Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

Pros and Cons of Covid-19: A Tale of Two Sides

Feature article.

|

Covid-19 has brought the world to a grinding halt. It has left a trail of tears and uncertainty. On a personal level, our family lost someone we loved dearly. His lonely passing without final goodbyes was tough to endure. Despite this, I continue to tread on the path of realistic optimism and positive resilience. Mind you, I am not a psychologist. I am a cardiologist. I use these terms loosely as I pen my thoughts on "Pros of the Covid-19 story" for the ACC WIC Section. |

COVID-19 has put millions on the edge, and everyone was suddenly placed in a state of emergency. I thought I was resilient: my family is good, sheltered at home and healthy. Having endured a massive earthquake, volcano eruption, typhoons and hurricanes, I thought this will not be as bad. One week passed, then two, three, then eight... my optimism slowly began to fade away as it became harder to stay positive. Here are my thoughts on "Cons of the COVID-19 story." |

| With schools closed, the clock is not running my children's lives anymore. Lack of regimented routine has left room for expressiveness and ingenuity – music production, creating art and exploring online coding. Kids are relishing non-curriculum books without the pressure of time. My children have taken structure into their own hands by self-made daily calendars with study, exercise and game times. It has been uplifting to see this early maturity! Flexibility has allowed time for family movies, board games, help with chores and taking on responsibility in our dual-physician household (helping elderly grandparents or younger siblings). | With the sudden closure of schools, most parents were at a loss and ill-prepared, now forced to homeschool our children. There has been a steep learning curve for the students, teachers and parents on how to navigate the new world of "virtual learning." In most households, women bear most of the responsibility of keeping the house in order. Never has it been more magnified than during this pandemic. Even in most dual-physician households, women carry the brunt of the household work and the logistics of everyday homeschooling, grocery shopping, etc. on top of being on the frontlines. As schools and daycares closed, most health care workers were still expected to report to work. Grandparents who helped with childcare were suddenly out of the equation as we try to limit their exposure. Babysitters were reluctant to come due to the same fear of exposure. Most were then left with the stress of straddling between clinical schedules and childcare/homeschooling. Most health care workers' biggest fear: bringing coronavirus home. I began wearing scrubs and started the new ritual of removing clothes in the laundry room, followed by heading straight to the shower for a thorough "decontamination." Worried children have been continually reassured that we take precautions so we do not get infected or expose our family. |

| We, as physicians, have shown the world that we are malleable and adaptable. I am proud to see that we have stepped out of our comfort zones to manage ventilators, volunteer in emergency departments and ICUs. We also adapted quickly to fluid policies and schedules as they evolved. Never in medicine have we seen such an extensive exchange of scientific dialogue across fields. Everyone joined hands, with one goal, to alleviate suffering by empowering each other intellectually while fulfilling our duties with empathy. Covid-19 gave us no choice but to enforce social distancing. This opened new avenues for us to continue to provide care for our patients through virtual medicine. Increased efficiency, convenience and minimizing exposure to COVID-19 have been the highlights of telemedicine. The forgotten art of taking a detailed health history, to form a diagnosis, has been refreshed. Relaxation of government regulations for billing have helped to ensure patient care while keeping practices afloat. With limited resources and PPE, we have become experts at reallocation of resources and patient triaging by categorizing procedures as elective, urgent and emergent. We have taken a step back, to question if the procedure or test is really necessary or not. I hope, even after the pandemic, we continue to approach the U.S. health care system with "need driven care," instead of "revenue driven care." The down time has allowed physicians more time for writing, publishing, reading scientific and nonmedical books, as well as pursue hobbies including yoga, exercise, art and music. | Physicians around the world turned to each other on how to best manage a novel virus. What is the clinical course? Spread? Most vulnerable population? Normally, questions like these were answered by random clinical trials or meta-analyses, but in the brink of a pandemic, we now have a disease with no known treatment. All treatments are trial-and-error. CDC changed recommendations almost every other day. For most physicians came this challenge: "Are we trained enough to function in uncertainty?" Physicians were learning as they go, and not being able to offer definitive plans for patients is extremely distressing. The media has used war metaphors to portray the medical community's pandemic fight, in the light of PPE shortage. We were "soldiers going to war unarmed" as we reuse our masks and have inadequate PPE. There were shortages of COVID-19 testing kits, and even health care workers who were exposed could not get tested. Hospitals eventually realized how ill-prepared they were with shortages of ventilators, beds, and personnel. In most states, hospitals were mandated to halt elective procedures and clinic visits during the initial weeks. Balancing benefit vs. risk of any procedure or visit to prevent further health decline had become a stressful day to day task among physicians. By the time this pandemic is over, it has been said that most everyone will know someone who has been infected or died of COVID-19. I have three friends who got infected and recovered, but I also had a medical school classmate and several mentors who died from COVID-19. Yet another crisis is looming as more health care workers suffer from PTSD, depression and anxiety, which has sparked a rise in suicide rates. Due to these deaths, a lot of health care workers have thought about their own mortality and started or updated their wills. As the amount of research on COVID-19 increase exponentially, reports show that women are not as academically productive as our male counterparts. Women's research productivity has taken a backseat, likely due to managing both clinical work and maintaining the household. The pandemic has also catalyzed a rapid economic collapse. Most hospitals were not immune to this financial downturn, as most elective procedures, admissions and clinic visits were halted. Physicians and other health care workers experienced pay cuts and staff were furloughed or laid off. |

| The global suffering has led to introspection – being kind to ourselves and others and encouraging us to build bridges across geographical barriers. We are more sensitive to others' difficulties because we are all in the same boat. Setting up mental health support groups, talking openly about PTSD, stress, making masks and volunteering to help in hot spot areas are some of the kind gestures that sprouted out of this shared suffering. The philosophical side of life is the grounding patch. Humans are not indestructible and life is unpredictable. The pandemic has made these distant statements crystal clear for us. We learned that nature should not be taken for granted. Nobody would have predicted six months ago that the world will grind to a halt at the power of a virus in this day and age when mankind is proud of its conquest over nature. Remaining humble keeps us on our guard without living a reckless life – to not overstep natural boundaries. With the economic pressure, we have learned the value of prudence with finances and savings. "Save for the rainy day" is a timely proverb for these times. Also, it has opened people's hearts to pursue philanthropy. Demographics have highlighted racial and economic disparities in COVID-19 survival and outcomes, giving us yet another reason to be instruments for change towards equality. Sometimes health care policies felt like they did not adequately reflect physician scientific views. The pandemic has reiterated the need for physicians to have a stronger voice in health care policies instead of being silent spectators. The world at large has recognized the selfless service of health care workers during these dire times. While we are not craving for laurels, gratitude kindles the service spirit. | Conspiracy theorists started coming out as quick as this pandemic screaming, "It's all fake!" These "Coronavirus Deniers" think this pandemic is a hoax and have total disregard for social distancing. As most people quarantined at home (and inexplicably hoard toilet paper), these people continue to spread misinformation, angering a lot of health care workers who sacrifice their lives and their family. "Man is by nature a social animal." With the necessary social distancing comes its more nefarious cousin, social isolation. I must admit, I miss my family and friends. I miss traveling and eating out. This necessary, but still unusual, new reality can affect most people and could trigger PTSD, anxiety, fear, substance abuse and loneliness. This pandemic demanded a coordinated nationwide, if not worldwide, approach. With all the uncertainties, the lack of direction and necessary leadership has become more apparent, resulting in increasing deaths and failure to truly "flatten the curve." Seeing how fragile this world has become in the hands of a deadly virus, the world will never be the same even after this vicious enemy retreat. All the deaths, loss of income, economic downfall, global suffering and the uncertain future has left us... lost. |

|

|

Tweet #ACCWIC

You must be logged in to save to your library.

