Local Histories

Tim's History of British Towns, Cities and So Much More

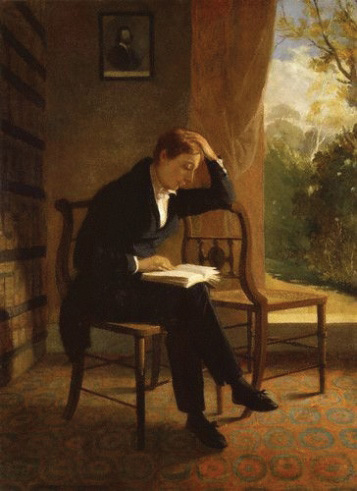

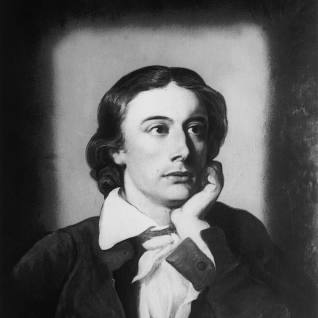

A Brief Biography of John Keats

By Tim Lambert

His Early Life

John Keats was one of England’s greatest poets. He was born in London on 31 October 1795. His father Thomas Keats was an innkeeper. His mother was called Frances. The couple had 5 children. In 1803 John Keats went to Clarke’s School in Enfield.

However, in 1804 tragedy struck when his father was killed by falling off a horse. His mother quickly remarried. However, she soon separated from her new husband. John Keats then went to live with his grandmother. John was reconciled with his mother by 1809 but by then she was ill. She died in 1810.

The Great Poet

In 1810 John left school and in 1811 he was apprenticed to a surgeon and apothecary in Edmonton. As a teenager, Keats became passionately fond of poetry and when he was about 18 he wrote his first poem, one entitled ‘Imitation of Spenser’.

In 1815 John became a student at Guy’s Hospital in London. But he continued to write poetry. In 1816 he had a poem published for the first time, in a magazine called The Examiner. It was a sonnet called ‘O Solitude!’. Also in 1816, Keats passed his exams. Then in 1817, he published a book called ‘Poems’. However, it was not a success, attracting little interest.

Nevertheless, Keats continued writing. His epic poem Endymion was published in 1818. During 1818-1819 Keats continued to write great poems including ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, ‘Hyperion’, ‘The Eve of St Agnes’, and ‘Ode to Autumn’.

However, in 1820 Keats fell ill with tuberculosis. He went to Italy in the hope that the climate might help. Nevertheless, John Keats died in Rome on 23 February 1821. He was only 25. Keats was buried in the Protestant cemetery.

Last revised 2023

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

(1795-1821)

Who Was John Keats?

John Keats devoted his short life to the perfection of poetry marked by vivid imagery, great sensuous appeal and an attempt to express a philosophy through classical legend. In 1818 he went on a walking tour in the Lake District. His exposure and overexertion on that trip brought on the first symptoms of the tuberculosis, which ended his life.

Early Years

A revered English poet whose short life spanned just 25 years, John Keats was born October 31, 1795, in London, England. He was the oldest of Thomas and Frances Keats’ four children. Keats lost his parents at an early age. He was eight years old when his father, a livery stable-keeper, was killed after being trampled by a horse.

His father's death had a profound effect on the young boy's life. In a more abstract sense, it shaped Keats' understanding for the human condition, both its suffering and its loss. This tragedy and others helped ground Keats' later poetry—one that found its beauty and grandeur from the human experience.

In a more mundane sense, Keats' father's death greatly disrupted the family's financial security. His mother, Frances, seemed to have launched a series of missteps and mistakes after her husband’s death; she quickly remarried and just as quickly lost a good portion of the family's wealth. After her second marriage fell apart, Frances left the family, leaving her children in the care of her mother.

She eventually returned to her children's life, but her life was in tatters. In early 1810, she died of tuberculosis.

During this period, Keats found solace and comfort in art and literature. At Enfield Academy, where he started shortly before his father's passing, Keats proved to be a voracious reader. He also became close to the school's headmaster, John Clarke, who served as a sort of a father figure to the orphaned student and encouraged Keats' interest in literature.

Back home, Keats' maternal grandmother turned over control of the family's finances, which was considerable at the time, to a London merchant named Richard Abbey. Overzealous in protecting the family's money, Abbey showed himself to be reluctant to let the Keats children spend much of it. He refused to be forthcoming about how much money the family actually had and in some cases was downright deceitful.

There is some debate as to whose decision it was to pull Keats out of Enfield, but in the fall of 1810, Keats left the school for studies to become a surgeon. He eventually studied medicine at a London hospital and became a licensed apothecary in 1816.

Early Poetry

But Keats' career in medicine never truly took off. Even as he studied medicine, Keats’ devotion to literature and the arts never ceased. Through his friend, Cowden Clarke, whose father was the headmaster at Enfield, Keats met publisher, Leigh Hunt of The Examiner .

Hunt's radicalism and biting pen had landed him in prison in 1813 for libeling Prince Regent. Hunt, though, had an eye for talent and was an early supporter of Keats poetry and became his first publisher. Through Hunt, Keats was introduced to a world of politics that was new to him and had greatly influenced what he put on the page. In honor of Hunt, Keats wrote the sonnet, "Written on the Day that Mr. Leigh Hunt Left Prison."

In addition to affirming Keats' standing as a poet, Hunt also introduced the young poet to a group of other English poets, including Percy Bysshe Shelley and Williams Wordsworth.

In 1817 Keats leveraged his new friendships to publish his first volume of poetry, Poems by John Keats . The following year, Keats' published "Endymion," a mammoth four-thousand line poem based on the Greek myth of the same name.

Keats had written the poem in the summer and fall of 1817, committing himself to at least 40 lines a day. He completed the work in November of that year and it was published in April 1818.

Keats' daring and bold style earned him nothing but criticism from two of England's more revered publications, Blackwood's Magazine and the Quarterly Review . The attacks were an extension of heavy criticism lobbed at Hunt and his cadre of young poets. The most damning of those pieces had come from Blackwood's, whose piece, "On the Cockney School of Poetry," shook Keats and made him nervous to publish "Endymion."

Keats' hesitation was warranted. Upon its publication the lengthy poem received a lashing from the more conventional poetry community. One critic called the work, the "imperturbable driveling idiocy of Endymion." Others found the four-book structure and its general flow hard to follow and confusing.

Recovering Poet

How much of an effect this criticism had on Keats is uncertain, but it is clear that he did take notice of it. But Shelley's later accounts of how the criticism destroyed the young poet and led to his declining health, however, have been refuted.

Keats in fact, had already moved beyond "Endymion" even before it was published. By the end of 1817, he was reexamining poetry's role in society. In lengthy letters to friends, Keats outlined his vision of a kind of poetry that drew its beauty from real world human experience rather than some mythical grandeur.

Keats was also formulating the thinking behind his most famous doctrine, Negative Capability , which is the idea that humans are capable of transcending intellectual or social constraints and far exceed, creatively or intellectually, what human nature is thought to allow.

In effect Keats was responding to his critics, and conventional thinking in general, which sought to squeeze the human experience into a closed system with tidy labels and rational relationships. Keats saw a world more chaotic, more creative than what others he felt, would permit.

The Mature Poet

In the summer of 1818, Keats took a walking tour in Northern England and Scotland. He returned home later that year to care for his brother, Tom, who'd fallen deeply ill with tuberculosis.

Keats, who around this time fell in love with a woman named Fanny Brawne, continued to write. He'd proven prolific for much of the past year. His work included his first Shakespearean sonnet, "When I have fears that I may cease to be," which was published in January 1818.

Two months later, Keats published "Isabella," a poem that tells the story of a woman who falls in love with a man beneath her social standing, instead of the man her family has chosen her to marry. The work was based on a story from Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, and it's one Keats himself would grow to dislike.

His work also included the beautiful "To Autumn," a sensuous work published in 1820 that describes ripening fruit, sleepy workers, and a maturing sun. The poem, and others, demonstrated a style Keats himself had crafted all his own, one that was filled with more sensualities than any contemporary Romantic poetry.

Keats' writing also revolved around a poem he called "Hyperion," an ambitious Romantic piece inspired by Greek myth that told the story of the Titans' despondency after their losses to the Olympians.

