- Armed Conflict and Heritage

- Culture in Emergencies

- Disaster Risk Reduction

- Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Property

- Revive the Spirit of Mosul

- Culture and Sustainable Development

- Culture and Climate change

- Culture and Biodiversity

- Culture and Education

- Culture and Africa

- World Heritage

- Intangible Cultural Heritage

- Underwater Cultural Heritage

- Memory of the World

- Diversity of Cultural Expressions

- Creative Cities

- Culture for Small Island Developing States

- World Book Capital Network

- COVID-19 pandemic

- UNESCO-MONDIACULT 2022 World Conference

- The Tracker Culture & Public Policy

- Culture in the G20

- Inter-Agency Platform

- International Funds for Culture

- Category 2 Centres and Institutes in Culture

- International Day of Nowruz

- World Art Day

- World Book and Copyright Day

- International Jazz Day

- African World Heritage Day

- International Day against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property

- International Day of Islamic Art

- World Olive Tree Day

- International Arts Education Week (20-26 May)

- 2023 - 20th Anniversary of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage

- 2021 - International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development

- 2019 - International Year of Indigenous Languages

- 2017 - International Year of Sustainable Tourism

- 2010 - International Year for the Rapprochement of Cultures

- Legal Instruments

- Publications

Cultural heritage: 7 successes of UNESCO’s preservation work

The power of preserving cultural heritage to build a better world

Why do we go to great lengths to preserve culture and make it bloom? Culture is a resource for the identity and cohesion of communities. In today’s interconnected world, it is also one of our most powerful resources to transform societies and renew ideas. It is UNESCO’s role to provide the tools and skills we need to make the most of its ultimate renewable energy.

Historical landmarks, living heritage and natural sites enrich our daily lives in countless ways, whether we experience them directly or through the medium of a connected device. Cultural diversity and creativity are natural drivers of innovation. In many ways, artists, creators and performers help us change our perspective on the world and rethink our environment. These are precious assets to respond to current global challenges, from the climate crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The notion of culture has greatly evolved over the last 75 years. UNESCO’s actions over the past decades bear witness to the many ways in which humanity tried to understand how culture can strengthen the sense of who we are – from the awareness of the necessity to protect heritage from destruction at the end of World War II, to the launch of international campaigns to safeguard World Heritage sites and the concept of living and intangible heritage, a focus on creative economy and the need to sustain cultural jobs and livelihoods. Our relationship with culture has deeply evolved over the last century. If we look into the past, we might be better prepared to tackle further changes ahead.

The United States will be participating in an international effort which has captured the imagination and sympathy of people throughout the world. By thus contributing to the preservation of past civilizations, we will strengthen and enrich our own.

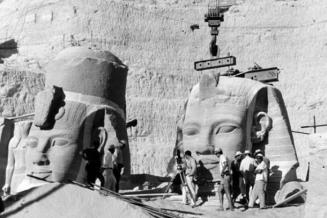

Abu Simbel – We do not have to choose between the living and the dead

A few minutes before sunrise, thousands of visitors line up inside the temple of Abu Simbel, holding their breath. They are about to witness a rare phenomenon that has taken place twice a year for the last 3,000 years. Every February and October at 6:29 am, the light of the rising sun pierces through the narrow entrance. The rays penetrate over 70 metres deep across the giant pillared hall up to the inner sanctuary, illuminating the statue of the man who built the temple during the 13th century BC, Pharaoh Ramses II.

Carved out of a rocky hill, the Temple of the Rising Sun had been conceived to show the might of Egypt’s greatest pharaoh to the Nubian people in the Upper Nile. Over time, the great temple and the smaller buildings became covered in sand and lay forgotten for centuries, until their rediscovery in 1813. The supreme example of ancient Egypt’s knowledge of astronomy and the skill of its architects could be admired again.

But just over a century later, the southernmost relics of this ancient human civilization were threatened with underwater oblivion and destruction by the rising waters of the Nile following the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The construction of the Dam was meant to develop agriculture as well as Egyptian independence and economy, and triggered a global debate that has fuelled media front pages and discussions ever since: should we have to choose between the monuments of the past and a thriving economy for the people living today? Why should people care for ancient stones and buildings when so many people need food and emergency assistance?

In the course of an unprecedented safeguarding campaign to save the temples of Egypt, UNESCO demonstrated that humanity does not have to sacrifice the past to thrive in the present – quite the opposite. Monuments of outstanding universal value help us understand who we are and also represent massive opportunities for development. Two millennia after a Greek author and scientist drew the famous list of the world’s seven wonders, the very notion of World Heritage came to life.

The race against time began in 1964 , when experts from 50 nations started working together under the coordination of UNESCO in one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history. The entire site was carefully cut into large blocks, dismantled, lifted and reassembled in a new location 65 metres higher and 200 metres back from the river, preserving it for future generations.

Today, the four majestic statues that guard the entrance to the great temple stare at the river and the rising sun every day. As they did 3,000 years ago. The success of the international cooperation to save Abu Simbel raised awareness about the fact that all over the world there are places of outstanding universal value. Just like the Nile valley temples, they must be protected from many threats such as armed conflict, deliberate destruction, economic pressure, natural disasters and climate change.

The World Heritage Convention was adopted in 1972 as the most important global instrument to establish this notion, bringing all nations together in the pursuit of the preservation of the World’s Natural and Cultural Heritage. With its 194 signatory Member States, it is today one of the world’s most ratified conventions.

How is a site inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List?

For a site to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, it must first be nominated by the country where it is located. The nomination is examined by international experts who decide whether the inclusion is justified. Finally, the World Heritage Committee, a body of 21 UNESCO elected Member States, takes a vote.

Venice – Can the safeguard of cultural heritage and global tourism coexist?

Launched only a few years after the Nubian temples initiative, the safeguarding campaign for Venice was a response to various challenges including the rising waters and the explosion of global tourism.

Stepping outside the railway station early on an autumnal morning, visitors are met with the view of the chilly air colliding with the water, forming a thick, soft blanket of fog over the Grand Canal, the ‘main street’ of Venice. The church of San Simeone Piccolo, with its oversized dome and slender neoclassical columns, and the neighbouring buildings appear to be floating on the water of the lagoon. It’s a sight that has welcomed millions of visitors from all over the world since the heydays of the Serenissima, when the city ruled as one of Europe’s economic superpowers.

Yet, the breath-taking beauty that inspired countless painters, writers and artists over the centuries remains fragile and at risk of being lost forever. Like the Abu Simbel temples, the city’s survival is threatened by rising water levels. The inexorable increase in sea level has caused flooding to become a regular occurrence. Humidity and microorganisms are eating away the long wooden piles that early dwellers drove deep into the muddy ground of the lagoon to build the first foundations of Venice, 1,600 years ago.

After 1966, the year of the worst flooding in Venice’s history, UNESCO and the Italian Government launched a major campaign to save the city. An ambitious project involving giant mobile flood gates was undertaken to temporarily isolate the lagoon from the high tides and protect the lowest areas from flooding. Thirty years later there is unanimous agreement on the successful results both of the technical achievements and international cooperation.

