- Politics & Social Sciences

- Anthropology

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- ISBN-10 0198575017

- ISBN-13 978-0198575016

- Publisher Clarendon Press

- Publication date August 21, 1997

- Language English

- Dimensions 9 x 1.5 x 11.4 inches

- Print length 632 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Clarendon Press (August 21, 1997)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 632 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0198575017

- ISBN-13 : 978-0198575016

- Item Weight : 5.15 pounds

- Dimensions : 9 x 1.5 x 11.4 inches

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

Top reviews from other countries.

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Home

- Research Collections

- Interdisciplinary and Peer-Reviewed

Koobi Fora research project, volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology

3.0.CO;2-6">

Collections

- Anthropology, Department of

Remediation of Harmful Language

The University of Michigan Library aims to describe library materials in a way that respects the people and communities who create, use, and are represented in our collections. Report harmful or offensive language in catalog records, finding aids, or elsewhere in our collections anonymously through our metadata feedback form . More information at Remediation of Harmful Language .

Accessibility

If you are unable to use this file in its current format, please select the Contact Us link and we can modify it to make it more accessible to you.

- DOI: 10.2307/530627

- Corpus ID: 131748378

Koobi Fora Research Project, Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- Creighton Gabel , G. Isaac

- Published 21 January 1999

- Journal of Field Archaeology

31 Citations

A technological analysis of the oldowan and developed oldowan assemblages from olduvai gorge, tanzania.

- Highly Influenced

- 10 Excerpts

Early Pleistocene cut marked hominin fossil from Koobi Fora, Kenya

- Briana Pobiner 1 ,

- Michael Pante 2 &

- Trevor Keevil 3

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 9896 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

1 Citations

1439 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Archaeology

- Biological anthropology

Identification of butchery marks on hominin fossils from the early Pleistocene is rare. Our taphonomic investigation of published hominin fossils from the Turkana region of Kenya revealed likely cut marks on KNM-ER 741, a ~ 1.45 Ma proximal hominin left tibia shaft found in the Okote Member of the Koobi Fora Formation. An impression of the marks was created with dental molding material and scanned with a Nanovea white-light confocal profilometer, and the resulting 3-D models were measured and compared with an actualistic database of 898 individual tooth, butchery, and trample marks created through controlled experiments. This comparison confirms the presence of multiple ancient cut marks that are consistent with those produced experimentally. These are to our knowledge the first (and to date only) cut marks identified on an early Pleistocene postcranial hominin fossil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nubian Levallois technology associated with southernmost Neanderthals

The earliest cut marks of Europe: a discussion on hominin subsistence patterns in the Orce sites (Baza basin, SE Spain)

New hominin remains and revised context from the earliest Homo erectus locality in East Turkana, Kenya

Introduction.

While it is assumed that Pliocene and early Pleistocene hominins were sometimes the victims of predation by the many taxa of larger carnivores with which they coexisted, taphonomic evidence for such interactions in the form of carnivore chewing damage or tooth marks on hominin fossils is relatively uncommon. In 2011, Hart and Sussman 1 listed 10 hominins dated to between 6 million years ago and 50,000 years ago with evidence of terrestrial carnivore or raptor predation; this list does not include carnivore damage on Australopithecus anamensis fossils from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya 2 , 3 and Australopithecus africanus fossils from Member 4 of Sterktfontein, South Africa 4 ; a tooth mark on the pelvis of the AL 288–1 (“Lucy”) Australopithecus afarensis partial skeleton from Hadar, Ethiopia ( 5 , though see 6 for an alternate interpretation of this mark); tooth marks on the Paranthropus robustus SK 54 cranium from Swartkrans, South Africa 7 ; and at least two Homo habilis specimens from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania with evidence of crocodile predation 8 .

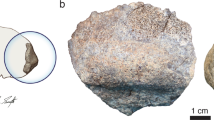

In July 2017, one of us (Pobiner) undertook a pilot study of the taphonomy of published hominin postcranial fossils from the Turkana region of Kenya dated to ~ 1.8 to 1.5 Ma, with an expectation of potentially finding some carnivore damage on these fossils. However, she unexpectedly observed potential butchery marks on a single fossil: KNM-ER 741 (Fig. 1 ). This observation was unexpected because while butchery marks left by hominins on animal fossils beginning by at least the early Pleistocene point to increased meat and marrow acquisition during the evolution of the genus Homo 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 and hundreds of cut marked fossils of other animals have been identified from the Okote Member of the Koobi Fora Formation 13 , 14 , 15 , no cut marks on hominin fossils from this temporal and geographic area have been reported.

Complete view of tibia (KNM-ER 741) and magnified area that shows cut marks perpendicular to the long axis of the specimen. Scale = 4 cm.

In 1970, Mary Leakey found the proximal half of a left tibia, KNM-ER 741 16 , 17 . A surface discovery, Leakey retrieved the fossil from exposures of the Okote Member, Koobi Fora Formation in Area 1 of the Ileret region. While 15 additional hominin specimens were found during the same research expedition in 1970, no additional information is available regarding the discovery of this fossil and the information about it in the Koobi Fora monograph does not specify whether other hominin fossils were found nearby. Its stratigraphic position is noted as “Ileret member, c. 2–4 m above the top of the Lower/Middle Tuff (collection unit 5)” with a depositional environment of “Fluvial, probably the edge of a channel” and additional notes that “The sand matrix on KNM-ER 741, a surface find, indicates association with the channel lens rather than more proximal fine-grained sediments” ( 16 , 17 : 110). Anna K. Behrensmeyer’s unpublished field notes from her 1973 documentation of the context of the site indicate that some faunal specimens were found in the general vicinity of the KNM-ER 741 discovery; a few may have been collected. Her field notes include a description of the surfaces of the tibia as relatively fresh with slight weathering of the bone grain, fine longitudinal cracking which could be pre-depositional weathering, and no major cracks. She observed some dissolution and whitening of the surface, some sand was in the trabeculae exposed along the edge of the proximal articulation, the marrow cavity was hollow without matrix, and the distal break (on the midshaft) had both fresh and ancient fractures (A.K. Behrensmeyer, pers. comm. ).

KNM-ER 741 was originally attributed to Australopithecus boisei when it was first published by Richard Leakey 16 , 17 and then described by Leakey and colleagues 18 . Two decades later, Alan Walker revised the taxonomic attribution of this specimen to Homo erectus based on comparison with KNM-WT 15000, the “Turkana Boy” or Nariokotome partial juvenile skeleton 19 . The entry about KNM-ER 741 in the Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution says “current conventional taxonomic allocation is H. erectus or Hominin gen et sp. indet.” and “because so little is known about the tibial morphology of early hominins other than Australopithecus afarensis it may be premature to rule out the possibility that it belongs to Homo habilis or Paranthropus boisei ” 20 . Due to the taxonomic uncertainty of this fossil, we simply refer to it in this study as a hominin (hominin gen. et sp. indet). The age of the fossil is estimated to be about 1.45 Ma 20 .

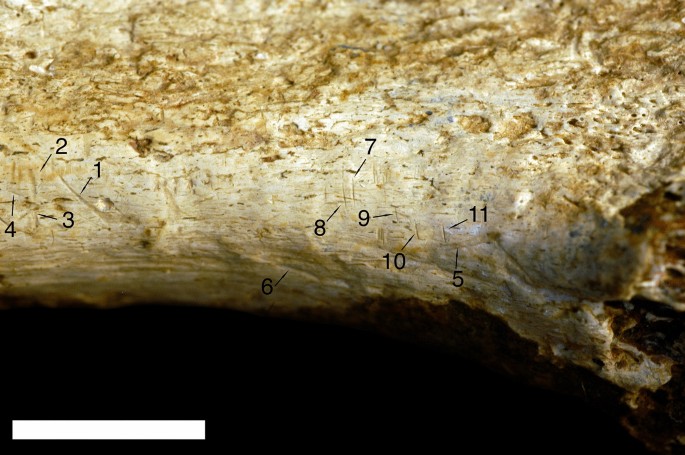

While examining KNM-ER 741 at the National Museums of Kenya Nairobi Museum, Pobiner identified a series of bone surface modifications on the medial side of the proximal shaft which appeared consistent with stone tool cut marks (Fig. 1 ). Pobiner created an impression of 11 of these marks with dental molding material. After she returned to the US, Pobiner sent the molds to Pante and Keevil for analysis and comparison to marks on modern bones made by known processes without any contextual or other information about the bone the marks were on, although Pante knew that she had been doing research at the National Museums of Kenya.

