- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Black Consciousness Movement (BCM)

On 12 September 1977, the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko died while in the custody of security police. The period leading up to his death, beginning with the June 1976 unrest, had seen some of the most turbulent events in South African history, the first signs that the apartheid regime would not be able to maintain its oppressive rule without massive resistance.

The Soweto riots were followed by continuous unrest: students and workers in the townships of every province boycotted schools, universities and workplaces, and the regime was hard put to restore the apartheid order. By mid-1977, this had by and large been achieved, but elements of resistance and defiance continued to emerge.

Biko’s death threatened to unleash a new wave of protests, and drew the attention of the world to the situation in South Africa. Biko’s funeral on 25 September was attended by some 15000 people, including the American ambassador and 11 other diplomats. A ban on open-air gatherings was extended to March 1978.

The outrage of the US Congress at Biko’s death became evident when 128 of its members from both the Republican and Democratic parties sent a letter to the government urging that it allow an international team to go to South Africa to examine laws relating to political prisoners and detention.

By 18 October, the Cabinet had decided to rack down on the most prominent Blak Consciousness-aligned organisations, and the next day, on 19 October, the government went ahead and banned 18 organisations (listed below). About 70 activists were arrested, including several members of the Soweto Committee of Ten, and many were banned, including Biko’s friend and supporter, editor of the Daily Despatch, Donald Woods . Two newspapers, The World and The Weekend World, were also closed down.

International outrage now took a more serious turn. The US, the Netherlands, Great Britain, West Germany and Belgium all recalled their ambassadors for consultations.

Instead of embarking on a process of reform, the apartheid government took steps to clamp down on resistance, and bolstered its means of keeping the Black population in check. One of the most significant of these was the power to curtail freedom of speech and the publication of material it deemed subversive.

By 28 October, the government enforced the Newspaper and Imprint Registration Act no 19, a version of an earlier act that required that all newspapers be registered and conform to a strict code of conduct. Newspapers were also required to lodge a large amount of money (in the region of R40000) as a deposit before they could publish. The move was essentially a means to ensure that newspapers toed the line and regulated themselves, lest they be banned.

Organisations banned on 19 October 1977:

- Black People's Convention (BPC)

- South African Students' Organisation (SASO)

- South African Students' Movement (SASM)

- Union of Black Journalists

- Black Community Programmes Limited (BCP)

- Black Parents' Association (BPA)

- Border Youth Organisation

- Soweto Students' Representative Council (SSRC)

- African Social Education and Cultural Education (ASSECA)

- Black Women's Federation

- National Youth Organisation

- Eastern Province Youth Organisation

- Medupe Writers' Association

- Natal Youth Organisation

- Transvaal Youth Organisation

- Western Cape Youth Organisation

- Zimele Trust Fund

- Siyazinceda Trust Fund

Timeline: The Black Consciousness Movement

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HSTORY T2 Gr. 12 Black Consciousness Essay

Grade 12: The Challenge of Black Consciousness to the Apartheid State (Essay) PPT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Diaspora

- Afrocentrism

- Archaeology

- Central Africa

- Colonial Conquest and Rule

- Cultural History

- Early States and State Formation in Africa

- East Africa and Indian Ocean

- Economic History

- Historical Linguistics

- Historical Preservation and Cultural Heritage

- Historiography and Methods

- Image of Africa

- Intellectual History

- Invention of Tradition

- Language and History

- Legal History

- Medical History

- Military History

- North Africa and the Gulf

- Northeastern Africa

- Oral Traditions

- Political History

- Religious History

- Slavery and Slave Trade

- Social History

- Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Women’s History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

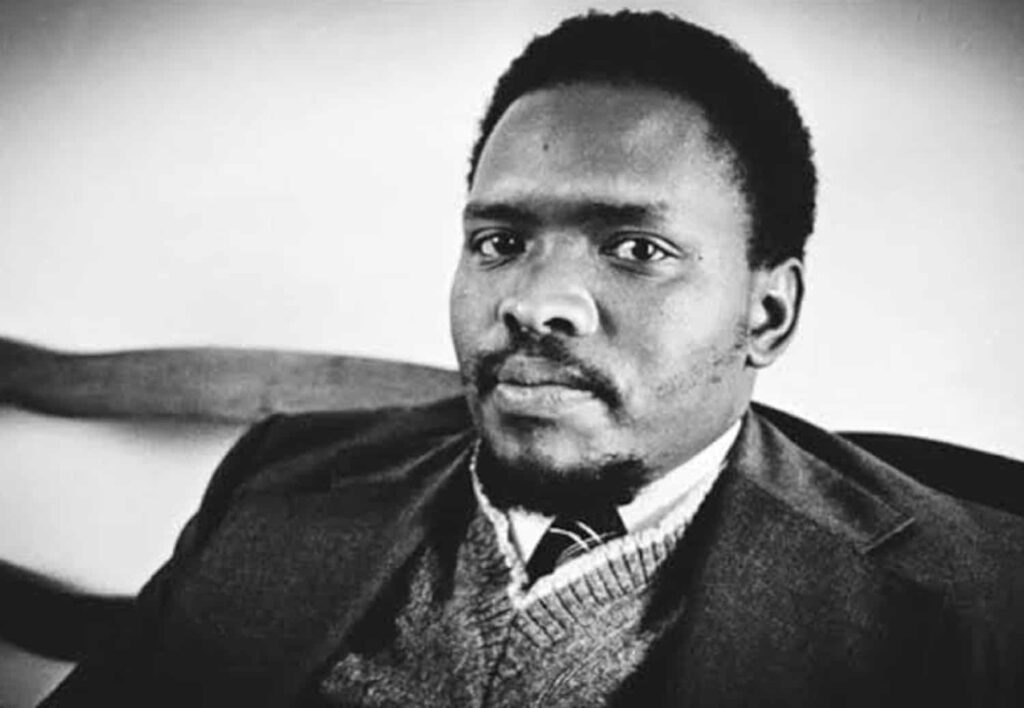

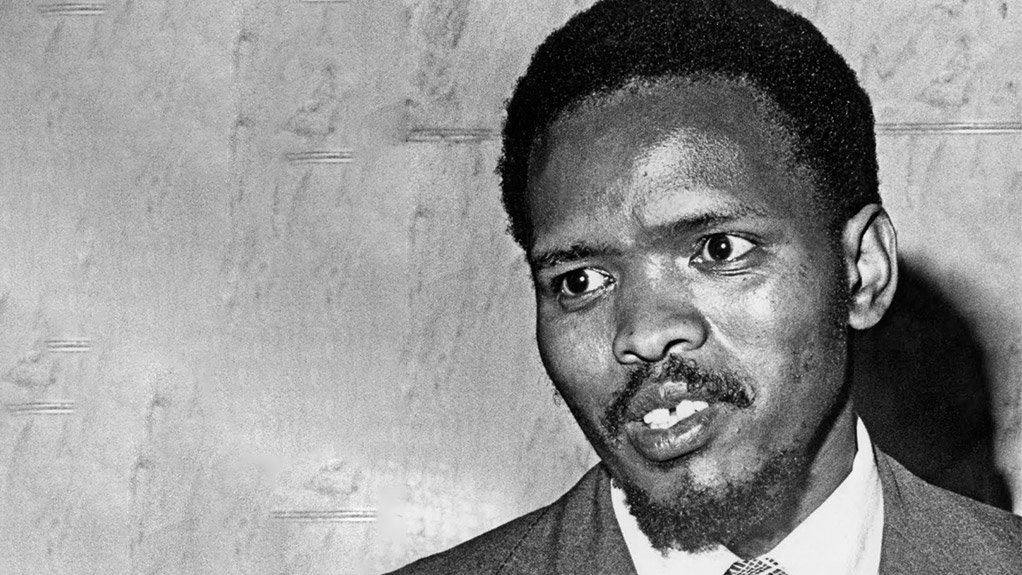

Steve biko and the black consciousness movement.