But Venice still needs attentive care, and its continued survival calls for unflagging vigilance. The city remains threatened on several fronts – mass tourism, the potential damage of subsequent urban development and the steady stream of giant cruise ships crushing its brittle foundations.

International mobilization and pressure around the status of Venice led to the Italian Government’s decision in 2021 to ban large ships from the city centre, as a necessary step to protect the environmental, landscape, artistic and cultural integrity of Venice. This decision came a few days after UNESCO announced its intention to inscribe the city on its World Heritage in Danger list. Until a permanent big cruise docking place is identified and developed, liners will be permitted to pull up in Marghera, an industrial suburb of Venice. Such decisions illustrate the great complexity of protecting historic cities and cultural heritage urban centres, which in this particular situation called for tailor-made measures and techniques different from those implemented for the safeguarding of the fabled Egyptian temples.

If every museum in the New World were emptied, if every famous building in the Old World were destroyed and only Venice saved, there would be enough there to fill a full lifetime with delight. Venice, with all its complexity and variety, is in itself the greatest surviving work of art in the world.

Angkor – A successful example of longstanding international cooperation

Deep in the forests of Cambodia, in the Siem Reap Province, the five lotus-flower-shaped towers of majestic Angkor Wat soar towards the sky. When approaching from the main gate, the vast scale of the temple and the precise symmetry of the buildings are awe inspiring. This is the world's largest religious monument.

Angkor Wat was part of a sprawling city as big as London, the heart of an empire that between the 9th and 15th centuries extended from southern Vietnam to Laos, and from the Mekong River to Eastern Myanmar. By around 1500 A.D., the Khmer capital was abandoned, most likely after heavy floods and lengthy droughts. Its temples, buildings and complex irrigation network were swallowed by the surrounding forests and lay hidden until their rediscovery in 1860.

By the early 1990s, the site was under major threat, with many of the temples at high risk of collapse and several sites looted. Conservation work at Angkor had not been possible since the outbreak of the civil war, the rise of the Khmer Rouge regime and the following civil unrest.

Angkor Wat’s inclusion in UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1992 marked a milestone in the country’s recovery after years of conflict. The UNESCO-backed preservation of the temples aimed to assist in nation-building and national reconciliation. The action of the International Coordinating Committee (link is external) (ICC-Angkor) for the safeguarding and development of this exceptional cultural site is a striking example of international solidarity and testifies to one of UNESCO's most impressive achievements for heritage. Thirty countries and an ad hoc experts group for scientific, restoration and conservation projects were brought together under an innovative approach, closely linking safeguarding operations to sustainable development efforts.

In 25 years, Angkor has thus become a living laboratory demonstrating the potential of sustainable tourism and crafts, with the mobilization of local communities for social cohesion in 112 villages. The gigantic site now supports 700,000 inhabitants and attracts some five million visitors whose flow must be managed each year. The park authorities are carrying out several projects aimed at improving the lives of communities through the implementation of sustainable tourism that respects local sensitivities. The removal from UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger just fourteen years later is a credit to the Cambodian people.

The fact that a project of such magnitude was successfully carried out in a country emerging from more than two decades of conflict in 1992 is a testament to the potential of the World Heritage Convention and the international solidarity led by UNESCO.

Walking through the temple, I saw reminders of the prosperous civilization that built it: hundreds of beautiful figures carved into the walls telling the stories of these ancient people; wide galleries they must have prayed in; long hallways lined with pillars they must have walked down.

No one knows for sure what caused the empire to abandon this temple and the surrounding city, but in the 15th century almost everyone left. Trees grew over the stones. Only Buddhist monks stayed behind to care for — and pray in — the hidden temples.

But that didn’t stop pilgrims and visitors from continuing to journey here to take in these incredible structures. And now, centuries later, I couldn’t be more thankful to count myself as one of these visitors

Mostar – Symbols do matter, in war and peace

It’s the end of July in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Peak summer means an influx of tourists to the cobbled alleys of Mostar. The cosy medieval town has a long, rich history marked by the peaceful coexistence of three communities: Muslim Bosniaks, Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats. Once they arrive in town, visitors from all over the world make a beeline for Mostar’s most emblematic monument, the Old Bridge.

A masterpiece of Ottoman architecture, Stari Most – as it’s known locally – is a symbol of the different communities that have existed side-by-side in the area. Since the 16th century, the bridge had brought them together across the Neretva river – until the Bosnian war. The bridge was a symbol of unity between the Bosnian community (Muslim), in the east of the city, and the Croats and Serbs to the west. The bridge of Mostar (of Ottoman, therefore Muslim origin) served as a link between all these communities – as a pedestrian bridge, it had no military or strategic value. Its destruction in 1993 was only meant to force the communities to separate, to deny their mixing with their neighbours. The bridge was in ruins and, with it, the values of peace and understanding this centuries-old structure had embodied.

Five years later, UNESCO coordinated a reconstruction project to rebuild the Old Bridge. Despite the scars of the war that are still visible today on the city walls, the reconstructed bridge has now become a symbol of reconciliation and post-conflict healing.

Today, the crowds jam the street to watch the traditional diving contest from the top of the bridge, a long-held custom resumed once Stari Most was restored to its former glory. Every July, young people of Mostar’s three communities compete with courage by jumping into the river 29 metres below, just like they did before the war.

For over four years after the ceasefire, former enemies worked together to retrieve the stones from the riverbed and rebuild their former symbol of friendship. Reconstructed in 2004 and inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 2006, Stari Most today is a bridge between a common past and a common future. It is certainly not enough to rebuild a bridge to restore confidence and rebuild peace in a war-torn society. But it certainly matters to care for the symbols of peace.

I was in my office, working to the sound of mortar fire, when we heard the cries in the street – cries that the bridge had fallen. And what happened then was so impressive that I will never forget it. Everyone came out to see. Grenades and bombs were falling everywhere, but still they came out of their hiding places: young and old, weak and strong, Muslim and Christian, they all came, all crying. Because that bridge was part of our identity. It represented us all.

Timbuktu – When warlords target heritage, peacemakers respond with more heritage

Sitting at the gateway to the Sahara Desert, Timbuktu conjures images of a mythical city at the end of the world, where Arab and African merchants would travel from afar to trade salt, gold, cattle and grain. In the English language, the city in northern Mali has come to represent a place far away. Undaunted, caravans still ply the cross-desert route and come to the city several times a year. They carry rock salt extracted from the northern Sahara, just like their ancestors did for centuries.

In its heyday, during the 16th century, the city had 100,000 inhabitants, as its mosques and holy sites played an essential role in the spread of Islam in Africa. The city became an important centre of learning in Africa and its libraries the repository of at least 700,000 historical manuscripts on art, science and medicine, as well as copies of the Qur’an. These manuscripts, written in ornate calligraphy, bear witness to the richness of African history and intellectual life.

During the conflict of 2012–2013, more than 4,000 of the 40,000 manuscripts kept at the Ahmed Baba Institute were lost. Some were burnt or stolen, while more than 10,000 remained in a critical condition. The inhabitants of Timbuktu helped save their precious heritage by secretly spiriting away more than 300,000 manuscripts to the capital, Bamako. Other texts were sheltered between mud walls or buried. Although protected from immediate destruction, the manuscripts are now preserved in conditions that may not safeguard them for future generations.

