- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The empiricism of Francis Bacon

The materialism of thomas hobbes, the rationalism of descartes, the rationalism of spinoza and leibniz, reason in locke and berkeley, basic science of human nature in hume, materialism and scientific discovery, social and political philosophy, critical examination of reason in kant.

- The idealism of Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel

- Positivism and social theory in Comte, Mill, and Marx

- Independent and irrationalist movements

- What is ethics?

- How is ethics different from morality?

- Why does ethics matter?

- Is ethics a social science?

modern philosophy

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Table Of Contents

modern philosophy , in the history of Western philosophy , the philosophical speculation that occurred primarily in western Europe and North America from the 17th through the 19th century. The modern period is marked by the emergence of the broad schools of empiricism and rationalism and the epochal transformation of Western metaphysics , epistemology , and ethics by the German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), the greatest figure of the modern period.

The rise of empiricism and rationalism

Empiricism is the view that all concepts originate in experience, that all concepts are about or applicable to things that can be experienced, or that all rationally acceptable beliefs or propositions are justifiable or knowable only through experience. Rationalism, by contrast, is the doctrine that regards reason or the intellect as the primary or fundamental source and test of knowledge. Holding that reality itself has an inherently logical structure, rationalists assert the existence of a class of truths beyond the reach of sense perception and graspable directly by reason or the intellect. The rivalry between empiricism and rationalism dominated the philosophical controversies of the 17th and 18th centuries and was hardly resolved before the appearance of Immanuel Kant.

The English philosopher, scientist, and statesman Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was an outstanding apostle of empiricism in a time bordering the late-Renaissance and early-modern periods of philosophy . Less an original metaphysician or cosmologist than the advocate of a vast new program for the advancement of learning and the reformation of scientific method , Bacon conceived of philosophy as a new technique of reasoning that would reestablish natural science on a firm foundation. In the Advancement of Learning (1605), he charted the map of knowledge: history, which depends on the human faculty of memory; poetry, which depends on imagination; and philosophy, which depends on reason. To reason, however, Bacon assigned a completely experiential function. Fifteen years later, in his Novum Organum , he made this clear. Because, he said, “we have as yet no natural philosophy which is pure,…the true business of philosophy must be…to apply the understanding…to a fresh examination of particulars.” A technique for “the fresh examination of particulars” thus constituted his chief contribution to philosophy.

Bacon’s hope for a new birth of science depended not only on vastly more numerous and varied experiments but primarily on “an entirely different method, order, and process for advancing experience.” This method consisted of the construction of what he called “tables of discovery.” He distinguished three kinds: tables of presence, of absence, and of degree (i.e., in the case of any two properties, such as heat and friction, instances in which they appear together, instances in which one appears without the other, and instances in which their amounts vary proportionately). The ultimate purpose of these tables was to order facts in such a way that the true causes of phenomena (the subject of physics ) and the true “forms” of things (the subject of metaphysics , or the study of the nature of being ) could be inductively established.

Bacon’s empiricism was not raw or unsophisticated. His concept of fact and his belief in the primacy of observation led him to formulate laws and generalizations. Also, his conception of form was quite unlike that of Plato (427/28–347/48 bce ): a form for Bacon was not an essence but a permanent geometric or mechanical structure. His enduring place in the history of philosophy lies, however, in his single-minded advocacy of experience as the only source of valid knowledge and in his profound enthusiasm for the perfection of natural science. It is in this sense that “the Baconian spirit” was a source of inspiration for generations of later philosophers and scientists.

The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was acquainted with both Bacon and the Italian astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). With the first Hobbes shared a strong concern for philosophical method, with the second an overwhelming interest in matter in motion . His philosophical efforts, however, were more inclusive and more complete than those of his contemporaries. He was a comprehensive thinker within the scope of an exceedingly narrow set of presuppositions, and he produced one of the most systematic philosophies of the early modern period—an almost completely consistent description of humankind, civil society , and nature according to the tenets of mechanistic materialism .

Hobbes’s account of what philosophy is and ought to be clearly distinguished between content and method. As method, philosophy is simply reasoning or calculating by the use of words as to the causes or effects of phenomena. When people reason from causes to effects, they reason synthetically; when they reason from effects to causes, they reason analytically. (Hobbes’s strong inclination toward deduction and geometric proofs favoured arguments of the former type.) His dogmatic metaphysical assumption was that physical reality consists entirely of matter in motion. The real world is a corporeal universe in constant movement, and phenomena, or events, the causes and effects of which it is the business of philosophy to lay bare, consist of either the action of physical bodies on each other or the quaint effects of physical bodies upon minds.

From this assumption follows Hobbes’s classification of the fields that form the content of philosophy: (1) physics, (2) moral philosophy, and (3) civil philosophy. Physics is the science of the motions and actions of physical bodies conceived in terms of cause and effect . Moral philosophy (or, more accurately, psychology ) is the detailed study of “the passions and perturbations of the mind”—that is, how minds are “moved” by desire, aversion , appetite, fear, anger, and envy. And civil philosophy deals with the concerted actions of people in a commonwealth—how, in detail, the wayward wills of human beings can be constrained by power (i.e., force) to prevent civil disorder and maintain peace.

Hobbes’s philosophy was a bold restatement of Greek atomistic materialism, with applications to the realities of early modern politics that would have seemed strange to its ancient authors. But there are also elements in it that make it characteristically English. Hobbes’s account of language led him to adopt nominalism and to deny the reality of abstract universals (i.e., a metaphysical entity used to explain what it is for things to share a feature, attribute, or quality or to fall under the same type or natural kind). Bacon’s general emphasis on experience also had its analogue in Hobbes’s theory that all knowledge arises from sense experiences, all of which are caused by the actions of physical bodies on the sense organs. Empiricism has long been a basic and recurrent feature of British intellectual life, and its nominalist and sensationalist roots were already clearly evident in both Bacon and Hobbes.

The dominant philosophy of the last half of the 17th century was that of René Descartes (1596–1650). A crucial figure in the history of philosophy, Descartes combined (however unconsciously or even unwillingly) the influences of the past into a synthesis that was striking in its originality and yet congenial to the scientific temper of the age. In the minds of all later historians, he counts as the progenitor of the modern spirit of philosophy. Descartes was also a great mathematician—he invented analytic geometry —and the author of many important physical and anatomical experiments. He knew and profoundly respected the work of Galileo; indeed, he withdrew from publication his own cosmological treatise , The World , after Galileo’s condemnation by the Inquisition in 1633.

Bacon and Descartes, the founders of modern empiricism and rationalism, respectively, both subscribed to two pervasive tenets of the Renaissance: an enormous enthusiasm for physical science and the belief that knowledge means power—that the ultimate purpose of theoretical science is to serve the practical needs of human beings.

