Ten Famous Intellectual Property Disputes

From Barbie to cereal to a tattoo, a copyright lawsuit can get contentious; some have even reached the Supreme Court

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Intellectual-Property-Disputes-The-Hangover-631.jpg)

1. S. Victor Whitmill v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. In the recent movie The Hangover Part II , Stu Price, a strait-laced dentist played by actor Ed Helms, wakes up after a night of debauchery in Bangkok to find a tribal tattoo wrapped around his left eye, his skin still painfully pink. Price’s tattoo is identical to the one Mike Tyson has, and it alludes to the boxer’s cameo in the original 2009 movie The Hangover .

Tyson’s tattoo artist S. Victor Whitmill filed a lawsuit against Warner Bros. Entertainment on April 28, just weeks before the movie’s May 26 opening. Since he obtained a copyright for the eight-year-old “artwork on 3-D” on April 19, he claimed that the use of his design in the movie and in advertisements without his consent was copyright infringement. Warner Bros., of course, saw it as a parody falling under “fair use.”

On May 24, 2011 Chief Judge Catherine D. Perry of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri denied an injunction on the movie’s release, but said Whitmill still had a case. If it meant avoiding a long trial, Warner Bros. said, in early June, that it would be willing to “digitally alter the film to substitute a different tattoo on Ed Helms’s face” when the movie is released on home video. But that ending was avoided on June 17, when Warner Bros. and Whitmill hashed out an agreement of undisclosed terms.

2. Isaac Newton v. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz By the early 18th century, many credited the German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz with inventing the study of calculus. Leibniz had, after all, been the first to publish papers on the topic in 1684 and 1686. But when Englishman Isaac Newton published a book called Opticks in 1704, in which he asserted himself as the father of calculus, a debate arose. Each of the thinkers’ respective countries wanted to stake a claim in what was one of the biggest advances in mathematics.

Newton claimed to have thought up the “science of fluxions,” as he called it, first. He apparently wrote about the branch of mathematics in 1665 and 1666, but only shared his work with a few colleagues. As the battle between the two intellectuals heated up, Newton accused Leibniz of plagiarizing one of these early circulating drafts. But Leibniz died in 1716 before anything was settled. Today, however, historians accept that Newton and Leibniz were co-inventors, having come to the idea independently of each other.

3. Kellogg Co. v. National Biscuit Co. In 1893, a man named Henry Perky began making a pillow-shaped cereal he called Shredded Whole Wheat. John Harvey Kellogg said that eating the cereal was like “eating a whisk broom,” and critics at the World Fair in Chicago in 1893 called it “shredded doormat.” But the product surprisingly took off. After Perky died in 1908 and his two patents, on the biscuits and the machinery that made them, expired in 1912, the Kellogg Company, then whistling a different tune, began selling a similar cereal. In 1930, the National Biscuit Company, a successor of Perky’s company, filed a lawsuit against the Kellogg Company, arguing that the new shredded wheat was a trademark violation and unfair competition. Kellogg, in turn, viewed the suit as an attempt on National Biscuit Company’s part to monopolize the shredded wheat market. In 1938, the case was brought to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the Kellogg Company on the grounds that the term “shredded wheat” was not trademarkable, and its pillow shape was functional and therefore able to be copied after the patent had expired.

4. Marcantonio Raimondi v. Albrecht Dürer Artist Albrecht Dürer discovered in the early 1500s that a fellow engraver by the name of Marcantonio Raimondi was copying one of his most famous works, a woodcut series of engravings called the Life of the Virgin . To make his prints, Raimondi carved detailed replicas of Dürer’s wood blocks. The prints, with Dürer’s “A” above “D” signature, could pass as Dürer originals, and Raimondi made considerable profits off of them. Dürer took issue and brought his case to the court of Venice. Ultimately, the court ruled that Raimondi could continue making copies, as long as he omitted the monogram.

5. Mattel Inc. v. MGA Entertainment Inc. Barbie was 42 years old when the exotic, puffy-lipped Bratz dolls Cloe, Jade, Sasha and Yasmin strolled onto the scene in 2001. Tensions escalated as the Bratz seized about 40 percent of Barbie’s turf in just five years. The Bratz struck first. In April 2005, their maker MGA Entertainment filed a lawsuit against toy powerhouse Mattel, claiming that the line of “My Scene” Barbies copied the big-headed and slim-bodied physique of Bratz dolls. Mattel then swatted back, accusing Bratz designer Carter Bryant for having designed the doll while on Mattel’s payroll. Bryant worked for Mattel from September 1995 to April 1998 and then again from January 1999 to October 2000, under a contract that stipulated that his designs were the property of Mattel.

In July 2008, a jury ruled in favor of Mattel, forcing MGA to pay Mattel $100 million and to remove Bratz dolls from shelves (an injunction that lasted about a year). But the two toy companies continued to duke it out. This April, in yet another court case, underdog MGA prevailed, proving that Mattel was actually the one to steal trade secrets.

6. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.

“Weird Al” Yankovic has a policy of writing a parody of a song only if he gets permission from the artist. In the late 1980s, the rap group 2 Live Crew attempted to play by the same rules. Luther Campbell, one of the group members, changed the refrain of Roy Orbison’s hit “Oh, Pretty Woman” from “pretty woman” to “big hairy woman,” “baldheaded woman” and “two-timin’ woman.” 2 Live Crew’s manager sent the bawdy lyrics and a recording of the song to Acuff-Rose Music Inc., which owned the rights to Orbison’s music, and noted that the group would credit the original song and pay a fee for the ability to riff off of it. Acuff-Rose objected, but 2 Live Crew included the parody, titled “Pretty Woman,” on its 1989 album “As Clean as They Wanna Be” anyway.

Acuff-Rose Music Inc. cried copyright infringement. The case went to the Supreme Court, which, in so many words, said, lighten up. “Parody, or in any event its comment, necessarily springs from recognizable allusion to its object through distorted imitation,” wrote Justice David Souter. “Its art lies in the tension between a known original and its parodic twin.”

7. Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh v. The Random House Group Limited Authors Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh surfaced in 2004 with claims that Dan Brown had cribbed the “central theme” and “architecture” of their 1982 book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail . Though Baigent and Leigh’s book was nonfiction and Brown’s The Da Vinci Code was fiction, they both boldly interpret the Holy Grail as being not a chalice but the bloodline of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, who they alleged had a child together.

Baigent and Leigh accused Random House—ironically, their own publisher, as well as Brown’s—for copyright infringement. A London court ruled, in 2006, that historical research (or “historical conjecture,” as was the case with The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail ) is fair game for novelists to explore in fiction. “It would be quite wrong if fictional writers were to have their writings pored over in the way The Da Vinci Code has been pored over in this case by authors of pretend historical books to make an allegation of infringement of copyright,” wrote Justice Peter Smith in his decision.

8. Lucasfilm Ltd. v. High Frontier and Lucasfilm v. Committee for a Strong, Peaceful America When politicians, journalists and scientists, in the mid-1980s, nicknamed the Reagan administration’s Strategic Defensive Initiative (SDI), the “star wars” program, George Lucas’s production company was miffed. It did not want the public’s positive associations with the term to be marred by the controversial plan to place anti-missile weapons in space.

In 1985, Lucasfilm Ltd. filed a lawsuit against High Frontier and the Committee for a Strong, Peaceful America—two public interest groups that referred to SDI as “star wars” in television messages and literature. Though Lucasfilm Ltd. had a trademark for Star Wars, the federal district court ruled in favor of the interest groups and their legal right to the phrasing so long as they didn’t attach it to a product or service for sale. “Since Jonathan Swift’s time, creators of fictional worlds have seen their vocabulary for fantasy appropriated to describe reality,” read the court decision.

9. A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster Inc. In 1999, to the dismay of musicians around the world looking to sell albums, Shawn Fanning, an 18-year-old whiz kid studying computer science at Northeastern University, created Napster, a peer-to-peer music sharing service that allowed users to download MP3s for free. A&M Records, part of Universal Music Group, a heavy hitter in the music industry, as well as several other record companies affiliated with the Recording Industry Association of America slapped Napster with a lawsuit. The plaintiffs accused Napster of contributory and vicarious copyright infringement. The case went from the United States District Court for the Northern District of California to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, where Napster was found guilty on both counts. In 2002, Napster was shut down. Grokster, another music-sharing site, surged on for a few more years, but it too stopped operating when the Supreme Court ruled against it in MGM v. Grokster in 2005.

