Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 22 February 2024

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- Stephen V. Faraone ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9217-3982 1 ,

- Mark A. Bellgrove ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0186-8349 2 ,

- Isabell Brikell 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Samuele Cortese 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ,

- Catharina A. Hartman 11 ,

- Chris Hollis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1083-6744 12 ,

- Jeffrey H. Newcorn 13 ,

- Alexandra Philipsen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6876-518X 14 ,

- Guilherme V. Polanczyk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2311-3289 15 ,

- Katya Rubia 16 , 17 ,

- Margaret H. Sibley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7167-2240 18 &

- Jan K. Buitelaar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8288-7757 19 , 20

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 10 , Article number: 11 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

5928 Accesses

6 Citations

186 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Medical genetics

An Author Correction to this article was published on 15 April 2024

This article has been updated

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; also known as hyperkinetic disorder) is a common neurodevelopmental condition that affects children and adults worldwide. ADHD has a predominantly genetic aetiology that involves common and rare genetic variants. Some environmental correlates of the disorder have been discovered but causation has been difficult to establish. The heterogeneity of the condition is evident in the diverse presentation of symptoms and levels of impairment, the numerous co-occurring mental and physical conditions, the various domains of neurocognitive impairment, and extensive minor structural and functional brain differences. The diagnosis of ADHD is reliable and valid when evaluated with standard diagnostic criteria. Curative treatments for ADHD do not exist but evidence-based treatments substantially reduce symptoms and/or functional impairment. Medications are effective for core symptoms and are usually well tolerated. Some non-pharmacological treatments are valuable, especially for improving adaptive functioning. Clinical and neurobiological research is ongoing and could lead to the creation of personalized diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for this disorder.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Polygenic profiles define aspects of clinical heterogeneity in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Machine learning in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: new approaches toward understanding the neural mechanisms

Differences in the genetic architecture of common and rare variants in childhood, persistent and late-diagnosed attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Change history, 15 april 2024.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00518-w

Faraone, S. V. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1 , 15020 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

World Health Organization. International classification of diseases 11th revision (WHO, 2022).

Faraone, S. V. et al. The World Federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 128 , 789–818 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Polanczyk, G., de Lima, M. S., Horta, B. L., Biederman, J. & Rohde, L. A. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 , 942–948 (2007).

Polanczyk, G. V., Willcutt, E. G., Salum, G. A., Kieling, C. & Rohde, L. A. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43 , 434–442 (2014).

Wootton, R. E. et al. Decline in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder traits over the life course in the general population: trajectories across five population birth cohorts spanning ages 3 to 45 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51 , 919–930 (2022).

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J. & Mick, E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol. Med. 36 , 159–165 (2006).

Simon, V., Czobor, P., Balint, S., Meszaros, A. & Bitter, I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 194 , 204–211 (2009).

Song, P. et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 11 , 04009 (2021).

Vos, M. & Hartman, C. A. The decreasing prevalence of ADHD across the adult lifespan confirmed. J. Glob. Health 12 , 03024 (2022).

Solmi, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 27 , 281–295 (2021).

Grevet, E. H. et al. The course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through midlife. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 274 , 59–70 (2022).

Sibley, M. H. et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am. J. Psychiatry 179 , 142–151 (2022).

Vos, M. et al. Characterizing the heterogeneous course of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity from childhood to young adulthood. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 31 , 1–11 (2022).

Pedersen, S. L. et al. Real-world changes in adolescents’ ADHD symptoms within the day and across school and non-school days. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 48 , 1543–1553 (2020).

Van Meter, A. R. et al. The stability and persistence of symptoms in childhood-onset ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02235-3 (2023).

Halperin, J. M. & Marks, D. J. Practitioner review: assessment and treatment of preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 60 , 930–943 (2019).

MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56 , 1073–1086 (1999).

Article Google Scholar

Staller, J. & Faraone, S. V. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs 20 , 107–123 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bruchmuller, K., Margraf, J. & Schneider, S. Is ADHD diagnosed in accord with diagnostic criteria? Overdiagnosis and influence of client gender on diagnosis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 80 , 128–138 (2012).

Dalsgaard, S. et al. Incidence rates and cumulative incidences of the full spectrum of diagnosed mental disorders in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 77 , 155–164 (2020).

Solberg, B. S. et al. Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity: a population-based study of 40 000 adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 137 , 176–186 (2018).

Libutzki, B. et al. Direct medical costs of ADHD and its comorbid conditions on basis of a claims data analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 58 , 38–44 (2019).

Chen, Q. et al. Common psychiatric and metabolic comorbidity of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 13 , e0204516 (2018).

Sundquist, J., Ohlsson, H., Sundquist, K. & Kendler, K. S. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry 17 , 235 (2017).

Cortese, S., Faraone, S. V., Bernardi, S., Wang, S. & Blanco, C. Gender differences in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J. Clin. Psychiatry 77 , e421–e428 (2016).

Gaub, M. & Carlson, C. L. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 36 , 1036–1045 (1997).

Hinshaw, S. P., Nguyen, P. T., O’Grady, S. M. & Rosenthal, E. A. Annual research review: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women: underrepresentation, longitudinal processes, and key directions. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 63 , 484–496 (2022).

Young, S. et al. Females with ADHD: an expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 20 , 404 (2020).

Harris, M. G. et al. Gender-related patterns and determinants of recent help-seeking for past-year affective, anxiety and substance use disorders: findings from a national epidemiological survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 25 , 548–561 (2016).

Khoury, N. M., Radonjić, N. V., Albert, A. B. & Faraone, S. V. From structural disparities to neuropharmacology: a review of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication treatment. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 31 , 343–361 (2022).

Slobodin, O. & Masalha, R. Challenges in ADHD care for ethnic minority children: a review of the current literature. Transcult. Psychiatry 57 , 468–483 (2020).

Coker, T. R. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment. Pediatrics 138 , e20160407 (2016).

Miller, T. W., Nigg, J. T. & Miller, R. L. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in African American children: what can be concluded from the past ten years? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29 , 77–86 (2009).

Morgan, P. L., Staff, J., Hillemeier, M. M., Farkas, G. & Maczuga, S. Racial and ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis from kindergarten to eighth grade. Pediatrics 132 , 85–93 (2013).

Morgan, P. L., Hillemeier, M. M., Farkas, G. & Maczuga, S. Racial/ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis by kindergarten entry. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 55 , 905–913 (2014).

Stevens, J., Harman, J. S. & Kelleher, K. J. Race/ethnicity and insurance status as factors associated with ADHD treatment patterns. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 15 , 88–96 (2005).

Shi, Y. et al. Racial disparities in diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a US national birth cohort. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 , e210321 (2021).

