The Impact of WeFuture’s ‘Challenge Your World’ Workshop in Amsterdam | Case Study

Holistic thinking: what it is, why it’s important, and how to do it.

- Holistic Thinking

- World Conservation

We humans like to simplify things. And that's a good thing, to begin with, because this characteristic protects us from too many stimuli, excessive demands and overload. We develop routines that help us cope with everyday life without having to expend a lot of thought and energy. We build a microcosm around ourselves, focusing on people and things in our immediate environment. We know our family and friends, our city and our work so well that we think we know how life works.

Sometimes, however, we find that things are not as simple as we would like to believe. Namely, when we encounter complex problems. Abruptly, we tend to realize that our individual view of the world can be one-sided. For example, we can feel quite uncomfortable when we realize that climate change is a real threat. Here, our microcosm with its usual solution patterns suddenly reaches its limits. We are faced with a problem that seems so complex and abstract that it can (and often does) make us feel overwhelmed.

But in this, there is creative power. In chaos lies the chance of creativity. Why? Because it forces us to step back from familiar perceptions. Because it allows us to see that our ‘individual’ world, to which we devote all our attention, is only a part of reality. And we see that we, as individuals, are a part of the whole of nature in its beauty. Changing our perspective from the individual details to the whole forms the basis for a way of thinking that aims to help solve problems in a more cohesive way: Holistic thinking.

What Is Holistic Thinking?

Holistic thinking means having a holistic approach by contemplating the bigger picture. "Holistic“ derives from the Greek word "holos", which stands for "whole" and "comprehensive". "Holistic" therefore, means "wholeness."

Aristotle, the famous Greek philosopher, has a quote that provides a great description of how the holistic way of thinking works: "The whole is more than the sum of its parts." To help explain the impact of this quote, let’s break the process down using a simple example:

- Collect all of the ‘parts’ of something - eg. building blocks.

- Sum them up by adding them together, ordering, and arranging them in a way that makes sense - eg. build up walls, create windows, and doors.

- After summing up the parts, we create a whole. - eg. a house

- However, the ‘whole’ (or in this case, the house) is more than that because we get more value and understanding through the ‘summing’ process. By adding these parts up together, we may now better understand: - Physical structures eg. the best way to build walls so they are insulated. - Scientific principles eg. balancing the weight of the house so gravity won't tear it down. - Human Impact eg. Once we move into the house, it becomes a home. We now have shelter, security, and an increased likelihood of survival.

By summing these parts, we have received so much more - the intangible assets like understanding, value, and meaning - about the whole that was not available to its parts alone. The holistic approach leads us to truly appreciate and comprehend the sum of parts, thus making it "more than".

How is Holistic Thinking Applied?

Holistic thinking can be applied to many systems; such as biological, social, mental, economic or spiritual systems.

It is a way of thinking that has been practiced by many indigenous people for many, many years - especially when it comes to health and wellness (an example of biological, mental, and spiritual systems). Whatsmore, some traditional health care systems that are rooted in holistic principles, such as the Ancient Indian Ayurveda and Amazonian Shamanism, are still practiced today!

One of the famous personalities associated with a holistic vision was Leonardo Da Vinci, the well-known Italian painter of the Mona Lisa, living in the Renaissance. He is admired by the world for his multidisciplinary approach to connecting logic and creativity. His holistic perspective of knowledge gathering was based on thinking beyond limits and resulted in iconic creative expression that has stood the test of time.

Holism was also the core of the worldview of another famous individual - Alexander von Humboldt, German naturalist and explorer. He didn’t see organisms, geological structures, weather phenomena, or human activities as detached; but as interacting entities of a larger complex system. He shaped the scientific perception of how everything is connected. Both Da Vinci and von Humboldt showed with their interdisciplinary approach how existing ideas and new concepts complement each other.

From ancient practices to famous personalities, the application and outcomes of holistic thinking is timeless. And this is most likely because this way of thinking stems from something bigger; Holism.

The Significance of Holism

“Holism (noun): the idea that the whole of something must be considered in order to understand its different parts” - Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

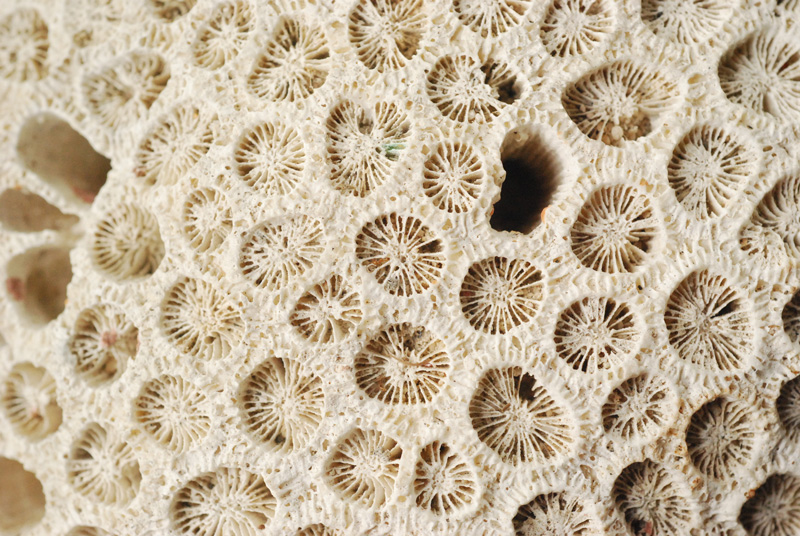

While clearly defined by man, Holism is by no means a thought construct of man. Nature exemplifies and dictates holism to us; every part needs the whole and the whole needs every part. Balance, cooperation, symbiosis and synergy defines life. From animate and inanimate nature to ecosystems, physiology of organisms to climate or social interactions - every single piece of a system affects the others and the whole.

This complexity becomes particularly clear when we consider the big challenges of today. The major challenges humanity is facing are on a global scale. If we look at climate change, for example, we often think of industry and mobility. The fires in the Amazon rainforest? The (majorly illegal) deforestation of the rainforest for the cultivation of palm oil or soy and loss of biodiversity? Corruption, the displacement of the local population or conflicts with indigenous groups? All of these aspects are also defined as climate change.

It’s not possible to break the world down into its components. Whether it is climate change, mass poverty or mass extinction – there are no simple solutions to global crises. Holistic thinking makes us realise the complexity of all of the issues we face. It aims to help us to identify different perspectives and needs. Furthermore, it helps us to develop and create long-term solutions for these global challenges. Creativity, interdisciplinarity, participation and collaboration are important prerequisites to try to achieve this.

The United Nations established a plan of action for sustainable development, known as the 2030 Agenda , and is an example of a holistic approach to multilateral sustainability policy. The agenda is based on the three dimensions model of sustainability: economy, society and the environment, which are interrelated. The Agenda is broken down into Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) , which are considered universal and apply equally to all countries when striving for a balance between the three dimensions.

Holistic thinking is the prerequisite to the 2030 Agenda and is a necessary consequence of the cooperation between all countries working towards the SDGs. It’s the key to tackling our global challenges.

WeFuture Global’s guide to holistic thinking

Many people have learned to solve a problem where it appears visibly and tangibly for everyone. While this approach may well lead to initial successes – these are not long-lasting, since the core of the problem is often hidden at first glance.