10. Adidas America Inc. v. Payless Shoesource Inc. In 1994, Adidas and Payless got into a scuffle over stripes. Adidas had used its three-stripe mark as a logo of sorts since 1952, and had recently registered it as a trademark. But Payless was selling confusingly similar athletic shoes with two and four parallel stripes. The two companies hashed out a settlement, but by 2001, Payless was again selling the look-alikes. Fearing that the sneakers would dupe buyers and tarnish its name, Adidas America Inc. demanded a jury trial. The trial lasted seven years, during which 268 pairs of Payless shoes were reviewed. In the end, Adidas was awarded $305 million—$100 million for each stripe, as the Wall Street Journal ’s Law Blog calculated.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

5 Interesting IP Cases of 2021

Photo by Edward Jenner from Pexels

What do Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction NFTs, a $1.2 billion cell therapy patent infringement verdict, and Google’s copying of Java code have in common?

They’ve made it to our list of top 5 intellectual property cases of the past year! Here, we take a look back at cases selected because we find them interesting and hope you do too. These cases should be remembered for their enduring influence, especially as NFTs blow up the inter metanet this year and beyond.

Case Summary:

1 – Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc. : Does copyright protection extend to a software interface, and how does fair use of a software interface apply?

2 – Miramax, LLC v. Quentin Tarantino : Who has the rights to develop, market, and sell film-related NFTs?

3 – Belcher v. Hospira: How should inconsistent statements to the FDA and PTO by patent applicants be treated?

4 – Juno v. Kite : How much territory can a patent reasonably stake out, especially with respect to functionally-defined biological compounds?

5 – Biogen v. Mylan : How much disclosure is required to support a patent claim? Or more simply, how little support is too little?

1 – Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 S. Ct. ___ (2021)

What’s at stake: Does copyright protection extend to a software interface, and how does fair use of a software interface apply?

We jumped the gun in 2020 and profiled this case in 5 Interesting IP Cases of 2020 when it was still pending. With the verdict in, we think it deserves a spot on this year’s list too.

Background:

At issue is copyright ability of application programming interfaces (APIs) and fair use of Google’s use of Java Standard Edition (SE) (“Java”). The Copyright Act of 1976 enshrined fair use in statutory law (codified at 17 U.S.C. § 107 ), setting four criteria for fair use of copyrighted material in limited circumstances to balance public interest with interests of copyright holders.

This billion-dollar case has a lengthy history from development of Java starting in 1990 to litigation spanning 2010 to present day. Sun Microsystems developed Java, including libraries documented via APIs that allowed for interoperability, and in the mid-2000s a licensing deal could not be reached between Sun and Google for Google to incorporate Java into its Android system.

Google developed its own version of Java libraries instead of licensing Java and incorporated API calls and code central to Java. It’s undisputed that Google copied approximately 11,500 lines of declaring code and organizational structure for 37 packages from Java. Oracle acquired Sun in 2009 and litigation ensued from 2010 – 2015.

Since then, Google won in a District Court jury trial and Oracle appealed to the CAFC , where Oracle won and the case was remanded to the District Court to determine damages Google should pay Oracle. Google’s petition for writ of certiorari to the US Supreme Court was granted and oral arguments were postponed due to COVID-19.

To spice things up a bit, two administrations have backed Oracle ( Obama and Trump ), while Microsoft , Mozilla Corporation , Red Hat , IBM , and many others have backed Google.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in April 2021 in favor of Google , reversing the Federal Circuit ruling and remanding for further review. Google’s copying of the Java API was deemed fair use.

As far as copyright ability of computer programs, the Majority (i.e. the champs) took a pass on that question and assumed for argument’s sake that the copyright was valid.

However, the Dissent (i.e. the runners-up who still get a speech) contended that this assumption was a fatal flaw in reasoning . Congress made no distinction between declaring and implementing code in establishing copyright ability of computer programs. The Dissent argued that the Majority erred in myriad ways, including distinguishing between declaring and implementing code, and thus the Majority eviscerated copyright. In not playing very nicely in the sandbox, Justice Thomas noted that Google “erased 97.5% of the value of Oracle’s partnership with Amazon, made tens of billions of dollars, and established its position as the owner of the largest mobile operating system in the world.” (Could someone get the good Justice an invite to a Larry Ellison yacht party already?)

One important difference in opinion concerned the quantity of code copied. One can view it as a little (the Majority view) or a lot (the Dissenting view). Google copied only 11,500 lines of the 2.86 million lines of code in the API – a little (0.4%). Alternatively, Google copied virtually all the declaring code for hundreds of different tasks – a lot. The dissent contended, “the proper denominator is declaring code , not all code,” finding that Google copied a lot of code.

How this fits with legal precedent:

The Majority maintained that “the application of a copyright doctrine such as fair use has long proved a cooperative effort of Legislatures and courts, and that Congress, in our view, intended that it so continue.” They argued for the judge-made origins of the fair use doctrine (§ 107), and as such its flexibility depending on context. They also put much stock in the fair use doctrine as an “equitable rule of reason” that should not be applied rigidly at risk of stifling “the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.” Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207, 236 (1990).

The Dissent cut to the chase, concluding, “The majority has used fair use to eviscerate Congress’ considered policy judgement.” (Ouch, virtual glove slaps still sting! Think Justice Thomas carries one of those wallets Samuel L. Jackson favored in Pulp Fiction?)

Favorite quotes from Opinion of the Court and Dissenting Opinion :

Majority: “The doctrine of “fair use” is flexible and takes account of changes in technology.”

Dissent: “Now, we are told, “transformative” simply means…a use that will help others “create new products.”… That new definition eviscerates copyright . A movie studio that converts a book into a film without permission not only creates a new product (the film) but enables others to “create products” – film reviews, merchandise, YouTube highlight reels, late night television interviews, and the like.” (emphasis added)

- Miramax, LLC v. Quantin Tarantino; Visiona Romantica, Inc.; and DOES 1 – 50

What’s at stake: Who has the rights to develop, market, and sell film-related non-fungible tokens (NFTs) when underlying copyright rights are protectable? Specifically, can Quentin Tarantino auction off-scenes from Pulp Fiction in the form of NFTs?

What’s an NFT?

Whether you’re all in on NFTs or giggle at the idea like Keanu Reeves , it looks like they are here to stay.

What is an NFT? Basically, it’s a unique, non-interchangeable, blockchain-stored unit of data. That’s confusing, let’s try again: it’s a way of owning a digital file using a digital ledger to provide public proof of ownership without restricting sharing or copying of the digital file. Still confusing – maybe an analogy would be better? It’s like naming a star so all can search and see that it’s yours while the stars remain visible for all to enjoy. Better?

Coincidentally, stars available for naming on the above-linked Star Register will be backed by NFTs minted in July 2022…

In a November 2, 2021 press release, Secret Network (SCRT Labs) announced the sale of seven “exclusive scenes” form the 1994 film Pulp Fiction in the form of secret NFTs, or NFTs “enhanced with privacy and access control features to create hidden content and experiences.” At the time of this writing, the Tarantino NFT website boasts the sale of “few and rare NFTs” as “the most unique use-case for NFTs ever made” and assures prospective purchasers that they will “get a hold of secrets from the mind and creative process of Quentin Tarantino.”

Miramax was not amused. On November 4, Miramax sent a cease and desist letter, to which Tarantino’s counsel replied on November 5, stating that each NFT will include a “drawing that will be inspired by some element form the scene” and that Tarantino is acting within his “Reserved Rights” to “print publication” as detailed in the Original Rights Agreement effective June 23, 1993.

Miramax then seemed personally offended. In a suit filed on November 16, 2021, Miramax lamented that Tarantino kept his NFT plans secret from his “long-time financier and collaborator” on Pulp Fiction and other films. The suit details the terms of the Original Rights Agreement and the Tarantino-Miramax Assignment executed July 15, 1993 and recorded with the U.S. copyright Office on August 6, 1993. The suit alleges Breach of Contract, Copyright Infringement under 17 U.S.C. § 501, Trademark Infringement under 15 U.S.C. § 1114, and Unfair Competition under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a).

