Rosie Psychology: Your online tutor

How to demonstrate critical evaluation in your psychology assignments

Thinking critically about psychology research

Critical thinking is often taught in undergraduate psychology degrees, and is a key marking criteria for higher marks in many assignments. But getting your head around how to write critically can sometimes be difficult. It can take practice. The aim of this short blog is to provide an introduction to critical evaluation, and how to start including evidence of critical evaluation in your psychology assignments.

So what does “critical evaluation” really mean?

Broadly speaking, critical evaluation is the process of thinking and writing critically about the quality of the sources of evidence used to support or refute an argument. By “ evidence “, I mean the literature you cite (e.g., a journal article or book chapter). By “ quality of the evidence “, I mean thinking about whether this topic has been tested is in a robust way. If the quality of the sources is poor, then this could suggest poor support for your argument, and vice versa. Even if the quality is poor, this is important to discuss in your assignments as evidence of critical thinking in this way!

In the rest of this blog, I outline a few different ways you can start to implement critical thinking into your work and reading of psychology. I talk about the quality of the evidence, a few pointers for critiquing the methods, theoretical and practical critical evaluation too. This is not an exhaustive list, but hopefully it’ll help you to start getting those higher-level marks in psychology. I also include an example write-up at the end to illustrate how to write all of this up!

The quality of the evidence

There are different types of study designs in psychology research, but some are of higher quality than others. The higher the quality of the evidence, the stronger the support for your argument the research offers, because the idea has been tested more rigorously. The pyramid image below can really help to explain what we mean by “quality of evidence”, by showing different study designs in the order of their quality.

Not every area of psychology is going to be full of high quality studies, and even the strongest sources of evidence (i.e., systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses) can have limitations! Because no study is perfect, it can be a good habit to tell the reader, in your report, (i) what the design of the study is that you’re citing, AND, (ii) how this affects your argument. Doing so would be evidence of critical thought. (See an example write-up below for implementing this, but do not copy and paste it!)

But first, what do I mean by “design”? The design of the study refers to how the study was carried out. There are sometimes broad categories of design that you’ll have heard of, like a ‘survey design’, ‘a review paper’, or an ‘experimental design’. Within these categories, though, there can be more specific types of design (e.g. a cross-sectional survey design, or a longitudinal survey design; a randomised controlled experiment or a simple pre-post experiment). Knowing these specific types of design is a good place to start when thinking about how to critique the evidence when citing your sources, and the image below can help with that.

Image source: https://thelogicofscience.com/2016/01/12/the-hierarchy-of-evidence-is-the-studys-design-robust/

In summary, there are various types of designs in psychology research. To name a few from the image above, we have: a meta-analysis or a systematic review (a review paper that summarises the research that explores the same research question); a cross-sectional survey study (a questionnaire that people complete once – these are really common in psychology!). If you’re not familiar with these, I would highly suggest doing a bit of reading around these methods and some of their general limitations – you can then use these limitation points in your assignments! To help with this, you could do a Google Scholar search for ‘limitations of a cross-sectional study’, or ‘why are randomised control trials gold standard?’. You can use any published papers as further support as a limitation.

Methodological critical evaluation

- Internal validity: Are the findings or the measures used in the study reliable (e.g., have they been replicated by another study, and is the reliability high)?

- External validity: Are there any biases in the study that might affect generalisability(e.g., gender bias, where one gender may be overrepresented for the population in the sample recruited)? Lack of generalisability is a common limitation that undergraduates tend to use by default as a limitation in their reports. It’s a perfectly valid limitation, but it can usually be made much more impactful by explaining exactly how it’s a problem for the topic of study. In some cases, this limitation may not be all that warranted; for example, a female bias may be expected in a sample of psychology students, because undergraduate courses tend to be filled mostly with females!

- What is the design of the study, and how it a good or bad quality design (randomised control trial, cross-sectional study)?

Theoretical critical evaluation

- Do the findings in the literature support the relevant psychological theories?

- Have the findings been replicated in another study? (If so, say so and add a reference!)

Practical critical evaluation

- In the real world, how easy would it be to implement these findings?

- Have these findings been implemented? (If so, you could find out if this has been done well!)

Summary points

In summary, there are various types of designs in psychology research. To name a few from the image above, we have: a meta-analysis or a systematic review (a review paper that summarises the research that explores the same research question); a cross-sectional survey study (a questionnaire that people complete once – these are really common in psychology!). If you’re not familiar with these, I would highly suggest doing a bit of reading around these methods and some of their general limitations – you can then use these limitation points in your assignments! To help with this, I would do a Google Scholar search for ‘limitations of a cross-sectional study’, or ‘why are randomised control trials gold standard?’. You can use these papers as further support as a limitation.

You don’t have to use all of these points in your writing, these are just examples of how you can demonstrate critical thinking in your work. Try to use at least a couple in any assignment. Here is an example of how to write these up:

An example write-up

“Depression and anxiety are generally associated with each other (see the meta-analysis by [reference here]). For example, one of these studies was a cross-sectional study [reference here] with 500 undergraduate psychology students. The researchers found that depression and anxiety (measured using the DASS-21 measure) were correlated at r = .76, indicating a strong effect. However, this one study is limited in that it used a cross-sectional design, which do not tell us whether depression causes anxiety or whether anxiety causes depression; it just tells us that they are correlated. It’s also limited in that the participants are not a clinical sample, which does not tell us about whether these are clinically co-morbid constructs. Finally, a strength of this study is that it used the DASS-21 which is generally found to be a reliable measure. Future studies would therefore benefit from using a longitudinal design to gain an idea as to how these variables are causally related to one another, and use more clinical samples to understand the implications for clinical practice. Overall, however, the research generally suggests that depression and anxiety are associated. That there is a meta-analysis on this topic [reference here], showing that there is lots of evidence, suggests that this finding is generally well-accepted.”

- Notice how I first found a review paper on the topic to broadly tell the reader how much evidence there is in the first place. I set the scene of the paragraph with the first sentence, and then the last sentence I brought it back, rounding the paragraph off.

- Notice how I then described one study from this paper in more detail. Specifically, I mentioned the participants, the design of the study and the measure the researchers used to assess these variables. Critically, I then described how each of these pieces of the method are disadvantages/strengths of the study. Sometimes, it’s enough to just say “the study was limited in that it was a cross-sectional study”, but it can really show that you are thinking critically, if you also add “… because it does not tell us….”.

- Notice how I added a statistic there to further illustrate my point (in this case, it was the correlation coefficient), showing that I didn’t just read the abstract of the paper. Doing this for the effect sizes in a study can also help demonstrate to a reader that you understand statistics (a higher-level marking criteria).

Are these points you can include in your own work?

Thanks for reading,

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

Understanding and Evaluating Research: A Critical Guide

- By: Sue L. T. McGregor

- Publisher: SAGE Publications, Inc

- Publication year: 2018

- Online pub date: December 20, 2019

- Discipline: Sociology , Education , Psychology , Health , Anthropology , Social Policy and Public Policy , Social Work , Political Science and International Relations , Geography

- Methods: Theory , Research questions , Mixed methods

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781071802656

- Keywords: discipline , emotion , Johnson & Johnson , journals , knowledge , law , peer review Show all Show less

- Print ISBN: 9781506350950

- Online ISBN: 9781071802656

- Buy the book icon link

Subject index

Understanding and Evaluating Research: A Critical Guide shows students how to be critical consumers of research and to appreciate the power of methodology as it shapes the research question, the use of theory in the study, the methods used, and how the outcomes are reported. The book starts with what it means to be a critical and uncritical reader of research, followed by a detailed chapter on methodology, and then proceeds to a discussion of each component of a research article as it is informed by the methodology. The book encourages readers to select an article from their discipline, learning along the way how to assess each component of the article and come to a judgment of its rigor or quality as a scholarly report.

