- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Zora Neale Hurston

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Florida Department of State - Division of Cultural Affairs - Zora Neale Hurston

- Florida Center for Instructional Technology - Famous Floridians: Zora Neale Hurston

- Official Site of Zora Neale Hurston

- The University of Tennessee Knoxville - TRACE - Zora Neale Hurston: Scientist, Folklorist, Storyteller

- New-York Historical Society - Women & the American Story - Life Story: Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960)

- Famous Scientists - Zora Neale Hurston

- Encyclopedia of Alabama - Biography of Zora Neale Hurston

- Zora Neale Hurston - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

When was Zora Neale Hurston born?

Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1891. She claimed to have been born in 1901 in order to receive a free high-school education even though she was already in her mid-20s.

Where did Zora Neale Hurston grow up?

Zora Neale Hurston grew up in Eatonville, Florida, the first incorporated all-Black town in the United States.

What were Zora Neale Hurston’s accomplishments?

Zora Neale Hurston’s ethnographic research made her a pioneer writer of “folk fiction” about African Americans in the South. She was a prominent writer in the Harlem Renaissance . Their Eyes Were Watching God , published in 1937, is her most celebrated novel.

Where did Zora Neale Hurston go to school?

Zora Neale Hurston attended Howard University from 1921 to 1924 before winning a scholarship to Barnard College to study anthropology under Franz Boas . After graduating from Barnard, she pursued graduate studies in anthropology at Columbia University .

Recent News

Zora Neale Hurston (born January 7, 1891, Notasulga, Alabama , U.S.—died January 28, 1960, Fort Pierce , Florida) was an American folklorist and writer associated with the Harlem Renaissance who celebrated African American culture of the rural South.

Although Hurston claimed to be born in 1901 in Eatonville, Florida , she was, in fact, 10 years older and had moved with her family to Eatonville only as a small child. There, in the first incorporated all-Black town in the country, she attended school until age 13. After the death of her mother (1904), Hurston’s home life became increasingly difficult, and at 16 she joined a traveling theatrical company, ending up in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance .

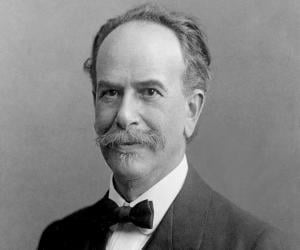

She attended Howard University from 1921 to 1924 and in 1925 won a scholarship to Barnard College , where she studied anthropology under Franz Boas . She graduated from Barnard in 1928 and for two years pursued graduate studies in anthropology at Columbia University . She also conducted field studies in folklore among African Americans in the South. Her trips were funded by folklorist Charlotte Mason , who was a patron to both Hurston and Langston Hughes . For a short time Hurston was an amanuensis to novelist Fannie Hurst .

(Read W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 Britannica essay on African American literature.)

In 1930 Hurston collaborated with Hughes on a play (never finished) titled Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life in Three Acts (published posthumously 1991). In 1934 she published her first novel , Jonah’s Gourd Vine , which was well received by critics for its portrayal of African American life uncluttered by stock figures or sentimentality. Mules and Men , a study of folkways among the African American population of Florida, followed in 1935. Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), a novel, Tell My Horse (1938), a blend of travel writing and anthropology based on her investigations of voodoo ( Vodou ) in Haiti , and Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939), a novel, firmly established her as a major author.

For a number of years Hurston was on the faculty of North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) in Durham . She also was on the staff of the Library of Congress . Dust Tracks on a Road (1942), an autobiography , is highly regarded. Her last book, Seraph on the Suwanee , a novel, appeared in 1948.

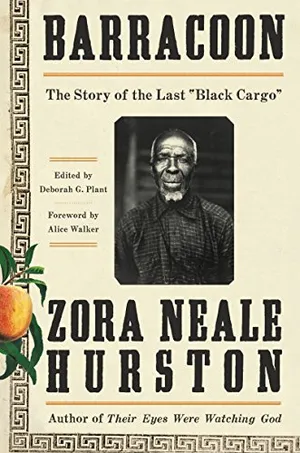

Despite her early promise, by the time of her death in 1960 Hurston was little remembered by the general reading public, but there was a resurgence of interest in her work in the late 20th century. In addition to Mule Bone , several other collections of her work were published posthumously; these include Spunk: The Selected Stories (1985), The Complete Stories (1995), and Every Tongue Got to Confess (2001), a collection of folktales from the South. In 1995 the Library of America published a two-volume set of Hurston’s work in its series. In addition, Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” was released in 2018. Although completed in 1931, this nonfiction work was originally rejected by publishers because of its use of vernacular . It tells the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was believed to be the last survivor of the final ship that brought enslaved Africans to the United States . Ibram X. Kendi adapted several folktales collected by Hurston as books for children in the 2020s.

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Hurston was a world-renowned writer and anthropologist. Hurston’s novels, short stories, and plays often depicted African American life in the South. Her work in anthropology examined black folklore. Hurston influenced many writers, forever cementing her place in history as one of the foremost female writers of the 20 th century.

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama on January 7, 1891. Both her parents had been enslaved. At a young age, her family relocated to Eatonville, Florida where they flourished. Eventually, her father became one of the town’s first mayors. In 1917, Hurston enrolled at Morgan College, where she completed her high school studies. She then attended Howard University and earned an associate’s degree. Hurston was an active student and participated in student government. She also co-founded the school’s renowned newspaper, The Hilltop . In 1925, Hurston received a scholarship to Barnard College and graduated three years later with a BA in anthropology. During her time as a student in New York City, Hurston befriended other writers such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Together, the group of writers joined the black cultural renaissance which was taking place in Harlem.

Throughout her life, Hurston, dedicated herself to promoting and studying black culture. She traveled to both Haiti and Jamaica to study the religions of the African diaspora. Her findings were also included in several newspapers throughout the United States. Hurston often incorporated her research into her fictional writing. As an author Hurston, started publishing short stories as early as 1920. Unfortunately, her work was ignored by the mainstream literary audience for years. However, she gained a following among African Americans. In 1935, she published Mules and Men . She later, collaborated with Langston Hughes to create the play, Mule Bone . She published three books between 1934 and 1939. One of her most popular works was Their Eyes were Watching God . The fictional story chronicled the tumultuous life of Janie Crawford. Hurston broke literary norms by focusing her work on the experience of a black woman.

Hurston was not only a writer, she also dedicated her life to educating others about the arts. In 1934, she established a school of dramatic arts at Bethune-Cookman College. Five years later she worked as a drama teacher at the North Carolina College for Negroes at Durham. Although Hurston eventually received praise for her works, she was often underpaid. Therefore, she remained in debt and poverty. After years of writing, Hurston had to enter the St. Lucie County Welfare Home as she was unable to take care of herself. Hurston died of heart disease on January 28, 1960. At first, her remains were placed in an unmarked grave. In 1972, author Alice Walker located her grave and created a marker. Although, Hurston’s work was not widely known during her life, in death she ranks among the best writers of the 20 th century. Her work continues to influences writers throughout the world.

- Hemenway, Robert. Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography . Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Novels and Stories . Ed. Cheryl Wall. New York: Library of America, 1995.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Dust Tracks on a Road . New York: Harper Collins, Reissue 2010.

- Zora Neale Hurston: Digital Archive

- PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA – Norwood, Arlisha. "Zora Hurston." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2017. Date accessed.

Chicago- Norwood, Arlisha. "Zora Hurston." National Women's History Museum. 2017. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/zora-hurston.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, faith ringgold and her fabulous quilts, educational equality & title ix:.

- Advisory Board

Hurston's Life

- Communities

- Contemporary Eatonville

- Cultural Preservation

- Archive Collections

- Full Text Images

- Primary Bibliography

- Published Genres

- Edited Collections

- Contemporary Reviews

- Secondary Bibliography

- Dissertations

- Plot Summaries

- Syllabi, Lesson Plans, et al

- Other Academic Websites

- Common Reader

"I was born in a Negro town. I do not mean by that the black back–side of an average town. Eatonville, Florida, is, and was at the time of my birth, a pure Negro town–charter, mayor, council, town marshal town." Zora Neale Hurston declares in her memoir, Dust Tracks on a Road , that she is a child of the first incorporated African–American community, incorporated by 27 African–American males on August 18, 1887. Her father, John Cornelius Hurston, was the minister of one of the two churches in town and the mayor for three terms. In her small town she led a privileged position as the mayor's daughter and felt that she had a special destiny: "My soul was with the gods and my body in the village."

In reality, Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama, on January 15, 1891. She often changed the date of her birth, to 1901, 1903, or 1910–perhaps, to be thought a child of the new century or to gain an advantage in appearing younger while being older. Hurston obscured the basic fact of her existence–that her father was from "over de creek" in Notasulga, a share–cropping former slave who married up. Hurston, instead, was like Athena, born of her father's head, a child of imagination, who insisted on creating her own, unique identity. Later in life, Hurston would become an anthropologist and scientifically study mythology and folk tales, but early on in her life she must have had a strong sense of her own mythologizing tendencies and believed that a Story about her genesis in the first all–black town suited her purposes as a special individual. Her biographer, Robert Hemenway, calls her "a woman of fierce independence," who "was a complex woman with a high tolerance of contradiction." In African–American terms, she was skilled in the art of "masking," disguising her inner life for her own purposes.

Perhaps, she began her masking career on September 18, 1904, the day her mother died. At Lucy Hurston's funeral, her family "assembled together for the last time on earth." Two weeks later, thirteen–year–old Zora Neale Hurston was forced to pack her bags and leave the only home she had ever known. "With a grief that was more than common," she began a life of wandering from one family member to another, never sinking roots for long in the Florida soil she loved. Her childhood had been idyllic in Eatonville, where the family moved the year or so after Hurston was born. Florida was the new South, in contrast to the Old Jim Crow South of Alabama. In her memoir, Dust Tracks on a Road , Hurston writes of her love of nature, of books and learning, and of Story –telling. She recalls the Florida landscape: "I was only happy in the woods, and when the ecstatic Florida springtime came strolling from the sea, trance–glorifying the world with its aura." She also reminisces lovingly of her home as "the center of the world." Yet, the bigger world outside always beckoned to her: "It grew upon me that I ought to walk out to the horizon and see what the end of the world was like."

After her mother's death, Hurston was not allowed to explore the world on her own terms; instead, she was in a struggle for her very existence. Hurston calls the years, from 1904–14, her "haunted years," because her life was so dismal. Unfortunately, not many records exist from this period of her life, except for the fact that she moved to Jacksonville to live with her sister, Sarah, and brother, Robert. In Jacksonville, she learned that she was "a little colored girl." She was not able to get much education, probably, because she had to work, most likely as a maid; and her father sometimes did not pay for her tuition.

This desperate period ended when Hurston's brother, Robert, now a practicing physician, invited her to care for his children in Nashville, Tennessee. When he did not encourage her to attend high school, she ran off to become the personal maid to Miss M., a singer in a Gilbert and Sullivan troupe. Little is known about Hurston's first direct contact with the theater, but drama would become the great passion of her life. Even though Hurston was to gain her fame as a novelist, she would have loved to have made her mark as a dramatist. Her connection to the troupe ended in 1916, in Baltimore after Hurston had an appendicitis attack. Fortunately, her sister, Sarah, was living in Baltimore and Hurston stayed on with her.

This turn of events changed Hurston's life. She was finally able to attend school and enrolled at Morgan Academy. After graduation in 1918, she entered Howard University. At long last, Hurston was in a position finally to actualize her potential and associate with the brilliant minds of her generation. Lorenzo Dow Turner, who wrote Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect , taught her African words and Montgomery Gregory directed her as a member of the Howard Players. His desire to establish a National Negro Theatre would become Hurston's lifelong dream. Hurston also joined a literary club, sponsored by Alain Locke, who encouraged her to publish in Howard University journals. She met other writers known as the "New Negroes" in Georgia Douglas Johnson's literary salon. These writers–Bruce Nugent, Jean Toomer, Alice Dunbar–Nelson, and Jessie Fauset, among others–would in the next decade become part of the core group of the Harlem Renaissance.

Hurston's literary career began when she submitted her work to journals and it was accepted. In 1924, she sent her second short Story , "Drenched in Light," to Charles S. Johnson, the editor of Opportunity , a publication of the Urban League. Hurston's Story was not only published but received second prize in the annual Opportunity literary contest. The subject of "Drenched in Light" is Eatonville, which is, according to Hemenway, "her unique subject, and she was encouraged to make it the source of her art." Johnson urged her to move to New York City and by 1925, she found herself living in Harlem.

At the next Opportunity awards banquet in 1925, Hurston not only won more prizes for her work, but met Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Carl Van Vechten, Fannie Hurst, and Annie Nathan Meyer–all of whom would befriend and support her in the coming decade. Meyer, a founder of Barnard College, would assist Hurston into getting accepted into the college and awarded a scholarship. Barnard provided another turning point for Hurston. She began to study anthropology with Franz Boas, the father of modern anthropology, who believed in the distinctive culture of African Americans. Boas urged Hurston to do fieldwork in her hometown, in order to preserve her heritage that was slipping away.

In the 1920's, Hurston's literary and scientific interests in anthropology were merging. She used the knowledge of her native community and its people to deepen and complicate her stories. She aspired to be "the authority on Afro–American folklore," according to Hemenway, with her main interest in the "Negro farthest down." But, finances were always a never–ending problem. In 1927, Hurston accepted the aid of Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy white New York woman, who was willing to fund Hurston's folklore expeditions as long as Mason retained control over how the material would be used. This devil's bargain would eventually cause Hurston to break her academic ties with her respected professors–although she did graduate from Barnard–and, on a psychic level, wear her down because of Mason's controlling nature. On the other hand, with the freedom from academic restraint and method this arrangement afforded her, Hurston was able to follow her own unique interests. She became intrigued by hoodoo and traveled to New Orleans to see how it was practiced and study the life of the priestess, Marie Leveau. Hoodoo appealed to Hurston, because women were allowed to play a prominent role in its rituals. Perhaps, she simply became her father's daughter, who was seeking an outlet for her spiritual side.

Around the same time that her relationship with Mason was at a breaking point (Mason eventually severed her contract with Hurston on March 31, 1931) and the country was heading towards the Great Depression, Hurston, desperate for an income, felt that the best vehicle for her work was the theater and the best type of production was a folk musical based on her memories of Eatonville. She was thrilled when her play, The Great Day , played for one night at the John Golden Theatre on January 27, 1931. Unfortunately, the play was forced to close, because Hurston had no producers waiting in the wings to keep the production going. Instead, she took her dream south, to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, and staged two productions, From Sun to Sun and All De Live Long Day , in 1933 and 1934. Many people from her hometown of Eatonville acted in these plays; thus, her dream of a folk theater was partially realized.

Hurston's association with Rollins College was significant for another reason. Robert Wunsch, who was the theater director who assisted her in the staging of her plays, after reading one of her short stories, "The Gilded Two Bits"; sent it to Story magazine, which published it in 1933. The Story was read by publisher Bertram Lippincott, who wrote to Hurston asking if she had a novel that she could submit to him. Hurston replied affirmatively–and then on July 1, 1933, she moved to Sanford, Florida, to write one. She wrote Jonah's Gourd Vine by September 6 and was evicted from her apartment on the same day that she received an acceptance letter for her novel. Jonah's Gourd Vine was published in May 1934. The next year Lippincott published Hurston's book of folk tales, Mules and Men .

Hurston now entered her prime creative period in which she pursued fiction, drama, and anthropology simultaneously. She had her Opportunity when she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in March 1936 and was able to travel to Jamaica and Haiti. While she was in Haiti she began writing Their Eyes Were Watching God , embodying all of her passion for her lover, Percy Punter, into the portrayal of Tea Cake. She completed the book in seven weeks and Their Eyes Were Watching God was published on September 18, 1937. She also continued her anthropological studies in voodoo in Haiti and published Tell My Horse in 1938.

After this peak period in her life, Hurston struggled to survive. She began working for the Works Progress Administration on April 25, 1938, and contributed folklore and interviews with former slaves to The Florida Negro, which was not published at the time. This job lasted until 1939, when the WPA was dismantled. Hurston had once again to search for a vehicle in which to express herself. Her dramatic efforts had led nowhere, her ideas for new novels were rejected, and she had no more folklore to record. According to Hemenway, "In a sense she was written out." Bertram Lippincott suggested she write her autobiography. When Dust Tracks on a Road was published in 1942, Hurston experienced a revival: she won the $1,000 Anisfield–Wolf Award and was featured on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post . A few years later, Hurston's writing career received another boost when Maxwell Perkins, the legendary Scribner's editor of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe; agreed to work with Hurston. Unfortunately, he died two months later and Hurston was deprived of his masterful guidance. Hurston did go on to publish in 1948 her last novel with Scribner's, Seraph on the Suwanee , a departure from her usual cast of Eatonville characters. For this novel, her heroes and heroines are white characters.

Besides her difficulties in getting her work published, on September 13, 1948, a mother accused Hurston of molesting her ten–year–old son, who was mentally retarded. Although Hurston's passport proved that she was in Honduras at the time, she was devastated when the Story was splashed across the African–American tabloids. She sunk into a period of depression, even though Scribner's stood beside her and hired lawyers to defend her. She was acquitted of all charges when the boy confessed that he had falsely accused Hurston of the act.

During the next decade, Hurston made her living by selling occasional articles to popular magazines and working as a maid. She became obsessed in telling the Story of Herod the Great and was deeply discouraged when Scribner's rejected the manuscript in 1955. Money became a gnawing problem, as well as Hurston's health. She was evicted from her Eau Gallie home in 1956. In the next two years, she was hired as a librarian at Patrick Air Force Base in Cocoa Beach, but fired 11 months later. When she was fired from a substitute teaching position at Lincoln Academy in Ft. Pierce, she couldn't pay her rent. In 1958, Hurston suffered a series of strokes and entered the St. Lucie County Welfare Home. She died on January 28, 1960. Patrick Duval rescued her manuscripts from destruction when her possessions were being burned after her death. She was buried in an unmarked grave at the Garden of Heavenly Rest in Ft. Pierce. Thirteen years later, Alice Walker located her grave and placed a grave stone on it, citing as a reason: "A people do not forget their geniuses . . ."

~ Anna Lillios

Hemenway, Robert. Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography . Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Novels and Stories . Ed. Cheryl Wall. New York: Library of America, 1995.

Kaplan, Carla, editor. Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters . New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Otey, Frank M. Eatonville, Florida: A Brief Hi Story of One of America's First Freedmen's Towns . Winter Park, FL: Four–G Publishers, 1989.

Funding and support provided by the UCF Center for Humanities and Digital Research and the Department of English .

© Copyright 2024 University of Central Florida. All rights reserved.

Site Credits

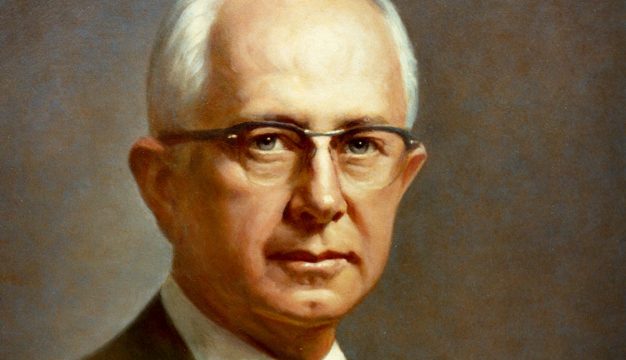

Sidebar painting by Saul Audes, courtesy of the Bryant Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Central Florida Libraries, Orlando.

Hurston Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, reproduced with permission of the Van Vechten Trust.

Web Design & Development by Paul Czech

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Zora neale hurston (1891-1960).

Zora Neale Hurston, known for her audacious spirit and sharp wit, was a talented and prolific writer and a skilled anthropologist from the Harlem (New York) Renaissance to the Civil Rights Era. Born on January 7, 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, she grew up in the all-black town of Eatonville, Florida. Her idyllic life in this provincial rural town was shattered with the death of her mother when Hurston was 14 and her father’s unexpected remarriage. In a few years Hurston was on her own working as a maid. She settled in Baltimore, Maryland and completed her education at Morgan Academy and Howard University .

Hurston’s talent was readily apparent to her professors including Alain Locke and Montgomery Gregory. With Locke’s and Gregory’s support her short story “John Redding Goes to Sea” was published in Howard’s literary magazine Stylus in 1921. Locke recommended Hurston’s work to Charles S. Johnson , who in 1924 published her second short story, “Drenched in Light” in Opportunity magazine.

In September 1925 Hurston entered Barnard College, where she studied anthropology with the distinguished scholar Franz Boas. She received her B.A. in 1928. Throughout this period, however, Hurston continued to write. In June 1925 her short story “Spunk” was published in Opportunity . In collaboration with Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman , Hurston in the late 1920s edited the short-lived magazine Fire! Collaborating with Langston Hughes, in 1930 she wrote her first play titled Mule Bone , a comedy about African American rural folk life. Four years later Hurston published her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine , loosely based on the life of her father, a rural minister. In 1935 she authored Mules and Men , a volume of anthropological folklore.

Hurston’s most famous work, Their Eyes Were Watching God , was published in 1937 followed by Moses, Man of the Mountain in 1939, and Seraph on the Suwanee , the least successful of her works, in 1948. Her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road , appeared in 1942.

Hurston’s final years were marked by poverty, difficulty with writing, and estrangement from her family. Though ill, she remained independent until the end. Zora Neale Hurston died in obscurity and was buried in an unmarked grave in January 1960.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Tiffany Ruby Patterson, Zora Neale Hurston and a History of Southern Life (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005).

- Agriculture

- Arts & Literature

- Business & Industry

- Geography & Environment

- Government & Politics

- Science & Technology

- Sports & Recreation

- Organizations

- Collections

- Quick Facts

Zora Neale Hurston

The controversy surrounding Hurston begins with the place of her birth. Notasulga , located in both Macon and Lee Counties, and Eatonville, Florida, both vie for the honor, but Notasulga, in east-central Alabama, is currently accepted by most scholars. She was born on January 7, 1891, to John Hurston and Lucy Potts Hurston, who was from a landowning family and had taught school before marrying. The Potts family, according to Hurston in her autobiography, Dirt Tracks on a Road, did not approve of the marriage because the groom's prospects were poor, but John and Lucy wed, farmed , and started their own family. Zora was the fifth child, and when she was a toddler, they moved to the all-black town of Eatonville. There, John became a carpenter and a Baptist preacher, and he was elected mayor. Lucy Hurston died in 1904, and Hurston was sent to a boarding school in Jacksonville, Florida, where she was a successful and enthusiastic student. John remarried, and because Zora and her new stepmother disliked each other, Hurston lived with several relatives. She supported herself as a domestic before going to live with a brother in Baltimore, graduating from the city's Morgan Academy in June 1918. Disappointed by her brother's unwillingness to allow her to continue her education, Hurston found work with a traveling entertainment company. She earned $10 a week performing chores for her employer (whom she later wrote about in Dust Tracks on a Road as Miss M) and other members of the company. They loaned Hurston books, exposed her to classical music, and included her in discussions. When Miss M decided to leave the stage and marry, Hurston returned to Baltimore.

Hurston's dream was that their efforts would preserve and promote the traditional dialects and cultural heritage of rural southern black people; although she and other intellectuals envisioned more and better opportunities for African Americans, Hurston differed in that she resisted the idea of trading black culture for economic and social equality. Langston Hughes accused her of catering to white audiences and of allowing white patronage to affect her work; her defense against such accusations was that she chose to create characters memorable for their unapologetic celebration of black heritage. Her stance was one of affirmation. Fearful, perhaps, that integration would threaten black cultural traditions, Hurston opposed desegregation. This position was unpopular and misunderstood by those seeking social change. Aware of racism, racially motivated violence, and the degradation of Jim Crow laws, Hurston nonetheless did not launch a frontal attack. She understood the problems experienced by African Americans and women in the first half of the twentieth century, but she perceived that portrayals of them as helpless victims would perpetuate a sense of inferiority. Using Eatonville porch stories and material from collecting excursions, she recorded vibrant black life and the will to survive in a hostile environment, and she dealt with bitterness and resentment about injustice in subtle ways. Her characters are proud, independent, confident, and resourceful; they represent a healthy culture that Hurston did not want subsumed or assimilated. She championed diversity. Hers were ordinary people too busy living to spend much time feeling oppressed or demanding pity or sympathy from a dominant culture whose values were questionable.

Hurston graduated from Barnard in 1928 and embarked on a successful career as a playwright. She wrote and directed musical, dance, and dramatic productions that employed black talent and emphasized African American culture and contributions to U.S. history and society and were performed in New York, Florida, and Chicago. In 1934, she published her first novel, Jonah's Gourd Vine . That same year, the Rosenwald Foundation offered her a fellowship to enter the doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University; she accepted the fellowship but never completed the degree. Instead, using field notes that she had collected in New Orleans and Florida in 1927, she wrote Mules and Men, which she published in 1935. On the strength of that and her other accomplishments, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study West Indian folklife in Haiti. While there, she wrote her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, which was published in 1937. She published Tell My Horse, based on her experiences in Haiti, in 1938, and in 1941 wrote an autobiography entitled Dust Tracks on a Road .

None of Hurston's novels met with absolute acclaim. Some critics praised her honesty, accepting the simplicity and humor in her writing as evidence of black contentment; others deplored her reluctance to address racial conflict and bitterness. Publishers were partly to blame because they edited out passages and requested that she delete some controversial social and political observations. Even Their Eyes Were Watching God, generally recognized as Hurston's best work, was not considered serious enough by some reviewers. There was universal agreement, however, that she was gifted at capturing and retelling the stories of common people. Her last book, Seraph on the Suwanee, was published in 1948, but it received poor reviews.

During the last 10 years of her life, Hurston continued to write essays that reflected her complex views on integration. In them, she advocated segregation as a means of preserving African American cultural traditions. Hurston's final years were plagued by financial worries and declining health. With little work coming her way after the false molestation charges, she worked as a maid in Rivo Alto, Florida, and struggled to find work throughout the 1950s. In 1959, Hurston was admitted to a nursing home in Fort Pierce after she suffered a stroke. She died there of a heart attack on January 28, 1960, and was buried in an unmarked grave. Author Alice Walker, who counted Hurston as a primary influence in her own writing, revived interest in Hurston when she searched out Hurston's grave, provided a headstone for it, and published an article entitled "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston" in Ms. magazine in 1975.

Works by Zora Neale Hurston

Jonah's Gourd Vine (1934)

Mules and Men (1935)

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (1938)

Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939)

Dust Tracks on a Road (1942)

Seraph on the Suwanee (1948)

The Sanctified Church: The Folklore Writings of Zora Neale Hurston (1981)

Spunk: The Selected Stories (1985)

Further Reading

- Bloom, Harold, ed. Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Chelsea House, 1986.

- Green, Sharony. The Chase and Ruins: Zora Neale Hurston in Honduras. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023.

- Hemenway, Robert E. Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

- Kaplan, Carla. Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters. New York: Anchor Books, 2003.

External Links

- The Zora Neale Hurston Plays at the Library of Congress

- Zora Neale Hurston Digital Archive

- This Goodly Land: Alabama's Literary Landscape

- Zora Neale Hurston Official Website

Cheryl Dowe Carpenter Alabama A&M University

Last Updated

- Share on Facebook

- Send via Email

Related Articles

Mercedes-Benz U.S. International Inc.

Located in Vance, Tuscaloosa County, Mercedes-Benz U.S. International Inc. (MBUSI) was the first-ever automobile manufacturing facility established in Alabama and the firm's first in the United States. MBUSI employs about 4,000 individuals, has created thousands of additional jobs in associated industries, and has contributed more than $1.5 billion to the…

Pecan Production in Alabama

Pecan nuts are produced on trees that are native to the United States. They have been grown commercially in Alabama since the early twentieth century. Alabama is one of 15 states that produces pecans commercially and has approximately 9,000 acres in 30 counties planted with pecan orchards, with the highest…

Buford Boone

Though not a native Alabamian, James Buford Boone Sr. (1909-1983) nonetheless became one of the state's leading voices for moderation during the tumultuous modern civil rights era. As publisher of the Tuscaloosa News , he wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial chastising the University of Alabama (UA) and local residents for their…

Joshua Lafayette Mitchell

Joshua Lafayette Mitchell (1866-1906) was a noted builder of wooden railway trestles in Alabama and Georgia in the early twentieth century. He is best known in Alabama for building what was at the time the highest wooden railroad trestle in the United States for the L&N Railroad Company in Jefferson…

Share this Article

Hurston, zora neale.

Zora Neale Hurston

Author of Their Eyes Were Watching God

Fotosearch / Archive Photos / Getty Images

- Important Figures

- History Of Feminism

- Women's Suffrage

- Women & War

- Laws & Womens Rights

- Feminist Texts

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- B.A., Mundelein College

- M.Div., Meadville/Lombard Theological School

Zora Neale Hurston is known as an anthropologist, folklorist, and writer. She is known for such books as Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama, probably in 1891. She usually gave 1901 as her birth year, but also gave 1898 and 1903. Census records suggest 1891 is the more accurate date.

Childhood in Florida

Zora Neale Hurston moved with her family to Eatonville, Florida, while she was very young. She grew up in Eatonville, in the first incorporated all-Black town in the United States. Her mother was Lucy Ann Potts Hurston, who had taught school before marrying, and after marriage, had eight children with her husband, the Reverend John Hurston, a Baptist minister, who also served three times as mayor of Eatonville.

Lucy Hurston died when Zora was about thirteen (again, her varied birth dates make this somewhat uncertain). Her father remarried, and the siblings were separated, moving in with different relatives.

Hurston went to Baltimore, Maryland, to attend Morgan Academy (now a university). After graduation, she attended Howard University while working as a manicurist, and she also began to write, publishing a story in the magazine of the school's literary society. In 1925 she went to New York City, drawn by the circle of creative Black artists (now known as the Harlem Renaissance), and she began writing fiction.

Annie Nathan Meyer, the founder of Barnard College , found a scholarship for Zora Neale Hurston. Hurston began her study of anthropology at Barnard under Franz Boaz, studying also with Ruth Benedict and Gladys Reichard. With the help of Boaz and Elsie Clews Parsons, Hurston was able to win a six-month grant she used to collect African American folklore.

While studying at Barnard College (one of the Seven Sisters Colleges) , Hurston also worked as a secretary (an amanuensis) for Fannie Hurst, a novelist. (Hurst, a Jewish woman, later—in 1933—wrote Imitation of Life , about a Black woman passing as white. Claudette Colbert starred in the 1934 film version of the story. "Passing" was a theme of many of the Harlem Renaissance women writers.)

After college, when Hurston began working as an ethnologist, she combined fiction and her knowledge of culture. Mrs. Rufus Osgood Mason financially supported Hurston's ethnology work on the condition that Hurston did not publish anything. It was only after Hurston cut herself off from Mrs. Mason's financial patronage that she began publishing her poetry and fiction.

Zora Neale Hurston's best-known work was published in 1937: Their Eyes Were Watching God , a novel which was controversial because it didn't fit easily into stereotypes of Black stories. She was criticized within the Black community for taking funds from whites to support her writing; she wrote about themes "too Black" to appeal to many whites.

Hurston's popularity waned. Her last book was published in 1948. She worked for a time on the faculty of North Carolina College for Negroes in Durham, she wrote for Warner Brothers motion pictures, and for some time worked on staff at the Library of Congress.

In 1948, she was accused of molesting a 10-year-old boy. She was arrested and charged, but not convicted, as the evidence did not support the charge.

In 1954, Hurston was critical of the Supreme Court's order to desegregate schools in Brown v. Board of Education . She predicted that the loss of a separate school system would mean many Black teachers would lose their jobs, and children would lose the support of Black teachers.

Eventually, Hurston went back to Florida. On January 28, 1960, after several strokes, she died at the St. Lucie County Welfare Home, her work nearly forgotten and thus lost to most readers. She never married and had no children. She was buried in Fort Pierce, Florida, in an unmarked grave.

In the 1970s, during the " second wave " of feminism, Alice Walker helped revive interest in Zora Neale Hurston's writings, bringing them back to public attention. Today Hurston's novels and poetry are studied in literature classes and in women's studies and Black studies courses. They have become again popular with the general reading public.

More About Hurston:

- Howard, Lillie P. Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston: The Common Bond , Contributions in Afro-American and African Series #163 (1993)

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Pamela Bordelon, editor. Go Gator and Muddy the Water: Writings by Zora Neale Hurston from the Federal Writers Project (1999)

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Alice Walker, editor. I Love Myself When I Am Laughing...and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader (1979)

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God . (2000 edition)

- Harlem Renaissance Women

- Biography of Alice Walker, Pulitzer Prize Winning Writer

- 35 Zora Neale Hurston Quotes

- 100 Most Important Women in World History

- Top 100 Women of History

- Women of the Harlem Renaissance

- 27 Black American Women Writers You Should Know

- Quotes From Women in Black History

- Women Poets in History

- Best-Loved American Women Poets

- Mary Wollstonecraft: A Life

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

- Biography of Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Famous and Powerful Women of the Decade - 2000-2009

- Unitarian and Universalist Women

- Outstanding Women Writers of the 20th Century

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Hurston, zora neale.

- Susan Butterworth

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.626

- Published online: 26 July 2017

The oral tradition of southern black folklore was an art and a skill handed down from Africa, preserved through slavery, and still thriving in the early years of the twentieth century, when Zora Neale Hurston came of age. The tradition was preserved through generations of rural southern culture and began to decline when the black workers left the agricultural South for the cities of the North. Zora Neale Hurston was singularly placed to record this material as folklore and to transform it to art through fiction. Zora Hurston's place and date of birth are obscured by the selective secrecy and mythology that veiled her personal life. Hurston wanted her contemporaries to believe that she was born 7 January 1901 in Eatonville, Florida. Birth records revealed years later, however, that she was born in 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama.

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 August 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

Character limit 500 /500

10 Fascinating Facts About Zora Neale Hurston

American writer and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston ’s literary legacy is a class apart. Initially celebrated, later vilified, and posthumously canonized as “ the patron saint of Black women writers ,” her work has inspired the likes of Toni Morrison and Bernardine Evaristo. Here are some things you might not have known about the author, who was born on January 7, 1891.

1. Zora Neale Hurston’s most recent book was published 62 years after her death.

A collection of short stories Zora Neale Hurston wrote between 1927 and 1937 was published in 2020 under the title, Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick: Stories from the Harlem Renaissance . In 2022, another essay collection — You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays —was reissued by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and fellow scholar, Genevieve West. In a review of the 2022 work, The New York Times wrote that it “adds immeasurably to our understanding of Hurston, who was a tireless crusader in all her writing, and ahead of her time.”

While many authors have had their work published posthumously, Hurston’s case is remarkable because her work and legacy were all but lost to the world—until Toni Morrison and The Color Purple author Alice Walker helped bring her work back into the spotlight.

2. Zora Neale Hurston’s out of print work was revived more than a decade after her death.

By the time of Hurston’s death on January 28, 1960, most of her work was out of print. Hurston’s writing came back into prominence beginning in 1975, when Alice Walker wrote a story for Ms. Magazine titled “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” [ PDF ] (and later retitled “Looking for Zora”). It led to the republication of Hurston’s four novels— Jonah’s Gourd Vine ; Seraph on the Suwanee ; Moses, Man of the Mountain ; and Their Eyes Were Watching God —and several short stories and plays.

3. Alice Walker pretended to be Zora Neale Hurston’s niece while searching for her unmarked grave.

Alice Walker’s abiding interest in Hurston was, in part, prompted by her time in college , where she was not exposed to a single work by a Black author. While conducting research for her own short story, she discovered Hurston’s folk stories and was inspired to look for the author’s (unmarked) grave. In 1973, Walker traveled to Eatonville, Florida, where Hurston was raised, and briefly posed as the author’s niece to scout for information [ PDF ]. While there, she met Hurston’s former classmate Mathilda Moseley —the woman who tells the “woman-is-smarter-than-man” tales in Hurston’s Mules and Men . Walker’s search finally led her to the Garden of Heavenly Rest in Fort Pierce, Florida, where Hurston spent the final years of her life.

4. Alice Walker had the wrong birth year engraved on Zora Neale Hurston’s gravestone.

Both Walker and Hurston’s biographer Robert Hemenway incorrectly recorded 1901 (instead of 1891) as Hurston’s birth year. Hurston herself is responsible for this confusion, as she was known for making up details of her life as she went along—sometimes out of necessity. After her mother’s death , Hurston—who was just 13 years old—was forced to drop out of school when her father refused to pay her tuition. Hurston left home and, for several years, worked as a maid to an actress in a traveling theater company.

At 26, to complete her high school education, Hurston fibbed about being born in 1901, erasing a full decade from her age in order to enroll in public school. Later, she dropped 19 years from her birth date when marrying her second husband, who was 25 years her junior. These colorful details led The Guardian ’s Gary Younge to affectionately describe Hurston’s autobiography as “a work of fiction.”

5. Zora Neale Hurston set many of her works in her hometown of Eatonville, Florida—except it wasn’t her hometown.

Claiming Eatonville, Florida, as her birthplace was another detail about Hurston’s life that wasn’t exactly true. Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama , and her family relocated to Eatonville, the first incorporated Black town in the U.S., when she was a toddler. Eatonville is the setting for many of her novels and short stories.

6. Zora Neale Hurston was the first Black woman to graduate from Barnard College.

In 1928, Hurston graduated with a degree in anthropology from Barnard College, and became the first Black woman to earn a degree from the institution. While there, she trained under pioneering scientist Franz Boas . With Boas’s help, she obtained a fellowship that allowed her to return to Florida to collect folklore that would later make its way into her novels Mules and Men and Tell My Horse .

7. She had a complicated friendship with Langston Hughes.

After graduating from Barnard College, Hurston went on to study anthropology as a graduate student at Columbia University. She lived in Harlem throughout this time, and in 1925, met and befriended poet, playwright, and social activist Langston Hughes .

In July 1927, the two actually went on a tour of the Deep South together (prompted, in part, by a surprise encounter outside a train station in downtown Mobile, Alabama), and explored both rural Georgia and Alabama, collecting folk tales from the area. The two also shared a patron—a white Manhattan-based socialite, Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided both with monthly stipends to support their work—although both would subsequently sever their professional ties with her (Hurston, however, reportedly stayed on friendly terms).

Although Hurston at one point referred to Hughes as “the nearest person to me on Earth,” the two had a falling out in 1931 after collaborating on a play, Mule Bone, which was based off Hurston’s short story , “The Bone of Contention.” The two fought over the rights after Hughes reportedly attempted to produce the play himself in Pennsylvania; another factor in the dissolution of their friendship were Hughes’s ongoing disputes with Mason. The pair remained estranged for the rest of Hurston’s life.

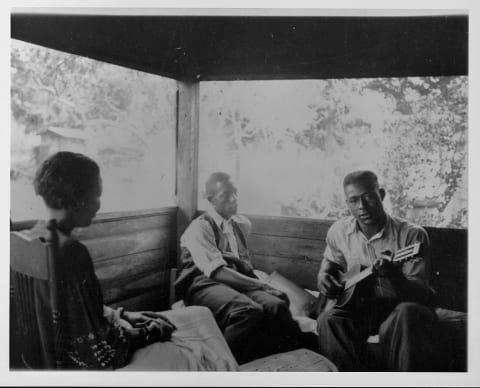

8. Zora Neale Hurston interviewed the last known survivor of the transatlantic slave trade.

In 1927 as part of her Deep South tour with Hughes, Hurston went to Plateau, Alabama, to interview 86-year-old Oluale Kossola (renamed Cudjo Lewis, but also known as Cudjoe Lewis), the last known survivor of the transatlantic slave trade. Hurston recorded the story of Lewis’s capture, the terror of the Middle Passage, his enslavement in Alabama, and his life after Emancipation.

As part of his account, he noted that many of his fellow abductees became closely bonded with one another, as they’d spend several months together during their harrowing passage to the United States. They were distressed when they were forced to part with one another in Alabama, after being sold to different enslavers. “We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother. Derefore we cry,” he told Hurston. “Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama.”

In 1931, Hurston completed Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” about Lewis’s experiences. It found no takers at the time but was published for the first time in 2018.

9. Zora Neale Hurston's best-known novel was met with serious criticism.

Hurston, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance , was at the height of her literary career in the 1930s. But adulation turned to derision with the publication of Their Eyes Were Watching God in 1937. The story of Janie Crawford, a young, working-class Black woman, and her “ ever maturing sense of self through three marriages,” the novel faced intense criticism from Hurston’s male peers and critics. Its depiction of a small, Southern town where everyday life did not include lynchings, abuse, or endless back-breaking labor led some to accuse Hurston of whitewashing the racial status quo and pandering to white audiences by perpetuating the minstrel tradition. In a 1937 review of the book, Native Son author Richard Wright wrote :

“Miss Hurston voluntarily continues in her novel the tradition which was forced upon the Negro in the theatre, that is, the minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh. Her characters eat and laugh and cry and work and kill; they swing like a pendulum eternally in that safe and narrow orbit in which America likes to see the Negro live: between laughter and tears … The sensory sweep of her novel carries no theme, no message, no thought. In the main, her novel is not addressed to the Negro, but to a white audience whose chauvinistic tastes she knows how to satisfy. She exploits that phase of Negro life which is ‘quaint,’ the phase which evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the ‘superior’ race.”

As if anticipating her critics’ accusations, Hurston presciently wrote in a 1928 essay , “I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes … No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

10. Their Eyes Were Watching God garnered major acclaim more than 40 years after its publication.

Their Eyes Were Watching God went out of print a few years after publication and remained an obscure work for nearly 30 years. Hurston’s career never quite recovered from those early reviews. In the 1950s, she worked as a maid in Miami. When she died in 1960, the author was impoverished and living in a welfare home. Nearly 20 years later, the book’s reputation was reconsidered.

Their Eyes Were Watching God was reprinted in 1978 following Alice Walker’s essay, and is now considered a classic piece of literature that was far ahead of its time. A movie adaptation , produced by Oprah Winfrey and starring Halley Berry, was released in 2005.

A version of this story was originally published in 2021 and has been updated for 2023.

Zora Neale Hurston

In a controversial letter, the versatile author expressed frustration with critics of segregation.

Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) was a Black American anthropologist, folklorist, and author. After studying with Franz Boas at Barnard College, she became a leading light of the Harlem Renaissance. She was featured in the pioneering 1925 anthology The New Negro , and her research on southern Black folklore and Caribbean voodoo practices is still influential almost 100 years on.

In this widely studied 1943 letter to the poet Countee Cullen —also a creative powerhouse of the Harlem Renaissance—Hurston confides her frustration with white liberals who were fighting segregation:

… I have no viewpoint on the subject particularly, other than a fierce desire for human justice. The rest of it is up to the individual. Personally, I have no desire for white association except where I am sought and the pleasure is mutual. That feeling grows out of my own self-respect.

She also spelled out her logic about “Negro ‘leaders’”:

I know that the Anglo-Saxon mentality is one of violence. Violence is his religion. He has gained everything he has by it, and respects nothing else. When I suggest to our “leaders” that the white man is not going to surrender for mere words what he has fought and died for, and that if we want anything substantial we must speak with the same weapons, immediately they object that I am not practical.

Read Hurston’s full letter to Cullen at the link.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- The Ethics of On-Screen Violence in The Sympathizer

- Painting Race

The Governess, in Her Own Written Words

How Renaissance Art Found Its Way to American Museums

Recent posts.

- Defining and Redefining Intersex

- Becoming the British Virgin Islands

- Demystifying Sovereign Wealth Funds

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

ARTS & CULTURE

Zora neale hurston’s ‘barracoon’ tells the story of the slave trade’s last survivor.

Published eight decades after it was written, the new book offers a first-hand account of a Middle Passage journey

Anna Diamond

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/8c/548c45a7-255d-4f47-aad2-6756a15e7404/zora-neale-hurston-photo-credit-barbara-hurston-lewis-faye-hurston-lois-gaston.jpg)

Sitting on his porch in 1928, under the Alabama sun, snacking on peaches, Cudjo Lewis (born Oluale Kossola) recounted to his guest his life story: how he came from a place in West Africa, then traversed the Middle Passage in cruel and inhumane conditions on the famed Clotilda ship, and saw the founding of the freedman community of Africatown after five years of enslavement. After two months of listening to Kossola’s tales, his interlocutor asked to take his picture. Donning his best suit, but slipping off his shoes, Kossola told her, “I want to look lak I in Affica, cause dat where I want to be.”

His listener, companion and scribe was Zora Neale Hurston, the celebrated Harlem Renaissance author of Their Eyes Were Watching God. She poured his story, told mostly in his voice and dialect, into Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” After eight decades, the manuscript is finally being published next week. (The title comes from the Spanish word for an enclosure where slaves were kept before the Middle Passage journey.)

Known mostly as a novelist, Hurston also had a career as an anthropologist. She studied under the well-known Franz Boas , who helped establish Columbia University’s anthropology department, in the 1890s, and she conducted fieldwork on voodoo in Haiti and Jamaica and folktales in the American South .

Under Boas’ guidance, Hurston was part of a school of anthropological thought that was “concerned with debunking scientific racism that many anthropologists had been involved in constructing in late-19th century and in the early years of the 20th century,” explains Deborah Thomas, a professor at University of Pennsylvania and one of the keynote speakers at a 2016 conference on Hurston’s work . “What made anthropology attractive to her was that it was a science through which she could investigate the norms of her own community and put them in relation to broader norms.”

Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo"

A newly published work from the author of the American classic Their Eyes Were Watching God , with a foreword from Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker, brilliantly illuminates the horror and injustices of slavery as it tells the true story of one of the last-known survivors of the Atlantic slave trade.

By the time Kossola was brought to the U.S., the slave trade, though not slavery, had been outlawed in the country for some 50 years. In 1860, Alabama slaveholder Timothy Meaher chartered the Clotilda , betting—correctly—that they wouldn’t be caught or tried for breaking the law. The ship’s captain, William Foster, brought 110 West Africans to Mobile, Alabama, where he and Meaher sold some and personally enslaved the rest. To hide evidence of the trafficking, Foster burned the Clotilda , the remains of which have yet to be found . Still, “press accounts and the kidnappers' willingness to share their 'escapade' meant that the story of the Clotilda was fairly well documented in the late 19th/early 20th century,” explains Hannah Durkin, a scholar of American Studies at Newcastle University.

Almost 90 years old in 1928 when he was interviewed for Barracoon , Kossola was believed to have been the last survivor of the last slave ship. As she explained in her introduction, he is “the only man on earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land behind him.”

When Hurston recorded Kossola’s life for Barracoon , it was not the first time she had met him. Nor was Hurston the only or first researcher to interview Kossola. Her peer Arthur Huff Fauset had in 1925, as had writer Emma Roche a decade before that. In 1927, Boas and Carter G. Woodson sent Hurston to gather Kossola’s story, which was used for an article she published in the Journal of Negro History . Scholars have since discovered Hurston plagiarized significantly from Roche’s interviews and speculated about Hurston’s transgression, citing her frustration with her lacking material. Despite some of Hurston’s sloppy citations and some paraphrasing, the editor of the newly released book, Debora G. Plant, explains in the afterword that there is no evidence of plagiarism in Barracoon .

Unlike other well-known slave narratives, which often include escape or bids for self-purchase, or speak to the abolition struggle, Barracoon stands alone. “His narrative does not recount a journey forward into the American Dream,” writes Plant. “It is a kind of slave narrative in reverse, journeying backwards to barracoons, betrayal, and barbarity. And then even further back, to a period of tranquility, a time of freedom, and a sense of belonging.”

Hurston’s approach to telling Kossola’s story was to totally immerse herself in his life, whether that meant helping him clean the church where he was a sexton, driving him down to the bay so he could get crabs, or bringing him summertime fruit. She built up trust with her subject starting with the basics: his name. When Hurston arrives at his home, Kossola tears up after she uses his given name: “Oh Lor’, I know it you call my name. Nobody don’t callee me my name from cross de water but you. You always callee me Kossula, jus’ lak I in de Affica soil!” (Hurston chose to use of Kossola’s vernacular throughout the book, “a vital and authenticating feature of the narrative,” writes Plant.)

With Kossola guiding the way through his story, Hurston transcribed tales of his childhood in Dahomey (now Benin), his capture at 19, his time in a barracoon, his dehumanizing arrival, and five years of enslavement in Alabama. After emancipation, Kossola and his fellow Clotilda survivors established the community of Africatown when their return home was denied to them. Hurston chronicles his attempt to maintain a family whose members were taken from him one by one, through natural causes or violence. He tells her through tears, “Cudjo feel so lonely, he can’t help he cry sometime.”

Hurston’s perspective comes in and out of the narrative only occasionally. She uses it to set the scene for her readers and to give fuller context to the experience, as when, after her subject recounts a certain memory, he is transported. She writes, “Kossula was no longer on the porch with me. He was squatting about that fire in Dahomey. His face was twitching in abysmal pain. It was a horror mask. He had forgotten that I was there. He was thinking aloud and gazing into the dead faces in the smoke.”

Hurston “eschew[ed] a questionnaire-based interview approach,” says Durkin. Hurston was patient with her subject, on days he didn’t want to talk, she didn’t press. But she was also determined, returning to his house repeatedly to get the full story.

As Kossola tells Hurston, he shared his life with her out of a desire to be known and remembered: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody dere say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’”

The process was not without its complications: As Durkin points out , Hurston’s Barracoon reporting was paid for by Charlotte Osgood Mason, a white patron of Harlem Renaissance artists. Its funding, Durkin argues, “implicated it in a history of voyeurism and cultural appropriation.” Hurston was “employed effectively as white woman’s eyes” and Mason saw her “as a collector, not an interpreter,” of the culture. Conflict between Hurston and Mason over ownership of stories, the writer’s need for funding and her desire to please her patron all complicated the anthropological work. Despite the conditions of this reporting, the manuscript is, as Durkin told me, “the most detailed account of his experiences” and “Hurston corrects some of the racist biases of earlier accounts.”

Completed in 1931, Hurston’s manuscript was never published. Viking Press expressed some interest in her proposal but demanded she change Kossola’s dialect to language, which she refused to do. Between the Great Depression’s quashing effect on the market, this early rejection, tensions with her patron, and Hurston’s interest in other projects, Barracoon was never exposed to a broad audience. In an echo of her work with Kossola, Hurston’s own life story was buried for a time, and the writer risked slipping into obscurity. In the late 1970s, writer Alice Walker spearheaded a rereading of Hurston’s work, which brought her books much deserved attention. Still dedicated to upholding and recognizing Hurston’s legacy, Walker wrote the foreword to the new book.

A man who lived across one century and two continents, Kossola’s life was marked, repeatedly and relentlessly, by loss: of his homeland, of his humanity, of his given name, of his family. For decades, his full story, from his perspective and in his voice, was also lost, but with the publication of Barracoon , it is rightfully restored.

Editor's note, May 4, 2018: This article originally stated Ms. Thomas was an organizer of a conference on Ms. Hurston's anthropology. She was a keynote speaker.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Anna Diamond | READ MORE

Anna Diamond is the former assistant editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Zora Neale Hurston Biography

Birthday: January 7 , 1891 ( Capricorn )

Born In: Notasulga

Recommended For You

Died At Age: 69

Spouse/Ex-: Albert Price III, Herbert Sheen

father: John Hurston

mother: Lucy Potts

siblings: Jack, Sarah

African Americans African American Women

Died on: January 28 , 1960

place of death: Fort Pierce

U.S. State: Alabama

Founder/Co-Founder: The Hilltop

education: Columbia University, Barnard College, Morgan State University, Howard University

awards: 1956 - Bethune-Cookman College Award - Anisfield-Wolf Book Award

You wanted to know

What impact did zora neale hurston have on the harlem renaissance, what are some of zora neale hurston's most famous literary works, how did zora neale hurston's background influence her writing, what themes did zora neale hurston explore in her writing, how was zora neale hurston's work received during her lifetime.

Recommended Lists:

See the events in life of Zora Neale Hurston in Chronological Order

How To Cite

People Also Viewed

Also Listed In

© Famous People All Rights Reserved

Famous Scientists

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neal Hurston was an American author, folklorist, and anthropologist. Publishing more than 50 plays, essays, short stories novels, her best known work is her 1937 novel “Their Eyes Were Watching God”.

She visited Haiti in 1937 and documented Voodoo practices, rituals, and beliefs. Her firsthand account of the mysteries of Voodoo, “Tell My Horse”, was published in 1938.

The Early Life of Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston was born on Notasulga, Alabama on 7 January 1891. The fifth of eight children, her father, John Hurston, was a Baptist preacher, carpenter, and tenant farmer while her mother, Lucy Ann, was a teacher at the local school. The family moved from Alabama to Eatonville in Florida, one of the first self-governing all-black municipalities in the United States, when Zora was just three years old. Zora stated that she felt like Eatonville was her “home” and she sometimes claimed that it was her birthplace.

Zora Hurston’s mother died in 1904 and her father then married Matte Moge. Hurston was sent a way by her parents to attend boarding school for a short time and she later described her childhood experiences in her 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me”. Leaving school, Hurston then worked as a maid to the lead singer of a touring Gilbert & Sullivan theatre company.

In 1917, Hurston attended Morgan College which was the high school division of the Morgan State University and a Historic All-Black school in Baltimore, Maryland. Graduating in 1918, she then attended Howard University in Washington, D.C and became an early recruit of the Zeta Phi Beta sorority. She helped found the student newspaper, The Hilltop and took courses in Greek, Spanish, English, and public speaking. Hurston earned her associates degree in 1920. A year later, she wrote “John Redding Goes to Sea”, a short story that gained her entry into the Stylus, the Alaine Locke literary club.

Hurston left Howard in 1924 and then continued her education with a scholarship at Barnard College, Columbia University in New York City in 1925. There, she received her BA in Anthropology in 1928 studying under Franz Boas; she was 37 years old. Hurston also collaborated with Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict in various anthropological works.

As an Adult

Howard married Herbert Sheen, her former classmate at Howard and a jazz musician, in 1927. He later went on to become a doctor but the marriage failed and they divorced in 1931.

Eight years later in 1939, Howard married Albert Price while she was working at the Works Progress Administration. He was 25 years younger than her and the marriage ended after just seven months.

During her later years, she not only wrote but also served as a faculty member at the North Carolina College for Negroes.

She established a school for dramatic arts in 1934 at Bethune-Cookman College in Florida and in 1956 she was given an award by the college in recognition of her contribution.

Hurston travelled extensively especially to the American South and Caribbean where she undertook anthropological work and engaged in the local culture and traditions. Sponsored by wealthy philanthropist Charlott Osgood Mason in the American South, her 1935 collection of African American folklore “Mules and Men” was based her research.

In 1936 to 37, she undertook an expedition to Jamaica and Haiti, paid for the by Guggenheim Foundation, and investigated and took part in Voodoo practices, rituals, and beliefs. Her firsthand account of the mysteries of Voodoo, “Tell My Horse”, was published in 1938.

“It is the old, old, mysticism of the world in African terms. Voodoo is a religion of creation and life. It is the worship of the sun, the water and other natural forces, but the symbolism is no better understood than that of other religions.”

Returning to America in 1938, Hurston worked for the Federal Writers’ Project collecting information for Florida’s historical and cultural collection.

Her Later Years

Hurston moved to Honduras in 1947 with a plan to examine Mayan culture and ruins. However in 1948 she was falsely accused of molesting a child; a 10year old boy. The case was dismissed but her personal life was rocked by this scandalous accusation.

She spent her last years as a freelance writer for newspapers and magazines. In 1957, she moved to Fort Pierce, Florida where she took various positions including substitute teaching.

Zora Hurston died of hypertension heart disease on 28 January 1960, aged 69, and was buried at the Garden of Heavenly Rest Cemetery in Florida. Her grave was unmarked for some time but literary scholar Charlotte Hunt and novelist Alice Walker found it and decided to mark it for Zora Neale Hurston. She is remembered for her vast literary works and her contributions to the field of anthropology. In Fort Pierce, they honor her name in a festival they call Zora Fest; a 7-day festival usually held at the end of April.

More from FamousScientists.org:

Alphabetical List of Scientists

Louis Agassiz | Maria Gaetana Agnesi | Al-Battani Abu Nasr Al-Farabi | Alhazen | Jim Al-Khalili | Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi | Mihailo Petrovic Alas | Angel Alcala | Salim Ali | Luis Alvarez | Andre Marie Ampère | Anaximander | Carl Anderson | Mary Anning | Virginia Apgar | Archimedes | Agnes Arber | Aristarchus | Aristotle | Svante Arrhenius | Oswald Avery | Amedeo Avogadro | Avicenna

Charles Babbage | Francis Bacon | Alexander Bain | John Logie Baird | Joseph Banks | Ramon Barba | John Bardeen | Charles Barkla | Ibn Battuta | William Bayliss | George Beadle | Arnold Orville Beckman | Henri Becquerel | Emil Adolf Behring | Alexander Graham Bell | Emile Berliner | Claude Bernard | Timothy John Berners-Lee | Daniel Bernoulli | Jacob Berzelius | Henry Bessemer | Hans Bethe | Homi Jehangir Bhabha | Alfred Binet | Clarence Birdseye | Kristian Birkeland | James Black | Elizabeth Blackwell | Alfred Blalock | Katharine Burr Blodgett | Franz Boas | David Bohm | Aage Bohr | Niels Bohr | Ludwig Boltzmann | Max Born | Carl Bosch | Robert Bosch | Jagadish Chandra Bose | Satyendra Nath Bose | Walther Wilhelm Georg Bothe | Robert Boyle | Lawrence Bragg | Tycho Brahe | Brahmagupta | Hennig Brand | Georg Brandt | Wernher Von Braun | J Harlen Bretz | Louis de Broglie | Alexander Brongniart | Robert Brown | Michael E. Brown | Lester R. Brown | Eduard Buchner | Linda Buck | William Buckland | Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon | Robert Bunsen | Luther Burbank | Jocelyn Bell Burnell | Macfarlane Burnet | Thomas Burnet

Benjamin Cabrera | Santiago Ramon y Cajal | Rachel Carson | George Washington Carver | Henry Cavendish | Anders Celsius | James Chadwick | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar | Erwin Chargaff | Noam Chomsky | Steven Chu | Leland Clark | John Cockcroft | Arthur Compton | Nicolaus Copernicus | Gerty Theresa Cori | Charles-Augustin de Coulomb | Jacques Cousteau | Brian Cox | Francis Crick | James Croll | Nicholas Culpeper | Marie Curie | Pierre Curie | Georges Cuvier | Adalbert Czerny

Gottlieb Daimler | John Dalton | James Dwight Dana | Charles Darwin | Humphry Davy | Peter Debye | Max Delbruck | Jean Andre Deluc | Democritus | René Descartes | Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel | Diophantus | Paul Dirac | Prokop Divis | Theodosius Dobzhansky | Frank Drake | K. Eric Drexler

John Eccles | Arthur Eddington | Thomas Edison | Paul Ehrlich | Albert Einstein | Gertrude Elion | Empedocles | Eratosthenes | Euclid | Eudoxus | Leonhard Euler

Michael Faraday | Pierre de Fermat | Enrico Fermi | Richard Feynman | Fibonacci – Leonardo of Pisa | Emil Fischer | Ronald Fisher | Alexander Fleming | John Ambrose Fleming | Howard Florey | Henry Ford | Lee De Forest | Dian Fossey | Leon Foucault | Benjamin Franklin | Rosalind Franklin | Sigmund Freud | Elizebeth Smith Friedman

Galen | Galileo Galilei | Francis Galton | Luigi Galvani | George Gamow | Martin Gardner | Carl Friedrich Gauss | Murray Gell-Mann | Sophie Germain | Willard Gibbs | William Gilbert | Sheldon Lee Glashow | Robert Goddard | Maria Goeppert-Mayer | Thomas Gold | Jane Goodall | Stephen Jay Gould | Otto von Guericke

Fritz Haber | Ernst Haeckel | Otto Hahn | Albrecht von Haller | Edmund Halley | Alister Hardy | Thomas Harriot | William Harvey | Stephen Hawking | Otto Haxel | Werner Heisenberg | Hermann von Helmholtz | Jan Baptist von Helmont | Joseph Henry | Caroline Herschel | John Herschel | William Herschel | Gustav Ludwig Hertz | Heinrich Hertz | Karl F. Herzfeld | George de Hevesy | Antony Hewish | David Hilbert | Maurice Hilleman | Hipparchus | Hippocrates | Shintaro Hirase | Dorothy Hodgkin | Robert Hooke | Frederick Gowland Hopkins | William Hopkins | Grace Murray Hopper | Frank Hornby | Jack Horner | Bernardo Houssay | Fred Hoyle | Edwin Hubble | Alexander von Humboldt | Zora Neale Hurston | James Hutton | Christiaan Huygens | Hypatia

Ernesto Illy | Jan Ingenhousz | Ernst Ising | Keisuke Ito

Mae Carol Jemison | Edward Jenner | J. Hans D. Jensen | Irene Joliot-Curie | James Prescott Joule | Percy Lavon Julian

Michio Kaku | Heike Kamerlingh Onnes | Pyotr Kapitsa | Friedrich August Kekulé | Frances Kelsey | Pearl Kendrick | Johannes Kepler | Abdul Qadeer Khan | Omar Khayyam | Alfred Kinsey | Gustav Kirchoff | Martin Klaproth | Robert Koch | Emil Kraepelin | Thomas Kuhn | Stephanie Kwolek

Joseph-Louis Lagrange | Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | Hedy Lamarr | Edwin Herbert Land | Karl Landsteiner | Pierre-Simon Laplace | Max von Laue | Antoine Lavoisier | Ernest Lawrence | Henrietta Leavitt | Antonie van Leeuwenhoek | Inge Lehmann | Gottfried Leibniz | Georges Lemaître | Leonardo da Vinci | Niccolo Leoniceno | Aldo Leopold | Rita Levi-Montalcini | Claude Levi-Strauss | Willard Frank Libby | Justus von Liebig | Carolus Linnaeus | Joseph Lister | John Locke | Hendrik Antoon Lorentz | Konrad Lorenz | Ada Lovelace | Percival Lowell | Lucretius | Charles Lyell | Trofim Lysenko