To help preserve Timbuktu’s cultural heritage and encourage reconciliation, UNESCO has been supporting the local communities to take part in ancient manuscript conservation projects and ensure their lasting preservation for humanity.

UNESCO has coordinated the work to rebuild the fourteen mausoleums inscribed on the World Heritage List, as well as the Djingareyber and Sidi Yaha mosques, that were deliberately destroyed by armed groups during the conflict.

The reconstruction of Timbuktu’s devastated cultural heritage aimed to foster reconciliation among communities and restore trust and social cohesion. An important aspect of the project was the drive to include the reconstruction of the mausoleums in an overall strategy aimed at revitalizing building traditions and ensuring their continuity, through on-the-job training activities and conservation projects.

To ensure the rebuilt shrines matched the old ones as closely as possible, the reconstruction work was checked against old photos and local elders were consulted. Local workers used traditional methods and local materials, including alhor stone, rice stalks and banco – a mixture of clay and straw.

The destruction of the mausoleums of Timbuktu has been a shock, and a clear turning point revealing the importance taken of culture and heritage in modern conflicts fuelled by violent extremism and fundamentalist ideologies. It has shown how strongly fundamentalists are willing to destroy other Islamic cultures, and any other vision which differs from their own. Similar direct destruction of Islamic, pre-Islamic, Christian or Jewish heritage, has then been seen in Iraq and Syria. The need to restore heritage has become far more than a mere cultural issue – it has become a security issue, and a key component for the resilience and further cohesion of societies torn by conflicts.

At present, the monuments in Timbuktu are living heritage, closely associated with religious rituals and community gatherings. Their shape and form have always evolved over time both with annual cycles (that of the rain and the erosion of the plastering); that of regular maintenance (every three to five years); repairs of structural pathologies, often adding buttresses; and at times more important works, including extensions and raising of the roof structure. How to take that into account while trying to guide and assist the local people in their self-capacity, their resilience in keeping their heritage as they have done for over 600 years? What should be done and to what extent? Who should be responsible for what? These are tricky questions of heritage preservation, far beyond the mere inscription of a site on the famous World Heritage list.

Salt comes from north, gold from south and silver from the land of Whites, but the Word of God, the famous things, histories and fairy tales, we only find them in Timbuktu.

Preserving cultural identity and Korean traditions: The bond of living heritage

It’s the end of November in the countryside near Jeonju, the capital of the North Jeolla Province. The weather is getting chilly and winter is just a couple of weeks away.

It’s time to prepare for the long, icy-cold season. It’s time to make kimchi.

The Republic of Korea’s staple food is a side dish of salted and fermented vegetables that makes its appearance at every meal. It’s not just the country’s emblematic dish: its preparation ( kimjang ) is a community event.

Housewives monitor weather forecasts to determine the most favourable date and temperature for preparing kimchi. Entire families, friends and neighbours gather together to make it. The process is rather laborious and requires many hands to process the large quantities of vegetables required to last throughout the winter months. They all work together, exchange tips and tighten their relationships through kimjang. Families take turns making kimchi to form closer bonds.

Today, the entire village will get together in one of the houses for the occasion. Together, they will wash the napa cabbage that was pickled in salt the night before and mix in the seasonings that will give kimchi its unique sour-and-spicy flavour. The specific methods and ingredients are transmitted from mother to daughter so that kimjang culture is preserved through the generations.

Since 2013, kimjang has been included in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as an important part of Korean culture, embodying the country’s cooperative and sharing team spirit. Kimjang is a vital cultural asset of a community and worth preserving and celebrating for the rest of humanity. Even though there may be regional differences in the preparation of kimchi, it transcends class, regional and even national borders.

Cultural practices often precede the instauration of national borders and the start of conflict among its citizens. Shared cultural practices may even be a path to reconciliation.

Such hopes materialized in 2018, when the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea decided to work together to submit a joint submission for traditional wrestling as an element of UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Ssirum/Ssireum (wrestling) is a physical game and a popular form of entertainment widely enjoyed all across the Korean peninsula. In the North, two opponents try to push each other to the ground using a satpa (a fabric strap connecting the waist and leg), their torso, hands and legs. Ssirum/Ssireum is distinguished by the use of the satpa and the awarding of a bull to the winner. In the South, Ssirum/Ssireum is a type of wrestling in which two players wearing long fabric belts around their waists and one thigh grip their opponents’ belt and deploy various techniques to send them to the ground. The winner of the final game for adults is awarded an ox, symbolizing agricultural abundance, and the title of ‘Jangsa’.

As an approachable sport involving little risk of injury, Ssirum/Ssireum also offers a means to improve mental and physical health. Koreans are widely exposed to Ssirum/Ssireum traditions within their families and local communities: children learn the wrestling skills from family members; local communities hold annual open wrestling tournaments; its instruction is also provided in schools.

Following UNESCO’s mediation, the two States Parties agreed for their respective nomination files to be jointly examined by the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in November 2018. UNESCO welcomed this initiative of regional cooperation and, through a historic decision, inscribed "Traditional Korean wrestling (Ssirum/Ssireum)" on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, as a joint inscription from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea. While the Lists of the Convention include several examples of multinational nominations prepared by several States (from couscous to the art of falconry and the Mediterranean diet), the coming together of the two States Parties for the joint inscription of Korean traditional wrestling by the Committee is unprecedented. It marks a highly symbolic step on the road to inter-Korean reconciliation. It is also a victory for the longstanding and profound ties between both sides of the inter-Korean border, and for the role cultural diplomacy may have in international relations.

It was the time when the women would gather and gossip. There would be matchmaking. There would be some marriages that came about during the time of kimchi making.

Promoting culture in a post-COVID-19 world

The cultural and creative industries are among the fastest growing sectors in the world. With an estimated global worth of US$ 4.3 trillion per year, the culture sector now accounts for 6.1 per cent of the global economy. They generate annual revenues of US$ 2,250 billion and nearly 30 million jobs worldwide, employing more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector. The cultural and creative industries have become essential for inclusive economic growth, reducing inequalities and achieving the goals set out in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

The adoption of the 2005 Convention for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions was a milestone in international cultural policy. Through this historic agreement, the global community formally recognized the dual nature, both cultural and economic, of contemporary cultural expressions produced by artists and cultural professionals. Shaping the design and implementation of policies and measures that support the creation, production, distribution of and access to cultural goods and services, the 2005 Convention is at the heart of the creative economy.

Recognizing the sovereign right of States Parties to maintain, adopt and implement policies to protect and promote the diversity of cultural expression, both nationally and internationally, the 2005 Convention supports governments and civil society in finding policy solutions for emerging challenges.

Based on human rights and fundamental freedoms, the 2005 Convention ultimately provides a new framework for informed, transparent and participatory systems of governance for culture.

A constant rethinking of culture and heritage

The history of UNESCO bears witness to the deep transformation of the concept of culture over the past decades. From global Conventions mostly dealing with building and stones in the 60’s and 70’s, the international cooperation opened new fronts for the protection and promotion of culture, including intangible cultural heritage, cultural diversity and creative economy. The definition of "culture" was spearheaded by the committee led by former UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuellar and the Mondiacult Conference in 1982. In 2022, the global Mondiacult conference is expected to take stock of progress made in the past 40 years in cultural policies, and re-imagine its future in a post-COVID-19 world.

