How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

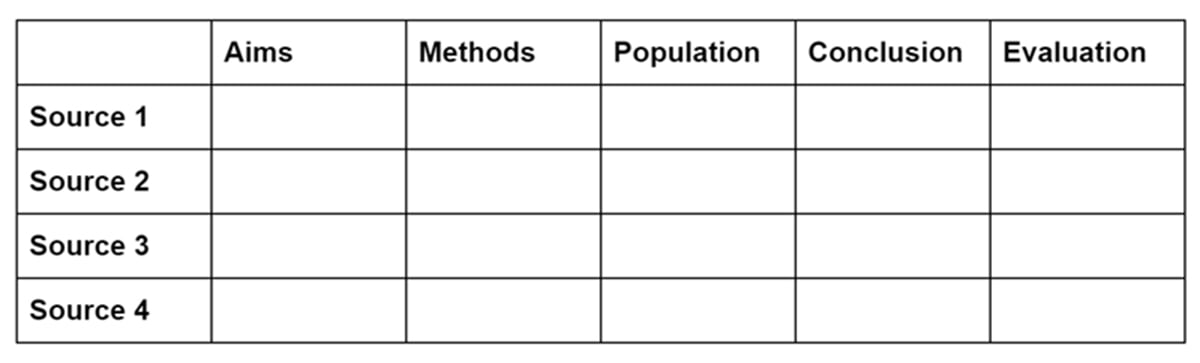

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

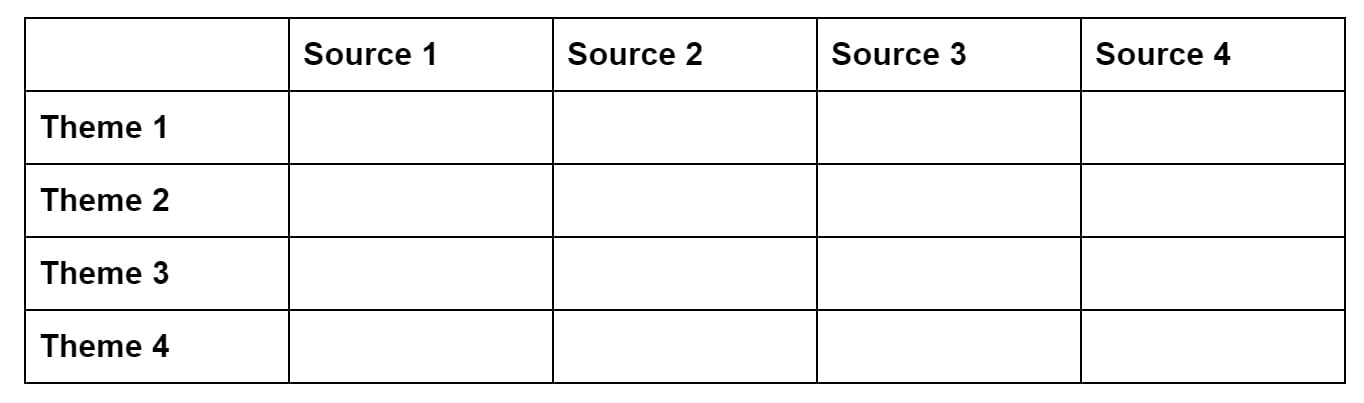

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

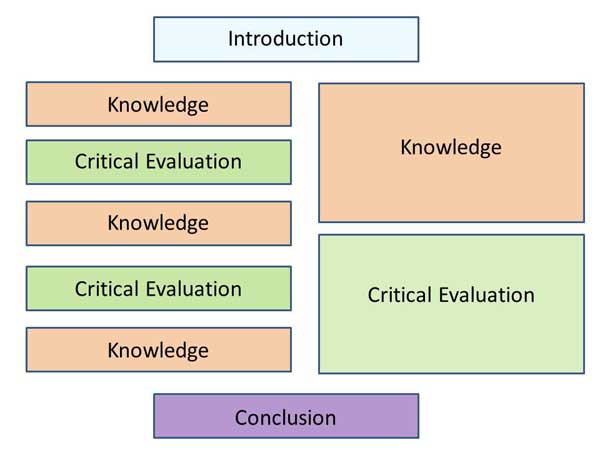

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

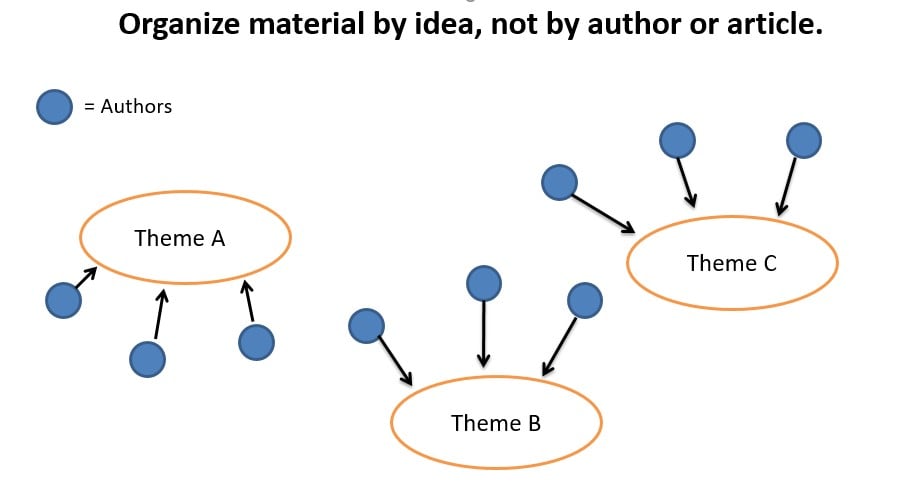

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Meet Our Team

- Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 0. Develop a Protocol

- 1. Draft your Research Question

- 2. Select Databases

- 3. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 4. Write a Search Strategy

- 5. Register a Protocol

- 6. Translate Search Strategies

- 7. Citation Management

- 8. Article Screening

- 9. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 10. Data Extraction

- 11. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Evidence Synthesis Institute for Librarians

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

What are evidence syntheses.