Front Matter

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 1: Critical Research Literacy

- PHILOSOPHICAL AND THEORETICAL ASPECTS OF RESEARCH

- Chapter 2: Research Methodologies

- Chapter 3: Conceptual Frameworks, Theories, and Models

- ORIENTING AND SUPPORTIVE ELEMENTS OF RESEARCH

- Chapter 4: Orienting and Supportive Elements of a Journal Article

- Chapter 5: Peer-Reviewed Journals

- RESEARCH JUSTIFICATIONS, AUGMENTATION, AND RATIONALES

- Chapter 6: Introduction and Research Questions

- Chapter 7: Literature Review

- RESEARCH DESIGN AND RESEARCH METHODS

- Chapter 8: Overview of Research Design and Methods

- Chapter 9: Reporting Qualitative Research Methods

- Chapter 10: Reporting Quantitative Methods and Mixed Methods Research

- RESULTS AND FINDINGS

- Chapter 11: Statistical Literacy and Conventions

- Chapter 12: Descriptive and Inferential Statistics

- Chapter 13: Results and Findings

- DISCUSSION, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- Chapter 14: Discussion

- Chapter 15: Conclusions

- Chapter 16: Recommendations

- ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAYS AND THEORETICAL PAPERS

- Chapter 17: Argumentative Essays: Position, Discussion, and Think-Piece Papers

- Chapter 18: Conceptual and Theoretical Papers

Back Matter

Sign in to access this content, get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

- Directories

Writing in Psychology

For most (if not all) your psychology assignments, you'll be required to critically analyse relevant psychological theory and research. If you're just starting out in psychology, you might not know what this involves. This guide will give you an idea of what it means to critically analyse research, along with some practical suggestions for how you can demonstrate your critical-thinking skills.

What is critical analysis, and why is it important?

Critical analysis involves thinking about the merits and drawbacks of what you're reading. It doesn't necessarily mean tearing apart what you've read-it could also involve highlighting what an author or researcher has done well, and thinking through the implications of a study on the broader research area.

Critical analysis is extremely important in evaluating published research: Psychology studies often build on the limitations of others, and it's important to assess the merits of a study before accepting its conclusions. Furthermore, as a student, your critical analysis of the literature is a way of showing your marker that you've engaged with the field.

What makes critical analysis in psychology different, and how do I critically analyse the literature?

In psychology, critical analysis typically involves evaluating both theory and empirical research (i.e., scientific studies). When critically analysing theory , relevant questions include:

- Does the theory make sense (i.e., is it logical)?

- Can the theory explain psychological phenomena (i.e., what we actually observe in terms of people's behaviour), or does it leave some things unexplained?

- Have any studies been conducted to specifically test this theory, and if so, what did they find? Can we believe this study's conclusions?

In terms of evaluating empirical research , relevant questions include:

- Does the study's research question come logically from the literature the authors have reviewed?

- Are there any issues with the participant sample (e.g., not representative of the population being studied)?

- Do the measures (e.g., questionnaires) actually assess the process of interest?

- Have the appropriate statistical analyses been conducted?

- Do the authors make appropriate conclusions based on their findings, or do they go beyond their findings (i.e., overstate their conclusions)?

Before you critically analyse research, it's important to make sure that you understand what is being argued. We have some resources that can help you get the most out of your reading ( R eading strategies ), as well as some note-taking strategies ( N ote-taking ). The Cornell method might be especially useful, since it involves jotting down your own thoughts/opinions as you're reading, rather than simply summarising information.

As you get more practise critically analysing the literature, you'll find that it starts to feel more natural, and becomes something that you engage in automatically. However, as you're starting out, deliberately thinking through some of the questions in the previous section can help add structure to this process.

What does critical analysis look like?

After you've had a think about the merits and drawbacks of a published piece of work, how do you actually show that you've engaged in critical analysis? Below are some examples of sentences where critical analysis has been demonstrated:

- "Although Brown's (1995) theory can account for [abc], it cannot explain [xyz]."

- "This study is a seminal one in the area, given that it was the first to investigate...".

- "In order to clarify the role of [abc], the study could have controlled for...".

- "This study was a significant improvement over earlier efforts to investigate this topic because...".

What these statements have in common is that they are evaluative : They show that you're making a judgment about the theory or empirical study you're discussing. In general, your marker will be able to tell whether you have engaged in critical analysis by seeing if you've made such statements throughout your work.

Critical analysis in psychology: Some common pitfalls

"The sample size of the study was too small."

Your critiques need to have evidence behind them. Making statements such as this is fine, as long as you follow them up with your reasoning (in this case, on what basis have you decided that the study didn't have enough participants?).

" The study didn't look at participants of [this age/this gender/this ethnic group]."

Traditionally, the area of psychology has tended to focus on WEIRD (white, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic) individuals. This is certainly an issue for the generalisability of research findings. However, if you make this type of statement, you can further demonstrate your critical-thinking skills by talking about why you think this is an issue for the particular topic you're researching: For example, how might the results of a study differ if a non-WEIRD participant sample had been recruited instead?

Being too critical.

Chances are that if a study is a highly cited one in your area, it probably has some merits (even if it's just that it drew attention to an important topic). You should always be on the lookout for strengths as well as limitations, be they theoretical (i.e., a cohesive, well-elaborated theory) or experimental (i.e., a clever study design).

Other assessments

Writing a creative piece

Writing a critical review

Writing a policy brief

Writing an abstract

Writing an annotated bibliography

Writing in Law

- ANU Library Academic Skills

- +61 2 6125 2972

Clinical Psychology: Critical Appraisal and Evaluation Skills

- Getting Started

- Finding Books

- Finding Journals

- Finding Articles

- Evidence-based practice

- LinkedIn Learning

- Psychological Testing

- Images and Photographs

- Systematic literature searching

- Clinical trials

- Critical Appraisal and Evaluation Skills

- Useful Websites

- Study and research skills

- Referencing

- Training and Support

- News and Media Resources

- Viewing for your subject

- Decolonising Grey Literaure

- Generative AI

- Scientific Writing Centre

Evaluating your results

Just because material has been published in a journal or appears on a wesbite, this does not mean it is suitable for your purpose. The Open University, in its SAFARI guide to information skills , suggests the following criteria, which you can use for the web and for printed material:

P resentation - is the information presented in a clear and readable way? Are there relevant diagrams and photographs? Is it written objectively or is it emotive?

R elevance - is it relevant and appropriate for your needs? Does it cover the countries or regions which interest you? Does it cover all aspects of your topic?

O bjectivity - is it balanced or is there some bias? Can you easily establish who the authors are and what their authority might be? Are there vested interests behind the website? Is it trying to sell you something?

M ethod - how was the information gathered together? Are the methods clearly stated? Ask yourself basic questions about sample size, use of control groups. questionnaire design etc.

P rovenance or Authority - who or what originated the information and are they reliable sources? Are the authors acknowledged experts in this area? What else have they published on this topic? Do you they belong to well-known institutions? If you're looking at a journal article, is it from a peer-reviewed journal? If it is a website, did you find the link on a trusted site, such as NHS Evidence or a professional body or a university?

