- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Research Collections

- Review Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Policy and Planning

- About the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- HPP at a glance

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, scoping review methodology, an iterative approach, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Using WhatsApp messenger for health systems research: a scoping review of available literature

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Karima Manji, Johanna Hanefeld, Jo Vearey, Helen Walls, Thea de Gruchy, Using WhatsApp messenger for health systems research: a scoping review of available literature, Health Policy and Planning , Volume 36, Issue 5, June 2021, Pages 774–789, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab024

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Globally, the use of mobile phones for improving access to healthcare and conducting health research has gained traction in recent years as rates of ownership increase, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Mobile instant messaging applications, including WhatsApp Messenger, provide new and affordable opportunities for health research across time and place, potentially addressing the challenges of maintaining contact and participation involved in research with migrant and mobile populations, for example. However, little is known about the opportunities and challenges associated with the use of WhatsApp as a tool for health research. To inform our study, we conducted a scoping review of published health research that uses WhatsApp as a data collection tool. A key reason for focusing on WhatsApp is the ability to retain contact with participants when they cross international borders. Five key public health databases were searched for articles containing the words ‘WhatsApp’ and ‘health research’ in their titles and abstracts. We identified 69 articles, 16 of which met our inclusion criteria for review. We extracted data pertaining to the characteristics of the research. Across the 16 studies—11 of which were based in LMICs—WhatsApp was primarily used in one of two ways. In the eight quantitative studies identified, seven used WhatsApp to send hyperlinks to online surveys. With one exception, the eight studies that employed a qualitative ( n  = 6) or mixed-method ( n  = 2) design analysed the WhatsApp content generated through a WhatsApp-based programmatic intervention. We found a lack of attention paid to research ethics across the studies, which is concerning given the controversies WhatsApp has faced with regard to data protection in relation to end-to-end encryption. We provide recommendations to address these issues for researchers considering using WhatsApp as a data collection tool over time and place.

WhatsApp Messenger provides new and affordable opportunities for health research across time and place, potentially addressing the challenges of maintaining contact and participation involved in research with migrant and mobile populations, for example.

However, little is known about the opportunities and challenges associated with the use of WhatsApp as a tool for health research.

Reviewing the literature reveals that most of the studies using WhatsApp as a data collection tool for health research have been undertaken in low-and-middle-income countries and that WhatsApp was primarily used either to send hyperlinks to online surveys or to analyse the WhatsApp content generated through a WhatsApp-based intervention.

These studies pay little to no attention to research ethics, which is concerning given the controversies WhatsApp has faced with regard to data protection in relation to end-to-end encryption.

We provide recommendations to address these issues for researchers considering using WhatsApp as a data collection tool over time and place.

A growing body of literature addresses the role that increased ownership and use of mobile phones can play in improving both access to healthcare and health systems research in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), specifically in sub-Saharan Africa ( Bloomfield et al. , 2014 ; Hampshire et al. , 2015 ; Lee et al. , 2017 ). The sub-Saharan African region is characterized by mixed migration flows and multiple health challenges, including HIV and tuberculosis, that, due to the inequalities experienced in access to healthcare disproportionately affect many groups—including migrants and mobile populations ( Vearey et al., 2017 ; Vearey, 2018 ). Given the existing structural factors impeding access to healthcare, coupled with high rates of mobile telephone use across the sub-Saharan African region, ‘mobile health’ or ‘mHealth’—broadly defined as the use of mobile phones in health systems ( Noordam et al. , 2011 )—is consistently recognized as having great potential for improving access to healthcare in this context ( Bloomfield et al. , 2014 ; Hampshire et al. , 2015 ; Lee et al. , 2017 ). Its application ranges from the use of mobile phones to improve point-of-care data collection, delivery and communication to real-time medication monitoring and adherence support ( Bervell and Al-Samarraie, 2019 ). Such mobile technologies also offer opportunities for health systems research.

The Migration, Gender and Health Systems (MiGHS) project—a collaboration between the Universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the South African National Department of Health (NDoH)—is researching the impact of migration and mobility on the South African public healthcare system. We identified a gap in methodologies that are able to capture ‘real-time’ data about the healthcare-seeking experiences and interactions with healthcare systems that migrant and mobile populations have over time and place.

To this end, we are exploring the use of WhatsApp Messenger (‘WhatsApp’), a Mobile Instant Messaging (MIM) platform, as a tool for conducting longitudinal research on health systems use by migrant and mobile communities in South Africa. We focus on WhatsApp due to the specific opportunities it presents for undertaking health systems research across both time and place with migrant and mobile populations, including those moving within South Africa (internal migrants) and those crossing borders (international migrants, including refugees and asylum seekers). Our decision to focus on WhatsApp is informed by several key observations, including those drawn from existing literature.

Firstly, mobile phones play important and diverse roles in the lives of migrants, both in the Global North and South ( Bacishoga et al. , 2016 ; DA Silva Braga, 2016 ; Frouws et al. , 2016 ; Lim and Pham, 2016 ; Alencar et al. , 2019 ; Mancini et al. , 2019 ; Mattelart, 2019 ; Alencar, 2020 ; Godin and Donà, 2020 ; Greene, 2020 ), including in South Africa ( Marchetti-Mercer and Swartz, 2020 ). WhatsApp is a prevalent and affordable platform in South and Southern Africa ( Shambare, 2014 ; Pindayi, 2017 ; Dahir, 2018 ).

Secondly, WhatsApp facilitates the collection of ‘real-time’ data over both time and place. This is achieved through two key functions; participants are able to share their location via WhatsApp, capturing experiences as they are happening and WhatsApp enables users to keep the same mobile phone number and/or account should they cross international borders. The ability to retain the same number has long been a feature of WhatsApp, but recent updates mean that if the number associated with a WhatsApp account is changed, contacts are notified of the change. As such, if a research participant changes their number, they would remain contactable by a research team.

Finally, WhatsApp can also interface with online platforms that allow for the automatic administration of surveys through WhatsApp. The latter function, which is unique to WhatsApp, warrants an independent review of the use of WhatsApp as a data collection tool, given its potential for conducting health research.

Whilst WhatsApp has been successfully used in research with migrant and mobile groups ( Almenara-Niebla and Ascanio-Sánchez, 2020 ; Khoso et al. , 2020 ), little is known about the use of WhatsApp in health systems research. To address this gap, we have undertaken a scoping review exploring the use of WhatsApp in health systems research. In doing so, we hope to glean lessons learned on how best to design and implement research using WhatsApp with migrant and mobile communities in South Africa. Given the well-documented sensitivities that can emerge when conducting research with migrant and mobile groups ( Duvell et al. , 2008 ; Ahmed et al. , 2019 ), we pay particular attention in our review to the approaches taken to protect participants’ privacy.

After providing an overview of MIM approaches and WhatsApp more specifically, we present the methodology for our scoping review, followed by our findings. We then discuss the implications for health systems research and conclude with recommendations for researchers interested in exploring the use of WhatsApp as a research tool.

Mobile Instant Messaging and the use of WhatsApp Messenger for health systems research

Many mHealth interventions make use of Mobile Instant Messaging (MIM), a feature which allows smartphone users to connect to the internet to send real-time text messages to individuals or groups at little or no cost ( Church and De Oliveira, 2013 ). The real-time text message feature of MIM provides an easy-to-use tool for data collection: it enables immediate communication between researcher and participant; and offers flexibility regarding place and time of use as participants and investigators do not have to share a geographic location ( Kaufmann, 2018b ; Kaufmann and Peil, 2019 ). As a result, research using MIM can be carried out wherever there is internet connectivity, via cell phone networks or Wi-Fi, thus providing new opportunities for research. This is particularly relevant when working with communities, including migrant and mobile populations, that are difficult to reach and/or to maintain contact with over time when using more traditional research methods such as face-to-face interviews and administered surveys ( Kaufmann and Peil, 2019 ).

