Generating Ideas for Your Paper

- Introduction

Good writing requires good ideas—intriguing concepts and analysis that are clearly and compellingly arranged. But good ideas don’t just appear like magic. All writers struggle with figuring out what they are going to say. And while there is no set formula for generating ideas for your writing, there is a wide range of established techniques that can help you get started.

This page contains information about those techniques. Here you’ll find details about specific ways to develop thoughts and foster inspiration. While many writers employ one or two of these strategies at the beginning of their writing processes in order to come up with their overall topic or argument, these techniques can also be used any time you’re trying to figure out how to effectively achieve any of your writing goals or even just when you’re not sure what to say next.

What is Invention?

Where do ideas come from? This is a high-level question worthy of a fascinating TED Talk or a Smithsonian article , but it also represents one of the primary challenges of writing. How do we figure out WHAT to write?

Even hundreds of years ago, people knew that a text begins with an idea and that locating this idea and determining how to develop it requires work. According to classical understandings of rhetoric, the first step of building an argument is invention. As Roman thinker Cicero argued, people developing arguments “ought first to find out what [they] should say” ( On Oratory and Orators 3.31). Two hundred years before Cicero, the Greek philosopher Aristotle detailed a list of more than two dozen ideas a rhetor might consider when figuring out what to say about a given topic ( On Rhetoric , 2.23). For example, Aristotle suggested that a good place to start is to define your key concepts, to think about how your topic compares to other topics, or to identify its causes and effects. (For ideas about using Aristotle’s advice to generate ideas for your own papers, check out this recommended technique .)

More recently, composition scholar Joseph Harris has identified three values important for writers just starting a project. Writers at early stages in their writing process can benefit from being: Receptive to unexpected connections You never know when something you read or need to write will remind you of that movie you watched last weekend or that anthropology theory you just heard a lecture about or that conversation you had with a member of your lab about some unexpected data you’ve encountered. Sometimes these connections will jump out at you in the moment or you’ll suddenly remember them while you’re vacuuming the living room. Harris validates the importance of “seizing hold of those ideas that do somehow come to you” (102). While you can’t count on these kinds of serendipities, be open to them when they occur. Be ready to stop and jot them down! Patient Harris supports the value of patience and “the usefulness of boredom, of letting ideas percolate” (102). It can take time and long consideration to think of something new. When possible, give yourself plenty of time so that your development of ideas is not stifled by an immediate due date. Compelled by the unknown According to Harris, “a writer often needs to start not from a moment of inspiration ( eureka! ) but from the need to work through a conceptual problem or roadblock. Indeed, I’d suggest that most academic writing begins with such questions rather than insights, with difficulties in understanding rather than moments of mastery” (102). Sometimes a very good place to begin is with what you don’t know, with the questions and curiosities that you genuinely want resolved.

In what follows, we describe ten techniques that you can select from and experiment with to help guide your invention processes. Depending on your writing preferences, context, and audience, you might find some more productive than others. Also, it might be useful to utilize various techniques for different purposes. For example, brainstorming might be great for generating a variety of possible ideas, but looped freewriting might help you develop those ideas. Think of this list as a collection of recommended possibilities to implement at your discretion. However, we think the first technique described below—“Analyzing the Assignment or Task”—is a great starting point for all writers.

Any of these strategies can be useful for generating ideas in connection to any writing assignment. Even if the paper you’re writing has a set structure (e.g., scientific reports’ IMRAD format or some philosophy assignments’ prescribed argumentative sequence), you still have to invent and organize concepts and supporting evidence within each section. Additionally, these techniques can be used at any stage in your writing process. Your ideas change and develop as you write, and sometimes when you’re in the middle of a draft or when you’re embarking on a major revision, you find yourself rethinking key elements of your paper. At these moments, it might be useful to turn to some of these invention techniques as a way to slow down and capture the ephemeral thoughts and possibilities swirling around your writing tasks. These practices can help guide you to new ideas, questions, and connections. No matter what you’re writing or where you are in the process, we encourage you to experiment with invention strategies you may not have tried before. Mix and match. Be as creative and adventurous with how you generate ideas just as you are creative and adventurous with what ideas you generate.

Some Invention Techniques

Analyzing the assignment or task.

What do I do? If you are writing a paper in response to a course instructor’s assignment, be sure to read the prompt carefully while paying particular attention to all of its requirements and expectations. It could be that the assignment is built around a primary question; if so, structure your initial thoughts around possible answers to that question. If it isn’t, use your close consideration of this assignment to recast the prompt as a question.

The following list of questions are ones that you can ask of the assignment in order to understand its focus and purpose as well as to begin developing ideas for how to effectively respond to its intensions. You may want to underline key terms and record your answers to these questions:

- When is this due?

- How long is supposed to be?

- Is the topic given to me?

- If I get to choose my topic, are there any stipulations about the kind of topic and I can choose?

- What am I expected to do with this topic? Analyze it? Report about it? Make an argument about it? Compare it to something else?

- Who is my audience and what does this audience know, believe, and value about my topic?

- What is the genre of this writing (i.e., a lab report, a case study, a research paper, a reflection, a scholarship essay, an analysis of a work of literature or a painting, a summary and analysis of a reading, a literature review, etc.), and what does writing in this genre usually look like, consist of, or do?

Why is this technique useful? Reading over the assignment prompt may sound like an obvious starting point, but it is very important that your invention strategies are informed by the expectations your readers have about your writing. For example, you might brainstorm a fascinating thesis about how Jules Verne served as a conceptual progenitor of the nuclear age, but if your assignment is asking you to describe the differences between fission and fusion and provide examples, this great idea won’t be very helpful. Before you let your ideas run free, make sure you fully understand the boundaries and possibilities provided by the assignment prompt.

Additionally, some assignments begin to do the work of invention for you. Instructors sometimes identify specifically what they want you to write about. Sometimes they invite you to choose from several guiding questions or a position to support or refute. Sometimes the genre of the text can help you identify how this kind of assignment should begin or the order your ideas should follow. Knowing this can help you develop your content. Before you start conjuring ideas from scratch, make sure you glean everything you can from the prompt.

Finally, just sitting with the assignment and thinking through its guidelines can sometimes provide inspiration for how to respond to its questions or approach its challenges.

Reading Again

What do I do? When your writing task is centered around analyzing a primary source, information you collected, or another kind of text, start by rereading it. Perhaps you are supposed to develop an argument about an interview you conducted, an article or short story you read, an archived letter you located, or even a painting you viewed or a particular set of data. In order to develop ideas about how to approach this object of analysis, read and analyze this text again. Read it closely. Be prepared to take notes about its interesting features or the questions this second encounter raises. You can find more information about rereading literature to write about it here and specific tips about reading poetry here .