T imeliness - is the information up-to-date and can you tell if it has been superseded? Is it clear when the website was produced?

Critical Appraisal

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in an evidence-based context. This is of high relevance for medicine, biomedicine and health care contexts. Here are online courses, websites and checklists to help you appraise the material you have retrieved.

- Health Knowledge: Finding and Appraising the Evidence Online course from HealthKnowledge. Aimed at public health practitioners who are new to evidence based practice and critical appraisal. There are six modules including an overall introduction to critical appraisal, systematic reviews, economic evaluations and making sense of results.

- Critical Appraisal Checklists From SIGN. This is a basic course intended for those who need critical appraisal skills for their job or to further their professional education. You may also find it useful if you have not done critical appraisal for some time and want to revive your skills.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Oxford-based CASP runs workshops and provides a wealth of checklists and training materials on critical appraisal. Useful, downloadable checklists for different study types, such as systematic review or randomised clinical trials.

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Critical Appraisal CEBM based at Oxford University, provides worksheets, checklists and other tools to use for critical appraisal. The CEBM also provides other tools for EBM, such as likelihood ratios and the CATmaker, a computer-assisted critical appraisal tool.

Evaluating grey literature

- AACODS Checklist

Grey literature has not been through any sort of peer review process. Therefore it is particularly important that you evaluate material very carefully to decide whether to use it.

The AACODS checklist is designed to enable evaluation and critical appraisal of grey literature.

A Authority

O Objectivity

S Significance.

It was prepared at Flinders University and there is a very helpful annotated checklist available.

- << Previous: Clinical trials

- Next: Useful Websites >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://lancaster.libguides.com/clinpsy

*Psychology

- How to locate an article

- Encyclopedias and Online References

- Demographics & Statistics

- Tests & Measurements

Understanding the Information Cycle

Scholarly vs popular, evaluating popular and web-based sources, sorting google results, not scholarly.

- Finding Graduate Study

- APA Style 6th Ed.

- APA Style 7th Ed. This link opens in a new window

- Impact Metrics

- Workshops This link opens in a new window

The Information Cycle is the progression of media coverage of a particular newsworthy event. Understanding this cycle will help you know what information is available on your topic and to better evaluate information sources covering that topic at that time.

The Information Cycle from UCF Libraries on Vimeo .

(For a larger view of this chart, right click and open in a new tab).

What is the distinction between popular and scholarly sources? Below is a chart comparing works with a more scholarly focus and those that are less so. Additionally, there are three main types of publications:

- Scholarly sources are intended for academic use with a specialized vocabulary and extensive citations; they are often peer-reviewed. Scholarly sources help answer the "so what?" questions and make connections between variables (or issues).

- Popular sources are intended for the general public and are typically written to entertain, inform or persuade. Popular sources help you answer "who, what, where, and when" questions. Popular sources range from research-oriented to propaganda-focused.

- Trade publications share general news, trends, and opinions in a certain industry; they are not considered scholarly, because, although generally written by experts, they do not focus on advanced research and are not peer-reviewed.

For a detailed chart comparing these three types of publications, visit:

- Publication Types and Bias

Once you have located online sources you are considering using for your research project, it is important to critically evaluate the source for reliability.

One method to evaluate sources is the SIFT Method, developed by Mike Caulfield .

The SIFT Method

The SIFT method is used for critically navigating and assessing digital information. It is designed to evaluate the credibility of information, understand its context, and decide on its reliability. It involves four critical moves: Stop, Investigate the Source, Find Better Coverage, and Trace Claims to the Original Context. This method Adopting SIFT establishes a critical mindset when you pause to consider the source, search for diverse perspectives, and locate the original source of claims, fostering a more informed and critical approach to consuming digital content.

The four critical moves of SIFT:

- Stop: Before engaging with content, pause to consider your familiarity with the source and its credibility. This step encourages mindful information consumption Ask yourself whether you know the website or source of the information, and what the reputation of both the claim and the website is.

- Investigate the Source: Take a moment to understand the source's background. Knowing the author or publisher's expertise and agenda aids in interpreting the content accurately.For example, watching a video promoting milk benefits created by the dairy industry, recognizing the source's vested interest is key to understanding biased reporting. This awareness informs your understanding and critical assessment of the information presented.

- Find Better Coverage: Look for reputable sources that cover the same topic. This helps in understanding different perspectives and the consensus around a claim. Should you start to feel bogged down while verifying facts, pause and reflect on your goal. For intentions like sharing, reading for enjoyment, or grasping basic concepts, confirming the credibility of the source may suffice. However, for in-depth research, it's beneficial to meticulously investigate and confirm each claim made in an article on your own.

- Trace Claims to Original Context: Go back to the original source of the information to see it in its true context, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the material. Online content often lacks the full context, such as potentially misleading captions on seemingly real images. Similarly, health claims might reference research findings ambiguously. To address these issues, it's advised to track back to the original source of any claim, media, or quote to understand its true context and verify the accuracy of the claim you encountered.

Additional Evaluation Techniques

When finding sources online, ask yourself the following questions to determine if they are appropriate to use (SCAAN test):

- Source type: Does this source answer your research question? Is it an appropriate type (scholarly or popular, for instance) for your question? Does this contain the information you need to support your argument?

- Currency: Is this source up-to-date? Do I need a resource that contains historical information?

- Accuracy: Is this source accurate? Does its logic make sense to me? Are there any internal contradictions? Does it link or refer to its sources? Does more current data affect the accuracy of the content?

- Authority: Who created or authored this source? Could the author or creator bring any biases to the information presented? Is the author or creator a reputable or well-respected agent in the subject area?

- Neutrality: Is this source intended to educate, inform, or sell? What is the purpose of this source?

Other Evaluation Acronyms

- CARBS : Currency, Authority, Relevancy, Biased or Factual, Scholarly or Popular

- CARS: Credibility (authority), Accuracy, Reasonableness, Support

- CRAAP: Currency, Relevance (source), Accuracy, Authority, Purpose (neutrality)

- DUPED : Dated, Unambiguous, Purpose, Expertise, Determine (source)

- IMVAIN: Independent, Multiple sources quoted, Verified with evidence, Authoritative, Informed, Named sources

- RADAR : Rationale, Authority, Date, Accuracy, Relevance

Finally, consider your own biases when reviewing your information. If the paper/presentation/article had the opposite position/result, would your opinion of its validity change?

- Determining Reliability

Google can be a powerful research tool that helps you find policy and legislative data, statistics, policy reports, and more. The trick is knowing how to get Google to find the good stuff for you.

Know your domains:

The end of a web address (URL), after the dot, is the domain. For example, www.usc.edu, edu is the domain. You can use domains to filter out your Google results.

Common domains are:

- edu -- educational sites

- org -- non-profit sites

- gov -- government sites

I know that many statistics are available on government sites, so I can have Google search for sites that end in gov.

Google domain filtering:

Add the words "site:.gov" (or org/edu/com/etc.) to the end of your Google search. Use a semicolon to separate domains.

With the advent of Open Access, more research is becoming available to a wider variety of researchers. Unfortunately, unscrupulous publishers are also entering the field. These are often called "predatory publishers". Their goal is to raise money - generally by tricking legitimate researchers into submitting their articles to be published for a nominal fee. However, most of these will accept any article by anyone on any topic and call it "scientific."

