- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

The Systematic Review

An overview.

Aromataris, Edoardo PhD; Pearson, Alan PhD, RN

Edoardo Aromataris is the director of synthesis science at the Joanna Briggs Institute in the School of Translational Health Science, University of Adelaide, South Australia. Alan Pearson is the former executive director and founder of the Joanna Briggs Institute. Contact author: Edoardo Aromataris, [email protected] . The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

The Joanna Briggs Institute aims to inform health care decision making globally through the use of research evidence. It has developed innovative methods for appraising and synthesizing evidence; facilitating the transfer of evidence to health systems, health care professionals, and consumers; and creating tools to evaluate the impact of research on outcomes. For more on the institute's approach to weighing the evidence for practice, go to http://joannabriggs.org/jbi-approach.html .

This article is the first in a new series on systematic reviews from the Joanna Briggs Institute, an international collaborative supporting evidence-based practice in nursing, medicine, and allied health fields. The purpose of the series is to show nurses how to conduct a systematic review—one step at a time. This first installment provides a synopsis of the systematic review as a scientific exercise, one that influences health care decisions.

This first article in a new series from the Joanna Briggs Institute provides a synopsis of the systematic review as a scientific exercise, and introduces nurses to the steps involved in conducting one.

Research in the health sciences has provided all health care professions, including nursing, with much new knowledge to inform the prevention of illness and the care of people with ill health or trauma. As the body of research has grown, so too has the need for rigorous syntheses of the best available evidence.

Literature reviews have long been a means of summarizing and presenting overviews of knowledge, current and historical, derived from a body of literature. They often make use of the published literature; generally, published papers cited in a literature review have been subjected to the blind peer-review process (a hallmark of most scientific periodicals). The literature included in a literature review may encompass research reports that present data, as well as conceptual or theoretical literature that focuses on a concept. 1

An author may conduct a literature review for a variety of reasons, including to 1

- present general knowledge about a topic.

- show the history of the development of knowledge about a topic.

- identify where evidence may be lacking, contradictory, or inconclusive.

- establish whether there is consensus or debate on a topic.

- identify characteristics or relationships between key concepts from existing studies relevant to the topic.

- justify why a problem is worthy of further study.

All of these purposes have been well served by a “traditional” or “narrative” review of the literature. Traditional literature reviews, though useful, have major drawbacks in informing decision making in nursing practice. Predominantly subjective, they rely heavily on the author's knowledge and experience and provide a limited, rather than exhaustive, presentation of a topic. 2 Such reviews are often based on references chosen selectively from the evidence available, resulting in a review inherently at risk for bias or systematic error. Traditional literature reviews are useful for describing an issue and its underlying concepts and theories, but if conducted according to no stated methodology, they are difficult to reproduce—leaving the findings and conclusions resting heavily on the insight of the authors. 1, 2 In many cases, the author of the traditional review discusses only major ideas or results from the studies cited rather than analyzing the findings of any single study.

With the advent of evidence-based health care some 25 years ago, nurses and other clinicians have been expected to refer to and rely on research evidence to inform their decision making. The need for evidence to support clinical practice is constantly on the rise because of advances that continually expand the technologies, drugs, and other treatments available to patients. 3 Nurses must often decide which strategies should be implemented, yet comparisons between available options may be difficult to find because of limited information and time, particularly among clinical staff. Furthermore, interpreting research findings as presented in scientific publications is no easy task. Without clear recommendations for practice, it can be difficult to use evidence appropriately; it requires some knowledge of statistics and in some cases extensive knowledge or experience in how to apply the evidence to the clinical setting. 4 Also, many health care devices and drugs come with difficult-to-understand claims of effectiveness. 5

As a result of research, the knowledge on which nursing care is based has changed at a rapid pace. This inexorable progress means that nurses can access biomedical databases containing millions of citations pertinent to health care; these databases are growing at a phenomenal rate, with tens of thousands of publications added every year. The volume of literature is now too vast for nurses and other health care professionals to stay on top of. 3 Furthermore, not all published research is of high quality and reliable; on the contrary, many published studies have used inappropriate statistical methods or have otherwise been poorly conducted.

Such issues affecting research quality can make for research findings that are contradictory or inconclusive. Similarly, using the results of an individual study to inform clinical decision making is not advisable. When compared with other research on the topic, a study may be at risk for bias or systematic error. 5 Therefore, it can be difficult for nurses to know which studies from among the multitude available should be used to inform the decisions they make every day. As a result, reviews of the literature have evolved to become an increasingly important means by which data are collected, assessed, and summarized. 5-7

THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Since the traditional literature review lacks a formal or reproducible means of estimating the effect of a treatment, including the size and precision of the estimate, 2, 7 a considerably more structured approach is needed. The “systematic review,” also known as the “research synthesis,” aims to provide a comprehensive, unbiased synthesis of many relevant studies in a single document. 2, 7, 8 While it has many of the characteristics of a literature review, adhering to the general principle of summarizing the knowledge from a body of literature, a systematic review differs in that it attempts to uncover “all” of the evidence relevant to a question and to focus on research that reports data rather than concepts or theory. 3, 9

As a scientific enterprise, a systematic review will influence health care decisions and should be conducted with the same rigor expected of all research. Explicit and exhaustive reporting of the methods used in the synthesis is also a hallmark of any well-conducted systematic review. Reporting standards similar to those produced for primary research designs have been created for systematic reviews. The PRISMA statement, or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, provides a checklist for review authors on how to report a systematic review. 10 Ultimately, the quality of a systematic review, and the recommendations drawn from it, depends on the extent to which methods are followed to minimize the risk of error and bias. For example, having multiple steps in the systematic review process, including study selection, critical appraisal, and data extraction conducted in duplicate and by independent reviewers, reduces the risk of subjective interpretation and also of inaccuracies due to chance error affecting the results of the review. Such rigorous methods distinguish systematic reviews from traditional reviews of the literature.