Why is this technique useful? When you first read a text, you gain a general overview. You find out what is happening, why it’s happening, and what the argument is. But when you reread that same text, your attention is freed to attend to the details. Since you know where the text is heading, you can be alert to patterns and anomalies. You can see the broader significance of smaller elements. You can use your developing familiarity with this text to your advantage as you become something of a minor expert whose understanding of this object deepens with each re-read. This expertise and insight can help lead you towards original ideas about this text.

Brainstorming/Listing

What do I do? First, consider your prompt, assignment, or writing concern (see “Analyzing the Assignment or Task”). Then start jotting down or listing all possible ideas for what you might write in response. The goal is to get as many options listed as possible. You may wish to develop sub-lists or put some of your ideas into different categories, but don’t censor or edit yourself. And don’t worry about writing in full sentences. Write down absolutely everything that comes to mind—even preposterous solutions or unrealistic notions. If you’re working on a collaborative project, this might be a process that you conduct with others, something that involves everyone meeting at the same time to call out ideas and write them down so everyone can see them. You might give yourself a set amount of time to develop your lists, or you might stretch out the process across a couple of days so that you can add new ideas to your lists whenever they occur to you.

Why is this technique useful? The idea behind this strategy is to open yourself up to all possibilities because sometimes even the most seemingly off-the-wall idea has, at its core, some productive potential. And sometimes getting to that potential first involves recognizing the outlandish. There is time later in your writing process to think critically about the viability of your options as well as which possibilities effectively respond to the prompt and connect to your audience. But brainstorming or listing sets those considerations aside for a moment and invites you to open your imagination up to all options.

Freewriting

What do I do? Sit down and write about your topic without stopping for a set amount of time (i.e., 5-10 minutes). The goal is to generate a continuous, forward-moving flow of text, to track down all of your thoughts about this topic, as if you are thinking on the page. Even if all you can think is, “I don’t know what to write,” or, “Is this important?” write that down and keep on writing. Repeat the same word or phrase over again if you need to. If you’re writing about an unfamiliar topic, maybe start by writing down everything you know about it and then begin listing questions you have. Write in full sentences or in phrases, whatever helps keep your thoughts flowing. Through this process, don’t worry about errors of any kind or gaps in logic. Don’t stop to reread or revise what you wrote. Let your words follow your thought process wherever it takes you.

Why is this technique useful? The purpose of this technique is to open yourself up to the possibilities of your ideas while establishing a record of what those ideas are. Through the unhindered nature of this open process, you are freed to stumble into interesting options you might not have previously considered.

Invisible Writing

What do I do? In this variation of freewriting, you dim your computer screen so that you can’t see what you’ve written as you type out your thoughts.

Why is this technique useful? This is a particularly useful technique if while you are freewriting you just can’t keep yourself from reviewing, adjusting, or correcting your writing. This technique removes that temptation to revise by eliminating the visual element. By temporarily limiting your ability to see what you’ve written, this forward-focused method can help you keep pursuing thoughts wherever they might go.

Looped Freewriting

What do I do? This is another variation of freewriting. After an initial round of freewriting or invisible writing, go back through what you’ve written and locate one idea, phrase, or sentence that you think is really compelling. Make that the starting point for another round of timed freewriting and see where an uninterrupted stretch of writing starting from that point takes you. After this second round of freewriting, identify a particular part of this new text that stands out to you and make that the opening line for your third round of freewriting. Keep repeating this process as many times as you find productive.

Why is this technique useful? Sometimes this technique is called “mining” because through it writers are able to drill into the productive bedrock of ideas as well as unearth and discover latent possibilities. By identifying and expanding on concepts that you find particularly intriguing, this technique lets you focus your attention on what feels most generative within your freewritten text, allowing you to first narrow in and then elaborate upon those ideas.

Talking with Someone

What do I do? Find a generous and welcoming listener and talk through what you need to write and how you might go about writing it. Start by reading your assignment prompt aloud or just informally explaining what you are thinking about saying or arguing in your paper. Then be open to your listener’s reactions, curiosities, suggestions, and questions. Invite your listener to repeat in his or her own words what you’ve been saying so that you can hear how someone else is understanding your ideas. While a friend or classmate might be able to serve in this role, writing center tutors are also excellent interlocutors. If you are a currently enrolled UW-Madison student, you are welcome to make an appointment at our main writing center, stop by one of our satellite locations , or even set up a Virtual Meeting to talk with a tutor about your assignment, ideas, and possible options for further exploration.

Why is this technique useful? Sometimes it’s just useful to hear yourself talk through your ideas. Other times you can gain new insight by listening to someone else’s understanding of or interest in your assignment or topic. A genuinely curious listener can motivate you to think more deeply and to write more effectively.

Reading More

Sometimes course instructors specifically ask that you do your analysis on your own without consulting outside sources. When that is the case, skip this technique and consider implementing one of the others instead.

What do I do? Who else has written about your topic, run the kind of experiments you’ve developed, or made an argument like the one you’re interested in? What did they say about this issue? Do some internet searches for well-cited articles on this concept. Locate a book in the library stacks about this topic and then look at the books that are shelved nearby. Read where your interests lead you. Take notes about things other authors say that you find intriguing, that you have questions about, or that you disagree with. You might be able to use any of these responses to guide your developing paper. (Make sure you also record bibliographic information for any texts you want to incorporate in your paper so that you can correctly cite those authors.)

Why is this technique useful? Exploring what others have written about your topic can be a great way to help you understand this issue more fully. Through reading you can locate support for your ideas and discover arguments you want to refute. Reading about your topic can also be a way of figuring out what motivates you about this issue. Which texts do you want to read more of? Why? Capitalize on and expand upon these interests.

Visualizing Ideas

Mindmapping, clustering, or webbing.

What do I do? This technique is a form of brainstorming or listing that lets you visualize how your ideas function and relate. To make this work, you might want to locate a large space you can write on (like a whiteboard) or download software that lets you easily manipulate and group text, images, and shapes (like Coggle , FreeMind , or MindMapple ). Write down a central idea then identify associated concepts, features, or questions around that idea. If some of those thoughts need expanding, continue this map, cluster, or web in whatever direction is productive. Make lines attaching various ideas. Add and rearrange individual elements or whole subsets as necessary. Use different shapes, sizes, or colors to indicate commonalities, sequences, or relative importance.

Why is this technique useful? This technique allows you to generate ideas while thinking visually about how they function together. As you follow lines of thought, you can see which ideas can be connected, where certain pathways lead, and what the scope of your project might look like. Additionally, by drawing out a map of you may be able to see what elements of your possible paper are underdeveloped and may benefit from more focused brainstorming.

The following sample mindmap illustrates how this invention technique might be used to generate ideas for an environmental science paper about Lake Mendota, the Wisconsin lake just north of UW-Madison. The different branches and connections show how your mind might travel from one idea to the next. It’s important to note, that not all of these ideas would appear in the final draft of this eventual paper. No one is likely to write a paper about all the different nodes and possibilities represented in a mindmap. The best papers focus on a tightly defined question. But this does provide many potential places to begin and refine a paper on this topic. This mindmap was created using shapes and formatting options available through PowerPoint.