Glasofer, A., Dingley, C. & Reyes, A. T. Medication decision making among African American caregivers of children with ADHD: a review of the literature. J. Atten. Disord. 25 , 1687–1698 (2021).

Fairman, K. A., Peckham, A. M. & Sclar, D. A. Diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in the United States: update by gender and race. J. Atten. Disord. 24 , 10–19 (2020).

Biederman, J., Newcorn, J. & Sprich, S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 148 , 564–577 (1991).

Hartman, C. A. et al. Anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders in adult men and women with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a substantive and methodological overview. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 151 , 105209 (2023).

Dalsgaard, S., Ostergaard, S. D., Leckman, J. F., Mortensen, P. B. & Pedersen, M. G. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet 385 , 2190–2196 (2015).

Elwin, M., Elvin, T. & Larsson, J. O. Symptoms and level of functioning related to comorbidity in children and adolescents with ADHD: a cross-sectional registry study. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 14 , 30 (2020).

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R. & Walters, E. E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 , 617–627 (2005).

Sun, S. et al. Association of psychiatric comorbidity with the risk of premature death among children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 1141–1149 (2019).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The effects of temporally secondary co-morbid mental disorders on the associations of DSM-IV ADHD with adverse outcomes in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychol. Med. 44 , 1779–1792 (2014).

Angold, A., Costello, J. & Erkanli, A. Comorbidity. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat 40 , 57–87 (1999).

Biederman, J. et al. The longitudinal course of comorbid oppositional defiant disorder in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: findings from a controlled 5-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 29 , 501–507 (2008).

Biederman, J. et al. The long-term longitudinal course of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in ADHD boys: findings from a controlled 10-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. Psychol. Med. 38 , 1027–1036 (2008).

Instanes, J. T., Klungsoyr, K., Halmoy, A., Fasmer, O. B. & Haavik, J. Adult ADHD and comorbid somatic disease: a systematic literature review. J. Atten. Disord. 22 , 203–228 (2016).

Kittel-Schneider, S. et al. Non-mental diseases associated with ADHD across the lifespan: Fidgety Philipp and Pippi Longstocking at risk of multimorbidity? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 132 , 1157–1180 (2021).

Arrondo, G. et al. Associations between mental and physical conditions in children and adolescents: an umbrella review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 137 , 104662 (2022).

Garcia-Argibay, M. et al. The association between type 2 diabetes and attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and population-based sibling study. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 147 , 105076 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases: a nationwide population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry 21 , 452–459 (2022).

Bellato, A. et al. Association between ADHD and vision problems. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 410–422 (2023).

Cortese, S., Faraone, S. V., Konofal, E. & Lecendreux, M. Sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of subjective and objective studies. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 48 , 894–908 (2009).

PubMed Google Scholar

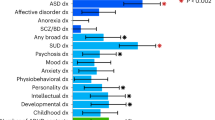

Gidziela, A. et al. A meta-analysis of genetic effects associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and co-occurring conditions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7 , 642–656 (2023).

Polderman, T. J. et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 47 , 702–709 (2015).

Faraone, S. V. & Larsson, H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 24 , 562–575 (2018).

Brikell, I., Kuja-Halkola, R. & Larsson, H. Heritability of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 168 , 406–413 (2015).

Nikolas, M. A. & Burt, S. A. Genetic and environmental influences on ADHD symptom dimensions of inattention and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119 , 1–17 (2010).

Taylor, M. J. et al. Association of genetic risk factors for psychiatric disorders and traits of these disorders in a Swedish population twin sample. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 280–289 (2019).

Brikell, I., Burton, C., Mota, N. R. & Martin, J. Insights into attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from recent genetic studies. Psychol. Med. 51 , 2274–2286 (2021).

Tistarelli, N., Fagnani, C., Troianiello, M., Stazi, M. A. & Adriani, W. The nature and nurture of ADHD and its comorbidities: a narrative review on twin studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 109 , 63–77 (2020).

Martin, J., Taylor, M. J. & Lichtenstein, P. Assessing the evidence for shared genetic risks across psychiatric disorders and traits. Psychol. Med. 48 , 1759–1774 (2018).

Andersson, A. et al. Research review: the strength of the genetic overlap between ADHD and other psychiatric symptoms – a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 61 , 1173–1183 (2020).

Daucourt, M. C., Erbeli, F., Little, C. W., Haughbrook, R. & Hart, S. A. A meta-analytical review of the genetic and environmental correlations between reading and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and reading and math. Sci. Stud. Read. 24 , 23–56 (2020).

Du Rietz, E. et al. Mapping phenotypic and aetiological associations between ADHD and physical conditions in adulthood in Sweden: a genetically informed register study. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 774–783 (2021).

Demontis, D. et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat. Genet. 55 , 198–208 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Martin, J. et al. A genetic investigation of sex bias in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 83 , 1044–1053 (2018).

Rajagopal, V. M. et al. Differences in the genetic architecture of common and rare variants in childhood, persistent and late-diagnosed attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 54 , 1117–1124 (2022).

Rovira, P. et al. Shared genetic background between children and adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 45 , 1617–1626 (2020).

Ronald, A., de Bode, N. & Polderman, T. J. C. Systematic review: how the attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder polygenic risk score adds to our understanding of ADHD and associated traits. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 60 , 1234–1277 (2021).

Leppert, B. et al. A cross-disorder PRS-pheWAS of 5 major psychiatric disorders in UK Biobank. PLoS Genet. 16 , e1008185 (2020).

Brikell, I. et al. Interplay of ADHD polygenic liability with birth-related, somatic, and psychosocial factors in ADHD: a nationwide study. Am. J. Psychiatry 180 , 73–88 (2023).

Barnett, E. J. et al. Identifying pediatric mood disorders from transdiagnostic polygenic risk scores: a study of children and adolescents. J. Clin. Psychiatry 83 , 21m14180 (2022).

Hamshere, M. L. et al. High loading of polygenic risk for ADHD in children with comorbid aggression. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 , 909–916 (2013).

Green, A., Baroud, E., DiSalvo, M., Faraone, S. V. & Biederman, J. Examining the impact of ADHD polygenic risk scores on ADHD and associated outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 155 , 49–67 (2022).

Moses, M. et al. Working memory and reaction time variability mediate the relationship between polygenic risk and ADHD traits in a general population sample. Mol. Psychiatry 27 , 5028–5037 (2022).

Vainieri, I. et al. Polygenic association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder liability and cognitive impairments. Psychol. Med. 52 , 3150–3158 (2022).

Klein, M. et al. Genetic markers of ADHD-related variations in intracranial volume. Am. J. Psychiatry 176 , 228–238 (2019).

