Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis)

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

There are about seven thousand languages heard around the world – they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. As you know, language plays a significant role in our lives.

But one intriguing question is – can it actually affect how we think?

It is widely thought that reality and how one perceives the world is expressed in spoken words and are precisely the same as reality.

That is, perception and expression are understood to be synonymous, and it is assumed that speech is based on thoughts. This idea believes that what one says depends on how the world is encoded and decoded in the mind.

However, many believe the opposite.

In that, what one perceives is dependent on the spoken word. Basically, that thought depends on language, not the other way around.

What Is The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?

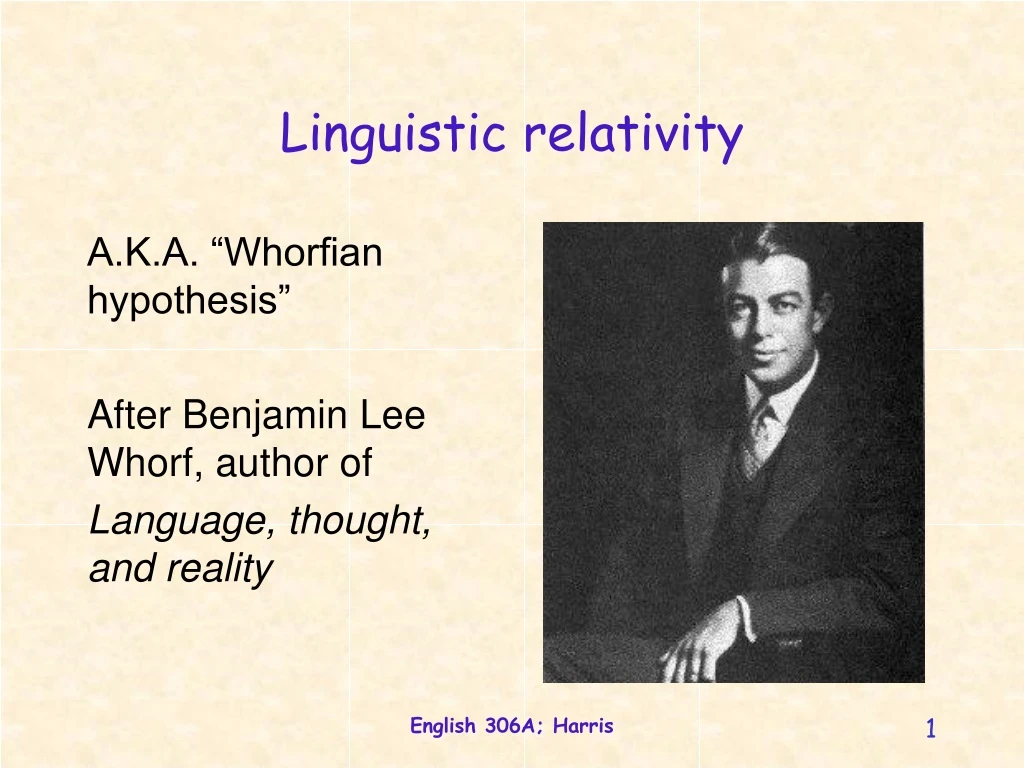

Twentieth-century linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf are known for this very principle and its popularization. Their joint theory, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or, more commonly, the Theory of Linguistic Relativity, holds great significance in all scopes of communication theories.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that the grammatical and verbal structure of a person’s language influences how they perceive the world. It emphasizes that language either determines or influences one’s thoughts.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that people experience the world based on the structure of their language, and that linguistic categories shape and limit cognitive processes. It proposes that differences in language affect thought, perception, and behavior, so speakers of different languages think and act differently.

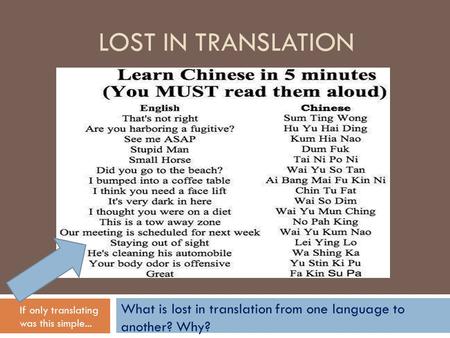

For example, different words mean various things in other languages. Not every word in all languages has an exact one-to-one translation in a foreign language.

Because of these small but crucial differences, using the wrong word within a particular language can have significant consequences.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is sometimes called “linguistic relativity” or the “principle of linguistic relativity.” So while they have slightly different names, they refer to the same basic proposal about the relationship between language and thought.

How Language Influences Culture

Culture is defined by the values, norms, and beliefs of a society. Our culture can be considered a lens through which we undergo the world and develop a shared meaning of what occurs around us.

The language that we create and use is in response to the cultural and societal needs that arose. In other words, there is an apparent relationship between how we talk and how we perceive the world.

One crucial question that many intellectuals have asked is how our society’s language influences its culture.

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir and his then-student Benjamin Whorf were interested in answering this question.

Together, they created the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that our thought processes predominantly determine how we look at the world.

Our language restricts our thought processes – our language shapes our reality. Simply, the language that we use shapes the way we think and how we see the world.

Since the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis theorizes that our language use shapes our perspective of the world, people who speak different languages have different views of the world.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a Yale University graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir, who was considered the father of American linguistic anthropology.

Sapir was responsible for documenting and recording the cultures and languages of many Native American tribes disappearing at an alarming rate. He and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between language and culture.

Anthropologists like Sapir need to learn the language of the culture they are studying to understand the worldview of its speakers truly. Whorf believed that the opposite is also true, that language affects culture by influencing how its speakers think.

His hypothesis proposed that the words and structures of a language influence how its speaker behaves and feels about the world and, ultimately, the culture itself.

Simply put, Whorf believed that you see the world differently from another person who speaks another language due to the specific language you speak.

Human beings do not live in the matter-of-fact world alone, nor solitary in the world of social action as traditionally understood, but are very much at the pardon of the certain language which has become the medium of communication and expression for their society.

To a large extent, the real world is unconsciously built on habits in regard to the language of the group. We hear and see and otherwise experience broadly as we do because the language habits of our community predispose choices of interpretation.

Studies & Examples

The lexicon, or vocabulary, is the inventory of the articles a culture speaks about and has classified to understand the world around them and deal with it effectively.

For example, our modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some vehicle – cars, buses, trucks, SUVs, trains, etc. We, therefore, have thousands of words to talk about and mention, including types of models, vehicles, parts, or brands.

The most influential aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the dictionary of its language. Among the societies living on the islands in the Pacific, fish have significant economic and cultural importance.

Therefore, this is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival.

For example, there are over 1,000 fish species in Palau, and Palauan fishers knew, even long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them – far more than modern biologists know today.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with many Native American languages, including Hopi. He discovered that the Hopi language is quite different from English in many ways, especially regarding time.

Western cultures and languages view times as a flowing river that carries us continuously through the present, away from the past, and to the future.

Our grammar and system of verbs reflect this concept with particular tenses for past, present, and future.

We perceive this concept of time as universal in that all humans see it in the same way.

Although a speaker of Hopi has very different ideas, their language’s structure both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. Seemingly, the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense; instead, they divide the world into manifested and unmanifest domains.

The manifested domain consists of the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past, and the future; the unmanifest domain consists of the remote past and the future and the world of dreams, thoughts, desires, and life forces.

Also, there are no words for minutes, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English-speaking world when it came to being on time for their job or other affairs.

It is due to the simple fact that this was not how they had been conditioned to behave concerning time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

Today, it is widely believed that some aspects of perception are affected by language.