This one is hot off the presses, so we have no definitive answer here . It is telling, however, that the lawsuit included screenshots from the Tarantino NFT website depicting images of characters played in the film by Samuel L. Jackson, John Travolta, and Uma Thurman, and those images are no longer in use. The website now includes less recognizable images evocative of Pulp Fiction. Perhaps use of the original set of images was a bit of a gamble?

Favorite quotes from the lawsuit:

“Defendants’ infringing acts have caused and are likely to cause confusion, mistake, and deception among the relevant consuming public as to the source of the Pulp Fiction NFTs.” “Tarantino’s conduct may mislead other creators into believing they have rights to exploit Miramax films through NFTs and other emerging technologies, when in fact Miramax holds those rights for its films.”

- Belcher Pharmaceuticals, LLC v. Hospira, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021)

What’s at stake: How should inconsistent statements to the FDA and PTO by patent applicants be treated?

Drug development is a winding road, from scientific decisions made very early in the discovery process and PTO filings to clinical trial design and submissions to the FDA seeking regulatory approval. Mistakes along the way can be quite costly. One such mistake, providing different information to different government agencies, is at issue here and is not unlike a child playing each parent independently of the other to get her way.

Belcher Pharmaceuticals, LLC (“Belcher”) sought to develop an injectable l-epinephrine formulation with improved characteristics, and toward that end sought (i) patent protection in the form of issued U.S. Patent No. 9,283,197 (the “ ‘197 patent”) and (ii) regulatory approval in the form of New Drug Application (“NDA”) No. 205029. The NDA was based entirely on the literature and neither pre-clinical nor clinical studies supported the submission.

Belcher asserted the ‘197 patent against Hospira, Inc. (“Hospira”) in an infringement suit, the U.S. District Court ruled the ‘197 patent unenforceable due to inequitable conduct , and Belcher appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”).

Much of the case hinges upon the conduct and intent of Mr. Darren Rubin, Belcher’s Chief Science Officer. Mr. Rubin was considered the head of IP (though he was not a registered patent agent or attorney), and oversaw both IP matters and matters pertaining to regulatory approval. Mr. Rubin was a key player in drafting and prosecution of the ‘197 patent as well as drafting of the NDA. Thus, Mr. Rubin was involved in communicating information to both the PTO and the FDA.

To expedite regulatory approval , the NDA (submitted on November 30, 2012) referred to the 2.8 to 3.3 pH range of the formulation as “old” since a pre-existing product made by Swiss company Sintetica SA (“Sintetica”) already exhibited a similar range and could be relied upon in lieu of new data. To expedite patent issuance , a response to an Office Action rejecting claims as obvious argued against obviousness based on the criticality of the 2.8 to 3.3 pH range. The Examiner allowed the claim, reasoning that nothing in the prior art would teach or suggest the criticality of the pH range.

Statements in the NDA submitted to the FDA directly conflicted with statements later submitted to the PTO. The NDA was submitted on November 30, 2012 , and the response to the Office Action was filed on November 5, 2015 . To quote Scooby-Doo: ruh roh.

The CAFC on September 1, 2021 affirmed the District Court’s ruling, finding that the District Court did not clearly err or abuse its discretion in deciding that the ‘197 patent is unenforceable.

The court rejected Belcher’s rationales for Mr. Rubin withholding relevant prior art from the PTO. Belcher argued that Mr. Rubin genuinely believed the prior art references were irrelevant. The court didn’t buy it since Mr. Rubin knew of several relevant references before and during prosecution of the ‘197 patent and he played a central role in both FDA submissions and PTO filings.

Eight days after this ruling on September 9, 2021, Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Thom Tillis (R-NC) sent a letter (PDF) to acting Director of the USPTO Drew Hirshfeld asking that the PTO take steps to “enforce patent applicants’ obligations to disclose statements made to other government agencies.” The letter takes direct aim at the inequitable conduct of Belcher v. Hospira and imagines a world where information flows from other federal agencies (i.e., the FDA) to the PTO.

Time will tell what becomes of the request, i.e. hahahahahahaha.

Inequitable conduct in patent law is a breach of the applicant’s duty of candor by omitting material information or misrepresenting with intent to deceive in dealings with the PTO. Section 2016 of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) states that a finding of inequitable conduct “with respect to any claim in an application or patent, renders all the claims thereof unpatentable or invalid.” Thus, inequitable conduct is not limited to certain claims, but is all or nothing.

A ruling in Therasense, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson and Co. , 649 F.3d 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2011) strengthened the standards for finding materiality and intent and prompted the PTO to rewrite the definition of materiality, enshrining it in 37 CFR § 1.56 . In Belcher v. Hospira , the court pointed to Aventis Pharma S.A. v. Hospira, Inc. , 675 F.3d 1324, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2012) in which the court rejected post hoc rationales akin to Belcher’s argument that Mr. Rubin genuinely believed the references were immaterial.

Favorite quotes from Opinion of the Court:

“…prior art is but-for material information if the PTO would not have allowed a claim had it been aware of the undisclosed prior art.” “…the district court found that [Mr. Rubin’s criticality] argument was “false” and a “fiction” because Mr. Rubin knew about the prior art’s teachings of that pH range.” (emphasis added)

Note: We offer due diligence services for investors that examine patent portfolios in light of FDA composition and manufacture disclosures. Nothing about this selection of a Top 5 IP case has anything to do with those services. And Matrix Resurrections is hands-down the best Matrix movie of all time.

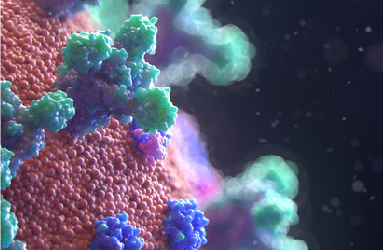

- Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021)

What’s at stake: How much territory can a patent reasonably stake out, especially with respect to functionally-defined biological compounds?

In particular, the biological compound at the center of this case is YESCARTA®, an FDA-approved cell therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. The stakes are huge, with a whopping ~$1.2 billion on the line after a U.S. District Court judgement against Kite Pharma, Inc. for willful infringement.

Juno Therapeutics and the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research (“Juno”) sued Kite Pharma, Inc. (“Kite”) and won in a jury verdict, so Kite appealed to the Federal Circuit, challenging the validity of claims of the patent Juno asserted against Kite’s YESCARTA®, U.S. Patent No. 7,446,190 (the “ ‘190 patent”).

The jury in the District Court found that the ‘190 patent contained adequate written description supporting the asserted claims and found that Kite’s infringement of the ‘190 patent was willful, leading to the massive ~$1.2 billion judgement. Naturally, Kite appealed.

The ‘190 patent claims cover chimeric T-cell receptors, which are important components of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies. In CAR T-cell therapies, cells of the body’s natural immune system are re-engineered to attack cancer cells. This is done by modifying a patient’s own T cells with a CAR targeted to specific proteins, called antigens, present in tumors.

CARs are proteins composed of several domains, including a binding domain that interacts with an antigen (see our blog post on patenting antibody therapeutics for more on antibody-based binding domains).

Juno’s patent claimed, among other things, receptors with “a binding element that specifically interacts with a selected target.” The patent disclosed by name (and not nucleic acid or amino acid sequence) two binding elements, also known as single chain variable fragments (scFVs). By claiming these biological compounds functionally (i.e., by binding ability) instead of structurally (i.e., by 3D structure determined by amino acid sequence), Juno claimed quite broadly. Kite sought to invalidate the ‘190 patent based on lack of written description supporting these broad claims.

The CAFC agreed with Kite, and on August 26, 2021 reversed the District Court’s ruling, finding inadequate written description in the ‘190 patent to support the claims.

The court was not convinced by Juno’s expert and inventor testimony that scFvs were generally known in the field, and that other claimed elements were the heart of the invention. Instead, the court focused on the “ millions of billions ” of possible scFv sequences claimed in the ‘190 patent, leading the court to conclude that these claims are generic and the patent lacks support for the functionally-defined genus (see MPEP 806.04 for more on generic claims).

In this ruling, the court cited Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co. , 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) in which the court held that sufficient description of a genus requires “either a representative number of species falling within the scope of the genus or structural features common to the members of the genus…” Since claims of the ‘190 patent cover “any scFv for binding any target” and are thus generic, the written description must include either representative species or structural features. The court found it lacked both.