The characteristics of a systematic review are well defined and internationally accepted. The following are the defining features of a systematic review and its conduct:

- clearly articulated objectives and questions to be addressed

- inclusion and exclusion criteria, stipulated a priori (in the protocol), that determine the eligibility of studies

- a comprehensive search to identify all relevant studies, both published and unpublished

- appraisal of the quality of included studies, assessment of the validity of their results, and reporting of any exclusions based on quality

- analysis of data extracted from the included research

- presentation and synthesis of the findings extracted

- transparent reporting of the methodology and methods used to conduct the review

Different groups worldwide conduct systematic reviews. The Cochrane Collaboration primarily addresses questions on the effectiveness of interventions or therapies and has a strong focus on synthesizing evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (see http://handbook.cochrane.org ). 9 Other groups such as the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York ( http://bit.ly/1g9WoCq ) and the Joanna Briggs Institute ( http://joannabriggs.org ) include other study designs and evidence derived from different sources in their systematic reviews. The Institute of Medicine issued a report in 2011, Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews , which makes recommendations for ensuring “objective, transparent, and scientifically valid reviews” (see http://bit.ly/1cRIAg7 ).

How systematic reviews are conducted may vary; the methods used will ultimately depend on the question being asked. The approach of the Cochrane Collaboration is almost universally adopted for a clear-cut review of treatment effectiveness. However, specific methods used to synthesize qualitative evidence in a review, for example, may depend on the preference of the researchers, among other factors. 7 The steps for conducting a systematic review will be addressed below and in greater detail throughout this series.

Review question and inclusion criteria. Systematic reviews ideally aim to answer specific questions, rather than present general summaries of the literature on a topic of interest. 5, 8 A systematic review does not seek to create new knowledge but rather to synthesize and summarize existing knowledge, and therefore relevant research must already exist on the topic. 3, 5 Deliberation on the question occurs as a first step in developing the review protocol. 5, 7 Nurses accustomed to evidence-based practice and database searching will be familiar with the PICO mnemonic (Population, Intervention, Comparison intervention, and Outcome measures), which helps in forming an answerable question that encompasses these concepts to aid in the search. 3, 8, 11 (The art of formulating the review question will be covered in the second article of this series.)

Ideally, the review protocol is developed and published before the systematic review is begun. It details the eligibility of studies to be included in the review (based on the PICO elements of the review question) and the methods to be used to conduct the review. Adhering to the eligibility criteria stipulated in the review protocol ensures that studies selected for inclusion are selected based on their research method, as well as on the PICO elements of the study, and not solely on the study's findings. 3 Conducting the review in such a fashion limits the potential for bias and reduces the possibility of altering the focus or boundaries of the review after results are seen. In addition to the PICO elements, the inclusion criteria should specify the research design or types of studies the review aims to find and summarize, such as RCTs when answering a question on the effectiveness of an intervention or therapy. 9 Stipulating “study design” as an extra element to be included as part of the inclusion criteria changes the standard PICO mnemonic to PICOS.

Searching for studies can be a complex task. The aim is to identify as many studies on the topic of interest as is feasible, and a comprehensive search strategy must be developed and presented to readers. 3, 10 A strategy that increases in complexity is common, starting with an initial search of major databases, such as MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), using keywords derived from the review question. This preliminary search helps to identify optimal search terms, including further keywords and subject headings or indexing terms, which are then used when searching all relevant databases. Finally, a manual search is conducted of the reference lists of all retrieved papers to identify any studies missed during the database searches. The search should also target unpublished studies to help minimize the risk of publication bias 3, 5 —a reality that review authors have to acknowledge. It arises because researchers are more likely to submit for publication positive rather than negative findings of their research, and scientific journals are inclined to publish studies that show a treatment's benefits. Therefore, relying on findings only from published studies may result in an overestimation of the benefits of an intervention. To date, locating unpublished studies has been difficult, but resources for locating this “gray” literature are available and increasing in sophistication. For example, Web search engines can search across many governmental and organizational sites simultaneously. Similarly, there are databases that index graduate theses and doctoral dissertations, abstracts of conference proceedings, and reports that aren't commercially published. Contacting experts in the field may also yield otherwise difficult-to-obtain information. Finally, studies published in languages other than English should be included, if possible, despite the added cost and complexity of doing so. (The art of searching will be addressed in the third paper in this series.)

Study selection and critical appraisal. The PICO elements can aid in defining the inclusion criteria used to select studies for the systematic review. The inclusion criteria place the review question in a practical context and act as a clear guide for the review team as they determine which studies should be included. 3 This step is referred to as study selection . 8 Once it's determined which studies should be included, their quality must be assessed during the step of critical appraisal . (Both of these steps will be further addressed in the fourth paper in this series.)

During study selection , reviewers look to match the studies found in the search to the review's inclusion criteria—that is, they identify those studies that were conducted in the correct population, use interventions of interest, and record the predetermined and relevant outcomes. 3 The optimal research design for answering the review question is also determined. For example, for a systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention, the most reliable evidence is thought to come from RCTs, which allow the inference of causal associations between the intervention and outcome, rather than from other study designs such as the cohort study, which lacks randomization and experimental “control.” Any exclusion criteria should also be documented—for example, specific populations or modes of delivery of an intervention.

