What Is Experiment Marketing? (With Tips and Examples)

Do you feel like your marketing efforts aren’t quite hitting the mark? There’s an approach that could open up a whole new world of growth for your business: marketing experimentation.

This isn’t your typical marketing spiel. It’s about trying new things, seeing what sticks, and learning as you go. Think of it as the marketing world’s lab, where creativity meets strategy in a quest to wow audiences and break the internet.

In this article, we’ll talk about what are marketing experiments, offer some killer tips to implement and analyze marketing experiments, and showcase examples that turned heads.

Ready to dive in?

Shortcuts ✂️

What is a marketing experiment, why should you run marketing experiments, how to design marketing experiments, how to implement marketing experimentation, how to analyze your experiment marketing campaign, 3 real-life examples of experiment marketing.

Marketing experimentation is like a scientific journey into how customers respond to your marketing campaigns.

Imagine you’ve got this wild idea for your PPC ads. Instead of just hoping it’ll work, you test it. That’s your experiment. You’re not just throwing stuff at the wall to see what sticks. You’re carefully choosing your shot, aiming, and then checking the impact.

Marketing experiments involve testing lots of things, like new products and how your marketing messages affect people’s actions on your website.

Running a marketing experiment before implementing new strategies is essential because it serves as a form of insurance for future marketing endeavors.

By conducting marketing experiments, you can assess potential risks and ensure that your efforts align with the desired outcomes you seek.

One of the main advantages of marketing experiments is that they provide insight into your target audience, helping you better understand your customers and optimize your marketing strategies for better results.

By ensuring that your new marketing strategies are the most impactful, you’ll achieve better campaign performance and a better return on investment.

Now that we’ve unpacked what are marketing experiments, let’s dive deeper. To design a successful marketing experiment, follow the steps below.

1. Identify campaign objectives

Establishing clear campaign objectives is essential. What do you want to accomplish? What are your most important goals?

To identify campaign objectives, you can:

- Review your organizational goals

- Brainstorm with your team

- Use the SMART framework (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) to define your objectives

Setting specific objectives ensures that your marketing experiment is geared towards addressing critical business challenges and promoting growth. This focus will also help you:

- Select the most relevant marketing channels

- Define success metrics

- Create more successful campaigns

- Make better business decisions

2. Make a good hypothesis

Making a hypothesis before conducting marketing experiments is crucial because it provides a clear direction for the experiment and helps in setting specific goals to be achieved.

A hypothesis allows marketers to articulate their assumptions about the expected outcomes of various changes or strategies they plan to implement.

By formulating a hypothesis, marketers can create measurable and testable statements that guide the experiment and provide a basis for making informed decisions based on results.

It helps in understanding what impact certain changes may have on your customers or desired outcomes, thus enabling marketers to design effective experiments that yield valuable insights.

3. Select the right marketing channels

Choosing the right marketing channels is crucial for ensuring that your campaign reaches your customers effectively.

To select the most appropriate channels, you should consider factors such as the demographics, interests, and behaviors of your customers, as well as the characteristics of your product or service.

Additionally, it’s essential to analyze your competitors and broader industry trends to understand which marketing channels are most effective in your niche.

4. Define success metrics

Establishing success metrics is a crucial step in evaluating the effectiveness of your marketing experiments.

Defining success metrics begins with identifying your experiment’s objectives and then choosing relevant metrics that can help you measure your success. You’ll also want to set targets for each metric.

Common success metrics include:

- conversion rate,

- cost per acquisition,

- and customer lifetime value.

When selecting appropriate metrics for measuring the success of your marketing experiments, you should consider the nature of the experiment itself – whether it involves email campaigns, landing pages, blogs, or other platforms.

For example, if the experiment involves testing email subject lines, tracking the open rate would be crucial to understanding how engaging the subject lines are for the audience.

When testing a landing page, metrics such as the submission rate during the testing period can reveal how effective the page is in converting visitors.

On the other hand, if the experiment focuses on blogs, metrics like average time on page can indicate the level of reader engagement.

Once you’ve finished designing your marketing experiments, it’s time to put them into action.

This involves setting up test groups, running tests, and then monitoring and adjusting the marketing campaigns as needed.

Let’s see the implementation process in more detail!

1. Setting up test groups

Establishing test groups is essential for accurately comparing different marketing strategies. To set up test groups, you need to define your target audience, split them into groups, create various versions of your content, and configure the test environment.

Setting up test groups ensures your marketing experiment takes place under controlled conditions, enabling you to compare results more accurately.

This, in turn, will help you identify the most effective tactics for your audience.

2. Running multiple tests simultaneously

By conducting multiple tests at the same time, you’ll be able to:

- Collect more data and insights

- Foster informed decision-making

- Improve campaign performance

A/B testing tools that allow for simultaneous experiments can be a valuable asset for your marketing team. By leveraging these tools, you can streamline your experiment marketing process and ensure that you’re getting the best results from your efforts.

3. Monitoring and adjusting the campaign

Monitoring and adjusting your marketing experiment campaign is essential to ensure that the experiment stays on track and achieves its objectives.

To do so, you should regularly:

- Review the data from your experiment to identify any issues.

- Make necessary adjustments to keep the experiment on track.

- Evaluate the results of those adjustments.

Proactive monitoring and adjustment of your campaign helps identify potential problems early, enabling you to make decisions based on data and optimize your experiments.

As discussed above, after implementing your marketing experiment you’ll want to analyze the results and learn from the insights gained.

Remember that the insights gained from your marketing experiments are not only valuable for the current campaign you’re running but also for informing your future marketing initiatives.

By continuously iterating and improving your marketing efforts based on what you learn from your experiments, you can unlock sustained growth and success for your business.

1. Evaluating the success of your campaign

Assessing the success of your marketing experiment is vital, and essentially it involves determining if the campaign met its objectives and whether the marketing strategies were effective.

To evaluate the success of your marketing campaigns, you can:

- Compare website visits during the campaign period with traffic from a previous period

- Utilize control groups to measure the effect of the campaign

- Analyze data such as conversion rates and engagement levels

2. Identifying patterns and trends

Recognizing patterns and trends in the data from your marketing experiments can provide valuable insights that can be leveraged to optimize future marketing efforts.

Patterns indicate that many different potential customers are experiencing the same reaction to your campaigns, for better or for worse.

To identify these patterns and trends, you can:

- Visualize customer data

- Combine experiments and data sources

- Conduct market research

- Analyze marketing analytics

By identifying patterns and trends in your marketing experiment data, you can uncover insights that will help you refine your marketing strategies and make data-driven decisions for your future marketing endeavors.

3. Applying learnings to future campaigns

Leveraging the insights gained from your marketing experiment in future campaigns ensures that you can continuously improve and grow the effectiveness of your marketing efforts.

Applying learnings from your marketing experiments, quite simply, involves:

- analyzing the data,

- identifying the successful strategies,

- documenting key learnings, and

- applying these insights to future campaigns

By consistently applying the learnings from your marketing experiments to your future digital marketing efforts , you can ensure that your marketing strategies are data-driven, optimized for success, and always improving.