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the next tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

How does a systematic review differ from a traditional literature review.

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 12:12 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

Synthesis in Research: Home

What is synthesis?

Synthesizing information is the opposite of analyzing information. When you read an article or book, you have to pull out specific concepts from the larger document in order to understand it. This is analyzing.

When you synthesize information, you take specific concepts and consider them together to understand how they compare/contrast and how they relate to one another. Synthesis involves combining multiple elements to create a whole.

In regard to course assignments, the elements refer to the outside sources you've gathered to support the ideas you want to present. The whole then becomes your conclusion(s) about those sources.

How do I synthesize information?

Note: These steps offer a guideline, but do what works for you best.

- This is where you really decide if you want to read specific materials

- If you have gathered a substantial amount of literature and reading all of it would prove overwhelming, read the abstracts to get a better idea of the content, then select the materials that would best support your assignment

- Describe and analyze the findings and/or the author's main ideas

- What's the author's message?

- What evidence do they use to support their message?

- What does the author want a reader to understand?

- What is the larger impact of the author's message?

- Compare and contrast the main ideas and other pertinent information you found in each source

- Evaluate the quality and significance of these main ideas

- Interpret the main ideas in the context of your research question or assignment topic

- This is the step where your synthesis of the information will lead to logical conclusions about that information

- These conclusions should speak directly to your research question (i.e. your question should have an answer)

I would like to give credit to Aultman Health Sciences Library. Most of the information used to create this guide is from their English Research libguide .

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 2:29 PM

- URL: https://library.defiance.edu/synthesis

Pilgrim Library :

419-783-2481 , library@ defiance.edu , click the purple "ask us" side tab above.

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Systematic reviews & evidence synthesis methods.

- Schedule a Consultation / Meet our Team

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 1. Develop a Protocol

- 2. Draft your Research Question

- 3. Select Databases

- 4. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 5. Write a Search Strategy

- 6. Register a Protocol

- 7. Translate Search Strategies

- 8. Citation Management

- 9. Article Screening

- 10. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 11. Data Extraction

- 12. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the Types of Evidence Synthesis tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Schedule a Consultation / Meet our Team

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 5:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/evidence-synthesis

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Resources @HSL

- Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

- Quantitative Evidence Synthesis

- Mixed Methods Evidence Synthesis

- Data Extraction

- Quality of Data Review

- Data Bias Risk Analysis

- Cite Sources

Health Sciences Library

Synthesis Definitions

An everyday example of personalized synthesis.

Evaluating Healthcare Decision by Synthesizing Available Evidence

Synthesizing Literature for Research Papers

- Next: Evidence Synthesis Resources @HSL >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 12:23 PM

- URL: https://hslguides.osu.edu/c.php?g=997383

Jump to navigation

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Malaysia

Evidence Synthesis - What is it and why do we need it?

We come across 'evidence syntheses' on an almost day-to-day basis, but do we know what it is and why it's so imporant?

Cochrane Ireland and Evidence Synthesis Ireland are working together to create awareness and increase knowledge and capacity in evidence synthesis methods.

Evidence synthesis, sometimes called “systematic reviews”, involves combining information from multiple studies investigating the same topic to comprehensively understand their findings. This helps determine how effective a particular treatment or drug is, or how people have experienced a particular health condition or treatment. By using evidence synthesis effectively, policymakers, healthcare institutions, clinicians, researchers, and the public can make more informed decisions about health and healthcare.

Watch this short video to learn more about evidence synthesis and why we need it:

This video was created using a user-centred design approach, using members of the public at multiple stages. You can read more about its development in this paper: Development of a video-based evidence synthesis knowledge translation resource: Drawing on a user-centred design approach. Additional Resources:

- Search Cochrane's Plain Language Summaries of health evidence

- Visit the Cochrane Ireland website

- Visit the Evidence Synthesis website

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Synthesis

Synthesis video playlist.

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

Basics of Synthesis

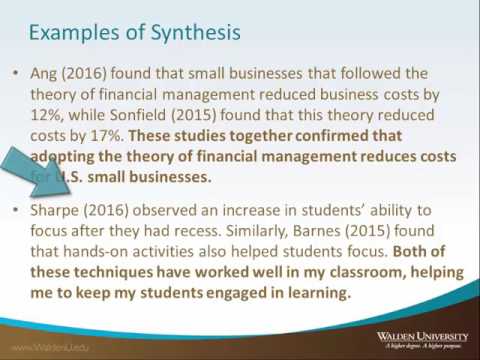

As you incorporate published writing into your own writing, you should aim for synthesis of the material.

Synthesizing requires critical reading and thinking in order to compare different material, highlighting similarities, differences, and connections. When writers synthesize successfully, they present new ideas based on interpretations of other evidence or arguments. You can also think of synthesis as an extension of—or a more complicated form of—analysis. One main difference is that synthesis involves multiple sources, while analysis often focuses on one source.