Have a look at these World Heritage sites

The 30,000-kilometre-long road system was built by the Inca Empire across mountains, valleys, rainforests and deserts to link the Inca capital, Cuzco, with distant areas of the empire, from the Amazon to the Andes. Thanks to its sheer scale, Qhapaq Ñan is a unique achievement of engineering skills, highlighting the Incas' mastery of construction technology.

The granting of World Heritage status in 2019 has made its trail – which every year sees thousands of visitors on their way to the area’s archaeological sites such as Machu Picchu in Peru – eligible for much-needed restoration funds.

Borobudur Temple Compound

Borobudur is the largest Buddhist temple in the world and one of the great archaeological sites of Southeast Asia. This imposing Buddhist temple, dating from the 8th and 9th centuries, is located in central Java. It was built in three tiers: a pyramidal base with five concentric square terraces, the trunk of a cone with three circular platforms and, at the top, a monumental stupa. The walls and balustrades are decorated with fine low reliefs, covering a total surface area of 2,500 m 2 . Around the circular platforms are 72 openwork stupas, each containing a statue of the Buddha. The monument was restored with UNESCO's help in the 1970s.

Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan

This cultural landscape was simultaneously inscribed on the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2003. The property is in a fragile state of conservation, having suffered from abandonment, military action and dynamite explosions. Parts of the site are inaccessible due to the presence of anti-personnel mines.

Related items

- Lists and designations

- Intangible cultural heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Diversity of Cultural Expressions-2005 Convention

- Intangible Cultural Heritage-2003 Convention

- Underwater Cultural Heritage-2001 Convention

- World Heritage 1972 Convention

- Fight Illicit Trafficking-1970 Convention

- Armed Conflict and Heritage-1954 Convention

- Culture & Sustainable Development

- UNESCO Creative Cities Network

- FROM THE EDITOR

Which cultural sites should be preserved—and how?

As we go behind the scenes of the herculean effort to restore Notre Dame Cathedral, we also confront thorny questions about cultural heritage sites.

Cultural heritage sites are a nonrenewable resource. When they disappear, they’re gone forever, a loss akin to the extinction of species.

Today architectural and archaeological heritage sites are being destroyed or imperiled at an alarming rate . They’re threatened by rising seas ( Venice ), pollution ( the Taj Mahal ), overtourism ( Angkor Wat ), encroaching development (the Pyramids at Giza ), conflict ( Syria’s ancient city of Palmyra ) …

And by accidents.

In this issue , we explore the herculean efforts to rebuild the roof and spire of Notre Dame Cathedral , part of the Banks of the Seine UNESCO World Heritage site in Paris. Before it was wracked by fire in spring 2019 , the landmark drew some 12 million visitors a year. We’ll take you behind the scenes of the rebuilding, through the work of photographer Tomas van Houtryve , writer Robert Kunzig, and artist Fernando Baptista . You’ll see debris cleared, chapels restored, statuary saved.

You’ll also confront thorny questions about cultural heritage sites. As Kunzig writes , “What part of the past is worth preserving and transmitting to posterity? What duty do we owe the creations of our ancestors, what strength and stability do we draw from their presence—and when, on the contrary, do they become a lead weight, preventing us from projecting ourselves into the future?”

Humankind has answered that query differently in different places.

In Dresden, Germany, the Frauenkirche was an 18th-century baroque church whose bell-shaped dome was a landmark. In February 1945, one of the most destructive Allied bombing attacks of World War II killed an estimated 25,000 people and reduced the city to rubble. As Dresden, then in East Germany, slowly rebuilt after the war, the Frauenkirche remained in ruins. But after German reunification, the church was reconstructed using many of its original stones, as a statement of peace and harmony.

Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church , better known as the Gedächtniskirche, also fell to bombing but met a different fate. Its spire has been left a ruin on purpose, to be what Germans call a mahnmal —a “warning monument” against war and destruction.

Like the Frauenkirche, Notre Dame is being rebuilt as close as possible to how it was before, including using the original, toxic metal—lead—for the roof. That choice was controversial, as future choices are bound to be in the debate about how to restore and maintain historic buildings.

We at National Geographic don’t claim to have the “right” answers on preservation; there may not even be right answers. What we will do is continue to monitor the care of cultural heritage sites, as a matter of significance to humanity’s past, present, and future.

Thank you for reading National Geographic.

This story appears in the February 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Related Topics

- HISTORIC PRESERVATION

- FIRE FIGHTING

You May Also Like

Everything we thought we knew about the ancient Maya is being upended

When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?

Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

See Spain’s fabled Alhambra as few have ever before

- Environment

- Paid Content

- Photography

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Teaching and learning of cultural heritage: engaging education, professional training, and experimental activities.

1. Cultural Heritage and Education, a Brief Introduction

- accessibility (physical, socio-economic, sensorial, cognitive);

- communication (as a subsequent process to the cultural heritage recognition);

- participation (everyone has the right to freely participate in the community’s cultural life, enjoy the arts and share in scientific advancement and its benefits) [ 9 , 10 ].

Cultural Heritage and Professional Figures

- being able to conduct research and collect information, not only of a historical nature, but all that contributes to the Cultural Property description;

- being able to conduct a preliminary examination of the heritage and its environment data, the executive techniques and the constitutive materials of both original and possible interventions and evaluation of the degradation conditions and the interactions between the work and its context;

- to be aware of the various phases of the intervention to be performed in order to plan competent phases at the appropriate time;

- know how to choose the proper instrumentation and equipment for the interventions/activities to be carried out;

- control the correct execution of the activities and verify the quality of the results;

- know how to manage the activities, taking care of all aspects, including administrative and worksite aspects;

- be able to document the results in ‘technical-specific’ venues and others, not necessarily composed of an audience of insiders.

2. Cultural Heritage Education: Universities and Summer Schools

2.1. context, 2.2. methods, 2.3. education and learning, 2.4. student evaluation and legacy, 3. cultural heritage education: primary and secondary school, 3.1. upper secondary education and professional paths, 3.2. primary and low-level secondary school, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions.

