- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Foreign aid as foreign policy tool.

- Clair Apodaca Clair Apodaca Department of Political Science, Virginia Tech

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.332

- Published online: 26 April 2017

The majority of countries around the world are engaged in the foreign aid process, as donors, recipients, or, oftentimes, both. States use foreign aid as a means of pursuing foreign policy objectives. Aid can be withdrawn to create economic hardship or to destabilize an unfriendly or ideologically antagonistic regime. Or, conversely, aid can be provided to bolster and reward a friendly or compliant regime.

Although foreign aid serves several purposes, and not least among them the wish to increase human welfare, the primary reason for aid allocations or aid restrictions is to pursue foreign policy goals. Strategic and commercial interests of donor countries are the driving force behind many aid programs. Not only do target countries respond to the granting of bilateral and multilateral aid as an incentive, but also the threat of aid termination serves as an effective deterrent. Both the granting and the denial of foreign assistance can be a valuable mechanism designed to modify a recipient state’s behavior.

Donors decide which countries will receive aid, the amount of aid provided, the time frame in which aid is given, and the channel of aid delivery. The donor’s intentions and the recipient’s level of governance determine the type or sector of foreign aid. States can choose between bilateral or multilateral methods of disbursing foreign assistance in order to pursue their interests. Although bilateral disbursements allow the donor state to have complete control over the aid donation, the use of multilateral forums has its advantages. Multilateral aid is cheaper, it disperses accountability, and it is often viewed as less politically biased.

Foreign aid, once the exclusive foreign policy instrument of rich powerful states, is now being provided by middle-income countries, too. The motivation for foreign aid allocations by nontraditional donors parallels the motives of traditional Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors. A main difference between traditional and nontraditional aid donors is that nontraditional aid donors generally do not place conditionalities on their loans.

The issue of fungibility can obstruct the donor government’s purpose behind the allocation of foreign aid. If the preferences of the recipient government are different from those of the donor, the recipient can often divert the aid and use it for other purposes. A recipient government may reallocate its budget after it determines how much aid it is slated to receive. The recipient government will redirect its resources to areas it deems a priority that cannot be funded externally, for example the military or prestige projects.

- foreign aid

- foreign policy

- nontraditional donor

- multilateral trust fund

- fungibility

Introduction

Foreign policy can be defined as a country’s behavior with regard to other states in the international arena, driven by its need to achieve its goals. Although the country’s goals can be economic or ideological, or to solve international problems, security concerns have always dominated the foreign policy agenda. States have several tools they can use to further their foreign policy. Chief among these options are diplomacy, cooperation and association agreements, trade, economic sanctions, military force, and the use of foreign aid. Foreign aid, then, is one of a number of tools that policymakers can use to further their foreign policy goals. Foreign aid also allows the donor state access and influence in the domestic and foreign affairs of other states (Apodaca, 2006 ). Tarnoff and Lawson ( 2016 ) report that U.S. leaders and policymakers view foreign assistance as an “essential instrument of U.S. foreign policy” which has “increasingly been associated with national security policy” (p. 1). Foreign aid is an expedient tool for the diplomat. It helps governments achieve mutual cooperation on a wide range of issues.

The objective of foreign policy is to influence foreign governments and shape international affairs to suit the state. Generally speaking, states have two overarching goals in their dealings with other states in the international system: to maintain and protect the status quo or to change the status quo (Palmer & Morgan, 2006 ). As a tool of foreign policy, foreign aid is provided to a recipient country as either a reward for some behavior or as an inducement to change behavior. The provision of foreign aid is the carrot that influences the recipient’s policy choices or other behaviors. The termination of aid, the stick, can also be used to alter a recipient country’s behavior. Indeed, all foreign aid comes with strings attached, 1 a fact U.S. foreign policy specialists recognize: “Foreign aid is a particularly flexible tool—it can act as both carrot and stick, and is a means of influencing events, solving specific problems, and projecting U.S. values” (Tarnoff & Lawson, 2016 , p. 1). Decisions on how, where, and when to allocate foreign aid is made by political leaders in the donor country. They base these decisions on the government’s perceived national interests, broadly defined. Consequently, foreign aid is used as a means of pursuing foreign policy objectives.

Foreign aid can also be used to complement to military intervention. A study by Kisangani and Pickering ( 2015 ) found that donor-state military interventions have a significant effect on that state’s foreign-aid allocations. During and after an intervention, foreign aid to the target state increases significantly. Foreign aid is a tool used to supplement the use of military force to ensure that foreign policy goals are met and, once met, secured. Foreign aid “demonstrates the benign intentions of the intervention (toward the target populace, if not the target government), and that the military action was undertaken to further ideals shared within the broader international community” (Kisangani & Pickering, 2015 , p. 219). The goals of encouraging good governance and democracy, fostering human rights standards, or alleviating poverty in the target state cannot be achieved with military might alone. They often require the provision of foreign aid.

Academic researchers have studied foreign aid since the establishment of aid giving. Researchers are perplexed as to why and under what circumstances the leaders of one state would provide valuable resources to another state. The continued and increased flow of foreign aid to underdeveloped states is all the more puzzling since because studies have shown that the official reason for aid allocation, economic development, has proven elusive. Is the problem of aid ineffectiveness a result of donor’s motives? Is it due to the channels of aid disbursement? Or perhaps it is about the fungibility of aid itself. The following sections cover several aspects of the relationship between foreign aid and foreign policy, beginning with a general discussion of what political leaders and researchers include as foreign and followed by discussions of the allocation of foreign aid, channels of foreign aid disbursement. an inquiry into who provides foreign aid and why, and, finally, a consideration of the issues related to the fungibility of foreign aid.

What Is Foreign Aid?

The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines foreign aid as resource flows provided by official agencies with the intent to promote economic development. The resources must be given on concessional terms with at least a 25% grant element (OECD, website). The resources can be economic in nature, such as financial contributions, but can also include technical assistance and commodities (such as food aid or agricultural equipment). The costs of humanitarian aid within peacekeeping operations can also be considered foreign assistance. Several states include the gift or sale at concessional rates of military equipment as foreign aid, but the OECD specifically states that official development assistance (ODA) should not include military aid or antiterrorism activities. ODA includes the following sectors of aid allocation as classified and defined by the OECD website ( https://data.oecd.org/development.htm ):

Social Infrastructure and Services, including funding for education, health, and the promotion of civil society. In 2014 , 39.4% of all sector aid was allocated to social infrastructure.

Economic Infrastructure, which funds projects for transportation, energy, communications, and banking and financial services development, 23.4% of aid went to economic infrastructure in 2014 .

Production Sectors, which include funding for agriculture, forestry and fishing, industry, mining and construction. In 2014 , 9.1% of ODA went to the production sectors.

General Budget Support funds, which are contributions to government budgets and support for macroeconomic reforms. Only 1.5% of aid was apportioned to unearmarked 2 contributions, allowing governments to use these funds as they see fit since aid is not tied to a specific project or program.

Humanitarian Assistance, which encompasses emergency response, reconstruction and disaster prevention, and constitutes 10.8% of ODA. Humanitarian Assistance funds are donated to assist in man-made or natural disasters.

Multisector Support funding, which is geared to projects which straddle several sectors but basically include the environment and biodiversity. Multisector support is a recent category of aid and accounted for 10.2% of ODA in 2014 .

Action Relating to Debt, which includes debt swaps, debt forgiveness, and debt relief. A mere 0.43% of ODA is directed to issues of debt relief.

The remainder is unspecified aid. The data on sector aid are taken from the OECD International Development Statistics online CRS Aid Activities dataset ( https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1 ).