Check the journal before submitting: Tricks by predatory publishers:

- Turn around time from 5 days to a month (the peer-review process takes a minimum of several months)

- Spam: emails to republish an old article of yours (plagiarizing yourself), serve on a editorial board (they need legitimate names), guaranteed publishing (legitimate journals reject 50-90 of their submissions), instant publishing (see above)

- Fake impact factor (made up numbers to trick potential authors; there are also fake impact factor sites)

- Fake peer review (see above)

- Fake editorial board (they invite people, but if you email members of the board, they may not even know they are being listed)

- True ISSN and doi (journals can get an ISSN and get their articles a doi, even if they are not a legitimate authority)

Always check the journal website before submitting an article.

- << Previous: Tests & Measurements

- Next: Finding Graduate Study >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 10:10 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/psychology

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Res Metr Anal

The Use of Research Methods in Psychological Research: A Systematised Review

Salomé elizabeth scholtz.

1 Community Psychosocial Research (COMPRES), School of Psychosocial Health, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Werner de Klerk

Leon t. de beer.

2 WorkWell Research Institute, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Research methods play an imperative role in research quality as well as educating young researchers, however, the application thereof is unclear which can be detrimental to the field of psychology. Therefore, this systematised review aimed to determine what research methods are being used, how these methods are being used and for what topics in the field. Our review of 999 articles from five journals over a period of 5 years indicated that psychology research is conducted in 10 topics via predominantly quantitative research methods. Of these 10 topics, social psychology was the most popular. The remainder of the conducted methodology is described. It was also found that articles lacked rigour and transparency in the used methodology which has implications for replicability. In conclusion this article, provides an overview of all reported methodologies used in a sample of psychology journals. It highlights the popularity and application of methods and designs throughout the article sample as well as an unexpected lack of rigour with regard to most aspects of methodology. Possible sample bias should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. It is recommended that future research should utilise the results of this study to determine the possible impact on the field of psychology as a science and to further investigation into the use of research methods. Results should prompt the following future research into: a lack or rigour and its implication on replication, the use of certain methods above others, publication bias and choice of sampling method.

Introduction

Psychology is an ever-growing and popular field (Gough and Lyons, 2016 ; Clay, 2017 ). Due to this growth and the need for science-based research to base health decisions on (Perestelo-Pérez, 2013 ), the use of research methods in the broad field of psychology is an essential point of investigation (Stangor, 2011 ; Aanstoos, 2014 ). Research methods are therefore viewed as important tools used by researchers to collect data (Nieuwenhuis, 2016 ) and include the following: quantitative, qualitative, mixed method and multi method (Maree, 2016 ). Additionally, researchers also employ various types of literature reviews to address research questions (Grant and Booth, 2009 ). According to literature, what research method is used and why a certain research method is used is complex as it depends on various factors that may include paradigm (O'Neil and Koekemoer, 2016 ), research question (Grix, 2002 ), or the skill and exposure of the researcher (Nind et al., 2015 ). How these research methods are employed is also difficult to discern as research methods are often depicted as having fixed boundaries that are continuously crossed in research (Johnson et al., 2001 ; Sandelowski, 2011 ). Examples of this crossing include adding quantitative aspects to qualitative studies (Sandelowski et al., 2009 ), or stating that a study used a mixed-method design without the study having any characteristics of this design (Truscott et al., 2010 ).

The inappropriate use of research methods affects how students and researchers improve and utilise their research skills (Scott Jones and Goldring, 2015 ), how theories are developed (Ngulube, 2013 ), and the credibility of research results (Levitt et al., 2017 ). This, in turn, can be detrimental to the field (Nind et al., 2015 ), journal publication (Ketchen et al., 2008 ; Ezeh et al., 2010 ), and attempts to address public social issues through psychological research (Dweck, 2017 ). This is especially important given the now well-known replication crisis the field is facing (Earp and Trafimow, 2015 ; Hengartner, 2018 ).

Due to this lack of clarity on method use and the potential impact of inept use of research methods, the aim of this study was to explore the use of research methods in the field of psychology through a review of journal publications. Chaichanasakul et al. ( 2011 ) identify reviewing articles as the opportunity to examine the development, growth and progress of a research area and overall quality of a journal. Studies such as Lee et al. ( 1999 ) as well as Bluhm et al. ( 2011 ) review of qualitative methods has attempted to synthesis the use of research methods and indicated the growth of qualitative research in American and European journals. Research has also focused on the use of research methods in specific sub-disciplines of psychology, for example, in the field of Industrial and Organisational psychology Coetzee and Van Zyl ( 2014 ) found that South African publications tend to consist of cross-sectional quantitative research methods with underrepresented longitudinal studies. Qualitative studies were found to make up 21% of the articles published from 1995 to 2015 in a similar study by O'Neil and Koekemoer ( 2016 ). Other methods in health psychology, such as Mixed methods research have also been reportedly growing in popularity (O'Cathain, 2009 ).

A broad overview of the use of research methods in the field of psychology as a whole is however, not available in the literature. Therefore, our research focused on answering what research methods are being used, how these methods are being used and for what topics in practice (i.e., journal publications) in order to provide a general perspective of method used in psychology publication. We synthesised the collected data into the following format: research topic [areas of scientific discourse in a field or the current needs of a population (Bittermann and Fischer, 2018 )], method [data-gathering tools (Nieuwenhuis, 2016 )], sampling [elements chosen from a population to partake in research (Ritchie et al., 2009 )], data collection [techniques and research strategy (Maree, 2016 )], and data analysis [discovering information by examining bodies of data (Ktepi, 2016 )]. A systematised review of recent articles (2013 to 2017) collected from five different journals in the field of psychological research was conducted.

Grant and Booth ( 2009 ) describe systematised reviews as the review of choice for post-graduate studies, which is employed using some elements of a systematic review and seldom more than one or two databases to catalogue studies after a comprehensive literature search. The aspects used in this systematised review that are similar to that of a systematic review were a full search within the chosen database and data produced in tabular form (Grant and Booth, 2009 ).

Sample sizes and timelines vary in systematised reviews (see Lowe and Moore, 2014 ; Pericall and Taylor, 2014 ; Barr-Walker, 2017 ). With no clear parameters identified in the literature (see Grant and Booth, 2009 ), the sample size of this study was determined by the purpose of the sample (Strydom, 2011 ), and time and cost constraints (Maree and Pietersen, 2016 ). Thus, a non-probability purposive sample (Ritchie et al., 2009 ) of the top five psychology journals from 2013 to 2017 was included in this research study. Per Lee ( 2015 ) American Psychological Association (APA) recommends the use of the most up-to-date sources for data collection with consideration of the context of the research study. As this research study focused on the most recent trends in research methods used in the broad field of psychology, the identified time frame was deemed appropriate.

Psychology journals were only included if they formed part of the top five English journals in the miscellaneous psychology domain of the Scimago Journal and Country Rank (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ). The Scimago Journal and Country Rank provides a yearly updated list of publicly accessible journal and country-specific indicators derived from the Scopus® database (Scopus, 2017b ) by means of the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) indicator developed by Scimago from the algorithm Google PageRank™ (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ). Scopus is the largest global database of abstracts and citations from peer-reviewed journals (Scopus, 2017a ). Reasons for the development of the Scimago Journal and Country Rank list was to allow researchers to assess scientific domains, compare country rankings, and compare and analyse journals (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ), which supported the aim of this research study. Additionally, the goals of the journals had to focus on topics in psychology in general with no preference to specific research methods and have full-text access to articles.