This fossil specimen is a nearly complete proximal tibia with the proximal end, proximal shaft, and midshaft present. The specimen has a transverse and longitudinal (not spiral) ancient and modern fracture on the distal shaft. Most of the surface of this fossil specimen is darkly colored (likely manganese stained) with a poorly preserved, rough appearing cortical surface due to weathering, abrasion, and/or some other physical or chemical process. In the original description of the fossil, it is noted that “the margins of the articular surfaces have been abraded” ( 16 , 17 :110). However, the relatively small area where these marks occur is yellow-whitish colored with very good cortical bone surface preservation. No other bone surface modifications were observed on any other parts of the specimen outside of this area. No information on whether this specimen has undergone any preparation since it was discovered exists, though no preparation or excavation damage was detected. The marks observed and described here are the same color as the rest of the bone surface, so they are unlikely to be modern damage. No cleaning of the marks or any other preparation of this fossil was carried out during this study.

The majority of the bone surface modifications identified and studied here are short, narrow linear marks with a straight trajectory and a closed-V-shaped cross section, oriented in the same direction: transverse and slightly oblique to the long bone axis. The V-shape of these marks and their straight trajectories are strong indicators that they are cut marks 21 . They are not shallow, fine, randomly oriented striae which are randomly distributed on various parts of the fossil; these features are characteristics of sedimentary abrasion 21 . The marks also do not look similar to other non-anthropogenic agents which can inflict linear marks, such as insects, plant roots, or raptor beaks 22 . While internal striations were not observed, this feature can be difficult to observe without higher (at least 40×) magnification. Shoulder effects were observed on some of the marks (Fig. 2 ). Flaking effects were not observed on these marks. Flaking effects are more likely to occur with retouched versus unretouched flakes 21 , and in our experience are less often identified on fossilized bones when compared to modern butchered bones. These marks all occur in the same general area on the shaft of the bone; some are isolated while others occur in groups, adjacent to each other in patches. While it is possible that the marks occurred recently (after the bone was fossilized), we think this is unlikely because the color of the marks is not different from the color of the area of the bone on which they occur, and the marks are neither randomly oriented nor randomly distributed.

3D model of marks 7 and 8 identified as cut marks by the quadratic discriminant model.

Of the 11 marks measured, 9 were classified as cut marks and 2 as tooth marks (Table 1 , Figs. 3 and 4 ). Six of the cut marks were classified with posterior probabilities near or above 90% indicating a high level of confidence in the identification (see Fig. 3 for an image that identifies all of the analyzed marks). This accords with the qualitative observations and descriptions of the marks above. The two marks classified as tooth marks were compared with 163 known marks inflicted by bone crunching carnivores (Hyaenidae, Canidae, Crocodylidae), and 58 known marks from flesh specialist carnivores (Felidae). The quadratic model can discriminate between bone crunching carnivores and flesh specialist felids (only represented by African lions) with 77% accuracy. Results show both marks classify with marks made by flesh specialists with posterior probabilities of 100% (see Fig. 5 for a comparison between mark 5 and a modern lion tooth mark).

Results of quadratic discriminant analysis. Archaeological specimens are identified by their given ID numbers. Circles encompass 50% of the data for each mark type. The model is shown in two dimensions here, but has a third canonical dimension.

Nine marks identified as cut marks (mark numbers 1–4 and 7–11) and two identified as tooth marks (mark numbers 5 and 6) based on comparison with 898 known bone surface modifications using a quadratic discriminant analysis of the micromorphological measurements collected in the study. Scale = 1 cm.

A closeup of mark 5 and the processed 3-D model compared with a modern lion tooth mark.

Human anthropophagy: definitions and taphonomic criteria

Anthropophagy is often used synonymously with cannibalism, but the former can be defined as occasional consumption of humans by other humans while the latter usually implies a cultural practice 23 . Cannibalism is defined as the act of consuming tissues of individuals of the same species 24 and occurs in over 1300 species of animals in the wild, including several primates 25 . In the case of this hominin fossil tibia, we do not know the identity of the species of the consumer (the species which inflicted the butchery marks) nor the consumed (the species of the hominin tibia). Because of this lack of information, we cannot make a claim of cannibalism based on the evidence presented here. However, due to the possibility that an individual of the same species of hominin to which the tibia belongs also inflicted the cut marks on the tibia, we include a discussion about hominin anthropophagy, which can include cannibalism.

Previous researchers have defined and described the various motivations or contexts for human cannibalism in different ways, including: survival; gastronomic or dietary; aggressive; psychotic or criminal; warfare; affectionate; funerary, ritual, spiritual, or magical; and medicinal (e.g., 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ). These types of cannibalism have also sometimes been subdivided into social divisions that include aggressive (consuming enemies) versus affectionate (consuming friends or relatives), or endocannibalism (consumption of individuals within the group, usually associated with sacred beliefs and spiritual regeneration of the deceased) versus exocannibalism (consumption of outsiders, usually associated with hostility and violence) 26 .

Biological anthropologists and archaeologists have generated taphonomic criteria for different kinds of cannibalism to better understand the intent of anthropogenic modification of hominin skeletal remains. These include abundant anthropogenic modifications on more than 20% of human remains; intensive processing of bodies; greater abundance of cut marks related to defleshing and filleting than dismembering; the presence of human tooth marks or chewing damage; and the similar treatment of human and animal remains 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 . Differentiating between nutritional and ritual cannibalism is primarily based on a comparison of the taphonomic traces on and post-processing discard patterns of hominin and non-hominin remains 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 . Evidence for marrow and brain extraction are additional indications of nutritional cannibalism, while ritual cannibalism might be inferred in instances of defleshing without marrow extraction 25 . Saladié et al. 33 recently found that high frequencies of anthropogenic modifications (> 30%) are common after an intensive butchering process intended to prepare a hominin body for consumption in different contexts, contradicting previously held assumptions about cut mark intensity. A full discussion of these past behaviors and the criteria used to identify them are outside the context of this study, though they are briefly summarized here; in order to apply these criteria, richer contextual evidence than what was found with KNM-ER 741 is necessary.

A more recent study by Bello et al. of four archaeological sites (one interpreted as cannibalism and three interpreted as funerary defleshing and disarticulation after a period of decay) determined that a distinction between butchery marks reflecting cannibalism of fresh bodies and secondary burials of bodies at various stages of decomposition can be made based on frequency, distribution, and micromorphometric characteristics of cut marks 34 . This study concluded that cannibalized sites exhibit higher frequencies of cut marks overall, but especially disarticulation cut marks on both persistent and labile joints, while secondary burial sites exhibit low frequencies of cut marks on labile joints because they have been naturally disarticulated over time. Bello et al. found that disarticulation cut marks at the cannibalized site (Gough’s Cave, UK) were deeper and wider than filleting marks at all four archaeological sites, but that filleting marks on long bones associated with larger muscles (humerus, femur, and tibia) were wider and deeper than those on other long bones (radius, ulna, and fibula). They also found that cut marks on the bones from the funerary defleshing sites (Lepenski Vir, Padina, and Vlasac, Serbia) were wider and deeper than cut marks found on other butchered animals at the site, implying the use of more strength to deflesh human bodies, possibly due to “the difficulty in removing remnant tissue on partially desiccated remains” ( 34 :739).

Given the lack of evidence in the Early Pleistocene for primary or secondary burial, or other ritual behaviors, we think only one of the three functional types of human cannibalism outlined by Fernández-Jalvo et al. 26 is potentially applicable to this study: nutritional cannibalism. Nutritional cannibalism occurs for the sole purpose of obtaining food and can be divided into two categories: (1) incidental cannibalism, which is focused on survival; this occurs in periods of food scarcity or due to catastrophes, i.e., is starvation-induced; (2) long duration cannibalism, which is also called gastronomic or dietary cannibalism; humans are simply part of the diet of other humans.

Features of human tooth marks on bones have been identified through experimental studies and applied to some fossil assemblages with other evidence of cannibalism (e.g., 22 , 35 , 36 ). Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews 35 identified bent ends/fraying on thin bones such as ribs and vertebrae apophyses; crenulated or chewed edges, often with a double arch puncture; tooth punctures usually left by molars or premolars which are most often triangular, dispersed, small (< 4 mm), and occur infrequently; and shallow linear marks left by incisors which are usually superficial, less deep and distinct than carnivore tooth scores, and not easily distinguishable without magnification. Saladié et al. 36 further identified furrowing and scooping out of long bone epiphyses; crenulated and saw-toothed edges on flat bones, sometimes associated with notches; longitudinal cracks; crushing; peeling and bent ends; and pits, punctures, and scores. In their study, tooth punctures and pits tended to have irregular contours, including crescent shapes; tooth scores were primarily shallow, some with flaking on the shoulder or bottom of the groove, and a few with microstriations on the core walls and bottoms. These experimental studies were conducted on sheep, pig and rabbits, including some juveniles and subadults, and some raw and some cooked samples 35 , 36 . While there are currently no human tooth marks in our comparative sample, based on the lack of other features of human tooth marks and chewing damage outlined in previous research, and the fact that human tooth marks have most often been identified on modern and fossil bones of smaller sized taxa and skeletal elements than this hominin tibia, we think it is possible but unlikely that the tooth marks on this fossil hominin tibia are hominin tooth marks.