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis derives from the idea that if a person’s language has no word for a specific concept, then that person would not understand that concept.

Honestly, the idea that a mother tongue can restrict one’s understanding has been largely unaccepted. For example, in German, there is a term that means to take pleasure in another person’s unhappiness.

While there is no translatable equivalent in English, it just would not be accurate to say that English speakers have never experienced or would not be able to comprehend this emotion.

Just because there is no word for this in the English language does not mean English speakers are less equipped to feel or experience the meaning of the word.

Not to mention a “chicken and egg” problem with the theory.

Of course, languages are human creations, very much tools we invented and honed to suit our needs. Merely showing that speakers of diverse languages think differently does not tell us whether it is the language that shapes belief or the other way around.

Supporting Evidence

On the other hand, there is hard evidence that the language-associated habits we acquire play a role in how we view the world. And indeed, this is especially true for languages that attach genders to inanimate objects.

There was a study done that looked at how German and Spanish speakers view different things based on their given gender association in each respective language.

The results demonstrated that in describing things that are referred to as masculine in Spanish, speakers of the language marked them as having more male characteristics like “strong” and “long.” Similarly, these same items, which use feminine phrasings in German, were noted by German speakers as effeminate, like “beautiful” and “elegant.”

The findings imply that speakers of each language have developed preconceived notions of something being feminine or masculine, not due to the objects” characteristics or appearances but because of how they are categorized in their native language.

It is important to remember that the Theory of Linguistic Relativity (Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) also successfully achieves openness. The theory is shown as a window where we view the cognitive process, not as an absolute.

It is set forth to look at a phenomenon differently than one usually would. Furthermore, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is very simple and logically sound. Understandably, one’s atmosphere and culture will affect decoding.

Likewise, in studies done by the authors of the theory, many Native American tribes do not have a word for particular things because they do not exist in their lives. The logical simplism of this idea of relativism provides parsimony.

Truly, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis makes sense. It can be utilized in describing great numerous misunderstandings in everyday life. When a Pennsylvanian says “yuns,” it does not make any sense to a Californian, but when examined, it is just another word for “you all.”

The Linguistic Relativity Theory addresses this and suggests that it is all relative. This concept of relativity passes outside dialect boundaries and delves into the world of language – from different countries and, consequently, from mind to mind.

Is language reality honestly because of thought, or is it thought which occurs because of language? The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis very transparently presents a view of reality being expressed in language and thus forming in thought.

The principles rehashed in it show a reasonable and even simple idea of how one perceives the world, but the question is still arguable: thought then language or language then thought?

Modern Relevance

Regardless of its age, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or the Linguistic Relativity Theory, has continued to force itself into linguistic conversations, even including pop culture.

The idea was just recently revisited in the movie “Arrival,” – a science fiction film that engagingly explores the ways in which an alien language can affect and alter human thinking.

And even if some of the most drastic claims of the theory have been debunked or argued against, the idea has continued its relevance, and that does say something about its importance.

Hypotheses, thoughts, and intellectual musings do not need to be totally accurate to remain in the public eye as long as they make us think and question the world – and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does precisely that.

The theory does not only make us question linguistic theory and our own language but also our very existence and how our perceptions might shape what exists in this world.

There are generalities that we can expect every person to encounter in their day-to-day life – in relationships, love, work, sadness, and so on. But thinking about the more granular disparities experienced by those in diverse circumstances, linguistic or otherwise, helps us realize that there is more to the story than ours.

And beautifully, at the same time, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis reiterates the fact that we are more alike than we are different, regardless of the language we speak.

Isn’t it just amazing that linguistic diversity just reveals to us how ingenious and flexible the human mind is – human minds have invented not one cognitive universe but, indeed, seven thousand!

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What is the Sapir‐Whorf hypothesis?. American anthropologist, 86(1), 65-79.

Whorf, B. L. (1952). Language, mind, and reality. ETC: A review of general semantics, 167-188.

Whorf, B. L. (1997). The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language. In Sociolinguistics (pp. 443-463). Palgrave, London.

Whorf, B. L. (2012). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT press.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