The following list of top five journals in 2018 fell within the abovementioned inclusion criteria (1) Australian Journal of Psychology, (2) British Journal of Psychology, (3) Europe's Journal of Psychology, (4) International Journal of Psychology and lastly the (5) Journal of Psychology Applied and Interdisciplinary.

Journals were excluded from this systematised review if no full-text versions of their articles were available, if journals explicitly stated a publication preference for certain research methods, or if the journal only published articles in a specific discipline of psychological research (for example, industrial psychology, clinical psychology etc.).

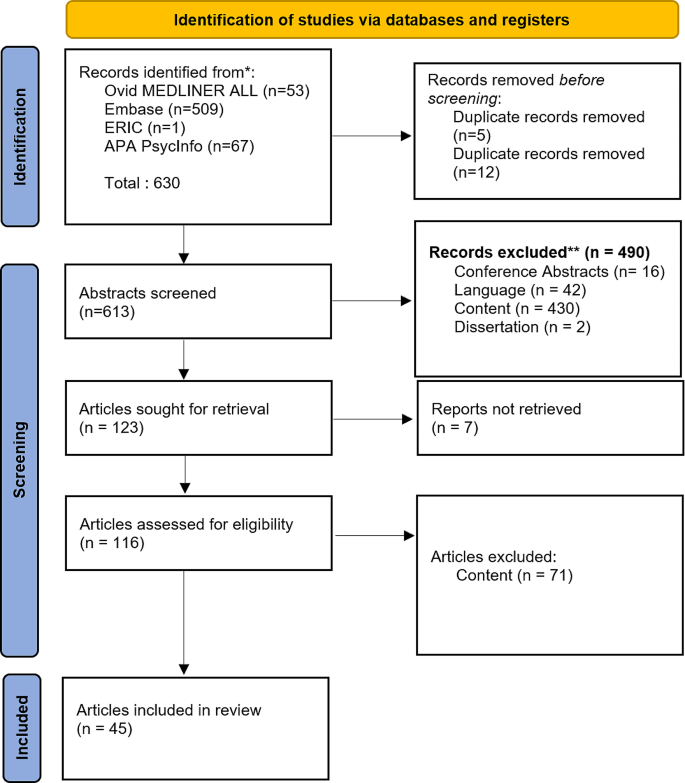

The researchers followed a procedure (see Figure 1 ) adapted from that of Ferreira et al. ( 2016 ) for systematised reviews. Data collection and categorisation commenced on 4 December 2017 and continued until 30 June 2019. All the data was systematically collected and coded manually (Grant and Booth, 2009 ) with an independent person acting as co-coder. Codes of interest included the research topic, method used, the design used, sampling method, and methodology (the method used for data collection and data analysis). These codes were derived from the wording in each article. Themes were created based on the derived codes and checked by the co-coder. Lastly, these themes were catalogued into a table as per the systematised review design.

Systematised review procedure.

According to Johnston et al. ( 2019 ), “literature screening, selection, and data extraction/analyses” (p. 7) are specifically tailored to the aim of a review. Therefore, the steps followed in a systematic review must be reported in a comprehensive and transparent manner. The chosen systematised design adhered to the rigour expected from systematic reviews with regard to full search and data produced in tabular form (Grant and Booth, 2009 ). The rigorous application of the systematic review is, therefore discussed in relation to these two elements.

Firstly, to ensure a comprehensive search, this research study promoted review transparency by following a clear protocol outlined according to each review stage before collecting data (Johnston et al., 2019 ). This protocol was similar to that of Ferreira et al. ( 2016 ) and approved by three research committees/stakeholders and the researchers (Johnston et al., 2019 ). The eligibility criteria for article inclusion was based on the research question and clearly stated, and the process of inclusion was recorded on an electronic spreadsheet to create an evidence trail (Bandara et al., 2015 ; Johnston et al., 2019 ). Microsoft Excel spreadsheets are a popular tool for review studies and can increase the rigour of the review process (Bandara et al., 2015 ). Screening for appropriate articles for inclusion forms an integral part of a systematic review process (Johnston et al., 2019 ). This step was applied to two aspects of this research study: the choice of eligible journals and articles to be included. Suitable journals were selected by the first author and reviewed by the second and third authors. Initially, all articles from the chosen journals were included. Then, by process of elimination, those irrelevant to the research aim, i.e., interview articles or discussions etc., were excluded.

To ensure rigourous data extraction, data was first extracted by one reviewer, and an independent person verified the results for completeness and accuracy (Johnston et al., 2019 ). The research question served as a guide for efficient, organised data extraction (Johnston et al., 2019 ). Data was categorised according to the codes of interest, along with article identifiers for audit trails such as authors, title and aims of articles. The categorised data was based on the aim of the review (Johnston et al., 2019 ) and synthesised in tabular form under methods used, how these methods were used, and for what topics in the field of psychology.

The initial search produced a total of 1,145 articles from the 5 journals identified. Inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in a final sample of 999 articles ( Figure 2 ). Articles were co-coded into 84 codes, from which 10 themes were derived ( Table 1 ).

Journal article frequency.

Codes used to form themes (research topics).

These 10 themes represent the topic section of our research question ( Figure 3 ). All these topics except, for the final one, psychological practice , were found to concur with the research areas in psychology as identified by Weiten ( 2010 ). These research areas were chosen to represent the derived codes as they provided broad definitions that allowed for clear, concise categorisation of the vast amount of data. Article codes were categorised under particular themes/topics if they adhered to the research area definitions created by Weiten ( 2010 ). It is important to note that these areas of research do not refer to specific disciplines in psychology, such as industrial psychology; but to broader fields that may encompass sub-interests of these disciplines.

Topic frequency (international sample).

In the case of developmental psychology , researchers conduct research into human development from childhood to old age. Social psychology includes research on behaviour governed by social drivers. Researchers in the field of educational psychology study how people learn and the best way to teach them. Health psychology aims to determine the effect of psychological factors on physiological health. Physiological psychology , on the other hand, looks at the influence of physiological aspects on behaviour. Experimental psychology is not the only theme that uses experimental research and focuses on the traditional core topics of psychology (for example, sensation). Cognitive psychology studies the higher mental processes. Psychometrics is concerned with measuring capacity or behaviour. Personality research aims to assess and describe consistency in human behaviour (Weiten, 2010 ). The final theme of psychological practice refers to the experiences, techniques, and interventions employed by practitioners, researchers, and academia in the field of psychology.

Articles under these themes were further subdivided into methodologies: method, sampling, design, data collection, and data analysis. The categorisation was based on information stated in the articles and not inferred by the researchers. Data were compiled into two sets of results presented in this article. The first set addresses the aim of this study from the perspective of the topics identified. The second set of results represents a broad overview of the results from the perspective of the methodology employed. The second set of results are discussed in this article, while the first set is presented in table format. The discussion thus provides a broad overview of methods use in psychology (across all themes), while the table format provides readers with in-depth insight into methods used in the individual themes identified. We believe that presenting the data from both perspectives allow readers a broad understanding of the results. Due a large amount of information that made up our results, we followed Cichocka and Jost ( 2014 ) in simplifying our results. Please note that the numbers indicated in the table in terms of methodology differ from the total number of articles. Some articles employed more than one method/sampling technique/design/data collection method/data analysis in their studies.

