- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 13 June 2019

Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence for environmental policy and management: an overview of different methodological options

- Biljana Macura ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4253-1390 1 ,

- Monika Suškevičs 2 ,

- Ruth Garside 3 ,

- Karin Hannes 4 ,

- Rebecca Rees 5 &

- Romina Rodela 6 , 7

Environmental Evidence volume 8 , Article number: 24 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

22 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative research related to the human dimensions of conservation and environment is growing in quantity. Rigorous syntheses of such studies can help develop understanding and inform decision-making. They can combine findings from studies in varied or similar contexts to address questions relating to, for example, the lived experience of those affected by environmental phenomena or interventions, or to intervention implementation. Researchers in environmental management have adapted methodology for systematic reviews of quantitative research so as to address questions about the magnitude of intervention effects or the impacts of human activities or exposure. However, guidance for the synthesis of qualitative evidence in this field does not yet exist. The objective of this paper is to present a brief overview of different methods for the synthesis of qualitative research and to explore why and how reviewers might select between these. The paper discusses synthesis methods developed in other fields but applicable to environmental management and policy. These methods include thematic synthesis, framework synthesis, realist synthesis, critical interpretive synthesis and meta-ethnography. We briefly describe each of these approaches, give recommendations for the selection between them, and provide a selection of sources for further reading.

Qualitative research related to the human dimensions of conservation and environment is growing in quantity [ 1 , 2 ] and robust syntheses of such research are necessary. Systematic reviews, where researchers use explicit methods for identifying, appraising, analysing and synthesising the findings of studies relevant to a research question, have long been considered a valuable means for informing research, policy and practice across various sectors, from health to international development and conservation [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ].

The methodological development of systematic reviews took off in the 1980s, initially with a strong focus on the synthesis of quantitative data. The exploration of specific methods for qualitative synthesis started to grow a decade or so later [ 8 , 9 ]. Examples addressed questions related to the lived experience of those affected by, and the contextual nuances of, given interventions. The methodology for the synthesis of quantitative research appears to have been adapted for environmental management for the first time in 2006 and has been developing since [ 10 , 11 ]. However, guidance in the field for those producing or interested in working with qualitative evidence synthesis still does not exist.

To date, the vast majority of systematic reviews in environmental management are syntheses of quantitative research evidence that evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention or the impact of an activity or exposure [ 12 ]—here called systematic reviews of quantitative evidence. These typically aggregate relatively homogenous outcome measures from similar interventions or exposures to create a more precise and accurate summary estimate of an overall effect [ 13 , 14 ].

Current debates about systematic reviews of quantitative evidence in other fields point out that such reviews, while they address essential questions about the magnitude of effects or impacts, cannot help us answer other policy- and practice-relevant issues [ 15 , 16 ]. In addition, the complexity within studies on impacts of environmental actions or exposures, and in studies of environmental management initiatives, will mean that a simple aggregation of study findings will only mask important differences and enable us to predict very little about what might happen to whom (human or otherwise) in any set of given circumstances. Here we argue that qualitative evidence syntheses can add value to environmental research and decision-making. Systematic reviews that make use of qualitative research can provide a rigorous evidence base for a deeper understanding of the context of environmental management. They can give useful input to policy and practice on (1) intervention feasibility and appropriateness (e.g., how a management strategy might best be implemented? What are people’s beliefs and attitudes towards a conservation intervention? ); (2) intervention adoption or acceptability (e.g., what is the extent of adoption of a conservation intervention?; What are facilitators and barriers to its acceptability? ); (3) subjective experience (e.g., what are the priorities and challenges for local communities? ); and (4) heterogeneity in outcomes (e.g., what values do people attach to different outcomes? For whom and why did an intervention not work? ) [ 8 , 15 , 17 , 18 ].

In common with individual studies of quantitative research, individual qualitative studies may be subject to limitations, in terms of their breadth of inquiry, conceptual reach and/or methodology or conduct. Projects that systematically find, describe, appraise and synthesise qualitative evidence can provide findings that are more broadly applicable to new contexts [ 19 ] or explanations that are more complete [ 20 ]. Such qualitative evidence syntheses (QES) may stand alone, be directly related to a systematic review of quantitative evidence on a related question(s) or may be part of mixed methods multi-component reviews that aim to bring two distinct syntheses of evidence together.

In spite of its value, there is a limited discussion on the synthesis of qualitative research evidence in the environmental field and tailored methodological guidance could usefully address how to:

conduct syntheses of evidence so as to go beyond questions of effectiveness or impact;

use synthesis to identify explanations for and produce higher levels of interpretation of the phenomena under study;

include rich descriptive and often heterogeneous evidence from different research domains; and

combine and link qualitative and quantitative evidence.

The objective of this paper is to present a brief overview of different methodological options for the synthesis of qualitative research developed in other fields (such as health, education and social sciences) and applicable to environmental management practice and policy. A selection of sources for further reading, including those that expand on how to identify, describe and appraise evidence for QES is also included. Before describing the different synthesis options, we briefly explore the nature of environmental problems and management to explain the context for QES in this field.

The context of environmental policy, management, and research

Environmental and conservation problems are wicked, highly complex, and embedded in ecological as well as social systems [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. The complexity stems from several sources: (1) a high level of uncertainty; (2) large temporal and spatial scale; (3) cross-sectoral and multi-level spanning; and (4) the irreversibility of potential damages [ 25 , 26 ]. The loss of global biodiversity or changes in the global climate system [ 27 , 28 ] can illustrate this complexity: our knowledge about these systems is imperfect, a multiplicity of actors is associated with them (see, e.g., [ 22 , 25 ]); their impacts span from local to global levels and the damages potentially cannot be repaired [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. On top of this, interventions to address these challenges are themselves often complex, in that they are made up of many interacting components and are introduced into and rely upon social systems for their implementation [ 32 ].

Instead, the dynamic nature and complexity of environmental problems, and their possible solutions call for the use and integration of scientific knowledge from several and different disciplinary domains. This need is reflected already in the interdisciplinary nature of environmental research that occurs at the level of theory, methods and/or data [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Environmental research is frequently based on observational studies [ 37 ]. Studies are commonly developed around a well-defined theoretical and a geographical boundary, with the aim to develop a comprehensive understanding of the chosen phenomena. However, this means that such research produces highly heterogeneous evidence scattered across different contexts [ 38 ].

These issues related to the type and nature of environmental evidence imply that systematic review methods need to include a plurality of different approaches [ 39 ]. Adding qualitative and mixed methods evidence synthesis to the systematic review toolbox may be vital in cases where context is very important, complexity and heterogeneity is the norm, and where a more in-depth understanding of the views and experiences of various actors can help to explain how, why and for whom an intervention does or does not work [ 18 ]. These methods can further aid in the understanding of success and failure of environmental interventions through the analysis of implementation factors. Furthermore, they can also help in describing the range and nature of impacts, and in understanding unintended or unanticipated impacts [ 40 ].

What is qualitative evidence synthesis (QES)?

Qualitative evidence synthesis refers to a set of methodological approaches for systematically identifying, screening, quality appraisal and synthesis of primary qualitative research evidence. Various labelling terms have been used (see Box 1 ).