Globally, WhatsApp Messenger (‘WhatsApp’) has emerged as one of the world’s fastest-growing MIM applications ( Endeley, 2018 ; Fiesler and Hallinan, 2018 ), and, by February 2020 had 2 billion users in >100 countries ( WHATSAPP, 2020 ). The WhatsApp software offers a plethora of health-related uses, including for optimizing communication and the delivery of health education ( Araújo et al. , 2019 ; Lima et al. , 2019 ). It has particularly high penetration rates in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil and South Africa ( Dahir, 2018 ; Fiesler and Hallinan, 2018 ). Most recently, WhatsApp has formed part of both South Africa and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) responses to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic ( DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, S. A., 2020 ; Farai, 2020 ). In March 2020, Health Connect was created for the South African National Department of Health (NDoH) by Praekelt.org, building on Praekelt.org’s experience with national mHealth programmes, including the established MomConnect application ( Seebregts et al. , 2018 ). The Health Connect software has since been used by the WHO to create their own WHO HealthAlert Covid19 chat service, indicating the opportunities and reach provided by WhatsApp globally ( Farai, 2020 ).

Methodological and ethical concerns

The use of WhatsApp necessitates consideration of key methodological, practical and ethical questions ( Boase, 2013 ; Tagg et al. , 2017 ; Barbosa and Milan, 2019 ). For example, there is a need for adequate infrastructure, including reliable access to electricity and the internet, and ownership of smartphones capable of running WhatsApp ( Tagg et al. , 2017 ). Gender and other equity-related differences in the use of mobile technology must also be carefully considered ( Noordam et al. , 2011 ). For example, for many people in Southern Africa, access to a WhatsApp compatible phone remains restrictively expensive. There is also a growing body of literature, particularly from developing countries, on the significant gender divide in access to mobile phones, with men being far more likely to have access to a device than women ( Blumenstock and Eagle, 2010 ; Zainudeen et al., 2010 ; Murphy and Priebe, 2011 ). Some studies reveal the nuanced intersections of mobile phone usage with gender, poverty and other social strata: findings from a study in Rwanda ( Blumenstock and Eagle, 2010 ) indicate that phone owners are wealthier, better educated and predominantly men when compared to the general population. Research using WhatsApp thus has the potential to exacerbate existing inequities, if such considerations are not thoughtfully addressed beforehand.

Ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants and data are also critical when engaging with WhatsApp as a research tool, due to ongoing concerns with the application’s security ( Kimmel and Kestenbaum, 2014 ; Kaufmann and Peil, 2019 ). Although communication on WhatsApp has been encrypted since 2016, allowing data between communicating parties to be secure, this does not stop Facebook—who purchased WhatsApp in 2014—from accessing and using data collected from subscribers, without their affirmative consent ( Kimmel and Kestenbaum, 2014 ). Nor does the encryption technology guarantee privacy from government surveillance for national security purposes ( Endeley, 2018 ). Further, Ganguly (2017) has reported a design feature in WhatsApp that could potentially allow some encrypted messages to be read by unintended recipients, compounding the possible breaches of WhatsApp data. Ethical considerations relating to confidentiality and anonymity of human participants are thus central when collecting data via WhatsApp. This issue is especially pertinent when working with individuals in potentially precarious positions ( Barbosa and Milan, 2019 ), as is often the case, for example, with migrant and mobile communities, who may not hold the documents required to be in a country legally.

The purpose of a scoping review is to identify, retrieve and synthesize literature relevant to a particular topic for the purpose of assessing the main concepts underscoring a research area and the key sources and types of available evidence ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008b ). This scoping review thus endeavours to provide not only a clearer picture of the ways in which WhatsApp is currently being used for health research but also of the opportunities and challenges that the MIM service creates.

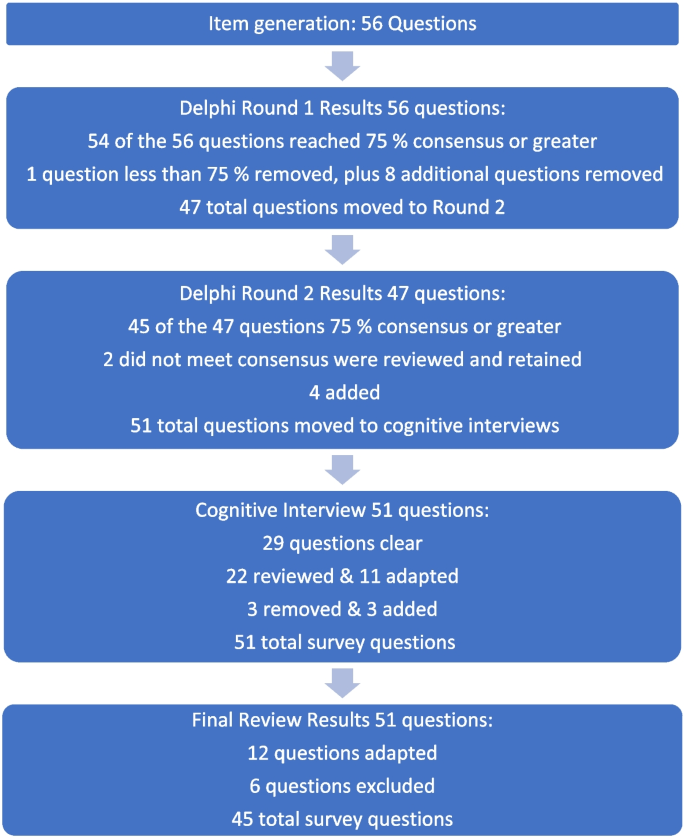

The main stages of this scoping review were: (1) searching for relevant studies; (2) selecting studies based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria; (3) extracting data and (4) characterizing, summarizing and reporting the results. However, this process was iterative, incorporating flexibility in the movement between stages and with some repetition of steps as required to ensure a comprehensive review of the literature ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008b ).

Scoping review methodology observes many of the same steps as systematic reviews: the use of rigorous and transparent methods for data collection, analysis and synthesis remains crucial to enhance the reliability of results and the potential for replication ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008b ; Pham et al. , 2014 ; Munn et al. , 2018 ). A key difference between scoping and systematic reviews, however, is that whilst the study design as well as study findings are important considerations for both, scoping reviews do not typically include a process of quality assessment ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008a ; Grant and Booth, 2009 ). Thus, we did not use study quality as a criterion for selecting studies for the review.

Search strategy

Two study investigators (K.M. and T.d.G.) simultaneously conducted a search of article titles and abstracts in five key public health electronic databases—Scopus, PubMed, SAGE Journals Online, ScienceDirect and JSTOR. The keywords ‘WhatsApp’ and ‘health research’ were combined using the Boolean operator ‘AND’, limiting the publication date from 2009 (the year when WhatsApp was first launched) to November 2019 (the time at which the search was undertaken). Sixty-nine articles were identified through the search—see Table 1 for an overview of the results. We searched both titles and abstracts, as searching and screening titles alone might miss studies using WhatsApp for data collection that did not reflect on this in the study title. Due to time and cost considerations, we limited our search to English language publications.