Jacc journals on acc.org.

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Contact Member Care

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- The positive effects...

The positive effects of COVID-19 and the social determinants of health: all in it together?

Rapid response to:

The positive effects of covid-19

Read our latest coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

We welcome Bryn Nelson’s analysis of the potentially positive effects of public and policy responses to COVID-19, particularly in providing an opportunity to reassess priorities. Nelson highlights the unanticipated benefits of recent behaviour changes – but we suggest the real revolution is a re-discovery of the health potential of state intervention. Governments worldwide have taken unprecedented steps to suppress viral spread, strengthen health systems, and prioritise public health concerns over individual and market freedoms, , with reductions in air pollution, road traffic accidents and sexually transmitted infections a direct (if temporary) result of the embrace of collective over individual liberty. Aside from an outbreak of alt-right protests, the usual accusations of ‘nanny state’ interference have been replaced by calls for centralised governance, funding and control on a scale unseen in peacetime.

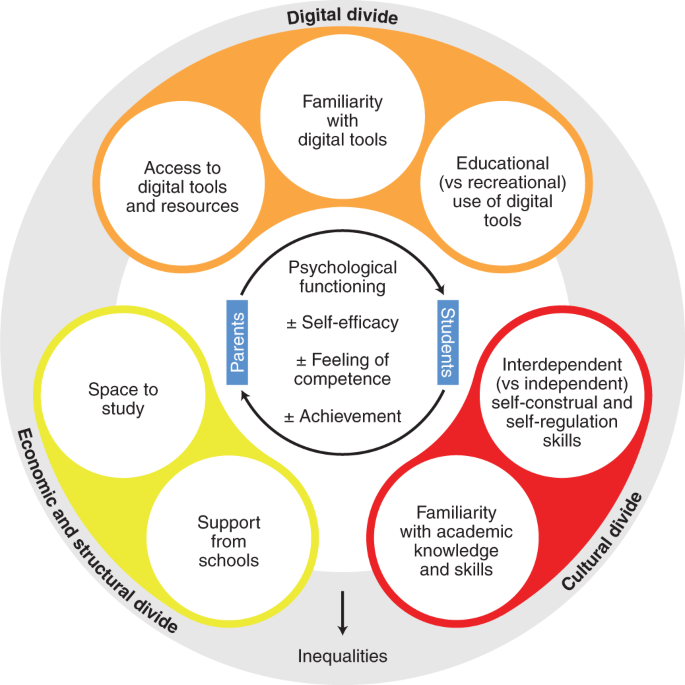

While applauding this paradigm shift, it’s important to acknowledge both its partial nature and its extremely uneven impacts – positive or otherwise. As Nelson notes, negative impacts of the current pandemic (such as unemployment and hunger) are ‘unquestionably troubling’, and while governments proclaim that “we’re all in this together” it’s already clear the virus disproportionately affects the poor, ethnic minorities and other socially disadvantaged groups. , Even more troublingly, the very measures intended to suppress viral spread are themselves exacerbating underlying social inequities. , While a drop in traffic is very welcome, the edict to ‘work from home’ is disastrous for casually-employed service or retail workers; and while social distancing may have reduced viral transmission in some groups, its benefits are less evident for those who are homeless, in overcrowded housing or refugee camps. In maximising the potential for COVID-19 to have positive effects, we must understand and address why its negative effects are so starkly mediated by class, ethnicity and (dis)ability.

Back in 2008, the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health highlighted that population health and its social distribution are driven by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and that social injustice is the biggest killer of all. This insight provokes serious questions about the unequal effects of this pandemic and its associated policy responses, both positive and negative. Like Nelson, we hope the currently crisis will produce valuable lessons – most especially in understanding the need for collective action to create a healthier and more equal society.

There are three critical issues here. First, if governments are serious about “preventing every avoidable death”, COVID response strategies need to take account of their unequal impacts. While many states have acted swiftly to support businesses and wage-earners,4 these interventions are largely blind to class, gender and race. Unemployment and food insecurity have already increased with disproportionate effects on women and low-income workers,13 and growing income inequalities are predicted. Charities report dramatic increases in domestic violence with an estimated doubling in domestic abuse killings since the start of the lockdown. While COVID-19 is already more fatal in Black and minority ethnic groups, we have yet to see the extent to which the response will exacerbate existing racial inequities in employment, income and housing. Governments must recognise – and ameliorate – inequalities in the negative effects of COVID-19.

Second, when developing strategies for transitioning out of lockdown, governments need to take account of the unequal impacts of any changes. The Scottish Government has signalled its intention to ease restrictions in ways that “promote solidarity… promote equality... [and] align with our legal duties to protect human rights”.23 Other governments should also consider how plans for lifting the lockdown can be tailored to minimize harm to already disadvantaged groups, and to ensure equal enjoyment of the associated benefits.

Finally, COVID-19 will produce a truly positive effect if the scale of the mobilisation to counter the pandemic can be matched by a sustained commitment to reducing social, economic and environmental inequalities in the longer term. Without such a commitment, we are perpetuating a situation in which many people live in a state of chronic vulnerability. This is bad for society, not only because it undermines social cohesion and trust, but because it places us all at increased risk. COVID-19 unmasks the illusion that health risk can be localised to the level of the individual, community, or even nation state.

If we’re serious about using this crisis to reassess our priorities, , we need to recognise the urgent need for change beyond individual ‘risky behaviour’. To paraphrase Rudolf Virchow, the promotion of health is a social science, and large-scale benefits come from political – not individual – change. The genuinely positive effects of COVID-19 will come when we acknowledge the centrality of wealth redistribution, public provision and social protection to a resilient, healthy and fair society.12, Only then can governments begin to claim that we’re “all in it together”.