In his Principles of Philosophy (1644), Descartes defined philosophy as “the study of wisdom” or “the perfect knowledge of all one can know.” Its chief utility is “for the conduct of life” (morals), “the conservation of health” (medicine), and “the invention of all the arts” (mechanics). He expressed the relation of philosophy to practical endeavours in the famous metaphor of the “tree”: the roots are metaphysics, the trunk is physics, and the branches are morals , medicine, and mechanics. The metaphor is revealing, for it indicates that for Descartes—as for Bacon and Galileo—the most important part of the tree was the trunk. In other words, Descartes busied himself with metaphysics only in order to provide a firm foundation for physics. Thus, the Discourse on Method (1637), which provides a synoptic view of the Cartesian philosophy, shows it to be not a metaphysics founded upon physics—as was the case with Aristotle (384–322 bce )— but rather a physics founded upon metaphysics.

Descartes’s mathematical bias was reflected in his determination to ground natural science not in sensation and probability (as did Bacon) but in premises that could be known with absolute certainty. Thus his metaphysics in essence consisted of three principles:

- To employ the procedure of complete and systematic doubt to eliminate every belief that does not pass the test of indubitability ( skepticism ).

- To accept no idea as certain that is not clear, distinct, and free of contradiction (mathematicism).

- To found all knowledge upon the bedrock certainty of self-consciousness, so that the cogito ( cogito, ergo sum ; “I think, therefore I am,” or “I think, I am”) becomes the only innate idea unshakable by doubt (subjectivism).

From the indubitability of the self, Descartes inferred the existence of a perfect God, and, from the fact that a perfect being is incapable of falsification or deception, he concluded that the ideas about the physical world that God has implanted in human beings must be true. The achievement of certainty about the natural world was thus guaranteed by the perfection of God and by the “clear and distinct” ideas that are his gift.

Cartesian metaphysics is the fountainhead of rationalism in modern philosophy, for it suggests that the mathematical criteria of clarity, distinctness, and logical consistency are the ultimate test of meaningfulness and truth. This stance is profoundly antiempirical. Bacon, who remarked that “reasoners resemble spiders who make cobwebs out of their own substance,” might well have said the same of Descartes, for the Cartesian self is just such a substance. Yet for Descartes the understanding is vastly superior to the senses, and only reason can ultimately decide what constitutes truth in science.

Cartesianism dominated the intellectual life of continental Europe until the end of the 17th century. It was a fashionable philosophy, appealing to learned gentlemen and highborn ladies alike, and it was one of the few philosophical alternatives to the Scholasticism still being taught in the universities. Precisely for this reason it constituted a serious threat to established religious authority . In 1663 the Roman Catholic Church placed Descartes’s works on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (“Index of Forbidden Books”), and the University of Oxford forbade the teaching of his doctrines. Only in the liberal Dutch universities, such as those of Groningen and Utrecht, did Cartesianism make serious headway.

Certain features of Cartesian philosophy made it an important starting point for subsequent philosophical speculation. As a kind of meeting point for medieval and modern worldviews, it accepted the doctrines of Renaissance science while attempting to ground them metaphysically in medieval notions of God and the human mind. Thus, a certain dualism between God the Creator and the mechanistic world of his creation, between mind as a spiritual principle and matter as mere spatial extension, was inherent in the Cartesian position. An entire generation of Cartesians—among them Arnold Geulincx (1624–69), Nicolas Malebranche (1638–1715), and Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) —wrestled with the resulting problem of how interaction between two such radically different entities is possible.

The tradition of Continental rationalism was carried on by two philosophers of genius: the Dutch Jewish philosopher Benedict de Spinoza (1632–77) and his younger contemporary Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), a Leipzig scholar and polymath. Whereas Bacon’s philosophy had been a search for method in science and Descartes’s basic aim had been the achievement of scientific certainty, Spinoza’s speculative system was one of the most comprehensive of the early modern period. In certain respects Spinoza had much in common with Hobbes: a mechanistic worldview and even a political philosophy that sought political stability in centralized power. Yet Spinoza introduced a conception of philosophizing that was new to the Renaissance; philosophy became a personal and moral quest for wisdom and the achievement of human perfection.

Spinoza’s magnum opus, the Ethics (1677), borrowed much from Descartes: the goal of a rational understanding of principles, the terminology of “substance” and “clear and distinct ideas,” and the expression of philosophical knowledge in a complete deductive system using the geometric model of the Elements of Euclid (flourished c. 300 bce ). Spinoza conceived of the universe pantheistically as a single infinite substance, which he called “God,” with the dual attributes (or aspects) of thought and extension ( see pantheism ). Extension is differentiated into plural “modes,” or particular things, and the world as a whole possesses the properties of a timeless logical system—a complex of completely determined causes and effects. For Spinoza, the wisdom that philosophy seeks is ultimately achieved when one perceives the universe in its wholeness through the “intellectual love of God,” which merges the finite individual with eternal unity and provides the mind with the pure joy that is the final achievement of its search.

Whereas the basic elements of the Spinozistic worldview are given in the Ethics , Leibniz’s philosophy must be pieced together from numerous brief expositions, which seem to be mere philosophical interludes in an otherwise busy life. But the philosophical form is deceptive. Leibniz was a mathematician (he and Isaac Newton independently invented the infinitesimal calculus ), a jurist (he codified the laws of Mainz ), a diplomat, a historian to royalty, and a court librarian in a princely house. Yet he was also one of the most original philosophers of the early modern period. His chief contributions were in the fields of logic , in which he was a truly brilliant innovator, and metaphysics, in which he provided a rationalist alternative to the philosophies of Descartes and Spinoza.

Leibniz conceived of logic as a mathematical calculus. He was the first to distinguish “truths of reason” from “truths of fact” and to contrast the necessary propositions of logic and mathematics, which hold in all “possible worlds,” with the contingent propositions of science, which hold only in some possible worlds (including the actual world). He saw clearly that, as the first kind of proposition is governed by the principle of contradiction (a proposition and its negation cannot both be true), the second is governed by the principle of sufficient reason (nothing exists or is the case without a sufficient reason).

In metaphysics, Leibniz’s pluralism contrasted with Descartes’s dualism and Spinoza’s monism ( see pluralism and monism ). Leibniz posited the existence of an infinite number of spiritual substances, which he called “ monads ,” each different, each a percipient of the universe around it, and each mirroring that universe from its own point of view. However, the differences between Leibniz’s philosophy and that of Descartes and Spinoza are less significant than their similarities, in particular their extreme rationalism. In the Principes de la nature et de la grâce fondés en raison (1714; “Principles of Nature and of Grace Founded in Reason”), Leibniz stated a maxim that could fairly represent the entire school:

True reasoning depends upon necessary or eternal truths, such as those of logic, numbers, geometry, which establish an indubitable connection of ideas and unfailing consequences.