What follows is the results for what methods are used, how these methods are used, and which topics in psychology they are applied to . Percentages are reported to the second decimal in order to highlight small differences in the occurrence of methodology.

Firstly, with regard to the research methods used, our results show that researchers are more likely to use quantitative research methods (90.22%) compared to all other research methods. Qualitative research was the second most common research method but only made up about 4.79% of the general method usage. Reviews occurred almost as much as qualitative studies (3.91%), as the third most popular method. Mixed-methods research studies (0.98%) occurred across most themes, whereas multi-method research was indicated in only one study and amounted to 0.10% of the methods identified. The specific use of each method in the topics identified is shown in Table 2 and Figure 4 .

Research methods in psychology.

Research method frequency in topics.

Secondly, in the case of how these research methods are employed , our study indicated the following.

Sampling −78.34% of the studies in the collected articles did not specify a sampling method. From the remainder of the studies, 13 types of sampling methods were identified. These sampling methods included broad categorisation of a sample as, for example, a probability or non-probability sample. General samples of convenience were the methods most likely to be applied (10.34%), followed by random sampling (3.51%), snowball sampling (2.73%), and purposive (1.37%) and cluster sampling (1.27%). The remainder of the sampling methods occurred to a more limited extent (0–1.0%). See Table 3 and Figure 5 for sampling methods employed in each topic.

Sampling use in the field of psychology.

Sampling method frequency in topics.

Designs were categorised based on the articles' statement thereof. Therefore, it is important to note that, in the case of quantitative studies, non-experimental designs (25.55%) were often indicated due to a lack of experiments and any other indication of design, which, according to Laher ( 2016 ), is a reasonable categorisation. Non-experimental designs should thus be compared with experimental designs only in the description of data, as it could include the use of correlational/cross-sectional designs, which were not overtly stated by the authors. For the remainder of the research methods, “not stated” (7.12%) was assigned to articles without design types indicated.

From the 36 identified designs the most popular designs were cross-sectional (23.17%) and experimental (25.64%), which concurred with the high number of quantitative studies. Longitudinal studies (3.80%), the third most popular design, was used in both quantitative and qualitative studies. Qualitative designs consisted of ethnography (0.38%), interpretative phenomenological designs/phenomenology (0.28%), as well as narrative designs (0.28%). Studies that employed the review method were mostly categorised as “not stated,” with the most often stated review designs being systematic reviews (0.57%). The few mixed method studies employed exploratory, explanatory (0.09%), and concurrent designs (0.19%), with some studies referring to separate designs for the qualitative and quantitative methods. The one study that identified itself as a multi-method study used a longitudinal design. Please see how these designs were employed in each specific topic in Table 4 , Figure 6 .

Design use in the field of psychology.

Design frequency in topics.

Data collection and analysis —data collection included 30 methods, with the data collection method most often employed being questionnaires (57.84%). The experimental task (16.56%) was the second most preferred collection method, which included established or unique tasks designed by the researchers. Cognitive ability tests (6.84%) were also regularly used along with various forms of interviewing (7.66%). Table 5 and Figure 7 represent data collection use in the various topics. Data analysis consisted of 3,857 occurrences of data analysis categorised into ±188 various data analysis techniques shown in Table 6 and Figures 1 – 7 . Descriptive statistics were the most commonly used (23.49%) along with correlational analysis (17.19%). When using a qualitative method, researchers generally employed thematic analysis (0.52%) or different forms of analysis that led to coding and the creation of themes. Review studies presented few data analysis methods, with most studies categorising their results. Mixed method and multi-method studies followed the analysis methods identified for the qualitative and quantitative studies included.

Data collection in the field of psychology.

Data collection frequency in topics.

Data analysis in the field of psychology.

Results of the topics researched in psychology can be seen in the tables, as previously stated in this article. It is noteworthy that, of the 10 topics, social psychology accounted for 43.54% of the studies, with cognitive psychology the second most popular research topic at 16.92%. The remainder of the topics only occurred in 4.0–7.0% of the articles considered. A list of the included 999 articles is available under the section “View Articles” on the following website: https://methodgarden.xtrapolate.io/ . This website was created by Scholtz et al. ( 2019 ) to visually present a research framework based on this Article's results.

This systematised review categorised full-length articles from five international journals across the span of 5 years to provide insight into the use of research methods in the field of psychology. Results indicated what methods are used how these methods are being used and for what topics (why) in the included sample of articles. The results should be seen as providing insight into method use and by no means a comprehensive representation of the aforementioned aim due to the limited sample. To our knowledge, this is the first research study to address this topic in this manner. Our discussion attempts to promote a productive way forward in terms of the key results for method use in psychology, especially in the field of academia (Holloway, 2008 ).

With regard to the methods used, our data stayed true to literature, finding only common research methods (Grant and Booth, 2009 ; Maree, 2016 ) that varied in the degree to which they were employed. Quantitative research was found to be the most popular method, as indicated by literature (Breen and Darlaston-Jones, 2010 ; Counsell and Harlow, 2017 ) and previous studies in specific areas of psychology (see Coetzee and Van Zyl, 2014 ). Its long history as the first research method (Leech et al., 2007 ) in the field of psychology as well as researchers' current application of mathematical approaches in their studies (Toomela, 2010 ) might contribute to its popularity today. Whatever the case may be, our results show that, despite the growth in qualitative research (Demuth, 2015 ; Smith and McGannon, 2018 ), quantitative research remains the first choice for article publication in these journals. Despite the included journals indicating openness to articles that apply any research methods. This finding may be due to qualitative research still being seen as a new method (Burman and Whelan, 2011 ) or reviewers' standards being higher for qualitative studies (Bluhm et al., 2011 ). Future research is encouraged into the possible biasness in publication of research methods, additionally further investigation with a different sample into the proclaimed growth of qualitative research may also provide different results.

Review studies were found to surpass that of multi-method and mixed method studies. To this effect Grant and Booth ( 2009 ), state that the increased awareness, journal contribution calls as well as its efficiency in procuring research funds all promote the popularity of reviews. The low frequency of mixed method studies contradicts the view in literature that it's the third most utilised research method (Tashakkori and Teddlie's, 2003 ). Its' low occurrence in this sample could be due to opposing views on mixing methods (Gunasekare, 2015 ) or that authors prefer publishing in mixed method journals, when using this method, or its relative novelty (Ivankova et al., 2016 ). Despite its low occurrence, the application of the mixed methods design in articles was methodologically clear in all cases which were not the case for the remainder of research methods.

Additionally, a substantial number of studies used a combination of methodologies that are not mixed or multi-method studies. Perceived fixed boundaries are according to literature often set aside, as confirmed by this result, in order to investigate the aim of a study, which could create a new and helpful way of understanding the world (Gunasekare, 2015 ). According to Toomela ( 2010 ), this is not unheard of and could be considered a form of “structural systemic science,” as in the case of qualitative methodology (observation) applied in quantitative studies (experimental design) for example. Based on this result, further research into this phenomenon as well as its implications for research methods such as multi and mixed methods is recommended.