References 1. Nelson B. The positive effects of covid-19. BMJ 2020;369;m1785 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1785 2. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Oxford: Oxford University, Blavatnik School of Government. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/oxford-covid-19-gove... (accessed 25 March 2020) 3. Kickbush I, Leung GM, Bhutta ZA et al. Covid-19: how a virus is turning the world upside down [editorial]. BMJ 2020; 369:m1336 doi:10.1136/bmj.m1336 4. Gostin LO, Gostin KG. A broader liberty: JS Mill, paternalism, and the public’s health. Public Health 2009; 123(3): 214-221 5. BBC News. Coronavirus lockdown protests: What’s behind the US demonstrations? BBC [online], 21 April 2020. URL https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-52359100 6. Calman K. Beyond the ‘nanny state’: Stewardship and public health. Public Health 2009; 123(S): e6-10 7. Economist. Building up the pillars of state [briefing]. The Economist, March 28th 2020. 8. Bell T. Sunak’s plan is economically and morally the right thing to do [opinion]. Financial Times, March 21 2020. URL https://www.ft.com/content/70d45e68-6ab6-11ea-a6ac-9122541af204 9. Office of National Statistics. Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 17 April 2020. Statistical bulletin. London: Office of National Statistics. 10. Van Dorn A, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 2020 395(10232): 1243-4 11. Friel S, Demio S. COVID-19: can we stop it being this generation’s Great Depression? 14 April 2020. Insightplus, Medical Journal of Australia. URL https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2020/14/covid-19-can-we-stop-it-being-thi... 12. Banks J, Karjalainen H, Propper C, Stoye G, Zaranko B (2020). Recessions and health: The long-term health consequences of responses to coronavirus. IFS Briefing Note BN281. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14799 13. Sainato M. Lack of paid leave will leave millions of US workers vulnerable to coronavirus. Guardian [online], 9 March 2020. URL https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/09/lack-paid-sick-leave-will-... 14. Eley A. Coronavirus: The rough sleepers who can’t self-isolate. BBC [online], 22 March 2020. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. URL https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51950920 15. Lancet. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020 395(10230): 1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736 (20)30757-1 16. Hargreaves S, Kumar BN, McKee M, Jones L, Veizis A. Europe’s migrant containment policies threaten the response to covid-19 [editorial]. BMJ 2020; 368 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1213 17. WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. 18. Joyce R, Xu X (2020). Sector shutdowns during the coronavirus crisis: which workers are most exposed? IFS Briefing Note BN278. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14791 19. Scottish Government. COVID-19 – A Framework for Decision Making. April 2020 Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2020. URL https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-framework-decisio... 20. The Poverty Alliance. National organisations & the impact of Covid-19: Poverty Alliance briefing, 22nd April 2020. Edinburgh: The Poverty Alliance. URL https://www.povertyalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Covid-19-and-... 21. Crawford R, Davenport A, Joyce R, Levell P (2020). Household spending and coronavirus. IFS Briefing Note BN279. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14795 22. Townsend M. Revealed: surge in domestic violence during Covid-19 crisis. The Guardian [online], 12 April 2020. URL https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/12/domestic-violence-surges... 23. Grierson J. Domestic abuse killings ‘more than double’ amid Covid-19 lockdown. Guardian [online], 15 April 2020. URL https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/15/domestic-abuse-killings-... 24. Barr C, Kommenda N, McIntyre N, Voce Antonio. Ethnic minorities dying of Covid-19 at higher rate, analysis shows. Guardian [online], 22 April 2020. URL https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/racial-inequality-in-brita... 25. Haque Z. Coronavirus will increase race inequalities [blog]. 26 March 2020. London: Runnymede Trust. URL https://www.runnymedetrust.org/blog/coronavirus-will-increase-race-inequ... 26. Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The Spirit Level. Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin Books, 2010 27. Woodward A, Kawachi I. Why reduce health inequalities? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2000; 54(12):923-929. 28. Collin J, Lee K (2003). Globalisation and transborder health risk in the UK. London: The Nuffield Trust. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/globalisation-and-transborder-... 29. Mackenbach J. Politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale: reflections on public health’s biggest idea. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009; 63(3): 181-4 doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077032 30. Graham H. Unequal Lives. Health and Socioeconomic Inequalities. Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw Hill, 2007.

Competing interests: No competing interests

Seven positive outcomes of COVID-19

COVID-19 has had undeniable and horrific consequences on people’s lives and the economy. With sickness, death and unemployment rates soaring almost everywhere on our planet, it is easy to despair.

Notwithstanding the gruesomeness of this situation, there are some outcomes that could have a long-term positive impact on the planet and humanity.

1. The Environment

The first positive aspect of COVID-19 is the effect on the environment . Carbon emissions are down globally and with manufacturing and air travel grinding to a halt, the planet has had a chance to rejuvenate.

China recorded an 85 per cent increase in days with good air quality in 337 cities between January and March. With tourists gone from Italy, the long-polluted canals of Venice now appear clear as fish and other wildlife start returning. Elsewhere, wildlife is also reappearing in other major cities and the biodiversity is slowly starting to return in various parts of the world.

The coronavirus is also raising hopes of fewer battles and less conflict, resulting in increased levels of peace. The United Nations called to end all wars in the face of COVID-19 as the world confronts a common enemy: “It’s time to put armed conflict on lockdown,” stated Secretary-General António Guterres.

So many businesses have had to reinvent themselves with a new 'business as unusual' philosophy.

And according to the ABC, a ceasefire was declared by the Saudis fighting Houthi rebels in Yemen. Although there are many places in the Middle East where war persists, a stronger lockdown could lead to less violence in these countries too.

3. Connectedness

A third positive outcome is a rejuvenated sense of community and social cohesion. Self-isolation challenges us as social animals who desire relationships, contact and interaction with other humans.

However, people all around the world are finding new ways to address the need for interconnectedness. In Italy, one of the worst-hit countries, people are joining their instruments and voices to create music from their balconies . People are leading street dance parties while maintaining social distancing.

People are using social media platforms to connect, such as the Facebook group The Kindness Pandemic , with hundreds of daily posts. There is a huge wave of formal and informal volunteering where people use their skills and abilities to help.

4. Innovation

COVID-19 is a major market disruptor that has led to unprecedent levels of innovation. Due to the lockdown, so many businesses have had to reinvent themselves with a new 'business as unusual' philosophy.

This includes cafes turning into takeaway venues (some of which also now sell milk or face masks) and gin distilleries now making hand sanitisers .

Many businesses have had to undergo rapid digitalisation and offer their services online. Some could use this wave of innovation to reimagine their business model and change or grow their market.

5. Corporate Responsibility

Coronavirus is driving a new wave of corporate social responsibility (CSR). The global pandemic has become a litmus test for how seriously companies are taking their CSR and their work with key stakeholders: the community, employees, consumers and the environment.

Home-schooling is becoming the new way of learning, exposing many parents to what their children know and do.

Companies are donating money, food and medical equipment to support people affected by the coronavirus. Others are giving to healthcare workers, including free coffee at McDonald’s Australia and millions of masks from Johnson & Johnson .

Many are supporting their customers, from Woolworths introducing an exclusive shopping hour for seniors and people with disabilities to Optus giving free mobile data so its subscribers can continue to connect.

6. Reimagined Education

The sixth positive outcome is massive transformation in education. True, most of it was not by choice. With schools closing down all around the world, many teachers are digitalising the classroom , offering online education, educational games and tasks and self-led learning.

Silver linings amid the suffering: Professor Debbie Haski-Leventhal believes a new found sense of gratitude for freedoms we take for granted and a global trend in thanking health workers who are at the frontline are among the positives to come out of the crisis.

We are globally involved in one of the largest-scale experiments in changing education at all levels. Home-schooling is becoming the new way of learning, exposing many parents to what their children know and do.

Similarly, universities are leading remote learning and use state-of-the-art solutions to keep students engaged. Some universities are using augmented and virtual reality to provide near real-life experiences for galvanising students’ curiosity, engagement and commitment and for preparing students for the workplace.

7. Gratitude

Finally, the seventh gift that COVID-19 is giving us is a new sense of appreciation and gratefulness . It has offered us a new perspective on everything we have taken for granted for so long – our freedoms, leisure, connections, work, family and friends. We have never questioned how life as we know it could be suddenly taken away from us.

Hopefully, when this crisis is over, we will exhibit new levels of gratitude . We have also learned to value and thank health workers who are at the frontline of this crisis, risking their lives everyday by just showing up to their vital work. This sense of gratefulness can also help us develop our resilience and overcome the crisis in the long-term.

- Will a vaccine really solve our COVID-19 woes?

- How Sydney has coped with pandemics in the past

All of these positive aspects come at a great price of death, sickness and a depressed global economy. As heartbreaking and frightening as this crisis is, its positive outcomes can be gifts we should not overlook. If we ignore them, all of this becomes meaningless.

It will be up to us to change ourselves and our system to continue with the positive environmental impact, peace, connectedness, innovation, corporate responsibility, reimagined education and gratitude. This crisis will end. We will meet again. We can do so as better human beings.

