your own team, you’ll find varying levels of presenting ability. Without an objective way to assess the presenter skills needed to make a good presentation, convincing someone that presentation coaching could enhance their job performance (benefiting your business), boost their promotion prospects (benefiting their career) and significantly increase their self confidence (benefiting their broader life choices) becomes more challenging.

So, how do you evaluate the presenting skills of your people to find out, objectively, where the skill gaps lie? Well, you work out your presentation skills evaluation criteria and then measure/assess your people against them.

To help you, in this article we’re sharing the six crucial questions we believe you need to ask to not only make a professional assessment of your people’s presenting skills, but to showcase what makes a great presentation. We use them in our six-point Presenter Skills Assessment checklist ( which we’re giving away as a free download at the end of this blog post ). The answers to these questions will allow you to identify the presenter skills strengths and weaknesses (i.e. skills development opportunities) of anyone in your team or organisation, from the Managing Director down. You can then put presenter skills training or coaching in place so that everyone who needs it can learn the skills to deliver business presentations face-to-face, or online with confidence, impact and purpose.

Read on to discover what makes a great presentation and how to evaluate a presenter using our six-point Presenter Skills Assessment criteria so you can make a professional judgement of your people’s presenting skills.

If you ask most people what makes a great presentation, they will likely comment on tangible things like structure, content, delivery and slides. While these are all critical aspects of a great presentation, a more fundamental and crucial part is often overlooked – understanding your audience . So, when you watch people in your organisation or team present, look for clues to see whether they really understand their audience and the particular situation they are currently in, such as:

- Is their content tight, tailored and relevant, or just generic?

- Is the information pitched at the right level?

- Is there a clear ‘What’s In It For Them’?

- Are they using language and terminology that reflects how their audience talk?

- Have they addressed all of the pain points adequately?

- Is the audience focused and engaged, or do they seem distracted?

For your people, getting to know their audience, and more importantly, understanding them, should always be the first step in pulling together a presentation. Comprehending the challenges, existing knowledge and level of detail the audience expects lays the foundation of a winning presentation. From there, the content can be structured to get the presenter’s message across in the most persuasive way, and the delivery tuned to best engage those listening.

Flow and structure are both important elements in a presentation as both impact the effectiveness of the message and are essential components in understanding what makes a good presentation and what makes a good speech. When analysing this aspect of your people’s presentations look for a clear, easy to follow agenda, and related narrative, which is logical and persuasive.

Things to look for include:

- Did the presentation ‘tell a story’ with a clear purpose at the start, defined chapters throughout and a strong close?

- Were transitions smooth between the ‘chapters’ of the presentation?

- Were visual aids, handouts or audience involvement techniques used where needed?

- Were the challenges, solutions and potential risks of any argument defined clearly for the audience?

- Were the benefits and potential ROI quantified/explained thoroughly?

- Did the presentation end with a clear destination/call to action or the next steps?

For the message to stick and the audience to walk away with relevant information they are willing to act on, the presentation should flow seamlessly through each part, building momentum and interest along the way. If not, the information can lose impact and the presentation its direction. Then the audience may not feel equipped, inspired or compelled to implement the takeaways.

Connecting with your audience and keeping them engaged throughout can really be the difference between giving a great presentation and one that falls flat. This is no easy feat but is certainly a skill that can be learned. To do it well, your team need a good understanding of the audience (as mentioned above) to ensure the content is on target. Ask yourself, did they cover what’s relevant and leave out what isn’t?

Delivery is important here too. This includes being able to build a natural rapport with the audience, speaking in a confident, conversational tone, and using expressive vocals, body language and gestures to bring the message to life. On top of this, the slides need to be clear, engaging and add interest to the narrative. Which leads us to point 4…

It’s not uncommon for slides to be used first and foremost as visual prompts for the speaker. While they can be used for this purpose, the first priority of a slide (or any visual aid) should always be to support and strengthen the clarity of the message. For example, in the case of complex topics, slides should be used to visualise data , reinforcing and amplifying your message. This ensures that your slides are used to aid understanding, rather than merely prompting the speaker.

The main problem we see with people’s slides is that they are bloated with information, hard to read, distracting or unclear in their meaning.

The best slides are visually impactful, with graphics, graphs or images instead of lines and lines of text or bullet points. The last thing you want is your audience to be focused on deciphering the multiple lines of text. Instead your slides should be clear in their message and add reinforcement to the argument or story that is being shared. How true is this of your people’s slides?

Most people find speaking in front of an audience (both small and large) at least a little confronting. However, for some, the nerves and anxiety they feel can distract from their presentation and the impact of their message. If members of your team lack confidence, both in their ideas and in themselves, it will create awkwardness and undermine their credibility and authority. This can crush a presenter and their reputation.

This is something that you will very easily pick up on, but the good news is that it is definitely an area that can be improved through training and practice. Giving your team the tools and training they need to become more confident and influential presenters can deliver amazing results, which is really rewarding for both the individual and the organisation.

No matter how well a presentation goes, the closing statement can still make or break it. It’s a good idea to include a recap on the main points as well as a clear call to action which outlines what is required to achieve the desired outcome.

In assessing your people’s ability to do this, you can ask the following questions:

- Did they summarise the key points clearly and concisely?

- Were the next steps outlined in a way that seems achievable?

- What was the feeling in the room at the close? Were people inspired, motivated, convinced? Or were they flat, disinterested, not persuaded?

Closing a presentation with a well-rounded overview and achievable action plan should leave the audience with a sense that they have gained something out of the presentation and have all that they need to take the next steps to overcome their problem or make something happen.

It’s widely accepted that effective communication is a critical skill in business today. On top of this, if you can develop a team of confident presenters, you and they will experience countless opportunities for growth and success.

Once you’ve identified where the skill gaps lie, you can provide targeted training to address it. Whether it’s feeling confident presenting to your leadership team or answering unfielded questions , understanding their strengths and weaknesses in presenting will only boost their presenting skills. This then creates an ideal environment for collaboration and innovation, as each individual is confident to share their ideas. They can also clearly and persuasively share the key messaging of the business on a wider scale – and they and the business will experience dramatic results.

Tailored Training to Fill Your Presentation Skill Gaps

If you’re looking to build the presentation skills of your team through personalised training or coaching that is tailored to your business, we can help. For nearly 20 years we have been Australia’s Business Presentation Skills Experts , training & coaching thousands of people in an A-Z of global blue-chip organisations. All our programs incorporate personalised feedback, advice and guidance to take business presenters further. To find out more, click on one of the buttons below:

- Work Email Address * Please enter your email address and then click ‘download’ below

Written By Belinda Huckle

Co-Founder & Managing Director

Belinda is the Co-Founder and Managing Director of SecondNature International. With a determination to drive a paradigm shift in the delivery of presentation skills training both In-Person and Online, she is a strong advocate of a more personal and sustainable presentation skills training methodology.

Belinda believes that people don’t have to change who they are to be the presenter they want to be. So she developed a coaching approach that harnesses people’s unique personality to build their own authentic presentation style and personal brand.

She has helped to transform the presentation skills of people around the world in an A-Z of organisations including Amazon, BBC, Brother, BT, CocaCola, DHL, EE, ESRI, IpsosMORI, Heineken, MARS Inc., Moody’s, Moonpig, Nationwide, Pfizer, Publicis Groupe, Roche, Savills, Triumph and Walmart – to name just a few.

A total commitment to quality, service, your people and you.

Mayo's Clinics

- Email Subscription

Use Clear Criteria and Methodologies When Evaluating PowerPoint Presentations

Dr. Fred Mayo explains the three major methods for presentation evaluation: self, peer and professional. An added bonus: ready-made student evaluation form.

By Dr. Fred Mayo, CHE, CHT

In the last issue, we discussed making interactive presentations and this month we will focus on evaluating presentations. For many of us, encouraging and supporting students in making presentations is already a challenge; assessing their merit is often just another unwelcome teaching chore.

There are three major methods for evaluating presentation – self evaluations, peer evaluations, and professional evaluations. Of course, the most important issue is establishing evaluation criteria.