“The problem with the ‘190 patent is that, although there were some scFvs known to bind some targets, the claims cover a vast number of possible scFvs and an undetermined number of targets about which much was not known in the prior art.” “ It is not fatal that the amino acid sequences of these two scFvs were not disclosed as long as the patent provided other means of identifying which scFvs would bind to which targets, such as common structural characteristics or shared traits.” (emphasis added).

“A ‘mere wish or plan’ for obtaining the claimed invention is not adequate written description.” (quoted from Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc. v. Abbott Labs. , 636 F.3d 1341, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

- Biogen Int’l GmbH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021)

What’s at stake: How much disclosure is required to support a patent claim? Or more simply, how little support is too little?

As we described above, drug development is a winding road, and twists and turns during the regulatory approval process may drive similar twists and turns during patent prosecution. Patent practitioners strive to anticipate the nature of a drug product when it hits the market and draft a patent application accordingly. However, the clinical pathway to approval may result in a product that requires claim amendments lacking sufficient support in the original filing.

Biogen International GmbH and Biogen MA, Inc. (“Biogen”) sued Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Mylan”) for patent infringement in U.S. District Court. Biogen asserted 6 patents purportedly covering Tecfidera® and alleged that Mylan’s proposed generic dimethyl fumarate (DMF) product for treating multiple sclerosis (MS) was infringing.

In a bench trial, the District Court ruled in favor of Mylan, finding patents invalid for lack of written description. Biogen appealed to the Federal Circuit, narrowing the scope of the suit to only U.S. Patent No. 8,399,514 (the “ ‘514 patent”).

Biogen markets DMF at a dose of 480 mg/day (DMF480) under the brand name Tecfidera® for treatment of MS. Notably, the ‘514 patent mentions this dose only once in the specification at the lower end of a 480 – 720 mg/day range. Biogen had not included the 480 mg/day dose in its clinical trials, but the FDA recommended testing this dose in a Phase III clinical trial.

The 480 mg/day dose showed efficacy, and much of this case centered on whether Biogen’s February 8, 2007 patent filing supports claims of the ‘514 patent that ultimately issued in 2011.

On November 30, 2021 the Majority (think: Pats) affirmed the District Court’s ruling, finding inadequate written description in the ‘514 patent to support the claims and thus holding Biogen’s ‘514 patent invalid.

The Dissent (think: Jets) vociferously disagreed, taking issue with both the District Court and the Majority’s unwillingness to allow Biogen to draw a distinction between therapeutic and clinical effects . The Dissent argued that this is a fundamental error, and that a proper distinction between the two would impact the written description requirement analysis and change the outcome of the case.

As the Majority explained, “whether a claim meets the written-description requirement is a question of fact.” As in Juno v. Kite , the Majority cites Ariad to explain that “the term “possession” in the context of written-description jurisprudence entails an “objective inquiry into the four corners of the specification…” and that mere theoretical research cannot result in an awarded patent.

The Majority further points to Novozymes v. DuPont Nutrition Biosciences APS , 723 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“ Novozymes ”) and In re Ruschig , 379 F.2d 990, 994–95 (CCPA 1967) to elucidate written description requirements when a broad genus is disclosed and a particular species is claimed.

For laundry list-type disclosures, Novozymes and In re Ruschig require ‘blaze marks’ to guide a reader toward the claimed compound, similar to blaze marks on trees marking trails through an otherwise unmarked forest.

Anyone who has lost their way in the backcountry knows the relief that comes from sighting a blaze mark, and the pure joy of leap frogging from mark to mark to relocate a clearly delineated trail. The Majority finds that a reader would lose their way in the wilderness of patent ‘514 laundry list disclosures, and that the one reference to a 480 mg/day dose is an insufficient blaze mark to point to the claimed invention.

Majority: “The DMF480 dose is listed only once in the entire specification….That is in stark contrast to DMF720, which is referenced independently as one dose and was known to be effective as of the February 2007 priority date.” “The district court, as the finder of fact, did not find it necessary or appropriate to distinguish between therapeutic effects and clinical efficacy based on the specification’s definition of “therapeutically effective dose”…”

Dissent: “Clinical efficacy involves the type of scientific rigor associated with Phase III clinical trials…Therapeutic effects, by contrast, “do not require efficacy on clinical endpoints or superior efficacy to existing drugs.”” “…the district court’s refusal to acknowledge the difference between therapeutic and clinical effects evinces a fundamental misunderstanding of what is claimed…” “How much brighter need a disclosure blaze?”

About Andrew Lerner

Andrew Lerner joined RVL® as a registered patent agent upon completing his PhD in Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. His practice areas include clearance & patentability analyses, patent prosecution, and due diligence; strategic IP portfolio development; and IP diligence for life science venture funds.

Andrew has supported faculty, researchers, and staff involved in innovation and commercialization across broad disciplines at top tier universities, and has led IP and market diligence activities for life science, biotechnology, and medical device seed funding. He serves as a reviewer for several seed stage funding mechanisms and regularly advises entrepreneurs as a mentor through Veterati, a platform that connects veterans/mentors with Service Members, Veterans, and Military Spouses.

Rockridge Venture Law® is a certified B Corp law firm embracing the mantra of technology lawyers for good. Rockridge® services include corporate, intellectual property, litigation, M&A, privacy, technology, and venture capital law. Rockridge has been recognized as a B Corp Best for the World and Real Leaders Top 150 Impact Company , and has been featured by Conscious Company Magazine, Forbes, and other top media focused on industry leaders in impact and innovation.

The Rockridge team has worked with Grammy winners, Nobel Prize winners, and world champion athletes to create and monetize distinctive intellectual property assets. Rockridge clients include founders, investors, and multinationals scaling disruptive technologies and iconic brands. Rockridge is headquartered in Tennessee, with satellite offices in Durham and New York.

We’re Building Today’s Company for Tomorrow’s Economy® by leading clients through the dizzying array of information controls, by helping them to develop and monetize proprietary assets, and by enabling their impactful products, programs, and principles.

See case studies on how we’ve helped transformative companies at Rockridge Case Studies.

Recent Posts

- How “Barbie Pink” Became A Trademark Protected Color of Mattel

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Bans Noncompetes

- Profile of a Benefit Biotech: United Therapeutics’ Journey of Becoming and Existing as a Public Benefit Corporation (PBC)

- Top Trademark Holdings of 2023

- 2024 Guide to Utah Benefit Corporations

- February 2024

- September 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- October 2022

- September 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- January 2017

- Artists, Athletes & Influencers

- B Tennessee

- Benefit Corporations, ESG & Social Enterprise

- Blockchain & Data Rights

- Branding, Copyrights & Trademarks

- Business Law

- Cannabis – Industrial & Medical

- Commercialization & Tech Transfer

- Contract Negotiations

- Corporate Governance & General Counsel

- Entertainment and Sports

- Forming and Funding

- Government Contracts

- Patents & Trade Secrets

Previous Post Rockridge® Guide to Southeastern Benefit Corporation Statutes

Next post stuffed sculptures - the beanie baby® ip powerhouse.

Author Andrew Lerner

Patent Lead at Rockridge Venture Law // Innovation Fellow at UNC School of Pharmacy // Ph.D., UNC - Chapel Hill, Biochem/Biophysics // B.S. University of California, Berkeley // Veteran U.S.M.C. Russian cryptologist

Comments are closed.

BUILDING TODAY’S COMPANY FOR TOMORROW’S ECONOMY®

PRIVACY POLICY

STAY IN THE KNOW, WITH RVL NEWS

Email address:

© 2024 Rockridge Law. Moses Media Co.

- CASE STUDIES

Historic James Building 735 Broad Street, STE 1001 Chattanooga, TN 37402

Nashville Entrepreneur Center 41 Peabody St. Nashville, TN 37210 (For client and partnership meetings only)

The Yale Club 50 Vanderbilt Ave. New York, NY 10017 (For client and partnership meetings only)

RVL® is a business, intellectual property, and technology firm, building today’s companies for tomorrow’s economy.

Privacy Overview

Case Study on Intellectual Property Rights: Everything You Need to Know

IP rights is an example of a real-world legal case involving IP rights that can give you an idea of a how a court may rule in a particular legal scenario. 4 min read updated on January 01, 2024

What Is an Intellectual Property Rights Case Study?

