10 Famous Examples of Longitudinal Studies

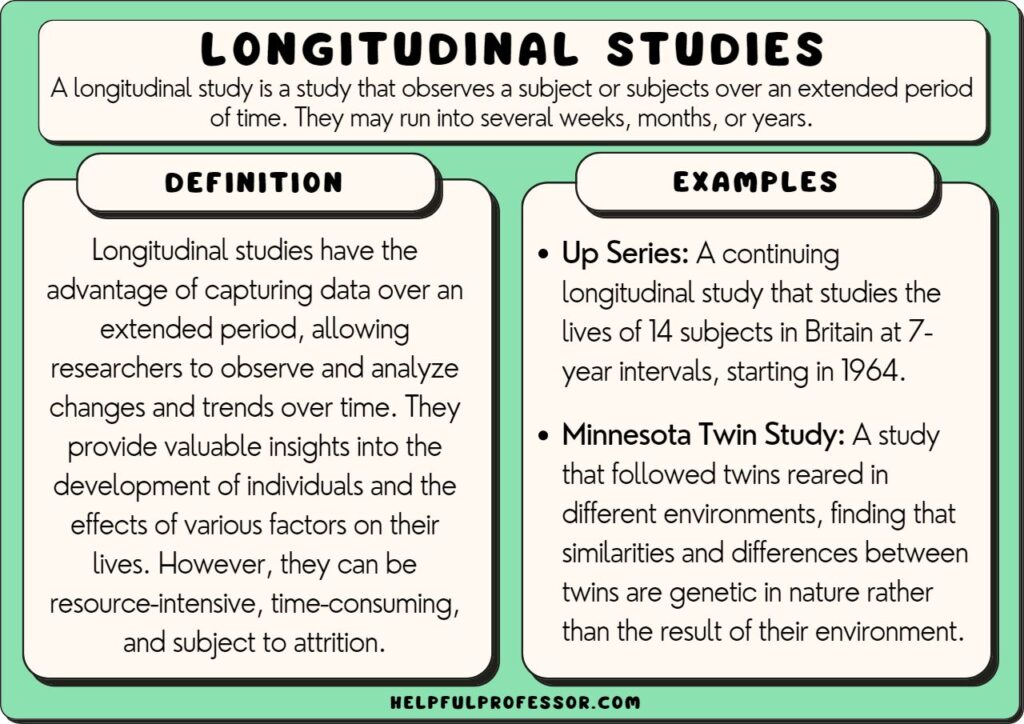

A longitudinal study is a study that observes a subject or subjects over an extended period of time. They may run into several weeks, months, or years. An examples is the Up Series which has been going since 1963.

Longitudinal studies are deployed most commonly in psychology and sociology, where the intention is to observe the changes in the subject over years, across a lifetime, and sometimes, even across generations.

There have been several famous longitudinal studies in history. Some of the most well-known examples are listed below.

Examples of Longitudinal Studies

1. up series.

Duration: 1963 to Now

The Up Series is a continuing longitudinal study that studies the lives of 14 subjects in Britain at 7-year intervals.

The study is conducted in the form of interviews in which the subjects report the changes that have occurred in their lives in the last 7 years since the last interview.

The interviews are filmed and form the subject matter of the critically acclaimed Up series of documentary films directed by Michael Apsted.

When it was first conceived, the aim of the study was to document the life progressions of a cross-section of British children through the second half of the 20th century in light of the rapid social, economic, political, and demographic changes occuring in Britain.

14 children were selected from different socio-economic backgrounds for the first study in 1963 in which all were 7 years old.

The latest installment was filmed in 2019 by which time the participants had reached 63 years of age.

The study noted that life outcomes of subjects were determined to a large extent by their socio-economic and demographic circumstances, and that chances for upward mobility remained limited in late 20th century Britain (Pearson, 2012).

2. Minnesota Twin Study

Duration: 1979 to 1990 (11 years)

Siblings who are twins not only look alike but often display similar behavioral and personality traits.

This raises an oft-asked question: how much of this similarity is genetic and how much of it is the result of the twins growing up together in a similar environment.

The Minnesota twin study was a longitudinal study that set out to find an answer to this question by studying a group of twins from 1979 to 1990 under the supervision of Thomas J Bouchard.

The study found that identical twins who were reared apart in different environments did not display any greater chances of being different from each other than twins that were raised in the same environment.