Criteria for Evaluating Presentations One of the best ways to help students create and deliver good presentations involves providing them with information about how their presentations will be evaluated. Some of the criteria that you can use to assess presentations include:

- Focus of the presentation

- Clarity and coherence of the content

- Thoroughness of the ideas presented and the analysis

- Clarity of the presentation

- Effective use of facts, statistics and details

- Lack of grammatical and spelling errors

- Design of the slides

- Effective use of images

- Clarity of voice projection and appropriate volume

- Completion of the presentation within the allotted time frame

Feel free to use these criteria or to develop your own that more specifically match your teaching situation.

Self Evaluations When teaching public speaking and making presentations, I often encouraged students to rate their own presentations after they delivered them. Many times, they were very insightful about what could have been improved. Others just could not complete this part of the assignment. Sometimes, I use their evaluations to make comments on what they recognized in their presentations. However, their evaluations did not overly influence the grade except that a more thorough evaluation improved their grade and a weak evaluation could hurt their presentation grade.

Questions I asked them to consider included:

- How do you think it went?

- What could you have done differently to make it better?

- What did you do that you are particularly proud of accomplishing?

- What did you learn from preparing for and delivering this presentation?

- What would you change next time?

Peer Evaluations One way to provide the most feedback for students involves encouraging – or requiring – each student evaluate each other’s presentation. It forces them to watch the presentation both for content and delivery and helps them learn to discriminate between an excellent and an ordinary presentation. The more presentations they observe or watch, the more they learn.

In classes where students are required to deliver presentations, I have students evaluate the presentations they observe using a form I designed. The students in the audience give the evaluation or feedback forms to the presenter as soon as it is over. I do not collect them or review them to encourage honest comments and more direct feedback. Also, students do not use their names when completing the form. That way the presenter gets a picture from all the students in the audience – including me – and cannot discount the comments by recognizing the author.

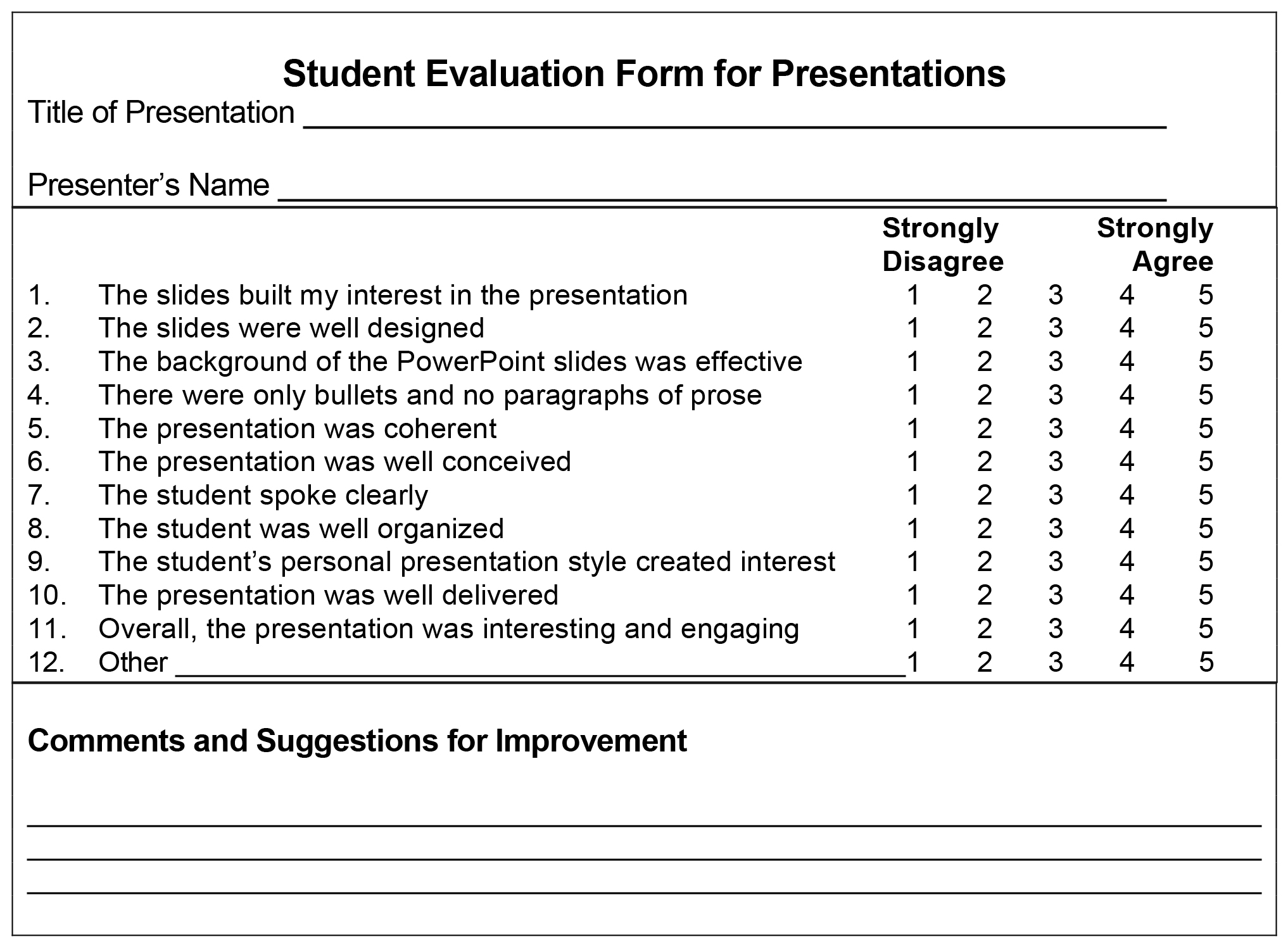

A version of the form that I use is reproduced below – feel free to adopt or adapt it to your own use and classroom situation.

Professional Evaluations When conducting your professional evaluation of a presentation, remember to consider when and how to deliver oral comments as opposed to a completed form. I complete a written evaluation (shown above) along with all the students so they get some immediate feedback. I also take notes on the presentation and decide a grade as well. After the conclusion of the presentation, whether it was an individual or team presentation, I lead a class discussion on the presentation material. That way, students get to hear some immediate comments as well as reading the written peer evaluations.

I usually ask for a copy of the presentation prior to the delivery date. (Getting the PowerPoint slides ahead also helps me ensure I have all the presentations loaded on the projector or computer so we do not waste class time.) Students either email it to me or place it on our classroom management system. I will provide their letter grade and make comments on the design of the presentation on the copy they gave me. However, I don’t explain the final grade right after the presentation since it is often hard for students who have just made a presentation to hear comments.

Summary Each of these suggestions may prompt you to try your own ideas. Remember that students improve when they receive thoughtful and useful feedback from their peers and you as their teacher. I encourage you to use this form or develop a form so that the criteria used to evaluate the presentations are clear and explained ahead of time. Now, you can enjoy evaluating their presentations.

Dr. Fred Mayo, CHE, CHT, is retired as a clinical professor of hotel and tourism management at New York University. As principal of Mayo Consulting Services, he continues to teach around the globe and is a regular presenter at CAFÉ events nationwide.

Assessing Oral Presentation Performance: Designing a Rubric and Testing its Validity with an Expert Group

- Hogeschool Utrecht

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- MM Consultancy for Education and Training

- Laurea Universities of Applied Sciences

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- J COMPUT ASSIST LEAR

- Hugo Huurdeman

- Julia Fischmann

- Víctor Raul Ferrer-Pardo

- Cindy Bolaños-Mendoza

- Federico X. Dominguez Bonini

- Fatemeh Saneie Kashanifar

- Anouchka Bonnes

- Sarah Krochinak

- Babatunde Ajayi

- STUD HIGH EDUC

- Internet High Educ

- Vincent Chan

- Educ Res Rev

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Presentations

An engaging presentation has a clear purpose; shows good understanding of the topic and its importance; is correctly pitched at the audience; and provides the audience with a key message to take forward.

Being a good presenter takes much practice. Practising and improving your presentations will also increase your oral communication skills and confidence.

Presentations are assessed on your content (what you present), your delivery (how you present it) and your visual aids (how they aid your presentation). Always check your assignment guidelines and marking rubric for specific information relating to your subject or discipline.