Discerning how these research methods were applied, presented some difficulty. In the case of sampling, most studies—regardless of method—did mention some form of inclusion and exclusion criteria, but no definite sampling method. This result, along with the fact that samples often consisted of students from the researchers' own academic institutions, can contribute to literature and debates among academics (Peterson and Merunka, 2014 ; Laher, 2016 ). Samples of convenience and students as participants especially raise questions about the generalisability and applicability of results (Peterson and Merunka, 2014 ). This is because attention to sampling is important as inappropriate sampling can debilitate the legitimacy of interpretations (Onwuegbuzie and Collins, 2017 ). Future investigation into the possible implications of this reported popular use of convenience samples for the field of psychology as well as the reason for this use could provide interesting insight, and is encouraged by this study.

Additionally, and this is indicated in Table 6 , articles seldom report the research designs used, which highlights the pressing aspect of the lack of rigour in the included sample. Rigour with regards to the applied empirical method is imperative in promoting psychology as a science (American Psychological Association, 2020 ). Omitting parts of the research process in publication when it could have been used to inform others' research skills should be questioned, and the influence on the process of replicating results should be considered. Publications are often rejected due to a lack of rigour in the applied method and designs (Fonseca, 2013 ; Laher, 2016 ), calling for increased clarity and knowledge of method application. Replication is a critical part of any field of scientific research and requires the “complete articulation” of the study methods used (Drotar, 2010 , p. 804). The lack of thorough description could be explained by the requirements of certain journals to only report on certain aspects of a research process, especially with regard to the applied design (Laher, 20). However, naming aspects such as sampling and designs, is a requirement according to the APA's Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS-Quant) (Appelbaum et al., 2018 ). With very little information on how a study was conducted, authors lose a valuable opportunity to enhance research validity, enrich the knowledge of others, and contribute to the growth of psychology and methodology as a whole. In the case of this research study, it also restricted our results to only reported samples and designs, which indicated a preference for certain designs, such as cross-sectional designs for quantitative studies.

Data collection and analysis were for the most part clearly stated. A key result was the versatile use of questionnaires. Researchers would apply a questionnaire in various ways, for example in questionnaire interviews, online surveys, and written questionnaires across most research methods. This may highlight a trend for future research.

With regard to the topics these methods were employed for, our research study found a new field named “psychological practice.” This result may show the growing consciousness of researchers as part of the research process (Denzin and Lincoln, 2003 ), psychological practice, and knowledge generation. The most popular of these topics was social psychology, which is generously covered in journals and by learning societies, as testaments of the institutional support and richness social psychology has in the field of psychology (Chryssochoou, 2015 ). The APA's perspective on 2018 trends in psychology also identifies an increased amount of psychology focus on how social determinants are influencing people's health (Deangelis, 2017 ).

This study was not without limitations and the following should be taken into account. Firstly, this study used a sample of five specific journals to address the aim of the research study, despite general journal aims (as stated on journal websites), this inclusion signified a bias towards the research methods published in these specific journals only and limited generalisability. A broader sample of journals over a different period of time, or a single journal over a longer period of time might provide different results. A second limitation is the use of Excel spreadsheets and an electronic system to log articles, which was a manual process and therefore left room for error (Bandara et al., 2015 ). To address this potential issue, co-coding was performed to reduce error. Lastly, this article categorised data based on the information presented in the article sample; there was no interpretation of what methodology could have been applied or whether the methods stated adhered to the criteria for the methods used. Thus, a large number of articles that did not clearly indicate a research method or design could influence the results of this review. However, this in itself was also a noteworthy result. Future research could review research methods of a broader sample of journals with an interpretive review tool that increases rigour. Additionally, the authors also encourage the future use of systematised review designs as a way to promote a concise procedure in applying this design.

Our research study presented the use of research methods for published articles in the field of psychology as well as recommendations for future research based on these results. Insight into the complex questions identified in literature, regarding what methods are used how these methods are being used and for what topics (why) was gained. This sample preferred quantitative methods, used convenience sampling and presented a lack of rigorous accounts for the remaining methodologies. All methodologies that were clearly indicated in the sample were tabulated to allow researchers insight into the general use of methods and not only the most frequently used methods. The lack of rigorous account of research methods in articles was represented in-depth for each step in the research process and can be of vital importance to address the current replication crisis within the field of psychology. Recommendations for future research aimed to motivate research into the practical implications of the results for psychology, for example, publication bias and the use of convenience samples.

Ethics Statement

This study was cleared by the North-West University Health Research Ethics Committee: NWU-00115-17-S1.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Aanstoos C. M. (2014). Psychology . Available online at: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/eds/detail/detail?sid=18de6c5c-2b03-4eac-94890145eb01bc70%40sessionmgr4006&vid$=$1&hid$=$4113&bdata$=$JnNpdGU9ZWRzL~WxpdmU%3d#AN$=$93871882&db$=$ers

- American Psychological Association (2020). Science of Psychology . Available online at: https://www.apa.org/action/science/

- Appelbaum M., Cooper H., Kline R. B., Mayo-Wilson E., Nezu A. M., Rao S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: the APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . Am. Psychol. 73 :3. 10.1037/amp0000191 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandara W., Furtmueller E., Gorbacheva E., Miskon S., Beekhuyzen J. (2015). Achieving rigor in literature reviews: insights from qualitative data analysis and tool-support . Commun. Ass. Inform. Syst. 37 , 154–204. 10.17705/1CAIS.03708 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barr-Walker J. (2017). Evidence-based information needs of public health workers: a systematized review . J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 105 , 69–79. 10.5195/JMLA.2017.109 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bittermann A., Fischer A. (2018). How to identify hot topics in psychology using topic modeling . Z. Psychol. 226 , 3–13. 10.1027/2151-2604/a000318 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bluhm D. J., Harman W., Lee T. W., Mitchell T. R. (2011). Qualitative research in management: a decade of progress . J. Manage. Stud. 48 , 1866–1891. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00972.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Breen L. J., Darlaston-Jones D. (2010). Moving beyond the enduring dominance of positivism in psychological research: implications for psychology in Australia . Aust. Psychol. 45 , 67–76. 10.1080/00050060903127481 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burman E., Whelan P. (2011). Problems in / of Qualitative Research . Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaichanasakul A., He Y., Chen H., Allen G. E. K., Khairallah T. S., Ramos K. (2011). Journal of Career Development: a 36-year content analysis (1972–2007) . J. Career. Dev. 38 , 440–455. 10.1177/0894845310380223 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chryssochoou X. (2015). Social Psychology . Inter. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 22 , 532–537. 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24095-6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cichocka A., Jost J. T. (2014). Stripped of illusions? Exploring system justification processes in capitalist and post-Communist societies . Inter. J. Psychol. 49 , 6–29. 10.1002/ijop.12011 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clay R. A. (2017). Psychology is More Popular Than Ever. Monitor on Psychology: Trends Report . Available online at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2017/11/trends-popular

- Coetzee M., Van Zyl L. E. (2014). A review of a decade's scholarly publications (2004–2013) in the South African Journal of Industrial Psychology . SA. J. Psychol . 40 , 1–16. 10.4102/sajip.v40i1.1227 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Counsell A., Harlow L. (2017). Reporting practices and use of quantitative methods in Canadian journal articles in psychology . Can. Psychol. 58 , 140–147. 10.1037/cap0000074 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deangelis T. (2017). Targeting Social Factors That Undermine Health. Monitor on Psychology: Trends Report . Available online at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2017/11/trend-social-factors