- Leslie Anne Hadfield Leslie Anne Hadfield Department of History, Brigham Young University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.83

- Published online: 27 February 2017

The Black Consciousness movement of South Africa instigated a social, cultural, and political awakening in the country in the 1970s. By the mid-1960s, major anti-apartheid organizations in South Africa such as the African National Congress and Pan-Africanist Congress had been virtually silenced by government repression. In 1969, Steve Biko and other black students frustrated with white leadership in multi-racial student organizations formed an exclusively black association. Out of the South African Students’ Organization (SASO) came what was termed Black Consciousness. This philosophy redefined “black” as an inclusive, positive identity and taught that black South Africans could make meaningful change in their society if “conscientized” or awakened to their self-worth and the need for activism. The movement emboldened youth, contributed to the development of Black Theology and cultural movements, and led to the formation of new community and political organizations such as the Black Community Programs organization and the Black People’s Convention.

Articulate and charismatic, Steve Biko was one of the movement’s foremost instigators and prolific writers. When the South African government understood the threat Black Consciousness posed to apartheid, it worked to silence the movement and its leaders. Biko was banished to his home district in the Eastern Cape, where he continued to build community development programs and have a strong political influence. His death at the hands of security police in September 1977 revealed the brutality of South African security forces and the extent to which the state would go to maintain white supremacy. After Biko’s death, the state declared Black Consciousness–related organizations illegal. Activists formed the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO) in 1978 to carry on Black Consciousness ideals, though the movement in general waned after Biko’s death. Since then, Biko has loomed over the history of the Black Consciousness movement as a powerful icon and celebrated hero while others have looked to Black Consciousness in forging a new black future for South Africa.

- Black Consciousness

- South African Student’s Organization

- liberation movements

The Rise of Black Consciousness

The Black Consciousness movement became one of the most influential anti-apartheid movements of the 1970s in South Africa. While many parts of the African continent gained independence, the apartheid state increased its repression of black liberation movements in the 1960s. In the latter part of the decade, the major anti-apartheid organizations worked underground or in exile. The state also increased its extra-legal tactics of intimidation, silencing some activists by kidnapping or killing them. This state action crippled anti-apartheid activity and instilled a sense of fear in the larger black community. The state also began creating so-called homelands—small reserves intended to become independent countries for specific ethnic groups to curb black political opposition and urbanization while retaining access to black labor. All of this perpetuated deep-seated cultural racism in South Africa.

As state repression increased, universities and churches tended to have greater freedom to speak out against the government and facilitated the sharing of ideas. The 1960s saw an increase in Christian social movements and growing opposition to apartheid in churches and ecumenical organizations. Both economic prosperity and greater government control led to higher numbers of black students in primary and secondary schools and the expansion of black universities, segregated according to ethnicity. Although apartheid education restricted black aspirations, these schools also became places of politicization where black students could come together and share ideas and experiences. These elements along with the daily experiences and interpretations of individuals who made up the Black Consciousness movement all contributed to its growth. As emerging young adults unencumbered by the fear of older generations, these activists looked for a way to fundamentally change their society. They did this first by targeting the mind of black people in South Africa. But the movement was also about immediate and relevant action that would make South Africans self-reliant. In other words, it sought a full liberation of black South Africans by starting at the level of the individual, an approach not overtly political to begin with.

SASO and Black Consciousness

The beginning of the movement is marked by the formation of the South African Students’ Organization (SASO), officially launched in July 1969 . Black students at various universities, especially at the University of Natal Medical School–Black Section (UNB), the University of Fort Hare, and the University of the North at Turfloop, became increasingly frustrated with the limits of white student leadership in multiracial organizations. At a National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) meeting held in Grahamstown in 1967 and a University Christian Movement (UCM) conference in Stutterheim in July 1968 , the mostly white leadership would not act decisively to challenge the enforced racial segregation of accommodations for the students at the conference. Led primarily by Steve Biko and Barney Pityana, black students decided to form an exclusively black organization to more effectively advance the cause of the oppressed in South Africa.

SASO laid the foundation for what would grow beyond universities and student groups to become a wider movement. It was in SASO that activists formulated the Black Consciousness philosophy. SASO students also started engaging in community development programs and artistic and literary production and eventually moved into political defiance against the state.

Members of SASO as university students had access to a number of different ideas and engaged with each other—students who came to universities with diverse backgrounds, but similar experiences. They also had access to news media and reading materials through student-activist networks. As they debated and read materials from various parts of Africa and the African diaspora, these students formulated what they began to call Black Consciousness. In addition to the influences of various South African perspectives and their experience in student politics, a number of philosophers and leaders from the African continent and the African diaspora helped shape their thinking. Daniel Magaziner described them as “autonomous shoppers in the marketplace of ideas.” 1 SASO students studied Franz Fanon’s analysis of the psychological impact of colonialism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s dialectical analysis, Zambia’s K. K. Kaunda’s African humanism, and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere’s version of African socialism that emphasized self-reliance and development for liberation. They also read from black American authors, particularly identifying with the Black Power movement (even adopting the raised fist as a gesture of black pride in South Africa) and analyzing the Black Theology of James Cone. SASO students also drew upon the writings of Brazil’s educationalist, Paulo Freire, from which they derived the idea of “to conscientize”—to awaken people to a critical awareness of their situation and their ability to change their situation.

Black Consciousness began to be defined as “an attitude of mind” or “way of life” of black people who believed in their potential and value as black people and saw the need for black people to work together for a holistic liberation. SASO students explained South Africa’s main problem as twofold: white racism and black acquiescence to that racism. They felt that in general, black people had accepted their own inferiority in society. Without a positive, creative sense of self, black people would not challenge the status quo. “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor [was] the mind of the oppressed,” Biko argued. 2 Thus, Black Consciousness activists worked to change the black mindset, to look inward to build black capacity to realize their own liberation. Biko wrote that colonialism, missionaries, and apartheid had made the black man “a shell, a shadow of man, completely defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.” He continued:

This is the first truth, bitter as it may seem, that we have to acknowledge before we can start on any programme [ sic ] designed to change the status quo…. The first step therefore is to make the black man come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be misused and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the country of his birth. 3

In affecting a black psychological, social, economic, and even spiritual liberation, activists saw two aspects as vitally important. First, they defined black as a new positive definition that included all people of color discriminated against by the color of their skin. This was a new approach to grouping people divided into apartheid into Coloureds (mixed-race people), Indians, and various black African ethnic groups. They wanted to make South Africa African in the end (though they had a vaguely defined future) but used a political definition of black that referred to a shared experience and outlook that was more cosmopolitan in celebrating black values and culture. A positive black identity would increase black people’s faith in their own potential. Black unity also presented a stronger front against apartheid. SASO came to strongly reject the participation of black South Africans in any apartheid institution that emphasized ethnic separation (including the so-called African homelands). Second, Black Consciousness activists rejected white liberals (whom they defined as any white person seeking to oppose apartheid). They saw white leadership as an obstacle to black liberation because it stifled black leadership and psychological development. As black people understood fully the oppression they experienced firsthand, activists believed they had the insights and knowledge to know what needed to change. White leadership would hinder the development of a truly self-reliant, black society. The phrase “Black man you are on your own” became a slogan of the movement. For many people, including white liberals, this came across as abrasive and startling. Some even accused SASO of promoting reverse racism. For others, it led to a refreshing, emboldened new consciousness.

SASO began with a few black students who worked to recruit other students across black campuses. This was not always easy, but strongholds developed at the University of the North, Zululand, Fort Hare, the Western Cape, and in Durban. SASO students in these various universities traveled around trying to prompt a psychological change among blacks in a number of ways. From the beginning of SASO, students engaged in community work. This began as a way to relieve the suffering of black people in poverty. Yet community projects were also seen as a way to uplift black communities psychologically as well as to improve black self-reliance. Each campus group ran projects in neighboring communities, such as volunteering in local clinics, helping to secure a clean water supply, and running education and literacy programs. The students learned from their experiences and drew upon the methodologies of Freire in particular to help them refine this work.