Understanding requirements

Review your topic, assessment criteria and marking rubric well in advance of the presentation.

- What is the reason for your presentation? Is it to present findings from research? Summarise a topic? Inform a client? Lead a discussion? Or to inspire?

- What is your topic?

- Who will be your audience?

- Will it be online or in-person? Is it an individual or team presentation?

- How much time do you and/or your team have for presenting?

- What visual aids can you use?

A presentation must be carefully planned. Focus on what you must include in your presentation to make it engaging and inspiring.

- What is the purpose of your work? What is the research question you set out to answer?

- What are your key findings? What research is yet to be done?

- What part of your topic and/or findings is most important?

- What is relevant or applicable to your audience?

- Do you want the audience actively involved? How will you achieve that?

- Overall, what do you want to achieve? To inform, inspire, convince, summarise?

- For online presentations, check access to required systems, programs, or platforms.

Structuring

Organise and structure your material and communicate it effectively to your audience.

Introduction (5% to 10% of time)

- Introduce yourself. Say your name clearly for the audience and assessors.

- Grab the attention of your audience by using a related story, a statistic or asking a question.

- Describe your topic area and purpose, objective, or the question you set out to answer.

- Be clear about your purpose. ‘The purpose is to…’. ‘I will focus on...’

- Explain the need or reasons for your work. ‘This is important because…’

- Describe the themes of your talk. ‘First, I will…, then, I will…, and finally…’

- Present your work logically. Develop a coherent story.

- Don’t cover too much on one slide.

- Do transitions well; indicate when you move to another theme. ‘My next point is ...’

- Use examples/diagrams to explain key points. Real-life examples will engage your audience.

- Present only your main points. Don’t try to fit in all your work or theory, as time is limited.

Conclusion (5% to 10% of time)

- Summarise your key points. ‘In conclusion...’, ‘To recap the main points…’

- Discuss your achievements in relation to your objectives (from Introduction).

- Explain reasons if objectives haven’t been achieved and how or what could be improved.

- Discuss the implications of your work and restate your key (take home) message.

- Thank your audience and invite questions.

For online presentations – check all technology and programs before your presentation. Do practice runs to familiarise yourself with presenting online.

Language and voice

- Use plain language. Keep it simple. Avoid slang and acronyms.

- Emphasise the key points. Repeat them using different phrasing.

- Check your pronunciation of difficult and unusual words. Pronounce keywords correctly.

- Project your voice. Speak loudly so that everyone will hear you.

- Speak slowly and clearly. Don’t rush. Pace yourself. 125 - 150 words per minute is good.

- Vary your voice quality. Use tonal variations. Don’t be monotonal.

- Use pauses and don't be afraid of short periods of silence. They give you and your audience a chance to think. Pauses also give the audience members time to take notes.

- For online presentations, check your audio system and sound level.

Non-verbal cues

- Stand or sit up straight (if online), hold your head up and try to look relaxed.

- Make eye contact with audience members or look directly at the camera.

- Avoid turning away from the audience or camera when looking at presentation slides.

- Pay attention to your group members when they are speaking.

Engaging your audience

- Always pay attention to your audience. Check that the audience is engaged. ‘Does this make sense?’. ‘Is this clear?’.

- Treat your presentation as a conversation between you and your audience. Always speak to the audience, avoid reading from notes.

- Speak confidently. Confident presenters can better engage an audience.

- Run polls, questionnaires or pose questions to your audience.

- Include short activities. ‘Discuss… with the person next to you… and report back…’.

- Be prepared to pause the presentation to respond to questions or clarify points.

- Use exemplars or prototypes to demonstrate or illustrate key points.

- Prepare questions for your Q&A in case there are no questions from the audience.

- For online presentations, use chat, whiteboards, annotations, polls, breakout rooms and other functionalities of programs such as Zoom.

Visual aids

Powerpoint slides.

- Keep the text brief. ‘Less in more’. Use the 6 X 6 rule: 6 lines with 6 words each per slide.

- Include a title slide with your topic, name (or names, if team) contact details and course.

- Keep your slide design simple and formatting consistent.

- Use headings, sub-headings, and bullet points.

- Select figures, tables, and images carefully. Too many may overwhelm your audience.

- Label and number figures etc. and use in-text referencing as appropriate.

- Discuss or refer to all figures etc. in your delivery.

- Slow down for images and figures etc. The audience may need time to absorb such information.

- Check your slides for readability. Proofread for grammar and referencing.

- Include a slide with a list of references.

Don’t spend all your time producing visual aids. They are necessary. But your content and delivery are equally or sometimes more important. Check your marking rubric or assessment guidelines for how you will be assessed and spend your time accordingly.

Team presentations

You share the workload in a team presentation. It is a team effort. Each must contribute equally to developing the team presentation. You may be assessed as a team or individually. You may also be expected to present and/or answer questions. Always check your assignment guidelines and marking rubric for subject or discipline-specific requirements.

- Check if all members are required to speak. Put more confident speakers first and/or last.

- Introduce all your team members at the start of presentation.

- Do transitions well. Clearly signal your hand over to next speaker. ‘The next speaker is …’.

- Briefly summarise what previous speaker covered to show connection/segue to your part.

- Always pay attention to the (active) speaker and be ready to add to the presentation.

Reducing anxiety

- Be very well prepared. Practise until you feel confident about all your material. If you are not confident, it is harder to reduce anxiety.

- Practice in front of your friends and family. Ask for constructive feedback to improve.

- Treat your audience like they’re your friends. Your audience is interested in what you have to say and wants you to do well - that is why they are there.

- During in-person presentations, make eye contact with people you know in the room.

- Being anxious is normal. Take deep breaths to calm yourself. Tell yourself, all will be well!

Further resources

- 5 public speaking tips to persuade any audience 4 minute video from La Trobe's 3-Minute-Thesis (3MT) champion Nicole Shackleton

- 7 skills of every good speaker

- Presentations - Chapter in 'Academic Success' (eBook)

- Inspirational speech from Barak Obama (YouTube)

- 10 most popular TEDx talks

Pathfinder link

Still have questions? Do you want to talk to an expert? Peer Learning Advisors or Academic Skills and Language Advisors are available.

- << Previous: Literature reviews

- Next: Exams >>

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Educ

Development and validation of the oral presentation evaluation scale (OPES) for nursing students

Yi-chien chiang.

1 Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, Republic of China

Hsiang-Chun Lee

2 Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, Republic of China

Tsung-Lan Chu

3 Administration Center of Quality Management Department, Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, Republic of China

Chia-Ling Wu

Ya-chu hsiao.

4 Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology; Administration Center of Quality Management Department, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, No.261, Wenhua 1st Rd., Guishan Dist, Taoyuan City, 333 03 Taiwan, Republic of China

Associated Data

The datasets and materials of this study are available to the corresponding author on request.

Oral presentations are an important educational component for nursing students and nursing educators need to provide students with an assessment of presentations as feedback for improving this skill. However, there are no reliable validated tools available for objective evaluations of presentations. We aimed to develop and validate an oral presentation evaluation scale (OPES) for nursing students when learning effective oral presentations skills and could be used by students to self-rate their own performance, and potentially in the future for educators to assess student presentations.

The self-report OPES was developed using 28 items generated from a review of the literature about oral presentations and with qualitative face-to-face interviews with university oral presentation tutors and nursing students. Evidence for the internal structure of the 28-item scale was conducted with exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA, respectively), and internal consistency. Relationships with Personal Report of Communication Apprehension and Self-Perceived Communication Competence to conduct the relationships with other variables evidence.

Nursing students’ ( n = 325) responses to the scale provided the data for the EFA, which resulted in three factors: accuracy of content, effective communication, and clarity of speech. These factors explained 64.75% of the total variance. Eight items were dropped from the original item pool. The Cronbach’s α value was .94 for the total scale and ranged from .84 to .93 for the three factors. The internal structure evidence was examined with CFA using data from a second group of 325 students, and an additional five items were deleted. Except for the adjusted goodness of fit, fit indices of the model were acceptable, which was below the minimum criteria. The final 15-item OPES was significantly correlated with the students’ scores for the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension scale ( r = −.51, p < .001) and Self-Perceived Communication Competence Scale ( r = .45, p < .001), indicating excellent evidence of the relationships to other variables with other self-report assessments of communication.

