General Nursing Research Guide

- Synonyms, Related Terms and Boolean Operators

- Boolean Operators and Modifiers

- Linfield Library Catalog

- Finding Quantitative, Qualitative, Primary and Secondary Sources

- Evaluating Sources

Quantitative and Qualitative

- What is Quantitative and Qualitative Research?

Quantitative research is a methodology that relies on the exploration of numerical patterns, and it can be precisely measured. Using scientific inquiry, quantitative research relies on data that are observed or measured to examine research questions. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), Systematic Reviews, and Meta-Analysis are all examples of Quantitative research.

Qualitative research refers to any research based on something that is impossible to accurately and precisely measure. It focuses on the "why" rather than the "what" and relies on the direct experiences of human beings as meaning-making agents in their every day lives. Case studies, Ethnography, Grounded Theory, Narrative Studies or Focus Groups , are all examples of Qualitative research.

- Finding Quantitative and Qualitative Research in PubMed and CINAHL?

The best way to find quantitative and/or qualitative articles in either PubMed or CINAHL is to search by publication type.

For quantitative articles, select Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), Systematic Reviews, or Meta-Analysis in either CINAHL or PubMed.

For qualitative, search for Case Studies, Observational, Personal Narratives in PubMed , and Anecdote, Case Study, Editorial, Interview, Meta Synthesis in CINAHL .

You can also search both PubMed and CINAHL using 'quantitive' or 'qualitative' as part of your keyword search, but it's usually more effective to look for a specific publication type.

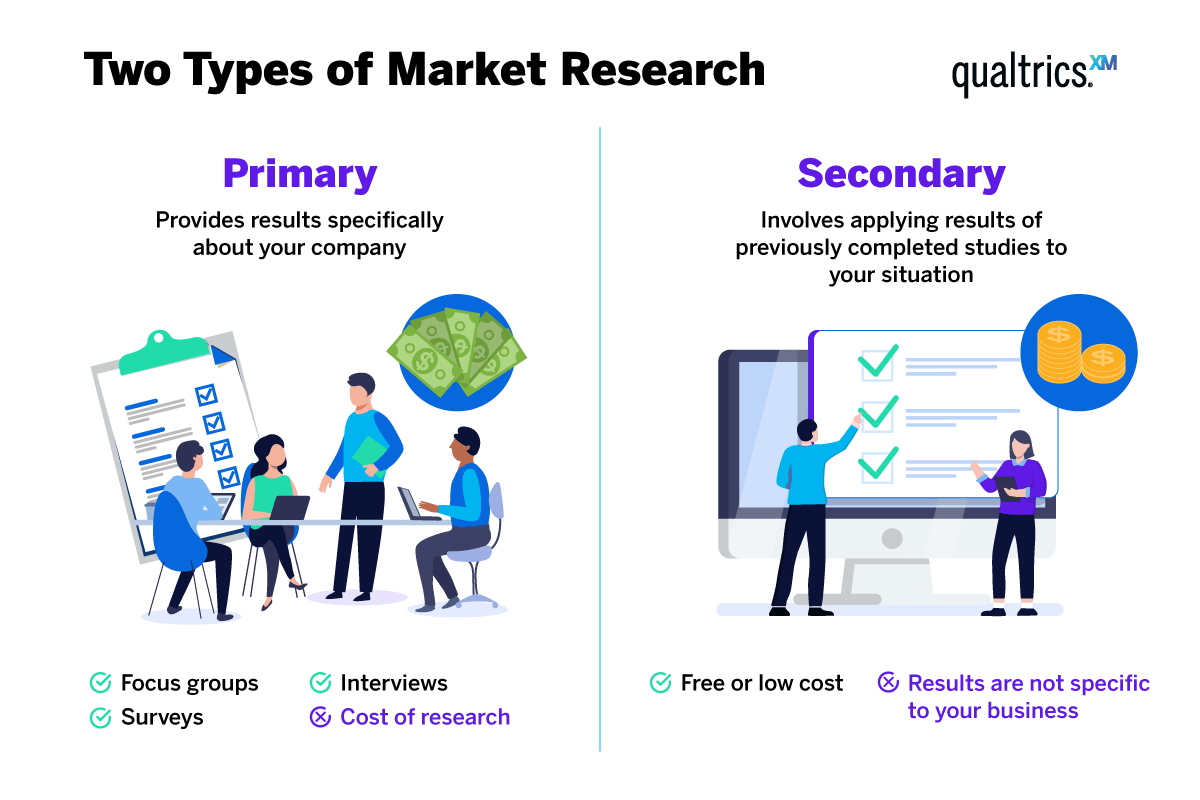

Primary and Secondary Research

- What is Primary Research?

Primary research in nursing is one that reports the original findings of a study or experiment. It is usually written by the person(s) conducting the research, and is often found in peer reviewed journals.

Sources of primary research include:

Case studies

Clinical trials or randomized clinical trials (RCT)

Cohort studies

Dissertations or theses

Survey research

- What is Secondary Research?

S econdary Research is one that summarizes, synthesizes or comments on original research. The Author(s) describe research done by others.

Sources of secondary research include:

Clinical practice guidelines

Meta-analysis

Patient education material

Reviews of literature

Systematic reviews

- Finding Primary Research in PubMed and CINAHL

To find primary research in PubMed and CINAHL, you'll need to filter by article type. Trying searching for Clinical Trials, Randomized Controlled Trials, or Case Study/Reports in either database to find primary research.

- << Previous: PUBMED

- Next: Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 10:15 AM

- URL: https://linfield.libguides.com/generalnursingguide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.10(4); May-Jun 2019

Secondary Analysis Research

In secondary data analysis (SDA) studies, investigators use data collected by other researchers to address different questions. Like primary data researchers, SDA investigators must be knowledgeable about their research area to identify datasets that are a good fit for an SDA. Several sources of datasets may be useful for SDA, and examples of some of these will be discussed. Advanced practice providers must be aware of possible advantages, such as economic savings, the ability to examine clinically significant research questions in large datasets that may have been collected over time (longitudinal data), generating new hypotheses or clarifying research questions, and avoiding overburdening sensitive populations or investigating sensitive areas. When reading an SDA report, the reader should be able to determine that the authors identified the limitation or disadvantages of their research. For example, a primary dataset cannot “fit” an SDA researcher’s study exactly, SDAs are inherently limited by the inability to definitively examine causality given their retrospective nature, and data may be too old to address current issues.

Secondary analysis of data collected by another researcher for a different purpose, or SDA, is increasing in the medical and social sciences. This is not surprising, given the immense body of health care–related research performed worldwide and the potential beneficial clinical implications of the timely expansion of primary research ( Johnston, 2014 ; Tripathy, 2013 ). Oncology advanced practitioners should understand why and how SDA studies are done, their potential advantages and disadvantages, as well as the importance of reading primary and secondary analysis research reports with the same discriminatory, evaluative eye for possible applicability to their practice setting.