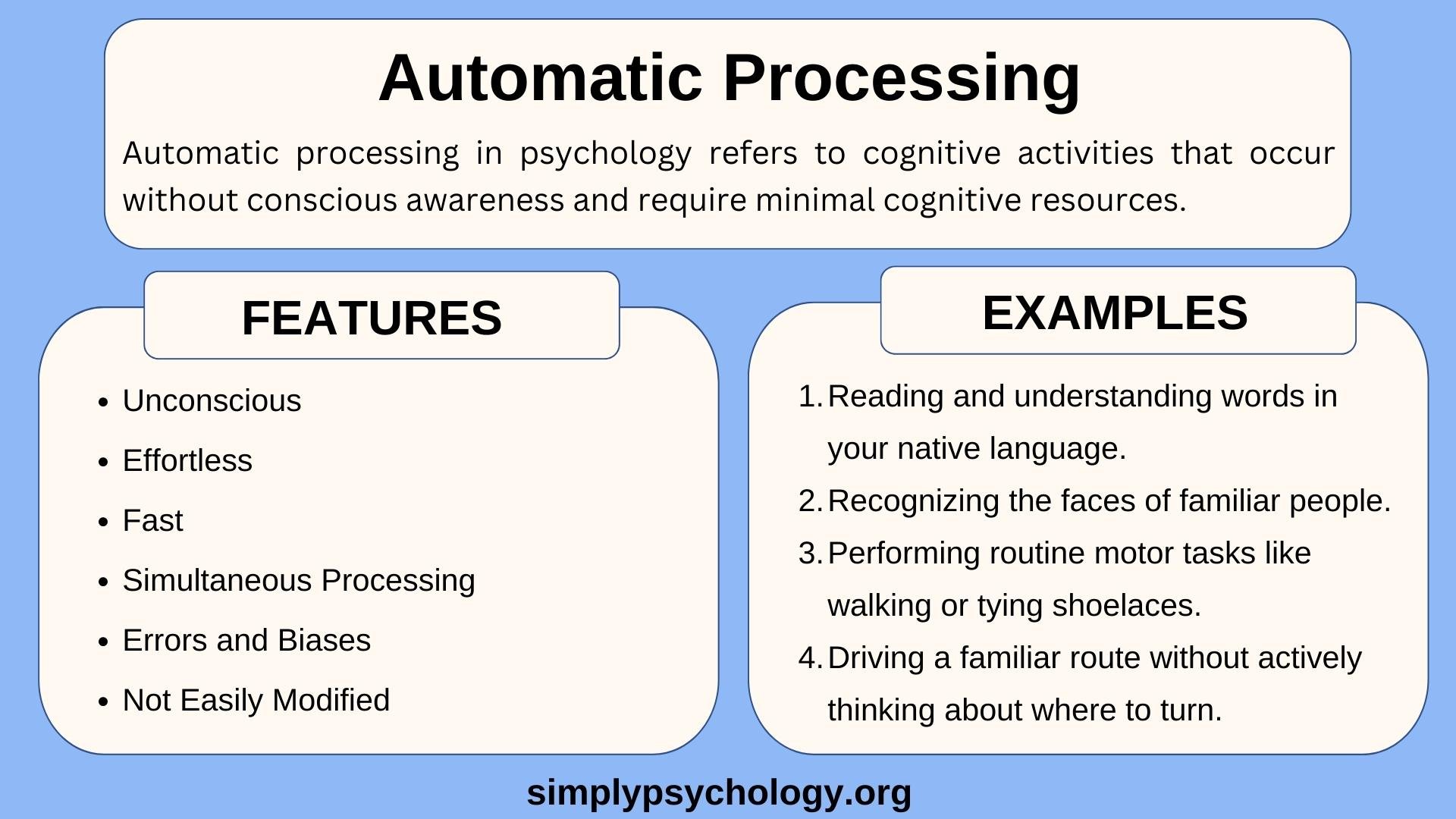

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

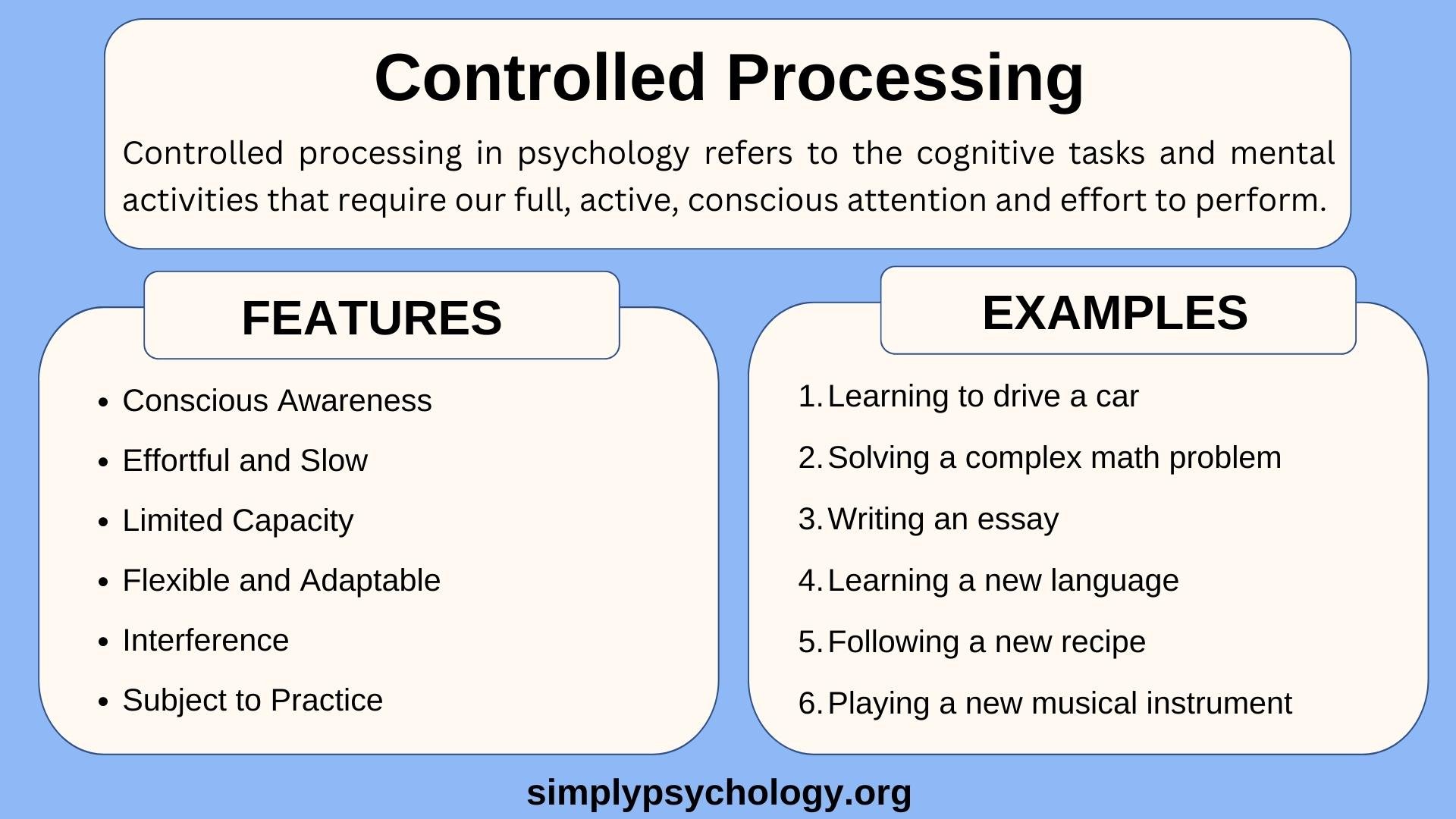

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: How Language Influences How We Express Ourselves

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

What to Know About the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Real-world examples of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativity in psychology.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can influence their worldview, thought, and even how they experience and understand the world.

While more extreme versions of the hypothesis have largely been discredited, a growing body of research has demonstrated that language can meaningfully shape how we understand the world around us and even ourselves.

Keep reading to learn more about linguistic relativity, including some real-world examples of how it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

The hypothesis is named after anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While the hypothesis is named after them both, the two never actually formally co-authored a coherent hypothesis together.

This Hypothesis Aims to Figure Out How Language and Culture Are Connected

Sapir was interested in charting the difference in language and cultural worldviews, including how language and culture influence each other. Whorf took this work on how language and culture shape each other a step further to explore how different languages might shape thought and behavior.

Since then, the concept has evolved into multiple variations, some more credible than others.

Linguistic Determinism Is an Extreme Version of the Hypothesis

Linguistic determinism, for example, is a more extreme version suggesting that a person’s perception and thought are limited to the language they speak. An early example of linguistic determinism comes from Whorf himself who argued that the Hopi people in Arizona don’t conjugate verbs into past, present, and future tenses as English speakers do and that their words for units of time (like “day” or “hour”) were verbs rather than nouns.

From this, he concluded that the Hopi don’t view time as a physical object that can be counted out in minutes and hours the way English speakers do. Instead, Whorf argued, the Hopi view time as a formless process.

This was then taken by others to mean that the Hopi don’t have any concept of time—an extreme view that has since been repeatedly disproven.

There is some evidence for a more nuanced version of linguistic relativity, which suggests that the structure and vocabulary of the language you speak can influence how you understand the world around you. To understand this better, it helps to look at real-world examples of the effects language can have on thought and behavior.

Different Languages Express Colors Differently

Color is one of the most common examples of linguistic relativity. Most known languages have somewhere between two and twelve color terms, and the way colors are categorized varies widely. In English, for example, there are distinct categories for blue and green .

Blue and Green

But in Korean, there is one word that encompasses both. This doesn’t mean Korean speakers can’t see blue, it just means blue is understood as a variant of green rather than a distinct color category all its own.

In Russian, meanwhile, the colors that English speakers would lump under the umbrella term of “blue” are further subdivided into two distinct color categories, “siniy” and “goluboy.” They roughly correspond to light blue and dark blue in English. But to Russian speakers, they are as distinct as orange and brown .

In one study comparing English and Russian speakers, participants were shown a color square and then asked to choose which of the two color squares below it was the closest in shade to the first square.

The test specifically focused on varying shades of blue ranging from “siniy” to “goluboy.” Russian speakers were not only faster at selecting the matching color square but were more accurate in their selections.

The Way Location Is Expressed Varies Across Languages

This same variation occurs in other areas of language. For example, in Guugu Ymithirr, a language spoken by Aboriginal Australians, spatial orientation is always described in absolute terms of cardinal directions. While an English speaker would say the laptop is “in front of” you, a Guugu Ymithirr speaker would say it was north, south, west, or east of you.

As a result, Aboriginal Australians have to be constantly attuned to cardinal directions because their language requires it (just as Russian speakers develop a more instinctive ability to discern between shades of what English speakers call blue because their language requires it).

So when you ask a Guugu Ymithirr speaker to tell you which way south is, they can point in the right direction without a moment’s hesitation. Meanwhile, most English speakers would struggle to accurately identify South without the help of a compass or taking a moment to recall grade school lessons about how to find it.