But the death of Keats' brother halted his writing. He finally returned to the work in late 1819, rewriting his unfinished poem with a new title, "The Fall of Hyperion," which would go unpublished until more than three decades after Keats' death.

This, of course, speaks to the small audience for Keats' poetry during his lifetime. In all, the poet published three volumes of poetry during his life but managed to sell just a combined 200 copies of his work by the time of his death in 1821. His third and final volume of poetry, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems , was published in July 1820.

Final Years and Death

In 1819 Keats contracted tuberculosis. His health deteriorated quickly. Soon after his last volume of poetry was published, he ventured off to Italy with his close friend, the painter Joseph Severn, on the advice of his doctor, who had told him he needed to be in a warmer climate for the winter.

The trip marked the end of his romance with Brawne. His health issues and his own dreams of becoming a successful writer had stifled their chances of ever getting married.

Keats arrived in Rome in November of that year and for a brief time started to feel better. But within a month, he was back in bed, suffering from a high temperature. The last few months of his life proved particularly painful for the poet.

His doctor in Rome placed Keats on a strict diet that consisted of a single anchovy and a piece of bread per day in order to limit the flow of blood to the stomach. He also induced heavy bleeding, resulting in Keats suffering from both a lack of oxygen and a lack of food.

Keats' agony was so severe that at one point he pressed his doctor and asked him, "How long is this posthumous existence of mine to go on?"

Keats' death came on February 23, 1821. It's believed he was clutching the hand of his friend, Severn, at the time of his passing.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: John Keats

- Birth Year: 1795

- Birth date: October 31, 1795

- Birth City: London

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: English Romantic lyric poet John Keats was dedicated to the perfection of poetry marked by vivid imagery that expressed a philosophy through classical legend.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Death Year: 1821

- Death date: February 23, 1821

- Death City: Rome

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: John Keats Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/john-keats

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 12, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- If Poetry comes not as naturally as Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Biography of John Keats, English Romantic Poet

Leemage / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

- M.A., Journalism, New York University.

- B.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

John Keats (October 31, 1795– February 23, 1821) was an English Romantic poet of the second generation, alongside Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. He is best known for his odes, including "Ode to a Grecian Urn," "Ode to a Nightingale," and his long form poem Endymion . His usage of sensual imagery and statements such as “beauty is truth and truth is beauty” made him a precursor of aestheticism.

Fast Facts: John Keats

- Known For: Romantic poet known for his search for perfection in poetry and his use of vivid imagery. His poems are recognized as some of the best in the English language.

- Born: October 31, 1795 in London, England

- Parents: Thomas Keats and Frances Jennings

- Died: February 23, 1821 in Rome, Italy

- Education: King's College, London

- Selected Works: “Sleep and Poetry” (1816), “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (1819), “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819 ), “Hyperion” (1818-19), Endymion (1818)

- Notable Quote: "Beauty is truth, truth is beauty,'—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

John Keats was born in London on October 31, 1795. His parents were Thomas Keats, a hostler at the stables at the Swan and Hoop Inn, which he would later manage, and Frances Jennings. He had three younger siblings: George, Thomas, and Frances Mary, known as Fanny. His father died in April 1804 in a horse riding accident, without leaving a will.

In 1803, Keats was sent to John Clarke's school in Enfield, which was close to his grandparents’ house and had a curriculum that was more progressive and modern than what was found in similar institutions. John Clarke fostered his interest in classical studies and history. Charles Cowden Clarke, who was the headmaster’s son, became a mentor figure for Keats, and introduced him to Renaissance writers Torquato Tasso, Spenser, and the works of George Chapman. A temperamental boy, young Keats was both indolent and belligerent, but starting at age 13, he channeled his energies into the pursuit of academic excellence, to the point that, in midsummer 1809, he won his first academic prize.

When Keats was 14, his mother died of tuberculosis, and Richard Abbey and Jon Sandell were appointed as the children's guardians. That same year, Keats left John Clarke to become an apprentice to surgeon and apothecary Thomas Hammond, who was the doctor of his mother’s side of the family. He lived in the attic above Hammond’s practice until 1813.

Keats wrote his first poem, “An Imitation of Spenser,” in 1814, aged 19. After finishing his apprenticeship with Hammond, Keats enrolled as a medical student at Guy’s Hospital in October 1815. While there, he started assisting senior surgeons at the hospital during surgeries, which was a job of significant responsibility. His job was time consuming and it hindered his creative output, which caused significant distress. He had ambition as a poet, and he admired the likes of Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron.

He received his apothecary license in 1816, which allowed him to be a professional apothecary, physician, and surgeon, but instead, he announced to his guardian that he would pursue poetry. His first printed poem was the sonnet “O Solitude,” which appeared in Leigh Hunt’s magazine The Examiner. In the summer of 1816, while vacationing with Charles Cowden Clarke in the town of Margate, he started working on “Caligate.” Once that summer was over, he resumed his studies to become a member of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Poems (1817)

Sleep and poetry.

What is more gentle than a wind in summer? What is more soothing than the pretty hummer That stays one moment in an open flower, And buzzes cheerily from bower to bower? What is more tranquil than a musk-rose blowing In a green island, far from all men's knowing? More healthful than the leafiness of dales? More secret than a nest of nightingales? More serene than Cordelia's countenance? More full of visions than a high romance? What, but thee Sleep? Soft closer of our eyes! Low murmurer of tender lullabies! Light hoverer around our happy pillows! Wreather of poppy buds, and weeping willows! Silent entangler of a beauty's tresses! Most happy listener! when the morning blesses Thee for enlivening all the cheerful eyes That glance so brightly at the new sun-rise(“Sleep and Poetry,” lines 1-18)

Thanks to Clarke, Keats met Leigh Hunt in October of 1816, who, in turn introduced him to Thomas Barnes, editor of the Times, conductor Thomas Novello, and the poet John Hamilton Reynolds. He published his first collection, Poems, which includes “Sleep and poetry” and “I stood Tiptoe,” but it was panned by the critics. Charles and James Ollier, the publishers, felt ashamed of it, and the collection aroused little interest. Keats promptly went to other publishers, Taylor and Hessey, who strongly supported his work and, one month after the publication of Poems , he already had an advance and a contract for a new book. Hessey also became a close friend of Keats. Through him and his partner, Keats met the Eton-educated lawyer Richard Woodhouse, a fervent admirer of Keats who would serve as his legal advisor. Woodhouse became an avid collector of Keats-related materials, known as Keatsiana, and his collection is, to this day, one of the most important sources of informations on Keats' work. The young poet also became part of William Hazlitt’s circle, which cemented his reputation as an exponent of a new school of poetry.

Upon formally leaving his hospital training in December 1816, Keats' health took a major hit. He left the damp rooms of London in favor of the village of Hampstead in April 1817 to live with his brothers, but both he and his brother George ended up taking care of their brother Tom, who had contracted tuberculosis. This new living situation brought him close to Samuel T. Coleridge, an elder poet of the first generation of Romantics, who lived in Highgate. On April 11, 1818, the two took a walk together on Hampstead Heath, where they talked about “nightingales, poetry, poetical sensation, and metaphysics.”

In the Summer of 1818, Keats started touring Scotland, Ireland, and the Lake District, but by July of 1818, while on the Isle of Mull, he caught a terrible cold that debilitated him to the point that he had to return South. Keats' brother, Tom, died of Tuberculosis on December 1st, 1818.

A Great Year (1818-19)

Ode on a grecian urn.

Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring'd legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

“Ode on a Grecian Urn,” lines 1—10

Keats moved to Wentworth place, on the edge of Hampstead Heath, the property of his friend Charles Armitage Brown. This is the period when he wrote his most mature work: five out of his six great odes were composed in the Spring of 1819: "Ode to Psyche," "Ode to a Nightingale," "Ode on a Grecian Urn," "Ode on Melancholy," "Ode on Indolence." In 1818, he also published Endymion, which, much like Poems, was not appreciated by critics. Harsh assessments include “imperturbable drivelling idiocy” by John Gibson Lockhart for The Quarterly Review, who also thought that Keats would have been better off resuming his career as an apothecary, deeming “to be a starved apothecary” a wiser thing than a starved poet. Lockhart was also the one who lumped together Hunt, Hazlitt, and Keats as member as “the Cockney School,” which was spiteful of both their poetic style and their lack of a traditional elite education that also signified belonging to the aristocracy or upper class.