To perform a primary research study, an investigator identifies a problem or question in a particular population that is amenable to the study, designs a research project to address that question, decides on a quantitative or qualitative methodology, determines an adequate sample size and recruits representative subjects, and systematically collects and analyzes data to address specific research questions. On the other hand, an SDA addresses new questions from that dataset previously gathered for a different primary study ( Castle, 2003 ). This might sound “easier,” but investigators who carry out SDA research must have a broad knowledge base and be up to date regarding the state of the science in their area of interest to identify important research questions, find appropriate datasets, and apply the same research principles as primary researchers.

Most SDAs use quantitative data, but some qualitative studies lend themselves to SDA. The researcher must have access to source data, as opposed to secondary source data (e.g., a medical record review). Original qualitative data sources could be videotaped or audiotaped interviews or transcripts, or other notes from a qualitative study ( Rew, Koniak-Griffin, Lewis, Miles, & O’Sullivan, 2000 ). Another possible source for qualitative analysis is open-ended survey questions that reflect greater meaning than forced-response items.

SECONDARY ANALYSIS PROCESS

An SDA researcher starts with a research question or hypothesis, then identifies an appropriate dataset or sets to address it; alternatively, they are familiar with a dataset and peruse it to identify other questions that might be answered by the available data ( Cheng & Phillips, 2014 ). In reality, SDA researchers probably move back and forth between these approaches. For example, an investigator who starts with a research question but does not find a dataset with all needed variables usually must modify the research question(s) based on the best available data.

Secondary data analysis researchers access primary data via formal (public or institutional archived primary research datasets) or informal data sharing sources (pooled datasets separately collected by two or more researchers, or other independent researchers in carrying out secondary analysis; Heaton, 2008 ). There are numerous sources of datasets for secondary analysis. For example, a graduate student might opt to perform a secondary analysis of an advisor’s research. University and government online sites may also be useful, such as the NYU Libraries Data Sources ( https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=276966&p=1848686 ) or the National Cancer Institute, which has many subcategories of datasets ( https://www.cancer.gov/research/resources/search?from=0&toolTypes=datasets_databases ). The Google search engine is useful, and researchers can enter the search term “Archive sources of datasets (add key words related to oncology).”

In one secondary analysis method, researchers reuse their own data—either a single dataset or combined respective datasets to investigate new or additional questions for a new SDA.

Example of a Secondary Data Analysis

An example highlighting this method of reusing one’s own data is Winters-Stone and colleagues’ SDA of data from four previous primary studies they performed at one institution, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO) in 2017. Their pooled sample was 512 breast cancer survivors (age 63 ± 6 years) who had been diagnosed and treated for nonmetastatic breast cancer 5.8 years (± 4.1 years) earlier. The investigators divided the cohort, which had no diagnosed neurologic conditions, into two groups: women who reported symptoms consistent with lower-extremity chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN; numbness, tingling, or discomfort in feet) vs. CIPN-negative women who did not have symptoms. The objectives of the study were to define patient-reported prevalence of CIPN symptoms in women who had received chemotherapy, compare objective and subjective measures of CIPN in these cancer survivors, and examine the relationship between CIPN symptom severity and outcomes. Objective and subjective measures were used to compare groups for manifestations influenced by CIPN (physical function, disability, and falls). Actual chemotherapy regimens administered had not been documented (a study limitation, but regimens likely included a taxane that is neurotoxic); therefore, investigators could only confirm that symptoms began during chemotherapy and how severely patients rated symptoms.

Up to 10 years after completing chemotherapy, 47% of women who had received chemotherapy were still having significant and potentially life-threatening sensory symptoms consistent with CIPN, did worse on physical function tests, reported poorer functioning, had greater disability, and had nearly twice the rate of falls compared with CIPN-negative women ( Winters-Stone et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, symptom severity was related to worse outcomes, while worsening cancer was not.

Stout (2017) recognized the importance of this secondary analysis in an accompanying editorial published in JCO, remarking that it was the first study that included both patient-reported subjective measures and objective measures of a clinically significant problem. Winter-Stone and others (2017) recognized that by analyzing what essentially became a large sample, they were able to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the significance and impact of CIPN, and thus to challenge the notion that while CIPN may improve over time, it remains a major cancer survivorship issue. Thus, oncology advanced practitioners must systematically address CIPN at baseline and over time in vulnerable patients, and collaborate with others to implement potentially helpful interventions such as physical and occupational therapy ( Silver & Gilchrist, 2011 ). Other primary or secondary research projects might focus on the usefulness of such interventions.

ADVANTAGES OF SECONDARY DATA ANALYSIS

The advantages of doing SDA research that are cited most often are the economic savings—in time, money, and labor—and the convenience of using existing data rather than collecting primary data, which is usually the most time-consuming and expensive aspect of research ( Johnston, 2014 ; Rew et al., 2000 ; Tripathy, 2013 ). If there is a cost to access datasets, it is usually small (compared to performing the data collection oneself), and detailed information about data collection and statistician support may also be available ( Cheng & Phillips, 2014 ). Secondary data analysis may help a new investigator increase his/her clinical research expertise and avoid data collection challenges (e.g., recruiting study participants, obtaining large-enough sample sizes to yield convincing results, avoiding study dropout, and completing data collection within a reasonable time). Secondary data analyses may also allow for examining more variables than would be feasible in smaller studies, surveys of more diverse samples, and the ability to rethink data and use more advanced statistical techniques in analysis ( Rew et al., 2000 ).

Secondary Data Analysis to Answer Additional Research Questions

Another advantage is that an SDA of a large dataset, possibly combining data from more than one study or by using longitudinal data, can address high-impact, clinically important research questions that might be prohibitively expensive or time-consuming for primary study, and potentially generate new hypotheses ( Smith et al., 2011 ; Tripathy, 2013 ). Schadendorf and others (2015) did one such SDA: a pooled analysis of 12 phase II and phase III studies of ipilimumab (Yervoy) for patients with metastatic melanoma. The study goal was to more accurately estimate the long-term survival benefit of ipilimumab every 3 weeks for greater than or equal to 4 doses in 1,861 patients with advanced melanoma, two thirds of whom had been previously treated and one third who were treatment naive. Almost 89% of patients had received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg (n = 965), 10 mg/kg (n = 706), or other doses, and about 54% had been followed for longer than 5 years. Across all studies, overall survival curves plateaued between 2 and 3 years, suggesting a durable survival benefit for some patients.