Debbie Haski-Leventhal is a Professor of Management at the Macquarie Business School. She is a TED speaker and the author of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Tools and Theories for Responsible Management and The Purpose-Driven University .

Recommended Reading

Weighing the benefits and costs of COVID-19 restrictions

July 20, 2021 – Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers and the public have often vehemently disagreed about the pros and cons of restrictions such as lockdowns. Proponents of restrictions argue that they save lives; opponents say they destroy livelihoods. Amid these often nasty debates, researchers have been churning out benefit-cost analyses that aim to shed light on which restrictions are “worth it” and which aren’t.

“There are now a huge number of these analyses,” said Lisa Robinson , senior research scientist and deputy director of the Center for Health Decision Science at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “It’s become an enormous undertaking.” For her part, Robinson has been exploring the complexities involved in valuing deaths averted by COVID-19 policies , using a well-established but widely-misunderstood metric called the “value per statistical life,” or VSL.

In the big picture, analyses of COVID-19 policies need to take into account how many lives they could potentially save, of course. But they also need to consider the potential downsides. For instance, how many people could lose their jobs if a state puts a lockdown into effect? What educational losses will occur among kids who miss months of in-person school? If restrictions on restaurants are lifted, how do we weigh the economic benefits against the potential increase in COVID-19 cases—and the deaths that might result?

“What benefit-cost analysis does is require people to carefully and rigorously explore the impacts of a policy,” Robinson said. “Something may sound like a great idea on the surface, but digging more deeply into its real-world effects often unearths unexpected consequences. These analyses also highlight the trade-offs implicit whenever we make a decision about how to allocate resources.”

Assigning a money value to life

Robinson has been exploring how best to estimate the VSL—a metric commonly used to evaluate lifesaving interventions—in analyzing the relative costs and benefits of COVID-19 policies. She tackled the issue in a study she co-authored last year, which a recent article in The Economist characterized as “the best attempt at weighing up these competing valuations.”

Although the phrase “value per statistical life” suggests that the government, or someone else, is somehow placing a value on someone’s life, Robinson emphasizes that this is not the case. Rather, economists start by investigating how much of their own income individuals are willing to exchange to reduce their own chance of dying by a small amount—such as by paying extra to buy a safer car or choosing a less risky job for lower pay. These estimates are then converted into estimates of value of reducing expected deaths—that is to say, into the VSL.

Policymakers often use VSL, for example, when determining what safety requirements to impose on automobiles or how low to set standards for pollution emissions. In looking at the population as a whole, U.S. regulatory agencies making benefit-cost calculations currently estimate the VSL as roughly $10 or $11 million. A $10 million VSL means that a typical individual is willing to pay $1,000 to reduce his or her chance of dying within a given year by 1 in 10,000, Robinson explained in a 2020 blog post that looked at COVID-19 benefit-cost analysis and the VSL.

She noted, however, that the $10 million or $11 million figure is for the average member of the population—for someone middle-aged. An individual’s willingness to pay to reduce mortality risk may not stay the same across their life course. For example, older people have fewer expected years of life remaining than the average member of the population, and less opportunity for future earnings, which could change the VSL calculation and therefore make a difference when COVID-19 policies are assessed.

Yet another consideration to take into account is the value people may place on avoiding the substantial pain and suffering caused by COVID-19—including struggling to breathe, or being put on a ventilator—which could increase the VSL. In an October 2020 paper , Robinson’s colleague and frequent co-author James Hammitt , professor of economics and decision sciences, also noted that people may be more likely to place a higher value on avoiding risks they view as “dreaded, uncertain, catastrophic, and ambiguous”—like COVID-19.

The overall point, according to Robinson, is that analysts and policymakers comparing the benefits and costs of particular COVID-19 policies should take care to examine uncertainty in the VSL estimates. VSL is likely to vary depending on who is affected by the policy and by how they view the risks that they experience.

She acknowledges the difficulty involved in deciding on COVID-19 restrictions. But she is also gratified to see that people are using benefit-cost analysis to carefully explore the implications of those tough decisions.

“When COVID hit, benefit-cost analysis really got a lot of attention in the mass media,” she said. “I was so excited that this field that I’ve been involved in for so long is now the subject of stories in major news outlets like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. People are really paying attention to its usefulness in policymaking.”

– Karen Feldscher

photo: Anthony Quintano/Wikimedia Commons

Jump to navigation

- Bahasa Malaysia

What are the benefits and risks of vaccines for preventing COVID-19?

Key messages

– Most vaccines reduce, or probably reduce, the number of people who get COVID-19 disease and severe COVID-19 disease.

– Many vaccines likely increase number of people experiencing events such as fever or headache compared to placebo (sham vaccine that contains no medicine but looks identical to the vaccine being tested). This is expected because these events are mainly due to the body's response to the vaccine; they are usually mild and short-term.

– Many vaccines have little or no difference in the incidence of serious adverse events compared to placebo.

– There is insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the vaccine and placebo in terms of death because the numbers of deaths were low in the trials.

– Most trials assessed vaccine efficacy over a short time, and did not evaluate efficacy to the COVID variants of concern.

What is SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19?

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) is the virus that causes COVID-19 disease. Not everyone infected with SARS-CoV-2 will develop symptoms of COVID-19. Symptoms can be mild (e.g. fever and headaches) to life-threatening (e.g. difficulty breathing), or death.

How do vaccines prevent COVID-19?

While vaccines work slightly differently, they all prepare the body's immune system to prevent people from getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 or, if they do get infected, to prevent severe disease.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out how well each vaccine works in reducing SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 disease with symptoms, severe COVID-19 disease, and total number of deaths (including any death, not only those related to COVID-19).

We wanted to find out about serious adverse events that might require hospitalization, be life-threatening, or both; systemic reactogenicity events (immediate short-term reactions to vaccines mainly due to immunological responses; e.g. fever, headache, body aches, fatigue); and any adverse events (which include non-serious adverse events).

What did we do?

We searched for studies that examined any COVID-19 vaccine compared to placebo, no vaccine, or another COVID-19 vaccine.

We selected only randomized trials (a study design that provides the most robust evidence because they evaluate interventions under ideal conditions among participants assigned by chance to one of two or more groups). We compared and summarized the results of the studies, and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as how the study was conducted.

What did we find?

We found 41 worldwide studies involving 433,838 people assessing 12 different vaccines. Thirty-five studies included only healthy people who had never had COVID-19. Thirty-six studies included only adults, two only adolescents, two children and adolescents, and one included adolescents and adults. Three studied people with weakened immune systems, and none studied pregnant women.

Most cases assessed results less than six months after the primary vaccination. Most received co-funding from academic institutions and pharmaceutical companies. Most studies compared a COVID-19 vaccine with placebo. Five evaluated the addition of a 'mix and match' booster dose.

Main results

We report below results for three main outcomes and for 10 World Health Organization (WHO)-approved vaccines (for the remaining outcomes and vaccines, see main text). There is insufficient evidence regarding deaths between vaccines and placebo (mainly because the number of deaths was low), except for the Janssen vaccine, which probably reduces the risk of all-cause deaths.

People with symptoms

The Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Sinopharm-Beijing, and Bharat vaccines produce a large reduction in the number of people with symptomatic COVID-19.

The Janssen vaccine reduces the number of people with symptomatic COVID-19.

The Novavax vaccine probably has a large reduction in the number of people with symptomatic COVID-19.