Now that we’ve talked about the advantages of experiment marketing and the steps involved, let’s dive into real-life cases that showcase the impact of this approach.

By exploring these experiment ideas, you’ll get a clear picture of how you can harness experiment marketing to get superior results.

You can take these insights and apply them to your own marketing experiments, boosting your campaign’s performance and your ROI.

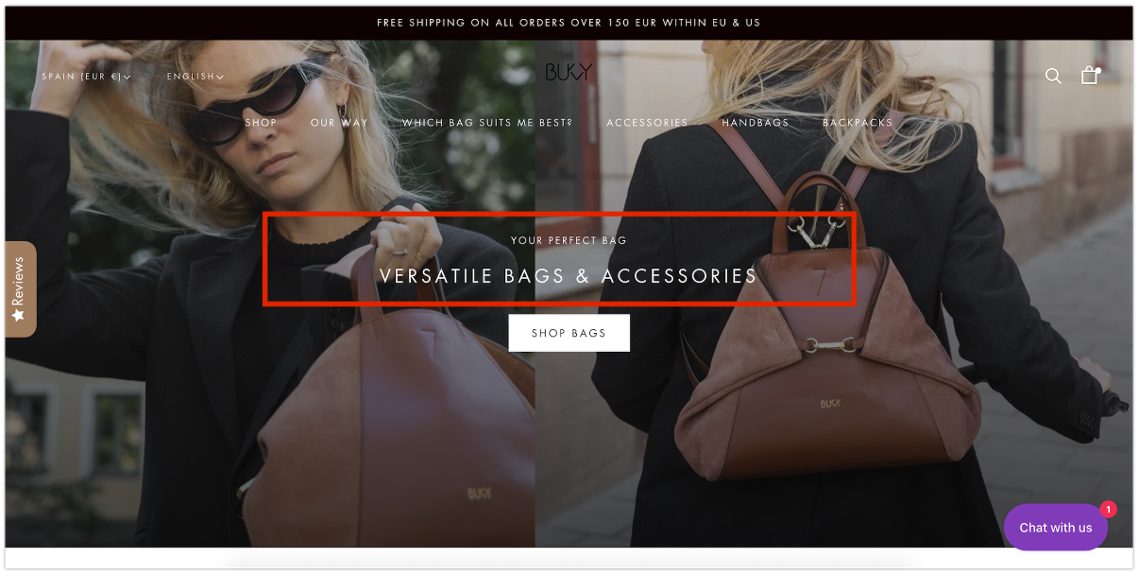

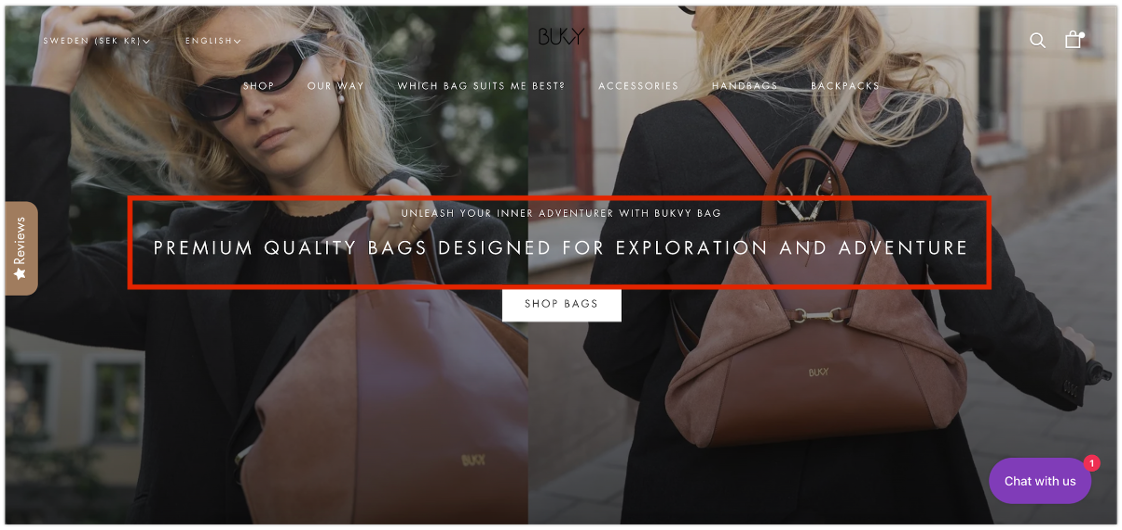

Example 1: Homepage headline experiment

Bukvybag , a Swedish fashion brand selling premium bags, was on a mission to find the perfect homepage headline that would resonate with its website visitors.

They tested multiple headlines with OptiMonk’s Dynamic Content feature to discover which headline option would be most successful with their customers and boost conversion rates.

Take a look at the headlines they experimented with, which all focused on different value propositions.

Original: “ Versatile bags & accessories”

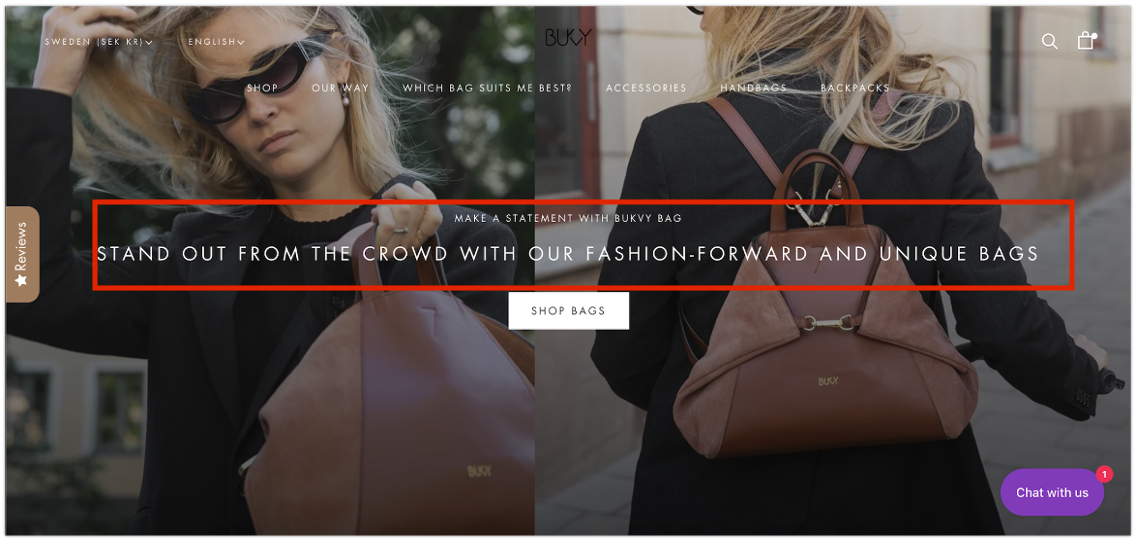

Variant A: “Stand out from the crowd with our fashion-forward and unique bags”