Irrespective of prior therapy, ipilimumab dose, or treatment regimen, median overall survival was 13.5 months in treatment naive patients and 10.7 months in previously treated patients ( Schadendorf et al., 2015 ). In addition, survival curves consistently plateaued at approximately year 3 and continued for up to 10 years (longest follow-up). This suggested that most of the 20% to 26% of patients who reached the plateau had a low risk of death from melanoma thereafter. The authors viewed these results as “encouraging,” given the historic median overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma of 8 to 10 months and 5-year survival of approximately 10%. They identified limitations of their SDA (discussed later in this article). Three-year survival was numerically (but not statistically significantly) greater for the patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg than at 3 mg/kg doses, which had been noted in one of the included studies.

The importance of this secondary analysis was clearly relevant to prescribers of anticancer therapies, and led to a subsequent phase III trial in the same population to answer the ipilimumab dose question. Ascierto and colleagues’ (2017) study confirmed ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg led to a significantly longer overall survival than at 3 mg/kg (15.7 months vs. 11.5 months) in a subgroup of patients not previously treated with a BRAF inhibitor or immune checkpoint inhibitor. However, this was attained at the cost of greater treatment-related adverse events and more frequent discontinuation secondary to severe ipilimumab-related adverse events. Both would be critical points for advanced practitioners to discuss with patients and to consider in relationship to the particular patient’s ability to tolerate a given regimen.

Secondary Data Analysis to Avoid Study Repetition and Over-Research

Secondary data analysis research also avoids study repetition and over-research of sensitive topics or populations ( Tripathy, 2013 ). For example, people treated for cancer in the United Kingdom are surveyed annually through the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (NCPES), and questions regarding sexual orientation were first included in the 2013 NCPES. Hulbert-Williams and colleagues (2017) did a more rigorous SDA of this survey to gain an understanding of how lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) patients’ experiences with cancer differed from heterosexual patients.

Sixty-four percent of those surveyed responded (n = 68,737) to the question regarding their “best description of sexual orientation.” 89.3% indicated “heterosexual/straight,” 425 (0.6%) indicated “lesbian or gay,” and 143 (0.2%) indicated “bisexual.” One insight gained from the study was that although the true population proportion of LGB was not known, the small number of self-identified LGB patients most likely did not reflect actual numbers and may have occurred because of ongoing unwillingness to disclose sexual orientation, along with the older mean age of the sample. Other cancer patients who selected “prefer not to answer” (3%), “other” (0.9%), or left the question blank (6%), were not included in the SDA to correctly avoid bias in assuming these responses were related to sexual orientation.

Bisexual respondents were significantly more likely to report that nurses or other health-care professionals informed them about their diagnosis, but that it was subsequently difficult to contact nurse specialists and get understandable answers from them; they were dissatisfied with their interaction with hospital nurses and the care and help provided by both health and social care services after leaving the hospital. Bisexual and lesbian/gay respondents wanted to be involved in treatment decision-making, but therapy choices were not discussed with them, and they were all less satisfied than heterosexuals with the information given to them at diagnosis and during treatment and aftercare—an important clinical implication for oncology advanced practitioners.

Hulbert-Williams and colleagues (2017) proposed that while health-care communication and information resources are not explicitly homophobic, we may perpetuate heterosexuality as “normal” by conversational cues and reliance on heterosexual imagery that implies a context exclusionary of LGB individuals. Sexual orientation equality is about matching care to individual needs for all patients regardless of sexual orientation rather than treating everyone the same way, which does not seem to have happened according to the surveyed respondents’ perceptions. In addition, although LGB respondents replied they did not have or chose to exclude significant others from their cancer experience, there was no survey question that clarified their primary relationship status. This is not a unique strategy for persons with cancer, as LGB individuals may do this to protect family and friends from the negative consequences of homophobia.

Hulbert-Williams and others (2017) identified that this dataset might be useful to identify care needs for patients who identify as LGBT or LGBTQ (queer or questioning; no universally used acronym) and be used to obtain more targeted information from subsequent surveys. There is a relatively small body of data for advanced practitioners and other providers that aid in the assessment and care (including supportive, palliative, and survivorship care) of LGBT individuals—a minority group with many subpopulations that may have unique needs. One such effort is the white paper action plan that came out of the first summit on cancer in the LGBT communities. In 2014, participants from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada met to identify LGBT communities’ concerns and needs for cancer research, clinical cancer care, health-care policy, and advocacy for cancer survivorship and LGBT health equity ( Burkhalter et al., 2016 ).

More specifically, Healthy People 2020 now includes two objectives regarding LGBT issues: (1) to increase the number of population-based data systems used to monitor Healthy People 2020 objectives, including a standardized set of questions that identify lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations; and (2) to increase the number of states and territories that include questions that identify sexual orientation and gender identity on state-level surveys or data systems ( Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019 ). We should help each patient to designate significant others’ (family or friends) degree of involvement in care, while recognizing that LGB patients may exclude their significant others if this process involves disclosing sexual orientation, as this may lead to continued social isolation of cancer patients. This SDA by Hulbert-Williams and colleagues (2017) produced findings in a relatively unexplored area of the overall care experiences of LGB patients.

DISADVANTAGES OF SECONDARY DATA ANALYSIS

Many drawbacks of SDA research center around the fact that a primary investigator collected data reflecting his/her unique perspectives and questions, which may not fit an SDA researcher’s questions ( Rew et al., 2000 ). Secondary data analysis researchers have no control over a desired study population, variables of interest, and study design, and probably did not have a role in collecting the primary data ( Castle, 2003 ; Johnston, 2014 ; Smith et al., 2011 ).

Furthermore, the primary data may not include particular demographic information (e.g., respondent zip codes, race, ethnicity, and specific ages) that were deleted to protect respondent confidentiality, or some other different variables that might be important in the SDA may not have been examined at all ( Cheng & Phillips, 2014 ; Johnston, 2014 ). Although primary data collection takes longer than SDA data collection, identifying and procuring suitable SDA data, analyzing the overall quality of the data, determining any limitations inherent in the original study, and determining whether there is an appropriate fit between the purpose of the original study and the purpose of the SDA can be very time consuming ( Castle, 2003 ; Cheng & Phillips, 2014 ; Rew et al., 2000 ).

Secondary data analysis research may be limited to descriptive, exploratory, and correlational designs and nonparametric statistical tests. By their nature, SDA studies are observational and retrospective, and the investigator cannot examine causal relationships (by a randomized, controlled design). An SDA investigator is challenged to decide whether archival data can be shaped to match new research questions; this means the researcher must have an in-depth understanding of the dataset and know how to alter research questions to match available data and recoded variables.

For example, in their pooled analysis of ipilimumab for advanced melanoma, Schadendorf and colleagues (2015) recognized study limitations that might also be disadvantages of other SDAs. These included the fact that they could not make definitive conclusions about the relationship of survival to ipilimumab dose because the study was not randomized, had no control group, and could not account for key baseline prognostic factors. Other limitations were differences in patient populations in several studies included in the SDA, studies that had been done over 10 years ago (although no other new therapies had improved overall survival during that time), and the fact that treatments received after ipilimumab could have affected overall survival.