The study concluded that the similarities and differences between twins are genetic in nature, rather than being the result of their environment (Bouchard et. al., 1990).

3. Grant Study

Duration: 1942 – Present

The Grant Study is one of the most ambitious longitudinal studies. It attempts to answer a philosophical question that has been central to human existence since the beginning of time – what is the secret to living a good life? (Shenk, 2009).

It does so by studying the lives of 268 male Harvard graduates who are interrogated at least every two years with the help of questionnaires, personal interviews, and gleaning information about their physical and mental well-being from their physicians.

Begun in 1942, the study continues to this day.

The study has provided researchers with several interesting insights into what constitutes the human quality of life.

For instance:

- It reveals that the quality of our relationships is more influential than IQ when it comes to our financial success.

- It suggests that our relationships with our parents during childhood have a lasting impact on our mental and physical well-being until late into our lives.

In short, the results gleaned from the study (so far) strongly indicate that the quality of our relationships is one of the biggest factors in determining our quality of life.

4. Terman Life Cycle Study

Duration: 1921 – Present

The Terman Life-Cycle Study, also called the Genetic Studies of Genius, is one of the longest studies ever conducted in the field of psychology.

Commenced in 1921, it continues to this day, over 100 years later!

The objective of the study at its commencement in 1921 was to study the life trajectories of exceptionally gifted children, as measured by standardized intelligence tests.

Lewis Terman, the principal investigator of the study, wanted to dispel the then-prevalent notion that intellectually gifted children tended to be:

- socially inept, and

- physically deficient

To this end, Terman selected 1528 students from public schools in California based on their scores on several standardized intelligence tests such as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence scales, National Intelligence Test, and the Army Alpha Test.

It was discovered that intellectually gifted children had the same social skills and the same level of physical development as other children.

As the study progressed, following the selected children well into adulthood and in their old age, it was further discovered that having higher IQs did not affect outcomes later in life in a significant way (Terman & Oden, 1959).

5. National Food Survey

Duration: 1940 to 2000 (60 years)

The National Food Survey was a British study that ran from 1940 to 2000. It attempted to study food consumption, dietary patterns, and household expenditures on food by British citizens.

Initially commenced to measure the effects of wartime rationing on the health of British citizens in 1940, the survey was extended and expanded after the end of the war to become a comprehensive study of British dietary consumption and expenditure patterns.

After 2000, the survey was replaced by the Expenditure and Food Survey, which lasted till 2008. It was further replaced by the Living Costs and Food Survey post-2008.

6. Millennium Cohort Study

Duration: 2000 to Present

The Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) is a study similar to the Up Series study conducted by the University of London.

Like the Up series, it aims to study the life trajectories of a group of British children relative to the socio-economic and demographic changes occurring in Britain.

However, the subjects of the Millenium Cohort Study are children born in the UK in the year 2000-01.

Also unlike the Up Series, the MCS has a much larger sample size of 18,818 subjects representing a much wider ethnic and socio-economic cross-section of British society.

7. The Study of Mathematically Precocious Youths

Duration: 1971 to Present

The Study of Mathematically Precocious Youths (SMPY) is a longitudinal study initiated in 1971 at the Johns Hopkins University.

At the time of its inception, the study aimed to study children who were exceptionally gifted in mathematics as evidenced from their Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores.

Later the study shifted to Vanderbilt University and was expanded to include children who scored exceptionally high in the verbal section of the SATs as well.

The study has revealed several interesting insights into the life paths, career trajectories, and lifestyle preferences of academically gifted individuals. For instance, it revealed:

- Children with exceptionally high mathematical scores tended to gravitate towards academic, research, or corporate careers in the STEM fields.

- Children with better verbal abilities went into academic, research, or corporate careers in the social sciences and humanities .

8. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging

Duration: 1958 to Present

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) was initiated in 1958 to study the effects of aging, making it the longest-running study on human aging in America.

With a sample size of over 3200 volunteer subjects, the study has revealed crucial information about the process of human aging.

For instance, the study has shown that:

- The most common ailments associated with the elderly such as diabetes, hypertension, and dementia are not an inevitable outcome of growing old, but rather result from genetic and lifestyle factors.

- Aging does not proceed uniformly in humans, and all humans age differently.

9. Nurses’ Health Study

Duration: 1976 to Present

The Nurses’ Health Study began in 1976 to study the effects of oral contraceptives on women’s health.