Study selection

We used the inclusion/exclusion criteria outlined in Table 2 to assign a value of ‘include’, ‘exclude’ or ‘maybe’ to the 69 identified articles in order to ascertain whether the article should be included in the review. In cases where it was not possible to decide based on the abstract alone, the full article was reviewed. Inter-rater reliability of the study selection was high with only five discrepancies, representing 6.3% of the total selected studies. Each discrepancy was a case of one reviewer coding an article as ‘maybe’ with the other coding it as ‘include’ or ‘exclude’. In all cases, the full article was retrieved and read by both investigators (K.M. and T.d.G.) to resolve the discrepancy. Following the full-paper review and exclusion of 5 additional articles, 16 articles were included in the subsequent analysis.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for selecting studies for review

In order to be as inclusive as possible, given the small amount of evidence currently in this area, inclusion and exclusion criteria were deliberately kept broad. For example, no exclusion criteria were defined based on study design or publication type, and we did not use study quality as an inclusion criteria ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008a) .

Data extraction

Following the selection of the articles for review, two study investigators (K.M. and J.H.) developed a standard coding template, which was discussed with all co-investigators, to extract data from each original research article. The template was designed to include a description of the amount, focus and nature (i.e. the scope) of research related to the use of WhatsApp for health research data collection, and to support the summarizing of findings. Whilst the framework was initially developed a priori, we also followed an iterative approach, further expanding on the initial framework to comprehensively cover the findings identified in the data extraction process, in line with our iterative approach ( Lavallee et al. , 2014 ).

Two study investigators (K.M. and T.d.G.) independently extracted the data from each article and entered them into the coding template, developed in Excel. One additional study investigator (J.H.) extracted data from randomly selected articles as an additional cross-check of the findings. With regards to these random checks, we achieved inter-rater reliability of the descriptive data extraction process of 100% agreement.

To describe the overall quantity of research in this field over time, we recorded the year of publication of each article. To describe the focus of the research, we extracted data on the study setting and on, broadly defined, the research participants—healthcare workers or users. To describe the nature of the research, we extracted data on the disciplinary perspective underpinning the study, characterized iteratively (elaborated below) and the study design—whether quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods, how WhatsApp was being applied to collect data and reflections on the choice of WhatsApp for data collection. In addition, if the information was available, we included the following methodological considerations of using WhatsApp: (1) how the participants interacted with the WhatsApp interface—the opportunities and challenges, and an assessment of any social stratification implications of using the application, including gender and/or socio-economic factors, such as those discussed earlier, that can shape certain groups’ access to mobile technology; (2) the impact of WhatsApp, which refers to the researchers’ evaluation of implementing WhatsApp for health research, including technical insights and (3) the ethical implications of using WhatsApp in health research.

Whilst our coding framework was developed a priori, our categories evolved, guided by the data. For example, we expanded the category of research participants to include (in addition to healthcare users and workers) the general public, which we identified as a new code in the data. Further, we distinguished ‘health systems’ from ‘health services’, although the two disciplines are often used interchangeably. In our reading of the studies reviewed, we observed clusters that either: (1) explored the perspectives of health care providers within the health system, for the purpose of health systems strengthening or (2) involved research with healthcare users, to capture aspects of service delivery in the target population. Given these distinctions, we classified the prior studies under ‘health systems’ and the latter under the ‘health services’ umbrella.

Collating, summarizing and reporting results

We used a qualitative descriptive approach ( Weeks and Strudsholm, 2008a) to characterize the evidence on the use of WhatsApp for health research data collection. Figure 1 summarizes the search strategy and study selection processes of the scoping review.

Results of search strategy and process of selecting articles on the use of WhatsApp for health research data collection.

Our results are presented in three main categories: (1) the number of articles published per year (the amount) and focus of research; (2) discipline and study design and (3) methodological implications—a brief overview of which can be found in Table 3. As such, the first section provides a summary of the trends observed in the literature, including the number of studies published according to year, the study settings and a classification of the study subjects (health providers and/or users and/or general public). The second section distinguishes between the different disciplines that cut across the literature and the various study designs that use WhatsApp for health researchas linked to these disciplines. It further examines the study designs, including approaches to data collection and analysis, according to three classifications: (1) quantitative studies; (2) qualitative studies and (3) mixed-methods studies. In the final section, the methodological implications of using WhatsApp are elaborated according to the study designs identified in the previous section.

Amount and focus of research employing WhatsApp as a data collection tool

We identified 16 articles that employed WhatsApp for health research in the defined time period (2009–19). All articles were published in 2016 or later, with nine articles (over half of the total) published in 2019. The articles identified covered research from a variety of contexts. Five of the studies present work undertaken in HICs; the United Kingdom (UK) ( Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ), the United Arab Emirates (UAE) ( Hazzam and Lahrech, 2018 ), Saudi Arabia ( Alsohibani et al. , 2019 ) and Israel ( Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ). The remaining 11 articles focused on research from LMICs; three present work from India ( Rasidi and Varma, 2017 ; Karim et al. , 2019 ; Tyagi et al. , 2019 ), two from Nigeria ( Khalid et al. , 2019 ; Shitu et al. , 2019 ) and one each from Kenya ( Henry et al. , 2016 ); Malawi ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ); Mozambique ( Arroz et al. , 2019 ); Peru ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ); Syria ( Fardousi et al. , 2019 ) and Zimbabwe ( Madziyire et al. , 2017 ). The majority of the studies (11 out of 16) collected data on the perspective of healthcare providers, including interns (apprentices or trainees). Two studies collected data from healthcare users, one from the general public, one from the general public and healthcare providers and one from medical students.

Nature of research employing WhatsApp as a data collection tool

Discipline and study design.

The 16 studies identified were from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, most commonly health systems ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Hazzam and Lahrech, 2018 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ; Fardousi et al. , 2019 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ). Additional disciplines include health services ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Tyagi et al. , 2019 ), public health ( Alsohibani et al. , 2019 ; Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ), medical education ( Raiman et al. , 2017 ) and various clinical science disciplines, including dentistry ( Rasidi and Varma, 2017 ), medicine ( Madziyire et al. , 2017 ; Karim et al. , 2019 ) and pharmacy ( Khalid et al. , 2019 ; Shitu et al. , 2019 ).

Half of the studies included in the review are quantitative in nature ( Madziyire et al. , 2017 ; Rasidi and Varma, 2017 ; Hazzam and Lahrech, 2018 ; Alsohibani et al. , 2019 ; Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ; Karim et al. , 2019 ; Khalid et al. , 2019 ; Shitu et al. , 2019 ) of which the majority ( n  = 5) are from the clinical science disciplines (as listed above). None of the quantitative studies includes a statement on their decision to use WhatsApp for data collection, such as the opportunities it provides for the research in question, either generally, or compared to other online data collection approaches. In seven of the eight quantitative studies identified, WhatsApp was used—either exclusively ( n  = 2), or in combination with other social media channels ( n  = 5)—to send hyperlinks to online surveys, thereby functioning as an intermediary platform for data collection. One study ( Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ), however, used a web-based platform to build an interactive survey that was distributed via multiple social media channels, including WhatsApp. As described earlier, WhatsApp can interface with such web-based platforms that allow for the automatic administration of surveys through WhatsApp, such that participants can receive and respond to questions one at a time in the chat box. Although the above study in question does imply that the survey was administered—via several online channels—on a question-by-question basis, rather than simply distributed at one go, the authors did not elaborate on the exact process of data collection.