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether CoronaVac vaccine affects the number of people with symptomatic COVID-19 because results differed between the two studies (one involved only healthcare workers with a higher risk of exposure).

Severe disease

The Pfizer, Moderna, Janssen, and Bharat vaccines produce a large reduction in the number of people with severe disease.

There is insufficient evidence about CoronaVac vaccine on severe disease because results differed between the two studies (one involved only healthcare workers with a higher risk of exposure).

Serious adverse events

For the Pfizer, CoronaVac, Sinopharm-Beijing, and Novavax vaccines, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether there was a difference between the vaccine and placebo mainly because the number of serious adverse events was low.

Moderna, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Bharat vaccines probably result in no or little difference in the number of serious adverse events.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Most studies assessed the vaccine for a short time after injection, and it is unclear if and how vaccine protection wanes over time. Due to the exclusion criteria of COVID-19 vaccine trials, results cannot be generalized to pregnant women, people with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or people with weakened immune systems. More research is needed comparing vaccines and vaccine schedules, and effectiveness and safety in specific populations and outcomes (e.g. preventing long COVID-19). Further, most studies were conducted before the emergence of variants of concerns.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is up to date to November 2021. This is a living systematic review. Our results are available and updated bi-weekly on the COVID-NMA platform at covid-nma.com.

Compared to placebo, most vaccines reduce, or likely reduce, the proportion of participants with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19, and for some, there is high-certainty evidence that they reduce severe or critical disease. There is probably little or no difference between most vaccines and placebo for serious adverse events. Over 300 registered RCTs are evaluating the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines, and this review is updated regularly on the COVID-NMA platform ( covid-nma.com ).

Implications for practice

Due to the trial exclusions, these results cannot be generalized to pregnant women, individuals with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or immunocompromized people. Most trials had a short follow-up and were conducted before the emergence of variants of concern.

Implications for research

Future research should evaluate the long-term effect of vaccines, compare different vaccines and vaccine schedules, assess vaccine efficacy and safety in specific populations, and include outcomes such as preventing long COVID-19. Ongoing evaluation of vaccine efficacy and effectiveness against emerging variants of concern is also vital.

Different forms of vaccines have been developed to prevent the SARS-CoV-2 virus and subsequent COVID-19 disease. Several are in widespread use globally.

To assess the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines (as a full primary vaccination series or a booster dose) against SARS-CoV-2.

We searched the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register and the COVID-19 L·OVE platform (last search date 5 November 2021). We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, regulatory agency websites, and Retraction Watch.

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing COVID-19 vaccines to placebo, no vaccine, other active vaccines, or other vaccine schedules.

We used standard Cochrane methods. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence for all except immunogenicity outcomes.

We synthesized data for each vaccine separately and presented summary effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We included and analyzed 41 RCTs assessing 12 different vaccines, including homologous and heterologous vaccine schedules and the effect of booster doses. Thirty-two RCTs were multicentre and five were multinational. The sample sizes of RCTs were 60 to 44,325 participants. Participants were aged: 18 years or older in 36 RCTs; 12 years or older in one RCT; 12 to 17 years in two RCTs; and three to 17 years in two RCTs. Twenty-nine RCTs provided results for individuals aged over 60 years, and three RCTs included immunocompromized patients. No trials included pregnant women. Sixteen RCTs had two-month follow-up or less, 20 RCTs had two to six months, and five RCTs had greater than six to 12 months or less. Eighteen reports were based on preplanned interim analyses.

Overall risk of bias was low for all outcomes in eight RCTs, while 33 had concerns for at least one outcome.

We identified 343 registered RCTs with results not yet available.

This abstract reports results for the critical outcomes of confirmed symptomatic COVID-19, severe and critical COVID-19, and serious adverse events only for the 10 WHO-approved vaccines. For remaining outcomes and vaccines, see main text. The evidence for mortality was generally sparse and of low or very low certainty for all WHO-approved vaccines, except AD26.COV2.S (Janssen), which probably reduces the risk of all-cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.67; 1 RCT, 43,783 participants; high-certainty evidence).

Confirmed symptomatic COVID-19

High-certainty evidence found that BNT162b2 (BioNtech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer), mRNA-1273 (ModernaTx), ChAdOx1 (Oxford/AstraZeneca), Ad26.COV2.S, BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm-Beijing), and BBV152 (Bharat Biotect) reduce the incidence of symptomatic COVID-19 compared to placebo (vaccine efficacy (VE): BNT162b2: 97.84%, 95% CI 44.25% to 99.92%; 2 RCTs, 44,077 participants; mRNA-1273: 93.20%, 95% CI 91.06% to 94.83%; 2 RCTs, 31,632 participants; ChAdOx1: 70.23%, 95% CI 62.10% to 76.62%; 2 RCTs, 43,390 participants; Ad26.COV2.S: 66.90%, 95% CI 59.10% to 73.40%; 1 RCT, 39,058 participants; BBIBP-CorV: 78.10%, 95% CI 64.80% to 86.30%; 1 RCT, 25,463 participants; BBV152: 77.80%, 95% CI 65.20% to 86.40%; 1 RCT, 16,973 participants).

Moderate-certainty evidence found that NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) probably reduces the incidence of symptomatic COVID-19 compared to placebo (VE 82.91%, 95% CI 50.49% to 94.10%; 3 RCTs, 42,175 participants).

There is low-certainty evidence for CoronaVac (Sinovac) for this outcome (VE 69.81%, 95% CI 12.27% to 89.61%; 2 RCTs, 19,852 participants).

Severe or critical COVID-19

High-certainty evidence found that BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, Ad26.COV2.S, and BBV152 result in a large reduction in incidence of severe or critical disease due to COVID-19 compared to placebo (VE: BNT162b2: 95.70%, 95% CI 73.90% to 99.90%; 1 RCT, 46,077 participants; mRNA-1273: 98.20%, 95% CI 92.80% to 99.60%; 1 RCT, 28,451 participants; AD26.COV2.S: 76.30%, 95% CI 57.90% to 87.50%; 1 RCT, 39,058 participants; BBV152: 93.40%, 95% CI 57.10% to 99.80%; 1 RCT, 16,976 participants).

Moderate-certainty evidence found that NVX-CoV2373 probably reduces the incidence of severe or critical COVID-19 (VE 100.00%, 95% CI 86.99% to 100.00%; 1 RCT, 25,452 participants).

Two trials reported high efficacy of CoronaVac for severe or critical disease with wide CIs, but these results could not be pooled.

Serious adverse events (SAEs)

mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1 (Oxford-AstraZeneca)/SII-ChAdOx1 (Serum Institute of India), Ad26.COV2.S, and BBV152 probably result in little or no difference in SAEs compared to placebo (RR: mRNA-1273: 0.92, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.08; 2 RCTs, 34,072 participants; ChAdOx1/SII-ChAdOx1: 0.88, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.07; 7 RCTs, 58,182 participants; Ad26.COV2.S: 0.92, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.22; 1 RCT, 43,783 participants); BBV152: 0.65, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.97; 1 RCT, 25,928 participants). In each of these, the likely absolute difference in effects was fewer than 5/1000 participants.

Evidence for SAEs is uncertain for BNT162b2, CoronaVac, BBIBP-CorV, and NVX-CoV2373 compared to placebo (RR: BNT162b2: 1.30, 95% CI 0.55 to 3.07; 2 RCTs, 46,107 participants; CoronaVac: 0.97, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.51; 4 RCTs, 23,139 participants; BBIBP-CorV: 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.06; 1 RCT, 26,924 participants; NVX-CoV2373: 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.14; 4 RCTs, 38,802 participants).

