83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best salem witch trials topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ good research topics about salem witch trials, 👍 simple & easy salem witch trials essay titles, ❓ salem witch trials research questions.

- Why Abigail Williams Is Blamed for the Salem Witch Trials This essay is going to analyze the reasons why Abigail Williams is to be blamed for the Salem witch trials and dreadful hangings. The narcissism and egocentrism of Abigail lead her to accuse others.

- Salem Witch Trials and the Enlightenment Cultural Shift However, the further change in the attitude to the processes and their reconsideration indicated the strong impact of Enlightenment ideas and their spread over the region.

- The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear The outbreak began with the sudden and rather unusual illness of the daughter and niece of the local Reverend Samuel Parris.

- Salem Witchcraft Hysteria: Crime Against Women In the “Was the Salem Witchcraft Hysteria a Product of Women’s Search for Power?” Kyle Koehler and Laurie Winn Carlson present the “pro” and “cons” arguments for this claim.

- Witch Trials. Salem Possessed by Boyer and Nissenbaum Let us recall that the greater part of the complaints during the trials came from the Salem Village and the greater part of the accused came from Salem Town and the pattern of economic and […]

- Salem Witch Trials: Differeenses From in Europe Witch trials in the new colonies of America were not a unique phenomenon in world history but the events of 1692 in Salem Massachusetts differed in scope and circumstances from in Europe, the origin of […]

- The Salem Witch Trials in American History Blame ranges from the devil initially to puritan ministers encouraging the witch mania to bring support for the Church, and to the ideology of Puritanism itself, a strong belief that everything strange is the work […]

- The Grave Injustices of the Salem Witchcraft Trials These thoughts enforced the belief in the existence of witchcraft in New England. The people of New England were in the middle of a war with the Indians.

- Witchcraft Accusations, Trials, and Hysteria in Border Regions and Rural Areas in Western Europe To a great extent, this phenomenon can be attributed to the following factors: 1) official recognition of witchcraft and the activities of religious zealots who inspired the persecution of many people; 2) the stereotypes and […]

- Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials As much as these trials can be referred to as the Salem trials, initial hearings were conducted in a number of towns in 1692.

- Through Women’s Eyes: Salem Witch Trial The accusers took advantage of the ignorance of the people to make them believe that it was indeed supernatural causes which made the town of Salem suffer.

- Salem Witch Trials Causes The writers explain that the problem began in the year 1691 and was marked by the behaviour of some girls in the same village who were involved in fortune telling.

- Salem Witch Trials and Civil Rights Movement

- The Infamous Salem Witch Trials

- Behavior, Expectation, and Witch-Hunting During the Salem Witch Trials

- Origins, Consequences, and Legacy of the Salem Witch Trials

- The History, Causes, and Effects of the Salem Witch Trials

- Reasons for Salem Witch Trials

- Salem Witch Trials and Innocent People

- Witchcraft and the Salem Witch Trials

- Discrimination and the Salem Witch Trials

- The Facts and Fictions of the Salem Witch Trials

- The Salem Witch Trials of Colonial History

- Religion, Social Norms, and the Salem Witch Trials

- The Psychic Crisis Theory of the Salem Witch Trials

- Salem Witch Trials and Religious Superstition

- Historical References From the Salem Witch Trials

- Mass Hysteria During the Salem Witch Trials

- The Salem Witch Trials on Society and Religious Belief

- Witchcraft and the Puritan Lifestyle in Salem During the Late 1600s in the Salem Witch Trials, a Book by Lori Lee Wilson

- Salem Witch Trials and McCarthyism in America

- Factors That Influence the Salem Witch Trials

- Salem Witch Trials and the Great Tragedy

- Elizabeth Proctor and the Salem Witch Trials

- Hygiene During the Salem Witch Trials

- Cause, Effect, and Importance of the Salem Witch Trials

- Persecution and the Salem Witch Trials

- Individuals Who Played Different Roles in the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts

- Salem Witch Trials and Modern Satanic Trials

- McCarthyism and the Salem Witch Trials

- Puritanism and Salem Witch Trials

- Salem Witch Trials and Convulsive Ergotism

- The Events and History of Salem Witch Trials

- Anthropological and Sociological Effects of Puritanism and the 1692 Salem Witch Trials

- Primary Sources for the Salem Witch Trials

- The Salem Witch Trials and the Women Victims

- Puritan Literature and the Salem Witch Trials

- Belonging: Salem Witch Trials and Society

- The Factors That Influenced Salem Witch Trials

- Horror During the Salem Witch Trials

- Crucible: Salem Witch Trials and American Society

- Salem Witch Trials and Forbidden Knowledge Witch

- What Social Problem Did the Salem Witch Trials and Executions Solve?

- Why and How Did the Salem Witch Trials Happen?

- What Effect Did the Salem Witch Trials Have on American Literature?

- Was Abigail Williams Solely Responsible for the Salem Witch Trials?

- What Do the Salem Witch Trials Reveal About Gender and Power in the 17th Century in the US?

- How Did the Puritans Affect the Trials of the Salem Witch?

- What Was Ann Putnum’s Point of View About the Salem Witch Trials?

- Were Salem Witch Trials a Peculiar Aberrant Moment in an Age of Superstition or Were They Something Else?

- What Part Did Gender Roles Play During the Salem Witch Trials?

- How Did the Salem Witch Trials Impact Modern Culture?

- What Impact Did the Puritan’s Religious and Social Culture Have on the Proceedings of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Were the Salem Witch Trials Spurred by Food Poisoning?

- What Were the Causes and Effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- How Do the Salem Witch Trials Relate to the Changes Occurring During the Late 17th Century in Colonial British America?

- What Caused the Salem Witch Trials Hysteria?

- How Did the Salem Witch Trials Go Down?

- What Happened During the Salem Witch Trials?

- How Were McCarthyism and the Salem Witch Trials Related?

- What Was the Significance of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Is the Movie ‘the Crucible’ Historically Accurate to the Salem Witch Trials of 1693?

- How Were Elizabeth Proctor and Sarah Cloyce Arrested During the Salem Witch Trials?

- What Were the Underlying Causes of the Persecution of People During the Salem Witch Trials?

- Do the Salem Witch Trials Which Occurred in 1662 and 1663 Have an Explanation Other Than Superstition and Religion?

- How the Salem Witch Trials Affected How We View Witches Today?

- What Was the Best Way to Avoid Trial and Execution for Witchcraft During the Salem Witch Trials?

- Are Witch Trials Legitimate Today? Was It Legal in the Period of the Salem Witch Trials?

- What Were the Events That Led to the Salem Witch Trials?

- Had the Puritan Religion Itself Been the Real Culprit in the Salem Witch Trials?

- How Does the Author Laurie Winn Carlson Speak About the Salem Witch Trials?

- What Did the Leaders of Salem Have to Gain Through the Exposure of So-Called Witches?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 27). 83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/salem-witch-trials-essay-topics/

"83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 27 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/salem-witch-trials-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 27 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/salem-witch-trials-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/salem-witch-trials-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "83 Salem Witch Trials Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/salem-witch-trials-essay-topics/.

- Belief Questions

- Christianity Topics

- Crusades Research Topics

- God Paper Topics

- Gender Inequality Research Topics

- Holy Spirit Titles

- Religious Conflict Topics

- US History Topics

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Salem Witch Trials

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 29, 2023 | Original: November 4, 2011

The infamous Salem witch trials began during the spring of 1692, after a group of young girls in Salem Village, Massachusetts, claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of witchcraft. As a wave of hysteria spread throughout colonial Massachusetts, a special court convened in Salem to hear the cases; the first convicted witch, Bridget Bishop, was hanged that June. Eighteen others followed Bishop to Salem’s Gallows Hill, while some 150 more men, women and children were accused over the next several months.