Notecarding

What do I do? This technique can be especially useful after you’ve identified a range of possibilities but aren’t sure how they might work together. On individual index cards, post-its, or scraps of paper, write out the ideas, questions, examples, and/or sources you’re interested in utilizing. Find somewhere that you can spread these out and begin organizing them in whatever way might make sense. Maybe group some of them together by subtopic or put them in a sequential order. Set some across from each other as conflicting opposites. Make the easiest organization decisions first so that the more difficult cards can be placed within an established framework. Take a picture or otherwise capture the resulting schemata. Of course, you can also do this same kind of work on a computer through software like Prezi or even on a PowerPoint slide.

Why is this technique useful? This technique furthers the mindmapping/clustering/webbing practice of grouping and visualizing your thoughts. Once ideas have been generated, notecarding invites you to think and rethink about how these ideas relate. This invention strategy allows you to see the big picture of your writing. It also invites you to consider how the details of sections and subsections might connect to each other and the surrounding ideas while giving you a sense of possible sequencing options.

The following example shows what notecarding might look like for a paper being written on the Clean Lakes Alliance—a not-for-profit organization that promotes the improvement of water quality in the bodies of water around Madison, Wisconsin. Key topics, subtopics, and possible articles were brainstormed and written on pieces of paper. These elements were then arranged to identify possible relationships and general organizational structures.

What do I do? Take the ideas, possibilities, sources, and/or examples you’ve generated and write them out in the order of what you might address first, second, third, etc. Use subpoints to subordinate certain ideas under main points. Maybe you want to identify details about what examples or supporting evidence you might use. Maybe you just want to keep your outline elements general. Do whatever is most useful to help you think through the sequence of your ideas. Remember that outlines can and should be revised as you continue to develop and refine your paper’s argument.

Why is this technique useful? This practice functions as a more linear form of notecarding. Additionally, outlines emphasize the sequence and hierarchy of ideas—your main points and subpoints. If you have settled on several key ideas, outlining can help you consider how to best guide your readers through these ideas and their supporting evidence. What do your readers need to understand first? Where might certain examples fit most naturally? These are the kinds of questions that an outline can clarify.

Asking Questions

Topoi questions.

In the introduction, we referenced the list that Aristotle developed of the more than two dozen ideas a person making an argument might use to locate the persuasive possibilities of that argument. Aristotle called these locations for argumentative potential “topoi.” Hundreds of years later, Cicero provided additional advice about the kinds of questions that provide useful fodder for developing arguments. The following list of questions is based on the topoi categories that Aristotle and Cicero recommended.

What do I do? Ask yourself any of these questions regarding your topic and write out your answers as a way of identifying and considering possible venues for exploration. Questions of definition: What is ____? How do we understand what ____ is? What is ____ comprised of?

Questions of comparison: What are other things that ____ is like? What are things that are nothing like ____?

Questions of relationship: What causes ____? What effects does ____ have? What are the consequences of ____?

Questions of circumstances: What has happened with ____ in the past? What has not happened with ____ in the past? What might possibly happen with ____ in the future? What is unlikely to happen with ____ in the future?

Questions of testimony: Who are the experts on ____ and what do they say about it? Who are people who have personal experience with ____ and what do they think about it?

If any of these questions initiates some interesting ideas, ask follow-up questions like, “Why is this the case? How do I know this? How might someone else answer this question differently?”

Why is this technique useful? The questions listed above draw from what both Aristotle and Cicero said about ways to go about inventing ideas. Questions such as these are tried-and-true methods that have guided speakers and writers towards possible arguments for thousands of years.

Journalistic Questions

What do I do? Identify your topic, then write out your answers in response to these questions: Who are the main stakeholders or figures connected to ____? What is ____? Where can we find ____? Where does this happen? When or under what circumstances does ____ occur? Why is ____ an issue? Why does it occur? Why is it important? How does ____ happen?

Why is this technique useful? This line of questioning is designed to make sure that you understand all the basic information about your topic. Traditionally, these are the kinds of questions that journalists ask about an issue that they are preparing to report about. These questions also directly relate to the Dramatistic Pentad developed by literary and rhetorical scholar Kenneth Burke. According to Burke, we can analyze anyone’s motives by considering these five parts of a situation: Act ( what ), Scene ( when and where ), Agent ( who ), Agency ( how ), and Purpose ( why ). By using these questions to identify the key elements of a topic, you may recognize what you find to be most compelling about it, what attracts your interest, and what you want to know more about.

Particle, Wave, Field Questions

One way to start generating ideas is to ask questions about what you’re studying from a variety of perspectives. This particular strategy uses particles, waves, and fields as metaphorical categories through which to develop various questions by thinking of your topic as a static entity (particle), a dynamic process (wave), and an interrelated system (field).

What do I do?

Ask yourself these questions about your issue or topic and write down your responses:

- In what ways can this issue be considered a particle, that is, a discrete thing or a static entity?

- How is this issue a wave, that is, a moving process?

- How is this issue a field, that is, a system of relationships related to other systems?

Why is this technique useful?

This way of looking at an issue was promoted by Young, Becker, and Pike in their classic text Rhetoric: Discovery and Change . The idea behind this heuristic is that anything can be considered a particle, a wave, and a field, and that by thinking of an issue in connection to each of these categories you’ll able to develop the kind of in-depth questions that experts ask about a topic. By identifying the way your topic is a thing in and of itself, an activity, and an interrelated network, you’ll be able to see what aspects of it are the most intriguing, uncertain, or conceptually rich.

The following example takes the previously considered topic—environmental concerns and Lake Mendota—and shows how this could be conceptualized as a particle, a wave, and a field as a way of generating possible writing ideas.

Particle: Consider Lake Mendota and its environmental concerns as they appear in a given moment. What are those concerns right now? What do they look like? Maybe it’s late spring and an unseasonably warm snap has caused a bunch of dead fish to wash up next to the Tenney Lock. Maybe it’s a summer weekend and no one can go swimming off the Terrace because phosphorous-boosted blue-green algae is too prevalent. Pick one, discrete environmental concern and describe it. Wave: Consider environmental concerns related to Lake Mendota as processes that have changed and will change over time. When were the invasive spiny water fleas first discovered in Lake Mendota? Where did they come from? What has been done to respond to the damage they have caused? What else could be proposed to resolve this problem. How is this (or any other environmental concern) a dynamic process? Field: Consider Lake Mendota’s environmental concerns as they relate to a range of disciplines, populations, and priorities. What recent limnology findings would be of interest to ice fishing anglers? How could the work being done on agricultural sustainability connect to the discoveries being made by chemists about the various compounds present in the water? What light could members of the Ho-Chunk nation shed on Lake Mendota’s significance? Think about how environmental and conservation concerns associated with this lake are interconnected across different community members and academic disciplines.