The first commercially available birth control pill was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1960, and the use of such pills rapidly spread across the US and the UK.

At the same time, a lot of misinformation prevailed about the perceived harmful effects of using oral contraceptives.

The nurses’ health study aimed to study the long-term effects of the use of these pills by researching a sample composed of female nurses.

Nurses were specially chosen for the study because of their medical awareness and hence the ease of data collection that this enabled.

Over time, the study expanded to include not just oral contraceptives but also smoking, exercise, and obesity within the ambit of its research.

As its scope widened, so did the sample size and the resources required for continuing the research.

As a result, the study is now believed to be one of the largest and the most expensive observational health studies in history.

10. The Seattle 500 Study

Duration: 1974 to Present

The Seattle 500 Study is a longitudinal study being conducted by the University of Washington.

It observes a cohort of 500 individuals in the city of Seattle to determine the effects of prenatal habits on human health.

In particular, the study attempts to track patterns of substance abuse and mental health among the subjects and correlate them to the prenatal habits of the parents.

From the examples above, it is clear that longitudinal studies are essential because they provide a unique perspective into certain issues which can not be acquired through any other method .

Especially in research areas that study developmental or life span issues, longitudinal studies become almost inevitable.

A major drawback of longitudinal studies is that because of their extended timespan, the results are likely to be influenced by epochal events.

For instance, in the Genetic Studies of Genius described above, the life prospects of all the subjects would have been impacted by events such as the Great Depression and the Second World War.

The female participants in the study, despite their intellectual precocity, spent their lives as home makers because of the cultural norms of the era. Thus, despite their scale and scope, longitudinal studies do not always succeed in controlling background variables.

Bouchard, T. J. Jr, Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: the Minnesota study of twins reared apart. Science , 250 (4978), 223–228. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2218526

Pearson, A. (2012, May) Seven Up!: A tale of two Englands that, shamefully, still exist The Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/columnists/allison-pearson/9269805/Seven-Up-A-tale-of-two-Englands-that-shamefully-still-exist.html

Shenk, J.W. (2009, June) What makes us happy? The Atlantic https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/06/what-makes-us-happy/307439/

Terman, L. M. & Oden, M. (1959). The Gifted group at mid-Life: Thirty-five years’ follow-up of the superior child . Genetic Studies of Genius Volume V . Stanford University Press.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Parten’s 6 Stages of Play in Childhood, Explained!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Longitudinal Study Design

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A longitudinal study is a type of observational and correlational study that involves monitoring a population over an extended period of time. It allows researchers to track changes and developments in the subjects over time.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

In longitudinal studies, researchers do not manipulate any variables or interfere with the environment. Instead, they simply conduct observations on the same group of subjects over a period of time.

