- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

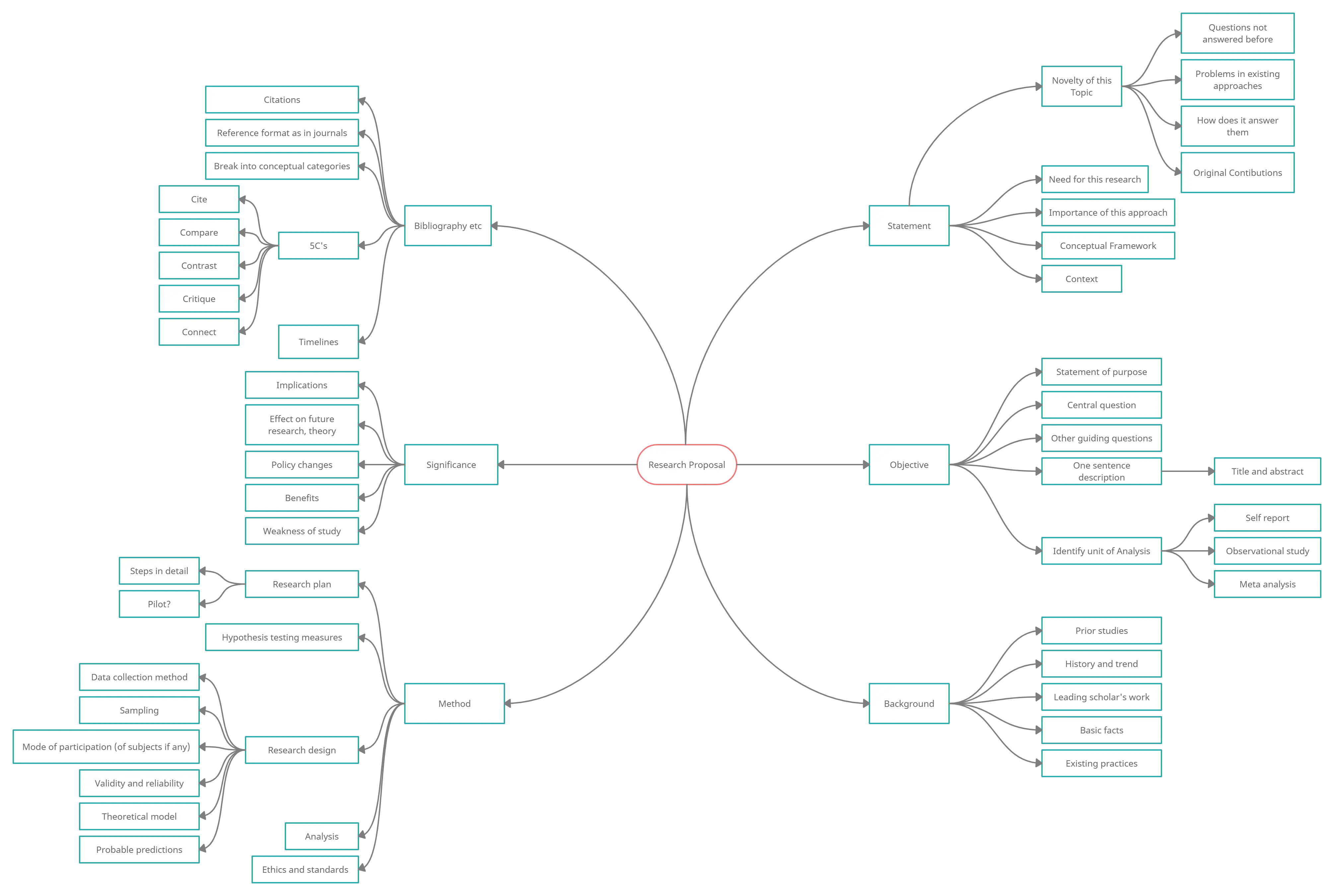

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

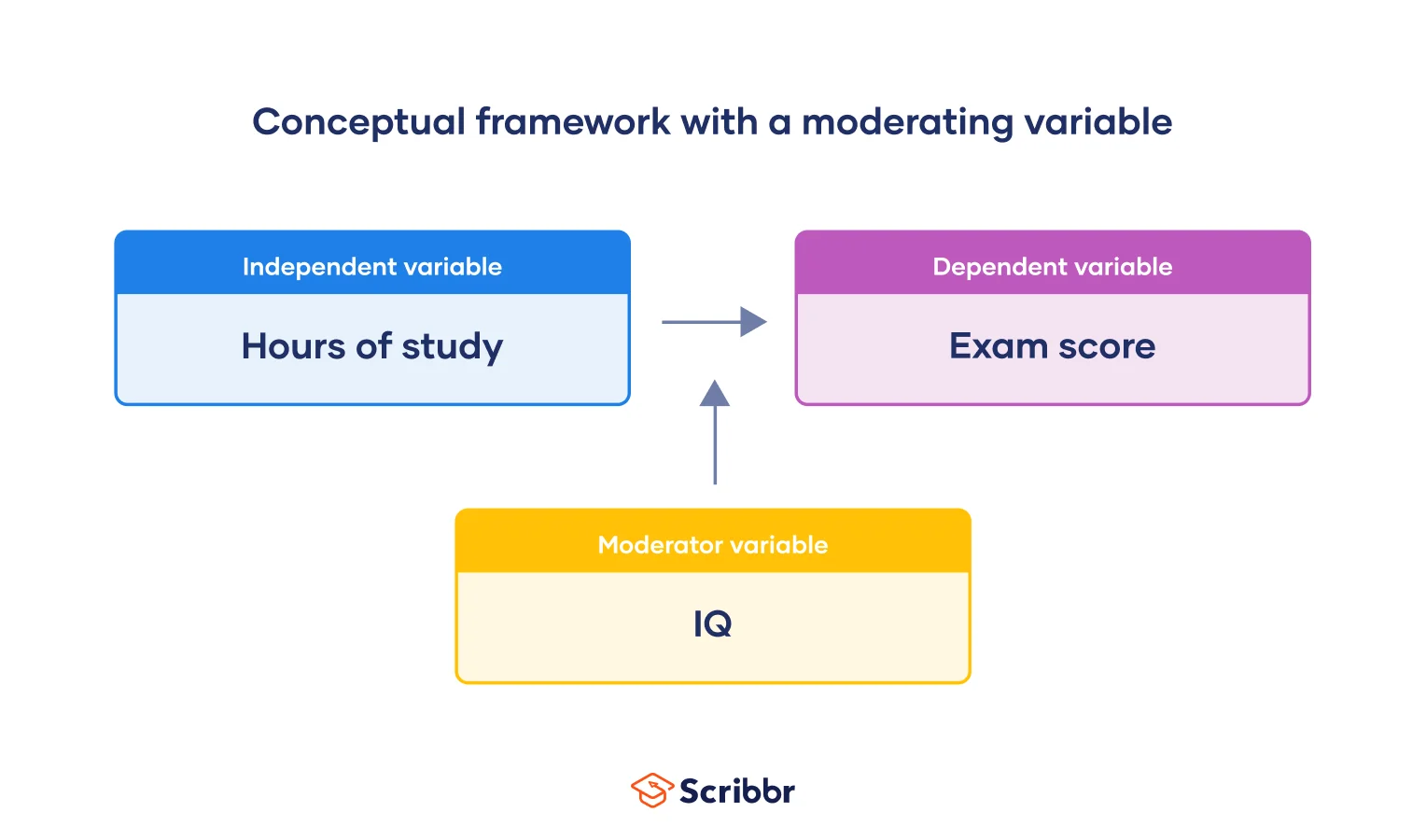

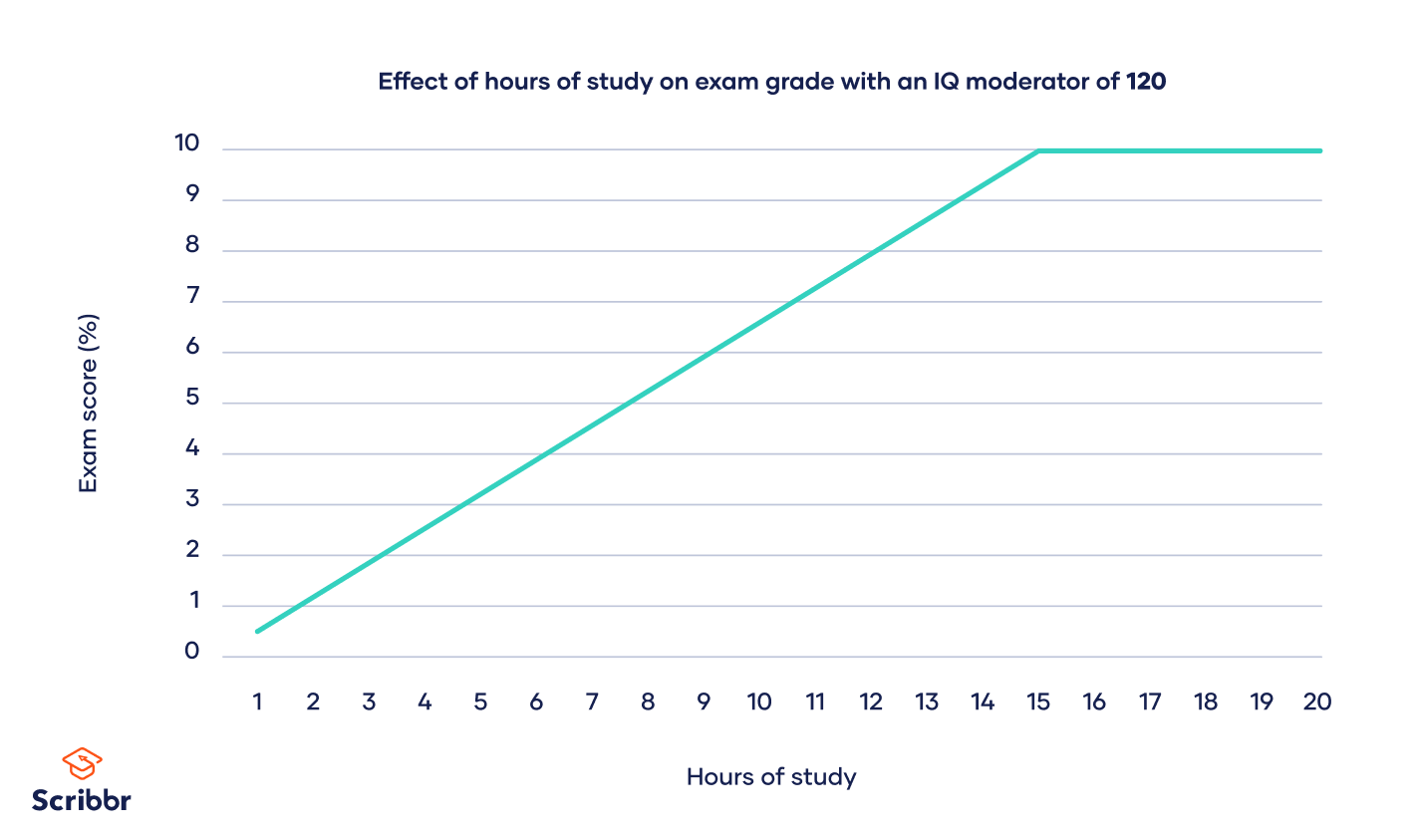

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

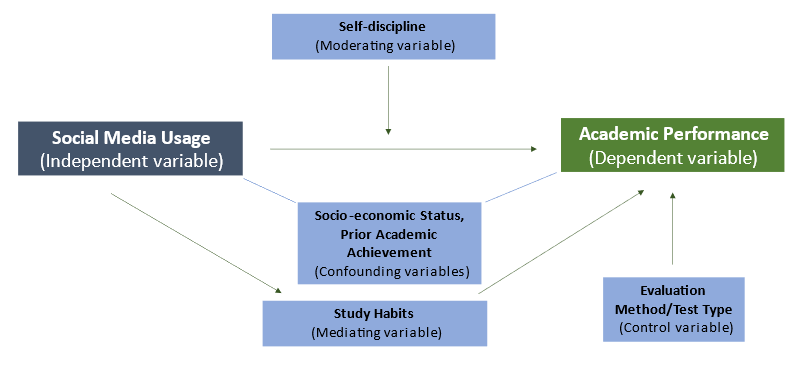

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 9:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Published on October 14, 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Tegan George.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your paper or dissertation topic is relevant and grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualizes your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis , or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalizations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyze The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviorist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarizing and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organize by theory cluster

- Organize by date

It’s important that the information in your theoretical framework is clear for your reader. Make sure to ask a friend to read this section for you, or use a professional proofreading service .

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis , or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