At some point in 1819, Keats was so short on money that he considered becoming a journalist or a surgeon on a ship. In 1819, he also wrote "The Eve of St. Agnes," "La Belle Dame sans Merci," "Hyperion," "Lamia," and the play Otho the Great. He presented these poems to his publishers for consideration for a new book project, but they were unimpressed by them. They criticized "The Eve of St. Agnes" for its "sense of pettish disgust," while they considered "Don Juan" unfit for ladies.

Rome (1820-21)

Over the course of the year 1820, Keats’ symptoms of tuberculosis got more and more serious. He coughed up blood twice in February of 1820 and then was bled by the attending physician. Leigh Hunt took care of him, but after the summer, Keats had to agree to move to Rome with his friend Joseph Severn. The voyage, via the ship Maria Crowther, was not smooth, as dead calm alternated with storms and, upon docking, they were quarantined due to a cholera outbreak in Britain. He arrived in Rome on November 14, even though by that time, he could no longer find the warmer climate that was recommended to him for his health. Upon getting to Rome, Keats also started having stomach problems on top of respiratory problems, and he was denied opium for pain relief, as it was thought he might use it as a quick way to commit suicide. Despite Severn’s nursing, Keats was in a constant state of agony to the point that upon waking up, he would cry because he was still alive.

Keats died in Rome on February 23, 1821. His remains rest in Rome’s Protestant cemetery. His tombstone bears the inscription “Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water.” Seven weeks after the funeral, Shelley wrote the elegy Adonais, which memorialized Keats. It contains 495 lines and 55 Spenserian stanzas.

Bright Stars: Female Acquaintances

Bright star.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art— Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night And watching, with eternal lids apart, Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite, The moving waters at their priestlike task Of pure ablution round earth's human shores, Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask Of snow upon the mountains and the moors— No—yet still stedfast, still unchangeable, Pillow'd upon my fair love's ripening breast, To feel for ever its soft fall and swell, Awake for ever in a sweet unrest, Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath, And so live ever—or else swoon to death.

There were two important women in John Keats’ life. The first one was Isabella Jones, whom he met in 1817. Keats was both intellectually and sexually attracted to her, and wrote about frequenting “her rooms” in the winter of 1818-19 and about their physical relationship, saying that he “warmed with her” and “kissed her” in letters to his brother George. He then met Fanny Brawne in the fall of 1818. She had talent for dressmaking, languages, and a theatrical bent. By late fall 1818, their relationship had deepened, and, throughout the following year, Keats lent her books such as Dante’s Inferno. By the summer of 1819, they had an informal engagement, mainly due to Keats’ dire straits, and their relationship remained unconsummated. In the last months of their relationship, Keats’ love took a darker and melancholic turn, and in poems such as "La Belle Dame sans Merci" and "The Eve of St. Agnes," love is closely associated with death. They parted in September 1820 when Keats, due to his deteriorating health, was advised to move to warmer climates. He left for Rome knowing that death was near: he died five months later.

The famed sonnet "Bright Star" was first composed for Isabella Jones, but he gave it to Fanny Brawne after revising it.

Themes and Literary Style

Keats often juxtaposed the comic and the serious in poems that are not primarily funny. Much like his fellow Romantics, Keats struggled with the legacy of prominent poets before him. They retained an oppressive power that hindered the liberation of the imagination. Milton is the most notable case: Romantics both worshipped him and tried to distance themselves from him, and the same happened to Keats. His first Hyperion displayed Miltonic influences, which led him to discard it, and critics saw it as a poem “that might have been written by John Milton, but one that was unmistakably by no other than John Keats.”

Poet William Butler Yeats , in the eloquent simplicities of Per Amica Silentia Lunae , saw Keats as having “been born with that thirst for luxury common to many at the outsetting of the Romantic Movement,” and thought therefore that the poet of To Autumn “but gave us his dream of luxury.”

Keats died young, aged 25, with only a three-year-long writing career. Nonetheless, he left a substantial body of work that makes him more than a “poet of promise.” His mystique was also heightened by his alleged humble origins, as he was presented as a lowlife and someone who received a sparse education.

Shelley, in his preface to Adonais (1821), described Keats as "delicate," "fragile," and "blighted in the bud": "a pale flower by some sad maiden cherished ... The bloom, whose petals nipt before they blew / Died on the promise of the fruit," wrote Shelley.

Keats himself underestimated his writerly ability. "I have left no immortal work behind me—nothing to make my friends proud of my memory—but I have lov'd the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remember’d," he wrote to Fanny Brawne.

Richard Monckton Milnes published the first biography of Keats in 1848, which fully inserted him into the canon. The Encyclopaedia Britannica extolled the virtues of Keats in numerous instances: in 1880, Swinburne wrote in his entry on John Keats that "the Ode to a Nightingale, [is] one of the final masterpieces of human work in all time and for all ages," while the 1888 edition stated that, "Of these [odes] perhaps the two nearest to absolute perfection, to the triumphant achievement and accomplishment of the very utmost beauty possible to human words, may be that of to Autumn and that on a Grecian Urn." In the 20th century, Wilfred Owen, W.B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot were all inspired by Keats.

As far as other arts are concerned, given how sensual his writing was, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood admired him, and painters depicted scenes of Keats poems, such as "La Belle Dame Sans Merci," "The Eve of St. Agnes," and "Isabella."

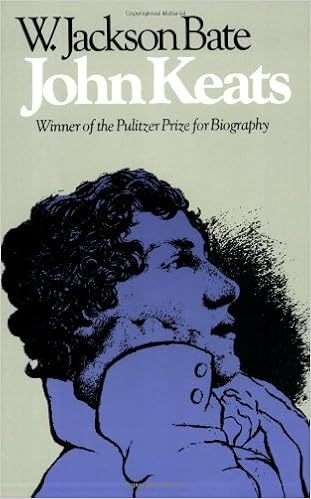

- Bate, Walter Jackson. John Keats . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Bloom, Harold. John Keats . Chelsea House, 2007.

- White, Robert S. John Keats a Literary Life . Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- 14 Classic Poems Everyone Should Know

- How to Write an Ode

- Biography of Lord Byron, English Poet and Aristocrat

- 7 Poems That Evoke Autumn

- Singing the Old Songs: Traditional and Literary Ballads

- What Is Ekphrastic Poetry?

- Biography of Mary Shelley, English Novelist, Author of 'Frankenstein'

- Biography of Alexander Pope, England's Most Quoted Poet

- What Is Poetry, and How Is It Different?

- Dreaming of Xanadu: A Guide to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan”

- Biography of John Milton, Author of Paradise Lost

- William Turner, English Romantic Landscape Painter

- Biography of Pablo Neruda, Chilean Poet and Diplomat

- A Collection of Classic Love Poetry for Your Sweetheart

- An Introduction to the Romantic Period

Biography Online

John Keats Biography

John Keats was an influential Romantic poet, who has become one of the most widely respected and loved British poets.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

– John Keats, Ode on a Grecian Urn .

Short Bio John Keats

When he was young, Keats lost both his father (aged 8) and later his mother (aged 14). Orphaned at an early age, Keats and his siblings were looked after by their grandmother. It also placed the family in a difficult financial situation – Keats would struggle with money throughout his life.

Job as surgeon

Having finished school, Keats took an apprenticeship at Guy’s Hospital, London in October 1815. In the early nineteenth century, the job of a surgeon was very challenging; in the absence of anaesthetic and modern technology, there was only a limited amount doctors could do to ease the condition of patients. This suffering of patients and people was a theme Keats would later incorporate into his poetry.

Life as a poet

It was hoped that this medical training would give Keats a secure career and financial income. However, in 1816, despite making good progress, Keats told his guardian that he couldn’t become a surgeon and felt compelled to try and make a career as a poet. It was a decision that his guardians failed to understand because, at the time, there was little hope of making money from writing poetry.

However, Keats was introduced to some of the leading literary figures of the day, such as Leigh Hunt, Percy Shelley and poet John Hamilton Reynolds. This enabled him to publish his first collection of poems, but they were not a critical success and sold very few copies.

From 1817, John spent considerable time nursing his brother Tom, who was suffering from tuberculosis. In 1818, they went on a walking tour of northern England and Scotland. His brother’s conditions deteriorated, and, weakened by cold himself, it is likely that John Keats contracted the ‘family disease’ of tuberculosis.

