- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Taxation Without Representation

- History of Opposition

- In Modern Times

The Bottom Line

- Personal Finance

Taxation Without Representation: What It Means and History

Julia Kagan is a financial/consumer journalist and former senior editor, personal finance, of Investopedia.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Julia_Kagan_BW_web_ready-4-4e918378cc90496d84ee23642957234b.jpg)

Lea Uradu, J.D. is a Maryland State Registered Tax Preparer, State Certified Notary Public, Certified VITA Tax Preparer, IRS Annual Filing Season Program Participant, and Tax Writer.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/lea_uradu_updated_hs_121119-LeaUradu-7c54e49efe814a048e41278182ba02f8.jpg)

What Is Taxation Without Representation?

The phrase taxation without representation describes a populace that is required to pay taxes to a government authority without having any say in that government's policies. The term has its origin in a slogan of the American colonials against their British rulers: " Taxation without representation is tyranny."

Key Takeaways

- Taxation without representation was possibly the first slogan adopted by American colonists chafing under British rule.

- They objected to the imposition of taxes on colonists by a government that gave them no role in its policies.

- In the 21st century, the people of the District of Columbia are citizens who endure taxation without representation.

Investopedia / Candra Huff

History of Opposition to Taxation Without Representation

Although taxation without representation has been perpetrated in many cultures, the phrase came to the common lexicon during the 1700s in the American colonies. Opposition to taxation without representation was one of the primary causes of the American Revolution.

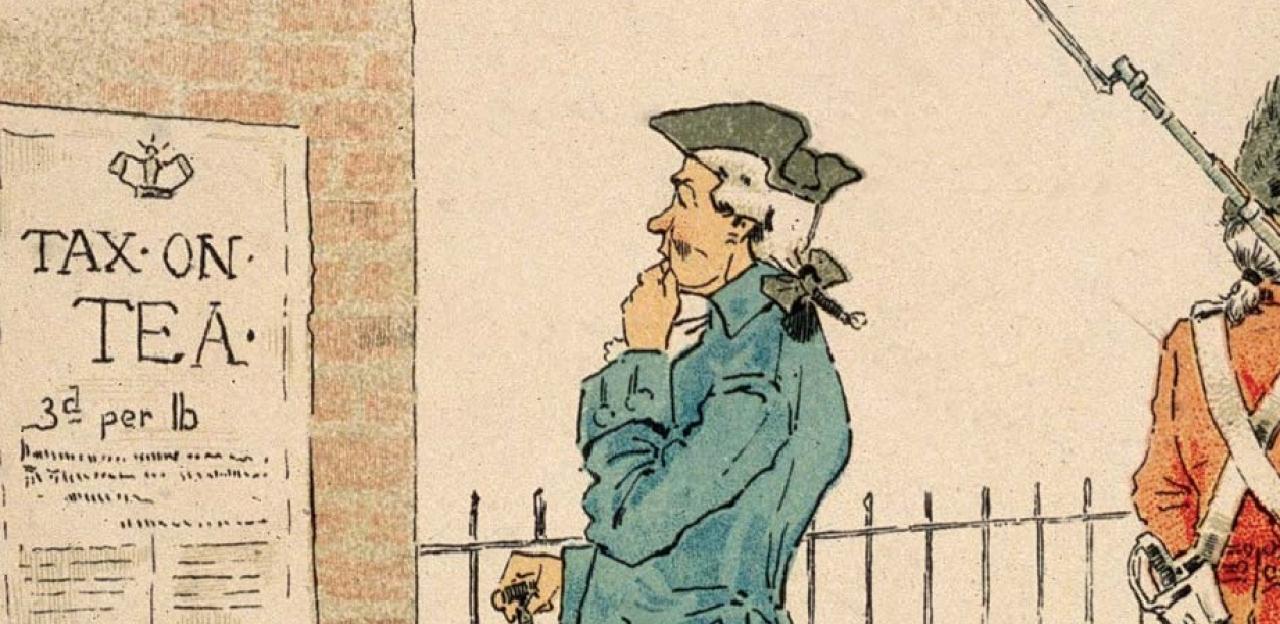

The Stamp Act Triggers Colonists

The British Parliament began taxing its American colonists directly in the 1760s, ostensibly to recoup losses incurred during the Seven Years’ War of 1754 to 1763.

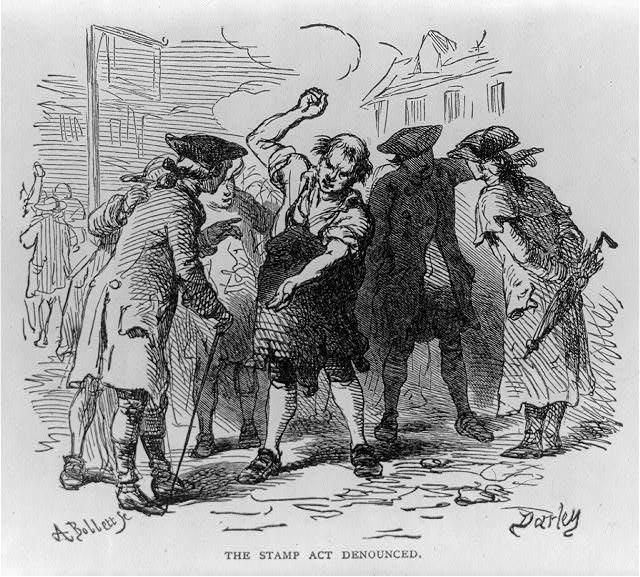

One particularly despised tax, imposed by the Stamp Act of 1765 , required colonial printers to pay a tax on documents used or created in the colonies and to prove it by affixing an embossed revenue stamp to the documents.

Violators were tried in vice-admiralty courts without a jury. The denial of a trial by peers was a second injury in the minds of colonists.

Revolt Against the Stamp Act

Colonists considered the tax to be illegal because they had no representation in the Parliament that passed it and were denied the right to a trial by a jury of their peers. Delegates from nine of the 13 colonies met in New York in October 1765 to form the Stamp Act Congress.

William Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, John Rutledge of South Carolina, and other prominent colonials met for 18 days.

They then approved a "Declaration of the Rights and Grievances of the Colonists," stating the delegates’ joint position for other colonists to read. Resolutions three, four, and five stressed the delegates’ loyalty to the crown while stating their objection to taxation without representation.

Trial Without a Jury

A later resolution disputed the use of admiralty courts that conducted trials without juries, citing a violation of the rights of all free Englishmen.

The Congress eventually drafted three petitions addressed to King George III, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons.

After the Stamp Act

The petitions were initially ignored, but boycotts of British imports and other financial pressures by the colonists finally led to the repeal of the Stamp Act in March 1766.

It was too late. After years of increasing tensions, the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775, with battles between American colonists and British soldiers in Lexington and Concord.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution to Congress declaring the 13 colonies free from British rule. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson were among the representatives chosen to word the resolution.

A Statement of Intent

The first part was a simple statement of intent, including the declaration that all men were created equal and have unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. A second section listed the colonists’ grievances and declared their determination to achieve independence. The final paragraph dissolved the colonists’ ties with Britain.

Following debate, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, with the signing occurring primarily on August 2, 1776.

Taxation Without Representation in Modern Times

Taxation without representation was by no means extinguished with the separation of the American colonies from Britain , not even in the U.S.

Residents of Puerto Rico, for example, are U.S. citizens but do not have the right to vote in presidential elections and have no voting representatives in the U.S. Congress (unless they move to one of the 50 states.)

In addition, the phrase taxation without representation appeared on license plates issued by the District of Columbia beginning in the year 2000. The addition of the slogan was meant to increase awareness of the fact that residents of the District pay federal taxes despite having no voting representation in Congress.

In 2017, the District's City Council added one word to the phrase. It now reads "End Taxation Without Representation."

Which Tax Triggered the Rebellion Against Great Britain?

The Stamp Act of 1765 angered many colonists as it taxed every paper document used in the colonies. It was the first tax that the crown had demanded specifically from American colonists.

Did Taxation Without Representation End After the American Revolution?

Yes and no. While the states in the newly formed country had representation, federal districts like Washington, D.C., and territories like Puerto Rico still lack the same representation on the federal level in the modern era.

Does Taxation Without Representation Refer to Local or Federal Government?

Today, the phrase refers to a lack of representation at the federal level. As an example, Puerto Rico has the same structure as a state, with mayors of cities and a governor, but instead of senators or representatives in Congress, they have a resident commissioner that represents the people in Washington, D.C. Puerto Ricans can only vote for president if they establish residency in the 50 states.

"Taxation without representation" refers to those taxes imposed on a population who doesn't have representation in the government. The slogan "No taxation without representation" was first adopted during the American Revolution by American colonists under British rule.

Today, the phrase refers to a lack of representation at the federal level, and only residents of D.C. and Puerto Rico are still taxed without representation.

National Constitution Center. " On This Day: 'No Taxation Without Representation!' "

Government of the District of Columbia. " Why Statehood for DC ."

United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. " French and Indian War/Seven Years’ War, 1754–63 ."