A case study on intellectual property rights is an example of a real-world legal case involving intellectual property rights that can give you an idea of a how a court may rule in a particular legal scenario. Examining such studies can be valuable as it will give you some idea if your actions involving intellectual property will be deemed legal by a court of law.

Intellectual Property Rights Case Study Examples

The following are five examples of intellectual property rights cases that are illustrative of how intellectual property law may work:

- S. Victor Whitmill v. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. In this case, S. Victor Whitmill, a tattoo artist, filed suit against Warner Bros. for copyright infringement due to their use of a tattoo he created for Mike Tyson, which was subsequently depicted on a fictional character in the Warner Bros. film The Hangover, Part II . Warner Bros., on the other hand, argued that their use of the tattoo was in the spirit of parody and thus was covered by Fair Use . Ultimately, Whitmill’s desire for an injunction against the release of the film was denied, and an agreement between the two parties was made out of court for undisclosed terms.

- National Biscuit Co. v. Kellogg Co. In this case, National Biscuit Co. filed suit against Kellogg Co. over their sale of shredded wheat cereal. According to National Biscuit Co., Kellogg’s manufacture and sale of this product constituted unfair competition and trademark violation, since the previous iteration of their company had been owned by the inventor of shredded wheat and the machinery used to make it, although the patents on both inventions had been allowed to expire. Kellogg Co. countered with the argument that National Biscuit’s suit amounted to an attempt to monopolize the market on shredded wheat. Ultimately, the US Supreme Court ruled that “shredded wheat” was not a trademarkable term and its design was a functional one, and thus free for copying since the trademark had expired.

- MGA Entertainment Inc. v. Mattel Inc. In this case, toymaker MGA Entertainment filed suit against Mattel, arguing that their line of “My Scene” Barbie dolls infringed upon the design of MGA’s line of "Bratz" dolls, which had a similar appearance. Mattel then countersued, claiming Carter Bryant, a designer for MGA, had designed the dolls while working for Mattel and subject to a contract that stated that all designs made while under contract would be Mattel’s property. A jury eventually ruled in Mattel’s favor, hitting MGA with a $100 million reparation to Mattel as well as an injunction (which lasted a year) to cease selling the dolls in question. However, in a later case over the same issue, the ruling went in favor of MGA, and Mattel was considered to be the one that stole trade secrets .

- A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster Inc. In this case, A&M Records sued the file-sharing business Napster over its website, wherein users could download music files free of charge. A&M Records claimed that this was vicarious and contributory copyright infringement , and before the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, Napster was ruled to be guilty of both counts. As a result, it was forced to shut down, as was Grokster, a file-sharing site that operated under a similar model, a few years later.

- Lucasfilm Ltd. v. High Frontier and Lucasfilm v. Committee for a Strong, Peaceful America . In these cases, Lucasfilm Ltd. filed suits against the public interest groups High Frontier and the Committee for a Strong, Peaceful America over their use of the term “star wars” to describe President Reagan’s Strategic Defensive Initiative, which involved space-bound missile defense. The term was born out of the popularity of the Star Wars movie franchise, and Lucasfilm did not want their product associated with a controversial, politically divisive defense policy. The court ruled that the term “star wars” could be used as long as it was not used to sell a product or service, further observing that creators of fiction had long seen their invented terms used to describe reality.

Considering these five cases as well as others may give you some idea of how courts interpret IP law . That said, each case is different, and there are many factors that go into determining a ruling, including the facts of the case, the jurisdiction of the case, and the judge or jury hearing the case, all of which could potentially yield a different result.

If you need more than a case study on intellectual property rights to help you in understanding intellectual property law, you can post your legal need on UpCounsel’s marketplace. UpCounsel accepts only the top 5 percent of lawyers. Lawyers on UpCounsel come from law schools such as Harvard Law and Yale and average 14 years of legal experience, including work with or on behalf of companies like Google, Menlo Ventures, and Airbnb.

Hire the top business lawyers and save up to 60% on legal fees

Content Approved by UpCounsel

- Intellectual Property Cases

- Intellectual Property Disputes

- Waiver of Intellectual Property Rights

- Violation of Intellectual Property

- Intellectual Theft

- Management of Intellectual Property

- Intellectual Property Examples

- Intellectual Property Rights

- Intellectual Property Law

- Intellectual Property Insurance

Trending News

Related Practices & Jurisdictions

- Intellectual Property

- Litigation Trial Practice

- All Federal

With the continuing advancements of cutting-edge technologies — such as genome editing (CRISPR) and Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) — U.S. courts will have a full docket of challenging IP cases throughout 2023. Below are some of the most significant issues we are watching:

Keep an Eye on the US Supreme Court for New IP Law in 2023

Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith , 11 F.4th 26 (2d. Cir. 2021), cert. granted , 142 S. Ct. 1412 (Mar. 28, 2022) (No. 21-869). The Supreme Court heard arguments on October 12, 2022 whether a work of art which “recognizably deriv[es] from” its source material but conveys a different meaning or message is sufficiently “transformative” to render the accused work a fair use, or whether further justification must be shown to qualify as a fair use.

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, Aventisub LLC , 987 F.3d 1080 (Fed. Cir. 2021), cert. granted in part sub nom. Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi , 143 S. Ct. 399 (Nov. 4, 2022) (No. 21-757). In Amgen , the Supreme Court will address the issue of whether a patent specification must disclose “the full scope of claimed embodiments” without undue experimentation.

Hetronic Int'l, Inc. v. Hetronic Ger. GmbH , 10 F.4th 1016 (10th Cir. 2021), cert. granted sub nom. Abitron Austria GmbH v. Hetronic Int'l, Inc. , 143 S. Ct. 398 (Nov. 4, 2022) (No. 21-1043). The question presented here is whether the Tenth Circuit erred in applying the Lanham Act extraterritorially to petitioners’ foreign sales, including purely foreign sales that never reached the United States or confused consumers in the United States.

VIP Prods. LLC v. Jack Daniel’s Props., Inc. , 2022 WL 1654040 (9th Cir. Mar. 18, 2022), cert. granted , 2022 WL 17087471 (U.S. Nov. 21, 2022) (No. 22-148). The Supreme Court granted certiorari on two questions: (1) Whether humorous use of another’s trademark as one’s own on a commercial product is subject to the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood-of-confusion analysis, or instead receives heightened First Amendment protection from trademark-infringement claims? and (2) Whether humorous use of another’s mark as one’s own on a commercial product is “noncommercial” under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3)(C), thus barring as a matter of law a claim of dilution by tarnishment under the Trademark Dilution Revision Act?

The Thorny Issue of Patent Eligibility: Still Under Consideration at the High Court

Interactive Wearables, LLC v. Polar Electro Oy et al. , 2021 WL 4783803 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 14, 2021), petition for cert. filed , 2022 WL 864210 (U.S. Mar. 18, 2022) (No. 21‑1281). The petition for certiorari presents the questions of: (1) What is the standard for determining when a claim is “directed to” a patent-ineligible concept under Alice ? (2) Is patent eligibility (at each step of the Alice inquiry) a question of law or fact? and (3) Whether § 112 considerations can inform the analysis in determining patent eligibility under § 101?

Tropp v. Travel Sentry, Inc. , 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 3906 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 14, 2022), petition for cert. filed , 2022 U.S. S. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2127 (U.S. July 5, 2022) (No. 22-22). The petition for certiorari presents the question of whether claims covering TSA master-key compliant locks used for travel that recite physical steps, rather than computer-processing steps, are patent-eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

In Trademarks, the Standard for Expressive Use Is in Flux

VIP Prods. LLC v. Jack Daniel's Props., Inc. , 2022 WL 1654040 (9th Cir. Mar. 18, 2022), cert. granted , 2022 WL 17087471 (U.S. Nov. 21, 2022) (No. 22-148). See discussion above on upcoming Supreme Court cases.

Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Cases

Nike, Inc. v. StockX LLC , 1:22-cv-00983 (S.D.N.Y. Feb, 3, 2022). Nike alleges trademark infringement where its registered marks are used in NFTs sold by StockX. These NFTs are used as part of an effort to authenticate resold shoes.

Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild , 1:22-cv-00384, 2022 WL 1564597 (S.D.N.Y. May 18, 2022). In a case of first impression, Judge Rakoff denied dismissal of trademark infringement claims where an artist sold NFTs depicting Hermès’ registered mark for handbags.

Yuga Labs, Inc. v. Ryder Ripps et al. , 2:22-cv-04355 (C.D. Cal. June 24, 2022). Yuga has alleged trademark infringement of its marks where the individual defendant sold NFTs intentionally depicting Yuga’s mark in an effort to highlight Yuga’s alleged racism. Ripps filed a motion to dismiss claiming his First Amendment right to free speech trumps any claims of trademark infringement. The motion to dismiss is currently pending.

Large Damages Awarded in Patent Cases Are Being Challenged With Success

Inst. of Tech. v. Broadcom Ltd. , 25 F.4th 976 (Fed. Cir. 2022). The Federal Circuit vacated a $1.1 billion jury award on account of an unsupported two-tier reasonable royalty model and lack of apportionment.

Roche Diagnostics Corp. v. Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC , 30 F.4th 1109 (Fed. Cir. 2022). The Federal Circuit vacated a $137 million damage award, noting that apportionment must be considered on remand.

VLSI Tech. LLC v. Intel Corp. , 6:21-cv-00057, 2022 WL 1477725 (W.D. Tex. May 10, 2022), appeal filed , No. 22-1906 (Fed. Cir. June 15, 2022); VLSI Tech. LLC v. Intel Corp. , 6:19‑cv‑00256 (W.D. Tex. Nov. 15, 2022). VLSI defeated Intel in two out of three patent infringement trials relating to computer chip-making technologies, with VLSI awarded over $3.1 billion in total damages. Intel has appealed the earliest award of $2.1 billion at the Federal Circuit, arguing that VLSI introduced non-comparable licenses and its methodology violates principles of apportionment. An appeal of the recently awarded $949 million is expected in due course.

USPTO Director Will Step in When IPR Parties Act Inappropriately

OpenSky Indus., LLC, Intel Corp., v. VLSI Tech. LLC , IPR2021-01064, 2022 WL 5240856 (P.T.A.B. Oct. 4, 2022). USPTO Director found that OpenSky abused the IPR process and took remedial measures by removing OpenSky from further participation in the IPR proceeding.

Appeal of CRISPR Interference Puts Sufficiency of Conception into Question

Regents of the Univ. of Cal., Univ. of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (“CVC”) v. The Broad Inst. (“Broad”) et al. , Patent Interference No. 106,115, 2022 WL 1664030 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 28, 2022), appeal filed , No. 22-1594 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 4, 2022). This appeal of an Interference decision contests the requirements of conception in determining inventorship of CRISPR gene editing technology as between CVC and Broad.

Current Public Notices

Post Your Public Notice Today!

Current Legal Analysis

More from cadwalader, wickersham & taft llp, upcoming legal education events.

Sign Up for e-NewsBulletins

- --> Login or Sign Up

Shop by Author

- Sabrineh Ardalan

- Robert Bordone

- Robert Clark

- John Coates

- Susan Crawford

- Alonzo Emery

- Heidi Gardner

- Philip B. Heymann

- Howell E. Jackson

- Wendy Jacobs

- Adriaan Lanni

- Jeremy McClane

- Naz Modirzadeh

- Catherine Mondell

- Ashish Nanda

- Charles R. Nesson

- John Palfrey

- Bruce Patton

Todd D. Rakoff

- Lisa Rohrer

- Jeswald W. Salacuse

- James Sebenius

- Joseph William Singer

- Holger Spamann

- Carol Steiker

- Guhan Subramanian

- Lawrence Susskind

- David B. Wilkins

- Jonathan Zittrain

Shop by Brand

- Howell Jackson

- Ashish Nanda and Nicholas Semi Haas

- Chad M. Carr

- John Coates, Clayton Rose, and David Lane

- Ashish Nanda and Lauren Prusiner

- Ashish Nanda and Lisa Rohrer

- Ashish Nanda and Monet Brewerton

- View all Brands

- $0.00 - $1.00

- $1.00 - $2.00

- $2.00 - $2.00

- $2.00 - $3.00

- $3.00 - $4.00

Intellectual Property

- Published Old-New

- Published New-Old

Lotus v. Borland: A Case Study in Software Copyright

Ben Sobel, under the supervision of Jonathan Zittrain

What’s Fair about Fair Use? The Battle over E-Reserves at GSU (B)

Elizabeth Moroney, under the supervision of Kyle Courtney and William Fisher

Prosecutorial Discretion in Charging and Plea Bargaining: The Aaron Swartz Case (B)

Elizabeth Moroney, under the supervision of Adriaan Lanni and Carol Steiker

What’s Fair about Fair Use? The Battle over E-Reserves at GSU (A)

Prosecutorial Discretion in Charging and Plea Bargaining: The Aaron Swartz Case (A)

Elizabeth Moroney, under supervision of Adriaan Lanni and Carol Steiker

Sue the Consumer: Digital Copyright in the New Millennium

Charles Nesson and Sarah Jeong

Ching Pow: Far East Yardies!!

Charles Nesson and Saptarishi Bandopadhyay

From Sony to SOPA: The Technology-Content Divide

John Palfrey, Jonathan Zittrain, Kendra Albert, and Lisa Brem

Drafting an IP Strategy at MNC (C): New Puzzles

John Palfrey and Lisa Brem

Drafting an IP Strategy at MNC (B): Getting Started

Drafting an IP Strategy at MNC (A)

Pandora's Box

Mark Freeman

Iqbal's Big Venture

Robert C. Bordone and Tobias C. Berkman

The Case of the Medical Stent

5 Leading Cases of Intellectual Property Rights

In this article, the author has discussed 5 leading case laws under patent law, copyright law, and trademarks law..

5 Leading Cases of Intellectual Property Rights | Overview

- Bayer Corporation v. Union of India

- Diamond v. Chakrabarty

- Yahoo! Inc. vs. Akash Arora & Anr

- The Coca-Cola Company v. Bisleri International Pvt. Ltd. and Ors

- D.C. Comics v. Towle

Introduction

Intellectual Property Rights has proved itself to be invaluable in all senses in the socio-economic fields in the world. It has gained immense popularity in the recent past. It is what motivates people to create and innovate. Things which are governed by Intellectual property laws are creations of the mind. In this article, the author has have discussed 5 leading case laws under Patent Law, Copyright Law, and Trademarks Law.

1. Bayer Corporation v. Union of India [1]

This landmark judgment is the first-ever case in India dealing with the granting of a compulsory license under an application made under Section 84 of the Patents Act, 1970.

The petitioner, Bayer Corporation Ltd incorporated in the USA invented and developed a drug named ‘Nexavar (Sorafenib Tosylate)’ used in the treatment of persons suffering from Kidney Cancer (RCC). The drug was granted an international patent in 45 countries including India. Under normal circumstances, a third party can manufacture and sell the patented drug only with the permission or license granted by the patent holder.

Natco, a drug manufacturer had approached Bayer for a grant of a voluntary license to manufacture and sell the drug at a much lower price of Rs. 10,000/- per month of therapy as against the price of Rs. 2, 80,428/- per month of therapy charged by the petitioner.

The request was denied and hence they made an application to the Controller under section 84 of the Act for a compulsory license on the ground that the petitioner had not met the reasonable requirement of the public in respect of the patented drug. It was granted on the condition that the applicant had to sell the drug at Rs 8,800/- per month and was directed to pay 6% of the total sale as royalty to the petitioner. [2] Natco was also directed to sell the drug only in India and to make the drug available to at least 600 needy patients each year free of charge.

Aggrieved by the order, the petitioner approached the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) contending that the order passed was contrary to the provisions of the Act since the drug was made available at a lower price by Cipla. The board, however, rejected the contention by holding that the drug was not made available at a cheaper price by the petitioner and that the petitioner’s stance was detrimental to the public at large who are in need of the drug. Hence, the petitioner preferred an appeal in the High Court. [3]

Issues Involved

The major issues for consideration by the High Court were:

- Has the requirements under Section 84(1) been satisfied for granting a compulsory license?

- Whether supplies by infringers of a patented drug to be considered/taken into account to determine the satisfaction of reasonable requirement test?

With regard to Issue No.1, the Court held that all the three requirements under clauses (a), (b) and (c) of Section 84(1) for granting compulsory license has been satisfied in this case.