- Demuth C. (2015). New directions in qualitative research in psychology . Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 49 , 125–133. 10.1007/s12124-015-9303-9 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. (2003). The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues , 2nd Edn. London: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Drotar D. (2010). A call for replications of research in pediatric psychology and guidance for authors . J. Pediatr. Psychol. 35 , 801–805. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq049 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dweck C. S. (2017). Is psychology headed in the right direction? Yes, no, and maybe . Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12 , 656–659. 10.1177/1745691616687747 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Earp B. D., Trafimow D. (2015). Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology . Front. Psychol. 6 :621. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00621 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ezeh A. C., Izugbara C. O., Kabiru C. W., Fonn S., Kahn K., Manderson L., et al.. (2010). Building capacity for public and population health research in Africa: the consortium for advanced research training in Africa (CARTA) model . Glob. Health Action 3 :5693. 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5693 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferreira A. L. L., Bessa M. M. M., Drezett J., De Abreu L. C. (2016). Quality of life of the woman carrier of endometriosis: systematized review . Reprod. Clim. 31 , 48–54. 10.1016/j.recli.2015.12.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fonseca M. (2013). Most Common Reasons for Journal Rejections . Available online at: http://www.editage.com/insights/most-common-reasons-for-journal-rejections

- Gough B., Lyons A. (2016). The future of qualitative research in psychology: accentuating the positive . Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 50 , 234–243. 10.1007/s12124-015-9320-8 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant M. J., Booth A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Info. Libr. J. 26 , 91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grix J. (2002). Introducing students to the generic terminology of social research . Politics 22 , 175–186. 10.1111/1467-9256.00173 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunasekare U. L. T. P. (2015). Mixed research method as the third research paradigm: a literature review . Int. J. Sci. Res. 4 , 361–368. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2735996 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hengartner M. P. (2018). Raising awareness for the replication crisis in clinical psychology by focusing on inconsistencies in psychotherapy Research: how much can we rely on published findings from efficacy trials? Front. Psychol. 9 :256. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00256 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holloway W. (2008). Doing intellectual disagreement differently . Psychoanal. Cult. Soc. 13 , 385–396. 10.1057/pcs.2008.29 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ivankova N. V., Creswell J. W., Plano Clark V. L. (2016). Foundations and Approaches to mixed methods research , in First Steps in Research , 2nd Edn. K. Maree (Pretoria: Van Schaick Publishers; ), 306–335. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson M., Long T., White A. (2001). Arguments for British pluralism in qualitative health research . J. Adv. Nurs. 33 , 243–249. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01659.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnston A., Kelly S. E., Hsieh S. C., Skidmore B., Wells G. A. (2019). Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: a methodological guide . J. Clin. Epidemiol. 108 , 64–72. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.030 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ketchen D. J., Jr., Boyd B. K., Bergh D. D. (2008). Research methodology in strategic management: past accomplishments and future challenges . Organ. Res. Methods 11 , 643–658. 10.1177/1094428108319843 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ktepi B. (2016). Data Analytics (DA) . Available online at: https://eds-b-ebscohost-com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=24c978f0-6685-4ed8-ad85-fa5bb04669b9%40sessionmgr101&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#AN=113931286&db=ers

- Laher S. (2016). Ostinato rigore: establishing methodological rigour in quantitative research . S. Afr. J. Psychol. 46 , 316–327. 10.1177/0081246316649121 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee C. (2015). The Myth of the Off-Limits Source . Available online at: http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/research/

- Lee T. W., Mitchell T. R., Sablynski C. J. (1999). Qualitative research in organizational and vocational psychology, 1979–1999 . J. Vocat. Behav. 55 , 161–187. 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1707 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leech N. L., Anthony J., Onwuegbuzie A. J. (2007). A typology of mixed methods research designs . Sci. Bus. Media B. V Qual. Quant 43 , 265–275. 10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levitt H. M., Motulsky S. L., Wertz F. J., Morrow S. L., Ponterotto J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: promoting methodological integrity . Qual. Psychol. 4 , 2–22. 10.1037/qup0000082 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowe S. M., Moore S. (2014). Social networks and female reproductive choices in the developing world: a systematized review . Rep. Health 11 :85. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-85 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maree K. (2016). Planning a research proposal , in First Steps in Research , 2nd Edn, ed Maree K. (Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; ), 49–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maree K., Pietersen J. (2016). Sampling , in First Steps in Research, 2nd Edn , ed Maree K. (Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; ), 191–202. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ngulube P. (2013). Blending qualitative and quantitative research methods in library and information science in sub-Saharan Africa . ESARBICA J. 32 , 10–23. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10500/22397 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Nieuwenhuis J. (2016). Qualitative research designs and data-gathering techniques , in First Steps in Research , 2nd Edn, ed Maree K. (Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; ), 71–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nind M., Kilburn D., Wiles R. (2015). Using video and dialogue to generate pedagogic knowledge: teachers, learners and researchers reflecting together on the pedagogy of social research methods . Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 18 , 561–576. 10.1080/13645579.2015.1062628 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Cathain A. (2009). Editorial: mixed methods research in the health sciences—a quiet revolution . J. Mix. Methods 3 , 1–6. 10.1177/1558689808326272 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Neil S., Koekemoer E. (2016). Two decades of qualitative research in psychology, industrial and organisational psychology and human resource management within South Africa: a critical review . SA J. Indust. Psychol. 42 , 1–16. 10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1350 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Onwuegbuzie A. J., Collins K. M. (2017). The role of sampling in mixed methods research enhancing inference quality . Köln Z Soziol. 2 , 133–156. 10.1007/s11577-017-0455-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perestelo-Pérez L. (2013). Standards on how to develop and report systematic reviews in psychology and health . Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 13 , 49–57. 10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70007-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pericall L. M. T., Taylor E. (2014). Family function and its relationship to injury severity and psychiatric outcome in children with acquired brain injury: a systematized review . Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 56 , 19–30. 10.1111/dmcn.12237 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peterson R. A., Merunka D. R. (2014). Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility . J. Bus. Res. 67 , 1035–1041. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie J., Lewis J., Elam G. (2009). Designing and selecting samples , in Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers , 2nd Edn, ed Ritchie J., Lewis J. (London: Sage; ), 1–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandelowski M. (2011). When a cigar is not just a cigar: alternative perspectives on data and data analysis . Res. Nurs. Health 34 , 342–352. 10.1002/nur.20437 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sandelowski M., Voils C. I., Knafl G. (2009). On quantitizing . J. Mix. Methods Res. 3 , 208–222. 10.1177/1558689809334210 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scholtz S. E., De Klerk W., De Beer L. T. (2019). A data generated research framework for conducting research methods in psychological research .

- Scimago Journal & Country Rank (2017). Available online at: http://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=3201&year=2015

- Scopus (2017a). About Scopus . Available online at: https://www.scopus.com/home.uri (accessed February 01, 2017).

- Scopus (2017b). Document Search . Available online at: https://www.scopus.com/home.uri (accessed February 01, 2017).

- Scott Jones J., Goldring J. E. (2015). ‘I' m not a quants person'; key strategies in building competence and confidence in staff who teach quantitative research methods . Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 18 , 479–494. 10.1080/13645579.2015.1062623 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith B., McGannon K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in quantitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology . Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11 , 101–121. 10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stangor C. (2011). Introduction to Psychology . Available online at: http://www.saylor.org/books/

- Strydom H. (2011). Sampling in the quantitative paradigm , in Research at Grass Roots; For the Social Sciences and Human Service Professions , 4th Edn, eds de Vos A. S., Strydom H., Fouché C. B., Delport C. S. L. (Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; ), 221–234. [ Google Scholar ]