By September 1692, the hysteria had begun to abate and public opinion turned against the trials. Though the Massachusetts General Court later annulled guilty verdicts against accused witches and granted indemnities to their families, bitterness lingered in the community, and the painful legacy of the Salem witch trials would endure for centuries.

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?: Context & Origins

Belief in the supernatural—and specifically in the devil’s practice of giving certain humans (witches) the power to harm others in return for their loyalty—had emerged in Europe as early as the 14th century, and was widespread in colonial New England . In addition, the harsh realities of life in the rural Puritan community of Salem Village (present-day Danvers, Massachusetts ) at the time included the after-effects of a British war with France in the American colonies in 1689, a recent smallpox epidemic, fears of attacks from neighboring Native American tribes and a longstanding rivalry with the more affluent community of Salem Town (present-day Salem).

Amid these simmering tensions, the Salem witch trials would be fueled by residents’ suspicions of and resentment toward their neighbors, as well as their fear of outsiders.

Did you know? In an effort to explain by scientific means the strange afflictions suffered by those "bewitched" Salem residents in 1692, a study published in Science magazine in 1976 cited the fungus ergot (found in rye, wheat and other cereals), which toxicologists say can cause symptoms such as delusions, vomiting and muscle spasms.

In January 1692, 9-year-old Elizabeth (Betty) Parris and 11-year-old Abigail Williams (the daughter and niece of Samuel Parris, minister of Salem Village) began having fits, including violent contortions and uncontrollable outbursts of screaming. After a local doctor, William Griggs, diagnosed bewitchment, other young girls in the community began to exhibit similar symptoms, including Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, Elizabeth Hubbard, Mary Walcott and Mary Warren.

In late February, arrest warrants were issued for the Parris’ Caribbean slave, Tituba, along with two other women—the homeless beggar Sarah Good and the poor, elderly Sarah Osborn—whom the girls accused of bewitching them.

Salem Witch Trial Victims: How the Hysteria Spread

The three accused witches were brought before the magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne and questioned, even as their accusers appeared in the courtroom in a grand display of spasms, contortions, screaming and writhing. Though Good and Osborn denied their guilt, Tituba confessed. Likely seeking to save herself from certain conviction by acting as an informer, she claimed there were other witches acting alongside her in service of the devil against the Puritans.

As hysteria spread through the community and beyond into the rest of Massachusetts, a number of others were accused, including Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse—both regarded as upstanding members of church and community—and the four-year-old daughter of Sarah Good.

Like Tituba, several accused “witches” confessed and named still others, and the trials soon began to overwhelm the local justice system. In May 1692, the newly appointed governor of Massachusetts, William Phips, ordered the establishment of a special Court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) on witchcraft cases for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties.

Presided over by judges including Hathorne, Samuel Sewall and William Stoughton, the court handed down its first conviction, against Bridget Bishop, on June 2; she was hanged eight days later on what would become known as Gallows Hill in Salem Town. Five more people were hanged that July; five in August and eight more in September. In addition, seven other accused witches died in jail, while the elderly Giles Corey (Martha’s husband) was pressed to death by stones after he refused to enter a plea at his arraignment.

Salem Witch Trials: Conclusion and Legacy

Though the respected minister Cotton Mather had warned of the dubious value of spectral evidence (or testimony about dreams and visions), his concerns went largely unheeded during the Salem witch trials. Increase Mather, president of Harvard College (and Cotton’s father) later joined his son in urging that the standards of evidence for witchcraft must be equal to those for any other crime, concluding that “It would better that ten suspected witches may escape than one innocent person be condemned.”

Amid waning public support for the trials, Governor Phips dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer in October and mandated that its successor disregard spectral evidence. Trials continued with dwindling intensity until early 1693, and by that May Phips had pardoned and released all those in prison on witchcraft charges.

In January 1697, the Massachusetts General Court declared a day of fasting for the tragedy of the Salem witch trials; the court later deemed the trials unlawful, and the leading justice Samuel Sewall publicly apologized for his role in the process. The damage to the community lingered, however, even after Massachusetts Colony passed legislation restoring the good names of the condemned and providing financial restitution to their heirs in 1711.

Indeed, the vivid and painful legacy of the Salem witch trials endured well into the 20th century, when Arthur Miller dramatized the events of 1692 in his play “The Crucible” (1953), using them as an allegory for the anti-Communist “witch hunts” led by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. A memorial to the victims of the Salem witch trials was dedicated on August 5, 1992 by author and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel.

HISTORY Vault: Salem Witch Trials

Experts dissect the facts—and the enduring mysteries—surrounding the courtroom trials of suspected witches in Salem Village, Massachusetts in 1692.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Salem Witch Trials — the Witchcraft Hysteria of 1692

February 1692–May 1693

The Salem Witch Trials are a series of well-known investigations, court proceedings, and prosecutions that took place in Salem, Massachusetts over the course of 1692 and 1693.

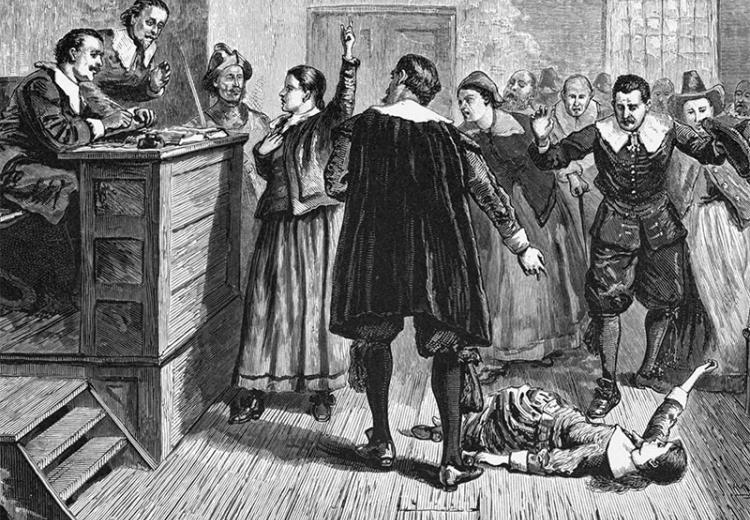

This illustration by Howard Pyle depicts one of the accusers pointing at the accused and saying, “There is a flock of yellow birds around her head.” It is an example of the spectral evidence that was permitted at the trials. Image Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections .

Salem Witch Trials Summary

The Salem Witch Trials took place in colonial Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693 when people living in and around the town of Salem, Massachusetts were accused of practicing witchcraft or dealing with the Devil. The accusations were initially made by two young girls in the early part of the year.

By May, William Phips had been named Governor of Massachusetts and a new charter had been implemented. Initially, Phips responded to the accusations by setting up a special court — the Court of Oyer and Terminer — to hear the cases and to determine the fate of the accused.

Unfortunately, the court was controversial because they allowed “spectral” evidence — visions of ghosts, demons, and the Devil — to be entered into the proceedings. It seemed to fuel the hysteria, which was likely elevated by King William’s War, which was going on in New England at the same time.

By the fall, 19 men and women had been convicted and hanged, and another was pressed to death . Another man died from having heavy stones placed on him. Somewhere between 150 and 200 were in prison or had spent time in prison.

Governor Phips ended the special court in October after accusations were made against well-respected members of the community. In January 1693, the trials resumed, but under the Supreme Court of Judicature. Spectral evidence was not allowed, and most of the accused were found innocent of the witchcraft charges and released.