The Enlightenment

Although they both lived and worked in the late 17th century, Isaac Newton and John Locke (1632–1704) were the true fathers of the Enlightenment . Newton was the last of the scientific geniuses of the age, and his great Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687; Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy ) was the culmination of the movement that had begun with Copernicus and Galileo—the first scientific synthesis based on the application of mathematics to nature in every detail. The basic idea of the authority and autonomy of reason, which dominated all philosophizing in the 18th century, was, at bottom, the consequence of Newton’s work.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), Bacon, Galileo, and Descartes—scientists and methodologists of science—performed like people urgently attempting to persuade nature to reveal its secrets. Newton’s comprehensive mechanistic system made it seem as if at last nature had done so. It is impossible to exaggerate the enormous enthusiasm that this assumption kindled in all of the major thinkers of the late 17th and 18th centuries, from Locke to Kant. The new enthusiasm for reason that they all instinctively shared was based not upon the mere advocacy of philosophers such as Descartes and Leibniz but upon their conviction that, in the spectacular achievement of Newton, reason had succeeded in conquering the natural world.

Classical British empiricism

Two major philosophical problems remained: to provide an account of the origins of reason and to shift its application from the physical universe to human nature . Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) was devoted to the first, and Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40), “being an attempt to apply the method of experimental reasoning to moral subjects,” was devoted to the second.

These two basic tasks represented a new direction for philosophy since the late Renaissance. The Renaissance preoccupation with the natural world had constituted a certain “realistic” bias. Hobbes and Spinoza had each produced a metaphysics. They had been interested in the real constitution of the physical world. Moreover, the Renaissance enthusiasm for mathematics had resulted in a profound interest in rational principles, necessary propositions, and innate ideas. As attention was turned from the realities of nature to the structure of the mind that knows it so successfully, philosophers of the Enlightenment focused on the sensory and experiential components of knowledge rather than on the merely mathematical. Thus, whereas the philosophy of the late Renaissance had been metaphysical and rationalistic, that of the Enlightenment was epistemological and empiricist. The school of British empiricism—John Locke, George Berkeley (1685–1753), and David Hume (1711–76)—dominated the perspective of Enlightenment philosophy until the time of Kant.

Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding marked a decisively new direction for modern philosophizing because it proposed what amounts to a new criterion of truth. Locke’s aim in his essay—“to inquire into the origin, certainty, and extent of human knowledge”—involved three tasks:

- To discover the origin of human ideas.

- To determine their certainty and evidential value.

- To examine the claims of all knowledge that is less than certain.

What was crucial for Locke, however, was that the second task is dependent upon the first. Following the general Renaissance custom, Locke defined an idea as a mental entity: “whatever is the object of the understanding when a man thinks.” But whereas for Descartes and the entire rationalist school the certainty of ideas had been a function of their self-evidence—i.e., of their clarity and distinctness—for Locke their validity depended expressly on the mode and manner of their origin. Thus, an intrinsic criterion of truth and validity was replaced with a genetic one.

Locke’s exhaustive survey of mental contents is useful, if elaborate. Although he distinguished between ideas of sensation and ideas of reflection, the thrust of his efforts and those of his empiricist followers was to reduce the latter to the former, to minimize the originative power of the mind in favour of its passive receptivity to the sensory impressions received from without. Locke’s classification of ideas into “simple” and “complex” was an attempt to distinguish mental contents that are derived directly from one or more of the senses (such as blueness or solidity, which come from a single sense such as sight or touch, and figure, space, extension, rest, and motion, which are the product of several senses combined) from complicated and compounded ideas of universals (such as triangle and gratitude), substances, and relations (such as identity, diversity , and cause and effect).

Locke’s Essay was a dogged attempt to produce the total world of human conceptual experience from a set of elementary sensory building blocks, moving always from sensation toward thought and from the simple to the complex. The basic outcome of his epistemology was therefore:

- That the ultimate source of human ideas is sense experience.

- That all mental operations are a combining and compounding of simple sensory materials into complex conceptual entities.

Locke’s theory of knowledge was based upon a kind of sensory atomism , in which the mind is an agent of discovery rather than of creation, and ideas are “like” the objects they represent, which in turn are the sources of the sensations the mind receives. Locke’s theory also made the important distinction between “primary qualities” (such as solidity, figure, extension, motion, and rest), which are real properties of physical objects, and “secondary qualities” (such as colour, taste, and smell), which are merely the effects of such real properties on the mind.

It was precisely this dualism of primary and secondary qualities that Locke’s successor , George Berkeley, sought to overcome. Although Berkeley was a bishop in the Anglican church who professed a desire to combat atheistic materialism, his importance for the theory of knowledge lies rather in the way in which he demonstrated that, in the end, primary qualities are reducible to secondary qualities. His empiricism led to a denial of abstract ideas because he believed that general notions are simply fictions of the mind. Science, he argued, can easily dispense with the concept of matter: nature is simply that which human beings perceive through their sense faculties. This means that sense experiences themselves can be considered “objects for the mind.” A physical object, therefore, is simply a recurrent group of sense qualities. With this important reduction of substance to quality, Berkeley became the father of the epistemological position known as phenomenalism , which has remained an important influence in British philosophy to the present day.

The third, and in many ways the most important, of the British empiricists was the skeptic David Hume. Hume’s philosophical intention was to reap, humanistically, the harvest sowed by Newtonian physics, to apply the method of natural science to human nature. The paradoxical result of this admirable goal, however, was a devastating skeptical crisis.

Hume followed Locke and Berkeley in approaching the problem of knowledge from a psychological perspective. He too found the origin of knowledge in sense experience. But whereas Locke had found a certain trustworthy order in the compounding power of the mind, and Berkeley had found mentality itself expressive of a certain spiritual power, Hume’s relentless analysis discovered as much contingency in mind as in the external world. All uniformity in perceptual experience, he held, comes from “an associating quality of the mind.” The “association of ideas” is a fact, but the relations of resemblance, contiguity, and cause and effect that it produces have no intrinsic validity because they are merely the product of “mental habit.” Thus, the causal principle upon which all knowledge rests represents no necessary connections between things but is simply the result of their constant conjunction in human minds. Moreover, the mind itself, far from being an independent power, is simply “a bundle of perceptions” without unity or cohesive quality. Hume’s denial of a necessary order of nature on the one hand and of a substantial or unified self on the other precipitated a philosophical crisis from which Enlightenment philosophy was not to be rescued until the work of Kant.