Conceptually, it can be helpful to think about synthesis existing at both the local (or paragraph) level and the global (or paper) level.

Local Synthesis

Local synthesis occurs at the paragraph level when writers connect individual pieces of evidence from multiple sources to support a paragraph’s main idea and advance a paper’s thesis statement. A common example in academic writing is a scholarly paragraph that includes a main idea, evidence from multiple sources, and analysis of those multiple sources together.

Global Synthesis

Global synthesis occurs at the paper (or, sometimes, section) level when writers connect ideas across paragraphs or sections to create a new narrative whole. A literature review , which can either stand alone or be a section/chapter within a capstone, is a common example of a place where global synthesis is necessary. However, in almost all academic writing, global synthesis is created by and sometimes referred to as good cohesion and flow.

Synthesis in Literature Reviews

While any types of scholarly writing can include synthesis, it is most often discussed in the context of literature reviews. Visit our literature review pages for more information about synthesis in literature reviews.

Related Webinars

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Analysis

- Next Page: Citing Sources Properly

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Meta-synthesis of Qualitative Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Angela J. Dawson 2

1407 Accesses

6 Citations

A meta-synthesis of qualitative health research is a structured approach to analyzing primary data across the findings sections of published peer-reviewed papers reporting qualitative research. A meta-synthesis of qualitative research provides evidence for health care and service decision-making to inform improvements in both policy and practice. This chapter will provide an outline of the purpose of the meta-synthesis of qualitative health research, a historical overview, and insights into the value of knowledge generated from this approach. Reflective activities and references to examples from the literature will enable readers to:

Summarize methodological approaches that can be applied to the analysis of qualitative research.

Define the scope of and review question for a meta-synthesis of qualitative research.

Undertake a systematic literature search using standard tools and frameworks.

Examine critical appraisal tools for assessing the quality of research papers.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Banning JH. Ecological triangulation: an approach for qualitative meta-synthesis. US Department of Education, School of Education, Colorado State University, Colorado; 2005.

Google Scholar

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating (EPPI) Centre, Social Science Research Unit Institute of Education, London 01/09; 2007.

Bayliss K, Starling B, Raza K, Johansson EC, Zabalan C, Moore S, Skingle D, Jasinski T, Thomas S, Stack R. Patient involvement in a qualitative meta-synthesis: lessons learnt. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0032-0 .

Article Google Scholar

Chatfield SL, DeBois K, Nolan R, Crawford H, Hallam JS. Hand hygiene among healthcare workers: a qualitative meta summary using the GRADE-CERQual process. J Infect Prev. 2017;18(3):104–20.

Cherryholmes CH. Notes on pragmatism and scientific realism. Educ Res. 1992;21(6):13–7.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Crandell JL, Voils CI, Chang Y, Sandelowski M. Bayesian data augmentation methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research findings. Qual Quant. 2011;45(3):653–69.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. St Leonards: Sage; 1998.

Dawson AJ, Buchan J, Duffield C, Homer CS, Wijewardena K. Task shifting and sharing in maternal and reproductive health in low-income countries: a narrative synthesis of current evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2013;29(3):396–408.

Dawson A, Nkowane A, Whelan A. Approaches to improving the contribution of the nursing and midwifery workforce to increasing universal access to primary health care for vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0096-1 .

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011.

Elfenbein DM. Confidence crisis among general surgery residents: a systematic review and qualitative discourse analysis. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(12):1166–75.

Fegran L, Hall EO, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H, Ludvigsen MS. Adolescents’ and young adults’ transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: a qualitative metasynthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):123–35.

France E, Ring N, Noyes J, Maxwell M, Jepson R, Duncan E, Turley R, Jones D, Uny I. Protocol-developing meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe). BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0068-0 .

France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Systematic reviews. 2016;5(44). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-13016-10218-13644 . https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0218-4

Franzen SR, Chandler C, Lang T. Health research capacity development in low and middle income countries: reality or rhetoric? A systematic meta-narrative review of the qualitative literature. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012332 .

Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J, Rashidian A. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;10. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2 .

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-28 .

Greenhalgh T, Annandale E, Ashcroft R, Barlow J, Black N, Bleakley A, Boaden R, Braithwaite J, Britten N, Carnevale F. An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ. 2016;352:i563. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i563 .

Guba EG. The paradigm dialog. Newberry Park: Sage; 1990.

Hannes K, Harden A. Multi-context versus context-specific qualitative evidence syntheses: combining the best of both. Res Synth Methods. 2011;2(4):271–8.

Hannes K, Lockwood C. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(7):1632–42.

Hannes K, Lockwood C. Qualitative evidence synthesis: choosing the right approach. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

Hannes K, Macaitis K. A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: update on a review of published papers. Qual Res. 2012;12(4):402–42.

Hannes K, Pearson A. Obstacles to the implementation of evidence-based practice in Belgium: a worked example of meta-aggregation. In: Synthesizing qualitative research: choosing the right approach. Chichester: Wiley; 2012. p. 21–39.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hannes K, Behrens J, Bath-Hextall F. There is no such thing as a one dimensional hierarchy of evidence: a critique and a perspective. Vienna, Austria: Paper presented at the Cochrane Colloquium; 2015.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Hannes K, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper 4: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;In Press, Accepted Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.11.029 .

Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, Hannes K, Harden A, Flemming K, Garside R, Pantoja T, Thomas J, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 6: methods for question formulation, searching and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;In Press, Corrected Proof. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.023 .