- on the initiatives to be undertaken;

- on the sharing of existing system actions at the national level;

- on confirming the relevance of cooperation;

Author Contributions

Institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

| 1 | ]. |

- Cultural Heritage|UNESCO UIS. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/cultural-heritage (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- The 17 GOALS|Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- La Costituzione. Available online: https://www.senato.it/sites/default/files/media-documents/COST_INGLESE.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Educazione. Direzione Generale Educazione, Ricerca e Istituti Culturali. Available online: https://dger.beniculturali.it/educazione/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Piano Nazionale per l’Educazione al Patrimonio. Available online: https://dger.beniculturali.it/educazione/piano-nazionale-per-leducazione-al-patrimonio/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Ministero dell’Istruzione—Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Legge n.107 del 13 luglio 2015 la “Buona Scuola”. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/-/legge-107-del-maggio-2015 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Di Paolo, M. Educare al Patrimonio Culturale Nell’era digitale. BRICKS 2018 , 8 , 26–33. Available online: http://www.rivistabricks.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018_3_04_DiPaolo.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- IV Piano Nazionale per l’Educazione al Patrimonio Culturale 2021. Available online: https://dger.beniculturali.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Piano-Nazionale-per-lEducazione-al-patrimonio-2021.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Senato della Repubblica. 2018. Available online: https://www.senato.it/application/xmanager/projects/leg18/file/DICHIARAZIONE_diritti_umani_4lingue.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Convenzione Quadro del Consiglio d’Europa sul Valore del Patrimonio Culturale per la Società, Faro il 27 Ottobre 2005. Available online: https://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/DF/338231.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Della Torre, S. (Ed.) La Conservazione Programmata del Patrimonio Storico Architettonico. Linee Guida per il Piano di Manutenzione e il Consuntivo ; Guerini e Associati: Milano, Italia, 2005; ISBN 88-8335-359-5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moioli, R.; Baldioli, A. (Eds.) Conoscere per Conservare. Dieci Anni per la Conservazione Programmata ; Il Giornale dell’Arte per Fondazione Cariplo: Torino, Italy, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Distretti Culturali. Available online: http://www.distretticulturali.it/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Monumentenwacht. Available online: https://www.monumentenwacht.be/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Meiping, W.U.; Van Laar, B. The Monumentenwacht model for preventive conservation of built heritage: A case study of Monumentenwacht Vlaanderen in Belgium. Front. Archit. Res. 2021 , 10 , 92–107. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maintain Our Heritage. Available online: https://www.maintainourheritage.co.uk/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- CHANGES (Changes in Cultural Heritage Activities: New Goals and Benefits for Economy and Society). Available online: http://www.changes-project.eu/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Uzzell, D. Interpreting our Heritage: A Theoretical Interpretation. In Contemporary Issues in Heritage and Environmental Interpretation: Problems and Prospects ; Uzzell, D., Ballantyne, R., Eds.; Stationery Office: London, UK, 1998; pp. 11–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Overtourism, Perché se Ne Parla Troppo e Non è il Vero Problema Italiano. Available online: https://www.econopoly.ilsole24ore.com/2019/09/09/overtourism-italia/?refresh_ce=1 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Ablett, P.; Dyer, P. Heritage and Hermeneutics: Towards a Broader Interpretation of Interpretation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009 , 12 , 209–233. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arena, G. I Custodi Della Bellezza. Prendersi Cura Dei Beni Comuni. Un Patto per l’Italia Fra Cittadini e Istituzioni ; Tourting: Milano, Italy, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Achille, C.; Fassi, F.; Mandelli, A.; Fiorillo, F. Surveying cultural heritage: Summer school for conservation activities. Appl. Geomat. 2018 , 10 , 579–592. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- MUR Ministero Università e Ricerca, Lauree e Lauree Magistrali. Available online: https://www.mur.gov.it/it/aree-tematiche/universita/offerta-formativa/lauree-e-lauree-magistrali (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Guida Alle Professioni dei Beni Culturali—Art. 9 bis del Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio. Available online: https://professionisti.beniculturali.it/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Centro Studi Orientamento. Available online: www.cestor.it/atenei/guida.htm (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università Degli Studi di Padova, Dip. Beni Culturali: Archeologia, Storia dell’Arte, del Cinema e della Musica. Available online: www.beniculturali.unipd.it/www/corsi/summer-schools (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna Summer e Winter Schools. Available online: https://beniculturali.unibo.it/it/didattica/summer-e-winter-schools (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università di Ferrara, Summer 2022, after the Damages, International Summer School. Available online: www.afterthedamages.com/summer-school-2022-edition/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Scuola di specializzazione in Beni Storico Artistici. Available online: https://www.unibo.it/it/didattica/scuole-di-specializzazione/scuole-di-specializzazione-non-mediche/beni-storici-artistici (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Storico-Artistici. Available online: https://offertaformativa.unicatt.it/sds-scuole-di-specializzazione-beni-storico-artistici (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università di Roma Sapienza, Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Storico Artistici. Available online: http://dassspecializzazione.uniroma1.it/la-scuola/offerta-didattica-e-formativa (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università Degli Studi di Milano la Statale, Scuola di Specializzazione di Beni Storico Artistici. Available online: www.unimi.it/it/corsi/corsi-post-laurea-e-formazione-continua/scuole-di-specializzazione-catalogo-corsi/catalogo-scuole-di-specializzazione-altre-aree (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Università Degli Studi di Milano Bicocca, Patrimonio Immateriale Nell’Innovazione Socio-Culturale. Available online: https://www.unimib.it/didattica/offerta-formativa/dottorato-ricerca/corsi-dottorato/patrimonio-immateriale-nellinnovazione-socio-culturale (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Fondazione Scuola Beni Attività Culturali. Available online: https://www.fondazionescuolapatrimonio.it/offerta-formativa/corso-scuola-del-patrimonio/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Ministero della Cultura, Direzione Generale Educazione, Ricerca e Istituti Culturali. Available online: https://dger.beniculturali.it/formazione/test_elenco_corsi/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- European Education Area Quality Education and Training for All. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/it/education-levels/higher-education/inclusive-and-connected-higher-education/european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Robinson, B.; Schaible, R.M. Collaborative Teaching. Coll. Teach. 1995 , 43 , 57–59. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nevin, A.I.; Thousand, J.S.; Villa, R.A. Collaborative teaching for teacher educators—What does the research say? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009 , 25 , 569–574. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aicardi, I.; Chiabrando, F.; Lingua, A.; Noardoa, F. Recent trends in cultural heritage 3D survey: The photogrammetric computer vision approach. J. Cult. Herit. 2018 , 32 , 257–266. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fassi, F.; Perfetti, L. Backpack mobile mapping solution for DTM extraction of large inaccesible space. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019 , XLII-2/W15 , 473–480. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Perfetti, L.; Fassi, F. Handheld fisheye multicamera system: Surveying meandering architectonic spaces in open-loop mode—Accuracy assessment. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022 , XLVI-2/W1 , 435–442. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Teruggi, S.; Fassi, F. Mixed reality content alignment in monumental environments. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022 , XLIII-B2-2022 , 901–908. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Achille, C.; Fassi, F.; Lombardini, N.; Gaudio, F.; Galbusera, L. Survey of the archeological site of Nemi. A training experience. In XXIII Symposium CIPA ; Faculty of Civil Engineering, Prague University: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011; ISBN 978-80-01-04885-6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Achille, C.; Fassi, F.; Marquardt, K.; Cesprini, M. Learning Geomatics for Restoration: ICOMOS Summer School in Ossola Valley. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017 , XLII-5/W1 , 631–637. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ullman, S. The interpretation of structure from motion. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1979 , 203 , 405–426. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- UNI 11182:2006. Beni Culturali—Materiali Lapidei Naturali Ed Artificiali—Descrizione della Forma di Alterazione—Termini e Definizioni. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-11182-2006 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Salerno, R. Digital Technologies for “Minor” Cultural Landscapes Knowledge: Sharing Values in Heritage and Tourism Perspective. In Geospatial Intelligence: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications ; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1645–1670. ISBN 9781522580553. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Village Laboratory. Ghesc un Borgo per imparare. In Quaderni di Ghesc; 2010. Available online: https://12d76778-d4fa-f631-1dfb-3cb9e533b7dc.filesusr.com/ugd/73b74a_03fec9b1a81a566cfbd80644b0431915.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Apollonio, F.I.; Gaiani, M.; Tondelli, S.; Achille, C.; Fiorillo, F. Resilient techniques and methods to support a resilient lifecycle of villages and neighborhoods. In Villages et Quartiers à Risque D’Abandon. Stratégies Pour la Connaissance, la Valorisation et la Restauration ; Hadda, L., Mecca, S., Pancani, G., Carta, M., Fratini, F., Galassi, S., Pittaluga, D., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 17–34. ISBN 978-88-5518-537-0. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro, 2017. Ministero dell’Istruzione e dell’Università e della Ricerca. Available online: http://www.alternanza.miur.gov.it/cos-e-alternanza.html (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Linee Guida dei Percorsi per le Competenze Trasversali e per l’Orientamento. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/web/guest/-/linee-guida-dei-percorsi-per-le-competenze-trasversali-e-per-l-orientamento (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Casonato, C.; Di Blas, N.; Fabbri, M.; Ferrari, L. Little-Known Heritage and Digital Storytelling. School as Protagonist in the Rediscovery of the Locality. In Design Thinking and Innovation in Learning ; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2021; pp. 5–24. ISBN 978-1-80071-109-9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Casonato, C.; Vedoà, M. Heritage and Tourism Education in Fragile Landscape. Enhancing the Image of Suburbia. Img J. 2021 , 3 , 64–89. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bonfanti, A. A Centonove Passi Dalla Chiesa di Laorca (Fede e Storia Intorno Alle Grotte) ; Tipo-Litografia Alfredo Colombo: Lecco, Italy, 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rizzi, G. Visitare un Bene Culturale a Distanza. Tour Virtuale del Complesso Monumentale di Laorca (LC). Master’s Thesis, School of Architecture Urban Planning Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 28 April 2021. Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/174313 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- LaorcaLAB. Associazione di Promozione Sociale. Available online: https://www.laorcalab.org/laorcalab/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Il Cimitero di Laorca. Available online: https://www.laorcalab.org/tour-virtuale-cimitero-laorca/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Fiorillo, F.; Rizzi, G.; Achille, C. Learning through Virtual Tools: Visit a Place in the Pandemic Era. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021 , XLVI-M-1 , 225–232. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Villa, D. Social media per l’educazione al Patrimonio del sito Unesco Sacri Monti di Piemonte e Lombardia. In Ambienti Digitali per L’Educazione All’Arte e al Patrimonio ; Luigini, A., Panciroli, C., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy; pp. 282–293. ISBN 9788891773333.