A handful of the people accused of witchcraft were convicted, but Governor Phips intervened in May 1693 and agreed to release them as long as they paid a fine. By the time the proceedings ended, it was the largest outbreak of witchcraft in Colonial America .

Salem Witch Trials Facts

Facts about the accusers in the salem witch trials.

Two young girls, Elizabeth Paris and Abigail Williams started to act in a strange manner, which included making strange noises and hiding from their parents and other adults.

Elizabeth Paris, known as Betty, was 9 years old. Her father was the Reverend Samuel Paris.

Abigail Williams was 11 years old. Reverend Paris was her uncle.

More young girls in Salem Village started to show similar symptoms, including 12-year-old Anne Putnam and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard.

Facts About the Accused in the Salem Witch Trials

The first people accused of witchcraft were Tituba, an enslaved woman, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne.

Dorothy Good was the youngest person to be accused of witchcraft. She was 4 years old.

Facts About the Role and Testimony of Tituba in the Salem Witch Trials

Tituba is believed to be an enslaved woman from Central America, possibly from Barbados.

She lived in the home of Reverend Paris and had been taken to Massachusetts by Paris in 1680.

Tituba confessed to using witchcraft.

She testified that four women, including Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good, along with a man, had told her to hurt the children.

Her testimony convinced the people of Salem Village that witchcraft was rampant in the town.

Facts About People Convicted and Executed During the Salem Witch Trials

The first person to be executed was Bridget Bishop.

Over the course of the Salem Witch Trials, 19 people were hanged at Proctor’s Ledge, near Gallows Hill.

Another one of the accused, Giles Corey, refused to enter a plea before the court and was ordered to be pressed to death. He was laid down on the ground and had heavy boards placed on top of him. Then heavy rocks were set on the boards until he was crushed by the weight.

The charges against all victims of the Salem Witch Trials were eventually cleared.

The Special Court

The Court of Oyer and Terminer was the special court ordered to oversee the trials, as ordered by Governor William Phips.

Salem Witch Trials Significance

The Salem Witch Trials were important because they showed how quickly accusations and hysteria could spread through Colonial America. At the time, the Witch Trials also threatened the authority and stability of the new charter and government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, while King William’s War raged across New England and Acadia .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH — Notes and Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study the Salem Witch Trials, King Willilam’s War, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Definition

The Salem Witch Trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions that occurred in colonial Massachusetts between 1692 and 1693. The trials were a dark chapter in American history, characterized by mass hysteria and accusations of witchcraft. Numerous individuals, predominantly women, were accused of practicing witchcraft, leading to the execution of 20 people — 13 women and 7 men. The trials were fueled by social, religious, and political factors, partially driven by King William’s War, resulting in tragic consequences for the victims and their families.

Salem Witch Trials Video for APUSH Notes

This video from the Daily Bellringer provides a detailed look at the Salem Witch Trials.

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Terms and Definitions

William Phips — William Phips was the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a significant role in bringing an end to the trials by dissolving the Court of Oyer and Terminer, which was responsible for the majority of the convictions. Phips was concerned about the growing public skepticism and criticism surrounding the trials, prompting him to take decisive action and promote a more rational approach to handling alleged witches. He was also worried about the public perception the trials had, during a time of war.

Court of Oyer and Terminer — The Court of Oyer and Terminer was a special court established in 1692 to handle the cases of alleged witches in Salem and surrounding areas. The court was led by several judges, including William Stoughton, and it operated under a unique legal process that allowed spectral evidence, or testimonies of dreams and visions, to be admitted as valid evidence. This, along with other factors, contributed to a biased and unjust environment during the trials.

William Stoughton — William Stoughton was a prominent judge and the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He presided over the Court of Oyer and Terminer during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a pivotal role in the harsh convictions and sentencing of numerous accused individuals. His unwavering support for spectral evidence and his lack of leniency exacerbated the severity of the trials’ outcomes. After Phips dismissed the cases, Stoughton worked to have him removed as Governor.

Samuel Paris — Reverend Samuel Paris was the minister of Salem Village and one of the central figures in the initial events that sparked the witch trials. He was the father of Elizabeth Paris and the uncle of Abigail Williams, two young girls who experienced mysterious fits and claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft. His role as a religious authority and his support for the accusations fueled the hysteria, contributing to the escalation of the trials.

Elizabeth Paris — Elizabeth Paris was the nine-year-old daughter of Samuel Paris and one of the first accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. With her cousin Abigail Williams, she exhibited peculiar behaviors, including seizures and strange utterances, which were attributed to witchcraft. Their accusations against various individuals, especially Tituba, were instrumental in initiating the investigations and subsequent arrests.

Abigail Williams — Abigail Williams, the eleven-year-old cousin of Elizabeth Paris, was another crucial accuser during the Salem Witch Trials. Like her cousin, she displayed symptoms of bewitchment and was among the first to accuse others, leading to a chain reaction of allegations.

Anne Putnam — Anne Putnam was a teenage girl from Salem Village who actively participated in the trials as an accuser. She made numerous accusations against various individuals, contributing to the mounting hysteria. Her motivations for involvement remain a topic of historical debate, with some suggesting that personal grievances and religious fervor influenced her actions.

Tituba — Tituba was an enslaved woman from the Caribbean who worked in the household of Reverend Samuel Paris. She became one of the first individuals accused of practicing witchcraft after Elizabeth and Abigail accused her of bewitching them. Tituba’s origin and cultural differences contributed to her status as an outsider in Salem, making her an easy target for accusations. Under pressure, she confessed to being a witch and provided testimonies that increased the intensity of the trials.

Bridget Bishop — Bridget Bishop was the first person to be tried and executed during the Salem Witch Trials. She was known for her unconventional lifestyle and had been accused of witchcraft once before.

John Proctor — John Proctor was a respected farmer in Salem Village and one of the central figures in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible,” which was based on the events of the witch trials. Proctor was accused of witchcraft after he spoke out against the proceedings, expressing skepticism about the legitimacy of the trials. His refusal to falsely confess and his unwavering integrity ultimately led to his tragic execution.

Giles Corey — Giles Corey was an elderly farmer who became entangled in the witch trials when his wife, Martha Corey, was accused of witchcraft. In a notable act of protest against the unjust proceedings, Corey refused to enter a plea in court, leading to a brutal form of punishment known as pressing. Corey died during the punishment.

King William’s War — King William’s War was a conflict between England and France that occurred from 1689 to 1697, overlapping with the time of the Salem Witch Trials. The war was part of a larger conflict known as the Nine Years’ War or the War of the Grand Alliance. Its impact on the region, including heightened tensions and security concerns, likely contributed to the climate of fear and paranoia in Salem, potentially influencing the outbreak of the witch trials.

Salem Witch Trials — Primary and Secondary Sources

- The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692 by Thomas Hutchinson , William Frederick Poole, and Richard Frothingham

- The Wonders of the Invisible World : Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England by Cotton Mather

- Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men, Witchcrafts, Infallible Proofs of Guilt in Such as are Accused with the Crime by Increase Mather

- Written by Randal Rust

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

Looking into the underlying causes of the Salem Witch Trials in the 17th century.

In February 1692, the Massachusetts Bay Colony town of Salem Village found itself at the center of a notorious case of mass hysteria: eight young women accused their neighbors of witchcraft. Trials ensued and, when the episode concluded in May 1693, fourteen women, five men, and two dogs had been executed for their supposed supernatural crimes.

The Salem witch trials occupy a unique place in our collective history. The mystery around the hysteria and miscarriage of justice continue to inspire new critiques, most recently with the recent release of The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Pulitzer Prize-winning Stacy Schiff.