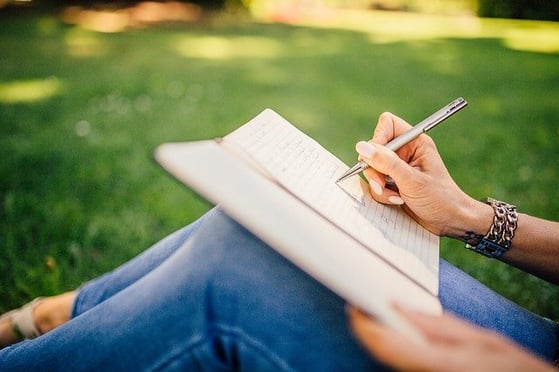

Moving Around

Get away from your desk and your computer screen and do whatever form of movement feels comfortable and natural for you. Get some fresh air, take a walk, go jogging, get on your bike, go for a swim, or do some yoga. There is no correct degree or intensity of movement in this process; just do what you can and what you’re most likely to enjoy. While you’re moving, you may want to zone out and give yourself a strategic break from your writing task. Or you might choose to mull your tentative ideas for your paper over in your mind. But whether you’re hoping to think of something other than your paper or you need to generate a specific idea or resolve a particular writing problem, be prepared to record quickly any ideas that come up. If bringing along paper or a small notebook and a pen is inconvenient, just texting yourself your new idea will do the trick. The objective with this technique is both to distance yourself from your writing concerns and to encourage your mind to build new connections through engaging in physical activity.

Numerous medical studies have found that aerobic exercise increases your body’s concentration of the proteins that help nerves grow in the parts of your brain where learning and higher thinking happens (Huang et al.). Similarly, from their review of the literature about how yoga benefits the brain, Desei et al. conclude that yoga boosts overall brain activity. Which is to say that moving physiologically helps you think.

Dr. Bonnie Smith Whitehouse, an associate professor of English at Belmont University and an alum of UW-Madison’s graduate program in Composition and Rhetoric Program and a former assistant director of Writing Across the Curriculum at UW-Madison, investigates the writerly benefits of walking. She provides a full treatment of how this particular form of movement can productively support writing in her book Afoot and Lighthearted: A Mindful Walking Log . In the following passage, she argues for a connection between creative processes and walking, but much of what she suggests is equally applicable to the beneficial value of other forms of movement.

A walk stimulates creativity after a ramble has concluded, when you find yourself back at your desk, before your easel, or in your studio. In 2014, Stanford University researchers Marily Opprezzo and Daniel L. Schwarz confirmed that walking increases creative ideation in real time (while the walker walkers) and shortly after (when the walker stops and sits down to create). Specifically, they found that walking led to an increase in “analogical creativity” or using analogies to develop creative relationships between things that may not immediately look connected. So when ancient Greek physician Hippocrates famously declared that walking is “the best medicine,” he seems to have had it right. When we walk, blood and oxygen circulate throughout the body’s organs and stimulate the brain. Walking’s magic is in fact threefold: it increases physical activity, boosts creativity, and brings you into the present moment.

Similarly, in her post about writing and jogging for the UW-Madison Writing Center’s blog, Literary Studies PhD student Jessie Gurd has explained:

What running allows me to do is clear my head and empty it of a grad student’s daily anxieties. Listening to music or cicadas or traffic, I can consider one thing at a time and turn it over in my mind. It’s a groove I hit after a couple of miles; I engage with the problem, question, or task I choose and roll with it until my run is over. In this physical-mental space, I sometimes feel like my own writing instructor as I tackle some stage of the writing process: brainstorming, outlining, drafting.

While Bonnie Smith Whitehouse walks as an important part of her writing process and Jessie Gurd runs to write, what intentional movement looks like for you can be adapted according to your interests, preferences, and abilities. Whether it’s strolling, jogging, doing yoga, or participating in some other form of movement, these physical activities allow you to take a purposeful break that can help you concentrate your mind and even generate new conceptual connections.

All aspects of writing require hard work. It takes work to develop organizational strategies, to sequence sentences, and to revise paragraphs. And it takes work to come up with the ideas that will fill these sentences and paragraphs in the first place. But if you feel burdened by the necessity to develop new concepts, the good news is that you’re not the first writer who’s had to begin responding to an assignment from scratch. You are backed by a vast history of other writers’ experiences, a history that has shaped a collective understanding of how to get started. So, use the experience of others to your advantage. Try a couple of these techniques and maybe even develop some other methods of your own and see what new ideas these old strategies can help you generate!

Works Cited

Aristotle. On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse . Edited and translated by George Kennedy, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives . University of California Press, 1969.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. On Oratory and Orators . Edited and translated by J.S. Watson, Southern Illinois University Press, 1986.

Desai, Radhika, et al. “Effects of Yoga on Brain Waves an Structural activation: A review.” Complementary Therapies in clinical Practice ,vol, 21, no, 2, 2015, pp. 112-118.

Gurd, Jessie. “Writing Offstage.” Another Word , The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 7 October 2013, https://writing.wisc.edu/blog/writing-offstage/ . Accessed 5 July 2018.

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts . Utah State University Press, 2006.

Huang, T. et al. “The Effects of Physical Activity and Exercise on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Healthy Humans: A Review.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports , vol. 24, no. 1, 2013. Wiley Online Library , https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12069 .

Oppezzo, Marily, and Daniel L. Schwartz. “Give Your Ideas Some Legs: The Positive Effect of Walking on Creative Thinking.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition , vol. 40, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1142-52.

Smith Whitehouse, Bonnie, email message to author, 19 June 2018.

Young, Richard E., Alton L. Becker, and Kenneth L. Pike. Rhetoric: Discovery and Change . Harcourt College Publishing, 1970.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

5 Ways to Generate Great Essay Ideas

Daniela McVicker

Writing an essay is a challenging undertaking. You have to research, take notes, write an outline, and then turn that outline into a rough draft. Finally, you have to repeatedly edit and refine your rough draft until it becomes a suitable final draft. It can take hours, even days, to complete an essay.

Of course, before any of this can happen, you need to come up with a great topic. It may seem like a simple task, but if you cannot think of an essay idea, you can’t even get off the starting blocks. So, what do you do when you are stuck and can’t think of anything to write about?

Here are 5 ways in which you can help yourself come up with a great essay idea.

1. Brainstorming

2. free writing, 3. look at your life story, 4. go back to your textbook, 5. if you are desperate, go with a generic essay topic.