During critical appraisal , all studies to be included are first assessed for methodologic rigor. 3 Although there are some subtle differences, this appraisal is akin to assessing the risk of bias in reviews that ask questions related to the effectiveness of an intervention. A systematic review aims to synthesize the best evidence for clinical decision making. Assessing the validity of a study requires careful consideration of the methods used during the research and establishing whether the study can be trusted to provide a reliable and accurate account of the intervention and its outcomes. 5-8 Studies that are of low or questionable quality are generally excluded from the remainder of the review process. Exclusion of lesser-quality studies reduces the risk of error and bias in the findings of the review. 3 For the most part, critical appraisal focuses squarely on research design and the validity and hence the believability of the study's findings rather than on the quality of reporting, which depends on both writing style and presentation. 10 For example, when assessing the validity of an RCT, critical appraisal generally focuses on four types of systematic error that can occur at different stages of a study: selection bias (in considering how study participants were assigned to the treatment groups), performance bias (in considering how the intervention was provided), attrition bias (in considering participant follow-up and drop-out), and detection bias (in considering how outcomes were measured). 3

To aid the transparency and reproducibility of this process in the systematic review, standardized instruments (checklists, scales) are commonly used when asking the reviewers about the research they are reading.

Data extraction and synthesis. Once the quality of the research has been established, relevant data aligned to the predetermined outcomes of the review must be extracted for the all-important synthesis of the findings. (These steps will be addressed in the fifth paper in this series.) Data synthesized by systematic reviews are the results extracted from the individual research studies; as with critical appraisal, data extraction is often facilitated by the use of a tool or instrument that ensures that the most relevant and accurate data are collected and recorded. 3 A tool may prompt the reviewer to extract relevant citation details, details of the study participants including their number and eligibility, descriptive details of the intervention and comparator used in the study, and the all-important outcome data. Generic extraction tools for both quantitative and qualitative data are readily available. 12 The data collected from individual studies vary with each review, but they should always answer the question posed by the review. While undertaking a review, reviewers will find that data extraction can be quite difficult—often complicated by factors of the included studies such as incomplete reporting of study findings and differing ways of reporting and presenting data. When these issues arise, reviewers should attempt to contact the authors to obtain missing data, particularly for recently published research. 5

Data synthesis is a principal feature of the systematic review. 3, 6, 7, 9 There are various methods available, depending on the type of data extracted that's most appropriate to the review question. 7 An example of a systematic review addressing a question of the effectiveness of a nursing intervention is one examining nurse-led cardiac rehabilitation programs following coronary artery bypass graft surgery; the review aims to give an overall estimate of the intervention's effectiveness on patients’ health-related quality of life and hospital readmission rates. 13 Depending on the question asked, such a synthesis of the results of relevant studies also allows for exploration of similarities or inconsistencies of the treatment effect in different studies and among various settings and populations. 5 Where inconsistencies are apparent they can be analyzed further. The synthesis either provides a narrative summary of the included studies or, where possible, statistically combines data extracted from the studies. This pooling of data is termed “meta-analysis.” 14

A meta-analysis may be included in a systematic review as a practical way of evaluating many studies. Meta-analysis should ideally be undertaken only when studies are similar enough; studies should sample from similar populations, have similar objectives and aims, administer the intervention of interest in a similar fashion, and (most important) measure the same outcomes. 3 Meta-analysis is rarely appropriate when such similarities do not appear across studies. Meta-analysis requires transforming the findings of treatment effect from individual studies into a common metric and then using statistical procedures across all of the findings to determine whether there is an overall effect of the treatment or association. 8, 9, 14 The typical output from a statistical synthesis of studies is the measure or estimate of effect; the confidence interval, which indicates the precision of the estimate; and the quantification of the differences (heterogeneity) between the included studies and the statistical impact of these differences, if any, on the analysis. There are many different statistical methods by which results from individual studies can be combined during the meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis are commonly displayed as a forest plot, which gives the reader a visual comparison of the findings.

Owing to the limited availability of relevant trials, reviews that aim to examine the effectiveness of an intervention may resort to evidence from experimental studies other than RCTs and even from observational studies; such reviews have the potential to play a greater role in evidence-based nursing, where trials, historically, have been rare. 15 But when conducting a systematic review of studies using designs other than the RCT, a reviewer must take into account the biases inherent in those designs and make definitive recommendations about the effectiveness of a practice with caution.

Other types of evidence, including qualitative evidence and economic evidence addressing questions related to health care costs, can also be synthesized using methods established by organizations such as the Joanna Briggs Institute. 12 While the methods of synthesizing quantitative data are relatively straightforward and accepted, there are numerous methods for synthesizing qualitative research. Such reviews may appear as a meta-synthesis, a meta-aggregation, a meta-study, or a meta-ethnography 7, 16 ; the differences between these approaches will be discussed in the fifth article in this series.

A systematic review that addresses both quantitative and qualitative studies, as well as theoretical literature, is referred to as an “integrative” or “comprehensive” systematic review. 6, 15 The motivation for conducting a comprehensive review is often to provide further insight into why an intervention appears to have a benefit (or not). “Realist” reviews, another emerging form of evidence synthesis, often look to answer questions surrounding complex interventions, including how and for whom an intervention works. 7, 16 Formalized methods for these types of reviews are still being validated.