- Di Blas, N.; Paolini, P.; Sabiescu, A. Collective digital storytelling at school as a whole-class interaction. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC 10), New York, NY, USA, 9–12 June 2010; pp. 11–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rahiem, M.D.H. Storytelling in early childhood education: Time to go digital. ICEP 2021 , 15 , 4. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kang, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S. Kids in Fairytales: Experiential and Interactive Storytelling in Children’s Libraries. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1007–1012. Available online: https://youngwoon.github.io/assets/publications/kids_chiw2015.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022). [ CrossRef ]

- IDMS 18 Aprile 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLb5l4s3ZSa2IyNXq62IXKxyWlJ7lhW3yw (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- International Day for Monuments and Sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/focus/18-april-international-day-for-monuments-and-sites/92257-looking-back-on-18-april-2021-thank-you-so-much (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- ICOMOS IDMS 2021|ICOMOS Italia—CIPA-HD—Legami di Comunità. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/focus/18-april-international-day-for-monuments-and-sites (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Next Generation EU. Available online: https://europa.eu/next-generation-eu/index_it (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- PNRR Cultura Ministero della Cultura. Available online: https://pnrr.cultura.gov.it/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- ICR. Available online: http://www.iscr.beniculturali.it/pagina.cfm?usz=4 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- OPD. Available online: http://www.opificiodellepietredure.it/index.php?it/79/scuola (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Decreto Legislativo 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42. “Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, ai Sensi dell’Articolo 10 della Legge 6 Luglio 2002, n. 137. Available online: https://web.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/04042dl.htm (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Summer Schools Nemi. Available online: https://www.sitech-3dsurvey.polimi.it/?page_id=318 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Summer Schools Ghesc. Available online: https://www.sitech-3dsurvey.polimi.it/?page_id=328 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Associazione Canova. Available online: https://www.canovacanova.com/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Summer Schools Domodossola. Available online: https://www.sitech-3dsurvey.polimi.it/?page_id=3149 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Sacro Monte Domodossola. Available online: https://www.sacrimonti.org/sacro-monte-di-domodossola (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- The Sacri Monti of Piedemont and Lombardy. Available online: https://www.sacrimonti.org/en/home (accessed on 25 July 2022).

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Achille, C.; Fiorillo, F. Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities. Heritage 2022 , 5 , 2565-2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030134

Achille C, Fiorillo F. Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities. Heritage . 2022; 5(3):2565-2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030134

Achille, Cristiana, and Fausta Fiorillo. 2022. "Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities" Heritage 5, no. 3: 2565-2593. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030134

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Our Mission & Values

- Staff & Board

- Privacy Policy

- World Monuments Watch

- 2022 World Monuments Watch

- Featured Projects

- Explore Sites & Projects

- Attend an Event

- Travel with WMF

- Jewish Heritage Program

- Ukraine Heritage Response Fund

- Heritage from Home

- Support Our Work

- More Ways to Give

- International Council

- Planned Giving

- Institutional Giving

- Crisis Response

Stay connected

Looking to the Future: Global Challenges to Cultural Heritage Preservation

In this article from World Monuments Fund's 2021 Watch Magazine, WMF Vice President of Programs Jonathan Bell takes stock of our cumulative impact over these past five and a half decades and considers how best to enhance our efforts protecting and supporting the world’s most incredible cultural landscapes, architectural marvels, and places of shared significance.

After decades working to underscore, preserve, and rehabilitate key cultural heritage in countries around the world from Albania to Zimbabwe, our commitment to our planet’s monuments of cultural expression and human ingenuity is as strong as ever. We must, however, recognize that the global challenges facing the cultural heritage we endeavor to protect have changed and created a new landscape across which World Monuments Fund must operate and demonstrate relevance. The global pandemic that has plagued the world through most of 2020 has drastically changed the way we all work and play.

Since the international recognition of the novel coronavirus at the beginning of this year, we have witnessed unprecedented changes to the interactions between people and places of significance. With fewer visits to historic buildings and archaeological sites resulting in a dramatic loss of revenue for these places and their adjacent communities, the critical link between tourism and local economies has become painfully apparent. At the same time, significantly diminished travel and sparse crowds have led the way to cleaner air and waterways, welcomed frolicking wildlife into the world’s urban centers, and replenished the sense of place and idyllic beauty once enjoyed by local residents without the canopy of mass tourism.