SASO also spread Black Consciousness through the SASO Newsletter , wherein activists described their philosophy, shared news, and dealt with the nature of their oppression. Asserting the right to speak was important for these activists and they claimed this right in the newsletter, along with other literary forms such as poems and plays. The newsletter also reported on various student meetings where students developed their thinking, debated strategies for the future, and discussed how to engage with the broader community. So-called formation schools—weekend or holiday camps—served as training grounds where students debated societal issues and learned organizational strategies. Acutely aware of the politically hostile environment within which it worked, SASO made it a point to train a number of layers of leadership to ensure the organization would continue if state repression were to hit.

A marker of the “attitude” and “way of life” of Black Consciousness activists was the way they carried themselves. The clothes they wore, their demeanor when interacting with white people, and the music they listened to all portrayed confidence and pride in blackness. The young women involved in the Black Consciousness especially challenged the status quo with new styles by throwing away their skin-lightening creams and wigs and wearing their hair in natural Afros. They also wore bold styles in clothing that pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable at the time, such as very tight pants. Some even smoked cigarettes in public. Though female students were involved in the movement from the beginning—prominent SASO women include Vuyelwa Mashalaba, Deborah Matshoba, Daphne Matshoba, Lindelwe Mabandla, Mamphela Ramphele, Thenjiwe Mthintso—the movement was dominated by male students. Women’s issues were tabled in favor of focusing on black liberation. Female activists had to excel at male ways of debating to gain an influence in SASO. The students also held parties where young women were treated more as objects of sexual desire. For some, this means that women had more conservative roles in the movement; however, some women did gain leadership in the movement, especially in community projects where they challenged conventional gender roles.

The Broader Movement

Before the state took action to suppress Black Consciousness, its influence had expanded beyond university campuses. With the spread of ideas and expansion of organizations linked to Black Consciousness, what began as a student organization grew into a movement with a broad, diffused impact that can be difficult to generalize about or trace precisely.

Cultural Movement

The movement had cultural dimensions, linked in varying degrees to formal organizations. Black Consciousness ideas resonated with poets and theater groups in particular. Some worked directly with SASO. For example, a group of black students and actors from Durban, many of Indian descent, performed their plays at SASO events (these activists formed the Theatre Council of Natal or TECON as well as the South African Black Theatre Union or SABTU). Their plays, such as Black on White and Resurrection , examined what it meant to be black and oppressed in South Africa. Participants and playwrights such as Asha Rambally Moodley and Strinivasa Moodley joined Black Consciousness organizations, while others simply continued to use theater as a way to raise a critical awareness among black communities. Poets such as Oswald Mtshali, Mongane Wally Serote, Don Mattera, Mafika Pascal Gwala, and James Matthews, among others, similarly dealt with black oppression and sought to inspire hope in black self-determination with positive images and themes of resistance and redemption. Black Consciousness promoted music with black themes and origins and influenced the outlook and material in Sowetan literary magazines, such as The Classic , New Classic , and Staffrider . 4 As Mbulelo Mzamane has argued, Black Consciousness effectively used culture as a form of affecting a black awakening and resisting white supremacy in an oppressive political climate. 5

Black Theology

Black Consciousness also contributed to the development of Black Theology in South Africa. Ecumenical organizations, Christian activists, and Black Consciousness adherents all influenced each other. The University Christian Movement (UCM) established a project spearheaded by Sabelo Stanley Ntwasa on Black Theology coming from the United States—an interpretation of Christianity that taught that Christ came to liberate the poor and oppressed, the black populations in the United States and South Africa. SASO joined the UCM in engaging Black Theology in the South African context and resolved to influence a change in leadership in South African churches. SASO and other Black Consciousness organizations supported conferences focused on examining Christianity’s relevancy to black South Africans. 6 A number of those influenced by Black Theology later became leaders of Christian resistance and contextual theology, such as Alphaeus Zulu, Manas Buthelezi, Desmond Tutu, Allan Boesak, and Frank Chikane. Activists worked closely with radical priests and ecumenical organizations, significantly putting these Christian ideals into action. 7

Black Community Programs

In September of 1971 , the Christian Institute and the South African Council of Churches appointed Bennie Khoapa as the director of a division of their Special Project on Christian Action in Society (Spro-cas 2). As the head of the Black Community Programs (BCP), Khoapa combined Christian action with the Black Consciousness philosophy. The organization sought to coordinate among other agencies run by and in the black community and to conscientize black South Africans through publication projects that provided relevant news for black people and promoted a positive black identity. The BCP eventually moved to run its own projects when activists working for the organization found themselves restricted to their home areas by banning orders in 1973 . For example, it ran health clinics such as the Zanempilo Community Health Center in the Eastern Cape, managed cottage industries like the Njwaxa leatherwork factory also in the Eastern Cape, and opened resource centers at its regional offices. It published a yearbook, Black Review . The BCP gave practical expression to Black Consciousness ideals. BCP publications encouraged black publishing in South Africa and became a trusted source of positive information in black communities. Research in villages where the BCP ran its projects has demonstrated that health and economic projects in the Eastern Cape improved black people’s physical conditions and helped villagers gain a greater sense of human dignity. Through this work, the BCP also significantly addressed women’s issues and female activists proved themselves as capable leaders and respected colleagues. 8

The Black People’s Convention

At the same time that some activists saw community and cultural work as essential for reaching their goals, others advocated for a national organization to push for more immediate political change. This led to the formation of the Black People’s Convention (BPC). In 1971 at meetings of various black agencies to discuss the formation of a national coordinating organization (including the Interdenominational African Ministers’ Association and the Association for the Educational and Cultural Advancement of the African People), proponents of establishing an overtly political organization (such as Aubrey Mokoape and Harry Nengwekhulu) gained a majority over those who saw community development as a more sure way of building up strength for future political work. The BPC was launched in July 1972 and held its first national conference in December, where Winifred Kgware was elected as one its first president. The principal aim of the BPC was defined as fostering black political unity in the Black Consciousness sense in order to achieve psychological and physical liberation. This included creating an egalitarian society, developing Black Theology, and condemning foreign countries working with the apartheid government, among other objectives. The BPC was the first black national political organization formed since 1960 and took a strong stance of non-participation in the apartheid system. Membership did not grow as rapidly or as widely as the BPC hoped. By the end of 1973 , the BPC had forty-one branches. Still, the BPC helped organize the pro-FRELIMO rallies and continued to refine its future vision for South Africa, including the much debated Mafeking Manifesto that outlined a specific mixed-economy future for South Africa. 9

Youth and Leadership

Activists also influenced high school students and the development of youth movements, directly and indirectly. SASO and the BCP held youth leadership conferences or formation schools that engaged students in critical social analysis and taught organizational skills. These meetings eventually led to the formation of regional youth organizations and the National Youth Organization (NYO, formed in 1973 ). In Soweto, where student organizations had already been operating, SASO students and events in general helped spread Black Consciousness among high school students. SASO leader Onkgopotse Abraham Tiro, expelled from the University of the North, and other SASO students ended up teaching in high schools in Soweto. The already existing African Student Movement changed its name to the South African Student Movement (SASM), to be more inclusive. It was SASM that organized the June 16, 1976 , Soweto student march against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction that led to widespread uprisings. Although the Black Consciousness movement cannot claim credit for orchestrating the Soweto Uprisings, the movement’s bold assertion of black self-worth and self-reliance clearly influenced high school students, and SASM aligned itself to Black Consciousness organizations. The student uprisings of 1976 , along with other adult leaders who became involved in running community programs in Soweto (such as Ramsey Ramokgopa and Oshadi Mangena), are evidence of the way Black Consciousness ideas changed South African thinking among different groups of people in various corners of the country. 10

Clashes with the State

State repression profoundly shaped the context and direction of the Black Consciousness movement. Aware of the way the state cracked down on resistance in the early 1960s, SASO leaders deliberately avoided confrontation with the state in order to evade crippling state action. Still, activists took care to nurture leadership so that replacements were ready to fill in positions if the police detained people in leadership roles. Initially, the state saw the formation of an exclusively black student organization as fitting with apartheid. However, it soon understood that Black Consciousness undermined the whole philosophy behind apartheid and increasingly bore down on the movement and its leaders. The state’s efforts to silence activists included bans on individuals (legal orders that restricted a person’s movement, political involvement, and public presence), numerous detentions without trial (for up to 180 days at times), and constant police surveillance and intimidation. Activists learned to outwit the police. Their youthful energy and audacity sustained their activity in this politically hostile environment. They also found hope in suffering at the hands of the state because they viewed it as a sacrifice that advanced South Africa closer to liberation. 11

Confrontation with the state escalated first in 1972 , when Tiro, the Student Representative Council president at the University of the North, gave a speech criticizing the university’s white leadership and the racial discrimination infused in its education. The university expelled Tiro. This sparked a number of black student strikes across the country. Many of these students were in turn expelled and at the beginning of 1973 ; the state placed banning orders on a number of SASO leaders including Biko, Pityana, Nengwekhulu, Saths Cooper, Strini Moodley, and Bokwe Mafuna. This scattered activists throughout the country, although they found ways to continue their work.