Hermosillo, R. J. M. et al. Polygenic risk score-derived subcortical connectivity mediates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 5 , 330–341 (2019).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Satterstrom, F. K. et al. Autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have a similar burden of rare protein-truncating variants. Nat. Neurosci. 22 , 1961–1965 (2019).

Harich, B. et al. From rare copy number variants to biological processes in ADHD. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 855–866 (2020).

Gudmundsson, O. O. et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder shares copy number variant risk with schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 9 , 258 (2019).

Calle Sánchez, X. et al. Comparing copy number variations in a Danish case cohort of individuals with psychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 59–69 (2022).

Boland, H. et al. A literature review and meta-analysis on the effects of ADHD medications on functional outcomes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 123 , 21–30 (2020).

Bonvicini, C., Faraone, S. V. & Scassellati, C. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of genetic, pharmacogenetic and biochemical studies. Mol. Psychiatry 21 , 1643 (2016).

Adeyemo, B. O. et al. Mild traumatic brain injury and ADHD: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. J. Atten. Disord. 18 , 576–584 (2014).

Asarnow, R. F., Newman, N., Weiss, R. E. & Su, E. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnoses with pediatric traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 175 , 1009–1016 (2021).

Stevens, S. E. et al. Inattention/overactivity following early severe institutional deprivation: presentation and associations in early adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 36 , 385–398 (2008).

Kim, J. H. et al. Environmental risk factors, protective factors, and peripheral biomarkers for ADHD: an umbrella review. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 955–970 (2020).

Taubes, G. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science 269 , 164–169 (1995).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167 , 268–274 (2017).

Spencer, N. J. et al. Social gradients in ADHD by household income and maternal education exposure during early childhood: findings from birth cohort studies across six countries. PLoS ONE 17 , e0264709 (2022).

Schmengler, H. et al. Educational level, attention problems, and externalizing behaviour in adolescence and early adulthood: the role of social causation and health-related selection-the TRAILS study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 32 , 809–824 (2021).

Burt, S. A. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: a meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychol. Bull. 135 , 608–637 (2009).

Marees, A. T. et al. Genetic correlates of socio-economic status influence the pattern of shared heritability across mental health traits. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 1065–1073 (2021).

Kong, A. et al. The nature of nurture: effects of parental genotypes. Science 359 , 424–428 (2018).

Howe, L. J. et al. Within-sibship genome-wide association analyses decrease bias in estimates of direct genetic effects. Nat. Genet. 54 , 581–592 (2022).

Zwicker, A. et al. Neurodevelopmental and genetic determinants of exposure to adversity among youth at risk for mental illness. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61 , 536–544 (2019).

de la Paz, L. et al. Youth polygenic scores, youth ADHD symptoms, and parenting dimensions: an evocative gene-environment correlation study. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 51 , 665–677 (2023).

Havdahl, A. et al. Associations between pregnancy-related predisposing factors for offspring neurodevelopmental conditions and parental genetic liability to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, and schizophrenia: the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 799–810 (2022).

Leppert, B. et al. Association of maternal neurodevelopmental risk alleles with early-life exposures. JAMA Psychiatry 76 , 834–842 (2019).

Thapar, A. & Rutter, M. Do prenatal risk factors cause psychiatric disorder? Be wary of causal claims. Br. J. Psychiatry 195 , 100–101 (2009).

Carlsson, T., Molander, F., Taylor, M. J., Jonsson, U. & Bölte, S. Early environmental risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders – a systematic review of twin and sibling studies. Dev. Psychopathol. 195 , 1448–1495 (2020).

Google Scholar

He, Y., Chen, J., Zhu, L. H., Hua, L. L. & Ke, F. F. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Atten. Disord. 24 , 1637–1647 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Maternal smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 141 , e20172465 (2017).

Dong, T. et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal smoking during pregnancy and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: a meta-analysis. Reprod. Toxicol. 76 , 63–70 (2018).

Ratanatharathorn, A., Chibnik, L. B., Koenen, K. C., Weisskopf, M. G. & Roberts, A. L. Association of maternal polygenic risk scores for mental illness with perinatal risk factors for offspring mental illness. Sci. Adv. 8 , eabn3740 (2022).

Thapar, A. et al. Prenatal smoking might not cause attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a novel design. Biol. Psychiatry 66 , 722–727 (2009).

Faraone, S. V. & Biederman, J. Can attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder onset occur in adulthood? JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 655–656 (2016).

Dvorsky, M. R. & Langberg, J. M. A review of factors that promote resilience in youth with ADHD and ADHD symptoms. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 19 , 368–391 (2016).

Barry, R. J., Johnstone, S. J. & Clarke, A. R. A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. Event-related potentials. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114 , 184–198 (2003).

Barry, R. J., Clarke, A. R. & Johnstone, S. J. A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Qualitative and quantitative electroencephalography. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114 , 171–183 (2003).

Kaiser, A. et al. Earlier versus later cognitive event-related potentials (ERPs) in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 112 , 117–134 (2020).

Hoogman, M. et al. Brain imaging of the cortex in ADHD: a coordinated analysis of large-scale clinical and population-based samples. Am. J. Psychiatry 176 , 531–542 (2019).

Hoogman, M. et al. Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 4 , 310–319 (2017).

Albaugh, M. D. et al. White matter microstructure is associated with hyperactive/inattentive symptomatology and polygenic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population-based sample of adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology 44 , 1597–1603 (2019).

Clarke, A. R., Barry, R. J. & Johnstone, S. Resting state EEG power research in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review update. Clin. Neurophysiol. 131 , 1463–1479 (2020).

Bussalb, A. et al. Is there a cluster of high theta-beta ratio patients in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? Clin. Neurophysiol. 130 , 1387–1396 (2019).

Slater, J. et al. Can electroencephalography (EEG) identify ADHD subtypes? A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 139 , 104752 (2022).

Parlatini, V. et al. Network abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a systematic review of 127 diffusion imaging studies with meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 4098–4123 (2023).

Sudre, G. et al. Mapping the cortico-striatal transcriptome in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 792–800 (2023).

Hart, H., Radua, J., Nakao, T., Mataix-Cols, D. & Rubia, K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 185–198 (2013).

Norman, L. J. et al. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparative meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 815–825 (2016).

Lukito, S. et al. Comparative meta-analyses of brain structural and functional abnormalities during cognitive control in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Med. 50 , 894–919 (2020).

Samea, F. et al. Brain alterations in children/adolescents with ADHD revisited: a neuroimaging meta-analysis of 96 structural and functional studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 100 , 1–8 (2019).

McCarthy, H., Skokauskas, N. & Frodl, T. Identifying a consistent pattern of neural function in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 44 , 869–880 (2014).