The two BSM classified as tooth marks are most similar to those produced by a felid (Fig. 5 ). In our known sample of tooth marks, felids are only represented by the modern lion. While often considered to be hunters, lions are opportunistic in acquiring carcass foods and scavenge frequently. In wooded habitats lions kill between 78 and 88% of their food, but only kill about 47% of their food in open habitats 37 . This is most likely the result of an abundance of hyenas, from which lions frequently scavenge, and the visibility of vultures that can be followed to kills by lions in open habitats 37 . Lions will also scavenge from leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs, jackals, and when available, from animals that died from disease or malnutrition 37 . Given the variability in lion behavior and the presence of both cut marks and tooth marks on the fossil hominin tibia, it is not possible to infer the cause of death of the individual, or even the primary consumer. However, the location of the cut marks on the posterior tibia shaft suggests that flesh was likely on the carcass at the time that the cut marks were inflicted.

Evidence for Pleistocene hominin butchery marks on hominins

There is uncontested evidence for cannibalism in European Neanderthals from sites in Belgium (Troisième Caverne of Goyet), France (Moula-Guercy and Padrelles), Spain (Cueva del Sidrón and Cueva del Boquete de Zafarraya), and Croatia (Krapina) (see 24 , 25 and references therein). There is also evidence for both anthropogenic defleshing and cannibalism in Homo sapiens from sites in Ethiopia (Herto), Poland (Maszycka Cave), the UK (Gough’s Cave), and possibly Germany (Brillenhöhle) (see 23 and references therein). Yet there are still only a handful of Pleistocene sites with evidence for hominin cannibalism 24 , 25 , and only four published examples of postmortem defleshing on hominin fossils other than Neanderthals and Homo sapiens . We describe these examples in more detail here, in order from youngest to oldest.

Though slightly younger than the Early Pleistocene at ~ 600,000 years old, the first observation of cut marks on an early hominin was made by White 38 on the Bodo cranium from the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia. White identified 17 areas with diagnostic cut marks on the Bodo cranium and used scanning electron microscopy to investigate some of the cut marks. He also studied crania of modern apes intentionally defleshed with steel knives during the early 1900s now housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for comparison. He was able to match the placement and orientation of each set of the Bodo cut marks among these apes, despite differences in gross cranial morphology and tool type employed. He interpreted the marks on the Bodo cranium as patterned intentional postmortem defleshing of this specimen by a hominin with a stone tool 38 .

There is some evidence for processing on some of the at least 30 Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus individuals from Caune de l ‘Argo (also known as Arago Cave) in Tautavel, France, most dated to the ~ 680,000 year old Middle Pleistocene middle G and F levels. While a systematic taphonomic study of this site has not yet been undertaken, de Lumley 39 described the remains, primarily from level G, as showing the presence of abundant cut marks on skulls and limb bones and green breakage of long bones. The difference in skeletal part profiles of hominins and non-hominin animals from Arago Cave led de Lumley to suggest that the hominin bones present at the site—skulls, mandibles, long limb bones, and a pelvic girdle—were anthropogenically selected and possibly related to ritualistic cannibalism. Cole 25 noted that postcranial remains at this site were processed differently than cranial remains, also raising the possibility of ritual cannibalism. However, Saladié and Rodríguez-Hidalgo 24 propose that the near absence of axial bones at Arago Cave could be the result of other processes, such as post-depositional destruction (which is more likely to affect these skeletal elements) or difficulties in taxonomic identification; they suggest that the taphonomic damage on the Arago hominins may not be due to ritual behavior.

Fernández-Jalvo et al. 26 , 40 first identified butchery marks among the ~ 772,000 to 949,000 year old Homo antecessor remains from Gran Dolina, which is part of the karstic site complex of the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern central Spain. The taphonomic analyses of human fossils from the TD6-Aurora Stratum of Gran Dolina, using a binocular light microscope as well as scanning electron microscopy, included identification not only of cut marks (including slicing marks, chop marks, and scraping marks), but also of percussion pits, peeling, conchoidal fracture, and adhering flakes. They found evidence of hominin-induced breakage, butchery marks, and human tooth marks on 44.5% of Homo antecessor bones, including many different skeletal elements, suggesting scalping, skinning, disarticulation, evisceration, and defleshing aimed at meat, marrow, and brain extraction 26 , 40 . The patterning of butchery damage on the Homo antecessor remains was generally similar to the patterning of damage on the non-human animal remains and was consistent with those bones that held the most nutritional value, as was the spatial distribution of human and non-human animal remains 26 , 40 . They found no evidence of ritual treatment and interpreted the butchery mark damage on the assemblage as evidence for nutritional cannibalism, more likely gastronomic cannibalism than survival cannibalism. Carbonell et al. 41 described human meat consumption by Homo antecessor at this site as “frequent and habitual” and concluded that this nutritional cannibalism was accepted and included in their social system. After comparing the age profiles of the butchered Homo antecessor individuals to the age profiles seen in cannibalism associated with intergroup aggression in chimpanzees, Saladié et al. 42 concluded that the Gran Dolina hominins periodically hunted and consumed individuals from another group. With evidence for processing of 11 individuals—2 adults, 3 adolescents, and 6 children 26 —this is arguably the earliest firm evidence of systematic cannibalism in the hominin fossil record, and the only such evidence from the Early Pleistocene.

In 2000, Pickering et al. 43 published what are currently accepted as the oldest cut marks on a hominin fossil: cut marks inflicted by a stone tool on the right maxilla of Stw 53, a partial skull from Sterkfontein Member 5 (or possibly a hanging remnant of Member 4—an area called the STW 53 infill) in South Africa. This skull was first found in 1976 by Alun Hughes and is generally attributed to Homo habilis but is also sometimes argued to represent Australopithecus . Pickering et al. noted that the morphology of the marks, their anatomical placement, and the lack of random striae on the specimen all support an interpretation of this linear damage as cut marks 43 . They state that the location of the marks on the lateral aspect of the zygomatic process of the maxilla is consistent with that expected from slicing through the masseter muscle, presumably to remove the mandible from the cranium, in an act of disarticulation. The age of this fossil is somewhat uncertain; Pickering and Kramers 44 suggest an age between 2.6 and 2.0 Ma, but Wood 20 thinks it is younger, between 2.0 and 1.5 Ma. A more recent reassessment of these marks by Hanon et al. 45 including macro- and microscopic observations concluded that they are not evidence for hominin butchery, but the result of natural processes. They noted that Clarke 46 mentioned that the zygomatic bone of Stw53 was discovered with sharp-edged chert blocks lying against it, which could produce linear marks under sedimentary pressure, and assert that the morphology of these marks is more consistent with trampling marks. Because the marks are located on the masseter muscle insertion of the zygomatic maxillary process they also looked for corresponding marks on the masseter muscle insertion area of the temporal bone, which might be expected in the process of disarticulation or defleshing, but did not find any. While this more recent analysis of the purported cut marks on Stw 53 has not been replicated or confirmed, given the uncertain age of Stw 53, KNM-ER 741 is now at least among the oldest hominin fossils with evidence of hominin butchery marks, and currently is the oldest known hominin butchery marked postcranial fossil.