Conclusions

The OPES could be adopted as a self-assessment instrument for nursing students when learning oral presentation skills. Further studies are needed to determine if the OPES is a valid instrument for nursing educators’ objective evaluations of student presentations across nursing programs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-022-03376-w.

Competence in oral presentations is important for medical professionals to communicate an idea to others, including those in the nursing professions. Delivering concise oral presentations is a useful and necessary skill for nurses [ 1 , 2 ]. Strong oral presentation skills not only impact the quality of nurse-client communications and the effectiveness of teamwork among groups of healthcare professionals, but also promotion, leadership, and professional development [ 2 ]. Nurses are also responsible for delivering health-related knowledge to patients and the community. Therefore, one important part of the curriculum for nursing students is the delivery of oral presentations related to healthcare issues. A self-assessment instrument for oral presentations could provide students with insight into what skills need improvement.

Three components have been identified as important for improving communication. First, a presenter’s self-esteem can influence the physio-psychological reaction towards the presentation; presenters with low self-esteem experience greater levels of anxiety during presentations [ 3 ]. Therefore, increasing a student’s self-efficacy can increase confidence in their ability to effectively communicate, which can reduce anxiety [ 3 , 4 ]. Second, Liao (2014) reported improving speaking efficacy can also improve oral communications and collaborative learning among students could improve speech efficacy and decrease speech anxiety [ 5 ]. A study by De Grez et al. provided students with a list of skills to practice, which allowed them to feel more comfortable when a formal presentation was required, increased presentation skills, and improved communication by improving self-regulation [ 6 ]. Third, Carlson and Smith-Howell (1995) determined quality and accuracy of the information presented was also an important aspect of public speaking performances [ 7 ]. Therefore, all three above mentioned components are important skills for effective communication during an oral presentation.

Instruments that provide an assessment of a public speaking performance are critical for helping students’ improve oral presentation skills [ 7 ]. One study found peer evaluations were higher than those of university tutors for student presentations, using a student-developed assessment form [ 8 ]. The assessment criteria included content (40%), presentation (40%), and structure (20%); the maximum percent in each domain was given for “excellence”, which was relative to a minimum “threshold”. Multiple “excellence” and “threshold” benchmarks were described for each domain. For example, benchmarks included the use of clear and appropriate language, enthusiasm, and keeping the audience interested. However, the percentage score did not provide any information about what specific benchmarks were met. Thus, these quantitative scores did not include feedback on specific criteria that could enhance future presentations.

At the other extreme is an assessment that is limited to one aspect of the presentation and is too detailed to evaluate the performance efficiently. An example of this is the 40-item tool developed by Tsang (2018) [ 6 ] to evaluate oral presentation skills, which measured several domains: voice (volume and speed), facial expressions, passion, and control of time. An assessment tool developed by De Grez et al. (2009) includes several domains: three subcategories for content (quality of introduction, structure, and conclusion), five subcategories of expression (eye-contact, vocal delivery, enthusiasm, interaction with audience, and body-language), and a general quality [ 9 ]. Many items overlap, making it hard to distinguish specific qualities. Other evaluation tools include criteria that are difficult to objectively measure, such as body language, eye-contact, and interactions with the audience [ 10 ]. Finally, most of the previous tools were developed without testing the reliability and validity of the instrument.

Nurses have the responsibility of not only providing medical care, but also medical information to other healthcare professionals, patients, and members of the community. Therefore, improving nursing students’ speaking skills is an important part of the curriculum. A self-report instrument for measuring nursing students’ subjective assessment of their presentation skills could help increase competence in oral communication. However, to date, there is a no reliable and valid instrument of evaluating oral presentation performance in nursing education. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a self-assessment instrument for nursing students that could guide them in understanding their strengths and development areas in aspects of oral presentations. Development of a scale that is a valid and reliable instrument for nursing students could then be examined for use as a scale for objective evaluations of oral presentations by peers and nurse educators.

Study design

This study developed and validated an oral presentation evaluation scale (OPES) that could be employed as a self-assessment instrument for students when learning skills for effective oral presentations. The instrument was developed in two phases: Phase I (item generation and revision) and Phase II (scale development) [ 11 ]. The phase I was aimed to generate items by a qualitative method and to collect content evidence for the OPES. The phase II focused on scale development which was established internal structure evidence including CFA, EFA, and internal consistency of the scale for the OPES. In addition, the phase II collected the evidence of OPES on relationships with other variables. Because we hope to also use the instrument as an aid for nurse educators in objective evaluations of nursing students’ oral presentations, both students and educators were involved in item generation and revision. Only nursing students participated in Phase II.

Approval was obtained from Chang Gung Medical Foundation institutional review board (ID: 201702148B0) prior to initiation of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. All participants being interviewed for item generation in phase I provided signed informed consent indicating willingness to be audiotaped during the interview. All the study methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Phase I: item generation and item revision

Participants.

A sample of nurse educators ( n = 8) and nursing students (n = 11) participated in the interviews for item generation. Nursing students give oral presentations to meet the curriculum requirement, therefore the educators were university tutors experienced in coaching nursing students preparing to give an oral presentation. Nurse educators specializing in various areas of nursing, such as acute care, psychology, and community care were recruited if they had at least 10 years’ experience coaching university students. The mean age of the educators was 52.1 years ( SD = 4.26), 75% were female, and the mean amount of teaching experience was 22.6 years ( SD = 4.07). Students were included if they had given at least one oral presentation and were willing to share their experiences of oral presentation. The mean age of the students was 20.7 ( SD = 1.90), 81.8% were female; 36.3%, four were second year students, three were third students, and four were in their fourth year.

An additional eight educators participated in the evaluation of content evidence of the ORES. All had over 10 years’ experience in coaching students in giving an oral presentation that would be evaluated for a grade.

Item generation

Development of item domains involved deductive evaluations of the about oral presentations [ 2 , 3 , 6 – 8 , 12 – 14 ]. Three domains were determined to be important components of an oral presentation: accuracy of content, effective communication, and clarity of speech. Inductive qualitative data from face-to-face semi-structured interviews with nurse educators and nursing student participants were used to identify domain items [ 11 ]. Details of interview participants are described in the section above. The interviews with nurse educators and students followed an interview guide (Table 1 ) and lasted approximately 30–50 min for educators and 20–30 min for students. Deduction of the literature and induction of the interview data was used to determine categories considered important for the objective evaluation of oral presentations.

Interview guide for semi-structured interviews with nurse educators and nursing students for item generation

| Participant group | Questions |

|---|---|

| Educator | 1.What has been your reaction to oral reports or presentations given by your students? |

| 2. What problems commonly occur when students are giving oral reports or presentations? | |

| 3. In your opinion, what do you consider a good presentation, and could you describe the characteristics? | |

| 4. How do you evaluate the performance of the student’s oral reports or presentations? Are there any difficulties or problems evaluating the oral reports? | |

| Student | 1. Would you please tell me about your experiences of giving an oral report or presentation? |

| 2. In your opinion, what is a good presentation and what are some of the important characteristics? |

Analysis of interview data. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim at the conclusion of each interview. Interview data were analyzed by the first, second, and corresponding author, all experts in qualitative studies. The first and second authors coded the interview data to identify items educators and student described as being important to the experience of an oral presentation [ 11 ]. The corresponding author grouped the coded items into constructs important for oral presentations. Meetings with the three researchers were conducted to discuss the findings; if there were differences in interpretation, an outside expert in qualitative studies was included in the discussions until consensus was reached among the three researchers.

Analysis of the interview data indicated items involved in preparation, presentation, and post-presentation were important to the three domains of accuracy of content, effective communication, and clarity of speech. Items for accuracy of content involved preparation (being well-prepared before the presentation; preparing materials suitable for the target audience; practicing the presentation in advance) and post-presentation reflection; and discussing the content of the presentation with classmates and teachers. Items for effective communication involved the presentation itself: obtain the attention of the audience; provide materials that are reliable and valuable; express confidence and enthusiasm; interact with the audience; and respond to questions from the audience. The third domain, clarity of speech, involved of items could be, post-presentation, involved a student’s ability to reflect on the content and performance of their presentation and willingness to obtain feedback from peers and teachers.