It should be noted here that QES is distinct from two other categories of reviews that have been labelled as ‘qualitative’. The first category contains narrative summaries of findings from studies with quantitative data. Here, the original intention was to use quantitative synthesis methods (e.g., meta-analysis) but that was not possible due to, for example, the heterogeneity between studies. Review authors in the second category have the intention to use a narrative approach to synthesis of quantitative data right from the start. Neither of these two review categories is discussed further here.

Box 1 Definitions and labels

Qualitative research refers to a wide range of different kinds of research studies that tend to collect and analyse qualitative data, to organise and interpret the results and produce findings that are largely narrative in form (see also [ 41 ]).

Qualitative data typically refers to textual data (although other types of data, such as visual data, can be produced during the research process). Data are obtained through recording of, for example, e.g., individual or group interviews, or observations of behaviours.

Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) is an umbrella term that encompasses a set of various methodological approaches for systematically identifying, screening, quality appraising and synthesising primary qualitative research evidence.

Other generic terms used for qualitative evidence synthesis:

Systematic review of qualitative research

Qualitative systematic reviews

Meta-synthesis

Qualitative research synthesis

An overview of QES approaches

In common with methods for systematic reviews of quantitative evidence, there are a number of stages of the systematic review process which are followed in most QES approaches, including (1) question formulation, (2) searching for literature, (3) eligibility screening, (4) quality appraisal, (5) synthesis and (6) reporting of findings. However, the methods used within each of these stages varies, depending on the specific review approach adopted with its epistemology and relation to theory.

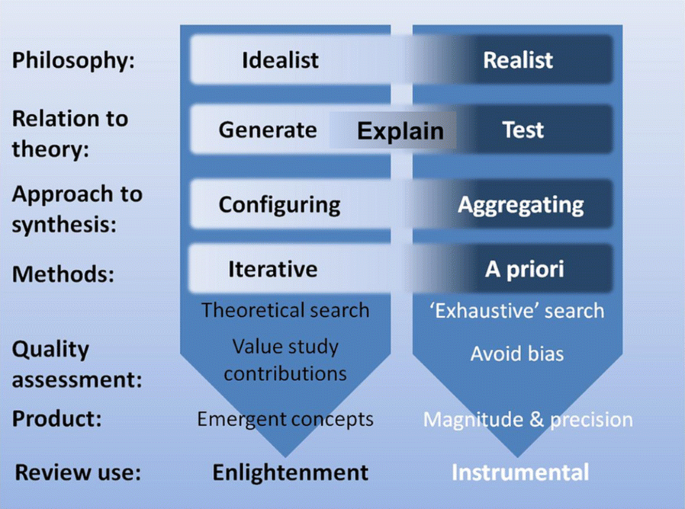

QES approaches lie on an epistemological continuum between idealist and realist positions and can be positioned anywhere between the two extremes ([ 16 , 42 , 43 ], see Fig. 1 ). Idealist approaches to synthesis operate under the assumption that there is no single ‘correct’ answer, but the focus is in understanding variation in different conceptualisations [ 43 ]. They are less bound by pre-defined procedures and have open review questions allowing for constantly emerging concepts and theories [ 44 ]. In these iterative approaches, any stage of the review process may be revisited as the ideas develop through interaction with the evidence base. The iterations are recorded, described and justified in the write-up. These approaches may aim to create a model or theory that increases our understanding of what might hinder or facilitate the uptake of a policy or a program, or how a phenomenon operates and is experienced. Approaches on the realist side of the continuum assume that there is a single independent and knowable reality, and review findings are understood as an objective interpretation of this reality [ 43 , 45 ]. The review questions are closed and fixed, and the reviews follow strict formal linear methodological procedures. These approaches usually aim to test existing theories ([ 43 ], see Fig. 1 ).

(Source: Gough et al. [ 43 ])

Dimensions of difference in review approaches

QES approaches may also vary in the way they address and understand the importance of the context and so, they can be multi-context or context-specific. Multi-context reviews aim at an exhaustive sampling of literature to include diverse contexts, e.g., different geographical, socio‐cultural, political, historical, economic, ecological settings. Such reviews are currently common in systematic reviews of quantitative evidence. Context-specific QES use selective sampling and focuses on only one context to provide specific understanding to a targeted audience and develop theories that are specific to the local setting (see [ 46 ]).

In the following sub-sections, we give an overview of five commonly used qualitative synthesis methods: thematic synthesis, framework synthesis, realist synthesis, critical interpretative synthesis and meta-ethnography [ 47 , 48 ]. Table 1 shows the main purpose of the method, a type of the review question and a type of evidence commonly used in the synthesis stage (qualitative or mixed) and key readings. Anyone wanting to undertake a review should keep in mind that each method might imply a specific approach to review stages (from literature search to critical appraisal) and the key readings listed in Table 1 should be checked for specific advice.

- Framework synthesis

Framework synthesis uses a deductive approach and it has been used for the syntheses of qualitative data alone (e.g., [ 49 ]), as well as by those undertaking mixed methods syntheses [ 50 , 51 ]. Framework synthesis has been grouped along with other approaches that are less suitable for developing explanatory theory through interpretation or making use of rich reports in study findings. The approach can be seen as one means of exploring existing theories [ 42 ]. Framework synthesis begins with an explicit conceptual framework. Reviewers start their synthesis by using the theoretical and empirical background literature to shape their understanding of the issue under study. The initial framework that results might take the form of a table of themes and sub-themes and/or a diagram showing relationships between themes. Coding is initially based on this framework. This framework is then developed further during the synthesis as new data from study findings are incorporated and themes are modified, or further themes are derived. The findings of a framework synthesis usually consist of a final, revised framework, illustrated by a narrative description that refers to the included studies. The initial conceptual framework in framework synthesis is seen as providing a “scaffold against which findings from the different components of an assessment may be brought together and organise” ([ 52 ]:29). The approach builds upon framework analysis, which is a method of analysing primary research data that has often been applied to address policy concerns [ 53 ].

Six stages of framework synthesis are generally identified: familiarisation, framework selection, indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation. In the familiarisation stage reviewers aim to become acquainted with current issues and ideas about the topic under study. The involvement of subject experts in the team can be particularly helpful at this stage. The next stage, framework selection, sees reviewers finalising their initial conceptual framework. Here some argue for the value of quickly selecting a ‘good enough’ existing framework [ 52 ], rather than developing one from a variety of sources. An indexing stage then sees reviewers characterising each included study according to the a priori framework. In the charting stage reviewers analyse the main characteristics of each research paper, by grouping characteristics into categories related to the framework and deriving themes directly from those data. During the mapping stage of a framework synthesis, derived themes are considered in the light of the original research questions and the reviewer draws up a presentation of the review’s findings. The interpretation stage, as with much research, is the point at which the findings are considered in relation to the wider research literature and the context in which the review was originally undertaken.

Framework synthesis is relatively structured and therefore able to accommodate quite large amounts of data. Like thematic synthesis (see below), researchers using this method often seek to provide review output that is directly applicable to policy and practice. This method can be suitable for understanding feasibility and acceptance of conservation interventions. A variation of the method, the ‘best-fit synthesis’ approach, might help if funder timescales are extremely tight [ 54 ]. A review by Belluco and colleagues [ 55 ] of the potential benefits and challenges from nanotechnology in the meat food chain is a recent example of framework synthesis. Here reviewers coded studies to describe the area of the meat supply chain, using a pre-specified framework. Belluco’s team interrogated their set of 79 studies to derive common themes as well as gaps—areas of the framework where studies appeared not to have been conducted.