National Parks Service. " Britain Begins Taxing the Colonies: The Sugar & Stamp Acts ."

Library of Congress. " Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor - No Taxation Without Representation ."

University of Michigan Library. " Proceedings of the Congress at the New-York, Boston, 1765 ."

University of Michigan Library, Text Creation Partnership. " Proceedings of the Congress at New York - WEDNESDAY, October 23, 1765, A. M ."

University of Michigan Library, Text Creation Partnership. " Proceedings of the Congress at New York - TUESDAY, October 22, 1765, A. M ."

Yale Law School, The Avalon Project. " Great Britain: Parliament - An Act Repealing the Stamp Act; March 18, 1766 ."

American Battlefield Trust. " Lexington and Concord ."

National Archives. " Signers of the Declaration of Independence ."

Library of Congress. " Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents ."

National Archives. " Declaration of Independence: A Transcription ."

National Park Service. " The Second Continental Congress and the Declaration of Independence ."

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. " Voting Rights in US Territories ." Page 4.

National Archives. " Unratified Amendments: DC Voting Rights ."

Department of Motor Vehicles, District of Columbia. " End Taxation Without Representation Tags ."

Council of the District of Columbia. " B21-0708 - End Taxation Without Representation Amendment Act of 2016 ."

Library of Congress. " The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and its Government Structure ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1021333798-68ab46e559754c4bbd9c2e3778d8d331.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor No Taxation Without Representation

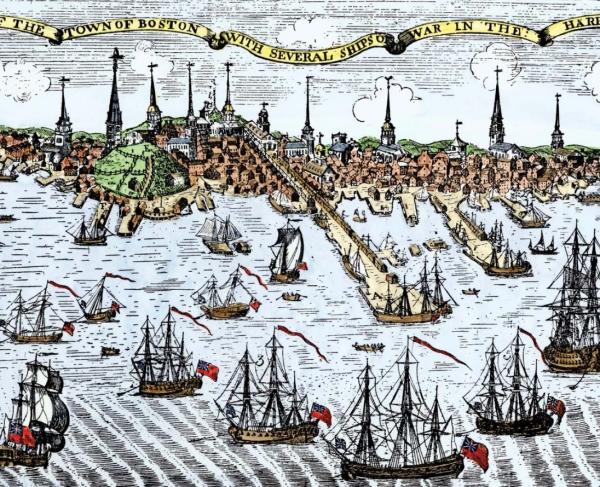

Paul Revere (1735–1818), engraver. A View of the Obelisk Erected under Liberty-Tree in Boston on the Rejoicings for the Repeal of the—Stamp Act 1766 . Boston, 1766. Hand-colored etching, restrike 1839 or later. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress

England’s Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) and its counterpart waged in America, the French and Indian War (1754–1763), doubled Britain’s national debt. In order to recoup some of the losses Britain incurred defending its American colonies, Parliament decided for the first time to tax the colonists directly. One such tax, the 1765 Stamp Act required all printed documents used or created in the colonies to bear an embossed revenue stamp. Stamp Act violations were to be tried in vice-admiralty courts because such courts operated without a jury.

Colonial assemblies denounced the law, claiming the tax was illegal on the grounds that they had no representation in Parliament. Colonists were likewise furious at being denied the right to a trial by jury. Many viewed the tax as an infringement of the rights of Englishmen, which contemporary opinion held to be enshrined in Magna Carta. Protests throughout the colonies threatened tax collectors with violence. Parliament finally bowed to pressure and repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766, but the colonial reaction set the stage for the American independence movement.

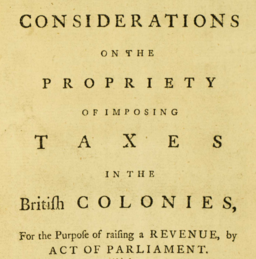

Declaration of Rights and Grievances

The Stamp Act of 1765, which Parliament imposed on the American colonies, placed a tax on paper, legal documents, and other commodities; limited trial by jury; and extended the jurisdiction of the vice-admiralty courts. The act generated intense, widespread opposition in America with its critics labeling it “taxation without representation” and a step toward “despotism.” At the suggestion of the Massachusetts Assembly, delegates from nine of the thirteen American colonies met in New York in October 1765. Six delegates, including Williams Samuel Johnson (1727–1819) from Connecticut, agreed to draft a petition to the king based on this Declaration of Rights.

William Samuel Johnson (1727–1819). “Declaration of Rights and Grievances,” October 19, 1765. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/images/us0010_01p1_enlarge.jpg ">Page 2 . William Samuel Johnson Papers, Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (025)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/no-taxation-without-representation.html#obj025

Proceedings of the Stamp Act Congress

In the fall of 1765, American colonists convened a Stamp Act Congress in New York and called for a boycott of British imports. The congress was attended by twenty-seven delegates from nine states, whose mandate was to petition the king and Parliament for repeal of the tax without deepening the crisis. The congress emphasized the point that the colonists possessed all the “inherent rights and privileges of Englishmen.” It adopted thirteen points, the third of which stated that “it is inseparably essential to the freedom of the people, and the undoubted right of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them but with their own consent, given personally or by their representatives.”

1765 Stamp Act Congress, New York in Proceedings of the Congress at New-York . Annapolis [Md.]: Jonas Green, 1766. Rare Book and Special Collections Division , Library of Congress (026)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/no-taxation-without-representation.html#obj026

Affixing the Stamp

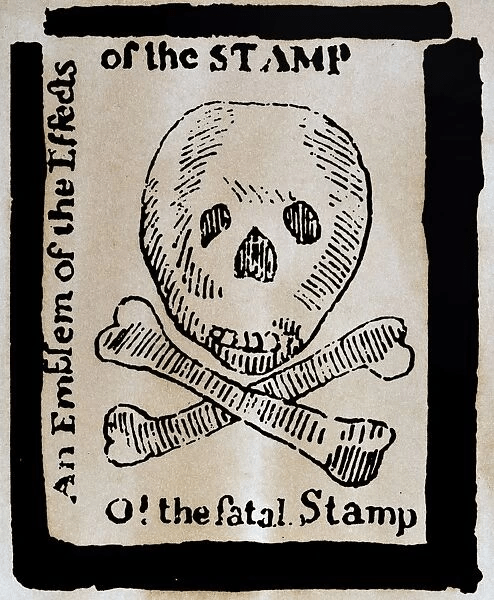

The British government enacted the Stamp Act to raise revenue from its American colonies for the defense of North America. Prime Minister George Grenville (1712–1770) also wanted to establish Parliament’s right to levy an internal tax on the colonists. Because the Stamp Act required that a revenue stamp be affixed to all print publications, its economic impact fell most heavily on printers. This issue of William Bradford’s Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser shows a skull and crossbones representing the official stamp required by the act.

Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser , October 24, 1765. Serial and Government Publications Division , Library of Congress (027)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/no-taxation-without-representation.html#obj027

Patriotic Farmer—John Dickinson

John Dickinson (1732–1808), the influential Pennsylvania politician and author of Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer , was one of the leading figures at the Stamp Act Congress of 1765. Dickinson was a chief contributor to the Declaration of Rights and Grievances that the congress sent to King George III and Parliament to petition for the repeal of the Stamp Act. In this engraving of Dickinson, his right arm rests on Magna Carta. Coke’s Institutes , whose interpretation of Magna Carta inspired American legal and political thought in the eighteenth century, can be seen on the bookshelf behind him.

The Patriotic American Farmer J-n D-k-ns-n Esqr. Barrister at Law [John Dickinson]. Engraving, between 1870–1880. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress (028)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/no-taxation-without-representation.html#obj028

Stamp Act Parody

This 1766 cartoon depicts a mock funeral procession along the Thames River in London for the American Stamp Act. The act, which encountered intense opposition in America, was believed by many Americans to violate central rights that were guaranteed to all Englishmen. Following widespread public protests, colonial leaders channeled popular opposition to the tax by way of petitions to the king and Parliament. Bowing to the pressure, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766. In this cartoon, a funeral procession to the tomb of the Stamp Act includes its principal proponent, Treasury Secretary George Grenville, carrying a child’s coffin, marked “Miss Ame-Stamp born 1765, died 1766.”

The Repeal or the Funeral of Miss Ame-Stamp [1766]. Etching. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress (029)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/no-taxation-without-representation.html#obj029

Back to top

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

"No Taxation Without Representation"

Perhaps no phrase is used more to describe the grievances of the colonists in the lead up to the American Revolution than “No taxation without representation!” While the exact phrase did not appear until 1768, the principle of having consent from the people on issues of taxation can be traced all the way back to the Magna Carta in 1215.

The Magna Carta was one of the first steps in limiting the power of the king and transferring that power to the legislative body in England, the Parliament. Parliament had the power to levy taxes. When King Charles I attempted to impose taxes by himself on the English people in 1627, the Parliament passed the Petition of Right the following year, which stated that the subjects of the king “should not be compelled to contribute to any tax, tallage, aid, or other like charge not set by common consent, in parliament.”