Interpretation of findings and recommendations to guide nursing practice. The conclusions of the systematic review, along with recommendations for clinical practice and implications for future research, should be based on its findings. Questions to ask when considering the recommendations of a systematic review include the following: Has a clear and accurate summary of findings been provided? Have specific directives for further research been proposed? Are the recommendations, both for practice and future research, supported by the data presented? (Such issues will be explored in the sixth and last paper in this series.)

Reviewers must consider the quality of the studies when arriving at recommendations based on the results of those studies. For example, if the best available evidence was of low quality or only observational studies were available to answer a question of effectiveness, results based on this evidence must be interpreted with caution.

Nurses are increasingly expected to make evidence-based decisions in their practice, and nursing researchers are increasingly driven to develop advanced methods of evidence synthesis. Systematic reviews aim to summarize the best available evidence using rigorous and transparent methods. We've provided a brief introduction to the steps taken in conducting a systematic review; the remaining papers in this series will explore each step in greater detail, addressing the synthesis of both quantitative and qualitative evidence.

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based..., skin assessment in patients with dark skin tone, evidence-based practice, step by step: asking the clinical question: a key step ..., jbi's systematic reviews: data extraction and synthesis, systematic reviews: constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Bashir Y, Conlon KC. Step by step guide to do a systematic review and meta-analysis for medical professionals. Ir J Med Sci. 2018; 187:(2)447-452 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1663-3

Bettany-Saltikov J. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide.Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2012

Bowers D, House A, Owens D. Getting started in health research.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011

Hierarchies of evidence. 2016. http://cjblunt.com/hierarchies-evidence (accessed 23 July 2019)

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2008; 3:(2)37-41 https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Developing a framework for critiquing health research. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/y3nulqms (accessed 22 July 2019)

Cognetti G, Grossi L, Lucon A, Solimini R. Information retrieval for the Cochrane systematic reviews: the case of breast cancer surgery. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015; 51:(1)34-39 https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_15_01_07

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC Users' guides to the medical literature IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. JAMA. 1995; 274:(22)1800-1804 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530220066035

Hanley T, Cutts LA. What is a systematic review? Counselling Psychology Review. 2013; 28:(4)3-6

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (accessed 23 July 2019)

Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. How to conduct a systematic review: a narrative literature review. Cureus. 2016; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.864

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997; 33:(1)159-174

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:(7) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mueller J, Jay C, Harper S, Davies A, Vega J, Todd C. Web use for symptom appraisal of physical health conditions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19:(6) https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6755

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016; 21:(4)125-127 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 2012. http://nice.org.uk/process/pmg4 (accessed 22 July 2019)

Sambunjak D, Franic M. Steps in the undertaking of a systematic review in orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop. 2012; 36:(3)477-484 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1460-y

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019; 70:747-770 https://doi.org/0.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Wallace J, Nwosu B, Clarke M. Barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a systematic review of decision makers' perceptions. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001220

Carrying out systematic literature reviews: an introduction

Alan Davies

Lecturer in Health Data Science, School of Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester

View articles · Email Alan

Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of evidence for a specific topic of interest, summarising the results of multiple studies to aid in clinical decisions and resource allocation. They remain among the best forms of evidence, and reduce the bias inherent in other methods. A solid understanding of the systematic review process can be of benefit to nurses that carry out such reviews, and for those who make decisions based on them. An overview of the main steps involved in carrying out a systematic review is presented, including some of the common tools and frameworks utilised in this area. This should provide a good starting point for those that are considering embarking on such work, and to aid readers of such reviews in their understanding of the main review components, in order to appraise the quality of a review that may be used to inform subsequent clinical decision making.

Since their inception in the late 1970s, systematic reviews have gained influence in the health professions ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered to be the most credible and authoritative sources of evidence available ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ) and are regarded as the pinnacle of evidence in the various ‘hierarchies of evidence’. Reviews published in the Cochrane Library ( https://www.cochranelibrary.com) are widely considered to be the ‘gold’ standard. Since Guyatt et al (1995) presented a users' guide to medical literature for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, various hierarchies of evidence have been proposed. Figure 1 illustrates an example.

Systematic reviews can be qualitative or quantitative. One of the criticisms levelled at hierarchies such as these is that qualitative research is often positioned towards or even is at the bottom of the pyramid, thus implying that it is of little evidential value. This may be because of traditional issues concerning the quality of some qualitative work, although it is now widely recognised that both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies have a valuable part to play in answering research questions, which is reflected by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) information concerning methods for developing public health guidance. The NICE (2012) guidance highlights how both qualitative and quantitative study designs can be used to answer different research questions. In a revised version of the hierarchy-of-evidence pyramid, the systematic review is considered as the lens through which the evidence is viewed, rather than being at the top of the pyramid ( Murad et al, 2016 ).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting British Journal of Nursing and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for nurses. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

Limited access to clinical or professional articles

Unlimited access to the latest news, blogs and video content

Signing in with your registered email address

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Brooks College of Health

- Systematic Reviews

- Nursing Databases

- PICO(T) from Nutrition

- Search Strategy

What is a Systematic Review?

Types of systematic reviews, the prisma checklist and diagram, the systematic review process, structuring a systematic review article, finding the right journal for publication.

- Tools to Manage the Systematic Review Process

- Conducting a Literature Review This link opens in a new window

Call Us (904) 620-2615

Chat With Us Text Us (904) 507-4122 Email Us Schedule a Research Consultation

Visit us on social media!