- Thematic synthesis

Thematic synthesis draws on methods of thematic analysis for primary qualitative research and is a common approach to qualitative evidence synthesis in health and other disciplines [ 56 ]. Examples in the literature range from more descriptive to more interpretative approaches. Findings from the included studies are either extracted and then coded or, increasingly, full-texts of the eligible studies are uploaded into appropriate software (e.g., NVIVO or EPPI-reviewer) and coded there. These codes are used to identify patterns and themes in the data. Often these codes are descriptive but can then be built up into more conceptual or theory-driven codes. Initial line-by-line descriptive coding groups together ideas from pieces of text within and across the included papers. Similarities and differences are then grouped together into hierarchical codes. These are then revisited, and new codes developed to capture the meaning of groups of the initial codes. A narrative summary of the findings, describing these themes is then written. Finally, these findings can be interpreted to explore the implications of these findings for the context of a specific policy or practice question that has framed the review. The method is therefore suitable for addressing questions related to effectiveness, need, appropriateness and acceptability of an intervention [ 16 ] and usually from the point of view of the targeted groups (e.g., local communities, conservation managers, etc.). Similar to systematic reviews of quantitative research, this method attempts to retain the explicit and transparent link between review conclusions and the included primary studies [ 56 ]. There are only a few examples of reviews in the environmental management field that have explicitly applied thematic synthesis. For instance, Schirmer and colleagues [ 57 ] use “thematic coding” [ 56 ] (within the approach they call qualitative meta-synthesis) to analyse the role of Australia’s natural resource management programs in farmers’ wellbeing. Haddaway and colleagues [ 58 ] use thematic synthesis to define the term “ecotechnology”.

- Meta-ethnography

This method was developed by Noblit and Hare [ 59 ] and originally applied to the field of education. The method was further improved in the early 2000s by Britten and colleagues [ 60 ] who applied it to health services research and has since been used for increasing numbers of evidence synthesis, particularly in health research and other topic areas.

Meta-ethnography is an explicitly interpretative approach to synthesis and aims to create new understandings and theories from a body of work. It uses authors’ interpretations (sometimes called second-order constructs, where the quotes from study participants are first-order constructs) and looks for similarities and differences at this conceptual level. It uses the idea of “translation” between constructs in the included studies. This involves juxtaposing ideas from studies and examining them in relation to each other, in order to identify where they are describing similar or different ideas.

This method includes seven stages: (1) identification of the intellectual interest that the review might inform; (2) deciding what is relevant to the initial interest; (3) reading the studies and noting the concepts and themes; (4) determining how the studies are related; (5) translating studies into one another; (6) synthesising translations; and (7) communicating review findings [ 59 ]. There are three main types of synthesis (stages 5 and 6): reciprocal translation, refutational translation, and line of argument. Different findings within a single meta-ethnography may contain examples of one or all of these approaches depending on the nature of the findings within the included studies. Reciprocal translation is used where concepts from different studies are judged to be about similar ideas, and so can be “translated into each other”. Refutational translation refers to discordant findings, where differences cannot be explained by differences in participants or within a theoretical construct. A line of argument can be constructed to identify how translated concepts are related to each other and can be joined together to create a more descriptive understanding of the findings as a whole. This method is therefore very well suited to produce new interpretations, theories or conceptual models [ 61 , 62 ]. In the conservation, this method could be used to understand how, for example, local communities experience conservation interventions and how this influences their acceptance of conservation interventions. Head and colleagues [ 63 ] used meta-ethnography to understand dimensions of household-level everyday life that have implications for climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Critical interpretive synthesis

The critical interpretive synthesis approach was originally developed by Dixon-Woods and colleagues [ 64 ]. Review authors using this approach [ 64 ] are interested in theory generation while being able to integrate findings from a range of study types, and empirical and theoretical papers. Further, this method can integrate a variety of different types of evidence from quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies. We included critical interpretative synthesis in our paper because this method is often used for synthesis of qualitative evidence.

In the overall synthesis a coherent framework is usually presented, showcasing a complex network of interrelating theoretical constructs and the relationships between them. The framework partly builds on existing constructs as reported in the different studies and introduces newly derived, synthetic constructs generated through the synthesis procedure itself. Reported themes are then gradually mapped against each other to create an overall understanding of the phenomenon of interest. This is similar to developing a line of argument in a meta-ethnography (see above). Critical interpretive synthesis distinguishes itself from other approaches such as formal grounded theory [ 65 , 66 ] and meta-ethnography by adopting a critical stance towards findings reported in the primary studies, the assumptions involved, and the recommendations proposed. Rather than taking the findings for granted, review authors involved in critical interpretive synthesis “critically question the entire construction of the story the primary-level authors told in their research reports” [ 17 ]. They would potentially critique recommendations based on, e.g., ethical or moral arguments, such as the desirability of a particular rollout of an intervention. This method is therefore very well suited for understanding of what may have influenced proposed solutions to a problem [ 64 ] and to examine the constructions of concepts [ 67 ]. In the environmental field, this method could, for example, be applied to understand how different narratives influence environmental practice and policy or to critically assess new forms of conservation governance and management. Explicit examples of critical interpretive synthesis review projects applied to the broad area of environmental sciences are currently non-existent to our knowledge. However, there are a few related examples from health studies, such as review on environmentally responsible nursing [ 68 ]. In that review, authors justify the use of critical interpretative synthesis mainly by the ability of this method to synthesise diverse types of primary studies in terms of their topic and methodology.

- Realist synthesis

Realist synthesis is a theory-driven approach to combining evidence from various study types. Originally developed in 2005 by Ray Pawson and colleagues [ 69 ], it is aimed at unpacking the mechanisms for how particular interventions work, for whom and in which particular context and setting. It is included here because it is increasingly used for synthesising qualitative data, although data can be both qualitative and quantitative.

Realist synthesis has been developed to evaluate the integrity of theories (does a program work as predicted) and theory adjudication (which intervention fits best). In addition, it allows for a comparison of interventions across settings or target groups or explains how the policy intent of a particular intervention translates into practice [ 69 ].

The realist synthesis approach is highly iterative, so it is difficult to identify a distinct synthesis stage as such. The synthesis process usually starts by identifying theories that underpin specific interventions of interest. The theoretical assumptions about how an intervention is supposed to work and what impact it is supposed to generate are made explicit from the start. Depending on the exact purpose of the review, various types of evidence related to the interventions under evaluation (potentially both quantitative and qualitative) are then consulted and appraised for quality. In evaluating what works for whom in which circumstances, contradictory evidence is used to generate insights about the influence of context and so to link various configurations of context, mechanism and outcome. Conclusions are usually presented as a series of contextualised decision points. An example of a realist synthesis in the environmental context is the one from McLain, Lawry and Ojanen [ 70 ] in which the evidence of 31 articles examine the environmental outcomes of marine protected areas governed under different types of property regimes. The use of a realist synthesis approach allowed the review authors to gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which mechanisms such as perceptions of legitimacy, perceptions of the likelihood of benefits, and perceptions of enforcement capacity interact under different socio-ecological contexts to trigger behavioural changes that affect environmental conditions. Another example from the environmental domain is the review by Nilsson and colleagues [ 71 ] who applied a realist synthesis to 17 community-based conservation programs in developing countries that measured behavioural changes linked to conservation outcomes. The RAMESES I project ( http://www.ramesesproject.org ) offers methodological guidance, publication standards and training resources for realist synthesis.