For example, In order to contribute to the fight against climate change by reducing carbon emissions, it makes sense to use the bicycle more often than a car. But, if we really want to make a difference, we should look further than just at one piece of the puzzle and adopt a holistic approach. This can be done in many ways, such as questioning our own consumption in all areas of life (not just with personal transportation), taking a look at the sustainable practices implemented on other sides of the globe, and increasing the pressure on businesses and politicians to implement sustainable practices, to name a few.

Looking at the details is not wrong – but it’s not enough either. Holistic thinking goes beyond, it means breaking free from your mindset. This requires awareness, consideration and communication. But how to put this into practice?

To assist our community in developing this important skill, we have developed the WeFuture Global guideline to help our community think holistically.

The WeFuture Global Guideline to Holistic Thinking

Step 1. awareness.

- First, take a step back from what you are doing.

- Change your perspective from detail-oriented to the whole.

- Define the exact problems / challenges.

- Define the overall objective / the end-goal.

Step 2. Consideration

- Consider and define the individual parts of the overall system.

- Look for recurring patterns and interfaces.

- See how the interfaces affect the overall objective.

- Define your role in the overall system.

- Search for the lever (area or action) with the greatest impact.

Step 3. Communication

- Showcase the importance of the single to all partners in the system.

- Facilitate and implement new and stronger relationships.

Holistic thinking is a continuous process of changing perspectives, brainstorming and critical questioning. By that, it forms the basis for decisions on concrete action and next steps.

It is of fundamental importance to identify the real problem first. It is worthwhile to pause and get an overall view: Look at the whole instead of single details, push comprehension instead of actionism and focus on strategic thinking instead of operational hectic. By looking closely at the interrelationships, the system's biggest levers can be identified. And only those will affect a real change. During the entire process, it is always important to critically question the solution statements and yourself.

Holistic World Conservation

The holistic approach makes us realize that we humans ourselves are a part of the whole. It not only makes each of us responsible but also empowers us to make a difference. Just like in a huge ecosystem, everyone and everything can understand that the overall result is bigger than individual contributions. Holistic thinking is the core of world conservation.

To solve interrelated problems, we need to work together. Individuals, civil society organizations and the private sector are indispensable for the success of world conservation as innovation can and does arise from the collaboration of these entities. If we want to change a system, we need to work on all levels. Therefore we need a strong network of symbiotic relationships, varying expertise and sector access. We need to identify the right problems, understand the connections, and each of us needs to be aware of our role in complex challenges.

Through the holistic thinking approach, we can lose the fear of complexity and be empowered to make a difference. By understanding that the whole is more than the sum of the parts, we can learn to look at problems differently and change perspectives, allowing us and our way of thinking to evolve. The holistic way of thinking can transform our lives as we question our attitudes and gain inspiration to break out of recurring patterns in our everyday life. And by collaborating with all members and groups within society, we can innovate sustainable solutions that contribute to impactful world conservation.

Be open to change. Strive for balance. Think beyond.

To become a part of the change, see all the ways that you can contribute to wefuture global..

Related posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Rethinking the Individualism-Holism Debate: Essays in the Philosophy of Social Science

Julie Zahle and Finn Collin (eds.), Rethinking the Individualism-Holism Debate: Essays in the Philosophy of Social Science, Springer, 2014, 255pp., $129.00 (hbk), ISBN 9783319053431.

Reviewed by Phillip Honenberger, Philadelphia Area Center for History of Science

Are social phenomena better explained in terms of the characteristics of individual human beings, or in terms of the characteristics of groups or collectives? Are all social-level entities and events identical to some set of individual-level entities and events, or are social-level entities and events ever "more than the sum" of their individual-level parts? Traditionally, those who opt for the first of these options are called "individualists," while those who opt for the second are called "holists." The present collection of essays by contemporary philosophers of social science provides a state-of-the-art introduction to recent moves in the long-standing debate between adherents of these positions, as well as recent thinking about related questions, such as the definition of and distinction between the individual and the social; the meaning and validity of the idea of higher and lower levels of composition; the understanding of individual agency, including discussion of rational choice and game theory, as well as new pragmatist and ecological models; whether and in what sense groups can be agents; and how explanation in the social sciences ought to be understood and evaluated. The volume includes essays both from veteran philosophers of social science (Daniel Little, Philip Pettit, Harold Kincaid, and Mark Risjord) and early and mid-career contributors to the field (Julie Zahle, Finn Collin, Brian Epstein, Dave Elder-Vass, András Szigeti, Petri Ylikoski, Jeroen Van Bouwel, Mathew McCubbins, and Mark Turner).

The modern holism-individualism debate has its origins in the formative development of modern social science itself, in the work (for instance) of G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Auguste Comte, and Herbert Spencer. The tension played out in an especially influential way in two widely publicized controversies: the debate between Émile Durkheim and Gabriel Tarde regarding "social facts," and F. A. Hayek's and Karl Popper's attacks on the "holism" of various mid-20 th -century social science traditions (Lukes 1968, 1973; Zahle 2007). Following upon these debates, discussion of the issue appeared in a number of academic journals in philosophy and sociology. This literature fed into the professional canon of Anglophone "philosophy of social science," a field coming close to its contemporary shape in the 1950s-1980s. This era saw the emergence of debates about the reducibility of the social to the individual, as well as about the putative need for mechanism-based explanations of social phenomena, in the social sciences (see Zahle 2007 for review). It is the later, professionalized phases of the debate to which the new volume seeks to make a contribution. Probably the most advanced discussion of its theme on the academic market today, this collection also provides an excellent introduction to many themes in contemporary analytic philosophy of social science in general. Nonetheless, the book displays some weaknesses. In what follows I first recount and discuss the contents of the essays individually, then briefly discuss one weakness of the volume as a whole.

The editors organize the papers into two groups: those focused on the ontology of individuals and societies, and those focused on questions of social science methodology (especially theories of explanation). In accordance with this breakdown, they summarize the main questions of the volume as follows: "[1] What is the ontological status of social phenomena and, as part of this, their relationship to individuals? [2] To what extent may, and should, social scientific explanations focus on individuals and social phenomena respectively?" (1-2). While this is a perfectly reasonable way of organizing the papers, I will discuss the papers in a slightly different order here, to suggest another way of thinking about them.