PRISMA Documents

- PRISMA Checklist

- PRISMA Flow Diagram

Formulating a Research Question using PICO(T)

P=Population or problem or patient

- What are the characteristics of the patient or population? What is the condition?

I=Intervention or issue of interest

- What do you want to do with/for the patient or population?

C=Comparison

- What is the alternative to the intervention?

- What are the relevant outcomes?

A systematic review is a scientific study of all available evidence on a certain topic. It requires the most exhaustive literature search possible, not only in published literature, but also in gray literature. It may also require searches in disciplines outside the researchers primary area of study.

- Qualitative: In this type of systematic review, the results of relevant studies are summarized but not statistically combined.

- Quantitative: This type of systematic review uses statistical methods to combine the results of two or more studies.

- Meta-analysis: A meta-analysis uses statistical methods to integrate estimates of effect from relevant studies that are independent but similar and summarize them.

Anybody writing a systematic literature review should be familiar with the PRISMA statement . The PRISMA Statement is a document that consists of a 27-item checklist and a flow diagram . It is designed to guide authors on how to develop a systematic review and what to include when writing the review.

A protocol will include:

- Databases to be searched and additional sources (particularly for grey literature)

- Keywords to be used in the search strategy

- Limits applied to the search.

- Screening process

- Data to be extracted

- Summary of data to be reported

The essence of a systematic review lies in being systematic. A systematic review involves detailed scrutiny and analysis of a huge mass of literature. To ensure that your work is efficient and effective, you should follow a clear process :

1. Develop a research question

2. Define inclusion and exclusion criteria

3. Locate studies

4. Select studies

5. Assess study quality

6. Extract data

7. Analyze and present results

8. Interpret results

9. Update the review as needed

It is helpful to make notes at each stage. This will make it easier for you to write the review article.

A systematic review article follows the same structure as that of an original research article. It typically includes a title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references.

Title: The title should accurately reflect the topic under review. Typically, the words “a systematic review” are a part of the title to make the nature of the study clear.

Abstract: A systematic review usually has a structured Abstract, with a short paragraph devoted to each of the following: background, methods, results, and conclusion.

Introduction : The Introduction summarizes the topic and explains why the systematic review was conducted. There might have been gaps in the existing knowledge or a disagreement in the literature that necessitated a review. The introduction should also state the purpose and aims of the review.

Methods: The Methods section is the most crucial part of a systematic review article. The methodology followed should be explained clearly and logically. The following components should be discussed in detail:

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Identification of studies

- Study selection

- Data extraction

- Quality assessment

- Data analysis

Results: The Results section should also be explained logically. You can begin by describing the search results, and then move on to the study range and characteristics, study quality, and finally discuss the effect of the intervention on the outcome.

Discussion: The Discussion should summarize the main findings from the review and then move on to discuss the limitations of the study and the reliability of the results. Finally, the strengths and weaknesses of the review should be discussed, and implications for current practice suggested.

References: The References section of a systematic review article usually contains an extensive number of references. You have to be very careful and ensure that you do not miss out on a single one. You can consider using reference management software to help you tackle the references effectively.

Enter your manuscript's title and abstract and other requested information and these systems will identify journals that are best suited for publishing. Each resource provides journal information and additional information such as impact factors, publishing model, time to publication, etc.

These tools search the journals of the individual publisher.

- Elsevier Journal Finder

- IEEE Publication Recommender

- Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE) - PubMed

- Sage Journal Selector

- SpringerNature Journal Suggester

- Taylor & Francis Journal Suggestor

- Web of Science Manuscript Matcher You will need to create a free account to access Match.

- Wiley Journal Finder (Beta)

- A young researcher's guide to a systematic review

- How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions P. C. Sauer and S. Seuring, “How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions,” Review of managerial science, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1899–1933, 2023, doi: 10.1007/s11846-023-00668-3

- << Previous: Search Strategy

- Next: PRISMA >>

- Last Updated: Sep 2, 2024 12:14 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/nursing

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Creating Trustworthy Guidelines

- Chapter 3: Overview of the Guideline Development Process

- Chapter 4: Formulating PICO Questions

- Chapter 5: Choosing and Ranking Outcomes

- Chapter 6: Systematic Review Overview

- Chapter 7: GRADE Criteria Determining Certainty of Evidence

- Chapter 8: Domains Decreasing Certainty in the Evidence

- Chapter 9: Domains Increasing One's Certainty in the Evidence

- Chapter 10: Overall Certainty of Evidence

- Chapter 11: Communicating findings from the GRADE certainty assessment

- Chapter 12: Integrating Randomized and Non-randomized Studies in Evidence Synthesis

Related Topics:

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)

- Vaccine-Specific Recommendations

- Evidence-Based Recommendations—GRADE

Chapter 6: Systematic Review Overview

- This ACIP GRADE handbook provides guidance to the ACIP workgroups on how to use the GRADE approach for assessing the certainty of evidence.

The evidence base must be identified and retrieved systematically before the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach is used to assess the certainty of the evidence and provide support for guideline judgements. A systematic review should be used to retrieve the best available evidence related to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes (PICO) question. All guidelines should be preceded by a systematic review to ensure that recommendations and judgements are supported by an extensive body of evidence that addresses the research question. This section provides an overview of the systematic review process, external to the GRADE assessment of the certainty of evidence.