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. & Castellanos, F. X. Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: a neurobiological hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31 , 977–986 (2007).

Gao, Y. et al. Impairments of large-scale functional networks in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Psychol. Med. 49 , 2475–2485 (2019).

Sutcubasi, B. et al. Resting-state network dysconnectivity in ADHD: a system-neuroscience-based meta-analysis. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 21 , 662–672 (2020).

Norman, L. J., Sudre, G., Price, J., Shastri, G. G. & Shaw, P. Evidence from “big data” for the default-mode hypothesis of ADHD: a mega-analysis of multiple large samples. Neuropsychopharmacology 48 , 281–289 (2023).

Cortese, S., Aoki, Y. Y., Itahashi, T., Castellanos, F. X. & Eickhoff, S. B. Systematic review and meta-analysis: resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 60 , 61–75 (2021).

Shaw, P. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 19649–19654 (2007).

Shaw, P. et al. Development of cortical surface area and gyrification in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 72 , 191–197 (2012).

Shaw, P. et al. A multicohort, longitudinal study of cerebellar development in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 59 , 1114–1123 (2018).

Sripada, C. S., Kessler, D. & Angstadt, M. Lag in maturation of the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 14259–14264 (2014).

Norman, L. J., Sudre, G., Bouyssi-Kobar, M., Sharp, W. & Shaw, P. An examination of the relationships between attention/deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and functional connectivity over time. Neuropsychopharmacology 47 , 704–710 (2022).

Faraone, S. V. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 87 , 255–270 (2018).

Radonjić, N. V., Bellato, A., Khoury, N. M., Cortese, S. & Faraone, S. V. Nonstimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 37 , 381–397 (2023).

Pretus, C. et al. Time and psychostimulants: opposing long-term structural effects in the adult ADHD brain. A longitudinal MR study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 27 , 1238–1247 (2017).

Walhovd, K. B. et al. Methylphenidate effects on cortical thickness in children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized clinical trial. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41 , 758–765 (2020).

Bouziane, C. et al. White matter by diffusion MRI following methylphenidate treatment: a randomized control trial in males with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Radiology 293 , 186–192 (2019).

Greven, C. U. et al. Developmentally stable whole-brain volume reductions and developmentally sensitive caudate and putamen volume alterations in those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 490–499 (2015).

Schweren, L. J. et al. Thinner medial temporal cortex in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effects of stimulants. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 54 , 660–667 (2015).

Fotopoulos, N. H. et al. Cumulative exposure to ADHD medication is inversely related to hippocampus subregional volume in children. Neuroimage Clin. 31 , 102695 (2021).

Rubia, K. et al. Effects of stimulants on brain function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 76 , 616–628 (2014).

Faraone, S. V. et al. Practitioner review: emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder – implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 60 , 133–150 (2019).

Scassellati, C., Bonvicini, C., Faraone, S. V. & Gennarelli, M. Biomarkers and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 51 , 1003–1019.e20 (2012).

Bellato, A. et al. Practitioner review: clinical utility of the QbTest for the assessment and diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13901 (2023).

Stein, M. A., Snyder, S. M., Rugino, T. A. & Hornig, M. Commentary: objective aids for the assessment of ADHD – further clarification of what FDA approval for marketing means and why NEBA might help clinicians. A response to Arns et al. (2016). J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 57 , 770–771 (2016).

Lee, S. et al. Can neurocognitive outcomes assist measurement-based care for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? A systematic review and meta-analyses of the relationships among the changes in neurocognitive functions and clinical outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pharmacological and cognitive training interventions. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 32 , 250–277 (2022).

Gordon, M. et al. Symptoms versus impairment: the case for respecting DSM-IV’s Criterion D. J. Atten. Disord. 9 , 465–475 (2006).

Sibley, M. H. et al. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am. J. Psychiatry 175 , 140–149 (2018).

Mulraney, M. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: screening tools for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 61 , 982–996 (2022).

Coghill, D. et al. The management of ADHD in children and adolescents: bringing evidence to the clinic: perspective from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 32 , 1337–1361 (2021).

Fischer, M., Barkley, R., Fletcher, K. & Smallish, L. The stability of dimensions of behavior in ADHD and normal children over an 8-year followup. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 21 , 315–337 (1993).

Evans, S. W., Allen, J., Moore, S. & Strauss, V. Measuring symptoms and functioning of youth with ADHD in middle schools. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 33 , 695–706 (2005).

Chan, E., Fogler, J. M. & Hammerness, P. G. Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA 315 , 1997–2008 (2016).

Brinkman, W. B., Simon, J. O. & Epstein, J. N. Reasons why children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder stop and restart taking medicine. Acad. Pediatr. 18 , 273–280 (2018).

Sibley, M. H. et al. Defining ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood: optimizing sensitivity and specificity. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 58 , 655–662 (2017).

Biederman, J. & Spencer, T. J. Psychopharmacological interventions. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 17 , 439–458 (2008).

Biederman, J., Spencer, T. & Wilens, T. in Essentials of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (eds Wiener, J. M. & Dulcan, M.) 635–699 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2006).

Cooper, M. et al. Investigating late-onset ADHD: a population cohort investigation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59 , 1105–1113 (2018).

Mitchell, J. T. et al. A qualitative analysis of contextual factors relevant to suspected late-onset ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 25 , 724–735 (2021).

Waltereit, R., Ehrlich, S. & Roessner, V. First-time diagnosis of ADHD in adults: challenge to retrospectively assess childhood symptoms of ADHD from long-term memory. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 32 , 1333–1335 (2023).

Faraone, S. V. et al. Systematic review: nonmedical use of prescription stimulants: risk factors, outcomes, and risk reduction strategies. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 59 , 100–112 (2020).

Yeung, A., Ng, E. & Abi-Jaoude, E. TikTok and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a cross-sectional study of social media content quality. Can. J. Psychiatry 67 , 899–906 (2022).

Rommelse, N. et al. An evidenced-based perspective on the validity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of high intelligence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71 , 21–47 (2016).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG87. NICE https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/resources/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-1837699732933 (2019).

Wolraich, M. L. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 144 , e20192528 (2019).

Sugaya, L. S., Farhat, L. C., Califano, P. & Polanczyk, G. V. Efficacy of stimulants for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JCPP Adv. 3 , e12146 (2023).

Cortese, S. Pharmacologic treatment of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 1050–1056 (2020).

Poitras, V. & McCormack, S. Guanfacine hydrochloride extended-release for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: a review of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2018).

Iwanami, A., Saito, K., Fujiwara, M., Okutsu, D. & Ichikawa, H. Efficacy and safety of guanfacine extended-release in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 81 , 19m12979 (2020).