Two useful observations that emerge from a number of papers in the volume are, first, that what counts as an "individualist" or "holist" account is itself a contested matter; and, second, that some self-ascribed "holist" accounts take forms very similar or even consistent with what other authors describe as "individual" accounts, and vice versa. These observations motivate efforts to carefully distinguish among the positions that have been called "individualist" or "holist," so as to effectively track the actual theoretical consequences of, and arguments for and against, one or another position within this variety. Though the precise distinctions are often drawn slightly differently from one essay to the next, a few of the more common and important distinctions are those between

(a) the question of whether or not individuals are socially constituted (b) the question of whether or not individuals are socially constrained (c) the question of whether or not social-level entities and events are reducible to individual-level entities and events (d) the question of whether or not social entities (groups, etc.) can be agents (e) ontological vs. methodological formulations of the distinction

Some individualists have given a "yes" answer to (a), while giving a "no" answer to (b) and/or (c). (See Pettit, Little, and discussion by Zahle.) Methodological holists, however, often suppose that a "yes" answer to (a) is itself a concession to holism (Elder-Vass). This disagreement is partly merely terminological, but also potentially substantive. Another disagreement concerns whether a "yes" answer to (d) entails a "yes" answer to (b), with Pettit arguing that it does not, and Szigeti arguing that it does. Epstein's essay articulates and defends a variety of individualism that does not hold social phenomena to be "built" out of individuals (as individualist accounts usually do), but rather to be "anchored" in beliefs or practices common to individuals in the group. Epstein offers David Hume's "conventions" and John Searle's "institutional facts" as examples. Epstein's analysis of the structure of various possible anchoring relations, and their implications for the individualism-holism debate, deserves more attention than I can give it here. The essay leaves me wondering, however, when and how individual beliefs or practices become common enough to count as "social" on an anchor individualist account; how the identity of social facts is to be determined under conditions of change or breakdown in these facts; and what justifies the correlation between individual facts and social facts that one or another anchor individualist answer to these questions would (seemingly) have to draw. As an alternative to familiar "levels-based" views of micro-macro relations, Ylikoski suggests a "scale-based" view wherein we address micro-macro distinctions (including the distinction between individuals and social wholes) in terms of the size of the entities appealed to within an account or explanation. Human individuals are physically smaller than groups and societies, for instance. Two interesting consequences of the shift that Ylikoski recommends are (i) a reconstrual of the micro-macro relation as context-relative (thus eliding problems regarding the specification of a "lowest level") and (ii) recognition of cases wherein relatively small ("micro") events can have effects on relatively large ("macro") systems, and vice versa: the mosquito that initiates an outbreak of yellow fever, for instance, or the effect of U.S. tax policy on the investment decisions of an individual taxpayer. Ylikoski's analysis is elegant and brilliant. Because "levels-based" thinking is (admittedly confusingly) also associated with other distinctions, however -- such as the greater or lesser generality of claims made at different levels -- I suggest that levels-based discourse ought not be thrown out too callously. Pettit's essay provides a usefully condensed recapitulation of arguments he has presented elsewhere in more detail. Pettit distinguishes three different controversial positions relevant to the "individualism-holism" question: "individualism," the view that social phenomena do not compromise individual agency; "atomism," the view that social properties are not part of the constitution of individual agents; and "singularism," the view that only single individuals, and not groups or collectives, can be agents. Pettit argues for individualism, anti-atomism, and anti-singularism. Szigeti takes issue with Pettit's view, arguing that individualism and anti-singularism are incompatible (113-114). In brief, Szigeti's argument is as follows: Theories of group agency must be causal or non-causal. Causal construals have the result that either (a) group-agency reduces to individual agency, or (b) group agency constrains individual agency. Non-causal construals of group agency, on the other hand, are hard to read as attributions of agency at all (since agency presumably involves the ability to have effects). While Szigeti's subtle arguments deserve fuller discussion, I suspect they rely on questionable assumptions about the uniformity of the structure of causality in different kinds of systems or processes (or, in different contexts of explanation).

Another major theme of the book concerns the relation between ontological and methodological conceptions of the individualism-holism debate, with some authors drawing methodological conclusions from ontological premises, and others arguing for a wholesale shift of the debate away from ontology and towards methodology. Elder-Vass argues in favor of holism over individualism on the basis of a relatively straightforward two-step argument: (1) an account of the ontology of individuals and social phenomena, and (2) an argument that certain relations of individuals can and will produce social phenomena that are not reducible to the features of those individuals and their relations. In (1), Elder-Vass takes care to argue that no features ascribed to "individuals" can be due to relations with other individuals, since, if they were, these "individuals" would have been already admitted to be socially constituted (and, hence, the methodological individualists would have lost from the outset). In (2), Elder-Vass argues that there are obviously social phenomena that cannot be articulated solely in terms of the so-delimited features of individuals. Hence, methodological individualism is a failure. Elder-Vass also introduces the notion of "norm circles" (which he has employed in more detail elsewhere) and gives an account of their (non-individualistically-reducible) causal powers. Zahle takes issue with Elder-Vass's argument, claiming that step (1) need not convince individualists. In particular, they will see no compelling reason to deny themselves a definition of "individuals" that holds them to be socially constituted (as noted above, this is a move made by several contemporary individualists: for instance, Little and Pettit). Zahle recommends an alternative to Elder-Vass's "ontological" criterion for evaluating the individualism-holism distinction, which she calls a "pragmatic" criterion, and formulates it as follows:

a good reason in support of a particular distinction between individualist and holist explanations . . . is a reason which shows, in an acceptable manner, that the distinction, drawn in the same manner in all contexts, is useful from the perspective of explaining the social world. (192)

I'm suspicious of the requirement that the distinction be "drawn in the same manner in all contexts." On what grounds should we insist on this? Maybe there are a variety of different distinctions that are conflated within traditional "holism-individualism" distinctions, but nonetheless each has independent validity. I'm also unsure about the terms "acceptable" and "useful," at least so far as they've been clarified and argued for here. Kincaid argues that some of the issues classified under the "individualism-holism" debate are dead (no longer interesting or fruitful), while others are live (interesting and fruitful). The former category includes (i) the question of the reducibility of social-level phenomena to individual-level phenomena, (ii) the question of whether appeal to individual-level mechanisms is necessary in order to adequately explain social-level phenomena (the so-called "micro-foundations" debate), and (iii) the question of whether or not society is a fiction. The live issues are focused on the question, "how holist or individualist can or must we be?" (147), in regard to puzzles that arise within one or another project of empirical social scientific research. Van Bouwel articulates and defends a model of explanation in the social sciences that is amenable to explanatory pluralism, and then argues for a move from ontological and monist construals of the individualism-holism debate, to a position that advances "explanatory pluralism" (161).