The concept of these cardinal directions exists in English, but English speakers aren’t required to think about or use them on a daily basis so it’s not as intuitive or ingrained in how they orient themselves in space.

Just as with other aspects of thought and perception, the vocabulary and grammatical structure we have for thinking about or talking about what we feel doesn’t create our feelings, but it does shape how we understand them and, to an extent, how we experience them.

Words Help Us Put a Name to Our Emotions

For example, the ability to detect displeasure from a person’s face is universal. But in a language that has the words “angry” and “sad,” you can further distinguish what kind of displeasure you observe in their facial expression. This doesn’t mean humans never experienced anger or sadness before words for them emerged. But they may have struggled to understand or explain the subtle differences between different dimensions of displeasure.

In one study of English speakers, toddlers were shown a picture of a person with an angry facial expression. Then, they were given a set of pictures of people displaying different expressions including happy, sad, surprised, scared, disgusted, or angry. Researchers asked them to put all the pictures that matched the first angry face picture into a box.

The two-year-olds in the experiment tended to place all faces except happy faces into the box. But four-year-olds were more selective, often leaving out sad or fearful faces as well as happy faces. This suggests that as our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

But some research suggests the influence is not limited to just developing a wider vocabulary for categorizing emotions. Language may “also help constitute emotion by cohering sensations into specific perceptions of ‘anger,’ ‘disgust,’ ‘fear,’ etc.,” said Dr. Harold Hong, a board-certified psychiatrist at New Waters Recovery in North Carolina.

As our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

Words for emotions, like words for colors, are an attempt to categorize a spectrum of sensations into a handful of distinct categories. And, like color, there’s no objective or hard rule on where the boundaries between emotions should be which can lead to variation across languages in how emotions are categorized.

Emotions Are Categorized Differently in Different Languages

Just as different languages categorize color a little differently, researchers have also found differences in how emotions are categorized. In German, for example, there’s an emotion called “gemütlichkeit.”

While it’s usually translated as “cozy” or “ friendly ” in English, there really isn’t a direct translation. It refers to a particular kind of peace and sense of belonging that a person feels when surrounded by the people they love or feel connected to in a place they feel comfortable and free to be who they are.

Harold Hong, MD, Psychiatrist

The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion.

You may have felt gemütlichkeit when staying up with your friends to joke and play games at a sleepover. You may feel it when you visit home for the holidays and spend your time eating, laughing, and reminiscing with your family in the house you grew up in.

In Japanese, the word “amae” is just as difficult to translate into English. Usually, it’s translated as "spoiled child" or "presumed indulgence," as in making a request and assuming it will be indulged. But both of those have strong negative connotations in English and amae is a positive emotion .

Instead of being spoiled or coddled, it’s referring to that particular kind of trust and assurance that comes with being nurtured by someone and knowing that you can ask for what you want without worrying whether the other person might feel resentful or burdened by your request.

You might have felt amae when your car broke down and you immediately called your mom to pick you up, without having to worry for even a second whether or not she would drop everything to help you.

Regardless of which languages you speak, though, you’re capable of feeling both of these emotions. “The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion,” Dr. Hong explained.

What This Means For You

“While having the words to describe emotions can help us better understand and regulate them, it is possible to experience and express those emotions without specific labels for them.” Without the words for these feelings, you can still feel them but you just might not be able to identify them as readily or clearly as someone who does have those words.

Rhee S. Lexicalization patterns in color naming in Korean . In: Raffaelli I, Katunar D, Kerovec B, eds. Studies in Functional and Structural Linguistics. Vol 78. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2019:109-128. Doi:10.1075/sfsl.78.06rhe

Winawer J, Witthoft N, Frank MC, Wu L, Wade AR, Boroditsky L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7780-7785. 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lindquist KA, MacCormack JK, Shablack H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism . Front Psychol. 2015;6. Doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00444

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

Supplement to Relativism

The linguistic relativity hypothesis.

Many linguists, including Noam Chomsky, contend that language in the sense we ordinary think of it, in the sense that people in Germany speak German, is a historical or social or political notion, rather than a scientific one. For example, German and Dutch are much closer to one another than various dialects of Chinese are. But the rough, commonsense divisions between languages will suffice for our purposes.

There are around 5000 languages in use today, and each is quite different from many of the others. Differences are especially pronounced between languages of different families, e.g., between Indo-European languages like English and Hindi and Ancient Greek, on the one hand, and non-Indo-European languages like Hopi and Chinese and Swahili, on the other.

Many thinkers have urged that large differences in language lead to large differences in experience and thought. They hold that each language embodies a worldview, with quite different languages embodying quite different views, so that speakers of different languages think about the world in quite different ways. This view is sometimes called the Whorf-hypothesis or the Whorf-Sapir hypothesis , after the linguists who made if famous. But the label linguistic relativity , which is more common today, has the advantage that makes it easier to separate the hypothesis from the details of Whorf's views, which are an endless subject of exegetical dispute (Gumperz and Levinson, 1996, contains a sampling of recent literature on the hypothesis).

The suggestion that different languages carve the world up in different ways, and that as a result their speakers think about it differently has a certain appeal. But questions about the extent and kind of impact that language has on thought are empirical questions that can only be settled by empirical investigation. And although linguistic relativism is perhaps the most popular version of descriptive relativism, the conviction and passion of partisans on both sides of the issue far outrun the available evidence. As usual in discussions of relativism, it is important to resist all-or-none thinking. The key question is whether there are interesting and defensible versions of linguistic relativism between those that are trivially true (the Babylonians didn't have a counterpart of the word ‘telephone’, so they didn't think about telephones) and those that are dramatic but almost certainly false (those who speak different languages see the world in completely different ways).

A Preliminary Statement of the Hypothesis

Interesting versions of the linguistic relativity hypothesis embody two claims:

Linguistic Diversity : Languages, especially members of quite different language families, differ in important ways from one another. Linguistic Influence on Thought : The structure and lexicon of one's language influences how one perceives and conceptualizes the world, and they do so in a systematic way.

Together these two claims suggest that speakers of quite different languages think about the world in quite different ways. There is a clear sense in which the thesis of linguistic diversity is uncontroversial. Even if all human languages share many underlying, abstract linguistic universals, there are often large differences in their syntactic structures and in their lexicons. The second claim is more controversial, but since linguistic forces could shape thought in varying degrees, it comes in more and less plausible forms.

1. History of the Hypothesis

Like many other relativistic themes, the hypothesis of linguistic relativity became a serious topic of discussion in late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century Germany, particularly in the work of Johann Georg Hamann (1730-88), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), and Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835). It was later defended by thinkers as diverse as Ernst Cassirer and Peter Winch. Thus Cassirer tells us that

...the distinctions which here are taken for granted, the analysis of reality in terms of things and processes, permanent and transitory aspects, objects and actions, do not precede language as a substratum of given fact, but that language itself is what initiates such articulations, and develops them in its own sphere (1946, p. 12).

But the hypothesis came to prominence though the work of Edward Sapir and his student Benjamin Lee Whorf. Indeed, it is often called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis , or simply the Whorf hypothesis .

There are connections among some of these writers; for example, Sapir wrote his M.A. thesis on Herder's Origin of Language . Still, this is a remarkably diverse group of thinkers who often arrived at their views by different routes, and so it is not surprising that the linguistic relativity hypothesis comes in a variety of forms.

Sapir and Whorf

It will help to see why the linguistic relativity hypothesis captivated so many thinkers if we briefly consider the more arresting claims of Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. Sapir was an American anthropological linguist who, like so many anthropologists of his day, was a student of Franz Boas. He was also the teacher of Whorf, a businessman and amateur linguist.