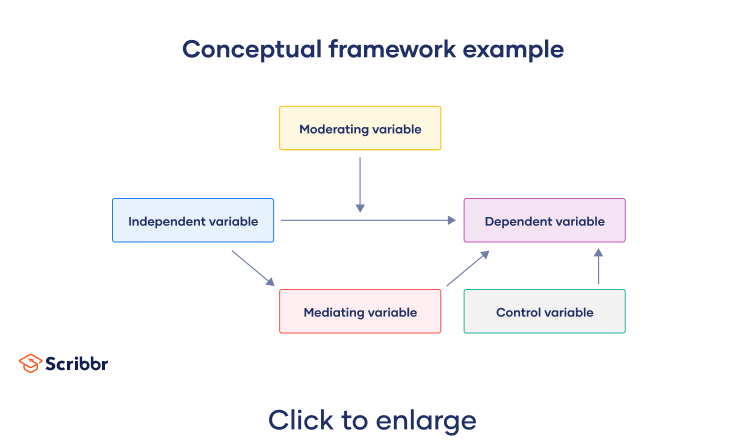

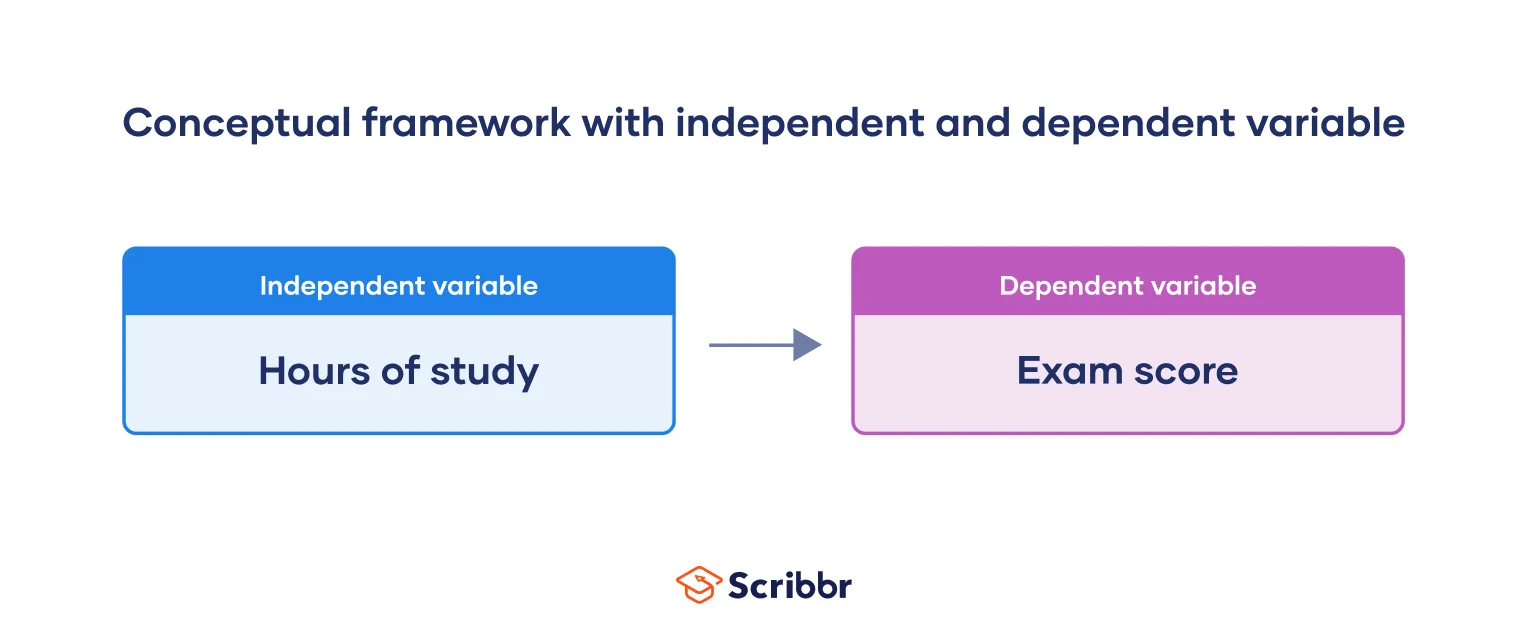

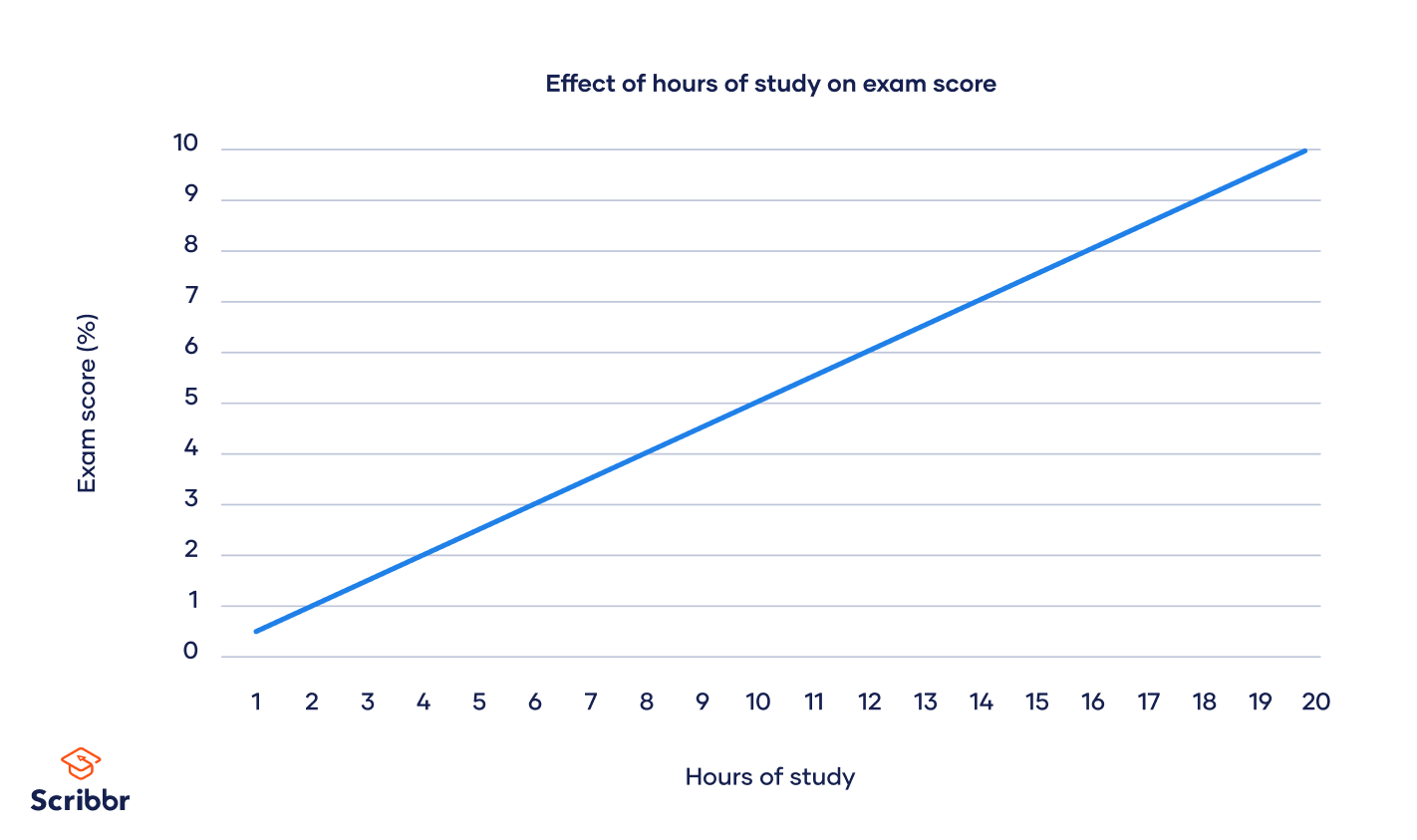

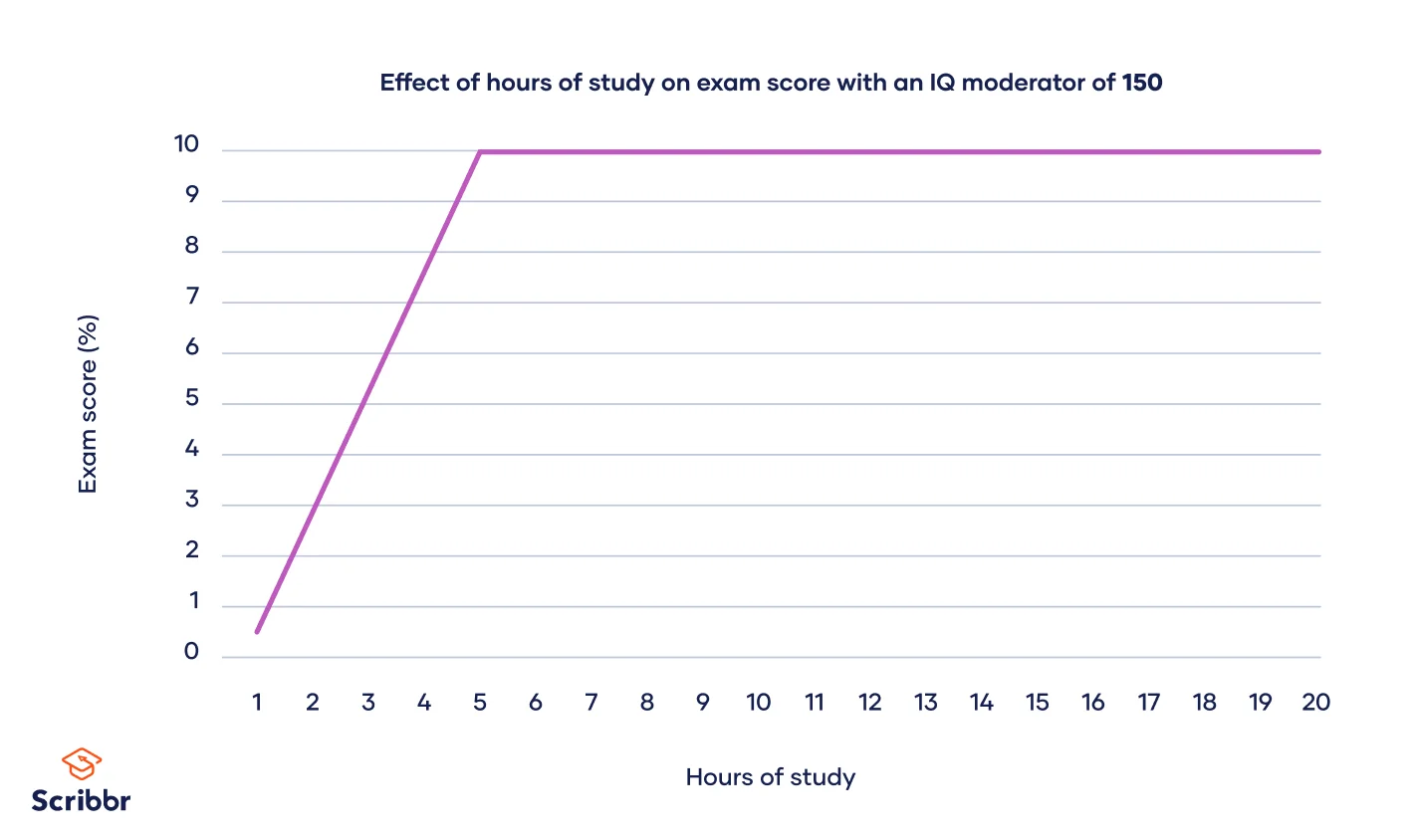

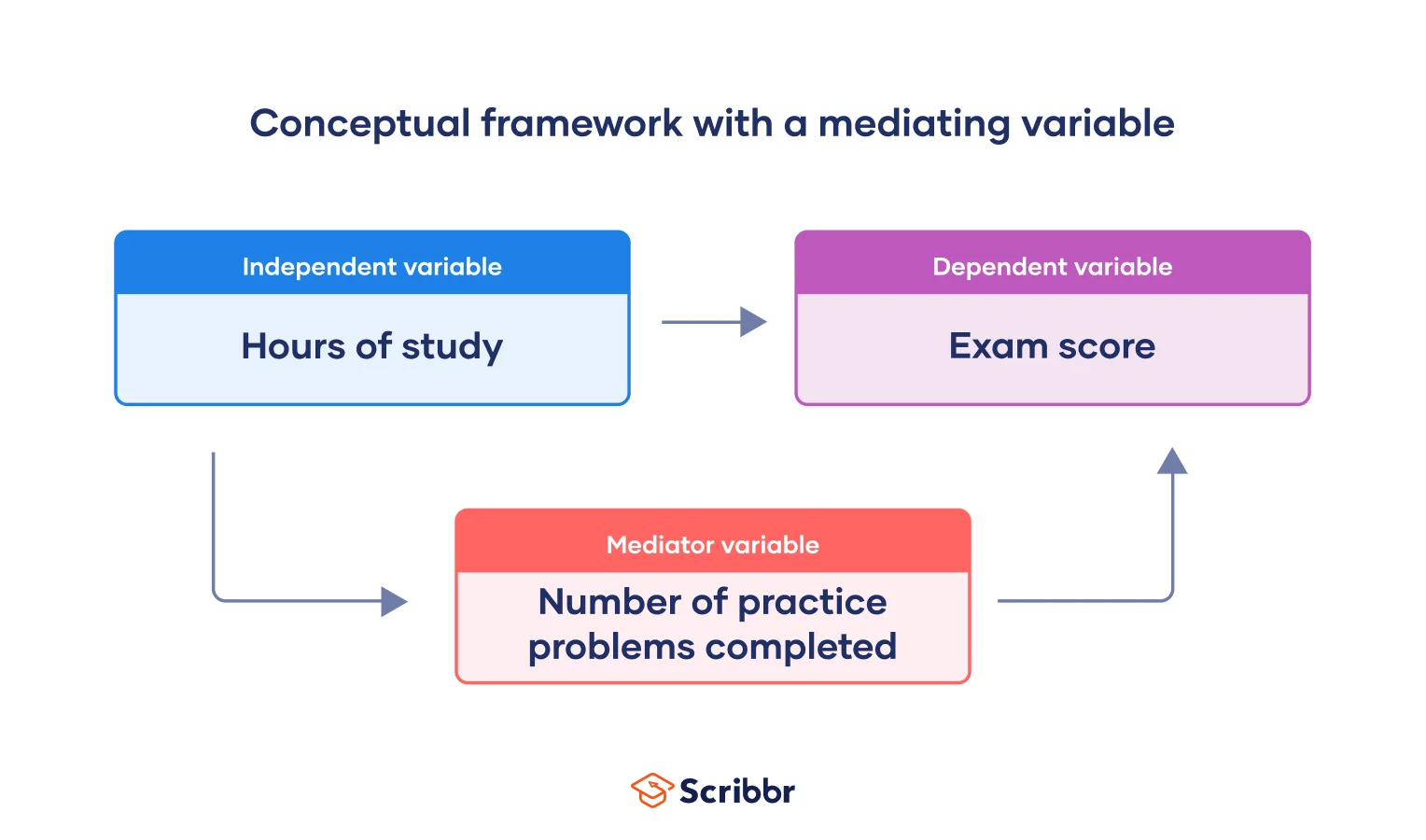

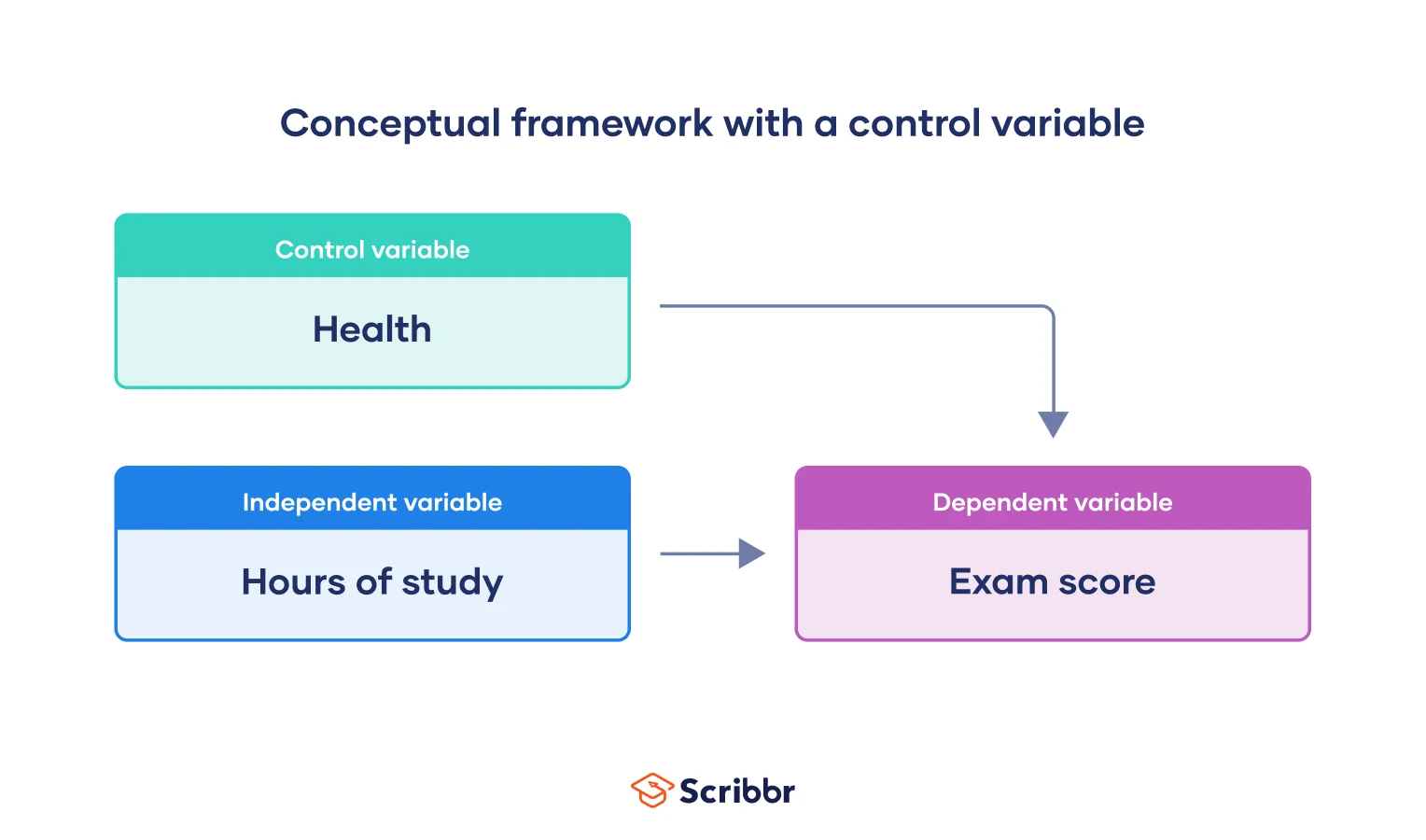

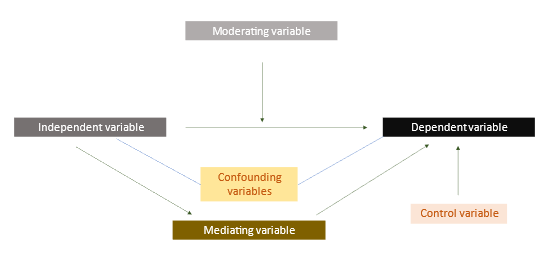

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing. Scribbr. Retrieved September 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

How to Use a Conceptual Framework for Better Research

A conceptual framework in research is not just a tool but a vital roadmap that guides the entire research process. It integrates various theories, assumptions, and beliefs to provide a structured approach to research. By defining a conceptual framework, researchers can focus their inquiries and clarify their hypotheses, leading to more effective and meaningful research outcomes.