While aid aimed at economic infrastructure is usually targeted at countries with good governance and mature economic institutions, countries that lack such capacities usually receive aid in the form of social-sector assistance. Social-sector aid allows donors to target the welfare of the people, generally channeling aid through NGOs or multilateral organizations in ways that avoid bad policies of or corruption in recipient governments. Government involvement in education and health is less mandatory than government involvement in trade policy because substitutes for government institutions and procedures may be found in civil society or provided by NGOs and multilateral aid organizations (Bermeo, 2007 ). Typically, as disasters (manmade or natural) overwhelm a government’s ability to respond, foreign aid is directed toward sectors (normally humanitarian assistance) that require less government intervention. Aid directed at general budget funds, meanwhile, is given with the implicit understanding that governments can use these funds as they see fit. Donors become less reliant on good government policies as they move away from economic infrastructure and general budget support to production sector funding, to humanitarian assistance and the social infrastructure sector (Bermeo, 2016 ). Similarly, Akramov ( 2012 ) finds that aid directed at the production sector can be effective at promoting growth even in bad policy environments. Economic infrastructure aid, however, is effective only in countries with medium to high governance ratings. Years of research indicate that the recipient state’s internal capacity to absorb aid matters quite a bit in the donor’s decision on how aid should be allocated. Donors vary the sectorial composition of their aid in response to perceived governmental quality. Countries that are well-governed receive greater shares of their ODA in the budget, economic, and production sectors.

The Many Motives for Foreign Aid

Official governmental rhetoric declares that development and poverty reduction are principal reasons for granting foreign assistance. Foreign aid is given to a recipient country to facilitate economic development, alleviate poverty, and improve human welfare. Aid contributes to global security by tackling threats to human security, such as human rights violations, disease, population growth, environmental degradation, peacemaking, and the growing gap between the rich and the poor. Poverty and extreme inequalities are often causes of social instability and civil unrest, which, in turn, can produce flows of refugees and acts of terrorism. Thus, aid helps build a safer, more peaceful, and more secure world. Foreign aid is provided to many countries but is concentrated in countries reflecting the priorities of the international community and individual donor states. Lumsdaine ( 1993 ), for example, found that humanitarian concerns and moral values were a primary motivation in the allocation of multilateral foreign aid.

Lancaster ( 2007 ) argues that the provision of foreign aid has developed into an international norm. Rich countries provide assistance to poor countries to better the human condition. States are subject to the norms of behavior established by the international community. The allocation of foreign aid has become an accepted and expected standard of behavior among developed states, a standard that is now being recognized among a greater number of middle-income states. Most developed states have established foreign aid agencies, instituted foreign aid mandates, processes and procedures, and joined the DAC. Donor states provide foreign aid to alleviate poverty and foster development in the neediest underdeveloped countries. Lancaster admits, however, that given the number of potential recipients and the ever-expanding need (due to disasters, poverty, or economic crises), donors can also use their aid as incentives or as payments for approved behaviors, or to signal a desire to expand political relationships between donors and recipients.

Consequently, researchers have determined that foreign aid is often provided for interests other than developmental or humanitarian reasons. Bigsten, Platteau, and Tengstan ( 2011 ) estimated that if the European Union countries were to choose to optimize the distribution of foreign aid for the sole motive of reducing poverty, they would need to reallocate $19 billion of the $27 billion of EU aid—that is, over 70% of EU foreign aid—directing it to only the 20 poorest countries. Bigsten et al. ( 2011 ) determined that “the reallocation would lead to a modest increase of poverty among the donor darlings and a large decline in poverty in the orphan countries” (p. 11). However, the EU countries do not wish to optimize their foreign aid because they have economic and political purposes other than poverty reduction when they allocate aid.

Foreign aid is used predominantly to promote geostrategic interests, for the right to build and maintain foreign bases, to strengthen alliances, or to keep allied regimes in power. Foreign aid is also used to maintain friendly relations with foreign governments. Foreign aid facilitates cooperation, and it builds strong alliances. First, foreign aid can be used to maintain nations as allies. By economically or militarily supporting a friendly foreign government, the donor state can prevent the recipient state from falling into the enemy’s camp or from falling to domestic rebels. Second, foreign assistance may be granted in an attempt to gain foreign allies. And third, foreign aid can be used to win the hearts and minds of a population. For example, foreign assistance is viewed as an important instrument in the prevention of terrorist attacks by reducing the appeal of terrorist ideology. There is a general belief that foreign aid could reduce the likelihood of terrorist attacks by averting the causes of terrorism—namely, hopelessness and resentment as the result of extreme poverty, illiteracy, and hunger. Foreign aid would also be used to reduce poverty and inequality in the recipient state, thought to be a source of terrorist activity (Bush, 2002 ). Helping the poor increase their standard of living would also ensure that they would not fall prey to the ideological underpinnings of fundamentalists. Bush believed that “hope was an answer to terror” and that providing people with a positive future would lessen their desire to embrace a radical Islamic ideology. 3

Del Biondo ( 2014 ) concludes that the EU has moved closer to the United States in that its foreign assistance is more explicitly focused on security matters. Providing aid for antiterrorist programs, along with economic growth and development, as well as poverty reduction schemes in developing countries, safeguards European security. The United Kingdom’s Department for International Development ( 2001 ) claims that “many of the problems which affect us, such as war and conflict, international crime, refugees, the trade in illegal drugs and the spread of diseases like HIV and AIDS, are caused or made worse by poverty in developing countries. Getting rid of poverty will make for a better world for everybody.” Poverty and underdevelopment are also the underlying causes of the spread of disease, unwanted migration flows, and human rights violations. Thus, foreign aid is always in the service of foreign policy.

Geopolitical motives for foreign aid allocation have evolved over time and, in turn, affected the levels and direction of aid flows. During the Cold War, foreign aid was a tool Western states used to contain the spread of communism and to keep the power of the Soviet Union in check. In the post-9/11 era, foreign assistance is viewed as an important instrument in preventing terrorist attacks. Security concerns have, and will continue to have, a significant influence on the allocation of aid. Giving aid for geopolitically motivations aid is not an efficient use of aid, however, if purpose of the aid is poverty alleviation in the recipient country. But foreign aid can be successfully used to buy strategic concessions, such as the building of military bases or consolidating military alliances from the recipient government. Foreign aid can be a large component of foreign capital flows for many low-income countries, thus increasing their dependence on donor governments.

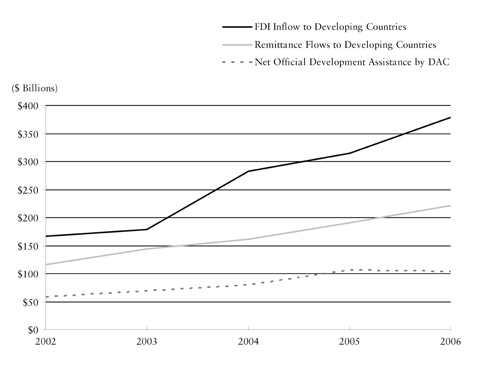

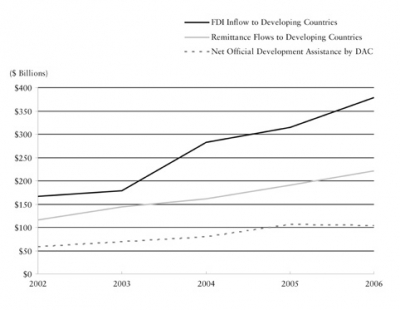

Foreign aid can also be used to further the economic interests of the donor state. For instance, it can be used to open foreign markets to multinational corporations headquartered in donor countries, to subsidize the donor’s domestic firms, or to provide employment for the donor’s domestic workers. Recipient countries that provide a favorable climate for foreign investment and trade receive more assistance. Data on the level and distribution of foreign aid reveals that it is mostly directed toward emerging or middle-income economies (those that are recipients of FDI and trade) at the expense of the poorest ones (Bertoli, Cornia, & Manaresi, 2008 ; Dreher, Nunnenkamp, & Thiele, 2011 ). Also, the giving of aid can secure access to vital raw materials (oil, minerals, etc.).