Choosing the appropriate QES method

Here we explain the criteria for the selection of different QES methods presented in this paper.

There are several aspects to be considered when choosing the right evidence synthesis approach [ 42 , 67 , 72 ]. These include the type of a review question, epistemology, purpose of the review, type of data, and available expertise including the background of the research team and resource requirements. Here, we briefly discuss the more pragmatic aspects to be considered. For a detailed discussion of other criteria we refer the reader to the work of Hannes and Lockwood [ 67 ], and Booth and colleagues [ 42 , 72 ].

Particularities of the evidence

As noted above, environmental problems are complex and involve a high degree of uncertainty. Environmental research is often inter- and transdisciplinary and involves, for example, the use of contested and/or diverse concepts and terms, as well as heterogeneous datasets. Thus, it is very important to understand if the QES method is fit-for-purpose and if it will result in the expected and desired synthesis outcomes. More complex and contextual outcomes are expected from the idealist methods (such as critical interpretative synthesis or meta-ethnography) (Fig. 1 and Table 1 ), which offer insights to policy or practice only after further interpretation. In contrast, more concrete and definitive outcomes can be expected from more realist methods (such as thematic synthesis) [ 67 ]. The type of evidence to be synthesised (e.g., qualitative or mixed, see Table 1 ) is yet another aspect needing consideration when choosing the synthesis method.

Background of the researchers and the review team

Researchers should consider their methodological backgrounds and epistemological viewpoints, to make sure they have appropriate expertise as well as experience in the review team when choosing the method. Some more complex methods (such as realist synthesis) may require specific skills (e.g., a familiarity with the realist perspective), and larger teams of researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds. Such methods may also require that the researchers are more familiar with the content of the research they review. Other methods (such as thematic or framework synthesis) can be done in a smaller team of researchers who do not necessarily have deeper subject expertise.

Resource requirements

Requirements for review funding will obviously depend on the resource requirements, i.e. a number of researchers to be involved, the time needed to conduct a review, costs associated with access to a specific data analysis or review management software, and access to literature. Some methods may be more resource demanding. Multi-component mixed method reviews, for example, requires expertise in both qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods, as well as the allocation of time for producing more than one parallel and/or consecutive syntheses. Other methods, such as framework synthesis, are maybe less resource-consuming (needing comparatively fewer people over less time) as long as initial frameworks have already been developed and are uncontentious. The issue of time spent on a review also depends on the breadth of the research question and the extent of the literature.

Challenges and points of contestation

Whilst QES can be valuable for environmental practice and policy, readers should be aware of several well-known challenges that might also appear problematic when QES approaches are used for the synthesis of environmental qualitative research. Here we summarise some of the most important ones including conceptual and methodological heterogeneity in primary research studies, issues with quality appraisal and transparency in reporting.

Qualitative evidence is likely to be situated in different disciplines, theoretical assumptions, and general philosophical orientations [ 73 ]. For aggregative less interpretative methods (such as framework synthesis), this poses a challenge in terms of comparability during the synthesis stage of the review process. In case of more interpretive approaches (e.g., meta-ethnography), such diversity is often seen as an asset rather than a problem as the translation of one study to another [ 74 ] allows for a comparison of studies with different theoretical backgrounds.

As with systematic reviews of quantitative evidence, critical appraisal of study validity is perhaps one of the most contested stages of the QES review process [ 75 ]. Quality appraisal (and the extent to which it matters) likely depends on the methodological approach. For example, framework and thematic syntheses assess the reliability and methodological rigour of individual study findings and may exclude methodologically flawed studies from the synthesis. Meta-ethnography or critical interpretative synthesis assess included studies in terms of content and utility of their findings, level to which they inform theory and include all studies in the synthesis [ 16 ].

Finally, reviews can be often criticised for lack of transparency and unclear or incomplete reporting. However, to ensure that all the important decisions related to the review conduct are reported at the sufficient level of detail, there are reporting standards applicable for QES such as ENTREQ [ 76 ] and ROSES [ 77 ]. Additionally, RAMESES are reporting standards developed specifically for realist syntheses [ 78 ] and the EMERGE project developed reporting standards for meta-ethnographies ([ 79 ], http://emergeproject.org ). These standards aim to increase transparency and hopefully drive up the quality of the review conduct [ 80 ].

Additional methodological options: Linking quantitative and qualitative evidence together

In the following paragraphs, we briefly present an additional methodological option that could be, for example, useful for the synthesis of complex conservation interventions and is suited to address some of the above challenges (such as methodological heterogeneity).

Namely, in some cases, synthesis of only one type of study findings (either qualitative or quantitative) might not be sufficient to understand multi-layered or complex interventions or programs typical for the environmental sector. The mixed methods review approach has been developed to link qualitative, mixed and quantitative study findings in a way to enhance the breadth and depth of understanding phenomena, problems and/or study topics [ 81 , 82 ]. Mixed methods reviews is a systematic review in which quantitative, qualitative and primary studies are synthesized using both quantitative and qualitative methods [ 81 ]. The data included in such a review are the findings or results extracted from either quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods primary studies. These findings are then integrated using a mixed method analytical approach [ 17 ].

This approach allows us to study how different (intervention) components are related and how they interact with each other [ 83 ]. Apart from studying the effectiveness of interventions, these reviews include qualitative evidence on the contextual influence, applicability and barriers to implementation for these interventions. For example, topics covered by reviews that link qualitative and quantitative data are the impact of urban design, land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity [ 84 ]; the socio-economic effects of agricultural certification schemes [ 85 ]; the impact of outdoor spaces on wellbeing for people with dementia [ 86 ]. Qualitative and quantitative bodies of evidence can point to different facets of the same phenomena and enrich understanding of it. In a review on protected area impacts on human wellbeing [ 87 ], it is revealed that qualitative findings were not studied quantitatively and only once combined in a synthesis these two evidence bases could provide a complete picture of the protected area impact.

Conclusions

Synthesis of qualitative research is crucial for addressing wicked environmental problems and for producing reliable support for decisions in both policy and practice. We have provided an overview of methodological approaches for the synthesis of qualitative research, each characterised by different ways of problematising the literature and level of interpretation. We have also explained what needs to be considered when choosing among these methods.

Environmental and conservation social science has witnessed an accumulation of primary research during the past decades. However, social scientists argue that there is a little integration of qualitative evidence into conservation policy and practice [ 33 ], and this suggests that there is a ‘synthesis gap’ (sensu [ 88 ]). This paper, with an overview of different methodological tools, provides the first guidance for environmental researchers to conduct synthesis of qualitative evidence so that they can start bridging the synthesis gap between environmental social science, policy and practice. Furthermore, introduced examples may inspire reviewers to adapt existing methods to their specific subject and, where necessary, help develop new methods that are a better fit for the field of environmental evidence. This is especially important as currently used methods in synthesis of environmental evidence fall short on utilising the potential of qualitative research that translates into lack of a deeper contextual understanding around implementation and effectiveness of environmental management interventions, and disregard the diversity of perspectives and voices (e.g., indigenous peoples, farmers, park managers) fundamental for tackling wicked environmental issues.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Janssen MA, Schoon ML, Ke W, Börner K. Scholarly networks on resilience, vulnerability and adaptation within the human dimensions of global environmental change. Glob Environ Change. 2006;16(3):240–52.