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, Noyes J, Booth A, Garside R, Rashidian A. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed .

Martsolf DS, Draucker CB, Cook CB, Ross R, Stidham AW, Mweemba P. A meta-summary of qualitative findings about professional services for survivors of sexual violence. Qual Rep. 2010;15(3):489–506.

Melendez-Torres GJ, Grant S, Bonell C. A systematic review and critical appraisal of qualitative metasynthetic practice in public health to develop a taxonomy of operations of reciprocal translation. Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(4):357–71.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed .

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

Book Google Scholar

Noyes J, Popay J. Directly observed therapy and tuberculosis: how can a systematic review of qualitative research contribute to improving services? A qualitative meta-synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(3):227–43.

Noyes J, Hannes K, Booth A, Harris J, Harden A, Popay J, Pearson A, Cargo M, Pantoja T. Qualitative research and cochrane reviews. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.3.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2015. http://qim.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, Pantoja T, Hannes K, Cargo M, Thomas J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper 2: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;In Press, Corrected Proof. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020 .

Oishi A, Murtagh FE. The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med. 2014;28(9):1081–98.

Oliver K, Rees R, Brady L-M, Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Thomas J. Broadening public participation in systematic reviews: a case example involving young people in two configurative reviews. Research Synthesis Methods. 2015;6(2):206–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1145

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL, Collins KM. Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. Qual Rep. 2012;17(28):1–28.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage; 1997.

Rodríguez-Prat A, Balaguer A, Booth A, Monforte-Royo C. Understanding patients’ experiences of the wish to hasten death: an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016659. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016528 .

Röing M, Holmström IK, Larsson J. A metasynthesis of phenomenographic articles on understandings of work among healthcare professionals. Qual Health Res. 2017;28(2):273–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317719433 .

Sager F, Andereggen C. Dealing with complex causality in realist synthesis: the promise of qualitative comparative analysis. Am J Eval. 2012;33(1):60–78.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer; 2006.

Schreiber R, Crooks D, Stern PN. Qualitative meta-analysis. In: Morse M, editor. Completing a qualitative project: details and dialogue. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1997. p. 311–26.

Seymour KC, Addington-Hall J, Lucassen AM, Foster CL. What facilitates or impedes family communication following genetic testing for cancer risk? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of primary qualitative research. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(4):330–42.

Shaw R. Conducting literature reviews. In: Forreste MA, editor. Doing qualitative research in psychology: a practical guide. London: Sage; 2010. p. 39–56.

Stansfield C, Thomas J, Kavanagh J. ‘Clustering’ documents automatically to support scoping reviews of research: a case study. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(3):230–41.

Thomas J, McNaught J, Ananiadou S. Applications of text mining within systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2011;2(1):1–14.

Thomas J, O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G. Using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in systematic reviews of complex interventions: a worked example. Syst Rev. 2014;3:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-67 .

Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(10):1342–65.

Tomlin G, Borgetto B. Research pyramid: a new evidence-based practice model for occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65(2):189–96.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/471-2288-12-181 .

Voils C, Hassselblad V, Crandell J, Chang Y, Lee E, Sandelowski M. A Bayesian method for the synthesis of evidence from qualitative and quantitative reports: the example of antiretroviral medication adherence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(4):226–33.

Walder K, Molineux M. Occupational adaptation and identity reconstruction: a grounded theory synthesis of qualitative studies exploring adults’ experiences of adjustment to chronic disease, major illness or injury. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(2):225. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2016.1269240 .

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses–Evolving Standards) project. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2(30):1. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02300 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Australian Centre for Public and Population Health Research, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Angela J. Dawson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Angela J. Dawson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Dawson, A.J. (2019). Meta-synthesis of Qualitative Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_112

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_112

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

University of Pittsburgh Library System

- Collections

Course & Subject Guides

A guide to systematic reviews and evidence synthesis service @ uls, evidence synthesis defined, types of evidence synthesis, what type of evidence synthesis is right for you.

- How can the ULS assist you with your Evidence Synthesis?

- What is a Systematic Review and where can you find them?

- What are the steps in a Systematic Review?

- Are there any guidelines or standards for publishing reviews?

- How can I get assistance with a review?

Lead Librarian for Evidence Synthesis

Evidence Synthesis International describes Evidence Synthesis this way...

"Evidence synthesis is the interpretation of individual studies within the context of global knowledge for a given topic. These syntheses provide a rigorous and transparent knowledge base for translating research in decisions. Essential to all evidence syntheses is the use of explicit and transparent methodology in the formation of the questions they address. The transparent methodology encompasses how studies are identified, selected, appraised, analyzed, and the strength of the evidence assessed to answer the questioned posed.

Evidence syntheses methods have been applied to a diverse and growing number of areas. Applications, include: education, crime and justice, international development, health care delivery, health technology assessment, veterinary medicine, pre-clinical drug development and toxicology, food safety, and environmental conservation. As equally diverse as the applications are the organizations that conduct, commission, and utilize the evidence synthesis."

Evidence Synthesis International. (n.d.). What is Evidence Synthesis . Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://evidencesynthesis.org/what-is-evidence-synthesis/

Evidence synthesis refers to any method of identifying, selecting, and combining results from multiple studies . The following are some types of evidence synthesis.

Systematic Review

- Exhaustive review of primary evidence on a clearly formulated question.

- Methods must be transparent, reproducible and follow an established protocol.