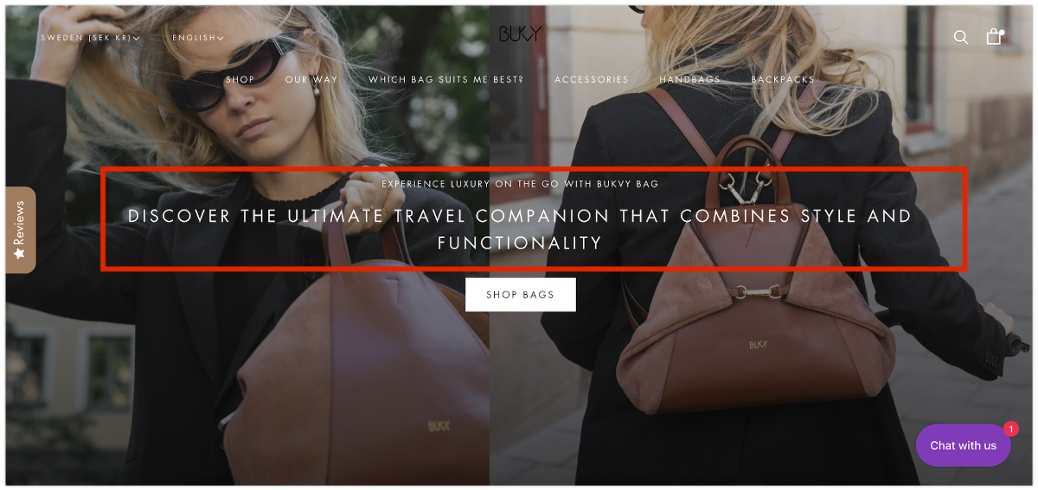

Variant B: “Discover the ultimate travel companion that combines style and functionality”

Variant C: “ Premium quality bags designed for exploration and adventure”

The results? Bukvybag’s conversions shot up by a whopping 45% as a result of this A/B testing!

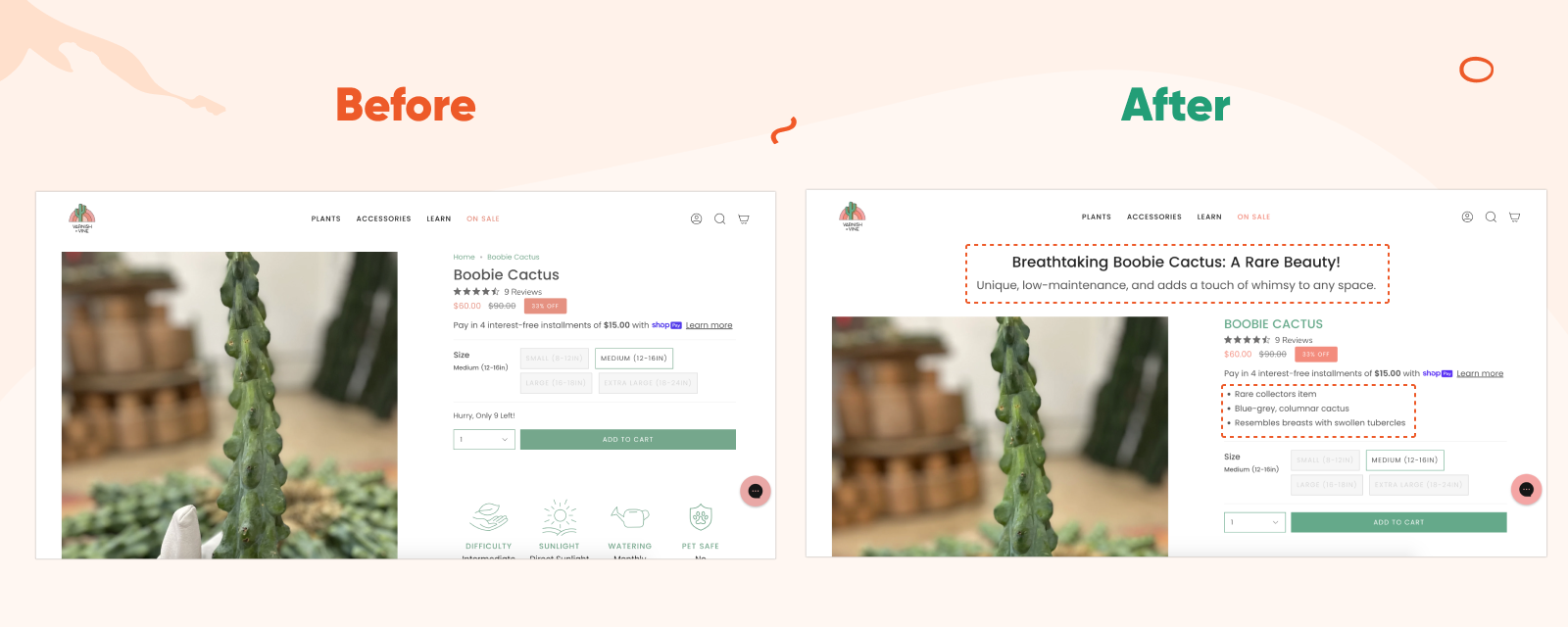

Example 2: Product page experiment

Varnish & Vine , an ecommerce store selling premium plants, discovered that there was a lot they could do to optimize their product pages.

They turned to OptiMonk’s Smart Product Page Optimizer and used the AI-powered tool to achieve a stunning transformation.

First, the tool analyzed their current product pages. Then, it crafted captivating headlines, subheadlines, and lists of benefits for each product page automatically, which were tailored to their audience.

After the changes, the tool ran A/B tests automatically, so the team was able to compare their previous results with their AI-tailored product pages.

The outcome? A 12% boost in orders and a jaw-dropping 43% surge in revenue, all thanks to A/B testing the AI-optimized product pages.

