How to Write a Systematic Review Introduction

Automate every stage of your literature review to produce evidence-based research faster and more accurately.

How to write an introduction of a systematic review.

For anyone who has experience working on any sort of study, be it a review, thesis, or even just an academic paper – writing an introduction shouldn’t be a foreign concept. It generally follows the same rules, requiring it to give the readers the context of the study explaining what the review is all about: the topic it tackles, why the study was performed and the goals of its findings.

That said, most systematic reviews are governed by two guidelines that help improve the reporting of the research. These are the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement and the Cochrane handbook. Both have specifications on how to write the report, including the introduction. Look at a systematic review example , and you’ll find that it uses either one of these frameworks.

PRISMA Statement vs. Cochrane Guidelines

Learn more about distillersr.

(Article continues below)

What Is The Right Length Of A Systematic Review Introduction?

There’s no hard and fast rule about the length of a systematic review introduction. However, it’s best to keep it concise. Limit it to just two to four paragraphs, not exceeding one full page. Don’t worry, you’ll have the rest of the paper to fill with data!

What To Include In A Systematic Review Introduction

Whether or not you’re following writing guidelines, here are some pieces of information that you should include in your systematic review introduction:

Give background information about the review, including what’s already known about the topic and what you’re attempting to discover with your findings.

Definitions

This is optional, but if your review is dealing with important terms and concepts that require defining beforehand for better understanding on the readers’ part, add them to your introduction.

Delve a little into why the study topic is important, and why a systematic review must be done for it. This prompts a discussion about the knowledge gaps, a lack of cohesion in existing studies, and the potential implications of the review.

Research Question

Introduce your topic, specifically the research question that’s driving the study. Be sure that it’s new, focused, specific, and answerable, and that it ties together with your conclusion later on.

3 Reasons to Connect

Systematic Literature Reviews: An Introduction

- Proceedings of the Design Society International Conference on Engineering Design 1(1):1633-1642

- 1(1):1633-1642

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

- Conference: International Conference on Engineering Design 2019

- CentraleSupélec

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Husnia Sholihatin Amri

- Yetty Dwi Lestari

- Ronald Aloysius Romein

- Glenny Chudra

- Elsa Nandita

- Yahfizham Yahfizham

- Rungroj Wongmahasiri

- Tina Kartika

- Khanh Luong

- Hannah Gately

- Ryan Alshaikh

- Akmal Abdelfatah

- DESIGN STUD

- BMC MED RES METHODOL

- Martin Stacey

- L. Shamseer

- David Moher

- Alessandro Liberati

- David Jones

- J CLEAN PROD

- Alissa Kendall

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

When you need an introduction for a literature review

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

What to include in a literature review introduction

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

In practical terms, this implies, for instance, that the introduction in an academic literature review paper, especially one derived from a systematic literature review , is quite comprehensive. Particularly compared to the rather brief one or two introductory sentences that are often found at the beginning of a literature review section in a standard academic paper. The introduction to the literature review chapter in a thesis or dissertation again adheres to different standards.

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

In some cases, you might include:

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

Examples of literature review introductions

Example 1: an effective introduction for an academic literature review paper.

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

The paper begins with a general introduction and then proceeds to the literature review, designated by the authors as their conceptual framework. Of particular interest is the first paragraph of this conceptual framework, comprising 142 words across five sentences:

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

Phd thesis literature review chapter introduction, phd thesis literature review introduction.

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Steps to write your own literature review introduction

Master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, the best answers to "what are your plans for the future", 10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles, 37 creative ways to get motivation to study, minimalist writing for a better thesis, separating your self-worth from your phd work, how to develop an awesome phd timeline step-by-step.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps]

What is a systematic literature review?

Where are systematic literature reviews used, what types of systematic literature reviews are there, how to write a systematic literature review, 1. decide on your team, 2. formulate your question, 3. plan your research protocol, 4. search for the literature, 5. screen the literature, 6. assess the quality of the studies, 7. extract the data, 8. analyze the results, 9. interpret and present the results, registering your systematic literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a systematic literature review, related articles.

A systematic literature review is a summary, analysis, and evaluation of all the existing research on a well-formulated and specific question.

Put simply, a systematic review is a study of studies that is popular in medical and healthcare research. In this guide, we will cover:

- the definition of a systematic literature review

- the purpose of a systematic literature review

- the different types of systematic reviews

- how to write a systematic literature review

➡️ Visit our guide to the best research databases for medicine and health to find resources for your systematic review.

Systematic literature reviews can be utilized in various contexts, but they’re often relied on in clinical or healthcare settings.

Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field, and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area. They can even be used as the starting point for developing clinical practice guidelines.

A classic systematic literature review can take different approaches:

- Effectiveness reviews assess the extent to which a medical intervention or therapy achieves its intended effect. They’re the most common type of systematic literature review.

- Diagnostic test accuracy reviews produce a summary of diagnostic test performance so that their accuracy can be determined before use by healthcare professionals.

- Experiential (qualitative) reviews analyze human experiences in a cultural or social context. They can be used to assess the effectiveness of an intervention from a person-centric perspective.

- Costs/economics evaluation reviews look at the cost implications of an intervention or procedure, to assess the resources needed to implement it.

- Etiology/risk reviews usually try to determine to what degree a relationship exists between an exposure and a health outcome. This can be used to better inform healthcare planning and resource allocation.

- Psychometric reviews assess the quality of health measurement tools so that the best instrument can be selected for use.

- Prevalence/incidence reviews measure both the proportion of a population who have a disease, and how often the disease occurs.

- Prognostic reviews examine the course of a disease and its potential outcomes.

- Expert opinion/policy reviews are based around expert narrative or policy. They’re often used to complement, or in the absence of, quantitative data.

- Methodology systematic reviews can be carried out to analyze any methodological issues in the design, conduct, or review of research studies.

Writing a systematic literature review can feel like an overwhelming undertaking. After all, they can often take 6 to 18 months to complete. Below we’ve prepared a step-by-step guide on how to write a systematic literature review.

- Decide on your team.

- Formulate your question.

- Plan your research protocol.

- Search for the literature.

- Screen the literature.

- Assess the quality of the studies.

- Extract the data.

- Analyze the results.

- Interpret and present the results.

When carrying out a systematic literature review, you should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

You may also need to team up with a librarian to help with the search, literature screeners, a statistician to analyze the data, and the relevant subject experts.

Define your answerable question. Then ask yourself, “has someone written a systematic literature review on my question already?” If so, yours may not be needed. A librarian can help you answer this.

You should formulate a “well-built clinical question.” This is the process of generating a good search question. To do this, run through PICO:

- Patient or Population or Problem/Disease : who or what is the question about? Are there factors about them (e.g. age, race) that could be relevant to the question you’re trying to answer?

- Intervention : which main intervention or treatment are you considering for assessment?

- Comparison(s) or Control : is there an alternative intervention or treatment you’re considering? Your systematic literature review doesn’t have to contain a comparison, but you’ll want to stipulate at this stage, either way.

- Outcome(s) : what are you trying to measure or achieve? What’s the wider goal for the work you’ll be doing?

Now you need a detailed strategy for how you’re going to search for and evaluate the studies relating to your question.

The protocol for your systematic literature review should include:

- the objectives of your project

- the specific methods and processes that you’ll use

- the eligibility criteria of the individual studies

- how you plan to extract data from individual studies

- which analyses you’re going to carry out

For a full guide on how to systematically develop your protocol, take a look at the PRISMA checklist . PRISMA has been designed primarily to improve the reporting of systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses.

When writing a systematic literature review, your goal is to find all of the relevant studies relating to your question, so you need to search thoroughly .

This is where your librarian will come in handy again. They should be able to help you formulate a detailed search strategy, and point you to all of the best databases for your topic.

➡️ Read more on on how to efficiently search research databases .

The places to consider in your search are electronic scientific databases (the most popular are PubMed , MEDLINE , and Embase ), controlled clinical trial registers, non-English literature, raw data from published trials, references listed in primary sources, and unpublished sources known to experts in the field.

➡️ Take a look at our list of the top academic research databases .

Tip: Don’t miss out on “gray literature.” You’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it.

Don’t miss out on “gray literature” sources: those sources outside of the usual academic publishing environment. They include:

- non-peer-reviewed journals

- pharmaceutical industry files

- conference proceedings

- pharmaceutical company websites

- internal reports

Gray literature sources are more likely to contain negative conclusions, so you’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it. You should document details such as:

- The databases you search and which years they cover

- The dates you first run the searches, and when they’re updated

- Which strategies you use, including search terms

- The numbers of results obtained

➡️ Read more about gray literature .

This should be performed by your two reviewers, using the criteria documented in your research protocol. The screening is done in two phases:

- Pre-screening of all titles and abstracts, and selecting those appropriate

- Screening of the full-text articles of the selected studies

Make sure reviewers keep a log of which studies they exclude, with reasons why.

➡️ Visit our guide on what is an abstract?

Your reviewers should evaluate the methodological quality of your chosen full-text articles. Make an assessment checklist that closely aligns with your research protocol, including a consistent scoring system, calculations of the quality of each study, and sensitivity analysis.

The kinds of questions you'll come up with are:

- Were the participants really randomly allocated to their groups?

- Were the groups similar in terms of prognostic factors?

- Could the conclusions of the study have been influenced by bias?

Every step of the data extraction must be documented for transparency and replicability. Create a data extraction form and set your reviewers to work extracting data from the qualified studies.

Here’s a free detailed template for recording data extraction, from Dalhousie University. It should be adapted to your specific question.

Establish a standard measure of outcome which can be applied to each study on the basis of its effect size.

Measures of outcome for studies with:

- Binary outcomes (e.g. cured/not cured) are odds ratio and risk ratio

- Continuous outcomes (e.g. blood pressure) are means, difference in means, and standardized difference in means

- Survival or time-to-event data are hazard ratios

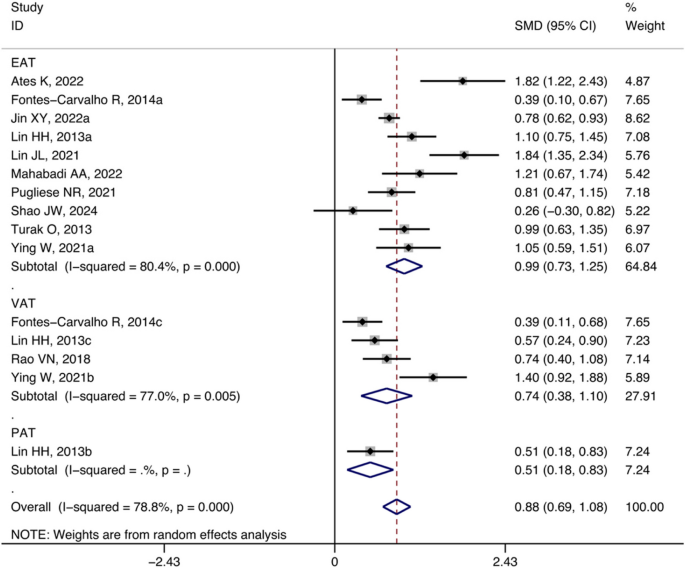

Design a table and populate it with your data results. Draw this out into a forest plot , which provides a simple visual representation of variation between the studies.

Then analyze the data for issues. These can include heterogeneity, which is when studies’ lines within the forest plot don’t overlap with any other studies. Again, record any excluded studies here for reference.

Consider different factors when interpreting your results. These include limitations, strength of evidence, biases, applicability, economic effects, and implications for future practice or research.

Apply appropriate grading of your evidence and consider the strength of your recommendations.

It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results. Take a look at these guidelines for interpreting results from the Cochrane Institute.

Before writing your systematic literature review, you can register it with OSF for additional guidance along the way. You could also register your completed work with PROSPERO .

Systematic literature reviews are often found in clinical or healthcare settings. Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area.

The first stage in carrying out a systematic literature review is to put together your team. You should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

Your systematic review should include the following details:

A literature review simply provides a summary of the literature available on a topic. A systematic review, on the other hand, is more than just a summary. It also includes an analysis and evaluation of existing research. Put simply, it's a study of studies.

The final stage of conducting a systematic literature review is interpreting and presenting the results. It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results, guidelines can be found for example from the Cochrane institute .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom.

- 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 30089228

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Keywords: evidence; guide; meta-analysis; meta-synthesis; narrative; systematic review; theory.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Soll RF, et al. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov;150:105191. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12. Early Hum Dev. 2020. PMID: 33036834

- Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Aromataris E, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):132-40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015. PMID: 26360830

- RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. Wong G, et al. BMC Med. 2013 Jan 29;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20. BMC Med. 2013. PMID: 23360661 Free PMC article.

- A Primer on Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nguyen NH, Singh S. Nguyen NH, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2018 May;38(2):103-111. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1655776. Epub 2018 Jun 5. Semin Liver Dis. 2018. PMID: 29871017 Review.

- Publication Bias and Nonreporting Found in Majority of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses in Anesthesiology Journals. Hedin RJ, Umberham BA, Detweiler BN, Kollmorgen L, Vassar M. Hedin RJ, et al. Anesth Analg. 2016 Oct;123(4):1018-25. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001452. Anesth Analg. 2016. PMID: 27537925 Review.

- The Association between Emotional Intelligence and Prosocial Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cao X, Chen J. Cao X, et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2024 Aug 28. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-02062-y. Online ahead of print. J Youth Adolesc. 2024. PMID: 39198344

- The impact of chemical pollution across major life transitions: a meta-analysis on oxidative stress in amphibians. Martin C, Capilla-Lasheras P, Monaghan P, Burraco P. Martin C, et al. Proc Biol Sci. 2024 Aug;291(2029):20241536. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2024.1536. Epub 2024 Aug 28. Proc Biol Sci. 2024. PMID: 39191283 Free PMC article.

- Target mechanisms of mindfulness-based programmes and practices: a scoping review. Maloney S, Kock M, Slaghekke Y, Radley L, Lopez-Montoyo A, Montero-Marin J, Kuyken W. Maloney S, et al. BMJ Ment Health. 2024 Aug 24;27(1):e300955. doi: 10.1136/bmjment-2023-300955. BMJ Ment Health. 2024. PMID: 39181568 Free PMC article. Review.

- Bridging disciplines-key to success when implementing planetary health in medical training curricula. Malmqvist E, Oudin A. Malmqvist E, et al. Front Public Health. 2024 Aug 6;12:1454729. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1454729. eCollection 2024. Front Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39165783 Free PMC article. Review.

- Strength of evidence for five happiness strategies. Puterman E, Zieff G, Stoner L. Puterman E, et al. Nat Hum Behav. 2024 Aug 12. doi: 10.1038/s41562-024-01954-0. Online ahead of print. Nat Hum Behav. 2024. PMID: 39134738 No abstract available.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.112(1); Jan-Feb 2015

Systematically Reviewing the Literature: Building the Evidence for Health Care Quality

There are important research and non-research reasons to systematically review the literature. This article describes a step-by-step process to systematically review the literature along with links to key resources. An example of a graduate program using systematic literature reviews to link research and quality improvement practices is also provided.

Introduction

Systematic reviews that summarize the available information on a topic are an important part of evidence-based health care. There are both research and non-research reasons for undertaking a literature review. It is important to systematically review the literature when one would like to justify the need for a study, to update personal knowledge and practice, to evaluate current practices, to develop and update guidelines for practice, and to develop work related policies. 1 A systematic review draws upon the best health services research principles and methods to address: What is the state of the evidence on the selected topic? The systematic process enables others to reproduce the methods and to make a rational determination of whether to accept the results of the review. An abundance of articles on systematic reviews exist focusing on different aspects of systematic reviews. 2 – 9 The purpose of this article is to describe a step by step process of systematically reviewing the health care literature and provide links to key resources.

Systematic Review Process: Six Key Steps

Six key steps to systematically review the literature are outlined in Table 1 and discussed here.

Systematic Review Steps

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | Formulate the Question and Refine the Topic |

| 2 | Search, Retrieve, and Select Relevant Articles |

| 3 | Assess Quality |

| 4 | Extract Data and Information |

| 5 | Analyze and Synthesize Data and Information |

| 6 | Write the Systematic Review |

1. Formulate the Question and Refine the Topic

When preparing a topic to conduct a systematic review, it is important to ask at the outset, “What exactly am I looking for?” Hopefully it seems like an obvious step, but explicitly writing a one or two sentence statement of the topic before you begin to search is often overlooked. It is important for several reasons; in particular because, although we usually think we know what we are searching for, in truth our mental image of a topic is often quite fuzzy. The act of writing something concise and intelligible to a reader, even if you are the only one who will read it, clarifies your thoughts and can inspire you to ask key questions. In addition, in subsequent steps of the review process, when you begin to develop a strategy for searching the literature, your topic statement is the ready raw material from which you can extract the key concepts and terminology for your strategies. The medical and related health literature is massive, so the more precise and specific your understanding of your information need, the better your results will be when you search.

2. Search, Retrieve, and Select Relevant Articles

The retrieval tools chosen to search the literature should be determined by the purpose of the search. Questions to ask include: For what and by whom will the information be used? A topical expert or a novice? Am I looking for a simple fact? A comprehensive overview on the topic? Exploration of a new topic? A systematic review? For the purpose of a systematic review of journal research in the area of health care, PubMed or Medline is the most appropriate retrieval tool to start with, however other databases may be useful ( Table 2 ). In particular, Google Scholar allows one to search the same set of articles as PubMed/MEDLINE, in addition to some from other disciplines, but it lacks a number of key advanced search features that a skilled searcher can exploit in PubMed/MEDLINE.

Examples of Electronic Bibliographic Databases Specific to Health Care

| Bibliographic Databases | Topics | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) | nursing and allied health | |

| EMBASE | international biomedical and pharmacological database | |

| Medline/Pubmed | biomedical literature, life science journals, and online books | |

| PsycINFO | behavioral sciences and mental health | |

| Science Citation Index (SCI) | science, technology, and medicine | |

| SCOPUS | scientific, technical, medical, social sciences, arts, and humanities published after 1995 | |

| The Cochrane Library | evidence of effectiveness of interventions |

Note: These databases may be available through university or hospital library systems.

An effective way to search the literature is to break the topic into different “building blocks.” The building blocks approach is the most systematic and works the best in periodical databases such as PubMed/MEDLINE. The “blocks” in a “building blocks” strategy consist of the key concepts in the search topic. For example, let’s say we are interested in researching about mobile phone-based interventions for monitoring of patient status or disease management. We could break the topic into the following concepts or blocks: 1. Mobile phones, 2. patient monitoring, and 3. Disease management. Gather synonyms and related terms to represent each concept and match to available subject headings in databases that offer them. Organize the resulting concepts into individual queries. Run the queries and examine your results to find relevant items and suggest query modifications to improve your results. Revise and re-run your strategy based on your observations. Repeat this process until you are satisfied or further modifications produce no improvements. For example in Medline, these terms would be used in this search and combined as follows: cellular phone AND (ambulatory monitoring OR disease management), where each of the key word phrases is an official subject heading in the MEDLINE vocabulary. Keep detailed notes on the literature search, as it will need to be reported in the methods section of the systematic review paper. Careful noting of search strategies also allows you to revisit a topic in the future and confidently replicate the same results, with the addition of those subsequently published on your topic.

3. Assess Quality

There is no consensus on the best way to assess study quality. Many quality assessment tools include issues such as: appropriateness of study design to the research objective, risk of bias, generalizability, statistical issues, quality of the intervention, and quality of reporting. Reporting guidelines for most literature types are available at the EQUATOR Network website ( http://www.equator-network.org/ ). These guidelines are a useful starting point; however they should not be used for assessing study quality.

4. Extract Data and Information

Extract information from each eligible article into a standardized format to permit the findings to be summarized. This will involve building one or more tables. When making tables each row should represent an article and each column a variable. Not all of the information that is extracted into the tables will end up in the paper. All of the information that is extracted from the eligible articles will help you obtain an overview of the topic, however you will want to reserve the use of tables in the literature review paper for the more complex information. All tables should be introduced and discussed in the narrative of the literature review. An example of an evidence summary table is presented in Table 3 .

Example of an evidence summary table

| Author/Yr | Sample Size | Technology | Duration | Delivery Frequency | Control | Intervention | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months | C vs. I | |||||||

| Benhamou 2007 | 30 | SMS, V, PDA, I | 12 | Weekly | No weekly SMS support | Weekly SMS diabetes treatment advice from their health care providers based on weekly transfer of SMBG and QOL survey every three months | HbA1c | +0.12 vs − 0.14%, P<0.10 |

| SMBG | +5 vs −6 mg/dl, P=0.06 | |||||||

| QOL score | 0.0 vs +5.6, p< .05 | |||||||

| Satisfaction with Life | −0.01 vs + 8.1, P<.05 | |||||||

| Hypo episodes | 79.1 vs 69.1/patient, NS | |||||||

| No of BG tests/day | −.16 vs − .11/day, NS | |||||||

| Marquez Contreras 2004 | 104 | SMS | 4 | Twice/Week | Standard treatment | SMS messages with recommendations to control Blood Pressure | % of compliers | 51.5% vs. 64.7%, P=NS |

| Rate of compliance | 88.1%vs. 91.9%, p=NS | |||||||

| % of patients with BP control | 85.7% vs. 84.4%, P=NS |

Notes: BP = blood pressure, HbA1c = Hemoglobin A1c, Hypo = hypoglycemic, I = Internet, NS = not significant, PDA = personal digital assistant, QOL = quality of life, SMBG = self-monitored blood glucose, SMS = short message service, V = voice

5. Analyze and Synthesize Data and information

The findings from individual studies are analyzed and synthesized so that the overall effectiveness of the intervention can be determined. It should also be observed at this time if the effect of an intervention is comparable in different studies, participants, and settings.

6. Write the Systematic Review

The PRISMA 12 and ENTREQ 13 checklists can be useful resources when writing a systematic review. These uniform reporting tools focus on how to write coherent and comprehensive reviews that facilitate readers and reviewers in evaluating the relative strengths and weaknesses. A systematic literature review has the same structure as an original research article:

TITLE : The systematic review title should indicate the content. The title should reflect the research question, however it should be a statement and not a question. The research question and the title should have similar key words.

STRUCTURED ABSTRACT: The structured abstract recaps the background, methods, results and conclusion in usually 250 words or less.

INTRODUCTION: The introduction summarizes the topic or problem and specifies the practical significance for the systematic review. The first paragraph or two of the paper should capture the attention of the reader. It might be dramatic, statistical, or descriptive, but above all, it should be interesting and very relevant to the research question. The topic or problem is linked with earlier research through previous attempts to solve the problem. Gaps in the literature regarding research and practice should also be noted. The final sentence of the introduction should clearly state the purpose of the systematic review.

METHODS: The methods provide a specification of the study protocol with enough information so that others can reproduce the results. It is important to include information on the:

- Eligibility criteria for studies: Who are the patients or subjects? What are the study characteristics, interventions, and outcomes? Were there language restrictions?

- Literature search: What databases were searched? Which key search terms were used? Which years were searched?

- Study selection: What was the study selection method? Was the title screened first, followed by the abstract, and finally the full text of the article?

- Data extraction: What data and information will be extracted from the articles?

- Data analysis: What are the statistical methods for handling any quantitative data?

RESULTS: The results should also be well-organized. One way to approach the results is to include information on the:

- Search results: What are the numbers of articles identified, excluded, and ultimately eligible?

- Study characteristics: What are the type and number of subjects? What are the methodological features of the studies?

- Study quality score: What is the overall quality of included studies? Does the quality of the included studies affect the outcome of the results?

- Results of the study: What are the overall results and outcomes? Could the literature be divided into themes or categories?

DISCUSSION: The discussion begins with a nonnumeric summary of the results. Next, gaps in the literature as well as limitations of the included articles are discussed with respect to the impact that they have on the reliability of the results. The final paragraph provides conclusions as well as implications for future research and current practice. For example, questions for future research on this topic are revealed, as well as whether or not practice should change as a result of the review.

REFERENCES: A complete bibliographical list of all journal articles, reports, books, and other media referred to in the systematic review should be included at the end of the paper. Referencing software can facilitate the compilation of citations and is useful in terms of ensuring the reference list is accurate and complete.

The following resources may be helpful when writing a systematic review:

CEBM: Centre for Evidence-based Medicine. Dedicated to the practice, teaching and dissemination of high quality evidence based medicine to improve health care Available at: http://www.cebm.net/ .

CITING MEDICINE: The National Library of Medicine Style Guide for Authors, Editors, and Publishers. This resource provides guidance in compiling, revising, formatting, and setting reference standards. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7265/ .

EQUATOR NETWORK: Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. The EQUATOR Network promotes the transparent and accurate reporting of research studies. Available at: http://www.equator-network.org/ .

ICMJE RECOMMENDATIONS: International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. The ICJME recommendations are followed by a large number of journals. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/about-icmje/faqs/icmje-recommendations/ .

PRISMA STATEMENT: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Authors can utilize the PRISMA Statement checklist to improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Available at: http://prisma-statement.org .

THE COCHRANE COLLABORATION: A reliable source for making evidence generated through research useful for informing decisions about health. Available at: http://www.cochrane.org/ .

Examples of Systematic Reviews To Link Research and Quality Improvement

Over the past 17 years more than 300 learners, including physicians, nurses, and health administrators have completed a course as part of a Master of Health Administration or a Master of Science in Health Informatics degree at the University of Missouri. An objective of the course is to educate health informatics and health administration professionals about how to utilize a systematic, scientific, and evidence-based approach to literature searching, appraisal, and synthesis. Learners in the course conduct a systematic review of the literature on a health care topic of their choosing that could suggest quality improvement in their organization. Students select topics that make sense in terms of their core educational competencies and are related to their work. The categories of topics include public health, leadership, information management, health information technology, electronic medical records, telehealth, patient/clinician safety, treatment/screening evaluation cost/finance, human resources, planning and marketing, supply chain, education/training, policies and regulations, access, and satisfaction. Some learners have published their systematic literature reviews 14 – 15 . Qualitative comments from the students indicate that the course is well received and the skills learned in the course are applicable to a variety of health care settings.

Undertaking a literature review includes identification of a topic of interest, searching and retrieving the appropriate literature, assessing quality, extracting data and information, analyzing and synthesizing the findings, and writing a report. A structured step-by-step approach facilitates the development of a complete and informed literature review.

Suzanne Austin Boren, PhD, MHA, (above) is Associate Professor and Director of Academic Programs, and David Moxley, MLIS, is Clinical Instructor and Associate Director of Executive Programs. Both are in the Department of Health Management and Informatics at the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

Contact: ude.iruossim.htlaeh@snerob

None reported.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

Published on 15 June 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on 18 July 2024.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesise all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question ‘What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?’

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs meta-analysis, systematic review vs literature review, systematic review vs scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce research bias . The methods are repeatable , and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesise the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesising all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesising means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesise the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesise results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarise and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimise bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimise research b ias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinised by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarise all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fourth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomised control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective(s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesise the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Grey literature: Grey literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of grey literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of grey literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Grey literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

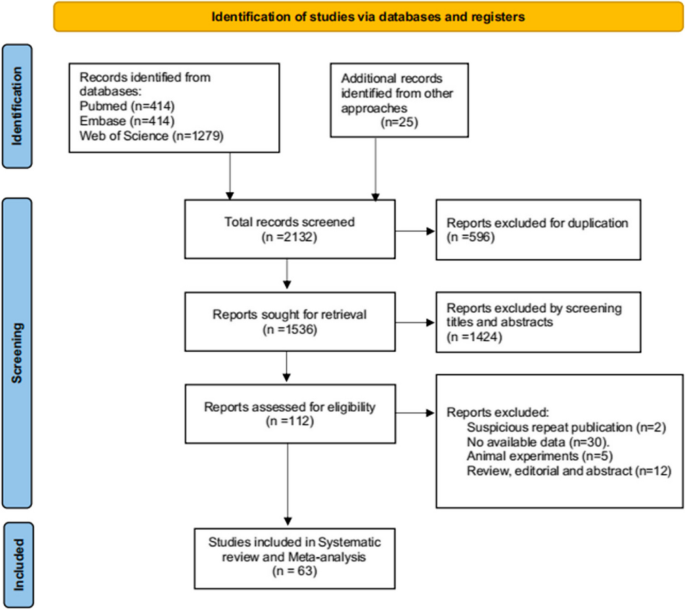

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarise what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgement of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomised into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesise the data

Synthesising the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesising the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarise the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarise and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analysed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Turney, S. (2024, July 17). Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/systematic-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, what is peer review | types & examples.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

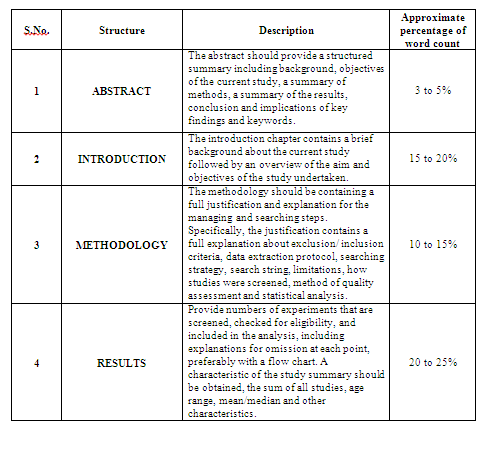

Writing An Introduction Of A Systematic Review Of Literature – A Quick Reference Table

Are Languages Still A Major Barrier To Global Science

English Language As A Barrier To Publish In High Impact Factor Journals – Quick Tips To Overcome

Systematic reviews are performed for synthesizing the evidence of multiple scientific investigations to answer a specific research question in a manner that is reproducible and transparent while seeking to include all published evidence on the topic followed evaluating the quality of this evidence. A Systematic review remains among the best forms of evidence and reduces the bias inherent in other methods. In the disciplines of public policy health and health sciences, systematic reviews have become the main methodology. Previously, some have provided that structure research ought to embrace the systematic review, but limited guidance is available. This section presented an overview of the various steps involved in performing a systematic review. This information should provide proper guidance for those who are conducting a systematic literature review (Davis, 2019 ).

Key characteristics of the systematic review

Identification of a research question, inclusion & exclusion criteria.

- Rigorous & systematic search of the literature

- Critical appraisal of included studies

- Data extraction and management

- Analysis & interpretation of results

- Report for publication

Different types of the systematic review

The systematic review mainly classified into three types, including (1) meta-analysis, (2) quantitative analysis and (3) qualitative analysis.

Meta-analysis: A meta-analysis utilizes statistical methods to incorporate appraisals of impact from relevant studies that are independent yet comparable and outline them.

Quantitative: To combine the results of 2 or more studies by using statistical analysis is called quantitative analysis.

Qualitative: The qualitative analysis generally defined as the results of the relevant studies are summarized but not combined statistically.

Steps to be followed before drafting a systematic review