Nonepistemological movements in the Enlightenment

Although the school of British empiricism represented the mainstream of Enlightenment philosophy until the time of Kant, it was by no means the only type of philosophy that the 18th century produced. The Enlightenment, which was based upon a few great fundamental ideas—such as the dedication to reason, the belief in intellectual progress, the confidence in nature as a source of inspiration and value , and the search for tolerance and freedom in political and social institutions—generated many crosscurrents of intellectual and philosophical expression.

The profound influence of Locke spread to France , where it not only resulted in the skeptical empiricism of Voltaire (1694–1778) but also united with mechanistic aspects of Cartesianism to produce an entire school of sensationalistic materialism. Representative works included Man a Machine (1747) by Julien Offroy de La Mettrie (1709–51), Treatise on the Sensations (1754) by Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1715–80), and The System of Nature (1770) by Paul-Henri Dietrich, baron d’Holbach (1723–89). This position even found its way into many of the articles of the great French Encyclopédie , edited by Denis Diderot (1713–84) and Jean d’Alembert (1717–83), which was almost a complete compendium of the scientific and humanistic accomplishments of the 18th century.

Although the terms Middle Ages and Renaissance were not invented until well after the historical periods they designate , scholars of the 18th century called their age “the Enlightenment” with self-conscious enthusiasm and pride. It was an age of optimism and expectations of new beginnings. Great strides were made in chemistry and biological science. Jean-Baptiste de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1744–1829), Georges, Baron Cuvier (1769–1832), and Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon (1707–88), introduced a new system of animal classification. In the eight years between 1766 and 1774, three chemical elements—hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen—were discovered. Foundations were being laid in psychology and the social sciences and in ethics and aesthetics . The work of Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, baron de L’Aulne (1727–81), and Montesquieu (1689–1755) in France, Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) in Italy, and Adam Smith (1723–90) in Scotland marked the beginning of economics, politics, history, sociology, and jurisprudence as sciences. Hume, the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), and the British “moral sense” theorists were turning ethics into a specialized field of philosophical inquiry. And Anthony Ashley, 3rd earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713), Edmund Burke (1729–97), Johann Gottsched (1700–66), and Alexander Baumgarten (1714–62) were laying the foundations for a systematic aesthetics .

Apart from epistemology, the most significant philosophical contributions of the Enlightenment were made in the fields of social and political philosophy . The Two Treatises of Civil Government (1690) by Locke and The Social Contract (1762) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) proposed justifications of political association grounded in the newer political requirements of the age. The Renaissance and early modern political philosophies of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), Jean Bodin (1530–96), and Hobbes had presupposed or defended the absolute power of kings and rulers. But the Enlightenment theories of Locke and Rousseau championed the freedom and equality of citizens. It was a natural historical transformation. The 16th and 17th centuries were the age of absolutism ; the chief problem of politics was that of maintaining internal order, and political theory was conducted in the language of national sovereignty . But the 18th century was the age of the democratic revolutions; the chief political problem was that of securing freedom and revolting against injustice, and political theory was expressed in the idiom of natural and inalienable rights.

Locke’s political philosophy explicitly denied the divine right of kings and the absolute power of the sovereign . Instead, he insisted on a natural and universal right to freedom and equality. The state of nature in which human beings originally lived was not, as Hobbes imagined, intolerable, though it did have certain inconveniences. Therefore, people banded together to form society—as Aristotle taught, “not simply to live, but to live well.” Political power, Locke argued, can never be exercised apart from its ultimate purpose, which is the common good , for the political contract is undertaken in order to preserve life, liberty, and property .

Locke thus stated one of the fundamental principles of political liberalism : that there can be no subjection to power without consent—though once political society has been founded, citizens are obligated to accept the decisions of a majority of their number. Such decisions are made on behalf of the majority by the legislature, though the ultimate power of choosing the legislature rests with the people; and even the powers of the legislature are not absolute, because the law of nature remains as a permanent standard and as a principle of protection against arbitrary authority.

Rousseau’s more radical political doctrines were built upon Lockean foundations. For him, too, the convention of the social contract formed the basis of all legitimate political authority, though his conception of citizenship was much more organic and much less individualistic than Locke’s. The surrender of natural liberty for civil liberty means that all individual rights (among them property rights) become subordinate to the general will . For Rousseau the state is a moral person whose life is the union of its members, whose laws are acts of the general will, and whose end is the liberty and equality of its citizens. It follows that when any government usurps the power of the people, the social contract is broken; and not only are the citizens no longer compelled to obey, but they also have an obligation to rebel. Rousseau’s defiant collectivism was clearly a revolt against Locke’s systematic individualism ; for Rousseau the fundamental category was not “natural person” but “citizen.” Nevertheless, however much they differed, in these two social theorists of the Enlightenment is to be found the germ of all modern liberalism: its faith in representative democracy , in civil liberties, and in the basic dignity of human beings.

All these developments led directly to the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, whose works mark the true culmination of the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Historically speaking, Kant’s great contribution was to elucidate both the sensory and the a priori elements in knowledge and thus to bridge the gap between the extreme rationalism of Leibniz and the extreme empiricism of Hume. But in addition to the brilliant content of his philosophical doctrines, Kant was responsible for three crucial philosophical innovations: (1) a new definition of philosophy, (2) a new conception of philosophical method, and (3) a new structural model for the writing of philosophy.

Kant conceived of reason as being at the very heart of the philosophical enterprise. Philosophy’s sole task, in his view, is to determine what reason can and cannot do. Philosophy, he said, “is the science of the relation of all knowledge to the essential ends of human reason”; its true aim is both constructive (“to outline the system of all knowledge arising from pure reason”) and critical (“to expose the illusions of a reason that forgets its limits”). Philosophy is thus a calling of great dignity, for its aim is wisdom, and its practitioners are themselves “lawgivers of reason.” But in order for philosophy to be “the science of the highest maxims of reason,” the philosopher must be able to determine the source, the extent, and the validity of human knowledge and the ultimate limits of reason. And these tasks require a special philosophical method.

Sometimes Kant called this the “transcendental method,” but more often the “critical method.” His purpose was to reject the dogmatic assumptions of the rationalist school, and his wish was to return to the semiskeptical position with which Descartes had begun before his dogmatic pretensions to certainty took hold. Kant’s method was to conduct a critical examination of the powers of a priori reason—an inquiry into what reason can achieve when all experience is removed. His method was based on a doctrine that he himself called “a Copernican revolution” in philosophy (by analogy with the shift from geocentrism to heliocentrism in cosmology ): the assumption that objects must conform to human knowledge—or to the human apparatus of knowing—rather than that human knowledge must conform to objects. The question then became: What is the exact nature of this knowing apparatus?