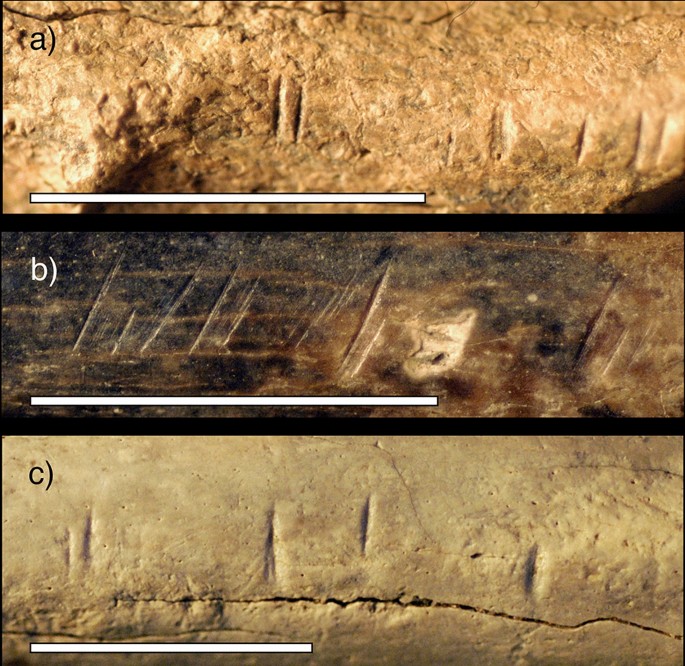

Previous research on butchery marked fauna from multiple sites from the Okote Member of Koobi Fora show that at this time (~ 1.5 million years ago), hominins were consistently using stone tools to deflesh, disarticulate, and extract marrow from a variety of species and sizes of animals from different habitat settings 13 , 14 , 15 . While the morphology of the butchery marks on the Okote Member sites is variable 47 , some generally resemble the marks on KNM-ER 741 (Fig. 6 ). Quantitative analyses of the bone surface modifications on the KNM-ER 741 tibia demonstrate a high level of confidence that the majority were produced by hominins. But what was being cut, exactly, on KNM-ER 741—and why? The cut marks are located on the posterio-medial border of the proximal tibia shaft, near the origin of the popliteus muscle, which rotates the knee medially and flexes the knee joint. The popliteus origin is situated beneath the gastrocnemius, which would have had to be removed for access to the cut marked area. We interpret the location of the cut marks to be more likely the result of defleshing than disarticulation. We conclude that if anthropophagy occurred after the defleshing of KNM-ER 741, it was an opportunistic, practical, and functional activity which occurred simply in the context of obtaining food, rather than one imbued with ritual meaning.

Close up photos of three fossil fauna specimens from archaeological surface finds and excavations in the Okote Member of Koobi Fora (Pobiner 47 ), showing similar cut marks to those found on KNM-ER 741. ( a ) FwJj14B 5097, a bovid size 3 mandible with cut marks on the inferior margin, found in situ ( b ) FwJj14A 1016-97, a bovid size 3 radius midshaft with cut marks, found on the surface ( c ) GaJj14 1056, a large mammal scapula with cut marks along scapular margin, found on the surface. Scale = 1 cm.

Pobiner used a 10X hand lens and bright, high-incident light to look for bone surface modifications on hominin postcranial bones at the National Museums of Kenya, including KNM-ER 741, following methods outlined in Blumenschine et al. 48 . She used Coltene President Plus light body dental molding material to create an impression of the marks analyzed in this study.

The quantitative analysis of bone surface modifications (BSM) followed the protocol presented in Pante et al. 49 . 3-D models of each of the 11 studied BSM were created from an impression of the surface taken from the area of interest on the tibia using a Nanovea ST400 white-light non-contact confocal profilometer equipped with a 3 mm optical pen (objective) that has a resolution of 40 nm on the z-axis. The resolution on the x-axis was set to 5 um and 10 um on the y-axis. Processing and analysis of the 3D model was carried out using Digital Surf's Mountains ® following Pante et al. 49 . Processing included removing outliers, filling in missing data points, and removing the underlying form of the bone. Data collected through the analysis from the entire 3-D model of the BSM were volume, surface area, maximum depth, mean depth, maximum length, and maximum width. Additional data were collected from a profile taken from the deepest point of the BSM including area of the hole, depth of the profile, roughness (Ra), opening angle, and radius of the hole.

These data were statistically compared with a sample of 898 BSM of known origin, including: 402 cut marks from a variety of stone tool types and raw materials; 278 tooth marks from crocodiles and five species of mammalian carnivores; 130 trample marks produced by cows on substrates including sand, gravel, and soil; and 88 percussion marks from both anvils and hammerstones (see Supplemental document 1 for details on the model structure, influential variables, canonical data, and box-cox transformation values). Surface area and depth of the profile were excluded from the statistical analyses because they are highly correlated with volume and maximum depth, respectively, which can lead to overfitting of data. All experimental data were transformed using the Box-Cox method to normalize the distributions for each variable and the same transformations were applied to the archaeological data. Comparisons were carried out using the quadratic discriminant function in JMP® statistical software. The accuracy of the quadratic function in correctly classifying the experimental BSM was 84% when using a 25% validation set. Prior probabilities were set equal to the occurrence of each mark type in the dataset to offset the disproportionate representations of each mark type in the experimental sample.

Data availability

All study data are included in the article.

Hart, D. & Sussman, R. W. The influence of predation on primate and early human evolution: impetus for cooperation. In Origins of Altruism and Cooperation (eds Sussman, R. W. & Cloninger, C. R.) 19–40 (Springer, 2011).

Chapter Google Scholar

Leakey, M. G., Feibel, C. S., McDougall, I., Ward, C. & Walker, A. New specimens and confirmation of an early age for Australopithecus anamensis . Nature 393 , 62–66 (1998).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ward, C. V., Leakey, M. G. & Walker, A. C. The new hominid species Australopithecus anamensis . Evol. Anth. 7 , 197–205 (1999).

Article Google Scholar

Pickering, T. R., Clarke, R. J. & Moggi-Cecchi, J. Role of carnivores in the accumulation of the Sterkfontein Member 4 hominid assemblage: A taphonomic reassessment of the complete hominid fossil sample (1936–1999). Am. J. Phys. Anth. 125 , 1–15 (2004).

Johanson, D. C. et al. Morphology of the Pliocene partial hominid skeleton (A.L. 288-1) from the Hadar formation, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anth. 57 , 403–451 (1982).

Kappelman, J. et al. Reply to: Charlier et al. 2018. Mudslide and/or animal attack are more plausible causes and circumstances of death for AL 288 (‘Lucy’): a forensic anthropology analysis. Medico-Legal Journal 86(3) 139–142, 2018. Med.-Legal J. 87 (3), 121–126 (2018).

Brain, C. K. The Hunters or the Hunted. An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy (The University of Chicago Press, 1981).

Google Scholar

Njau, J. K. & Blumenschine, R. J. Crocodylian and mammalian carnivore feeding traces on hominid fossils from FLK 22 and FLK NN 3, Plio-Pleistocene, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. J. Hum. Evol. 63 (2), 408–417 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pobiner, B. L. The zooarchaeology and paleoecology of early hominin scavenging. Evol. Anth. 29 , 68–82 (2020).

Barr, W. A., Pobiner, B., Rowan, J., Du, A. & Faith, J. T. No sustained increase in zooarchaeological evidence for carnivory after the appearance of Homo erectus . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (5), e2115540119 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Plummer, T. L. et al. Expanded geographic distribution and dietary strategies of the earliest Oldowan hominins and Paranthropus . Science 379 (6632), 561–566 (2023).

Espigares, M. P. et al. The earliest cut marks of Europe: A discussion on hominin subsistence patterns in the Orce sites (Baza basin, SE Spain). Sci. Rep. 9 , 15408 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pobiner, B. L., Rogers, M. J., Monahan, C. M. & Harris, J. W. K. New evidence for hominin carcass processing strategies at 1.5 Ma, Koobi I, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 55 (1), 103–130 (2008).

Merritt, S. R. Investigating hominin carnivory in the Okote Member of KoIFora, Kenya with an actualistic model of carcass consumption and traces of butchery on the elbow. J. Hum. Evol. 112 , 105–133 (2017).

Merritt, S. R., Mavuso, S., Cordiner, E. A., Fetchenhier, K. & Greiner, E. FwJj70: A potential early stone age single carcass butchery locality preserved in a fragmentary surface assemblage. J. Arch. Sci. Rep. 20 , 736–747 (2018).

Leakey MG, Leakey RE, editors. Koobi Fora Research Project Volume 1: The Fossil Hominids and an Introduction to Their Context, 1968-1974. Oxford University Press; 1977. 191 pp.16.

Leakey, R. E. Further evidence of lower Pleistocene hominids from East Rudolf, North Kenya. Nature 231 (5300), 241–245 (1971).

Leakey, R. E. Further evidence of lower Pleistocene hominids from East Rudolf, North Kenya, 1972. Nature 242 (5394), 170–173 (1973).

Walker A, Leakey R, editors. The Nariokotome Homo Erectus Skeleton. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1993. 458 pp.

Wood, B. Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution 1922 (Wiley, 2011).

Book Google Scholar

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., de Juana, S., Galán, A. B. & Rodríguez, M. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks. J. Arch. Sci. 36 (12), 2643–2654 (2019).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. Atlas of Taphonomic Identifications. 1001+ Images of Fossil and Recent Mammal Bone Modification 360 (Springer, 2016).

Cole, J. Assessing the calorific significance of episodes of human cannibalism in the Palaeolithic. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 44707 (2017).

Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Saladié, P. & Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. Archaeological evidence for cannibalism in prehistoric western Europe: From Homo antecessor to the Bronze Age. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 24 (4), 1034–1071 (2017).