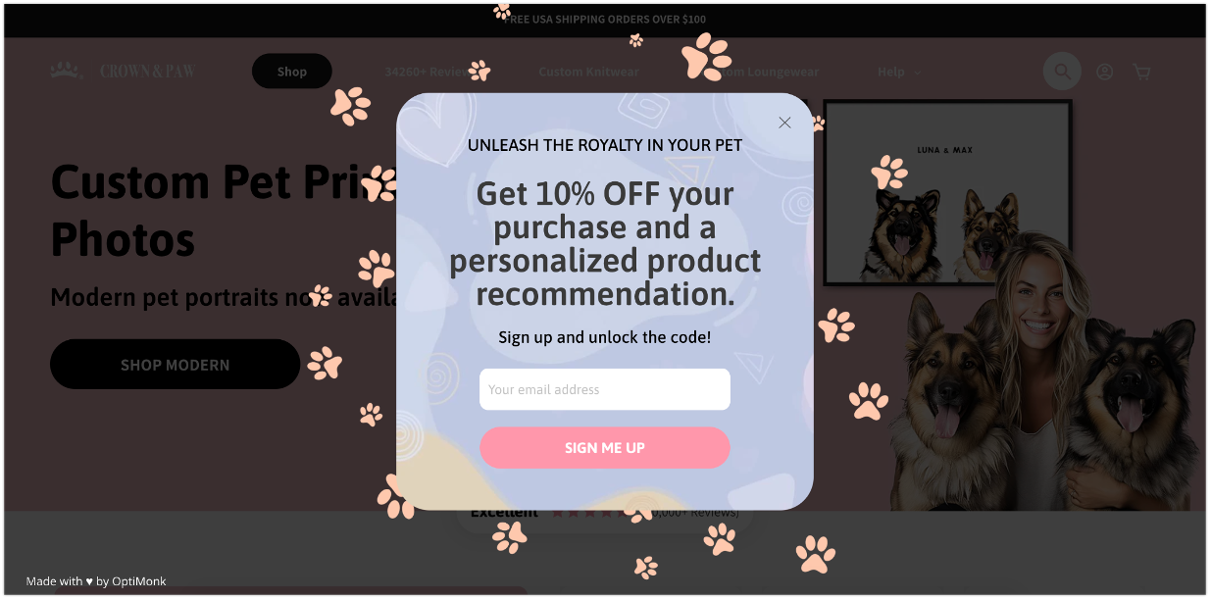

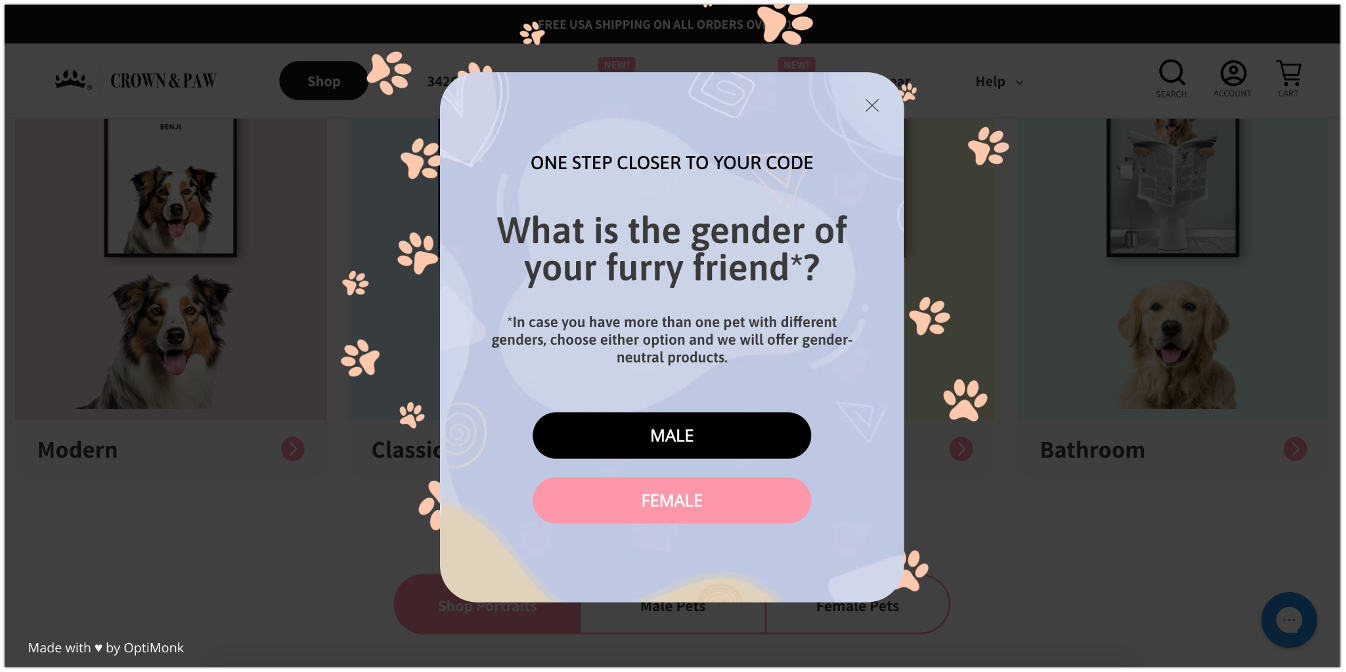

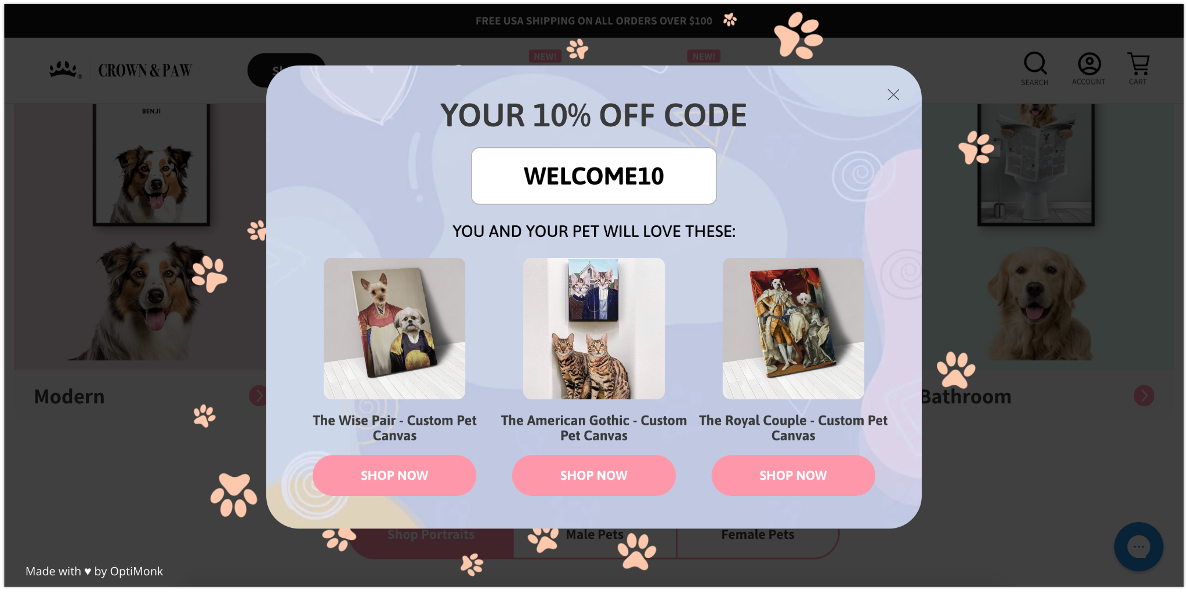

Example 3: Email popup experiment

Crown & Paw , an ecommerce brand selling artistic pet portraits, had been using a simple Klaviyo popup that was underperforming, so they decided to kick it up a notch with a multi-step popup instead.

On the first page, they offered an irresistible discount, and as a plus they promised personalized product recommendations.

In the second step, once visitors had demonstrated that they wanted to grab that 10% off, they asked simple questions to learn about their interests. Here are the questions they asked:

For the 95% who answered their questions, Crown & Paw revealed personalized product recommendations alongside the discount code in the final step.