Item revision: content evidence

Based on themes that emerged during, 28 items were generated. Content evidence of the 28 items of the OPES was established with a panel of eight experts who were educators that had not participated in the face-to-face interviews. The experts were provided with a description of the research purpose, a list of the proposed items, and were asked to rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not representative, 2 = item needs major revision, 3 = representative but needs minor revision, 4 = representative). For item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was determined by the total items rated 3 or 4 divided by the total number of experts; scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) was determined by the total items rated 3 or 4 divided by the total number of items.

Based on the suggestions of the experts, six items of the OPES were reworded for clarity: item 12 was revised from “The presentation is riveting” to “The presenter’s performance is brilliant; it resonates with the audience and arouses their interests”. Two items were deleted because they duplicated other items: “demonstrates confidence” and “presents enthusiasm” were combined and item 22 became, “demonstrates confidence and enthusiasm properly”. The item “the presentation allows for proper timing and sequencing” and “the length of time of the presentation is well controlled” were also combined into item 9, “The content of presentation follows the rules, allowing for the proper timing and sequence”. Thus, a total of 26 items were included in the OPES at this phase. The I-CVI value was .88 ~ 1 and the scale-level CVI/universal agreement was .75, indicating that the OPES was an acceptable instrument for measuring an oral presentation [ 11 ].

Phase II: scale development

Phase II, scale development, aimed to establish the internal structure evidence for OPES. The evidence of relation to other variables was also evaluated as well in this phase. More specifically, the internal structure evidence for OPES was evaluated by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The evidence of relationships to other variables was determined by examining the relationships between the OPES and the PRCA and SPCC [ 15 ].

A sample of nursing students was recruited purposively from a university in Taiwan. Students were included if they were: (a) full-time students; (b) had declared nursing as their major; and (c) were in their sophomore, junior, or senior year. First-year university students (freshman) were excluded. A bulletin about the survey study was posted outside of classrooms; 707 students attend these classes. The bulletin included a description of the inclusion criteria and instructions to appear at the classroom on a given day and time if students were interested in participating in the study. Students who appeared at the classroom on the scheduled day ( N = 650) were given a packet containing a demographic questionnaire (age, gender, year in school), a consent form, the OPES instrument, and two scales for measuring aspects of communication, the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (PRCA) and the Self-Perceived Communication Competence (SPCC); the documents were labeled with an identification number to anonymize the data. The 650 students were divided into two groups, based on the demographic data using the SPSS random case selection procedure, (Version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The selection procedure was performed repeatedly until the homogeneity of the baseline characteristics was established between the two groups ( p > .05). The mean age of the participants was 20.5 years ( SD = 0.98) and 87.1% were female ( n = 566). Participants were comprised of third-year students (40.6%, n = 274), fourth year (37.9%, n = 246) and second year (21.5%, n = 93). The survey data for half the group (calibration sample, n = 325) was used for EFA; the survey data from the other half (the validation sample, n = 325) was used for CFA. Scores from the PRCA and SPCC instruments were used for evaluating the evidence of relationships to other variables.

The aims of phase II were to collect the scale of internal structure evidence, which identify the items that nursing students perceived as important during an oral presentation and to determine the domains that fit a set of items. The 325 nursing students for EFA (described above) were completed the data collection. We used EFA to evaluate the internal structure of the scale. The items were presented in random order and were not nested according to constructs. Internal consistency of the scale was determined by calculating Cronbach’s alpha.

Then, the next step involved determining if the newly developed OPES was a reliable and valid self-report scale for subjective assessments of nursing students’ previous oral presentations. Participants (the second group of 325 students) were asked, “How often do you incorporate each item into your oral presentations?”. Responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = never to 5 = always; higher scores indicated a better performance. The latent structure of the scale was examined with CFA.

Finally, the evidence of relationships with other variables of the OPES was determined by examining the relationships between the OPES and the PRCA and SPCC, described below.

The 24-item PRCA scale

The PRCA scale is a self-report instrument for measuring communication apprehension, which is an individual’s level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with a person or persons [ 12 ]. The 24 scale items are comprised of statements concerning feelings about communicating with others. Four subscales are used for different situations: group discussions, interpersonal communications, meetings, and public speaking. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); scores range from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating greater communication anxiety. The PRCA has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid scale across a wide range of related studies [ 5 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 ]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is .90 [ 18 ]. We received permission from the owner of the copyright to translate the scale into Chinese. Translation of the scale into Chinese by a member of the research team who was fluent in English was followed by back-translation from a differed bi-lingual member of the team to ensure semantic validity of the translated PRCA scale. The Cronbach’s alpha value in the present study was .93.

The 12-item SPCC scale

The SPCC scale evaluates a persons’ self-perceived competence in a variety of communication contexts and with a variety of types of receivers. Each item is a situation which requires communication, such as “Present a talk to a group of strangers”, or “Talk with a friend”. Participants respond to each situation by ranking their level of competence from 0 (completely incompetent) to 100 (completely competent). The Cronbach’s alpha for reliability of the scale is .85. The SPCC has been used in similar studies [ 13 , 19 ]. We received permission owner of the copyright to translate the scale into Chinese. Translation of the SPCC scale into Chinese by a member of the research team who was fluent in English was followed by back-translation from a differed bi-lingual member of the team to ensure semantic validity of the translated scale. The Cronbach’s alpha value in the present study was .941.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data from the 325 students designated for EFA was used to determine the internal structure evidence of the OPES. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure for sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity demonstrated factor analysis was appropriate [ 20 ]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the 26 items to extract the major contributing factors; varimax rotation determined relationships between the items and contributing factors. Factors with an eigenvalue > 1 were further inspected. A factor loading greater than .50 was regarded as significantly relevant [ 21 ].

All item deletions were incorporated one by one, and the EFA model was respecified after each deletion, which reduced the number of items in accordance with a priori criteria. In the EFA phase, the internal consistency of each construct was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, with a value of .70 or higher considered acceptable [ 22 ].

Data from the 325 students designated for CFA was used to validate the factor structure of the OPES. In this phase, items with a factor loading less than .50 were deleted [ 21 ]. The goodness of the model fit was assessed using the following: absolute fit indices, including goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); relative fit indices, normed and non-normed fit index (NFI and NNFI, respectively), and comparative fit index (CFI); and the parsimony NFI, CFI, and likelihood ratio ( x 2 /df ) [ 23 ].

In addition to the validity testing, a research team, which included a statistician, determined the appropriateness of either deleting or retaining each item. The convergent validity (internal quality of the items and factor structures), was further verified using standardized factor loading, with values of .50 or higher considered acceptable, and average variance extraction (AVE), with values of .5 or higher considered acceptable [ 21 ]. Convergent reliability (CR) was assessed using the construct reliability from the CFA, with values of .7 or higher considered acceptable [ 24 ]. The AVE and correlation matrices among the latent constructs were used to establish discriminant validity of the instrument. The square root of the AVE of each construct was required to reach a value that was larger than the correlation coefficient between itself and the other constructs [ 24 ].

The evidence of relationships with other variables was determined by examining the relationship of nursing students’ scores ( N = 650) on the newly developed OPES with scores for constructs of communication of the translated scales for PRCA and SPCC. The hypotheses between OPES to PRCA and SPCC individually indicated the strong self-reported presentation competence were associated with lower communication anxiety and greater communication competence.