What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework is essentially an analytical tool that combines concepts and sets them within an appropriate theoretical structure. It serves as a lens through which researchers view the complexities of the real world. The importance of a conceptual framework lies in its ability to serve as a guide, helping researchers to not only visualize but also systematically approach their study.

Key Components and to be Analyzed During Research

- Theories: These are the underlying principles that guide the hypotheses and assumptions of the research.

- Assumptions: These are the accepted truths that are not tested within the scope of the research but are essential for framing the study.

- Beliefs: These often reflect the subjective viewpoints that may influence the interpretation of data.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Together, these components help to define the conceptual framework that directs the research towards its ultimate goal. This structured approach not only improves clarity but also enhances the validity and reliability of the research outcomes. By using a conceptual framework, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and focus on essential variables and relationships.

For practical examples and to see how different frameworks can be applied in various research scenarios, you can Explore Conceptual Framework Examples .

Different Types of Conceptual Frameworks Used in Research

Understanding the various types of conceptual frameworks is crucial for researchers aiming to align their studies with the most effective structure. Conceptual frameworks in research vary primarily between theoretical and operational frameworks, each serving distinct purposes and suiting different research methodologies.

Theoretical vs Operational Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are built upon existing theories and literature, providing a broad and abstract understanding of the research topic. They help in forming the basis of the study by linking the research to already established scholarly works. On the other hand, operational frameworks are more practical, focusing on how the study’s theories will be tested through specific procedures and variables.

- Theoretical frameworks are ideal for exploratory studies and can help in understanding complex phenomena.

- Operational frameworks suit studies requiring precise measurement and data analysis.

Choosing the Right Framework

Selecting the appropriate conceptual framework is pivotal for the success of a research project. It involves matching the research questions with the framework that best addresses the methodological needs of the study. For instance, a theoretical framework might be chosen for studies that aim to generate new theories, while an operational framework would be better suited for testing specific hypotheses.

Benefits of choosing the right framework include enhanced clarity, better alignment with research goals, and improved validity of research outcomes. Tools like Table Chart Maker can be instrumental in visually comparing the strengths and weaknesses of different frameworks, aiding in this crucial decision-making process.

Real-World Examples of Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Understanding the practical application of conceptual frameworks in research can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your studies. Here, we explore several real-world case studies that demonstrate the pivotal role of conceptual frameworks in achieving robust research conclusions.

- Healthcare Research: In a study examining the impact of lifestyle choices on chronic diseases, researchers used a conceptual framework to link dietary habits, exercise, and genetic predispositions. This framework helped in identifying key variables and their interrelations, leading to more targeted interventions.

- Educational Development: Educational theorists often employ conceptual frameworks to explore the dynamics between teaching methods and student learning outcomes. One notable study mapped out the influences of digital tools on learning engagement, providing insights that shaped educational policies.

- Environmental Policy: Conceptual frameworks have been crucial in environmental research, particularly in studies on climate change adaptation. By framing the relationships between human activity, ecological changes, and policy responses, researchers have been able to propose more effective sustainability strategies.

Adapting conceptual frameworks based on evolving research data is also critical. As new information becomes available, it’s essential to revisit and adjust the framework to maintain its relevance and accuracy, ensuring that the research remains aligned with real-world conditions.

For those looking to visualize and better comprehend their research frameworks, Graphic Organizers for Conceptual Frameworks can be an invaluable tool. These organizers help in structuring and presenting research findings clearly, enhancing both the process and the presentation of your research.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Own Conceptual Framework

Creating a conceptual framework is a critical step in structuring your research to ensure clarity and focus. This guide will walk you through the process of building a robust framework, from identifying key concepts to refining your approach as your research evolves.

Building Blocks of a Conceptual Framework

- Identify and Define Main Concepts and Variables: Start by clearly identifying the main concepts, variables, and their relationships that will form the basis of your research. This could include defining key terms and establishing the scope of your study.

- Develop a Hypothesis or Primary Research Question: Formulate a central hypothesis or question that guides the direction of your research. This will serve as the foundation upon which your conceptual framework is built.

- Link Theories and Concepts Logically: Connect your identified concepts and variables with existing theories to create a coherent structure. This logical linking helps in forming a strong theoretical base for your research.

Visualizing and Refining Your Framework

Using visual tools can significantly enhance the clarity and effectiveness of your conceptual framework. Decision Tree Templates for Conceptual Frameworks can be particularly useful in mapping out the relationships between variables and hypotheses.

Map Your Framework: Utilize tools like Creately’s visual canvas to diagram your framework. This visual representation helps in identifying gaps or overlaps in your framework and provides a clear overview of your research structure.

Analyze and Refine: As your research progresses, continuously evaluate and refine your framework. Adjustments may be necessary as new data comes to light or as initial assumptions are challenged.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your conceptual framework is not only well-defined but also adaptable to the changing dynamics of your research.

Practical Tips for Utilizing Conceptual Frameworks in Research

Effectively utilizing a conceptual framework in research not only streamlines the process but also enhances the clarity and coherence of your findings. Here are some practical tips to maximize the use of conceptual frameworks in your research endeavors.

- Setting Clear Research Goals: Begin by defining precise objectives that are aligned with your research questions. This clarity will guide your entire research process, ensuring that every step you take is purposeful and directly contributes to your overall study aims. \

- Maintaining Focus and Coherence: Throughout the research, consistently refer back to your conceptual framework to maintain focus. This will help in keeping your research aligned with the initial goals and prevent deviations that could dilute the effectiveness of your findings.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Use your conceptual framework as a lens through which to view and interpret data. This approach ensures that the data analysis is not only systematic but also meaningful in the context of your research objectives. For more insights, explore Research Data Analysis Methods .

- Presenting Research Findings: When it comes time to present your findings, structure your presentation around the conceptual framework . This will help your audience understand the logical flow of your research and how each part contributes to the whole.

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls: Be vigilant about common errors such as overcomplicating the framework or misaligning the research methods with the framework’s structure. Keeping it simple and aligned ensures that the framework effectively supports your research.

By adhering to these tips and utilizing tools like 7 Essential Visual Tools for Social Work Assessment , researchers can ensure that their conceptual frameworks are not only robust but also practically applicable in their studies.

How Creately Enhances the Creation and Use of Conceptual Frameworks

Creating a robust conceptual framework is pivotal for effective research, and Creately’s suite of visual tools offers unparalleled support in this endeavor. By leveraging Creately’s features, researchers can visualize, organize, and analyze their research frameworks more efficiently.

- Visual Mapping of Research Plans: Creately’s infinite visual canvas allows researchers to map out their entire research plan visually. This helps in understanding the complex relationships between different research variables and theories, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of the research process.

- Brainstorming with Mind Maps: Using Mind Mapping Software , researchers can generate and organize ideas dynamically. Creately’s intelligent formatting helps in brainstorming sessions, making it easier to explore multiple topics or delve deeply into specific concepts.

- Centralized Data Management: Creately enables the importation of data from multiple sources, which can be integrated into the visual research framework. This centralization aids in maintaining a cohesive and comprehensive overview of all research elements, ensuring that no critical information is overlooked.

- Communication and Collaboration: The platform supports real-time collaboration, allowing teams to work together seamlessly, regardless of their physical location. This feature is crucial for research teams spread across different geographies, facilitating effective communication and iterative feedback throughout the research process.

Moreover, the ability t Explore Conceptual Framework Examples directly within Creately inspires researchers by providing practical templates and examples that can be customized to suit specific research needs. This not only saves time but also enhances the quality of the conceptual framework developed.

In conclusion, Creately’s tools for creating and managing conceptual frameworks are indispensable for researchers aiming to achieve clear, structured, and impactful research outcomes.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Chiraag George is a communication specialist here at Creately. He is a marketing junkie that is fascinated by how brands occupy consumer mind space. A lover of all things tech, he writes a lot about the intersection of technology, branding and culture at large.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Theoretical frameworks for qualitative research

Tess Tsindos

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe qualitative frameworks.

- Explain why frameworks are used in qualitative research.

