American Sign Language and Its Importance Essay

Deaf people cannot speak, communicate, and perceive the world fully. They are limited in their perception: vision and sensation are the only primary channels for them to obtain information about the world. However, one of the main problems is the absence of language, which is crucial for developing higher cognitive skills. However, sign language helps maintain and develop the cognitive abilities of deaf people; in that way, they must be taught sign language.

Language deprivation is a significant danger for deaf people: it results from the absence of language learning during childhood. Imagine that the child is growing up in wild conditions, where they cannot hear any speech, any word of mouth. This is what happens to those deaf children who have not learned sign language when they are primarily open to this (N. K. Caselli et al., 2020). All children have increased neurological sensitivity to language learning, which is why they learn languages easier than older people. If they do not learn a language in this period, their cognitive abilities become impaired, not only memory but also the ability to form conscious thoughts. They become more like animals, not humans; this may sound dreadful, but this is the reality of kids who cannot think consciously and memorize what they see. If deaf child is not taught sign language, they must rely only on their vision and fundamental patterns, such as objects’ forms, colors, and quantities. They are similar, in that way, to primitive people who were not able to speak.

Deaf people have weaker memory due to their inability to communicate using ordinary language. Teaching sign language from childhood may help prevent these problems and restore normal memory development. However, their parents, especially those who are hearing, usually have low proficiency in sign language (Bansal et al., 2021). Sometimes they are not bothered to teach their kid sign language, but the consequences of such inactivity are awful. Their working memory becomes weaker, and they cannot operate by word constructions that are accessible to their hearing mates. Compare, thus, the opportunities for such deaf people when they become teens and adults: they will be much worse than those for hearing people. Deaf person is limited not only in their perception but in their language and cognitive abilities; however, this issue may be solved by teaching American Sign Language from childhood.

Consider that American Sign Language is essential for deaf people: probably, even the most necessary skill at all. It allows them to close the gap of language ignorance and learn how to speak even without the ability to hear and produce conscious voices. This is why systems that help deaf children to learn American Sign language are in demand: an example is CopyCat, a sign language recognition system that is easily managed via its visual interface (N. K. Caselli et al., 2020). When deaf children start to learn sign language in early childhood, they have a vocabulary comparable to hearing children (N. Caselli et al., 2021). Thus, it solves all cognitive problems which threaten deaf children, enabling them to grow up as fully conscious human beings with opportunities equal to those of hearing ones.

To conclude, I would emphasize the necessity of American Sign Language development and distribution: without that, our deaf children are fated on ignorance and even semi-wildness. Language is a crucial element of humanity; it is necessary for brain development, as neither memory nor higher brain functions can work without it. Sign language closes the gap of language ignorance, enabling deaf people to learn how to speak and form conscious thoughts. American Sign Language is crucial for the United States deaf community, as it helps them avoid language deprivation and master conscious thinking.

Bansal, D., Ravi, P., So, M., Agrawal, P., Chadha, I., Murugappan, G., & Duke, C. (2021). CopyCat: Using sign language recognition to help deaf children acquire language skills. Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems .

Caselli, N. K., Hall, W. C., & Henner, J. (2020). American sign language interpreters in public schools: An illusion of inclusion that perpetuates language deprivation . Maternal and Child Health Journal , 24 (11), 1323–1329.

Caselli, N., Pyers, J., & Lieberman, A. M. (2021). Deaf children of hearing parents have age-level vocabulary growth when exposed to American Sign Language by 6 months of age . The Journal of Pediatrics , 232 , 229–236.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, February 18). American Sign Language and Its Importance. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-sign-language-and-its-importance/

"American Sign Language and Its Importance." IvyPanda , 18 Feb. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/american-sign-language-and-its-importance/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'American Sign Language and Its Importance'. 18 February.

IvyPanda . 2023. "American Sign Language and Its Importance." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-sign-language-and-its-importance/.

1. IvyPanda . "American Sign Language and Its Importance." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-sign-language-and-its-importance/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "American Sign Language and Its Importance." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/american-sign-language-and-its-importance/.

- Communication in "Through Deaf Eyes" Documentary

- Normal Communication Culture and Deaf Communication Culture

- Reading Ability in Signing Deaf Children

- Language Studies: Prescriptive and Descriptive Approaches

- Phonetics and Phonology of English Word Stress

- What Makes Today’s English Different from Its Early Versions

- “Ooze” Word Origin and Meaning

- The Effect of Childhood Bilingualism on Episodic and Semantic

- Clinics Find a clinic

- Hearing Loss Hearing Loss Help

- Hearing Aids Hearing Aids Help

Hearing centers close to me:

Find hearing clinics in my country:

Hearing loss

- Children's hearing loss

- Noise-related hearing loss

- Middle ear infections

- Diagnosis and treatment

- Meniere's disease

- Assistive listening devices

- Amplified phones

- Captioned phones and caption apps

- Hearing aid compatible phones

- TV hearing aid and listening devices

- Alerting devices

Hearing aids

- Health benefits

- Types and styles

- Reviews and comparisons

- Insurance & financial assistance

- Accessories

- Children's hearing aids

- Cochlear implants

- Bone-anchored hearing systems

- Used hearing aids

- Hearing aid manufacturers

Find a clinic

- Hearing loss overview

- Hearing aids overview

- Types & styles

- Insurance & financial assistance

- Tinnitus overview

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Sign up for our newsletter

- Why you should learn sign language

Featured clinics near me

View Details

We have more hearing clinic reviews than any other site!

The Healthy Hearing Report

Find a trusted clinic near me:

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Toward a Literature of Sign Language

Ross showalter on asl, translation, and deaf culture.

When I was eight, I transferred from a deaf school to my local elementary school. It was a shock; the deaf school, where I was surrounded by deaf classmates and sign language, was the only learning environment I’d ever known. Now I was thrust into a place where I was the only deaf student.

In my new school, I worked with a sign language interpreter who helped me understand everything that was happening around me. When the interpreter wasn’t around, I paid attention to people’s mouths. I pulled clues from their movements and attached words and meaning to them, learning, bit by bit, how to read lips. I quickly tired of this and retreated to the library. With its no-noise policy and shelves of stories, it was a relief. Every recess, I read pages instead of reading lips; the dialogue was laid out for me, and I didn’t have to fill in gaps.

Stories held more meaning for me than people did, and stories were my tool for learning about the hearing world in which I lived. Romance novels taught me about how hearing people moaned in pleasure. Thrillers and mysteries taught me how whispers and secret conversations took place in shadowed hallways or forgotten rooms. Science fiction taught me about the possibility of technology that would foreshadow health concerns, birth defects, lifelong disabilities, and premature death.

Stories also taught me about hearing people’s perceptions about deaf people: we were apparently fragile, strange beings. We were unreachable, untamed, unwilling to bend to popular (read: hearing) opinion. We had personhood, but little agency and autonomy.

By the time I reached college, my signing skills had declined—when I moved away from the deaf school, I replaced signing with hours of speech therapy. When I started signing regularly again, months after I graduated from high school, I struggled to remember basic words and phrasing.

“You’re so English, so robotic,” a college classmate told me once when we were signing together. “Do you even know ASL?”

I felt my back straighten, my defenses up. “Yeah, of course,” I replied. I had started learning language at a deaf school, after all. Sign language had been my first mode of communication, my first entry into any community. “Am I not doing it right?” I asked.

“Use your body. It’s more than just hands.”

As I relearned ASL, I also discovered Deaf authors. I thrilled in finding people like me who were adding nuance and cultural specificity as they wrote about Deaf people. In those stories, Deaf people had power and agency in a narrative. As I adopted a “big-D” Deaf identity (the uppercase D signifies a cultural identity, rather than a medical condition) and grew into a Deaf adult, I turned to literature written by Deaf writers to validate my existence.