Before you start a brainstorming session, remember that there is one rule. No idea is cast aside as being silly, too complex, not complex enough, too far off topic, etc. You can always pare down your list later on. It's better to jot down a few flops now, than it is to ignore an idea that might turn into something brilliant. A pen and paper may be all you need to get started, but a note-taking app like Evernote can help organize your ideas.

Brainstorming in a group is a bit different. Try Dragon Dictation , which records and transcribes your conversations as you bounce ideas off one another. Google Docs can save documents to the cloud so that everyone can access the list when it is time to make decisions. You will find that as you get into a brainstorming session, the ideas will come quickly.

Free writing is a stream-of-consciousness exercise where you simply write down whatever comes into your mind. We recommend making the process a little more disciplined. Rather than writing about anything, stick with a general subject area that is defined on the subject you are in studying in class.

As you start free writing, you may be surprised at the number of thoughts you have on the subject you are covering, and the amount of knowledge you have retained. Eventually, as you free write, you will see your writing become more and more focused. This is an excellent sign that you are narrowing in on the specific topic idea for your essay. Even better, as you free write, you may come up with a few things that you can paste almost directly into your essay.

What do you know that other people do not? What things do you understand that the average person does not understand? Do you have any relevant experience or special knowledge when it comes to the subject?

If you answered "yes" to any of these questions, you might be a step ahead of the game when it comes to figuring out the best essay topic for you. Something you know how to do or that you understand can be a great topic for a process essay. An experience you had can be fodder for a narrative essay. It gives you a unique point of view. Just don't allow yourself to show too much bias, or to ignore evidence in favor of your personal story. As a bonus, you will notice you will write much more quickly when you are relating a story from your life.

You have probably learned that the best way to study for tests and quizzes is to focus on the subheadings, bullet points, chapter questions, pictures, and graphs. If you are trying to come up with a good essay topic, you should also review these. They will remind you which elements are most important.

If you write your essay on something that is emphasized in your textbook, there is a pretty good chance you are on the right track. You will know that your topic is relevant, and you can impress your instructor by displaying your in-depth knowledge on that topic.

The truth is this: you may not come up with a brilliant essay idea each time you are given a writing assignment. However, that does not mean you cannot write an excellent paper. You can still write an essay that is well researched, thoughtful, and carefully written.

Plenty of essays are written by students who earn excellent grades, but are not very excited by the topic they have chosen. It’s better to write an essay on a less exciting topic than to turn it in late because you spent too much time searching for the “wow” factor.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Daniela McVicker is a young ambitious writer who believes that all her life is time for adventures, love and self-culture.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Last places remaining for June 30th, July 14th and July 28th courses . Enrol now and join students from 175 countries for the summer of a lifetime

- 4 Ways to Come Up With a Great Essay Idea

You should also read…

- 10 Study Fallacies and How Not to Fall for Them

- 10 Ways of Thinking That Will Boost Your Academic Performance

It starts when you first get a choice of which question you want to answer, which might even first happen in primary school. Part of the challenge is figuring out which question you’d do best at answering; you’re not just regurgitating information any more, but needing to think critically about your own knowledge and abilities. From there, the choices increase. You might be given a choice of three or more essay questions. Or you might get just the one question, but you can choose factors within it – you might be asked, for instance, the extent to which a character in Hamlet lives up to their own moral code – the question is set for you, but you get to choose which character you want to write about. The same might happen for a period in history or a monarch, or an analysis of a case study. And finally you’ll get to the point where you might have a topic list to choose from, but the essay title itself will be entirely up to you.

You may even be offered the chance to do this a little earlier, where you get given a list of essay titles but also told that you can come up with your own if you’d like. Few students bother, and it can be a high-risk strategy – you might come up with a title that is much harder to answer than the ones provided for you – but it can also be a route to crafting a title that is perfect for you. All of the stages in this process – picking a question, picking a focus and, finally, picking a title – can be daunting when you haven’t done them before. In this article, we look at how to come up with essay titles that work for you.

1. Answer the question you want answered

The best way to come up with an idea for an essay is to consider what the question is that you would like to see answered. This can seem like quite a scary way of going about choosing a question, because it implies that the question has gone unanswered – that you’re suddenly going to come up with such an insightful question that no previous scholar in the field has contemplated. If that’s how you’re thinking about this, don’t. You’re not trying to compete with all of the other scholars in your field (at least, we hope not – if you are, you probably shouldn’t need to be reading this article), you’re just trying to do better than your peers, if possible. This method of coming up with an essay title isn’t about pinpointing a question that you want answered because it’s never before been asked.

Instead, it’s about coming up with an essay title that suits your concerns, your interests and your personal reaction to whatever it is that you’re studying. An off-the-shelf essay title might produce a boring answer because you don’t actually care whether or not the Treaty of Versailles was the main cause of the Second World War, or where morality originates (though you may find these things fascinating). But if, for instance, you can’t get through Jane Austen’s Emma without finding yourself infuriated by the title character, and wonder why on earth Austen would have made her heroine so aggravating – these might seem like petty complaints, but you can make an essay out of it. Austen described Emma as “a heroine whom no-one but myself will much like” – if you find Emma desperately dislikeable, you could probably produce quite an interesting essay on whether or not Austen was right in her assessment of the character. You can apply this principle to anything that strikes you as weird, as annoying, as not quite right, and use that instinct as a springboard to explore a topic properly. While you might prefer to react to your studies with a kind of deep, beard-stroking appreciation, the truth is that an awful lot of great academic investigations of various topics are based on someone looking at them and finding that something irritates them, or doesn’t quite seem to fit, and going on to look at that properly and work out why – and you can do the same.

2. Look at the context

If you look at your topic and nothing stands out to you, then it’s time to start making things stand out. The school curriculum actually makes this quite easy, because we seldom study the typical, run-of-the-mill events, people, books, discoveries and so on. We study the notable ones. We look at how a king did things differently to his predecessors, for instance, rather than the points of continuity – unless there was so much continuity as to be notable in its own right.

When your entire curriculum consists of notable things, however, you can end up with a skewed perspective. We focus more on the reign of Henry VIII – which changed life in Britain forever – than the reign of his father, Henry VII, who brought an end to the Wars of the Roses but arguably the act that had the greatest repercussions for us today was that he successfully handed on the throne to his son. If you’ve learned all about Henry VIII but not so much about Henry VII, you’re unlikely to understand quite how significant the changes enacted by Henry VIII were. This is why looking at the context is vital. This is particularly true for subject where you have to assess an artform, whether that’s Art History, Music, English Literature, Theatre Studies or Film Studies. If you only ever look at the canon – the high points of a particular era – you won’t come to understand what it is that made those particular pieces worthy of studying in the first place. For instance, many students will encounter Shakespeare as their sole example of 16th century drama – but that makes it very hard to see why Shakespeare’s work is so remarkable. Take a quick look at almost any of his competitors, though, and you’ll soon see the difference in depth and quality. And that gives you something to write about: what’s different and why it’s different. When you have a question set for you, your teacher is already drawing your attention to what is notable about the topic. They will ask why Hamlet is indecisive, or why Henry VIII decided to break with Rome – the things that, with greater study of the context, naturally strike people as strange. They won’t ask why Shakespeare wrote a play about a prince rather than a commoner, or why Henry VIII chose to take the throne rather than living out a happy life as a leading tennis player. When you don’t have a question written for you, you have to figure out what’s notable or what’s strange on your own, and that’s why context is so useful.

