As we transition our order fulfillment and warehousing to W. W. Norton, select titles may temporarily appear as out of stock. We appreciate your patience.

On The Site

The Growth of Presidential Power

May 17, 2016 | yalepress | American History , Political Science

Benjamin Ginsberg—

For most of the nineteenth century, the presidency was a weak institution. In unusual circumstances, a Jefferson, a Jackson, or a Lincoln might exercise extraordinary power, but most presidents held little influence over the congressional barons or provincial chieftains who actually steered the government. The president’s job was to execute policy, rarely to make it. Policy making was the responsibility of legislators, particularly the leaders of the House and Senate.

Today, the presidency has become the dominant force in national policy formation, not all domestic policy springs from the White House but none is made without the president’s involvement. And when it comes to foreign policy and, particularly security policy, there can be little doubt about presidential primacy. Of course, Congress retains the constitutional power to declare war, but the power has not been exercised in sixty-five years. During this period American military forces have been engaged in numerous conflicts all over the world—at the behest of the president.

How did this transformation come about? To some, the study of the presidency is chiefly the study of personality and leadership in an attempt to distinguish between the attributes and conduct of strong and weak presidents or great, near-great and not-so-great presidents. Richard Neustadt, an influential presidential scholar, epitomized this focus on leadership styles and personality when he declared in 1960 that presidential power was the “power to persuade.” In other words, the power of the presidency was derived from the charisma of the president. Some scholars pushed this personalistic approach even further by engaging in psychoanalytic studies of presidents to determine which personality attributes seemed to be associated with presidential success. James David Barber’s well-known book, The Presidential Character is an exemplar of this school of thought.

The personal characteristics of presidents, though not unimportant, do not seem to offer an entirely satisfactory basis for explaining the transformation in the role of the president that has taken place in recent years. After all, while the power to persuade and other leadership abilities wax and wane with successive presidents, the power of the presidency has increased inexorably, perhaps growing more rapidly under the Roosevelts and Reagans and less so under the Fillmores and Carters of American politics but growing nonetheless. The president is, indeed, a person but the presidency is an office embedded in an institutional and constitutional structure and in an historical setting that limits some possibilities and encourages others. As Steven Skowronek has shown, leadership styles that are effective in one political era may be irrelevant or counterproductive in another.

Even presidential character and style are institutionally conditioned. Presidents today are generally more aggressive and ambitious than their predecessors because of an institutional change–a nominating process that tends to select for these characteristics by awarding the presidency to the survivor of years of harsh political struggles. And, as to the power to persuade, this formula was already beginning to be out of date in 1960 when it was introduced. The 1947 National Security Act had already vastly increased the president’s institutional power to command . Presidents were already becoming more imperial and less dependent upon the fine art of persuasion.

Accordingly, understanding the presidency requires what is generally called a historical-institutionalist approach. This perspective does not ignore leadership but, nevertheless, emphasizes history and institutions as the keys to understanding political phenomena. Presidential history is a guide to understanding the ways in which past events and experiences shape current perspectives and frame the possibilities open to presidents. Institutional rules, particularly the Constitution, help set the parameters for decision making and collective action.

Obviously, talented and ambitious presidents have pushed the boundaries of the office adding new powers that were seldom surrendered by their successors. But, what made this tactic possible was the inherent constitutional imbalance between the executive and Congress. Presidential power has grown less because of the leadership styles of particular presidents, and more because the Constitution puts Congress at an institutional disadvantage and provides the president with an institutional edge.

For example, presidents derive power from their execution of the laws. Decisions made by the Congress are executed by the president while presidents execute their own decisions. The result is an asymmetric relationship between presidential and congressional power. Whatever Congress does empowers the president; presidential actions, on the other hand, often weaken Congress. If it wishes to accomplish any goal, Congress must delegate power to the executive. Sometimes Congress accompanies its delegation of power with explicit standards and guidelines; sometimes it does not. In either eventuality, over the long term, a lmost any program launched by the Congress empowers the president and the executive branch, more generally, whose funding and authority must be increased to execute the law. In effect, every time Congress legislates it empowers the executive to do something, thereby contributing, albeit inadvertently, to the onward march of executive power.

As this example suggests, understanding America’s presidency requires us to do more than assess the relative merits of the presidents. It requires us to look carefully at the institution, its Constitutional place, and its history. The framers of the Constitution thought Congress would be the most important branch of government but the institutional structure they devised led to the gradual and inexorable growth of presidential power.

From Presidential Government by Benjamin Ginsberg , published by Yale University Press in 2016. Reproduced by permission.

Benjamin Ginsberg is the David Bernstein Professor of Political Science at Johns Hopkins University and chair of the Hopkins Center for Advanced Governmental Studies. He is the co-author of American Government: Power and Purpose, among other titles. He lives in Potomac, MD.

Further Reading:

Recent Posts

- The Petit Network

- Surely but Slowly: NATO Adapts to Strategic Competition

- The How and Why of Ukrainian Resilience and Courage

- What’s Happening to America’s Farms?

- Daily Life in Ancient Babylonia: Insights from the Temple of Ishtar

- Celebrating Women in Translation

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact W.W. Norton to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Notice for Canadian Customers

Due to temporary changes in our shipping process, we cannot fulfill orders to Canada through our website from August 12th to September 30th, 2024.

In the meantime, you can find our titles at the following retailers:

- Barnes & Noble

- Powell’s

- Seminary Co-op

We apologize for the inconvenience and appreciate your understanding.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, module 8: the presidency and executive power.

Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of the national government, headed by a single President. Article II outlines the method for electing the President, the scope of the President’s powers and duties, and the process of removing one from office. The President’s primary responsibility is to carry out the executive branch’s core function—namely, enforcing the nation’s laws. From the debates over how to structure the Presidency at the Constitutional Convention to modern debates over executive orders, this module will explore the important role of the President in our constitutional system.

Download all materials for this module as a PDF

Learning Objectives

- Discuss Article II of the Constitution and outline the requirements to be president, the election process, and the President’s primary powers and duties.

- Examine the origins of the Presidency and describe the Founders’ vision for the nation’s chief executive.

- Describe how the President’s role in our constitutional system has changed over time.

- Review the role of the Supreme Court and Congress in checking the President.

- Define what an executive order is, understand the roots of the President’s authority to issue executive orders, and study the role of executive orders in our government over time.

- Analyze competing constitutional visions of the Presidency over time.

8.1 Activity: Jobs of the President

- Student Instructions

- Teacher Notes

Purpose Article II “vest[s]” the “executive Power . . . of the United States” in a single president. It sets out the details for how we elect a president (namely, through the Electoral College) and how we might remove one from office (namely, through the impeachment and removal process). It also lists some of the president’s core powers and responsibilities. In this activity, you will explore the role of the president in our constitutional system.

Process Read the first line of Article II of the Constitution.

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

Think about executive power and participate in a class discussion facilitated by your teacher. Answer the following questions:

- What reactions do you have to the opening text of Article II? What do you think it means?

- What is “the executive Power?”

- This text tells us that the Founding generation created a single chief executive—the president. Why do you think the founders decided to place the executive power in the hands of a single person rather than a committee? What are the benefits of a single chief executive? What are the potential downsides?

- What is the role/job of the executive branch? Who else is part of the executive branch?

After discussing the first line of Article II with your class, brainstorm a current list of roles/jobs for the president. Record them and share with your classmates.

Review the Info Brief: Presidential Roles document for a comprehensive list.

Launch Provide students with a summary of the three branches of government. Within the national government, the executive branch is responsible for enforcing the laws. We commonly think of the president as the most powerful elected office in all of the world. Yet, the Constitution actually grants far fewer explicit powers to the president in Article II than it does to the Congress in Article I.

Give students time to read the first line of Article II.

Over the course of the week, ask students to try to match some of the key jobs of the president with what is spelled out in the Constitution.

Note: The 22nd Amendment limits the president to two terms in office. This is an example of a norm established by George Washington, held over time, violated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and then written into the Constitution. This is a great example to share with students of how a presidential norm may be written into the Constitution.

Activity Synthesis Ask students to discuss recent presidents and the roles they took on during their terms in office.

Activity Extension (optional) Now that students have a better understanding of the roles/jobs of the president, ask them to find a news article that demonstrates one or more roles of the president.

You can also ask students to speak to at least two adults and two peers outside of class, ask them the following questions, and write down their responses.

- What is the job of the president?

- What is the job of the executive branch?

8.1 Info Brief: Presidential Roles

8.2 activity: how does the presidency work.

Purpose In this activity, you will continue to explore the presidential jobs that are spelled out by the Constitution.

Process Review the text of Article II and the Interactive Constitution essays on Article II - The Executive Branch to help complete the Activity Guide: How does the Presidency Work? worksheet.

Review the following sections in the Constitution and the Interactive Constitution Common Essays:

- Text of the Constitution

- Common Interpretation

Compare your worksheet to the list you created as a class in the previous activity. Be prepared to discuss the similarities and differences as a class.

Launch Give students time to identify from memory as many roles/jobs of the president as they can remember from the previous activity. Compare that list to the list of roles/jobs that the adults and peers they asked identified.

Direct students to the text of Article II and the Interactive Constitution essays on Article II - The Executive Branch . Build a list of powers and duties for the president. Then, compare the crowdsourced list with the list developed from the primary and scholarly sources (the Constitution’s text and the Constitution essays).

Review the following sections in the Constitution :

Activity Synthesis When the comparison is complete, students could build a “Job Posting Advertisement” for a presidential candidate. Have students share ads with their classmates for review and discussion.

Activity Extension (optional) Review the resumes/background of several former presidents. Do you notice any patterns among the presidents? Does anyone stand out as having a unique background?

8.2 Activity Guide: How does the Presidency Work?

8.3 video activity: the presidency.

Purpose In this activity, you will view a video on the presidency and what the Constitution says about it.

Process Watch the following video about the presidency.

Then, complete the Video Reflection: The Presidency worksheet.

Identify any areas that are unclear to you or where you would like further explanation. Be prepared to discuss your answers in a group and to ask your teacher any remaining questions.

Launch Give students time to watch the video and take notes to support their notetaking skills.

Activity Synthesis Have students share their notes with a classmate and then review as a class.

Activity Extension (optional) Now that students have a better understanding of the presidency, ask them to identify what informal qualifications a president should have to be successful.

8.3 Video Reflection: The Presidency

8.4 activity: electoral college.

Purpose The delegates engaged in many debates over the presidency. One key debate involved the issue of how to elect the president. Today, many democratic nations elect their executives by direct popular vote. But we don’t. Instead, we use a system known as the “Electoral College.”

In this activity, you will read two sources to understand the founders’ debates over how to elect a president and their vision for the Electoral College. You will also reflect on the Electoral College now versus back when it was created.

- Info Brief: Electoral College

- NCC Scholar Exchange: The Electoral College

- Interactive Constitution Essay on the Electoral College

- Review the Info Brief: Key Debate Notes and examine the key debates around electing the president and other compromises among delegates that led to the Electoral College.

- Be prepared to discuss what you have read and viewed.

Launch Give students time to read the briefing sheet on the Electoral College and watch this short video. Review the key readings and debates and then examine the ideas and compromises as a group.

Activity Synthesis Have students share their thoughts about the proposals for how to elect a president and discuss positive and negative aspects of each. Ask students if they think the Electoral College, as it functions today, should be eliminated, changed, or stay the same.

Activity Extension (optional) Have students run for president and then have the rest of the class divided into the states to vote for their preferred candidate, replicating the Electoral College. Have each candidate select (or select for them) a campaign manager. The campaign manager's job is to build a strategy for targeting which states they think will be most useful to gain the electoral votes needed. Have the campaign teams visit only five groups of students (replicating scarcity of time and money on the campaign trail), making strategy a key component in securing victory. Have students vote by state groups and individually to examine who wins the popular vote and who wins the Electoral College.

8.4 Info Brief: Electoral College

8.4 info brief: key debate notes, 8.5 activity: test of presidential power.

Purpose There are still many ongoing debates over presidential power. When it comes to presidential power, the core constitutional question often comes down to this: Can the president do that? Over time, the Supreme Court has provided some guidance on how to analyze this important question.

In this activity, you will examine a major test of presidential power, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952) , also known as “ The Steel Seizure Case .”

Process Begin by reading excerpts from Primary Source: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952) and reviewing your notes from Activity 8.3 and reference your notes from the Info Brief: Methods of Constitutional Interpretation from module one. If you would like to watch the video again, starting at timestamp 12:25.

This landmark case took place during the Korean War. Steel workers were going on strike and President Truman responded by seizing the steel mills. He argued that a steel strike was a threat to national security because the Army needed steel to conduct the war. Therefore, he had the constitutional authority to act on his own—in other words, without explicit congressional approval—under his Article II commander in chief power.

After reviewing the primary source and video, complete the Case Brief: Test of Presidential Power worksheet.

Launch Give students time to read excerpts from Primary Source: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), review your notes from the earlier video, and answer the questions provided.

Activity Synthesis Have students share their responses to the questions and discuss as appropriate. Ask students how the presidency today compares to the founders’ vision.

Activity Extension (optional) Have students review other court cases related to presidential power.

- United States v. Nixon

- Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.

- Morrison v. Olson

- Zivotofsky v. Kerry

8.5 Primary Source: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952)

8.5 info brief: methods of constitutional interpretation, 8.5 case brief: tests of presidential power, 8.6 activity: analyzing executive orders.

Purpose One of the key debates over presidential power today involves the president’s use of executive orders. Defenders of presidential power argue that executive orders are central to the president’s core responsibilities of overseeing the executive branch and enforcing laws already passed by Congress. Critics of presidential power often argue that presidents (of both parties) use executive orders to stretch their powers—using them to command executive-branch officials to promote policies that they can’t get Congress to enact into law. In this activity, you will examine executive orders and how they have evolved over time.

Process In your group, review the following resources:

- Executive Orders Data

- Info Brief: Executive Orders

- Interactive Constitution Article II, Section 3 by William Marshall

Record your answer to the following questions and prepare to discuss.

- What is an executive order?

- Where does the president get her authority to issue executive orders?

- Which president used executive orders the most? The least?

- Who are the three that used them the least?

- Has the use of executive orders changed over time? Can you chart the numbers to see a pattern?

- Are there any eras where you see a boost in executive orders? Why do you think that would be the case? What do you know about that time period?

- How have executive orders changed the role/job of the president? What are some of the benefits of executive orders? What are some of the dangers?

Then, review Activity Guide: Quotes on Visions of Presidential Power . Try to guess which quote belongs to which key historical figure. As a class, compare the different viewpoints on presidential power.

Launch Give students time to review executive orders resources and answer the questions. Three sources to review are as follows:

Activity Synthesis Have students record their answer to the following questions and review as full class.

Ask students to summarize the information from the lesson in three to five sentences.

Activity Extension (optional) When it comes to presidential power, the constitutional question often comes down to this: Can the president do that?

Discuss the following examples with your class.

- Can her administration issue a sweeping regulation to regulate air pollution?

- What about one to require everyone in the nation to wear a mask? Or to stay at home?

- Can she send American troops to another country to overthrow that dictator?

Review a news item about executive orders today and see what leading questions are being posed on the balance of executive powers.

8.6 Info Brief: Executive Orders

8.6 activity guide: quotes on visions of presidential power, 8.7 test your knowledge.

Congratulations for completing the activities in this module! Now it’s time to apply what you have learned about the basic ideas and concepts covered.

Complete the questions in the following quiz to test your knowledge.

This activity will help students determine their overall understanding of module concepts. It is recommended that questions are completed electronically so immediate feedback is provided, but a downloadable copy of the questions (with answer key) is also available.

8.7 Interactive Knowledge Check: The Executive Branch and Electoral College

8.7 printable knowledge check: the executive branch and electoral college, previous module, module 7: the legislative branch: how congress works, next module, module 9: the judicial system and current cases.

Article III of the Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the national government, which is responsible for interpreting the laws. At the highest level, the judicial branch is led by the U.S. Supreme Court, which consists of nine Justices. In the federal system, the lower courts consist of the district courts and the courts of appeals. Federal courts—including the Supreme Court—exercise the power of judicial review. This power gives courts the authority to rule on the constitutionality of laws passed (and actions taken) by the elected branches. The Cons...

Go to the Next Module

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Powers of the President of the United States

Us constitution.

The power of the United States President comes from the United States Constitution:

Image courtesy National Archives website

Enumerated Powers From the US Constitution

Under Article II of the United States Constitution. The President:

- Has the power to approve or veto bills and resolutions passed by Congress

- Through the Treasury Department, has the power to write checks pursuant to appropriation laws.

- Pursuant to the Oath of Office, will preserve, protect, and defend the Consitution of the United States.

- Serves as Commander-in-Chief of the United States military, and militia when called to service.

- Is authorized to require principle officers of executive departments to provide written opinions upon the duties of their offices

- Has the power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in the cases of inpeachment.

- Has the power to make treaties, with the advise and consent of Congress.

- Has the power to nominate ambassadors and other officials with the advise and consent of Congress.

- Has the power to fill vacancies that happen when the Senate is in recess that will expire at the end of the Senate's next session.

- Shall periodically advise Congress on the state of the union and give Congress recommendations that are thought necessary and expedient.

- Has the power to convene one or both houses of Congress during extraordinary occasions, and when Congress cannot agree to adjourn has the power to adjourn them when he thinks the time is proper.

- Has the duty to receive ambassadors and other public ministers.

- Has the duty to see that the laws are faithfully executed.

- Has the power to commission the officers of the United States.

- View transcript of the United States Constitution from the National Archives

- Next: Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 10, 2023 11:11 AM

- URL: https://libguides.law.widener.edu/potus-power

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 The Powers of the Presidency

Learning objectives.

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How is the presidency personalized?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to the president?

- How can Congress and the judiciary limit the president’s powers?

- How is the presidency organized?

- What is the bureaucratizing of the presidency?

The presidency is seen as the heart of the political system. It is personalized in the president as advocate of the national interest, chief agenda-setter, and chief legislator (Tulis, 1988). Scholars evaluate presidents according to such abilities as “public communication,” “organizational capacity,” “political skill,” “policy vision,” and “cognitive skill” (Greenstein, 2009). The media too personalize the office and push the ideal of the bold, decisive, active, public-minded president who altruistically governs the country (Smith, 2009).

Two big summer movie hits, Independence Day (1996) and Air Force One (1997) are typical: ex-soldier presidents use physical rather than legal powers against (respectively) aliens and Russian terrorists. The president’s tie comes off and heroism comes out, aided by fighter planes and machine guns. The television hit series The West Wing recycled, with a bit more realism, the image of a patriarchal president boldly putting principle ahead of expedience (Parry-Giles & Parry-Giles, 2006).

Figure 13.1

Whether swaggering protagonists of hit movies Independence Day and Air Force One in the 1990s or more down-to-earth heroes of the hit television series The West Wing , presidents are commonly portrayed in the media as bold, decisive, and principled.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Presidents are even presented as redeemers (Sachleben & Yenerall, 2004; Smith, 2009). There are exceptions: presidents depicted as “sleazeballs” or “simpletons” (Larson, 2000).

Enduring Image

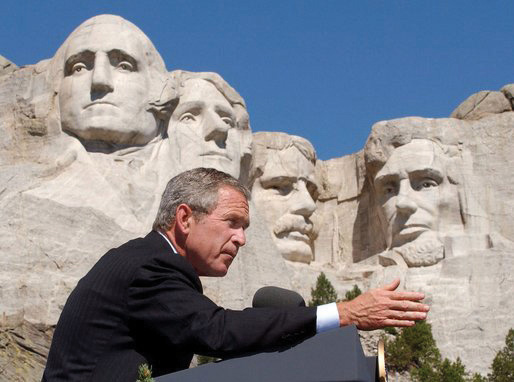

Mount Rushmore

Carved into the granite rock of South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore , seven thousand feet above sea level, are the faces of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Sculpted between 1927 and 1941, this awe-inspiring monument achieved even greater worldwide celebrity as the setting for the hero and heroine to overcome the bad guys at the climax of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic and ever-popular film North by Northwest (1959).

This national monument did not start out devoted to American presidents. It was initially proposed to acknowledge regional heroes: General Custer, Buffalo Bill, the explorers Lewis and Clark. The sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, successfully argued that “a nation’s memorial should…have a serenity, a nobility, a power that reflects the gods who inspired them and suggests the gods they have become” (Dean, 1949).

The Mount Rushmore monument is an enduring image of the American presidency by celebrating the greatness of four American presidents. The successors to Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt do their part by trying to associate themselves with the office’s magnificence and project an image of consensus rather than conflict, sometimes by giving speeches at the monument itself. A George W. Bush event placed the presidential podium at such an angle that the television camera could not help but put the incumbent in the same frame as his glorious predecessors.

George W. Bush Speaking in Front of Mt. Rushmore

The enduring image of Mount Rushmore highlights and exaggerates the importance of presidents as the decision makers in the American political system. It elevates the president over the presidency, the occupant over the office. All depends on the greatness of the individual president—which means that the enduring image often contrasts the divinity of past presidents against the fallibility of the current incumbent.

News depictions of the White House also focus on the person of the president. They portray a “single executive image” with visibility no other political participant can boast. Presidents usually get positive coverage during crises foreign or domestic. The news media depict them speaking for and symbolically embodying the nation: giving a State of the Union address, welcoming foreign leaders, traveling abroad, representing the United States at an international conference. Ceremonial events produce laudatory coverage even during intense political controversy.

The media are fascinated with the personality and style of individual presidents. They attempt to pin them down. Sometimes, the analyses are contradictory. In one best-selling book, Bob Woodward depicted President George W. Bush as, in the words of reviewer Michiko Kakutani, “a judicious, resolute leader…firmly in control of the ship of state.” In a subsequent book, Woodward described Bush as “passive, impatient, sophomoric and intellectual incurious…given to an almost religious certainty that makes him disinclined to rethink or re-evaluate decisions” (Kakutani, 2006; Bush at War, 2002).

This media focus tells only part of the story. [1] The president’s independence and ability to act are constrained in several ways, most notably by the Constitution.

The Presidency in the Constitution

Article II of the Constitution outlines the office of president. Specific powers are few; almost all are exercised in conjunction with other branches of the federal government.

Table 13.1 Bases for Presidential Powers in the Constitution

| Article I, Section 7, Paragraph 2 | Veto |

| Pocket veto | |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 1 | “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President…” |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 7 | Specific presidential oath of office stated explicitly (as is not the case with other offices) |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Commander in chief of armed forces and state militias |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Can require opinions of departmental secretaries |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 2 | Make treaties |

| appoint ambassadors, executive officers, judges | |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 3 | Recess appointments |

| Article II, Section 3 | State of the Union message and recommendation of legislative measures to Congress |

| Convene special sessions of Congress | |

| Receive ambassadors and other ministers | |

| “He shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” |

Presidents exercise only one power that cannot be limited by other branches: the pardon. So controversial decisions like President Gerald Ford’s pardon of his predecessor Richard Nixon for “crimes he committed or may have committed” or President Jimmy Carter’s blanket amnesty to all who avoided the draft during the Vietnam War could not have been overturned.

Presidents have more powers and responsibilities in foreign and defense policy than in domestic affairs. They are the commanders in chief of the armed forces; they decide how (and increasingly when) to wage war. Presidents have the power to make treaties to be approved by the Senate; the president is America’s chief diplomat. As head of state, the president speaks for the nation to other world leaders and receives ambassadors.

The Constituion

Read the entire Constituion at https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution .

The Constitution directs presidents to be part of the legislative process. In the annual State of the Union address, presidents point out problems and recommend legislation to Congress. Presidents can convene special sessions of Congress, possibly to “jump-start” discussion of their proposals. Presidents can veto a bill passed by Congress, returning it with written objections. Congress can then override the veto. Finally, the Constitution instructs presidents to be in charge of the executive branch. Along with naming judges, presidents appoint ambassadors and executive officers. These appointments require Senate confirmation. If Congress is not in session, presidents can make temporary appointments known as recess appointments without Senate confirmation, good until the end of the next session of Congress.

The Constitution’s phrase “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” gives the president the job to oversee the implementation of laws. Thus presidents are empowered to issue executive orders to interpret and carry out legislation. They supervise other officers of the executive branch and can require them to justify their actions.

Congressional Limitations on Presidential Power

Almost all presidential powers rely on what Congress does (or does not do). Presidential executive orders implement the law but Congress can overrule such orders by changing the law. And many presidential powers are delegated powers that Congress has accorded presidents to exercise on its behalf—and that it can cut back or rescind.

Congress can challenge presidential powers single-handedly. One way is to amend the Constitution. The Twenty-Second Amendment was enacted in the wake of the only president to serve more than two terms, the powerful Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). Presidents now may serve no more than two terms. The last presidents to serve eight years, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, quickly became “lame ducks” after their reelection and lost momentum toward the ends of their second terms, when attention switched to contests over their successors.

Impeachment gives Congress “sole power” to remove presidents (among others) from office. [2] It works in two stages. The House decides whether or not to accuse the president of wrongdoing. If a simple majority in the House votes to impeach the president, the Senate acts as jury, House members are prosecutors, and the chief justice presides. A two-thirds vote by the Senate is necessary for conviction, the punishment for which is removal and disqualification from office.

Prior to the 1970s, presidential impeachment was deemed the founders’ “rusted blunderbuss that will probably never be taken in hand again” (Labowitz, 1978). Only one president (Andrew Johnson in 1868) had been impeached—over policy disagreements with Congress on the Reconstruction of the South after the Civil War. Johnson avoided removal by a single senator’s vote.

Presidential Impeachment

Read about the impeachment trial of President Johnson at http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Senate_Votes_on_a_Presidential_Impeachment.htm .

Read about the impeachment trial of President Clinton at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impeachment_of_Bill_Clinton .

Since the 1970s, the blunderbuss has been dusted off. A bipartisan majority of the House Judiciary Committee recommended the impeachment of President Nixon in 1974. Nixon surely would have been impeached and convicted had he not resigned first. President Clinton was impeached by the House in 1998, though acquitted by the Senate in 1999, for perjury and obstruction of justice in the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

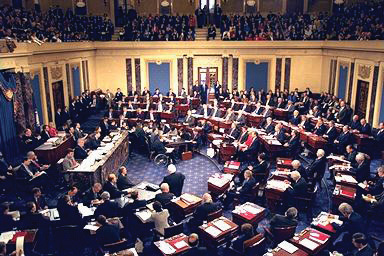

Figure 13.2

Bill Clinton was only the second US president to be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors” and stand trial in the Senate. Not surprisingly, in this day of huge media attention to court proceedings, the presidential impeachment trial was covered live by television and became endless fodder for twenty-four-hour-news channels. Chief Justice William Rehnquist presided over the trial. The House “managers” (i.e., prosecutors) of the case are on the left, the president’s lawyers on the right.

Much of the public finds impeachment a standard part of the political system. For example, a June 2005 Zogby poll found that 42 percent of the public agreed with the statement “If President Bush did not tell the truth about his reasons for going to war with Iraq, Congress should consider holding him accountable through impeachment” (Polling Report, 2005).

Impeachment can be a threat to presidents who chafe at congressional opposition or restrictions. All three impeached presidents had been accused by members of Congress of abuse of power well before allegations of law-breaking. Impeachment is handy because it refers only vaguely to official misconduct: “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

From Congress’s perspective, impeachment can work. Nixon resigned because he knew he would be removed from office. Even presidential acquittals help Congress out. Impeachment forced Johnson to pledge good behavior and thus “succeeded in its primary goal: to safeguard Reconstruction from presidential obstruction” (Benedict, 1973). Clinton had to go out of his way to assuage congressional Democrats, who had been far from content with a number of his initiatives; by the time the impeachment trial was concluded, the president was an all-but-lame duck.

Judicial Limitations on Presidential Power

Presidents claim inherent powers not explicitly stated but that are intrinsic to the office or implied by the language of the Constitution. They rely on three key phrases. First, in contrast to Article I’s detailed powers of Congress, Article II states that “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President.” Second, the presidential oath of office is spelled out, implying a special guardianship of the Constitution. Third, the job of ensuring that “the Laws be faithfully executed” can denote a duty to protect the country and political system as a whole.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court can and does rule on whether presidents have inherent powers. Its rulings have both expanded and limited presidential power. For instance, the justices concluded in 1936 that the president, the embodiment of the United States outside its borders, can act on its behalf in foreign policy.

But the court usually looks to congressional action (or inaction) to define when a president can invoke inherent powers. In 1952, President Harry Truman claimed inherent emergency powers during the Korean War. Facing a steel strike he said would interrupt defense production, Truman ordered his secretary of commerce to seize the major steel mills and keep production going. The Supreme Court rejected this move: “the President’s power, if any, to issue the order must stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.” [3]

The Vice Presidency

Only two positions in the presidency are elected: the president and vice president. With ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the latter office may be filled by the president, who appoints a vice president subject to majority votes in both the House and the Senate. This process was used twice in the 1970s. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned amid allegations of corruption; President Nixon named House Minority Leader Gerald Ford to the post. When Nixon resigned during the Watergate scandal, Ford became president—the only person to hold the office without an election—and named former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The vice president’s sole duties in the Constitution are to preside over the Senate and cast tie-breaking votes, and to be ready to assume the presidency in the event of a vacancy or disability. Eight of the forty-three presidents had been vice presidents who succeeded a dead president (four times from assassinations). Otherwise, vice presidents have few official tasks. The first vice president, John Adams, told the Senate, “I am Vice President. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” More earthily, FDR’s first vice president, John Nance Garner, called the office “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

In recent years, vice presidents are more publicly visible and have taken on more tasks and responsibilities. Ford and Rockefeller began this trend in the 1970s, demanding enhanced day-to-day responsibilities and staff as conditions for taking the job. Vice presidents now have a West Wing office, are given prominent assignments, and receive distinct funds for a staff under their control parallel to the president’s staff (Light, 1984).

Arguably the most powerful occupant of the office ever was Dick Cheney. This former doctoral candidate in political science (at the University of Wisconsin) had been a White House chief of staff, member of Congress, and cabinet secretary. He possessed an unrivaled knowledge of the power relations within government and of how to accumulate and exercise power. As George W. Bush’s vice president, he had access to every cabinet and subcabinet meeting he wanted to attend, chaired the board charged with reviewing the budget, took on important issues (security, energy, economy), ran task forces, was involved in nominations and appointments, and lobbied Congress (Gellman & Becker, 2007).

Organizing the Presidency

The presidency is organized around two offices. They enhance but also constrain the president’s power.

The Executive Office of the President

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) is an umbrella organization encompassing all presidential staff agencies. Most offices in the EOP, such as the Office of the Vice President, the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget, are established by law; some positions require Senate confirmation.

Learn about the EOP at http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop .

Inside the EOP is the White House Office (WHO) . It contains the president’s personal staff of assistants and advisors; most are exempt from Congress’s purview. Though presidents have a free hand with the personnel and structure of the WHO, its organization has been the same for decades. Starting with Nixon in 1969, each president has named a chief of staff to head and supervise the White House staff, a press secretary to interact with the news media, and a director of communication to oversee the White House message. The national security advisor is well placed to become the most powerful architect of foreign policy, rivaling or surpassing the secretary of state. New offices, such as President Bush’s creation of an office for faith-based initiatives, are rare; such positions get placed on top of or alongside old arrangements.

Even activities of a highly informal role such as the first lady , the president’s spouse, are standardized. It is no longer enough for them to host White House social events. They are brought out to travel and campaign. They are presidents’ intimate confidantes, have staffers of their own, and advocate popular policies (e.g., Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification, Nancy Reagan’s antidrug crusade, and Barbara Bush’s literacy programs). Hillary Rodham Clinton faced controversy as first lady by defying expectations of being above the policy fray; she was appointed by her husband to head the task force to draft a legislative bill for a national health-care system. Clinton’s successor, Laura Bush, returned the first ladyship to a more social, less policy-minded role. Michelle Obama’s cause is healthy eating. She has gone beyond advocacy to having Walmart lower prices on the fruit and vegetables it sells and reducing the amount of fat, sugar, and salt in its foods.

Bureaucratizing the Presidency

The media and the public expect presidents to put their marks on the office and on history. But “the institution makes presidents as much if not more than presidents make the institution” (Ragsdale & Theis III, 1997; Burke, 2000).

The presidency became a complex institution starting with FDR, who was elected to four terms during the Great Depression and World War II. Prior to FDR, presidents’ staffs were small. As presidents took on responsibilities and jobs, often at Congress’s initiative, the presidency grew and expanded.

Not only is the presidency bigger since FDR, but the division of labor within an administration is far more complex. Fiction and nonfiction media depict generalist staffers reporting to the president, who makes the real decisions. But the WHO is now a miniature bureaucracy. The WHO’s first staff in 1939 consisted of eight generalists: three secretaries to the president, three administrative assistants, a personal secretary, an executive clerk. Since the 1980s, the WHO has consisted of around eighty staffers; almost all either have a substantive specialty (e.g., national security, women’s initiatives, environment, health policy) or emphasize specific activities (e.g., White House legal counsel, director of press advance, public liaison, legislative liaison, chief speechwriter, director of scheduling). The White House Office adds another organization for presidents to direct—or lose track of.

The large staff in the White House, and the Old Executive Office Building next door, is no guarantee of a president’s power. These staffers “make a great many decisions themselves, acting in the name of the president. In fact, the majority of White House decisions—all but the most crucial—are made by presidential assistants” (Kessel, 2001).

Most of these labor in anonymity unless they make impolitic remarks. For example, two of President Bush’s otherwise obscure chief economic advisors got into hot water, one for (accurately) predicting that the cost of war in Iraq might top $200 billion, another for praising the outsourcing of jobs (Andrews, 2004). Relatively few White House staffers—the chief of staff, the national security advisor, the press secretary—become household names in the news, and even they are quick to be quoted saying, “as the president has said” or “the president decided.” But often what presidents say or do is what staffers told or wrote for them to say or do (see Note 13.13 “Comparing Content” ).

Comparing Content

Days in the Life of the White House

On April 25, 2001, President George W. Bush was celebrating his first one hundred days in office. He sought to avoid the misstep of his father who ignored the media frame of the first one hundred days as the make-or-break period for a presidency and who thus seemed confused and aimless.

As part of this campaign, Bush invited Stephen Crowley, a New York Times photographer, to follow him and present, as Crowley wrote in his accompanying text, “an unusual behind-the-scenes view of how he conducts business” (Crowley, 2001). Naturally, the photos implied that the White House revolves completely around the president. At 6:45 a.m., “the White House came to life”—when a light came on in the president’s upstairs residence. The sole task shown for Bush’s personal assistant was peering through a peephole to monitor the president’s national security briefing. Crowley wrote “the workday ended 15 hours after it began,” after meetings, interviews, a stadium speech, and a fund-raiser.

We get a different understanding of how the White House works from following not the president but some other denizen of the West Wing around for a day or so. That is what filmmaker Theodore Bogosian did: he shadowed Clinton’s then press secretary Joe Lockhart for a few days in mid-2000 with a high-definition television camera. In the revealing one-hour video, The Press Secretary , activities of the White House are shown to revolve around Lockhart as much as Crowley’s photographic essay showed they did around Bush. Even with the hands-on Bill Clinton, the video raises questions about who works for whom. Lockhart is shown devising taglines, even policy with his associates in the press office. He instructs the president what to say as much as the other way around. He confides to the camera he is nervous about letting Clinton speak off-the-cuff.

Of course, the White House does not revolve around the person of the press secretary. Neither does it revolve entirely around the person of the president. Both are lone individuals out of many who collectively make up the institution known as the presidency.

Key Takeaways

The entertainment and news media personalize the presidency, depicting the president as the dynamic center of the political system. The Constitution foresaw the presidency as an energetic office with one person in charge. Yet the Constitution gave the office and its incumbent few powers, most of which can be countered by other branches of government. The presidency is bureaucratically organized and includes agencies, offices, and staff. They are often beyond a president’s direct control.

- How do the media personalize the presidency?

- How can the president check the power of Congress? How can Congress limit the influence of the president?

- How is the executive branch organized? How is the way the executive branch operates different from the way it is portrayed in the media?

Andrews, E. L., “Economics Adviser Learns the Principles of Politics,” New York Times , February 26, 2004, C4.

Benedict, M. L., The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (New York: Norton, 1973), 139.

Burke, J. P., The Institutional Presidency , 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002).

Crowley, S., “And on the 96th Day…,” New York Times , April 29, 2001, Week in Review, 3.

Dean, R. J., Living Granite (New York: Viking Press, 1949), 18.

Gellman, B. and Jo Becker, “Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency,” Washington Post , June 24, 2007, A1.

Greenstein, F. I., The Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama , 3rd ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Kakutani, M., “A Portrait of the President as the Victim of His Own Certitude,” review of State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III, by Bob Woodward, New York Times , September 30, 2006, A15.

Kessel, J. H., Presidents, the Presidency, and the Political Environment (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2001), 2.

Labowitz, J. R., Presidential Impeachment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), 91.

Larson, S. G., “Political Cynicism and Its Contradictions in the Public, News, and Entertainment,” in It’s Show Time! Media, Politics, and Popular Culture , ed. David A. Schultz (New York: Peter Lang, 2000), 101–116.

Light, P. C., Vice-Presidential Power: Advice and Influence in the White House (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984).

Parry-Giles, T. and Shawn J. Parry-Giles, The Prime-Time Presidency: The West Wing and U.S. Nationalism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006).

Polling Report, http://www.pollingreport.com/bush.htm , accessed July 7, 2005.

Ragsdale, L. and John J. Theis III, “The Institutionalization of the American Presidency, 1924–92,” American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 4 (October 1997): 1280–1318 at 1316.

Sachleben, M. and Kevan M. Yenerall, Seeing the Bigger Picture: Understanding Politics through Film and Television (New York: Peter Lang, 2004), chap. 4.

Smith, J., The Presidents We Imagine (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009).

Tulis, J. K., The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

- On the contrast of “single executive image” and the “plural executive reality,” see Lyn Ragsdale, Presidential Politics (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993). ↵

- The language in the Constitution comes from Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, and Article I, Section 3, Clause 7. This section draws from Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (New York: Norton, 1973); John R. Labowitz, Presidential Impeachment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978); and Michael J. Gerhardt, The Federal Impeachment Process: A Constitutional and Historical Analysis , 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). ↵

- Respectively, United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp, 299 US 304 (1936); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer, 343 US 579 (1952). ↵

American Government and Politics in the Information Age Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Mischiefs of Faction

How powerful is the US president?

A look at other constitutions explains why American executives are so ineffectual.

by Zachary Elkins

Which parts of the US Constitution have aged least well? In prior posts in this series, Jennifer Victor nominates slavery and suffrage and Seth Masket the electoral college . But it is also the case that our treasured “checks and balances” have become, well, unbalanced. Consider that we seem incapable of agreeing upon legislation that addresses the pressing issues of the day — everything from immigration to our crumbling infrastructure to health care. And forget about climate change.

Some of this dysfunction may be the result of persistent polarization and tribal “partyism.” But a primary cause is constitutional and rooted in the anemic lawmaking powers that our 1787 document grants to the president. This is only obvious once we compare the presidency to executives in other constitutional countries. It may seem strange to consider augmenting executive power during one of the most controversial administrations in US history, but now is exactly the time to evaluate the idea, when we can clearly understand the consequences.

One of the twists of fate from the founders’ summer project of 1787 is that they opted for a president over a prime minister. At some moments that summer, it looked like they might choose the latter. This fundamental difference between presidentialism and parliamentarism matters.

Prime ministers, as lead legislators, have power to set and implement the legislative agenda directly. US presidents can mostly just react to legislation through their veto power, though admittedly the threat of a veto could serve as a downstream constraint that legislators take into account upstream. This lack of initiation power was exhibited starkly last week when Senate Majority Leader McConnell informed the president that the Senate would not — contrary to the president’s tweet — be taking up comprehensive health care reform.

Most presidential systems have adapted the US model by explicitly allowing presidents to introduce legislation. Professors Terry Moe and William Howell have suggested a fix: fast-track privileges guaranteeing presidential proposals a vote in Congress.

Even in countries where presidents can initiate bills, their proposals are not as successful as are those of prime ministers. Consider some data collected by Sebastian Saiegh on the “batting average” of a large sample of executives over 30 years — that is, the percentage of executive-initiated legislative proposals that are ultimately enacted. As we might expect, the data shows that prime ministers have more success than do presidents. The US president, who cannot even come up to bat, is obviously not included in the analysis.

So, the US president has little direct power to affect legislation, at least initially. But what interests me is that the office also lacks many of the indirect legislative powers of presidents in other countries. We can think of indirect powers as providing “outside options” to legislation as well as threats/protections vis a vis the legislature; both sets of powers increase a president’s leverage in legislative bargaining.

Consider eight such powers. Outside options in other constitutions for executives include: 1. issuing legislative decrees; 2. calling a national referendum; 3. declaring a national emergency; and 4. proposing an amendment to the constitution.

Threats (or shields from threats) might include: 5. dissolving the legislature; 6. challenging the constitutionality of a law; 7. providing immunity for the executive from criminal prosecution; and 8. restricting legislative oversight.

And one could add other powers, such as the line-item veto.

The US president has none of these, at least constitutionally (which is critical). Other constitutions — for better or worse — include some or all of these. The chart below shows the sum of these eight powers for executives in presidential constitutions. The US score of zero, sitting lonely at the left side of the histogram, helps explain why our executives are not able to herd legislators in the direction of their agenda.

The US president’s anemic powers were evident during the Obama years. The shift to a Republican-controlled House in 2010 set in motion a perpetual standoff between Obama and Congress. One low-water mark may have been the brinkmanship over raising the debt ceiling during the summer of 2011. Each side needed the other’s approval to shape a budget bill and each, presumably, preferred an agreement to none at all.

As it happens, President Obama did have a constitutional outside option. Under one interpretation of the 14th Amendment (not President Obama’s, evidently), the president could have raised the debt ceiling unilaterally, to ensure the “validity of the public debt of the United States” ( 14th Amendment, Section 4 ). President Obama rejected this Constitutional option, which, according to Paul Krugman, amounted to a “systematic destruction of his own bargaining power.”

President Trump has a very different bargaining style. During the standoff over border wall funding, he has made aggressive use of his emergency powers. These powers, importantly, are not enshrined in the Constitution but rather in ordinary legislation, which renders them far less sacrosanct. It is not at all clear that the Supreme Court will find President Trump’s aggressive use of that statute to be consistent with his constitutional powers.

The emergency power example reminds us that our leadership over the years has tried to build a more muscular presidency outside of the Constitution. In addition to using statutory emergency powers, presidents have engaged in the dubious practice of “signing statements” that indicate their intent to honor only parts of legislation. The growth of extra-constitutional powers is what Arthur Schlessinger had in mind when he coined the phrase “imperial presidency” in 1973. Schlessinger worried that accumulating executive power outside of the constitution defined emperors as against presidents.

Other presidential countries have periodically revised the US model to constitutionalize many indirect legislative powers. Brazil, for example, along with the US and averages for presidential and parliamentary systems, has gradually built a strong set of presidential powers over legislation. It will be interesting to observe how President Bolsonaro wields such powers.

Which brings us to political considerations. Debates about constitutional prerogatives do not happen behind a veil of ignorance. Many constitutional drafters have in mind the next (or current) president. It didn’t take much for the Philadelphia drafters to imagine that George Washington, the archetypal consensus choice, would fill the office.

The reverence in which they held Washington makes it all the more ironic that they endowed the office so weakly. In our times, it is hard to imagine any legislator advocating for more executive power for their tribal opponent. Still, it may be that that is just what we need if we are to build and maintain bridges, update immigration laws, enact consensus legislation regarding guns, and solve problems in health care provision. Or we could continue to use our Congress to write bills to name post offices.

Most Popular

- The massive Social Security number breach is actually a good thing

- The difference between American and UK Love Is Blind

- Kamala Harris’s speech triggered a vintage Trump meltdown

- The staggering death toll of scientific lies

- This chart of ocean heat is terrifying

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Mischiefs of Faction

That’s good news for Brazilian democracy.

A good event for the upper tier of candidates, a bad one for Biden, and a forgettable one for the ones you’ve already forgotten.

We’re starting to see the direction of a committee dedicated to changing Capitol Hill.

But US evangelicals have been more loyal to Trump than Brazil’s evangelicals have been to President Bolsonaro, so this move may not work.

Democrats are trying to learn from 2016 and prevent the same problems in the nomination race.

For the second presidential cycle in a row, there’s a record-breaking number of candidates in the nominee race.

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

Presidential Essays

George Washington was born to Mary Ball and Augustine Washington on February 22, 1732. As the third son of a middling planter, George probably should have been relegated to a footnote in a history book. Instead, he became one of the greatest figures in American history.

A series of personal losses changed the course of George’s life. His father, Augustine, died when he was eleven years old, ending any hopes of higher education. Instead, Washington spent many of his formative years under the tutelage of Lawrence, his favorite older brother. He also learned the science of surveying and began a new career with the help of their neighbors, the wealthy and powerful Fairfax family. Lawrence’s death in 1752 again changed George’s plans. He leased Mount Vernon, a plantation in northern Virginia, from Lawrence’s widow and sought a military commission, just as Lawrence had done.

Washington served as the lieutenant colonel of the Virginia regiment and led several missions out west to the Ohio Valley. On his second mission west, he participated in the murder of French forces, including a reported ambassador. In retaliation, the French surrounded Washington’s forces at Fort Necessity and compelled an unequivocal surrender. Washington signed the articles of capitulation, not knowing that he was accepting full blame for an assassination. His mission marked the start of the Seven Years’ War.

Washington then joined General Edward Braddock’s official family as an aide-de-camp. In recognition of Washington’s extraordinary bravery during Braddock’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie appointed him as the commander of the Virginia Regiment. He served with distinction until the end of 1758.

In early 1759, George entered a new chapter in his life when he married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow, and won election to the Virginia House of Burgesses. George and Martha moved to Mount Vernon and embarked on an extensive expansion and renovation of the estate. Their life with her children from her previous marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, was loving and warm.

Washington’s position in the House of Burgesses took on additional importance as relations between the colonies and Great Britain deteriorated after the end of the Seven Years’ War. The British government had incurred enormous debts fighting across the globe and faced high military costs defending the new territories in North America that it had received in the peace settlement. To defray these expenses, the British Parliament passed a series of new taxation measures on its colonies, which were still much lower than those paid by citizens in England. But many colonists protested that they had already contributed once to the war effort and should not be forced to pay again, especially since they had no input in the legislative process.

Washington supported the protest measures in the House of Burgesses, and in 1774, he accepted appointment as a Virginia delegate to the First Continental Congress, where he voted for non-importation measures, such as abstaining from purchasing British goods. The following year, he returned to the Second Continental Congress after British regulars and local militia forces clashed in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. He approved Congress’s decision to create an army in June 1775 and was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.

For the next eight years, Washington led the army, only leaving headquarters to respond to Congress’s summons. He lost more battles than he won and at times had to hold the army together with sheer will, but ultimately emerged victorious in 1783 when the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War.

Washington’s success as a commander derived from three factors. First, he never challenged civilian authority. The new nation deeply distrusted military power, and his intentional self-subordination kept him in command. Second, the soldiers and officers adored him. The soldiers’ devotion to their commander was so apparent that some congressmen rued that it was not the Continental Army, it was George Washington’s army. Finally, Washington understood that if the army survived, so too would the cause for independence. He did not have to beat the British Army, he just had to avoid complete destruction.

At the end of the war, Washington returned his commission to the Confederation Congress and resumed life as a private citizen in Virginia. In an age of dictators and despots, his voluntarily surrender of power rippled around the globe and solidified his legend. Unsurprisingly, when the state leaders began discussing government reform a few years later, they knew Washington’s participation was essential for success.

In 1786, the Virginia legislature nominated a slate of delegates to represent the state at the Constitutional Convention. Washington’s close friend, Governor Edmund Randolph, ensured that George’s name was included. In May 1787, Washington set out for Philadelphia, where he served as the president of the convention. Once the convention agreed to a draft constitution, he then worked behind the scenes to ensure ratification. Washington believed the new constitution would resolve many of the problems that had plagued the Confederation Congress, but he also knew that if the states ratified the constitution, he would once again be dragged back into public service.

On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth and requisite state to ratify the new Constitution of the United States, forcing each state to schedule elections for the new federal offices. Unsurprisingly, Washington was unanimously elected as the first president. He took the oath of office on April 30, 1789.

As the first president, Washington literally crafted the office from scratch, which was an accomplishment that cannot be overstated because every decision was an opportunity for failure. Instead, Washington set a model for restraint, prestige in office, and public service. As president, Washington also oversaw the establishment of the financial system, the restoration of the nation’s credit, the expansion of US territory (often at the expense of Native Americans), the negotiation of economic treaties with European empires, and the defense of executive authority over diplomatic and domestic affairs.

Washington set countless precedents, including the creation of the cabinet, executive privilege, state of the union addresses, and his retirement after two terms. On September 19, 1796, Washington published his Farewell Address announcing his retirement in a Philadelphia newspaper. He warned Americans to come together and reject partisan or foreign attempts to divide them, admonitions that retain their significance into the twenty-first century. He then willingly surrendered power once more.

When Washington left office, his contemporaries referred to him the father of the country. No other person could have held the Continental Army together for eight years, granted legitimacy to the Constitution Convention, or served as the first president. It is impossible to imagine the creation of the United States without him.

Yet, Washington’s life also embodies the complicated founding that shapes our society today. He owned hundreds of enslaved people and benefitted from their forced labor from the moment he was born to the day he died. His wealth, produced by slavery, made possible his decades of public service. Washington’s financial success, and that of the new nation, also depended on the violent seizure of extensive territory from Native American nations along the eastern seaboard to the Mississippi River. Washington’s life and service as the first president represents the irony contained in the nation’s founding. The United States was forged on the idea that “all men are created equal,” yet depended on the subjugation and exploitation of women and people of color.

On February 22, 1732, Mary Ball Washington gave birth to the first of her six children, a boy named George. George’s father, Augustine, had been married once before and had three older children from his previous marriage. Over the next several years, the large family moved a few times, before settling at Ferry Farm on the banks of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia.

When George was eleven, his life changed radically. His father died, and George’s older brothers inherited most of Augustine’s estate, including Little Hunting Creek Plantation, which later became Mount Vernon. George inherited one of the smaller estates and ten enslaved individuals who worked the farm.

Without a large inheritance, George relied on his family and connections to make his way in the world. Unlike his older brothers, he did not have the opportunity to study at a university. He spent his teenage years learning how to manage a plantation from his mother and mastering the science of surveying with the assistance of his neighbor, Colonel William Fairfax.

In 1751, George accompanied his favorite older brother, Lawrence, on a trip to Barbados. While in the Caribbean, George came down with smallpox. He survived and left the island with lifelong immunity, but the disease probably left him unable to father children and with a firsthand conviction about the dangers of the disease.

The trip to Barbados was also formative for Washington’s future. He toured the military structures on the island and was increasingly interested in a military career. Initially, George wanted to join the British Navy, and Lawrence promised to help secure him a position. Mary, George’s mother, had strong reservations about the physical abuse her son might receive in the navy and the limited possibilities for advancement. She was probably right, as life in the navy was often brutal and short-lived.

With his dreams of naval glory dashed, Washington looked west.

Early Career

By George’s seventeenth birthday, he received his first official commission to survey Culpeper County. He had learned the skills under the supervision of Colonel William Fairfax, his neighbor and one of the leading figures in Virginia. Just a few years later, Washington had completed almost 200 surveys of more than 60,000 acres.

In 1752, George’s older brother Lawrence died, and Washington appeared to lose interest in surveying as a profession and pursued a military career instead. In October 1753, he offered his services to Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia, who planned to send an emissary to meet with the French in the Ohio Valley. The governor accepted Washington’s offer, and he headed west. Over the next few months, Washington became convinced that the French were planning a large military force to attack the British. Eager to warn Dinwiddie, George left the protection of the expedition and made his way on foot with one guide for company. After nearly drowning, freezing, and starving, he arrived in Williamsburg on January 16, 1754.

For his daring service, Washington was promoted to lieutenant colonel and ordered to raise men for an upcoming mission to drive the French out of the Ohio Valley. On his way to the Monongahela River, Washington encountered a French scouting party and determined that they had to be stopped before they revealed his location. He met up with Tanacharison, a local Native American chief, and they made their way to a French camp at Jumonville Glen. According to Washington’s later retelling of the events, when Washington intended to accept the French surrender, the Native American forces attacked and scalped many French soldiers. During the attack, the French commander, Sieur de Jumonville, was killed.

After the attack, Washington hastily built a small defensive enclosure he named Fort Necessity. On July 3, 1754, French forces surrounded the fort, and by the end of the day, Washington asked for terms of surrender. The French allowed the British forces to leave the fort in return for admitting to the assassination of Jumonville, an official ambassador. The terms were written in French, which Washington could not read. Washington never accepted this explanation, insisting that the French forces were spies and that the terms were unclear. The attack marked the start of the Seven Years’ War.

After the debacle at Jumonville, Washington joined Brigadier General Edward Braddock’s official family as an aide-de-camp. He accompanied Braddock on his march out west to capture the French Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh). French and Native American forces attacked the British line, killing most of the British officers and inflicting horrific casualties during the Battle of Monongahela. Washington won acclaim and promotion for his courage under fire and his efforts to manage an unruly retreat. For the next several years, he served as commander of the Virginia colonial forces before returning his commission at the end of 1758.

Mount Vernon

After leaving the military, Washington had a new position, a new fiancé, and a new home that demanded his attention. He won election to the Virginia House of Burgesses and took his seat in February 1759—one month after his wedding to the wealthy widow Martha Custis. The marriage was advantageous for George’s prospects, but also appears to have developed into a love match, or an amiable partnership at the very least. They wrote and spoke of each other with affection and desired each other’s company.

After their wedding, George and Martha resided at his plantation, Mount Vernon, which he had inherited when Lawrence’s widow died in 1761. Washington had grand plans for his new endeavors as a plantation owner. Over the previous several years, he had purchased dozens of enslaved individuals, and Martha brought 84 of the 300 enslaved laborers she owned to Mount Vernon, which added more manpower for the house and fields. Washington planned to expand the land and the house and revolutionize the farming practices. He began by purchasing lands surrounding the original 3,000 acres of the Mount Vernon estate, starting in 1757. By the time of his death, he owned nearly 8,000 acres.

Washington also quadrupled the size of the original house, from a one-and-a-half story, four-room house, to a 11,000-square-foot mansion, and he updated all the finishings and furnishings. Martha’s wealth funded the improvements, and she likely contributed to the décor and design decisions.

As Washington expanded his home to reflect his elite status, he also reformed his farm’s operations. He was one of the earliest plantation owners to recognize that tobacco damaged the soil. Spurred on by the falling prices, Washington ordered his enslaved laborers to switch over to grains, and he experimented with the latest techniques of fertilization and crop rotation methods.