But what caused the mass hysteria, false accusations, and lapses in due process? Scholars have attempted to answer these questions with a variety of economic and physiological theories.

The economic theories of the Salem events tend to be two-fold: the first attributes the witchcraft trials to an economic downturn caused by a “little ice age” that lasted from 1550-1800; the second cites socioeconomic issues in Salem itself.

Emily Oster posits that the “little ice age” caused economic deterioration and food shortages that led to anti-witch fervor in communities in both the United States and Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Temperatures began to drop at the beginning of the fourteenth century, with the coldest periods occurring from 1680 to 1730. The economic hardships and slowdown of population growth could have caused widespread scapegoating which, during this period, manifested itself as persecution of so-called witches, due to the widely accepted belief that “witches existed, were capable of causing physical harm to others and could control natural forces.”

Salem Village, where the witchcraft accusations began, was an agrarian, poorer counterpart to the neighboring Salem Town, which was populated by wealthy merchants. According to the oft-cited book Salem Possessed by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Village was being torn apart by two opposing groups–largely agrarian townsfolk to the west and more business-minded villagers to the east, closer to the Town. “What was going on was not simply a personal quarrel, an economic dispute, or even a struggle for power, but a mortal conflict involving the very nature of the community itself. The fundamental issue was not who was to control the Village, but what its essential character was to be.” In a retrospective look at their book for a 2008 William and Mary Quarterly Forum , Boyer and Nissenbaum explain that as tensions between the two groups unfolded, “they followed deeply etched factional fault lines that, in turn, were influenced by anxieties and by differing levels of engagement with and access to the political and commercial opportunities unfolding in Salem Town.” As a result of increasing hostility, western villagers accused eastern neighbors of witchcraft.

But some critics including Benjamin C. Ray have called Boyer and Nissenbaum’s socio-economic theory into question . For one thing –the map they were using has been called into question. He writes: “A review of the court records shows that the Boyer and Nissenbaum map is, in fact, highly interpretive and considerably incomplete.” Ray goes on:

Contrary to Boyer and Nissenbaum’s conclusions in Salem Possessed, geo graphic analysis of the accusations in the village shows there was no significant villagewide east-west division between accusers and accused in 1692. Nor was there an east-west divide between households of different economic status.

On the other hand, the physiological theories for the mass hysteria and witchcraft accusations include both fungus poisoning and undiagnosed encephalitis.

Linnda Caporael argues that the girls suffered from convulsive ergotism, a condition caused by ergot, a type of fungus, found in rye and other grains. It produces hallucinatory, LSD-like effects in the afflicted and can cause victims to suffer from vertigo, crawling sensations on the skin, extremity tingling, headaches, hallucinations, and seizure-like muscle contractions. Rye was the most prevalent grain grown in the Massachusetts area at the time, and the damp climate and long storage period could have led to an ergot infestation of the grains.

One of the more controversial theories states that the girls suffered from an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica , an inflammation of the brain spread by insects and birds. Symptoms include fever, headaches, lethargy, double vision, abnormal eye movements, neck rigidity, behavioral changes, and tremors. In her 1999 book, A Fever in Salem , Laurie Winn Carlson argues that in the winter of 1691 and spring of 1692, some of the accusers exhibited these symptoms, and that a doctor had been called in to treat the girls. He couldn’t find an underlying physical cause, and therefore concluded that they suffered from possession by witchcraft, a common diagnoses of unseen conditions at the time.

The controversies surrounding the accusations, trials, and executions in Salem, 1692, continue to fascinate historians and we continue to ask why, in a society that should have known better, did this happen? Economic and physiological causes aside, the Salem witchcraft trials continue to act as a parable of caution against extremism in judicial processes.

Editor’s note: This post was edited to clarify that Salem Village was where the accusations began, not where the trials took place.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- The Long History of Live Animal Export

- Haunted Soldiers in Mesopotamia

- The Post Office and Privacy

The British Empire’s Bid to Stamp Out “Chinese Slavery”

Recent posts.

- Wasp Viruses, Athleisure, and Humans in Flight

- Debt-Trap Diplomacy

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Understanding the Salem Witch Trials

Engraving of a witchcraft trial at Salem Village. The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott.

Wikimedia Commons

Salem, Massachusetts in 1691 was the home of a Puritan community with a strict moral code. In addition to the difficulties of farming in a harsh climate with rough terrain, Salem faced economic and political unrest. In this community, a group of girls accused an Indian slave named Tituba of witchcraft. Tituba confessed under pressure from court officials, and her confession ignited a hunt for witches that left 19 men and women hanged, one man pressed to death, and over 150 more people in prison awaiting a trial. In this lesson, students will explore the characteristics of the Puritan community in Salem, learn about the Salem Witchcraft Trials, and try to understand how and why this event occurred.

Guiding Questions

What was life like in Puritan New England?

What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

To what extent do the historic records show that the accused were innocent until proven guilty?

Learning Objectives

Describe cultural practices of the majority in Puritan New England.

Create a timeline of the events of the Salem Witch Trials.

Analyze multiple interpretations of the Salem Witch Trials.

Construct a position on whether the trials were justified.

Lesson Plan Details

Salem, Massachusetts in the late 1600s faced a number of serious challenges to a peaceful social fabric. Salem was divided into a prosperous town and a farming village. The villagers, in turn, were split into factions that fiercely debated whether to seek ecclesiastical and political independence from the town. In 1689 the villagers won the right to establish their own church and chose the Reverend Samuel Parris, a former merchant, as their minister. His rigid ways and seemingly boundless demands for compensation increased the already present friction. Many villagers vowed to drive Parris out, and they stopped contributing to his salary in October 1691.

These local concerns only compounded the severe social stresses that had already been affecting New England for two decades. A 1675 conflict with the Indians known as King Philip's War had resulted in more deaths relative to the size of the population than any other war in American history. A decade later, in 1685, King James II's government revoked the Massachusetts charter. A new royally-appointed governor, Sir Edmund Andros, sought to unite New England, New York, and New Jersey into a single Dominion of New England. He tried to abolish elected colonial assemblies, restrict town meetings, and impose direct control over militia appointments, and permitted the first public celebration of Christmas in Massachusetts, a celebration of which Puritans strongly disapproved. After William III replaced James II as King of England in 1689, Andros's government was overthrown, but Massachusetts was required to eliminate religious qualifications for voting and to extend religious toleration to sects such as the Quakers. The late seventeenth century also saw a increase in the number of black slaves in New England, which further unsettled the existing social order.

In February 1692, Betty Parris, Reverend Parris's daughter, as well as her friends Abigail Williams and Ann Putnam, became ill with symptoms that doctors could not diagnose, including fits and delirium. Dr. Griggs, who attended to the "afflicted" girls, suggested that they might be bewitched. Mercy Lewis, Mary Walcott, and Mary Warren later claimed affliction as well.

Prodded by Parris and others, the girls named their tormentors: Sarah Good, a poor woman; Sarah Osbourn, an elderly woman; and Tituba, a slave who had told them stories involving Vudou beliefs. The women were tried for witchcraft - Good and Osbourn claimed innocence, and Tituba confessed. Tituba's detailed confession included a claim that there were several undiscovered witches who wanted to destroy the community. This caused a witch-hunting rampage: 19 men and women were hanged, one man was pressed to death, and over 150 more people were imprisoned, awaiting trial.

On September 22, 1692, the last eight alleged witches were hanged. On October 8, 1692, Governor Phipps ordered that spectral evidence (when someone claimed to witness a person's spirit in a separate location from that same person's physical body) could no longer be admitted in witchcraft trials. On October 29, 1692 Phipps prohibited further arrests and released many accused witches. The remaining alleged witches were pardoned by May 1693. The hangings of witches in 1692 were the last such hangings in America.

For more information, see the following EDSITEment-reviewed websites:

- Digital History: The Salem Witch Scare

- Tituba Biography

NCSS. D1.1.6-8. Explain how a question represents key ideas in the field.

NCSS.D2.His.1.6-8. Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.6-8. Classify series of historical events and developments as examples of change and/or continuity.

NCSS.D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.

NCSS.D2.His.4.6-8. Analyze multiple factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.5.6-8. Explain how and why perspectives of people have changed over time.

- Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and other useful websites. Download and print out documents you will use and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing.

- Students can access the primary source materials and some of the activity materials via the EDSITEment LaunchPad .

- Familiarize yourself with the Salem Witch Trials. For an overview, consult Digital History . For more detailed information, consult Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive .

- If you plan to have students create pictures, or if you want to use larger sized paper for your students' timelines, be sure to have those materials handy.

- Though each reading activity provides questions for discussion for the readings, teachers may wish to spend a few minutes with students asking introductory questions to help distill what they have read.

Activity 1. Life in Puritan New England

Separate the class into four groups, and assign each group one section of the EDSITEment Study Activity under the label Understanding Puritan New England . Offer them the following instructions, and suggest that they distribute the reading evenly and return to discuss the questions after 10–15 minutes of reading. Instructors might also consider assigning this reading the night before as homework.

Instructions for students: Just as the society around us shapes the way we think and act, so did it shape the people of Salem, Massachusetts in the 1600s. Look at the websites listed below, and, on a separate sheet of paper, answer the questions about life in Puritan New England. Note that many of the websites contain interactive images. Click on the images to open them, and mouse-over the image to discover more about it.

The Puritans

The Puritan Idea of the Covenant

- New Groups: A Great Migration

- Working: "To 1 day work at my house"

- Beliefs: A City upon a Hill

- What values that we now consider 'American' were contributed by the Puritans?

- In the 1920s, how did people remember the Puritans? Define the word 'caricature' and explain how it relates to the Puritans.

- To what extent did Puritans condemn alcohol consumption, artistic beauty, and poetry?

- What did the Puritans believe was the primary purpose of government?

- What did the Puritans think about the separation of church and state?

- What is a 'separatist'? Were the Puritans 'separatists'? If not, describe their philosophy regarding the Church of England.

- What is a 'covenant'? Explain the function of 'covenants' in the way the Puritans saw the world.

- Did Puritans believe in tightly knit communities and families, or did they value families that were dispersed?

- Describe some reasons why Puritans came to America from Europe.

- What were some of the strategies New England colonists used to deal with the labor shortage?

- Describe some of the religious beliefs of the Puritans.

- Gender Roles: Beliefs and Gender Roles

- Education: Print and Protestantism

- Customs: Possessions Reveal Social Standing

- Getting Things: Importing Status

- Child Life: Fleeting Mortality

- Look up the word 'Patriarchal' in the dictionary. Define what it means, in your own words.

- What were some of the responsibilities of men in the 1700s in Colonial New England? What were some of the responsibilities of women?

- Explain how the story of Adam and Eve was used to perpetuate prevailing ideas about men and women.

- Were schools important in New England? Did people know how to read?

- Were there as many schools in other parts of America as there were in New England?

- Did wealthy people tend to spend a lot of money? What are some of the things you think they would buy?

- What does 'conspicuous consumption' mean?

- Why did so many children die at young ages in colonial New England?

Group Three

- The Land 1680–1720

- Agriculture: Agriculture and Community

- Public Space: The Meeting House

- According to your reading, what did most Europeans think of the North American Landscape?

- What were some early colonial industries?

- What was the center of public and religious life in New England?

- Describe the common field system.

- What were some results of European fences, mills, grass, and livestock being brought to New England?

- Explain how a mill worked.

- What were the criteria that a committee would use to "seat" the meetinghouse?

- Who was allowed to vote? What did they vote on?

Ask students to explore the EDSITEment-reviewed websites using the Study Activity and questions as guides. Once they have answered all of the questions, ask students to prepare a summary of what they learned to present to the class. Have everyone contribute to the overall discussion about Puritan values (the same question begins each list), and then have students present their information to the class. This should be no more than a few sentences highlighting the key concepts of the aspect of Puritan life that they researched.

Activity 2. What is a Puritan? Case Studies

Ask students to access the following websites and answer the questions listed below. This can be done individually or with partners, and can also be given as a homework assignment. Ask students to read slowly and carefully, looking up words they do not understand and writing them down in their notebook.

John Dane's Narrative

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6214

Read the first five paragraphs of John Dane's Narrative, until you reach the following passage: "Then said my mother, " go where you will, God he will find you out ." This word, the point of it, stuck in my breast; and afterwards God struck it home to its head."

- What does John Dane's piece about morality tell you about Puritan life?

- Define 'Providence' and explain John Dane's beliefs about Providence.

- In the third paragraph of John Dane's narrative, he relates a story about his upbringing. In a paragraph, explain your reaction to his story. How is this different or similar to your own interactions with your parents?

- Choose one paragraph in John Dane's narrative and summarize it in your own words.

Finally, write the following names on slips of paper, and have students draw them from a hat. A convenient PDF with all the names is available for you to print out.

Bridget Bishop; Rev. George Burroughs; Giles Cory; Mary Easty; Sarah Good; Rebecca Nurse; John Proctor; Ann Pudeator; Samuel Wardwell; Sarah Osbourne; William Stoughton; John Hathorne; Samuel Sewall; Francis Dane; Cotton Mather; Sarah Churchill; Elizabeth Hubbard; Mercy Lewis; Elizabeth Parris; Ann Putnam, Jr.; Mary Warren; Mary Wallcott; Abigail Williams; Tituba; Philip English; George Jacobs, Sr., Susannah Martin; Sir William Phips; Samuel Parris.

Ask students to do the following as a homework assignment:

Find your assigned person on the website ' Important Persons in the Salem Court Records ' and write five sentences about him or her answering some of these questions, or similar questions that you come up with on your own:

- How old was the person?

- What was the person's occupation?

- What do we know about the person's family?

- Why do people think this person was accused of witchcraft and/or accused others of witchcraft?

- What is most remembered in about this person in current popular culture, if anything?

- Was this person wealthy or poor?

- Where did this person live?

Activity 3. The Salem Witch Trials

Introduce the trials by asking students:

- What do you think of when you hear the word witch?

If time allows, have students read Words About the Word 'Witch' , available via the EDSITEment-reviewed Digital History website. Otherwise, you might use the website to guide your students' discussion of the term.

As a way to draw together the earlier work on Puritan beliefs and the more specific instance of the Salem Witch Trials, introduce to students the description of Witchcraft available at the EDSITEment-reviewed website History Matters. You might ask students questions like: Who was the head of a Puritan household? What was thought of women who stood out? What cues suggested signs of witchcraft? How do these cues fit within the Puritan worldview that you researched earlier?

At this point, students should begin to reconstruct the history of "What Happened in Salem?" They should begin with their individual person that they researched (see Activity 2). Make sure students follow their individual's role, no matter how small or large, as best they can throughout the process. In combination with this Chronology via the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive , have students separate into groups of four to create a timeline of the Salem Witch Trials. Events on the timeline should each have one sentence attached to them, to assure that students read information about the events, rather than just finding them on the Chronology. The students can illustrate their timelines if there is time for them to do so.

If some groups of students finish earlier than others, ask these students to access this petition for bail from accused witches . Ask students to click on the document and to try to read it. What was it like reading this kind of document? What was the document about? What were some of the reasons that the accused witches cite for why they should be allowed to leave the prison? You might consider recommending both the NARA Primary Document Analysis Worksheet (PDF) and How to Read Old Documents (from American Centuries) to help students figure out the petition.

As students are completing the timeline or reading the primary source document, post signs on your walls - on one side of the classroom, post the words "I agree" and on the other side, post the words "I don't agree". Read a series of controversial statements, listed below, and have students stand somewhere between the "I agree" and "I disagree". They don't have to agree or disagree, they can stand in the middle, or closer to one side than the other, wherever on the spectrum they fit. After each statement is read and students are standing in their spots based on levels of agreement, conduct a conversation from those places, so students can physically see where they are. Students may change physical positions if they change their minds based on discussion. If students move, they should be asked what convinced them to change their mind.

Feel free to add to or alter this list of statements:

- There is nothing about the Puritan way of life that I wish was a part of my life.

- The law is always right.

- Nothing like the Salem Witch Trials happens nowadays.

- People who are accused of crimes are usually bad people.

- The 'afflicted' girls who made the witchcraft accusations were bad people.

- You should never confess to something of which you are not guilty.

- It was just a coincidence that most of the alleged witches were female.

- There is a clear, easy explanation for why the Salem Witch Trials happened.

- The trials happened because of the 'afflicted girls', and not because of other, larger social forces.

- It is silly to believe in witches.

Some of these questions might be best asked of the historical people the students have been tracking since Activity 2. Have the students role-play their historical person, answering some of the questions as the student might think their historical person would respond. Make sure the students explain their rationale behind their decisions.

Activity 4. Causes of the "Hysteria"

Use the Salem Witch Trials as an opportunity to explore the concept of the multiplicity of explanations and causes there can be for one event. Ask students to brainstorm a list of reasons why they think the Salem Witch Trials might have happened, which you can then write on the board. Ask them to support their reasons based on evidence they've learned in their study of the event. Add some of these Causes for the Outbreak of Witchcraft Hysteria in Salem , available via the EDSITEment reviewed Digital History website, to their list. Discuss the possibility that there was more than one cause of this event. Ask students to identify other historical events to which there were many causes. To extend this lesson, you can ask your students to write a short essay underlining some of the causes of the Salem Witchcraft hysteria.

- What kind of evidence was used during these trials?

- Were the accused innocent until proven guilty?

- Think about the vocabulary used in these court cases. Who makes reference to the Bible - the accused, the judges, the accusers, everyone? When do they reference the Bible? Why do you think they make these references?

- What were the punishments for witchcraft? Were they appropriate punishments?

- Who were the witnesses, if any? What did they add to the court proceedings? Was their testimony useful? Does it seem to have been taken into account by the judge? To which witnesses, or which testimonies, is more attention paid?

- What pressures did the accusers face? The judges?

- What kinds of things were the 'witches' accused of causing to happen?

- Have students write a story, letter, or diary entry from the perspective of one of the afflicted. The writing should involve some or all of the following: personal feelings of the historical figure, description of 'fits' and other sensations experienced by the 'afflicted', an accusation, a court trial or recollections from a court trial, remorse. If students prefer, they may write a story, letter, or diary entry from the perspective of one of the accused, or from a judge or other court official. Again, the writing should be relevant to the historical event. Use these stories as an insight into the depth of understanding students have about the experience of the Salem Witch Trials. Students should either orally present their work or provide a written essay justifying the choices they made in their entry. What historical evidence supports their viewpoint?

- As a possible introductory activity before examining life in Puritan New England (in Activity 1), have your students analyze their own belief systems so that they can better see the similarities and differences between their culture and that of Salem at this time. Ask your students to write down what they know about the religion to which they ascribe, or the rules that they have to follow as a result of being a part of their particular cultural heritage or society. This may be a good take-home activity, in which parents can also be involved. See attached sample worksheet: What are the Cultures that Shape You?

- If you wish to enter the realm of historical fiction, a younger audience (ages 9–11) might appreciate The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth George Speare. A more mature audience might appreciate The Crucible by Arthur Miller, or even The Scarlett Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. EDSITEment has a lesson plan on The Crucible, Dramatizing History in Arthur Miller's The Crucible .

Recommended Websites

- Digital History: The Puritans

- Digital History: The Puritan Idea of the Covenant

- Words About the Word 'Witch'

- Causes for the Outbreak of Witchcraft Hysteria in Salem

- Important Persons in the Salem Court Records

- Native American Indians 1680–1720

- Place in Time: Land and People

- Points of Contact: Sharing and Adapting

- Struggle for Freedom: "Run-away from his Master"

- Working: "Servant for Life"

- "Black Yankees": Slavery in New England

- Newcomers 1680–1720

- John Dane Battle's Life's Temptations

- petition for bail from accused witches

Materials & Media

Understanding the salem witch trials: worksheet 1, understanding the salem witch trials: worksheet 2, related on edsitement, salem witch trials: understanding the hysteria, arthur miller’s the crucible : witch hunting for the classroom, harrowing halloween: spooky, supernatural, and suspenseful, dramatizing history in arthur miller's the crucible.

The Salem Witch Trials

Written by: Malcolm Gaskill, University of East Anglia

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why environmental and other factors shaped the development and expansion of various British colonies that developed and expanded from 1607 to 1754

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative should accompany the Anne Hutchinson and Religious Dissent Narrative to explore the topic of religious toleration in the New England colonies.

In January 1692, in the village of Salem, Massachusetts, the nine-year-old daughter and eleven-year-old niece of a contentious minister, Reverend Samuel Parris, began having strange fits and seeing apparitions of local women they said were witches. A doctor diagnosed bewitchment, which meant that others were to blame for the girls’ possession, to which Parris responded with prayer. When this failed, Parris pressured the girls to identify the suspected witches. Meanwhile, other girls in Puritan households had supposedly been afflicted. Soon, three women had been accused of witchcraft, including the slave Tituba, who had performed a counter magical spell by baking a witchcraft victim’s urine in a cake and feeding it to a dog. The three women were arrested and jailed. The accusations gathered momentum and a panic set in.

Villagers were emboldened to voice their own suspicions of other witches, which led to more arrests. The accused were brought to the public meetinghouses and urged to confess so they could be brought back into the Christian fold. Most people gave credence to “spectral evidence”, evidence based on visions and dreams, in which the afflicted claimed they could see invisible spirits flying around the room and causing them pain. Even a four-year-old girl, the daughter of one of the accused, Sarah Good, was imprisoned for witchcraft. Before long, the witch hunt had spread to several neighboring communities.

Some people doubted the wild accusations that were tearing apart the communities. For example, Reverend Cotton Mather, a Boston minister, believed in witchcraft but had initial doubts about the outbreak. He questioned the use of spectral evidence, because in English law it was grounds for suspicion but not proof. Mather offered to provide spiritual guidance to the afflicted and cure their ills through prayer and counseling. Unlike the case in most witch hunts, in this one, only those who refused to confess were hanged, for clinging obstinately to Satan.

In May, the governor of Massachusetts, William Phips, set up a special court to deal with the forty-odd people who had been charged. A wealthy merchant, Samuel Sewall, sat on the court, and Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton presided. Many of the accused were perceived to be outsiders in some way, tainted by association with Quakers, American Indians, and non-English European settlers. People living closer to the town were also more likely to be suspects, as kinship groups and sections of town accused other kinship groups and sections of town with whom they were at odds.

The court convened on June 2 for the first trials, and on the basis of unprovable charges and spectral evidence, Bridget Bishop was found guilty and hanged. One of the judges, Nathaniel Saltonstall, was so outraged by the proceedings that he immediately resigned. A few days later, several clergymen published a statement, “The Return of Several Ministers,” expressing their own dissatisfaction with the use of spectral evidence and asking for greater burdens of proof. Nevertheless, the trials continued despite the travesty of justice that was recognized at the time. The conviction rate was unusually high, mainly because more than fifty suspects confessed, presumably to evade the noose. Puritans saw in the large numbers only mass allegiance to Satan, which, in turn, led to more accusations. The psychological pressures were intense, and some confessed “witches” recanted, thus sealing their fates.

With the stamp of this seal, William Stoughton, the chief judge who presided over the Salem witch trials, sent Bridget Bishop to her death.

The court convened again in late June, with more than one hundred accused witches in jail. Five more were tried and executed, followed by another five in August, and eight in September, fourteen women and five men. Elizabeth Proctor was found guilty but received a reprieve because she was pregnant. Giles Corey, who refused to plead, was pressed to death beneath a growing blanket of stones; his wife Martha was hanged. The deaths caused profound unease, including among previously enthusiastic ministers and magistrates. Reverend Increase Mather delivered a sermon in which he asserted, “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape, than that one innocent person should be condemned.”

As in European witch trials (where an estimated sixty thousand accused witches were executed in the preceding centuries), the problem was using spectral evidence as proof, which, it was argued, may have been the Devil’s illusion to foment discord. Perhaps Satan’s goal had been not to recruit witches but to trick the court into executing the innocent. Particular weight had been placed on the girls’ testimony and on the confessions of the accused, both of which were unreliable. In late October, the Massachusetts Court called for a day of fasting and prayer for reflection on the hysteria. A few days later, Governor Phips met with Stoughton to decide the fate of the court and decided to halt the trials. The jailed were released.

In 1855, Thomkins H. Matteson painted Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692. Jacobs was one of the colonists the court convicted of witchcraft and sentenced to death. How has Matteson conveyed the climate of hysteria that overtook the community of Salem and led to the witch trials?

Samuel Sewall, one of the judges, regretted the role he had played in the witchcraft trials and wondered whether the subsequent misfortunes of his own family, and of all New England, might be divine punishment for shedding innocent blood. In January 1697, he stood bare headed in church in Boston while the minister read the following apology:

Samuel Sewall, sensible of the reiterated strokes of God upon himself and family; and being sensible, that as to the guilt contracted upon the opening of the late commission of Oyer and Terminer at Salem (to which the order for this day relates) he is, upon many accounts, more concerned than any that he knows of, desires to take the blame and shame of it, asking pardon of men, and especially desiring prayers that God, who has an unlimited authority, would pardon that sin and all other his sins, personal and relative; and according to his infinite benignity, and sovereignty, not visit the sin of him, or of any other, upon himself or any of his, nor upon the land. But that He would powerfully defend him against all temptations to sin, for the future and vouchsafe him the efficacious, saving conduct of his word and spirit.

The jurors apologized later that same year. They admitted that, because they had not been “capable to understand nor able to withstand the mysterious delusions of the powers of darkness,” they were “sadly deluded and mistaken” in believing weak evidence and had caused the deaths of blameless people.

The factors that led to the 1692 Salem witchcraft outbreak were indeed complex. Much of the conflict fueling the trials originated in tensions between a traditional Puritan lifestyle based on piety and subsistence farming, and an increasingly worldly, capitalist outlook. Some Puritans complained of “declension” – a waning of godly ideals beginning in the 1630s, when Massachusetts Bay was settled. Friction between town and village had also developed over governance: Villagers resented paying taxes to maintain a distant town church and wanted independence.

The accusations may also have reflected tension between neighbors. Some scholars blame them on the fantasies and hysteria of children, and possibly even ergotism (a form of poisoning from a potentially hallucination-causing fungus that grows on rye) and an encephalitis epidemic. Gender also seemed to be significant: Were propertied women the victims of envious men? The Puritans believed witchcraft was God’s punishment for sin, either by allowing the Devil to convert so many witches or by turning fearful people against innocent neighbors. The Puritans believed in the existence of the Devil and his evil minions, who they thought could intervene in human affairs, tricking some into following them by practicing witchcraft.

The witchcraft outbreak was intensified across New England by political uncertainty during the years between the loss of the Massachusetts charter in 1684 and the granting of a new one by the English crown in 1691. The Glorious Revolution of 1689-1690 led to war with France, which, in turn, reignited war with American Indians in New England. These events all contributed to an atmosphere of profound insecurity and danger, spiritual and physical, though perhaps none really adequately explain the Salem witchcraft outbreak of 1692.

Review Questions

1. During the late seventeenth century and the events surrounding the Salem witch trials, what was considered “spectral evidence”?

- Evidence compiled from witnesses not physically present at the crime

- Evidence based on religious beliefs

- Evidence based on visions and dreams

- Evidence not accepted by court magistrates

2. How was the use of “spectral evidence” in trials of those accused as witches different in the New England colonies and in England?

- In English law, spectral evidence was grounds for suspicion, not proof.

- There was no difference in the use of spectral evidence.

- Spectral evidence was not admissible in English courts.

- The issue of spectral evidence never came up in England.

3. What was the fate of those who confessed to being witches in Salem Village?

- They were immediately hanged on the grounds that there was no doubt as to their guilt.

- Only those who refused to confess were hanged for clinging obstinately to Satan.

- Men tended to be acquitted whether or not they confessed.

- Regardless of whether they confessed, some were burned and some hanged.

4. Why was the conviction rate of accused witches in Salem so high?

- People were not hanged if they confessed, so many confessed to save their own lives.

- Many people genuinely believed they were witches.

- Many people were actually engaging in various witch rituals.

- Salem Village had an unusually large population.

5. What event launched the beginning of witchcraft accusations in Salem?

- A slave woman named Tituba confessed to witchcraft.

- Farm animals started disappearing.

- A young girl began having strange fits.

- A large comet appeared in the sky.

Free Response Questions

- Analyze potential causes of the witch trials in Salem and the surrounding area of Massachusetts. Which is the best explanation? Justify your answer.

- Explain why the accusations of witchcraft were acceptable to Puritans in seventeenth-century Massachusetts.

AP Practice Questions

“The humble petition of Mary Easty unto his excellencies Sir William Phipps to the honoured Judge and Bench now sitting In Judicature in Salem and the Reverend ministers humbly sheweth that whereas your poor and humble petitioner being condemned to die do humbly beg of you to take it into your judicious and pious. . . . I would humbly beg of you that your honors would be pleased to examine this afflicted persons strictly and keep them apart some time and like-wise to try some of these confessing witches. I being confident there is several of them has belied themselves and others as will appear if not in this world I am sure in the world to come whither I am now agoing and I question not but you’ll see an alteration of these things they say myself and others having made a league with the devil we cannot confess I know and the Lord knows as will shortly appear they belie me and so I question not but they do others the Lord above who is the searcher of all hearts knows that as I shall answer it at the tribunal seat that I know not the least thing of witchcraft therefore I cannot I dare not belie my own soul I beg your honers not to deny this my humble petition from a poor dying innocent person and I question not but the Lord will give a blessing to your endeavors.”

Petition of Mary Easty to the Court, 1692

1. The view expressed in the excerpt provided reflects the request made by Mary Easty to

- consider that although she is innocent, most of the others accused were really witches

- keep the accused and “confessing witches” apart

- stop the trials altogether because they are morally and spiritually wrong

- question the authority of the judges to pass sentence on so many people

2. Which of the following most likely led to the events described in the excerpt provided?

- The introduction of Slave Codes in Massachusetts society

- The strict nature of gender roles in the late seventeenth century

- The English legal system

- The strict religious practices in seventeenth-century colonial New England

Primary Sources

Cotton Mather’s Account of the Salem Witch Trials: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/cotton-mather%E2%80%99s-account-salem-witch-trials-1693

Suggested Resources

Boyer, Paul, and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England . New York: Norton, 1998.

Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 . New York: Knopf, 2002.

Ray, Benjamin C. Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692 . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

SALEM WITCHCRAFT TRIALS RESEARCH GUIDE

The Salem Witch Trials were a series of hearings before county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people, including several children, were accused of witchcraft by their neighbors. In total, 25 people were executed or died in jail during the trials. The preliminary hearings in 1692 were conducted in various towns across the province: Salem Village (now Danvers), Ipswich, Andover, Topsfield, and Salem Town. The best-known trials were conducted by the Court of Oyer and Terminer in 1692 and the Superior Court of Judicature in 1693, both in Salem Town.

The original manuscripts in this collection were digitized as part of the New England’s HIdden Histories project and are held by our project partners, the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum . Further information about the collection can be found in the Phillips Library's finding aid .

Many of the documents were previously digitized by the University of Virginia as part of their Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project , which began in 1999. In 2017, members of the CLA and Phillips Library staff found several documents in the Phillips Library’s collection which had not yet been digitized. These documents were digitized as part of our New England's Hidden Histories project and may be accessed below or in our digital archive .

For ease of use, we have provided information about all of the documents in the collection here, regardless of where the digitized versions can be accessed. Documents only available through the University of Virginia site can be found in the Related Materials section.

MATERIALS DIGITIZED BY NEHH

These documents are organized alphabetically by the last name of the accused, and then in chronological order for each case. Links to the digitized records are provided for each individual. All documents previously digitized by the University of Virginia’s Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project are indicated with an asterisk next to each individual’s name and can be accessed on their website at https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/archives/eia.html .

Mary Barker*

Mary Barker of Andover was 13 years old in 1692, when she and other members of her family were accused of witchcraft by Samuel Martin and Moses Tyler. Shortly after her arrest on August 29, 1692, Barker confessed and accused two others (Goodwives Faulkner and Johnson) of forcing her to sign the "Devil's book." She was eventually found not guilty and released.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 August 29 Accusers: Bartholomew Gedney, John Hathorne, and Jonathan Corwin

William Barker, Jr.*

14-year-old William Barker Jr. from Andover, MA was the first cousin of Mary Barker and was arrested shortly after her. William Jr.'s father, William Barker Sr., was also arrested but later escaped. On the day of William Jr.'s arrest (Sep. 1, 1692) he confessed to witchcraft and also accused one "Goody Parker" of the same crime. Court magistrates later arrested Mary Ayer Parker, one of several women with the Parker surname living in Andover, who was subsequently executed. This has led to speculation that Mary Ayer Parker was not the intended target of William Jr.'s accusation. William Jr. remained in prison until 1693 but was eventually acquitted.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 September 16 Accusers: Bartholomew Gedney, John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and John Higginson

Sarah Bridges*

17-year-old Sarah Bridges initially maintained her innocence upon her arrest on August 25, 1692. She did, however, accuse her stepsister, Hannah Post, of witchcraft in the same testimony. Later she would also confess, claiming that there were an additional 200 witches in the Salem area. She was found not guilty.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 August 25 Accusers: The Justices of Salem

Carrier Family

Several members of the Carrier family of Andover were accused of witchcraft. These included siblings Sarah (8), Thomas (10), Andrew (15), and Richard (18), along with their mother Martha Allen Carrier. Martha was arrested on May 28, 1962, and her children were also taken into custody and examined. Their mother was later found guilty and hanged along with George Burroughs, John Proctor, George Jacobs Sr., and John Willard on August 19, 1692. According to the account of John Proctor who was imprisoned with them, the Carrier children were coerced by torture into pleading guilty and testifying against their mother. They were later released.

Andrew Carrier*

Document: Examination Date: 1692 July 22 Accuser: Unsigned

Richard Carrier*

Sarah carrier*.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 September 2 Accuser: Dudley Bradstreet

Thomas Carrier, Jr.*

Document: Examination Date: 1692 September 2 Accuser: Dudley Bradstreet

Rebecca Eames

51-year-old Rebecca Eames was accused of practicing witchcraft on Timothy Swan, a claim corroborated by members of the Putman family and related individuals. She was arrested directly after the public execution of George Burroughs, Martha Allen Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., John Proctor, and John Willard on August 19, 1692, having been accused of inflicting pain on a fellow spectator. Her son and grandson were later also accused. Eames was tried and convicted on September 17th along with nine others, all of whom were condemned to death. Four of the nine were hanged on September 22, but Eames was spared when the court dissolved in October. She remained in prison until early December, when she petitioned to be exonerated, claiming that she had pled guilty on the advice of fellow inmates Abigail Hobbs and Mary Lacey.

Document: Examination (2nd) Date: 1692 August 31 Accuser: Unsigned Document: Certification of Confession Date: 1692 September 15 Accuser: John Higginson

Ann Foster of Andover was a 75-year-old widow, originally from London. She was accused by the Salem children Ann Putnam Jr. and Mary Walcott of inflicting a fever on Elizabeth Ballard of Andover. Putnam and Walcott had been brought in by Salem magistrates to "detect" the witch responsible for the affliction. Foster refused to confess despite probable coercion by torture, but her resolve was broken when her accused daughter, Mary Foster Lacey, Sr. testified against her mother, presumably in an attempt to save herself and her child. The resulting guilty plea proved ineffectual and both women were sentenced to death on September 17, 1692. They were spared by the dissolution of the court in October, but Ann Foster died after 21 weeks in prison on December 3rd.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 July 21 Accuser: Unsigned

Sarah Good was one of the first three women to be accused of witchcraft in Salem in February 1692, along with Tituba and Sarah Osborne. Good had fallen on hard times after litigation erased her family's wealth and two consecutive marriages to paupers left her destitute. She was often homeless and earned a living by begging, probably leading to an unsavory reputation in the town. On February 25, 1692, Abigail Williams and Elizabeth Parris claimed to have been bewitched by Good, who was tried and found guilty despite maintaining her innocence throughout the entire process. The resulting death sentence was delayed because she was pregnant. The newborn child, Mercy Good, died shortly after birth. Good was hanged on July 19, 1692 along with Elizabeth How, Susannah Martin, Rebecca Nurse, and Sarah Wilds.

Document: Testimony Date: 1692 June 29 Accuser: Samuel Sibley

Sarah Hawks*

21-year-old Sarah Hawks was arrested for witchcraft along with her stepfather, Samuel Wardwell, her mother, Sarah Hawks Wardwell, and her half-sister Mercy Wardwell. Samuel Wardwell was found guilty and hanged on September 22, 1692, but Sarah and her other relatives escaped execution and were later released from prison.

Document: Examination Date: 1692 September 4 Accusers: Bartholomew Gedney, John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and John Higginson

Elizabeth How/Howe

Elizabeth How's involvement in the witchcraft crisis began ten years prior to the official trials in Salem. In 1682, a young girl from Topsfield named Hannah Trumble began experiencing fits and accused How of making her ill through witchcraft. How's reputation was irreparably damaged, and she was refused admittance to Ipswich Church. When the troubles began in Salem in 1692, How was again accused, this time of afflicting Mary Walcott and Abigail Willams. Their testimony was corroborated by Mercy Lewis, Mary Warren, Ann Putnam Jr., and several others in the town. How was arraigned in the first Salem trial on June 30, 1692, and, despite fervent support from family and friends, was found guilty and sentenced to death. She was executed along with Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, Sarah Wilds and Susannah Martin on July 19th at Gallows Hill, Salem.