READING SECONDARY ANALYSIS RESEARCH

Primary and secondary data investigators apply the same research principles, which should be evident in research reports ( Cheng & Phillips, 2014 ; Hulbert-Williams et al., 2017 ; Johnston, 2014 ; Rew et al., 2000 ; Smith et al., 2011 ; Tripathy, 2013 ).

- ● Did the investigator(s) make a logical and convincing case for the importance of their study?

- ● Is there a clear research question and/or study goals or objectives?

- ● Are there operational definitions for the variables of interest?

- ● Did the authors acknowledge the source of the original data and acquire ethical approval (as necessary)?

- ● Did the authors discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the dataset? For example, how old are the data? Is the dataset sufficiently large to have confidence in the results (adequately powered)?

- ● How well do the data seem to “fit” the SDA research question and design?

- ● Does the methods section allow you, the reader, to “see” how the study was done (e.g., how the sample was selected, the tools/instruments that were used, as well their validity and reliability to measure what was intended, the data collection process, and how the data was analyzed)?

- ● Do the findings, discussion, and conclusions—positive or negative—allow you to answer the “So what?” question, and does your evaluation match the investigator’s conclusion?

Answering these questions allows the advanced practice provider reader to assess the possible value of a secondary analysis (similarly to a primary research) report and its applicability to practice, and to identify further issues or areas for scientific inquiry.

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Ascierto P. A., Del Vecchio M., Robert C., Mackiewicz A., Chiarion-Sileni V., Arance A.,…Maio M. (2017). Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg versus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial . Lancet Oncology , 18 ( 5 ), 611–622. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30231-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burkhalter J. E., Margolies L., Sigurdsson H. O., Walland J., Radix A., Rice D.,…Maingi S. (2016). The National LGBT Cancer Action Plan: A white paper of the 2014 National Summit on Cancer in the LGBT Communities . LGBT Health , 3 ( 1 ), 19–31. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0118 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Castle J. E. (2003). Maximizing research opportunities: Secondary data analysis . Journal of Neuroscience Nursing , 35 ( 5 ), 287–290. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14593941 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheng H. G., & Phillips M. R. (2014). Secondary analysis of existing data: Opportunities and implementation . Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry , 26 ( 6 ), 371–375. https://dx.doi.org/10.11919%2Fj.issn.1002-0829.214171 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heaton J. (2008). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: An overview . Historical Social Research , 33 ( 3 ), 33–45. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hulbert-Williams N. J., Plumpton C. O., Flowers P., McHugh R., Neal R. D., Semlyen J., & Storey L. (2017). The cancer care experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual patients: A secondary analysis of data from the UK Cancer Patient Experience Survey . European Journal of Cancer Care , 26 ( 4 ). 10.1111/ecc.12670 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnston M. P. (2014). Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come . Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML) , 3 , 619–626.r [ Google Scholar ]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health . Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Rew L., Koniak-Griffin D., Lewis M. A., Miles M., & O’Sullivan A. (2000). Secondary data analysis: New perspective for adolescent research . Nursing Outlook , 48 ( 5 ), 223–239. 10.1067/mno.2000.104901 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schadendorf D., Hodi F. S., Robert C., Weber J. S., Margolin K., Hamid O.,…Wolchok J. D. (2015). Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma . Journal of Clinical Oncology , 33 ( 17 ), 1889–1894. 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silver J. K., & Gilchrist L. S. (2011). Cancer rehabilitation with a focus on evidence-based outpatient physical and occupational therapy interventions . American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation , 90 ( 5 Suppl 1 ), S5–S15. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31820be4ae [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith A. K., Ayanian J. Z., Covinsky K. E., Landon B. E., McCarthy E. P., Wee C. C., & Steinman M. A. (2011). Conducting high-value secondary dataset analysis: An introductory guide and resources . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 26 ( 8 ), 920–929. 10.1007/s11606-010-1621-5 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stout N. L. (2017). Expanding the perspective on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy management . Journal of Clinical Oncology , 35 ( 23 ), 2593–2594. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6207 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tripathy J. P. (2013). Secondary data analysis: Ethical issues and challenges (letter) . Iranian Journal of Public Health , 42 ( 12 ), 1478–1479. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winters-Stone K. M., Horak F., Jacobs P. G., Trubowitz P., Dieckmann N. F., Stoyles S., & Faithfull S. (2017). Falls, functioning, and disability among women with persistent symptoms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy . Journal of Clinical Oncology , 35 ( 23 ) , 2604–2612. 10.1200/JCO.2016 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Secondary Research: Definition, Methods and Examples.

In the world of research, there are two main types of data sources: primary and secondary. While primary research involves collecting new data directly from individuals or sources, secondary research involves analyzing existing data already collected by someone else. Today we’ll discuss secondary research.

One common source of this research is published research reports and other documents. These materials can often be found in public libraries, on websites, or even as data extracted from previously conducted surveys. In addition, many government and non-government agencies maintain extensive data repositories that can be accessed for research purposes.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

While secondary research may not offer the same level of control as primary research, it can be a highly valuable tool for gaining insights and identifying trends. Researchers can save time and resources by leveraging existing data sources while still uncovering important information.

What is Secondary Research: Definition

Secondary research is a research method that involves using already existing data. Existing data is summarized and collated to increase the overall effectiveness of the research.

One of the key advantages of secondary research is that it allows us to gain insights and draw conclusions without having to collect new data ourselves. This can save time and resources and also allow us to build upon existing knowledge and expertise.

When conducting secondary research, it’s important to be thorough and thoughtful in our approach. This means carefully selecting the sources and ensuring that the data we’re analyzing is reliable and relevant to the research question . It also means being critical and analytical in the analysis and recognizing any potential biases or limitations in the data.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Secondary research is much more cost-effective than primary research , as it uses already existing data, unlike primary research, where data is collected firsthand by organizations or businesses or they can employ a third party to collect data on their behalf.

LEARN ABOUT: Data Analytics Projects

Secondary Research Methods with Examples

Secondary research is cost-effective, one of the reasons it is a popular choice among many businesses and organizations. Not every organization is able to pay a huge sum of money to conduct research and gather data. So, rightly secondary research is also termed “ desk research ”, as data can be retrieved from sitting behind a desk.

The following are popularly used secondary research methods and examples:

1. Data Available on The Internet

One of the most popular ways to collect secondary data is the internet. Data is readily available on the internet and can be downloaded at the click of a button.

This data is practically free of cost, or one may have to pay a negligible amount to download the already existing data. Websites have a lot of information that businesses or organizations can use to suit their research needs. However, organizations need to consider only authentic and trusted website to collect information.

2. Government and Non-Government Agencies

Data for secondary research can also be collected from some government and non-government agencies. For example, US Government Printing Office, US Census Bureau, and Small Business Development Centers have valuable and relevant data that businesses or organizations can use.