State repression of Black Consciousness activists intensified in the next few years, especially as activists took more overt action against the state. A particularly important move in this direction was the pro-FRELIMO rallies held at the University of the North and in Durban in September 1974 to celebrate the liberation of a neighboring country from European colonialism and express their support for the people of Mozambique. The minister of justice declared the rallies illegal just before they were to take place. The leaders of SASO and the BPC decided to go through with their original plans, even if it meant violent clashes with police. Police did indeed break up the rallies using some violence. This led to further arrests and detentions of activists and a publicized court case that essentially put Black Consciousness on trial ( State v. Cooper et al., also known as the SASO-BPC trial). Nine men were tried and convicted of encouraging racial hostility. 12 Even if not all Black Consciousness activists agreed with the way the rallies were held, this move marked them more firmly as enemies of the state and gave the movement a more public place in anti-apartheid politics.

Police harassment, detentions, and bannings spiked again after the 1976 student uprisings and continued into 1977 . This took a toll on the lives of many activists. Detentions put a psychological strain on individuals and their families, and increasingly brutal torture inflicted physical damage. Four Black Consciousness activists died between 1972 and 1977 as a result of the actions of South African security forces: Mthuli ka Shezi was pushed onto a train track in 1972 , Tiro was letter-bombed in Botswana in 1974 , Mapetla Mohapi (SASO organizer) was killed in the Kei Road police station in 1976 , and Biko died at the hands of the security police in 1977 .

Bantu Stephen Biko, the most prominent figure of the Black Consciousness movement, was not the only student, thinker, writer, and community project director in the movement, but he did play a significant role in forming SASO, spreading the Black Consciousness philosophy, and running and advising the BPC, among other informal roles. His charismatic personality drew people to him. His death at the hands of the South African security police thus had significant repercussions for the Black Consciousness movement and made him a famous martyr.

Born at Tarkastad on December 18, 1946 , to Mzingaye and Alice Duna Biko, Biko grew up in Ginsberg (a small township of King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape). Biko’s father was a policeman (studying for a law degree by correspondence) until he died of an illness in 1950 . Biko’s mother subsequently supported her four children—Bukelwa, Khaya, Bantu, and Nobandile—by working as a domestic maid, then a cook at Grey Hospital in King William’s Town. Biko’s mother was a committed Christian and was often remembered for the way she helped people in need in the township or people in transit at the train station nearby. This kind of community involvement and devotion influenced each of her children in their chosen professions later in life.

The Ginsberg community was a small but racially and economically diverse and vibrant community in the 1950s and 1960s. Biko lived with Coloured neighbors, and Ginsberg’s Weir Hall hosted a number of musical events. There were also a number of sports clubs. Although the community had politically involved people, Biko himself was not interested in politics as a young boy. His siblings, friends, and classmates remember him as being a highly capable student but one who was very playful and sociable. His academic achievements won him support from his community, which organized a bursary for him to join his older brother at the Lovedale Institution to finish high school when he was sixteen years old. His brother’s political activities with the Pan Africanist Congress led to his detention and then expulsion from Lovedale in 1963 . This experience politicized Biko. He resented the abuse of authority by the police, especially as he thought about his brother’s experience. His schooling had also been interrupted, leaving him at home to think while his peers busied themselves with school work. In 1964 , he continued his schooling at St. Francis College, a Roman Catholic school in Mariannhill in the then Natal province. There he further distinguished himself as an outstanding student and questioned authorities and their Christian beliefs. He also held stimulating intellectual debates about African independence with other students.

Biko’s scholastic achievements won him a spot at the UNB medical school, the only place where black people could study medicine during apartheid. There Steve interacted with black people of various backgrounds and began to play a role in student politics at the university. He joined NUSAS and also interacted with the UCM. It is through these student networks that he began working with other students such as Pityana to start SASO. He traveled around the country with Pityana and others to persuade students at black colleges and universities to join SASO and to explain the Black Consciousness philosophy. He served as SASO’s first president. His room at the medical school residency served as the SASO office. After one year in office, SASO elected Pityana as president and Biko took the role of publications officer. Using the pseudonym Frank Talk, he instituted a series in SASO’s newsletter entitled, “I Write What I Like,” where he tackled a number of issues and explained Black Consciousness. Former friends and activists remember Biko as one who enabled others, rather than seeking leadership roles. He also continued to find joy in his associations with people—of all racial backgrounds—mixing intellectual and political conversations with his socializing. He was known for his demanding work ethic as well as his ability to hold his drink.

During his time in Durban he met and married a nursing student, Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba, with whom he had two sons, Nkosinathi (b. 1971 ) and Samora (b. 1975 ). Biko loved his family and spending time with his children; however, he did not put boundaries on his romantic and sexual relationships with women. It was also during his time in Durban that Biko met and worked with Ramphele, with whom he had a long-standing affair. He and Ramphele had a daughter, Lerato (who lived for two months in 1974 ), and a son, Hlumelo (b. 1978 ). Biko had affairs with a number of other women as well. One, Lorrain Tabane, gave birth to Biko’s daughter Motlatsi (b. 1977 ). Although their student days were marked by parties with women and drinking, a number of Biko’s friends later confronted him about his womanizing, as did his wife and Ramphele. Yet Biko seems to have been unwilling or unable to resolve the controversies and pain he caused through this behavior before his death. While he worked well with many women as colleagues and fellow activists, he at times struggled to concede that traditional gender roles could change. 13

In 1972 , Biko was expelled from medical school and left to find a way to support his young son and wife (who was also fired because of her husband’s political involvement). This led to his employment by Khoapa as a field officer for the BCP, his only official employment ever. In Durban, he worked on coordinating among various black organizations and on producing the Black Review . In 1973 , his banning sent him back to Ginsberg. This changed his work and the direction of the BCP. He set up an Eastern Cape branch of the BCP in King William’s Town, from where he helped establish the Zanempilo clinic, took over the Njwaxa project, ran the BCP office and resource center, continued to assist with publications, and started other bursary and grocery coop programs in Ginsberg. He also continued to be involved politically, despite constant police surveillance and attempts to arrest and detain him, and started studying for a law degree by correspondence. Even when he was further restricted by the government from working officially for the BCP in 1975 , he continued to advise on the projects and political matters. The BPC even elected him as an honorary president in 1977 to give him authority to cultivate unity among the various black political groups in the country at the time. Working against the apartheid security forces was a challenge, especially when Biko felt isolated and watched his fellow activists and friends suffer. But Biko also found ways to circumvent police surveillance and to challenge their authority. He was detained, arrested, and accused several times (though never convicted). He was also called to testify at the SASO-BPC trial, which gave him a public platform to define Black Consciousness and display his debating skills. He also famously befriended Donald Woods, the white East London Daily Dispatch newspaper editor, which gave the movement inroads into the media and other networks.