The commercial motive of foreign aid can be seen in the practice of tying aid. Tied aid is when a country binds its aid to the procurement of goods and services from the donor country. Tying aid occurs when, for example, a donor requires that aid recipients purchase the equipment, arms, materials, supplies, parts and services, or other commodities made in the donor country or from the donor’s corporations; use contractors or consultants from the donor country; or that the equipment be shipped via ships or airplanes flagged in the donor country. The intent is to increase market opportunities for the donor’s business interests. Tying aid is a common practice among donor nations. Radelet ( 2006 ) reports that, historically, the United States has tied approximately 75% of its aid, while Greece has tied 70%, and Canada and Austria have tied about 40% of their foreign assistance. In contrast, Norway, Ireland, and the United Kingdom do not tie their aid. Riddell ( 2014 ) reports that, overall, as much as 50% of ODA is tied in some fashion and that the tying of aid reduces its value by 15%–30%. Tying aid can reduce the value of the aid because it prevents the recipient country from buying the best-quality commodities at the lowest prices.

Colonial powers, historically, grant more aid to former colonies (Round & Odedokun, 2004 ). France, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom are substantial donors of foreign assistance to their former colonies. Alesina and Dollar ( 2000 ) have concluded that “an inefficient, economically closed, mismanaged nondemocratic former colony politically friendly to its former colonizer receives more foreign aid than another country with similar levels of poverty, a superior policy stance but without a past as a colony” (p. 33). Aid by ex-colonial powers can help continue or regenerate colonial spheres of influence and reinforce political alliances. The aid provided by France is often cited as an example of a former colonial power wishing to maintain the special relationship with its ex-colonies. Aid provided by the French is used to fund educational training in the French language and culture.

Aid can be given to prevent or offset the effects of global negative externalities that can potentially affect the developed countries (such as infectious diseases, environmental contamination, or debt default). For example, donors will lend more money to countries in debt simply to keep recipient countries from falling into arrears (Birdsall, Claessens, & Diwan, 2003 ) or to provide humanitarian aid to accommodate refugees. Continuing to provide foreign aid to highly indebted countries can be used to reduce the risk that they will default, which could threaten the donor’s economy. And providing aid to countries neighboring a conflict or disaster can stem the flow of refugees seeking asylum in the West.

Foreign aid can also be provided to increase a country’s prestige. Van der Veen’s ( 2011 ) research explains that the Dutch were determined to set a new international level on aid giving in order to project an image of good global citizen, while the Norwegians focused on matching or surpassing other Western nations in the allocation of foreign assistance. States adopt an identity and role in the international community, and some states choose to be viewed as generous global citizens.

If aid were solely motivated by foreign policy objectives and donor self-interest, then how the recipient uses the aid and the importance of the quality of governance in the recipient country should not matter. However, Kilby and Dreher ( 2010 ) show that in practice, states use foreign aid to achieve many overlapping foreign policy goals, including fighting terrorist threats, supporting strategically important countries, fostering relations with countries that maintain large bilateral trade or capital flows, and the championing humanitarian goals of reducing poverty, encouraging democracy, enhancing gender status, and improving human welfare.

Channels of Foreign Aid: Bilateral versus Multilateral versus Trust Funds

When pursuing foreign policy, including foreign aid policy, states can choose between bilateral or multilateral actions. Bilateral aid is resources that flow directly from one country to another. Bilateral aid can be delivered through the public sector, NGOs, or public-private partnerships with the recipient country. Those who advocate the use of foreign aid as a geopolitical foreign policy tool prefer bilateral foreign aid because of the strategic objectives to be gained. With bilateral aid, the donor retains control over the funds and determines who will be favored with aid and under what conditions. Most foreign aid is overseen, and frequently managed, by the donor (Riddell, 2014 ). Donors do not like to give up control of their aid 4 by channeling it through a multilateral agency, unless, of course, they have significant influence over the decision-making operations of the agency. The receipt of bilateral foreign assistance leaves the recipient obligated to the donor.

Aid that is channeled through intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank or regional development banks; the International Monetary Fund; UN agencies, most notably the United Nation Development Programme; and the OECD is known as multilateral aid. The aid becomes the development asset of the multilateral institution, which it then disperses based on the multilateral institution’s own decision-making process. The donor state cannot earmark or predetermine the aid’s use. Multilateral aid can only be delivered through the multilateral organization. Headey ( 2008 ) suggests that donors tend to channel their anti-poverty, development motivated assistance through multilateral institutions and use their bilateral aid to pursue geopolitical objectives.

The use of multilateral trust funds, or what is often referred to as “multi-bi” assistance, “allow[s] donor governments to cooperate with like-minded donors only, target their aid to specific countries, and development objectives while using the financial and, by and large, the implementation infrastructure of the multilateral organization which hosts them” (Eichenauer & Knack, 2016 , p. 2). Earmarking allows the donor and likeminded countries greater influence in the allocation of multilateral aid decisions by targeting priority issues or economically and politically important countries. In this way, donors can circumvent the multilateral development banks’ allocation of aid based on country performance, institutional capacity, and need. The ability to use the multilateral institutions while maintaining control of their foreign aid is a widespread donor strategy. Reinsberg, Michaelowa, and Eichenauer ( 2015 ) reported that multi-bi aid accounts for 60% of all multilateral aid, and in 2013 , the World Bank was managing over 900 trust fund accounts. The Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund is one of the largest country-specific trust funds. The World Bank benefits from not only the additional fees it collects from donor countries (typically 2% to 5% of the trust fund), but the administration of the multilateral trust funds also allows the bank to increase its staff. The World Bank “holds, invests, and disburses funds,” thereby increasing its power and influence. The Bank’s management of the trust funds “underwrite[s] the Bank’s leadership in responding to international crises” (Independent Evaluation Group, 2011 , p. 9).

Why would states give up control over aid allocation policy by funding multilateral aid programs? Research has established that there are several advantages to using multilateral organizations to manage foreign aid.

Multilateralism is cheaper . Multilateralism is, in the opinion of Thompson and Verdier ( 2014 ), the solution to transaction costs, that is, the costs of negotiating (and renegotiating), monitoring and enforcing an agreement.

Burden sharing . There are 28 donor members of the OECD-DAC and another 29 non-DAC donors. This means that the costs and responsibilities for resolving global issues of poverty or disease eradication are not the burden of one country but based on the ability to pay. Kwon ( 1998 ) explains: “Those who would benefit most from a collective good and have the greatest resources to provide it will bear a disproportionate share of the costs, while “smaller” members of the group will bear a burden that is less than their share of the benefits and resources, behaving as free (or cheap) riders” (p. 39). Small donations can be combined with donations from other countries, amplifying their significance and providing help to recipient countries.

Deniability to the donor state’s own population . Using a multilateral aid agency allows the donor a certain degree of plausible deniability for the resultant outcomes thereby reducing the risk of criticism if the lending fails. Foreign aid does not have strong public support in most countries. But donor governments realize that aid is an important tool of foreign policy. Donors can fund but still distance themselves from politically controversial programs that may upset their domestic constituencies. Providing bilateral aid might not be politically astute if either the donor or the recipient citizenry objects to the funding. In 2013 , North Korea, Iran, and Cuba received a substantial amount of multilateral official development assistance, over $100 million each. Funding these countries, no matter the level of need, would be politically controversial in the United States. But as a major donor to the OECD, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United States is indeed helping to fund programs in unpopular regimes. Donors may direct their aid through multilateral venues when conditions in the recipient country are politically sensitive or fragile, dangerous for staff members, or if the donor simply wants to diffuse accountability.

Multilateral aid is politically neutral and more needs-driven . There is also a perception that multilateralism guarantees uniform treatment and, consequently, is more legitimate and more fair based on need and not politics. This is a particularly important point if the donor’s citizenry believes that bilateral aid is too political and that multilateral aid is more altruistic. Multilateral agencies do hold a degree of autonomy with respect to state control. Thus, it is believed that multilateral aid is less politicized and based more on need and institutional capacity. Bilateral aid, on the other hand, is often controlled by vested interests that direct aid for strategic and political ends (Nunnenkamp & Thiele, 2006 ). However, there is some evidence that multilaterals are not impartial either and can also be easily captured for political and economic gain. A study by Kaja and Werker ( 2010 ) found that membership on the executive board of the World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) resulted in approximately double the IBRD funding compared to countries that were not on the board. Favoritism rather than poverty reduction controlled IBRD lending. Similar research has shown that IBRD loans are heavily influenced by a recipient government’s temporary seat on the UN Security Council (Dreher, Sturm, & Vreeland, 2009 ; Kuziemko & Werker, 2006 ). However, Kaja and Werker ( 2010 ) also found that membership on International Development Association (IDA) board had no influence on IDA’s lending decisions. 5

Who Provides Foreign Aid?

Traditional foreign aid donors.

The first and most successful contemporary foreign aid initiative was the European Recovery Program (ERP), popularly known as the Marshall Plan. In 1947 , secretary of state George Marshall announced a United States proposal to rebuild Europe in the aftermath of World War II. World War II had completely destroyed the European economy and infrastructure, and a summer drought and exceptionally frigid winter in 1946–47 killed livestock and ruined crop production. The combination of the man-made disaster of war and the natural disasters of drought and blizzards, resulted in widespread starvation, wretched poverty, unemployment, and housing shortages in Europe. Although the Marshall Plan was motivated by humanitarian concern for the suffering of the European population, the plan also satisfied the strategic self-interests of U.S. foreign policy. United States leadership feared that with the destruction of the European economy and the growing misery of the European people, communism would gain a stronghold. The Marshall Plan proved to be very good for America’s economy, benefiting business, manufacturing, and agricultural interests by increasing U.S. exports and providing jobs to U.S. workers. Over the years, foreign aid has become an indispensable tool of U.S. foreign policy.

In Europe, the provision of foreign aid began with the independence of Europe’s colonies in Africa and Asia. Foreign aid flows to countries where EU donors have historically strong trade relations, investment interests, and colonial ties. Lancaster ( 2007 ) concluded that aid to former colonies has been based on the ex-colonies’ economic need, the desire to preserve the donor’s influence in those countries, and as a means of disengaging while keeping their reputations more or less intact. Aid was also seen as a means to prevent a massive return of settlers and emigrants. Maintaining secure export markets in former colonies is also an important motivation for European foreign assistance. Although these motives remain, the Library of Congress’s ( 2015 ) comparative analysis of foreign aid reports that

the major objective of the foreign aid policy of the EU is the reduction and the eventual elimination of poverty. In pursuing its foreign aid policy, the EU aims to promote human rights, gender equality, democracy, the rule of law, access to justice and civil society, the rights of the child and indigenous people, protection of the environment, and the fight against HIV/AIDS. (p. 10)

Yet issues of security, colonial history, and economic-energy interests redirect the EU’s foreign aid from solely humanitarian need to self-interested practicalities.

Foreign aid priorities vary widely among the individual states.

Lancaster ( 2007 ) states that Japan’s generous aid policy is the result of its reparation payments and its need to secure much-needed raw materials. Japan also used foreign assistance to increase its international reputation and status. Under Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, Japan was prohibited from maintaining a military (other than for self-defense) and was unable, until recently, to participate in international humanitarian operations. Thus, Japan relied on providing foreign aid to project its power and influence onto the international arena.

During the Cold War, Soviet foreign aid was given to build influence in nonaligned countries and maintain a sphere of influence with poor communist countries (particularly North Korea, North Vietnam, Cuba). In addition, the Soviet Union provided considerable amounts of foreign aid to African states to foster close relations and to secure access to raw materials. After the fall of communism, the Russian Federation became a recipient of foreign assistance. However, in the 21st century , Russia is a “re-emerging donor” of foreign aid ( Guardian , 2011 ). Russian foreign assistance reflects its historical Soviet roots for foreign aid allocations. The largest recipients of Russian aid in 2012 were the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Serbia, Mongolia, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea, and Syria (OECD, QWIDS, online). Russia’s sectorial focus is on health and food security (Hynes & Trzeciak-Duval, 2015 ).

Growth of Foreign Aid Donors

The highly developed countries in North America, Western Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia, as well as the middle-income countries of China, India, South Korea, Brazil and the oil-rich countries of the Middle East have established foreign aid programs. The importance of foreign aid as a foreign policy tool is substantiated by the fact that foreign aid recipients are also foreign aid donors. In addition to the 28 DAC donors, 6 the OECD identifies 29 non-DAC donors that provide significant amounts of aid annually. Researchers have only recently recognized the importance of nontraditional aid donors in the study of aid as a tool of foreign policy.

More recently developing countries, oftentimes foreign aid recipients themselves, have become foreign aid donors. The motivations for middle-income country foreign aid provisions largely mirror those of traditional donors. Foreign aid by middle-income countries is used to further foreign policy goals, to increase regional power, to advance national interests, and to strengthen commercial ties. Nontraditional (non-DAC) donors have learned that foreign aid can be a useful tool to win allies, garner support in international forums, and advance foreign policy objectives.

Nontraditional donors, it is claimed, have a better understanding of recipient needs and of programs that work (Dreher et al., 2011 ). Accordingly, based on this experience, non-DAC donors are less willing to provide general budget support, aid that allows discretionary use, or outright grants rather than subsidized loans (Davies, 2010 ). As with the DAC donors, much of non-DAC aid is tied (recipients are obligated to purchase goods and services from the donor country). Contrary to the criticism that DAC donors make recipient needs secondary to political, strategic, or commercial interests, it appears that DAC donors are more needs-oriented than non-DAC donors (Dreher et al., 2011 ; Fuchs & Vadlamannati, 2012 ). An empirical study by Dreher et al. ( 2011 ) found that non-DAC donors place less importance on recipient needs than do traditional DAC donors.

The belief that non-DAC donors respond to recipient need is belied by a study by Fuchs and Vadlamannati ( 2012 ). These researchers report that India provides foreign assistance to countries with a higher GDP per capita than India itself, thus underscoring the notion that foreign policy goals rather than human needs motivate the foreign aid allocations of India. Woods ( 2008 ) reports that energy security, increased trade, and new economic partnerships are the primary motivations for most non-DAC donors. Research by Fuchs and Vadlamannati ( 2012 ) confirms that assistance from non-DAC donors is even more self-interested than aid from DAC donors. Given that resources are more dear in poor countries, non-DAC donors require a “return” on the foreign aid investment.

A primary difference between DAC and non-DAC donors, however, is the willingness to provide aid “without Western lectures about governance and human rights” ( Economist , 2010 ). Thus, foreign aid between southern donors and recipients is provided based on mutual benefit, non-interference and respect for sovereignty so that aid is not contingent on human rights protection, the promotion of democracy, or the reduction of corruption (Mawdsley, 2012 ), highly valued conditionalities 7 that traditional donors place on their foreign aid. Funding by nontraditional donors allows countries to reject the conditionality-laden loans of the IMF, the World Bank, and bilateral Western donors (Pehnelt, 2007 ).

China has become one of the major foreign aid donors. 8 China provides aid to countries that accepted it as the legitimate government of the Chinese people. Dreher and Fuchs ( 2011 ) confirm that political concerns drive China’s foreign aid allocations, but no more so than other major donors. China’s aid is free of democratic, good governance, and human rights considerations. China foreign aid is directed towards infrastructure development requiring 50% of the construction contracts to be awarded to Chinese contractors and 50% of the materials to be procured by Chinese business (Kjøllesdal & Welle-Strand, 2010 ).

Many non-DAC Donors provide aid, not only in an attempt to legitimize themselves as regional leaders, but also to assist trade and investment deals. In 2014 , Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa, BRICS Group members, created two new international financial institutions, the New Development Bank (NDB), and the Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA). The BRICS set aside $50 billion in initial capital for infrastructure and sustainable development for low-income countries through the NDB, while the CRA had $100 billion in funds for countries in balance of payment difficulties due to short-term liquidity problems (Desai & Vreeland, 2014 ). Mwase ( 2011 ) suggests that BRICS donors allocate foreign aid to countries with weak institutions and poor governance because the World Bank and IMF deny aid to countries they determine to be too risky to finance. Countries who are ineligible for World Bank and IMF loans thus have a source of income provided by BRICS. BRICS have cultivated potential partners and allies from among those World Bank or IMF ineligible countries.

Also in 2014 , China, along with 21 Asia–Pacific nations, established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)—with China providing 50% of the initial capital—and the Silk Road Infrastructure Fund (SRIF)—where China is providing $40 billion in startup funds—to help fund infrastructure projects in Central and South Asia (Carsten & Blanchard, 2014 ). China, as a founding member of and the largest contributor to the newly established institutions, plays a significant role in all the new banks’ decisions. Thus, these new funding institutions strengthen China’s political and economic relations with other developing countries. Although the stated purpose of the newly created multilateral, yet regionally focused, development finance institutions (the NDB, CRA, AIIB, and the SRIF) is to complement, not challenge, the established assistance programs, scholars believe that the primary purpose of the banks is to solidify China’s role as regional leader while allowing it to extend its influence among developing countries and providing it with greater access to raw materials (Dixon, 2015 ).

Arab governments have long been major donors of foreign assistance. A report by Rouis ( 2010 ) found that Arab donors, principally Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates, allocate 1.5% of their gross national income to foreign aid, more than twice the United Nations target of 0.7%. Although Villanger ( 2007 ) reports that Arab aid is used to promote Islam, build Arab solidarity, and is focused on predominantly Muslim countries, Rouis ( 2010 ) acknowledges that Arab aid now extends to a greater number of countries:

At present, Arab ODA covers a wide range of countries, and especially poor countries in sub- Saharan Africa such as Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Somalia, and Sudan; and in Asia such as Cambodia, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, and Vietnam. (p. 2)

Like Western donors, Arab donors are strategically motivated in the allocation of foreign aid. Arab donors, however, do not place conditionalities of good governance, democracy, or human rights standards on their aid. But they do closely monitor the projects they fund to prevent corruption (Villanger, 2007 ). The sectorial focus of Arab aid is productive infrastructure.

Two other significant aid donors are also aid recipients: India and Brazil. OECD International Development Statistics ( http://stats.oecd.org/qwids/ ) report that, between the years 2005 and 2009 , Brazil received over $1.47 billion in official development assistance from all donors. Yet the Library of Congress ( 2015 ) writes that Brazil provided $1.8 billion in foreign aid between those same years. The OECD estimates that India furnished $539 million in foreign assistance in 2009 and 2010 and received over $5.3 billion in foreign assistance during that same time period. The Library of Congress also reports that whereas South Africa has “robust and fast-growing foreign aid programs” (p. 222), it still received over $1 billion in 2014 alone. Each of these countries tries to use its aid to influence the policies of the recipient country.

Does Foreign Aid Work as a Foreign Policy Tool? The Issue of Fungibility

Aid fungibility occurs when the recipient uses the aid for purposes other than what the donor intended or when donor aid substitutes for government funding (McGillivray & Morrissey, 2004 ). Fungibility occurs when the recipient government decreases its contribution to a project or program as a result of external funding. If a donor allocates foreign aid to build a hospital, the recipient government can redirect the funds it had intended to use to build that hospital to other projects. Foreign aid, then, frees up government revenue for spending in other sectors, such as the military, nonproductive government consumption for prestige projects, or tax reductions for the wealthy. Collier and Hoeffler ( 2007 ) reported that around 40% of African military spending is financed by OECD aid because of aid fungibility. This does not include outright military aid or aid that is provided to the government for general budget funds. Donors that are concerned about the recipient using the aid for purposes it was not provided for can choose to fund project aid (that is, specific investment loans for funding sanitation infrastructure or building a clinic, for example) 9 over programmatic aid (budgetary support funds, e.g.; Herring & Esman, 2001 ). Morrison ( 2012 ) notes that “there is little doubt that project-based aid is meant to reduce the discretion of recipient countries in terms of how to spend the money” (p. 60). In corrupt, poorly governed, or fragile states, donors will bypass recipient state institutions and disperse their aid through nonstate development partners, reducing the ability of central governments to divert funds (Dietrich, 2013 ). However, Briggs ( 2014 ) suggests that donors may use the fungibility of aid to accomplish foreign policy objectives; for example, if the donor’s citizens would not approve of their government’s support of an authoritarian regime, the donor could “turn a blind eye to fungibility if they wished to support a recipient leader” (p. 195). Indeed, Licht ( 2010 ) shows that donors were more likely to allocate aid to incumbent leaders if they faced an elevated risk of losing power.

For example, the United States’ bilateral economic assistance includes the category of Economic Support Funds (ESF). ESF funding, although officially listed as economic aid, is generally recognized as military assistance since it is used to financially support those countries considered politically and strategically important to the United States’ security interests. The US executive branch favors ESF since, as economic aid, it avoids the public debate and congressional challenges associated with the granting of military aid to authoritarian countries or those that abuse human rights (Ruttan, 1996 ). The ESF program is financial assistance for budget support that allows recipient countries to use their own resources to build up their defense infrastructures. It also includes the sale or grant of U.S. military arms and equipment. According to Tarnoff and Lawson ( 2016 ), 56% of ESF funding went to Egypt, the West Bank, Jordan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan in 2015 .

Conclusions: A Future for Foreign Aid?

In spite of the trillions of dollars provided by foreign aid donors over the past 70 years, global economic inequality persists and countries remain underdeveloped, both economically and politically. Yet though the level of aid transfers varies from year to year, depending on budgetary crises and global need, foreign aid is not going away. An early scholar of foreign aid, speaking about U.S. foreign assistance, wrote over 50 years ago, “Foreign aid as a political instrument of U.S. policy is here to stay because of its usefulness and flexibility” (Montgomery, 1962 , p. 9). These words are just as true in the 21st century . Foreign aid is a tool of foreign policy, not solely an instrument for the economic development of poor countries. However, scholars, such as Diamond ( 2008 ), believe that poverty reduction, the institution of good governance, and the growth of democracy in developing states are in the national interests of donor states. Funding foreign aid with conditionalities can be used to enhance national security, further economic and political interests, and ultimately empower the citizenry of poor countries. However, with the growth of nontraditional donors and their resistance to imposing the conditionalities of democracy and human rights on their lending, foreign aid may be further reduced to the crass, self-interested motivations of commercial or political interests. Given the differences over the motivations for providing foreign aid, it is hardly surprising that questions of whether aid has a future need to be asked and answered.

- Akramov, K. (2012). Foreign aid allocation, governance, and economic growth . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Alesina, A. , & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth , 5 (1), 33–63.

- Apodaca, C. (2006). Understanding U.S. human rights policy: A paradoxical legacy . New York: Routledge.

- Bermeo, S. (2007). Foreign aid, foreign policy, and development: Sector allocation in bilateral aid . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association 48th Annual Convention, Chicago.

- Bermeo, S. (2016). Targeted development: Aid allocation in an increasingly connected world . Research Paper. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2683664 .

- Bertoli, S. , Cornia, G. , & Manaresi, F. (2008). Aid effort and its determinants: A comparison of the Italian performance with other OECD donors (Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche Working Paper N. 11/2008). University of Florence, Italy.

- Bigsten, A. , Platteau, J. P. , & Tengstan, S. (2011). The aid effectiveness agenda: The benefits of going ahead (Contract No. 2010/25689. Final Report to the European Commission). Retrieved from http://www.delog.org/cms/upload/pdf-ae/benefits_of_going_ahead-aid_effectiveness_agenda_en.pdf .

- Birdsall, N. , Claessens, S. , & Diwan, I. (2003). Policy selectivity forgone: Debt and donor behavior in Africa. World Bank Economic Review , 17 , 409–435.

- Briggs, R. (2014). Aiding and abetting: Project aid and ethnic politics in Kenya. World Development 64 (12), 194–205.

- Bush, G. W. (2002). Presidents Bush, Chirac announce recent increases in aid at conference on financing for development. UN press release from the International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey, Mexico 2002. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2002/dev2388.doc.htm .

- Carsten, P. , & Blanchard, B. (2014). China to establish $40 billion Silk Road infrastructure fund. Reuters . November 8. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/08/us-chinadiplomacy-idUSKBN0IS0BQ20141108 .

- Collier, P. , & Hoeffler, A. (2007). Unintended consequences: Does aid promote arms races? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics , 69 , 1–27.

- Davies, P. (2010). A review of the roles and activities of new development partners (CFP Working Paper Series 4). Washington, DC: World Bank, Concessional Finance and Global Partnerships Vice Presidency.

- Del Biondo, K. (2014). The EU, the US and partnership in development cooperation: Bridging the gap? (CDDRL Working Paper). Retrieved from http://fsi.stanford.edu/publication/eu-us-and-partnership-development-cooperation-bridging-gap .

- Desai, A. , & Vreeland, J. (2014). What the new bank of BRICS is all about. Washington Post . Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/07/17/what-the-new-bank-of-brics-is-all-about/?utm_term=.acb925118d49 .

- Department for International Development, United Kingdom . (2001). What we are doing to tackle world poverty: A quick guide to the Department for International Development. Leaflet. Retrived from http://www.dfid.gov.uk/aboutdfid/ .

- Dietrich, S. (2013). Bypass or engage? Explaining donor delivery tactics in aid allocation. International Studies Quarterly , 57 (4), 698–712.

- Diamond, L. (2008). The Spirit of Democracy: The Struggle to Build Free Societies Throughout the World . New York: Times Books.

- Dixon, C. (2015). The new BRICS bank: Challenging the international financial order? (Policy Paper No. 28, Global Policy Institute). The Global Policy Institute. Retrieved from the London Metropolitan University website. Retrieved from http://eprints.londonmet.ac.uk/343/1/GPI%20policy%20paper%20no.28.pdf .

- Dreher, A. , & Fuchs, A. (2011). Rogue aid? The determinants of China’s aid allocation. Research Paper. Retrieved from the Princeton University website. https://www.princeton.edu/politics/about/file-repository/public/Rogue-Aid-China-Aid-Allocation.pdf .

- Dreher, A. , Nunnenkamp, P. , & Thiele, R. (2011). Are “new” donors different? Comparing the allocation of bilateral aid between non-DAC and DAC donor countries. World Development 39 , 1950–1968.

- Dreher, A. , Sturm, J.-E. , & Vreeland, J. (2009). Development aid and international politics: Does membership on the UN Security Council influence World Bank decisions? Journal of Development Economics , 88 , 1–18.

- Duffield, M. , Macrae, J. , & Curtis, D. (2001). “Editorial: Politics and Humanitarian Aid.” Disasters , 25 (4), 269–274.

- The Economist . (2010). The China model: The Beijing consensus is to keep quiet, May 6. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/16059990 .

- Eichenauer, V. , & Knack, S. (2016). Poverty and policy selectivity of World Bank trust funds (Unpublished working paper). Retrieved from http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/md/awi/professuren/intwipol/selectivity_of_trust_fund_aid_eichenauer_knack.pdf .

- Fuchs, A. , & Vadlamannati, K. C. (2012). The needy donor: An empirical analysis of India’s aid motives (Discussion Paper Series No. 0532). Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg, Germany.

- The Guardian . (May 25, 2011). The rebirth of Russian foreign aid . Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2011/may/25/russia-foreign-aid-report-influence-image .

- Headey, D. (2008). Geopolitics and the effect of foreign aid on economic growth, 1970–2001. Journal of International Development , 20 (2), 161–180.

- Herring, R. & Esman, M. (2001). Projects and policies, politics and ethnicities. In M. Esman & R. Herring (Eds.), Carrots, sticks, and ethnic conflict: Rethinking development assistance . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hynes, W. , & Trzeciak-Duval, A. (2015). The donor that came in from the cold: OECD–Russian engagement on development cooperation. International Organisations Research Journal , 10 (1), 31–55. Retrieved from https://iorj.hse.ru/data/2015/12/07/1095012459/The%20Donor%20That%20Came%20In%20from%20the%20Cold.pdf .

- Independent Evaluation Group . (2011). An evaluation of the World Bank’s trust fund portfolio: Trust fund support for development . Washington, DC: Independent Evaluation Group.

- Kaja, A. , & Werker, E. (2010). Corporate governance at the World Bank and the dilemma of global governance. World Bank Economic Review , 24 , 171–198.

- Kilby, C. , & Dreher, A. (2010). The impact of aid on growth revisited: Do donor motives matter? Economics Letters , 107 , 338–340.

- Kisangani, E. , & Pickering, J. (2015). Soldiers and development aid: Military intervention and foreign aid flows. Journal of Peace Research , 52 , 215–227.

- Kjøllesdal, K. , & Welle-Strand, A. (2010). Foreign aid strategies: China taking over? Asian Social Science , 6 (10), 3–13.

- Kuziemko, I. , & Werker, E. (2006). How much is a seat on the Security Council worth? Foreign aid and bribery at the United Nations. Journal of Political Economy , 114 , 905–930.

- Kwon, G. (1998). Retests on the theory of collective action: The Olson and Zeckhauser model and its elaboration. Economics and Politics , 10 (1), 37–62.

- Lancaster, C. (2007). Foreign aid: Diplomacy, development, domestic politics . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Library of Congress . (2015). Comparative analysis: Regulation of foreign aid in selected countries . Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/law/help/foreign-aid/regulation-of-foreign-aid.pdf .

- Licht, A. (2010). Coming into money: The impact of foreign aid on leader survival. Journal of Conflict Resolution , 54 (1), 58–87.

- Lumsdaine, D. (1993). Moral vision in international politics: The foreign aid regime, 1949–1989 . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mawdsley, E. (2012). From recipients to donors: Emerging powers and the changing development landscape . London: Zed.

- McGillivray, M. , & Morrissey, O. (2004). Fiscal effects of aid. In T. Addison & A. Roe (Eds.), Fiscal policy for development: Poverty, reconstruction and growth , Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Montgomery, J. (1962). The politics of foreign aid: American experiences in Southeast Asia . New York: Praeger.

- Morrison, K. M. (2012). What can we learn about the “resource curse” from foreign aid? World Bank Research Observer , 27 (1), 52–73.

- Mwase, M. (2011). Determinants of development financing flows from Brazil, Russia, India, and China to low-income countries (IMF Working Paper No. 11/255) . International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

- Nunnenkamp, P. , & Thiele, R. (2006). Targeting aid to the needy and deserving: Nothing but promises? World Economy , 29 (9), 1177–1201.

- OECD . Official development assistance—definition and coverage. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/officialdevelopmentassistancedefinitionandcoverage.htm .

- OECD . International Development Statistics online CRS Aid Activities dataset. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1 .

- OECD . QWIDS: Query Wizard for Development Statistics. Statistical tool of the OECD. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/qwids/ .

- Palmer, G. , & Morgan, T. C. (2006). A theory of foreign policy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Pehnelt, G. (2007). The political economy of China’s aid policy in Africa (Jena Economic Research Paper No. 051) . University of Jena, Germany.

- Radelet, S. (2006). A primer on foreign aid (Working Paper no. 92) . Center for Global Development, Washington, DC.

- Reinsberg, B. , Michaelowa, K. , & Eichenauer, V. Z. (2015). The rise of multi-bi aid and the proliferation of trust funds. In B. Mak Arvin & B. Lew (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of foreign aid . Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar.

- Riddell, R. (2014). Does foreign aid really work? (Background paper to keynote address to the Australasian Aid and International Development Workshop, Canberra, February 2014). Retrieved from http://devpolicy.org/2014-Australasian-Aid-and-International-Development-Policy-Workshop/Roger-Riddell-Background-Paper.pdf .

- Rouis, M. (2010). Arab development assistance: Four decades of cooperation (MENA Knowledge and Learning Quick Notes Series No. 28) . World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

- Round, J. I. , & Odedokun, M. (2004). Aid effort and its determinants. International Review of Economics and Finance , 13 , 293–309.

- Ruttan, V. (1996). United States development assistance policy: The domestic politics of foreign economic aid . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Tarnoff, C. , & Lawson, M. (2016). Foreign aid: An introduction to U.S. programs and policy (Congressional Research Service Report) . Retrieved from http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/R40213.pdf .

- Thompson, A. , & Verdier, D. (2014). Multilateralism, bilateralism, and regime design. International Studies Quarterly , 58 (1), 15–28.

- van der Veen, M. (2011). Ideas, interests and foreign aid . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Villanger, E. (2007). Arab foreign aid: Disbursement patterns, aid policies and motives. Forum for Development Studies , 34 , 223–256.

- Woods, N. (2008). Whose aid? Whose influence? China, emerging donors and the silent revolution in development assistance. International Affairs , 84 , 1205–1221.

1. The recipient of humanitarian and emergency aid is obligated to disburse the donor’s aid in an unbiased, neutral manner. “Humanitarian assistance,” in the words of Duffield et al. ( 2001 ), “has always been a highly political activity” (p. 269). Humanitarian aid has been used to alter conflicts and transform regimes, thus it reflects the foreign policy preferences of donors.

2. Earmarking is when the donor designates its assistance to be used for a particular purpose. The recipient can use foreign aid that is not earmarked for any purpose it desires.

3. The administration’s sentiment was reiterated by James Wolfensohn, the World Bank president (1995–2005), on February 16, 2004, in a speech at the conference “Making Globalization Work for All.”

4. The donor’s desire for oversight and management is not necessarily an unreasonable requirement. Foreign aid is most efficient in democratic countries with good governance, respect for the rule of law, a vibrant private sector, and strong institutions with a competent regulatory system. However, countries in the most need of aid are also the countries short on these same characteristics. Poor countries are often typified as corrupt, lacking accountability, or anocratic or authoritarian governments.

5. The Bank has two major lending agencies. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) is a branch of the Bank that lends money at market rates to middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries that display principles of good governance but have only sporadic access to private market capital. The International Development Association (IDA) provides loans (credits) and grants to the poorest countries at concessional rates. IDA loans provide money for poverty reduction and human development projects such as primary education, health services, and water and sanitation facilities.

6. The EU as an organization is the 29th DAC member.

7. Conditionalities refer to donors’ demands that the recipient undertake specific structural or systemic level changes, such as adopting economic liberalization policies or demanding more-democratic political procedures. Conditionalities encourage aid recipients to act in accord with the donor’s ideological preferences.

8. China began its foreign aid programs in 1950 with funds provided to North Korea. Later, in 1956, China extended its aid to non-Communist countries. Since that time, China’s aid programs have expanded in size and scope.

9. A reliance on project assistance will not completely solve the problem of fungibility since recipient governments can still skew the projects towards higher income groups.

Related Articles

- The Political Economy of Aid Conditionality

- Terrorism and Foreign Policy

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 10 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Character limit 500 /500

Influence and support for foreign aid: Evidence from the United States and China

- Published: 22 December 2023

Cite this article

- Austin Strange ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0878-7920 1

446 Accesses

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

When do members of the public support outgoing foreign aid? Existing research often focuses on individual and sociotropic sources of support based on economic, ideological, and emotional considerations. This article examines a potentially under-appreciated source of attitudes toward outgoing aid: foreign policy influence for one’s country. I argue that observers can make intuitive associations between different types of aid and different influence outcomes, and that the prospect of influence will generally increase support for outgoing aid. To test these claims, I conduct parallel survey experiments in the two largest donor and lender countries, the United States and China. I find that an aid project’s mode of delivery and degree of visibility affect its perceived value for influence-seeking, and that respondents understand and generally support the use of aid for influence. While direct aid to governments does not appear to increase support, project visibility does, and support is particularly high for visible aid provided directly to host country governments. The findings contribute to existing international relations and political economy research on aid and public opinion, international influence, and Chinese development finance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The power of the “weak” and international organizations

The impact of public opinion on voting and policymaking

Does Political Trust Matter? A Meta-analysis on the Consequences of Trust

Data availability.

Replication data and code are available on the website of the Review of International Organizations .

See https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-rebranding-united-states- foreign-assistance-advance-american-influence/ .

Milner ( 2006 ) shows that concern about domestic public opinion is an important reason why governments opt to contribute substantial multilateral aid even though doing so relinquishes control relative to providing aid bilaterally. Others argue that public opinion toward aid only sometimes affects actual aid allocation (e.g. Otter , 2003 .

Though, governments with relatively strong domestic support bases for aid giving, such as the U.K., may be able to protect aid budgets during economic downturns (Paxton & Knack, 2012 ).

As a recent example, in 2018 Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs began a domestic promotional campaign featuring an “ODA-man” anime character to bolster popular support for its overseas development assistance amid rising domestic demographic and economic pressures (Lindgren, 2020 ).

Public foreign policy preferences are shaped by political ideology, partisanship, as well as a host of individual-level attributes. Attitudes are also mediated by framing by the media and cue taking from elites (Zaller, 1992 ; Baum & Potter, 2008 ; Berinsky, 2009 ; Baum & Groeling, 2009 ).

Relatedly, constituents may support aid to the extent it increases their own economic welfare or reflects humanitarian values they support (Milner & Tingley, 2011 ; Heinrich, 2013 ).

Such perceptions may depend on respondents’ education levels (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2006 , 2010 ), in-group and out-group dynamics (Mansfield & Mutz, 2009 ), information on and comprehension of policies (Bearce & Tuxhorn, 2017 ), and other individual characteristics such as gender (Mansfield et al., 2015 ).

A diverse set of economic, political, and security interests motivate donor governments’ provision of development finance (e.g. Maizels and Nissanke , 1984 ; Meernik et al. , 1998 ; Burnside and Dollar , 2000 ; Katada , 2001 ; Milner and Tingley , 2010 ).

Soft power is usually defined as governments’ ability to advance their interests via attraction rather than coercion (Nye Jr, 2004 ). Favorable foreign public opinion is a common measure in international relations for soft power (e.g., Nye Jr , 2004 ; Goldsmith and Horiuchi , 2012 ; Rose , 2016 ).

Not doing so can be costly. For instance, popular anti-American sentiment abroad serves as a symbolic resource for mobilizers in other countries to affect policy change locally and internationally (Schatz, 2021 ).

Earlier studies consider how project-specific features, such as sector (e.g. economic or military) and financing type (e.g. grant or loan), affect the strategic utility of projects for both donors and recipients (e.g. Poe and Meernik , 1995 ; Dube and Naidu , 2015 ; Bermeo , 2016 ; Dreher et al. , 2018 ). Several other studies examine how variation in donor identity produces different popular reactions (Findley et al., 2017a , b ; Cha, 2020 ; Blair & Roessler, 2021 ).

Some exceptions exist. For instance, Dietrich et al. ( 2019 ) examine different levels of project branding, and Milner et al. ( 2016 ) investigate attitudinal effects caused by different project funder identities.

A sizeable literature in political science conceptualizes influence. One classic definition is “a relation among actors in which one actor induces other actors to act in some way they would not otherwise act” (Dahl , 1973 , 40). This literature suggests that states’ ability to translate raw power into political influence takes on various forms (Lukes, 1974 ; Nye Jr, 2004 ; Gaventa, 1982 ; Barnett & Duvall, 2005 ).

Combinations of non-governmental actors such as NGOs, INGOs, and commercial contractors implement a growing share of development finance projects (Dietrich, 2013 ).

High-visibility projects, in addition to their conspicuous physical presence relative to low-visibility projects, also tend to receive more publicity, particularly around key milestones such as a project’s announcement, commencement, or completion ceremonies (e.g. Menga , 2015 ).

National leaders similarly often possess political incentives to pursue domestically-financed infrastructure and other visible development projects (Mani & Mukand, 2007 ; Harding, 2015 ; Lei & Zhou, 2022 ).

Alternatively, opportunistic opposition politicians can exploit negative sentiment toward visible aid projects (or their proponents) for domestic political gain (O’Brien-Udry, 2020 ).

See https://stats.oecd.org/ .

The surveys and embedded experiments were not pre-registered. All outcome questions included in the surveys are discussed in the manuscript and reported in Appendix 2 . The online appendix is available on the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

Lucid was acquired by the Cint Group. See https://www.cint.com/blog/lucid-and-the-trade-desk-power- advertisers-brand-impact .

It was placed in the fifth of six short question blocks prior to treatment. This follows suggestions to place attention checks shortly before treatment since attentiveness can vary while taking a survey (Kane et al., 2023 ). It asked respondents “To verify that you are paying attention, please select the ‘somewhat disagree’ response option.”

In the power analysis, the minimum effect of interest was .5, the standard deviation was 1.5, and the significance level was .01, inputs that were informed by other recent experimental studies I have conducted in order to achieve 80% power. Power was calculated for direct tests of differences in means between treatment groups. This analysis suggested that each treatment group should include about 211 respondents.

In Appendix 3 , Figures 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , and 9 plot treatment group balance for a set of pre-treatment covariates. Tables 2 and 3 further examine balance across treatment groups for the American and Chinese samples.

Moreover, as reflected in Appendix 5 (for example, Tables 9 , 10 , 11 , and 12 ), neither age nor other covariates for which the samples are unrepresentative appear strongly associated with perceptions of aid’s influence functions or outcomes. In the American sample, age is negatively associated with perceptions of influence functions while it is positively associated with them in the China sample. The results for other covariates–such as gender, education, and income–are generally not significant.

See https://foreignassistance.gov/ .

https://www.foreignassistance.gov/cd/kenya/2017/disbursements/0. Disbursement data is not publicly available for Chinese development finance.

The survey administered online to Chinese respondents initially used a seven-point scale to measure the same questions, and the results herein are transformed to five-point scale in order to make apples-to-apples comparisons about effect magnitudes. The substantive results are unchanged when using the original scale.

Base covariates include respondent age, gender, level of education (whether one has a college degree), income (based on an 11- and 14-tiered scale of income ranges for the US and China, respectively), and political ideology (US only; coded as 1 if a respondent identifies as conservative along a seven-point numerical spectrum). In addition to the covariates included in these regressions, the surveys also captured additional pre-treatment factors such as measures of nationalism, support for democracy, and foreign policy ideology. Including these covariates does not change the results.

Again, results here are presented in terms of raw five-point scales.

As this study examines multiple outcomes to probe potential mechanisms, I also compute Bonferroni-corrected p-values for each hypothesis test. The significance of the main results holds and the differences in means remain statistically significant at more stringent thresholds (e.g. .01).

Though it is also unclear the extent to which American respondents were familiar with bypass aid prior to the survey treatment.

These questions also serve as implicit post-treatment manipulation checks. For example, respondents treated with a visible project should report higher level of agreement that the project will be highly visible.

Non-governmental actors such as international NGOs also prioritize project visibility among donor and host country audiences to attract financing and improve their public reputation (Phillips, 2019 ).

Ahlquist, J. S., Clayton, A. B., & Levi, M. (2014). Provoking Preferences: Unionization, Trade Policy, and the ILWU Puzzle. International Organization, 68 (1), 33–75.

Aldrich, J. H., Gelpi, C., Feaver, P., Reifler, J., & Sharp, K. T. (2006). Foreign Policy and the Electoral Connection. Annual Review of Political Science, 9 , 477–502.

Aldrich, J. H., Sullivan, J. L., & Borgida, E. (1989). Foreign Affairs and Issue Voting: Do Presidential Candidates ‘Waltz Before a Blind Audience?’. American Political Science Review, 83 (1), 123–141.

Allan, B., Vucetic, S., & Hopf, T. (2018). The Distribution of Identity and the Future of International Order: China’s Hegemonic Prospects. International Organization, 72 (4), 839–869.

Allendoerfer, M. G. (2017). Who Cares About Human Rights? Public Opinion About Human Rights Foreign Policy. Journal of Human Rights, 16 (4), 428–451.

Alrababa’h, A., Myrick, R., & Webb, I. (2020). Do Donor Motives Matter? Investigating Perceptions of Foreign Aid in the Conflict in Donbas. International Studies Quarterly, 64 (3), 748–757.

Baker, A. (2015). Race, Paternalism, and Foreign Aid: Evidence from US Public Opinion. American Political Science Review, 109 (1), 93–109.

Baldwin, K., & Winters, M. S. (2020). How Do Different Forms of Foreign Aid Affect Government Legitimacy? Evidence from an Informational Experiment in Uganda. Studies in Comparative International Development, 55 (2), 160–183.

Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in International Politics. International Organization, 59 (01), 39–75.

Baum, M. A., & Groeling, T. (2009). Shot by the Messenger: Partisan Cues and Public Opinion Regarding National Security and War. Political Behavior, 31 (2), 157–186.

Baum, M. A., & Potter, P. B. K. (2008). The Relationships Between Mass Media, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis. Annual Review of Political Science, 11 , 39–65.

Bayram, A. B. (2017). Aiding Strangers: Generalized Trust and the Moral Basis of Public Support for Foreign Development Aid. Foreign Policy Analysis, 13 (1), 133–153.

Bayram, A. B., & Holmes, M. (2020). Feeling their Pain: Affective Empathy and Public Preferences for Foreign Development Aid. European Journal of International Relations, 26 (3), 820–850.

Bayram, A. B., & Thomson, C. P. (2022). Ignoring the Messenger? Limits of Populist Rhetoric on Public Support for Foreign Development Aid. International Studies Quarterly, 66 (1), sqab041.

Bearce, D. H., & Tuxhorn, K.-L. (2017). When are Monetary Policy Preferences Egocentric? Evidence from American Surveys and an Experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 61 (1), 178–193.

Bechtel, M. M., Hainmueller, J., & Margalit, Y. (2014). Preferences for International Redistribution: the Divide Over the Eurozone Bailouts. American Journal of Political Science, 58 (4), 835–856.

Berinsky, A. J. (2009). In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F., & Sances, M. W. (2014). Separating the Shirkers from the Workers? Making Sure Respondents Pay Attention on Self-Administered Surveys. American Journal of Political Science, 58 (3), 739–753.

Berman, E., Shapiro, J. N., & Felter, J. H. (2011). Can Hearts and Minds be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq. Journal of Political Economy, 119 (4), 766–819.

Bermeo, S. B. (2016). Aid is not Oil: Donor Utility, Heterogeneous Aid, and the Aid-Democratization Relationship. International Organization, 70 (1), 1–32.

Blair, R. A., & Roessler, P. (2021). Foreign Aid and State Legitimacy Evidence on Chinese and US Aid to Africa from Surveys, Survey Experiments, and Behavioral Games. World Politics, 73 (2), 315–357.

Blair, R. A., Marty, R., & Roessler, P. (2022). Foreign Aid and Soft Power: Great Power Competition in Africa in the Early Twenty-First Century. British Journal of Political Science , 53 (2), 1355–1376.

Brautigam, D. (2009). The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Briggs, R. C. (2012). Electrifying the Base? Aid and Incumbent Advantage in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 50 (4), 603–624.

Brown, S. (2018). All About that Base? Branding and the Domestic Politics of Canadian Foreign Aid. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 24 (2), 145–164.

Brutger, R., Kertzer, J. D., Renshon, J., Tingley, D., & Weiss, C. M. (2020). Abstraction and Detail in Experimental Design. Working Paper. https://bit.ly/3juYJ0A .

Bueno de Mesquita, B. B., & Smith, A. (2007). Foreign Aid and Policy Concessions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51 (2), 251–284.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2009). A Political Economy of Aid. International Organization, 63 (2), 309–340.

Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, Policies, and Growth. American Economic Review, 90 (4), 847–868.