The result? A 4.03% conversion rate, and a massive 2.5X increase from their previous email popup strategy.

This is tangible proof that creatively engaging your audience can work wonders.

What is an example of a market experiment?

An example of a marketing experiment could involve an e-commerce company testing the impact of offering free shipping on orders over $50 for a month. If they find that the promotion significantly increases total sales revenue and average order value, they may decide to implement the free shipping offer as a permanent strategy.

What is experimental data in marketing?

Experimental data in marketing refers to information collected through tests or experiments designed to investigate specific hypotheses. This data is obtained by running experiments and measuring outcomes to draw conclusions about marketing strategies.

How do you run a marketing experiment?

To run a marketing experiment, start by defining your objective and hypothesis. Then, create control and experimental groups, collect relevant data, analyze the results, and make decisions based on the findings. This iterative process helps refine marketing strategies for better performance.

What are some real-life examples of experiment marketing?

Real-life examples of marketing experiments include A/B testing email subject lines to determine which leads to higher open rates, testing different ad creatives to measure click-through rates, and experimenting with pricing strategies to see how they affect sales and customer behavior.

How to brainstorm and prioritize ideas for marketing experiments?

Start by considering your current objectives and priorities for the upcoming quarter or year. Reflect on your past marketing strategies to identify successful approaches and areas where performance was lacking. Analyze your historical data to gain insights into what has worked previously and what has not. This examination may reveal lingering uncertainties or gaps in your understanding of which strategies are most effective. Use this information to generate new ideas for future experiments aimed at improving performance. After generating a list of potential strategies, prioritize them based on factors such as relevance to your goals, timeliness of implementation, and expected return on investment.

Wrapping up

Experiment marketing is a powerful tool for businesses and marketers looking to optimize their marketing strategies and drive better results.

By designing, implementing, analyzing, and learning from marketing experiments, you can ensure that your marketing efforts are data-driven, focused on the most impactful tactics, and continuously improving.

Want to level up your marketing strategy with a bit of experimenting? Then give OptiMonk a try today by signing up for a free account!

Nikolett Lorincz

You may also like.

The Future of CRO: Conversion Rate Optimization Trends & Predictions for 2025

A Guide to Popup Types: How to Choose Your Popup Type to Maximize ROI

How to Add a Popup on WordPress Easily

- All features

- Book a demo

Partner with us

- Partner program

- Become an affiliate

- Agency program

- Success Stories

- We're hiring

- Tactic Library

- Help center / Support

- Optimonk vs. Optinmonster

- OptiMonk vs. Klaviyo

- OptiMonk vs. Privy

- OptiMonk vs. Dynamic Yield

- OptiMonk vs. Justuno

- OptiMonk vs. Nosto

- OptiMonk vs. VWo

- © OptiMonk. All rights reserved!

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Product updates: September Release 2024

Experiments in Market Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 03 December 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- Torsten Bornemann 4 &

- Stefan Hattula 4

8942 Accesses

2 Citations

The question of how a certain activity (e.g., the intensity of communication activities during the launch of a new product) influences important outcomes (e.g., sales, preferences) is one of the key questions in applied (as well as academic) research in marketing. While such questions may be answered based on observed values of activities and the respective outcomes using survey and/or archival data, it is often not possible to claim that the particular activity has actually caused the observed changes in the outcomes. To demonstrate cause-effect relationships, experiments take a different route. Instead of observing activities, experimentation involves the systematic variation of an independent variable (factor) and the observation of the outcome only. The goal of this chapter is to discuss the parameters relevant to the proper execution of experimental studies. Among others, this involves decisions regarding the number of factors to be manipulated, the measurement of the outcome variable, the environment in which to conduct the experiment, and the recruitment of participants.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital Marketing Research – How to Effectively Utilize Online Research Methods

Market Research

Aaker, D. A., Kumar, V., Day, G. S., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Marketing research . Hoboken: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Albrecht, C.-M., Hattula, S., Bornemann, T., & Hoyer, W. D. (2016). Customer response to interactional service experience: The role of interaction environment. Journal of Service Management, 27 (5), 704–729.

Article Google Scholar

Albrecht, C.-M., Hattula, S., & Lehmann, D. R. (2017). The relationship between consumer shopping stress and purchase abandonment in task-oriented and recreation-oriented consumers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (5), 720–740.

Anderson, E. T., & Simester, D. (2011). A step-by-step guide to smart business experiments. Harvard Business Review, 89 (3), 98–105.

APA. (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57 (12), 1060–1073.

Arnold, V. (2008). Advances in accounting behavioral research . Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Baum, D., & Spann, M. (2011). Experimentelle Forschung im Marketing: Entwicklung und zukünftige Chancen. Marketing – Zeitschrift für Forschung und Praxis, 33 (3), 179–191.

Bearden, W. O., & Etzel, M. (1982). Reference group influence on product and brand decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (April), 183–194.

Benz, M., & Meier, S. (2008). Do people behave in experiments as in the field?—Evidence from donations. Experimental Economics, 11 (3), 268–281.

Berkowitz, L., & Donnerstein, E. (1982). External validity is more than skin deep: Some answers to criticisms of laboratory experiments. American Psychologist, 37 (3), 245–257.

Bornemann, T., & Homburg, C. (2011). Psychological distance and the dual role of price. Journal of Consumer Research, 38 (3), 490–504.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon's mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6 (1), 3–5.

Bullock, J. G., Green, D. P., & Ha, S. E. (2010). Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (don’t expect an easy answer). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98 (4), 550–558.

Camerer, C. F. (2011). The promise and success of lab-field generalizability in experimental economics: A critical reply to levitt and list . Available at SSRN 1977749.

Camerer, C. F., & Hogarth, R. M. (1999). The effects of financial incentives in experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19 (1), 7–42.

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Kuhn, M. A. (2012). Experimental methods: Between-subject and within-subject design. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81 (1), 1–8.

Christian, B. (2012). The a/b test: Inside the technology that’s changing the rules of business. http://www.wired.com/business/2012/04/ff_abtesting . Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences . Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences . Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Collins, L. M., Dziak, J. J., & Li, R. (2009). Design of experiments with multiple independent variables: A resource management perspective on complete and reduced factorial designs. Psychological Methods, 14 (3), 202–224.

Cox, D. R. (1992). Planning of experiments . Hoboken: Wiley.

Dean, A., Voss, D., & Draguljić, D. (2017). Design and analysis of experiments . Cham: Springer.

Deutskens, E., de Ruyter, K., Wetzels, M., & Oosterveld, P. (2004). Response rate and response quality of internet-based surveys: An experimental study. Marketing Letters, 15 (1), 21–36.

Ellis, P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eriksson, L., Johansson, E., Kettaneh-Wold, N., Wikström, C., & Wold, S. (2008). Design of experiments: Principles and applications . Stockholm: Umetrics AB, Umeå Learnways AB.