- Identify various frameworks used in qualitative research.

What is a Framework?

A framework is a set of broad concepts or principles used to guide research. As described by Varpio and colleagues 1 , a framework is a logically developed and connected set of concepts and premises – developed from one or more theories – that a researcher uses as a scaffold for their study. The researcher must define any concepts and theories that will provide the grounding for the research and link them through logical connections, and must relate these concepts to the study that is being carried out. In using a particular theory to guide their study, the researcher needs to ensure that the theoretical framework is reflected in the work in which they are engaged.

It is important to acknowledge that the terms ‘theories’ ( see Chapter 3 ), ‘frameworks’ and ‘paradigms’ are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there are differences between these concepts. To complicate matters further, theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks are also used. In addition, quantitative and qualitative researchers usually start from different standpoints in terms of theories and frameworks.

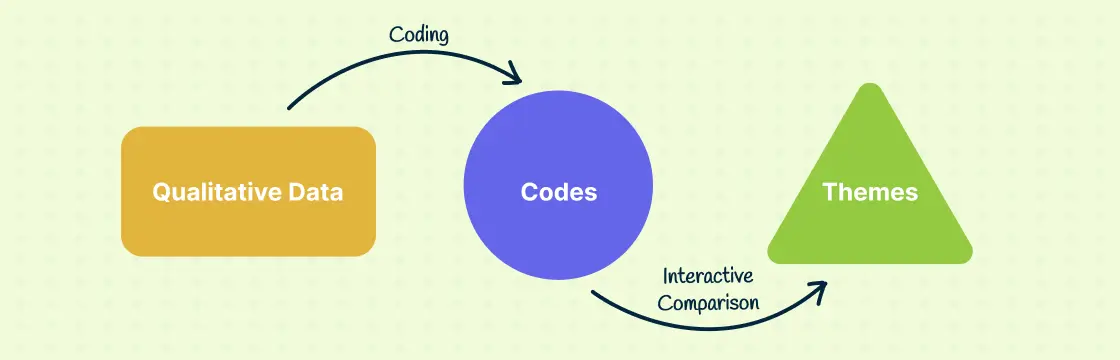

A diagram by Varpio and colleagues demonstrates the similarities and differences between theories and frameworks, and how they influence research approaches. 1(p991) The diagram displays the objectivist or deductive approach to research on the left-hand side. Note how the conceptual framework is first finalised before any research is commenced, and it involves the articulation of hypotheses that are to be tested using the data collected. This is often referred to as a top-down approach and/or a general (theory or framework) to a specific (data) approach.

The diagram displays the subjectivist or inductive approach to research on the right-hand side. Note how data is collected first, and through data analysis, a tentative framework is proposed. The framework is then firmed up as new insights are gained from the data analysis. This is referred to as a specific (data) to general (theory and framework) approach .

Why d o w e u se f rameworks?

A framework helps guide the questions used to elicit your data collection. A framework is not prescriptive, but it needs to be suitable for the research question(s), setting and participants. Therefore, the researcher might use different frameworks to guide different research studies.

A framework informs the study’s recruitment and sampling, and informs, guides or structures how data is collected and analysed. For example, a framework concerned with health systems will assist the researcher to analyse the data in a certain way, while a framework concerned with psychological development will have very different ways of approaching the analysis of data. This is due to the differences underpinning the concepts and premises concerned with investigating health systems, compared to the study of psychological development. The framework adopted also guides emerging interpretations of the data and helps in comparing and contrasting data across participants, cases and studies.

Some examples of foundational frameworks used to guide qualitative research in health services and public health:

- The Behaviour Change Wheel 2

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 3

- Theoretical framework of acceptability 4

- Normalization Process Theory 5

- Candidacy Framework 6

- Aboriginal social determinants of health 7(p8)

- Social determinants of health 8

- Social model of health 9,10

- Systems theory 11

- Biopsychosocial model 12

- Discipline-specific models

- Disease-specific frameworks

E xamples of f rameworks

In Table 4.1, citations of published papers are included to demonstrate how the particular framework helps to ‘frame’ the research question and the interpretation of results.

Table 4.1. Frameworks and references

| Suits research exploring:• Changing behaviours within health contexts to address patient and carer practices• Changing behaviours regarding environmental concerns• Barriers and enablers to behaviour/ practice/ implementation• Intervention planning and implementation• Post-evaluation• Promoting physical activity | This study examined how the COM-B model could be used to increase children’s hand-washing and improve disinfecting surfaces in seven countries. Each country had a different result based on capability, opportunity and/or motivation. This study examined the barriers and facilitators to talking about death and dying among the general population in Northern Ireland. The findings were mapped across the COM-B behaviour change model and the theoretical domains framework. This study explored women’s understanding of health and health behaviours and the supports that were important to promote behavioural change in the preconception period. Coding took place and a deductive process identified themes mapped to the COM-B framework. Identified perceived barriers and enablers of the implementation of a falls-prevention program to inform the implementation in a randomised controlled trial. Strategies to optimise the successful implementation of the program were also sought. Results were mapped against the COM-B framework. | ||

| Great for:• Evaluation• Intervention and implementation planning | Explored participants’ experiences with the program (ceasing smoking) to inform future implementation efforts of combined smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence interventions, guided by the CFIR. Key findings from the interviews are presented in relation to overarching CFIR domains. This mixed-methods study drew upon the CFIR combined with the concept of ‘intervention fidelity’ to evaluate the quality of the interprofessional counselling sessions, to explore the perspective of, directly and indirectly, involved healthcare staff, as well as to analyse the perceptions and experiences of the patients. This is a protocol for a scoping study to identify the topics in need of study and areas for future research on barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of workplace health-promoting interventions. Data analysis was aligned to the CFIR. This study examined the utility of the CFIR in identifying and comparing barriers and facilitators influencing the implementation of participatory research trials, by employing an adaptation of the CFIR to assess the implementation of a multi-component, urban public school-based participatory health intervention. Adapted CFIR constructs guided the largely deductive approach to thematic data analysis. | ||

| Good for:• Pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation studies• Feasibility studies• Intervention development | This study aimed to develop and assess the psychometric properties of a measurement scale for acceptance of a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention, based on the TFA; and to determine the acceptability of the intervention among participants living with diabetes or having a high risk of diabetes in socio-economically disadvantaged areas in Stockholm. A questionnaire using TFA was employed. This paper reported patients’ perceived acceptability of the use of PINCER in primary care and proposes suggestions on how delivery of PINCER-related care could be delivered in a way that is acceptable and not unnecessarily burdensome.This study describes the nationwide implementation of a program targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour in vocational schools (Lets’s Move It; LMI). Results showed high levels of acceptability and reach of training. This study drew on established models such TFA to assess the acceptability of SmartNet in Ugandan households. Results showed the monitor needs to continue to be optimised to make it more acceptable to users and to accurately reflect standard insecticide-treated nets use to improve understanding of prevention behaviours in malaria-endemic settings. | ||

| Good for:• Implementation• Evaluation | This pre-implementation evaluation of an integrated, shared decision-making personal health record system (e-PHR) was underpinned by NPT. The theory provides a framework to analyse cognitive and behavioural mechanisms known to influence implementation success. It was extremely valuable for informing the future implementation of e-PHR, including perceived benefits and barriers. This study assessed the impact of an intervention combining health literacy colorectal cancer-screening (CRC) training for GPs, using a pictorial brochure and video targeting eligible patients, to increase screening and other secondary outcomes, after 1 year, in several underserved geographic areas in France. They propose to evaluate health literacy among underserved populations to address health inequalities and improve CRC screening uptake and other outcomes. This study aimed to ascertain acceptability among pregnant smokers receiving the intervention. Interview schedules were informed by NPT and theoretical domains framework; interviews were analysed thematically, using the framework method and NPT. Findings are grouped according to the four NPT concepts. The study sought to understand how the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals compares across various models of primary care delivery in Ontario, Canada. Using the NPT framework to guide analysis, key themes emerged about the successful implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals. | ||