Article Google Scholar

Xu L, Kajikawa Y. An integrated framework for resilience research: a systematic review based on citation network analysis. Sustain Sci. 2018;13:235–54.

Haddaway NR, Pullin AS. The policy role of systematic reviews: past, present and future. Springer Science Rev. 2014;14:179–83.

Pullin AS, Knight TM. Doing more good than harm: building an evidence-base for conservation and environmental management. Biol Cons. 2009;142:931–4.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(oct18_2):d5928.

The Steering Group of the Campbell Collaboration: Campbell collaboration systematic reviews: policies and guidelines. Campbell systematic reviews, (supplement 1), p. 46; 2015.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Hannes K, Booth A, Harris J, Noyes J. Celebrating methodological challenges and changes: reflecting on the emergence and importance of the role of qualitative evidence in Cochrane reviews. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):84–84.

Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1_suppl):6–20.

Pullin AS, Stewart GB. Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol. 2006;20:1647–56.

Roberts PD, Stewart GB, Pullin AS. Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol Conserv. 2006;132:409–23.

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. Guidelines and standards for evidence synthesis in environmental management. Version 5.0; Eds. Pullin AS, Frampton GK, Livoreil B, Petrokofsky G. 2018. Available from: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors . Accessed 1 Oct 2018.

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2012.

Google Scholar

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Leeman J, Crandell JL. Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. J Mixed Methods Res. 2012;6(4):317–31.

Dalton J, Booth A, Noyes J, Sowden AJ. Potential value of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in informing user-centered health and social care: findings from a descriptive overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:37–46.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59.

Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. Using mixed methods research synthesis for literature reviews, vol. 4. London: Sage; 2017.

Adams WM, Sandbrook C. Conservation, evidence and policy. Oryx. 2013;47:329–33.

Sandelowski M. Reading, writing and systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(1):104–10.

Paterson BL, Dubouloz C-J, Chevrier J, Ashe B, King J, Moldoveanu M. Conducting qualitative metasynthesis research: insights from a metasynthesis project. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8:22–33.

Game ET, Meijaard E, Sheil D, McDonald-Madden E. Conservation in a wicked complex world: challenges and solutions. Conserv Lett. 2014;7(3):271–7.

Dewulf A, Craps M, Bouwen R, Taillieu T, Pahl-Wostl C. Integrated management of natural resources: dealing with ambiguous issues, multiple actors and diverging frames. Water Sci Technol. 2005;52(6):115–24.

Article CAS Google Scholar

DeFries R, Nagendra H. Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science. 2017;356(April):265–70.

Dick M, Rous AM, Nguyen VM, Cooke SJ. Necessary but challenging: multiple disciplinary approaches to solving conservation problems. Facets. 2017;1(1):67–82.

Brugnach M, Ingram H. Ambiguity: the challenge of knowing and deciding together. Environ Sci Policy. 2012;15:60–71.

Van Den Hove S. Participatory approaches to environmental policy-making: the European Commission Climate Policy Process as a case study. Ecol Econ. 2000;33:457–72.

Schneider SH. Abrupt non-linear climate change, irreversibility and surprise. Glob Environ Change. 2004;14:245–58.

Steffen W, Grinevald J, Crutzen P, McNeill J. The anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 1938;2011(369):842–67.

Cash DW, Adger WN, Berkes F, Garden P, Lebel L, Olsson P, Pritchard L, Young O. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecol Soc. 2006;11:2.

Glaser M, Glaeser B. Towards a framework for cross-scale and multi-level analysis of coastal and marine social-ecological systems dynamics. Reg Environ Change. 2014;14:2039–52.

Wyborn C, Bixler RP. Collaboration and nested environmental governance: scale dependency, scale framing, and cross-scale interactions in collaborative conservation. J Environ Manage. 2013;123:58–67.

Kirschke S, Newig J. Addressing complexity in environmental management and governance. Sustain Sci. 2017;9:983.

Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan K, Christie P, Clark DA, Cullman G, Curran D, Durbin TJ, Epstein G, et al. Conservation social science: understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol Cons. 2017;205:93–108.

Hicks C. Interdisciplinarity in the environmental sciences: barriers and frontiers. Environ Conserv. 2010;37(4):464–77.

Mace GM. Whose conservation? Science. 2014;345:1558–60.

Rust NA, Abrams A, Challender DWS, Chapron G, Ghoddousi A, Glikman JA, Gowan CH, Hughes C, Rastogi A, Said A, et al. Quantity does not always mean quality: the importance of qualitative social science in conservation research. Soc Nat Resour. 2017;30(10):1304–10.

Schweizer VJ, Kriegler E. Improving environmental change research with systematic techniques for qualitative scenarios. Environ Res Lett. 2012;7(4):44011–44011.

Cook CN, Possingham HP, Fuller RA. Contribution of systematic reviews to management decisions. Conserv Biol. 2013;27(5):902–15.

Pluye P, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I. Opening-up the definition of systematic literature review: the plurality of worldviews, methodologies and methods for reviews and syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:2–5.

Petticrew M. Time to rethink the systematic review catechism? Moving from ‘what works’ to ‘what happens’. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–6.

Jackson RL, Drummond DK, Camara S. What is qualitative research? Qual Res Rep Commun. 2007;8(1):21–8.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, Van Der Wilt GJ, Mozygemba K, Refolo P, Sacchini D, Tummers M, Rehfuess E. Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventions [Online]. 2016. Available from: http://www.integrate-hta.eu/downloads/ . Accessed 1 Oct 2018.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):28–28.

Thomas J, O’Mara-Eves A, Harden A, Newman M. Chapter 8: Synthesis methods for combining and configuring textual or mixed methods data. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, editors. An Introduction to systematic reviews. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2017.

Andrews T. What is social constructionism? Grounded Theory Rev. 2012;11:39–46.

Hannes K, Harden A. Multi-context versus context-specific qualitative evidence syntheses: combining the best of both. Res Synth Methods. 2012;2(4):271–8.

Hannes K, Macaitis K. A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: update on a review of published papers. Qual Res. 2012;12(4):402–42.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53.

Dixon-Woods M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Med. 2011;9:9–39.

Lorenc T, Brunton G, Oliver S, Oliver K, Oakley A. Attitudes to walking and cycling among children, young people and parents: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:852–7.

Oliver S, Rees RW, Clarke-Jones L, Milne R, Oakley A, Gabbay J, Stein K, Buchanan P, Gyte G. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analyzing public involvement in health services research. Heal Expect. 2008;11:72–84.

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:29–37.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman AM, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2002.

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J. “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:37.

Belluco S, Gallocchio F, Losasso C, Ricci A. State of art of nanotechnology applications in the meat chain: a qualitative synthesis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;3:1084–96.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45–45.

Schirmer J, Berry H, O’Brien L. Healthier land, healthier farmers: considering the potential of natural resource management as a place-focused farmer health intervention. Health Place. 2013;24:97–109.

Haddaway N, McConville J, Piniewski M. How is the term ‘ecotechnology’ used in the research literature? A systematic review with thematic synthesis. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol. 2018;18:247–61.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies, vol. 11. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1988.

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:209–15.

Garside R, Britten N, Stein K. The experience of heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63:550–62.

Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, Yardley L, Pope C, Daker-White G, Campbell R. Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:133–55.

Head L, Gibson C, Gill N, Carr C, Waitt G. A meta-ethnography to synthesise household cultural research for climate change response. Local Environ. 2016;21:1467–81.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, Riley R. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35.

Eaves Y. A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:654–63.

Kearney M. Ready-to-wear: discovering grounded formal theory. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:179–86.

Hannes K, Lockwood M, editors. Synthesizing qualitative research: Choosing the right approach. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

Kangasniemi M, Kallio H, Pietilä A-M. Towards environmentally responsible nursing: a critical interpretive synthesis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:1465–78.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review: a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34.

McLain R, Lawry S, Ojanen M. Fisheries’ property regimes and environmental outcomes: a realist synthesis review. World Dev. 2018;102:213–27.

Nilsson D, Baxter G, Butler JRA, McAlpine CA. How do community-based conservation programs in developing countries change human behaviour? A realist synthesis. Biol Conserv. 2016;200:93–103.

Booth A. Chapter 15: qualitative evidence synthesis. In: Facey K, Ploug Hansen H, Single A, editors. Patient involvement in health technology assessment. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2017. p. 187–99.

Chapter Google Scholar

Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:365–71.

Dixon-Woods M, Booth A, Sutton AJ. Synthesizing qualitative research: a review of published reports. Qual Res. 2007;7(3):375–422.

Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(2):149–54.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Sandy O, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS. ROSES RepOrting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ Evid. 2018;7(1):7.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013;11:21.

France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, Uny I, Duncan EAS, Jepson RG, Maxwell M, Roberts RJ, Turley RL, Booth A, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:25.

Haddaway NR, Macura B. The role of reporting standards in producing robust literature reviews. Nat Clim Change. 2018;8:444–7.

Heyvaert M, Maes B, Onghena P. Mixed methods research synthesis: definition, framework, and potential. Qual Quant. 2013;47:659–76.

Jimenez E, Waddington H, Goel N, Prost A, Pullin AS, White H, Lahiri S, Narain A. Mixing and matching: using qualitative methods to improve quantitative impact evaluations (IEs) and systematic reviews (SRs) of development outcomes. J Dev Effect. 2018;10:400–21.

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch. 2006;13:29.

Heath G, Brownson R, Kruger J, Miles R, Powell K, Ramsey L. Task Force on Community Preventive Services: the effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review. J Phys Activity Health. 2006;3:S55–76.

Oya C, Schaefer F, Skalidou D, McCosker C, Langer L. Effects of certification schemes for agricultural production on socio-economic outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2017;3:346. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.3 .

Whear R, Thompson Coon J, Bethel A, Abbott R, Stein K, Garside R. What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental well-being of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Post-Acute Long-Term Care Med. 2014;15:697–705.

Pullin AS, Bangpan M, Dalrymple S, Dickson K, Haddaway NR, Healey JR, Hauari H, Hockley N, Jones JPG, Knight T, et al. Human well-being impacts of terrestrial protected areas. Environ Evid. 2013;2(1):19.

Westgate MJ, Haddaway NR, Cheng SH, McIntosh EJ, Marshall C, Lindenmayer DB. Software support for environmental evidence synthesis. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2(4):588–90.

Garside R. A comparison of methods for the systematic review of qualitative research: two examples using meta-ethnography and meta-study. Doctoral dissertation. Exeter: Universities of Exeter and Plymouth; 2008.

Brunton G, Oliver S, Oliver K, Lorenc T. A synthesis of research addressing children’s, young people’s and parents’ views of walking and cycling for transport. In. London, UK: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2006.

Benoot C, Hannes K, Bilsen J. The use of purposeful sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: a worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:21.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the BONUS Secretariat for covering article processing fees. BM thanks to Mistra Council for Evidence-based Environmental Management (EviEM) and BONUS RETURN for allocated time to draft this manuscript. RG is partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula.

Article processing fees were covered by BONUS RETURN. BONUS RETURN project is supported by BONUS (Art 185), funded jointly by the EU and Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research FORMAS, Sweden’s innovation agency VINNOVA, Academy of Finland and National Centre for Research and Development in Poland.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm Environment Institute, 87D Linnégatan, 10451, Stockholm, Sweden

Biljana Macura

Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Kreutzwaldi 5, 51006, Tartu, Estonia

Monika Suškevičs

European Centre for Environment and Human Health, University of Exeter Medical School, Truro, UK

Ruth Garside

Social Research Methodology Group, Faculty of Social Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Karin Hannes

EPPI-Centre, Department of Social Science, UCL Institute of Education, London, UK

Rebecca Rees

School of Natural Sciences, Technology and Environmental Studies, Södertörn University, 14189, Huddinge, Sweden

Romina Rodela

Laboratory of Geo-Information Science and Remote Sensing, Wageningen University, 6708 PB, Wageningen, The Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BM and MS developed the framework for and edited the end version of this paper. All authors (BM, MS, RG, KH, R. Rees and R. Rodela) wrote substantial pieces of the manuscript. RG, KH, R. Rees and R. Rodela commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Biljana Macura .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Macura, B., Suškevičs, M., Garside, R. et al. Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence for environmental policy and management: an overview of different methodological options. Environ Evid 8 , 24 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-019-0168-0

Download citation

Received : 23 November 2018

Accepted : 28 May 2019

Published : 13 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-019-0168-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Critical interpretative synthesis

- Mixed methods reviews

- Qualitative evidence synthesis

Environmental Evidence

ISSN: 2047-2382

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Environment and Resources

Volume 48, 2023, review article, open access, advances in qualitative methods in environmental research.

- Holly Caggiano 1 , and Elke U. Weber 2

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychology and Public Affairs, Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 48:793-811 (Volume publication date November 2023) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-112321-080106

- First published as a Review in Advance on April 11, 2023

- Copyright © 2023 by the author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See credit lines of images or other third-party material in this article for license information

Qualitative research methods examine a wide range of topics in the study of environment and resource management. This first review on the topic highlights innovative and impactful research over the past few decades, drawing from social science disciplines that include sociology, geography, anthropology, political science, public policy, and psychology. We describe qualitative research methods that have addressed five scientific goals: ( a ) describing what the world is like, ( b ) predicting what the world can be like, ( c ) acknowl-edging researcher positionality and reflexivity and diversifying ways of knowing in theorizing and research designs, ( d ) integrating imaginaries into empirical research and building narratives to make sense of possible futures and to broaden our view of scientific inquiry, and ( e ) helping scholars grapple with the deep complexity of socioecological systems. As we explore these themes, we explain foundational qualitative approaches and highlight examples of environmental qualitative research that apply them.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- 1. Bercht AL. 2021 . How qualitative approaches matter in climate and ocean change research: uncovering contradictions about climate concern. Glob. Environ. Change 70 : 102326 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ritchie J , Lewis J , Nicholls CM , Ormston R. 2013 . Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers London: SAGE [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahoney J , Goertz G. 2006 . A tale of two cultures: contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Polit. Anal. 14 : 3 227– 49 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seamon D , Gill HK. 2016 . Qualitative approaches to environment-behavior research. Research Methods for Environmental Psychology , ed. R Gifford 115– 35 . Chichester, UK: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerring J. 2012 . Mere description. . Br. J. Polit. Sci. 42 : 4 721– 46 [Google Scholar]