Despite the difficulty of his nursing his dying brother and suffering a series of financial difficulties, Keats began his most prolific period of writing. Based on the edge of Hampstead Heath he composed five of his six odes.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk: ’Tis not through envy of thy happy lot, But being too happy in thine happiness,— That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees, In some melodious plot Of beechen green, and shadows numberless, Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

First stanza of “Ode to a Nightingale”, May 1819

Around this time, he also met with the great poet William Wordsworth and Charles Lamb.

Publishing of Endymion

In 1818, his great work Endymion was published, however, many reviews were highly critical of Keat’s ‘immaturity’, it was labelled by some, including Byron as ‘Cockney Poetry’ – suggesting the poet used uncouth language. The edition sold very few copies, leaving both Keats and the publisher with a feeling of shame. Despite this critical failure, Keats gave an indication he strove only for genius. He did retain a faith in his poetry. As he writes:

“I was never afraid of failure; for I would sooner fail than not be among the greatest.”

Letter to James Hessey (October 9, 1818)

Despite the support of some literary friends, this critical review left a profound mark on Keats. Throughout his short life, he felt he had been a failure, unable to leave any lasting mark on poetry. On his deathbed, he would later write scathing letters saying perhaps he should have sold out to mammon (money) rather than pursue the purity of his poetic journey. In his last letter to Shelley, he writes bitterly:

“…A modern work it is said must have a purpose, which may be the God – an artist must serve Mammon – he must have “self concentration” selfishness perhaps. .. ”(16 August 1820) [ link ]

In this last letter, Keats also describes his personal view:

“My imagination is a Monastery and I am its Monk.”

(16 August 1820) [ link ]

John Keats and Fanny Browne

In 1818, he first came into contact with Frances (Fanny) Brawne. She was 18 at the time, and a close friendship arose between them. However, the relationship was overshadowed by Keats’ nursing of his brother Tom; also the lack of finance meant that Keats had no realistic chance of being able to marry. They wrote many intimate letters, in which Keats often bared his soul and the depth of his feeling:

“My love has made me selfish. I cannot exist without you — I am forgetful of every thing but seeing you again — my Life seems to stop there — I see no further. You have absorb’d me.”

The relationship was also cut short by the aggravation of Keat’s tuberculosis. By September 1820, Keats was very fragile from the effects of the disease. He was advised to move to warmer climes, and so with the help of friends, he was booked on a ship to Italy. However, after a rough sea journey, Keats’ health failed to improve; within a few months of arriving in Italy, he died from the disease that had claimed his mother and brother.

The last months were a period of great turmoil and difficulty. Often denied, even a small quantity of opium to ease the physical pain, Keats was racked with a feeling of insufficiency relating to the negative reviews his poetry had received.

Keats was buried in a cemetery in Rome, with the simple inscription on his tombstone ” Young English poet – Here lies one whose name was writ in water .”

Keats had died at the age of 25, after a period of just six years writing poetry. During his lifetime, he was a commercial and critical failure, selling only around 200 copies of books.

However, within a few years of his death, his reputation was to sharply rise – becoming one of Britain’s best-loved poets.

In particular, the Cambridge Apostles and Lord Tennyson (who became a popular Poet Laureate) admired the poetry of Keats and this helped make him known to more people. Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Millais and Rossetti were inspired by Keats’ imagery and used some of his poetic images in their paintings. By 1848, Richard Milnes had written the first biography of Keats.

In the Twentieth Century, many poets such as Wilfred Owen , W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot said Keats was a key literary inspiration.

The Twentieth Century also saw considerable interest in the letters of Keats. Keats devoted many letters to the subject of poetry – offering a unique discussion of the role and importance of poetry.

“Poetry should be great and unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself, but with its subject.”

– Letter to John Hamilton Reynolds (February 3, 1818)

The poetry of Keats is wide-ranging and includes some of the most memorable lines in English poetry. His most famous poems such as the Odes are famous for their lyrical perfection in their poetic invocation of beauty. But, Keats, in poems such as Endymion , also wrote challenging poetry striving to challenge established currents of thought and question why things were.

“None can usurp this height… But those to whom the miseries of the world Are misery, and will not let them rest.”

Keats, “The Fall of Hyperion: A Dream”, Canto I, l. 147 (1819)

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of John Keats ”, Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net Published 24th Jan 2010. Last updated 18 February 2018.

John Keats – by W. Jackson Bate – winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Biography at Amazon

Related pages

External links

- Life and Works of John Keats

- Keats at British Library

- Poetry of Keats

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

read this poet’s poems

English Romantic poet John Keats was born on October 31, 1795, in London. The oldest of four children, he lost both his parents at a young age. His father, a livery-stable keeper, died when Keats was eight; his mother died of tuberculosis six years later. After his mother’s death, Keats’s maternal grandmother appointed two London merchants, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians. Abbey, a prosperous tea broker, assumed the bulk of this responsibility, while Sandell played only a minor role. When Keats was fifteen, Abbey withdrew him from the Clarke School, Enfield, to apprentice with an apothecary-surgeon and study medicine in a London hospital. In 1816 Keats became a licensed apothecary, but he never practiced his profession, deciding instead to write poetry.

Around this time, Keats met Leigh Hunt, an influential editor of the Examiner , who published his sonnets “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” and “O Solitude.” Hunt also introduced Keats to a circle of literary men, including the poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Wordsworth . The group’s influence enabled Keats to see his first volume, Poems by John Keats , published in 1817. Shelley, who was fond of Keats, had advised him to develop a more substantial body of work before publishing it. Keats, who was not as fond of Shelley, did not follow his advice. Endymion , a four-thousand-line erotic/allegorical romance based on the Greek myth of the same name, appeared the following year. Two of the most influential critical magazines of the time, the Quarterly Review and Blackwood’s Magazine , attacked the collection. Calling the romantic verse of Hunt’s literary circle “the Cockney school of poetry,” Blackwood’s declared Endymion to be nonsense and recommended that Keats give up poetry. Shelley, who privately disliked Endymion but recognized Keats’s genius, wrote a more favorable review, but it was never published. Shelley also exaggerated the effect that the criticism had on Keats, attributing his declining health over the following years to a spirit broken by the negative reviews.

Keats spent the summer of 1818 on a walking tour in Northern England and Scotland, returning home to care for his brother, Tom, who suffered from tuberculosis. While nursing his brother, Keats met and fell in love with a woman named Fanny Brawne. Writing some of his finest poetry between 1818 and 1819, Keats mainly worked on “Hyperion,” a Miltonic blank-verse epic of the Greek creation myth. He stopped writing “Hyperion” upon the death of his brother, after completing only a small portion, but in late 1819 he returned to the piece and rewrote it as “The Fall of Hyperion” (unpublished until 1856). That same autumn Keats contracted tuberculosis, and by the following February he felt that death was already upon him, referring to the present as his “posthumous existence.”

In July 1820, he published his third and best volume of poetry, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems . The three title poems, dealing with mythical and legendary themes of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance times, are rich in imagery and phrasing. The volume also contains the unfinished “Hyperion,” and three poems considered among the finest in the English language, “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode on Melancholy,” and “Ode to a Nightingale.” The book received enthusiastic praise from Hunt, Shelley, Charles Lamb, and others, and in August, Frances Jeffrey, influential editor of the Edinburgh Review , wrote a review praising both the new book and Endymion .