3. Use your third idea

Writing a column shortly after the death of her father, Alan Coren, Victoria Coren Mitchell recalled his advice on how to come up with a good idea. He said that you shouldn’t use the first idea that you have for something, as that’s the one that everyone will come up with. Nor should you use your second idea, as that’s what the cleverer people who do a little bit more thinking will come up with. You should use your third idea, as that’s the one that only you will be able to think of; it will be entirely your own.

This is excellent advice, and applicable in realms far beyond writing, such as choosing Christmas presents. If the options above for coming up with an essay title haven’t worked for you, try thinking of whatever ideas you can – even if they seem painfully obvious – and eventually you will work through all the ones that other people will think of, and get to something that will be your own to succeed at in your own way. Alan Coren’s description of the advantages of the “third idea” strategy focuses on originality, but that’s not its only advantage. Coming up with an idea that’s yours alone means coming up with an idea that will be right and suited to your thoughts and skills. Your first and second ideas will be based heavily in what you’ve been taught, which is a good base to work from but that might not reflect your interests entirely. Your third idea – hopefully – will come from your own ideas, even if you haven’t quite got a handle on what those ideas are yet. The third idea is also about letting yourself think a little more out of the box. Once you’ve got two nice, safe ideas down on paper, you should be in a position to think of something a bit less conventional. When you’re at school, your teacher might be marking your essay alongside those of twenty other people (or more if they have several classes). An unconventional approach will be a welcome relief among lots of identikit essays, and many teachers will prefer an essay that is interesting, takes risks and doesn’t get everything right over one that is technically perfect but comparatively dull.

4. Use unconventional brainstorming techniques

If all else fails, there are lots of brainstorming techniques available to come up with ideas for just about anything, and one of them might work for your essay. For instance, you could try: Writing down as many bad ideas as you can. This counter-intuitive brainstorming technique helps perfectionists by taking the pressure off. What would be a really terrible essay idea that would make your teacher angry with you for writing it? If you’re stuck in a loop of “can’t think of anything”, this technique can give your brain a jolt, and you may well find that instead of lots of bad ideas, you keep thinking of good ones.

Writing for a set period of time and not letting yourself stop. – Give yourself a certain period of time, which could be five minutes, ten minutes, or the duration of a prog-rock classic, and write about the topic for that length of time. Don’t stop to allow yourself to think about it; just write. This might result in garbage along the lines of “Hamlet is very unkind to Ophelia and even more so to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and absolutely vile to his mother yet he is trying to be a good person, and Horatio still thinks well of him by the end of the play so clearly he is doing something right”, but keep going and you might find the seed of an idea appearing. This technique is related to the first point – whatever it is that you find yourself drifting towards when you’re forced to just keep writing is probably going to be a good topic to think about further.

Looking at it from someone else’s perspective. – This technique has a very broad application across problem-solving: you can look at the issue from the perspective of yourself five years ago, or from the perspective of someone from another country, or someone from a hundred years in the past. For an essay, you might want to think about the approach that a friend would take. Seeing something through someone else’s eyes can highlight a fresh approach that you wouldn’t have thought of while you were fixated on writing the best essay that you yourself can write. Take an abstract noun. – This works best for essays on creative works such as literature or art, but may have application in other fields. Think of an abstract noun – happiness, hope, love, purity, curiosity – and see how it might apply to the thing you’re looking at. Let’s say you’re writing about the Industrial Revolution – think about the role played by hope, or curiosity. You can see how the seeds of an idea can be generated by this approach. How do you come up with great essay ideas? Let us know in the comments! Image credits: Pen and paper , chimp , cat , tree , eureka , stopwatch , lightbulb .

Essay Papers Writing Online

Mastering the art of essay writing – a comprehensive guide.

Essay writing is a fundamental skill that every student needs to master. Whether you’re in high school, college, or beyond, the ability to write a strong, coherent essay is essential for academic success. However, many students find the process of writing an essay daunting and overwhelming.

This comprehensive guide is here to help you navigate the intricate world of essay writing. From understanding the basics of essay structure to mastering the art of crafting a compelling thesis statement, we’ve got you covered. By the end of this guide, you’ll have the tools and knowledge you need to write an outstanding essay that will impress your teachers and classmates alike.

So, grab your pen and paper (or fire up your laptop) and let’s dive into the ultimate guide to writing an essay. Follow our tips and tricks, and you’ll be well on your way to becoming a skilled and confident essay writer!

The Art of Essay Writing: A Comprehensive Guide

Essay writing is a skill that requires practice, patience, and attention to detail. Whether you’re a student working on an assignment or a professional writing for publication, mastering the art of essay writing can help you communicate your ideas effectively and persuasively.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the key elements of a successful essay, including how to choose a topic, structure your essay, and craft a compelling thesis statement. We’ll also discuss the importance of research, editing, and proofreading, and provide tips for improving your writing style and grammar.

By following the advice in this guide, you can become a more confident and skilled essay writer, capable of producing high-quality, engaging essays that will impress your readers and achieve your goals.

Understanding the Essay Structure

When it comes to writing an essay, understanding the structure is key to producing a cohesive and well-organized piece of writing. An essay typically consists of three main parts: an introduction, the body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Introduction: The introduction is where you introduce your topic and provide some background information. It should also include your thesis statement, which is the main idea or argument that you will be discussing in the essay.

Body paragraphs: The body of the essay is where you present your supporting evidence and arguments. Each paragraph should focus on a separate point and include evidence to back up your claims. Remember to use transition words to link your ideas together cohesively.

Conclusion: The conclusion is where you wrap up your essay by summarizing your main points and restating your thesis. It is also a good place to make any final thoughts or reflections on the topic.

Understanding the structure of an essay will help you write more effectively and communicate your ideas clearly to your readers.

Choosing the Right Topic for Your Essay

One of the most crucial steps in writing a successful essay is selecting the right topic. The topic you choose will determine the direction and focus of your writing, so it’s important to choose wisely. Here are some tips to help you select the perfect topic for your essay:

| Choose a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Writing about something you enjoy will make the process more enjoyable and your enthusiasm will come through in your writing. | |

| Do some preliminary research to see what topics are available and what resources are out there. This will help you narrow down your choices and find a topic that is both interesting and manageable. | |

| Think about who will be reading your essay and choose a topic that will resonate with them. Consider their interests, knowledge level, and any biases they may have when selecting a topic. | |

| Take some time to brainstorm different topic ideas. Write down all the potential topics that come to mind, and then evaluate each one based on relevance, interest, and feasibility. | |

| Try to choose a topic that offers a unique perspective or angle. Avoid overly broad topics that have been extensively covered unless you have a fresh take to offer. |

By following these tips and considering your interests, audience, and research, you can choose a topic that will inspire you to write an engaging and compelling essay.