Unlike earlier partisans of linguistic relativism, Sapir and Whorf based their claims on first-hand experience of the cultures and languages they described, which gave their accounts a good deal of immediacy. I will quote a few of the purpler passages to convey the flavor of their claims, for this was partly what galvanized the imagination of so many readers.

In a paper published in 1929 Sapir tells us:

Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society. It is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection (1929, p. 209).

Our language affects how we perceive things:

Even comparatively simple acts of perception are very much more at the mercy of the social patterns called words than we might suppose. …We see and hear and otherwise experience very largely as we do because the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation (p. 210).

But the differences don't end with perception:

The fact of the matter is that the ‘real world’ is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same worlds with different labels attached (p. 209).

The linguistic relativity hypothesis grained its widest audience through the work of Benjamin Lee Whorf, whose collected writings became something of a relativistic manifesto.

Whorf presents a moving target, with most of his claims coming in both extreme and in more cautious forms. Debate continues about his considered views, but there is little doubt that his bolder claims, unimpeded by caveats or qualifications, were better suited to captivate his readers than more timid claims would have been.

When languages are similar, Whorf tells us, there is little likelihood of dramatic cognitive differences. But languages that differ markedly from English and other Western European languages (which Whorf calls, collectively, “Standard Average European” or SAE) often do lead their speakers to have very different worldviews. Thus

We are thus introduced to a new principle of relativity , which holds that all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way be calibrated. …The relativity of all conceptual systems , ours included, and their dependence upon language stand revealed (1956, p. 214f, italics added). We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds--and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds (p. 213). …no individual is free to describe nature with absolute impartiality but is constrained to certain modes of interpretation even while he thinks himself most free (p. 214).

In fairness it must be stressed that these passages come from a single essay, “Science and Linguistics,” of 1940, and in other places Whorf's tone is often more measured. But not always; elsewhere he also says thing like

…users of markedly different grammars are pointed by their grammars toward different types of observations and different evaluations of externally similar acts of observation, and hence are not equivalent as observers but must arrive at somewhat different views of the world (1956, p. 221).

And in yet a third essay “facts are unlike to speakers whose language background provides for unlike formulation of them” (1956, p. 235).

The passages from Sapir and Whorf bristle with metaphors of coercion: our thought is “at the mercy” of our language, it is “constrained” by it; no one is free to describe the world in a neutral way; we are “compelled” to read certain features into the world (p. 262). The view that language completely determines how we think is often called linguistic determinism . Hamann and Herder sometimes seem to equate language with thought, and in these moods, at least, they came close to endorsing this view.

1.1 Linguistic Relativism and Metaphysics

Some writers have linked these themes directly to issues in metaphysics. For example Graham (1989, Appendix 2) argues that there are vast differences among human languages and that many of the concepts or categories (e.g., physical object, causation, quantity) writers like Aristotle and Kant and Strawson held were central, even indispensable, to human thought, are nothing more than parochial shadows cast by the structure of Indo-European languages. These notions, it is said, have no counterparts in many non-Indo-European languages like Chinese. If this is so, then a fairly strong version of the linguistic relativity hypothesis might be true, but the thesis hasn't been backed with strong empirical evidence and the most common views today lie at the opposite end of the spectrum. Indeed, Whorf himself held a similar view:

[Western] Science …has not yet freed itself from the illusory necessities of common logic which are only at bottom necessities of grammatical pattern in Western Aryan grammar; [e.g.,] necessities for substances which are only necessities for substantives in certain sentence positions …(1956, pp. 269-270).

It is worth noting, finally, that although Whorf was certainly a descriptive relativist he was not a normative relativist . He believed that some languages gave rise to more accurate worldviews than others. Indeed, he thought that the Hopi worldview was superior in various ways to that of speakers of Indo-European languages (e.g., 1956, p. 55, p. 262).

2. The Many Versions of Linguistic Relativism

Any serious discussion of the linguistic relativity hypothesis requires us to answer three questions

- Which aspects of language influence which aspects of thought in some systematic way?

- What form does that influence take?

- How strong is that influence?

For example, certain features of syntax or of the lexicon might exert a causal influence on certain aspects of visual perception (e.g., on which colors we can discriminate), classification (e.g., on how we sort things by their color), or long-term memory (e.g., on which differences among colors we remember most accurately) in clearly specifiable ways. If there is such an influence we would also like to know what mechanisms mediate it, but until we have clearer answers to the first three questions, we are not well positioned to answer this.

Human languages are flexible and extensible, so most things that can be said in one can be approximated in another; if nothing else, words and phrases can be borrowed ( Schadenfreude , je ne sais quoi ). But what is easy to say in one language may be harder to say in a second, and this may make it easier or more natural or more common for speakers of the first language to think in a certain way than for speakers of the second language to do so. A concept or category may be more available in some linguistic communities than in others (e.g., Brown, 1956, pp. 307ff). In short, the linguistic relativity hypothesis comes in stronger and weaker forms, depending on the hypothesized forms and the hypothesized strength of the hypothesized influence.

Various aspects of language might affect cognition.

Grammar Languages can differ in their grammar or syntax. To take a simple example, typical word order may vary. In English, the common order is subject, verb, object. In Japanese it is subject, object, verb. In Welsh, verb, subject, object. Languages can differ in whether they make a distinction between intransitive verbs and adjectives. And there are many subtler sorts of grammatical difference as well. It should be noted that grammar here does not mean the prescriptive grammar we learned in grammar school, but the syntactic structure of a language; in this sense, a grammar comprises a set of rules (or some equivalent device) that can generate all and only the sentences of a given language. Lexicon Different languages have different lexicons (vocabularies), but the important point here is that the lexicons of different languages may classify things in different ways. For example, the color lexicons of some languages segment the color spectrum at different places. Semantics Different languages have different semantic features (over and above differences in lexical semantics) Metaphor Different languages employ different metaphors or employ them in different ways. Pragmatics It is increasingly clear that context plays a vital role in the use and understanding of language, and it is possible that differences in the way speakers of different languages use their languages in concrete settings affects their mental life.

For the most part discussions of the linguistic relativity hypothesis have focused on grammar and lexicon as independent variables. Thus, many of Whorf's claims, e.g., his claims about the way Hopi thought about time, were based on (what he took to be) large-scale differences between Hopi and Standard Average European that included grammatical and lexical differences (e.g., 1956, p. 158). Subsequence research by Ekkehart Malotki (e.g., 1983) and others suggests that Whorf's more dramatic claims were false, but the important point here is that the most prominent versions of the linguistic relativity hypothesis involved large-scale features of language.

Language might influence many different aspects of thought. Most empirical work has focused, appropriately enough, on those aspects that are easiest to assess without relying on language. This is important, since we otherwise risk finding influences of one aspect of language on some related aspect of language , rather than on some aspect of thought. Commonly studied cognitive variables include perceptual discrimination, availability in memory, and classification.

2.1 Testing the Linguistic Relativity Hypotheses

In light of the vast literature on linguistic relativity hypotheses, one would expect that a good deal of careful experimental work had been done on the topic. It hasn't. Often the only evidence cited in favor of such hypotheses is to point to a difference between two languages and assert that it adds up to a difference in modes of thought. But this simply assumes what needs to be shown, namely that such linguistic differences give rise to cognitive differences. On the other hand, refutations of the hypothesis often target implausibly extreme versions of it or proceed as though refutations of it in one domain (e.g., color language and color cognition) show that it is false across the board.