Cortese, S. et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 5 , 727–738 (2018).

O’Connor, L., Carbone, S., Gobbo, A., Gamble, H. & Faraone, S. V. Pediatric attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): 2022 updates on pharmacological management. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 16 , 799–812 (2023).

Faraone, S. V., McBurnett, K., Sallee, F. R., Steeber, J. & Lopez, F. A. Guanfacine extended release: a novel treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Ther. 35 , 1778–1793 (2013).

Childress, A. C. & Sallee, F. R. Revisiting clonidine: an innovative add-on option for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Drugs Today 48 , 207–217 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Buitelaar, J. et al. Toward precision medicine in ADHD. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16 , 900981 (2022).

Faraone, S. V. et al. Early response to SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) can predict efficacy outcome in pediatric subjects with ADHD: a machine learning post-hoc analysis of four randomized clinical trials. Psychiatry Res. 296 , 113664 (2021).

Faraone, S. V. et al. Predicting efficacy of viloxazine extended-release treatment in adults with ADHD using an early change in ADHD symptoms: machine learning post hoc analysis of a phase 3 clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 318 , 114922 (2022).

Newcorn, J. H., Sutton, V. K., Weiss, M. D. & Sumner, C. R. Clinical responses to atomoxetine in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the Integrated Data Exploratory Analysis (IDEA) study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 48 , 511–518 (2009).

Zhang, L. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications and long-term risk of cardiovascular diseases. JAMA Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.4294 (2023).

Cortese, S. et al. Practitioner review: current best practice in the management of adverse events during treatment with ADHD medications in children and adolescents. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 54 , 227–246 (2013).

Bloch, M. H., Panza, K. E., Landeros-Weisenberger, A. & Leckman, J. F. Meta-analysis: treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 48 , 884–893 (2009).

van de Loo-Neus, G. H., Rommelse, N. & Buitelaar, J. K. To stop or not to stop? How long should medication treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder be extended? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 , 584–599 (2011).

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., Morley, C. P. & Spencer, T. J. Effect of stimulants on height and weight: a review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 47 , 994–1009 (2008).

Biederman, J. et al. Growth trajectories in stimulant-treated children ages 6 to 12: an electronic medical record analysis. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 44 , e80–e87 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Associations of prescribed ADHD medication in pregnancy with pregnancy-related and offspring outcomes: a systematic review. CNS Drugs 34 , 731–747 (2020).

Bang Madsen, K. et al. In utero exposure to ADHD medication and long-term offspring outcomes. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 1739–1746 (2023).

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 , 275–289 (2013).

Faraone, S. V. & Antshel, K. M. Towards an evidence-based taxonomy of nonpharmacologic treatments for ADHD. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 23 , 965–972 (2014).

Sibley, M. H. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 7 , 415–428 (2023).

Langberg, J. M., Epstein, J. N., Becker, S. P., Girio-Herrera, E. & Vaughn, A. J. Evaluation of the homework, organization, and planning skills (HOPS) intervention for middle school students with ADHD as implemented by school mental health providers. Sch. Psych. Rev. 41 , 342–364 (2012).

Sibley, M. H. et al. Parent-teen behavior therapy + motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 84 , 699–712 (2016).

Groenman, A. P. et al. An individual participant data meta-analysis: behavioral treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 61 , 144–158 (2022).

Dekkers, T. J. et al. Meta-analysis: which components of parent training work for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 61 , 478–494 (2022).

Nimmo-Smith, V. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for adult ADHD: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 50 , 529–541 (2020).

Safren, S. A. et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 43 , 831–842 (2005).

Young, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial reporting functional outcomes of cognitive-behavioural therapy in medication-treated adults with ADHD and comorbid psychopathology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 267 , 267–276 (2017).

Tourjman, V. et al. Psychosocial interventions for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis by the CADDRA guidelines work group. Brain Sci. 12 , 1023 (2022).

Pan, M. R. et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy in medicated adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in multiple dimensions: a randomised controlled trial. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 272 , 235–255 (2022).

Lopez-Pinar, C., Martinez-Sanchis, S., Carbonell-Vaya, E., Sanchez-Meca, J. & Fenollar-Cortes, J. Efficacy of nonpharmacological treatments on comorbid internalizing symptoms of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. J. Atten. Disord. 24 , 456–478 (2020).

Liu, C. I., Hua, M. H., Lu, M. L. & Goh, K. K. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural-based interventions for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder extends beyond core symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Psychother. 96 , 543–559 (2023).

Lopez-Pinar, C., Martinez-Sanchis, S., Carbonell-Vaya, E., Fenollar-Cortes, J. & Sanchez-Meca, J. Long-term efficacy of psychosocial treatments for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Front. Psychol. 9 , 638 (2018).

Hirvikoski, T. et al. Psychoeducational groups for adults with ADHD and their significant others (PEGASUS): a pragmatic multicenter and randomized controlled trial. Eur. Psychiatry 44 , 141–152 (2017).

Groß, V. et al. Effectiveness of psychotherapy in adult ADHD: what do patients think? Results of the COMPAS study. J. Atten. Disord. 23 , 1047–1058 (2019).

Philipsen, A. et al. Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 1199–1210 (2015).

Young, Z., Moghaddam, N. & Tickle, A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Atten. Disord. 24 , 875–888 (2020).

Oliva, F. et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beyond core symptoms: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J. Affect. Disord. 292 , 475–486 (2021).

Schippers, L. M. et al. A qualitative and quantitative study of self-reported positive characteristics of individuals with ADHD. Front. Psychiatry 13 , 922788 (2022).

Salvat, H. et al. Nutrient intake, dietary patterns, and anthropometric variables of children with ADHD in comparison to healthy controls: a case-control study. BMC Pediatr. 22 , 70 (2022).

Ryu, S. A. et al. Associations between dietary intake and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) scores by repeated measurements in school-age children. Nutrients 14 , 2919 (2022).

Chang, J. P., Su, K. P., Mondelli, V. & Pariante, C. M. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials and biological studies. Neuropsychopharmacology 43 , 534–545 (2018).

Hunjan, A. K., Hübel, C., Lin, Y., Eley, T. C. & Breen, G. Association between polygenic propensity for psychiatric disorders and nutrient intake. Commun. Biol. 4 , 965 (2021).

Bloch, M. H. & Qawasmi, A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 50 , 991–1000 (2011).

Johnstone, J. M., Hughes, A., Goldenberg, J. Z., Romijn, A. R. & Rucklidge, J. J. Multinutrients for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 12 , 3394 (2020).

Nigg, J. T., Lewis, K., Edinger, T. & Falk, M. Meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, restriction diet, and synthetic food color additives. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 51 , 86–97.e8 (2012).