| Good for:• Patient experiences• Evaluation of health services• Evaluation | The study used the candidacy framework to explore how the doctor–patient relationship can influence perceived eligibility to visit their GP among people experiencing cancer alarm symptoms. A valuable theoretical framework for understanding the interactional factors of the doctor–patient relationship which influence perceived eligibility to seek help for possible cancer alarm symptoms.The study aimed to understand ways in which a mHealth intervention could be developed to overcome barriers to existing HIV testing and care services and promote HIV self-testing and linkage to prevention and care in a poor, HIV hyperendemic community in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Themes were identified from the interview transcripts, manually coded, and thematically analysed informed by the candidacy framework.This study explored the perceived problems of non-engagement that outreach aims to address and specific mechanisms of outreach hypothesised to tackle these. Analysis was thematically guided by the concept of 'candidacy', which theorises the dynamic process through which services and individuals negotiate appropriate service use.This was a theoretically informed examination of experiences of access to secondary mental health services during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Findings affirm the value of the construct of candidacy for explaining access to mental health care, but also enable deepened understanding of the specific features of candidacy. | ||

| Good for:• Examining how social injustice affects health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from a non-medical model• Examining how inequalities in illness and mortality rates result from personal context within communities characterised by social, economic and political inequality, factors | Culture had a strong presence in program delivery and building social cohesion, and social capital emerged as themes. As a primary health care provider, the ACCHO sector addresses the social determinants of health and health inequity experienced by Indigenous communities. The community-controlled service increased their breadth of strategies used to address primary health care indicates the need for greater understanding of the benefits of this model, as well as advocacy to safeguard it from measures that may undermine its equity performance.The primary health care delivered by ACCHOs is culturally appropriate because they are incorporated Aboriginal organisations, initiated by local Aboriginal communities and based in local Aboriginal communities, governed by Aboriginal bodies elected by the local Aboriginal community, delivering a holistic and culturally appropriate health service to the community that controls it. After investigation, the authors state that failure to recognise the intersection of culture with other structural and societal factors creates and compounds poor health outcomes, thereby multiplying financial, intellectual and humanitarian cost. They review health and health practices as they relate to culture. | ||

| Good for:• Understanding the non-medical factors that influence health and social outcomes | The study identifies and describes the social determinants of health.This study examines a socio-ecological approach to healthy eating and active living, a model of health that recognises the interaction between individuals and their greater environment and its impact on health.The study considers the healthcare screening and referral of families to resources that are critical roles for pediatric healthcare practices to consider as part of addressing social determinants of health.This study examines how (apart from age) social and economic factors contribute to disability differences between older men and women. | ||

| Good for: • Examining all the factors that contribute to health, such as social, cultural, political and environmental factors | Participants provided narratives of the pictures, using pre-identified themes and the different levels of the social-ecological model.The study tested a socioecological model of the determinants of health literacy with a special focus on geographical differences in Europe.This study investigated the interaction of family support, transport cost (ex-post) and disabilities on health service-seeking behaviour among older people, from the perspective of the social ecological model. The study examined the factors that contributed to low birth weight in babies, including age, gestational age, birth spacing, age at marriage, history of having a low birth weight infant, miscarriage and stillbirth, mean weight before pregnancy, body mass index, hemoglobin and hematocrit, educational level, family size, number of pregnancies, husband’s support during pregnancy and husband’s occupation. | ||

| Good for: • Using a new way of thinking to understand the whole rather than individual parts | The study outlines a systems theory of mental health care and promotion that is specific to needs of the recreational sport system, so that context-specific, effective policies, interventions and models of care can be articulated and tested.This study uses a systems-thinking approach to consider the person–environment transaction and to focus on the underlying processes and patterns of human behaviour of flight attendants.The study examines the family as a system and proposes that family systems theory is a formal theory that can be used to guide family practice and research.The authors examine the meta-theoretical, theoretical and methodological foundations of the literature base of hope. They examine the intersection of positive psychology with systems thinking. | ||

| Good for:• Understanding the many factors that affect health, including biological, psychological and social factors | The biopsychosocial model was used to guide the entire research study: background, question, tools and analysis.The biopsychosocial model was used to guide the researchers’ understanding of ‘health’ and the many factors that affect it, including the wider determinants of health in the discussion.The biopsychosocial model is not specifically mentioned; however, factors such as depression, age, social support, income, co-morbidities including diabetes and hypertension, and sex were measured and analysed.The study uses the Survey of Unmet Needs for data collection, which determines needs across impairment, activities of daily living, occupational activities, psychological needs, and community access. Data was analysed across the full spectrum of needs. |

As discussed in Chapter 3, qualitative research is not an absolute science. While not all research may need a framework or theory (particularly descriptive studies, outlined in Chapter 5), the use of a framework or theory can help to position the research questions, research processes and conclusions and implications within the relevant research paradigm. Theories and frameworks also help to bring to focus areas of the research problem that may not have been considered.

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med . 2020;95(7):989-994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci . 2011;6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Center for Clinical Management Research. 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://cfirguide.org/

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res . 2017;17:88. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med . 2010;8:63. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-63

- Tookey S, Renzi C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Whitaker KL. Using the candidacy framework to understand how doctor-patient interactions influence perceived eligibility to seek help for cancer alarm symptoms: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res . 2018;18(1):937. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3730-5

- Lyon P. Aboriginal Health in Aboriginal Hands: Community-Controlled Comprehensive Primary Health Care @ Central Australian Aboriginal Congress; 2016. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cphc-congress-final-report.pdf

- Solar O., Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); 2010. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852

- Yuill C, Crinson I, Duncan E. Key Concepts in Health Studies . SAGE Publications; 2010.

- Germov J. Imagining health problems as social issues. In: Germov J, ed. Second Opinion: An Introduction to Health Sociology . Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Laszlo A, Krippner S. Systems theories: their origins, foundations, and development. In: Jordan JS, ed. Advances in Psychology . Science Direct; 1998:47-74.

- Engel GL. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics . 1997;38(6):521-528. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71396-3

- Schmidtke KA, Drinkwater KG. A cross-sectional survey assessing the influence of theoretically informed behavioural factors on hand hygiene across seven countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1432. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11491-4

- Graham-Wisener L, Nelson A, Byrne A, et al. Understanding public attitudes to death talk and advance care planning in Northern Ireland using health behaviour change theory: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:906. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13319-1

- Walker R, Quong S, Olivier P, Wu L, Xie J, Boyle J. Empowerment for behaviour change through social connections: a qualitative exploration of women’s preferences in preconception health promotion in the state of Victoria, Australia. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1642. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14028-5

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Morello RT, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE . 2017;12(2):e0171932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

- Pratt R, Xiong S, Kmiecik A, et al. The implementation of a smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence intervention for people experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1260. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13563-5

- Bossert J, Mahler C, Boltenhagen U, et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a counselling intervention designed to educate cancer patients on complementary and integrative health care and promote interprofessional collaboration in this area (the CCC-Integrativ study). PLOS ONE . 2022;17(5):e0268091. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268091

- Lwin KS, Bhandari AKC, Nguyen PT, et al. Factors influencing implementation of health-promoting interventions at workplaces: protocol for a scoping review. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275887

- Wilhelm AK, Schwedhelm M, Bigelow M, et al. Evaluation of a school-based participatory intervention to improve school environments using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1615. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11644-5

- Timm L, Annerstedt KS, Ahlgren JÁ, et al. Application of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability to assess a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275576. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275576

- Laing L, Salema N-E, Jeffries M, et al. Understanding factors that could influence patient acceptability of the use of the PINCER intervention in primary care: a qualitative exploration using the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275633

- Renko E, Knittle K, Palsola M, Lintunen T, Hankonen N. Acceptability, reach and implementation of a training to enhance teachers’ skills in physical activity promotion. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1568. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09653-x

- Alexander SM, Agaba A, Campbell JI, et al. A qualitative study of the acceptability of remote electronic bednet use monitoring in Uganda. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1010. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13393

- May C, Rapley T, Mair FS, et al. Normalization Process Theory On-line Users’ Manual, Toolkit and NoMAD instrument. 2015. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://normalization-process-theory.northumbria.ac.uk/

- Davis S. Ready for prime time? Using Normalization Process Theory to evaluate implementation success of personal health records designed for decision making. Front Digit Health . 2020;2:575951. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2020.575951

- Durand M-A, Lamouroux A, Redmond NM, et al. Impact of a health literacy intervention combining general practitioner training and a consumer facing intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in underserved areas: protocol for a multicentric cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1684. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11565