Across the quantitative studies, the recruitment strategies used were poorly described. Two studies ( Madziyire et al. , 2017 ; Khalid et al. , 2019 ) indicate that recruitment of participants occurred before sending them the survey link via WhatsApp, without elaborating any further. In five of the studies, WhatsApp was used as the recruitment tool; authors either directly sent the survey link to pre-identified target groups, at large, as a means of recruiting potential individuals ( Hazzam and Lahrech, 2018 ; Karim et al. , 2019 ; Shitu et al. , 2019 ); or they sent the link to a sub-set of known individuals in the target group, who then, through a snowball approach identified and forwarded the link to additional eligible participants ( Alsohibani et al. , 2019 , Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ). The process of recruitment across these five studies, however, is vague. It appears there was no explicit strategy, and that recruitment happened passively, through simply forwarding the survey link to potential participants (and in some cases requesting them to re-forward the link further). In one study ( Rasidi and Varma, 2017 ), there is no indication given at all as to how the participants were recruited.

Six of the studies employed a qualitative design ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 , ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ; Fardousi et al. , 2019 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ) and were undertaken with either a health systems or health services disciplinary focus. Of these, three studies analysed data sourced from (written) text messages sent over WhatsApp ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ); one study analysed WhatsApp text messages and images ( Arroz et al. , 2019 ); another one analysed text messages, images and webpage links shared via WhatsApp ( Raiman et al. , 2017 ); and the final study analysed voice calls recorded over WhatsApp ( Fardousi et al. , 2019 ). The data from the studies were analysed using either thematic analysis ( n  = 4) or content analysis ( n  = 2).

With one exception ( Fardousi et al. , 2019 ), the qualitative studies and two mixed-methods studies (discussed below), all used WhatsApp in a tethered approach—to deliver an intervention, either for mentoring or improving access to care, with the success of the intervention subsequently evaluated through analysing the WhatsApp content that was generated as part of the intervention (as specified above and below). As exemplified in these studies, WhatsApp was used for data collection, beyond just delivering the intervention in question.

To elaborate further, two-thirds of the qualitative studies ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ) used WhatsApp to facilitate communication between junior and senior workers for mentoring and/or educational purposes. Given the nature of these studies, since the mentoring and/or educational intervention that was delivered via WhatsApp also formed the data source, the participants in the intervention were simultaneously recruited as the subjects for the data collection component of the study.

Of these, three studies ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ) explicitly discuss the choice of WhatsApp for data collection, based on its popularity as a social communication tool. The other two qualitative studies included in the review employed WhatsApp (in combination with other approaches) to collect data amongst groups facing vulnerability. One study ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ) describes how WhatsApp (and SMS) text messages were employed to elicit barriers and facilitators to accessing HIV health services amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) in Peru. The authors make a general observation regarding the acceptability of mHealth interventions amongst this group of individuals, without specifically justifying their choice of WhatsApp, either generally—as an instant messaging platform—or over other digital platforms. In the other study ( Fardousi et al. , 2019 ), the authors describe how they selected WhatsApp (and Skype) to conduct interviews remotely, in areas where physical access was a barrier, to understand challenges experienced by healthcare providers in besieged areas in Syria. The authors indicate that they used purposive sampling to recruit healthcare providers, who were then snowballed, with each recommending two-to-three additional potential participants.

The two remaining studies included in the review employed mixed-methods approaches. Pimmer et al. (2017) used WhatsApp as a communication tool between healthcare workers—with a similar design and recruitment approach as the four qualitative studies described earlier—to explicitly understand its application to support healthcare work. They subsequently analysed the WhatsApp text messages, both thematically and statistically. In the other mixed-methods study ( Tyagi et al. , 2019 ), rehabilitated participants with spinal cord injury sent video clips of their daily activities via email, text or WhatsApp (pre-intervention) that were then used by therapists to highlight images of wrong movements captured in these videos (as part of the intervention). The patients were recruited through a spinal rehabilitation centre. To analyse the functional status of patients pre- and post-intervention, patients completed the spinal cord independence measure (SCIM). The authors broadly infer the opportunities of telehealth to overcome barriers to continuity of care, without specific reference to the choice of WhatsApp in the study.

Methodological implications of using WhatsApp

Opportunities, challenges and impact.

Of the eight quantitative studies included in the review, none discuss the experiences of the research participants (positive or otherwise) while interacting with the WhatsApp interface, and neither do they evaluate the impact nor provide technical insights of implementing WhatsApp in the study. A limitation noted in three of the quantitative studies ( Hazzam and Lahrech, 2018 ; Khalid et al. , 2019 ; Shitu et al. , 2019 ), all of which focus on health care providers, is the exclusion of participants who do not use social media platforms. Three studies, also amongst providers, describe challenges that also link to the technological nature of the research: (1) low response rates ( Khalid et al. , 2019 ); (2) difficulties in determining response rates as the number of eligible participants who received the survey link were unknown ( Shitu et al. , 2019 ) and (3) the inability of respondents to seek clarity on questions ( Madziyire et al. , 2017 ).

With regards to the qualitative and mixed-methods study designs, the most commonly identified opportunities, as extracted from the data collected via WhatsApp (described earlier) suggest that WhatsApp is mobilized to share information ( Henry et al. , 2016 , ; Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ), raise questions ( Henry et al. , 2016 , ; Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ) and support the professional development of junior-level staff ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ). In addition, two studies ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ) cite the participatory communication function of the application as an advantage in the context of collecting group information. All the studies that used WhatsApp to facilitate communication between health professionals ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ) report improved communication as a result of using the application. Two studies ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Tyagi et al. , 2019 ) report the usefulness of WhatsApp in overcoming barriers to continuity of care, with Bayona et al. (2017) further emphasizing the opportunity of employing WhatsApp as a means to provide patient perspectives that are missing in provider-defined care models. Fardousi et al. (2019) describe how using WhatsApp for health research in hard to access humanitarian settings can help others similarly situated to mitigate health systems challenges and raise awareness to mobilize the international community. Across several studies, authors cited the potential for discrimination or bias resulting from inadequate infrastructure, technological competency ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 , Fardousi et al. , 2019 ; Tyagi et al. , 2019 ) and gender discrepancies in access to technology ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Fardousi et al. , 2019 ) as challenges linked to using WhatsApp. Additional challenges in two studies that use WhatsApp to facilitate communication between health workers ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ) point to the sharing of unrelated and/or inappropriate content, difficulties maintaining work-life balance (due to the timing of messages) and delays in responses. Several studies ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Arroz et al. , 2019 ) also point to the lack of face-to-face interaction as being problematic in the context of facilitating supervision.

Ethical considerations

We found little consistency between the studies with regards to efforts taken to ensure privacy, confidentiality and anonymity when using WhatsApp as a data collection tool, even in studies of a similar design.

None of the quantitative studies discussed the ethical implications of using WhatsApp for health research. Two of the studies point to some ethical measures taken to inform and protect participants in the research. Khalid et al. (2019) state that their online questionnaire conveyed the study information and emphasized the voluntary nature of participation. Alsohibani et al. (2019) cite that participants’ consent was obtained before administering the online questionnaire, but they do not elaborate on the consent process.

Across the qualitative studies, discussion of research ethics was largely missing with one notable exception. Fardousi et al. (2019) reported taking the following measures for obtaining informed consent and to protect the privacy of healthcare workers in besieged areas of Syria: (1) participants used mobile phones to photograph and send signed consent forms; (2) interviews were recorded anonymously using identification codes and (3) interviewers did not ask for participant names.