2.2 Many Versions of the Hypothesis have not been Tested

A linguistic relativity hypothesis says that some particular aspect of language influences some particular aspect of cognition . Many different aspects of language could, for all we know, influence many different aspects of cognition. This means that a study showing that some particular aspect of language (e.g., the color lexicon of a language) does (or does not) influence some particular aspect of cognition (e.g., recognition memory of colors) does not tell us whether other aspects of language (e.g., the lexicon for spatial relations) influence other aspects of cognition (e.g., spatial reasoning). It does not even tell us whether the single aspect of language we focused on affects any aspects of thought besides the one we studied, or whether other aspects of language influence the single aspect of thought we examined.

The point here is not merely a theoretical one. When the mind is seen as all of a piece, whether it's the result of stepping through Piaget's universal stages of development, the output of universal learning mechanisms, or the operation of a general-purpose computer, confirming or disconfirming the hypothesis in one area (e.g., color) might bear on its status in other areas. But there is increasing evidence that the mind is, to at least some degree, modular, with different cognitive modules doing domain specific work (e.g., parsing syntax, recognizing faces) and processing different kinds of information in different kinds of ways. If this is right, there is less reason to expect that findings about the influence of language on one aspect of cognition will generalize to other aspects.

Only a handful of versions of the claim that linguistic feature X influences cognitive feature Y in way Z have ever been tested. Some can doubtless be ruled out on the basis of common sense knowledge or previous investigation. But many remain that have yet to be studied. Moreover, those that have been studied often have not been studied with the care they deserve. A few have, though, and we will now turn to them.

Example: Color Language and Color Cognition

Much of the most rigorous investigation of the linguistic relativity hypothesis involves color language and color cognition. In the 1950s and 60s, this was an area where linguistic relativity seemed quite plausible. On the one hand, there is nothing in the physics of light (e.g., in facts about surface spectral reflectances) that suggests drawing boundaries between colors at one place rather than another; in this sense our segmentations of the spectrum are arbitrary. On the one hand, it was well known that different languages had color terms that segmented the color spectrum at different places. So since nothing in the physics of color could determine how humans thought about color, it seemed natural to hypothesis that color cognition followed the grooves laid down by color language.

Color was also an auspicious object of study, because investigators could use Munsell color chips (a widely used, standardized set of chips of different colors) or similar stimulus materials with subjects in quite different locations, thus assuring that whatever differences they found in their dependent variables really did involve the same thing, color (as anchored in the chips), rather than something more nebulous.

Brent Berlin and Paul Kay's work (1969) on basic color terms did much to raise the quality of empirical work on the linguistic relativity hypothesis. And together with much subsequent work it strongly suggests that the strongest, across-the-board versions of the linguistic relativity hypothesis are false when it comes to color language and color cognition. We now know that colors may be a rather special case, however, for although there is nothing in the physics of color that suggests particular segmentations of the spectrum, the opponent-process theory of color vision, now well confirmed, tells us that there are neurophysiological facts about human beings that influence many of the ways in which we perceive colors. We don't know of anything comparable innate mechanisms that would channel thought about social traits or biological classification of diseases in similarly deep grooves. There may well be cross-cultural similarities in the ways human beings think about these things, but we can't conclude this from the work on color.

3. Innateness and Linguistic Universals

The linguist Noam Chomsky has argued for almost half a century that human beings could only learn natural languages if they had a good deal of innate linguistic equipment to guide their way. He has characterized this equipment in different ways over the years, but the abiding theme is that without it children could never get from the sparse set of utterances they hear to the rich linguistic ability they achieve.

3.1 Poverty of the Stimulus Arguments

In just a few years all normal children acquire the language that is spoken by their family and others around them. They acquire a very complex and virtually unbounded ability to distinguish sentences from non-sentences and to understand and utter a virtually unlimited number of sentences they have never thought of before. The child acquires this ability on the basis of the utterances she hears and the feedback (rarely in the form of corrections) she receives. The problem is that the child's data here are very unsystematic and sparse compared to the systematic and nearly unbounded linguistic competence the child quickly acquires.

Hence, the argument continues, the child needs help to get from this impoverished input to the rich output (the acquisition of a grammar of a complex natural language), and this help can only be provided by something innate that constrains and guides the child in her construction of the grammar. The point is quite general: if the input, or data stream, is exiguous then (barring incredible luck) it is only possible for someone to arrive at the right theory about the data if they have some built-in inductive biases, some predispositions to form one kind of theory rather than another. And since any child can learn any human language, the innate endowment must put constraints on which of the countless logically possible languages are humanly possible.

If the features of human languages are limited by such innate, language-acquisition mechanisms, there is less scope for the large differences among languages that the more extreme linguistic relativists have imagined. But might linguistic universals leave room for less extreme versions of linguistic relativism that are still interesting? That depends on what linguistic devices there are and on their relationships to other cognitive mechanisms.

3.2 Modularity

From the perspective of nativist accounts of language, many of the questions about linguistic relativity boil down to questions about the informational encapsulation of mental modules. To say that a module is encapsulated means that other parts of the mind cannot influence its inner workings (though they can supply it with inputs and use its outputs). What are the implications of this for the linguistic relativist's claim that a person's language can exert a dramatic influence on his perception and thought?

The answer may be different for perception, on the one hand, and the higher mental processes, on the other. For example Jerry Fodor (1984) argues that there is a module (or modules) for visual perception and that information from other parts of the mind cannot influence it in the way that many psychologists have supposed. For example, even though I know that the two lines in the Müller-Lyer illusion

Müller-Lyer Illusion

are the same length, I cannot help seeing the line on the left as longer than the line on the right. I know the lengths are the same, but my visual module (or models) does not. It is encapsulated; this information can't get through to it, so it can't influence how I see the figure. If this is so, then linguistic information could not penetrate any vision modules, and so versions of linguistic relativism which hold (as most do) that our language can influence how we see things is wrong.

By contrast, Fodor holds that there is no special module for higher mental processes and, indeed, that we are a long way from having any account of how thinking and reasoning work (e.g., 2000). If this is right, then for all we know now, some aspects of linguistic relativism could be right. The workings of various linguistic modules might influence thought in interesting ways.

It bears stressing that many of the issues involving cognitive architecture are vigorously contested. Among other things, not all champions of modules see them as Fodor does. According to them what is special about visual modules may just be that they process visual information, not that they lack access to other kinds of information (indeed, top-down aspects of perception suggest that they often do have such access). If this is so, there is more room for language to influence perception and other cognitive processes than there is if modules are tightly insulated.

The dust here hasn't begun to settle, but one general moral is clear. If at least moderately strong nativist and modular views of the mind are on the right track--and there is now certainly some reason to think that they are--then many of the empirical issues about linguistic relativity will translate into issues concerning the ways in which various modules can influence one another.

4. Morals for other Independent Variables: Modularity and Encapsulation

We have gone into detail about the linguistic relativity hypothesis, because the main lessons here carry over to the study of the impact of other variables, e.g., culture, on cognition. Some of these emerged above; others are obvious once they are noted. They are

- Questions about the impact of a variable on cognition are empirical and causal questions.

- Such questions can only be answered with care once we specify which aspects of an independent variable, say culture, influence which aspects of thought and what form that influence takes.

- Such hypotheses can vary greatly in specificity, strength, and scope.

- Testing a specific version of the hypothesis requires a combination of skills, including those of a good ethnographer, linguist, and experimental psychologist.

- A comparison of more than two cultures is needed to draw any firm conclusions.

- The truth of specific hypotheses may turn on issues involving the modularity of mind and the degree of modular encapsulation.

- If the mind is highly modular, finding an influence of one aspect of language or culture of some aspect of cognition may tell us little about the influence of other aspects of language or culture on cognition.