- 6. King G , Keohane RO , Verba S. 1994 . Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brady HE , Collier D. 2010 . Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield [Google Scholar]

- 8. George AL , Bennett A. 2005 . Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gerring J. 2017 . Qualitative methods. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 20 : 15– 36 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haverland M. 2010 . Conceiving and designing political science research: perspectives from Europe. Eur. Polit. Sci. 9 : 4 488– 94 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flyvbjerg B. 2001 . Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How it Can Succeed Again Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lincoln YS , Guba EG. 1985 . . Naturalistic Inquiry Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yin RK. 2018 . Case Study Research and Applications London: SAGE: [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maxwell JA. 2021 . Why qualitative methods are necessary for generalization. Qual. Psychol. 8 : 1 111– 18 [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Neill K , Weinthal E , Marion Suiseeya KR , Bernstein S , Cohn A et al. 2013 . Methods and global environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 38 : 441– 71 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stake RE. 1995 . The Art of Case Study Research London: SAGE [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schelly C. 2016 . Understanding energy practices: a case for qualitative research. Soc. Nat. Resour. 29 : 6 744– 49 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown P. 2003 . Qualitative methods in environmental health research. Environ. Health Perspect. 111 : 14 1789– 98 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Erikson K. 1976 . Everything in Its Path New York: Simon & Schuster [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ford JD , Keskitalo ECH , Smith T , Pearce T , Berrang-Ford L et al. 2010 . Case study and analogue methodologies in climate change vulnerability research. WIREs Clim. Change 1 : 3 374– 92 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skocpol T 1984 . Strategies in historical sociology. Vision and Method in Historical Sociology , ed. T Skocpol 356– 91 . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huntington HP. 2000 . Using Traditional Ecological Knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecol. Appl. 10 : 5 1270– 74 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weinthal E. 2002 . State Making and Environmental Cooperation: Linking Domestic and International Politics in Central Asia Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sullivan R , Gouldson A. 2017 . The governance of corporate responses to climate change: an international comparison. Bus. Strategy Environ. 26 : 4 413– 25 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ostrom E. 1990 . Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action Dallas, TX: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1st ed.. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mohai P , Pellow D , Roberts JT. 2009 . Environmental justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34 : 405– 30 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rudel TK. 2008 . Meta-analyses of case studies: a method for studying regional and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 18 : 1 18– 25 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rudel T. 2005 . Tropical Forests: Regional Paths of Destruction and Regeneration in the Late Twentieth Century New York: Columbia Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bennett A , Checkel JT. 2015 . Process Tracing Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beach D , Pedersen RB. 2019 . Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines Ann Arbor: Univ. Mich. Press [Google Scholar]

- 31. Motta MJ. 2018 . Policy diffusion and directionality: tracing early adoption of offshore wind policy. Rev. Policy Res. 35 : 3 398– 421 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stokes LC. 2020 . Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samper JA , Schockling A , Islar M. 2021 . Climate politics in green deals: exposing the political frontiers of the European Green Deal. Polit. Gov. 9 : 2 8– 16 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Orach K , Schlüter M , Österblom H. 2017 . Tracing a pathway to success: how competing interest groups influenced the 2013 EU Common Fisheries Policy reform. Environ. Sci. Policy 76 : 90– 102 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maskey S. 2022 . Using process tracing to evaluate stakeholder disputes: the case of tender award dispute in Nepal's forestry. Asian J. Comp. Polit. 7 : 4 907– 21 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baird J , Schultz L , Plummer R , Armitage D , Bodin Ö. 2019 . Emergence of collaborative environmental governance: What are the causal mechanisms?. Environ. Manag 63 : 1 16– 31 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ide T. 2017 . Research methods for exploring the links between climate change and conflict. WIREs Clim. Change 8 : 3 e456 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muradova L , Walker H , Colli F. 2020 . Climate change communication and public engagement in interpersonal deliberative settings: evidence from the Irish citizens’ assembly. Clim. Policy 20 : 10 1322– 35 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baggio JA , Barnett A , Perez-Ibarra I , Brady U , Ratajczyk E et al. 2016 . Explaining success and failure in the commons: the configural nature of Ostrom's institutional design principles. Int. J. Commons 10 : 2 417– 39 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pahl-Wostl C , Knieper C. 2014 . The capacity of water governance to deal with the climate change adaptation challenge: using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to distinguish between polycentric, fragmented and centralized regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 29 : 139– 54 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kirchherr J , Charles KJ , Walton MJ. 2016 . Multi-causal pathways of public opposition to dam projects in Asia: a fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Glob. Environ. Change 41 : 33– 45 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bretthauer JM. 2015 . Conditions for peace and conflict: applying a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis to cases of resource scarcity. J. Confl. Resolut. 59 : 4 593– 616 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mapfumo P , Adjei-Nsiah S , Mtambanengwe F , Chikowo R , Giller KE. 2013 . Participatory action research (PAR) as an entry point for supporting climate change adaptation by smallholder farmers in Africa. Environ. Dev. 5 : 6– 22 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haraway D. 1988 . Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 14 : 3 575– 99 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hausermann H , Adomako J. 2022 . Positionality, ‘the field,’ and implications for knowledge production and research ethics in land change science. J. Land Use Sci. 17 : 1 211– 25 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boyce P , Bhattacharyya J , Linklater W. 2021 . The need for formal reflexivity in conservation science. Conserv. Biol. 36 : 2 e13840 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ross A , Van Alstine J , Cotton M , Middlemiss L. 2021 . Deliberative democracy and environmental justice: evaluating the role of citizens’ juries in urban climate governance. Local Environ 26 : 12 1512– 31 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rose G. 1997 . Situating knowledges: positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 21 : 3 305– 20 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Joa B , Winkel G , Primmer E. 2018 . The unknown known—a review of local ecological knowledge in relation to forest biodiversity conservation. Land Use Policy 79 : 520– 30 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Middlemiss L , Gillard R. 2015 . Fuel poverty from the bottom-up: characterising household energy vulnerability through the lived experience of the fuel poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 6 : 146– 54 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soler M , Gómez A. 2020 . A citizen's claim: science with and for society. Qual. Inq. 26 : 8–9 943– 47 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frantzeskaki N , Kabisch N. 2016 . Designing a knowledge co-production operating space for urban environmental governance—lessons from Rotterdam, Netherlands and Berlin, Germany. Environ. Sci. Policy 62 : 90– 98 [Google Scholar]

- 53. McIntyre A. 2007 . Participatory Action Research London: SAGE [Google Scholar]

- 54. Godden NJ , Macnish P , Chakma T , Naidu K. 2020 . Feminist Participatory Action Research as a tool for climate justice. Gend. Dev. 28 : 3 593– 615 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reitan R , Gibson S. 2012 . Climate change or social change? Environmental and leftist praxis and participatory action research. Globalizations 9 : 3 395– 410 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nussey C , Frediani AA , Lagi R , Mazutti J , Nyerere J. 2022 . Building university capabilities to respond to climate change through participatory action research: towards a comparative analytical framework. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 23 : 1 95– 115 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mijin Cha J , Stevis D , Vachon TE , Price V , Brescia-Weiler M 2022 . A Green New Deal for all: the centrality of a worker and community-led just transition in the US. Polit. Geogr. 95 : 102594 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Calvert K , Jahns R. 2021 . Participatory mapping and spatial planning for renewable energy development: the case of ground-mount solar in rural Ontario. Can. Plan. Policy Aménage Polit. Can. 2021 : 89– 100 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Constantino SM , Weber EU. 2021 . Decision-making under the deep uncertainty of climate change: the psychological and political agency of narratives. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 42 : 151– 59 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Taylor C. 2002 . Modern social imaginaries. Public Cult . 14 : 1 91– 124 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jasanoff S. 2010 . A new climate for society. Theory Cult. Soc. 27 : 2–3 233– 53 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Deubelli TM , Mechler R. 2021 . Perspectives on transformational change in climate risk management and adaptation. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 : 5 053002 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fenton-O'Creevy M , Tuckett D. 2022 . Selecting futures: the role of conviction, narratives, ambivalence, and constructive doubt. Futures Foresight Sci . 4 : e111 [Google Scholar]