For the evaluation of heterologous schedules, booster doses, and efficacy against variants of concern, see main text of review.

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Positive and negative aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic among a diverse sample of US adults: an exploratory mixed-methods analysis of online survey data

- Stephanie A Ponce 1 ,

- Alexis Green 1 ,

- Paula D. Strassle 2 na1 &

- Anna María Nápoles 1 na1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 22 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

820 Accesses

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound social and economic impact across the United States due to the lockdowns and consequent changes to everyday activities in social spaces.

The COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) survey was a nationally representative, online survey of 5,500 American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Latino (English- and Spanish-speaking), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, and multiracial adults living in the U.S. For this analysis, we used data from the 1,931 participants who responded to the 6-month follow-up survey conducted between 8/16/2021-9/9/2021. As part of the follow-up survey, participants were asked “What was the worst thing about the pandemic that you experienced?” and “Was there anything positive in your life that resulted from the pandemic?” Verbatim responses were coded independently by two coders using open and axial coding techniques to identify salient themes, definitions of themes, and illustrative quotes, with reconciliation across coders. Chi-square tests were used to estimate the association between sociodemographics and salient themes.

Commonly reported negative themes among participants reflected disrupted lifestyle/routine (27.4%), not seeing family and friends (9.8%), and negative economic impacts (10.0%). Positive themes included improved relationships (16.9%), improved financial situation (10.1%), and positive employment changes (9.8%). Differences in themes were seen across race-ethnicity, gender, and age; for example, adults ≥ 65 years old, compared to adults 18–64, were more likely to report disrupted routine/lifestyle (37.6% vs. 24.2%, p < 0.001) as a negative aspect of the pandemic, and Spanish-speaking Latino adults were much more likely to report improved relationships compared to other racial-ethnic groups (31.1% vs. 14.8–18.6%, p = 0.03).

Positive and negative experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic varied widely and differed across race-ethnicity, gender, and age. Future public health interventions should work to mitigate negative social and economic impacts and facilitate posttraumatic growth associated with pandemics.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on morbidity and mortality, as well as the social, behavioral, and economic impacts have been well-documented. As of May 23, 2023, the CDC estimates that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused 6,152,982 hospitalizations and 1,128,903 deaths in the United States (U.S) [ 1 ]. In addition to the pandemic itself, mitigation measures adopted during the pandemic to reduce transmission across the U.S. also had major social and economic impacts [ 2 ]. Efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 infection, including social distancing, lockdowns, and transitions to remote work, became a source of life disruptions and emotional distress [ 3 , 4 ]. Racial-ethnic disparities in the burden of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, as well as negative social and economic consequences have been reported.

However, mitigation efforts and COVID-related policies also may have had positive impacts. Traumatic events, life crises, and illnesses, although challenging to move through, have often resulted in positive psychological change as people seek new ways of making meaning from these experiences. These positive psychological changes that result from traumatic events have been referred to as posttraumatic growth and defined as “positive psychological changes experienced as a result of the struggle with trauma or highly challenging situations.” [ 5 ] Previous research has indicated that women experience higher levels of posttraumatic growth, compared to men, and that increasing age moderates posttraumatic growth among women [ 6 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women have been found to report higher posttraumatic growth during quarantine [ 7 ] and COVID-19 related hospitalization [ 8 ]; however, these studies were not based in the United States.

Additionally, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many companies adapted by creating new telework and flexible work schedule policies during lockdowns, [ 9 , 10 ] which have been associated with improved work-life balance and family relationships [ 11 , 12 ]. Initial reports during the pandemic indicate that the lockdown period also served as a time to find oneself [ 13 ], pursue new passions and hobbies [ 13 ], and save money [ 14 ] due to the lack of regular social outings and a decrease in transportation related expenses such as gas. COVID-19 associated posttraumatic positive growth experiences have not been well-researched, especially across diverse racial-ethnic groups.

Given the extensive social, behavioral, and economic changes and mitigation measures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to understand the positive and negative perceived consequences of these events among U.S. adults, and any differences across race-ethnicity, gender, and age. Thus, the purpose of this mixed-methods study was to capture the voices of a diverse, national sample of American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Latino (English- and Spanish-speaking), White, and multiracial adults (≥ 18 years old) living in the U.S and perceived major positive and negative impacts of the pandemic.

Study population and survey development

For this study we used data from the COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) online survey, which was administered by YouGov, a nonpartisan consumer research firm based in Palo Alto, CA, which uses a proprietary, opt-in survey panel comprised of over 1.8 million US residents to conduct nationally representative surveys. Panel members are recruited through a variety of methods to ensure diversity, and then were matched to a theoretical target sample. For this study, the target sample was drawn from the 2018 American Community Survey 1-year sample data, and included 1,000 Asian, 1,000 Black/African American, 1,000 Latino (including 500 Spanish-speaking), 1,000 White, 500 American Indian/Alaska Native, 500 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 500 multiracial adults aged ≥ 18 years (n = 5,500 total). The survey was conducted in both English and Spanish (Latino participants only). The baseline CURB survey was first created in English, translated into Spanish by an American Translators Association certified translator, and then finalized by four bilingual/bicultural researchers via reconciliation and decentering methods. Questions added or modified in the follow-up survey were translated into Spanish by our bilingual/bicultural researchers.

The baseline survey was completed between December 8, 2020, and February 17, 2021, and the 6-month follow-up survey between August 16, 2021, and September 9, 2021 (35.1% response rate), Supplemental Table 1 . For this analysis, we included all participants who responded to both the baseline and 6-month follow-up survey (n = 1,931). The CURB survey development and sampling design details have been previously described [ 15 ].

The National Institutes of Health Office of Institutional Review Board Operations determined that this study does not qualify as human subjects research because data were de-identified (IRB# 000166).

Identifying negative and positive aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic

As part of the 6-month follow-up survey, all participants were asked two open-ended questions: (1) What was the worst thing about the pandemic that you experienced? and (2) Was there anything positive in your life that resulted from the pandemic? Verbatim responses were coded independently using open and axial coding methods in two steps by two coders (SAP, AG) [ 16 ]. Responses from Spanish-speaking Latino participants were translated into English, reviewed, and reconciled by two bilingual-bicultural research team members (SAP, AMN) prior to coding. In the first step, coders categorized responses to both questions using open coding methods (breaking the data into discrete parts and creating codes to label them). Then, applying axial coding methods (i.e., codes were organized into categories/themes), the responses for each question were coded for salient themes, definitions of themes, and illustrative quotes. Consensus was reached through iterative meetings between the coders and the rest of the study team.

Participant sociodemographics

Race-ethnicity was captured by asking respondents “Which one of the following would you say best describes your race/ethnicity?” with response options of Latino/a/x or Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Pacific Islander, White, and multiracial. Latino participants were further stratified into English- and Spanish-speaking, depending on their survey language preference; 68.9% of Spanish-speaking Latino participants also self-reported limited English proficiency, compared to only 5.4% of English-speaking Latino participants. Gender was categorized as male, female, and transgender or nonbinary. Age was captured as a continuous variable and categorized as 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥ 65 years old.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and Chi-square tests were used to compare the prevalence of salient themes for the two open-ended questions across self-reported race-ethnicity, gender, and age. Due to the small number of participants that identified as transgender or non-binary (n = 26), comparisons across gender were restricted to comparing male and female participants only. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Due to the relatively low response rate of the follow-up survey, results were not weighted to generate nationally representative estimates.