Cole J. Consuming passions: Reviewing the evidence for cannibalism within the Prehistoric archaeological record [Internet]. Ass–mblage: Sheff. Grad. J. Archaeol. 9 (2006).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Carlos Díez, J., Cáceres, I. & Rosell, J. Human cannibalism in the Early Pleistocene of Europe (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 37 (3), 591–622 (1999).

Turner, C. G. I. & Turner, J. A. Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest (University of Utah Press, 1999).

Knüsel, C. & Outram, A. Fragmentation of the body: Comestibles, compost, or customary rite?. Soc. Archaeol. Funer. Remains 1 , 253 (2006).

White, T. Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346 (Princeton, 1992).

Tutt, C. M. A. Cannibalism among fossil hominids: Is there archaeological evidence?. Totem: Univ. West Ontario J Anth. 11 (1), 113–120 (2003).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. Butchery, art or rituals. J. Anthro. Archeo. Sci. 3 (3), 383–392 (2021).

Villa, P. et al. Cannibalism in the Neolithic. Science 233 (4762), 431–437 (1986).

Saladié, P. et al. Experimental butchering of a chimpanzee carcass for archaeological purposes. PLoS ONE 10 (3), e0121208 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bello, S. M., Wallduck, R., Dimitrijević, V., Živaljević, I. & Stringer, C. B. Cannibalism versus funerary defleshing and disarticulation after a period of decay: Comparisons of bone modifications from four prehistoric sites. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 161 (4), 722–743 (2016).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. When humans chew bones. J. Hum. Evol. 60 (1), 117–123 (2011).

Saladié, P., Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A., Díez, C., Martín-Rodríguez, P. & Carbonell, E. Range of bone modifications by human chewing. J. Arch. Sci. 40 , 380–397 (2013).

Schaller, G. B. The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator Prey Relations (Chicago University Press, 1972).

White, T. D. Cut marks on the Bodo cranium: A case of prehistoric defleshing. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 69 (4), 503–509 (1986).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

de Lumley, M.-A. L’homme de Tautavel. Un Homo erectus européen évolué Homo erectus tautavelensis. L’Anthropologie 119 (3), 303–348 (2015).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Díez, J. C., de Castro, J. M. B., Carbonell, E. & Arsuaga, J. L. Evidence of early cannibalism. Science 271 (5247), 277–278 (1996).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Carbonell, E. et al. Cultural cannibalism as a paleoeconomic system in the European Lower Pleistocene. Curr. Anthropol. 51 (4), 539–549 (2010).

Saladié, P. et al. Intergroup cannibalism in the European Early Pleistocene: The range expansion and imbalance of power hypotheses. J. Hum. Evol. 63 (5), 682–695 (2012).

Pickering, T. R., White, T. D. & Toth, N. Brief communication: Cutmarks on a Plio-Pleistocene hominid from Sterkfontein, South Africa. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 111 , 579–584 (2000).

Pickering, R. & Kramers, J. D. Re-appraisal of the stratigraphy and determination of new U-Pb dates for the Sterkfontein hominin site, South Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 59 (1), 70–86 (2010).

Hanon, R., Péan, S. & Prat, S. Reassessment of anthropic modifications on the Early Pleistocene hominin specimen Stw53 (Sterkfontein, South Africa). Bull. Mém Soc. Anthropol. Paris 30 , 49–58 (2018).

Clarke R. Australopithecus from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. In: The Paleobiology of Australopithecus . 2013. pp 105–23.

Pobiner B. Hominin-carnivore interactions: evidence from modern carnivore bone modification and Early Pleistocene archaeofaunas (Koobi Fora, Kenya; Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania). 2007; PhD Dissertation, Rutgers University.

Blumenschine, R. J., Marean, C. W. & Capaldo, S. D. Blind tests of inter-analyst correspondence and accuracy in the identification of cut marks, percussion marks, and carnivore tooth marks on bone surfaces. J. Archaeol. Sci. 23 , 493–507 (1996).

Pante, M. C. et al. A new high-resolution 3-D quantitative method for identifying bone surface modifications with implications for the Early Stone Age archaeological record. J. Hum. Evol. 102 , 1–11 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Pobiner acknowledges the Peter Buck Fund for Human Origins Research for funding support and the National Museums of Kenya for permission to study KNM-ER 741 and logistical support. Pante acknowledges the College of Liberal Arts and Department of Anthropology and Geography, Colorado State University for funding the purchase of the profilometer used in the study, and also Emily Orlikoff, April Tolley, and Matthew Muttart for their contributions to the creation of the actualistic database of bone surface modification models. We thank Jennifer Clark for specimen photography, Peter Nassar for assistance with human tibia anatomy and musculature, and Tom Mukhuyu and Anna K. Behrensmeyer for archival research assistance. We also thank the editor, four reviewers, and Mica Glantz for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Human Origins Program, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 20013, USA

Briana Pobiner

Department of Anthropology and Geography, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, 80523, USA

Michael Pante

Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA

Trevor Keevil

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.P. designed the project. B.P. conducted the study of the original fossil material. M.P. and T.K. conducted the analysis comparing the ancient marks on the fossil tibia to the modern marks and interpreted the results. M.P. produced the tables and figures. B.P. and M.P. wrote the manuscript. B.P., M.P., and T.K. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Briana Pobiner .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pobiner, B., Pante, M. & Keevil, T. Early Pleistocene cut marked hominin fossil from Koobi Fora, Kenya. Sci Rep 13 , 9896 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35702-7

Download citation

Received : 19 December 2022

Accepted : 22 May 2023

Published : 26 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35702-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Did our human ancestors eat each other carved-up bone offers clues.

- Lilly Tozer

Nature (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Find a Store

- Watch List Expand Watch list Loading... Sign in to see your user information

- My eBay Summary

- Recently Viewed

- Bids/Offers

- Purchase History

- Selling/Sold

- Saved Searches

- Saved Sellers

- My Messages

- Get Exclusive Savings

- Expand cart Loading... Something went wrong. View cart for details.

Picture 1 of 2

Koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology by barbara isaac, glynn ll. isaac (hardcover, 1997).

- simplybestprices-10to20dayshipping (473670)

- 98.3% positive Feedback

- Add to cart

- See all details

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.

Refresh your browser window to try again.

About this product

Product information.

- This is the fifth volume in the important Koobi Fora series on human origins, covering archaeological finds from excavations at East Turkana in northern Kenya. Volume 5 concentrates on the evidence from the period between 1.9 and 0.7 million years ago and reconstructs the behaviour of early human ancestors. The book answers such questions as: How were the stone tools made and utilized? How large were the groups of hominids, and how mobile? Do animal bones really give us a true impression of what food they ate? The stone artefacts, bones, and features of the ancient landscape recorded in this book provide a solid basis for further work on human evolution.

Product Identifiers

- Publisher Oxford University Press

- ISBN-13 9780198575016

- eBay Product ID (ePID) 95952821

Product Key Features

- Number of Pages 632 Pages

- Language English

- Publication Name Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- Publication Year 1997

- Subject Archaeology, Anthropology, Biology, History

- Type Textbook

- Author Barbara Isaac, Glynn Ll. Isaac

- Format Hardcover

- Item Height 314 mm

- Item Weight 2389 g

- Item Width 228 mm

Additional Product Features

- Editor Glynn Ll. Isaac, Barbara Isaac

- Country/Region of Manufacture United Kingdom

- Series Title Koobi Fora Research Project

Best Selling in Adult Learning & University

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- Best Selling in Adult Learning & University

Nonviolent Communication 3rd Ed by Rosenberg M (Paperback, 2015)

- AU $20.16 New

- AU $18.33 Used

The Art of Electronics by Paul Horowitz, Winfield Hill (Hardcover, 2015)

- AU $135.00 New

- AU $97.23 Used

A Practical Guide to Writing: Psychology, 4th Edition by Carla Taines (Paperback, 2018)

- AU $90.99 New

Jaws: The Story of a Hidden Epidemic by Paul Ehrlich, Paul R. Ehrlich (Paperback, 2021)

- AU $50.26 New

- AU $42.56 Used

Capital: Volume III by Karl Marx (Paperback, 1992)

- AU $39.23 New

- AU $34.90 Used

Building Your Own Home: A Comprehensive Guide for Owner-builders by George Wilkie (Paperback, 2019)

- AU $53.60 New

- AU $30.00 Used

Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland by Christopher R. Browning (2001, Paperback)

- AU $28.07 New

- AU $20.00 Used

Save on Adult Learning & University

Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days.

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- Save on Adult Learning & University

The Art of Electronics 3rd Edition by Paul Horowitz (English) Hardcover Book

Empire of the summer moon: quanah parker and the rise and fall of the comanches,, the discovery of the unconscious: the history and evolution of dynamic psychiatr, the writing revolution: a guide to advancing thinking through writing in all sub, ethics and legal professionalism in australia 3rd edition by paula baron (englis, pedagogy of the oppressed, you may also like.