Biko continued to work on unifying the various black groups even under his banning orders. The last trip he took outside of his restricted banning area led him to Cape Town with fellow activist Peter Jones on August 17, 1977 , to meet with various people including Black Consciousness activists as well as Neville Alexander of the Unity Movement. The meetings never materialized. Fearing negative repercussions if they stayed too long, Jones and Biko turned back the next day. They were stopped at a roadblock just outside of Grahamstown. A problem with opening the trunk of the car they had borrowed made the police suspicious. When the police found out they had detained two leaders of the Black Consciousness movement, they arrested the two and sent them to security police headquarters in Port Elizabeth. Biko and Jones suffered physical torture at the hands of the security police.

On September 6, the police took their physical beatings of Biko too far. Police testimonies indicate that Biko’s refusal to submit to disrespectful treatment led the police to beat him and run him into the wall. Biko collapsed. Instead of providing medical treatment, the police chained him to a gate in a standing position. They only called in a district surgeon the next day. Despite evidence of brain damage, the police kept Biko naked and chained up in his cell until his conditioned worsened. On September, the police loaded Biko naked into the back of a police van and drove him through the night to Pretoria Central Prison for medical care. He was pronounced dead there on September 12, 1977 .

The announcement of Biko’s death sparked an international outcry. At first the government said Biko had died of a hunger strike. However, evidence from a postmortem examination proved that Biko had died of head injuries. An inquest into the death of Biko was held, but no one was convicted. Later evidence showed that the police and the medical professionals involved lied at the inquest about the timing of the care Biko received and the cause of the nature of the physical scuffle that led to Biko’s death. When the case was brought to the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the hearings shed further light on the physical struggle that led to Biko’s death and the medical doctors’ complicity but left members of the Biko family dissatisfied with the police officers’ disclosure. The TRC denied amnesty to all of the police officers involved in the hearings. Biko’s death remains a poignant example of the brutality and dishonesty of government security forces as well as the medical sector during apartheid.

Thousands of people attended Biko’s funeral in King William’s Town. A few weeks later, the government banned all Black Consciousness–related organizations including SASO, the BCP, the BPC, and other sympathetic organizations, newspapers, and individuals. Because of Biko’s role in the Black Consciousness movement and the nature of his death, he became the movement’s main martyr. This has influenced the way in which he has been celebrated and remembered. Biko is often placed at the center of histories of the Black Consciousness movement. He was one of the first liberation movement heroes to be memorialized in the post-apartheid era with a statue, his gravesite, and his home being dedicated in 1997 , the 20th anniversary of his death. Soon afterwards, his widow and oldest son, Nkosinathi, formed the Steve Biko Foundation, which contributes to the celebration and shaping of Biko’s character. Yet many have claimed Biko as a progenitor or hero. Community members, people involved in the projects he ran, his friends and colleagues, political parties, and public intellectuals look to Biko. Almost all remember his good characteristics (although his peers are more willing to recognize his faults). He is particularly seen as someone who sacrificed for the nation when in the post-apartheid period leaders from liberation movements are charged with corruption and self-serving politics. He has also been elevated as a leading intellectual and political activist, someone who spoke out boldly and affirmed black dignity. For some, he stands as a revolutionary, while others see him as entrenched in community work.

Post-1977 Black Consciousness Directions

The apartheid state dealt a heavy blow to the Black Consciousness movement after Biko’s death when it declared all Black Consciousness–related organizations illegal. However, activists regrouped in various ways to continue their work. As Mbulelo Mzamane, Bavusile Maaba, and Nkosinathi Biko wrote, different views about the end goal of Black Consciousness manifested themselves in the directions activists took after 1977 . 14 Some continued with community development projects as a practical way of advancing the material position of black people while also improving black self-perceptions. For example, Malusi and Thoko Mpumlwana started the Zingisa Education Fund in the place of the Ginsberg Education Fund and later established the Trust for Christian Outreach and Education (an umbrella for other community development organizations). Ramphele established the Ithuseng Community Health Centre in Tzaneen, where she had been banned, based on the Zanempilo Community Health Centre model.

On the other hand, disagreements already stirring in the movement surfaced about what kind of action would move South Africa closer to freedom and the validity of an analysis that saw economic class as the main cause of inequality. Those advocating a more direct confrontation with the state had already begun to join armed organizations outside the country. Other activists still in the country saw an above-ground political organization as the best way to embody Black Consciousness and affect change. In 1978 , a group of activists met in Roodepoort to form the Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), designed to defy state repression and carry on the work of the BPC. While AZAPO sought to address various aspects of the black experience, it soon adhered to a more socialist interpretation and approach, even emphasizing workers’ concerns. Black Consciousness leadership in Ginsberg had previously highlighted the importance of changing unequal economic structures that disadvantaged the black majority and activists had begun exploring the idea of “black communalism,” but AZAPO now adopted a more explicit class analysis, which it called “scientific socialism.” Activists in AZAPO saw Black Consciousness’s focus on black self-reliance as making it a distinctively different organization, in opposition to other socialist-leaning organizations like the ANC and its supporters. This resulted at times in physically violent clashes. (The PAC and AZAPO have also clashed at times. 15 ) Activists in exile formed the Black Consciousness Movement of Azania (BCMA) as a sort of wing to AZAPO that operated in the 1980s.

Other activists took their conscientized outlook with them as they joined various existing organizations such as the ANC and the PAC. For them, Black Consciousness was an “attitude of mind” and “way of life” that black people needed to adopt, no matter what political organization they belonged to. Some activists in exile, for instance, who had been part of the BCMA eventually decided an additional organization was unnecessary and joined other organizations.

Different interpretations of Black Consciousness and various activists have persisted as people ask what it means to be free in a post-apartheid South Africa. AZAPO is still a political party, although a minor one (and it too has had breakaway factions). Others have written in the same style as Frank Talk. Some have interpreted Black Consciousness simply as promoting black economic and political ascendency or a celebration of black culture (which has translated into clothing lines, for instance). Others look to Black Consciousness for answers about how to uproot residual colonialism. In the early 2000s, younger generations of South Africans, transcending political party boundaries, looked to Black Consciousness as a radical challenge to prevailing racial structures. For example, university student movements in 2015 and 2016 evoked Black Consciousness when critiquing university curriculum and claiming a voice as youth. Some of these students saw a lack of black pride and economic inequality in South Africa as evidence of continued black oppression. Thus, black South Africans continue to evoke Black Consciousness.

Discussion of the Literature

Many scholars and writers have been inspired by Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness movement. This has resulted in a relatively large body of scholarship with authors primarily from South Africa and the United States taking perspectives ranging from the biographical and commemorative, political science, philosophy, history, and literary and visual arts. The amount of scholarship along with various news articles, commentaries, and short-run periodicals demonstrates the power of Biko as an icon and shows that people find relevancy in the movement’s ideas and history. Yet, many works reiterate common themes with an emphasis on Biko’s intellectual and political work.

The first authors who wrote about the Black Consciousness movement in the 1970s and 1980s included sympathetic political scientists and those seeking to commemorate Biko. A collection of Biko’s own writings was published along with a memoir by Biko’s friend, Father Aelred Stubbs, in 1978 , soon after Biko’s death. Various editions of this collection, entitled I Write What I Like , have appeared many times since. Three other books published at the same time similarly sought to publicize Biko’s ideas and expose the brutality of the apartheid regime, including Donald Woods’s Biko . 16 In a more scholarly vein, political scientists Gail Gerhart, Robert Fatton Jr., and CRD Halisi situated Black Consciousness in relation to other black political ideologies to discuss its ideas on race and citizenship. 17