The Magna Carta, the Petition of Right and the English Bill of Rights from 1689 helped to form the basis of the British constitution (which is not a single document, but a combination of written and unwritten agreements). The British constitution protected the rights of Englishmen. English colonists in North America believed that they had the same rights of Englishmen. In North America, colonists formed their own colonial governments under charters from the king and regulated their own forms of taxation from their colonial legislatures. For many decades, these colonies enjoyed an extended period of benign neglect as the English parliament let them handle taxation on their own.

In Great Britain in the eighteenth century, there were no income taxes because it was viewed as too much of a government intrusion into the lives of the people. Instead, taxes were placed on property and on imported and exported goods. Money from these taxes helped to pay for public goods and services and supported the government’s military for defense.

In North America, the British colonies regulated their own tax system in each individual colony. These taxes, though, were exceedingly low, and the colonies did not have a professional military to support. Instead, they used a volunteer militia system to defend their towns and homes from attacks along the frontier.

In 1754, the French and Indian War broke out in North America. During the war, the British sent their military to help defend the colonies. The war spread across the globe and became known as the Seven Years’ War. Following Britain’s victory in 1763, the British national debt greatly increased. They now had a larger empire now that needed to be defended. In light of this tenuous situation, and since the North American colonists benefitted directly from the British military during the war, Great Britain looked to levy taxes on the colonists to raise revenue for the Crown.

In Massachusetts in 1764, James Otis published a pamphlet titled “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved,” which argued that man’s rights come from God and that governments should only exist to protect those natural rights. He believed that any attempt to tax the colonists without their consent violated the British constitution. Here, Otis made a compelling argument for the need for representation in any taxation on the colonies: “no parts of His Majesty’s dominions can be taxed without their consent; that every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature; that the refusal of this would seem to be a contradiction in practice to the theory of the constitution.”

In 1764, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which revised a 1733 tax on molasses being imported to the North American colonies from the West Indies. It improved the enforcement of this tax and explicitly stated that the reason was to raise revenue, a first of its kind. American colonists, especially in New England, responded furiously to this new tax.

Samuel Adams said in response to the Sugar Act: “If taxes are laid upon us in any shape without ever having a legal representative where they are laid, are we not reduced from the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves?”

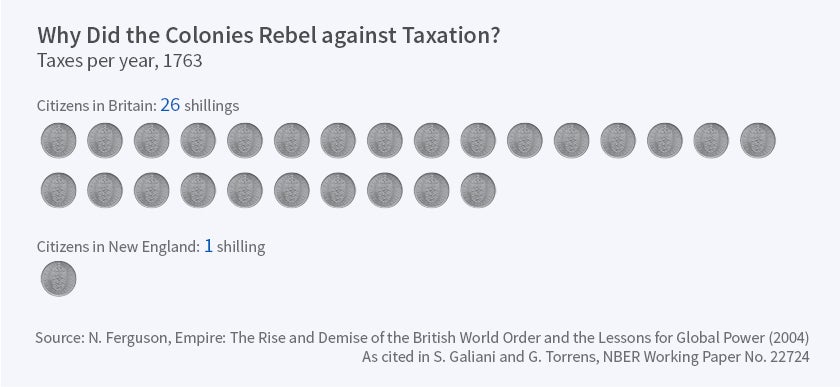

While the colonists likened their situation to slaves of the British Empire, American colonists paid very little in taxes compared with their counterparts in Great Britain. In Great Britain, a person paid about 26 shillings a year in taxes, while in America, they still paid only 1 shilling a year in taxes. Despite this, the American colonists strongly opposed the tax and the lack of any power to influence the decisions of Parliament.

The following year, in 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which levied a tax on many paper goods (such as newspapers, pamphlets, and legal documents) within the colonies. American colonists met the Stamp Act with protests and outrage. Protests included violence against tax collectors, the formation of the Sons of Liberty, and the creation of numerous “Liberty Trees” where gatherings and demonstrations against British overreach were displayed. In October 1765, delegates from nine different colonies gathered in New York at the Stamp Act Congress. They passed a Declaration of Rights and Grievances in which they asserted in part “that it is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted rights of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.”

The Stamp Act became so unpopular that in 1766 Parliament repealed the act. However, they also passed a Declaratory Act that directly contradicted the colonists view on the authority to levy taxes. The Declaratory Act noted that Parliament “had hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.”

In 1768, the catchphrase of “No taxation without representation” first appeared in a London newspaper. As debate continued throughout the 1760s and 1770s over whether the Crown had the right to tax the colonial subjects, the phrase grew more and more popular. It provided an ideological argument in a short and powerful way against many of the subsequent taxes, such as the Townshend Acts in 1767 and 1768 and the Tea Act in 1773. As the colonies grew more and more rebellious to these taxes, the Crown pushed back stronger and only further drove the two parties towards organized conflict. Conflict finally ignited in 1775, and by the following year, the colonies united and declared their independence from Great Britain.

In 1778, Parliament finally passed the Taxation of Colonies Act which repealed the taxes, but by that point it was too late. What had begun as an argument over the ability and right to levy taxes had expanded into a conflict over the right of self-determination and freedom.

Today, the phrase “No taxation without representation” continues to be used by people who want to have a say in how they are taxed. It remains a powerful phrase that provokes people to think about the consent of the governed.

The Other Tea Parties

The Colonial Responses to the Intolerable Acts

“Boston a Teapot Tonight!”

You may also like.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Tax Planning

What Is Taxation Without Representation?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sarah-Fisher-WebReady-01-271f64d902c2476daaec4cf43d53dd3b.jpg)

How Taxation Without Representation Works

Examples of taxation without representation, frequently asked questions.

miralex / Getty Images

“T axation without representation ” is a slogan used to describe being forced by a government to pay a tax without having a say—such as through an elected representative—in the actions of that government.

Key Takeaways

- “Taxation without representation” is a phrase used to describe being subjected to taxes without having a legislative say in the government imposing the tax.

- In the U.S., the phrase has its roots in the colonial period when colonists were angered by the British Parliament imposing taxes on them while the colonists themselves had no representatives in Parliament.

- Throughout the history of the U.S., other groups, such as free Black men, women, and residents of certain jurisdictions, have complained that they were and remain subject to taxation without representation.

In the U.S., the concept of taxation without representation has its origins in a 1754 letter from Benjamin Franklin to Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts.

In this letter, titled “On the Imposition of Direct Taxes Upon the Colonies Without Their Consent,” Franklin wrote:

“...[E]xcluding the people of the colonies from all share in the choice of the grand council will give extreme dissatisfaction, as well as the taxing them by act of Parliament, where they have no representative. …It is supposed an undoubted right of Englishmen not to be taxed but by their own consent, given through their representatives.”

The phrase was widely used a decade later in the colonial response to Parliament’s imposition of the Stamp Act of 1765. The Stamp Act imposed a tax on paper, legal documents, and various commodities. It also reduced the rights of colonists, including limiting trial by jury. It was repealed in 1766.

The same day that the Stamp Act was repealed, the Declaratory Act was enacted by the British Parliament. That Act effectively stated that the British Parliament had absolute legislative power over the colonies.

The Stamp Act and other British tax acts, like the Townshend Acts of 1776, were a major catalyst for the American Revolution.

“Taxation without representation” is a phrase describing the situation of being subject to taxes imposed by a government without being represented in the decisions made by that government.

Washington, D.C.

Throughout the history of the U.S.—and even today—various disenfranchised groups and individuals have criticized the fact that they have been subjected to taxation without representation.

Washington, D.C. is an example of modern-day taxation without representation. The residents of the district pay federal taxes, but the District of Columbia has no voting power in Congress . Because the District of Columbia is not a state, it sends a non-voting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. While this delegate can draft legislation, they can’t vote. In addition, the District of Columbia can’t send anyone to the U.S. Senate, so it is effectively shut out of that congressional body.

In Washington, D.C. license plates with the phrase “End Taxation Without Representation” at the bottom are issued by default to newly registered vehicles.

While the residents of the District of Columbia are subject to new federal taxes or increases of existing federal taxes that are passed by Congress, they do not have someone representing them who can actually vote on this legislation. They are, therefore, taxed without representation.

Many believe this issue of taxation without representation is a strong argument in favor of D.C. statehood. Others believe, instead, that residents of Washington, D.C., should not be subject to the same federal income taxes as residents of represented states.

Residents of U.S. Territories

The U.S. has five permanently inhabited territories: American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Like Washington, D.C., the five U.S. territories only have non-voting delegates in the U.S. House and no members in the U.S. Senate.

While those residing in the territories are subject to different income tax rules than other residents of the U.S. and, in some cases, pay no federal income taxes, they are subject to other federal taxes, such as the Social Security tax and Medicare tax.

As with Washington, D.C., many have called for statehood for these U.S. territories, especially Puerto Rico.

Free Black Men

Throughout most of the 19th century, free Black men complained they were subject to taxation without representation, and petitioned their governments for tax exemptions , in some cases receiving them. Other states that were petitioned chose to not use race as a voting qualification.