When I read their stories about Deaf people who used American Sign Language, my classmate’s words echoed in my mind. You’re so English. Most stories that included American Sign Language (ASL) seemed to only acknowledge ASL on the page as its English equivalent.

The more I read this, the more it dissatisfied me. When I think about sign language, it is entirely on its own, as a language separate from English—even if Deaf students are often taught how to write English in conjecture with ASL. (The deaf school I attended often adopted English grammar rules and syntax in signing to better teach us English.) But to write in English about someone signing is to translate one language to another; when Deaf authors wrote sign language into English, those Deaf authors did so through translation, through the act of converting one language to another.

Most of the time, when we translate something, we think about the act of translation as changing the meaning that comes from one language and conveying it in another language. But the act of translation, particularly in writing, becomes complicated if there is technically no written equivalent of ASL. After all, the translation of a language happens, first, with the acknowledgment of where it comes from.

To think about sign language as something to be translated, rather than transcribed, gives it space on its own terms. For it to be written without an acknowledgment of where it comes from ignores the meaning of sign language itself. Sign language, after all, is the language associated with Deaf culture. It’s a language for Deaf people to communicate with each other outside hearing expectations. Even as Deaf people write in English, we converse in sign. Our stories about Deaf people live on in sign. We gossip in sign. We share experiences in sign. We build connections in sign. Sign language is the lifeblood of Deaf culture and the Deaf community.

If you use sign language, you sublimate yourself within the Deaf community. You step away from English and the mainstream for a space and language outside standard expectations.

To see sign language and English as interchangeable ignores the cultural legacy that comes with sign language. It ignores the storytelling already shared through signing. Most importantly, it ignores the physical specificity of sign language and the body work required in order to sign effectively.

If we use ASL in our stories, we should acknowledge ASL as it is: a language of its own. It is a language of the body. Sign language begins and ends in the body.

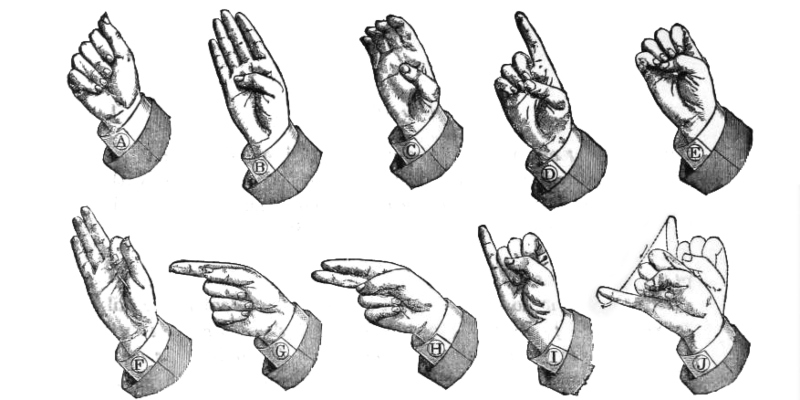

To capture sign language on the page, we need to see sign where it begins; we need to see sign language in the body, written upon the page. We must write about the hands and how they move, the face and its accompanying expression, the speed and force behind every sign. All of that can and should happen upon the page before English translation.

Every conversion needs a beginning point. It’s why we acknowledge translated books’ native languages, and the story’s translators, before the story begins.

Some Deaf authors have tried to bring as much of sign language into English instead of translating sign language into English. Those Deaf authors have tried to retain the traits of sign language while writing in English. One possible approach is to write stories with signed dialogue that adopts ASL grammar in order to literally show how this dialogue looks to a Deaf person. In essence, ASL syntax is rendered in written English. This form is commonly known as ASL gloss. For example, in Raymond Luczak’s Men with their Hands , Luczak translates a character’s signing the simple phrase, “sorry I’m late,” into, “Sorry-sorry me l-a-t-e.”

Sign language begins and ends in the body.

This approach of rendering signed dialogue gets the grammar and spelling of ASL on the page, but I would argue that it doesn’t fully acknowledge the spatial and physical needs of ASL, and it also misses the emotional nuance of this language. Someone who doesn’t know ASL wouldn’t know why sorry (a sign that’s made with your fist rubbing in a circle upon your chest, as if you’re washing your heart) is repeated twice, or why the word late is spelled out.

They wouldn’t realize the specificity of what is being communicated when a person repeats a sign or spells out a word. This approach, in effect, portrays sign language as akin to English, albeit following different syntax rules. There is little acknowledgment of how the body works to create the dialogue on the page, and why.

For someone to know what happens with the character’s body and just how they sign, they would have to know sign language to the point where they could visualize the phrases in their mind.

Therein lies the contradiction of this method: to render ASL in written English with its syntax intact is to create a strange tension. There is the grammar of ASL, preserved and captured only in syntax—but syntax is only part of a language. To try to render ASL in writing is to suspend yourself halfway between ASL and English.

To do justice to ASL, we need to treat it on its own terms.

ASL comes from the body. Signs are made, not just with hands, but with fingers, arms, chests, jawlines, faces. ASL teachers often emphasize facial expressions and the direction and spatial specificities of any given signs. And, depending on the context and the emotional climate, a sign could either be delivered languidly or quickly. A sign could be delivered, heavy with tension, the hand vibrating with emotion. Before we consider approaching English, we need to think about what the body is doing. What does the body do? How does the hand form the shape? Is the character struggling to sign? Is whoever watching noticing? Do they care?

Before we think about sign language as dialogue, let’s think about it as action. Sign language is not only language. It is an action you take with a body, an action that conveys meaning. It is an action that grounds you in Deaf ideals and Deaf community. Sign language is our language and our way to communicate. It is our way of interacting with the world around us. If we are to write American Sign Language, we must bring the body in first. We must foreground the body and think about what it does, first, before we move to any form of English. Otherwise, sign language exists in a liminal space.

As someone who existed in a liminal space before finding community and finding communication, I want sign language in literature to have its place as its own language. I want it to take up space on the page, as it is. I want to ground it in where it begins. I don’t want to read about it only in a language that either converts it or strips it of nuance. Just as I found a space, eventually, where I could grow into my identity as a Deaf person, I want the written page to be a space for sign language and its idiosyncrasies to spread out and be seen as what it is: a language that is acknowledged where it begins.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Ross Showalter

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Can Putin Risk a Nuclear War? Can the Rest of Us?

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Notes on the Culture

American Sign Language Finds Its Spotlight

Across all performative mediums, today’s Deaf creatives are celebrating, protecting and sharing their distinct mode of communication.

By Jake Nevins

LAST AUGUST, several months into lockdown, Raven Sutton posted a short clip on TikTok. In it, Sutton, a 25-year-old Black Deaf dancer living in Washington D.C., covers Cardi B ’s song “ WAP ” in American Sign Language, or A.S.L., which she’s used, alongside English, her entire life. Wearing a tan crop top and hoop earrings, Sutton signs Megan Thee Stallion ’s verse, maintaining coy eye contact with her camera as she reimagines lines like “Gobble me, swallow me, drip down the side of me” for a Deaf audience. Sutton, of course, can’t “hear” the music in a conventional sense. But having danced since childhood, she’s found ways to channel her intuitive feel for rhythm through the vast, lexically complex language of sign, paying close attention to the vibrations of the bass pounding through her speakers or holding an eight-count so she knows when the words begin. Sutton posted the 35-second video and then closed the app for a few hours to get on with her day. She returned to thousands of likes, comments and, eventually, a retweet from Cardi B herself.