There is a certain cost applicable to download or use data available with these agencies. Data obtained from these agencies are authentic and trustworthy.

3. Public Libraries

Public libraries are another good source to search for data for this research. Public libraries have copies of important research that were conducted earlier. They are a storehouse of important information and documents from which information can be extracted.

The services provided in these public libraries vary from one library to another. More often, libraries have a huge collection of government publications with market statistics, large collection of business directories and newsletters.

4. Educational Institutions

Importance of collecting data from educational institutions for secondary research is often overlooked. However, more research is conducted in colleges and universities than any other business sector.

The data that is collected by universities is mainly for primary research. However, businesses or organizations can approach educational institutions and request for data from them.

5. Commercial Information Sources

Local newspapers, journals, magazines, radio and TV stations are a great source to obtain data for secondary research. These commercial information sources have first-hand information on economic developments, political agenda, market research, demographic segmentation and similar subjects.

Businesses or organizations can request to obtain data that is most relevant to their study. Businesses not only have the opportunity to identify their prospective clients but can also know about the avenues to promote their products or services through these sources as they have a wider reach.

Learn More: Data Collection Methods: Types & Examples

Key Differences between Primary Research and Secondary Research

Understanding the distinction between primary research and secondary research is essential in determining which research method is best for your project. These are the two main types of research methods, each with advantages and disadvantages. In this section, we will explore the critical differences between the two and when it is appropriate to use them.

| Research is conducted first hand to obtain data. Researcher “owns” the data collected. | Research is based on data collected from previous researches. |

| is based on raw data. | Secondary research is based on tried and tested data which is previously analyzed and filtered. |

| The data collected fits the needs of a researcher, it is customized. Data is collected based on the absolute needs of organizations or businesses. | Data may or may not be according to the requirement of a researcher. |

| Researcher is deeply involved in research to collect data in primary research. | As opposed to primary research, secondary research is fast and easy. It aims at gaining a broader understanding of subject matter. |

| Primary research is an expensive process and consumes a lot of time to collect and analyze data. | Secondary research is a quick process as data is already available. Researcher should know where to explore to get most appropriate data. |

How to Conduct Secondary Research?

We have already learned about the differences between primary and secondary research. Now, let’s take a closer look at how to conduct it.

Secondary research is an important tool for gathering information already collected and analyzed by others. It can help us save time and money and allow us to gain insights into the subject we are researching. So, in this section, we will discuss some common methods and tips for conducting it effectively.

Here are the steps involved in conducting secondary research:

1. Identify the topic of research: Before beginning secondary research, identify the topic that needs research. Once that’s done, list down the research attributes and its purpose.

2. Identify research sources: Next, narrow down on the information sources that will provide most relevant data and information applicable to your research.

3. Collect existing data: Once the data collection sources are narrowed down, check for any previous data that is available which is closely related to the topic. Data related to research can be obtained from various sources like newspapers, public libraries, government and non-government agencies etc.

4. Combine and compare: Once data is collected, combine and compare the data for any duplication and assemble data into a usable format. Make sure to collect data from authentic sources. Incorrect data can hamper research severely.

4. Analyze data: Analyze collected data and identify if all questions are answered. If not, repeat the process if there is a need to dwell further into actionable insights.

Advantages of Secondary Research

Secondary research offers a number of advantages to researchers, including efficiency, the ability to build upon existing knowledge, and the ability to conduct research in situations where primary research may not be possible or ethical. By carefully selecting their sources and being thoughtful in their approach, researchers can leverage secondary research to drive impact and advance the field. Some key advantages are the following:

1. Most information in this research is readily available. There are many sources from which relevant data can be collected and used, unlike primary research, where data needs to collect from scratch.

2. This is a less expensive and less time-consuming process as data required is easily available and doesn’t cost much if extracted from authentic sources. A minimum expenditure is associated to obtain data.

3. The data that is collected through secondary research gives organizations or businesses an idea about the effectiveness of primary research. Hence, organizations or businesses can form a hypothesis and evaluate cost of conducting primary research.

4. Secondary research is quicker to conduct because of the availability of data. It can be completed within a few weeks depending on the objective of businesses or scale of data needed.

As we can see, this research is the process of analyzing data already collected by someone else, and it can offer a number of benefits to researchers.

Disadvantages of Secondary Research

On the other hand, we have some disadvantages that come with doing secondary research. Some of the most notorious are the following:

1. Although data is readily available, credibility evaluation must be performed to understand the authenticity of the information available.

2. Not all secondary data resources offer the latest reports and statistics. Even when the data is accurate, it may not be updated enough to accommodate recent timelines.

3. Secondary research derives its conclusion from collective primary research data. The success of your research will depend, to a greater extent, on the quality of research already conducted by primary research.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

In conclusion, secondary research is an important tool for researchers exploring various topics. By leveraging existing data sources, researchers can save time and resources, build upon existing knowledge, and conduct research in situations where primary research may not be feasible.

There are a variety of methods and examples of secondary research, from analyzing public data sets to reviewing previously published research papers. As students and aspiring researchers, it’s important to understand the benefits and limitations of this research and to approach it thoughtfully and critically. By doing so, we can continue to advance our understanding of the world around us and contribute to meaningful research that positively impacts society.

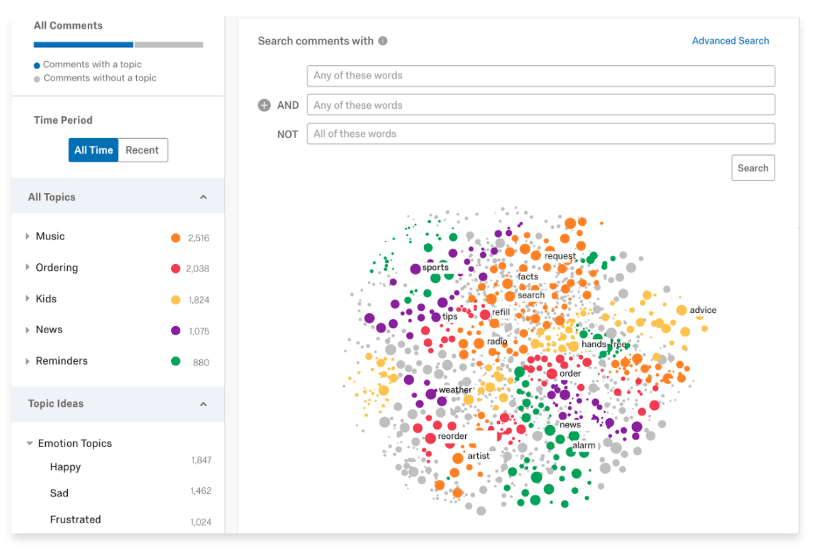

QuestionPro can be a useful tool for conducting secondary research in a variety of ways. You can create online surveys that target a specific population, collecting data that can be analyzed to gain insights into consumer behavior, attitudes, and preferences; analyze existing data sets that you have obtained through other means or benchmark your organization against others in your industry or against industry standards. The software provides a range of benchmarking tools that can help you compare your performance on key metrics, such as customer satisfaction, with that of your peers.