It was not until the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870 that it was made unconstitutional to prevent a citizen’s right to vote on the basis of race.

It was not until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920 that it was made unconstitutional in the U.S. to prevent a citizen’s right to vote on the basis of sex.

Before this amendment was ratified, many women appealed that they were subject to taxation without representation. For example, in 1872, American social reformer and women's rights activist Susan B. Anthony went on a speaking tour to deliver an address called “Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?” In this address, she pointed out that it was taxation without representation to not allow women to vote:

“The women, dissatisfied as they are with this form of government, that enforces taxation without representation…are this half of the people left wholly at the mercy of the other half, in direct violation of the spirit and letter of the decorations of the framers of this government, every one of which was based on the immutable principle of equal rights to all.”

Is there still taxation without representation in the United States?

If you are a resident of Washington D.C. you have to pay federal income taxes, but you don't get a senator or voting congressperson to represent you. Minors are also subject to income taxes above a certain threshold, but they are not permitted to vote. In some states, felons lose the right to vote even after serving their prison sentence, but they are still required to pay taxes.

Why did colonists consider British taxes unjust?

American colonists were unable to vote for any of the legislators in London who determined how much they should pay in taxes, and how those taxes were used. That means they were forced to pay for and support a government that did not give them a voice or a vote.

Constitution.org. “ A Plan for Colonial Union by Benjamin Franklin .”

Library of Congress. “ Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor - No Taxation Without Representation .”

Library of Congress. “ Documents From the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774 to 1789 .”

Government Publishing Office - Ben’s Guide. “ Declaration of Independence - 1776 .”

Government of the District of Columbia. “ Why Statehood for DC .”

District of Columbia Department of Motor Vehicles. “ End Taxation Without Representation Tags .”

Office of Congressman Michael F.Q. San Nicolas. “ Senate Representation for the U.S. Territories .”

IRS. “ Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Territories/Possessions .”

IRS. “ Persons Employed in a U.S. Possession/Territory - FICA .”

Christopher J. Bryant. “ Without Representation, No Taxation: Free Blacks, Taxes, and Tax Exemptions Between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars .” Page 108. Michigan Journal of Race & Law .

National Constitution Center. “ 15th Amendment - Right to Vote Not Denied by Race .”

National Constitution Center. “ 19th Amendment - Women’s Right To Vote .”

Famous Trials by Prof. Douglas O. Linder. “ Address of Susan B. Anthony .”

Taxation Without Representation

Taxation Without Representation in Colonial America was the primary cause of the American Revolution. It led to the American Revolutionary War, and, ultimately, the establishment of the United States of America.

Samuel Adams was one of the most important leaders of the Patriot Cause and helped fight against Taxation Without Representation. Image Source: MFA Boston .

Essential Facts

- Before 1763, the British government used the Navigation Acts to control trade and shipping in the British Empire.

- The first Navigation Act was passed in 1651. It was followed by more laws that added trade, shipping, and manufacturing restrictions. Because of the distance between England and America, the laws were difficult to enforce, and often ignored.

- To maintain control over the American Colonies , British officials neglected to enforce the laws. This unwritten policy is called Salutary Neglect .

- Parliament started to change its approach to the colonies when it passed the 1733 Molasses Act , forcing the colonies to acquire molasses from British Plantations in the Caribbean. This led to an increase in smuggling by American merchants.

- Following the French and Indian War , Parliament needed money, so it passed the Sugar Act , which levied taxes on shipments of goods not to regulate trade, but to raise revenue. It was also known as the American Revenue Act.

- Americans had no representation in Parliament, so they openly protested the Sugar Act by publishing pamphlets and refusing to import British goods.

- The Sugar Act was followed by a series of laws that levied taxes on Americans, without their consent, or representation in Parliament, including the Stamp Act (1765) , Townshend Revenue Act (1767) , and the Tea Act (1773) . With each new law, Americans strengthened their stance and turned to the slogan “No Taxation Without Representation.”

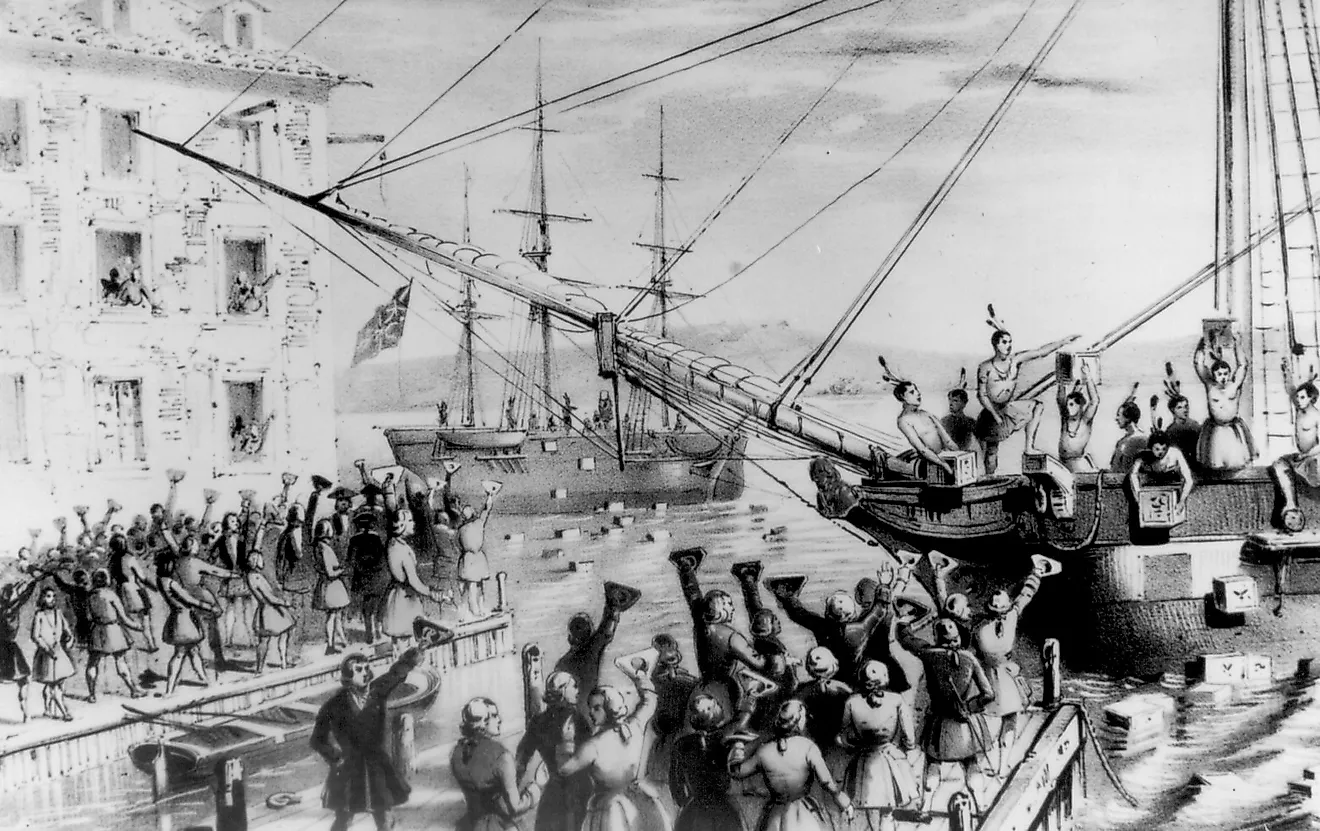

- On December 16, 1773, the Boston Sons of Liberty protested the Tea Act by throwing more than 340 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

- Parliament responded with the Intolerable Acts , which punished the city of Boston and the Massachusetts Colony.

- Americans responded by organizing the First Continental Congress — America’s first governing body — and establishing the Continental Association .

Significance to American History

The period leading up to the American Revolution was marked by growing discontent among the colonists due to British taxation and trade regulations imposed without their consent. This concept of Taxation Without Representation united many Americans against British authority, laying the groundwork for the American Revolutionary War and the Declaration of Independence . The events and measures taken by Britain and the 13 Colonies during this period significantly contributed to the shaping of American identity and the pursuit of self-governance, leading to the establishment of the United States of America in 1776.

The History of Taxation Without Representation in Colonial America

The navigation acts and mercantilism.

The Navigation Acts – also known as the Acts of Trade and Navigation — were a series of laws enacted by the British Parliament between 1651 and 1774 that regulated shipping and trade in Colonial America.

Rooted in the principles of Mercantilism , the Navigation Acts aimed to strengthen the British economy by utilizing the colonies as a source of raw materials and a market for finished goods.

Initially, the Navigation Acts focused on challenging Dutch competition in overseas trade, requiring that most American goods be transported in English or colonial ships with a significant British crew presence. Although the first Navigation Act contributed to the First Anglo-Dutch War , British officials continued to add new laws.

Over time, additional Navigation Acts were passed to tighten imperial control and protect British merchants and manufacturers from colonial competition. The Revenues Act of 1663 imposed a “plantation duty” on certain colonial goods not delivered to England, while customs officials were assigned to colonial port cities. Despite these measures, enforcement proved challenging due to limited personnel and the distance between Great Britain and the colonies.

In an attempt to further protect British interests, subsequent acts, often referred to as the Trade Acts, targeted specific industries and restricted manufacturing in America. The 1699 Woolen Act and the 1732 Hat Act prohibited the export and intercolonial sales of certain textiles and colonial-made hats.

Salutary Neglect

In 1721, Robert Walpole was named First Lord of the Treasury and also became the first Prime Minister of Britain. Walpole sought to expand the British Empire through trade and understood that American merchants were generating profits that benefitted Britain, even if they were doing so through illegal means.

Another member of the King’s cabinet, Thomas Pelham-Holles, the Duke of Newcastle, supported Walpole’s vision and helped shape Britain’s policy toward the American Colonies. However, Britain still failed to establish significant methods of collecting duties and enforcing the laws in the colonies.

During the time of Salutary Neglect , British government officials concentrated on affairs in Europe. As long as the American Colonies continued to produce raw materials for British industries and to buy finished products from British merchants those officials were willing to look the other way — even if they had no choice but to do so.

The Molasses Act

The 1733 Molasses Act, a Navigation Act, was designed to protect British Sugar Plantations in the Caribbean and imposed a high tax on molasses imported to the colonies from non-British ports. For the most part, the Molasses Act failed to achieve its purpose, and the smuggling of molasses increased.

Impact of the Navigation Acts

While the Navigation Acs achieved their goals, such as a favorable balance of trade and reduced dependence on foreign markets, they had notable consequences for the American colonies.

Surprisingly, the acts stimulated the colonial economy by providing guaranteed markets and incentives for producing specific commodities. Some acts even helped increase shipbuilding in New England.

However, not all acts were strictly followed, with colonial merchants freely trading restricted goods such as rum, molasses, and sugar. While American merchants believed they were being smart businessmen, maximizing their profits, British officials viewed what they were doing as smuggling.

Still, none of these laws affected taxes for most people living in the American Colonies. Taxation was left to the colonial legislatures. The Navigation Acts were a way for Parliament to regulate trade for the benefit of Great Britain. However, the limitations and restrictions imposed by the Navigation Acts started to be felt by some colonists in the mid-18th century when Great Britain ended the policy of Salutary Neglect.

Raising Revenue Through Taxation

The American Revolution was primarily in response to the series of laws passed by Parliament after the French and Indian War. These laws aimed to regulate trade, just like the Navigation Acts, but they also imposed taxes on the American Colonies as a way of raising revenue for the British Treasury.

The new laws led to increasing tensions between American leaders and British officials, as Parliament ignored American complaints about the harshness of these laws. Many colonists, especially prominent merchants, felt that their concerns were being dismissed and Parliament was becoming corrupt, controlling, and overstepping the authority it was given in the British Constitution . Americans started to believe their rights as Englishmen were at risk, which were guaranteed by the English Bill of Rights . This formed the foundation of the ideology of the American Revolution and the decision to declare independence from Britain in July 1776.

The Aftermath of the French and Indian War and Colonial Taxation

In 1763, after the French and Indian War, the British government faced significant debts. To address this, British Prime Minister George Grenville decided to reduce the duties on sugar and molasses but also chose to strictly enforce the Navigation Acts.

To help enforce the laws, the British Royal Navy was authorized to seize merchant ships that were suspected of carrying illegal shipments of goods. This effectively ended the unwritten policy of Salutary Neglect. Previously, the enforcement of the laws had been lenient, allowing colonists to avoid paying them, or pay less by bribing customs officials.

Strict enforcement increased revenue for the British government but also led to higher taxes for the colonists. In response, the colonial legislatures of New York and Massachusetts formally protested by sending letters to Parliament.

Parliament Passes the Currency Act of 1764

The American economy struggled after the war and suffered from a recession. When American merchants fell behind on paying their bills, British merchants started to demand they pay their debts in hard money — gold and silver coins, also known as specie — rather than colonial paper currency. Hard Money was a far more stable currency than paper money, which meant British merchants could use it for other transactions.

To address this issue, Parliament passed the 1764 Currency Act , which prohibited the colonies from issuing their paper currency. This made it even more challenging for colonists to settle their debts and pay taxes because Hard Money was scarce. Thanks to the Mercantile System, most of it was held by British merchants.

Soon after the Currency Act was passed, Prime Minister George Grenville presented revisions to the Molasses Act, which became the 1764 Sugar Act, and proposed a new Stamp Tax. Parliament approved the Sugar Act, but the Stamp Tax was delayed.

When news of the new laws reached America, there was outrage. The Sugar Act specifically stated it was for raising money from the colonies, not just for regulating trade. Prominent Americans such as James Otis and Stephen Hopkins wrote pamphlets, arguing the Sugar Act violated the Constitution because the colonies were not represented in Parliament.

In his pamphlet, Rights of the Colonies Examined , Hopkins criticized Parliament for passing the Sugar Act and considering the Stamp Act, while questioning the colonies’ lack of representation in Parliament. Hopkins wrote:

“…the equity, justice, and beneficence of the British constitution will require that the separate kingdoms and distant colonies who are to obey and be governed by these general laws and regulations ought to be represented, some way or other, in Parliament, at least whilst these general matters are under consideration.”

James Otis echoed similar sentiments in his pamphlet, Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved . Otis argued the colonies had a right, “…to be represented in Parliament, or to have some new subordinate legislature among themselves. It would be best if they had both.”

Otis laid the foundation for “No Taxation Without Representation” by saying, “The supreme power cannot take from any man any part of his property, without his consent in person, or by representation.”

During the debate over the Sugar Act, Samuel Adams , a former tax collector and failed businessman, started his rise to prominence as a leader of the Patriot Cause and advocate for Independence.

Despite the protests, Parliament moved forward and passed the Stamp Act , which threatened to force Americans to pay a tax on nearly any printed materials, including newspapers, marriage licenses, and playing cards.

The Stamp Act Crisis

Americans reacted strongly to the Stamp Act . The Virginia House of Burgesses passed resolutions that denied the Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies. The second Virginia Stamp Act resolution argued against Taxation Without Representation:

“…the Taxation of the People by themselves or by Persons chosen by themselves to represent them who can only know what Taxes the People are able to bear and the easiest Mode of raising them and are equally affected by such Taxes themselves is the distinguishing Characteristick of British Freedom and without which the ancient Constitution cannot subsist.”

In Boston, riots took place and the homes of British officials were attacked and vandalized. These political and public protests spread to other colonies. For the first time, a faction of Americans was united in opposition to Parliament.

The Stamp Act Congress

In October 1765, delegates from 9 of the 13 colonies met in New York to discuss a unified response to the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act Congress issued petitions to Parliament and the King. Congress denied Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies but emphasized loyalty to the Crown. The Declarations and Resolves of the Stamp Act Congress declared:

“…is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted rights of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.”

Further, Congress argued, “…the only representatives of the people of these colonies are persons chosen therein, by themselves; and that no taxes ever have been, or can be constitutionally imposed on them, but by their respective legislatures.”

The argument was essentially between the American Colonies and Parliament, over Parliament violating the rights of Americans as subjects of the King.

Non-Importation Agreements

American merchants responded to the Stamp Act by refusing to import British goods and agreeing to the Non-Importation Agreement. This trade boycott, along with the ongoing recession, eventually pressured British merchants to ask Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act.

Declaratory Act

While Parliament agreed to repeal the Stamp Act, it also passed the Declaratory Act. With this law, Parliament essentially gave itself the authority to pass legislation it felt was needed to govern America. Although taxes were not specifically mentioned, the language of the law made it clear Parliament believed it had the right to levy taxes on the American Colonies.

Sons of Liberty and Daughters of Liberty

During the Stamp Act Crisis, groups of men and women who opposed the taxes formed. Although they were known by different names, they are generally known as the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty.

While the Daughters focused on domestic issues, such as making homemade clothing — known as “Homespun” — the Sons focused on organizing protests, often turning to violence. Sons of Liberty groups were formed in prominent cities like Boston (Massachusetts), New York City, Charleston (South Carolina), Annapolis (Maryland), and Portsmouth (Rhode Island), along with many smaller towns throughout the colonies.

The members of these groups were often political and business leaders and many of them held positions in local and colonial politics. Women like Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren were also involved with the intellectual side of the debate and influenced their husbands.

Over time, the groups established Committees of Correspondence and communicated with each other. These committees helped organize Non-Importation Agreements but were usually disbanded once the uproar over an issue died down.

The Townshend Acts and the Massachusetts Circular Letter

Taxation Without Representation came to the forefront again in 1767 with the introduction of the Townshend Acts , which imposed new taxes through the Townshend Revenue Act . Protests in Boston, particularly the Liberty Affair , led Parliament to send British troops to occupy the city.

Massachusetts protested the Townshend Acts and issued the Massachusetts Circular Letter , which was sent to the other colonies. This prompted many of the other colonies to follow suit, and issue protests over the new taxes.

In the Circular Letter, Massachusetts argued against Taxation Without Representation , saying:

“…the Acts made there, imposing duties on the people of this province, with the sole and express purpose of raising a revenue, are infringements of their natural and constitutional rights; because, as they are not represented in the British Parliament, his Majesty’s commons in Britain, by those Acts, grant their property without their consent.”

Although Non-Importation Agreements were established throughout the colonies, but often broke down when American merchants violated them. Within three years, tension between colonists in New York City and Boston led to violence in the streets.

Violence and Bloodshed in New York and Boston

Although the Townshend Revenue Act was repealed in March 1770, the tension in America had reached a breaking point.

In January 1770, New Yorkers and the Sons of Liberty clashed with British troops in New York City during the Golden Hill Riots . This was followed by an incident in Boston in which a Loyalist fired a gun into a mob, killing 11-year-old Christopher Seider.

Soon after, a Boston mob attacked a handful of British troops , who responded by firing into the crowd. This event, which Samuel Adams called “The Boston Massacre,” led to the removal of troops from the city.

With the onset of violence and the repeal of the Townshend Revenue Act, tensions over Taxation Without Representation eased.

The Gaspee Affair

For roughly two years, the Navigation Acts were enforced, and American merchants did what they could to avoid paying the shipping taxes. This contributed to the Gaspee Affair , a dispute between British officials and colonial officials over how to handle the Gaspee Incident.

The incident took place from June 9–10, 1772, and included Rhode Islanders attacking the British schooner HMS Gaspee , shooting a British naval officer, and destroying the ship by setting it on fire. In the aftermath, British officials investigating the incident wanted to arrest the men responsible and take them to Britain to stand trial. Americans were outraged and believed the right to a fair trial would be violated.

In the aftermath of the affair, a Boston preacher, John Allen, delivered a sermon called “An Oration on the Beauties of Liberty.” Allen used the Gaspee Affair to criticize Parliament for passing laws to govern the colonies because it did not represent the colonies. He said:

“The Parliament of England cannot justly make any laws to oppress, or defend the Americans, for they are not the representatives of America and therefore they have no legislative power either for them, or against them.

The house of Lords cannot do it, for they are Peers of England, not of America; and, if neither king, lords, nor commons, have any right to oppress, or destroy, the liberties of the Americans, why is it then, that the americans do not stand upon their own strength, and shew their power, and importance, when the life of life, and every liberty that is dear to them and their children is in danger.”

Permanent Committees of Correspondence

When news of the Gaspee Affair spread through the colonies, the Virginia House of Burgesses established a permanent Committee of Correspondence for intercolonial communication and urged the other colonies to do the same.

The permanent Committees of Correspondence were an important development in American history because they enabled the colonies to frame a more unified response to grievances regarding British colonial policies.

East India Company and the Tea Act

Meanwhile, the East India Company , which controlled British affairs in India, was facing financial issues and was on the brink of bankruptcy. To assist the company, Parliament passed the Tea Act , which granted it a monopoly on all tea exported to the American Colonies. The company was allowed to choose a limited group of colonial merchants to sell tea in North America, which was intended to stabilize the company’s financial situation. Further, the company did not have to pay the taxes associated with shipping tea, per the Navigation Acts.

Americans believed it was nothing more than a plot to trick them into accepting Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies. Although the Tea Act reduced taxes for other tea importers, the tax-free status of the East India Company made it impossible for colonial tea traders to compete. Outraged Americans called for a general boycott of all British goods, not just tea.

Boston Tea Party

On December 16, 1773, the Boston Sons of Liberty, disguised as Native Americans, boarded East India Company ships in Boston Harbor and dumped crates of tea into the water. This event, known as the Boston Tea Party , was the beginning of the end of British control of America.

Parliament Responds with the Intolerable Acts

When news of the Boston Tea Party reached England, British officials took decisive action to restore order and discipline in the colonies.

Parliament ordered the closure of the port of Boston until the East India Company was compensated for the destroyed tea and passed three more laws to bring Massachusetts under direct British control. These laws were known in the American colonies as the Intolerable Acts.

To enforce the new laws in Boston, General Thomas Gage was appointed as the military governor of Massachusetts.

Additionally, Parliament expanded the Province of Quebec with the Quebec Act , which essentially blocked the westward expansion of the colonies.

The Formation of the First Continental Congress

In Boston, some believed it was time to ease tensions and sent a written offer to London to pay for the destroyed tea. This was rejected by political leaders associated with the Sons of Liberty. Benjamin Franklin offered to pay for the tea, but this rejected by British officials

Boston leaders called for a new, colony-wide Non-Importation Agreement, known as the Solemn League and Covenant . Although some merchants were hesitant to participate in such a boycott, many towns agreed to the measure.

When Massachusetts asked the other colonies to join the Non-Importation Agreement, there was hesitation. Although the other colonies supported Boston, and many of them sent supplies to the city, they decided it would be better to hold meetings to craft a unified response to the Intolerable Acts.

As a result, colonial legislatures sent representatives to Philadelphia, where the First Continental Congress convened in September 1774. On October 20, Congress adopted the Articles of Association , which listed colonial grievances and called for a boycott in all the colonies, set to begin on December 1 if the Intolerable Acts were not repealed. Instead of relying on merchants to comply with this “Continental Association,” Committees of Inspection were formed to enforce the provisions.

Additionally, the delegates drafted a petition to King George III, detailing their complaints, although they were increasingly doubtful that the crisis could be resolved through negotiations. This “ Humble Petition to the King ” accused Parliament of being the cause of the trouble that led to the American Revolution.

The Powder Alarm and the New England Army

Meanwhile, Massachusetts set up its own government, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and started to make preparations for hostilities with Britain. This Congress feared Britain would refuse to repeal the Intolerable Acts and use military force to break the Continental Association.

When Governor Thomas Gage found out, he took steps to confiscate weapons and gunpowder from the storehouse in Charlestown, Massachusetts. This incident, known as the Massachusetts Powder Alarm , led to rumors the British had attacked Boston and set the city on fire.

Afterward, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress started to organize an army for the New England Colonies . For the next few months, into the early part of 1775 , both American and British leaders took steps to avoid hostilities — while at the same time preparing for war.

The Debate Over Taxation Without Representation Turns to War

On the night of April 18, 1775, Gage sent a contingent of troops, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Smith and Major John Pitcairn , to Concord, Massachusetts. Their mission was to confiscate and destroy military supplies that were hidden there by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

While Smith’s expedition sailed across Boston Harbor to Lechmere Point, Patriot leader Joseph Warren sent Paul Revere and William Dawes on a horseback ride to Concord. Their mission on this historic Midnight Ride was to warn people along the way that the British were on the move and to warn Patriots in Concord to move the supplies to safety.

After a lengthy delay, the British started their march toward Concord. As they marched west along the Bay Road, they heard the sounds of alarm guns and drums, calling the Massachusetts Militia and Minutemen to arms. When the expedition reached Lexington, they found Captain John Parker and the Lexington Militia assembled. Within moments, a shot was fired and the British rushed the Americans and routed them in the Battle of Lexington .

The debate over Taxation Without Representation was over, and the American Revolutionary War was started.

- Written by Randal Rust

- What Does "No Taxation Without Representation" Mean?

“No Taxation without Representation”' is a slogan that was developed in the 1700s by American revolutionists. It was popularized between 1763 and 1775 when American colonies protested against British taxes demanding representation in the British Parliament during the formulation of taxation laws.

During the British rule in the United States, the Parliament levied taxes on the colonies without consultation, consent or approval of the taxed parties. These laws formed the foundation of the American Revolution and were among the reasons for the havoc of the Boston Tea Party. The Stamp, Tea, and Sugar Acts were among the laws passed by the British Parliament based in the United Kingdom. The colonists complained that parliament was violating the right to representation, which was a tradition of the Englishman. The British Parliament claimed that America was an extension of Britain, but the Americans argued that parliamentarians knew nothing concerning America.

In 1765, the Americans rejected the Stamp Act , and in 1773, they rebelled against taxation of tea imports. An armed tussle ensued and quickly escalated into the American War of Independence. Although the taxes introduced by the British were low, much of the complaint was not about the amount but the decision-making process in which the taxes were decided.

Origin Of The Phrase

Reverend Jonathan Mayhew coined the slogan “No Taxation without Representation" during a sermon in Boston in 1750. By 1764, the phrase had become popular among American activists in the city. Political activist James Otis later revamped the phrase to "taxation without representation is tyranny." In the mid-1760s, Americans believed that the British were depriving them of a historical right prompting Virginia to pass resolutions declaring Americans equal to the Englishmen. The English constitution stipulated that there should not be taxation without representation, and therefore only Virginia could tax Virginians.

Modern Usage

The phrase "No Taxation without Representation” has been adopted as a global slogan to rally against exclusion from political decisions, unresponsive governments, and high taxes. It was used by women movements to decry the denial of voting rights. The TEA (Taxed Already Enough) movement continues to use the slogan to undermine Washington’s continued lack of fiscal restraint without considering public opinion. The phrase appears on the District of Columbia license plates because the citizens of the district pay federal taxes yet they are not represented by a voting member in Congress .

- World Facts

More in World Facts

The Largest Countries In Asia By Area

The World's Oldest Civilizations

Is England Part of Europe?

Olympic Games History

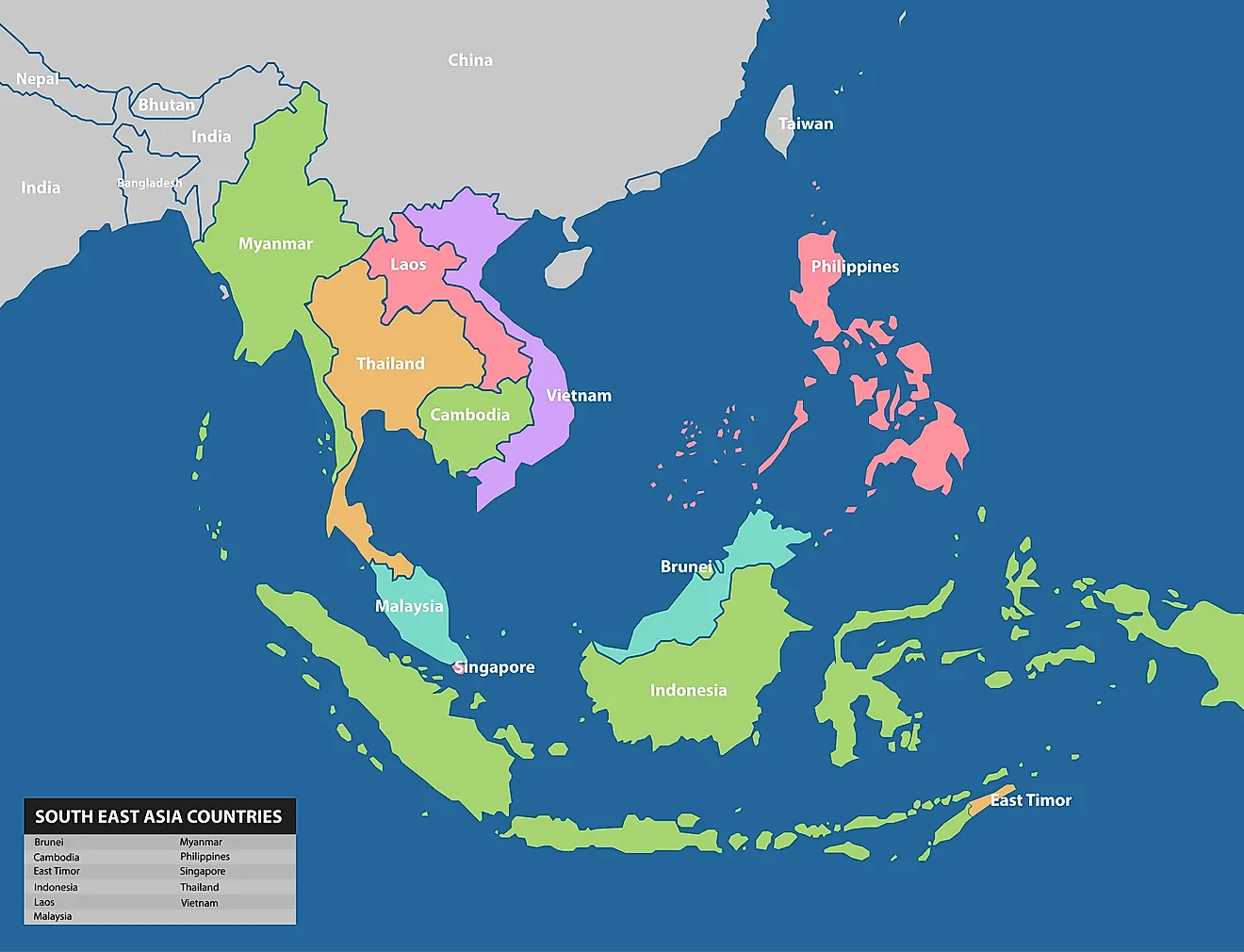

Southeast Asian Countries

How Many Countries Are There In Oceania?

Is Australia A Country Or A Continent?

Is Turkey In Europe Or Asia?

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, interpretation & debate, the taxing clause, matters of debate, common interpretation, the power to tax, not to destroy: an effects theory of the taxing clause, the power to tax.

by Neil S. Siegel

David W. Ichel Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science at Duke Law School; Director of Duke's D.C. Summer Institute on Law and Policy

by Steven J. Willis

Professor of Law at the University of Florida Levin College of Law

Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress lacked the power to protect the states from military warfare waged by foreigners and from commercial warfare waged by one another. The states proved unable to solve these difficulties on their own. They acted individually when they needed to act collectively, and the Framers of the United States Constitution concluded that the states cannot reliably accomplish an objective when doing so requires them to cooperate.

Arguably the most severe problem facing the young nation under the Articles was that the national government had no power to tax individuals directly; indeed, it had no effective way of raising money at all. Instead, it was limited to “requisitioning” (that is, asking) the states to contribute their fair share of tax revenue to the national treasury in order to repay the Revolutionary War debts and fund the national government. Instead of complying with these requests, states free rode off the contributions of sister states. The consequence was that the national government was severely underfunded, which (among other things) gravely threatened national security.

The solution to the collective action failures of the Articles lay with the establishment of a more powerful and comprehensive unit of government—a national government with the authority to tax, raise and support a military, regulate interstate and international commerce, and act directly on individuals. The Taxing Clause of Article I, Section 8, is listed first for a reason: the Framers decided, and the ratifiers of the Constitution agreed, that Congress must itself possess the power “to lay and collect Taxes . . . to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.” Congress was given the power to assess, levy, and collect taxes without any need of assistance from the states, and Congress’s taxing power was not limited to repayment of the Revolutionary War debts—it was prospective as well.

After the Constitution was ratified, Alexander Hamilton (representing the Federalist Party) and James Madison (representing the Democratic Republican Party) debated the scope of the Taxing Clause. According to Hamilton, Congress possessed a robust power to tax (and spend) regardless of whether the tax (or expenditure) could plausibly be viewed as carrying out another enumerated power of Congress, such as regulating interstate commerce or raising and supporting a military. Madison argued that Congress had no independent power to tax and spend in pursuit of its conception of the general welfare; rather, Madison contended, the constitutional meaning of the phrase “general Welfare” is defined and limited by the specific grants of authority in the rest of Section 8. The Supreme Court did not weigh in on this longstanding debate over the scope of the federal taxing and spending powers until 1936, in United States v. Butler (1936), when it sided with Hamilton. Ever since, the law has been that Congress can use the Taxing Clause without tying such use to another of its constitutional powers.

What are the constitutional limits on Congress’s authority to use the Taxing Clause? It is clearly established that such power is limited by constitutional provisions protecting individual rights. For example, it would undoubtedly violate the Free Speech Clause if Congress taxed people just because they criticized the federal government.

More controversial is whether there are internal limits on the Taxing Clause, and whether they may be enforced by courts. Relatively early in American history, the Supreme Court suggested, in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), that redress for misuse of the taxing power lies with the political process, where unhappy citizens can vote politicians out of office. Later, the Court suggested that courts, too, may enforce the limits on the Taxing Clause, and that Congress exceeds its power when it imposes monetary payments that have the primary purpose of regulating people’s behavior, not of raising revenue, even when Congress labels the payment a “tax,” not a “penalty.” Child Labor Tax Case ( Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. ) (1922). In more recent times, the Court sustained the constitutionality of required payments just because they raised at least some revenue. Sonzinsky v. United States (1937); United States v. Kahriger (1953). Because decisions from one era deviated from earlier decisions without overruling them, the Court’s Taxing Clause jurisprudence was for a long time difficult to sort out.

In 2012, in NFIB v. Sebelius (the Health Care Case), the Court clarified much of the confusion. It rejected a focus on the primary purpose of the required payment at issue, observing that in America, “taxes that seek to influence conduct are nothing new. Some of our earliest federal taxes sought to deter the purchase of imported manufactured goods in order to foster the growth of domestic industry.” Instead of asking about the primary purpose of the required payment, the Court adopted a “functional approach,” and made whether the payment was a tax or a penalty turn on the “practical characteristics” and likely effects of the payment.

Specifically, the Court held that the so-called “individual mandate” in the federal health care law (the requirement to either obtain health insurance or make a payment to the federal government) was within the scope of the Taxing Clause—even though Congress labeled the payment a “penalty,” not a “tax”—primarily because it was likely to have a relatively modest impact on people’s behavior. The Court reasoned that the required payment would likely discourage people from going without insurance without preventing them from doing so, which is why it was expected to raise several billion dollars in revenue each year. The Court’s holding in NFIB on the scope of the Taxing Clause is today the law of the land.

The Taxing Clause solved perhaps the single greatest collective action failure of the states under the Articles of Confederation: the serial inability of the several states to adequately fund the national government in light of free riding by sister states. See, e.g. , Robert D. Cooter & Neil S. Siegel, Collective Action Federalism: A General Theory of Article I, Section 8 , 63 Stanford Law Review 115 (2010). This failure caused serious financial problems for the young, vulnerable nation and raised grave national security concerns. Where the colonists had insisted that “taxation without representation” was illegitimate, Americans under the Articles learned that taxation with representation was indispensable.

And so the Constitution confers upon Congress robust taxing authority. Congress was granted the power in the initial clause of Article I, Section 8, “to lay and collect Taxes” not just to repay the Revolutionary War debts—the most immediate concern of the country at the time—but more broadly and prospectively to “provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.”

Are there any internal constitutional limits on Congress’s authority to use the Taxing Clause—limits that courts should be prepared to enforce? Many progressive constitutionalists would say “no.” They would follow Chief Justice John Marshall’s suggestion in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), that the power to tax, where it exists, “is the power to destroy.” On this view, redress for misuse of the federal taxing power lies with the political process, where angry citizens who feel overtaxed can “vote the bums out.” Progressive constitutionalists often believe in political safeguards, not judicial safeguards, to limit the exercise of legislative power by the federal government.

My own view is closer to that of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who famously wrote (at a much later date in American history) that the power to tax, while broad, “is not the power to destroy while this Court sits.” Panhandle Oil Co. v. Mississippi ex rel. Knox (1928) (Holmes, J., dissenting). The text of the Taxing Clause is best read to require that exercises of the taxing power be consistent with revenue-raising, regardless of whether raising revenue—as opposed to regulating human behavior—is Congress’s primary purpose. (The Taxing Clause, unlike the Origination Clause of Article I, Section 7, does not require that Congress’s purpose be “for raising Revenue.”)

Moreover, without any enforceable limits on the Taxing Clause, Congress could readily circumvent even very modest limits on the scope of the Commerce Clause. For example, the Supreme Court has held for more than two decades that the Commerce Clause empowers Congress to use penalties to regulate economic conduct that substantially affects interstate commerce, but not to regulate noneconomic conduct. What prevents Congress from penalizing non-economic conduct by calling a penalty a tax and invoking the Taxing Clause? The only obstacle is the distinction between a penalty and a tax for purposes of the federal tax power.

In NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), the Court considered whether the minimum coverage provision in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) imposes a penalty or a tax by requiring most individuals to either obtain health insurance or make a payment to the Internal Revenue Service. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Roberts concluded that this “shared responsibility payment” for going without insurance is a tax for purposes of the Taxing Clause, even though Congress called it a penalty. Along with Robert Cooter, I have developed an effects theory of the federal tax power in order to distinguish between penalties and taxes. See Robert D. Cooter & Neil S. Siegel, Not the Power to Destroy: An Effects Theory of the Tax Power , 98 Virginia Law Review 1195 (2012). We believe that the Court’s tax-power ruling in NFIB is correct, and that our effects theory provides the best theoretical justification for it.

The effect of a penalty is to prevent conduct, thereby raising little revenue, whereas the effect of a tax is to dampen conduct, thereby raising revenue. Three characteristics of a mandatory payment create incentives that either prevent or dampen conduct. These characteristics provide criteria for distinguishing between penalties and taxes. A pure penalty (1) condemns the actor for wrongdoing; (2) she must pay more than the usual gain from the forbidden conduct; and (3) she must pay at an increasing rate with intentional or repeated violations. Thus, a penalty expressively coerces a person by condemning her conduct, and it materially coerces a person with relatively high rates and enhancements for repeated violations. Alternatively, a pure tax (1) permits a person to engage in the taxed conduct; (2) she must pay an amount that is less than the usual gain from the taxed conduct; and (3) intentional or repeated conduct does not enhance the rate. A tax does not coerce expressively because it permits the person to engage in the taxed conduct. And it does not coerce materially because relatively low rates without enhancements leave the person with a reasonable financial choice to engage in the taxed conduct. The ACA’s required payment for remaining uninsured has the expression of a penalty and the material characteristics of a tax (the Court in NFIB called them “practical characteristics”). The constitutional identity of this required payment for purposes of the Taxing Clause depends upon the reasonable expectations of Congress concerning its effect. If Congress could have reasonably concluded that the exaction will dampen—but not prevent—the general class of conduct subject to it (people going without health insurance) and thereby raise revenue, then courts should interpret it as a tax regardless of what the statute calls it. If Congress could have reasonably concluded only that the exaction will prevent the conduct of almost all people subject to it and thereby raise little or no revenue, then courts should interpret it as a penalty.

In the case of the minimum coverage provision in the ACA, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office predicted that the required payment for non-insurance would dampen uninsured behavior but not prevent it, thereby raising several billion dollars in revenue each year. Accordingly, the payment is a tax for purposes of the Taxing Clause.

Without the power to tax, a government will have few resources to do anything. It cannot effectively police its citizens, protect its people from foreign invaders, or regulate commerce because it cannot pay the associated costs. Discarding the Articles of Confederation—which merely allowed Congress to ask states for money—the drafters effectively adopted a taxing document – the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution gave Congress the power to lay taxes and also to collect them. Taxes—more precisely, the money they provide—make all other government actions possible. One might think about that in relation to present-day loose confederations such as the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union. Without the enforceable power to tax, they are necessarily subject to the potentially fleeting willingness of members to contribute.

The U.S. taxing power, while very broad, has important limitations. First, direct taxes must be apportioned, a very difficult requirement. Second, duties, imposts, and excises must be uniform—an easy-to-meet standard, but one which, if ignored, can be fatal to a statute. See , Steven J. Willis & Hans G. Tanzler IV, Affordable Care Act Fails for Lack of Uniformity , 27 U. Fla. J. Law Pub. Pol’y 81 (2016). Third, bills for “raising revenue” must originate in the House. Although “raising revenue” and “taxing” are not fully the same, the overlap is substantial and can have important consequences. See , Steven J. Willis & Hans G. Tanzler IV, The Wrong House: Why “Obamacare” Violates the U.S. Constitution’s Origination Clause , Wash. Leg. Found. Critical Legal Issues Number 190 (2015).

Fourth, under the Sixteenth Amendment , “income taxes” apply only to “income” “derived” “from a source.” What constitutes an “income tax,” let alone “income,” and what “derived” “from a source” means have been subject to more than one hundred years of debate. Essentially, a taxpayer must experience an “accession to wealth” from an event such as a sale, exchange, or receipt. See , Steven J. Willis & Nakku Chung, Of Constitutional Decapitation and Healthcare , 128 Tax Notes 169, 189-93 (2010). A mere increase in value is not “income” and thus cannot be taxed to humans. For entities, such as corporations, however, a tax on value increases is not an income tax; instead, it is an excise subject merely to uniformity. Flint v. Stone Tracy Co . (1911). To summarize: the power to tax humans differs substantially from the power to tax entities.

Fifth, taxes exist in the presence of various power limitations and personal rights found in the Constitution. Although the application of a tax surely cannot violate the Equal Protection Clause, the Supreme Court has more generally held that the Due Process Clause does not restrict the taxing power. A. Magnano Co. v. Hamilton (1934) (“Except in rare and special instances, the due process of law clause contained in the Fifth Amendment is not a limitation upon the taxing power conferred upon Congress by the Constitution. Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Co. (1916). And no reason exists for applying a different rule against a state in the case of the Fourteenth Amendment.”) Recognizing the lack of constitutional due process protections, Congress statutorily created “collection due process” limitations. See , Steven J. Willis & Nakku Chung, No Healthcare Penalty? No Problem: No Due Process , 38 Am. J. Law & Med. 516 (2013). Those important protections, however, are subject to the whim of future Congresses.

Sixth, arguably taxes must be imposed “for the general welfare.” A close reading of Article One, Section Eight suggests the limitation actually restricts the spending power rather than the taxing power. Interestingly, in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), Justice Ginsburg spoke of the general welfare restriction as applying both to taxing and spending. In contrast, Chief Justice Roberts twice discussed the restriction, but only in terms of the spending power. In any event, this restriction is easily met and thus largely inconsequential.

Lastly, the reach of taxing power limitations remains partially unclear, even 225 years after the adoption of the Constitution. The Federalist Papers spoke of two broad tax categories: direct and indirect, with direct being subject to apportionment and indirect being subject to uniformity. The Constitution, however, does not quite say that. Instead, it first grants Congress broad taxing power. It then requires that direct taxes be apportioned. Next, it requires that duties, imposts, and excises be uniform. It never uses the term “indirect.” This leaves open the question of whether some other type of tax is possible, which need be neither apportioned nor uniform. In 1796, the Supreme Court suggested, but did not hold, that any such “other” tax must be uniform. Hylton v. United States (1796) (Chase, J.). Over the past two hundred years, the Court has routinely spoken of taxes as being either direct or indirect; however, it has yet to consider a case holding “indirect taxes” as encompassing duties, imposts, and excises and nothing more. As a result, the question remains at least technically unresolved.