- Jones SE, Hamilton S, Bell R, Araújo-Soares V, White M. Acceptability of a cessation intervention for pregnant smokers: a qualitative study guided by Normalization Process Theory. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1512. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09608-2

- Ziegler E, Valaitis R, Yost J, Carter N, Risdon C. “Primary care is primary care”: use of Normalization Process Theory to explore the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals in Ontario. PLOS ONE . 2019;14(4):e0215873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215873

- Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell C. Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm . 2013;47(7):806-825. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

- Adeagbo O, Herbst C, Blandford A, et al. Exploring people’s candidacy for mobile health–supported HIV testing and care services in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21(11):e15681. doi:10.2196/15681

- Mackenzie M, Turner F, Platt S, et al. What is the ‘problem’ that outreach work seeks to address and how might it be tackled? Seeking theory in a primary health prevention programme. BMC Health Serv Res . 2011;11:350. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-350

- Liberati E, Richards N, Parker J, et al. Qualitative study of candidacy and access to secondary mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114711. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114711

- Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1859. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09943-4

- Freeman T, Baum F, Lawless A, et al. Revisiting the ability of Australian primary healthcare services to respond to health inequity. Aust J Prim Health . 2016;22(4):332-338. doi:10.1071/PY14180

- Couzos S. Towards a National Primary Health Care Strategy: Fulfilling Aboriginal Peoples Aspirations to Close the Gap . National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. 2009. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/35080/

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, et al. Culture and health. Lancet . 2014;384(9954):1607-1639. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61603-2

- WHO. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief . 2021. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387

- WHO. Social Determinants of Health . 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- McCrae JS, Robinson JAL, Spain AK, Byers K, Axelrod JL. The Mitigating Toxic Stress study design: approaches to developmental evaluation of pediatric health care innovations addressing social determinants of health and toxic stress. BMC Health Serv Res . 2021;21:71. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06057-4

- Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams J, Jann B, et al. Social determinants of sex differences in disability among older adults: a multi-country decomposition analysis using the World Health Survey. Int J Equity Health . 2012;11:52. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-52

- Kabore A, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Awua J, et al. Social ecological factors affecting substance abuse in Ghana (West Africa) using photovoice. Pan Afr Med J . 2019;34:214. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.34.214.12851

- Bíró É, Vincze F, Mátyás G, Kósa K. Recursive path model for health literacy: the effect of social support and geographical residence. Front Public Health . 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.724995

- Yuan B, Zhang T, Li J. Family support and transport cost: understanding health service among older people from the perspective of social-ecological model. Arch Public Health . 2022;80:173. doi:10.1186/s13690-022-00923-1

- Mahmoodi Z, Karimlou M, Sajjadi H, Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dolatian M. A communicative model of mothers’ lifestyles during pregnancy with low birth weight based on social determinants of health: a path analysis. Oman Med J . 2017 ;32(4):306-314. doi:10.5001/omj.2017.59

- Vella SA, Schweickle MJ, Sutcliffe J, Liddelow C, Swann C. A systems theory of mental health in recreational sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2022;19(21):14244. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114244

- Henning S. The wellness of airline cabin attendants: A systems theory perspective. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure . 2015;4(1):1-11. Accessed February 15, 2023. http://www.ajhtl.com/archive.html

- Sutphin ST, McDonough S, Schrenkel A. The role of formal theory in social work research: formalizing family systems theory. Adv Soc Work . 2013;14(2):501-517. doi:10.18060/7942

- Colla R, Williams P, Oades LG, Camacho-Morles J. “A new hope” for positive psychology: a dynamic systems reconceptualization of hope theory. Front Psychol . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

- Wade DT, HalliganPW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabi l. 2017;31(8):995–1004. doi:10.1177/0269215517709890

- Ip L, Smith A, Papachristou I, Tolani E. 3 Dimensions for Long Term Conditions – creating a sustainable bio-psycho-social approach to healthcare. J Integr Care . 2019;19(4):5. doi:10.5334/ijic.s3005

- FrameWorks Institute. A Matter of Life and Death: Explaining the Wider Determinants of Health in the UK . FrameWorks Institute; 2022. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FWI-30-uk-health-brief-v3a.pdf

- Zemed A, Nigussie Chala K, Azeze Eriku G, Yalew Aschalew A. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with stroke at tertiary level hospitals in Ethiopia. PLOS ONE . 2021;16(3):e0248481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248481

- Finch E, Foster M, Cruwys T, et al. Meeting unmet needs following minor stroke: the SUN randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Health Serv Res . 2019;19:894. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4746-1

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Tess Tsindos is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Patient Cent Res Rev

- v.11(1); Spring 2024

- PMC11000705

Research Frameworks: Critical Components for Reporting Qualitative Health Care Research

Qualitative health care research can provide insights into health care practices that quantitative studies cannot. However, the potential of qualitative research to improve health care is undermined by reporting that does not explain or justify the research questions and design. The vital role of research frameworks for designing and conducting quality research is widely accepted, but despite many articles and books on the topic, confusion persists about what constitutes an adequate underpinning framework, what to call it, and how to use one. This editorial clarifies some of the terminology and reinforces why research frameworks are essential for good-quality reporting of all research, especially qualitative research.

Qualitative research provides valuable insights into health care interactions and decision-making processes – for example, why and how a clinician may ignore prevailing evidence and continue making clinical decisions the way they always have. 1 The perception of qualitative health care research has improved since a 2016 article by Greenhalgh et al. highlighted the higher contributions and citation rates of qualitative research than those of contemporaneous quantitative research. 2 The Greenhalgh et al. article was subsequently supported by an open letter from 76 senior academics spanning 11 countries to the editors of the British Medical Journal . 3 Despite greater recognition and acceptance, qualitative research continues to have an “uneasy relationship with theory,” 4 which contributes to poor reporting.

As an editor for the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews , as well as Human Resources for Health , I have seen several exemplary qualitative articles with clear and coherent reporting. On the other hand, I have often been concerned by a lack of rigorous reporting, which may reflect and reinforce the outdated perception of qualitative research as the “soft option.” 5 Qualitative research is more than conducting a few semi-structured interviews, transcribing the audio recordings verbatim, coding the transcripts, and developing and reporting themes, including a few quotes. Qualitative research that benefits health care is time-consuming and labor-intensive, requires robust design, and is rooted in theory, along with comprehensive reporting. 6

What Is “Theory”?

So fundamental is theory to qualitative research that I initially toyed with titling this editorial, “ Theory: the missing link in qualitative health care research articles ,” before deeming that focus too broad. As far back as 1967, Merton 6 warned that “the word theory threatens to become meaningless.” While it cannot be overstated that “atheoretical” studies lack the underlying logic that justifies researchers’ design choices, the word theory is so overused that it is difficult to understand what constitutes an adequate theoretical foundation and what to call it.

Theory, as used in the term theoretical foundation , refers to the existing body of knowledge. 7 , 8 The existing body of knowledge consists of more than formal theories , with their explanatory and predictive characteristics, so theory implies more than just theories . Box 1 9 – 12 defines the “building blocks of formal theories.” 9 Theorizing or theory-building starts with concepts at the most concrete, experiential level, becoming progressively more abstract until a higher-level theory is developed that explains the relationships between the building blocks. 9 Grand theories are broad, representing the most abstract level of theorizing. Middle-range and explanatory theories are progressively less abstract, more specific to particular phenomena or cases (middle-range) or variables (explanatory), and testable.

The Building Blocks of Formal Theories 9

| words we assign to mental representations of events or phenomena , | |

| higher-order clusters of concepts | |

| expressions of relationships among several constructs | |

| “sets of interrelated constructs, definitions, and propositions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables and phenomena” general sets “of principles that are independent of the specific case, situation, phenomenon or observation to be explained” |

The Importance of Research Frameworks

Researchers may draw on several elements to frame their research. Generally, a framework is regarded as “a set of ideas that you use when you are forming your decisions and judgements” 13 or “a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that is used to plan or decide something.” 14 Research frameworks may consist of a single formal theory or part thereof, any combination of several theories or relevant constructs from different theories, models (as simplified representations of formal theories), concepts from the literature and researchers’ experiences.