Using QuestionPro thoughtfully and strategically allows you to gain valuable insights to inform decision-making and drive business success. Start today for free! No credit card is required.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

360 Degree Feedback Spider Chart is Back!

Aug 14, 2024

Jotform vs Wufoo: Comparison of Features and Prices

Aug 13, 2024

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Life@QuestionPro: Thomas Maiwald-Immer’s Experience

Aug 9, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

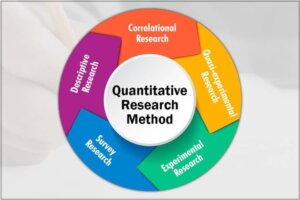

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

| Research method | How to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Control or manipulate an to measure its effect on a dependent variable. | To test whether an intervention can reduce procrastination in college students, you give equal-sized groups either a procrastination intervention or a comparable task. You compare self-ratings of procrastination behaviors between the groups after the intervention. | |

| Ask questions of a group of people in-person, over-the-phone or online. | You distribute with rating scales to first-year international college students to investigate their experiences of culture shock. | |

| (Systematic) observation | Identify a behavior or occurrence of interest and monitor it in its natural setting. | To study college classroom participation, you sit in on classes to observe them, counting and recording the prevalence of active and passive behaviors by students from different backgrounds. |

| Secondary research | Collect data that has been gathered for other purposes e.g., national surveys or historical records. | To assess whether attitudes towards climate change have changed since the 1980s, you collect relevant questionnaire data from widely available . |

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Quantitative Research? Definition, Methods, Types, and Examples

If you’re wondering what is quantitative research and whether this methodology works for your research study, you’re not alone. If you want a simple quantitative research definition , then it’s enough to say that this is a method undertaken by researchers based on their study requirements. However, to select the most appropriate research for their study type, researchers should know all the methods available.

Selecting the right research method depends on a few important criteria, such as the research question, study type, time, costs, data availability, and availability of respondents. There are two main types of research methods— quantitative research and qualitative research. The purpose of quantitative research is to validate or test a theory or hypothesis and that of qualitative research is to understand a subject or event or identify reasons for observed patterns.

Quantitative research methods are used to observe events that affect a particular group of individuals, which is the sample population. In this type of research, diverse numerical data are collected through various methods and then statistically analyzed to aggregate the data, compare them, or show relationships among the data. Quantitative research methods broadly include questionnaires, structured observations, and experiments.

Here are two quantitative research examples:

- Satisfaction surveys sent out by a company regarding their revamped customer service initiatives. Customers are asked to rate their experience on a rating scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

- A school has introduced a new after-school program for children, and a few months after commencement, the school sends out feedback questionnaires to the parents of the enrolled children. Such questionnaires usually include close-ended questions that require either definite answers or a Yes/No option. This helps in a quick, overall assessment of the program’s outreach and success.

Table of Contents

What is quantitative research ? 1,2

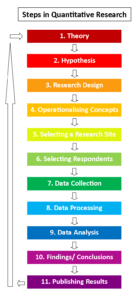

The steps shown in the figure can be grouped into the following broad steps:

- Theory : Define the problem area or area of interest and create a research question.

- Hypothesis : Develop a hypothesis based on the research question. This hypothesis will be tested in the remaining steps.

- Research design : In this step, the most appropriate quantitative research design will be selected, including deciding on the sample size, selecting respondents, identifying research sites, if any, etc.

- Data collection : This process could be extensive based on your research objective and sample size.

- Data analysis : Statistical analysis is used to analyze the data collected. The results from the analysis help in either supporting or rejecting your hypothesis.

- Present results : Based on the data analysis, conclusions are drawn, and results are presented as accurately as possible.

Quantitative research characteristics 4

- Large sample size : This ensures reliability because this sample represents the target population or market. Due to the large sample size, the outcomes can be generalized to the entire population as well, making this one of the important characteristics of quantitative research .

- Structured data and measurable variables: The data are numeric and can be analyzed easily. Quantitative research involves the use of measurable variables such as age, salary range, highest education, etc.

- Easy-to-use data collection methods : The methods include experiments, controlled observations, and questionnaires and surveys with a rating scale or close-ended questions, which require simple and to-the-point answers; are not bound by geographical regions; and are easy to administer.

- Data analysis : Structured and accurate statistical analysis methods using software applications such as Excel, SPSS, R. The analysis is fast, accurate, and less effort intensive.

- Reliable : The respondents answer close-ended questions, their responses are direct without ambiguity and yield numeric outcomes, which are therefore highly reliable.

- Reusable outcomes : This is one of the key characteristics – outcomes of one research can be used and replicated in other research as well and is not exclusive to only one study.

Quantitative research methods 5

Quantitative research methods are classified into two types—primary and secondary.

Primary quantitative research method:

In this type of quantitative research , data are directly collected by the researchers using the following methods.

– Survey research : Surveys are the easiest and most commonly used quantitative research method . They are of two types— cross-sectional and longitudinal.

->Cross-sectional surveys are specifically conducted on a target population for a specified period, that is, these surveys have a specific starting and ending time and researchers study the events during this period to arrive at conclusions. The main purpose of these surveys is to describe and assess the characteristics of a population. There is one independent variable in this study, which is a common factor applicable to all participants in the population, for example, living in a specific city, diagnosed with a specific disease, of a certain age group, etc. An example of a cross-sectional survey is a study to understand why individuals residing in houses built before 1979 in the US are more susceptible to lead contamination.

->Longitudinal surveys are conducted at different time durations. These surveys involve observing the interactions among different variables in the target population, exposing them to various causal factors, and understanding their effects across a longer period. These studies are helpful to analyze a problem in the long term. An example of a longitudinal study is the study of the relationship between smoking and lung cancer over a long period.

– Descriptive research : Explains the current status of an identified and measurable variable. Unlike other types of quantitative research , a hypothesis is not needed at the beginning of the study and can be developed even after data collection. This type of quantitative research describes the characteristics of a problem and answers the what, when, where of a problem. However, it doesn’t answer the why of the problem and doesn’t explore cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Data from this research could be used as preliminary data for another study. Example: A researcher undertakes a study to examine the growth strategy of a company. This sample data can be used by other companies to determine their own growth strategy.

– Correlational research : This quantitative research method is used to establish a relationship between two variables using statistical analysis and analyze how one affects the other. The research is non-experimental because the researcher doesn’t control or manipulate any of the variables. At least two separate sample groups are needed for this research. Example: Researchers studying a correlation between regular exercise and diabetes.