In four of the qualitative studies, patient data were shared between health care professionals ( Henry et al. , 2016 ; Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Raiman et al. , 2017 ; Rathbone et al. , 2020 ). However, only one of them ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ) discusses explicit training measures undertaken to prevent sharing of patient-identifying information on WhatsApp. Rathbone et al. (2020) highlight concerns of patient privacy, pointing to a lack of training regarding a safe way to discuss patients on the platform. On the other hand, Raiman et al. (2017) maintain that WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption enables safe referral to and discussion of patients, thereby eliminating the need to anonymise the data. Similarly, Henry et al. (2016) indicate that the WhatsApp content that was shared between health workers was not anonymized; rather, health workers were instructed to obtain verbal consent before posting photos of patients, and personal identifiers were removed from chat logs to ensure patient confidentiality in the reporting of results. Both the study on patients with spinal cord injury ( Tyagi et al. , 2019 ) and the study of health access experiences of MSM ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ) report using patient data directly transmitted by the patients via the WhatsApp platform. However, neither detail how issues of patient confidentiality were handled. This finding is particularly surprising in the case of the latter, as MSM are a population group that are in many contexts marginalized and considered particularly vulnerable ( Cáceres et al. , 2008 ).

The rapid increase in the number of studies using WhatsApp as a tool for health research published per year indicates the growing interest in this area—and reflects developments in mobile technology and the increase in WhatsApp’s user base. That most of the articles we identified describe research conducted in LMICs, with six of those in sub-Saharan Africa, is unsurprising, given that WhatsApp has particularly high penetration rates in these contexts, with India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil and South Africa topping the list ( Dahir, 2018 ; Fiesler and Hallinan, 2018 ). Within these studies, WhatsApp was largely used in one of two ways for health research—to send hyperlinks to online surveys, or to deliver and evaluate, either an intervention designed for healthcare users or a communication programme for healthcare providers.

Our review is limited to studies in health research databases. Using different and/or additional search terms beyond ‘health research’ (e.g. ‘health studies’ or ‘health investigations’) may have yielded more results. We reason, however, that using supplemental search terms would have produced studies similar in nature to those we identified and included in our review. Given that we observed distinct patterns across the wide range of study types and disciplines included in this review, we are confident in the interpretation of our results, including our analysis of the current (limited and nascent) state of literature using WhatsApp for health research. Indeed, the most noteworthy finding of our review is the lack of discussion on how and why WhatsApp was used by the researchers and on the potential limitations or implications of this, including, and especially with regards to ethical concerns. There is a clear need to report on these issues for digital studies, given the known challenges regarding confidentiality and data breaches. We subsequently focus on issues of research ethics in this discussion, in light of the urgent need for researchers to systematically document their use of WhatsApp and engage with its ethical issues.

In almost half of the studies we identified ( n  = 7), WhatsApp was used to facilitate data collection via online surveys. These studies offered little in the way of ethical insights for online research. In most of the surveys we located, the nature of the data collected appeared not to be sensitive, nor were vulnerable populations being surveyed. Nonetheless, the electronic and online nature of survey data add new methodological complexities surrounding data storage and security ( Buchanan and Hvizdak, 2009 ). Given in particular that the mobile app industry is largely unregulated and cybercrime is prevalent, it would have been pertinent for authors to inform the study participants about the potential risks involved and what precautions were being taken to support the privacy and security of the participants’ data ( O’Connor et al. , 2016 ).

In addition, whether individuals consider their data to be safe, secure and used appropriately by those who control it can be a key consideration in a participant’s choice to enrol in a study ( O’Connor et al. , 2016 ). The perception of a survey invitation as spam or containing viruses, and the level of data security can have a possible negative impact on data quality and response rates ( Scriven and Smith-Ferrier, 2003 ). The latter was indeed cited as an issue in several of the studies identified, without the authors providing any explanations regarding participants’ poor engagement. As we reported earlier, the recruitment approaches across the quantitative studies were poorly described and many appeared not to involve an explicit or active strategy for engaging participants. One of the main findings in a systematic review of the factors affecting engagement in digital health studies ( O’Connor et al. , 2016 ) suggests that an active recruitment approach that engages with issues around privacy and security is key to overcoming barriers preventing people from participating in studies of this nature. The process of informed consent prior to the study allows researchers to establish trust with the respondents and provide an explanation of the purpose of the study, the selection criteria, how data will be employed and who will have access to it ( Buchanan and Hvizdak, 2009 ). Obtaining informed consent and assuring that data are carefully handled is essential in academic research and imperative in digital studies ( Kaufmann and Peil, 2019 ), given concerns with confidentiality and data breaches. However, only one of the identified survey designs cites that informed consent was obtained from the research participants. That the remaining studies failed to describe if and how they obtained participants’ consent prior to recruiting them suggests that research ethics is not foregrounded in these studies.

In the remaining half of the studies identified, WhatsApp functioned as both research field site and as a data collection tool, often involving the exchange of sensitive information. These approaches necessitate a systematic discussion of the methodological and ethical implications of the platform’s use for health research. Except for two of the studies identified ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ; Fardousi et al. , 2019 ), ethical procedures outlined were generally limited to obtaining approval from research ethics committees. With regards to digital data in qualitative research, ethical decision-making is compounded in this case by the fact that ethical review boards and respondents themselves may not understand the nuances of software-based data collection tools, including issues associated with the assumed end-to-end encryption of WhatsApp, which is often presumed to be secure ( Markham and Buchanan, 2012 ; Boase, 2013 ). This resonates with data protection concerns within the mHealth field, including the observation that few African countries have comprehensive mHealth data protection legislation in place to begin with, compounding concerns about data security and privacy in LMICs ( Hackett et al. , 2018 ).

The recent introduction of end-to-end encryption to WhatsApp also risks giving users a false sense of security and encourages individuals to use it also for sensitive exchanges, exposing participants to potential risks that researchers may indirectly amplify ( Barbosa and Milan, 2019 ). In fact, the authors in one of the studies ( Raiman et al. , 2017 ) explicitly discuss how the end-to-end encryption offered by WhatsApp provides a safe and secure platform to discuss patients, thereby eliminating the need to anonymize the data. However, as Kaufman and Peil (2019) explain, researchers are in fact unable to guarantee data security on the part of the platform provider as participants are also subject to WhatsApp’s terms of usage and pass over their data rights to Facebook when initially setting up their accounts. In general, we observed a lack of documentation of efforts taken, if any, to anonymize third-party data in the identified studies whereby health professionals exchanged patient data on the platform. With the exception of one of the studies ( Pimmer et al. , 2017 ), the remaining four did not report any formal training on ways to safely share patient data.

Two of the studies identified in our review ( Bayona et al. , 2017 ; Fardousi et al. , 2019 ) dealt with research subjects facing specific vulnerabilities that could result in serious ramifications if the data linked to them were exposed. In one study of MSM in Peru, although the authors, like others before them ( Cáceres et al. , 2008 ) recognized the participants as being from a group facing marginalization and stigma in the country, they did not report taking measures to protect the subjects’ identity through anonymization of the digital data. Such measures, if taken, should be made clear in the manuscript. In the second such study, participants comprised frontline health workers in opposition-controlled areas in Syria. In this case, the authors took a systematic approach to implement full anonymisation (described earlier) in order to protect the research participants from any harm that could result from exposure of their political affiliations.

The purpose of this review was to inform our approach for exploring the use of WhatsApp for data collection among migrant and mobile healthcare users in South Africa. Given our specific interest in capturing ‘real-time’ data about healthcare users’ experiences over time and place, through the administration of a survey methodology, and the unique opportunity that WhatsApp provides in this regard, we hoped to glean insights from other similar studies that may have implemented WhatsApp in this way. However, understanding the methodological opportunities, barriers and impact of using WhatsApp for health research was constrained by the limited ways in which WhatsApp has been used, and how its use has been reported, to date.