The fragment “Hyperion” was considered by Keats’s contemporaries to be his greatest achievement, but by that time he had reached an advanced stage of his disease and was too ill to be encouraged. He continued a correspondence with Fanny Brawne and—when he could no longer bear to write to her directly—her mother, but his failing health and his literary ambitions prevented their getting married. Under his doctor’s orders to seek a warm climate for the winter, Keats went to Rome with his friend, the painter Joseph Severn. He died there on February 23, 1821, at the age of twenty-five, and was buried in the Protestant cemetery.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for “common speech” within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

Walt Whitman

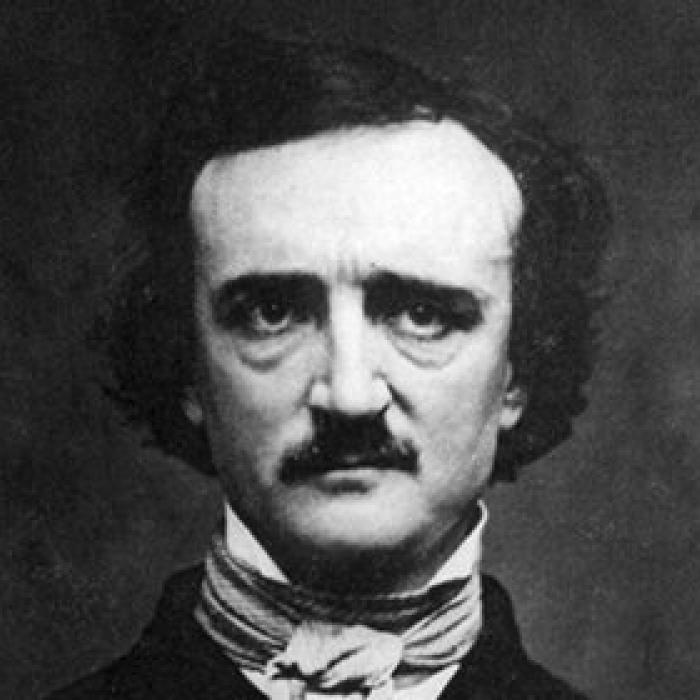

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

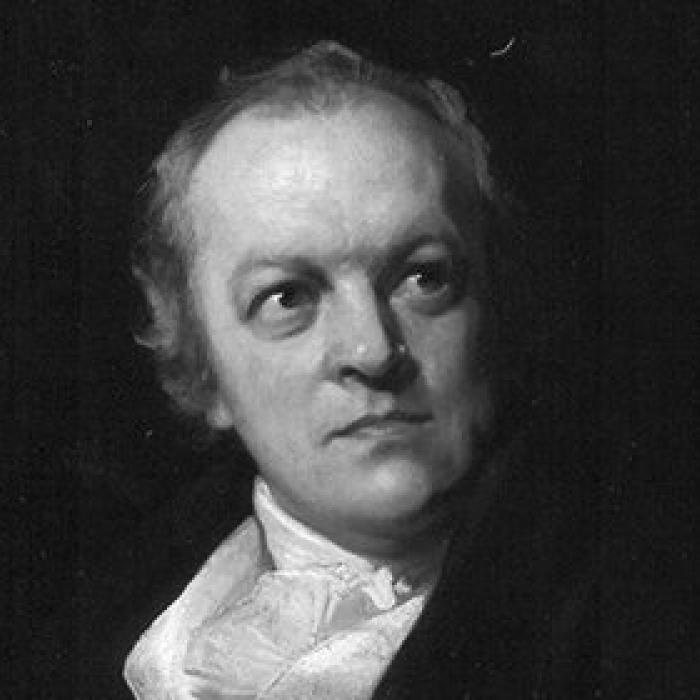

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

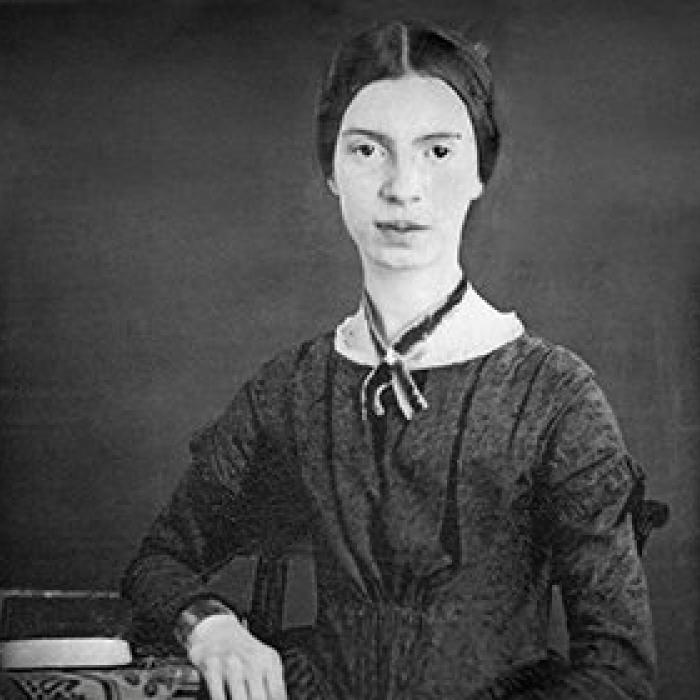

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. While she was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. She died in Amherst in 1886, and the first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

English History

The Life of John Keats (1795-1821) – Key Facts, Information & Biography

John Keats was born on 31 October 1795, the first of Frances Jennings and Thomas Keats’s five children, one of whom died in infancy. His parents had been wed for barely a year when John was born. His maternal grandparents, John and Alice Jennings, were well-off and, upon his parents’ marriage, had entrusted the management of their livery business to Thomas. These stables, called the ‘Swan and Hoop’, were located in north London and provided horses for hire to adjacent neighborhoods.

Thomas and Frances lived at the stables through the births of their first three children. George was born on 28 February 1797 and Thomas on 18 November 1799. After their births, the young couple felt successful enough to move to a separate house on Craven Street, about a half-mile from the business. Here, on 28 April 1801, their son Edward was born; he died shortly thereafter. And on 3 June 1803, the last of their children and only daughter, Frances Mary, was born.

Details of Keats’s early life are scarce. During the last few years of his life, letters allow one to track him virtually week-to-week but his childhood and adolescence are another matter. Indeed, virtually all the information known is in the form of reminisces, many taken years after Keats had died. Understandably, one must view these memories with some skepticism. Whether discussing Keats’s physical appearance (his brother George said he resembled their mother while a family friend said it was the father) or his pastimes, these sources often contradict one another.

Keats’s father, Thomas Keats, died on Sunday, 15 April 1804, while returning home from visiting John and George at Enfield school. It was believed his horse slipped on the cobblestones and threw him to the ground. Suffering a skull fracture, he lived for a few hours after being found by a night watchman. Barely two months later, on 27 June 1804, Frances Jennings remarried. Grief-stricken and unable to conduct the livery business herself, she wed a minor bank clerk named William Rawlings. Rawlings was a fortune-hunter and the marriage was a failure. The children were immediately sent to live with their grandmother and, a few years later, their mother joined them. She had left Rawlings and, with him, the stables she had inherited from her former husband. From this time on, her health declined precipitously.

The upheaval in the children’s lives continued. On 8 March 1805, their grandfather died and the financial turmoil which haunted Keats’s life began. For John Jennings, a kindly and generous man, was also gullible; he had hired a land surveyor, not a lawyer, to draft his will and the result was an ill-written and vague document. Mr. Jennings’s real wishes were obscured and open to interpretation. The specifics of the case are far too detailed for this generalized sketch, but are available in any biography of Keats. There is also a book called The Keats Inheritance which can be found in any good university library. It is worth mentioning here simply because Keats’s entire adult life was spent struggling with money.

The fight over shares in the estate began shortly after Jennings’s death and ended long after John Keats’s death. Their grandmother, now almost seventy, was left with half the income she and her husband had lived on. To practice economy, she moved to a smaller home and attempted to save what she could. In her own will, she appointed Richard Abbey trustee and guardian of her grandchildren. This appointment was to have tragic consequences for all the Keats children, but most especially John.

Mrs. Jennings’s new home was close to Enfield, where the youngest son Tom was sent to join his brothers at school. At Enfield, the Keats brothers were well-liked and popular. John caught the attention of his schoolfellows; their reminisces stress his bravery and generosity to others. They also mentioned his sensitivity, a trait which did not prevent him from engaging in fights. As schoolfellow Edward Holmes remembered, “The generosity & daring of his character – in passions of tears or outrageous fits of laughter always in extremes will help to paint Keats in his boyhood.” But Holmes, who later became a well-known music critic, stressed that Keats “was a boy whom any one might easily have fancied would become great – but rather in some military capacity than in literature.” Simply put, there was little in John’s character which would indicate a great future in poetry.

The money problems which began with his grandfather’s death were exacerbated by his mother’s death in mid-March of 1810 and his grandmother’s death in December of 1814. Keats, as the eldest child, was old enough to try and help his mother through her illness; her death impressed itself upon him deeply. His grandmother, whose home had been his for nearly a decade, was also sorely missed. Richard Abbey now became the primary ‘adult’ influence in Keats’s life. Abbey withdrew John and George from school and apprenticed John to an apothecary/surgeon named Dr. Hammond. Keats displayed great aptitude for the difficult job though his enthusiasm waned as his interest in poetry grew. For the next three years, he studied medicine. He also wrote his first poem in 1814, a few months before his grandmother died.