San Mauro Martin, I. et al. Impulsiveness in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder after an 8-week intervention with the Mediterranean diet and/or omega-3 fatty acids: a randomised clinical trial. Neurologia 37 , 513–523 (2022).

Khoshbakht, Y., Moghtaderi, F., Bidaki, R., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 60 , 3647–3658 (2021).

Huberts-Bosch, A. et al. Short-term effects of an elimination diet and healthy diet in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02256-y (2023).

Rubia, K., Westwood, S., Aggensteiner, P. M. & Brandeis, D. Neurotherapeutics for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review. Cells 10 , 2156 (2021).

Purper-Ouakil, D. et al. Personalized at-home neurofeedback compared to long-acting methylphenidate in children with ADHD: NEWROFEED, a European randomized noninferiority trial. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 63 , 187–198 (2022).

Riesco-Matias, P., Yela-Bernabe, J. R., Crego, A. & Sanchez-Zaballos, E. What do meta-analyses have to say about the efficacy of neurofeedback applied to children with ADHD? Review of previous meta-analyses and a new meta-analysis. J. Atten. Disord. 25 , 473–485 (2021).

Cortese, S. et al. Neurofeedback for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 55 , 444–455 (2016).

Bussalb, A. et al. Clinical and experimental factors influencing the efficacy of neurofeedback in ADHD: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 10 , 35 (2019).

Neurofeedback Collaborative Group Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of neurofeedback for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with 13-month follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 60 , 841–855 (2021).

Alegria, A. A. et al. Real-time fMRI neurofeedback in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38 , 3190–3209 (2017).

Lam, S. L. et al. Double-blind, sham-controlled randomized trial testing the efficacy of fMRI neurofeedback on clinical and cognitive measures in children with ADHD. Am. J. Psychiatry 179 , 947–958 (2022).

Criaud, M. et al. Increased left inferior fronto-striatal activation during error monitoring after fMRI neurofeedback of right inferior frontal cortex in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 27 , 102311 (2020).

Rubia, K. et al. Functional connectivity changes associated with fMRI neurofeedback of right inferior frontal cortex in adolescents with ADHD. Neuroimage 188 , 43–58 (2019).

Westwood, S. J., Radua, J. & Rubia, K. Noninvasive brain stimulation in children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 46 , E14–E33 (2021).

Hyde, J. et al. Efficacy of neurostimulation across mental disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis of 208 randomized controlled trials. Mol. Psychiatry 27 , 2709–2719 (2022).

Alyagon, U. et al. Alleviation of ADHD symptoms by non-invasive right prefrontal stimulation is correlated with EEG activity. Neuroimage Clin. 26 , 102206 (2020).

Westwood, S. J. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with cognitive training in adolescent boys with ADHD: a double-blind, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 53 , 497–512 (2023).

Leffa, D. T. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation vs sham for the treatment of inattention in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the TUNED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 847–856 (2022).

McGough, J. J. et al. Double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot study of trigeminal nerve stimulation for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 58 , 403–411.e3 (2019).

Denyer, H. et al. ADHD Remote Technology study of cardiometabolic risk factors and medication adherence (ART-CARMA): a multi-centre prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 22 , 813 (2022).

Hollis, C. et al. Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – a systematic and meta-review. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 58 , 474–503 (2017).

Kollins, S. H. et al. A novel digital intervention for actively reducing severity of paediatric ADHD (STARS-ADHD): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digital Health 2 , e168–e178 (2020).

Singh, L. J., Gaye, F., Cole, A. M., Chan, E. S. M. & Kofler, M. J. Central executive training for ADHD: effects on academic achievement, productivity, and success in the classroom. Neuropsychology 36 , 330–345 (2022).

Kofler, M. J. et al. A randomized controlled trial of central executive training (CET) versus inhibitory control training (ICT) for ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 88 , 738–756 (2020).

Westwood, S. J., Cortese, S., Rubia, K. & Sonuga-Barke, E. Computerised cognitive training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials with blinded and objective outcomes. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 1402–1414 (2023).

Wehmeier, P. M., Schacht, A. & Barkley, R. A. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J. Adolesc. Health 46 , 209–217 (2010).

Dona, S. W. A. et al. The impact of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on children’s health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Atten. Disord. 27 , 598–611 (2023).

Jans, T. et al. Does intensive multimodal treatment for maternal ADHD improve the efficacy of parent training for children with ADHD? A randomized controlled multicenter trial. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 56 , 1298–1313 (2015).

Kosheleff, A. R., Mason, O., Jain, R., Koch, J. & Rubin, J. Functional impairments associated with ADHD in adulthood and the impact of pharmacological treatment. J. Atten. Disord. 27 , 669–697 (2023).

Chien, W. C. et al. The risk of injury in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide, matched-cohort, population-based study in Taiwan. Res. Dev. Disabil. 65 , 57–73 (2017).

Klein, R. G., Pine, D. S. & Klein, D. F. Resolved: mania is mistaken for ADHD in prepubertal children. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 37 , 1093–1096 (1998).

Pawaskar, M., Fridman, M., Grebla, R. & Madhoo, M. Comparison of quality of life, productivity, functioning and self-esteem in adults diagnosed with ADHD and with symptomatic ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 24 , 136–144 (2019).

Philipsen, A. et al. Early maladaptive schemas in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 9 , 101–111 (2017).

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30 , 473–483 (1992).

Endicott, J., Nee, J., Harrison, W. & Blumenthal, R. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 29 , 321–326 (1993).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brod, M., Johnston, J., Able, S. & Swindle, R. Validation of the adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder quality-of-life scale (AAQoL): a disease-specific quality-of-life measure. Qual. Life Res. 15 , 117–129 (2006).

Weiss, M. D. et al. Moderators and mediators of symptoms and quality of life outcomes in an open-label study of adults treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71 , 381–390 (2010).

Coghill, D. R., Banaschewski, T., Soutullo, C., Cottingham, M. G. & Zuddas, A. Systematic review of quality of life and functional outcomes in randomized placebo-controlled studies of medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 26 , 1283–1307 (2017).

Chang, Z. et al. Risks and benefits of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication on behavioral and neuropsychiatric outcomes: a qualitative review of pharmacoepidemiology studies using linked prescription databases. Biol. Psychiatry 86 , 335–343 (2019).

Chang, Z. et al. Association between medication use for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of motor vehicle crashes. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 597–603 (2017).

Quinn, P. D. et al. ADHD medication and substance-related problems. Am. J. Psychiatry 174 , 877–885 (2017).

Lu, Y. et al. Association between medication use and performance on higher education entrance tests in individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 815–822 (2017).