Amid the throes of this pandemic, continued police violence toward people of color in the United States and the effective organizing of the Black Lives Matter movement sparked an unprecedented worldwide recognition of painful histories embodied in the statues and monuments erected in public squares and before town halls around the world. Spurred on by social media networks and covered by traditional media, the groundswell call to remove these monuments associated with historic injustice has helped showcase that celebrated heritage often represents privilege. Some stories are told in stone and bronze for the world to see, but many others lack recognition and remain unseen and unheard.

While our relationships with our cultural heritage evolved over the past year, changing rainfall patterns, intensifying storms, and rising temperatures continued to pose challenges. The pervasive nature of climate change means that no building, landscape, archaeological site, or adjacent community is spared the need to adapt and develop solutions to this invisible and unpredictable force. Tied to changing weather patterns is an increase in disasters from flooding, sustained high winds, unusual temperature extremes, and drought, all of which present distinct challenges for the places and communities where World Monuments Fund works.

As we consider the events of this past year and our priorities for the future, we recognize that World Monuments Fund must act as an agent of change. We remain committed to working with local partners and communities to protect the world’s most important places; this is our mission. Additionally, we must ensure our impact is not only measured in finished projects, but in the cumulative effect of outcomes on some of the world’s most pressing challenges. By curating our portfolio of projects such that multiple places can develop viable mitigation and adaptation strategies to similar challenges and threats, World Monuments Fund can employ a multiplier effect that has widespread and lasting impact.

To this end, we have identified three global challenges that will help shape our portfolio of projects, focus our resources, and coalesce our individual efforts into far-reaching solutions. By helping partners develop sound local and regional tourism strategies, we will work to mitigate the negative impacts and harness the economic and social potential of imbalanced tourism. In strengthening our commitment to work with unrecognized heritage places and integrate diverse perspectives, we will bolster the role of underrepresented heritage in global discussions and preservation decision-making. Through developing site-specific solutions to changing weather patterns, we will underscore the threat that climate change represents and contribute to adaptation strategies around the world.

Imbalanced Tourism

The adage that “tourism is a doubleedged sword” is well known to preservation professionals, since the field has long struggled to promote patterns of visitation that can sustainably support heritage places with adequate revenue and minimally impact the physical fabric or sense of place. As many of us have experienced, popular destinations are quickly overrun and the visitor experience significantly diminished by large crowds that leave their mark on the monuments, exasperate the local community, and support the local economy with mixed results. For some places, the promised economic development never comes, as visitors are few or inconsistent and revenue may be funneled to external entities or local powerbrokers through prepaid packages and foreign tour operators. At other locations, tourism leads to rampant growth that gentrifies neighborhoods, encourages new development, and forever changes the composition of local communities and the character of the heritage.

One strategy lies in developing and coordinating a wide array of visitation opportunities at a regional scale, as opposed to focusing on individual sites. Such an approach requires working closely with local and regional authorities, resident communities, and site managers to coordinate decisionmaking and tourism promotion. World Monuments Fund is developing this approach at 2020 World Monuments Watch sites Bennerley Viaduct (UK) and Canal Nacional (Mexico), working closely with local community-based organizations to enhance and highlight incredible infrastructure that shapes the landscape and provides a wide variety of recreation and tourism opportunities. In the Jewish Mahalla of Bukhara (Uzbekistan) and the historic neighborhood of Axerquía in Córdoba (Spain), a similar approach at the neighborhood levels will help strengthen interest in and visitation of traditional houses and streetscapes that epitomize the local vernacular architecture and culture.

Another tactic that has flourished throughout the pandemic is digital tourism—experiencing the world’s cultural treasures from the comfort of your own home through the marvel of technology. World Monuments Fund is integrating digital documentation and the development of virtual experiences to raise awareness about the places we work and share the wonder and rich history with a broad audience. We have already developed interactive online experiences for places like San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas (Peru), as well as an award-winning virtual visit to La Garma cave (Spain). This approach not only allows larger numbers of people to “visit” these incredible places, but contributes to their protection by preventing high-volume tourism that could be detrimental to their survival. Altogether, these approaches support the development of a more sustainable tourism that not only bolsters destinations and resident communities, but also provides for a richer and more fulfilling visitor experience. World Monuments Fund will continue to work closely with our partners and stakeholders on the ground to develop viable visitor management strategies that distribute tourism at a regional scale and help reach new audiences and supporters of cultural heritage. A commitment to balanced tourism enhances our efforts to support the places we work.

Underrepresented Heritage

As the debate over monuments this year has clearly demonstrated, power and privilege are often tied to celebrated cultural heritage. The architectural marvels of the past that regale throngs of visitors with stories of pageantry and conquest frequently embody rarely recounted stories of servitude, subjugation, and exclusion. These are the stories of the disempowered communities whose land was stolen, who labored as enslaved people, or who paid oppressive taxes to fund the opulence and splendor of many feted destinations. The artistic achievement is lauded, but the associated sacrifice is often ignored. Despite recent efforts at historic sites to interpret these stories and provide a richer narrative, diverse perspectives and stories of injustice are rarely integrated. Moreover, there are many places of significance that do not appear on any sanctioned list and lack broad support for protection because they have been sidelined for generations. These heritage places hold incredible importance for the communities that value them and often represent unique facets of human ingenuity, creativity, and artistry that are otherwise unrecognized. Their demise would be an irrevocable loss for humanity.

Encouraging inclusion of diverse perspectives and narratives is a crucial path forward to recognizing and protecting humanity’s rich heritage. The most iconic historic places comprise countless unheard stories and unrecognized contributions by disenfranchised communities. World Monuments Fund renews our commitment to the heritage of underrepresented groups exemplified through previous work in Essaouira (Morocco) and with Voices of Alabama (United States). In these projects, the narratives of minority communities were recorded and disseminated to raise awareness of the significant role their heritage plays in local identity. Current projects at the Woolworth Building in San Antonio (United States) and the Mam Rashan Shrine in Sinjar (Iraq) underscore the wealth and distinctiveness of so many underrepresented heritage sites and the threats they face, ranging from lack of recognition to targeted destruction associated with genocide.

World Monuments Fund will continue to engage a wide variety of stakeholders and capture divergent perspectives as an essential component of our work. Through close collaboration with local communities, we commit to highlighting the wonder of humanity’s rich accomplishments while denouncing past and current injustice. Ensuring that recognized cultural heritage embodies our diversity and portrays the complexities of history enhances its relevance for communities everywhere.

Climate Change

Our built heritage has always contended with the elements. Crucial components of local architecture, sense of place, and even cultural mores have developed over centuries in response to climate. In recent years, we have seen weather patterns change around the globe such that temperatures are shifting, sea levels are rising, and storms are intensifying. Communities and the places of importance that help nourish them must adapt to survive. Despite the concept of the monument as a beacon for the ages, extreme temperatures, violent winds, and excessive or inadequate rainfall represent new threats to their longevity. Year after year, increased flooding and wildfires damage and even destroy historic sites in countless nations around the world. The global nature of our changing climate underscores the need for pragmatic, replicable strategies to safeguard our cultural heritage.