– Causal-comparative research : This type of quantitative research examines the cause-effect relationships in retrospect between a dependent and independent variable and determines the causes of the already existing differences between groups of people. This is not a true experiment because it doesn’t assign participants to groups randomly. Example: To study the wage differences between men and women in the same role. For this, already existing wage information is analyzed to understand the relationship.

– Experimental research : This quantitative research method uses true experiments or scientific methods for determining a cause-effect relation between variables. It involves testing a hypothesis through experiments, in which one or more independent variables are manipulated and then their effect on dependent variables are studied. Example: A researcher studies the importance of a drug in treating a disease by administering the drug in few patients and not administering in a few.

The following data collection methods are commonly used in primary quantitative research :

- Sampling : The most common type is probability sampling, in which a sample is chosen from a larger population using some form of random selection, that is, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. The different types of probability sampling are—simple random, systematic, stratified, and cluster sampling.

- Interviews : These are commonly telephonic or face-to-face.

- Observations : Structured observations are most commonly used in quantitative research . In this method, researchers make observations about specific behaviors of individuals in a structured setting.

- Document review : Reviewing existing research or documents to collect evidence for supporting the quantitative research .

- Surveys and questionnaires : Surveys can be administered both online and offline depending on the requirement and sample size.

The data collected can be analyzed in several ways in quantitative research , as listed below:

- Cross-tabulation —Uses a tabular format to draw inferences among collected data

- MaxDiff analysis —Gauges the preferences of the respondents

- TURF analysis —Total Unduplicated Reach and Frequency Analysis; helps in determining the market strategy for a business

- Gap analysis —Identify gaps in attaining the desired results

- SWOT analysis —Helps identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of a product, service, or organization

- Text analysis —Used for interpreting unstructured data

Secondary quantitative research methods :

This method involves conducting research using already existing or secondary data. This method is less effort intensive and requires lesser time. However, researchers should verify the authenticity and recency of the sources being used and ensure their accuracy.

The main sources of secondary data are:

- The Internet

- Government and non-government sources

- Public libraries

- Educational institutions

- Commercial information sources such as newspapers, journals, radio, TV

When to use quantitative research 6

Here are some simple ways to decide when to use quantitative research . Use quantitative research to:

- recommend a final course of action

- find whether a consensus exists regarding a particular subject

- generalize results to a larger population

- determine a cause-and-effect relationship between variables

- describe characteristics of specific groups of people

- test hypotheses and examine specific relationships

- identify and establish size of market segments

A research case study to understand when to use quantitative research 7

Context: A study was undertaken to evaluate a major innovation in a hospital’s design, in terms of workforce implications and impact on patient and staff experiences of all single-room hospital accommodations. The researchers undertook a mixed methods approach to answer their research questions. Here, we focus on the quantitative research aspect.

Research questions : What are the advantages and disadvantages for the staff as a result of the hospital’s move to the new design with all single-room accommodations? Did the move affect staff experience and well-being and improve their ability to deliver high-quality care?

Method: The researchers obtained quantitative data from three sources:

- Staff activity (task time distribution): Each staff member was shadowed by a researcher who observed each task undertaken by the staff, and logged the time spent on each activity.

- Staff travel distances : The staff were requested to wear pedometers, which recorded the distances covered.

- Staff experience surveys : Staff were surveyed before and after the move to the new hospital design.

Results of quantitative research : The following observations were made based on quantitative data analysis:

- The move to the new design did not result in a significant change in the proportion of time spent on different activities.

- Staff activity events observed per session were higher after the move, and direct care and professional communication events per hour decreased significantly, suggesting fewer interruptions and less fragmented care.

- A significant increase in medication tasks among the recorded events suggests that medication administration was integrated into patient care activities.

- Travel distances increased for all staff, with highest increases for staff in the older people’s ward and surgical wards.

- Ratings for staff toilet facilities, locker facilities, and space at staff bases were higher but those for social interaction and natural light were lower.

Advantages of quantitative research 1,2

When choosing the right research methodology, also consider the advantages of quantitative research and how it can impact your study.

- Quantitative research methods are more scientific and rational. They use quantifiable data leading to objectivity in the results and avoid any chances of ambiguity.

- This type of research uses numeric data so analysis is relatively easier .

- In most cases, a hypothesis is already developed and quantitative research helps in testing and validatin g these constructed theories based on which researchers can make an informed decision about accepting or rejecting their theory.

- The use of statistical analysis software ensures quick analysis of large volumes of data and is less effort intensive.

- Higher levels of control can be applied to the research so the chances of bias can be reduced.

- Quantitative research is based on measured value s, facts, and verifiable information so it can be easily checked or replicated by other researchers leading to continuity in scientific research.

Disadvantages of quantitative research 1,2

Quantitative research may also be limiting; take a look at the disadvantages of quantitative research.

- Experiments are conducted in controlled settings instead of natural settings and it is possible for researchers to either intentionally or unintentionally manipulate the experiment settings to suit the results they desire.

- Participants must necessarily give objective answers (either one- or two-word, or yes or no answers) and the reasons for their selection or the context are not considered.

- Inadequate knowledge of statistical analysis methods may affect the results and their interpretation.

- Although statistical analysis indicates the trends or patterns among variables, the reasons for these observed patterns cannot be interpreted and the research may not give a complete picture.

- Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate and generalizable analysis .

- Quantitative research cannot be used to address complex issues.

Frequently asked questions on quantitative research

Q: What is the difference between quantitative research and qualitative research? 1

A: The following table lists the key differences between quantitative research and qualitative research, some of which may have been mentioned earlier in the article.

| Purpose and design | ||

| Research question | ||

| Sample size | Large | Small |

| Data | ||

| Data collection method | Experiments, controlled observations, questionnaires and surveys with a rating scale or close-ended questions. The methods can be experimental, quasi-experimental, descriptive, or correlational. | Semi-structured interviews/surveys with open-ended questions, document study/literature reviews, focus groups, case study research, ethnography |

| Data analysis |

Q: What is the difference between reliability and validity? 8,9

A: The term reliability refers to the consistency of a research study. For instance, if a food-measuring weighing scale gives different readings every time the same quantity of food is measured then that weighing scale is not reliable. If the findings in a research study are consistent every time a measurement is made, then the study is considered reliable. However, it is usually unlikely to obtain the exact same results every time because some contributing variables may change. In such cases, a correlation coefficient is used to assess the degree of reliability. A strong positive correlation between the results indicates reliability.

Validity can be defined as the degree to which a tool actually measures what it claims to measure. It helps confirm the credibility of your research and suggests that the results may be generalizable. In other words, it measures the accuracy of the research.