The 1990s saw further commemoration of Biko, but a greater analysis of the Black Consciousness movement. Bounds of Possibility , a volume edited by Biko’s former colleagues and activists, included a brief biography of Biko and commemorative essays as well as various examinations of different aspects of the movement. Even though it perpetuated the focus on Biko, it broadened the analysis of the movement to touch on theology, cultural production, community engagement, and gender. Saleem Badat and Thomas Karis and Gerhart’s work in the late 1990s presaged greater historical analysis and summary of the movement found in subsequent works. 18 For example, in 2006 , Mbulelo Mzamane, Bavusile Maaba, and Nkosinathi Biko’s chapter in The Road to Democracy in South Africa , vol. 2, gave the most comprehensive summary of the movement to that date, and Bhekizizwe Peterson’s chapter in the same volume focused on Black Consciousness literary and other cultural work. 19 Former activists, friends, and politicians continued to add their personal reflections in monographs and edited collections, particularly at anniversaries of Biko’s death. 20 Biographies and edited collections in the early 2000s dealt with Black Consciousness’s philosophical, intellectual, and cultural production. This came as people questioned what it meant to be black and liberated in a post-apartheid, globalized world. For example, Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander, and Nigel Gibson’s Biko Lives! began with a substantial section entitled “Philosophical Dialogues,” and Nigel Gibson and Lewis R Gordon have focused on Black Consciousness’s relation to Fanon and existential thought, respectively. 21

More historical analyses were published as the 1970s became more distant. These works explored the origins, contexts, and impact of the 1970s movement. Daniel R. Magaziner published the first historical monograph of Black Consciousness. His The Law and the Prophets examined the movement’s intellectual history in the context of its time. Leslie Anne Hadfield provided an in-depth analysis of the movement’s extensive community development work in Liberation and Development . 22 Other scholars have emphasized Biko’s longer intellectual heritage, manifested in the museum exhibit at the Steve Biko Centre in Ginsberg, and in Xolela Mangcu’s biography of Biko. 23 These, along with other works published at the same time, notably dealt with questions about the place of women and youth in the movement. 24

Scholars of other disciplines such as art history and theology have continued to explore various parts of the movement and Biko’s impact in depth. 25 Updated collections of Biko’s writings continue to be published. Repeated references to Black Consciousness in South African politics and the growth in scholarly work about the movement indicates that new questions will draw out different aspects of the history of Black Consciousness and Biko in the future. 26 However, many works continue to commemorate Biko and the intellectual aspects of the movement at the expense of greater coverage, complexity, and historical sensitivity. This also has the effect of confining analyses to the Black Consciousness movement of the 1970s, with Biko’s death in 1977 seen as the close of that era. More work on the various actors and broader reach of the movement, including a focus on different regional experiences and contemporary adaptations of Black Consciousness, could prove to be enlightening and productive avenues for further research.

Primary Sources

In relation to the beginnings of Black Consciousness with SASO, there is a relative abundance of published primary sources and sources accessible online. These include Biko’s writings, literary and organizational publications, memoirs and interviews published in edited volumes. On the other hand, many written records from the time when state repression and police harassment increased have been lost or destroyed. Furthermore, after 1977 , the movement was more diffused, resulting in a less cohesive archive for this time period. The written record thus poses challenges for reconstructing the history of the Black Consciousness movement and Biko. Historians have turned to various different sources to create a fuller picture of the movement. Most notably, they have conducted numerous oral histories to fill in the gaps of the written record.

Public Archives

In addition to published primary sources, there are two main archival repositories in South Africa that hold substantial collections on Biko and the Black Consciousness movement, both written and oral sources. The Steve Biko Foundation has created an archive, now housed at the Steve Biko Centre in Ginsberg. This collection brings together sources from major public and personal archives concerning Biko, Black Consciousness, Black community programs of the 1970s, and many of Biko’s contemporaries. It includes copies of the South African Department of Justice files related to Steve Biko and Black Consciousness activists, copies from papers at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Bruce Haigh Special Collection, documents pertaining to the TRC Amnesty Application by the killers of Steve Biko, cuttings from the Daily Dispatch 1972 to 2003 , master’s and doctoral theses, and the collections of scholars such as Magaziner and Hadfield (including the transcripts of the oral histories they conducted).

The Historical Papers division of the William Cullen Library at the University of Witwatersrand has an extensive collection of material related to human and civil rights in South Africa. It has accessions with materials on: Steve Biko; SASO; AZAPO and the Azanian Student’s Organization; the Black People’s Convention; the SASO-BPC trial; and the research materials of Thomas Karis and Gail M. Gerhart used to write From Protest to Challenge (also available on microfilm at the Center for Research Libraries in Chicago). It also holds several valuable accessions on related organizations, such as the papers of the Christian Institute and the South African Council of Churches and their joint program, Spro-cas, the parent organization of the BCP and the papers of the University Christian Movement, and NUSAS. Some of these materials have been digitized and can be accessed online through the archive’s website.

Two other archives hold important materials. The Unisa Documentation Centre for African Studies at the University of South Africa main library in Pretoria has organizational brochures and documents related to the BCP, BPC, and SASO that are not found elsewhere, along with other miscellaneous Black Consciousness papers. For research on AZAPO and the BCMA, the National Heritage and Cultural Studies Centre (NAHECS) at the University of Fort Hare has the most extensive collection in their accession on the Azanian People’s Organization/Black Consciousness Movement (AZAPO/BCM).

Digital and Filmed Collections

Primary sources may also be found in online collections: Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA) digital library has copies of Black Consciousness publications such as the SASO Newsletter and Black Review ; the Aluka digital library’s Struggles for Freedom in Southern Africa Collection includes a sampling of interviews and documents from Gerhart Interviews, Karis-Gerhart Collection, Magaziner Interviews, and NUSAS (but Aluka requires a subscription to access those materials); the Google Arts and Culture online exhibits includes a series on Biko with photographs and some documents. The South African History Online website includes a number of pages on Steve Biko, the Black Consciousness Movement, SASO, the BPC and SASO trial, and various activists with a sampling of primary documents linked to some of the pages. The Overcoming Apartheid website includes a multimedia resource page on the Black Consciousness movement with interviews from various activists. And finally, “The Black Consciousness Movement of South Africa—Material from the collection of Gail Gerhart,” filmed for the Cooperative Africana Microform Project (CAMP) is available on microfilm at the Center for Research Libraries in Chicago, Illinois.

Links to Digital Materials

Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA) .

Google Arts and Culture Institute: Steve Biko .

Overcoming Apartheid .

South African History Online .

Further Reading

- Badat, Saleem . Black Man, You Are on Your Own . Braamfontein, South Africa: Steve Biko Foundation, 2009.

- Biko, Steve . I Write What I Like . Randburg, South Africa: Ravan Press, 1996.

- Hadfield, Leslie Anne . Liberation and Development: Black Consciousness Community Programs in South Africa . East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2016.

- Hook, Derek . Steve Biko: Voices of Liberation . Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014.

- Karis, Thomas , and Gail M. Gerhart . From Protest to Challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882–1990 . Vol. 5, Nadir and Resurgence, 1964–1979 . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

- M-Afrika, Andile . The Eyes That Lit Our Lives: A Tribute to Steve Biko . King William’s Town, South Africa: Eyeball Publishers, 2010.

- Magaziner, Daniel R. The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977 . Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010.

- Mangcu, Xolela . Biko: A Biography . Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2012.

- Mngxitama, Andile , Amanda Alexander , and Nigel Gibson , eds. Biko Lives!: Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Mzamane, Mbulelo V. , Bavusile Maaba , and Nkosinathi Biko . “The Black Consciousness Movement.” In The Road to Democracy in South Africa . Vol. 2, 99–159. Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2006.

- Pityana, Barney , Mamphela Ramphele , Malusi Mpumlwana , and Lindy Wilson , eds. Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness . Cape Town: David Philip, 1991.

- Ramphele, Mamphela . Mamphela Ramphele: A Life . Cape Town: David Philip, 1995.

- Ramphele, Mamphela . Across Boundaries: The Journey of a South African Woman Leader . New York: Feminist Press, 1996.

- Wilson, Lindy . Steve Biko . Auckland Park, South Africa: Jacana Media, 2011.

- Woods, Donald . Biko . 3d ed. New York: Henry Holt, 1991.