Abbey was executor of her estate and thus guardian of her grandchildren. He took Keats’s younger sister Fanny into his home. Using the vague wording of John Jennings’ will as at pretext, he often withheld money from the children. He did this despite his legal obligations, largely because he believed they would waste the money and become destitute. The actual amount of the inheritance was also never made clear. And so the Keats children struggled for money while Abbey wrangled with the inheritance, whether through malice or disinterest. The psychological and physical effects of this poverty were profound.

Abbey’s own conservative austerity made him unsympathetic to the children. He had a low opinion of their temperaments and maturity. This opinion was formed by the behavior of their mother during her marriage and estrangement from Rawlings. There had been rumors of Frances wandering the streets in disarray and living in sin with various men. Abbey wanted the Keats sons to achieve success in respectable, stable careers, hence his desire for John to become an apothecary. Like most Englishmen, he did not consider poetry, particularly as practiced by a middle-class boy, to be a good career choice. Poetry was the provenance of the noble and wealthy who possessed the leisure and education to indulge in wordplay. John Keats could not afford such a lifestyle. This attitude was pervasive enough to influence early reviews of Keats’s poetry as influential magazines such as Blackwood’s called him ‘ignorant and unsettled’, a ‘pretender’ to a poetic career.

On 1 October 1815, Keats entered Guy’s Hospital for more formal training. Henry Stephens, a classmate and later the inventor of blue-black ink, described the would-be poet: Whilst attending lectures, he [Keats] would sit & instead of Copying out the lecture, would often scribble some doggerel rhymes, among the Notes of Lecture, particularly if he got hold of another Student’s Syllabus – In my Syllabus of Chemical Lectures he scribbled many lines on the paper cover, This cover has been long torn off, except one small piece on which is the following fragment of Doggerel rhyme Give me women, wine and snuff Until I cry out “hold, enough!” You may do so sans objection Till the day of resurrection; For, bless my beard, they aye shall be My beloved Trinity. Stephens’s sensibility made him excise the reference to women and the last two lines when he told this story to Keats’s first biographer, RM Milnes. In March 1816, Keats became a dresser, applying bandages and, in the summer, a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. But the most momentous event was the publication of his first poem in The Examiner. There was little critical reception, but Keats was attracting new friends who shared his literary tastes, among them Leigh Hunt, Benjamin Haydon and John Reynolds. Hunt was the earliest and most enthusiastic supporter of Keats. As a critic on the fringes of the literary establishment, he did all he could to champion his friend’s career. Oddly, Keats came to be critical of Hunt’s personal and professional affairs, which was a rare lapse in his usually generous nature. In December, Hunt quoted Keats in his famous ‘Young Poets’ article. He had already given him the nickname ‘Junkets’, from Keats’s Cockney pronunciation of his own name. By this time, Keats had decided to end his medical training. He had no illusions of the difficulty of a poetic career but he was determined to follow his dream. He was already borrowing as many books as possible from various friends, and became an ardent admirer of Spenser and Shakespeare . This devotion to reading, which had begun after his father’s death and remained throughout his life, inspired his most famous poem of 1816, On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer: Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold, And many goodly states and kingdoms seen; Round many western islands have I been Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold. Oft of one wide expanse had I been told That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne; Yet did I never breathe its pure serene Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold: Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He star’d at the Pacific–and all his men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise– Silent, upon a peak in Darien. The following year, 1817, was even more momentous for Keats. While living with his brothers George and Tom in Cheapside, he continued to write poetry; his first volume, Poems, was published by C and J Ollier on 3 March. In a friendly spirit, he gave a copy to Abbey, who told him when they next met, “Well, John, I have read your book, & it reminds me of the Quaker’s Horse which was hard to catch, & good for nothing when he was caught – So, Your Book is hard to understand & good for nothing when it is understood.” Years later, when relating the story, Abbey implied the comment had been humorous but Keats had taken it to heart: “Do you know, I don’t think he ever forgave me for uttering this Opinion.” The book sold very badly and Keats soon left for another publisher, Taylor and Hessey.

It was around this time that the Keats brothers decided to move to the healthier area of north London, settling in Hampstead. Both George and Tom had been employed by Abbey but left their jobs before the move. In Hampstead, the brothers made numerous friends, most notably Charles Wentworth Dilke and his wife Maria. George Keats’s departure from Abbey’s business also marked the beginning of various schemes to make money, one of which required some of John’s inheritance. The next year, he would marry and move to America.

In April 1817, shortly after giving Abbey his first book, Keats embarked on a four-month tour through Carisbrooke, Canterbury, Hastings, etc He also wrote the first books of Endymion and other compositions. The unaccustomed solitude and intense work affected Keats deeply. For the first time in his life, he was able to focus completely on his poetry and realize both the extent of his own ambition and ability. Touching upon his own native genius reassured him that the decision to risk all for a literary career was indeed worthwhile; however, the solitude affected him enough to send him back to the reassuring comfort of Tom’s companionship. His friend, the painter Haydon, would encourage Keats to seek as much solitude as possible while writing. However much he personally needed the support of his brothers, it could not help his poetic development. But the lonely, grinding work of creation, of writing and editing new lines, was difficult. The early losses of his parents and grandparents had undeniably fostered the strong bond between the Keats children; only death would break it. Despite Haydon’s kind advice, the brothers would stay together until George’s emigration and Tom’s death. Keats could not help but become overly involved in his brothers’ lives, often to the sacrifice of his writing and peace of mind.

The trip had another salutary affect upon Keats’s life. During his travels, he first met Joseph Severn, the young painter who would eventually nurse him during his final illness in Rome. Severn was immediately struck by Keats’s genius, which seemed to manifest itself in his ability to literally feel the poetic essence of all things. Haydon confirmed Severn’s impression: “The humming of the bee, the sight of a flower, the glitter of the sun, seemed to make his nature tremble!” This was a very Wordsworthian attribute, as Keats surely understood. He admired much of Wordsworth’s work, but his own love of Elizabethan wordplay gave his poetry an extravagance and sensuality which Wordsworth lacked.

Keats also met Benjamin Bailey and Charles Brown. In September, Keats stayed with his new friend Bailey at Oxford and wrote the third book of Endymion; the fourth book would be completed in late November. Bailey was easily the wealthiest of Keats’s new friends and his lodgings were comfortable and cheerful. They were also full of the books which Keats loved. His writing progressed largely because of Bailey’s own work schedule. Bailey would begin his studies directly after breakfast and Keats would also take up his pen. Later in the afternoon, he would read his work to Bailey and they would talk and go for long walks. Like Severn, Bailey genuinely admired Keats. His open appreciation encouraged the shy poet’s work and conversation. Keats rarely spoke of personal matters to anyone but, while in Oxford, he opened up to Bailey. His young friend did not gain a favorable impression of George or Tom, who were at the time having a far too expensive holiday in Paris, complete with a visit to an infamous brother and gaming house. Bailey also learned that Abbey was discouraging Fanny from meeting with her brothers. In response, Keats continued to write his sister, reassuring her that she was both his “only sister” and “dearest friend.”

This time in Oxford allowed Bailey to offer insights into Keats’s character which are free of condescension or exaggeration: “The errors of Keats’s character, – and they were as transparent as a weed in a pure and lucent stream of water, – resulted from his education; rather from his want of education. But like the Thames waters, when taken out to sea, he had the rare quality of purifying himself;….” He was also aware of Keats’s innately generous nature; the poet “allowed for people’s faults more than any man I ever knew.”

Their readings together also confirmed Bailey’s understanding that, though his own education was more vast, Keats’s power of insight was infinitely greater. Destined for a career in the Church and intensely studying theology, Bailey engaged Keats sin many religious talks. The poet was a skeptical believer, but always open to new ideas. The time at Oxford was allowing him to think deeply and consistently about his poetic instincts. He also began to closely study his earlier verse, attempting to create his own philosophy of poetry. The impact of the month in Oxford on Keats’s development as a man and poet was immense. It marked a new understanding of his desires and purpose, and a new dedication to a literary career. But when he returned to London at the start of the Oxford Michaelmas term on 5 October, it was with noticeable regret. George and Tom had also returned to their cramped rooms. Keats enjoyed his brothers’ companionship, but the long hours of work he had done in Oxford could not be replicated here. The noise and lack of privacy made poetry nearly impossible. At first, he took long walks around the neighborhood, visiting Haydon and Hunt. His old friends were quarreling, with Hunt criticizing Haydon’s paintings and Keats’s Endymion. “I am quite disgusted with literary Men,” Keats wrote to the sympathetic Bailey.