Worst aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic

Overall, 1,511 of 1,931 participants (78.2%) responded to “What was the worst thing about the pandemic that you experienced?” Respondent characteristics can be found in Supplemental Table 2 .

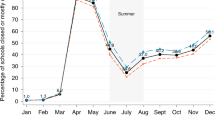

Salient themes, definitions, and illustrative quotes for the worst aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic are reported in Table 1 . Overall, the most commonly reported negative aspect was disrupted lifestyle/routine (27.4%), Fig. 1 A. Responses included disrupted lifestyle/routine due to reduced services and restrictions in places like school, healthcare settings, restaurants, places of worship, and other places of recreation or routine outings. Missed important life events such as graduations, weddings, and internship opportunities were also noted. Adults ≥ 65 years-old, compared to adults 18–64, were more likely to report disrupted routine/lifestyle (37.6% vs. 24.2%, p < 0.001) as a negative impact of the pandemic, Supplemental Fig. 1 A. No significant racial-ethnic or gender differences in the prevalence of disrupted lifestyle/routine were observed.

Overall prevalence of reported (A) negative and (B) positive impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among a diverse sample of adults living in the US, COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) survey, 8/16/2021-9/9/2021

“My senior year of college was ruined by the pandemic. I missed my senior cross-country season and the chance to go to nationals in indoor track.” (Female, 18–34 years old, White).

The next most commonly reported worst aspect was negative economic impacts (10.0%), Fig. 1 A. Respondents reported negative changes in employment/unemployment, decreased financial security, decreased job security, increased cost of products/living, and increased shortages. Younger adults (< 65 years old) were more likely to report negative economic impacts compared to adults ≥ 65 years old (11.0% vs 2.3%, p = 0.001), Supplemental Fig. 1 B.

“Not being able to purchase certain food items, toilet paper, paper towels, masks, disinfectant spray. The prices of items increasing.” (Female, 18–34 years old, multiracial).

“Recently having to live off one income plus whatever unemployment pays. My bank account has been negative, often because of bills being pulled and not having the funds.” (Female, 35–49 years old, English-speaking Latino).

Overall, not seeing family/loved ones (9.9%) and (9.0%) isolation were reported as negative aspects by roughly 1 in 10 respondents, respectively, Fig. 1 A. Reasons included concerns of transmission and decreased quality of social interactions due to masking and social distancing. Women, compared to men, were more likely to report not seeing family/loved ones as the worst aspect of the pandemic (12.5% vs. 6.6%, p < 0.001). Increasing age was associated with being more likely to report not seeing family/loved ones (18–34 years old, 6.8%; 35–49 years old, 8.5%; 50–64 years old, 11.0%;and ≥ 65 years old, 13.1%; p = 0.034). Racial-ethnic differences were also observed ( p = 0.004), with Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (15.3%), White (12.2%), Asian (10.7%), and English-speaking Latino (10.2%) adults reporting higher prevalence of not seeing family/loved ones compared to, Fig. 2 . No significant differences in the reporting of isolation were seen across race-ethnicity, gender, or age.

Prevalence of reporting not seeing family/loved ones during the COVID-19 pandemic, stratified by race-ethnicity, among a diverse sample of adults living in the US, COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) survey, 8/16/2021-9/9/2021

" Me senti alejado del mundo y necesitaba contacto con otras personas pero creo que la pandemia todavia no ha pasado” (“I felt cut off from the world and needed contact with other people but I believe that the pandemic has not yet passed”) (Female, 50–64 years old, Spanish-speaking Latino).

“Being separated from my kids and grandchildren who live in another state 2500 miles from my home. During the pandemic we planned and canceled three trips to see them. Finally made the trip after 18 months without in person contact.” (Male, ≥ 65 years old, White).

Other negative aspects reported were fear (8.9%), death/loss of a loved one (6.7%), negative perceptions of others (6.4%), having to mask (5.3%), misinformation (4.9%), travel restrictions (4.5%), others ignoring mandates (4.1%), getting or having a loved one get COVID-19 (3.7%), psychological distress (3.4%), political polarization (2.5%), government control/loss of autonomy (2.4%), and worse health/health behaviors (1.7%), Fig. 1 A.

Positive aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic

Overall, 1,033 participants responded to “ Was there anything positive in your life that resulted from the pandemic? ” (53.5%). Respondent characteristics are reported in Supplemental Table 2 .

Salient themes, definitions, and illustrative quotes for the positive impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are reported in Table 2 . The most commonly reported positive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was improved relationships (16.9%), Fig. 1 B. Reasons for improved relationships included spending more time at home and more quality time with loved ones. Women (18.8% vs. 15.0% p = 0.03) and adults 18–49 years old (20.1% vs. 14.2%, p = 0.004) were more likely to report improved relationships, compared to men and older age groups, Supplemental Fig. 2 A. Spanish-speaking Latino adults were also much more likely to report improved relationships compared to other racial-ethnic groups, (31.1% vs. 14.8–18.6%, p = 0.03), Fig. 3 A.

Prevalence of reporting (A) improved relationships , (B) improved financial situations , and (C) positive employment changes , stratified by race-ethnicity, among a diverse sample of adults living in the US, COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) survey, 8/16/2021-9/9/2021

“Got to spend more time with family. Reconnected with friends I had lost touch with.” (Male, 35–49 years old, Asian).

Improved financial situation (10.1%) and positive employment changes (9.8%) were also reported as positive results of the pandemic. Reasons included increased savings, increased work flexibility, increased income, and reduced commutes. Improved financial situation was more commonly reported by men compared to women (12.3% vs. 8.2%, p = 0.003), Supplemental Fig. 2 B. Positive employment changes were more often reported by younger adults (18–49 years old) compared to older age groups (13.5% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.001), Supplemental Fig. 2 C. American Indian/Alaska Native and Spanish-speaking Latino adults were less likely to report improved financial situation and positive employment changes as positive aspects of the pandemic, compared to other racial-ethnic groups (11.2% v. 6.4%, p = 0.001), Fig. 3 B,C.

“I received unemployment and extra federal UI benefits so was able to save and payoff my auto loan early.” (Female, 50–64 years old, Black/African American).

“I got paid more money from my current employer.” (Male, 18–34 years old, multiracial).

Participants also reported improved health habits (6.3%), increased time for leisure activities (6.1%), personal growth (5.3%), pace of life slowing down (5.0%), ability to work from home (4.9%), saving money (4.5%), feelings of gratitude (3.6%), increased government assistance (2.6%), appreciation for mitigation measures (2.1%), increased use of technology for communication (2.0), and strengthened/newfound spirituality (1.8%), Fig. 1 B.