The following table gives the key differences between reliability and validity.

| Importance | Refers to the consistency of a measure | Refers to the accuracy of a measure |

| Ease of achieving | Easier, yields results faster | Involves more analysis, more difficult to achieve |

| Assessment method | By examining the consistency of outcomes over time, between various observers, and within the test | By comparing the accuracy of the results with accepted theories and other measurements of the same idea |

| Relationship | Unreliable measurements typically cannot be valid | Valid measurements are also reliable |

| Types | Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, inter-rater reliability | Content validity, criterion validity, face validity, construct validity |

Q: What is mixed methods research? 10

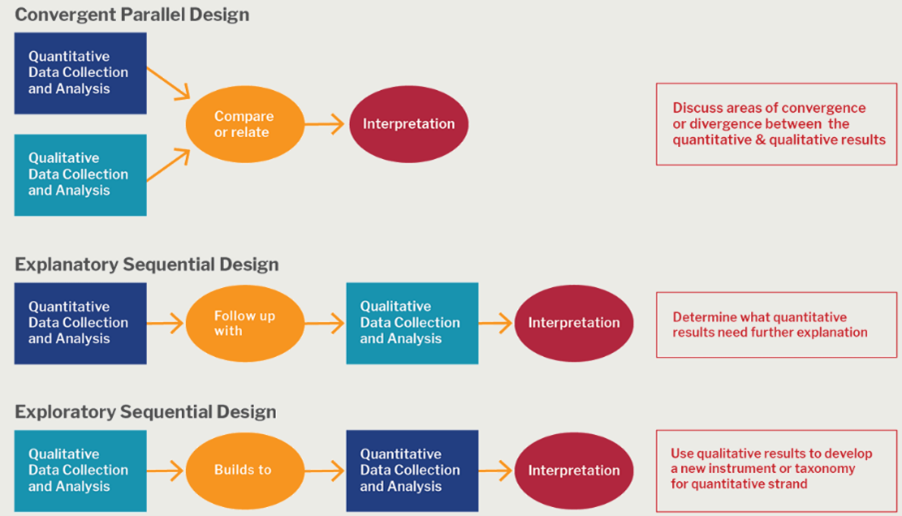

A: A mixed methods approach combines the characteristics of both quantitative research and qualitative research in the same study. This method allows researchers to validate their findings, verify if the results observed using both methods are complementary, and explain any unexpected results obtained from one method by using the other method. A mixed methods research design is useful in case of research questions that cannot be answered by either quantitative research or qualitative research alone. However, this method could be more effort- and cost-intensive because of the requirement of more resources. The figure 3 shows some basic mixed methods research designs that could be used.

Thus, quantitative research is the appropriate method for testing your hypotheses and can be used either alone or in combination with qualitative research per your study requirements. We hope this article has provided an insight into the various facets of quantitative research , including its different characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages, and a few tips to quickly understand when to use this research method.

References

- Qualitative vs quantitative research: Differences, examples, & methods. Simply Psychology. Accessed Feb 28, 2023. https://simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html#Quantitative-Research

- Your ultimate guide to quantitative research. Qualtrics. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/experience-management/research/quantitative-research/

- The steps of quantitative research. Revise Sociology. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://revisesociology.com/2017/11/26/the-steps-of-quantitative-research/

- What are the characteristics of quantitative research? Marketing91. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.marketing91.com/characteristics-of-quantitative-research/

- Quantitative research: Types, characteristics, methods, & examples. ProProfs Survey Maker. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.proprofssurvey.com/blog/quantitative-research/#Characteristics_of_Quantitative_Research

- Qualitative research isn’t as scientific as quantitative methods. Kmusial blog. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://kmusial.wordpress.com/2011/11/25/qualitative-research-isnt-as-scientific-as-quantitative-methods/

- Maben J, Griffiths P, Penfold C, et al. Evaluating a major innovation in hospital design: workforce implications and impact on patient and staff experiences of all single room hospital accommodation. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015 Feb. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 3.3.) Chapter 5, Case study quantitative data findings. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK274429/

- McLeod, S. A. (2007). What is reliability? Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/reliability.html

- Reliability vs validity: Differences & examples. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://statisticsbyjim.com/basics/reliability-vs-validity/

- Mixed methods research. Community Engagement Program. Harvard Catalyst. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://catalyst.harvard.edu/community-engagement/mmr

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

What Is Secondary Data? A Complete Guide

What is secondary data, and why is it important? Find out in this post.

Within data analytics, there are many ways of categorizing data. A common distinction, for instance, is that between qualitative and quantitative data . In addition, you might also distinguish your data based on factors like sensitivity. For example, is it publicly available or is it highly confidential?

Probably the most fundamental distinction between different types of data is their source. Namely, are they primary, secondary, or third-party data? Each of these vital data sources supports the data analytics process in its own way. In this post, we’ll focus specifically on secondary data. We’ll look at its main characteristics, provide some examples, and highlight the main pros and cons of using secondary data in your analysis.

We’ll cover the following topics:

What is secondary data?

- What’s the difference between primary, secondary, and third-party data?

- What are some examples of secondary data?

- How to analyse secondary data

- Advantages of secondary data

- Disadvantages of secondary data

- Wrap-up and further reading

Ready to learn all about secondary data? Then let’s go.

1. What is secondary data?

Secondary data (also known as second-party data) refers to any dataset collected by any person other than the one using it.

Secondary data sources are extremely useful. They allow researchers and data analysts to build large, high-quality databases that help solve business problems. By expanding their datasets with secondary data, analysts can enhance the quality and accuracy of their insights. Most secondary data comes from external organizations. However, secondary data also refers to that collected within an organization and then repurposed.

Secondary data has various benefits and drawbacks, which we’ll explore in detail in section four. First, though, it’s essential to contextualize secondary data by understanding its relationship to two other sources of data: primary and third-party data. We’ll look at these next.

2. What’s the difference between primary, secondary, and third-party data?

To best understand secondary data, we need to know how it relates to the other main data sources: primary and third-party data.

What is primary data?

‘Primary data’ (also known as first-party data) are those directly collected or obtained by the organization or individual that intends to use them. Primary data are always collected for a specific purpose. This could be to inform a defined goal or objective or to address a particular business problem.

For example, a real estate organization might want to analyze current housing market trends. This might involve conducting interviews, collecting facts and figures through surveys and focus groups, or capturing data via electronic forms. Focusing only on the data required to complete the task at hand ensures that primary data remain highly relevant. They’re also well-structured and of high quality.

As explained, ‘secondary data’ describes those collected for a purpose other than the task at hand. Secondary data can come from within an organization but more commonly originate from an external source. If it helps to make the distinction, secondary data is essentially just another organization’s primary data.

Secondary data sources are so numerous that they’ve started playing an increasingly vital role in research and analytics. They are easier to source than primary data and can be repurposed to solve many different problems. While secondary data may be less relevant for a given task than primary data, they are generally still well-structured and highly reliable.

What is third-party data?