But there was another problem as well, a mysterious one which exacerbated his impatient and frustrated mood. Some biographers believe that Keats had contracted a venereal disease while in Oxford. He was particularly ill at Hampstead in October, and treated himself with mercury, writing to Bailey, “The little Mercury I have taken has corrected the Poison and improved my Health.” The infection lasted for two months, for he mentioned it again to Bailey in late November. There was also a letter in late October in which Keats joked about some sort of sexual experience. In this letter, he also remarks upon inquiries about his health; several friends had supposed he was suffering the pangs of romantic love, but he assured Bailey it was quite the opposite. This issue is discussed at length in Robert Gittings’ biography of Keats. The poet’s sexual experience has always frustrated biographers, but the bawdy contents of several letters and poems suggests that Keats had some experience.

(It is the use of mercury which biographers have used to support the theory of venereal disease. As Keats had occasion to know from the lectures at St Guy’s, mercury was used to treat syphilis and gonorrhea. However, it was also used to treat common respiratory illnesses. Since Keats spent the latter days of October indoors completing Endymion, it is possible he merely had a cold. It’s impossible to know the truth of the matter; for opposing views, read Robert Gittings’s biograpy and Walter Wells’s medical study.)

The forced rest of October allowed him to continue, though with interruption, the development of his philosophy. He could now read and critique even his great heroes Wordsworth and Coleridge; his contemporaries Shelley and Byron were also studied. Keats was now confident enough of his own abilities to judge their innate worth. He felt himself to be charting a new path, while growing increasingly frustrated with the constraints of Endymion. Taken as a whole, the work is inconsistent and often frustrating, but there are passages of great beauty and power. Reading it, we can witness the young poet (and remember, Keats was about to turn just 22) struggling to find his natural voice, finding it, and then developing its consistency.

But in the final months of 1817, even as he recovered from his mysterious illness, he had a more pressing cause for worry – his brother Tom was ill, and becoming more so, in a ghastly repeat of their mother’s death. Tom’s illness would come to occupy his brother’s thoughts for most of the next year. In December 1817, there was a welcome distraction – the chance to meet his great hero Wordsworth. Haydon arranged the meeting and later famously described it: “I said he has just finished an exquisite ode to Pan – and as he had not a copy I begged Keats to repeat it – which he did in his usual half chant, (most touching) walking up & down the room – when he had done I felt really, as if I had heard a young Apollo – Wordsworth drily said – ‘a Very pretty piece of Paganism’ – This was unfeeling, & unworthy of his high Genius to a young Worshipper like Keats – & Keats felt it deeply – so that if Keats has said any thing severe about our Friend; it was because he was wounded – and though he dined with Wordsworth after at my table – he never forgave him.” The above description is quite famous but there is reason to doubt its accuracy. Haydon first told the story decades later; his journals at the time make no mention of it. Also, Keats’s attitude towards Wordsworth did not noticeably change. It is clear from other accounts that some exchange occurred between the two poets, but it seemed more to amuse Keats than offend him. He was now confident enough of his own abilities to recognize Wordsworth’s less attractive traits.

In mid-December, George and Tom traveled to Teignmouth for Tom’s health. The tuberculosis that had killed their mother was not yet suspected in the youngest Keats; but he was ill and seemed to grow worse as the weeks passed. Keats spent the next two months revising and copying Endymion and attending lectures by the great critic William Hazlitt. Endymion was published in late spring by Taylor and Hessey. His brother’s declining health brought Keats to Teignmouth in March, and he spent the next two months there, nursing Tom while writing Isabella, or the Pot of Basil. Bailey invited him to Oxford again; he had read Endymion several times and was impressed enough to write a glowing review for a local paper. But Tom’s condition prevented the trip.

Meanwhile, George was planning his wedding to Georgiana Wylie and their emigration to America. Of his inheritance of £1700, he would leave £500 behind; this was to pay his outstanding debts and give his brothers extra money. It was also repayment of various loans Keats had made him over the years. George married on 28 May 1818, with Keats signing the register as witness. Three weeks later, George and his new wife left England.

For the first time in their young lives, the brothers were split apart. Keats felt the separation keenly. Their orphaned upbringing had made them extraordinarily close and now George was gone, Fanny was locked away with Abbey’s family, and poor Tom was dying, as Keats finally admitted to himself. They had originally hoped for a recovery, perhaps spurred by a trip to the warm climates of Portugal or Italy, but the plans came to naught. He wrote in a maudlin mood to Bailey: “I have two Brothers, one is driven by the ‘burden of Society’ to America, the other, with an exquisite love of Life, is in a lingering state. I have a Sister too and may not follow them, either to America or to the Grave.”

Keats’s affection for Georgiana gave him some consolation; just twenty years old upon leaving England, she had already impressed him with her kind, warm-hearted nature and appreciation of his work. Also, Tom had made plans to return to London and allow their landlady Mrs. Bentley to nurse him at Well Walk. This would allow Keats the opportunity to travel with Charles Brown, whose acquaintance he had made in the fateful summer of 1817. They toured the Lake District for several weeks, and then did an extensive walking tour of Scotland. It was a wonderful trip for the poet. Not only was he distracted from his personal problems, but he and Brown became close friends. And the beautiful landscapes he encountered inspired his writing. He described them in a lengthy letter to Tom: “….[T]hey make one forget the divisions of life; age, youth, poverty and riches; and refine one’s sensual vision into a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and steadfast over the wonders of the great Power. ….I never forget my stature so completely. I live in the eye; and my imagination, surpassed, is at rest. ….I shall learn poetry here and shall henceforth write more than ever.”

These were indeed prophetic words, foreshadowing his incredible accomplishments of 1819. This trip, like his tour of 1817 and subsequent month in Oxford, marked the next stage of Keats’s life. Brown would become a major figure, both friend and supporter to the poet.

In mid-July, Keats wrote a long letter to Bailey which should be noted since it contains the poet’s oft-quoted remarks about women. Keats had been dismissive of the fairer sex in an earlier letter, which upset Bailey; now he was reflective, seeking to understand his own contradictory feelings. His current reading of Burns and Dante had also affected him. And he understood his own character well enough to tell Bailey, “I carry all matters to an extreme.” Regarding women: “Is it not extraordinary? When among Men I have no evil thoughts, no malice, no spleen – I can listen and from every one I can learn – my hands are in my pockets I am free from all suspicion and comfortable. When I am among Women I have evil thoughts, malice, spleen – I cannot speak or be silent – I am full of Suspicions and therefore listen to no thing – I am in a hurry to be gone – You must be charitable and put all this perversity to my being disappointed since Boyhood – ….I must absolutely get over this, – but how? The only way is to find the root of the evil, and so cure it.” This attitude has been much discussed by biographers and critics, but seems understandable enough. As a shy young man with limited experience of women as well as a lingering defensiveness regarding his height (Keats was about five feet tall), his feelings were necessarily conflicted.

A few days after completing this letter, the rigors of the tour finally caught up with him. He caught a severe cold which turned into acute tonsillitis. He saw a doctor at Inverness on 6 August who advised him to return to London. Keats did so, and the ten day sale from Cromarty to London, with its enforced rest, restored some of his health. But bad news had arrived in Scotland for him. Tom’s doctor had asked the Dilkes to send for Keats; his brother’s condition was now dire. Brown wrote back that Keats was already on his way home. He arrived in London unaware and cheerful, meeting Severn in the city and then traveling back to Hampstead. His first stop was the Dilke household, where he made a great impression on Mrs. Dilke; Keats was “as brown and as shabby as you can imagine; scarcely any shoes left, his jacket all torn at the back, a fur cap, a great plaid, and his knapsack. I cannot tell you what he looked like.” They told him about Tom’s condition and he immediately left for Well Walk.

Nursing Tom was now his main task, but his own sore throat soon returned. Keats began to take larger doses of mercury under the advice of Tom’s doctor. They feared his ulcerated throat might turn out to be a syphilitic ulcer; doctors mistakenly believed there was a connection between gonorrhea and syphilis. The mercury had its own side effects, including nervousness, sore gums, and a bad toothache. Keats discontinued the medicine in late September. He spent several weeks in near seclusion, venturing to London once to ask Abbey to allow Fanny to visit Tom. When not brooding over his brother’s too brief life, he could consider the cruel reviews of Poems and Endymion which had appeared in the press.