Development of the OPES: internal structure evidence

EFA was performed sequentially six times until there were no items with a loading factor < .50 or that were cross-loaded, and six items were deleted (Table 2 ). EFA resulted in 20 items with a three factors solution, which represented 64.75% of the variance of the OPES. The Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the total scale was .94. indicating the scale had sound internal reliability (Table (Table2). 2 ). The three factors were labeled in accordance with the item content via a panel discussion and had Cronbach’s alpha values of .93, .89, and .84 for factors 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Summary of exploratory factor analysis: descriptive statistics, factor loading, and reliability for nursing students ( N = 325)

| Score | Factor loading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Description | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | The content of the presentation matches the theme | 4.25 | 0.62 | .76 | .20 | .17 |

| 14 | Presentation aids, such as PowerPoint and posters, highlight key points of the report | 4.21 | 0.74 | .75 | .21 | .30 |

| 15 | Proper use of presentation aids such as PowerPoint and posters | 4.32 | 0.69 | .74 | .12 | .28 |

| 8 | The content of the presentation is clear and focused | 4.02 | 0.69 | .72 | .36 | .11 |

| 10 | The content of the presentation is organized and logical | 3.93 | 0.75 | .72 | .38 | .13 |

| 4 | Preparation of presentation aids, such as PowerPoint and posters, in advance | 4.53 | .67 | .70 | −.10 | .20 |

| 16 | Presentation aids, such as PowerPoint and posters, help the audience understand the content of the presentation | 4.26 | 0.68 | .69 | .20 | .37 |

| 9 | The organization of the presentation is structured to provide the necessary information, while also adhering to time limitations | 4.10 | 0.69 | .68 | .30 | .18 |

| 11 | The content of the presentation provides correct information | 4.12 | 0.66 | .68 | .31 | .10 |

| 1 | Preparation of the content in accordance with the theme and rules in advance | 4.49 | 0.61 | .64 | −.02 | .39 |

| 13 | The entire content of the presentation is prepared in a way that is understandable to the audience | 3.99 | 0.77 | .61 | .40 | .09 |

| 22 | Presenter demonstrates confidence and an appropriate level of enthusiasm | 3.92 | 0.91 | .17 | .83 | .25 |

| 21 | Presenter uses body language in a manner that increases the audience’s interest in learning | 3.50 | 0.95 | .09 | .81 | .22 |

| 24 | Presenter interacts with the audience using eye contact during the question and answer session | 3.65 | 0.92 | .15 | .77 | .24 |

| 23 | Presenter responds to the audience’s questions properly | 3.63 | 0.87 | .23 | .77 | .17 |

| 12 | The presenter’s performance is brilliant; it resonates with the audience and arouses their interests | 3.43 | 0.78 | .43 | .65 | .04 |

| 17 | The pronunciation of the words in the presentation is correct | 3.98 | 0.82 | .31 | .29 | .74 |

| 18 | The tone and volume of the presenter’s voice is appropriate | 3.82 | 0.82 | .22 | .50 | .70 |

| 19 | The words and phrases of the presenter are smooth and fluent | 3.70 | 0.82 | .26 | .52 | .65 |

| 20 | The clothing worn by the presenter is appropriate | 4.16 | 0.77 | .33 | .12 | .57 |

| Eigenvalue (sum of squared loading) | 6.01 | 4.34 | 2.60 | |||

| Explained variance | 30.03% | 21.72% | 13.00% | |||

| Cumulative variance | 30.03% | 51.75% | 64.75% | |||

| Cronbach’s α for each subscale | .93 | .89 | .84 | |||

| Cronbach’s α for the total scale | .94 | |||||

| Item | Deleted following EFA | |||||

| 2 | Considers the background or needs of the audience to prepare the content of the presentation in advance | 3.94 | 0.84 | |||

| 3 | Discusses the content of the presentation with experts, teachers or peers (classmates) in advance | 3.94 | 0.89 | |||

| 5 | Practices several times in private in before the presentation | 3.96 | 0.89 | |||

| 6 | Invites classmates or teachers to watch a rehearsal before the presentation | 3.39 | 1.04 | |||

| 25 | Reflects on the experience as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the presentation | 3.83 | 0.85 | |||

| 26 | Obtains feedback from peers (e.g. classmates), teachers, or an audience | 3.92 | 0.81 | |||

Abbreviations : SD standard deviation, EFA exploratory factor analysis

Factor 1, Accuracy of Content, was comprised of 11 items and explained 30.03% of the variance. Items in Accuracy of Content evaluated agreement between the topic (theme) and content of the presentation, use of presentation aids to highlight the key points of the presentation, and adherence to time limitations. These items included statements such as: “The content of the presentation matches the theme” (item 7), “Presentation aids, such as PowerPoint and posters, highlight key points of the report” (item 14), and “The organization of the presentation is structured to provide the necessary information, while also adhering to time limitations” (item 9). Factor 2, “Effective Communication”, was comprised of five items, which explained 21.72% of the total variance. Effective Communication evaluated the attitude and expression of the presenter. Statements included “Demonstrates confidence and an appropriate level of enthusiasm” (item 22), “Uses body language in a manner that increases the audience’s interest in learning” (item 21), and “Interacts with the audience using eye contact and a question and answer session” (item 24). Factor 3, “Clarity of Speech” was comprised of four items, which explained 13.00% of the total variance. Factor 3 evaluated the presenter’s pronunciation with statements such as “The words and phrases of the presenter are smooth and fluent” (item 19).

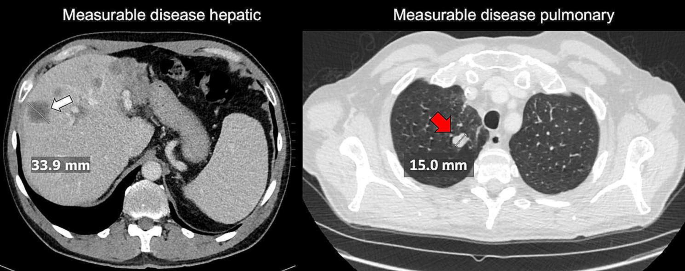

The factor structure of the 20-items of the EFA were examined with CFA. We sequentially removed items 1, 4, 20, 15, and 16, based on modification indices. The resultant 15-item scale had acceptable fit indices for the 3-factor model of the OPES for chi-square ( x 2 /df = 2.851), RMSEA (.076), NNFI (.933), and CFI = .945. However, the AGFI, which was .876, was below the acceptable criteria of .9. A panel discussion with the researchers determined that items 4, 15, and 16 were similar in meaning to item 14; item 1 was similar in meaning to item 7. Therefore, the panel accepted the results of the modified CFA model of the OPES with 15 items and 3-factors.

As illustrated in Table 3 and Fig. 1 , all standardized factor loadings exceeded the threshold of .50, and the AVE for each construct ranged from .517 to .676, indicating acceptable convergent validity. In addition, the CR was greater than .70 for the three constructs (range = .862 to .901), providing further evidence for the reliability of the instrument [ 25 ]. As shown in Table 4 , all square roots of the AVE for each construct (values in the diagonal elements) were greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations (values below the diagonal) [ 24 , 25 ]. These findings provide further support for the validity of the OPES.

Confirmatory factor analysis: convergent reliability and validity of the OPES scale for nursing students ( n = 325)

| Construct/Item | Item score | Factor loading | Reliability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | λ | CR | AVE | ||||

| Accuracy of content | .881 | .517 | |||||

| Item 7 | 4.25 | 0.60 | .695 | 13.774*** | .483 | ||

| Item 14 | 4.23 | 0.68 | .660 | 12.863*** | .435 | ||

| Item 8 | 3.98 | 0.66 | .786 | 16.352*** | .617 | ||

| Item 10 | 3.88 | 0.69 | .828 | 17.703*** | .686 | ||

| Item 9 | 4.03 | 0.72 | .766 | 15.753*** | .586 | ||

| Item 11 | 4.08 | 0.65 | .697 | 13.835*** | .486 | ||

| Item 13 | 3.92 | 0.78 | .569 | 10.687*** | .324 | ||

| Effective Communication | .901 | .647 | |||||

| Item 22 | 3.58 | 0.91 | .894 | 20.230*** | .799 | ||

| Item 21 | 3.43 | 0.97 | .817 | 17.548*** | .668 | ||

| Item 24 | 3.69 | 0.91 | .794 | 16.816*** | .631 | ||

| Item 23 | 3.64 | 0.87 | .854 | 18.802*** | .730 | ||

| Item 12 | 3.41 | 0.79 | .639 | 12.490*** | .408 | ||

| Clarity of speech | .862 | .676 | |||||

| Item 17 | 3.94 | 0.76 | .765 | 15.541*** | .586 | ||

| Item 18 | 3.81 | 0.79 | .881 | 19.002*** | .776 | ||

| Item 19 | 3.70 | 0.76 | .817 | 17.026*** | .667 | ||

Note . λ standardized factor loading, R 2 reliability of item (squared multiple correlation, SMC), CR construct (component/composite) reliability, AVE average variance extraction

*** p < .001

The standardized estimates of CFA model for validation sample

Correlations among the latent variables from confirmatory factor analysis of the OPES scale for nursing students ( n = 325)

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accuracy of content | .719 | ||

| 2. Effective communication | .696*** | .804 | |

| 3. Clarity of speech | .597*** | .703*** | .822 |

a The value in the diagonal element is the square root of AVE of each construct

Development of the OPES: relationships with other variables

Relationships with other variable evidence was examined with correlation coefficients for the total score and subscale scores of the OPES with the total score and subscale scores of the PRCA and SPCC (Table 5 ) from all nursing students who participated in the study and complete all three scales ( N = 650). Correlation coefficients for the total score of the OPES with total scores for the PRCA and SPCC were − .51 and .45, respectively (both p < .001). Correlation coefficients for subscale scores of the OPES with the subscale scores of the PRCA and SPCC were all significant ( p < .001), indicating strong valid evidence of the scale as a self-assessment for effective communication.