Systematic methods should be used to identify and synthesize the evidence 1 . In contrast to narrative reviews, systematic methods address a specific question and apply a rigorous scientific approach to the selection, appraisal, and synthesis of relevant studies. A systematic approach requires documentation of the search strategy used to identify all relevant published and unpublished studies and the eligibility criteria for the selection of studies. Systematic methods reduce the risk of selective citation and improve the reliability and accuracy of decisions. The Cochrane handbook provides guidance on searching for studies, including gray literature and unpublished studies ( Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies ) 1 .

6.1 Identifying the evidence

Guidelines should be based on a systematic review of the evidence 2 3 . A published systematic review can be used to inform the guideline, or a new one can be conducted. The benefits of identifying a previously conducted systematic review include reduced time and resources of conducting a review from scratch 3 . Additionally, if a Cochrane or other well-done systematic review exists on the topic of interest, the evidence is likely presented in a well-structured format and meets certain quality standards, thus providing a good evidence foundation for guidelines. As a result, systematic reviews do not need to be developed de novo if a high-quality review of the topic exists. Updating a relevant and recent high-quality review is usually less expensive and requires less time than conducting a review de novo. Databases, such as the Cochrane library, Medline (through PubMed or OVID), and EMBASE can be searched to identify existing systematic reviews which address the PICO question of interest. Additionally, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database can be searched to check for completed or on-going systematic reviews addressing the research question of interest 3 . It's important to base an evidence assessment and recommendations on a well-done systematic review to avoid any potential for bias to be introduced into the review, such as the inability to replicate methods or exclusion of relevant studies. Assessing the quality of a published systematic review can be done using the A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) instrument 3 . This instrument assesses the presence of the following characteristics in the review: relevancy to the PICO question; deviations from the protocol; study selection criteria; search strategy; data extraction process; risk of bias assessments for included studies; and appropriateness of both quantitative and qualitative synthesis 4 . A Risk of Bias of Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) assessment may also be performed 5 .

If a well-done systematic review is identified but the date of the last search is more than 6-12 months old, consider updating the search from the last date to ensure that all available evidence is captured to inform the guideline. In a well-done published systematic review, the search strategy will be provided, possibly as an online appendix or supplementary materials. Refer to the Evidence Retrieval section (6.3) for more information.

If a well-done published systematic review is not identified, then a de novo systematic review must be conducted. Once the PICO question(s) have been identified, conducting a systematic review includes the following steps:

- Protocol development

- Evidence retrieval and identification

- Risk of bias assessment

- A meta-analysis or narrative synthesis

- Assessment of the certainty of evidence using GRADE

6.2 Protocol development

There are several in-depth resources available to support authors when developing a systematic review; therefore, this and following sections will refer to higher-level points and provide information on those resources. The Cochrane Handbook serves as a fundamental reference for the development of systematic reviews and the PRISMA guidance provides detailed information on reporting requirements. To improve transparency and reduce the potential for bias to be introduced into the systematic review process, a protocol should be developed a priori to outline the methods of the planned systematic review. If the methods in the final systematic review deviate from the protocol (as is not uncommon), this must be noted in the final review with a rationale. Protocol development aims to reduce potential bias and ensure transparency in the decisions and judgements made by the review team. Protocols should document the predetermined PICO and study inclusion/exclusion criteria without the influence of the outcomes available in published primary studies 6 . The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) framework can be used to guide the development of a systematic review 7 . Details on the PRISMA-P statement and checklist are available at https://www.prisma-statement.org/protocols . 7 If the intention is to publish the systematic review in a peer-reviewed journal separately from the guideline, consider registering the systematic review using PROSPERO before beginning the systematic review process 8 .

To ensure the review is done well and meets the needs of the guideline authors, it is important to consider what type of evidence will be searched and included at the protocol stage before the evidence is retrieved 9 . While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often considered gold standards for evidence, there are many reasons why authors will choose to include nonrandomized studies (NRS) in their searches:

- To address baseline risks

- When RCTs aren't feasible, ethical or readily available

- When it is predicted that RCTs will have very serious concerns with indirectness (Refer to Table 12 for more information about Indirectness)

NRS can serve as complementary, sequential, or replacement evidence to RCTs depending on the situation 10 . Section 9 of this handbook provides detailed information about how to integrate NRS evidence. At the protocol stage it is important to consider whether or not NRS should be included.

The systematic review team will scope the available literature to develop a sense of whether or not the systematic review should be limited to RCTs alone or if a reliance on NRS may also be necessary. Once this inclusion and exclusion criteria has been established, the literature can be searched and retrieved systematically.

6.3 Evidence retrieval and identification

6.3a. searching databases.

An expert librarian or information specialist should be consulted to create a search strategy that is applied to all relevant databases to gather primary literature 1 . The following databases are widely used when conducting a systematic review: MEDLINE (via PubMed or OVID); EMBASE; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The details of each strategy as actually performed, with search terms (keywords and/or Medical Subject Headings/MESH terms) the date(s) on which the search was conducted and/or updated; and the publication dates of the literature covered, should be recorded.

In addition to searching for evidence, references from studies included for the review should also be examined to add anything relevant missed by the searches. It is also useful to examine clinical trials registries maintained by the federal government ( www.clinicaltrials.gov ) and vaccine manufacturers, and to consult subject matter experts. Ongoing studies should be recorded as well so that if the review or guideline were to be updated, these studies can be assessed for inclusion.