Evans, A. N., & Rooney, B. J. (2013). Methods in psychological research . Los Angeles: Sage.

Falk, A., & Heckman, J. J. (2009). Lab experiments are a major source of knowledge in the social sciences. Science, 326 (5952), 535–538.

Feldman, J. M., & Lynch, J. G., Jr. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73 (3), 421–435.

Festinger, L. A. (1957). Theory of cognitive dissonance . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., & Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141 (1), 2–18.

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132 (5), 778–822.

Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of mechanical turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26 (3), 213–224.

Greenwald, A. G. (1976). Within-subjects designs: To use or not to use? Psychological Bulletin, 83 (2), 314–320.

Hakel, M. D., Ohnesorge, J. P., & Dunnette, M. D. (1970). Interviewer evaluations of job applicants’ resumes as a function of the qualifications of the immediately preceding applicants: An examination of contrast effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 54 (1, Pt.1), 27–30.

Hansen, R. A. (1980). A self-perception interpretation of the effect of monetary and nonmonetary incentives on mail survey respondent behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (1), 77–83.

Harris, A. D., McGregor, J. C., Perencevich, E. N., Furuno, J. P., Zhu, J., Peterson, D. E., & Finkelstein, J. (2006). The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13 (1), 16–23.

Harrison, G. W., & List, J. A. (2003). What constitutes a field experiment in economics? Working paper . Columbia: Department of Economics, University of South Carolina http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/hoteck/PAPERS/field.pdf . Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Harrison, G. W., & List, J. A. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature, 42 (4), 1009–1055.

Hattula, J. D., Herzog, W., Dahl, D. W., & Reinecke, S. (2015). Managerial empathy facilitates egocentric predictions of consumer preferences. Journal of Marketing Research, 52 (2), 235–252.

Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48 (1), 400–407.

Hegtvedt, K. A. (2014). Ethics and experiments. In M. Webster Jr. & J. Sell (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences (pp. 23–51). Amsterdam/Heidelberg: Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hertwig, R., & Ortmann, A. (2008). Deception in experiments: Revisiting the arguments in its defense. Ethics and Behavior, 18 (1), 59–92.

Hibbeln, M., Jenkins, J. L., Schneider, C., Valacich, J. S., & Weinmann, M. (2017). Inferring negative emotion from mouse cursor movements. MIS Quarterly, 41 (1), 1–21.

Horswill, M. S., & Coster, M. E. (2001). User-controlled photographic animations, photograph-based questions, and questionnaires: Three internet-based instruments for measuring drivers’ risk-taking behavior. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 33 (1), 46–58.

Kalkoff, W., Youngreen, R., Nath, L., & Lovaglia, M. J. (2014). Human participants in laboratory experiments in the social sciences. In M. Webster Jr. & J. Sell (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences (pp. 127–144). Amsterdam/Heidelberg: Elsevier.

Koschate-Fischer, N., & Schandelmeier, S. (2014). A guideline for designing experimental studies in marketing research and a critical discussion of selected problem areas. Journal of Business Economics, 84 (6), 793–826.

Kuipers, K. J., & Hysom, S. J. (2014). Common problems and solutions in experiments. In M. Webster Jr. & J. Sell (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences (pp. 127–144). Amsterdam/Heidelberg: Elsevier.

Larsen, R. J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1999). Measurement issues in emotion research. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 40–60). New York: Russell Sage.

Laugwitz, B. (2001). A web-experiment on colour harmony principles applied to computer user interface design . Lengerich: Pabst Science.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2007). Viewpoint: On the generalizability of lab behaviour to the field. Canadian Journal of Economics, 40 (2), 347–370.

Li, J. Q., Rusmevichientong, P., Simester, D., Tsitsiklis, J. N., & Zoumpoulis, S. I. (2015). The value of field experiments. Management Science, 61 (7), 1722–1740.

List, J. A. (2011). Why economists should conduct field experiments and 14 tips for pulling one off. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25 (3), 3–15.

Lynch, J. G. (1982). On the external validity of experiments in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (3), 225–239.

Lynch, J. G., Marmorstein, H., & Weigold, M. F. (1988). Choices from sets including remembered brands: Use of recalled attributes and prior overall evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (2), 169–184.

Madzharov, A. V., Block, L. G., & Morrin, M. (2015). The cool scent of power: Effects of ambient scent on consumer preferences and choice behavior. Journal of Marketing, 79 (1), 83–96.

Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective . Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Meyvis, T., & Van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2018). Increasing the power of your study by increasing the effect size. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (5), 1157–1173.

Mitra, A., & Lynch, J. G. (1995). Toward a reconciliation of market power and information theories of advertising effects on price elasticity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (4), 644–659.

Montgomery, D. C. (2009). Design and analysis of experiments . New York: Wiley.

Morales, A. C., Amir, O., & Lee, L. (2017). Keeping it real in experimental research—Understanding when, where, and how to enhance realism and measure consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (2), 465–476.

Morton, R. B., & Williams, K. C. (2010). Experimental political science and the study of causality: From nature to the lab . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Myers, H., & Lumbers, M. (2008). Understanding older shoppers: A phenomenological investigation. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25 (5), 294–301.

Nielsen, J. (2000). Why you only need to test with 5 users. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-you-only-need-to-test-with-5-users . Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Nielsen, J. (2012). How many test users in a usability study. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users . Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Nisbett, R. E. (2015). Mindware: Tools for smart thinking . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Nordhielm, C. L. (2002). The influence of level of processing on advertising repetition effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (3), 371–382.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45 (4), 867–872.

Pascual-Leone, A., Singh, T., & Scoboria, A. (2010). Using deception ethically: Practical research guidelines for researchers and reviewers. Canadian Psychology, 51 (4), 241–248.

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70 , 153–163.

Perdue, B. C., & Summers, J. O. (1986). Checking the success of manipulations in marketing experiments. Journal of Marketing Research, 23 (4), 317–326.

Pirlott, A. G., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2016). Design approaches to experimental mediation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66 (September), 29–38.

Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Cihangir, S. (2001). Quality of decision making and group norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80 (6), 918–930.

Rashotte, L. S., Webster, M., & Whitmeyer, J. M. (2005). Pretesting experimental instructions. Sociological Methodology, 35 (1), 151–175.

Reips, U.-D. (2002). Standards for internet-based experimenting. Experimental Psychology, 49 (4), 243–256.

Remler, D. K., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2010). Research methods in practice: Strategies for description and causation . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Reynolds, N., Diamantopoulos, A., & Schlegelmilch, B. (1993). Pretesting in questionnaire design: A review of the literature and suggestions for further research. Journal of the Market Research Society, 35 (2), 171–183.

Robertson, D. H., & Bellenger, D. N. (1978). A new method of increasing mail survey responses: Contributions to charity. Journal of Marketing Research, 15 (4), 632–633.

Sawyer, A. G., & Ball, A. D. (1981). Statistical power and effect size in marketing research. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (3), 275–290.