1. Daniel R. Magaziner , The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010), 41.

2. Steve Biko , I Write What I Like (Randburg, South Africa: Ravan Press, 1996), 68.

3. Biko, I Write , 29.

4. Mbulelo V. Mzamane , “The Impact of Black Consciousness on Culture,” in Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness , ed. Pityana et al. (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 179–193; Pumla Gqola , “Black Woman, You Are on Your Own: Images of Black Women in Staffrider Short Stories, 1978–1982” (MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1999); Andile Mngxitama , Amanda Alexander , and Nigel Gibson , eds., Biko Lives!: Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008); Bhekizizwe Peterson , “Culture, Resistance and Representation,” in The Road to Democracy in South Africa , vol. 2 (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2006), 161–185; Matthew P. Keaney , “‘I Can Feel My Grin Turn to a Grimace’: From the Sophiatown Shebeens to the Streets of Soweto on the Pages of Drum , The Classic , New Classic , and Staffrider ” (MA thesis, George Mason University, 2010).

5. Mzamane, “The Impact of Black Consciousness on Culture.”

6. In doing so, the movement reclaimed Christianity as a religion promoting liberation, a righteous cause with an assured victory. See Magaziner, The Law and the Prophets , 11 and Part 2; Dwight Hopkins , “Steve Biko, Black Consciousness and Black Theology,” in Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness , ed. Pityana et al. (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 194–200.

7. Philippe Denis , “Seminary Networks and Black Consciousness in South Africa in the 1970s,” South African Historical Journal 62.1 (2010): 162–182; Ian Macqueen , “Students, Apartheid and the Ecumenical Movement in South Africa, 1960–1975,” Journal of Southern African Studies 39.2 (2013): 447–463.

8. Leslie Anne Hadfield , Liberation and Development: Black Consciousness Community Programs in South Africa (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2016).

9. Mbulelo V. Mzamane , Bavusile Maaba , and Nkosinathi Biko , “The Black Consciousness Movement,” in The Road to Democracy in South Africa , vol. 2 (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2006), 141; Sipho Buthelezi “The Emergence of Black Consciousness: An Historical Appraisal,” in Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness , ed. Pityana et al. (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 111–129.

10. For more on the Soweto Uprisings, see Sifiso Ndlovu , “The Soweto Uprising,” in The Road to Democracy in South Africa , vol. 2 (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2006), 317–350.

11. Magaziner, The Law and the Prophets , chap. 9.

12. Julian Brown , “An Experiment in Confrontation: The Pro-Frelimo Rallies of 1974,” Journal of Southern African Studies 38.1 (2012): 55–71.

13. Wilson, “A Life,” 37–41, 60; Xolela Mangcu , Biko: A Biography (Cape Town: Tafelburg, 2012), 204–212.

14. Mzamane, Maaba, Biko, “The Black Consciousness Movement,” 157.

15. Mngxitama, Alexander, and Gibson, Biko Lives! , 7; Nurina Ally and Shireen Ally , “Critical Intellectualism: The Role of Black Consciousness in Reconfiguring the Race-Class Problematic in South Africa,” in Biko Lives!: Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko , eds. Andile Mngxitama , Amanda Alexander , and Nigel Gibson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 171–188; Nigel Gibson , “Black Consciousness after Biko: The Dialectics of Liberation in South Africa, 1977–1987” in Biko Lives!: Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko , eds. Andile Mngxitama , Amanda Alexander , and Nigel Gibson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 138.

16. Donald Woods , Biko (New York: Paddington Press, 1978); Millard Arnold , The Testimony of Steve Biko (London: M. Temple Smith, 1979); Hilda Bernstein , No. 46—Steve Biko (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1978).

17. Gail M. Gerhart , Black Power in South Africa: The Evolution of an Ideology (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California, 1978); Robert Fatton Jr. , Black Consciousness in South Africa: The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White Supremacy (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986); C. R. D. Halisi , Black Political Thought in the Making of South African Democracy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999). Sam Nolutshungu’s Changing South Africa: Political Considerations (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982) also falls in this category, as does Craig Charney , “Civil Society vs. the State: Identity, Institutions, and the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2000). Both analyzed the relationship of the movement to political change.

18. Saleem Badat , Black Student Politics, Higher Education and Apartheid: From SASO to SANSCO, 1968–1990 (Pretoria: Human Science Research Council, 1999); Thomas Karis and Gail M. Gerhart , From Protest to Challenge , vol. 5, Nadir and Resurgence, 1964–1979 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997).

19. Mzamane, Maaba, and Biko, “The Black Consciousness Movement”; Peterson, “Culture, Resistance and Representation.”

20. Mosibudi Mangena , On Your Own: Evolution of Black Consciousness in South Africa/Azania (Braamfontein, South Africa: Skotaville, 1989); Themba Sono , Reflections on the Origin of Black Consciousness in South Africa (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 1993); Mamphela Ramphele , Across Boundaries: The Journey of a South African Woman Leader (New York: Feminist Press, 1996), also published as Mamphela Ramphele: A Life (Cape Town: David Philip, 1995); Chris van Wyk , ed., We Write What We Like: Celebrating Steve Biko (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2007); Andile M-Afrika , The Eyes that Lit Our Lives: A Tribute to Steve Biko (King William’s Town, South Africa: Eyeball Publishers, 2010); Andile M-Afrika , Touched by Biko (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2016).

21. Mngxitama, Alexander, and Gibson, Biko Lives! ; Nigel Gibson , Fanonian Practices in South Africa: From Steve Biko to Abahlali baseMjondolo (Scottsville, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal and Palgrave, 2011); Lewis R. Gordon , Existentia Africana: Understanding Africana Existential Thought (New York: Routledge, 2000).

22. Magaziner, The Law and the Prophets ; Leslie Anne Hadfield, Liberation and Development . Vanessa Noble dealt with the history of SASO students at the University of Natal Medical School in A School of Struggle: Durban’s Medical School and the Education of Black Doctors in South Africa (Scottsville, South Africa: UKZN Press, 2013).

23. Mangcu, Biko .

24. Mamphela Ramphele , “The Dynamics of Gender Within Black Consciousness Organisations: A Personal View,” in Bounds of Possibility , ed. Pityana et al. (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 214–227; Pumla Gqola , “Contradictory Locations: Blackwomen and the Discourse of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) in South Africa,” Meridians 2.1 (2001): 130–152; Daniel Magaziner , “Pieces of a (Wo)man: Feminism, Gender, and Adulthood in Black Consciousness, 1968–1977,” Journal of Southern African Studies 37.1 (2011): 45–61; Leslie Hadfield , “Challenging the Status Quo: Young Women and Men in Black Consciousness Community Work, 1970s South Africa,” Journal of African History 54.2 (July 2013), 247–267.

25. Shannen Hill , Biko’s Ghost: The Iconography of Black Consciousness (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); D. W. Du Toit , ed., The Legacy of Steve Bantu Biko: Theological Challenges (Pretoria: Research Institute for Theology and Religion, 2008).

26. Historical articles doing so include Ian Macqueen , “Resonances of Youth and Tensions of Race: Liberal Student Politics, White Radicals and Black Consciousness, 1968–1973,” South African Historical Journal 65.3 (2013): 365–382; Julian Brown , “SASO’s Reluctant Embrace of Public Forms of Protest, 1968–1972,” South African Historical Journal 62.4 (2010): 716–734; Anne Heffernan , “Black Consciousness’s Lost Leader: Abraham Tiro, the University of the North, and the Seeds of South Africa’s Student Movement in the 1970s,” Journal of Southern African Studies 41.1 (2015): 173–186. See also Jesse Walter Bucher , “Arguing Biko: Evidence of the body in the politics of history, 1977 to the Present” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota 2010).

Related Articles

- Slavery at the Cape

- Communism in South Africa

- The Sudanese Communist Movement

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, African History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 04 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Steve Biko: The Black Consciousness Movement

The saso, bcp & bpc years.

By Steve Biko Foundation

Stephen Bantu Biko was an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. A student leader, he later founded the Black Consciousness Movement which would empower and mobilize much of the urban black population. Since his death in police custody, he has been called a martyr of the anti-apartheid movement. While living, his writings and activism attempted to empower black people, and he was famous for his slogan “black is beautiful”, which he described as meaning: “man, you are okay as you are, begin to look upon yourself as a human being”. Scroll on to learn more about this iconic figure and his pivotal role in the Black Consciousness Movement...