Unlike Descartes, Kant could not question that knowledge exists. No one raised in the Enlightenment could doubt, for example, that mathematics and Newtonian physics were real. Kant’s methodological question was rather: How is mathematical and physical knowledge possible? How must human knowledge be structured in order to make these sciences secure? The attempt to answer these questions was the task of Kant’s great work Critique of Pure Reason (1781).

Kant’s aim was to examine reason not merely in one of its domains but in each of its employments according to the threefold structure of the human mind. Thus the critical examination of reason in thinking (science) is undertaken in the Critique of Pure Reason , that of reason in willing ( ethics ) in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and that of reason in feeling ( aesthetics ) in the Critique of Judgment (1790).

The Importance of Modern Philosophy

What is modern philosophy? What are the benefits of reading about it? What are the main contributions of philosophers such as Descartes, Leibniz, Hume, and Locke? What can it teach us about our own lives? How does it relate to our values? What are the challenges and possibilities of our modern world? The answers to these questions are all interconnected. Modern philosophy can help us see the common ground between different world views and foster ecumenical discourse.

René Descartes was a French philosopher, mathematician, and lay Catholic who paved the way for modern philosophy. He was a mathematician and inventor and invented the analytic geometry that unified algebra and geometry. His work had a lasting impact on philosophy and science, and it has continued to influence the way we understand the world today. Learn about the philosopher’s legacy in this article.

Philosophers have long tended to view man as an immaterial fragment of the universe, and in Descartes’ time, he broke this connection. His work established the metaphysical foundation of this dualistic view, which states that the soul exists separately from the body. The soul is an immaterial, immortal being, and is therefore separate from the rest of the physical universe. This idea was revolutionary in the 18th century, and it has influenced many philosophers and scientists ever since.

The central chapter of Leibniz and modern philosophy concerns the tension between the nature of things and the mind, which is essential to cognition. Leibniz seeks to reconcile the nature of things and the mind, and to do so he develops a concept called the conatus. Hence, Leibniz’s project is to create a new system of knowledge. This system of knowledge is the foundation of modern philosophy.

Although Leibniz developed a rigorous system of logic based on a mechanical natural philosophy, it also strove to create a metaphysical foundation for the natural. His doctrine of dispositional ideas can only be understood against this background. His lifelong struggle with the doctrine of absolute power was not confined to his philosophical works. The emergence of modern science and philosophy has made the role of mathematics and logic more important than ever.

David Hume was a British philosopher who studied the same subjects as Descartes and Mersenne a century earlier. He also read continental authors such as Malebranche, Dubos, and Bayle, and occasionally baited Jesuits with iconoclastic arguments. Hume’s later works, like his Four Dissertations, are considered the foundations of modern philosophy. But what exactly is Hume’s contribution to modern philosophy ?

David Hume introduces the concept of belief in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. For example, when we see a glass falling, we believe that the glass will break, not that we expect it to. When we see wet ground, we think of rain. Hume investigates the nature of belief and the way we associate ideas with past events. He argues that we associate ideas with the past without realizing it, and that this process of associating ideas with the past is the basis for all of our beliefs.

Whether we agree or disagree with Locke’s view of the mind is a question that we must answer. Locke defines an idea as the object of a man’s understanding. This notion can be any kind of mental object. Locke also explores the role of relations in thinking. Whether we think of things as things or as relations, they all involve the role of relational thinking. Locke argues that a man’s ideas are formed by relations between objects and people.

The essay is divided into three parts, Book I, Book II, and Book III. Book II focuses on the nature of nature and how human beings are related to it. Book III explores the proper role of language and its misuse. A majority of Book III is devoted to combating the misuse of language. Locke argues that improper use of language blocks knowledge and offers recommendations to avoid this problem. Throughout his Essay, Locke makes the distinction between natural rights and the rights of property.

Postanalytic philosophy

In the past, philosophers have appealed to the idea of non-existent objects to prove their claims about reality. Such claims have, however, been rejected by the linguistic turn, which sought a different account of necessity and a priori. This new account incorporated the idea of possible worlds. However, it is not clear what this new approach means in terms of defining the nature of reality.

The term “analytic philosophy” has its origins in the papers of Charles Moore. Moore understood “analysis” as rephrasing ordinary common sense propositions to provide more insight into the meaning. This was one of the goals of Moore’s paper, Proof of the External World. This approach is often associated with linguistic philosophy, but it has also influenced postmodern philosophy . The following list is a brief discussion of the most important works in the field.

Church-Turing thesis

While a number of arguments exist for the validity of Church-Turing’s thesis, its most notable flaw is its failure to account for the negative aspects of the theory. The Church-Turing thesis suggests that certain problems cannot be solved through computation or human thought. While it is true that certain answers exist, no one has been able to find them. It’s therefore impossible for a machine to answer all questions, as it can’t be a human being.

The Church-Turing thesis proposes that human thought is equivalent to “calculable by LCM.” While this is an alternative definition, Church’s thesis was not accepted until the 1940s. This is because Church and Turing were talking about effective methods, not finitely realizable physical systems. Regardless of the difference between the two these theses are not in agreement, and it’s possible that Church’s thesis is more compelling.

Hume’s critique of Locke

One of the central problems in Locke’s critique of Hume is his insistence that morality is not based on empirical facts. Hume believes that morality is based on our feelings and sentiments. Therefore, he is unable to accept the claim that morality is based on empirical facts. This is in direct opposition to Locke’s views, which claim that morality is based on a single, ultimate principle.

In the mid-seventeenth century, Hume entered the British Moralists debate, which lasted until the eighteenth century. Hume makes clear that reason does not oppose a passion, but only opposes another motive. Thus, the idea of a rationally perfect person is false. This means that reason is a slave to its passions and cannot protect our interests.

Kant’s critique of Leibniz

In his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant argued that we can only know the bare particulars of empirical objects. This conclusion reflects a fundamental difference between Kant and Leibniz. The latter believed that the objects that we perceive can be counted only as their appearances. On the other hand, Kant held that we cannot know much of anything without experiencing it first.

The Auseinandersetzung between Kant and Leibniz is a crucial philosophical story with implications for metaphysics, a branch of philosophy concerned with fundamental questions, causal connections, and the way the mind latches on to the world. The Auseinandersetzung with Leibniz also highlights Kant’s concern with a metaphysical universe that is prone to eternal recurrence.

Hume’s critique of Leibniz

David Hume was a thoroughgoing empiricist and the last of the three major British empiricists in the eighteenth century. Hume was of the opinion that experience and observation are the most reliable foundations for logical arguments. He anticipated the Logical Positivist movement by almost two centuries, and he sought to show that ordinary propositions about objects, causal relations, and the self can be proven without any further proof.