Sawyer, A. G., Lynch, J. G., & Brinberg, D. L. (1995). A bayesian analysis of the information value of manipulation and confounding checks in theory tests. Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (4), 581–595.

Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (3), 515–530.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sieber, J. E. (1992). Planning ethically responsible research: A guide for students and internal review boards . Newbury Park: Sage.

Simester, D. (2017). Field experiments in marketing. In E. Duflo & A. Banerjee (Eds.), Handbook of economic field experiments Amsterdam: North-Holland (pp. 465–497).

Singer, E., & Couper, M. P. (2008). Do incentives exert undue influence on survey participation? Experimental evidence. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 3 (3), 49–56.

Singer, E., Van Hoewyk, J., Gebler, N., & McGonagle, K. (1999). The effect of incentives on response rates in interviewer-mediated surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 15 (2), 217–230.

Smith, V. L., & Walker, J. M. (1993). Rewards, experience and decision cost in first price auctions. Economic Inquiry, 31 (2), 237–244.

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89 (6), 845–851.

Stuart, E. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2007). Best practices in quasi-experimental designs: Matching methods for causal inference. In J. Osborne (Ed.), Best practices in quantitative methods (pp. 155–176). New York. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thye, S. R. (2014). Logical and philosophical foundations of experimental research in the social sciences. In M. Webster Jr. & J. Sell (Eds.), Laboratory experiments in the social sciences (pp. 53–82). Amsterdam/Heidelberg: Elsevier.

Trafimow, D., Leonhardt, J. M., Niculescu, M., & Payne, C. (2016). A method for evaluating and selecting field experiment locations. Marketing Letters, 7 (3), 437–447.

Trafimow, D., & Rice, S. (2009). What if social scientists had reviewed great scientific works of the past? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4 (1), 65–78.

Verlegh, P. W. J., Schifferstein, H. N. J., & Wittink, D. R. (2002). Range and number-of-levels effects in derived and stated measures of attribute importance. Marketing Letters, 13 (1), 41–52.

Völckner, F., & Hofmann, J. (2007). The price-perceived quality relationship: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its determinants. Marketing Letters, 18 (3), 181–196.

Wetzel, C. G. (1977). Manipulation checks: A reply to kidd. Representative Research in Social Psychology, 8 (2), 88–93.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering baron and kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37 (2), 197–206.

Zikmund, W., & Babin, B. (2006). Exploring marketing research . Mason: Thomson South-Western.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Marketing, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany

Torsten Bornemann & Stefan Hattula

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Torsten Bornemann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Business-to-Business Marketing, Sales, and Pricing, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Christian Homburg

Department of Marketing & Sales Research Group, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany

Martin Klarmann

Marketing & Sales Department, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Arnd Vomberg

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Bornemann, T., Hattula, S. (2022). Experiments in Market Research. In: Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A. (eds) Handbook of Market Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57413-4_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57413-4_2

Published : 03 December 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-57411-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-57413-4

eBook Packages : Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to Conduct the Perfect Marketing Experiment [+ Examples]

Updated: January 11, 2022

Published: February 29, 2012

After months of hard work, multiple coffee runs, and navigation of the latest industry changes, you've finally finished your next big marketing campaign.

Complete with social media posts, PPC ads, and a sparkly new logo, it's the campaign of a lifetime.

But how do you know it will be effective?

While there's no sure way to know if your campaign will turn heads, there is a way to gauge whether those new aspects of your strategy will be effective.

If you want to know if certain components of your campaign are worth the effort, consider conducting a marketing experiment.

Marketing experiments give you a projection of how well marketing methods will perform before you implement them. Keep reading to learn how to conduct an experiment and discover the types of experiments you can run.

What are marketing experiments?

A marketing experiment is a form of market research in which your goal is to discover new strategies for future campaigns or validate existing ones.

For instance, a marketing team might create and send emails to a small segment of their readership to gauge engagement rates, before adding them to a campaign.

It's important to note that a marketing experiment isn't synonymous with a marketing test. Marketing experiments are done for discovery, while a test confirms theories.

Why should you run a marketing experiment?

Think of running a marketing experiment as taking out an insurance policy on future marketing efforts. It’s a way to minimize your risk and ensure that your efforts are in line with your desired results.

Imagine spending hours searching for the perfect gift. You think you’ve found the right one, only to realize later that it doesn’t align with your recipient’s taste or interests. Gifts come with receipts but there’s no money-back guarantee when it comes to marketing campaigns.

An experiment will help you better understand your audience, which in turn will enable you to optimize your strategy for a stronger performance.

How to Conduct Marketing Experiments

- Brainstorm and prioritize experiment ideas.

- Find one idea to focus on.

- Make a hypothesis.

- Collect research.

- Select your metrics.

- Execute the experiment.

- Analyze the results.

Performing a marketing experiment involves doing research, structuring the experiment, and analyzing the results. Let's go through the seven steps necessary to conduct a marketing experiment.

1. Brainstorm and prioritize experiment ideas.

The first thing you should do when running a marketing experiment is start with a list of ideas.

Don’t know where to start? Look at your current priorities. What goals are you focusing on for the next quarter or the next year?

From there, analyze historical data. Were your past strategies worked in the past and what were your low performers?

As you dig into your data, you may find that you still have unanswered questions about which strategies may be most effective. From there, you can identify potential reasons behind low performance and start brainstorming some ideas for future experiments.

Then, you can rank your ideas by relevance, timeliness, and return on investment so that you know which ones to tackle first.

Keep a log of your ideas online, like Google Sheets , for easy access and collaboration.

2. Find one idea to focus on.

Now that you have a log of ideas, you can pick one to focus on.

Ideally, you organize your list based on current priorities. As such, as the business evolves, your priorities may change and affect how you rank your ideas.

Say you want to increase your subscriber count by 1,000 over the next quarter. You’re several weeks away from the start of the quarter and after looking through your data, you notice that users don’t convert once they land on your landing page.

Your landing page would be a great place to start your experiment. It’s relevant to your current goals and will yield a large return on your investment.

Even unsuccessful experiments, meaning those that do not yield expected results, are incredibly valuable as they help you to better understand your audience.

3. Make a hypothesis.

Hypotheses aren't just for science projects. When conducting a marketing experiment, the first step is to make a hypothesis you're curious to test.

A good hypothesis for your landing page can be any of the following:

- Changing the CTA copy from "Get Started" to "Join Our Community" will increase sign-ups by 5%.

- Removing the phone number field from the landing page form will increase the form completion rate by 25%.

- Adding a security badge on the landing page will increase the conversion rate by 10%.

This is a good hypothesis because you can prove or disprove it, it isn't subjective, and has a clear measurement of achievement.

A not-so-good hypothesis will tackle several elements at once, be unspecific and difficult to measure. For example: "By updating the photos, CTA, and copy on the landing page, we should get more sign-ups.

Here’s why this doesn’t work: Testing several variables at once is a no-go when it comes to experimenting because it will be unclear which change(s) impacted the results. The hypothesis also doesn’t mention how the elements would be changed nor what would constitute a win.