The court opined that the question of whether the reasonable requirement of the public has been satisfied under Section 84(1) (a) is to be determined after examining the evidence produced by both parties.

In the present case, after examining the figures given by the Petitioner in affidavits it is clear that the requirements haven’t been met by the petitioner. It was held that the dual pricing system under the Patient Assistance Programme would not satisfy the conditions of Section 84(1) (b) and hence the drug was not considered to be available at a reasonable price to the public. [4]

On the question of whether the patented drug has been worked in the territory of India, the Court held that when a patent holder is faced with an application for a Compulsory License , it is for a patent holder to show that, the patented invention/drug is worked in the territory of India by the manufacturer or otherwise. It is not compulsory that “ Worked in India ” should include “ manufacture ” if the patent holder can furnish valid reasons before the authorities for not manufacturing in India keeping Section 83 of the Act in mind.

- On Issue No. 2, the Court answered the question negatively and held that the supply by the infringers, Cipla and Natco could not be taken into account since their supply could stop any day. It is only when the patent holder grants a de facto license could infringer’s supplies be taken into account. The obligation to meet a reasonable requirement of the public is of a patent holder alone either by itself or through its licensees.

- Section 84(7) of the Act, provides a deeming fiction which provides that the reasonable requirement of the public is not satisfied, if the demand for a patented article is not met to an adequate extent in which regard the patent holder has failed in the present case.

The decision, in this case, will go a long way to ensure that the interests of the public are drowned by reason of the personal interests of the patent holder in necessary circumstances.

2. Diamond v. Chakrabarty [5]

This was the historical decision in which the US Supreme Court considered the patentability of a living micro-organism. The decision is one which will have a huge impact in the field of Biotechnology.

Ananda Chakrabarty, a microbiologist filed patent claims for human-made, genetically engineered bacterium that was capable of breaking down multiple components of crude oil. A patent examiner rejected the patent because it was outside of the scope of the patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101 .

The Patent Office Board of Appeals affirmed and ruled that living things are not patentable subject matter under Section 101. The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals reversed this decision holding that the fact that micro-organisms are alive is insignificant for the purpose of patent law. [6] Diamond, the Commissioner of Patents, petitioned the United States Supreme Court for certiorari against the decision of the Court of Appeals.

Issue Involved

The main issue before the Court was whether the respondent’s micro-organism plainly qualifies as patentable subject matter.

Arguments Raised by the Appellant

Diamond raised the argument that with the enactment of the Plant Patent Act, 1930 and Plant Variety Protection Act, 1970 Congress implicitly understood that living organisms were not within the scope of 35 U.S.C. §101. He also relied upon the judgment in Parker v. Flook [7] wherein it was held that courts should show restraint before expanding protection under 35 U.S.C. §101 into new, unforeseen areas. [8]

Section 101 of Title 35 U.S.C. provides for the issuance of a patent to a person who invents or discovers “any” new and useful “manufacture” or “composition of matter.” The court held that a live, human-made micro-organism is a patentable subject matter under Section 101 and that the respondent’s microorganism constituted a “manufacture” or “composition of matter under the statute. The court opined that the organism was a product of human ingenuity “having a distinctive name, character, and use”. [9]

Moreover, the Court rejected the appellant’s argument by holding that the patent protection afforded under the Plant Patent Act, 1930 and Plant Variety Protection Act, 1970 was not evidence of Congress’ intention to exclude living things from being patented. The court pointed out that genetic technology was not foreseen by Congress do not make it non-patentable unless expressly provided. The Court held that the language of the Act was wide enough to embrace the respondent’s invention. [10]

3 . Yahoo ! Inc. vs. Akash Arora & Anr [11]

This landmark judgment is the first case relating to cybersquatting in India. Cybersquatting has been defined as the registration, trafficking in, or use of a domain name that is either identical or confusingly similar to a distinctive trademark or is confusingly similar to or dilutive of a famous trademark. [12]

The plaintiff is a global internet media who is the owner of the trademark ‘Yahoo!’ and the domain name ‘Yahoo.Com’ , which are very well-known and render services under its domain name. While the application of the plaintiff for registration of the trademark was pending in India, the defendant Akash Arora started providing similar services under the name ‘Yahoo India’ .

The present case is brought out by the plaintiff for passing off the services and goods of the defendants as that of the plaintiff by using a name which is identical to or deceptively similar to the plaintiff’s trademark ‘Yahoo! ‘ and prayed for a permanent injunction to prevent the defendant from continuing to use the name.

- Whether an action for passing off could be maintained against services rendered?

- Whether a domain name is protected under the Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, of 1958?

- Whether the use of a disclaimer by the defendant will eliminate the problem?

The Delhi High Court extensively examined the issues and rejected the defendant’s contention that an action for passing off could only be brought against goods and not services rendered by virtue of Section 2(5), Sections 27, 29 and Section 30 of the Act. It was held that the passing off action could be maintained against the service, as the service rendered could be recognized for the action of passing off.

The law relating to passing off is well-settled and clear. The principle behind the same is that no man can carry on his business in a way that can lead to believing that he is carrying on the business of another man or has some connection with another man for the business. [14] The plaintiff is entitled to relief under Section 27(2) and Section 106 of the Act which is governed by principles of Common law.

The Court relied upon the landmark judgment of Monetary Overseas v. Montari Industries Ltd. and reiterated that “When a defendant does business under a name which is sufficiently close to the name under which the plaintiff is trading and that name has acquired a reputation and the public at large is likely to be misled that the defendant’s business is the business of the plaintiff, or is a branch or department of the plaintiff, the defendant is liable for an action in passing off.” [15]

- With regard to Issue No. 2, the Hon’ble Court relied on the US case Card Service International Inc. vs. McGee [16] , and held that the domain name serves the same function as a trademark and is hence entitled to the same protection.

- While discussing the impact of the disclaimer issued by the defendant, the Court held that it would not eliminate the problem because of the nature of Internet use. [17] The users might not be sophisticated enough to understand the slight difference in the domain name to distinguish between the two.

The Court addressed each of these issues and came to the conclusion that Yahoo Inc. had a good reputation in the market and that the name adopted by the defendants were deceptive and misleading causing damage to the reputation of the plaintiff and undue gain for the defendants. In consequence, the court granted an injunction in favour of the plaintiff under Rules 1 and 2 of Order 39 of CPC, 1908.

4. The Coca-Cola Company v. Bisleri International Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. [18]

This case is better known as the " MAAZA War case ". This was decided by the Delhi Court.

The plaintiff (Coca-Cola) is the largest brand of soft drinks operating in 200 countries whereas Defendant No1 earlier known as Acqua Minerals Pvt. Ltd. used to be a part of the Parle Group of Industries. The owners of Bisleri had sold the trademarks, formulation rights, know-how, intellectual property rights, and goodwill etc. of their product MAAZA amongst others to the plaintiff by a master agreement.

In March 2008, when the plaintiff filed for registration of the MAAZA trademark in Turkey, the defendant sent a legal notice repudiating the Licensing Agreement thereby ceasing the plaintiff from manufacturing MAAZA and using its trademarks etc. directly or indirectly, by itself or through its affiliates. In consequence, the plaintiff claimed permanent injunction and damages for infringement of trademark and passing off. The plaintiff also alleged that the defendant had unauthorisedly permitted the manufacture of certain ingredients of the beverage bases of MAAZA to be manufactured by a third party in India. [19]

- Does the Delhi High Court have jurisdiction in the present case?

- Is there any infringement of the trademark or passing off?

- Is the plaintiff entitled to get a permanent injunction?

It was held that the Court had jurisdiction to decide the case if a threat of infringement exists. It was pointed out that an intention to use the trademark besides direct or indirect use of the trademark was sufficient to give jurisdiction to the court to decide on the issue. [20]

The court held that it is a well-settled position of law that exporting products from a country is to be considered as a sale within the country wherefrom the goods are exported and it amounts to infringement of the trademark.

The Court granted an interim injunction against the defendant from using the mark in India as well as in the export market to prevent the plaintiff from irreparable loss and injury and quashed the appeal by the defendant. [21]

5. D.C. Comics v. Towle [22]

This very interesting case is a recent landmark judgment in the field of copyright law.