Correlation coefficients for total scores and subscale scores for the OPES, PRCA, and SPCC

| Instruments & subscales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. OPES | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Accuracy of content | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Effective Communication | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Clarity of speech | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. PRCA | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Group discussion | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Meetings | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Interpersonal | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Public Speaking | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. SPCC | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Public | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Meeting | ||||||||||||||||

| 13. Group | ||||||||||||||||

| 14. Dyad | ||||||||||||||||

| 15. Stranger | ||||||||||||||||

| 16. Acquaintance | ||||||||||||||||

| 17. Friend |

OPES Oral Presentation Evaluation Scale, PRCA Personal Report of Communication Apprehension, SPCC Self-Perceived Communication Competence

Bold figures all p < .001.

The 15-item OPES was found to be a reliable and valid instrument for nursing students’ self-assessments of their performance during previous oral presentations. The strength of this study is that the initial items were developed using both literature review and interviews with nurse educators, who were university tutors in oral presentation skills, as well as nursing students at different stages of the educational process. Another strength of this study is the multiple methods used to establish the validity and reliability of the OPES, including internal structure evidence (both EFA and CFA) and relationships with other variables [ 15 , 26 ].

Similar to previous to other oral presentation instruments, content analysis of items of the OPES generated from the interviews with educators and students indicated accuracy of the content of a presentation and effective communication were important factors for a good performance [ 3 – 6 , 8 ]. Other studies have also included self-esteem as a factor that can influence the impact of an oral presentation [ 3 ], however, the subscale of effective communication included the item “Demonstrates confidence and an appropriate level of enthusiasm”, which a quality of self-esteem. The third domain was identified as clarity of speech, which is unique to our study.

Constructs that focus on a person’s ability to deliver accurate content are important components for evaluations of classroom speaking because they have been shown to be fundamental elements of public speaking ([ 7 ]). Accuracy of content as it applies to oral presentation for nurses is important not only for communicating information involving healthcare education for patients, but also for communicating with team members providing medical care in a clinical setting.

The two other factors identified in the OPES, effective communication and clarity of speech, are similar to constructs for delivery of a presentation, which include interacting with the audience through body-language, eye-contact, and question and answer sessions. These behaviors indicate the presenter is confident and enthusiastic, which engages and captures the attention of an audience. It seems logical that the voice, pronunciation, and fluency of speech were not independent factors because the presenter’s voice qualities all are keys to effectively delivering a presentation. A clear and correct pronunciation, appropriate tone and volume of a presentation assists audiences in more easily receiving and understanding the content.

Our 15-item OPES scale evaluated the performance based on outcome. The original scale was composed of 26 items that were derived from qualitative interviews with nursing students and university tutors in oral presentations. These items were the result of asking about important qualities at three timepoints of a presentation: before, during, and after. However, most of the items that were deleted were those about the period before the presentation (1 to 6); two items (25 and 26) were about the period after the presentation. Analysis did not reflect the qualitative interview data expressed by educators and students regarding the importance of preparing with practice and rehearsal, and the importance of peer and teacher evaluations. Other studies have suggested that preparation and self-reflection is important for a good presentation, which includes awareness of the audience receiving the presentation, meeting the needs of the audience, defining the purpose of the presentation, use of appropriate technology to augment information, and repeated practices to reduce anxiety [ 2 , 5 , 27 ]. However, these items were deleted in the scale validation stage, possibly because it is not possible to objectively evaluate how much time and effort the presenter has devoted to the oral presentation.

The deletion of item 20, “The clothing worn by the presenter is appropriate” was also not surprising. During the interviews, educators and students expressed different opinions about the importance of clothing for a presentation. Many of the educators believed the presenter should be dressed formally; students believed the presenter should be neatly dressed. These two perspectives might reflect generational differences. However, these results are reminders assessments should be based on a structured and objective scale, rather than one’s personal attitude and stereotype of what should be important about an oral presentation.

The application of the OPES may be useful not only for educators but also for students. The OPES could be used a checklist to help students determine how well their presentation matches the 15 items, which could draw attention to deficiencies in their speech before the presentation is given. Once the presentation has been given, the OPES could be used as a self-evaluation form, which could help them make modifications to improve the next the next presentation. Educators could use the OPES to evaluate a performance during tutoring sessions with students, which could help identify specific areas needing improvement prior to the oral presentation. Although, analysis of the scale was based on data from nursing students, additional assessments with other populations of healthcare students should be conducted to determine if the OPES is applicable for evaluating oral presentations for students in general.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Participants were selected by non-random sampling, therefore, additional studies with nursing students from other nursing schools would strengthen the validity and reliability of the scale. In addition, the OPES was developed using empirical data, rather than basing it on a theoretical framework, such as anxiety and public speaking. Therefore, the validity of the OPES for use in other types of student populations or cultures that differ significantly from our sample population should be established in future studies. Finally, the OPES was in the study was examined as a self-assessment instrument for nursing students who rated themselves based on their perceived abilities previous oral presentations rather than from peer or nurse educator evaluations. Therefore, applicability of the scale as an assessment instrument for educators providing an objective score of nursing students’ real-life oral presentations needs to be validated in future studies.

This newly developed 15-item OPES is the first report of a valid self-assessment instrument for providing nursing students with feedback about whether necessary targets for a successful oral presentation are reached. Therefore, it could be adopted as a self-assessment instrument for nursing students when learning what oral presentation require skills require strengthening. However, further studies are needed to determine if the OPES is a valid instrument for use by student peers or nursing educators evaluating student presentations across nursing programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants for their kind cooperation and contribution to the study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors conceptualized and designed the study. Data were collected by Y-CH and H-CL. Data analysis was conducted by Y-CH and Y-CC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Y-CH, Y-CC, and all authors contributed to subsequent revisions. All authors read and approved the final submission.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology Taiwan (MOST 107–2511-H-255-007), Ministry of Education (PSR1090283), and the Chang Gung Medical Research Fund (CMRPF3K0021, BMRP704, BMRPA63).

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

All the study methods and materials have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsink. The study protocol and the procedures of the study were approved by Chang Gung Medical Foundation institutional review board (number: 201702148B0) for the protection of participants’ confidentiality. All of the participants received oral and written explanations of the study and its procedures, as well as informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Not applicable.

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yi-Chien Chiang, Email: wt.ude.tsugc.wg@gnaihccy .

Hsiang-Chun Lee, Email: wt.ude.tsugc.wg@eelyhtac .

Tsung-Lan Chu, Email: wt.gro.hmgc@57cej .

Chia-Ling Wu, Email: wt.ude.tsugc.liam@uwlc .

Ya-Chu Hsiao, Email: wt.ude.tsugc.wg@oaihsjy .