Research and Gathering Information

When writing an essay, conducting thorough research and gathering relevant information is crucial. Here are some tips to help you with your research:

| Make sure to use reliable sources such as academic journals, books, and reputable websites. Avoid using sources that are not credible or biased. | |

| As you research, take notes on important information that you can use in your essay. Organize your notes so that you can easily reference them later. | |

| Don’t rely solely on one type of source. Utilize a variety of sources to provide a well-rounded perspective on your topic. | |

| Before using a source in your essay, make sure to evaluate its credibility and relevance to your topic. Consider the author’s credentials, publication date, and biases. | |

| Make sure to keep a record of the sources you use in your research. This will help you properly cite them in your essay and avoid plagiarism. |

Crafting a Compelling Thesis Statement

When writing an essay, one of the most crucial elements is the thesis statement. This statement serves as the main point of your essay, summarizing the argument or position you will be taking. Crafting a compelling thesis statement is essential for a strong and cohesive essay. Here are some tips to help you create an effective thesis statement:

- Be specific: Your thesis statement should clearly state the main idea of your essay. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Make it arguable: A strong thesis statement is debatable and presents a clear position that can be supported with evidence.

- Avoid clichés: Stay away from overused phrases or clichés in your thesis statement. Instead, strive for originality and clarity.

- Keep it concise: Your thesis statement should be concise and to the point. Avoid unnecessary words or phrases.

- Take a stand: Your thesis statement should express a clear stance on the topic. Don’t be afraid to assert your position.

By following these guidelines, you can craft a compelling thesis statement that sets the tone for your essay and guides your reader through your argument.

Writing the Body of Your Essay

Once you have your introduction in place, it’s time to dive into the body of your essay. The body paragraphs are where you will present your main arguments or points to support your thesis statement.

Here are some tips for writing the body of your essay:

- Stick to One Main Idea: Each paragraph should focus on one main idea or argument. This will help keep your essay organized and easy to follow.

- Use Topic Sentences: Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph.

- Provide Evidence: Support your main points with evidence such as facts, statistics, examples, or quotes from experts.

- Explain Your Points: Don’t just state your points; also explain how they support your thesis and why they are important.

- Use Transition Words: Use transition words and phrases to connect your ideas and create a smooth flow between paragraphs.

Remember to refer back to your thesis statement and make sure that each paragraph contributes to your overall argument. The body of your essay is where you can really showcase your critical thinking and analytical skills, so take the time to craft well-developed and coherent paragraphs.

Perfecting Your Essay with Editing and Proofreading

Editing and proofreading are essential steps in the essay writing process to ensure your work is polished and error-free. Here are some tips to help you perfect your essay:

- Take a Break: After writing your essay, take a break before starting the editing process. This will help you look at your work with fresh eyes.

- Focus on Structure: Check the overall structure of your essay, including the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Make sure your ideas flow logically and cohesively.

- Check for Clarity: Ensure that your arguments are clear and easy to follow. Eliminate any jargon or confusing language that might obscure your message.

- Grammar and Punctuation: Review your essay for grammar and punctuation errors. Pay attention to subject-verb agreement, verb tense consistency, and proper punctuation usage.

- Use a Spell Checker: Run a spell check on your essay to catch any spelling mistakes. However, don’t rely solely on spell checkers as they may miss certain errors.

- Read Aloud: Read your essay aloud to yourself or have someone else read it to you. This can help you identify awkward phrasing or unclear sentences.

- Get Feedback: Consider getting feedback from a peer, teacher, or writing tutor. They can offer valuable insights and suggestions for improving your essay.

By following these editing and proofreading tips, you can ensure that your essay is well-crafted, organized, and free of errors, helping you make a strong impression on your readers.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, how to come up with a unique college essay idea.

Hey everyone! I'm currently brainstorming ideas for my college essays, but I'm having trouble coming up with something unique and personal. How did you guys find inspiration for your essays and what approach did you take? Any tips would be greatly appreciated!

Finding a unique and personal college essay idea can feel daunting, but with some effort and introspection, you can uncover an interesting topic that reflects who you are. Consider the following tips to help you get started:

1. Reflect on your experiences: Take some time to think about events or experiences in your life that have shaped you. This could be a challenging situation you've faced, an achievement that you're particularly proud of, or a surprising hobby or interest that sets you apart. Reflecting on your life's path will help you identify central moments that reveal your values, beliefs, and character.

2. Identify your "spike": A "spike" is a highly developed specialty or unique strength. Top colleges are looking for applicants who demonstrate expertise, passion, or a high level of skill in a specific area. Narrow down your focus and think about what makes you stand out. It could be your dedication to a sport, your commitment to community service, or your talent for a particular art form.

3. Consider your surroundings: Sometimes your environment, family, or culture can provide you with inspiration. Think about the traditions or customs that have influenced your life and how they've contributed to your personal development. Remember to avoid cliché topics like cultural adjustments or learning a new language and focus instead on more specific and personal experiences.

4. Search for small moments: Unique essay ideas often come from small, everyday moments rather than major life milestones. Think about what you enjoy doing in your free time, instances when you've faced a moral dilemma, or moments when you've connected with others. These small moments can help illuminate your personality and values.

5. Brainstorm creatively: Make a list of potential essay topics, write a mind map, or use free-writing exercises to explore your thoughts and memories. The more ideas you come up with, the more likely you are to discover an unexpected and engaging topic.

6. Seek feedback: Share your essay ideas with trusted friends, family members, or mentors. They can offer feedback on which ideas are most compelling and authentic, and might even recall unique situations or experiences that you haven't considered.

7. Be authentic: Your essay should showcase your true self, so don't choose a topic just because you think it will impress admissions officers. Stick with a subject that genuinely interests you and reflects your values—this will lead to a more engaging and memorable essay.

Remember, the goal of your essay is to provide a glimpse into your personality, perspective, and values. By digging deep and exploring your experiences, you can uncover a unique and personal essay topic that will make a lasting impression on admissions officers.

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Structure an Essay

Essay writing is a fundamental skill, a basic task, that is expected of those who choose to pursue their undergraduate and master’s degrees. It constitutes a key requirement for students to complete a given course credit. However, many students and early career researchers find themselves struggling with the challenge of organizing their thoughts into a coherent, engaging structure. This article is especially for those who see essay writing as a daunting task and face problems in presenting their work in an impactful way.