Facts of the Case

DC Comics (DC) is the publisher and copyright owner of comic books featuring the story of the world-famous character, Batman. Originally introduced in the Batman comic books in 1941, the Batmobile is a fictional, high-tech automobile that Batman employs as his primary mode of transportation. The Batmobile has varied in appearance over the years, but its name and key characteristics as Batman’s personal crime-fighting vehicle have remained consistent.

Since its creation in the comic books, the Batmobile has also been depicted in numerous television programs and motion pictures. Two of these depictions are relevant to this case: the 1966 television series Batman, starring Adam West, and the 1989 motion picture Batman, starring Michael Keaton.

Defendant Mark Towle produces replicas of the Batmobile as it appeared in both the 1966 television show and 1989 motion picture as part of his business at Gotham Garage, where he manufactures and sells replicas of automobiles featured in motion pictures or television programs for approximately “avid car collectors” who “know the entire history of the Batmobile .” Towle also sells kits that allow customers to modify their cars to look like the Batmobile , as it appeared in the 1966 television show and the 1989 motion picture.

DC filed this action against Towle, alleging, among other things, causes of action for copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and unfair competition arising from Towle’s manufacture and sale of the Batmobile replicas. The district court passed a summary judgment in favour of DC.

Summary of Judgment

The main question for consideration is whether BATMOBILE is entitled to copyright protection. The Court of Appeal relied on a number of historical decisions in deciding this case. The court held that copyright protection extends not only to the original work as a whole but also to “sufficiently distinctive” elements, like comic book characters, contained within the work. [23]

Although comic book characters are not listed in the Copyright Act, courts have long held that, as distinguished from purely “literary” characters, comic book characters, which have “physical as well as conceptual qualities”, are copyrightable. [24] The court relied on the judgment in Hachiki’s case [25] where it was held that automotive character can be copyrightable. Moreover, it has been held that copyright protection can apply for a character even if the character’s appearance changes over time. [26]

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in this case, developed a three-part test for determining protection of a character appearing in comic books, television programs or films under the 1976 Copyright Act, independent of any specific work in which it has appeared and irrespective of whether it “lacks sentient attributes and does not speak” as explained above. [27]

The court held that the present case satisfied the three-part test DC had the right to bring suit because it had reserved all merchandising rights when it granted licenses for the creation of the 1966 Batman television series and the 1989 Batman film.

It was held that the 1966 program and 1989 film were derivative works of the original Batman comics and that any infringement of those derivative works also gave rise to a claim for DC, the copyright owner of the underlying works.

It was found that Towle’s replicas infringed upon DC’s rights hence the Court also upheld the District Court’s refusal to allow Towle to assert a laches defense on DC’s trademark claims because the infringement was found to be willful. [28]

The law relating to intellectual property is constantly evolving all around the world. Being a relatively new concept, there are many areas which still need development and protection of the laws. All the above-mentioned case laws have a wide impact on society. They have brought about major breakthroughs in IP law.

Originally Published: May 26, 2019

[1] AIR 2014 Bom 178

[2] www.manupatra.com

[3] LANDMARK JUDGEMENTS IN PATENT LAW, Available at http://www.talwaradvocates.com/landmark-judgements-patent-law/

[4] BAYER CORP. V. UNION OF INDIA, Available at http://www.indialaw.in/blog/blog/intellectual-property-rights/bayer-corp-v-union-of-india/

[5] 447 U.S. 303, 100 S. Ct. 2204 (1980)

[6] DIAMOND v. CHAKRABARTY (1980), Available at https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/447/303.html

[7] 437 U.S. 584 (1978)

[8] Diamond v. Chakrabarty, Available at https://www.quimbee.com/cases/diamond-v-chakrabarty

[9] Hartranft v. Wiegmann, 121 U.S. 609, 615

[10] https://www.lexisnexis.com/lawschool/resources/p/casebrief-diamond-v-chakrabarty.aspx

[11] 1999(19) PTC 201 (Del)

[12] Anti-cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (15 U.S.C. 1125(d))

[13] Hereinafter referred to as the ‘Act’.

[14] MANU/DE/0120/1999

[15] 1996 PTC 142

[16] 42 USPQ 2d 1850

[17] Jesus Vs. Brodsky, 46 USPQ 2d 1652

[18] MANU/DE/2698/2009

[19] www.lexquest.com

[20] Case analysis: Coca-Cola Co. Vs. Bisleri International Pvt. Ltd, Available at https://brandsandfakes.com/case-analysis-coca-cola-co-vs-bisleri-international-pvt-ltd/135/

[21] LANDMARK JUDGEMENTS IN TRADEMARKS LAW, Available at http://www.talwaradvocates.com/5-landmark-judgements-trademarks-law/

[22] MANU/FENT/2518/2015

[23] Halicki Films, LLC v. Sanderson Sales & Mktg, 547 F.3d 1213, 1224 (9th Cir. 2008)

[24] Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, 581 F.2d 751 (9th Cir. 1978).

[25] Halicki Films, LLC v Sanderson Sales & Marketing, 547 F.3d 1213 (9th Cir. 2008).

[26] Toho Co., Ltd. v. William Morrow & Co., Inc., 33 F.Supp.2d 1206 (C.D. Cal. 1998)

[27] http://www.frosszelnick.com/dc-comics-v-towle

- Five Landmark Decisions in Indian Tort Law – by Tanishka Goswami (Opens in a new browser tab)

- Intellectual Property Rights

Fathima Mehendi

5th Year law student at National University of Advanced Legal Studies (NUALS), Kochi

Related News

Case Studies

Collegiate Licensing

Follow on Biologics

InnoCentive

Museum Licensing

Smartphones

University Licensing

1. Collegiate Licensing

Intellectual property accounts for about 40% of the net asset value of all corporations in America. 1 One clear method of extracting value from these assets is by entering the licensing market for trademarks and copyrights which, globally, involves $100 billion per year. But the potential of this market is not limited to traditional firms and for-profit enterprises. Companies specializing in collegiate-sports licensing have been helping colleges and universities maximize revenue through licensing deals. Given that they are institutions that specialize in the creation and cultivation of knowledge and expression, colleges and universities should naturally be attuned to the potential that exists in these intellectual property-related activities.

2. Follow-on Biologics

The rise of generic pharmaceuticals has resulted in large price reductions and numerous opportunities for large and small drug companies. Now, provisions in the new comprehensive health care law combined with a wave of patent expirations on major biologics are opening the door to companies interested in pursuing generic versions of brand-name biologics, known as follow-on biologics or biosimilars. Perhaps the best example is the case of Merck’s investment in and creation of a follow-on biologics unit, Merck BioVentures.

3. InnoCentive

Whether you call it “crowdsourcing,” 2 “open innovation,” 3 or “the wisdom of crowds,” 4 the collaborative approach to innovation is becoming a force. It is an increasingly common tactic employed by businesses, individual inventors, and government bodies. After having set aside any sense of paranoia about protecting their intellectual property rights, these leaders are turning to customers, competitors, and even the public at large for inspiration in solving a host of technological and design problems.

More often, firms turn to companies like IdeaWicket , NineSigma , and Napkin Labs , all of whom act as innovation “middlemen” by connecting seekers with solvers. The best-known of these entities is InnoCentive , a company founded within Eli Lilly in 2001 that became independent in 2005. InnoCentive strives to “help companies innovate better, to find the fastest path to solutions.” 5 Firms that want to take advantage of InnoCentive’s services first post a project by constructing a detailed list of their goals. Then, InnoCentive’s community selects projects to “solve” from among those listed. The result can be hundreds of ideas for the firm’s technological or design problems. 6 Prize money for the best ideas, which serves as an inducement for the problem solvers, ranges from $5,000 to $1 million. 7 The solvers come from 175 countries. More than one third have doctorates. 8

Dwayne Spradlin, president and chief executive of InnoCentive, says that, for many companies, embracing open innovation requires a large cultural shift. 9 Two particular concerns are that companies that post information about their problems risk giving valuable information to competitors, or that a solver will devise a useful solution but refuse to hand it over to the organization that initially sought it. 10 So far, neither concern has materialized. 11 In fact, InnoCentive appears to have been remarkably successful. Giants like Procter & Gamble and even the United States government have turned to the InnoCentive community for help in solving their problems.

4. Museum Licensing