The logical consequences of Hume’s critique of Leibnius’s theory of causes are numerous. For one thing, the theory of causality is unjustifiable by the rules of natural deduction. But this doesn’t mean that it is impossible to establish a cause from an effect. While there is no evidence for a miracle in history, Hume’s critique of Leibniz’s axioms has profound implications for modern philosophy.

Similar Posts

Does Socrates Believe in God?

Does Socrates believe in God? This article examines the philosopher’s beliefs about new gods, his trial, and Meletus’s claim that he is guided by a divine being. Ultimately, we will come to an understanding of the questions, beliefs, and philosophy of Socrates. Socrates, a middle-class Greek philosopher, was the most influential philosopher in the Western…

Philosophy in Education

Philosophy in education is an interdisciplinary branch of philosophy that explores the nature of educational institutions, the goals of education, and the problems that educators face. It includes the analysis of educational theories and presuppositions and the arguments for and against each. A well-trained philosopher is an important asset in the field of education. This…

The Basis of Morality According to Kant

The basis of morality, according to Kant, rests on the categorical imperative. It holds that moral reasons are always superior to all other sorts of reasons, including self-interest. Therefore, we must act on moral grounds despite all other factors, including the inclinations of our will. This article will examine these issues. By the time you…

Nietzsche and Camus

Nihilism is a philosophical position that rejects all aspects of human existence, including objective truth, knowledge, values, and meaning. The term ‘nihilist’ is sometimes used interchangeably with the philosophical position of an atheist. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the philosophy is up to individual interpretation. In this article, we will explore the philosophies of…

Types of Philosophy

There are various types of philosophy. Some are considered major branches of philosophy. Other types include Rationalism, Empiricism, Cumulative arguments, and more. This article will explore the major-minor branches of philosophy. There are many subtypes as well, and this article will cover some of the most common. We’ll also look at the various philosophical schools…

What Was Socrates Most Famous Philosophy?

What was Socrates’ most famous philosophy? That is a question many philosophers ask. This article explores some of the key aspects of Plato’s philosophy, as well as the story of Socrates. If you’re interested in understanding Socrates and Plato’s philosophy in general, this article will help you understand the philosopher’s methods. Afterward, we’ll examine Xenophon’s…

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Why Is Philosophy Important Today, and How Can It Improve Your Life?

From clarity to tolerance: here’s your quick guide to why philosophy is important today, as well as how it can improve your life.

7 MIN BREAK

P hilosophy essentially involves thinking hard about life’s big questions , including — as we discuss in our article on what philosophy is, how it works, as well as its four core branches — why we are here, how we can know anything about the world, and what our lives are for.

Here at Philosophy Break, we believe the practice of philosophy is the antidote to a world saturated by information, and the more that people engage with philosophy, the more fulfilling their lives will be.

The addictive nature of the digital world, for instance, afflicts many of us. The relentless torrent of information saturates our attention spans. But life is finite, and the things we give attention to define our lives. It’s crucial to break free from the turbulent current and come up for air.

As Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca put it almost 2,000 years ago in his brilliant treatise, On the Shortness of Life :

It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it. Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested. But when it is wasted in heedless luxury and spent on no good activity, we are forced at last by death’s final constraint to realize that it has passed away before we knew it was passing. So it is: we are not given a short life but we make it short, and we are not ill-supplied but wasteful of it… Life is long if you know how to use it.

Streaming services hook us into one more episode, those of us with smartphones check them without thinking; but the compulsion to watch, to shop, to hit refresh on our newsfeeds — all of it can be reined in by contemplating the world around us, and our place within it.

How can we best spend our lives on earth? What makes you happy? What gives you purpose?

A lot of the anxieties and uncertainties we feel in our lives, from wondering if our occupations give us the meaning we need, to not being able to come to terms with death, are at root philosophical problems. And philosophers have confronted and had hugely insightful things to say about these problems for thousands of years.

Critically engaging with the enduring wisdom of philosophy is a fantastic way to both inform ourselves about the problems inherent within the human condition, and also face up to those problems and calm our existential fears and anxieties.

By engaging with the ideas of great thinkers throughout history, we’re empowered to think for ourselves — be it on matters of meaning and existence, how to make a better world, or simply working out what’s worth pursuing in life.

For as Socrates , the famous ancient Greek martyr of philosophy , declared:

The unexamined life is not worth living.

Philosophical contemplation is the starting gun that jolts us out of going through life as if we’re only going through the motions, living only according to the expectations of others, or living by norms we’ve never really thought about, let alone endorsed.

Philosophy opens our eyes to the multitudinous ways we can spend our lives, engendering tolerance for those whose practices differ from our own, and reawakening a childlike wonder and appreciation for the sheer mystery and opportunity lying at the heart of existence.

Why is philosophy important today?

P hilosophy is sometimes considered outdated — a perception not helped by the subject’s apparent obsession with reaching back over thousands of years to consider the works of ancient figures like Socrates , Plato , Aristotle , and Confucius .

But the point of philosophy in modern times remains the point philosophy has always had: to answer the fundamental questions that lie at the heart of the human condition.

Philosophy plays a crucial role in this regard not just in personal study and exploration, but formally in academia and modern research projects. And, even as time mercilessly advances, it turns out ancient figures whose works have survived over millennia still have some of the most interesting things to say about our human predicament, making their wisdom worth republishing and studying generation after generation.

Now, it might be thought that some of the questions philosophy touches on, such as the basic nature of the universe , or the emergence of consciousness , have been superseded by more specialist scientific subjects.

For example, physicists are at the forefront of investigating the fundamental nature of reality. Likewise, neuroscientists are leading the way in unlocking the secrets of the brain.

But philosophy is not here to compete with these brilliant, fascinating research projects, but to supplement, clarify, and even unify them.

For instance, when physicists share their latest mathematical models that predict the behavior of matter, philosophers ask, “okay, so what does this behavior tell us about the intrinsic nature of matter itself? What is matter? Is it physical, is it a manifestation of consciousness? — and why does any of this stuff exist in the first place?”

Equally, when neuroscientists make progress in mapping the brain, philosophers are on hand to digest the consequences the latest research has for our conceptions of consciousness and free will .

And, just as pertinently, while computer scientists continue to advance the sophistication of AI, philosophers discuss the implications an ever-growing machine intelligence has for society , and dissect the urgent ethical and moral concerns accompanying them.

With its focus on argument and clarity, philosophy is particularly good at rooting out the assumptions and contradictions that lie at the core of commonsensical thinking, sharpening our insight into truth, and lending security to the foundations of knowledge in all areas of research — especially the sciences, operating as they do at the frontiers of what we know.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

T he practice of philosophical reflection is not just important for progressing research, however: it is crucial for successfully navigating a world in which competing responsibilities, information, and forces pull us in various directions.