6.3b. Screening to identify eligible studies

The criteria for including/excluding evidence identified by the search, and the reasons for including and excluding evidence should be described (e.g., population characteristics, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study design, setting, language). Screening is typically conducted independently and in duplicate by at least two reviewers. Title and abstract screening is done first based on broader eligibility criteria and once relevant abstracts are selected, the full texts of those papers are pulled. The full-text screening is also usually conducted by two reviewers, independently and in duplicate with a more specific eligibility criteria to decide if the paper answers the PICO question or not. At both the title and abstract, and at the full-text stages, disagreements between reviewers can be resolved through discussion or involvement of a third reviewer. The goal of the screening process is to sort through the literature and select the most relevant studies for the review. To organize and conduct the systematic review, Covidence can be used to better manage each of the steps of the screening process. Other programs, such as DistillerSR or Rayyan can also be used to manage the screening process 11 12 . The PRISMA Statement ( www.prisma-statement.org ) includes guidance on reporting the methods for evidence retrieval. A PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 3) presents the systematic review search process and results.

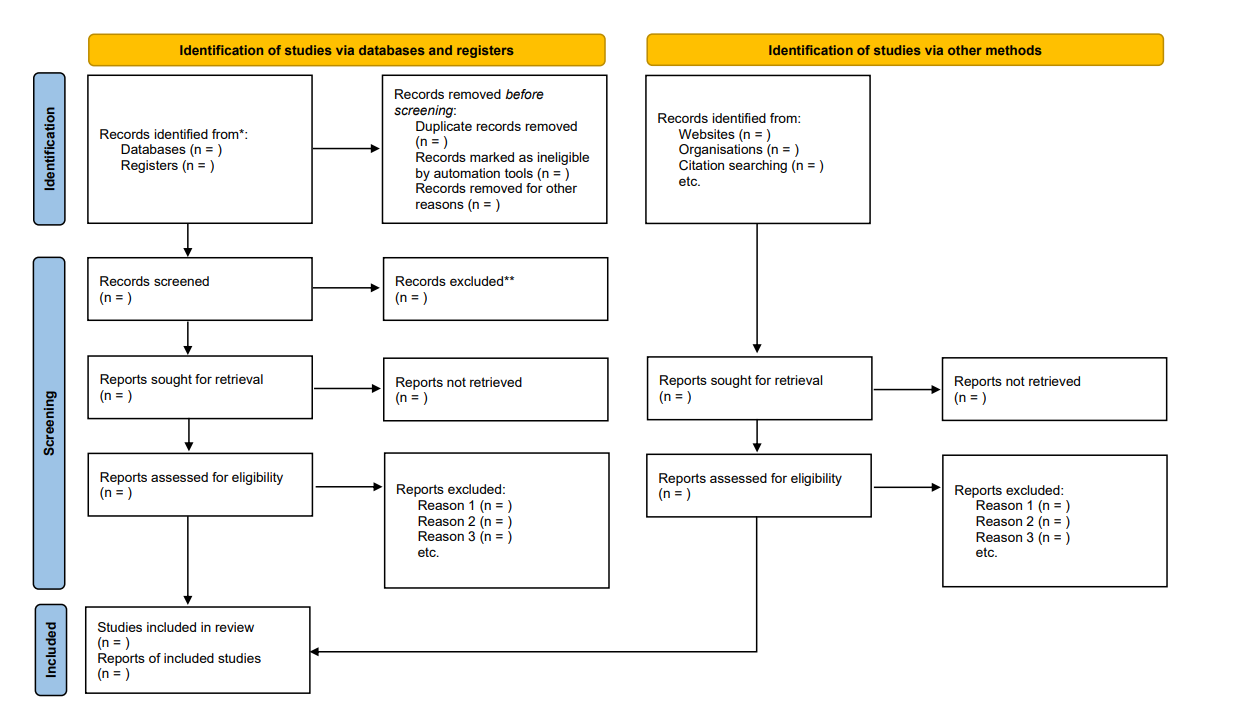

Figure 3. PRISMA flow diagram depicting the flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review evidence retrieval process, including the number of records identified, records included and excluded at each stage, and the reasons for exclusions.

References in this figure: 13

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

6.3c. Data extraction

Once included articles have been screened and selected, relevant information from the articles should be extracted systematically using a standardized and pilot-tested data extraction form. Table 3 provides an example of an ACIP data extraction form (data fields may differ by topic and scope); Microsoft Excel can be used to keep track of and extract relevant details about each study. Data extraction forms typically capture information about: 1) study details (author, publication year, title, funding source, etc.); 2) study characteristics (study design, geographical location, population, etc.); 3) study population (demographics, disease severity, etc.); 4) intervention and comparisons (e.g., type of vaccine/placebo/control, dose, number in series, etc.); 5) outcome measures. For example, for dichotomously reported outcomes, the number of people with the outcome per study arm and the total number of people in each study arm are noted. In contrast, for continuous outcomes, the total number of people in each study arm, the mean or median, as well as standard deviation or standard error are extracted. This is the information needed to conduct a quantitative synthesis. If this information is not provided in the study, reviewers may want to reach out to the authors for more information or contact a statistician about alternative approaches to quantifying data. After extracting the studies, risk of bias should be assessed using an appropriate tool described in Section 8.1 of this handbook.