The influential Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine had published a scathing criticism of the ‘Cockney School of Poetry’, into which they lumped both Hunt and Keats. Keats did not appreciate the link; his own development had taken him far from Hunt’s aesthetic. But he was not destroyed by the review, as later writers would imply. The review itself made numerous references to his humble middle-class origins and apothecary training. Blackwood’s would return to this snide characterization continuously. And it was all because of Bailey’s misguided loyalty. At a dinner party with John Lockhart of Blackwood’s, who published reviews under the anonymous ‘Z.’, Bailey heard Lockhart comment that Keats shared Hunt’s poetry and politics. In their long talks and letters, Keats had confessed his fear of exactly this criticism to Bailey, and now Bailey jumped to his friend’s defense. Attempting to distinguish the two men, he discussed Keats’s life, giving Lockhart ammunition for his attack. Realizing his blunder, Bailey asked Lockhart to keep the information to himself, which the critic did. After all, the review did not appear under his name. Blackwood’s review was by far the worst; other reviewers were content to simply discuss the poetry itself. It was of too new a type for immediate popularity, but some acknowledged Keats’s obvious talent, merely criticizing the path he had chosen. For Keats himself, the works reviewed had long since been abandoned in an aesthetic sense. They were the products of his youth, his idealistic experimentation, his first attempts at poetry; he had already left them behind. He was also leaving behind another part of his youth, the close companionship and support of his brothers. George was gone to America and Tom was dying. Keats could no longer define himself as an older brother and rely upon their encouragement. He would soon be completely alone. He would also compose some of the most beautiful poetry ever written.

As if Keats’s return home was not traumatic enough, with Tom’s illness and his own emotional and physical stress, another event occurred which had a profound impact upon the poet. He met Charles Brown’s former tenants, the Brawne family. Brown and the Dilke family each owned half of a double house in Hampstead called Wentworth Place. Brown rented out his half when he left on annual vacations, as he had with Keats that summer; when he returned, the Brawnes moved to Elm Cottage, a brief walk away. But while they had lived at Wentworth Place, they had become close friends with Keats’s friends, the kindly Dilke family. The Dilkes had spoken often of Keats, praising him in the highest terms. And so when the Brawne family finally met the esteemed young Mr Keats, they were prepared to like him.

Mrs Brawne was widowed; she lived with her 18 year old daughter Fanny, 14 year old son Sam and 9 year old daughter Margaret. The teenaged Fanny was not considered beautiful, but she was spirited and kind. She was also a realist and immensely practical, perhaps as a result of her family’s straitened circumstances. She took great care with her appearance and enjoyed flirting with young admirers. As Hampstead was close to an army barracks, there were numerous military dances throughout the year. Fanny was a popular participant; when they first met, Keats was struck by her coquettish sense of fun, and it later pricked his jealousy too often for comfort. My greatest torment since I have known you has been the fear of you being a little inclined to the Cressid,” he would tell her later, referring to Chaucer’s infamous flirt.

They met at the Dilkes’ home, as Fanny later recalled, and “[Keats’s] conversation was in the highest degree interesting and his spirits good, excepting at moments when anxiety regarding his brother’s health dejected them.” Indeed, Keats, whatever his first impressions of young Miss Brawne, was too caught up with his younger brother’s decline to ponder any attraction. By the end of November, with Tom close to death, Keats spent nearly every waking moment at Tom’s bedside. The little rooms at Well Walk, once the scene of close companionship for the brothers, were now haunted with disappointment, despair and grief. When Tom died on 1 December, Keats was worn and numb. The memories of Tom’s terrible, lingering illness would never leave him; Keats was too sensitive and brooding to ever forget them.

But he at least had a welcome distraction in Fanny Brawne . Eager to escape Well Walk, he gladly accepted Brown’s invitation to share Wentworth Place with him. This was not charity on Brown’s part; Keats paid him the normal rate for lodging. Since the Dilkes’ were now next door, Keats visited with more frequency; and each time, the brown-haired, blue-eyed Fanny made a greater impression. She both confused and exasperated Keats, and therein lay her attraction. He simply could not understand her. In mid-December, two weeks after Tom’s death, he wrote a long letter to George and Georgiana in America. Its contents spanned a fortnight and Fanny is notably mentioned: “Mrs Brawne who took Brown’s house for the summer still resides in Hampstead. She is a very nice woman and her daughter senior is I think beautiful, elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable and strange. We have a little tiff now and then – and she behaves a little better, or I must have sheered off.” And later the poet gives a more vivid description: “Shall I give you Miss Brawne? She is about my height with a fine style of countenance of the lengthened sort – she wants sentiment in every feature – she manages to make her hair look well – her nostrils are fine though a little painful – her mouth is bad and good – her Profile is better than her full-face which indeed is not full but pale and thin without showing any bone – her shape is very graceful and so are her movements – Her arms are good her hands badish – her feet tolerable…. She is not seventeen – but she is ignorant – monstrous in her behavior flying out in all directions, calling people such names that I was forced lately to make use of the term Minx – this I think not from any innate vice but from a penchant she has for acting stylishly. I am however tired of such style and shall decline any more of it.” And, for a time, it seems he did try to dismiss Fanny from his mind. She rates only a passing mention in a mid-February letter to George (he and Fanny have an occasional ‘chat and a tiff’). Poetry had once more become a consuming passion. But it would only be a matter of time before both Fanny and poetry occupied positions of equal importance in his life.

Fanny was no poet, nor did she aspire to the title. But as their acquaintance grew and deepened, she developed a keen appreciation and respect for Keats’s work. Whether she enjoyed it because it was written by the young man she loved, or because she recognized its greatness, we do not know; but her encouragement – and that of his friends – was welcome. (And it may be that Keats preferred Fanny’s decidedly non-poetic conversation. He had, after all, commented, “I have met with women who I really think would like to be married to a Poem and to be given away by a Novel.” If Fanny loved him, she loved him as John Keats alone and that won his gratitude.)

Throughout the winter of 1819, Keats worked for hours at his desk. In January, The Eve of St Agnes was completed and, a month later, The Eve of St Mark. He also worked on the ambitious Hyperion until early spring; he would leave it deliberately unfinished.

On 3 April 1819, he was suddenly forced into even closer quarters with the baffling Miss Brawne. The Dilkes decided to move to the city center and rented their half of Wentworth Place to Mrs Brawne and her children. Fanny was now a next door neighbor and her presence came close to intoxicating Keats. From April onward, their romance blossomed. Keats would interrupt his serious poetry to write quick sonnets to Fanny, including the famous Bright star ! would I were steadfast as thou art. Most of these works dwell upon her physical charms, but they also celebrate the enjoyment and abandon he found in her company. It was inevitable that his first love affair would consume him. Once he allowed love to take hold, Keats dedicated himself to it with his trademark intensity. In turn, he was given new impetus, – new inspiration, – new insight into his own emotions and the world itself. His poetry began to reflect this new maturity and power.

In late April, he began composing one of his best-loved works, La Belle Dame Sans Merci . The story of an enchantress and the knight she lures to his doom, it is an evocative and beautiful work, justly celebrated. But even it gives no hint of the great works to come; Keats himself considered it mere light verse and, in a letter to George, dismissed it with a joke. Then, in the space of a few weeks, he composed three of the most beautiful works of poetry ever written – Ode on a Grecian Urn , Ode to a Nightingale and Ode on Melancholy . The story of the composition of Ode to a Nightingale, as well as an image of Keats’s original draft, can be read at the Keats: Manuscripts page.

These works have been subject to much critical analysis, but the fact remains that – their technical merit aside – they are, quite simply, beautiful. They remain the ultimate expression of Keats’s genius and secured his reputation as a great poet. But this vindication of his early promise did not result in immediate acclaim. There was no fanfare, or even immediate publication. Instead, there were more long hours at work, stolen moments with Fanny, and Brown’s cheerful company. Mrs Brawne had by now realized the serious course of Keats and Fanny’s relationship; she could not have been very pleased. Keats was a kind and intelligent young man, but he was poor and his chosen career offered little hope of success. But her own good nature could not prevent a love match. She grew fond of the poet and later nursed him through his illness.