Literature (Narrative) Review

- A broad term referring to reviews with a wide scope and non-standardized methodology.

- Search strategies, comprehensiveness, and time range covered will vary and do not follow an established protocol.

Scoping Review or Evidence Map

- Systematically and transparently collect and categorize existing evidence on a broad question of policy or management importance.

- Seeks to identify research gaps and opportunities for evidence synthesis rather than searching for the effect of an intervention.

- May critically evaluate existing evidence, but does not attempt to synthesize the results in the way a systematic review would. (see EE Journal and CIFOR )

- May take longer than a systematic review.

- See Arksey and O'Malley (2005) for methodological guidance.

Rapid Review

- Applies Systematic Review methodology within a time-constrained setting.

- Employs methodological "shortcuts" (limiting search terms for example) at the risk of introducing bias.

- Useful for addressing issues needing quick decisions, such as developing policy recommendations.

- See Evidence Summaries: The Evolution of a Rapid Review Approach

Umbrella Review

- Reviews other systematic reviews on a topic.

- Often defines a broader question than is typical of a traditional systematic review.

- Most useful when there are competing interventions to consider.

Meta-analysis

- Statistical technique for combining the findings from disparate quantitative studies.

- Uses statistical methods to objectively evaluate, synthesize, and summarize results.

- May be conducted independently or as part of a systematic review.

The above was adapted from Cornell University LIbrary's A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: Types of Evidence Synthesis , https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis/types

Follow the links below to tools which will help you to determine which evidence synthesis method will work for you.

- Decision Tree This decision tree and review description produced by Cornell University will guide you to selection of the proper review for your study.

- What Tool is Right for You? This tool is designed to provide guidance and supporting material to reviewers on methods for the conduct and reporting of knowledge synthesis. As a pilot project, the current version of the tool only identifies methods for knowledge synthesis of quantitative studies.

- Next: How can the ULS assist you with your Evidence Synthesis? >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://pitt.libguides.com/SystematicReviews

Libraries | Research Guides

Evidence synthesis, how librarians can help, what is evidence synthesis, types of evidence synthesis, which type of review is right for you, statistical support for meta-analysis.

- Evidence Synthesis Resources by Discipline

- Steps in a Review

Attribution

Unless otherwise noted, this guide was adapted from Cornell University's "A Guide to Evidence Synthesis"

At Northwestern University Libraries, we offer general consultations regarding evidence synthesis projects, including literature reviews and systematic reviews. This includes:

- a basic overview of the systematic review process

- guidance on developing a search strategy and selecting databases

- methods for collecting and organizing articles

- resource recommendations for analyzing results

- identify relevant databases for you to search

- consult on and assist in the development of search strategies

- suggest and instruct on using reference management tools

- suggest tools that can assist in the meta-analysis process

- assist in writing methods section of manuscripts

If the project requires more long-term support, let us know. We may be able to provide additional assistance such as developing and reviewing search strings. Depending on the level of support provided, the researcher may need to provide acknowledgment of the librarian in the final publication.

If you'd like to set up a consultation, complete the Evidence Synthesis Consultation Request form.

Evidence synthesis refers to any method of identifying, selecting, and combining results from multiple studies. Systematic reviews and literature reviews are two methods of identifying and providing summaries of existing literature on a particular topic. They are quite different in scope and practice.

Adapted from Kysh, L. (2013). What’s in a name? The difference between a systematic review and a literature review and why it matters. [Poster] . Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.766364 . Licensed under CC-BY.

Types of evidence synthesis include:

Systematic Review

- Systematically and transparently collect and categorize existing evidence on a broad question of scientific, policy or management importance.

- Compares, evaluates, and synthesizes evidence in a search for the effect of an intervention.

- Time-intensive and often take months to a year or more to complete.

- The most commonly referred to type of evidence synthesis. Sometimes confused as a blanket term for other types of reviews.

Literature (Narrative) Review

- A broad term referring to reviews with a wide scope and non-standardized methodology.

- Search strategies, comprehensiveness, and time range covered will vary and do not follow an established protocol.

Scoping Review or Evidence Map

- Seeks to identify research gaps and opportunities for evidence synthesis rather than searching for the effect of an intervention.

- May critically evaluate existing evidence, but does not attempt to synthesize the results in the way a systematic review would. (see EE Journal and CIFOR )

- May take longer than a systematic review.

- See Arksey and O'Malley (2005) for methodological guidance.

Rapid Review

- Applies Systematic Review methodology within a time-constrained setting.

- Employs methodological "shortcuts" (limiting search terms for example) at the risk of introducing bias.

- Useful for addressing issues needing quick decisions, such as developing policy recommendations.

- See Evidence Summaries: The Evolution of a Rapid Review Approach

Umbrella Review

- Reviews other systematic reviews on a topic.

- Often defines a broader question than is typical of a traditional systematic review.

- Most useful when there are competing interventions to consider.

Meta-analysis

- Statistical technique for combining the findings from disparate quantitative studies.

- Uses statistical methods to objectively evaluate, synthesize, and summarize results.

- May be conducted independently or as part of a systematic review.

- Decision Tool What review is right for you? After answering a short series of questions, the tool will generate a suggestion of which type of review will meet you goals.

- Review Methodology Decision Tree (from Cornell University Library) This decision tree can help you decide between a literature review, rapid review, scoping review, systematic review, umbrella review, and a meta-analysis.

The Libraries are not able to provide statistics support for meta-analysis projects. Depending on your affiliation and the extent of your need, the groups linked below may be able to assist with your project:

- Research Computing Services: Consultation and Collaborative Project Support Northwestern's Research Computing Services group offers data consultations and may be able to assist with questions related to statistical programs and languages. They accept consultation requests and will evaluate their ability to assist on a case by case basis.

- Biostatistics Collaboration Center "The mission of the BCC is to support Feinberg School of Medicine investigators in the conduct of high-quality, innovative health-related research by providing expertise in biostatistics, statistical programming, and data management."

- Next: Evidence Synthesis Resources by Discipline >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 9:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/evidencesynthesis

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

Metasynthesis: An Original Method to Synthesize Qualitative Literature in Psychiatry

Jonathan lachal.

1 AP-HP, Cochin Hospital, Maison de Solenn, Paris, France

2 Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France

3 CESP, Faculté de médecine, Université Paris-Sud, Faculté de médecine, Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (UVSQ), INSERM, Université Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, France

Anne Revah-Levy

4 Service Universitaire de Psychiatrie de l’Adolescent, Centre Hospitalier Argenteuil, Argenteuil, France

5 ECSTRA Team, UMR-1153, INSERM, Paris Diderot University, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France

Massimiliano Orri

6 Université Paris-Sud, Paris, France

Marie Rose Moro

Metasynthesis—the systematic review and integration of findings from qualitative studies—is an emerging technique in medical research that can use many different methods. Nevertheless, the method must be appropriate to the specific scientific field in which it is used. The objective is to describe the steps of a metasynthesis method adapted from Thematic Synthesis and phenomenology to fit the particularities of psychiatric research.

We detail each step of the method used in a metasynthesis published in 2015 on adolescent and young adults suicidal behaviors. We provide clarifications in several methodological points using the latest literature on metasyntheses. The method is described in six steps: define the research question and the inclusion criteria, select the studies, assess their quality, extract and present the formal data, analyze the data, and express the synthesis.

Metasyntheses offer an appropriate balance between an objective framework, a rigorously scientific approach to data analysis and the necessary contribution of the researcher’s subjectivity in the construction of the final work. They propose a third level of comprehension and interpretation that brings original insights, improve the global understanding in psychiatry, and propose immediate therapeutic implications. They should be included in the psychiatric common research toolkit to become better recognized by clinicians and mental health professionals.

The use of qualitative research is proliferating in medical research ( 1 ). Over the past two decades, numerous studies in the field of psychiatry have used a qualitative protocol ( 2 , 3 ), and it has been recognized as a valuable way to “ obtain knowledge that might not be accessible by other methods and to provide extensive data on how people interpret and act upon their illness symptoms ” ( 4 ). What matters most is the respondent’s perspective and the joint construction by the respondent and the researcher of a context-dependent, multiple, and complex reality ( 5 ). In this respect, the qualitative approach is close to that of the psychiatrist: what is important is what the patient feels and experiences and what emerges during the interaction between the patient and the psychiatrist. Indeed, the subjective coconstruction inherent to most of qualitative methods seems especially close to the psychiatric clinical meeting. Both are useful for building up local theory that helps to increase two important aspects of theory: individually relevant theory for clinical work and field-specific general theory for research ( 6 ). Qualitative research offers a thick description (one that encompass all the complexity of the phenomenon, behavior, or context) of a phenomenon and attempts to document the complexity and multiplicity of its experience ( 6 ). Similarly, in their day-to-day clinical work, psychiatrists attribute great importance to complexity and try to place symptoms within the patient’s history, in all of its intricate context—which again plays a crucial role in therapeutic choices.

Some have expressed concern, however, that because qualitative studies are isolated and rarely used to contribute to practical knowledge, they do not play a significant role in the movement toward evidence-based medicine ( 5 ). To alleviate this concern and enable qualitative work to contribute to this movement, an increasing number of teams have worked to develop and apply synthesis methods to these data. Qualitative syntheses refer to a collection of different methods for systematically reviewing and integrating findings from qualitative studies ( 7 ). The aims of such methods are to capture the increasing volume of qualitative research, to facilitate the transfer of knowledge to improve healthcare, and to bring together a broad range of participants and descriptions ( 8 , 9 ). Qualitative syntheses require not only a systematic approach to collecting, analyzing, and interpreting results across multiple studies, but also to develop overarching interpretation emerging from the joint interpretation of the primary studies included in the synthesis ( 10 , 11 ). Therefore, it involves going beyond the findings of any individual study to make the “whole into something more than the parts alone imply” ( 12 ).

Qualitative syntheses are now recognized as valuable tools for examining participants’ meanings, experiences, and perspectives, both deeply (because of the qualitative approach) and broadly (because of the integration of studies from different healthcare contexts and participants). They have been shown to be particularly useful to identify research gaps, to inform the development of primary studies, and to provide evidence for the development, implementation, and evaluation of health interventions ( 13 ). Because of this growing importance, an important work has been done in the last ten years, in order to ensure the quality of qualitative syntheses, such as: describing the methods to ensure reproducibility, develop tools for assessing the quality of the primary articles, and establish reporting guidelines [see, for example, the ENTREQ statement ( 13 ), the GRADE-Cerqual protocol ( 14 ), and the Cochrane or EVIDENT works ( 15 , 16 )].

However, despite some qualitative syntheses have been successfully conducted in the field of mental health ( 2 , 3 , 17 – 20 ), no study considers the methodological specificities inherent to psychiatric epistemological stance ( 7 ). Filling this gap has been one of the aims of our team since 2011. In this methodological article, we aimed to discuss the challenge of implementing metasynthesis to improve the understanding of youths suicide. In this study, we adapted the Thematic Synthesis developed by Thomas and Harden and incorporate a phenomenological approach in order to deal with new rigor with general as well as psychiatric issues ( 21 ). We will present each step of the method (Figure (Figure1) 1 ) and will propose methodological discussions. The detailed description of the findings can be found elsewhere ( 22 ).

Distribution in time for articles included in the metasynthesis.

Conducting a Metasynthesis

Before start—constitution of a research group.

The constitution of the research group and the definition of the study method are an important step before engaging in any synthesis work. The researcher must work in collaboration with researchers of diverse backgrounds ( 9 ). A collaborative approach improves quality and rigor and subjects the analytical process to group reflexivity ( 11 ). The research team should include members trained in qualitative synthesis as well as those expert in the topic being studied ( 23 ). As there are many ways to do qualitative syntheses, the research team will have to choose one of them adapted to the research question and to the expertise of the group ( 15 ).

Our team is composed of adolescent and child psychiatrists and psychologists from France and elsewhere (Italy, Chile, and Brazil) and focuses on developing qualitative research ( 24 – 26 ) and metasynthesis in adolescent psychiatry and related fields ( 22 , 27 , 28 ). Our method is adapted from thematic synthesis ( 21 ), which combines and adapts approaches from both metaethnography and grounded theory ( 10 ). Metaethnography, as well as Thematic Synthesis, takes place in six or seven steps from data collection to text coding and finally writing the synthesis. Original authors of metaethnography were trained in grounded theory, a qualitative method developed in the social sciences, laying on conceptual coding combine to construct a new theory. Thematic synthesis allows the researcher to include much more studies in the synthesis and to use tools coming from quantitative reviews, as systematic literature searches. This method perfectly suits to psychiatric research: user-friendliness for both researchers and readers; standardized in its most subjective steps but flexible, to make it adaptable to various patients or situations, such as children, patients with psychological disabilities or psychotic disorders, and to different researchers’ backgrounds (e.g., phenomenology, psychology, or psychoanalysis). We add a phenomenological perspective with a coding close to Smith’s interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) ( 29 ). IPA is also a qualitative method of coding a text, laying on phenomenology and hermeneutics. The level of coding is what makes sense to the reader (for example, a letter, a word, a sentence, the absence of a word, or a sentence). Phenomenology allows avoiding never-ending debates about theories of the psyche and focuses on the patient experience which is at the heart of psychiatric care. We understand that published manuscripts provide only thin data sets that are not eligible for a complete phenomenological analysis. Rather we tried to let ourselves guided by the impressions the text generated in us. It was like one article was assimilated as one participant, as it is mainly the voice of the main writer. We applied Smith’s tips on how reading and coding the data.

Define the Research Question and the Selection Criteria

Defining the research question is a crucial substep ( 9 ). This question must be broad enough to be of interest but small enough to be manageable ( 5 , 23 ) and has already been explored by enough studies ( 30 ). Inclusion and exclusion criteria may be fixed on methodological aspects, on participants selected, on thematic focuses or language specificities ( 9 , 31 ).

Youths suicide is a focus that were suitable for qualitative methods. We chose this subject because youth suicide is a major public health issue worldwide as well as a complex disorder that encompasses medical, sociological, anthropological, cultural, psychological, and philosophical issues. It has been widely explored by qualitative research. The lack of effectiveness of current care let us think that new insights could be expected by qualitative exploration. A first selection of articles, as well as an existing literature review on the topic, served to specify some starting information and enable initial decisions, including the definition of the research question, specification of the scope and the inclusion criteria. Then, the questions were constructed through reading and confronting these articles with our first qualitative study in the theme and our clinical knowledge of the theme.

As we wanted to study the therapeutic relationship and barriers to effective care, we decided to include research concerning not only the population being treated (the adolescents and young adults, and their parents), but also the healthcare professionals who care for these patients. A first screening of the literature showed us that optimal scope required a large range of ages, from 15 to 30 years old. The common thread linking all these youths was the importance of their parents in their everyday life. We chose to include only qualitative research, because it remains unclear how to deal with mixed method (combining qualitative and quantitative datasets) ( 23 ). Although databases contain articles in different languages, we chose to include only articles published in English (as most studies are now published in English) and French (as it is our first language) ( 22 , 27 ).

Study Selection

There is a debate on the choice of sampling method, some authors using an exhaustive sampling, some others, an expansive one ( 30 ). We privileged exhaustive systematic searches ( 32 ) since our method allowed large samples and because our target audience was the mental health community, which is accustomed to quantitative systematic reviews ( 9 ). Only journal articles were included, as most scientific data are published in this form ( 33 ). The first selection of articles served to specify the choice of keywords and databases for the electronic search. To ensure both sensitivity and specificity, we decided to use a combined approach of thesaurus terms and free-text terms. This technique maximizes the number of potentially relevant articles retrieved and ensures the highest level of rigor ( 34 ). Keywords were established during research team meetings, and were reported in the article or as supplemental material for more clarity ( 35 ). As each database has its own thesaurus terms, and as keywords encompasses different meanings in each discipline ( 36 ), the keywords were specific for each one.

We used four clusters of keywords: (i) those that concern the topic of interest (such as suicide, obesity, or anorexia nervosa), (ii) those that concern the participants (gender, age, profession, etc.), (iii) those that concern qualitative research (such as qualitative research, interviews, focus groups , or content analysis ), and (iv) those that concern perceptions and understanding, often called “views” ( 33 ) (such as knowledge, perception, self-concept, feeling , or attitude ). The last cluster takes all its importance in the phenomenological perspective of the analysis. An example of the final algorithm used (in the PubMed Web search) is provided in Table Table1 1 .

Algorithm used in the PubMed Web search from Ref. ( 22 ).

Similar work was conducted to select the databases. After consulting reference articles ( 33 , 37 , 38 ), we decided to conduct the search in five electronic databases covering medical, psychological, social, and nursing sciences: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). Not long ago, CINAHL was the most important database for finding qualitative research, but as qualitative research proliferates in medical research, more and more qualitative articles are referenced in MEDLINE ( 33 ) and EMBASE. PsycINFO was a good database for finding qualitative articles with a psychological approach. We decided to add SSCI to broaden and complexity the outlook with a sociological point of view. We followed recommendations published on MEDLINE ( 39 ), CINAHL ( 40 ), EMBASE ( 41 ), and PsycINFO ( 42 ) for choosing search terms. Finally, we decided not to use the methodological databases’ filters for qualitative research, as these have undergone little replication and validation ( 43 ).

We decided to include articles published only in or after 1990. Two points impelled this decision: first, there was very little qualitative research on suicide before the year 2000 and even less before the 1990s (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). Second, we chose to consider as outdated research findings and results published more than 20 years ago were outdated, given the evolution of medical practices ( 44 ). However, this choice must be adapted to the topic of metasynthesis.

Flowchart of the metasynthesis steps.

The results of database searches were entered into a bibliographic software program (Zotero©) for automatic removal of duplicates. Then, two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts and selected the studies according to our inclusion criteria (defined earlier). If the abstract was not sufficient, we read the full text. Disagreements were resolved during working group meetings. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were then examined, and a second selection was performed. At this phase, we also checked each article’s reference list looking for new articles we might have overlooked. The final selection represented from 2 to 3% of the total initially obtained. This rate is consistent with the findings of other metasyntheses ( 23 ). For clarity, the selection process was also presented in a flowchart (Figure (Figure3). 3 ). We referred to STARLITE principles to report our literature search ( 45 ) (Table (Table2 2 ).

Flowchart for selecting studies from Ref. ( 22 ).

STARLITE principles applied to the literature search report of Ref. ( 22 ).

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

There is no consensus about whether quality criteria should be applied to qualitative research, or, for those who think they should be, about which criteria to use and how to apply them. Nevertheless a growing number of researchers are choosing to appraise studies for metasyntheses ( 46 ) and some authors state that a good metasynthesis can no longer avoid this methodological step ( 7 ). The reasons and methods for quality assessment fit into three general approaches: assessment of study conduct, appraisal of study reporting, and an implicit judgment of the content and utility of the findings for theory development ( 13 ). There is certainly not one best appraisal tool, but rather a wide choice of good ones ( 8 ).

We chose the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) ( 47 ), which is the most frequently used instrument ( 46 ), addresses all the principles and assumptions underpinning qualitative research ( 13 ). It is one of the instruments recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration ( 48 ) and has been used in several important thematic analyses of medical topics. As proposed by Boeije et al., we weighted our assessment by applying a three-point scale to each criterion (0 = criterion not met; 1/P = criterion partially met; 2/T = criterion totally met) ( 49 ) (Table (Table3 3 ).

Evaluation of the quality of the studies according to the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) from Ref. ( 22 ).

a Number of studies .

We have not excluded any study on quality criteria. We think that the goal of the quality assessment is not to help selecting the more rigorous article. Either, this step is important to improve the overall rigor of the metasynthesis: by easily evaluating the quality of each article, the readers will have the possibility to make their own evaluation of the quality of the results of the metasynthesis ( 9 ). To enhance the rigor of the synthesis, we published the full results of this assessment ( 50 ).

Extracting and Presenting the Formal Data

To understand the context of each study, readers need the formal data about each study: the number and type of participants in each study, its location, and the method of data collection and of analysis. These data must be extracted and presented in a way that enables readers to form their own opinions about the studies included. We presented these data systematically, in a table with the following headings:

- – Identification of the study.

- – Summary of the study’s aim.

- – Country where the study took place.

- – Details about the participants: age, gender, type, and number.

- – Method of data collection (e.g., semistructured interviews or focus groups).

- – Analysis method (grounded theory, phenomenology, thematic, etc.).

Data Analysis

This step is probably the most subjective: its performance is highly influenced by the authors’ backgrounds ( 13 ). There are many ways to analyze, as many as there are authors. All researchers build on their personal knowledge and background for the analysis, sometimes described as bricolage , following Claude Levi-Strauss: “ the bricoleur combines techniques, methods, and materials to work on any number of projects and creations. Whereas a typical construction process might be limited by the history or original use of individual pieces, the bricoleur works outside of such limitations, reorganizing pieces to construct new meaning. In other words, unlike linear, step-by-step processes, the bricoleur steps back and works without exhaustive preliminary specifications ” ( 51 , 52 ). The synthesis will inevitably be only one possible interpretation of the data ( 9 ), as it depends on the authors’ judgment and insights ( 21 ). The qualitative synthesis does not result simply from a coding process, but rather from the researchers’ configuration of segments of coded data “ assembled into a novel whole ” ( 53 ).