For hearing audiences, long dismissive or at least ignorant of A.S.L. and its bountiful possibilities for creative expression, the video piqued curiosity. Some asked if Sutton was really Deaf, so exacting was her choreographed interpretation. Others, Sutton told me in a video call moderated by a sign language interpreter (as all interviews for this article were conducted), wondered why she signed the song’s titular refrain several different ways, once connecting both hands to make a V shape, another time gyrating her hips back and forth. Such questions were expected, given how widely misunderstood American Sign Language remains, more than 200 years after it was enshrined as the language of the Deaf. It is not merely English in gestural, transliterated form, as hearing folks often assume, but a visual language no less grammatically and syntactically evolved than any other, whose descriptions and sentence constructions utilize space and time multidimensionally. Sign tends to set the scene, placing the relevant characters in a given sentence in spatial relation to one another, much like stage directions. Further distinguishing it from English is A.S.L.’s topic-comment structure, in which the object of a sentence is often introduced before it’s described: If someone wishes to say they “liked a book” in sign, they’d mention the book before they do their feelings about it. For Sutton, the song’s irreverent hook could take numerous shapes in A.S.L., depending on the context. “There’s a part where Megan is, you know, talking about different types of … ” she says with a laugh, hesitant to invoke the song’s title. “But she’s talking about different scenarios, right? She’s talking about him paying off her college, she’s talking about taking pictures on his phone.”

Since going viral, Sutton has continued to use TikTok both to showcase her dance and to educate her large contingent of hearing followers, placing her among a wave of Deaf creatives who, consigned to their homes during the pandemic, are leveraging their popularity to advocate for Deaf awareness and, by extension, a greater understanding of sign language in the culture at large. “Digital communication methodologies have been something that Deaf people adopted very quickly,” says Carrie Lou Garberoglio, 41, director of the National Deaf Center in Austin, Texas, where the first-ever A.S.L.-accessible video game, a choose-your-own-adventure called Deafverse , was developed in 2019. Early on, Deaf people embraced teletypewriter (TTY) technology and emojis, and they’ve long relied on the internet to foster intracommunity rapport. As social media has proliferated, it’s functioned as a conduit for these efforts, allowing Deaf folks to bypass the gates of institutional power that have traditionally held them back.

But one does not have to be online to witness this upsurge in Deaf content and sign language representation, itself both a part of and distinct from the groundswell of stories about differently abled people that have arisen over the last decade. After years on the margins, the Deaf community is experiencing a series of firsts: a Deaf contestant on the latest season of “ The Bachelor ”; Marvel’s debut Deaf superhero, Makkari, played by the Tony-nominated actress Lauren Ridloff in “The Eternals,” out later this year; and the record-breaking $25 million sale of the film “ CODA ,” short for Child of Deaf Adults, to Apple Studios after its rapturous reception at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. Even state-by-state coronavirus briefings, which have made minor celebrities of the sign language interpreters relaying life-or-death information to viewers, have shone a light on A.S.L. and the myriad ways Deafness is sidelined. Last fall, in the first case of its kind, the National Association of the Deaf successfully sued the Trump administration for failing to provide an interpreter at its Covid-19 briefings. Meanwhile, less than a week after the inauguration, President Biden’s press secretary announced that an interpreter would be present at all of the administration’s daily press conferences, a first in presidential history. For several years now, these breakthroughs have seemed imminent, a matter not of merit but of opportunity and resources. But it’s no coincidence that they’re all coalescing now, following a time of pandemic, protest and social upheaval that’s provoked frank conversations about access and equity, and also a mass migration to our screens, wherein the visual has supplanted the auditory, imbuing our attempts at understanding each other with a renewed sense of urgency and empathy. All of us, living under circumstances so inhospitable to genuine human connection, have adopted new modes of engagement; from that, there’s emerged a recognition that language need not be the exclusive provenance of sound or even text but of signs, too.

In conversations with many of the Deaf community’s foremost creatives and de facto activists, there’s a sense of both enthusiasm and wariness, a desire to bridge the gap between the Deaf and hearing worlds and an equally strong sense of exhaustion, accumulated over time, at the patience such a merger would require. “Sometimes,” says the 40-year-old Berlin-based visual and sound artist Christine Sun Kim , “hearing people don’t know what to do when they encounter a Deaf person, and we end up having to communicate their way.” The animating spirit of much of Kim’s work, particularly her series “Trauma, LOL,” recently on view at the François Ghebaly gallery in Los Angeles, is a sense of enervation at this cycle, of “having to explain and explain and explain to people who are not Deaf, and who are kind of creating more work for us.” Though art institutions have been more hospitable since Kim was named a TED Fellow in 2013, and included in the Whitney Biennial six years later, she’s often found herself justifying the need for an interpreter or feeling infantilized by curators who imply she’s just lucky to be included. “We have to protest more just to get basic needs met,” she says. “If it were completely up to me, I wouldn’t want to be an activist.”

Over generations of gradual but often arrested progress, the Deaf community has remained self-sufficient, justifiably suspicious of the intercessions of hearing people. As a result, there is a sense of proprietorship about A.S.L., fortified when they see it mocked or commodified. It was only eight years ago that Deaf people watching Nelson Mandela ’s memorial service saw their language bastardized by a sign language interpreter whose gestures were convoluted and unintelligible. Now, according to a 2018 report by the Modern Language Association, A.S.L. is the third-most commonly studied non-English language in American higher educational institutions, after Spanish and French, and across the internet one can find scores of instructional videos taught by hearing people, a reliable if bothersome metric by which to gauge the language’s mainstreaming. “Oftentimes, it’s not even accurate — facial expressions, body movements, location, hand shapes, all of that is important when you’re teaching,” says Sutton, who attended Washington, D.C.,’s Gallaudet University, the country’s first and only liberal arts college for the Deaf. “What they end up doing is using our culture and our language for clout.”

TO UNDERSTAND THESE misgivings, one must know the history of sign language, which is characterized by sharp vicissitudes of embrace and oppression. Sign language arrived in America by way of France, where, in the mid-18th century, under the auspices of the religious educator Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Epée, it became the primary mode of instruction for the French Deaf. Until then, sign language had existed as a kind of informal mixture of the community’s Indigenous signs with French grammar. De l’Epée, upon encountering two Deaf girls and watching them communicate, found that the Deaf, then seen as ineducable, were in fact adroit students, so he began applying a more sophisticated structure to their native hand signals and gestures. His methods were formalized in 1760, with the founding of the first free school for the Deaf, later to be known as the National Institution for Deaf-Mutes in Paris. “The abbé de l’Epée was not the inventor or creator of this language,” wrote Pierre Desloges, whose 1779 account of that period reflects the spirited beginnings of Deaf enfranchisement. “Quite the contrary, he learned it from the Deaf; he merely repaired what he found defective in it.”

After de l’Epée’s death in 1789, this effort was carried on by the grammarian Roch-Ambroise Cucurron Sicard, known as Abbé Sicard, a mentee of his who would usher in what Oliver Sacks , in his seminal book “Seeing Voices” (1989), called “a sort of golden period in Deaf history,” whereby sign language was recognized as the “natural” language of the Deaf, not a mere childlike form of pantomime. Sicard would eventually meet Thomas Gallaudet, an American educator who helped establish, in 1817, what would become the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Conn. What followed was a cross-pollination — between French sign language and the systems of home sign that already existed in American towns with large Deaf populations, like Chilmark, Mass., on the western edge of Martha’s Vineyard; Henniker, N.H.; and Sandy River Valley, Maine. Ultimately, these disparate strains of sign would merge to create American Sign Language.

But soon after Congress, in 1864, authorized the creation of the first federally chartered Deaf institution for higher learning, which would become Gallaudet, prominent oralists like Alexander Graham Bell , following in the tradition of the educational reformer Horace Mann, advocated for deaf assimilation through speech and lip reading. Bell himself had a fraught relationship with Deafness that preceded his telephonic innovations: Both his mother and wife were Deaf, and he saw their impairments as something to be eradicated, going so far as to speak out against Deaf intermarriage in an 1883 speech at the National Academy of Sciences.