Rubric for Evaluating Student Presentations

- Kellie Hayden

- Categories : Student assessment tools & principles

- Tags : Teaching methods, tools & strategies

Make Assessing Easier with a Rubric

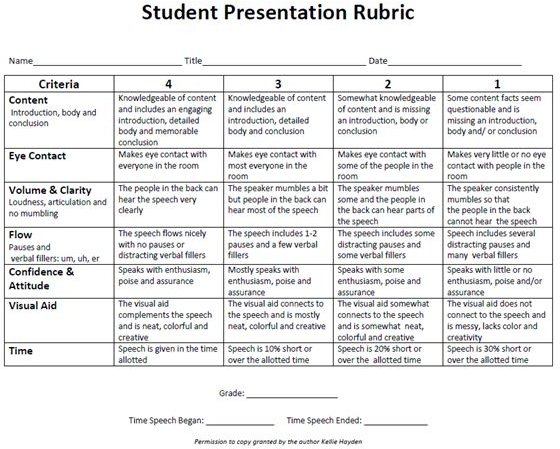

The rubric that you use to assess your student presentations needs to be clear and easy to read by your students. A well-thought out rubric will also make it easier to grade speeches.

Before directing students to create a presentation, you need to tell them how they will be evaluated with the rubric. For every rubric, there are certain criteria listed or specific areas to be assessed. For the rubric download that is included, the following are the criteria: content, eye contact, volume and clarity, flow, confidence and attitude, visual aids, and time.

Student Speech Presentation Rubric Download

Assessment Tool Explained in Detail

Content : The information in the speech should be organized. It should have an engaging introduction that grabs the audience’s attention. The body of the speech should include details, facts and statistics to support the main idea. The conclusion should wrap up the speech and leave the audiences with something to remember.

In addition, the speech should be accurate. Teachers should decide how students should cite their sources if they are used. These should be turned in at the time of the speech. Good speakers will mention their sources during the speech.

Last, the content should be clear. The information should be understandable for the audience and not confusing or ambiguous.

Eye Contact

Students eyes should not be riveted to the paper or note cards that they prepare for the presentation. It is best if students write talking points on their note cards. These are main points that they want to discuss. If students write their whole speech on the note cards, they will be more likely to read the speech word-for-word, which is boring and usually monotone.

Students should not stare at one person or at the floor. It is best if they can make eye contact with everyone in the room at least once during the presentation. Staring at a spot on the wall is not great, but is better than staring at their shoes or their papers.

Volume and Clarity

Students should be loud enough so that people sitting in the back of the room can hear and understand them. They should not scream or yell. They need to practice using their diaphragm to project their voice.

Clarity means not talking too fast, mumbling, slurring or stuttering. When students are nervous, this tends to happen. Practice will help with this problem.

When speaking, the speaker should not have distracting pauses during the speech. Sometimes a speaker may pause for effect; this is to tell the audience that what he or she is going to say next is important. However, when students pause because they become confused or forget the speech, this is distracting.

Another problem is verbal fillers. Student may say “um,” “er” or “uh” when they are thinking or between ideas. Some people do it unintentionally when they are nervous.

If students chronically say “um” or use any type of verbal filler, they first need to be made aware of the problem while practicing. To fix this problem, a trusted friend can point out when they doing during practice. This will help students be aware when they are saying the verbal fillers.

Confidence and Attitude

When students speak, they should stand tall and exude confidence to show that what they are going to say is important. If they are nervous or are not sure about their speech, they should not slouch. They need to give their speech with enthusiasm and poise. If it appears that the student does not care about his or her topic, why should the audience? Confidence can many times make a boring speech topic memorable.

Visual Aids

The visual that a student uses should aid the speech. This aid should explain a facts or an important point in more detail with graphics, diagrams, pictures or graphs.

These can be presented as projected diagrams, large photos, posters, electronic slide presentations, short clips of videos, 3-D models, etc. It is important that all visual aids be neat, creative and colorful. A poorly executed visual aid can take away from a strong speech.

One of the biggest mistakes that students make is that they do not mention the visual aid in the speech. Students need to plan when the visual aid will be used in the speech and what they will say about it.

Another problem with slide presentations is that students read word-for-word what is on each slide. The audience can read. Students need to talk about the slide and/or offer additional information that is not on the slide.

The teacher needs to set the time limit. Some teachers like to give a range. For example, the teacher can ask for short speeches to be1-2 minutes or 2-5 minutes. Longer ones could be 10-15 minutes. Many students will not speak long enough while others will ramble on way beyond the limit. The best way for students to improve their time limit is to practice.

The key to a good speech is for students to write out an outline, make note cards and practice. The speech presentation rubric allows your students to understand your expectations.

- A Research Guide.com. Chapter 3. Public Speaking .

- 10 Fail Proof Tips for Delivering a Powerful Speech by K. Stone on DumbLittleMan.

- Photo credit: Kellie Hayden

- Planning Student Presentations by Laura Goering for Carleton College.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

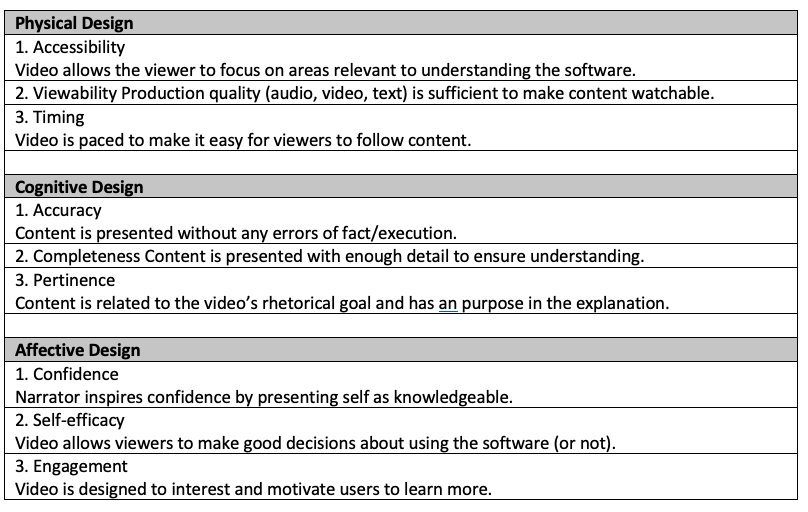

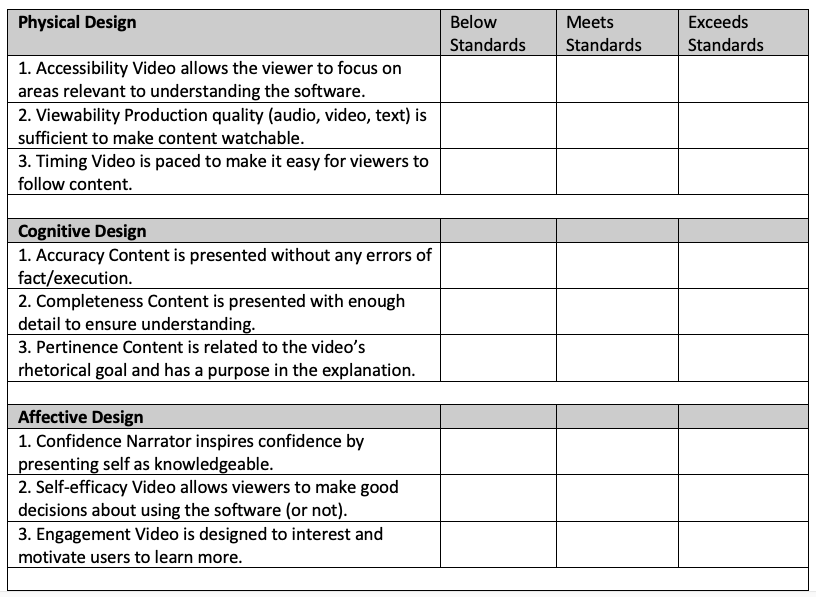

Assessing oral presentations - criteria checklist

Course documents used to assess oral communication - presenting a topic to an audience.

Related Papers

Andrew Leichsenring

Oral presentations are a common form of summative assessment in tertiary level English as a Foreign Language (EFL) syllabi. There will be an array of teaching and learning elements to be considered by a teacher in their set-up and execution of an ICT-based oral presentation activity that goes beyond having students stand in front of a class group and talk about a subject. Teaching effective oral presentation skills to university-level learners requires an understanding of how to maximize learning opportunities to persuasively convey a message orally and visually to an audience.

Timtnew Somrue

ken pelicano

ihyh9h9hiuohuihuiohiuohftydftycfygvuhg

Aysha Sharif