Seven out of the eight studies administering surveys used WhatsApp to send hyperlinks to online surveys, with WhatsApp functioning as a ‘static’ platform to facilitate data collection. Such use may not have warranted a discussion of the practical and logistical applications of using the software for health research. However, as described earlier, WhatsApp can also be used to administer surveys directly and ‘actively’ on the platform, an approach that appears to have been considered in one study located in our review ( Gesser-Edelsburg et al. , 2019 ). The authors of this study developed a WhatsApp compatible web-based survey that has the potential to contribute to innovation regarding the nature of digital survey administration. To name a few features, these surveys can be automatically broadcasted to participants, one question at a time, with the receipt of each question being dependent on the completion of the previous one. Further, automated reminders can be sent to participants if, for example, they fail to start the survey after a certain amount of time has lapsed. Such features can enhance response rates in digital surveys, which, as cited earlier, was identified as a common challenge across several studies included in our review. The authors, however, failed to describe their method, which is a lost opportunity for future research.

Indeed with a few exceptions, most of the studies reviewed did not clearly document and describe their use of WhatsApp to collect health-related data, which makes it difficult to identify emerging best practice in this field. Given the use and acceptability of WhatsApp among hard-to-reach and often precarious communities, including asylum seekers and undocumented migrants ( Kaufmann, 2018a ), significant opportunities exist for the use of WhatsApp in research with these populations. However, specific methodological and ethical issues arise when working with these communities, including the uncompromising need to safeguard participant privacy ( Barbosa and Milan, 2019 ). As such, we identify three key imperatives for researchers using WhatsApp in health research.

Primarily, given WhatsApp’s novelty as a research tool, researchers need to systematically and clearly document and discuss their use of the application when presenting their research. Current research tends to gloss over how WhatsApp is used as a research tool obfuscating understanding of best practice moving forward. Improving the state of knowledge in this regard, by documenting the challenges associated with and opportunities provided by WhatsApp, will allow for its improved use.

Secondly, given the ethical concerns regarding the use of WhatsApp, researchers must give consideration to selecting and recording only that information which is necessary to the project, encrypting the recorded data so that it is only available to the researchers, removing identifying information from the data and saving the data on secure servers ( Boase, 2013 ). Although we do recognize that the latter recommendation poses its own challenges, as currently most universities no longer run their own servers and service, preferring to rely on commercial alternatives such as Google and Microsoft ( Barbosa and Milan, 2019 ).

As such, when using WhatsApp as a data collection tool, researchers should endeavour to systematically and clearly document research and ethical considerations. Whereas the WHO guidelines for reporting on mHealth interventions ( Agarwal et al. , 2016 ) are specific to digital programmes aimed at improving access to and use of health services—which is beyond the scope of this study—certain aspects of the guidelines are applicable to research using WhatsApp as a data collection tool. For example, the guidelines advocate the reporting of various important aspects of research design and implementation, to enhance the transparency in reporting, promote the critical assessment of digital research evidence, and improve the rigour of future reporting of research findings. In particular, item 14 of the 16-item checklist explicitly focuses on data security, entrusting researchers using mHealth to describe their data security and confidentiality protocols, including all the steps taken to secure personally identifiable information. This dimension cannot be overstated in our study, given that we have identified critical gaps in protecting the privacy and confidentiality of participant identity and health information in the current state of health research employing WhatsApp.

In addition, addressing barriers to infrastructure must be understood beyond simplified notions of the internet and/or smartphone access. As face-to-face interactions between researchers and participants are limited, additional efforts must be made to ensure that participants understand the terms of the research and are provided with information, relating to the specifics of the research project, regarding how they can seek and access support should it be required. Being able to judge whether study participants require health and/or psychological services and referring them accordingly may be difficult via WhatsApp, which raises additional ethical questions when using WhatsApp to conduct research with groups facing vulnerability. Researchers must accordingly document how they plan to overcome such challenges.

This scoping review highlights the opportunities that WhatsApp provides as a tool for health systems research, specifically with migrant and mobile communities in LMIC settings. WhatsApp is low-cost and convenient to operate, has high penetration globally, and, importantly, enables migrant and mobile users to share their location and retain their mobile phone number or WhatsApp account as they cross borders. This offers multiple opportunities for developing new approaches to health systems research in the future. However, the field of health systems research applying WhatsApp as a tool is in its infancy, and real ethical concerns exist. We urge researchers to be cognizant of the risks associated with the use of WhatsApp, to systematically document their use of the application, and to share how they address ethical challenges and concerns around data security.

The authors would like to thank Langa Mlotshwa for her input to the manuscript. We would also like to thank Lenore Longwe and Kwanda Ndaba from the African Centre for Migration & Society, University of the Witwatersrand, and, Faizah Rahshid, Tambu Agere, Hannah Miyanji and Michael Naranjo from the LSHTM, for their administrative support.

This work was supported through the Health Systems Research Initiative (HSRI) in the UK, and is jointly funding by the Department of International Development (DFID), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust. Grant number: MR/S013601/1.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) have declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical considerations No ethical approval was required for this study.

Agarwal S , Lefevre AE , Lee J , WHO mHealth Technical Evidence Review Group et al. 2016 . Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist . BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 352 : i1174 .

Google Scholar

Ahmed A , Vandrevala T , Hendy J , Kelly C , Ala A. 2019 . An examination of how to engage migrants in the research process: building trust through an ‘insider’ perspective . Ethnicity & Health 1 – 20 .

Alencar A. 2020 . Mobile communication and refugees: an analytical review of academic literature . Sociology Compass 14 : e12802 .

Alencar A , Kondova K , Ribbens W. 2019 . The smartphone as a lifeline: an exploration of refugees’ use of mobile communication technologies during their flight . Media, Culture & Society 41 : 828 – 44 .

Almenara-Niebla S , Ascanio-Sánchez C. 2020 . Connected Sahrawi refugee diaspora in Spain: gender, social media and digital transnational gossip . European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 : 768 – 83 .

Alsohibani A , Alkheder R , Alharbi M et al. 2019 . Public awareness, knowledge, and attitudes regarding epilepsy in the Qassim region, Saudi Arabia . Epilepsy & Behavior 92 : 260 – 4 .

Araújo ETH , Almeida CAPL , Vaz JR et al. 2019 . Use of social networks for data collection in scientific productions in the health area: integrative literature review . Aquichan 19 : 1 – 12 .

Arroz JA , Candrinho BN , Mussambala F et al. 2019 . WhatsApp: a supplementary tool for improving bed nets universal coverage campaign in Mozambique . BMC Health Services Research 19 : 86 .

Bacishoga KB , Hooper VA , Johnston KA. 2016 . The role of mobile phones in the development of social capital among refugees in South Africa . The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 72 : 1 – 21 .

Barbosa S , Milan S. 2019 . Do not harm in private chat apps: ethical issues for research on and with WhatsApp . Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 14 : 49 – 65 .

Bayona E , Menacho L , Segura ER et al. 2017 . The experiences of newly diagnosed men who have sex with men entering the HIV Care Cascade in Lima, Peru, 2015–2016: a qualitative analysis of counselor–participant text message exchanges . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 20 , 389 – 396 .

Google Preview

Bervell B , Al-Samarraie H. 2019 . A comparative review of mobile health and electronic health utilization in sub-Saharan African countries . Social Science & Medicine 232 : 1 – 16 .

Bloomfield GS , Vedanthan R , Vasudevan L et al. 2014 . Mobile health for non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the literature and strategic framework for research . Globalization and Health 10 : 49 .

Blumenstock JE , Eagle N. 2010 . Mobile divides: gender, socioeconomic status, and mobile phone use in Rwanda. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development . pp. 1-10. http://www.gg.rhul.ac.uk/ict4d/ictd2010/papers/ICTD2010%20Blumenstock%20et%20al.pdf , last accessed 22 February 2021.