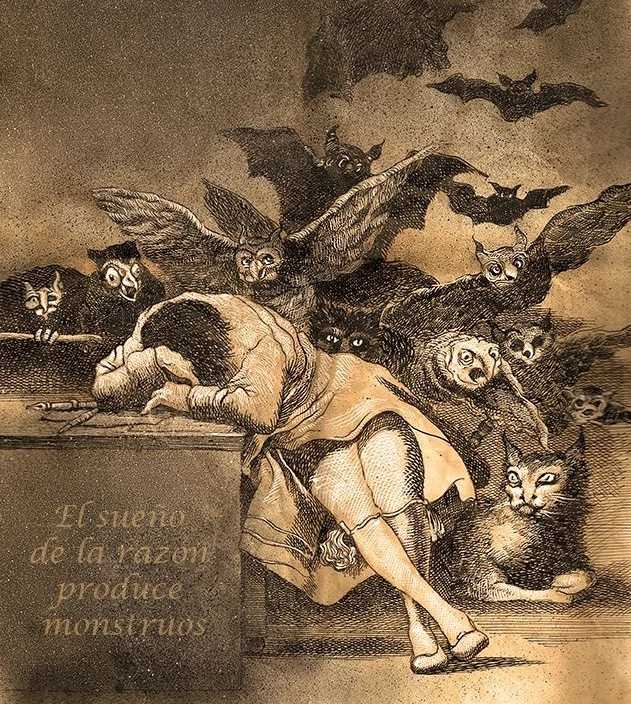

This is exactly what the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya understood when he produced his famous etching, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters , depicted below.

In his analysis of Goya’s etching, contemporary philosopher Simon Blackburn notes in his book Think that “there are always people telling us what we want, how they will provide it, and what we should believe”, forcefully continuing:

Convictions are infectious, and people can make others convinced of almost anything. We are typically ready to believe that our ways, our beliefs, our religions, our politics are better than theirs, or that our God-given rights trump theirs or that our interests require defensive or pre-emptive strikes against them. In the end, it is ideas for which people kill each other. It is because of ideas about what the others are like, or who we are, or what our interests or rights require, that we go to war, or oppress others with a good conscience, or even sometimes acquiesce in our own oppression by others.

With so much at stake, sleeps of reason must be countered to stop the dangerous spread of misinformation. Blackburn recommends philosophical awakening as the antidote:

Reflection enables us to step back, to see our perspective on a situation as perhaps distorted or blind, at the very least to see if there is argument for preferring our ways, or whether it is just subjective.

By deploying critical thinking and the rigor of philosophy, we are less likely to be duped or led by those who — intentionally or unintentionally — malform our thinking.

Blackburn’s advocacy for critical philosophical reflection can be paired with the full motto of Goya’s etching:

Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of her wonders.

Philosophy’s transformative power

B eyond the clarification of knowledge, the greatest philosophy — like the greatest science — has enormous explanatory power that can transform how we see the world.

Just as Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity skewers our everyday notion of time, so Friedrich Nietzsche’s dissection of morality challenges our everyday notions of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, John Locke’s analysis of color challenges our very idea of whether perception is reality, and Lucretius’s timeless reflection on death helps us cope with our mortality.

The world is uncertain, and the value of philosophy lies precisely in facing up to this uncertainty — and in finding footholds for knowledge and progress in spite of it. As the 20th-century philosophical giant Bertrand Russell summarizes in his wonderful exposition on why philosophy matters :

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

Discover philosophy’s greatest wisdom

I f you’re interested in learning more about philosophy, our celebrated introductory philosophy course, Life’s Big Questions , distills philosophy’s best answers to some of life’s most troubling questions, taking you on a whirlwind five-day journey of reflection, understanding, and discovery. Here are the questions covered:

Why does anything exist? Is the world around us ‘real’? What makes us conscious? Do we have free will? How should we approach life?

Enroll today, and each day over five days, you’ll receive beautifully-packaged materials that distill philosophy’s best answers to these questions from the last few millennia. Interested in learning more? Explore the course now .

By choosing to learn more about philosophy, a wonderful journey of self-discovery awaits you... have fun exploring!

Life’s Big Questions: Your Concise Guide to Philosophy’s Most Important Wisdom

Why does anything exist? Do we have free will? How should we approach life? Discover the great philosophers’ best answers to life’s big questions.

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for our courses)

Latest Course Reviews:

★★★★★ Very good

VERIFIED BUYER

★★★★★ Great intro

★★★★★ Great

See All Course Reviews

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

Philosophy: What and Why?

Find a job in philosophy, what is philosophy.

Philosophy is the systematic and critical study of fundamental questions that arise both in everyday life and through the practice of other disciplines. Some of these questions concern the nature of reality : Is there an external world? What is the relationship between the physical and the mental? Does God exist? Others concern our nature as rational, purposive, and social beings: Do we act freely? Where do our moral obligations come from? How do we construct just political states? Others concern the nature and extent of our knowledge: What is it to know something rather than merely believe it? Does all of our knowledge come from sensory experience? Are there limits to our knowledge? And still others concern the foundations and implications of other disciplines: What is a scientific explanation? What sort of knowledge of the world does science provide? Do scientific theories, such as evolutionary theory, or quantum mechanics, compel us to modify our basic philosophical understanding of, and approach to, reality? What makes an object a work of art? Are aesthetic value judgments objective? And so on.

The aim in Philosophy is not to master a body of facts, so much as think clearly and sharply through any set of facts. Towards that end, philosophy students are trained to read critically, analyze and assess arguments, discern hidden assumptions, construct logically tight arguments, and express themselves clearly and precisely in both speech and writing.

Here are descriptions of some of the main areas of philosophy:

Epistemology studies questions about knowledge and rational belief. Traditional questions include the following: How can we know that the ordinary physical objects around us are real (as opposed to dreamed, or hallucinated, as in the Matrix)? What are the factors that determine whether a belief is rational or irrational? What is the difference between knowing something and just believing it? (Part of the answer is that you can have false beliefs, but you can only know things that are true. But that’s not the whole answer—after all, you might believe something true on the basis of a lucky guess, and that wouldn’t be knowledge!) Some other questions that have recently been the subject of lively debate in epistemology include: Can two people with exactly the same evidence be completely rational in holding opposite beliefs? Does whether I know something depend on how much practical risk I would face if I believed falsely? Can I rationally maintain confident beliefs about matters on which I know that others, who are seemingly every bit as intelligent, well-informed, unbiased and diligent as I am, have come to opposite conclusions?

Metaphysics is the study of what the world is like—or (some would say) what reality consists in. Metaphysical questions can take several forms. They can be questions about what exists (questions of ontology); they can be questions what is fundamental (as opposed to derivative); and they can be questions about what is an objective feature of the world (as opposed to a mere consequence the way in which creatures like us happen to interact with that world). Questions that are central to the study of metaphysics include questions about the nature of objects, persons, time, space, causation, laws of nature, and modality. The rigorous study of these questions has often led metaphysicians to make surprising claims. Plato thought that alongside the observable, concrete world there was a realm of eternal, unchanging abstract entities like Goodness, Beauty, and Justice. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz claimed that the world was composed of tiny indivisible souls, called monads. Even today contemporary metaphysicians have been known to doubt the existence of ordinary objects, to deny the possibility of free will, and to argue that our world is just one of a plurality of worlds.

Logic is the study of the validity of patterns of inference. Logic is not a branch of psychology: It does not concern how people actually reason or which kinds of reasoning they find intuitively compelling. Rather, logic concerns the question of when a claim is conclusively supported by other claims. For instance, the inference from the claims “it is raining” and “if it is raining then the streets are wet” to the claim “the streets are wet” is logically valid – the premises conclusively support the conclusion. The validity of this specific inference, and of other inferences of the same form, is tied to the nature of the concept “if … then”. More generally, the notion of logical validity is closely connected to the nature of concepts such as “and”, “or”, “not”, “if … then”, “all”, and “some”. In studying the notion of logical validity, logicians have developed symbolic languages. These enable us to state claims clearly and precisely, and to investigate the exact structure of an argument. These languages have turned out to be useful within philosophy and other disciplines, including mathematics and computer science. Some of the questions about logic studied by members of the philosophy department include: Given that logic is not an empirical science, how can we have knowledge of basic logical truths? What is the connection between logic and rationality? Can mathematics be reduced to logic? Should we revise logic to accommodate vague or imprecise language? Should we revise logic to answer the liar paradox and other paradoxes concerning truth?

Political philosophy is the philosophical study of concepts and values associated with political matters. For one example, is there any moral obligation to do what the law says just because the law says so, and if so on what grounds? Many have said we consent to obey. Did you consent to obey the laws? Can one consent without realizing it? Are there other grounds for an obligation to obey the law? Another central question is what would count as a just distribution of all the wealth and opportunity that is made possible by living in a political community? Is inequality in wealth or income unjust? Much existing economic inequality is a result of different talents, different childhood opportunities, different gender, or just different geographical location. What might justify inequalities that are owed simply to bad luck? Some say that inequality can provide incentives to produce or innovate more, which might benefit everyone. Others say that many goods belong to individuals before the law enters in, and that people may exchange them as they please even if this results in some having more than others. So (a third question), what does it mean for something to be yours, and what makes it yours?

The Philosophy of Language is devoted to the study of questions concerned with meaning and communication. Such questions range from ones that interact closely with linguistic theory to questions that are more akin to those raised in the study of literature. Very large questions include: What is linguistic meaning? How is the meaning of linguistic performances similar to and different from the meanings of, say, gestures or signals? What is the relationship between language and thought? Is thought more fundamental than language? Or is there some sense in which only creatures that can speak can think? To what extent does the social environment affect the meaning and use of language? Other questions focus on the communicative aspect of language, such as: What is it to understand what someone else has said? What is it to assert something? How is assertion related to knowledge and belief? And how is it that we can gain knowledge from others through language? Yet other questions focus on specific features of the languages we speak, for example: What is it a name to be a name of a particular thing? What's the relationship between the meanings of words and the meanings of sentences? Is there an important difference between literal and figurative uses of language? What is metaphor? And how does it work?

Ethics is the study of what we ought to do and what sorts of people we ought to be. Ethicists theorize about what makes acts right and wrong and what makes outcomes good and bad, and also about which motivations and traits of character we should admire and cultivate. Some other questions that ethicists try to answer are closely related to the central ones. They include: What does it mean to act freely? Under what conditions are we responsible for our good and bad acts? Are moral claims true and false, like ordinary descriptive claims about our world, and if they are what makes them so?

The History of Philosophy plays a special role in the study of philosophy. Like every other intellectual discipline, philosophy has of course a history. However, in the case of philosophy an understanding of its history - from its ancient and medieval beginnings through the early modern period (the 17th and 18th centuries) and into more recent times - forms a vital part of the very enterprise of philosophy, whether in metaphysics and epistemology or in ethics, aesthetics, and political philosophy. To study the great philosophical works of the past is to learn about the origins and presuppositions of many of the problems that occupy philosophy today. It is also to discover and to come to appreciate different ways of dealing with these problems, different conceptions of what the fundamental problems of philosophy are, and indeed different ways of doing philosophy altogether. And it is also the study of works—from Plato and Aristotle, through Kant and Mill and more recent writers—that have shaped much of Western culture far beyond academic philosophy. Many of the most creative philosophers working today have also written on various topics in the history of philosophy and have found their inspiration in great figures of the past.

Why Study Philosophy?

This question may be understood in two ways: Why would one engage in the particular intellectual activities that constitute philosophical inquiry? And how might the study of philosophy affect my future career prospects?

Philosophy as intellectual activity may have a number of motivations:

- Intellectual curiosity: philosophy is essentially a reflective-critical inquiry motivated by a sense of intellectual “wonder.” What is the world like? Why is it this way, rather than another? Who am I? Why am I here?

- Interest in cultural and intellectual history: as a discipline, philosophy pays a great deal of attention to its history, and to the broader cultural and intellectual context in which this history unfolds.

- Sharpening thinking skills: the study of philosophy is especially well suited to the development of a variety of intellectual skills involved in the analysis of concepts, the critique of ideas, the conduct of sound reasoning and argumentation; it is important to emphasize that philosophical inquiry also fosters intellectual creativity (developing new concepts, or new approaches to problems, identifying new problems, and so on).

- Sharpening writing skills: the writing of philosophy is especially rigorous

Philosophy might affect future career prospects in a number of ways:

- Some philosophy concentrators go on to graduate school to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy. Most of those become professors of philosophy, which means that their professional lives are devoted to research and teaching in philosophy.

- A philosophy concentration is not limiting: in fact, the skills it develops and sharpens are transferable to a wide variety of professional activities. Obvious examples include the application of reasoning and argumentation skills to the practice of law; less obvious examples include the application of analytical and critical skills to journalism, investment banking, writing, publishing, and so on; even less obvious examples include putting one’s philosophical education to work in business entrepreneurship, political and social activism, and even creative arts.

Why Does Philosophy Matter In The 21st Century?