A principal approach lies in the development of adaptation strategies that provide historic and cultural resources with the ability to withstand climatic changes: shed and drain larger volumes of water; withstand stronger winds; tolerate more extreme temperatures; and endure drought. In many cases, traditional natural resource management and building techniques already provide the answers and simply require renewal and strengthening. World Monuments Fund’s past projects in Kilwa (Tanzania) and current project at a 2020 Watch site in Vijayapura, Karnataka (India), integrate rehabilitation of traditional land and water management systems as a strategy to protect and revitalize the historic sites. In other cases, such as Wat Chaiwatthanaram (Thailand), modern engineering solutions and drainage plans have been implemented to protect this Buddhist temple complex from flood events exacerbated by a changing climate.

Cultural heritage is also emblematic of the urgency of climate change—iconic places are dramatically swallowed by the sea or destroyed by gale force winds. Places of importance can serve as rallying cries for global coordination and commitment to the climate crisis. With our projects at Blackpool Piers (United Kingdom) and the Coral Stone Mosques (Maldives), World Monuments Fund has aimed to highlight the plight of our heritage in the face of climate change and work closely with local stakeholders and international institutions to develop strategies to save them.

We have the duty to protect the world’s cultural heritage from the immediate effects of climate change and the opportunity to emphasize the need for action through work at these places. World Monuments Fund is committed to playing a key role in both arenas, working closely with local and international partners to find solutions to immediate needs and to contribute to long-term mitigation. Our approach is to learn from our work and disseminate the lessons of successful strategies and failed tactics alike to improve our global capacity to safeguard our places of greatest significance and the communities that turn to them for affirmation, solace, and the promise of cultural resilience.

To read more stories from the 2021 Watch Magazine, click here .

Volunteers’ Week 2024: get 15% off your new MA membership until 9 June

- How we are run

- Our strategy

- Our statements

- Our funders

- Annual Reports

- Our committees

- Our policies

- Code of Ethics

- Anti-racism

- Collections

- Decolonising museums

- Learning and engagement

- Museums Change Lives

- Museums for Climate Justice

- Volunteers’ Week 2024

- Associateship (AMA)

- Museum Essentials

- Fellowship (FMA)

- Competency Framework

- Redundancy Hub

- Wellbeing Hub

- Career Conversations

- Entering the sector

- Conference 2024

- Forthcoming events

- Watch our webinars

- Conference 2023 content

- Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund

- Benevolent Fund

- Beecroft Bequest

- Mindsets + Missions

- In practice

- Watch and listen

- Museums Journal

Why cultural heritage matters now more than ever

Last month the Ivankiv Museum, located around 50 miles north of Kyiv, was reportedly burned by Russian forces, leading to the loss of several paintings by local folk artist Maria Prymachenko. A local man ran into the building and saved about 10 of the 25 Prymachenko works stored there.

The artist’s great-granddaughter said that “the museum was the first building in Ivankiv that the Russians destroyed… I think it is because they want to destroy our Ukrainian culture...”

We have seen paintings, icons, books and statues hurried into storage, and we cannot but think of the bravery of museum curators and directors across the world, in Afghanistan, Syria, Lebanon, and countless other places.

UNESCO director-general Audrey Azoulay has stated in the context of Ukraine that “we must safeguard this cultural heritage as a testimony of the past but also as a vector of peace for the future, which the international community has a duty to protect and preserve for future generations.”

The palpable value of culture in war is a reminder that when we talk about cultural heritage, we are talking about what lies at the very heart of identity and values, for good and for ill.

At the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) we are proud to be working with DCMS on the Cultural Heritage Capital programme , which looks to publish research, data, guidance and tools to help organisations make a stronger case for investment in culture and heritage assets – which are so vital to our lives and identities.

Cultural heritage can enrich our lives in so many ways. Here, I explore why cultural heritage – enriched by research – must be valued in our quest for a better future.

The power of stories

Humans have developed a highly sophisticated language with which to tell stories and to memorialise those stories. We all know and feel the power of place and object. Objects and places acquire value through our telling stories about them – and embedding them in our stories about ourselves.

But equally, the negative consequences of bad storytelling are all around us. They are visible in the consequences of a story we told ourselves about our mastery over nature and our right to use its resources without limit. It’s visible in the stories we have systematically not told, the people whose words and lives we have occluded and the impact on educational attainments and the underestimation of their potential, economic and social.

And it’s playing out in war and devastation. Whatever analysis we eventually agree on to explain the conflict that is raging in Ukraine and Russia, one part will be the hugely damaging legacy of partial, unbalanced, and uncontested stories about culture and heritage which powerful individuals have told to themselves and to others.

That’s why cultural heritage needs to be taken seriously, and its value fully recognised. It’s why we need a better explanation of the balance sheet of culture and heritage capital, which shows that for all its intangibility its direct impact on the world is measurable for good, and that underinvestment in its rich complexity has a massive cost.

Working together

This work demands collaboration. Cultural heritage also has the power to bring together knowledge and ideas from across disciplines and across funders such as DCMS, AHRC, Arts Council England and Historic England.

Only when arts and humanities, heritage science and economics genuinely come together will we find the best way to articulate the social and economic impacts and value for money of culture and heritage, which can then change funding policy.

For me one of the main legacies of this area of work will be that we get to know each other better and work more closely together. We have so much to do.

Conservation science

Let me give an example of the difference funding can make. Recently I was in the science and conservation lab of the V&A. The AHRC has spent over £2m over the past two years to provide new kit, better storage, improved facilities, additional staff and new AHRC-funded collaborative PhDs.

The V&A is using this skill and expertise not only to support its own collection, but to offer loans to others such as the major Donatello exhibition in Florence, and its satellite museums in Stoke-on-Trent and Dundee.

Some may ask, why should we care about the capacity to identify a tiny piece of thread or a trace of vermilion on an old painting? There are many answers to that question but here are some.

This funding is helping V&A improve the sustainability of its buildings.

It is helping pioneer new techniques and technologies – not taking from science but giving to science, from nanotechnology to equipment design. We already seeing equipment providers using this experience to innovate.

And by using this combination of expertise and equipment on its new accessions, the V&A is proactively underpinning the future sustainable conservation of today’s artefacts.

Culture and heritage capital

So when we think about culture and heritage, from how we value it in war, to how we use it in our stories, to the way we fund it and why, we rapidly find ourselves talking about the science of our humanity, the potential for our imagination, the capacity to escape our past and enrich our future.

Those values and outcomes may seem intangible, but they have tangible impacts on our world, and it’s that which we need to capture, rigorously and systematically, to support future funding and future generations.

Christopher Smith is executive chair at the Arts and Humanities Research Council

Leave a comment Cancel reply

You must be signed in to post a comment.

Editorial | Supporting a mixed model

A radical vision for art will counter a reduced cultural infrastructure, deploying a human rights-based lens may help museums address power imbalances.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Special topics in art history

Course: special topics in art history > unit 1, what can be done to protect cultural heritage.

- Organizations and agencies that work to protect cultural heritage

Demand is the driver for looting and destruction

Incorporate the consequences of the global antiquities trade into curriculum, universal and local value, focus on the local, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Essay on Cultural Heritage

Students are often asked to write an essay on Cultural Heritage in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Cultural Heritage

Understanding cultural heritage.

Cultural heritage is the legacy of physical artifacts and intangible attributes inherited from past generations. It includes traditions, languages, and monuments that are important to our identity.

Types of Cultural Heritage