Chen, V. C. H. et al. Methylphenidate and mortality in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: population-based cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 220 , 64–72 (2022).

Agarwal, R., Goldenberg, M., Perry, R. & William Ishak, W. The quality of life of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 9 , 10–21 (2012).

Adler, L. A. et al. Atomoxetine treatment in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety 26 , 212–221 (2009).

Adler, L. A. et al. Once-daily atomoxetine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a 6-month, double-blind trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 29 , 44–50 (2009).

Adler, L. A. et al. Self-reported quality of life in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and executive function impairment treated with lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. BMC Psychiatry 13 , 253 (2013).

Spencer, T. J. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-specific quality of life with triple-bead mixed amphetamine salts (SPD465) in adults: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 69 , 1766–1775 (2008).

Durell, T. M. et al. Atomoxetine treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young adults with assessment of functional outcomes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 33 , 45–54 (2013).

Goodman, D. W., Ginsberg, L., Weisler, R. H., Cutler, A. J. & Hodgkins, P. An interim analysis of the quality of life, effectiveness, safety, and tolerability (QU.E.S.T.) evaluation of mixed amphetamine salts extended release in adults with ADHD. CNS Spectr. 10 , 26–34 (2005).

Lücke, C. et al. Long-term improvement of quality of life in adult ADHD – results of the randomized multimodal COMPAS trial. Int. J. Ment. Health 50 , 250–270 (2021).

Tsujii, N. et al. Effect of continuing and discontinuing medications on quality of life after symptomatic remission in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 81 , 19r13015 (2020).

Ramsay, J. R. Assessment and monitoring of treatment response in adult ADHD patients: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 13 , 221–232 (2017).

Hegvik, T. A. et al. Druggable genome in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its co-morbid conditions. New avenues for treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 26 , 4004–4015 (2021).

Malik, M. A., Faraone, S. V., Michoel, T. & Haavik, J. Use of big data and machine learning algorithms to extract possible treatment targets in neurodevelopmental disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 250 , 108530 (2023).

Hoogman, M., Stolte, M., Baas, M. & Kroesbergen, E. Creativity and ADHD: a review of behavioral studies, the effect of psychostimulants and neural underpinnings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 119 , 66–85 (2020).

Hess, J. L. et al. A polygenic resilience score moderates the genetic risk for schizophrenia: replication in 18,090 cases and 28,114 controls from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet . 195 , e32957 (2023).

Hou, J. et al. Polygenic resilience scores capture protective genetic effects for Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 12 , 296 (2022).

Nigg, J. T. Considerations toward an epigenetic and common pathways theory of mental disorder. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 132 , 297–313 (2023).

Garcia-Argibay, M. et al. Predicting childhood and adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder onset: a nationwide deep learning approach. Mol. Psychiatry 28 , 1232–1239 (2022).

Biederman, J. et al. Evidence of low adherence to stimulant medication among children and youths with ADHD: an electronic health records study. Psychiatr. Serv. 70 , 874–880 (2019).

Biederman, J. et al. Further evidence of low adherence to stimulant treatment in adult ADHD: an electronic medical record study examining timely renewal of a stimulant prescription. Psychopharmacology 237 , 2835–2843 (2020).

Brikell, I. et al. ADHD medication discontinuation and persistence across the lifespan: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet Psychiatry 11 , 16–26 (2024).

Manalili, M. A. R. et al. From puzzle to progress: how engaging with neurodiversity can improve cognitive science. Cogn. Sci. 47 , e13255 (2023).

Rostain, A., Jensen, P. S., Connor, D. F., Miesle, L. M. & Faraone, S. V. Toward quality care in ADHD: defining the goals of treatment. J. Atten. Disord. 19 , 99–117 (2015).

Higdon, C., Blader, J., Kalari, V. K. & Fornari, V. M. Measurement-based care in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavior disorders. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 29 , 663–674 (2020).

Faraone, S. V. et al. The adult ADHD quality measures initiative. J. Atten. Disord. 23 , 1063–1078 (2019).

Callen, E. F. et al. Progress and pitfalls in the provision of quality care for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary care. J. Atten. Disord. 27 , 575–582 (2023).

Demontis, D. et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 51 , 63–75 (2019).

Thapar, A. et al. Psychiatric gene discoveries shape evidence on ADHD’s biology. Mol. Psychiatry 21 , 1202–1207 (2015).

Dark, C., Homman-Ludiye, J. & Bryson-Richardson, R. J. The role of ADHD associated genes in neurodevelopment. Dev. Biol. 438 , 69–83 (2018).

Sollis, E. et al. Equivalent missense variant in the FOXP2 and FOXP1 transcription factors causes distinct neurodevelopmental disorders. Hum. Mutat. 38 , 1542–1554 (2017).

Harrington, A. J. et al. MEF2C regulates cortical inhibitory and excitatory synapses and behaviors relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders. Elife 5 , e20059 (2016).

Lionel, A. C. et al. Rare copy number variation discovery and cross-disorder comparisons identify risk genes for ADHD. Sci. Transl. Med. 3 , 95ra75 (2011).

Lee, P. H. et al. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179 , 1469–1482.e11 (2019).

Cortese, S., Newcorn, J. H. & Coghill, D. A practical, evidence-informed approach to managing stimulant-refractory attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). CNS Drugs 35 , 1035–1051 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

S.V.F. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 965381), NIMH (grants U01AR076092-01A1, 1R21MH1264940, R01MH116037 and 1R01NS128535-01), Oregon Health and Science University, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Noven Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, and Supernus Pharmaceutical Company. M.A.B. is supported by a Senior Research Fellowship (level B) from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; 1154378). His research programme is supported by the NHMRC (2010899) and Medical Research Future Fund of Australia (MRF2006438, EPCD000002). I.B. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 965381). S.C., NIHR Research Professor (NIHR303122), is funded by the NIHR for this research project. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. S.C. is also supported by NIHR grants NIHR203684, NIHR203035, NIHR130077, NIHR128472 and RP-PG-0618-20003 and by grant 101095568-HORIZONHLTH-2022-DISEASE-07-03 from the European Research Executive Agency. C.A.H. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 965381), and ZonMW (grants 636340003 and 636340002). C.H. is supported by the NIHR (grants MIC-2016-003 and NIHR203310), and by the UKRI Medical Research Council (grant MR/T046864/1). J.H.N. is supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01; HD093612) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21; DA054281). A.P. is currently supported by funding from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (grant NIHR203035), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 945151), German Research Foundation (grant PH 177/7-1), Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (grant IBehave), Ministry of Research and Education (grants 01NVF20004 and 01IS22085D (Eureka Cluster on software innovation)). G.V.P. is supported by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grant 2016/22455-8), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; grant 310582/2017-2). K.R. is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (grants NIHR130077 and NIHR203684) and the UK Department of Health and Social Care via the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) for Mental Health at South London and the Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and the IoPPN, King’s College London. M.H.S. is supported by the Institute of Education Sciences (grant R305A210462) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grants R34 MH125037 and R34 MH122225). J.K.B. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreements 115300 and 777394 (EU-AIMS and AIMS-2-TRIALS), 847818 (CANDY), and 847879 (PRIME)).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departments of Psychiatry and of Neuroscience and Physiology, Norton College of Medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA

Stephen V. Faraone

School of Psychological Sciences, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Mark A. Bellgrove

Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Isabell Brikell

Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

Centre for Innovation in Mental Health, School of Psychology, Faculty of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Samuele Cortese

Clinical and Experimental Sciences (CNS and Psychiatry), Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Solent NHS Trust, Southampton, UK

Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone, New York University Child Study Center, New York City, NY, USA

DiMePRe-J-Department of Precision and Rigenerative Medicine-Jonic Area, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy

Interdisciplinary Center Psychopathology and Emotion regulation (ICPE), Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

Catharina A. Hartman

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) MindTech MedTech Co-operative and NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Mental Health, Mental Health and Clinical Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Chris Hollis

Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Jeffrey H. Newcorn

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Alexandra Philipsen

Department of Psychiatry, Faculdade de Medicina FMUSP, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Guilherme V. Polanczyk

Department of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neurosciences, King’s College London, London, UK

Katya Rubia

Department of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Transcampus Professor KCL-Dresden, Technical University, Dresden, Germany

University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

Margaret H. Sibley

Department of Cognitive Neuroscience, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Jan K. Buitelaar

Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Introduction (S.V.F. and J.K.B.); Epidemiology (C.A.H. and G.V.P.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (I.B., K.R., M.A.B. and S.V.F.); Diagnosis and screening (M.H.S. and S.C.); Management (J.H.N., S.C., A.P., M.H.S., J.K.B., M.A.B., K.R. and C.H.); Quality of life (G.V.P. and A.P.); Outlook (J.K.B. and S.V.F.). Aside from the first and last authors, authorship is alphabetical. All authors extensively commented on each other’s sections.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephen V. Faraone .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

S.V.F. in the past year received income, potential income, travel expenses, continuing education support and/or research support from Aardvark, Aardwolf, AIMH, Tris, Otsuka, Ironshore, Kanjo, Johnson & Johnson/Kenvue, KemPharm/Corium, Akili, Supernus, Atentiv, Noven, Sky Therapeutics, Axsome and Genomind; with his institution, he has US patent US20130217707 A1 for the use of sodium–hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD; he also receives royalties from books published by Guilford Press ( Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health ), Oxford University Press ( Schizophrenia: The Facts ) and Elsevier ( ADHD: Non-Pharmacologic Interventions ); and he is Program Director of www.ADHDEvidence.org and www.ADHDinAdults.com . S.C. declares honoraria and reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses for lectures from the following non-profit associations: Association for Child and Adolescent Central Health (ACAMH), Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA), British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP), and Healthcare Convention for educational activity on ADHD. C.H. was a member of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) ADHD Guideline Committee (CG87); has received honoraria for lectures from BAP; and is a member of the European ADHD Guideline Group (EAGG) (eunethydis.eu/eunethydis-initiatives/european-adhd-guideline-group/). J.H.N. in the past year is/has been an adviser and/or consultant for Corium, Hippo T&C, Ironshore, Lumos, Medice, MindTension, OnDosis, Otsuka, Signant Health and Supernus; he has received research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and Otsuka; he also has received honoraria from for disease state presentations from Otsuka, and served as a consultant for the US National Football League. A.P. declares that she served on advisory boards, gave lectures, performed phase III studies and received travel grants within the last 5 years from MEDICE Arzneimittel, Pütter GmbH and Co KG, Takeda, Boehringer and Janssen-Cilag, and receives royalties from books published by Elsevier, Hogrefe, MWV, Kohlhammer, Karger, Oxford University Press, Thieme, Springer and Schattauer; she is a member of the German ADHD Guideline Group, and is an author of the Updated European Consensus Statement. G.V.P. has served as a speaker and/or consultant to Abbott, Ache, Medice, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer and Takeda, and receives authorship royalties from Manole Editors. K.R. has received a grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for another project and consulting fees from Supernus and Lundbeck. M.H.S. has consulted with Supernus Pharmaceuticals and Tieffenbacher Pharmaceuticals in the past 12 months, and receives book royalties from Guilford Press. J.K.B. has been in the past 3 years a consultant to/member of advisory board of and/or speaker for Takeda, Roche, Medice, Angelini, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Servier; he is not an employee of any of these companies, and is not a stock shareholder of any of these companies; he has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents and royalties. M.A.B. declares travel expenses and speaking fees attached to conference presentations and professional groups. I.B. and C.A.H. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Disease Primers thanks S. Gau, L. J. Wang, M. Weiss and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Faraone, S.V., Bellgrove, M.A., Brikell, I. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 10 , 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00495-0

Download citation

Accepted : 16 January 2024

Published : 22 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-024-00495-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The impact of psychological theory on the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults: A scoping review

Contributed equally to this work with: Rebecca E. Champ

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Nursing and Midwifery, School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom

Roles Supervision

¶ ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation School of Health and Life Sciences, Teeside University, Middlesbrough, United Kingdom

- Rebecca E. Champ,

- Marios Adamou,

- Barry Tolchard

- Published: December 21, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261247

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Psychological theory and interpretation of research are key elements influencing clinical treatment development and design in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Research-based treatment recommendations primarily support Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), an extension of the cognitive behavioural theory, which promotes a deficit-focused characterisation of ADHD and prioritises symptom reduction and cognitive control of self-regulation as treatment outcomes. A wide variety of approaches have developed to improve ADHD outcomes in adults, and this review aimed to map the theoretical foundations of treatment design to understand their impact. A scoping review and analysis were performed on 221 documents to compare the theoretical influences in research, treatment approach, and theoretical citations. Results showed that despite variation in the application, current treatments characterise ADHD from a single paradigm of cognitive behavioural theory. A single theoretical perspective is limiting research for effective treatments for ADHD to address ongoing issues such as accommodating context variability and heterogeneity. Research into alternative theoretical characterisations of ADHD is recommended to provide treatment design opportunities to better understand and address symptoms.

Citation: Champ RE, Adamou M, Tolchard B (2021) The impact of psychological theory on the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0261247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261247

Editor: Gerard Hutchinson, University of the West Indies at Saint Augustine, TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Received: May 21, 2021; Accepted: November 25, 2021; Published: December 21, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Champ et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction