Hawthorne Effect: Definition, How It Works, and How to Avoid It

Ayesh Perera

B.A, MTS, Harvard University

Ayesh Perera, a Harvard graduate, has worked as a researcher in psychology and neuroscience under Dr. Kevin Majeres at Harvard Medical School.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- The Hawthorne effect refers to the increase in the performance of individuals who are noticed, watched, and paid attention to by researchers or supervisors.

- In 1958, Henry A. Landsberger coined the term ‘Hawthorne effect’ while evaluating a series of studies at a plant near Chicago, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works.

- The novelty effect, demand characteristics and feedback on performance may explain what is widely perceived as the Hawthorne effect.

- Although the possible implications of the Hawthorne effect remain relevant in many contexts, recent research findings challenge many of the original conclusions concerning the phenomenon.

The Hawthorne effect refers to a tendency in some individuals to alter their behavior in response to their awareness of being observed (Fox et al., 2007).

This phenomenon implies that when people become aware that they are subjects in an experiment, the attention they receive from the experimenters may cause them to change their conduct.

Hawthorne Studies

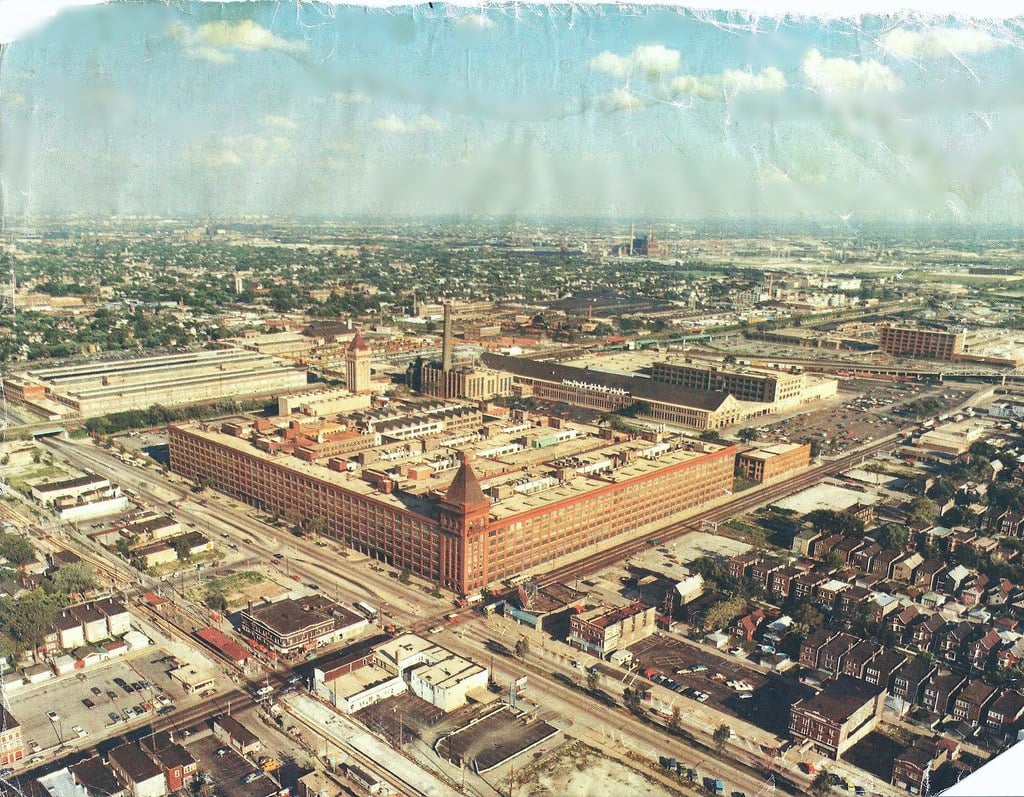

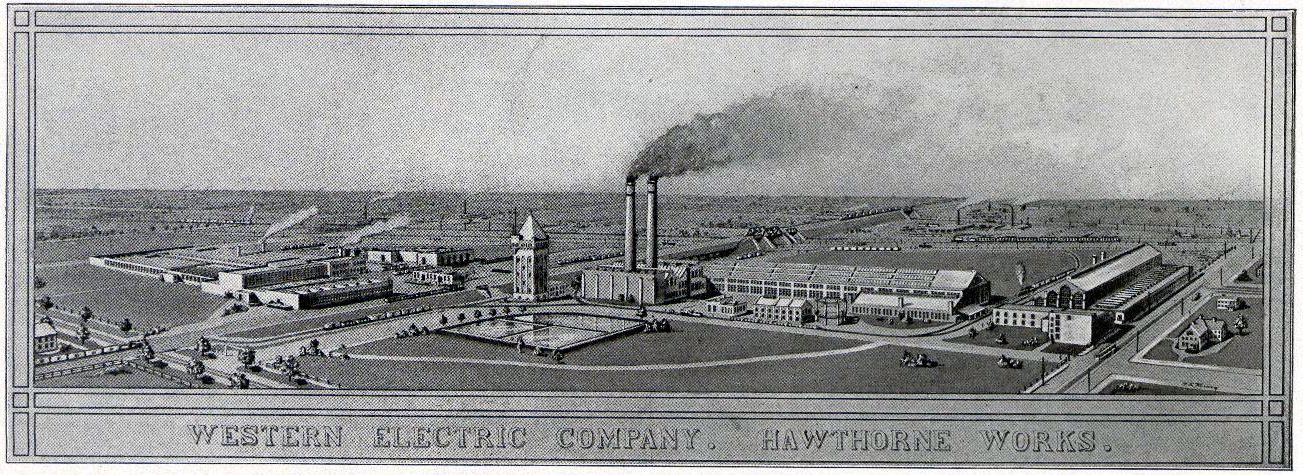

The Hawthorne effect is named after a set of studies conducted at Western Electric’s Hawthorne Plant in Cicero during the 1920s. The Scientists included in this research team were Elton Mayo (Psychologist), Roethlisberger and Whilehead (Sociologists), and William Dickson (company representative).

There are 4 separate experiments in Hawthorne Studies:

Illumination Experiments (1924-1927) Relay Assembly Test Room Experiments (1927-1932) Experiments in Interviewing Workers (1928- 1930) Bank Wiring Room Experiments (1931-1932)

The Hawthorne Experiments, conducted at Western Electric’s Hawthorne plant in the 1920s and 30s, fundamentally influenced management theories.

They highlighted the importance of psychological and social factors in workplace productivity, such as employee attention and group dynamics, leading to a more human-centric approach in management practices.

Illumination Experiment

The first and most influential of these studies is known as the “Illumination Experiment”, conducted between 1924 and 1927 (sponsored by the National Research Council).

The company had sought to ascertain whether there was a relationship between productivity and the work environments (e.g., the level of lighting in a factory).

During the first study, a group of workers who made electrical relays experienced several changes in lighting. Their performance was observed in response to the minutest alterations in illumination.

What the original researchers found was that any change in a variable, such as lighting levels, led to an improvement in productivity. This was true even when the change was negative, such as a return to poor lighting.

However, these gains in productivity disappeared when the attention faded (Roethlisberg & Dickson, 1939). The outcome implied that the increase in productivity was merely the result of a motivational effect on the company’s workers (Cox, 2000).

Their awareness of being observed had apparently led them to increase their output. It seemed that increased attention from supervisors could improve job performance.

Hawthorne Experiment by Elton Mayo

Relay assembly test room experiment.

Spurred by these initial findings, a series of experiments were conducted at the plant over the next eight years. From 1928 to 1932, Elton Mayo (1880–1949) and his colleagues began a series of studies examining changes in work structure (e.g., changes in rest periods, length of the working day, and other physical conditions.) in a group of five women.

The results of the Elton Mayo studies reinforced the initial findings of the illumination experiment. Freedman (1981, p. 49) summarizes the results of the next round of experiments as follows:

“Regardless of the conditions, whether there were more or fewer rest periods, longer or shorter workdays…the women worked harder and more efficiently.”

Analysis of the findings by Landsberger (1958) led to the term the Hawthorne effect , which describes the increase in the performance of individuals who are noticed, watched, and paid attention to by researchers or supervisors.

Bank Wiring Observation Room Study

In a separate study conducted between 1927 and 1932, six women working together to assemble telephone relays were observed (Harvard Business School, Historical Collections).

Following the secret measuring of their output for two weeks, the women were moved to a special experiment room. The experiment room, which they would occupy for the rest of the study, had a supervisor who discussed various changes to their work.

The subsequent alterations the women experienced included breaks varied in length and regularity, the provision (and the non-provision) of food, and changes to the length of the workday.

For the most part, changes to these variables (including returns to the original state) were accompanied by an increase in productivity.

The researchers concluded that the women’s awareness of being monitored, as well as the team spirit engendered by the close environment improved their productivity (Mayo, 1945).

Subsequently, a related study was conducted by W. Lloyd Warner and Elton Mayo, anthropologists from Harvard (Henslin, 2008).

They carried out their experiment on 14 men who assembled telephone switching equipment. The men were placed in a room along with a full-time observer who would record all that transpired. The workers were to be paid for their individual productivity.

However, the surprising outcome was a decrease in productivity. The researchers discovered that the men had become suspicious that an increase in productivity would lead the company to lower their base rate or find grounds to fire some of the workers.

Additional observation unveiled the existence of smaller cliques within the main group. Moreover, these cliques seemed to have their own rules for conduct and distinct means to enforce them.

The results of the study seemed to indicate that workers were likely to be influenced more by the social force of their peer groups than the incentives of their superiors.

This outcome was construed not necessarily as challenging the previous findings but as accounting for the potentially stronger social effect of peer groups.

Hawthorne Effect Examples

Managers in the workplace.

The studies discussed above reveal much about the dynamic relationship between productivity and observation.

On the one hand, letting employees know that they are being observed may engender a sense of accountability. Such accountability may, in turn, improve performance.

However, if employees perceive ulterior motives behind the observation, a different set of outcomes may ensue. If, for instance, employees reason that their increased productivity could harm their fellow workers or adversely impact their earnings eventually, they may not be actuated to improve their performance.

This suggests that while observation in the workplace may yield salutary gains, it must still account for other factors such as the camaraderie among the workers, the existent relationship between the management and the employees, and the compensation system.

A study that investigated the impact of awareness of experimentation on pupil performance (based on direct and indirect cues) revealed that the Hawthorne effect is either nonexistent in children between grades 3 and 9, was not evoked by the intended cues, or was not sufficiently strong to alter the results of the experiment (Bauernfeind & Olson, 1973).

However, if the Hawthorne effect were actually present in other educational contexts, such as in the observation of older students or teachers, it would have important implications.

For instance, if teachers were aware that they were being observed and evaluated via camera or an actual person sitting inside the class, it is not difficult to imagine how they might alter their approach.

Likewise, if older students were informed that their classroom participation would be observed, they might have more incentives to pay diligent attention to the lessons.

Alternative Explanations

Despite the possibility of the Hawthorne effect and its seeming impact on performance, alternative accounts cannot be discounted.

The Novelty Effect

The Novelty Effect denotes the tendency of human performance to show improvements in response to novel stimuli in the environment (Clark & Sugrue, 1988). Such improvements result not from any advances in learning or growth, but from a heightened interest in the new stimuli.

Demand Characteristics

Demand characteristics describe the phenomenon in which the subjects of an experiment would draw conclusions concerning the experiment’s objectives, and either subconsciously or consciously alter their behavior as a result (Orne, 2009). The intentions of the participant—which may range from striving to support the experimenter’s implicit agenda to attempting to utterly undermine the credibility of the study—would play a vital role herein.

Feedback on Performance

It is possible for regular evaluations by the experimenters to function as a scoreboard that enhances productivity. The mere fact that the workers are better acquainted with their performance may actuate them to increase their output.

Despite the seeming implications of the Hawthorne effect in a variety of contexts, recent reviews of the initial studies seem to challenge the original conclusions.

For instance, the data from the first experiment were long thought to have been destroyed. Rice (1982) notes that “the original [illumination] research data somehow disappeared.”

Gale (2004, p. 439) states that “these particular experiments were never written up, the original study reports were lost, and the only contemporary account of them derives from a few paragraphs in a trade journal.”

However, Steven Levitt and John List of the University of Chicago were able to uncover and evaluate these data (Levitt & List, 2011). They found that the supposedly notable patterns were entirely fictional despite the possible manifestations of the Hawthorne effect.

They proposed excess responsiveness to variations induced by the experimenter, relative to variations occurring naturally, as an alternative means to test for the Hawthorne effect.

Another study sought to determine whether the Hawthorne effect actually exists, and if so, under what conditions it does, and how large it could be (McCambridge, Witton & Elbourne, 2014).

Following the systemic review of the available evidence on the Harthorne effect, the researchers concluded that while research participation may indeed impact the behaviors being investigated, discovering more about its operation, its magnitude, and its mechanisms require further investigation.

How to Reduce the Hawthorne Effect

The credibility of experiments is essential to advances in any scientific discipline. However, when the results are significantly influenced by the mere fact that the subjects were observed, testing hypotheses becomes exceedingly difficult.

As such, several strategies may be employed to reduce the Hawthorne Effect.

Discarding the Initial Observations :

- Participants in studies often take time to acclimate themselves to their new environments.

- During this period, the alterations in performance may stem more from a temporary discomfort with the new environment than from an actual variable.

- Greater familiarity with the environment over time, however, would decrease the effect of this transition and reveal the raw effects of the variables whose impact the experimenters are observing.

Using Control Groups:

- When the subjects experiencing the intervention and those in the control group are treated in the same manner in an experiment, the Hawthorne effect would likely influence both groups equivalently.

- Under such circumstances, the impact of the intervention can be more readily identified and analyzed.

- Where ethically permissible, the concealment of information and covert data collection can be used to mitigate the Hawthorne effect.

- Observing the subjects without informing them, or conducting experiments covertly, often yield more reliable outcomes. The famous marshmallow experiment at Stanford University, which was conducted initially on 3 to 5-year-old children, is a striking example.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did the researchers, who identified the hawthorne effect, see as evidence that employee performance was influenced by something other than the physical work conditions.

The researchers of the Hawthorne Studies noticed that employee productivity increased not only in improved conditions (like better lighting), but also in unchanged or even worsened conditions.

They concluded that the mere fact of being observed and feeling valued (the so-called “Hawthorne Effect”) significantly impacted workers’ performance, independent from physical work conditions.

What is the Hawthorne effect in simple terms?

The Hawthorne Effect is when people change or improve their behavior because they know they’re being watched.

It’s named after a study at the Hawthorne Works factory, where researchers found that workers became more productive when they realized they were being observed, regardless of the actual working conditions.

Bauernfeind, R. H., & Olson, C. J. (1973). Is the Hawthorne effect in educational experiments a chimera ? The Phi Delta Kappan, 55 (4), 271-273.

Clark, R. E., & Sugrue, B. M. (1988). Research on instructional media 1978-88. In D. Ely (Ed.), Educational Media and Technology Yearbook, 1994. Volume 20. Libraries Unlimited, Inc., PO Box 6633, Englewood, CO 80155-6633.

Cox, E. (2001). Psychology for A-level . Oxford University Press.

Fox, N. S., Brennan, J. S., & Chasen, S. T. (2008). Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 141 (2), 111-114.

Gale, E.A.M. (2004). The Hawthorne studies – a fable for our times? Quarterly Journal of Medicine, (7) ,439-449.

Henslin, J. M., Possamai, A. M., Possamai-Inesedy, A. L., Marjoribanks, T., & Elder, K. (2015). Sociology: A down to earth approach . Pearson Higher Education AU.

Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne Revisited : Management and the Worker, Its Critics, and Developments in Human Relations in Industry.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3 (1), 224-38.

Mayo, E. (1945). The human problems of an industrial civilization . New York: The Macmillan Company.

McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67 (3), 267-277.

McCarney, R., Warner, J., Iliffe, S., Van Haselen, R., Griffin, M., & Fisher, P. (2007). The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7 (1), 1-8.

Rice, B. (1982). The Hawthorne defect: Persistence of a flawed theory. Psychology Today, 16 (2), 70-74.

Orne, M. T. (2009). Demand characteristics and the concept of quasi-controls. Artifacts in behavioral research: Robert Rosenthal and Ralph L. Rosnow’s classic books, 110 , 110-137.

Further Information

- Wickström, G., & Bendix, T. (2000). The” Hawthorne effect”—what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show?. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 363-367.

- Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1), 224-38.

- Oswald, D., Sherratt, F., & Smith, S. (2014). Handling the Hawthorne effect: The challenges surrounding a participant observer. Review of social studies, 1(1), 53-73.

- Bloombaum, M. (1983). The Hawthorne experiments: a critique and reanalysis of the first statistical interpretation by Franke and Kaul. Sociological Perspectives, 26(1), 71-88.

Overview of the Hawthorne Effect

The field of organizational behavior is built on a foundation of research and studies that aim to understand the complexities of human behavior within the workplace. One of the most influential studies in this field is the Hawthorne Studies, conducted at the Western Electric Hawthorne Works in Chicago between 1924 and 1932.

Led by a team of researchers from Harvard Business School , these studies revolutionized the understanding of human behavior in a work setting and continue to shape organizational behavior research today.

The Hawthorne Effect, named after the studies that uncovered it, refers to the phenomenon where individuals modify their behavior simply because they are being observed.

- 1 The Context of the Hawthorne Studies

- 2 The Initial Experiments and Findings

- 3 The Significance of the Hawthorne Studies

- 4 The Legacy of the Hawthorne Effect in Organizational Behavior

- 5.1.1 Benefits and Impact

- 5.1.2 Limitations

The Context of the Hawthorne Studies

The Hawthorne Studies were conducted by a team of researchers from Harvard Business School, including Elton Mayo, Fritz Roethlisberger, and William J. Dickson. Elton Mayo , considered the father of the Hawthorne Studies, played a crucial role in shaping the research and interpreting the findings.

The Hawthorne Studies were originally initiated to examine the relationship between lighting levels and worker productivity. The researchers believed that by increasing lighting levels, they could improve worker efficiency.

However, the results of the initial experiments surprised them. Not only did productivity increase when lighting was increased, but it also increased when lighting was decreased. This unexpected finding prompted further investigations into the psychological and social factors that influence worker motivation and performance.

The Initial Experiments and Findings

The initial experiments of the Hawthorne Studies focused on the relationship between lighting levels and worker productivity. The researchers divided the workers into two groups and manipulated the lighting conditions for each group. Surprisingly, both groups showed increased productivity regardless of whether the lighting was increased or decreased. This phenomenon became known as the “Hawthorne Effect” and led the researchers to delve deeper into the factors that influence worker behavior.

Further experiments were conducted to explore factors such as rest breaks, incentives, and supervisory styles. The researchers found that regardless of the specific changes made, productivity tended to increase. This led to the realization that it was not the specific changes themselves that influenced productivity, but rather the attention given to the workers and the social interactions within the workplace.

The Significance of the Hawthorne Studies

The Hawthorne Studies challenged traditional management theories that focused solely on the technical aspects of work. They demonstrated that the human element within organizations plays a crucial role in productivity and job satisfaction.

The studies highlighted the importance of worker attitudes, group dynamics, and social interactions in influencing employee performance. This shift in perspective paved the way for a greater emphasis on creating supportive and collaborative work environments that prioritize employee well-being and engagement.

The findings of the Hawthorne Studies also led to the development of new management practices. The researchers advocated for a more participative management style that encouraged open communication, employee involvement in decision-making, and a focus on developing positive relationships between managers and workers. These practices aimed to create a sense of belonging and foster a positive work culture, ultimately leading to improved performance and job satisfaction.

The Legacy of the Hawthorne Effect in Organizational Behavior

The Hawthorne Studies have left a lasting legacy in the field of organizational behavior. They shifted the focus from a purely technical approach to a more holistic understanding of employee behavior.

The studies highlighted the importance of considering the human element within organizations and recognizing the impact of social interactions and group dynamics on productivity and job satisfaction.

The Hawthorne Studies also paved the way for further research in the field, inspiring subsequent studies that explored topics such as leadership styles, employee motivation, and organizational culture .

Criticisms of the Hawthorne Studies

One criticism is that the studies were c onducted in a specific context – the Hawthorne Works factory – which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or settings.

Some argue that the Hawthorne Effect itself may have influenced the results , as the workers may have changed their behavior due to the awareness of being observed.

Another criticism is that the studies did not take into account external factors that could have influenced productivity, such as changes in technology or market conditions.

And critics argue that the studies focused too heavily on the social and psychological aspects of work , neglecting other important factors that contribute to productivity.

Quick Overview of the Hawthorne Effect

Human Relations Approach : Emphasized the importance of social relations and employee attitudes in the workplace.

Effect of Observation on Behavior : Known as the “Hawthorne Effect,” it suggests that workers modify their behavior in response to being observed.

Increased Productivity : Found that changes in physical work conditions (like lighting) temporarily increased productivity.

Social Factors in Work : Identified the significant role of social groups and norms in the workplace.

Employee Motivation : Highlighted non-economic factors like camaraderie and attention as motivators for workers.

Management Practices : Suggested that more attention to workers’ needs could improve worker satisfaction and productivity.

Benefits and Impact

Humanizes the Workplace : Shifted focus from strict task orientation to considering workers’ social needs and well-being.

Foundation for Modern HR Practices : Influenced the development of employee-centered management and human resource practices.

Importance of Social Dynamics : Emphasized the role of group dynamics, leadership, and communication in work efficiency.

Broader Understanding of Motivation : Contributed to understanding that motivation is not solely driven by pay or working conditions.

Limitations

Methodological Flaws : Critics point out flaws in experimental design, lack of proper controls, and subjective interpretations.

Exaggerated Effects : Some argue that the studies overemphasized the impact of social and psychological factors on productivity.

Overgeneralization : Critics believe that conclusions drawn from the studies were too broad and not universally applicable.

Potential Bias : The presence of researchers may have influenced worker behavior, questioning the validity of the results.

Key Takeaways

- The Hawthorne Studies have had a profound impact on our understanding of human behavior in the workplace.

- These studies revolutionized management theories by highlighting the significance of worker attitudes, group dynamics, and social interactions in influencing productivity and job satisfaction.

- The findings of the studies continue to shape modern-day organizations, emphasizing the value of employee engagement, teamwork, and creating a positive work culture for optimal performance.

What is the Hawthorne Effect?

The Hawthorne Effect refers to the phenomenon where individuals change or improve an aspect of their behavior in response to their awareness of being observed.

How was the Hawthorne Effect identified?

It was identified during the Hawthorne Studies conducted at the Western Electric Hawthorne Works, where changes in work environment led to increased productivity, believed to be due to the workers’ awareness of being observed.

What were the Hawthorne Studies?

The Hawthorne Studies were a series of experiments on worker productivity conducted at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric Company in Chicago between 1924 and 1932.

Why is the Hawthorne Effect important in research?

In research, the Hawthorne Effect is important because it highlights the need to consider how the presence of researchers or the awareness of being studied can influence participants’ behavior.

Can the Hawthorne Effect affect the outcome of an experiment?

Yes, the Hawthorne Effect can significantly affect the outcome of an experiment as participants might alter their natural behavior due to the awareness of being observed or studied.

Is the Hawthorne Effect only observed in workplace settings?

No, the Hawthorne Effect can occur in various settings, including clinical trials, educational research, and workplace studies, essentially anywhere subjects are aware they are being observed.

How can researchers minimize the Hawthorne Effect?

Researchers can minimize the Hawthorne Effect by using control groups, ensuring anonymity, employing blind or double-blind study designs, and minimizing the intrusion of observation.

Does the Hawthorne Effect have implications for management?

Yes, in management, it suggests that giving attention to employees and making them feel valued can improve productivity and job satisfaction.

What criticisms have been made about the Hawthorne Effect?

Critics argue that the original studies had methodological flaws, and some suggest the effect might be overestimated or not as universal as once thought.

How is the Hawthorne Effect relevant in today’s workplace?

In modern workplaces, understanding the Hawthorne Effect is relevant for designing work environments and management practices that acknowledge the impact of observation and attention on employee behavior and productivity.

About The Author

Geoff Fripp

Related posts, theories of multiple intelligences.

The theory of Multiple Intelligences, introduced by Howard Gardner in 1983, challenges the traditional view of intelligence as a single, general ability.

Find out more...

Goal-setting Theory: Motivation

Motivation Definition: The reason or reasons to act in a particular way. It is what makes us do things and carry out tasks for the organisation.…

Fundamental Attribution Error

The Fundamental Attribution Error often means there are false reason why something happened, we have to look into why something happened, but look at it…

Personality in Organisations

Personality Definition: A personality is a mixture of a person’s characteristics, beliefs and qualities which make them who they are. What is the Definition of Personality?…

Module 6: Motivation in the Workplace

The hawthorne effect, learning outcome.

- Explain the role of the Hawthorne effect in management

During the 1920s, a series of studies that marked a change in the direction of motivational and managerial theory was conducted by Elton Mayo on workers at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company in Illinois. Previous studies, in particular Frederick Taylor’s work, took a “man as machine” view and focused on ways of improving individual performance. Hawthorne, however, set the individual in a social context, arguing that employees’ performance is influenced by work surroundings and coworkers as much as by employee ability and skill. The Hawthorne studies are credited with focusing managerial strategy on the socio-psychological aspects of human behavior in organizations.

The following video from the AT&T archives contains interviews with individuals who participated in these studies. It provides insight into the way the studies were conducted and how they changed employers’ views on worker motivation.

The studies originally looked into the effects of physical conditions on productivity and whether workers were more responsive and worked more efficiently under certain environmental conditions, such as improved lighting. The results were surprising: Mayo found that workers were more responsive to social factors—such as their manager and coworkers—than the factors (lighting, etc.) the researchers set out to investigate. In fact, worker productivity improved when the lights were dimmed again and when everything had been returned to the way it was before the experiment began, productivity at the factory was at its highest level and absenteeism had plummeted.

What happened was Mayo discovered that workers were highly responsive to additional attention from their managers and the feeling that their managers actually cared about and were interested in their work. The studies also found that although financial incentives are important drivers of worker productivity, social factors are equally important.

Practice Question

There were a number of other experiments conducted in the Hawthorne studies, including one in which two women were chosen as test subjects and were then asked to choose four other workers to join the test group. Together, the women worked assembling telephone relays in a separate room over the course of five years (1927–1932). Their output was measured during this time—at first, in secret. It started two weeks before moving the women to an experiment room and continued throughout the study. In the experiment room, they were assigned to a supervisor who discussed changes with them and, at times, used the women’s suggestions. The researchers then spent five years measuring how different variables affected both the group’s and the individuals’ productivity. Some of the variables included giving two five-minute breaks (after a discussion with the group on the best length of time), and then changing to two ten-minute breaks (not the preference of the group).

Changing a variable usually increased productivity, even if the variable was just a change back to the original condition. Researchers concluded that the employees worked harder because they thought they were being monitored individually. Researchers hypothesized that choosing one’s own coworkers, working as a group, being treated as special (as evidenced by working in a separate room), and having a sympathetic supervisor were the real reasons for the productivity increase.

The Hawthorne studies showed that people’s work performance is dependent on social issues and job satisfaction. The studies concluded that tangible motivators such as monetary incentives and good working conditions are generally less important in improving employee productivity than intangible motivators such as meeting individuals’ desire to belong to a group and be included in decision making and work.

- Boundless Management. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-management/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Revision and adaptation. Authored by : Linda Williams and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Tidewater Community College. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-introductiontobusiness/chapter/introduction-to-the-hawthorne-effect/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- AT&T Archives: The Year They Discovered People. Provided by : AT&T Tech Channel. Located at : https://youtu.be/D3pDWt7GntI . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Hawthorne Works. Provided by : Western Electric Company. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hawthorne_Works_aerial_view_ca_1920_pg_2.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Hawthorne Experiment

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 18 April 2024

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Sun Jianmin 2

It refers to a series of experiments conducted at the Hawthorne factory under Western Electric in Chicago, The United States and is also known as the Hawthorne study. From 1924 to 1932, the American psychologist George Mayo led a group of researchers to carry out four experiments in two phases within 8 years. The experiments began as an ergonomic study and later evolved into an interpersonal study. (1) Lighting experiment: it aimed to investigate the relationship between lighting and work efficiency, but the experimental result did not meet expectations, that is, the output of the experimental group kept increasing regardless of whether the lighting conditions were improved or deteriorated. (2) Welfare experiment: it aimed to study the impact of welfare measures on production. The result did not meet expectations either, that is, improvements in welfare measures did not affect the productivity of employees. (3) Interview experiment: from the above two experiments, Mayo realized that...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Further Reading

Aamodt MG (2012) Industrial/organizational psychology: an applied approach. Nelson Education, Melbourne

Google Scholar

Lu S-Z (2006) Management psychology. Zhejiang Education Publishing House, Hangzhou

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

Sun Jianmin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Jianmin, S. (2024). Hawthorne Experiment. In: The ECPH Encyclopedia of Psychology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6000-2_768-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6000-2_768-1

Received : 23 March 2024

Accepted : 25 March 2024

Published : 18 April 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-6000-2

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-6000-2

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

9.2 The Hawthorne Studies

- What did Elton Mayo’s Hawthorne studies reveal about worker motivation?

The classical era of management was followed by the human relations era, which began in the 1930s and focused primarily on how human behavior and relations affect organizational performance. The new era was ushered in by the Hawthorne studies, which changed the way many managers thought about motivation, job productivity, and employee satisfaction. The studies began when engineers at the Hawthorne Western Electric plant decided to examine the effects of varying levels of light on worker productivity—an experiment that might have interested Frederick Taylor. The engineers expected brighter light to lead to increased productivity, but the results showed that varying the level of light in either direction (brighter or dimmer) led to increased output from the experimental group. In 1927, the Hawthorne engineers asked Harvard professor Elton Mayo and a team of researchers to join them in their investigation.

From 1927 to 1932, Mayo and his colleagues conducted experiments on job redesign, length of workday and workweek, length of break times, and incentive plans. The results of the studies indicated that increases in performance were tied to a complex set of employee attitudes. Mayo claimed that both experimental and control groups from the plant had developed a sense of group pride because they had been selected to participate in the studies. The pride that came from this special attention motivated the workers to increase their productivity. Supervisors who allowed the employees to have some control over their situation appeared to further increase the workers’ motivation. These findings gave rise to what is now known as the Hawthorne effect , which suggests that employees will perform better when they feel singled out for special attention or feel that management is concerned about employee welfare. The studies also provided evidence that informal work groups (the social relationships of employees) and the resulting group pressure have positive effects on group productivity. The results of the Hawthorne studies enhanced our understanding of what motivates individuals in the workplace. They indicate that in addition to the personal economic needs emphasized in the classical era, social needs play an important role in influencing work-related attitudes and behaviors.

Concept Check

- How did Mayo’s studies at the Hawthorne plant contribute to the understanding of human motivation?

- What is the Hawthorne effect?

- Was the practice of dimming and brightening the lights ethical?

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Lawrence J. Gitman, Carl McDaniel, Amit Shah, Monique Reece, Linda Koffel, Bethann Talsma, James C. Hyatt

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Business

- Publication date: Sep 19, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/9-2-the-hawthorne-studies

© Apr 5, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- HBS Home HBS Index Contact Us

- Next A New Vision An Essay by Professors Michel Anteby and Rakesh Khurana

A New Vision

Two distinct aspects of vision characterize the Hawthorne Studies. The first is the more conventional definition of the term—vision as the act of perceiving a particular object or event. Through examining the everyday realities of organizational life, Fritz Roethlisberger and his colleagues found that the “person” and the “organization” could not be compartmentalized. Beneath the formalities of the organization chart was not chaos but a robust, informal organization, constituted by the activities, sentiments, interactions, norms, and personal and professional connections of individuals and groups that had developed over extended periods of time.

The existence of the informal organization, argued the Hawthorne researchers, meant that shaping human behavior was much more complicated than the then-dominant paradigm of scientific management had led managers to believe. The social system, which defined a worker’s relation to her work and to her companions, was not the product of rational engineering but of actual, deep-rooted human associations and sentiments. For example, on the question of the link between financial incentives and output, the Hawthorne researchers found that a worker might feel rewarded if she had pleasant associations with her co-workers and that this might mean more to her than a little extra money. Indeed, the researchers found that many workers resisted incentive plans because they felt they would be competing against people whose good will and companionship they valued. To take another example of the broader conception of human beings uncovered by the researchers, consider, for instance, an entry about a test room operator who was asked, “If given three wishes, what would they be?” “Health, to take a trip home at Christmas time, and to take a wedding trip to Norway next spring,” she replied. By noting these and other responses, the researchers highlighted that their conceptual blurring of person and organization was not a weak surrender of the possibility of applying science to administration, but an actual scientific working-through of the nature of human behavior based on careful empirical observation.

A second definition of vision is when one talks about a vision of the future. Here, vision operates in the realm of possibility, not actuality—creating, in effect, a new vocabulary of human motives. Confronted with the chaos and human suffering of the Depression, even the most avowed scientific scholars like Roethlisberger and his colleagues felt a moral imperative to identify what the right pattern of an society should be. Like most great researchers, the possibility for developing an imaginative reordering of life through the careful observation of a subject was part of the original impulse for why they studied these workers for so long. Consequently, we must ask what did they hope to gain in the way of describing the patterns of organizations as systems and human beings with sentiments and connections?

As Fritz Roethlisberger later revealed in his autobiography, his aim, as well as that of Elton Mayo and others working in the organizations group at Harvard Business School, was nothing less than an absolute commitment to lessen the gap between the possibilities grasped and the actualities illuminated through the application of theory and careful observation. Whereas scientific management made the simplification of work and the indifference of workers to anything but a financial reward seem almost both inevitable and desirable, the Hawthorne researchers identified that much of what individuals found meaningful in work was their association with others. The economic rewards of work were potentially picayune compared to the feeling of solidarity and worth created among individuals working together toward a common end. A manager’s effectiveness, therefore, could be measured on the extent to which those in the organization internalized a common purpose and perceived the connection between their actions and the organization’s ability to fulfill this common purpose. Management, then, was not about controlling human behavior but unleashing human possibility. By viewing the organization as a rationally engineered machine, scientific management had perverted the social character of work and thereby negated the individual. By reconceptualizing the organization as a social system that constantly adjusted to the needs, sentiments, and emotions of its members, and the members to it, Roethlisberger and his colleagues believed that organizational life presented a context—for both management and worker—to cultivate a meaningful existence.

The Hawthorne Studies were not perfect. Flaws in both method and interpretation appear with the perspective of hindsight. Perhaps most troubling is the researchers neglect of power. In their view, the manager or boss is morally chaste. Power is conceived only as the capacity to influence another person. Once power is seen as a matter of influence over someone else, for the sake of a goal like productivity, the actual conditions of power tend to disappear from view. But by having plunged into the experience of organizational life and then reflected on the meaning of it, the Hawthorne researchers came closer to outlining an integrated theory of human behavior than any other perspective before them and to describing a humanistic vision for workers inside an organization at precisely the time when industrial capitalism needed to be reconnected to addressing human concerns.

Michel Anteby is Assistant Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

Rakesh Khurana is Associate Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

- Introduction

- The Hawthorne Plant

- Employee Welfare

- Illumination Studies and Relay Assembly Test Room

- Enter Elton Mayo

- Human Relations and Harvard Business School

- Women in the Relay Assembly Test Room

- The Interview Process

- Spreading the Word

- The "Hawthorne Effect"

- Research Links

- Baker Library | Historical Collections | Site Credits | Digital Accessibility

- Contact Email: [email protected]

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Hawthorne Effect Works

Nick David / Getty Images

- Does It Really Exist?

Other Explanations

- How to Avoid It

The Hawthorne effect is a term referring to the tendency of some people to work harder and perform better when they are participants in an experiment.

The term is often used to suggest that individuals may change their behavior due to the attention they are receiving from researchers rather than because of any manipulation of independent variables .

The Hawthorne effect has been widely discussed in psychology textbooks, particularly those devoted to industrial and organizational psychology . However, research suggests that many of the original claims made about the effect may be overstated.

History of the Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect was first described in the 1950s by researcher Henry A. Landsberger during his analysis of experiments conducted during the 1920s and 1930s.

Why Is It Called the Hawthorne Effect?

The phenomenon is named after the location where the experiments took place, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works electric company just outside of Hawthorne, Illinois.

The electric company had commissioned research to determine if there was a relationship between productivity and work environments.

The original purpose of the Hawthorne studies was to examine how different aspects of the work environment, such as lighting, the timing of breaks, and the length of the workday , had on worker productivity.

Increased Productivity

In the most famous of the experiments, the focus of the study was to determine if increasing or decreasing the amount of light that workers received would have an effect on how productive workers were during their shifts. In the original study, employee productivity seemed to increase due to the changes but then decreased once the experiment was over.

What the researchers in the original studies found was that almost any change to the experimental conditions led to increases in productivity. For example, productivity increased when illumination was decreased to the levels of candlelight, when breaks were eliminated entirely, and when the workday was lengthened.

The researchers concluded that workers were responding to the increased attention from supervisors. This suggested that productivity increased due to attention and not because of changes in the experimental variables.

Findings May Not Be Accurate

Landsberger defined the Hawthorne effect as a short-term improvement in performance caused by observing workers. Researchers and managers quickly latched on to these findings. Later studies suggested, however, that these initial conclusions did not reflect what was really happening.

The term Hawthorne effect remains widely in use to describe increases in productivity due to participation in a study, yet additional studies have often offered little support or have even failed to find the effect at all.

Examples of the Hawthorne Effect

The following are real-life examples of the Hawthorne effect in various settings:

- Healthcare : One study found that patients with dementia who were being treated with Ginkgo biloba showed better cognitive functioning when they received more intensive follow-ups with healthcare professionals. Patients who received minimal follow-up had less favorable outcomes.

- School : Research found that hand washing rates at a primary school increased as much as 23 percent when another person was present with the person washing their hands—in this study, being watched led to improved performance.

- Workplace : When a supervisor is watching an employee work, that employee is likely to be on their "best behavior" and work harder than they would without being watched.

Does the Hawthorne Effect Exist?

Later research into the Hawthorne effect suggested that the original results may have been overstated. In 2009, researchers at the University of Chicago reanalyzed the original data and found that other factors also played a role in productivity and that the effect originally described was weak at best.

Researchers also uncovered the original data from the Hawthorne studies and found that many of the later reported claims about the findings are simply not supported by the data. They did find, however, more subtle displays of a possible Hawthorne effect.

While some additional studies failed to find strong evidence of the Hawthorne effect, a 2014 systematic review published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology found that research participation effects do exist.

After looking at the results of 19 different studies, the researchers concluded that these effects clearly happen, but more research needs to be done in order to determine how they work, the impact they have, and why they occur.

While the Hawthorne effect may have an influence on participant behavior in experiments, there may also be other factors that play a part in these changes. Some factors that may influence improvements in productivity include:

- Demand characteristics : In experiments, researchers sometimes display subtle clues that let participants know what they are hoping to find. As a result, subjects will alter their behavior to help confirm the experimenter’s hypothesis .

- Novelty effects : The novelty of having experimenters observing behavior might also play a role. This can lead to an initial increase in performance and productivity that may eventually level off as the experiment continues.

- Performance feedback : In situations involving worker productivity, increased attention from experimenters also resulted in increased performance feedback. This increased feedback might actually lead to an improvement in productivity.

While the Hawthorne effect has often been overstated, the term is still useful as a general explanation for psychological factors that can affect how people behave in an experiment.

How to Reduce the Hawthorne Effect

In order for researchers to trust the results of experiments, it is essential to minimize potential problems and sources of bias like the Hawthorne effect.

So what can researchers do to minimize these effects in their experimental studies?

- Conduct experiments in natural settings : One way to help eliminate or minimize demand characteristics and other potential sources of experimental bias is to utilize naturalistic observation techniques. However, this is simply not always possible.

- Make responses completely anonymous : Another way to combat this form of bias is to make the participants' responses in an experiment completely anonymous or confidential. This way, participants may be less likely to alter their behavior as a result of taking part in an experiment.

- Get familiar with the people in the study : People may not alter their behavior as significantly if they are being watched by someone they are familiar with. For instance, an employee is less likely to work harder if the supervisor watching them is always watching.

Many of the original findings of the Hawthorne studies have since been found to be either overstated or erroneous, but the term has become widely used in psychology, economics, business, and other areas.

More recent findings support the idea that these effects do happen, but how much of an impact they actually have on results remains in question. Today, the term is still often used to refer to changes in behavior that can result from taking part in an experiment.

Schwartz D, Fischhoff B, Krishnamurti T, Sowell F. The Hawthorne effect and energy awareness . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2013;110(38):15242-15246. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301687110

McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects . J Clin Epidemiol . 2014;67(3):267-277. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015

Letrud K, Hernes S. Affirmative citation bias in scientific myth debunking: A three-in-one case study . Bornmann L, ed. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222213

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2007;7:30. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-30

Pickering AJ, Blum AG, Breiman RF, Ram PK, Davis J. Video surveillance captures student hand hygiene behavior, reactivity to observation, and peer influence in Kenyan primary schools . Gupta V, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092571

Understanding Your Users . Elsevier ; 2015. doi:10.1016/c2013-0-13611-2

Levitt S, List, JA. Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments . 2009. University of Chicago. NBER Working Paper No. w15016,

Levitt, SD & List, JA. Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments . American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2011;3:224-238. doi:10.2307/25760252

McCambridge J, de Bruin M, Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review . PLoS ONE . 2012;7(6):e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116

Chwo GSM, Marek MW, Wu WCV. Meta-analysis of MALL research and design . System. 2018;74:62-72. doi:10.1016/j.system.2018.02.009

Gnepp J, Klayman J, Williamson IO, Barlas S. The future of feedback: Motivating performance improvement through future-focused feedback . PLoS One . 2020;15(6):e0234444. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234444

Hawthorne effect . The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. doi:10.4135/9781506326139.n300

Murdoch M, Simon AB, Polusny MA, et al. Impact of different privacy conditions and incentives on survey response rate, participant representativeness, and disclosure of sensitive information: a randomized controlled trial . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2014;14:90. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-90

Landy FJ , Conte JM. Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology . New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2010.

McBride DM. The Process of Research in Psychology . London: Sage Publications; 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Engineering

- Write For Us

- Privacy Policy

What is Hawthorne Experiment? Theory by Elton Mayo, 4 Phases

Hawthorne experiments were designed to study how different aspects of the work environment, such as lighting, the timing of breaks, and the length of the workday, had an on worker productivity. Here in this article, we have explained what is Hawthorne Experiment.

► What is Hawthorne Experiment?

The Hawthorne experiments were first developed in November 1924 at Western Electric Company’s Hawthorne plant in Chicago in Manufactured equipment for the bell telephone system and employed nearly 30,000 workers at the time of experiments.

Although, in all material aspects, this was the most progressive company with pension and sickness benefit schemes along with various recreational and other facilities discontent and dissatisfaction prevailed among the employees.

The initial tests were sponsored by the National Research Council (NRC) of the National Academy of Sciences. In 1927, a research team from Harvard Business School was invited to join the studies after the illumination test drew unanticipated results.

A team of researchers led by George Elton Mayo from the Harvard Business School carried out the studies (General Electric originally contributed funding, but they withdrew after the first trial was completed).

Experiments of Hawthorne effects work were conducted from 1924 to 1932. These studies mark the starting point of the field of Organizational Behaviour.

Initiated as an attempt to investigate how characteristics of the work setting affect employee fatigue and performance. (i.e., lighting) Found that productivity increased regardless of whether illumination was raised or lowered.

◉ Hawthorne Experiments were given by Elton Mayo

In 1927, a gathering of scientists driven by Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger of the Harvard Business School were welcome to participate in the investigations at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric Company, Chicago. The usefulness of representatives relies vigorously on the fulfillment of the representatives in their work circumstances.

Mayo’s thought was that legitimate elements were less significant than passionate variables in deciding usefulness effectiveness. Besides, of the relative multitude of human variables impacting representative conduct, the most remarkable were those exuding from the specialist’s investment in gatherings. Accordingly, Mayo inferred that work courses of action as well as meeting the true necessities of creation must simultaneously fulfill the worker’s emotional prerequisite of social fulfillment at his workplace.

The Hawthorne experiment can be divided into 4 significant parts:

- Experiments on Illumination.

- Relay Assembly Experiment.

- Mass Interviewing Program

- Bank Wiring Observation Room.

✔ 1. Illumination Experiment

The examinations in Illumination were an immediate augmentation of Elton Mayo’s previous light analyses done in the material business in 1923 and 1924. This trial started in 1924.

It comprised of a progression of investigations of test bunches in which the degrees of brightening shifted yet the circumstances were held steady. The reason behind it was to look at the connection of the quality and amount of light to the proficiency of laborers.

It was observed that the efficiency expanded to practically a similar rate in both test and control bunches chosen for the examinations. In the last investigation, it was found that result diminished with the diminished brightening level, i.e., moonlight power.

As the analysts didn’t observe a positive and straight connection between brightening and effectiveness of laborers, they inferred that the outcomes were ‘suspicious’ without even a trace of straightforward and direct circumstances and logical results relationship.

One of the critical realities revealed by the review was that individuals act diversely when they are being considered than they could somehow or another act. It is from this the term Hawthorne Effect was authored.

✔ 2. Relay Assembly Test Room Experiment

This stage pointed toward knowing the effect of brightening on creation as well as different variables like the length of the functioning day, rest hours, and other states of being.

In this trial, a little homogeneous work-gathering of six young ladies was established. These young ladies were amicable to one another and were approached to work in an extremely casual environment under the management of a scientist.

Efficiency and resolve expanded significantly during the time of the examination. Usefulness continued expanding and settled at an undeniable level in any event, when every one of the upgrades was removed and the pre-test conditions were once again introduced.

The analysts reasoned that socio-mental factors, for example, the sensation of being significant, acknowledgment, consideration, investment, durable work-bunch, and non-order oversight held the key to higher efficiency.

✔ 3. Mass Interview Program in Hawthorne Experiment

The goal of this program was to make an orderly investigation of the representative’s mentalities which would uncover the significance that their “working circumstance” has for them.

The specialists talked with countless laborers as to their viewpoints on work, working circumstances, and management.

At first, an immediate methodology was utilized by which meetings posed inquiries considered significant by supervisors and scientists.

The analysts say that the answers of the workers were monitored. Consequently, this approach was supplanted by a roundabout method, where the questioner essentially paid attention to what the workers needed to say.

The discoveries affirmed the significance of social elements at work in the absolute workplace.

✔ 4. Bank Wiring Room Study

The last Hawthorne analysis, called the bank wiring room study, was directed to notice and dissect the elements of a working bunch when impetus was presented. With the end goal of tests, a gathering of 14 laborers was utilized on bank wiring.

The work was conveyed between nine wiremen, three weld men, and two reviewers. In the bank wiring room study, the work bunch framed a standard that the gathering would play out a specific pre-chosen amount of work in a day.

The whole work bunch complied with this standard paying little mind to pay, which suggests that gathering rules were more significant for the individuals.

Subsequently, it was recommended to bring the administration and laborer’s goals in line to pursue the shared objectives to improve the association.

Must Read : 14 Principles of Management

► Features of Hawthorne Experiment

The highlight Features of the Hawthorne Experiment are:

1. A business association is fundamentally a social framework. It isn’t simply a techno-financial framework.

2. The business can be inspired by mental and social needs since its conduct is additionally affected by sentiments, feelings, and perspectives. Consequently, monetary impetuses are by all accounts not the only strategy to propel individuals.

3. The executives should figure out how to foster co-employable mentalities and not depend just on order.

Support turns into a significant instrument in human relations development. To accomplish interest, a successful two-way correspondence network is fundamental.

4. Usefulness is connected with representative fulfillment in any business association. In this way, the board should check out worker fulfillment. Bunch brain research assumes a significant part in any business association.

5. The neo-old style hypothesis stresses that man is a living machine and he is undeniably more significant than the lifeless machine. Subsequently, the way to higher efficiency lies in worker spirit. High confidence brings about higher results.

Related Articles More From Author

Factors influencing consumer behaviour, what is consumer behaviour, what is market segmentation.

MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Concepts » 4 Phases of Hawthorne Experiment – Explained

4 Phases of Hawthorne Experiment – Explained

At the beginning of the 20th century, companies were using scientific approaches to improve worker productivity. But that all began to change in 1924 with the start of the Hawthorne Studies, a 9-year research program at Western Electric Companies. The program, of which Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger played a major role, concluded that an organization’s undocumented social system was a powerful motivator of employee behavior. The Hawthorne Studies led to the development of the Human Relations Movement in business management . The experiment was about measuring the impact of different working conditions by the company itself (such as levels of lighting, payment systems, and hours of work) on the output of the employees. The researchers concluded that variations in output were not caused by changing physical conditions or material rewards only but partly by the experiments themselves. The special treatment required by experimental participation convinced workers that management had a particular interest in them. This raised morale and led to increased productivity. The term ‘Hawthorne effect’ is now widely used to refer to the behavior-modifying effects of being the subject of social investigation. The researchers concluded that the supervisory style greatly affected worker productivity. These results were, of course, a major blow to the position of scientific management, which held that employees were motivated by individual economic interest. The Hawthorne studies drew attention to the social needs as an additional source of motivation. Economic incentives were now viewed as one factor, but not the sole factor to which employees responded.

4 Phases of Hawthorne Experiment

The term “Hawthorne” is a term used within several behavioral management theories and is originally derived from the western electric company’s large factory complex named Hawthorne works. Starting in 1905 and operating until 1983, Hawthorne works had 45,000 employees and it produced a wide variety of consumer products, including telephone equipment, refrigerators and electric fans. As a result, Hawthorne works is well-known for its enormous output of telephone equipment and most importantly for its industrial experiments and studies carried out. Between 1924 and 1932, a series of experiments were carried out on the employees at the facility. The original purpose was to study the effect of lighting on workers’ productivity.

1. Illumination Studies

The National Research Council researchers concluded that a variety of factors must affect industrial output other than just the lighting effect because they continued to produce 7 million relays annually.

2. Relay Assembly Test Room Experiment

In order to observe the impact of these other factors, a second set of tests was begun before the completion of the illumination studies on April 25, 1987. The relay-assembly tests were designed to evaluate the effect rest periods and hours of work would have on efficiency. Researchers hoped to answer a series of questions concerning why output declined in the afternoon: Did the operators tire out? Did they need brief rest periods? What was the impact of changes in equipment? What were the effects of a shorter work day? What role did worker attitudes play? Hawthorne engineers led by George Pennock were the primary researchers for the relay-assembly tests, originally intended to take place for only a few months. Six women operators volunteered for the study and two more joined the test group in January 1928. They were administered physical examinations before the studies began and then every six weeks in order to evaluate the effects of changes in working conditions on their health. The women were isolated in a separate room to assure accuracy in measuring output and quality, as temperature, humidity, and other factors were adjusted. The test subjects constituted a piece-work payment group and efforts were made to maintain steady work patterns. The Hawthorne researchers attempted to gain the women’s confidence and to build a sense of pride in their participation. A male observer was introduced into the test room to keep accurate records, maintain cordial working conditions, and provide some degree of supervision.

Initially the women were monitored for productivity, and then they were isolated in a test room. Finally, the workers began to participate in a group payment rate, where extra pay for increased productivity was shared by the group. The other relay assemblers did not share in any bonus pay, but researchers concluded this added incentive was necessary for full cooperation. This single difference has been historically criticized as the one variable having the greatest significance on test results. These initial steps in the relay-assembly studies lasted only three months. In August, rest periods were introduced and other changes followed over the rest of the test period, including shortened work days and weeks. As the test periods turned from months into years, worker productivity continued to climb, once again providing unexpected results for the Hawthorne team to evaluate.

However the same experiment was done on a group of 6 women placed in the same room whereas the production increased because they felt like a group where they were all connected through a team work. This is common sense, just like in a class room; as students meet day by day and study together the same materials, they will feel a sense of freedom that they do not experience in a playground floor.

Mayo’s contributions became increasingly significant in the experiments during the interviewing stages of the tests. Early results from the illumination tests and the relay-assembly tests led to surveys of worker attitudes, surveys not limited to test participants.

Work Conditions and Productivity Results

- Under normal conditions with a forty-eight hour week, including Saturdays, and no rest pauses. The girls produced 2,400 relays a week each.

- They were then put on piecework for eight weeks. – Output increased

- They were given two five-minute breaks, one in the morning, and one in the afternoon, for a period of five weeks. – Output increased, yet again

- The breaks were each lengthened to ten minutes. – Output rose sharply

- Six five-minute breaks were introduced. The girls complained that their work rhythm was broken by the frequent pauses – Output fell only slightly

- The original two breaks were reinstated, this time, with a complimentary hot meal provided during the morning break. – Output increased further still

- The workday was shortened to end at 4.30 p.m. instead of 5.00 p.m. – Output increased

- The workday was shortened to end at 4.00 p.m. – Output leveled off

- Finally, all the improvements were taken away, and the original conditions before the experiment were reinstated. They were monitored in this state for 12 more weeks. – Output was the highest ever recorded – averaging 3000 relays a week

3. Bank-Wiring Tests

The bank-wiring tests were shut down in the spring of 1932 in reaction to layoffs brought on by the deepening depression. Layoffs were gradual, but by May the bank-wiring tests were concluded. These tests were intended to study the group as a functioning unit and observe its behavior. The study findings confirmed the complexity of group relations and stressed the expectations of the group over an individual’s preference. The conclusion was to tie the importance of what workers felt about one another to worker motivation. Industrial plants were a complex social system with significant informal organizations that played a vital role in motivating workers. The researchers found that although the workers were paid according to individual productivity, productivity decreased because the men were afraid that the company would lower the base rate. There was no trust between employees and researches, so they simply held down production to the level they thought was in their best interest; the same thing happens when a classmates of yours steal the exam paper and the administration finds out. You would not say who did it because you wouldn’t want your classmate to be kicked out of school. So, your interest is to say that you do not know hoping that they don’t change the exam answers.

Employees had physical as well as social needs, and the company gradually developed a program of human relations including employee counseling and improved supervision with an emphasis on the individual workers. The results were a reinterpretation of industrial group behavior and the introduction of what has become human relations.

4. The Interview Process

Mayo and Roethlisberger’s methodology shifted when they discovered that, rather than answering directed questions, employees expressed themselves more candidly if encouraged to speak openly in what was known as nondirected interviewing. “It became clear that if a channel for free expression were to be provided, the interview must be a listening rather than a questioning process,” a research study report noted. “The interview is now defined as a conversation in which the employee is encouraged to express himself freely upon any topic of his own choosing.”

Interviews, which averaged around 30 minutes, grew to 90 minutes or even two hours in length in a process meant to provide an emotional release. You always want to feel appreciated and taken into consideration from your boss or any other higher authority you are working with. This can create a trusting circle between both. Just like when you are supposed to learn from your teacher the materials she is giving you and at the same time you ask her for her advice on your personal life and start telling her what is going on with you in your daily life. You will feel a close relationship that connects you with the teacher and you will start to listen to her more and take into consideration what she is giving you as materials because there is a trust circle between both.

Roethlisberger discovered that what employees found most deeply rewarding were close associations with one another, “informal relationships of interconnectedness,” as he called them. “Whenever and where it was possible,” he wrote, generated them like crazy. In many cases they found them so satisfying that they often did all sorts of non logical thingsâ ‚¬ ¦in order to belong. In Mayo’s broad view, the industrial revolution had shattered strong ties to the workplace and community experienced by workers in the skilled trades of the 19th century. The social cohesion holding democracy together, he wrote, was predicated on these collective relationships, and employees’ belief in a sense of common purpose and value of their work.

The Hawthorne Legacy

The Hawthorne studies were conducted in three independent stages-the illumination tests, the relay-assembly tests, and the bank-wiring tests, although each was a separate experiment. The second and third each developed out of the preceding series of tests. Neither Hawthorne officials nor NRC researchers anticipated the duration of the studies, yet the conclusions of each set of tests and the Hawthorne experiments as a whole are the legacy of the studies and what sets them apart as a significant part of the history of industrial behavior and human relations.

Beyond the legacy of the Hawthorne studies has been the use of the term “Hawthorne effect” to describe how the presence of researchers produces a bias and unduly influences the outcome of the experiment. In addition, several important published works grew out of the Hawthorne experience, foremost of which was Mayo’s The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization and Roethlisberger and Dickson’s Management and the Worker.

The Hawthorne studies have been described as the most important social science experiment ever conducted in an industrial setting, yet the studies were not without their critics. Several criticisms, including those of sociologist Daniel Bell, focused on the exclusion of unionized workers in the studies. Sociologists and economists were the most commanding critics, defending their disciplinary turf more than offering serious criticisms. Despite these critical views, the flow of writings on the Hawthorne studies attests to their lasting influence and the fascination the tests have held for researchers. The studies had the impact of defining clearly the human relations school. Another contribution was an emphasis on the practice of personnel counseling. Industrial sociology owes its life as a discipline to the studies done at the Hawthorne site. This, in part, led to the enormous growth of academic programs in organizational behavior at American colleges and universities, especially at the graduate level.

Criticism of Hawthorne Studies