Table of Contents

- Writing an essay: basic elements and some key principles

- Essay structure template

- Chronological structure

- Problem-methods-solutions structure

- Compare and contrast structures

- Frequently asked questions on essay structure

Read on as we delve into the basic elements of essay writing, outline key principles for organizing information, and cover some foundational features of writing essays.

Writing an essay: basic elements and some key principles

Essays are written in a flowing and continuous pattern but with a structure of its own. An introduction, body and conclusion are integral to it. The key is to balance the amount and kind of information to be presented in each part. Various disciplines may have their own conventions or guidelines on the information to be provided in the introduction.

A clear articulation of the context and background of the study is important, as is the definition of key terms and an outline of specific models or theories used. Readers also need to know the significance of the study and its implications for further research. Most importantly, the thesis or the main proposition should be clearly presented.

The body of the essay is therefore organized into paragraphs that hold the main ideas and arguments and is presented and analyzed in a logical manner. Ideally, each paragraph of the body focuses on one main point or a distinct topic and must be supported by evidence and analysis. The concluding paragraph should bring back to the reader the key arguments, its significance and food for thought. It is best not to re-state all the points of the essay or introduce a new concept here.

In other words, certain general guidelines help structure the information in the essay. The information must flow logically with the context or the background information presented in the introductory part of the essay. The arguments are built organically where each paragraph in the body of the essay deals with a different point, yet closely linked to the para preceding and following it. Importantly, when writing essays, early career researchers must be careful in ensuring that each piece of information relates to the main thesis and is a building block to the arguments.

Essay structure template

- Introduction

- Provide the context and share significance of the study

- Clearly articulate the thesis statement

- Body

- Paragraph 1 consisting of the first main point, followed by supporting evidence and an analysis of the findings. Transitional words and phrases can be used to move to the next main point.

- There can be as many paragraphs with the above-mentioned elements as there are points and arguments to support your thesis.

- Conclusion

- Bring in key ideas and discuss their significance and relevance

- Call for action

- References

Essay structures

The structure of an essay can be determined by the kind of essay that is required.

Chronological structure

Also known as the cause-and-effect approach, this is a straightforward way to structure an essay. In such essays, events are discussed sequentially, as they occurred from the earliest to the latest. A chronological structure is useful for discussing a series of events or processes such as historical analyses or narratives of events. The introduction should have the topic sentence. The body of the essay should follow a chorological progression with each para discussing a major aspect of that event with supporting evidence. It ends with a summarizing of the results of the events.

Problem-methods-solutions structure

Where the essay focuses on a specific problem, the problem-methods-solutions structure can be used to organize the essay. This structure is ideal for essays that address complex issues. It starts with presenting the problem, the context, and thesis statement as introduction to the essay. The major part of the discussion which forms the body of the essay focuses on stating the problem and its significance, the author’s approach or methods adopted to address the problem along with its relevance, and accordingly proposing solution(s) to the identified problem. The concluding part offers a recap of the research problem, methods, and proposed solutions, emphasizing their significance and potential impact.

Compare and contrast structures

This structure of essay writing is ideally used when two or more key subjects require a comparison of ideas, theories, or phenomena. The three crucial elements, introduction, body, and conclusion, remain the same. The introduction presents the context and the thesis statement. The body of the essay seeks to focus on and highlight differences between the subjects, supported by evidence and analysis. The conclusion is used to summarize the key points of comparison and contrast, offering insights into the significance of the analysis.

Depending on how the subjects will be discussed, the body of the essay can be organized according to the block method or the alternating method. In the block method, one para discusses one subject and the next para the other subject. In the alternative method, both subjects are discussed in one para based on a particular topic or issue followed by the next para on another issue and so on.

Frequently asked questions on essay structure

An essay structure serves as a framework for presenting ideas coherently and logically. It comprises three crucial elements: an introduction that communicates the context, topic, and thesis statement; the body focusing on the main points and arguments supported with appropriate evidence followed by its analysis; and a conclusion that ties together the main points and its importance .

An essay structure well-defined essay structure enhances clarity, coherence, and readability, and is crucial for organizing ideas and arguments to effectively communicate key aspects of a chosen topic. It allows readers to better understand arguments presented and demonstrates the author’s ability to organize and present information systematically.

Yes, while expert recommend following an essay structure, early career researchers may choose how best to adapt standard essay structures to communicate and share their research in an impactful and engaging way. However, do keep in mind that deviating too far from established structures can hinder comprehension and weaken the overall effectiveness of the essay, By understanding the basic elements of essay writing and employing appropriate structures such as chronological, problem-methods-solutions, or compare and contrast, researchers can effectively organize their ideas and communicate their findings with clarity and precision.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

Powerful academic phrases to improve your essay writing .

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- How to Use AI to Enhance Your College Essays and Thesis

- How to Cite Social Media Sources in Academic Writing?

Leveraging Generative AI to Enhance Student Understanding of Complex Research Concepts

You may also like, leveraging generative ai to enhance student understanding of..., how to write a good hook for essays,..., addressing peer review feedback and mastering manuscript revisions..., how paperpal can boost comprehension and foster interdisciplinary..., what is the importance of a concept paper..., how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to ace grant writing for research funding..., how to write a high-quality conference paper.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples

How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on February 4, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A good introduction paragraph is an essential part of any academic essay . It sets up your argument and tells the reader what to expect.

The main goals of an introduction are to:

- Catch your reader’s attention.

- Give background on your topic.

- Present your thesis statement —the central point of your essay.

This introduction example is taken from our interactive essay example on the history of Braille.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: hook your reader, step 2: give background information, step 3: present your thesis statement, step 4: map your essay’s structure, step 5: check and revise, more examples of essay introductions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the essay introduction.

Your first sentence sets the tone for the whole essay, so spend some time on writing an effective hook.

Avoid long, dense sentences—start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

The hook should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of the topic you’re writing about and why it’s interesting. Avoid overly broad claims or plain statements of fact.

Examples: Writing a good hook

Take a look at these examples of weak hooks and learn how to improve them.

- Braille was an extremely important invention.

- The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability.

The first sentence is a dry fact; the second sentence is more interesting, making a bold claim about exactly why the topic is important.

- The internet is defined as “a global computer network providing a variety of information and communication facilities.”

- The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education.

Avoid using a dictionary definition as your hook, especially if it’s an obvious term that everyone knows. The improved example here is still broad, but it gives us a much clearer sense of what the essay will be about.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a famous book from the nineteenth century.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement.

Instead of just stating a fact that the reader already knows, the improved hook here tells us about the mainstream interpretation of the book, implying that this essay will offer a different interpretation.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, give your reader the context they need to understand your topic and argument. Depending on the subject of your essay, this might include:

- Historical, geographical, or social context

- An outline of the debate you’re addressing

- A summary of relevant theories or research about the topic

- Definitions of key terms