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- You may also like

Isaac Asimov Fiction & Fiction Books

Isaac asimov fiction & fiction books in english, isaac asimov fiction paperback fiction & books, isaac asimov fiction & non-fiction books, isaac bashevis singer fiction fiction & books.

Mission statement

The continued research in the Turkana Basin will further the global understanding of human origins and the context in which it occurred through the recovery and investigation of new fossil material from deposits in northern Kenya.

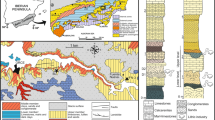

THE KOOBI FORA REGION has, over the last 35 years of exploration, produced a wealth of paleontological, geological and archaeological data. Research in the area has revealed a complex history of volcanism, tectonics and sedimentary cycles preserving fluvial and lake phases of the basin. Some 16,000 fossil specimens have been collected from the Turkana basin, almost 10,000 from the Koobi Fora Region.

You might also like:

- उच्च शिक्षा पाठ्यपुस्तकें

- विज्ञान और गणित

क्षमा करें, कोई समस्या हुई थी.

मुफ्त Kindle ऐप डाउनलोड करें और अपने स्मार्टफ़ोन, टैबलेट या कंप्यूटर पर तुरन्त Kindle किताबें पढ़ना शुरू करें - किसी Kindle डिवाइस की आवश्यकता नहीं है .

Kindle for Web के साथ अपने ब्राउज़र पर तुरंत पढ़ें.

अपने मोबाइल फ़ोन के कैमरे का उपयोग करके - नीचे दिए गए कोड को स्कैन करें और Kindle ऐप डाउनलोड करें.

इमेज उपलब्ध नहीं है

- इस वीडियो डाउनलोड को देखने के लिए फ़्लैश प्लेयर

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology हार्डकवर – इम्पोर्ट, 12 जून 1997

इसके साथ अतिरिक्त बचत करें 3 ऑफ़र करता है, 10 दिनों में रिप्लेसमेंट.

| रिप्लेसमेंट कारण | रिप्लेसमेंट अवधि | रिप्लेसमेंट पॉलिसी |

|---|---|---|

| शारीरिक क्षति, गलत और अनुपलब्ध आइटम, खराब | डिलीवरी से 10 दिन | रीप्लेसमेंट |

रिप्लेसमेंट संबंधी निर्देश

खरीदारी के विकल्प और ऐड-ऑन

- प्रिंट की लम्बाई 632 पेज

- भाषा अंग्रेज़ी

- प्रकाशक Clarendon Press

- प्रकाशन की तारीख 12 जून 1997

- आकार 22.86 x 3.81 x 28.96 cm

- ISBN-10 0198575017

- ISBN-13 978-0198575016

- पूरा विवरण देखें

प्रोडक्ट का विवरण

- प्रकाशक : Clarendon Press (12 जून 1997)

- भाषा : अंग्रेज़ी

- हार्डकवर : 632 पेज

- ISBN-10 : 0198575017

- ISBN-13 : 978-0198575016

- आइटम का वज़न : 2 kg 340 g

- आकार : 22.86 x 3.81 x 28.96 cm

ग्राहकों की समीक्षाएं

- 5 स्टार 4 स्टार 3 स्टार 2 स्टार 1 स्टार 5 स्टार 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100%

- 5 स्टार 4 स्टार 3 स्टार 2 स्टार 1 स्टार 4 स्टार 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 स्टार 4 स्टार 3 स्टार 2 स्टार 1 स्टार 3 स्टार 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 स्टार 4 स्टार 3 स्टार 2 स्टार 1 स्टार 2 स्टार 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 स्टार 4 स्टार 3 स्टार 2 स्टार 1 स्टार 1 स्टार 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- समीक्षाओं को इसके अनुसार क्रमबद्ध करें टॉप समीक्षाएं सबसे हाल ही का टॉप समीक्षाएं

भारत से टॉप समीक्षा

अन्य देशों से टॉप समीक्षा.

- हमारे बारे में जानकारी

- प्रेस विज्ञप्तियां

- Amazon Science

- Amazon पर बेचें

- 'Amazon के लिए बने ब्रांड' के तहत बेचें

- अपने ब्रांड को सुरक्षित रखें और बनाएं

- Amazon ग्लोबल सेलिंग

- Amazon को सप्लाई

- Amazon द्वारा फुलफिलमेंट

- अपने प्रोडक्ट का विज्ञापन दें

- Merchants पर Amazon pay

- आपका अकाउंट

- वापसी केंद्र

- रिकॉल और प्रोडक्ट सुरक्षा अलर्ट

- 100% सुरक्षा खरीदारी पर

- Amazon ऐप डाउनलोड

- उपयोग और बिक्री की शर्तें

- गोपनीयता सूचना

- रुचि-आधारित विज्ञापन

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5 - Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology (Hardcover)

Or split into 4x interest-free payments of 25% on orders over R50 Learn more

Donate to Against Period Poverty

Product Description

Customer reviews, no reviews or ratings yet - be the first to create one, product details.

| Clarendon Press | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Koobi Fora Research Project | |

| June 1997 | |

| Expected to ship within 12 - 17 working days | |

| , | |

| 314 x 228 x 37mm (L x W x T) | |

| Hardcover | |

| 632 | |

| 978-0-19-857501-6 | |

| 9780198575016 | |

| 0-19-857501-7 |

Be the first to know about our latest deals & promos! Subscribe Now

- New Customer

- Competitions

- Subscriptions

- Gift Vouchers

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Contact Details

- Arts & Crafts

- DIY & Tools

- Electronics

- Health & Beauty

- Kitchen & Appliances

- Movies & TV

- Stationery & Office

COPYRIGHT © 2024 AFRICA ONLINE RETAIL (PTY) LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Khutaza Park, 27 Bell Crescent, Westlake Business Park. PO Box 30836, Tokai, 7966, South Africa. [email protected] All prices displayed are subject to fluctuations and stock availability as outlined in our Terms & Conditions

Early Homo Occupation Near the Gate of Tears : Examining the Paleoanthropological Records of Djibouti and Yemen

Cite this chapter.

- Parth R. Chauhan 3

Part of the book series: Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology ((VERT))

1424 Accesses

7 Citations

The Bab al-Mandab region has often been considered a primary crossing point for early hominins following a southern coastal route from East Africa to South and Southeast Asia. However, surprisingly little work has been done in the countries of Djibouti and Yemen, both of which hold the key to our understanding of the chronological, paleoenvironmental and adaptive contexts of such early movements. As a result, detailed and accurate information about hominin subsistence, raw material exploitation, climatic adaptations, and the rate and success of early dispersals in such regions still remain poorly understood. Being a part of the Rift Valley, Djibouti shows great potential for paleoanthropological research in parity with the rest of East Africa. Only one Oldowan site, near Lake Abbé, is currently known and dated to between 1.6 and 1.3 Ma by ESR, with presumably butchered remains of Elephas recki ileretensis and hundreds of artifacts on lavas. In addition, a complete articulated skeleton of Elephas recki recki was found in clays of the comparatively younger Gobaad Formation. Previous investigators have also reported a fragmentary maxilla, attributed to an older form of Homo sapiens and dated to ~250 Ka, from the valley of the Dagadlé Wadi. In Yemen and other parts of the Arabian Peninsula, archaeological investigations by numerous workers have yielded an abundance of Lower Paleolithic sites near the mountains and on fan surfaces, particularly in the Hadramaut area and the Tihama Plains, including the Al-Guza cave site with possible Oldowan artifacts. Surveys 25 to 40 km inland from the Gulf of Aden, South of Yemen, have yielded almost 40 Lower Paleolithic sites, including several Oldowan sites. Despite these commendable efforts, however, vast parts of both Djibouti and Yemen remain largely unexplored and much of the known evidence from both regions has not been absolutely dated or excavated. Until this is done, such data lend little support to early dispersal models that incorporate a southern coastal route to Southeast Asia during the Late Pliocene. This paper attempts to highlight and assess the earliest-known Mode 1 and Mode 2 evidence from Djibouti and Yemen, and correlate them with the available Plio-Pleistocene environmental records of the Bab al-Mandab region. Another objective is to provide a detailed synthesis of the original French publications on the paleoanthropological evidence from Djibouti, thus making it more widely available for comparative purposes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Omo Kibish, Ethiopia

Pleistocene archaeology of the republic of djibouti, sidi abderrahmane quarries, morocco.

Abbate, E., Albianelli, A., Azzaroli, A., Benvenuti, M., Tesfamariam, B., Bruni, P., Cipriani, N., Clarke, R.J., Ficcarelli, G., Macchiarelli, R., Napoleone, G., Papini, M., Rook, L., Sagri, M., Tecle, T.M., Torre, D., Villa, I. 1998. A one-million-year-old Homo cranium from the Danakil (Afar) Depression of Eritrea. Nature 393, 458–460.