These lessons are easier with some variables than with others. It is probably easiest with some aspects of language, because a good deal is now known about many of the languages of the world. It will often be more difficult in the case of culture, where things are more difficult to pin down than they are in the case of language. And it will be virtually impossible when history is the relevant variable; here much more speculative interpretations of historical documents may be the best we can do. But the basic point remains. Relativistic claims are empirical causal claims and they can only be settled by empirical evidence.

It is not always easy to strike the proper balance when thinking about empirical work on these matters. On the one hand it is useful to cultivate an “it-can't-be-that-simple” reflex for use when reading an isolated study or two. But on the other hand empirical investigation is the only thing that can answer many of the difficult questions about the complex, entangled processes of language, culture, and thought.

Return to Relativism: §1: A Framework for Relativism Return to Relativism: §2: Dependent Variables: What is Relative? Return to Relativism: §3: Independent Variables: Relative to What? Return to Relativism: §4: Arguments For Relativism Return to Relativism: §5: Arguments Against Relativism Return to Relativism: Table of Contents

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Linguistic Theory

DrAfter123/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the linguistic theory that the semantic structure of a language shapes or limits the ways in which a speaker forms conceptions of the world. It came about in 1929. The theory is named after the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and his student Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941). It is also known as the theory of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativism, linguistic determinism, Whorfian hypothesis , and Whorfianism .

History of the Theory

The idea that a person's native language determines how he or she thinks was popular among behaviorists of the 1930s and on until cognitive psychology theories came about, beginning in the 1950s and increasing in influence in the 1960s. (Behaviorism taught that behavior is a result of external conditioning and doesn't take feelings, emotions, and thoughts into account as affecting behavior. Cognitive psychology studies mental processes such as creative thinking, problem-solving, and attention.)

Author Lera Boroditsky gave some background on ideas about the connections between languages and thought:

"The question of whether languages shape the way we think goes back centuries; Charlemagne proclaimed that 'to have a second language is to have a second soul.' But the idea went out of favor with scientists when Noam Chomsky 's theories of language gained popularity in the 1960s and '70s. Dr. Chomsky proposed that there is a universal grammar for all human languages—essentially, that languages don't really differ from one another in significant ways...." ("Lost in Translation." "The Wall Street Journal," July 30, 2010)

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was taught in courses through the early 1970s and had become widely accepted as truth, but then it fell out of favor. By the 1990s, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was left for dead, author Steven Pinker wrote. "The cognitive revolution in psychology, which made the study of pure thought possible, and a number of studies showing meager effects of language on concepts, appeared to kill the concept in the 1990s... But recently it has been resurrected, and 'neo-Whorfianism' is now an active research topic in psycholinguistics ." ("The Stuff of Thought. "Viking, 2007)

Neo-Whorfianism is essentially a weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and says that language influences a speaker's view of the world but does not inescapably determine it.

The Theory's Flaws

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis stems from the idea that if a person's language has no word for a particular concept, then that person would not be able to understand that concept, which is untrue. Language doesn't necessarily control humans' ability to reason or have an emotional response to something or some idea. For example, take the German word sturmfrei , which essentially is the feeling when you have the whole house to yourself because your parents or roommates are away. Just because English doesn't have a single word for the idea doesn't mean that Americans can't understand the concept.

There's also the "chicken and egg" problem with the theory. "Languages, of course, are human creations, tools we invent and hone to suit our needs," Boroditsky continued. "Simply showing that speakers of different languages think differently doesn't tell us whether it's language that shapes thought or the other way around."

- Definition and Discussion of Chomskyan Linguistics

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Cognitive Grammar

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- Linguistic Performance

- What Is a Natural Language?

- Linguistic Competence: Definition and Examples

- Transformational Grammar (TG) Definition and Examples

- What Is Linguistic Functionalism?

- 24 Words Worth Borrowing From Other Languages

- The Theory of Poverty of the Stimulus in Language Development

- Definition and Examples of Case Grammar

- The Definition and Usage of Optimality Theory

- An Introduction to Semantics

- Construction Grammar

- 10 Types of Grammar (and Counting)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: Linguistic Relativity- The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 75159

- Manon Allard-Kropp

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

1. Define the concept of linguistic relativity

2. Differentiate linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism

3. Define the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (against more pop-culture takes on it) and situate it in a broader theoretical context/history

4. Provide examples of linguistic relativity through examples related to time, space, metaphors, etc.

In this part, we will look at language(s) and worldviews at the intersection of language & thoughts and language & cognition (i.e., the mental system with which we process the world around us, and with which we learn to function and make sense of it). Our main question, which we will not entirely answer but which we will examine in depth, is a chicken and egg one: does thought determine language, or does language inform thought?

We will talk about the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis; look at examples that support the notion of linguistic relativity (pronouns, kinship terms, grammatical tenses, and what they tell us about culture and worldview); and then we will more specifically look into how metaphors are a structural component of worldview, if not cognition itself; and we will wrap up with memes. (Can we analyze memes through an ethnolinguistic, relativist lens? We will try!)

3.1 Linguistic Relativity: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Sapir, considered the father of American linguistic anthropology, was responsible for documenting and recording the languages and cultures of many Native American tribes, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. This was due primarily to the deliberate efforts of the United States government to force Native Americans to assimilate into the Euro-American culture. Sapir and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between culture and language because each culture is reflected in and influences its language. Anthropologists need to learn the language of the culture they are studying in order to understand the world view of its speakers. Whorf believed that the reverse is also true, that a language affects culture as well, by actually influencing how its speakers think. His hypothesis proposes that the words and the structures of a language influence how its speakers think about the world, how they behave, and ultimately the culture itself. (See our definition of culture in Part 1 of this document.) Simply stated, Whorf believed that human beings see the world the way they do because the specific languages they speak influence them to do so.

He developed this idea through both his work with Sapir and his work as a chemical engineer for the Hartford Insurance Company investigating the causes of fires. One of his cases while working for the insurance company was a fire at a business where there were a number of gasoline drums. Those that contained gasoline were surrounded by signs warning employees to be cautious around them and to avoid smoking near them. The workers were always careful around those drums. On the other hand, empty gasoline drums were stored in another area, but employees were more careless there. Someone tossed a cigarette or lighted match into one of the “empty” drums, it went up in flames, and started a fire that burned the business to the ground. Whorf theorized that the meaning of the word empty implied to the worker that “nothing” was there to be cautious about so the worker behaved accordingly. Unfortunately, an “empty” gasoline drum may still contain fumes, which are more flammable than the liquid itself.

Whorf ’s studies at Yale involved working with Native American languages, including Hopi. The Hopi language is quite different from English, in many ways. For example, let’s look at how the Hopi language deals with time. Western languages (and cultures) view time as a flowing river in which we are being carried continuously away from a past, through the present, and into a future. Our verb systems reflect that concept with specific tenses for past, present, and future. We think of this concept of time as universal, that all humans see it the same way. A Hopi speaker has very different ideas and the structure of their language both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. The Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English speaking world when it came to being “on time” for work or other events. It is simply not how they had been conditioned to behave with respect to time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

In a book about the Abenaki who lived in Vermont in the mid-1800s, Trudy Ann Parker described their concept of time, which very much resembled that of the Hopi and many of the other Native American tribes. “They called one full day a sleep, and a year was called a winter. Each month was referred to as a moon and always began with a new moon. An Indian day wasn’t divided into minutes or hours. It had four time periods—sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. Each season was determined by the budding or leafing of plants, the spawning of fish, or the rutting time for animals. Most Indians thought the white race had been running around like scared rabbits ever since the invention of the clock.”

The lexicon , or vocabulary, of a language is an inventory of the items a culture talks about and has categorized in order to make sense of the world and deal with it effectively. For example, modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some kind of vehicle—cars, trucks, SUVs, trains, buses, etc. We therefore have thousands of words to talk about them, including types of vehicles, models, brands, or parts.