Formulating a hypothesis takes some practice, but it’s the key to building a robust experiment.

4. Collect research.

After creating your hypothesis, begin to gather research. Doing this will give you background knowledge about experiments that have already been conducted and get an idea of possible outcomes.

Researching your experiment can help you modify your hypothesis if needed.

Say your hypothesis is, "Changing the CTA copy from "Get Started" to "Join Our Community" will increase sign-ups by 5%." You may conduct more market research to validate your ideas surrounding your user persona and if they will resonate better with a community-focused approach.

It would be helpful to look at your competitors’ landing pages and see which strategies they’re using during your research.

5. Select your metrics.

Once you've collected the research, you can choose which avenue you will take and what metrics to measure.

For instance, if you’re running an email subject line experiment, the open rate is the right metric to track.

For a landing page, you’ll likely be tracking the number of submissions during the testing period. If you’re experimenting on a blog, you might focus on the average time on page.

It all depends on what you’re tracking and the question you want to answer with your experiment.

6. Execute the experiment.

Now it's time to create and perform the experiment.

Depending on what you’re testing, this may be a cross-functional project that requires collaborating with other teams.

For instance, if you’re testing a new landing page CTA, you’ll likely need a copywriter or UX writer.

Everyone involved in this experiment should know:

- The hypothesis and goal of the experiment

- The timeline and duration

- The metrics you’ll track

7. Analyze the results.

Once you've run the experiment, collect and analyze the results.

You want to gather enough data for statistical significance .

Use the metrics you've decided upon in the second step and conclude if your hypothesis was correct or not.

The prime indicators for success will be the metrics you chose to focus on.

For instance, for the landing page example, did sign-ups increase as a result of the new copy? If the conversion rate met or went above the goal, the experiment would be considered successful and one you should implement.

If it’s unsuccessful, your team should discuss the potential reasons why and go back to the drawing board. This experiment may spark ideas of new elements to test.

Now that you know how to conduct a marketing experiment, let's go over a few different ways to run them.

Marketing Experiment Examples

There are many types of marketing experiments you can conduct with your team. These tests will help you determine how aspects of your campaign will perform before you roll out the campaign as a whole.

A/B testing is one of the popular ways to marketing in which two versions of a webpage, email, or social post are presented to an audience (randomly divided in half). This test determines which version performs better with your audience.

This method is useful because you can better understand the preferences of users who will be using your product.

Find below the types of experiments you can run.

Your website is arguably your most important digital asset. As such, you’ll want to make sure it’s performing well.

If your bounce rate is high, the average time on page is low, or your visitors aren’t navigating your site in the way you’d like, it may be time to run an experiment.

2. Landing Pages

Landing pages are used to convert visitors into leads. If your landing page is underperforming, running an experiment can yield high returns.

The great thing about running a test on a landing page is that there are typically only a few elements to test: your background image, your copy, form, and CTA .

Experimenting with different CTAs can improve the number of people who engage with your content.

For instance, instead of using "Buy Now!" to pull customers in, why not try, "Learn more."

You can also test different colors of CTAs as opposed to the copy.

4. Paid Media Campaigns

There are so many different ways to experiment with ads.

Not only can you test ads on various platforms to see which ones reach your audience the best, but you can also experiment with the type of ad you create.

As a big purveyor of GIFs in the workplace, animating ads are a great way to catch the attention of potential customers. Those may work great for your brand.

You may also find that short videos or static images work better.

Additionally, you might run different types of copy with your ads to see which language compels your audience to click.

To maximize your return on ad spend (ROAS), run experiments on your paid media campaigns.

4. Social Media Platforms

Is there a social media site you're not using? For instance, lifestyle brands might prioritize Twitter and Instagram, but implementing Pinterest opens the door for an untapped audience.

You might consider testing which hashtags or visuals you use on certain social media sites to see how well they perform.

The more you use certain social platforms, the more iterations you can create based on what your audience responds to.

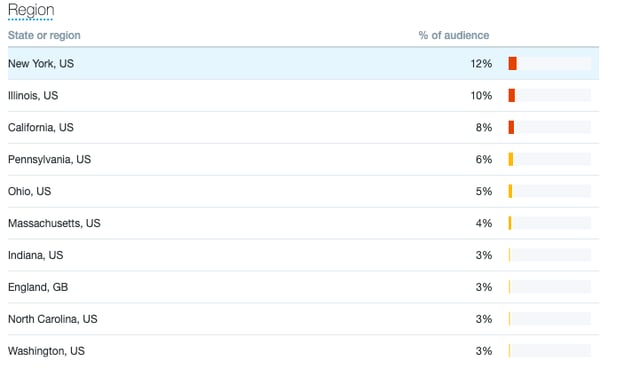

You might even use your social media analytics to determine which countries or regions you should focus on — for instance, my Twitter Analytics , below, demonstrates where most of my audience resides.

If alternatively, I saw most of my audience came from India, I might need to alter my social strategy to ensure I catered to India's time zone.

When experimenting with different time zones, consider making content specific to the audience you're trying to reach.

Your copy — the text used in marketing campaigns to persuade, inform, or entertain an audience — can make or break your marketing strategy .

If you’re not in touch with your audience, your message may not resonate. Perhaps you haven’t fleshed out your user persona or you’ve conducted limited research.

As such, it may be helpful to test what tone and concepts your audience enjoys. A/B testing is a great way to do this, you can also run surveys and focus groups to better understand your audience.

Email marketing continues to be one of the best digital channels to grow and nurture your leads.

If you have low open or high unsubscribe rates, it's worth running experiments to see what your audience will respond best to.

Perhaps your subject lines are too impersonal or unspecific. Or the content in your email is too long.

By playing around with various elements in your email, you can figure out the right strategy to reach your audience.

Ultimately, marketing experiments are a cost-effective way to get a picture of how new content ideas will work in your next campaign, which is critical for ensuring you continue to delight your audience.

Editor's Note: This post was originally published in December 2019 and has been updated for comprehensiveness.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

How to Determine Your A/B Testing Sample Size & Time Frame

How The Hustle Got 43,876 More Clicks

How to Do A/B Testing: 15 Steps for the Perfect Split Test

What Most Brands Miss With User Testing (That Costs Them Conversions)

Multivariate Testing: How It Differs From A/B Testing

How to A/B Test Your Pricing (And Why It Might Be a Bad Idea)

11 A/B Testing Examples From Real Businesses

15 of the Best A/B Testing Tools for 2024

These 20 A/B Testing Variables Measure Successful Marketing Campaigns

![market experimental method How to Understand & Calculate Statistical Significance [Example]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/FEATURED%20IMAGE-Nov-22-2022-06-25-18-4060-PM.png)

How to Understand & Calculate Statistical Significance [Example]

Learn more about A/B and how to run better tests.

The weekly email to help take your career to the next level. No fluff, only first-hand expert advice & useful marketing trends.

Must enter a valid email

We're committed to your privacy. HubSpot uses the information you provide to us to contact you about our relevant content, products, and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

You've been subscribed

IMAGES

VIDEO