- 64. O'Neill BC , Kriegler E , Ebi KL , Kemp-Benedict E , Riahi K et al. 2017 . The roads ahead: narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42 : 169– 80 [Google Scholar]

- 65. Carrington D. 2019 . Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment. The Guardian May 17. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changing-the-language-it-uses-about-the-environment [Google Scholar]

- 66. Weber EU , Ames DR , Blais A-R. 2005 . ‘ How do I choose thee? Let me count the ways’: a textual analysis of similarities and differences in modes of decision-making in China and the United States. Manag. Organ. Rev. 1 : 1 87– 118 [Google Scholar]

- 67. Whiteley A , Chiang A , Einsiedel E. 2016 . Climate change imaginaries? Examining expectation narratives in cli-fi novels. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 36 : 1 28– 37 [Google Scholar]

- 68. Robinson KS. 2020 . The Ministry for the Future London: Orbit [Google Scholar]

- 69. Roanhorse R. 2018 . Trail of Lightning New York: Simon & Schuster [Google Scholar]

- 70. Powers R. 2018 . The Overstory New York: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Machin A. 2022 . Climates of democracy: skeptical, rational, and radical imaginaries. WIREs Clim. Change 13 : 4 e774 [Google Scholar]

- 72. Haraway DJ. 2016 . Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene . Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mourik RM , Sonetti G , Robison RAV. 2021 . The same old story—or not? How storytelling can support inclusive local energy policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 73 : 101940 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosa AB , Kimpeler S , Schirrmeister E , Warnke P. 2021 . Participatory foresight and reflexive innovation: setting policy goals and developing strategies in a bottom-up, mission-oriented, sustainable way. Eur. J. Futur. Res. 9 : 1 2 [Google Scholar]

- 75. Caggiano H , Landau LF , Campbell LK , Johnson ML , Svendsen ES. 2022 . Civic stewardship and urban climate governance: opportunities for transboundary planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res . In press. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221104010 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tsing AL. 2015 . The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ogden LA , Aoki C , Grove JM , Sonti NF , Hall W et al. 2019 . Forest ethnography: an approach to study the environmental history and political ecology of urban forests. Urban Ecosyst 22 : 1 49– 63 [Google Scholar]

- 78. Albuquerque UP , Alves AGC. 2016 . What is ethnobiology?. Introduction to Ethnobiology UP Albuquerque, RR Nóbrega Alves 3– 7 . Cham, Switz.: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li X , Junqueira AB , Reyes-García V. 2021 . At the crossroad of emergency: ethnobiology, climate change, and Indigenous Peoples and local communities. J. Ethnobiol. 41 : 3 307– 12 [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gillespie KA. 2019 . For a politicized multispecies ethnography: reflections on a feminist geographic pedagogical experiment. Polit. Anim. 5 : 17– 32 [Google Scholar]

- 81. Watson MC. 2016 . On multispecies mythology: a critique of animal anthropology italic Theory Cult. Soc 33 5 159– 72 [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schlüter M , Orach K , Lindkvist E , Martin R , Wijermans N et al. 2019 . Toward a methodology for explaining and theorizing about social-ecological phenomena. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 39 : 44– 53 [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nature Climate Change 2021 . Powers of qualitative research. Nat. Clim. Change 11 : 9 717– 17 [Google Scholar]

- 84. Moon K , Brewer TD , Januchowski-Hartley SR , Adams VM , Blackman DA. 2016 . A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals. Ecol. Soc. 21 : 3 17 [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gear C , Eppel E , Koziol-McLain J. 2018 . Advancing complexity theory as a qualitative research methodology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 17 : https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918782557 [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bagstad KJ , Semmens DJ , Waage S , Winthrop R 2013 . A comparative assessment of decision-support tools for ecosystem services quantification and valuation. Ecosyst. Serv. 5 : 27– 39 [Google Scholar]

- 87. Supran G , Oreskes N. 2017 . Assessing ExxonMobil's climate change communications (1977–2014). Environ. Res. Lett. 12 : 8 084019 [Google Scholar]

- 88. Supran G , Oreskes N. 2020 . Addendum to ‘Assessing ExxonMobil's climate change communications (1977–2014)’ Supran and Oreskes (2017 Environ . Res. Lett . 12 084019). Environ. Res. Lett. 15 : 11 119401 [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fisher DR , Waggle J , Leifeld P. 2013 . Where does political polarization come from? Locating polarization within the U.S. climate change debate. Am. Behav. Sci. 57 : 1 70– 92 [Google Scholar]

- 90. Markard J , Rinscheid A , Widdel L. 2021 . Analyzing transitions through the lens of discourse networks: coal phase-out in Germany. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 40 : 315– 31 [Google Scholar]

- 91. Derr V , Simons J. 2020 . A review of photovoice applications in environment, sustainability, and conservation contexts: Is the method maintaining its emancipatory intents?. Environ. Educ. Res. 26 : 3 359– 80 [Google Scholar]

- 92. Russo S , Hissa K , Murphy B , Gunson B. 2021 . Photovoice, emergency management and climate change: a comparative case-study approach. Qual. Res. 21 : 4 568– 85 [Google Scholar]

- 93. Murray L , Järviluoma H. 2020 . Walking as transgenerational methodology. Qual. Res. 20 : 2 229– 38 [Google Scholar]

- 94. Shepherd N. 2023 . Walking as embodied research: coloniality, climate change, and the ‘arts of noticing.’. Sci. Technol. Soc. 28 : 1 58– 67 [Google Scholar]

- 95. Caggiano H , Landau LF. 2021 . A new framework for imagining the climate commons? The case of a Green New Deal in the US. Plan. Theory 21 : 4 380– 402 [Google Scholar]

- 96. Macura B , Suškevičs M , Garside R , Hannes K , Rees R , Rodela R 2019 . Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence for environmental policy and management: an overview of different methodological options. Environ. Evid. 8 : 1 24 [Google Scholar]

- 97. Nielsen JØ , D'haen SAL. 2014 . Asking about climate change: reflections on methodology in qualitative climate change research published in Global Environmental Change since 2000. Glob. Environ. Change 24 : 402– 9 [Google Scholar]

- 98. Alexander SM , Jones K , Bennett NJ , Budden A , Cox M et al. 2020 . Qualitative data sharing and synthesis for sustainability science. Nat. Sustain. 3 : 2 81– 88 [Google Scholar]

- 99. Fisher DR. 2019 . The broader importance of #FridaysForFuture. Nat. Clim. Change 9 : 6 430– 31 [Google Scholar]

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month