The most important aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the lexicon of its language. Among the societies living in the islands of Oceania in the Pacific, fish have great economic and cultural importance. This is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival. For example, in Palau there are about 1,000 fish species and Palauan fishermen knew, long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them—in many cases far more than modern biologists know even today. Much of fish behavior is related to the tides and the phases of the moon. Throughout Oceania, the names given to certain days of the lunar months reflect the likelihood of successful fishing. For example, in the Caroline Islands, the name for the night before the new moon is otolol , which means “to swarm.” The name indicates that the best fishing days cluster around the new moon. In Hawai`i and Tahiti two sets of days have names containing the particle `ole or `ore ; one occurs in the first quarter of the moon and the other in the third quarter. The same name is given to the prevailing wind during those phases. The words mean “nothing,” because those days were considered bad for fishing as well as planting.

Parts of Whorf ’s hypothesis, known as linguistic relativity , were controversial from the beginning, and still are among some linguists. Yet Whorf ’s ideas now form the basis for an entire sub-field of cultural anthropology: cognitive or psychological anthropology. A number of studies have been done that support Whorf ’s ideas. Linguist George Lakoff ’s work looks at the pervasive existence of metaphors in everyday speech that can be said to predispose a speaker’s world view and attitudes on a variety of human experiences. A metaphor is an expression in which one kind of thing is understood and experienced in terms of another entirely unrelated thing; the metaphors in a language can reveal aspects of the culture of its speakers. Take, for example, the concept of an argument. In logic and philosophy, an argument is a discussion involving differing points of view, or a debate. But the conceptual metaphor in American culture can be stated as ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in many expressions of the everyday language of American speakers: I won the argument. He shot down every point I made. They attacked every argument we made. Your point is right on target . I had a fight with my boyfriend last night. In other words, we use words appropriate for discussing war when we talk about arguments, which are certainly not real war. But we actually think of arguments as a verbal battle that often involve anger, and even violence, which then structures how we argue.

To illustrate that this concept of argument is not universal, Lakoff suggests imagining a culture where an argument is not something to be won or lost, with no strategies for attacking or defending, but rather as a dance where the dancers’ goal is to perform in an artful, pleasing way. No anger or violence would occur or even be relevant to speakers of this language, because the metaphor for that culture would be ARGUMENT IS DANCE.

3.1 Adapted from Perspectives , Language ( Linda Light, 2017 )

You can either watch the video, How Language Shapes the Way We Think, by linguist Lera Boroditsky, or read the script below.

Watch the video: How Language Shapes the Way We Think ( Boroditsky, 2018)

There are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world—and they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. But do they shape the way we think? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shares examples of language—from an Aboriginal community in Australia that uses cardinal directions instead of left and right to the multiple words for blue in Russian—that suggest the answer is a resounding yes. “The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is,” Boroditsky says. “Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000.”

Video transcript:

So, I’ll be speaking to you using language ... because I can. This is one these magical abilities that we humans have. We can transmit really complicated thoughts to one another. So what I’m doing right now is, I’m making sounds with my mouth as I’m exhaling. I’m making tones and hisses and puffs, and those are creating air vibrations in the air. Those air vibrations are traveling to you, they’re hitting your eardrums, and then your brain takes those vibrations from your eardrums and transforms them into thoughts. I hope.

I hope that’s happening. So because of this ability, we humans are able to transmit our ideas across vast reaches of space and time. We’re able to transmit knowledge across minds. I can put a bizarre new idea in your mind right now. I could say, “Imagine a jellyfish waltzing in a library while thinking about quantum mechanics.”

Now, if everything has gone relatively well in your life so far, you probably haven’t had that thought before.

But now I’ve just made you think it, through language.

Now of course, there isn’t just one language in the world, there are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And all the languages differ from one another in all kinds of ways. Some languages have different sounds, they have different vocabularies, and they also have different structures—very importantly, different structures. That begs the question: Does the language we speak shape the way we think? Now, this is an ancient question. People have been speculating about this question forever. Charlemagne, Holy Roman emperor, said, “To have a second language is to have a second soul”—strong statement that language crafts reality. But on the other hand, Shakespeare has Juliet say, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Well, that suggests that maybe language doesn’t craft reality.

These arguments have gone back and forth for thousands of years. But until recently, there hasn’t been any data to help us decide either way. Recently, in my lab and other labs around the world, we’ve started doing research, and now we have actual scientific data to weigh in on this question.

So let me tell you about some of my favorite examples. I’ll start with an example from an Aboriginal community in Australia that I had a chance to work with. These are the Kuuk Thaayorre people. They live in Pormpuraaw at the very west edge of Cape York. What’s cool about Kuuk Thaayorre is, in Kuuk Thaayorre, they don’t use words like “left” and “right,” and instead, everything is in cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. And when I say everything, I really mean everything. You would say something like, “Oh, there’s an ant on your southwest leg.” Or, “Move your cup to the north-northeast a little bit.” In fact, the way that you say “hello” in Kuuk Thaayorre is you say, “Which way are you going?” And the answer should be, “North-northeast in the far distance. How about you?”

So imagine as you’re walking around your day, every person you greet, you have to report your heading direction.

But that would actually get you oriented pretty fast, right? Because you literally couldn’t get past “hello,” if you didn’t know which way you were going. In fact, people who speak languages like this stay oriented really well. They stay oriented better than we used to think humans could. We used to think that humans were worse than other creatures because of some biological excuse: “Oh, we don’t have magnets in our beaks or in our scales.” No; if your language and your culture trains you to do it, actually, you can do it. There are humans around the world who stay oriented really well.

And just to get us in agreement about how different this is from the way we do it, I want you all to close your eyes for a second and point southeast.

Keep your eyes closed. Point. OK, so you can open your eyes. I see you guys pointing there, there, there, there, there ... I don’t know which way it is myself—

You have not been a lot of help.

So let’s just say the accuracy in this room was not very high. This is a big difference in cognitive ability across languages, right? Where one group—very distinguished group like you guys—doesn’t know which way is which, but in another group, I could ask a five-year-old and they would know.

There are also really big differences in how people think about time. So here I have pictures of my grandfather at different ages. And if I ask an English speaker to organize time, they might lay it out this way, from left to right. This has to do with writing direction. If you were a speaker of Hebrew or Arabic, you might do it going in the opposite direction, from right to left.

But how would the Kuuk Thaayorre, this Aboriginal group I just told you about, do it? They don’t use words like “left” and “right.” Let me give you hint. When we sat people facing south, they organized time from left to right. When we sat them facing north, they organized time from right to left. When we sat them facing east, time came towards the body. What’s the pattern? East to west, right? So for them, time doesn’t actually get locked on the body at all, it gets locked on the landscape. So for me, if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way, and if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way. I’m facing this way, time goes this way— very egocentric of me to have the direction of time chase me around every time I turn my body. For the Kuuk Thaayorre, time is locked on the landscape. It’s a dramatically different way of thinking about time.

Here’s another really smart human trait. Suppose I ask you how many penguins are there. Well, I bet I know how you’d solve that problem if you solved it. You went, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight.” You counted them. You named each one with a number, and the last number you said was the number of penguins. This is a little trick that you’re taught to use as kids. You learn the number list and you learn how to apply it. A little linguistic trick. Well, some languages don’t do this, because some languages don’t have exact number words. They’re languages that don’t have a word like “seven” or a word like “eight.” In fact, people who speak these languages don’t count, and they have trouble keeping track of exact quantities. So, for example, if I ask you to match this number of penguins to the same number of ducks, you would be able to do that by counting. But folks who don’t have that linguistic trait can’t do that.