“Black Consciousness is an attitude of mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time” - Biko

1666/67 University of Natal SRC

On completion of his matric at St Francis College, Biko registered for a medical degree at the University of Natal’s Black Section. The University of Natal professed liberalism and was home to some of the leading intellectuals of that tradition. The University of Natal had also become a magnet attracting a number of former black educators, some of the most academically capable members of black society, who had been removed from black colleges by the University Act of 1959. The University of Natal also attracted as law and medical students some of the brightest men and women from various parts of the country and from various political traditions. Their convergence at the University of Natal in the 1960s turned the University into a veritable intellectual hub, characterised by a diverse culture of vibrant political discourse. The University thus became the mainstay of what came to be known as the Durban Moment.

At Natal Biko hit the ground running. He was immediately influenced by, and in turn, influenced this dynamic environment. He was elected to serve on the Student's Representative Council (SRC) of 1966/67, in the year of his admission. Although he initially supported multiracial student groupings, principally the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a number of voices on campus were radically opposed to NUSAS, through which black students had tried for years to have their voices heard but to no avail. This kind of frustration with white liberalism was not altogether unknown to Steve Biko, who had experienced similar disappointment at Lovedale.

Medical Students at the University of Natal (Left to Right: Brigette Savage, Rogers Ragavan, Ben Ngubane, Steve Biko)

Correspondence designating Biko as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS Conference

In 1967, Biko participated as an SRC delegate at the annual NUSAS conference held at Rhodes University. A dispute arose at the conference when the host institution prohibited racially mixed accommodation in obedience to the Group Areas Act, one of the laws under apartheid that NUSAS professed to abhor but would not oppose. Instead NUSAS opted to drive on both sides of the road: it condemned Rhodes University officials while cautioning black delegates to act within the limits of the law. For Biko this was another defining moment that struck a raw nerve in him.

Speech by Dr. Saleem Badat, author of Black Man You Are on Your Own, on SASO

Reacting angrily, Biko slated the artificial integration of student politics and rejected liberalism as empty echoes by people who were not committed to rattling the status quo but who skilfully extracted what best suited them “from the exclusive pool of white privileges”. This gave rise to what became known as the Best-able debate: Were white liberals the people best able to define the tempo and texture of black resistance? This debate had a double thrust. On the one hand, it was aimed at disabusing white society of its superiority complex and challenged the liberal establishment to rethink its presumed role as the mouthpiece of the oppressed. On the other, it was designed as an equally frank critique of black society, targeting its passivity that cast blacks in the role of “spectators” in the course of history. The 7th April 1960 saw the banning of the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress and the imprisonment of the leadership of the liberation movement had created a culture of apathy

Bantu Stephen Biko

“ We have set out on a quest for true humanity, and somewhere on the distant horizon we can see the glittering prize. Let us march forth with courage and determination, drawing strength from our common plight and our brotherhood. In time we shall be in a position to bestow upon South Africa the greatest gift possible - a more human face.”

Biko argued that true liberation was possible only when black people were, themselves, agents of change. In his view, this agency was a function of a new identity and consciousness, which was devoid of the inferiority complex that plagued black society. Only when white and black societies addressed issues of race openly would there be some hope for genuine integration and non-racialism.

Transcript of a 1972 Interview with Biko

At the University Christian Movement (UCM) meeting at Stutterheim in 1968, Biko made further inroads into black student politics by targeting key individuals and harnessing support for an exclusively black movement. In 1969, at the University of the North near Pietersburg, and with students of the University of Natal playing a leading role, African students launched a blacks-only student organisation, the South African Student Organisation (SASO). SASO committed itself to the philosophy of black consciousness. Biko was elected president.

Black Student Manifesto

The idea that blacks could define and organise themselves and determine their own destiny through a new political and cultural identity rooted in black consciousness swept through most black campuses, among those who had experienced the frustrations of years of deference to whites. In a short time, SASO became closely identified with 'Black Power' and African humanism and was reinforced by ideas emanating from Diasporan Africa. Successes elsewhere on the continent, which saw a number of countries, achieve independence from their colonial masters also fed into the language of black consciousness.

SASO's Definition of Black Consciousness

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

“ In 1968 we started forming what is now called SASO... which was firmly based on Black Consciousness, the essence of which was for the black man to elevate his own position by positively looking at those value systems that make him distinctively a man in society” - Biko

Cover of a 1971 SASO Newsletter

Cover of a 1972 SASO Newsletter

Cover of SASO newsletter, 1973

Cover of a 1975 SASO Newsletter

Steve Biko speaks on BCM

The Black People’s Convention By 1971, the influence of SASO had spread well beyond tertiary education campuses. A growing body of people who were part of SASO were also exiting the university system and needed a political home. SASO leaders moved for the establishment of a new wing of their organisation that would embrace broader civil society. The Black People’s Convention (BPC) with just such an aim was launched in 1972. The BPC immediately addressed the problems of black workers, whose unions were not yet recognised by the law. This invariably set the new organisation on a collision path with the security forces. By the end of the year, however, forty-one branches were said to exist. Black church leaders, artists, organised labour and others were becoming increasingly politicised and, despite the banning in 1973 of some of the leading figures in the movement, black consciousness exponents became most outspoken, courageous and provocative in their defiance of white supremacy.

BPC Membership Card

Minutes of the first meeting of the Black People's Convention

In 1974 nine leaders of SASO and BPC were charged with fomenting unrest. The accused used the seventeen-month trial as a platform to state the case of black consciousness in a trial that became known as the Trial of Ideas. They were found guilty and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, although acquitted on the main charge of being party to a revolutionary conspiracy.

SASO/BPC Trial Coverage SASO/BPC Trial Coverage BPC Members

SASO/BPC Coverage

Poster from the 1974 Viva Frelimo Rally

Their conviction simply strengthened the black consciousness movement. Growing influence led to the formation of the South African Students Movement (SASM), which targeted and organised at high school level. SASM was to play a pivotal role in the student uprisings of 1976.

Barney Pityana, Founding SASO Member

In 1972, the year of the birth of the BPC, Biko was expelled from medical school. His political activities had taken a toll on his studies. More importantly, however, according to his friend and comrade Barney Pityana, “his own expansive search for knowledge had gone well beyond the field of medicine.” Biko would later go on to study law through the University of South Africa.

Steve Biko's Order Form for Law Textbooks

Upon leaving university, Biko joined the Durban offices of the Black Community Programmes (BCP), the developmental wing of the Black People Convention, as an employee reporting to Ben Khoapa. The Black Community Programmes engaged in a number of community-based projects and published a yearly called Black Review, which provided an analysis of political trends in the country.

Black Community Programmes Pamphlet

Overview of the BCP

BCP Head, Ben Khoapa

86 Beatrice Street, Former Headquarters of the BCP

"To understand me correctly you have to say that there were no fears expressed" - Biko

Ben Khoapa, Beatrice Street Circa 2007

Biko's Banning Order

When Biko was banned in March 1973, along with Khoapa, Pityana and others, he was deported from Durban to his home town, King William’s Town. Many of the other leaders of SASO, BPC, and BCP were relocated to disparate and isolated locations. Apart from assaulting the capacity of the organisations to function, the bannings were also intended to break the spirit of individual leaders, many of whom would be rendered inactive by the accompanying banning restrictions and thus waste away.

Following his banning, Biko targeted local organic intellectuals whom he engaged with as much vigour as he had engaged the more academic intellectuals at the University of Natal. Only this time, the focus was on giving depth to the practical dimension of BC ideas on development, which had been birthed within SASO and the BPC. He set up the King William’s Town office (No 15 Leopold Street) of the Black Community Programmes office where he stood as Branch Executive. The organisation focused on projects in Health, Education, Job Creation and other areas of community development.

No 15 Leopold Street , Former King William's Town Offices of the BCP

It was not long before his banning order was amended to restrict him from any meaningful association with the BCP. Biko could not meet with more that one person at a time. He could not leave the magisterial area of King William’s Town without permission from the police. He could not participate in public functions nor could he be published or quoted.

Zanempilo Clinic, a BPC Clinic