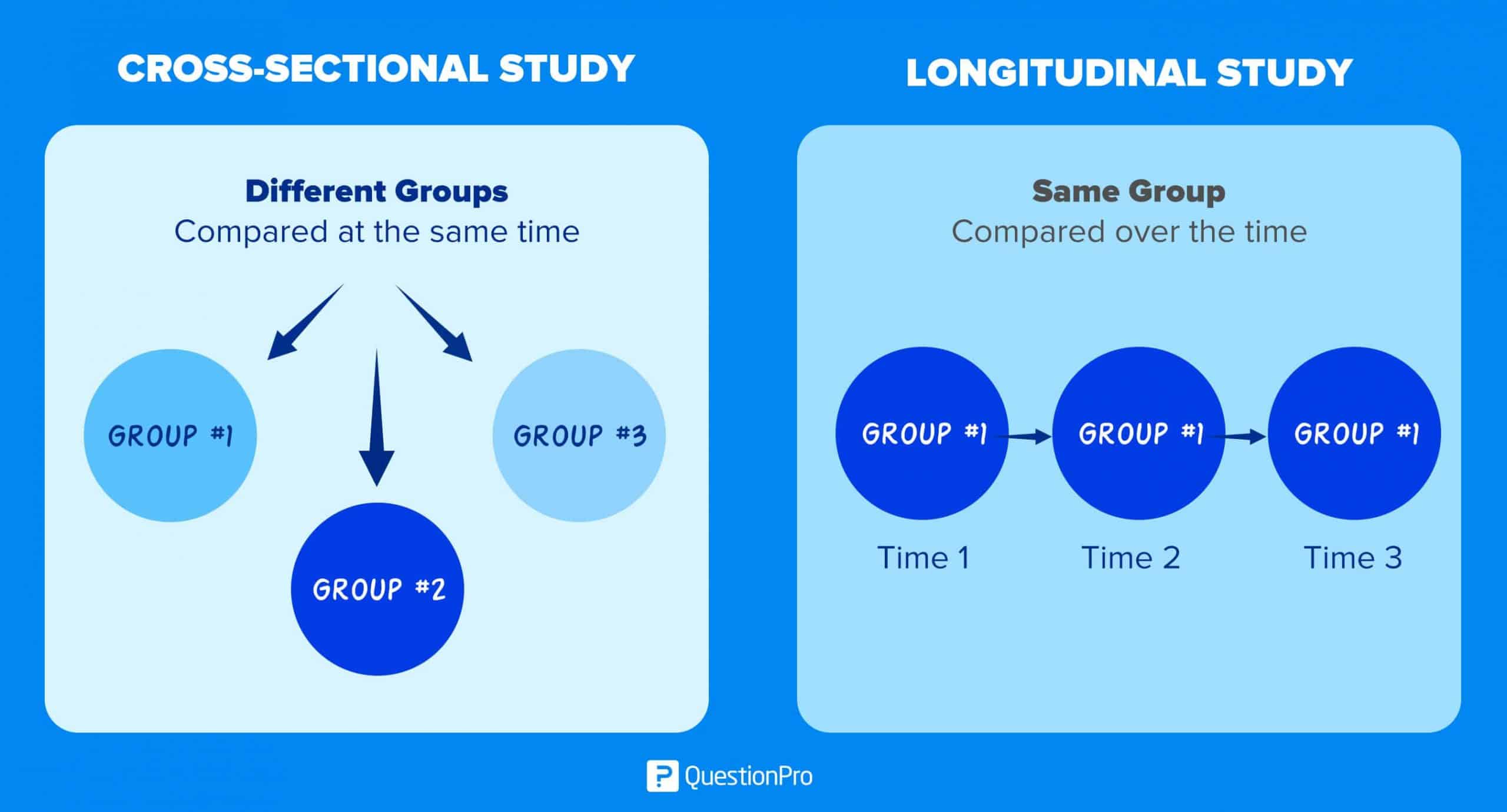

These research studies can last as short as a week or as long as multiple years or even decades. Unlike cross-sectional studies that measure a moment in time, longitudinal studies last beyond a single moment, enabling researchers to discover cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

They are beneficial for recognizing any changes, developments, or patterns in the characteristics of a target population. Longitudinal studies are often used in clinical and developmental psychology to study shifts in behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and trends throughout a lifetime.

For example, a longitudinal study could be used to examine the progress and well-being of children at critical age periods from birth to adulthood.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development is one of the longest longitudinal studies to date. Researchers in this study have followed the same men group for over 80 years, observing psychosocial variables and biological processes for healthy aging and well-being in late life (see Harvard Second Generation Study).

When designing longitudinal studies, researchers must consider issues like sample selection and generalizability, attrition and selectivity bias, effects of repeated exposure to measures, selection of appropriate statistical models, and coverage of the necessary timespan to capture the phenomena of interest.