Boase J. 2013 . Implications of software-based mobile media for social research . Mobile Media & Communication 1 : 57 – 62 .

Buchanan EA , Hvizdak EE. 2009 . Online survey tools: ethical and methodological concerns of human research ethics committees . Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 4 : 37 – 48 .

Cáceres C , Cueto M , Palomino N. 2008 . Policies around sexual and reproductive health and rights in Peru: conflict, biases and silence . Global Public Health 3 : 39 – 57 .

Church K , DE Oliveira R. 2013 . What's up with WhatsApp? Comparing mobile instant messaging behaviors with traditional SMS. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services . pp. 352 – 361 .

DA Silva Braga R. 2016 . Technologies as a means, meetings as an end: urban interactions of a migrant community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, mobilized through WhatsApp. In: Abdelnour-Nocera J, Strano M., Ess C, Van der Velden M, Hrachovec H. (eds) Culture, Technology, Communication. Common World, Different Futures. CaTaC 2016. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 490 . Springer, Cham. pp. 68 – 81 .

Dahir AL. 2018 . WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app in Africa. Quartz Africa , 745 https://qz.com/africa/1206935/whatsapp-is-the-most-popular-messaging-app-in-africa/ , last accessed 22 February 2021.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, S. A . 2020 . COVID-19 Connect South Africa [Online]. Praekelt Foundation. https://www.praekelt.org/covid-19-response-in-sa , last accessed 23 June 2020.

Duvell F , Triandafyllidou A , Vollmer B. 2008 . Ethical issues in irregular migration research. In: Prepared for Work Package of Two of the Research Project CLANDESTINO, Undocumented Migration: Counting the Uncountable, Data and Trends Across the Europe, European Commission, Brussels.

Endeley RE. 2018 . End-to-end encryption in messaging services and national security—case of WhatsApp messenger . Journal of Information Security 09 : 95 – 9 .

Farai SF. 2020 . WHO is raising coronavirus awareness globally using a WhatsApp bot developed in South Africa. https://qz.com/africa/1826415/coronavirus-who-adopts-south-african-whatsapp-health-alert/ , last accessed 17 June 2020.

Fardousi N , Douedari Y , Howard N. 2019 . Healthcare under siege: a qualitative study of health-worker responses to targeting and besiegement in Syria . BMJ Open 9 : e029651 .

Fiesler C , Hallinan B. 2018 . “We are the product” public reactions to online data sharing and privacy controversies in the media. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems(CHI ’18), Montreal, QC, Canada, pp. 1 – 13 .

Frouws B , Phillips M , Hassan A , Twigt M. 2016 . Getting to Europe the WhatsApp way: the use of ICT in contemporary mixed migration flows to Europe. In: Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat Briefing Paper . Nairobi, Kenya: Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat.

Ganguly M. 2017 . WhatsApp design feature means some encrypted messages could be read by third party. In: The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jan/13/whatsapp-design-feature-encrypted-messages , last accessed 22 February 2021.

Gesser-Edelsburg A , Shahbari NAE , Cohen R et al. 2019 . Differences in perceptions of health information between the public and health care professionals: nonprobability sampling questionnaire survey . Journal of Medical Internet Research 21 : e14105 .

Godin M , Donà G. 2020 . Rethinking transit zones: migrant trajectories and transnational networks in Techno-Borderscapes . Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 1 – 17 .

Grant MJ , Booth A. 2009 . A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal 26 : 91 – 108 .

Greene A. 2020 . Mobiles and ‘making do’: Exploring the affective, digital practices of refugee women waiting in Greece . European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 : 731 – 48 .

Hackett KM , Kazemi M , Sellen DW. 2018 . Keeping secrets in the cloud: mobile phones, data security and privacy within the context of pregnancy and childbirth in Tanzania . Social Science & Medicine 211 : 190 – 7 .

Hampshire K , Porter G , Owusu SA et al. 2015 . Informal m-health: how are young people using mobile phones to bridge healthcare gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa? Social Science & Medicine 142 : 90 – 9 .

Hazzam J , Lahrech A. 2018 . Health care professionals’ social media behavior and the underlying factors of social media adoption and use: quantitative study . Journal of Medical Internet Research 20 : e12035 .

Henry JV , Winters N , Lakati A et al. 2016 . Enhancing the supervision of community health workers with WhatsApp mobile messaging: qualitative findings from 2 low-resource settings in Kenya . Global Health: Science and Practice 4 : 311 – 25 .

Karim HMR , Sinha M , Kumar M , Khetrapal M , Dubey R. 2019 . An observation from an online survey: is fresh gas flow used for sevoflurane and desflurane different from isoflurane based anesthesia? Medical Gas Research 9 : 13 .

Kaufmann K. 2018a . Navigating a new life: Syrian refugees and their smartphones in Vienna . Information, Communication & Society 21 : 882 – 98 .

Kaufmann K. 2018b . The smartphone as a snapshot of its use: mobile media elicitation in qualitative interviews . Mobile Media & Communication 6 : 233 – 46 .

Kaufmann K , Peil C. 2019 . The Mobile Instant Messaging Interview (MIMI): Using WhatsApp to Enhance Self-Reporting and Explore Media Usage in Situ. Mobile Media & Communication , Vol. 8(2), pp. 229 – 246 .

Khalid GM , Jatau AI , Ibrahim UI et al. 2019 . Antibiotics self-medication among undergraduate pharmacy students in Northern Nigeria . Medicine Access @ Point of Care 3 : 239920261984684 .

Khoso A , Thambiah S , Hussin H. 2020 . Social practices of Pakistani migrant workers in Malaysia: conserving and transforming transnational affect . Emotion, Space and Society 37 : 100742 .

Kimmel L , Kestenbaum J. 2014 . What's up with WhatsApp: a transatlantic view on privacy and merger enforcement in digital markets . Antitrust 29 : 48 .

Lavallee M , Robillard P-N , Mirsalari R. 2014 . Performing systematic literature reviews with novices: an iterative approach . IEEE Transactions on Education 57 : 175 – 81 .

Lee S , Cho Y-M , Kim S-Y. 2017 . Mapping mHealth (mobile health) and mobile penetrations in sub-Saharan Africa for strategic regional collaboration in mHealth scale-up: an application of exploratory spatial data analysis . Globalization and Health 13 : 63 .

Lim SS , Pham B. 2016 . ‘If you are a foreigner in a foreign country, you stick together’: technologically mediated communication and acculturation of migrant students . New Media & Society 18 : 2171 – 88 .

Lima ICVD , Galvão MTG , Pedrosa SC et al. 2019 . Instant messaging application for the care of people living with HIV/aids . Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 72 : 1161 – 6 .

Madziyire M , Mateveke B , Gidiri M. 2017 . Beliefs and practices in using misoprostol for induction of labour among obstetricians in Zimbabwe . South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 23 : 24 – 7 .

Mancini T , Sibilla F , Argiropoulos D , Rossi M , Everri M. 2019 . The opportunities and risks of mobile phones for refugees’ experience: a scoping review . PLoS One 14 : e0225684 .

Marchetti-Mercer MC , Swartz L. 2020 . Familiarity and separation in the use of communication technologies in South African migrant families . Journal of Family Issues 41 : 1859 – 84 .

Markham A , Buchanan E. 2012 . Ethical decision-making and internet research: Version 2.0. Recommendations from the AoIR ethics working committee. https://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf , last accessed 22 February 2021.

Mattelart T. 2019 . Media, communication technologies and forced migration: promises and pitfalls of an emerging research field . European Journal of Communication 34 : 582 – 93 .

Munn Z , Peters MD , Stern C et al. 2018 . Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach . BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 : 143 .