Table 3. Example of a data extraction form for included studies

| Author, Year | Name of reviewer | Date completed | Study characteristics | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Other fields | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Number of participants enrolled* | Number of participants analyzed* | Loss to follow up (for each outcome) | Country | Age | Sex (% female) | Race/ Ethnicity | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Equivalence of baseline characteristics | Intervention arm Dose Duration Cointerventions | Comparison arm Dose Duration Cointerventions | Dichotomous: intervention arm n event/N, control arm n event/N | Type of study (published/ unpublished) | Funding source | Study period | Reported subgroup analyses | |||

*total and per group

6.4 Conducting the meta-analysis

After the data has been retrieved, if appropriate, it can be statistically combined to produce a pooled estimate of the relative (e.g., risk ratio, odds ratio, hazard ratio) or absolute (e.g., mean difference, standard mean difference) effect for the body of evidence of each outcome. A meta-analysis can be performed when there are at least two studies that report on the same outcome. Several software programs are available that can be used to perform a meta-analysis, including R, STATA, and Review Manager (RevMan).

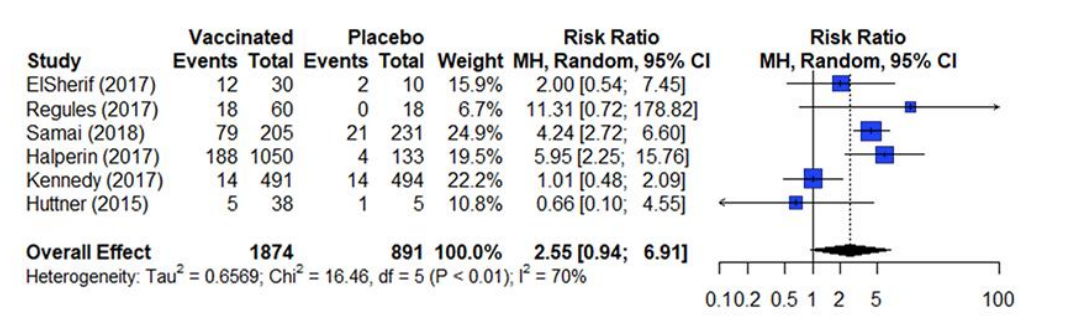

The results from a meta-analysis are presented in a forest plot as presented in figure 4. A forest plot presents the effect estimates and confidence intervals for each individual study and a pooled estimate of all the studies included in the meta-analysis 14 . The square represents the effect estimate and the horizontal line crossing the square is indicative of the confidence interval (CI; typically 95% CI). The area the square covers reflects the weight given to the study in the analysis. The summary result is presented as a diamond at the bottom.

Figure 4. Estimates of effect for RCTs included in analysis for outcome of incidence of arthralgia (0-42 days)

References in this figure: 15

The two most popular statistical methods for conducting meta-analyses are the fixed-effects model and the random-effects model 14 . These two models typically generate similar effect estimates when used in meta-analyses. However, these models are not interchangeable, and each model makes a different assumption about the data being analyzed.

A fixed-effects model assumes that there is one true effect size that can be identified across all included studies; therefore, all observed differences between studies are attributed to sampling error. The fixed effect model is used when all the studies are assumed to share a common effect size 16 . Before using the fixed-effect model in a meta-analysis, consideration should be made as to whether the results will be applied to only the included studies. Since the fixed-effect model provides the pooled effect estimate for the population in the studies included in the analysis, it should not be used if the goal is to generalize the estimate to other populations.

In contrast, a random-effects model, some variability between the true effect sizes studies is accepted. These effect sizes are assumed to follow a normal distribution. The confidence intervals generated by the random-effects model are typically wider than those generated by the fixed-effect model, as they recognize that some variability in the findings can be due to differences between the primary studies. The weights of the studies are also more similar under the random-effects model. When variations in, for example, the participants or methods across different included studies is suspected, it is suggested to use a random-effects model. This is because the studies are weighed more evenly than the fixed effect model. The majority of analyses will meet the criteria to use a random effects mode. One caveat about the selection of models: when the number of studies included in the analysis is few (<3), the random-effects model will produce an estimate of variance with poor precision. In this situation, a fixed effect model will be a more appropriate way to conduct the meta-analysis 17 .

- Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, et al. Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 63 (updated February 2022). Cochrane; 2022. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines BoHCS, Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011.

- World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd ed. 2014: World Health Organization. 167.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017/09/21/ 2017:j4008. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4008

- Bristol Uo. ROBIS tool.

- Lasserson T, Thomas J, Higgins J. Chapter 1: Starting a review. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 63. 2022. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. Jan 1 2015;4:1. doi:10.1186/2046- 4053-4-1

- PROSPERO. York.ac.uk. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/

- Cuello-Garcia CA, Santesso N, Morgan RL, et al. GRADE guidance 24 optimizing the integration of randomized and non-randomized studies of interventions in evidence syntheses and health guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022/02// 2022;142:200-208. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.11.026

- Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Reeves BC, et al. Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Research Synthesis Methods. 2013 2013;4(1):49-62. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1078

- DistillerSR | Systematic Review and Literature Review Software. DistillerSR.

- Rayyan – Intelligent Systematic Review. https://www.rayyan.ai/

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

- Deeks J, Higgins J, Altman D. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of v.04_2024 20 Interventions version 63 (updated February 2022). Cochrane; 2022. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- Choi MJ, Cossaboom CM, Whitesell AN, et al. Use of ebola vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2021;70(1):1.

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2021.

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods. 2010;1:97-111. doi:DOI: 10.1002/jrsm.12

ACIP GRADE Handbook

This handbook provides guidance to the ACIP workgroups on how to use the GRADE approach for assessing the certainty of evidence.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 19, Issue 1

- Reviewing the literature

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK