Why was the Turner Thesis abandoned by historians

Fredrick Jackson Turner’s thesis of the American frontier defined the study of the American West during the 20th century. In 1893, Turner argued that “American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.” ( The Frontier in American History , Turner, p. 1.) Jackson believed that westward expansion allowed America to move away from the influence of Europe and gain “independence on American lines.” (Turner, p. 4.) The conquest of the frontier forced Americans to become smart, resourceful, and democratic. By focusing his analysis on people in the periphery, Turner de-emphasized the importance of everyone else. Additionally, many people who lived on the “frontier” were not part of his thesis because they did not fit his model of the democratizing American. The closing of the frontier in 1890 by the Superintendent of the census prompted Turner’s thesis.

While appealing, the Turner thesis stultified scholarship on the West. In 1984, colonial historian James Henretta even stated, “[f]or, in our role as scholars, we must recognize that the subject of westward expansion in itself longer engages the attention of many perhaps most, historians of the United States.” ( Legacy of Conquest , Patricia Limerick, p. 21.) Turner’s thesis had effectively shaped popular opinion and historical scholarship of the American West, but the thesis slowed continued academic interest in the field.

Reassessment of Western History

In the last half of the twentieth century, a new wave of western historians rebelled against the Turner thesis and defined themselves by their opposition to it. Historians began to approach the field from different perspectives and investigated the lives of Women, miners, Chicanos, Indians, Asians, and African Americans. Additionally, historians studied regions that would not have been relevant to Turner. In 1987, Patricia Limerick tried to redefine the study of the American West for a new generation of western scholars. In Legacy of Conquest, she attempted to synthesize the scholarship on the West to that point and provide a new approach for re-examining the West. First, she asked historians to think of the America West as a place and not as a movement. Second, she emphasized that the history of the American West was defined by conquest; “[c]onquest forms the historical bedrock of the whole nation, and the American West is a preeminent case study in conquest and its consequences.” (Limerick, p. 22.)

Finally, she asked historians to eliminate the stereotypes from Western history and try to understand the complex relations between the people of the West. Even before Limerick’s manifesto, scholars were re-evaluating the west and its people, and its pace has only quickened. Whether or not scholars agree with Limerick, they have explored new depths of Western American history. While these new works are not easy to categorize, they do fit into some loose categories: gender ( Relations of Rescue by Peggy Pascoe), ethnicity ( The Roots of Dependency by Richard White, and Lewis and Clark Among the Indians by James P. Rhonda), immigration (Impossible Subjects by Ming Ngai), and environmental (Nature’s Metropolis by William Cronon, Rivers of Empire by Donald Worster) history. These are just a few of the topics that have been examined by American West scholars. This paper will examine how these new histories of the American West resemble or diverge from Limerick’s outline.

Defining America or a Threat to America's Moral Standing

Unlike Limerick, Pascoe did not find it necessary to define the west or the frontier. She did not have to because the Protestant missionaries in her story defined it for her. While Turner may have believed that the West was no longer the frontier in 1890, the missionaries certainly would have disagreed. In fact, the rescue missions were placed in the communities that the Victorian Protestant missionary judged to be the least “civilized” parts of America (Lakota Territory, San Francisco’s Chinatown, rough and tumble Denver and Salt Lake City.) Instead of being a story of conquest by Victorian or western morality, it was a story of how that morality was often challenged and its terms were negotiated by culturally different communities. Pascoe’s primary goal in this work was not only to eliminate stereotypes but to challenge the notion that white women civilized the west. While conquest may be a component of other histories, no one group in Pascoe’s story successfully dominated any other.

Changing the Narrative of Native Americans in the West

Instead of describing the initial interactions of the United States government with the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, White explained how the self-sufficient economies of these people were destroyed. White described how the United States government turned these successful native people into wards of the American state. His story explained how the United States conquered these tribes without firing a shot. The consequence of this conquest was the creation of weak, dependent nations that could not survive without handouts from the federal government. Like Rhonda, White also sought to shatter long-standing stereotypes and myths regarding Native Americans. White verified that each of these tribes had self-sufficient economies which permitted prosperous lifestyles for their people before the devastating interactions with the United States government occurred. The United States in each case fundamentally altered the tribes’ economies and environments. These alterations threatened the survival of the tribes. In some cases, the United States sought to trade with these tribes in an effort put the tribes in debt. After the tribes were in debt, the United States then forced the tribes to sell their land. In other situations, the government damaged the tribes’ economies even when they sought to help them.

The Impact of Immigrants to the West

While illegal immigration is not an issue isolated to the history of the American West, the immigrants moved predominantly into California, Texas and the American Southwest. Like Anglo settlers who were attracted to the West for the potential for new life in the nineteenth century, illegal immigrants continued to move in during the twentieth. The illegal immigrants were welcomed, despite their status, because California’s large commercial farms needed inexpensive labor to harvest their crops. Impossible Subjects describes four groups of illegal immigrants (Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese and Mexican braceros) who were created by the United States immigration policy. Ngai specifically examines the role that the government played in defining, controlling and disciplining these groups for their allegedly illegal misconduct.

The Rise of Western Environmental History

In Nature’s Metropolis , Cronon, used the central place theory to analyze the economic and ecological development of Chicago. Johann Heinrich von Thunen developed the central place theory to explain the development of cities. Essentially, geographically different economic zones form in concentric circles the farther you went from the city. These different zones form because of the time it takes to get the different types of goods to market. Closest to the city and then moving away you would have the following zones: first, intensive agriculture, second, extensive agriculture, third, livestock raising, fourth, trading, hunting and Indian trade and finally, you would have the wilderness. While the landscape of the Mid-West was more complicated than this, Cronon posits that the “city and country are inextricably connected and that market relations profoundly mediate between them.” (Cronon, p. 52.) By emphasizing the connection between the city of Chicago and the rural lands that surrounded it, Cronon was able to explain how the land, including the West, developed. Cronon argued that the development of Chicago had a profound influence on the development and appearance of the Great West. Essentially Cronon used the creation of the Chicago commodities and trading markets to explain how different parts of the Mid-West and West produced different types of resources and fundamentally altered their ecology.

Each of these books demonstrates that the Turner thesis no longer holds a predominant position in the scholarship of the American West. The history of the American West has been revitalized by its demise. While westward expansion plays an important role in the history of the United States, it did not define the west. Turner’s thesis was fundamentally undermined because it did not provide an accurate description of how the West was peopled. The nineteenth century of the west is not composed primarily of family farmers. Instead, it is a story of a region peopled by a diverse group of people: Native Americans, Asians, Chicanos, Anglos, African Americans, women, merchants, immigrants, prostitutes, swindlers, doctors, lawyers, farmers are just a few of the characters who inhabit western history.

Suggested Readings

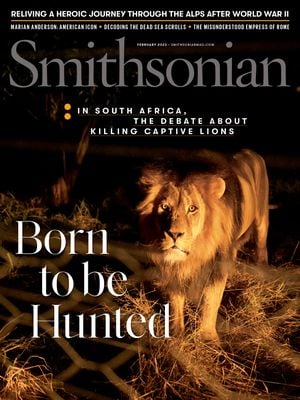

How the Myth of the American Frontier Got Its Start

Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis informed decades of scholarship and culture. Then he realized he was wrong

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard

:focal(400x301:401x302)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/11/1211e4cd-7311-4c83-9370-d86aa5ebc2d5/illustration_of_people_on_horseback_looking_at_an_open_landscape.jpg)

On the evening of July 12, 1893, in the hall of a massive new Beaux-Arts building that would soon house the Art Institute of Chicago, a young professor named Frederick Jackson Turner rose to present what would become the most influential essay in the study of U.S. history.

It was getting late. The lecture hall was stifling from a day of blazing sun, which had tormented the throngs visiting the nearby Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, a carnival of never-before-seen wonders, like a fully illuminated electric city and George Ferris’ 264-foot-tall rotating observation wheel. Many of the hundred or so historians attending the conference, a meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA), were dazed and dusty from an afternoon spent watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show at a stadium near the fairground’s gates. They had already sat through three other speeches. Some may have been dozing off as the thin, 31-year-old associate professor from the University of Wisconsin in nearby Madison began his remarks.

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $19.99

This article is a selection from the January/February 2023 issue of Smithsonian magazine

Turner told them the force that had forged Americans into one people was the frontier of the Midwest and Far West. In this virgin world, settlers had finally been relieved of the European baggage of feudalism that their ancestors had brought across the Atlantic, freeing them to find their true selves: self-sufficient, pragmatic, egalitarian and civic-minded. “The frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people,” he told the audience. “In the crucible of the frontier, the immigrants were Americanized, liberated and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics.”

The audience was unmoved.

In their dispatches the following morning, most of the newspaper reporters covering the conference didn’t even mention Turner’s talk. Nor did the official account of the proceedings prepared by the librarian William F. Poole for The Dial , an influential literary journal. Turner’s own father, writing to relatives a few days later, praised Turner’s skills as the family’s guide at the fair, but he said nothing at all about the speech that had brought them there.

Yet in less than a decade, Turner would be the most influential living historian in the United States, and his Frontier Thesis would become the dominant lens through which Americans understood their character, origins and destiny. Soon, Jackson’s theme was prevalent in political speech, in the way high schools taught history, in patriotic paintings—in short, everywhere. Perfectly timed to meet the needs of a country experiencing dramatic and destabilizing change, Turner’s thesis was swiftly embraced by academic and political institutions, just as railroads, manufacturing machines and telegraph systems were rapidly reshaping American life.

By that time, Turner himself had realized that his theory was almost entirely wrong.

American historians had long believed that Providence had chosen their people to spread Anglo-Saxon freedom across the continent. As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, Turner was introduced to a different argument by his mentor, the classical scholar William Francis Allen. Extrapolating from Darwinism, Allen believed societies evolved like organisms, adapting themselves to the environments they encountered. Scientific laws, not divine will, he advised his mentee, guided the course of nations. After graduating, Turner pursued a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, where he impressed the history program’s leader, Herbert Baxter Adams, and formed a lifelong friendship with one of his teachers, an ambitious young professor named Woodrow Wilson. The connections were useful: When Allen died in 1889, Adams and Wilson aided Turner in his quest to take Allen’s place as head of Wisconsin’s history department. And on the strength of Turner’s early work, Adams invited him to present a paper at the 1893 meeting of the AHA, to be held in conjunction with the World’s Congress Auxiliary of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/bc/61bc38a7-853f-4c6b-823e-71c95d62687d/manifest_destiny.jpg)

The resulting essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” offered a vivid evocation of life in the American West. Stripped of “the garments of civilization,” settlers between the 1780s and the 1830s found themselves “in the birch canoe” wearing “the hunting shirt and the moccasin.” Soon, they were “planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick” and even shouting war cries. Faced with Native American resistance—Turner largely overlooked what the ethnic cleansing campaign that created all that “free land” might say about the American character—the settlers looked to the federal government for protection from Native enemies and foreign empires, including during the War of 1812, thus fostering a loyalty to the nation rather than to their half-forgotten nations of origin.

He warned that with the disappearance of the force that had shaped them—in 1890, the head of the Census Bureau concluded there was no longer a frontier line between areas that had been settled by European Americans and those that had not—Americans would no longer be able to flee west for an easy escape from responsibility, failure or oppression. “Each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the bondage of the past,” Turner concluded. “Now … the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

When he left the podium on that sweltering night, he could not have known how fervently the nation would embrace his thesis.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3a/1d/3a1d78c2-4533-4dbf-9fc9-66306936b710/white_guy.jpg)

Like so many young scholars, Turner worked hard to bring attention to his thesis. He incorporated it into the graduate seminars he taught, lectured about it across the Midwest and wrote the entry for “Frontier” in the widely read Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia. He arranged to have the thesis reprinted in the journal of the Wisconsin Historical Society and in the AHA’s 1893 annual report. Wilson championed it in his own writings, and the essay was read by hundreds of schoolteachers who found it reprinted in the popular pedagogical journal of the Herbart Society, a group devoted to the scientific study of teaching. Turner’s big break came when the Atlantic Monthly ’s editors asked him to use his novel viewpoint to explain the sudden rise of populists in the rural Midwest, and how they had managed to seize control of the Democratic Party to make their candidate, William Jennings Bryan, its nominee for president. Turner’s 1896 Atlantic Monthly essay , which tied the populists’ agitation to the social pressures allegedly caused by the closing of the frontier—soil depletion, debt, rising land prices—was promptly picked up by newspapers and popular journals across the country.

Meanwhile, Turner’s graduate students became tenured professors and disseminated his ideas to the up-and-coming generation of academics. The thrust of the thesis appeared in political speeches, dime-store western novels and even the new popular medium of film, where it fueled the work of a young director named John Ford who would become the master of the Hollywood western. In 1911, Columbia University’s David Muzzey incorporated it into a textbook—initially titled History of the American People —that would be used by most of the nation’s secondary schools for half a century.

Americans embraced Turner’s argument because it provided a fresh and credible explanation for the nation’s exceptionalism—the notion that the U.S. follows a path soaring above those of other countries—one that relied not on earlier Calvinist notions of being “the elect,” but rather on the scientific (and fashionable) observations of Charles Darwin. In a rapidly diversifying country, the Frontier Thesis denied a special role to the Eastern colonies’ British heritage; we were instead a “composite nation,” birthed in the Mississippi watershed. Turner’s emphasis on mobility, progress and individualism echoed the values of the Gilded Age—when readers devoured Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches stories—and lent them credibility for the generations to follow.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/69/ea696129-c32c-4947-9ce7-64648e2f2cea/janfeb2023_e01_prologue.jpg)

But as a researcher, Turner himself turned away from the Frontier Thesis in the years after the 1890s. He never wrote it down in book form or even in academic articles. He declined invitations to defend it, and before long he himself lost faith in it.

For one thing, he had been relying too narrowly on the experiences in his own region of the Upper Midwest, which had been colonized by a settlement stream originating in New England. In fact, he found, the values he had ascribed to the frontier’s environmental conditioning were actually those of this Greater New England settlement culture, one his family and most of his fellow citizens in Portage, Wisconsin, remained part of, with their commitment to strong village and town governments, taxpayer-financed public schools and the direct democracy of the town meeting. He saw that other parts of the frontier had been colonized by other settlement streams anchored in Scots-Irish Appalachia or in the slave plantations of the Southern lowlands, and he noted that their populations continued to behave completely differently from one another, both politically and culturally, even when they lived in similar physical environments. Somehow settlers moving west from these distinct regional cultures were resisting the Darwinian environmental and cultural forces that had supposedly forged, as Turner’s biographer, Ray Allen Billington, put it, “a new political species” of human, the American. Instead, they were stubbornly remaining themselves. “Men are not absolutely dictated to by climate, geography, soils or economic interests,” Turner wrote in 1922. “The influence of the stock from which they sprang, the inherited ideals, the spiritual factors, often triumph over the material interests.”

Turner spent the last decades of his life working on what he intended to be his magnum opus, a book not about American unity but rather about the abiding differences between its regions, or “sections,” as he called them. “In respect to problems of common action, we are like what a United States of Europe would be,” he wrote in 1922, at the age of 60. For example, the Scots-Irish and German small farmers and herders who settled the uplands of the southeastern states had long clashed with nearby English enslavers over education spending, tax policy and political representation. Turner saw the whole history of the country as a wrestling match between these smaller quasi-nations, albeit a largely peaceful one guided by rules, laws and shared American ideals: “When we think of the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, as steps in the marking off of spheres of influence and the assignment of mandates [between nations] … we see a resemblance to what has gone on in the Old World,” Turner explained. He hoped shared ideals—and federal institutions—would prove cohesive for a nation suddenly coming of age, its frontier closed, its people having to steward their lands rather than striking out for someplace new.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/79/ea79b5eb-7dd4-4ca0-9d75-f4ad5333a116/janfeb2023_e12_prologue.jpg)

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Colin_Woodard_PPH_Photo_crop_thumbnail_1.png)

Colin Woodard | | READ MORE

Colin Woodard is a journalist and historian, and the author of six books including Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood . He lives in Maine.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 The Making of a National Identity: The Frontier Thesis

Author Webpage

- Published: April 2003

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Frederick Jackson Turner's frontier thesis became a significant force in shaping the national identity of the U.S. The ideologies incorporated into Turner's frontier thesis were not only meant to provide a historical interpretation of how the U.S. came into being but also satisfied the national need for a “usable past.” This frontier thesis was able to transmit a series of symbols that became imbedded in the nation's self‐perception and self‐understanding: Virgin land, wilderness, land and democracy, Manifest Destiny, chosen race. Race must be understood as an important piece of this developing national identity because the idea of “purity” of race was used as a rationalization to colonize, exclude, devalue, and even exterminate the native borderlands people.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 9 |

| November 2022 | 11 |

| December 2022 | 9 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 18 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 6 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 8 |

| December 2023 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 15 |

| March 2024 | 11 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 9 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.9: The West as History- the Turner Thesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10013

- American YAWP

- Stanford via Stanford University Press

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

.png?revision=1)

In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The young Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis,” one of the most influential theories of American history, in his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner looked back at the historical changes in the West and saw, instead of a tsunami of war and plunder and industry, waves of “civilization” that washed across the continent. A frontier line “between savagery and civilization” had moved west from the earliest English settlements in Massachusetts and Virginia across the Appalachians to the Mississippi and finally across the Plains to California and Oregon. Turner invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.” 26

Americans, Turner said, had been forced by necessity to build a rough-hewn civilization out of the frontier, giving the nation its exceptional hustle and its democratic spirit and distinguishing North America from the stale monarchies of Europe. Moreover, the style of history Turner called for was democratic as well, arguing that the work of ordinary people (in this case, pioneers) deserved the same study as that of great statesmen. Such was a novel approach in 1893.

But Turner looked ominously to the future. The Census Bureau in 1890 had declared the frontier closed. There was no longer a discernible line running north to south that, Turner said, any longer divided civilization from savagery. Turner worried for the United States’ future: what would become of the nation without the safety valve of the frontier? It was a common sentiment. Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Turner that his essay “put into shape a good deal of thought that has been floating around rather loosely.” 27

The history of the West was many-sided and it was made by many persons and peoples. Turner’s thesis was rife with faults, not only in its bald Anglo-Saxon chauvinism—in which nonwhites fell before the march of “civilization” and Chinese and Mexican immigrants were invisible—but in its utter inability to appreciate the impact of technology and government subsidies and large-scale economic enterprises alongside the work of hardy pioneers. Still, Turner’s thesis held an almost canonical position among historians for much of the twentieth century and, more importantly, captured Americans’ enduring romanticization of the West and the simplification of a long and complicated story into a march of progress.

Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Journal of American Studies

- > Volume 27 Issue 2

- > Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis and the...

Article contents

Frederick jackson turner's frontier thesis and the self-consciousness of america.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

In their work on Turner's formative period, Ray A. Billington and Fulmer Mood have shown that the Frontier Thesis, formulated in 1893 in “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” is not so much a brilliant early effort by a young scholar as a mature study in which Turner gave his ideas an organization that proved to be final. During the rest of his life he developed but never disclaimed or modified them. Billington and Mood also add that the Frontier Thesis is meant to test a new approach to history that Turner had been developing since the beginning of his academic career. We can fully understand it, then, only by setting it within the framework of the assumptions and goals of his 1891 essay, “The Significance of History,” Turner's only attempt to sketch a philosophy of history.

Access options

1 Billington , Ray A. , The Genesis of the Frontier Thesis: A Study in Historical Creativity ( San Marino, Ca. : The Huntington Library , 1971 ) Google Scholar ; Mood , Fulmer , “ The Development of Frederick J.Turner as a Historical Thinker ,” Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts , 1937–42, 34 ( 1943 ), 283 – 352 . Google Scholar

2 Turner , Frederick J. , “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin , 14 12 1893 . Google Scholar

3 Turner , Frederick J. , “ The Significance of History ,” Wisconsin Journal of Education , 21 ( 10 1891 ), 230 –4, ( 11 1891 ), 253–6. Google Scholar

4 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” in Frontier and Section: Selected Essays of F. J. Turner , Billington , Ray A. ed. ( Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice-Hall , 1961 ), 20 . Google Scholar

5 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” 17 . Google Scholar

7 Ibid. , 18.

8 Ibid. , 27.

9 Ibid. , 18.

10 Turner , Frederick J. , “Problems in American History,” in Frontier and Section , Billington, ed., 29 . Google Scholar

11 Billington , Ray A. , Frederick J. Turner: Historian, Scholar, Teacher ( New York : Oxford University Press , 1973 ), chapter 5 Google Scholar ; Coleman , William , “ Science and Symbol in Turner Frontier Hypothesis ,” American Historical Review , 72 , 3 ( 1966 ), 22 – 49 . CrossRef Google Scholar

12 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 1 – 2 Google Scholar ; see also “Problems in American History,” 29 . Google Scholar

13 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 2 . Google Scholar

14 The link between the “instinct for moving” and the development of human history and culture was forcefully made by Turner in an 1891 address to the Madison Literary Club: “The colonizing spirit is one form of the nomadic instinct. The immigrant train on its way to the far west or the steamer laden with passengers for Australia is but the last embodiment of the impulse that took Abraham out of Ur of the Chaldees and sent our Aryan forefathers from their primitive pasture lands to Greece and Italy and India and Scandinavia”: Turner , Frederick J. , “American Colonization,” published in Carpenter , Ronald H. , The Eloquence of Frederick J. Turner ( San Marino, Ca. : The Huntington Library , 1893 ), 176 . Google Scholar

15 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 11 . Google Scholar

16 See, for instance, his treatment of populism, “The Significance of the Frontier,” 32 . Google Scholar

17 Ibid. , 37.

18 Ibid. , 4.

19 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” in Frontier and Section , Billington ed, 206 Google Scholar ; also: “At first the frontier was the Atlantic coast. It was the frontier of Europe in a very real sense. Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American,” Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 4 . Google Scholar

20 Foucault , Michel , L'ordre du discours ( Paris : 1970 ). Google Scholar

21 See, Trails: Toward a New Western History , Limerick , Patricia Nelson , Milner , Clyde A. II , Rankin , Charles E. eds. ( University Press of Kansas ). CrossRef Google Scholar

22 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 3 – 4 . Google Scholar

23 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 205 . Google Scholar

24 Ibid. , 207.

25 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 2 . Google Scholar

26 See Morgan , Lewis Henry , Ancient Society ( 1877 ). Google Scholar

27 Billington , , Frederick Jackson Turner , 76 –9, 122–3. Google Scholar

28 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 21 , 38. Google Scholar

29 Ibid. , 12.

30 Ibid. , 4.

31 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 205 . Google Scholar

32 See Morgan , Lewis H. , Ancient Society ( 1877 ) Google Scholar , and Bagehot , Walter , Physics and Politics: An Application of the Principles of Natural Selection and Heredity to Political Society ( 1872 ) Google Scholar , on the first and second points respectively. The pervasive influence in late 19th century culture of Sumner Maine's theory of the transition from status to contract should also be kept in mind.

33 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 30 . Google Scholar

34 Ibid. , 37; “The problem of the West,” 211 . Google Scholar

35 Ibid. , quoted.

36 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 31 . Google Scholar

37 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 213 . Google Scholar

38 Billington , , Frederick Jackson Turner , 425 . Google Scholar

39 Bonazzi , Tiziano , “Un'analisi della American Promise: ordine e senso nel discorso storico-politico,” in Bonazzi , Tiziano , Struttura e metamorfosi della civilta' progressista ( Venezia : Marsilio , 1974 ), 41 – 140 . Google Scholar

40 Baritz , Loren , “ The Idea of the West ,” American Historical Review , 66 , 3 ( 1961 ), 618 –40. CrossRef Google Scholar An important parallel can also be made with Walzer , Michael , Exodus and Revolution ( New York : Basic Books , 1985 ). Google Scholar

41 Smith , Henry Nash , Virgin Land: The American West As Symbol and Myth ( Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press , 1950 ). Google Scholar On the importance of foundation myths, see Voegelin , Eric , The New Science of Politics ( Chicago : University of Chicago Press , 1952 ). Google Scholar

42 Noble , David W. , Historians against History. The Frontier Thesis and the National Covenant in American Historical Writing since 1830 ( Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press , 1965 ) Google Scholar , and The End of American History ( Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press , 1985 ). Google Scholar

43 Turner , to Becker , Carl , 21 01 1911 Google Scholar , in Jacobs , Wilbur R. , The Historical World of Frederick J. Turner ( New Haven-London : Yale University Press , 1968 ), 135 Google Scholar ; also, Turner , to Skinner , Constance Lindsay , 15 03 1922 Google Scholar , in Jacobs , , The Historical World , 56 . Google Scholar

44 Turner , , “Problems in American History,” 29 . Google Scholar

45 Ibid. , 32.

46 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 68 –9. Google Scholar

47 Ibid. , 69. This expression follows immediately upon the sentence previously quoted.

48 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 38 . Google Scholar

49 Turner , to Becker , Carl , in Jacobs , , The Historical World , 135 . Google Scholar

50 Turner , , “Contributions of the West to American Democracy,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 264 –6. Google Scholar

51 Ibid. , 258.

52 Turner , , “The Problem of the West,” 216 . Google Scholar

53 Turner , , “The West and American Ideals,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 305 . Google Scholar

54 Turner , , “Social Forces in American History,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 331 . Google Scholar

55 Turner , , “Pioneer Ideals and the State University,” Google Scholar in Turner , , The Frontier in American History , 284 . Google Scholar

56 Turner , , “The State University,” in America's Great Frontier and Sections: Frederick Jackson Turner's Unpublished Essays , Jacobs , Wilbur R. ed. ( Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press , 1969 ), 196 . Google Scholar

57 Turner , , “The West and American Ideals,” 300 . Google Scholar

58 See his “Pioneer Ideals and the State University,” 269 –89. Google Scholar

59 Turner , , “The Significance of History,” in Frontier and Section , Billington ed., 21 . Google Scholar

60 Ibid. , 18.

61 Lyotard , Jean-Francois , La condition postmoderne ( Paris : Les Editions de Minuit , 1979 ). Google Scholar

62 Reference is made here to Wallerstein , Immanuel , The Modern World-System ( New York : Academic Press , 1976 ). Google Scholar

63 Bercovitch , Sacvan , The American Jeremiad ( Madison : Wisconsin University Press , 1978 ) Google Scholar ; also Bercovitch , Sacvan , “The Rites of Assent: Rhetoric, Ritual, and the Ideology of American Consensus,” in The American Self: Myth, Ideology and Popular Culture , Girgus , Sam B. ed. ( Albuquerque : New Mexico University Press , 1980 ), 5 – 45 . Google Scholar On the “rhetorical impact” of the Frontier Thesis upon the American public mind see Carpenter , Ronald H. , The Eloquence of F. J. Turner , 47 – 95 . Google Scholar

64 Wiebe , Robert H. , The Search for Order , 1877–1920 ( New York : Hill and Wang , 1967 ), ch. 5. Google Scholar

65 The idea of a transition from an age of scarcity to an age of abundance was articulated by Patten , Simon N. , professor of economics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, in The New Basis of Civilization ( New York : Macmillan , 1907 ). Google Scholar

66 Tudor , Henry , Political Myth ( London : 1972 ) CrossRef Google Scholar ; also, Bonazzi , Tiziano , “Mito politico,” in Dizionario di politico , Bobbio , Norberto and Matteucci , Nicola eds. ( Torino : UTET , 1976 ), 587 –94. Google Scholar The most important interpretation of politics based on the dialectics amicus-hostis is that of Carl Schmitt, see, among his many publications, Der Bergriff des Politischen. Text von 1932 mit einem Vorwort und drei Corollarien (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 1963 ). Google Scholar

67 Barthes , Ronald , Mythologies ( Paris : Editions du Seuil , 1957 ). Google Scholar

68 See Turner's articles on immigration in Chicago Record-Herald , 28 08 , 4, 11, 18, 25 09 , 16 10 1901 . Google Scholar Let us not forget, however, that Marcus Hansen was one of Turner's students.

69 Derrida , Jacques , L'autre cap ( Paris : Les Editions de Minuit , 1991 ). Google Scholar

70 Turner , , “The Significance of the Frontier,” 3 . Google Scholar

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 27, Issue 2

- Tiziano Bonazzi (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875800031509

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Excerpts from writings of Frederick Jackson Turner, 1890s-1920s

Frederick Jackson Turner is most famous for expounding the influential “Frontier Thesis” of American history, a thesis he first introduced in 1893 and which he expanded upon for the remainder of his scholarly career. See the following link for a short biography.

In the settlement of America we have to observe how European life entered the continent, and how America modified and developed that life and reacted on Europe. . . . [T]he frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails.

Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the old Europe . . .. The fact is, that here is a new product that is American. At first, the frontier was the Atlantic coast. It was the frontier of Europe in a very real sense. Moving westward, the frontier became more and more American. As successive terminal moraines result from successive glaciations, so each frontier leaves its traces behind it, and when it becomes a settled area the region still partakes of the frontier characteristics. Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady movement away from the influence of Europe, a steady growth of independence on American lines. And to study this advance, the men who grew up under these conditions, and the political, economic, and social results of it, is to study the really American part of our history.

. . [T]he frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people. The coast was preponderantly English, but the later tides of continental immigration flowed across to the free lands. . . . In the crucible of the frontier the immigrants were Americanized, liberated, and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics. The process has gone on from the early days to our own.

From the conditions of frontier life came intellectual traits of profound importance. The works of travelers along each frontier from colonial days onward describe certain common traits, and these traits have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded. The result is that, to the frontier, the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness, that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients, that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends, that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom -- these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.

The last chapter in the development of Western democracy is the one that deals with its conquest over the vast spaces of the new West. At each new stage of Western development, the people have had to grapple with larger areas, with bigger combinations. The little colony of Massachusetts veterans that settled at Marietta received a land grant as large as the State of Rhode Island. The band of Connecticut pioneers that followed Moses Cleaveland to the Connecticut Reserve occupied a region as large as the parent State. The area which settlers of New England stock occupied on the prairies of northern Illinois surpassed the combined area of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Men who had become accustomed to the narrow valleys and the little towns of the East found themselves out on the boundless spaces of the West dealing with units of such magnitude as dwarfed their former experience. The Great Lakes, the Prairies, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the Mississippi and the Missouri, furnished new standards of measurement for the achievement of this industrial democracy. Individualism began to give way to coöperation and to governmental activity. Even in the earlier days of the democratic conquest of the wilderness, demands had been made upon the government for support in internal improvements, but this new West showed a growing tendency to call to its assistance the powerful arm of national authority. In the period since the Civil War, the vast public domain has been donated to the individual farmer, to States for education, to railroads for the construction of transportation lines.

Moreover, with the advent of democracy in the last fifteen years upon the Great Plains, new physical conditions have presented themselves which have accelerated the social tendency of Western democracy. The pioneer farmer of the days of Lincoln could place his family on a flatboat, strike into the wilderness, cut out his clearing, and with little or no capital go on to the achievement of industrial independence. Even the homesteader on the Western prairies found it possible to work out a similar independent destiny, although the factor of transportation made a serious and increasing impediment to the free working-out of his individual career. But when the arid lands and the mineral resources of the Far West were reached, no conquest was possible by the old individual pioneer methods. Here expensive irrigation works must be constructed, coöperative activity was demanded in utilization of the water supply, capital beyond the reach of the small farmer was required. In a word, the physiographic province itself decreed that the destiny of this new frontier should be social rather than individual.

Magnitude of social achievement is the watchword of the democracy since the Civil War. From petty towns built in the marshes, cities arose whose greatness and industrial power are the wonder of our time. The conditions were ideal for the production of captains of industry. The old democratic admiration for the self-made man, its old deference to the rights of competitive individual development, together with the stupendous natural resources that opened to the conquest of the keenest and the strongest, gave such conditions of mobility as enabled the development of the large corporate industries which in our own decade have marked the West. Thus, in brief, have been outlined the chief phases of the development of Western democracy in the different areas which it has conquered. There has been a steady development of the industrial ideal, and a steady increase of the social tendency, in this later movement of Western democracy. While the individualism of the frontier, so prominent in the earliest days of the Western advance, has been preserved as an ideal, more and more these individuals struggling each with the other, dealing with vaster and vaster areas, with larger and larger problems, have found it necessary to combine under the leadership of the strongest. This is the explanation of the rise of those preëminent captains of industry whose genius has concentrated capital to control the fundamental resources of the nation.