Article Google Scholar

Amirkhanov, H.A., 1994. Research on the Palaeolithic and Neolithic of Hadhramaut and Mahra. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5, 217–228.

Amirkhanov, H.A. 1999. Archaeological Evidence for Early Hominid Migration to the Arabian Peninsula. Anthropologie 37, 45–50.

Google Scholar

Amirkhanov, H.A., 2006. Stone Age of South Arabia. Nauka, Moscow.

Anton, S.C., Leonard, W.R., Robertson, M.L., 2002. An ecomorphological model of the initial hominid dispersal from Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 43, 773–785.

Anton, S.C., Swisher, C.C., 2004. Early dispersals of Homo from Africa. Annual review of Anthropology 33, 271–296.

Asfaw, B., Beyene, Y., Suwa, G., Walter, R.C., White, T.D., WoldeGabriel, G., Yemane, T., 1992. The earliest Acheulean from Konso-Gardula. Nature 360, 732–735.

Asfaw, B., Gilbert, W.H., Beyene, Y., Hart, W.K., Renne, P.R., Wolde-Gabriel, G., Vrba, E.S., White, T.D. 2002. Remains of Homo erectus from Bouri, Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 416, 317–320.

Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A., 2001. From Africa to Eurasia – early dispersals. Quaternary International 75, 19–28.

Bates, M.R., Bates, C.R., Briant, R.M., 2007. Bridging the gap: a terrestrial view of shallow marine sequences and the importance of the transition zone. Journal of Archaeological Science 34, 1537–1551.

Berthelet, A., 2001. L’outillage lithique du site de dépeçage à Elephas recki ileretensis de Barogali (république de Djibouti). Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences Series IIA Earth and Planetary Science 332, 411–416.

Berthelet, A., 2002. Barogali et l’Oued Doure. Deux gisements représentatifs du Paléolithique ancient en Republique de Djibouti. L’Anthropologie 106, 1–39.

Berthelet, A., Boisaubert, J.-L., Chavaillon, J., 1992. Le Paléolithique en république de Djibouti: nouvelles recherches. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 89, 238–246.

Berthelet, A., Chavaillon, J., 2001. The Early Palaeolithic butchery site of Barogali (Republic of Djibouti). In: Cavaretta, G., Gioia, P., Mussi, M., Palombo, M.R. (Eds.), The World of Elephants . International Congress Proceedings, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome, pp. 176–179.

Beydoun, Z.R., 1970. Southern Arabia and northern Somalia: comparative geology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London A, 267, 267–292.

Beyin, A., 2006. The Bab al Mandab vs. the Nile–Levant: an appraisal of the two dispersal routes for early modern humans Out of Africa. African Archaeological Review 23, 5–30.

Bulgarelli, G.M., 1986. Archaeological activities in the Arab Republic, 1986: Paleolithic culture. East and West 36, 419–422.

Caton-Thompson, G., 1953. Some Palaeoliths from South Arabia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 19, 189–218.

Caton-Thompson, G., 1957. The evidence of South Arabian Palaeoliths in question of Pleistocene land connection with Africa. In: Clark, J.D., Cole, S. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd Pan-African Congress on Prehistory, Livingstone 1955. Chatto and Windus, London, pp. 380–384.

Caton-Thompson, G., Gardner, E.W., 1939. Climate, irrigation, and Early Man in the Hadhramaut. Geographical Journal 93, 18–38.

Chapman, R.W., 1978. General Information on the Arabian Peninsula. In: Al-Sayari, S.S. Zötl, J.G. (Eds.), Quaternary Period in Saudi Arabia, Vol. I. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 4–18.

Chapter Google Scholar

Chauhan, P.R., 2007. Soanian cores and core tools from Toka, northern India: towards a new typo-technological organization. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 26, 412–441.

Chavaillon, J., 1987. Cinquante ans de préhistoire en République de Djibouti. Arqueologia 15, 64–67.

Chaivaillon, J., Berthelet, A., 2001. The Elephas recki site of HaÁdalo (Republic of Djibouti). In: Cavaretta, G., Gioia, P., Mussi, M., Palombo, M.R. (Eds.), The World of Elephants. International Congress Proceedings, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome, pp. 191–193.

Clark, J.D., 1994. The Acheulian industrial complex in Africa and Elsewhere. In: Corruccini, R.S., Ciochon, R.L. (Eds.), Integrative Paths to the Past. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, pp. 451–469.

Clark, J.D., de Heinzelin, J., Schick, K., Hart, W.K., White, T.D., WoldeGabriel, G., Walter, R.C., Suwa, G., Asfaw, B., Vrba, E. Haile-Selassie, Y., 1994. African Homo erectus: old radiometric dates and young Oldowan assemblages in the Middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia. Science 264, 1907–1909.

Coleman, R.G., 1974. Geological background of the Red Sea. In: Whitmarsh, R.B., Weser, O.E., Ross, D.A. (Eds.), Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Volume 23. US Government Printing Office, Washington, pp. 813–819.

Courtillot, V., Achache, J., Landre, F., Bonhommet, N., Montigny R.G., Ferraud, G., 1984. Episodic spreading and rift propagation: new palaeomagnetic and geochronologic data from the Afar nascent passive margin. Journal of Geophysical Research 89, 3315–3333.

de Bonis, L., Geraads, D., Guerin, G., Haga, A., Jaeger, J.-J., Sen, S., 1984. Découverte d’un Hominidé fossile dans le Pléistocène de la République de Djibouti. Comptes Rendus de l’Academie de Sciences Paris 299 : 1097–1100.

de Bonis, L., Geraads, D., Jaeger, J.-J., Sen, S., 1988. Vertébrés du Pléistocène de Djibouti. Bulletin de la Société Geologique Française 4, 323–334.

de Lumley, H., Nioradzé, M., Barsky, D., Cauche, D., Celiberti, V., Nioradzé, G., Notter, O., Zhvania, D., Lordkipanidze, D., 2005. Les industries lithiques préoldowayennes du début du Pléistocène inférieur du site de Dmanissi en Géorgie. L’anthropologie 109, 1–182.

De Maigret, A., 1983. ISMEO activities: Arab Republic of Yemen. East and West 33, 342–343.

Delagnes, A., Lenoble A., Harmand, S., Brugal, J.-P., Prat, S., Tiercelin, J.-J., Roche, H., 2006. Interpreting pachyderm single carcass sites in the African Lower and Early Middle Pleistocene record: A multidisciplinary approach to the site of Nadung’a 4 (Kenya). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25, 448–465.

deMenocal, P.B., 2004. African climate change and faunal evolution during the Plio-Pleistocene. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 220, 3–24.

Dennell, R.W., 2003. Dispersal and colonisation, long and short chronologies: how continuous is the Early Pleistocene record for hominids outside East Africa? Journal of Human Evolution 45, 421–440.

Dennell, R.W., 2004. Hominin dispersals and Asian biogeography during the Lower and Early Middle Pleistocene, c. 2.0 – 0.5 Mya. Asian Perspectives 43, 205–226.

Dennell R.W., Roebroeks, W., 2005. An Asian perspective on early human dispersal from Africa. Nature 438, 1099–1104.

Dennell, R.W., Rendell, H., Hailwood, E., 1988. Early tool-making in Asia: two-million-year-old artefacts in Pakistan. Antiquity 62, 98–106.

Derricourt, R., 2006. Getting “Out of Africa”: sea crossings, land crossings and culture in the hominin migrations. Journal of World Prehistory 19, 119–132.

Doe, B., 1971. Southern Arabia. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York.

Edgell, H.S., 2006. Arabian Deserts- Nature, Origin and Evolution. Springer, New York.

Book Google Scholar

Faure, M., Guérin, C., 1997. Gafolo: nouveau site à Palaeoloxodon recki et Hippopotamus ambhibius (République de Djibouti). Comptes Rendus Academie des sciences Paris 324–II2, 1017–1030

Feakins, S.J., deMenocal, P.B., Elington, T.I., 2005. Biomarker records of late Neogene changes in northeast African vegetation. Geology 33, 977–980.

Field, J.S., Mirazon-Lahr, M., 2005. Assessment of the southern dispersal: GIS-based analyses of potential routes at oxygen isotopic stage 4. Journal of World Prehistory 19, 1–45.

Gabunia, L., Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Swisher, C.C., Ferring, R., Justus, A., Nioradze, M., Tvalchrelidze, M., Anton, S.C., Bosinski, G., Joris, O, de Lumley, M-A., Majsuradze, G., Mouskhelishvili, A., 2000. Earliest Pleistocene cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science 288, 1019–1025.

Goodenough, W., Caton-Thompson, G., Sclater, W.L., Lees, G.M., J.V. Harrison, A., 1939. Climate, irrigation, and early man in the Hadhramaut: discussion. The Geographical Journal 93, 36–38.

Hughes, G.W., Beydoun, Z.R., 1992. The Red Sea-Gulf of Aden: biostratigraphy, lithostratigraphy and palaeoenvironments. Journal of Petroleum Geology 15, 135–156.

Hurcombe, L., 2004. The stone artefacts from the Pabbi Hills. In: Dennell, R.W. (Ed.), Early Hominin Landscapes in Northern Pakistan: Investigations in the Pabbi Hills. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1265, Oxford, pp. 222–292.

Isaac, G. (Ed.). 1997. Koobi Fora Research Project, Volume 5: Plio- Pleistocene archaeology. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Kibunjia, M., Roche, H., Brown, F.H., Leakey, R.E., 1992. Pliocene and Pleistocene archaeological sites west of Lake Turkana, Kenya. Journal of Human Evolution 23, 431–438.

Langbroek, M., 2004. ‘Out of Africa’: An investigation into the Earliest Occupation of the Old World. Archaeological Reports International Ser 1244, Oxford.

Larick, R., Ciochon, R.L., 1996. The African emergence and early Asian dispersals of the genus Homo. American Scientist 84, 538–551.

Leakey, M., 1971. Olduvai Gorge, Volume 3: Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960–1963. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martínez-Navarro, B., 2004. Hippos, pigs, bovids, sabertoothed tigers, monkeys and hominids: dispersals during Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene times through the Levantine Corridor. In: Goren- Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 37–51.

Martínez-Navarro, B., Rook, L., Segid, A., Yosif, D., Ferretti, M.P., Shoshani, J., Tecle, T.M., Libsekal, Y., 2004. The large mammals from Buia (Eritrea): systematics, biochronology, and palaeoenvironments. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigafia 110, 61–88.

Mithen, S., Reed, M., 2002 Stepping out: a computer simulation of hominid dispersal from Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 43, 433–462.

O’Regan, H.J., Bishop, L.C., Elton, S., Lamb, A., Turner, A., 2006. Afro-Eurasian mammalian dispersal routes of the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene and their bearings on earliest hominin movements. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 256, 305–314.

Petraglia, M.D., 2003. The Lower Paleolithic of the Arabian Peninsula: occupations, adaptations, and dispersals. Journal of World Prehistory 17, 141–179.

Petraglia, M.D., 2005. Hominin responses to Pleistocene environmental change in Arabia and South Asia. In: Head, M.J., Gibbard, P.L. (Eds.), Early–Middle Pleistocene Transitions: The Land–Ocean Evidence. Geological Society Special Publications 247, London, pp. 305–319.

Petraglia, M.D., Alsharekh, A., 2004. The Middle Palaeolithic of Arabia: implications for modern human origins, behavior, and dispersals. Antiquity 78, 671–684.

Plummer, T., 2004. Flaked stones and old bones: biological and cultural evolution at the dawn of technology. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 47, 118–164.

Roche H., Brugal J.-P., Delagnes A., Feibel C., Harmand S., Kibunjia M., Prat S., Texier, P.J., 2003. Les sites archéologiques plio-pléistocènes de la Formation de Nachukui (Ouest Turkana, Kenya): bilan préliminaire 1996–2000. Comptes Rendus Palévol 2, 663–673.

Rose, J., 2004. The question of Upper Pleistocene connections between East Africa and South Arabia. Current Anthropology 45, 551–555.

Sahnouni, M. Derradji, A., 2007. The Lower Palaeolithic of the Maghreb: current state of knowledge. Adumatu 15, 7–44.

Schick, K., Toth, N., 2006. An Overview of the Oldowan industrial complex: the sites and the nature of their evidence. In: Toth, N., Schick, K. (Eds.), The Oldowan: Case Studies into the Earliest Stone Age. Gosport, Stone Age Institute Press, pp. 3–42.

Semaw, S., Renne, P., Harris, J.W.K., Feibel, C.S., Bernor, R.L., Fesseha, N., Mowbray, K., 1997. 2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia. Nature 385, 333–336.

Swisher, C. III, Curtis, G.H., Jacob, T., Getty, A.G., Suprijo, A., Widiasmoro, 1994. Age of the earliest known hominids in Java, Indonesia. Science 263, 1118–1121.

Tattersall, I., Clark, J.M., Whybrow, P., 1995. Paleontological Reconnaissance in Yemen. Yemen Update 37, 21–24.

Thomas, H., Geraads, D., Janjou, D., Vaslet, D., Memseh, A., Billiou, D., Bocherens, H., Dobigny, G., Eisenmann, V., Gayet, M., de Lapparent de Broin, F., Petter, G, Halawani, M. 1998. First Pleistocene faunas from the Arabian peninsula: An Nafud desert, Saudi Arabia. Comptes Rendus Academie des Sciences 326, 145–152.

Todd, N.E., 2005. Reanalysis of African Elephas recki: implications for time, space, and taxonomy. Quaternary International 126–128, 65–72.

Turner, A., 1999. Assessing earliest human settlement of Eurasia: Late Pliocene dispersions from Africa. Antiquity 73, 563–570.

Turner, A., O’Regan, H., 2007. Zoogeography: primate and early hominin distribution and migration patterns. In: Henke, W. Tattersall, I. (Eds.), Handbook of Paleoanthropology: Principles, Methods, and Approaches. Springer, New York, pp. 421–440.

Van Beek, G., Cole, G., Jamme, W.F., 1964. An archaeological reconnaissance in Hadhramaut, South Arabia – a preliminary report. Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, The Smithsonian Report for 1963, Publication 4587: 521–555.

Vrba, E., 2007. Role of Environmental Stimuli in Hominid Origins. In: Henke, W. Tattersall, I. (Eds.), Handbook of Paleoanthropology: Principles, Methods, and Approaches. Springer, New York, pp. 1441–1482.

Werner, N.Y., Mokady. O., 2004. Swimming out of Africa: mitochondrial DNA evidence for late Pliocene dispersal of a cichlid from Central Africa to the Levant. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 82, 103–109.

Whalen, N. M., Pease, D.W., 1990. Variability in Developed Oldowan and Acheulean bifaces of Saudi Arabia. Atlal 13, 43–48.

Whalen, N. M., Pease, D.W., 1992. Archaeological survey in Southwest Yemen, 1990. Paléorient 17, 129–133.

Whalen, N., Davis, W. Pease, D., 1989. Early Pleistocene migrations into Saudi Arabia. Atlal 12, 59–75.

Whalen, N. M., Schatte, K.E., 1997. Pleistocene sites in southern Yemen. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 8, 1–10.

Whalen, N. M., Sindi, H., Wahida, G., Siraj-ali, J. S. 1983. 1—Excavation of Acheulean sites near Saffaqah in ad-Daw dmi 1402–1982. Atlal 7, 9–21.

Whitmarsh, R.B., Weser, O.E., Ross, D.A. et al. (Eds.), 1974. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, Volume 23. Washington, US Government Printing Office, pp. 5–1180.

Whybrow, P. J., Hill, A., (Eds.). 1999. Fossil Vertebrates of Arabia. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

WoldeGabriel, G., Heiken, G., White, T.D., Asfaw, B., Hart, W.K. Renne, P.R., 2000. Volcanism, tectonism, sedimentation, and the paleoanthropological record in the Ethiopian Rift System. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 345, 83–99.

Zhu, R., An Z., Potts, R., Hoffman, K.A., 2003. Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans in China. Earth Science Reviews 61, 341–359.

Zimmerman, P., 2000. Middle Hadramawt Archaeological Survey- Preliminary results, October 1999 season. Yemen Update 42, 27–29.

Zumbo, V., Feraud, G., Vellutini, P., Piguet, P., Vincent, J., 1995. First 40 Ar/ 39 Ar dating on Early Pliocene to Plio-Pleistocene magmatic events of the Afar – Republic of Djibouti. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 65, 281–295.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stone Age Institute, Bloomington, 47407-5097, USA

Parth R. Chauhan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem, 91905, Israel

Erella Hovers

Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, 7701, Rondebosch, South Africa

David R. Braun

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Chauhan, P.R. (2009). Early Homo Occupation Near the Gate of Tears : Examining the Paleoanthropological Records of Djibouti and Yemen. In: Hovers, E., Braun, D.R. (eds) Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Oldowan. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9060-8_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9060-8_5

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-1-4020-9059-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-4020-9060-8

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Sign in

- My Account

- Basket

Items related to Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene...

Koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology - hardcover.

- About this title

- About this edition