Murphy LL , Priebe AE. 2011 . “My co-wife can borrow my mobile phone!” Gendered geographies of cell phone usage and significance for Rural Kenyans . Gender, Technology and Development 15 : 1 – 23 .

Noordam AC , Kuepper BM , Stekelenburg J , Milen A. 2011 . Improvement of maternal health services through the use of mobile phones . Tropical Medicine & International Health 16 : 622 – 6 .

O’Connor S , Hanlon P , O’Donnell CA et al. 2016 . Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies . BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 16 : 120 .

Pham MT , Rajić A , Greig JD et al. 2014 . A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency . Research Synthesis Methods 5 : 371 – 85 .

Pimmer C , Mhango S , Mzumara A , Mbvundula F. 2017 . Mobile instant messaging for rural community health workers: a case from Malawi . Global Health Action 10 : 1368236 .

Pindayi B. 2017 . Social media uses and effects: the case of Whatsapp in Africa. In: Nelson O, Oyebuyi BR and Salawu A (eds) Impacts of the Media on African Socio-economic Development. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Raiman L , Antbring R , Mahmood A. 2017 . WhatsApp messenger as a tool to supplement medical education for medical students on clinical attachment . BMC Medical Education 17 : 7 .

Rasidi MQZBM , Varma MA. 2017 . Knowledge, attitude and practice on hyposalivation in complete denture patients among dental interns in Chennai, India . Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 9 : 225 .

Rathbone AP , Norris R , Parker P et al. 2020 . Exploring the use of WhatsApp in out-of-hours pharmacy services: a multi-site qualitative study . Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 16 : 503 – 10 .

Scriven A , Smith-Ferrier S. 2003 . The application of online surveys for workplace health research . Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 123 : 95 – 101 .

Seebregts C , Dane P , Parsons AN et al. 2018 . Designing for scale: optimising the health information system architecture for mobile maternal health messaging in South Africa (MomConnect) . BMJ Global Health 3 : e000563 .

Shambare R. 2014 . The adoption of WhatsApp: breaking the vicious cycle of technological poverty in South Africa . Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 6 : 542 – 50 .

Shitu Z , Jatau A , Mustapha M et al. 2019 . Factors associated with an interest in practice-based research among pharmacists in Nigeria . Journal of Pharmacy Technology 35 : 98 – 104 .

Tagg C , Lyons A , Hu R , Rock F. 2017 . The ethics of digital ethnography in a team project . Applied Linguistics Review 8 : 271 – 92 .

Tyagi N , Goel SA , Alexander M. 2019 . Improving quality of life after spinal cord injury in India with telehealth . Spinal Cord Series and Cases 5 : 1 – 5 .

Vearey J. 2018 . Moving forward: why responding to migration, mobility and HIV in South (ern) Africa is a public health priority . Journal of the International AIDS Society 21 : e25137 .

Vearey J , Modisenyane M , Hunter-Adams J. 2017 . Towards a migration-aware health system in South Africa: a strategic opportunity to address health inequity . South African Health Review 2017 : 89 – 98 .

Weeks LC , Strudsholm T. 2008a . A scoping review of research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and the mass media: looking back, moving forward . BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 8 : 1 – 9 .

Weeks LC , Strudsholm T. 2008b . A scoping review of research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and the mass media: looking back, moving forward . BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 8 : 43 .

WHATSAPP . 2020 . Two Billion Users – Connecting the World Privately . https://blog.whatsapp.com/two-billion-users-connecting-the-world-privately , last accessed 17 June 2020.

Zainudeen A , Iqbal T , Samarajiva R. 2010 . Who’s got the phone? Gender and the use of the telephone at the bottom of the pyramid . New Media & Society 12 : 549 – 66 .

- africa south of the sahara

- developing countries

- public health medicine

- research ethics

- health care systems

- quantitative research

- cell phone use

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2237

- Copyright © 2024 The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 09 May 2023

- Correction 06 June 2023

How scientists are using WhatsApp for research and communication

- Christine Ro 0

Christine Ro is a science writer in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

In March, Holly Bik and Virginia Schutte were a few weeks late departing for East Antarctica, where they would collect sea-floor mud to better understand tiny deep-sea invertebrates. The delay was due to a combination of COVID-19 protocols and port congestion.But their time quarantining in a New Zealand hotel as a COVID-19 precaution was productive.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01575-z

Updates & Corrections

Correction 06 June 2023 : An earlier version of this story erroneously stated that the scoping review Thea de Gruchy was involved in was part of the LGBT+ study. They were separate studies.

Ndashimye, F., Hebie, O. & Tjaden, J. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev . https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393221111340 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Manji, K., Hanefeld, J., Vearey, J., Walls, H. & de Gruchy, T. Health Policy Plan. 36 , 774–789 (2021).

Download references

Related Articles

Training: Narrative tools for researchers

Training: Networking for researchers

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk

Comment 15 MAY 24

Interpersonal therapy can be an effective tool against the devastating effects of loneliness

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Inequality is bad — but that doesn’t mean the rich are

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

Faculty Positions& Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Optical and Electronic Information, HUST

Job Opportunities: Leading talents, young talents, overseas outstanding young scholars, postdoctoral researchers.

Wuhan, Hubei, China

School of Optical and Electronic Information, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Postdoc in CRISPR Meta-Analytics and AI for Therapeutic Target Discovery and Priotisation (OT Grant)

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 14/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute created and supported by the...

Human Technopole

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

WhatsApp and other messaging apps in medicine: opportunities and risks

- IM-Point of view

- Published: 15 February 2020

- Volume 15 , pages 171–173, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Marco Masoni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5943-8689 1 &

- Maria Renza Guelfi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0073-5288 1

14k Accesses

40 Citations

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

WhatsApp is a popular messaging application frequently used by physicians and healthcare organizations that can improve the continuity of care and facilitate effective health services provision, especially in acute settings. However WhatsApp does not comply with the rules of the European GDPR and the US HIPA Act. So it is inappropriate to share clinical information via WhatsApp.

For this reason alternatives to Whatsapp are considered. In particular, the features that must have secure messaging apps to be in compliance with GDPR and HIPAA and to protect patient data will be discussed. The aim is to encourage healthcare organizations and physicians to abandon WhatsApp and to adopt one of the many secure messaging apps now available, some of them at no cost.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

WhatsApp: use and regulatory concerns

WhatsApp is an instant messaging application created in 2009 and acquired by the Facebook family of companies in 2014. Mainly used with mobile devices, it also runs on desktop computers. Although asynchronous as e-mail, most users perceive WhatsApp as a synchronous communication tool.

The WhatsApp installation involves the transmission of the contacts list on Facebook Servers and it is possible to select manually the storage of messages. Communication through end-to-end encryption allows the maintainance of data confidentiality because only the sender and the receiver can decipher the message.

Physicians frequently use WhatsApp to communicate with peers. The clinical utility of this communication tool is now emerging, especially in acute settings [ 1 , 2 ]. Other more general benefits are reported: communication improvement and streamline workflows, reduction of phone tags, decreased consultation time, promotion of a collaborative environment to improve the level of healthcare provided to patients [ 3 ].

As far as the European Community is concerned, the use of WhatsApp must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in May 2018, a complex set of rules that allows EU citizens greater control over personal data.

The GDPR does not allow the storage of sensitive data of EU citizens on servers located outside the geographic area of the European Community. Furthermore, faced with a request for access to personal data (Subject Access Request—SAR), organizations are obliged to provide information and to correct or delete it. It is therefore mandatory that hospitals and healthcare centers know where and how the data are stored [ 4 ].