Another theme that runs through the volume in a strong way is the question of which models of individual agency would be sufficient or insufficient, illuminating or unilluminating, within social scientific inquiry. Nuanced discussions of pragmatist (Little), practice-theoretic (Risjord), ecological (Risjord), actor-network (Collin), and game-theoretic (Little, Risjord, McCubbins and Turner) models of individual agency provide a surprising and refreshing subsidiary theme of the volume. Little seeks to supplement his earlier work on individualism and micro-foundations by developing a sufficiently robust account of the agents making up the "individual level" in social explanations. To this end he provides a critical review of pragmatist models of agency and their sociological application -- in particular, work by John Dewey, G. H. Mead, Neil Gross, Andrew Abbott, Mark Granovetter, and Hans Joas. These models are contrasted with Aristotelian and rational-choice models. From this comparative perspective, the novelties and advantages of the various pragmatist options come into relief very nicely, but the limited scope of the contrast class may be partly responsible for the attractiveness and apparent novelty of the pragmatist positions. Collin reconstructs Bruno Latour's intellectual trajectory through the lens of the individualism-holism debate, including Latour's early-career ethnographies of science, his mid-career articulation of a metaphysics of "actants," and his late-career methodological reflections on actor-network-theory as a framework for social scientific research. Collin's main aim is to say to what extent and in what ways Latour has been a methodological individualist or holist at different points in his career, and what lessons we can draw, regarding this opposition, from his contributions and difficulties. Of course, this strategy involves reading Latour in terms of problems and questions he might not himself recognize as the central ones, but Collin mostly handles the risks associated with this procedure very effectively. Risjord provides an argument for a new "ecological" model of agency, wherein "to be an agent requires treating others as agents and responding to the joint possibilities for action provided by the environment" (219). Risjord begins with an analysis of the behavior of musicians in a jazz ensemble. He then argues that two common accounts of agency -- rational actor and practice-theoretic (the latter represented by Pierre Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens) -- cannot make sense of this behavior. Finally, he proposes an alternative model of agency that recognizes the characteristically human capacities of (a) recognizing environmental affordances in one's own case, (b) recognizing the affordances of other agents with whom one is in interaction, (c) thus being able to imaginatively trade roles with them and share a common "attunement" to a shared environment, and (d) being able to "meta-cognitively" reflect on "prior plans, explicit beliefs about the environment, knowledge of explicit rules, and interpretations" (234). This model's advantage over Bourdieu's and Giddens's accounts is that it is able to explain the possibility of change, including breakdowns and subsequent recoveries, of the coordinated action of groups of individuals. Its advantage over rational actor models is in sufficiently recognizing the role of the environment (broadly construed), rather than solely the representational states of the agents involved, in coordinated group action. McCubbins and Turner provide an experimentally-based argument against a variant on traditional game theory known as "behavioral game theory." As the behavioral expectations of traditional game theory have regularly been disconfirmed, behavioral game theory seeks to develop empirically-based qualifications of game-theoretic predictions and models. McCubbins and Turner point out that behavioral game theory's strategy relies on the assumption that individual preferences can be generalized from one context to others; they then report on new experiments supporting the conclusion that such preferences do not generalize.

Despite its many strengths, the book manifests some weaknesses. I will discuss just one of these here. The traditional opposition between social wholes and individuals rings a bit hollow to contemporary ears, not only because the poles of the opposition are only vaguely or ambiguously conceived, nor solely because one suspects that they are hardly mutually exclusive, but also because this opposition doesn't include, within the scope of potentially relevant factors it considers, those that are non-human or sub-personal (such as, for instance, human biology, ecology, and artifacts and technology). What happens in human affairs is very plausibly constrained, enabled, and affected by a combination of factors classifiable as ecological, biological, and technological, in addition to "individual" and "social." Since the first three kinds of factors operate in ways that cross-cut the individual-social distinction, and (on some conceptions of the individual or the social) are not included within the framework of that distinction at all, the inherited individualism-holism opposition, and the traditional question of the reducibility or non-reducibility of the social to the individual, are problematic in a way that most contributors to the volume never address. (A common pattern in the volume is to mention such factors as possibly relevant, but not to discuss them in any detail: for instance, regarding artifacts, pp. 58, 121-122, 143, 145-146, 212; regarding sub-personal factors, p. 150.) To some extent, Risjord's and Collin's essays, and a few paragraphs of McCubbins and Turner's (240), are a refreshing exception to this general criticism. For examples of alternative approaches to the relation between the individual and the social, which do not pass quietly over such sub-personal and non-human factors, see John Protevi's analysis of the relation between somatic, technological, and social processes "below," "alongside," and "above" the subject (respectively), in Protevi 2009 and 2013; Lenny Moss and Vida Pavesich's analysis of differential access to embodied skill-formation in Moss and Pavesich 2011; and Moss's critique of methodological individualism on the basis of a reconstruction of human evolutionary history (Moss 2014), which also points to the role of sub-personal social processes in the constitution of human individuality. REFERENCES Lukes, Steven. 1968. "Methodological Individualism Reconsidered." The British Journal of Sociology , Vol. 19 (2): 119-129. Lukes, Steven. 1973. Émile Durkheim, his Life and Work: A Historical and Critical Study . London, UK: Penguin. Moss, Lenny, and Pavesich, Vida. 2011. "Science, Normativity, and Skill: Reviewing and Renewing the Anthropological Basis of Critical Theory." Philosophy and Social Criticism 37 (2): 139-165. Moss, Lenny. 2014. "Detachment and Compensation: Groundwork for a Metaphysics of 'Biosocial Becoming'." Philosophy and Social Criticism , 40 (1): 91-105. Protevi, John. 2009. Political Affect: Connecting the Social and the Somatic . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Protevi, John. 2013. Life, War, Earth: Deleuze and the Sciences . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Zahle, Julie. 2007. "Holism and Supervenience." In Stephen P. Turner and Mark Risjord (eds.), Philosophy of Anthropology and Sociology . Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier, pp. 311-341.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Holism?

How psychologists use holism to understand behavior

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Laura Porter

- In Psychology

In psychology, holism is an approach to understanding the human mind and behavior that focuses on looking at things as a whole. It is often contrasted with reductionism , which instead tries to break things down into their smallest parts. This approach suggests that we can only understand the parts when we view them in relation to the whole.

Overview of Holism

In terms of psychology, the holistic view suggests that it is important to view the mind as a unit, rather than trying to break it down into its individual parts. Each individual part plays its own important role, but it also works within an integrated system.

The basic principle of holism is that people are more than simply the sum of their parts. In order to understand how people think, the holistic perspective stresses that you need to do more than simply focus on how each individual component functions in isolation. Instead, psychologists who take this approach believe that it is more important to look at how all the parts work together.

Holism in Psychology

As an approach to understanding systems, holism is used in psychology as well as in other areas including medicine, philosophy, ecology, and economics. One key phrase that summarizes the key idea behind the holistic approach is that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

The field of holistic medicine, for example, focuses on treating all aspects of a person's health including physical symptoms, psychological factors, and societal influences.

In order to understand why people do the things they do and think the way they think, holism proposes that it is necessary to look at the entire person. Rather than focus on just one aspect of the problem, it is necessary to recognize that various factors interact and influence each other.

One reason why it is so important to consider the entire being is that the whole may possess emergent properties . These are qualities or characteristics that are present in the whole but cannot be observed by looking at the individual pieces.

Consider the human brain, for example. The brain contains millions of neurons , but just looking at each individual neuron will not tell you what the brain can do. It is only by looking at the brain holistically, by looking at how all the pieces work together, that you can see how messages are transmitted, how memories are stored, and how decisions are made.

Even looking at other aspects of the brain such as the individual structures does not really tell the whole story. It is only when taking a more holistic approach that we are truly able to appreciate how all the pieces work together.

In fact, one of the earliest debates in the field of neurology centered on whether the brain was homogeneous and could not be broken down further (holism) or whether certain functions were localized in specific cortical areas (reductionism).

Today, researchers recognize that certain parts of the brain act in specific ways, but these individual parts interact and work together to create and influence different functions.

Uses for Holism

When looking at questions in psychology, researchers might take a holistic approach by considering how different factors work together and interact to influence the entire person. At the broadest level, holism would look at every single influence that might impact behavior or functioning.

A humanistic psychologist, for example, might consider an individual's environment (including where they live and work), their social connections (including friends, family, and co-workers), their background (including childhood experiences and educational level), and physical health (including current wellness and stress levels).

The goal of this level of analysis is to be able to not only consider how each of these variables might impact overall well-being but to also see how these factors interact and influence one another.

In other cases, holism might be a bit more focused. Social psychologists, for example, strive to understand how and why groups behave as they do. Sometimes groups react differently than individuals do, so looking at group behavior more holistically allows research to assess emergent properties that might be present.

Benefits of Holism

Just like the reductionist approach to psychology, holism has both advantages and disadvantages. For example, holism can be helpful at times when looking at the big picture allows the psychologist to see things they might have otherwise missed. In other cases, however, focusing on the whole might cause them to overlook some of the finer details.

Some of the key benefits of this perspective include:

It Incorporates Many Factors

One of the big advantages of the holistic approach is that it allows researchers to assess multiple factors that might contribute to a psychological problem. Rather than simply focusing on one small part of an issue, researchers can instead look at all of the elements that may play a role.

This approach can ultimately help them find solutions that address all of the contributing internal and external factors that might be influencing the health of an individual. This is sometimes more effective than addressing smaller components individually.

By looking at people holistically, health care providers can address all of the many factors that might affect how a person is feeling, including their mind, their body, and their environment.

It Looks at the Big Picture

When researching a topic, it's frequently helpful to step back and look at the big picture. Reductionism tends to focus solely on the trees, but holism allows psychologists to view the entire forest. This can be true of both the research and treatment of mental health issues.

When trying to help a client with symptoms of a psychiatric condition, for example, looking at the patient holistically allows mental health professionals to see all of the factors that affect the patient’s daily life, and also how the patient interacts with their environment. Using this type of approach, therapists are often better able to address individual symptoms.

Human behavior is complex, so explaining it often requires an approach that is able to account for this complexity. Holism allows researchers to provide a fully inclusive answer to difficult questions about how people think, feel, and behave.

Drawbacks of Holism

While holism has a number of key advantages, there are also some important drawbacks to consider. Some of these include:

It Tends to Be Non-Specific

When trying to solve a problem, it is often important to focus on a particular aspect of the issue in order to come up with a solution. Holism tends to be more generalized, which can sometimes make precision more difficult. Scientists, in particular, must be able to focus their research on clearly defined variables and hypotheses.

Looking at something too broadly can make it difficult to conduct tests using the scientific method, largely due to the fact that it incorporates so many varied factors and influences.

It Can Be Overly Complex

Because holism is so all-inclusive, it can make scientific investigations very challenging and complex. There may be many different variables to account for, as well as a plethora of potential interactions. This can make this approach unwieldy at times.

Examples of Holism

There are a number of examples in the field of psychology of how holism can be used to view the human mind and behavior. The early schools of thought, structuralism and functionalism , are good examples of reductionist and holistic views.

Structuralism focused on breaking down elements of behavior into their smallest possible components (reductionism), whereas functionalism focused on looking at things as a whole and considering the actual purpose and function of behaviors (holism).

Throughout history, there have been other perspectives and branches of psychology that have also taken a holistic approach.

Gestalt Psychology

Gestalt psychology is a school of thought that is rooted in holism. The Gestalt psychologists not only believed that human behavior needed to be viewed as a whole; they also worked to understand how the human mind itself uses a holistic approach to make sense of the world.

The Gestalt laws of perceptual organization , demonstrate that the ways in which individual items relate to one another can influence how we see them. When similar items are viewed together, the law of similarity, for example, suggests that people will perceive them as components of a whole.

This approach can also be applied to the treatment of mental health problems. Gestalt therapy is a person-centered approach to treatment that emerged from the Gestalt school of thought. Rather than breaking down aspects of a person's past to understand their current problem, this approach to therapy looks at all aspects of the individual's life in the here and now.

Humanistic Psychology

Humanistic psychology is a branch of psychology that emerged in the 1950s partially as a response to behaviorism. Where behaviorism had taken a reductionist approach to explain human behavior, humanist thinkers are more interested in looking at behavior holistically.

This approach to psychology looks at all of the factors that contribute to how people think and act, as well as how all of these different components interact.

Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs is one example of a humanistic theory that takes a holistic look at human motivation. This theory doesn't focus on any single aspect of motivation. Instead, it incorporates many aspects including environmental, social, and emotional influences.

Social Psychology

Social psychology tends to take a holistic approach since it considers individuals in their social context. In particular, this branch of psychology looks at how group behavior is often different than individual behavior, which is a good example of emergent properties and the sum being more than its parts.

Holism vs. Reductionism

One way to look at how holism and reductionism are used is to observe how these approaches might be applied when studying a specific psychological problem.

Imagine that researchers are interested in learning more about depression .

- A researcher using the holistic approach might instead focus on understanding how different contributing factors might interact, such as examining how thought patterns, social relationships, and neurotransmitter levels influence a person’s depression levels.

- A scientist using the reductionist approach might look at a highly specific factor that influences depression, such as neurotransmitter levels in the brain.

A Word From Verywell

Much of the appeal of holism lies in its ability to incorporate all of the elements that make us who we are. People are infinitely complex and varied, and holism is able to address all of the external and internal factors that influence our past, present, and future.

Different areas of psychology often tend to focus on either one approach or the other. While reductionism and holism are often pitted against one another, they both serve an important role in helping researchers better understand human psychology.

Michaelson V, Pickett W, King N, Davison C. Testing the theory of holism: A study of family systems and adolescent health . Prev Med Rep . 2016;4:313–319. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.07.002

Freeman J. Towards a definition of holism . Br J Gen Pract . 2005;55(511):154–155.

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Humanistic perspective .

APA Dictionary of Psychology. Gestalt psychology .

Goodwin, CJ. A History of Modern Psychology, 5th Edition. New York: Wiley.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Methodological Holism in the Social Sciences

The debate between methodological holists and methodological individualists concerns the proper focus of explanations in the social sciences: to what extent should social scientific explanations revolve around social phenomena and individuals, respectively? The discussion takes two main forms.

The most enduring debate surrounds the issue of dispensability. Methodological holists engaged in this debate defend the view that explanations that invoke social phenomena (e.g., institutions, social structures or cultures) should be offered within the social sciences: their use is indispensable. Explanations of this sort are variously referred to as holist, collectivist, social (-level), or macro (-level) explanations. They are exemplified by claims such as “the unions protested because the government wanted to lower the national minimum wage”, or “the rise in unemployment led to a higher crime rate”. Holist explanations may be contrasted with explanations that are expressed in terms of individuals, their actions, beliefs, desires, and the like. The latter are variously termed individualist, individual (-level), or micro (-level) explanations. They are illustrated by claims such as “Anna baked a cake because Susan wanted it”, or

as a result of individuals a , b , c , etc. losing their jobs, and feeling very frustrated about having little money and no job opportunities, the crime rate went up.

Methodological holists may or may not hold that individualist explanations should be offered in addition to holist explanations. Whatever methodological holists’ stand on this issue, they are opposed by methodological individualists who insist that individualist explanations alone should be provided within the social sciences, and thus, that holist explanations should be dispensed with.

The other, more recent dispute between methodological holists and individualists is concerned with the issue of microfoundations. Methodological holists involved in this debate defend the view that in some cases, purely holist explanations (i.e., explanations stated solely in terms of social phenomena) may stand on their own: they do not invariably need individual-level microfoundations. A purely holist explanation might be “the economic depression was the main reason why the war broke out”. Methodological holists may maintain that this explanation is fine as it stands; it need not be supplemented with further details specifying how the economic depression incited individuals to adopt certain beliefs, act in certain ways, etc., that in turn led to the outbreak of the war. Methodological individualists disagree, insisting that such additional accounts must always be provided.

Within philosophy and the social sciences, whether in the context of the dispensability or the microfoundations debate, proponents of methodological holism do not necessarily describe their position in such terms. In fact, this is seldom so within the social sciences. In certain cases, some alternative label is used, for example, when “explanatory holism” and “collectivism” are employed to denote the view that holist explanations are indispensable. In other cases, no label at all is attributed to one or both of the views that are here described as methodologically holist. In this entry, differences of terminology will be disregarded: the term “methodological holism” is used to describe both the thesis that holist explanations are indispensable, as well as the thesis that purely holist explanations do not always need individual-level microfoundations.

The methodological individualism-holism debate that concerns the proper focus of social scientific explanations is just one among several individualism-holism disputes. Most notably, there are individualism-holism debates about ontology, confirmation, and morality. Within these discussions, holism is the view that social phenomena exist sui generis , or in their own right (the ontological debate); that social scientific explanations need not always be confirmed by looking at what happens at the level of individuals (the debate on confirmation); and that moral responsibility may sometimes be ascribed to social entities such as groups (one version of the moral debate). It is perfectly possible, and in fact quite common, to subscribe to methodological holism in the sense defined in this entry without endorsing these other forms of holism. Though interesting, these debates will not be directly addressed here.

The following discussion of methodological holism consists of two parts. Sections 1 and 2 examine the dispensability debate, and Sections 3 and 4 consider the microfoundations debate. Both parts focus on methodological holists’ views—and arguments—in these disputes. For a characterization of methodological individualism, see the entry on methodological individualism .

1. The Dispensability Debate

2.1 the argument from social phenomena as causes, 2.2 the argument from the impossibility of translation, 2.3 the argument from the impossibility of intertheoretic reduction, 2.4 the argument from explanatory regress, 2.5 the argument from differing explanatory interests, 2.6 the argument from pragmatic concerns, 3. the microfoundations debate, 4.1 the argument from underlying social-level mechanisms, 4.2 the argument from mechanism regress, 4.3 the argument from explanatory practices, 4.4 the argument from non-mechanistic explanatory considerations, other internet resources, related entries.

The defense of methodological holism dates back to at least the turn of the nineteenth century. Around this time, Emile Durkheim advocated the indispensability of holist explanations in a number of writings (see e.g., Durkheim 1938[1895], 1951[1897]). He famously stated that the

determining cause of a social fact should be sought among the social facts preceding it and not among the states of the individual consciousness . (Durkheim 1938 [1895]: 110—italics in the original)

His work is typically juxtaposed to that of Max Weber, who is regarded as the main proponent of methodological individualism during this period. In the subsequent history of the debate, there are two phases that particularly stand out. The first began around the 1950s, when Friedrich Hayek, Karl Popper, and J.W.N. Watkins argued ardently in support of methodological individualism. In response, Ernest Gellner, Leon G. Goldstein, Maurice Mandelbaum, and others maintained that there were alternative ways of cashing out, and defending, methodological holism that were left unscathed by Hayek’s, Popper’s and Watkins’ objections (see Gellner 1973 [1956]; Goldstein 1973a [1956], 1973b [1958]; Mandelbaum 1955, 1973 [1957]. They all appear in O’Neill 1973, which also contains other important contributions from this period).

The second significant period stretches from around the 1980s up until today. From the perspective of methodological holism, this phase is marked by the appearance of a number of new, or new versions of, arguments in support of the indispensability of holist explanations. In this phase, seminal contributions to the dispensability debate were made by Roy Bhaskar, Alan Garfinkel, Harold Kincaid, Frank Jackson and Philip Pettit to mention just a few (see Bhaskar 1979; Garfinkel 1981; Kincaid 1996, 1997; Jackson and Pettit 1992a, 1992b). The following section focuses on the most important arguments advanced during this last—and still unfolding—period. (See Zahle and Collin 2014a for a collection of papers from this period.) The remainder of the present section is concerned with the further introduction of the positions at play within the dispensability debate. As noted above, special attention will be paid to the methodological holist stance.

There are three basic views within the debate:

Strong methodological holism : Holist explanations alone should be offered within the social sciences; they are indispensable. Individualist explanations may, and should, be dispensed with. Moderate methodological holism : In certain cases, holist explanations should be advanced; in other cases individualist explanations should be advanced; both holist and individualist explanations are indispensable within the social sciences. Methodological individualism : Individualist explanations alone should be put forward within the social sciences; they are indispensable. Holist explanations may, and should, be dispensed with.

Among these positions, the thesis of strong methodological holism has enjoyed relatively little support and today it has few, if any, proponents. The vast majority of methodological holists are of the moderate variety. Accordingly, the debate has mainly played itself out between the moderate holist view and the individualist position. Because both parties agree that individualist explanations should be advanced, their efforts have first and foremost been directed toward the question of whether holist explanations are indispensable or not.

The three basic positions may be further characterized in three ways. First, each relies on a distinction between holist and individualist explanations. This raises the issue of exactly how to differentiate between these two categories of explanation. The answer to this question is a matter of dispute among participants in the debate. One possible formulation of the distinction is that holist explanations appeal to social phenomena, whereas individualist explanations invoke individuals, their actions, beliefs, etc. To elaborate further on this suggestion, it may be specified that holist explanations contain social terms, descriptions, or predicates set apart by their reference to, and focus on, social phenomena. By contrast, individualist explanations contain individualist terms, descriptions, or predicates distinguished by their reference to, and focus on, individuals, their actions, beliefs, desires, etc.

One issue still left open by this supplementary characterization is how to understand the notion of a social phenomenon. Methodological holists commonly take the following list of items to exemplify social phenomena: (a) Organizations—like universities, firms, and churches; (b) social processes—like revolutions and economic growth; (c) statistical properties—like the literacy rate or the suicide rate within a group; (d) cultures and traditions—like the Mayan culture or a democratic tradition; (e) beliefs, desires, and other mental properties ascribed to groups—like the government’s desire to stay in power; (f) norms and rules—like the proscription of sex with family members and the rule requiring cars to drive on the right-hand side of the road; (g) properties of social networks—like their density or cohesion; (h) social structures, typically identified with one or more of the items already listed; and (i) social roles—like being a bus driver or a nurse. The list includes social phenomena in the form of social entities, social processes, and social properties. The latter are first and foremost properties ascribed to social groups or constellations of individuals. Yet social properties also include certain features ascribed to individuals, such as an individual’s social role. These properties are social properties, it is sometimes suggested, because they presuppose the social organization of individuals, or the existence of social entities. (For a discussion of different kinds of social properties, see also Ylikoski 2012, 2014.)

Methodological individualists typically disagree that all the items listed above constitute social phenomena. They contend that some exemplify individualist properties because they are properties of individuals. For instance, some methodological individualists maintain that norms and rules are individualist properties since they express individuals’ beliefs as to how they should—or should not—act. Likewise, many hold that social roles are individualist properties because they are ascribed to individuals. (For holist defenses of the view that social roles should be classified as social properties, see e.g., Kincaid 1997; Lukes 1968; Elder-Vass 2010; Hodgson 2007.) In this fashion, the dispute about how to distinguish between holist and individualist explanations translates into a difference in opinion concerning what constitutes social phenomena. Methodological holists consider more phenomena to be social and hence they classify more explanations as holist, whereas methodological individualists view fewer phenomena as social, the result being that they categorize fewer explanations as holist and more as individualist. Due to such disagreements, methodological holists and individualists often talk past one another: each offers arguments presupposing a distinction between holist and individualist explanations that is at odds with that relied upon by their opponent (see Zahle 2003, 2014).

The question of how to differentiate between holist and individualist explanations may also be approached by drawing on the analysis of explanations as consisting of an explanans, i.e., what does the explaining, and an explanandum, i.e., what is in need of explanation. Consider the following options: (a) both the explanans and the explanandum are expressed in terms of social phenomena (e.g., the government’s decision to lower the national minimum wage led to protests from the unions); (b) the explanans is stated in terms of social phenomena while the explanandum is described in terms of individuals, their actions, etc. (e.g., the government’s decision to lower the national minimum wage resulted in several individuals writing public letters of protest); (c) both the explanans and the explanandum are expressed in terms of individuals, their actions, etc. (e.g., because the small children started crying, a number of people came over to help out); (d) the explanans is stated in terms of individuals, their actions, etc. while the explanandum is described in terms of social phenomena (e.g., the fact that many individuals withdrew their money at once had the result that the bank exhausted its cash reserves). With these options in mind, three different ways of circumscribing holist and individualist explanations may be registered:

All three conceptions have been advocated in the dispensability debate. Among them, the first position is the most inclusive, while also being the most widespread.

Second, the basic positions of strong methodological holism, moderate methodological holism and methodological individualism can be further characterized by noting that holist and individualist explanations may be categorized into different types. For instance, both holist and individualist explanations may be classified according to whether they are functional, intentional, or straightforward causal explanations. This point may be illustrated in relation to holist explanations. Holist explanations of the functional variety state that the continued existence of a social phenomenon is explained by its function or effect. For instance, it may be suggested that “the state continues to exist because it furthers the interests of the ruling class”. In the past, but no longer today, methodological holism has often been associated with the advancement of holist explanations of this type. (On the use of functional holist explanations, see e.g., Macdonald and Pettit 1981: 131ff.) Intentional holist explanations purport to explain an action ascribed to a group by reference to the group’s reasons for performing it. For example, it may be affirmed that “the government decided to call a general election in May because it believed this would increase its chances of being reelected”. (On the use of intentional holist explanations, see e.g., Tollefsen 2002; List and Pettit 2011.) Nowadays, both functional and intentional explanations are often regarded as special kinds of causal explanation to be distinguished from more straightforward causal explanations. This latter kind of causal explanation is illustrated by assertions such as “the rise in unemployment led to an increase in crime”, or “the government’s lowering of the taxes led to an increase in the consumption of luxury goods”.

Alternatively, to note an additional example, holist and individualist explanations may be categorized by reference to their focus. In this spirit, holist explanations may be classified according to whether they focus on, say, the statistical properties of social groups, on social organizations and their actions, and so on. Likewise, individualist explanations may be categorized according to whether, say, their descriptions of individuals are informed by rational choice models, by accounts that stress how actions are largely habitual and based on various forms of tacit knowledge, etc. The advocacy of a basic position may go together with the favoring of certain types of holist or individualist explanations over others.

Third, the positions of strong methodological holism, moderate methodological holism and methodological individualism can be further explicated by observing that each stance may either be formulated as a claim about explanations in general, that is, all explanations advanced within the social sciences, or as pertaining to final explanations only, that is, explanations that are satisfactory rather than being merely tolerable in the absence of better ones. Sometimes methodological individualists tend to regard the discussion as revolving solely around final explanations. Accordingly, they maintain that though holist explanations may be advanced, they are only tolerable as stopping points that are temporarily acceptable in anticipation of individualist explanations that, alone, will qualify as final explanations. Among both strong and moderate methodological holists, it is less commonly maintained that the debate concerns final explanations only.

There are additional dimensions along which the three basic positions within the dispensability debate may be clarified. For instance, each stance is compatible with different views of what constitutes an explanation, different notions of causation, and so on. Occasionally, the divergence of opinion with respect to these issues will surface in the discussion that follows.

2. Why Holist Explanations are Indispensable

This section examines some of the most important arguments offered in support of the claim that holist explanations are indispensable within the social sciences. All the arguments have been advocated by moderate methodological holists. Only the first version of the first argument has also, and perhaps mainly, been propounded by strong methodological holists. The arguments should all be read as defenses of the indispensability of holist explanations understood as final explanations.

The argument from social phenomena as causes takes it that holist explanations are indispensable if social phenomena are causally effective. The basic structure of the argument is as follows. First, a characterization of social phenomena as causally effective is presented. Next, it is maintained that in order to explain the events generated by the causally effective social phenomena, holist explanations must be offered: holist explanations alone state how social phenomena bring about certain events. Lastly, it is concluded that since the events brought about by social phenomena should not be left unexplained, holist explanations are indispensable. The argument comes in various versions set apart by the way in which they characterize social phenomena as causally effective.

According to one line of reasoning, social entities like nations and societies have causal powers that are independent of, and override, the causal powers of the individuals who comprise these entities. For instance, it is held that nations develop in such a way so as to realize some goal, yet without the implicated individuals having any influence on this development. Alternatively, it is contended that societal structures may ensure that individuals perform certain functions in society; the individuals have no choice in this matter. However specified, social phenomena that have these independent and overriding causal powers produce effects that cannot be accounted for by offering individualist explanations; individuals are simply not causally responsible for these effects. The explanation of such social phenomena is only possible by way of holist explanations that lay out how the phenomena brought about the effects in question.

The contention that social entities have independent and overriding causal powers is often ascribed to Comte, Hegel, Marx, and their followers. Today the claim enjoys very few adherents. One important reason for this is that the claim is regarded as incompatible with the widely held view that social phenomena are noncausally determined by individuals and their properties, and sometimes by material artifacts too. Particularly since the 1980s, the notions of supervenience, realization, and emergence have received a lot of attention as ways of spelling out this non-causal dependency relation between social phenomena, on the one hand, and individuals and their properties, on the other. These notions have served as the basis for alternative versions of the argument from social phenomena as causes.

Consider first the notions of supervenience and realization. Supervenience is a relationship between properties, kinds, or facts. Roughly speaking, social properties supervene upon individualist properties if and only if there can be no change at the level of social properties unless there is also a change at the level of individualist properties. Otherwise put, the individualist properties fix the social properties. Too see how this works, assume that a football club supervenes on a constellation of individuals with certain beliefs, bearing certain relations to each other, and so on. This being the case, the football club cannot transform into a golf club, say, unless the individuals change some of their beliefs, the relations they stand in, or the like. The individuals’ beliefs, relations, etc. fix the property of their being a football club. The notion of supervenience is often used interchangeably with the notion of realization. Thus, it is said that a constellation of individuals with certain beliefs, relationships, etc. realizes the property of being a football club. Several moderate methodological holists have, in varying ways, expanded on the account of social properties as supervenient properties by presenting considerations in support of supervenient social properties being, in certain cases, causally effective properties (see e.g., Kincaid 1997, 2009; List and Spiekermann 2013; Sawyer 2003, 2005). Their reflections are a response to the so-called exclusion argument, which states that supervenient properties are epiphenomenal because all the causal work is done by the properties that they supervene upon (on this argument, see e.g., Kim 2005). Here is how Christian List and Kai Spiekermann purport to establish that some supervenient social properties are causally effective (List and Spiekermann 2013).

List and Spiekermann begin by appealing to the difference-making or counterfactual conception of causation, which asserts that “a property C (within a system of interest) is the cause of another property E if and only if C systematically makes a difference to E ” (2013: 636). By implication, a supervenient social property, S , qualifies as a cause of E , when S makes a systematic difference to E . This means that, other things being equal, if S occurred E would do so too, and that if S did not occur, then neither would E . Now assume that S is microrealization-robust: S would also have brought about E if it had been realized by a compound of individualist properties other than the one that actually realizes it. In situations of this sort, the compound of individualist properties that realizes S does not make a systematic difference to E . While it is the case that if the particular compound occurred then so would E , it is not the case that if the compound did not occur, E would not occur either. Hence it is S , rather than the compound of individualist properties realizing S , that qualifies as the cause of E . List and Spiekermann underline that in these circumstances, a holist explanation—that is, an explanation describing how a given supervenient social property brought about some effect—is needed.

As an anecdotal illustration of these points, they refer to the failed climate summit in Copenhagen in 2010 (2013: 637). They suggest that the summit failed at least in part because there were so many parties, and no common interest. Moreover, they note that these—and other—social properties of the situation are microrealization-robust: even had they been realized by individuals with somewhat different individualist properties, the social properties would have still resulted in a failed summit. The social properties of the meeting should thus be regarded as the cause of the failure; that is, a holist explanation must be offered in order to explain why the summit was unsuccessful.

Turn now to the notion of emergence. While emergent properties are sometimes regarded as identical to, or as a special class of, supervenient properties, emergent properties may also be differently characterized. These alternative specifications of social properties as emergent properties have similarly served as the basis for insisting that holist explanations are indispensable. Currently, this line of reasoning is often associated with the social scientific school of Critical Realism, founded by Roy Bhaskar and further developed by many others (see e.g., Archer 1995, 2000; Bhaskar 1979, 1982; Elder-Vass 2007, 2010, 2014). Main representatives of the movement have offered a variety of specifications of the notion of emergence. Among these, Dave Elder-Vass’ account will be briefly discussed.

According to Elder-Vass, social entities like firms and universities are composed of individuals (and sometimes material things as well) that stand in certain relations to one another (Elder-Vass 2007: 31). In virtue of being composed, at a given moment in time, of interrelated individuals, social entities have various causally effective social properties. Most notably, they have emergent social properties, of which there are two kinds. The first is constituted by emergent social properties that are ascribed to social entities as wholes. These are exemplified by a government’s power to introduce a new tax, or a quartet’s ability to deliver a harmonized performance. The second kind consists in emergent social properties that are ascribed to individuals. These are illustrated by a boss’s power to hire or fire employees. Individuals have these properties in virtue of being interrelated so as to form a social entity, and that’s why they constitute emergent social properties (Elder-Vass 2010: 74). Individuals who form part of social entities have non-emergent properties too. These are the causally effective properties, like the ability to read or talk, which individuals have independently of being, at a given moment in time, part of a social entity. From these reflections, Elder-Vass contends, it follows that holist explanations cannot be dispensed with. The effects of emergent social properties should be explained. To this end, it is necessary to offer holist explanations—that is, explanations that state how a social property partially brought about some effect. Individualist explanations are not up to this task inasmuch as they are confined to describing how individuals, in virtue of their non-emergent properties, partially brought about some effect. Simply pointing to the properties that individuals have independently of being, at a given moment in time, part of social entities, does not add up to an explanation of the effects of emergent social properties (see 2010: 66).

Contemporary moderate methodological holists largely agree that social phenomena are non-causally determined by individuals and their properties, and occasionally by material artifacts too. As illustrated in the foregoing, some defend the claim that thus conceived, social phenomena are causally effective, while such defenses often depend heavily on the particular notion of causation espoused. Many moderate methodological holists, however, see no need for arguments in support of social phenomena being causally effective. They simply assume this to be the case while pursuing alternative strategies in the attempt to establish that holist explanations are indispensable.

The argument from the impossibility of translation takes it that the indispensability of holist explanations is a matter of these explanations being untranslatable into individualist explanations. The argument begins by observing that holist explanations contain social descriptions or concepts, and goes on to note that the meaning of social descriptions cannot be captured by specifications that contain descriptions of individuals alone. Or, put otherwise, social concepts are not reductively definable solely in terms of individualist concepts. As a result, it is impossible to translate holist explanations into individualist ones: holist explanations cannot be replaced by individualist explanations through translation. Finally, the argument concludes that since the events accounted for by holist explanations should not go unexplained holist explanations are indispensable.

The argument from the impossibility of translation is famously presented by Maurice Mandelbaum in a paper from 1955 (Mandelbaum 1955). Here Mandelbaum defines social concepts as concepts that refer to forms of organization within a society. He remarks that concepts of this sort “cannot be translated into psychological [i.e., individualist] concepts without remainder ” (1955: 310—italics in the original). In order to drive this point home, Mandelbaum considers the social concept of a bank teller. In order to specify what a bank teller is, it is necessary to invoke the social concept of a bank. The definition of a “bank”, in turn, must contain social concepts such as “legal tender” and “contract”. And these social concepts, too, can only be defined in ways that involve yet other social concepts, such that the definition of a social concept inevitably contains other social concepts. Given that the distinctive feature of holist explanations is their very containment of social concepts, these explanations can thus not be translated into, and as such replaced by, individualist explanations.

Mandelbaum’s argument, including his example of the bank teller, is widely cited in subsequent contributions to the debate between moderate methodological holists and individualists (see e.g., Bhargava 1992; Danto 1973 [1962]; Epstein 2015; Gellner 1973 [1956]; Goldstein 1973b [1958]; James 1984; Kincaid 1986, 1997; Zahle 2003). However, few moderate methodological holists have followed Mandelbaum in holding that holist explanations are indispensable if they indeed cannot be translated into individualist explanations.

The argument from the impossibility of intertheoretic reduction presumes that holist explanations cannot be dispensed with if holist theories are irreducible to individualist ones. The argument rests on the view that holist explanations draw on social theories, whereas individualist explanations involve individualist theories. From within this context, it is argued that social theories are oftentimes irreducible to, and hence irreplaceable by, individualist theories. Accordingly, when holist explanations make use of irreducible social theories, they cannot be substituted by individualist explanations that appeal to individualist theories. Since the events that are explained by appeal to irreducible social theories should not go unexplained, holist explanations are therefore indispensable.