This mixed-methods study investigated perceived negative and positive experiences associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in from the perspectives of racially-ethnically diverse U.S. adults. Overall, negative aspects of the pandemic were reported more frequently than positive ones. Salient perceptions of the worst aspects of the pandemic included disrupted lifestyle/routine, negative economic impacts, not seeing family/loved ones, and isolation. Disrupted lifestyles and routines and not seeing family and loved ones were more frequently reported by older adults compared to younger age groups, while younger adults were more likely to report negative economic impacts. Not seeing family and loved ones was more frequently reported also by Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, Asian, and English-speaking Latino adults than other racial-ethnic groups. The most common positive aspects of the pandemic reported included improved relationships, improved financial situation, and positive employment changes. Women, adults aged 18–49 years, and Spanish-speaking Latino adults were more likely than men, older age groups, and other racial-ethnic groups to report improved relationships with family and friends as positive aspects. American Indian/Alaska Native adults and Spanish-speaking Latino adults, were less likely to report positive economic impacts, compared to other racial-ethnic groups. These findings highlight the importance of qualitative research in capturing life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The high prevalence of disrupted lifestyles can be attributed to restrictions on public spaces, the transition to online spaces, and changes in available services during the peak of the pandemic in the U.S. are expected. New York, for example, closed all nonessential businesses and restricted out-of-home activities for residents beginning in March 22, 2020 [ 17 ]. However, in the United States these policies were implemented on a state-by-state (and sometimes city-by-city) basis, leading to differences across the country [ 18 ]. Many of these closures/restrictions led to students and employees transitioning their classroom and office spaces to home settings, significantly changing their household dynamic. Learning and work environments were dependent on the spaces available, which in some cases were crowded, loud, and suboptimal, especially for those in a household with more than one person distance learning or working from home [ 19 ]. Routine outings for groceries and necessities also became high-risk and, in some cases, contactless, further reducing opportunities for movement and social interaction [ 20 ]. Reduced opportunities for social interaction and movement during the pandemic have been reflected in reported decreases in steps and increases in screentime [ 21 ].

Disruptions in daily activities, business closures, and restricted out-of-home activities also appeared to have severe negative consequences on individual and household finances. Individuals reported increased financial insecurity, loss of job or job security, and an overall negative change in their financial situation because of the pandemic. Both our study and others have found that younger adults disproportionately experienced financial strain because of the pandemic [ 22 , 23 ]. Other studies have also reported that financial hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic was more substantial among racial-ethnic minorities and low-income adults [ 24 , 25 ].

Interestingly, we also found that two of the most common positive aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic were improvements in financial situations and employment situations. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in large increases in the proportion of the workforce teleworking and most likely led to improved work life balance due to fewer commute hours. Over half of individuals able to work from home have reported that working from home has made it easier to balance work with their personal life [ 26 ]. Beyond work from home flexibility, opportunities for hazard pay, government pandemic assistance, and reduced spending were associated with the pandemic allowing for some households and individuals to strengthen or gain financial security. However, increased financial stability has been primarily reported by upper-income and middle-income households, retired adults, and among adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher [ 25 , 27 ].

Improvements in relationships with family, loved ones, and neighbors were also reported, most likely due to increased use of immediate social networks to satisfy social interaction needs and reduce isolation, when broader engagement was limited due to enforced restrictions on public spaces and travel. Lockdowns across the country led to spending more time at home with family and loved ones [ 28 ]. Conversely, studies have also found an increase in reported loneliness and isolation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, [ 29 , 30 , 31 ] prompting the U.S. Surgeon General to release a 2023 report on the “loneliness and isolation” epidemic in the U.S., exacerbated by the pandemic [ 32 ]. Quarantining during prior outbreaks has been associated with poor mental health, and increased feelings of isolation, anger, confusion, and frustration [ 33 , 34 ]. Additional research on the impact of social networks and household structures on feelings of isolation and loneliness during lockdowns and quarantines are needed to better understand how to prevent poor mental health during future outbreaks.

Social distancing also encouraged increased use of texting, video calling, and social media as means of communication [ 35 ]. It could be that increased use of these alternatives to in-person contact led to more frequent and/or improved quality of social interactions and relationships for some individuals. For example, in a study among Italian adults, voice and video calls, online gaming platforms, social media, and watching movies in party mode were associated with reduced feelings of loneliness, anger, and boredom due to perceived social support from these interactions [ 36 , 37 ]. A study among Australian adults found that communicative smartphone use during the pandemic was found to increase friendship satisfaction over time [ 38 ]. Further research in the potential of technology to reduce isolation and improve social connections is warranted. However, cultural values influence interpersonal interaction styles and preferences and need to be considered. For example, the high proportion of Spanish-speaking Latino adults reporting improved relationships may be tied to familism (i.e., the cultural emphasis on one’s family as a main source of emotional and instrumental social support when needed, including elements of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity within one’s family) [ 39 ]. At least one other study has also found that Latino adults reported positive changes in their relationships during the pandemic [ 40 ].

Similar to findings from the SARS epidemic in 2002–2004, [ 41 ] our participants also reported positive experiences of personal growth, living life at a slower pace, more time for leisure activities, and increased feelings of gratitude due to the pandemic. The additional time to pause and reflect, paired with the hardships of the pandemic, led many to adopt new perspectives characterized by greater appreciation of the people in their lives and for life in general [ 42 ]. Our study results support the important role of gratitude and its potential for bolstering resilience during times of tragedy and uncertainty [ 43 ]. In total, these experiences can be framed as posttraumatic growth resulting from the challenges of the pandemic. Such personal growth may serve a protective role in buffering the negative effects of fear associated with pandemics, and enhance satisfaction with life [ 44 ] and psychological wellbeing especially among older adults [ 45 , 46 ]. Public health efforts to support such growth during widespread pandemics could focus on evidence-based methods for generating posttraumatic growth and emotional resiliency, such as education to enhance emotional regulation, disclosure, meaning finding in trauma, and service to others [ 5 ].

This study adds to the sparse literature characterizing social patterning of positive and negative changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the potentially contradictory effects of the pandemic on individuals. Our study’s use of qualitative methods has allowed us to capture the nuances of respondents’ lived experiences within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Differences across age, gender, and race-ethnicity captured in this study point to a diversity of experiences and the need for recovery strategies tailored to community needs. The nationally representative sample employed in our study also facilitated our capturing a broad range of experiences across racial/ethnic minority, language, age, and gender groups.

Study limitations include our low response rate to the follow-up survey, which may have inhibited our ability to detect statistically significant differences in responses to the two open-ended questions. Response rates also differed across participant race-ethnicity and not all participants responded to the open-ended questions, which may have impacted findings. Additionally, our 6-month follow-up survey was conducted in August-September 2021, and respondents’ experiences may have changed over time as the pandemic continued to evolve. The surveys were also administered online, and individuals with limited internet access or familiarity with technology and limited literacy may have been less likely to participate. For example, we did not find racial-ethnic differences in reports of negative economic experiences, possibly due to the online nature of our survey, which may have biased our sample toward those with greater economic resiliency. However, the potential of online surveys to conduct qualitative research has been previously noted [ 47 ]. Furthermore, the CURB survey was only administered in English and Spanish (for Latino participants), which means adults who prefer other languages were likely to be excluded. This may have especially impacted our Asian adult cohort, as 31.9% of Asian adults nationally are estimated to have limited English proficiency (compared to 12.3% in our survey). Finally, our survey was not designed to capture an equal number of individuals living in each state or city, and the effects of the heterogeneous COVID-19 responses across the country may not have been captured fully.

In this study, we used a mixed-methods approach to capture the perceived negative and positive impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s lives among a diverse group of adults. Responses varied by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, indicating that the lived experiences of diverse groups differed, most likely due to variation in access to economic and social resources for managing COVID-related disruptions and hardships. A more nuanced understanding of such variation in the perceived positive and negative effects of pandemics can inform tailored public health efforts to mitigate potentially harmful factors and support posttraumatic growth and emotional resiliency during health crises.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request. Contact Dr. Paula Strassle ([email protected]) for access.

Abbreviations

COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden

United States

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention

Stephanie A. Ponce

Alexis Green

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. 2023. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker . Accessed 28 June 2023.