For Bell’s part in thwarting sign language education and undermining Deaf culture, Kim considers him to be the community’s greatest historical scourge, a conviction that inspired the site-specific mural at Washington University in St. Louis that she unveiled this past February. A 25-foot-tall work that imagines three variations of Deaf-specific afflictions, titled “ Stacking Traumas ,” features musical notes placed atop one another, referencing a collective indignity. The first is “Dinner Table Syndrome,” or the difficulty of holding court in hearing settings. The second reads “Hearing People Anxiety,” an agita born from navigating the chasms between Deaf and hearing people. At the topmost rung is “Alexander Graham Bell,” his name looming over the others, a hurdle to be cleared.

THIS PAST FALL, Netflix released the first season of the docu-series “Deaf U,” a soapy look at the lives of several undergraduates at Gallaudet, executive produced by the 31-year-old Deaf actor Nyle DiMarco, who graduated from the university in 2013. If the series appears at first like your garden-variety campus reality show — complete with love triangles, unwanted pregnancies and daddy issues — it’s those qualities that make the show’s existence remarkable, radical in its familiarity: Alongside the spectacle of young-adult melodrama is a sense of gravitas, a thread from past to present, for Gallaudet is to the modern Deaf movement what Stonewall was to gay rights. There, in the spring of 1988, the student body successfully protested to demand the resignation of its hearing president and the installation of the school’s first Deaf leader.

By depicting the familiar theater of college life through sign, “Deaf U” doubles as a rigorous look at A.S.L. in practice, and the social stratification that’s entrenched within it. The generationally or prelingually Deaf, with their mastery of sign language, sit at the highest rungs, while some students are seen as not Deaf enough , particularly those who wear hearing aids or cochlear implants. There’s Alexa, the white daughter of Deaf parents and Gallaudet graduates, whose pedigree puts her among the school’s Deaf “elite,” and two of the young men she dates, Rodney and Daequan, both of whom are Black and partially hearing, prompting frank conversations about the fence-straddling this requires of them within a cloistered ecosystem. While filming, the mostly Deaf production team would often call a pause, moving from one unremarkable conversation to a juicier one being held elsewhere. “A lot of our language is based on the face,” DiMarco says. “It’s a subtle movement or twitch of the eyebrow … so it was [crucial] that Deaf people behind the camera could pick up on those nuances.” During one scene, we see Alexa, seated on a bench in the campus courtyard, crane her neck around to make sure no one is in eyeshot before asking Daequan if he got her pregnant on purpose, signing the words down by her lap, as if to whisper.

One byproduct of “Deaf U” is a better understanding of these idiosyncrasies, embedded in every language but often overlooked in A.S.L., which must contend with the assumption of its inscrutability. Language, its prescriptive parameters drawn by the hearing, has long been considered the domain of sound but, as Kim explains in her 2015 TED Talk , sound “can be felt tactually, or experienced as a visual or even as an idea.” It was not until 1960, with the publication of the linguist William Stokoe ’s monograph “Sign Language Structure,” that A.S.L. would recover from the deleterious effects of the oralist movement and be treated academically as a bona fide language. In the six decades since, as Deaf people were once again encouraged to communicate in their native language, there has emerged an understanding of Deafness not as a handicap but as a veritable culture, which, in turn, has nurtured an embrace of its primary exponent: sign language. But it’s no accident that this is happening at a time when all American language, signed or not, is expanding and evolving — look, for instance, to the ways in which Black, Latino and queer vernaculars have filtered into common parlance.

That’s why there is something revolutionary about all the A.S.L. content on TikTok, where videos are often supplemented with captions and viewers are just as likely to encounter a brief tutorial in sign language as they are a video of a Deaf person using it at a drive-through. The app functions as a kind of permanent archive of a visual language that is by nature fundamentally untranscribable, and thereby always at risk of erasure. At the beginning of her videos, the 22-year-old Texas-based Nakia Smith dabs lotion on her hands, a habit one might liken to throat clearing. Smith, part of the fourth generation of Deafness in her family, instructs her followers in the intricacies of Black American Sign Language, a dialect she describes as “A.S.L. with seasoning,” or broadcasts the failures of accessibility — videos without captions; classrooms without interpreters — that still blunt Deaf integration.

After a video of Smith and her grandfather sharing the history of B.A.S.L. went viral last October, Netflix got in touch, and she and the streaming service began a social media partnership, the first clip of which shows Smith explaining the segregationist roots of B.A.S.L., the dialect historically used in Black Deaf circles. Smith, like many Black signers, code-switches between A.S.L. and B.A.S.L., depending on the person with whom she’s speaking; users of B.A.S.L., she explains, will place their signs around their foreheads rather than their torsos, and where A.S.L. often uses only one hand, B.A.S.L. employs two. That so little linguistic scholarship of the dialect exists today is the consequence of both audism and racism. But last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, which included Black Deaf folks among its prominent participants, has galvanized the cause of Black Deaf studies, prompting recent scholarship, as well as pushes for inclusion, including the establishment earlier this year of the Center for Black Deaf Studies at Gallaudet, and the release of various video campaigns foregrounding the movement for Black Deaf empowerment.

Smith and others use their growing platforms not only as a loudspeaker but as a form of preservation. But how does one safeguard a visual language whose complexity is distorted by the written word? These issues are especially salient in theater, since videos of A.S.L. productions protect only the footage itself, not the words being signed. For this reason, the 41-year-old New York-based Deaf playwright Garrett Zuercher writes in both English and A.S.L., a laborious if not atypical process to which he’s become accustomed. “My whole experience has been bilingual, which is very common in the Deaf community,” he says.

When the pandemic first began, and live performances migrated to online platforms, Zuercher noticed that even filmed theater, outfitted with closed captions for hard-of-hearing viewers, was inadequate. Though many Deaf creators speak to the incidental virtues of the quarantine-born explosion in video conferencing — their interpreters can log on instead of traveling, and the last several years have seen marked improvements in the availability of subtitles and assisted-listening technology — that medium, too, can undermine the multiplicity of signed communication. A few weeks into lockdown, Zuercher and several others in the Deaf theater community convened remotely to watch Stephen Sondheim ’s “ Sweeney Todd ” (1979). All Sondheim aficionados, they noted how often the closed captions failed to account for the overlapping density of his dialogue and libretto. “It felt like a watered-down version of Sondheim,” Zuercher told me.

Soon after, he and his friends, including Ridloff, decided to put on their own reading of “Sweeney Todd,” this time in sign, an endeavor that functioned like a restoration: The calculated cadences that had been lost in the subtitles were made clear visually. The group put on another two shows — “Company” (1970) and “Into the Woods” (1986) — and with that, a theater collective, now known as Deaf Broadway , was born, a kind of East Coast counterpart to the 30-year-old Deaf West Theatre in Los Angeles. While closed captions are an invaluable asset to hard-of-hearing viewers, the effects of enjoying a production in one’s native tongue were invigorating. One mother got in touch with Deaf Broadway to let them know that though her hearing children were fans of the 2014 film adaptation of “Into the Woods,” it was not until seeing the signed iteration that her Deaf child connected with it, too. To Zuercher, “that is proof that captions don’t do it — access in sign language is what really provides understanding.”

SO, TOO, DOES seeing oneself onscreen, though for the 17-year-old Pennsylvania-based actor Millicent Simmonds , those moments of recognition have always been scarce. When Deaf characters have been depicted onscreen, they’re often played by hearing actors; even in “Children of a Lesser God,” for which the Deaf actor Marlee Matlin received an Academy Award in 1987, dialogue in American Sign Language is frequently obscured by the film’s editing. It’s this history that’s motivated Simmonds to see her own work — which includes roles in “Wonderstruck” (2017), “ A Quiet Place ” (2018) and its sequel , to be released later this year — as a corrective. Without sign language, she says, “I wouldn’t have a relationship with my own family, I wouldn’t have communication.”

This process of coming to recognize Deafness as a way of life, rather than a lesser one, likewise unfolds in the recent film “ Sound of Metal ,” directed by Darius Marder and starring Riz Ahmed , who learned sign language for the role. About halfway through the film, Ahmed’s character, Ruben, who has lost his hearing after years spent touring as a heavy metal drummer, decides to get a cochlear implant, a neuroprosthetic device that stimulates the auditory nerves to create the sensation of hearing. But among his cohabitants at the Deaf commune where he spends much of the film, this procedure is seen as an affront. “Everybody here shares in the belief that being Deaf is not … something to fix,” his mentor tells him.

Therein lies an enduring ideological divide that “Sound of Metal” broaches but doesn’t adjudicate. Instead, the film makes an argument for a life lived richly, with sign language but without sound. Deafness is not sanitized of hardship; having spent countless hours in audiology consultations myself on account of my own hearing deficit, I can say Marder deftly captures the essential alarm and shame of that ordeal, particularly as Ruben first experiences sound as it’s communicated through his implant, somewhat garbled and motorized, not like he remembers. But neither is Deafness pathologized, as it so often is onscreen, or equated with a kind of sensory or spiritual impoverishment.

To help faithfully represent the Deaf experience, Marder enlisted Jeremy Lee Stone , 32, who has a minor role in the film and taught Ahmed sign language at the actor’s Brooklyn home. Their initial conversations had to do with Deaf identity, “capital D, relating to the culture and history, versus lowercase D, meaning deaf in the medical sense,” as Stone distinguishes it. Gradually, he submitted the actor to a rigorous process of A.S.L. instruction, wherein Ahmed had to, as Stone says, “remove his identity and become a different character.” At a cafe, when Stone and Ahmed were practicing sign language and a waiter came by to take their orders, Stone would not let Ahmed speak on their behalf, making him order his drink just as his character would. “I wanted him to experience … that frustration of not being able to communicate clearly, the misunderstanding that happens,” Stone says.

As we spoke via Zoom, I asked what he thought was the most common misperception about A.S.L. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then “one sign is worth a million,” he eventually answered, though Stone realized immediately that the adage did not truly demonstrate the vitality of what he refers to as a multidimensional language, through which meaning, concepts and behaviors that might require several sentences to describe verbally can be expressed with the flick of a wrist, a furrow of the brow, the body acting as a proscenium before which one can stage an infinite number of scenes. “It’s hard to describe,” he added. Then he thought better of it and showed me instead.

Explore T Magazine

A Forest Retreat in ‘Tokyo’s Backyard’: Here’s how the architect Terence Ngan and the interior designer Ed Ng made a home for themselves in the woods .

Artist Questionnaire: The artist Charles Gaines discussed his new work at the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Alabama, the development of his practice and taking drum lessons from Jimmie Smith.

Skin Care Routine for Adult Acne: Here is an expert-approved guide to the most effective products and techniques for dealing with stubborn breakouts at home.

An Antidote to Loneliness: Patrick Carroll began making textiles during lockdown . Last year, several of them appeared at a JW Anderson runway show.

The 25 Essential Italian Pasta Dishes: Two chefs, one cookbook author, a culinary historian and a food writer made a list of the country’s most delicious meals , from carbonara in Rome to ravioli in Campania.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

American Sign Language

On this page:

What is American Sign Language?

Is sign language the same in other countries, where did asl originate, how does asl compare with spoken language, how do most children learn asl, why emphasize early language learning, what research does the nidcd support on asl and other sign languages, where can i find additional information about american sign language.

A young boy signs "I love you."

American Sign Language (ASL) is a complete, natural language that has the same linguistic properties as spoken languages , with grammar that differs from English. ASL is expressed by movements of the hands and face. It is the primary language of many North Americans who are deaf and hard of hearing and is used by some hearing people as well.

There is no universal sign language. Different sign languages are used in different countries or regions. For example, British Sign Language (BSL) is a different language from ASL, and Americans who know ASL may not understand BSL. Some countries adopt features of ASL in their sign languages.

No person or committee invented ASL. The exact beginnings of ASL are not clear, but some suggest that it arose more than 200 years ago from the intermixing of local sign languages and French Sign Language (LSF, or Langue des Signes Française). Today’s ASL includes some elements of LSF plus the original local sign languages; over time, these have melded and changed into a rich, complex, and mature language. Modern ASL and modern LSF are distinct languages. While they still contain some similar signs, they can no longer be understood by each other’s users.

ASL is a language completely separate and distinct from English. It contains all the fundamental features of language, with its own rules for pronunciation, word formation, and word order. While every language has ways of signaling different functions, such as asking a question rather than making a statement, languages differ in how this is done. For example, English speakers may ask a question by raising the pitch of their voices and by adjusting word order; ASL users ask a question by raising their eyebrows, widening their eyes, and tilting their bodies forward.

Just as with other languages, specific ways of expressing ideas in ASL vary as much as ASL users themselves. In addition to individual differences in expression, ASL has regional accents and dialects; just as certain English words are spoken differently in different parts of the country, ASL has regional variations in the rhythm of signing, pronunciation, slang, and signs used. Other sociological factors, including age and gender, can affect ASL usage and contribute to its variety, just as with spoken languages.

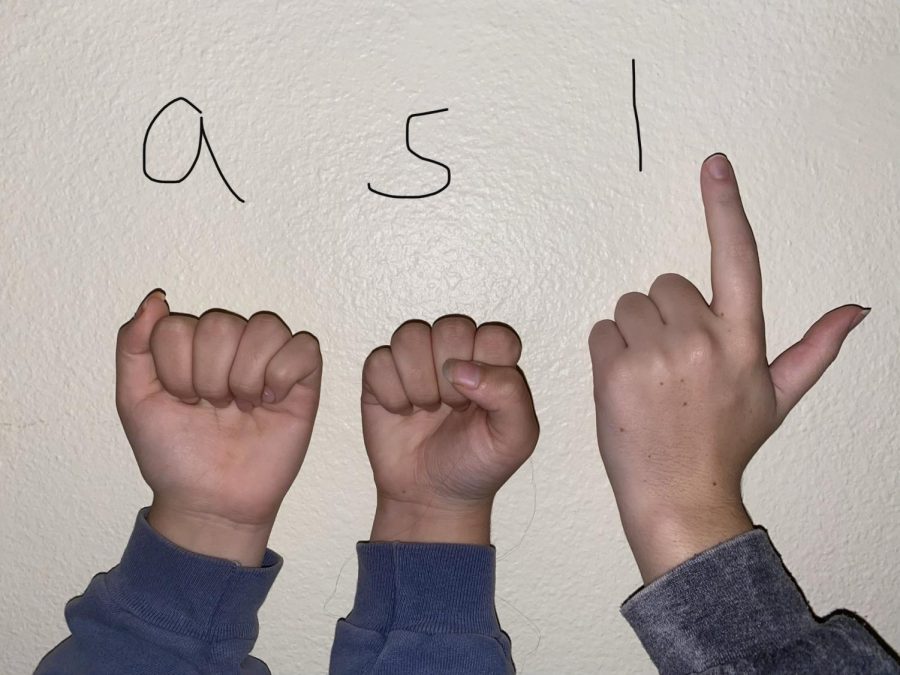

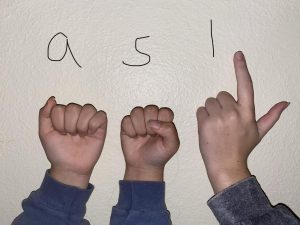

Fingerspelling is part of ASL and is used to spell out English words. In the fingerspelled alphabet, each letter corresponds to a distinct handshape. Fingerspelling is often used for proper names or to indicate the English word for something.

Parents are often the source of a child’s early acquisition of language, but for children who are deaf, additional people may be models for language acquisition. A deaf child born to parents who are deaf and who already use ASL will begin to acquire ASL as naturally as a hearing child picks up spoken language from hearing parents. However, for a deaf child with hearing parents who have no prior experience with ASL, language may be acquired differently. In fact, 9 out of 10 children who are born deaf are born to parents who hear. Some hearing parents choose to introduce sign language to their deaf children. Hearing parents who choose to have their child learn sign language often learn it along with their child. Children who are deaf and have hearing parents often learn sign language through deaf peers and become fluent.

Parents should expose a deaf or hard-of-hearing child to language (spoken or signed) as soon as possible. The earlier a child is exposed to and begins to acquire language, the better that child’s language, cognitive, and social development will become. Research suggests that the first few years of life are the most crucial to a child’s development of language skills, and even the early months of life can be important for establishing successful communication with caregivers. Thanks to screening programs in place at almost all hospitals in the United States and its territories, newborn babies are tested for hearing before they leave the hospital. If a baby has hearing loss, this screening gives parents an opportunity to learn about communication options . Parents can then start their child’s language learning process during this important early stage of development.

The NIDCD supports research on ASL, including its acquisition and characterization. Funded research includes studies to understand sign language’s grammar, acquisition, and development, and use of sign language when spoken language access is compromised by trauma or degenerative disease, or when speech is difficult to acquire due to early hearing loss or injury to the nervous system.

Teenage boy having a conversation using sign language.

Study of sign language can also help scientists understand the neurobiology of language development. In one study, researchers reported that the building of complex phrases, whether signed or spoken, engaged the same brain areas. Better understanding of the neurobiology of language could provide a translational foundation for treating injury to the language system, for employing signs or gestures in therapy for children or adults, and for diagnosing language impairment in individuals who are deaf.

The NIDCD is also funding research on sign languages created among small communities of people with little to no outside influence. Emerging sign languages can be used to model the essential elements and organization of natural language and to learn about the complex interplay between natural human language abilities, language environment, and language learning outcomes. Visit the NIH Clinical Research Trials and You website to read about these and other clinical trials that are recruiting volunteers.

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

For more information, contact us at:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse 1 Communication Avenue Bethesda, MD 20892-3456 Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044 Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055 Email: [email protected]

NIH Publication No. 11-4756 March 2019

*Note: PDF files require a viewer such as the free Adobe Reader .

Sign Language Studies

ISSN 0302-1475

Editors: Erin Wilkinson , University of New Mexico Pilar Piñar , Gallaudet University

SPECIAL ISSUE

The first wave of sign language research, selected memoirs.

Guest Editors:

Penny Boyes Braem

Virginia volterra, robbin battison, nancy frishberg, carol padden.

"A truly stunning collection from the who's who of early sign language research, and a very valuable gift to anyone wanting to learn about the sign language research community." — Ceil Lucas, Professor Emerita, Gallaudet University

From the Introduction

"Fifty years after William Stokoe founded Sign Language Studies ( SLS ) in 1972, we have reason to give thanks for a half-century of research and discovery, and to reflect on its origins. Because much has changed since those early days. And many stories have not yet been told. . . . The resulting collection serves as historical documentation of how a new research field is born. We believe that the personal details and variety of motivations and settings will interest a wide range of readers—not only the veterans of the field who will recognize their pioneering friends, but also younger researchers seeking insights into the roots of sign language linguistics and related fields."

This special issue is included as part of the SLS subscription.

If you would like to purchase a digital copy ($24/individuals) , please click here.

Aims & Scope Issues Submissions Manuscript Submission Guidelines Book Review Guidelines Special Issue Proposals Subscribe Purchase Digital Content The Editors Customer Service

Aims & Scope

Founded by William C. Stokoe, known by many as the father of the linguistics of American Sign Language, this quarterly journal presents a singular forum for groundbreaking research on the language, culture, history, and literature of signing communities and signed languages. The first journal published in the field, SLS continues to offer fresh content with a uniquely international, multidisciplinary focus.

" “Time and again, Sign Language Studies features some of the best articles in the field. The editing is solid, the issues are always pertinent and whether about a sign language of the world, or about the people who use it, the topics are invariably interesting.” —Carol Padden, Professor, Department of Communication, University of California, San Diego "

A common misconception about sign language is that it is universal. Check out our #SLStudies map to see the many different sign languages that are used across the globe! These are the sign languages that have been represented in Sign Language Studies .

New Features in Sign Language Studies

An annual list of completed sign language or sign language-related dissertations and master’s theses.

A section called In Brief , which features short pieces that are 3–4 pages in length, written by undergraduate and graduate students, that are not yet full articles but contain interesting information that should be shared.

History of SLS

William C. Stokoe began publication of Sign Language Studies in 1972. With the encouragement of Thomas Sebeok, Stokoe created this seminal journal as an outgrowth of his pioneering studies of the structure of American Sign Language and the dynamics of Deaf communities. From then until now, SLS has presented a unique forum for revolutionary papers on signed languages and other related disciplines, including linguistics, anthropology, semiotics, deaf studies, deaf history, and deaf literature.

After a three-year hiatus, Sign Language Studies commenced publication in the fall of 2000. The new editor was David F. Armstrong, an anthropologist and author of Original Signs: Gesture, Sign, and the Sources of Language and coauthor of Gesture and the Nature of Language with Stokoe and Sherman Wilcox. A long-time collaborator with Stokoe, Armstrong became a member of the SLS editorial board in 1986.

David Armstrong stepped down as editor at the end of 2009 and was succeeded by Ceil Lucas, Professor Emerita, Gallaudet University, who is the coauthor and editor of many Gallaudet University Press books, including Linguistics of American Sign Language and What’s Your Sign for PIZZA? , and is the founding editor of the Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities series. She is also the author of a memoir, How I Got Here .

In 2022, the editorship moved to Erin Wilkinson and Pilar Piñar.

Back to top

Table of contents and article abstracts for current and previous issues are available at Project MUSE . All issues are fully searchable.

Search Project MUSE®

Publisher Limited To: Gallaudet University Press

Journal Limited To: Sign Language Studies

https://muse.jhu.edu

Submissions

Articles, book reviews, and other pieces.

Sign Language Studies invites submissions of high-quality papers focusing on research relevant to signed languages and signing communities from around the world. Topics of interest include linguistics, corpora development, anthropology, deaf culture, deaf history, and deaf literature. We are also interested in ongoing research reports, shorter pieces that are not full-fledged articles but contain information that should be shared with signing communities, and book and media reviews.

Articles and essays are welcomed from all countries. All submissions must be in English. Authors should submit papers electronically to [email protected] and [email protected] .

Original scholarly articles and essays relevant to signed languages and signing communities.

Word count limit: 8,000 to 10,000 words, including references

Ongoing Research Reports

Status reports of research being done on signed languages or issues relevant to signing communities.

Word count limit: 3,000 to 6,000 words

Pieces that are shorter in length (can be written by undergraduate and graduate students) and are not yet full articles but contain interesting information that should be shared.

Word count limit: 750 to 3,000 words

Book Reviews

Reviews of relevant books.

Word count limit: 600 to 1,000 words

Every fall, SLS publishes a list of doctoral dissertations related to signed language and signing communities that have been successfully defended that year. Please send citations for dissertations you’d like to see included in the list by early August in the following format:

Author. Year of Defense. Title. University. Database where the dissertation can be found or ProQuest order number if available.

Note: Please do not send full text of the dissertation.

Manuscript Submission Guidelines

A manuscript will be accepted for review on the condition that it has not been published or is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. Once an article is accepted, the author will be asked to assign copyright to Gallaudet University Press in order to protect the article from copyright infringement. Gallaudet University Press will not refuse any reasonable request by authors for permission to reproduce their contribution to Sign Language Studies .

All articles will undergo peer review, be professionally edited and typeset, and be distributed in print and electronic format.

Length. Manuscripts can be between 8,000–10,000 words including the references. After an article has been accepted, the author will be asked to send the final version as an attachment to an email with the article saved in Word or Rich Text Format.

Format. The title of the article/essay and the author’s name, affiliation, and contact information (including email address) should be on page 1. This is the only page where the author’s name should appear.

Headings. Please do not number your headings (i.e., “3.1. Data Collection”). Also, please do not include cross-referrals to sections in your article's text (i.d., “see section 4.1.2”). If this appears, it will be removed during copy editing. Please do indicate head levels by either formatting them differently (bold, all caps for first-level heads, bold, initial cap/lowercase for second-level heads, bold italics for third-level heads) or by adding bracketed codes:

- <1> = first-level heads

- <2> = second-level heads

- <3> = third-level heads

- <4> = fourth-level heads.

Tables and Figures. All tables and figures should be mentioned in the text, should include a title or caption, and should be numbered consecutively. Tables should not be embedded in the running text but appended at the end of the article. Figures should not be embedded in the file with the text. They should be submitted as separate files in the format in which they were created. Do not embed the figures in a Word document. All figures should be in reproducible form, with type that is clearly legible at a reduction of 50 percent.

Endnotes and Footnotes. Footnotes should be used sparingly and should be numbered consecutively. Endnotes should also be numbered consecutively and should follow the form detailed in The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) , 17th ed. Endnotes should be placed together in a section following the main body of the text.

References. All sources cited in the text should appear in the reference list at the end of the chapter. Text citations should include the author, year of publication, and page number, where applicable: (Wilcox 2000, 120). Books and articles listed in the references should take the following form:

Brueggemann, B. J. 1999. Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Winston, E., and C. Monikowski. 2000. Discourse Mapping: Developing Textual Coherence Skills in Interpreters. In Innovative Practices for Teaching Sign Language Interpreters , ed. C. Roy, 15–66. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Stokoe, W. C. 2000. Commentary. Sign Language Studies 1(3): 5–10.

For other types of citations, consult The CMOS , 17th ed.

Permissions. Authors are responsible for obtaining permission to reprint tables, figures, illustrations, and large excerpts. Copies of the permission letters must accompany the manuscript.

Proofs. One set of proofs will be sent to the lead author. Authors are responsible for proofreading and returning the proofs within three days of receipt.

Graphics. Please submit all graphics in a size that is clearly legible when reduced 50 percent. Please note that all graphics must be in grayscale or black and white. Color graphics are not acceptable. Line art should be saved in files separate from the article, preferably in Adobe Illustrator .eps files. Photographs should be scanned as TIFF or PNG files—do not send them as JPEGs.

Please make a separate file for each graphic submitted. Do not embed the graphic in a Word document (this reduces resolution and will affect how well the graphic appears on the printed page). When scanning line art or halftones for submission, please scan to 300 dpi. This is the minimum resolution required for good printing results.

Book Review Guidelines

Sign Language Studies considers the following genres for book reviews:

• Scholarly monographs and contributed volumes on sign language linguistics and/or sociolinguistics, deaf history, deaf education, deaf studies, deaf literature studies, sociology, anthropology, psychology

• Nonfction—memoirs, biographies, autobiographies

• Fiction and poetry

• Alternative media—videotexts, online multimedia texts

• Double-spaced 12 pt. Times Roman text.

• Length: 800–1,200 words (does not include references).

• Include a one-sentence author biography for the reviewer.

Example: Christina Young is an associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Virginia.

Bibliographic Citation:

The book review should begin with a bibliographic citation of the book under review following the format below:

Author/Editor’s name(s). (Translator’s name, if required). Book title. Publisher (Page count, price, ISBN, additional format, price, ISBN). URL or DOI if available.

Example: Mary H. Wright. Sounds Like Home: Growing up Black and Deaf in the South. Twentieth Anniversary Edition. Gallaudet University Press (282 pages, $32.95, paperback: ISBN 978-1-944838-58-4, ebook: ISBN 978-1-944838-59-1).

Writing a scholarly book review requires careful analysis, critical thinking, and the ability to communicate your thoughts and opinions effectively. Here is a step-by-step guide:

1. Read the book thoroughly: Begin by reading the book from start to finish. Take notes while reading, paying attention to the main arguments, evidence, and the author's writing style. It's essential to have a clear understanding of the book's content. Questions to ask while reading:

• What is the author's main argument that they want to get across?

• What are the smaller arguments the author argues contribute to the main one? Are you persuaded that these more specific reasons support the author's wider thesis? If not, why not? (this is also an excellent time to think about any key terms the author uses or invents to discuss a specific problem or occurrence. How do they improve upon what we already know?)

2. Understand the book's context: Research the author's background, their previous works, and the broader context in which the book was written. Consider the book's genre, its significance within the field, and any relevant historical, cultural, or social aspects that may inform your review.

3. Structure your review: Start by providing a concise summary of the book, highlighting its main themes, arguments, and contributions. Then, organize your review by discussing specific aspects of the book in separate sections, such as the author's methodology, the strength of their arguments, the quality of evidence, the writing style, and the overall impact of the book.

4. Provide evidence and examples: Support your evaluation with specific evidence from the book. Quote relevant passages, cite specific examples, and reference any data or research the author presents. Use these examples to illustrate your points and provide a solid foundation for your analysis.

5. Engage with the text critically: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the book. Consider the author's arguments, the evidence they provide, and their overall effectiveness in conveying their ideas. Identify any gaps or limitations in the book's approach, and analyze how it contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

6. Situate the book within the field: Assess the book's contribution to the broader scholarly conversation. Determine whether the book introduces new insights, challenges existing theories, or offers a fresh perspective on the subject matter. Discuss how the book aligns with or diverges from other works in the field and its potential impact on future research.

7. Develop a clear and coherent argument: Present your analysis in a logical and organized manner. Use clear language and concise sentences to convey your thoughts effectively. Make sure to back up your assertions with evidence and examples from the book.

8. Balance objectivity and subjectivity: While a scholarly book review requires objectivity, it's also acceptable to include your own subjective opinions and reactions. Just make sure to clearly differentiate between the author's work and your personal perspective.

9. Conclude your review: Summarize your main points and provide a final evaluation of the book. Offer a concise recommendation or judgment regarding the book's overall quality, usefulness, and significance.

10. Edit and proofread: Review your work for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Ensure your review is clear, coherent, and well-structured. Consider seeking feedback from peers or colleagues to refine your review further.

Remember, a scholarly book review should be thoughtful, well-reasoned, and objective. It should provide readers with a comprehensive understanding of the book and its contributions to the field while offering your own critical analysis and evaluation.

Suggested Structure for the Review

1. Introduction

a. Begin with a brief introduction that includes the book's title, author, publication information, and any relevant background information about the author or the book's context.

b. Provide a concise overview of the book's main topic or subject matter.

c. State your overall purpose for writing the review and mention the main points you will address. What is at stake here? Why should scholars be interested in this work? Grab the reader’s attention right away, locating the book in established debates and controversies.

2. Summary of the Book

a. Provide a summary of the book's main arguments, ideas, and supporting evidence. Include the major themes and key concepts.

b. Be concise but ensure that you cover the essential aspects of the book. Within the first two paragraphs, it’s important to try to explicitly state the primary argument of the book (e.g., “Smith’s main argument revolves around/centers on/is…”). What is the larger point of this book, and why should readers care?

3. Analysis and Evaluation

a. Analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the book. Consider aspects such as the author's argumentation, evidence, methodology, organization, and writing style. Please strive to be fair and considerate while offering critique. However, you can disagree with the book's claims if you believe they are incorrect, exaggerated, misguided, or for any other reason. On the other hand, you can talk about how much you loved the book and explain what specifically fascinated, persuaded, or revolutionized your perspective about the argument or idea.

b. Assess the book's contribution to the field or discipline. Evaluate whether it adds new insights, challenges existing theories, or provides a unique perspective.

c. Support your analysis with evidence from the book. Quote relevant passages or provide examples to substantiate your points.

4. Discussion and Interpretation

a. Engage in a critical discussion of the book's content. Analyze the implications of the author's arguments and ideas.

b. Consider the book's significance in relation to broader academic debates or the field of study.

c. Offer your own interpretations and insights, presenting your perspective on the book's strengths, weaknesses, and overall value.

5. Conclusion

a. Summarize your main points and findings from the analysis and evaluation.

b. Provide a clear and concise overall assessment of the book.

c. State your final thoughts and opinions on the book, including any recommendations for further reading or research.

6. References

a. Include a list of references for any sources cited or referenced in your review. Follow the Chicago Manual of Style ’s author-date format.

Potential Book Reviewers

We are always looking for new book reviewers interested in various disciplines. If you wish to become a book reviewer, write to us along with your CV. You can send us a few titles that you would like to review or just your areas of interest. Please contact our editors at [email protected] .

Special Issue Proposals

Guest editor guide.

We know that there is a lot to take on when assuming the role of guest editor. We have therefore put together this guide, which leads you through the most important aspects of the role and what you can expect from the process of editing a special issue.

What is a special issue of a journal?

Special issues of a journal are generally centered around a theme. These articles can come from papers/presentations at workshops, symposia, or conferences. The guest editors can also issue a call for papers about a particular topic. Some special issues are festschrifts honoring a certain scholar’s contributions to their field.

In the past, Sign Language Studies has featured special issues on:

- Linguistic ethnography and sign language studies (guest editors: Annelies Kusters and Lynn Hou; vol. 20, no. 4)

- Creative sign language in the Southern hemisphere (guest editors: Rachel Sutton-Spence and Michiko Kaneko ; vol. 20, no. 3)

- Rural sign languages (guest editors: Connie De Vos and Victoria Nyst ; vol. 18, no. 4)

- Language planning and sign language rights (guest editor: Joseph J. Murray; vol. 15, no. 4)

- (This is not an exhaustive list of our special issues—it’s just a sampling.)

What are the responsibilities of guest editors?

As a guest editor, you are assuming the responsibilities of the journal editors. They will be available to give advice but you are responsible for the following:

- coming to an agreement with the SLS editors on a specific deadline to submit the final version of the papers

- gathering the initial submissions

- identifying appropriate peer reviewers and asking if they are available to peer review

- sending out and tracking the submissions for peer review (you may have to nudge some reviewers to meet your deadlines)

- deciding whether or not to accept the submissions as is, with revisions, or whether to reject

- communicating your decisions to the submissions’ authors

- sending out the contributor contracts to the accepted submission authors

- gathering all the signed contributor contracts and forwarding them to GU Press along with each author’s snail-mail address (in order to facilitate sending out the comp copies after the issue is printed) and each contact author’s email address

- submitting a table of contents to GU Press to indicate the articles’ order and to help market your issue

- writing an introduction to the special issue

- submitting the final manuscripts with all of their art, tables, appendixes, etc., to GU Press by the established deadline

- reviewing the typeset proofs (these will also be sent to the article authors)

Before submission

Unless one of SLS ’s editors has directly approached you about guest editing an issue, you will need to submit a proposal. The proposal should include:

- the potential papers and authors with a brief description of each paper (these papers don’t need to be already written, though they might be in progress)

- the timeframe in which the special issue could be produced (include time for paper writing, peer reviewing, and submission of final copy to the journal) if the proposal is accepted

- short biographies of all authors and guest editors

- any special timing, associated events, funding support, partnerships, or other links or relationships that could influence the issue

- any other information that you feel is relevant

A special issue normally contains around five full-length articles, in addition to an editorial written by the guest editors (occasionally the SLS editors might want to include their own editors’ note).

Please submit your proposal to [email protected] .

Disclosure and conflicts of interest

Conflict of interest exists when an author (or the author’s institution), reviewer, or editor has financial or personal relationships that inappropriately influence (bias) their actions.

The special issue may publish submissions from the guest editors but the number should normally not exceed one by each guest editor (except where specifically approved by the SLS editors). The guest editor cannot be involved in decisions about papers that they have written themselves. Peer review of any such submission should be handled independently of the relevant guest editor/coeditor and their research teams.

The peer review process

Confidentiality

The guest editor should protect the confidentiality of all material submitted to the journal and all communications with reviewers. The guest editor must not disclose reviewers’ identities.

Selection of papers and the decision process

You are responsible, along with any other guest editor(s), for making sure that the review process is conducted in an appropriate manner and in line with normal review practices for the journal. You may consult with the SLS editors about the procedure to be followed.

You will make the decision on all manuscripts based on peer review and your own expertise (as well as that of any co-guest editors).

Selection of reviewers

As guest editor, you should select reviewers who have expertise in the field. You also must ask for and review all disclosures of potential conflicts of interest made by reviewers in order to determine whether there is any potential for bias.

Publication process

Once all the peer reviews are finished and you are satisfied with the final accepted articles, they should be submitted with all of their art, tables, videos, contact email addresses, and any other supplementary material to [email protected] . She will review the articles to make sure they are complete and then they will be sent out for copy editing.

Once the copy editor has finished, the articles will be returned to their respective authors for their review. Typically, there is a one- to two-week turnaround. Once the authors are finished, the manuscripts are returned to GUP for clean-up. If time is available, the clean version of the articles is re-sent to the authors for a final check before being sent to typesetting.

After the issue is typeset, proofs of each article are sent to their respective authors and a proof of the entire issue is sent to the guest editor(s). At this point in the process, we are checking for typos and any serious factual errors. Changes such as rewriting paragraphs or moving figures and tables around are not acceptable at this stage (anything that affects the pagination is very costly to change and the authors may be charged for these changes).

The article authors have the prime responsibility for proofreading their typeset articles but you may also review them and submit corrections. Once all the proofs have been returned, the GU Press managing editor will combine all of the changes onto a single marked-up proof and will return that to the typesetter. GU Press will then check all subsequent proofs to make sure the changes have been made correctly.

Final “print-ready” files are then sent to the printer, ERIC (Education Resources Information Center at the U.S. Department of Education), and to electronic library platforms such as Project MUSE and JSTOR. Once the issue is printed, hard copies of the issue will be sent to each of the guest editors and article authors.

SLS (ISSN #0302-1475) is published four times a year: fall, winter, spring, and summer.

Click here for subscription information.

Purchase Digital Content

Click here for information about purchasing digital copies of articles or issues.

The Editors

Erin Wilkinson and Pilar Piñar Editors

SLS Editorial Board

Robert Adam University College London

Glenn Anderson University of Arkansas

Dirksen Bauman Gallaudet University

Karen Emmorey San Diego State University

Jordan Fenlon Independent Researcher

Maribel Gárate Gallaudet University

Brian Greenwald Gallaudet University

Joseph Hill National Technical Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology

Julie A. Hochgesang Gallaudet University

Lynn Hou University of California, Santa Barbara

Tom Humphries University of California, San Diego

Terry Janzen University of Manitoba

Arlene B. Kelly Gallaudet University

Christopher Krentz University of Virginia

Gaurav Mathur Gallaudet University

Kazumi Matsuoka Keio University