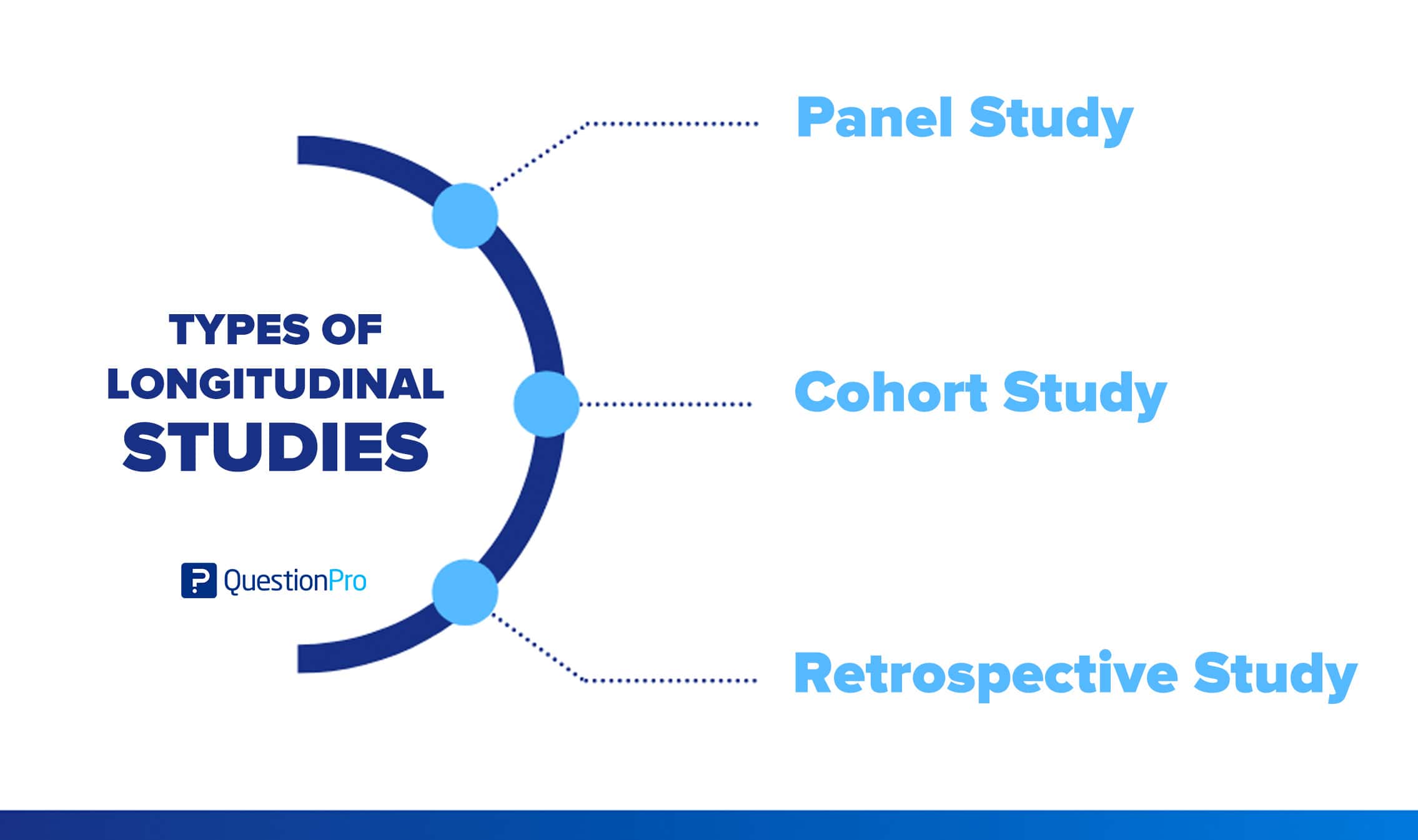

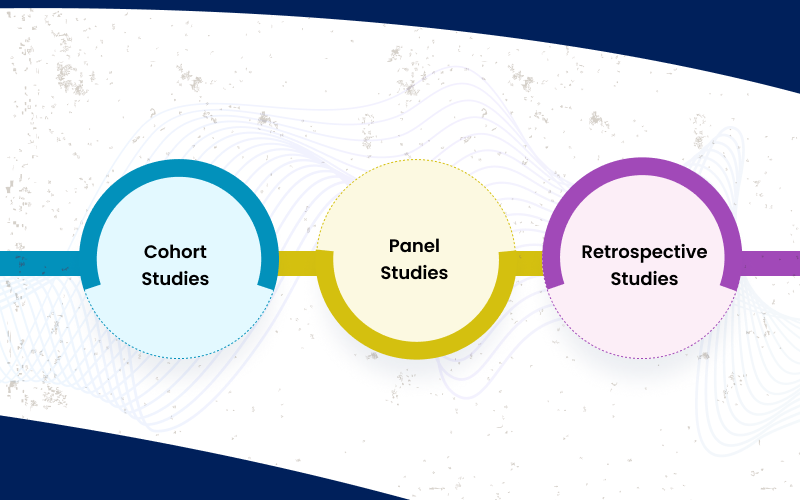

Panel Study

- A panel study is a type of longitudinal study design in which the same set of participants are measured repeatedly over time.

- Data is gathered on the same variables of interest at each time point using consistent methods. This allows studying continuity and changes within individuals over time on the key measured constructs.

- Prominent examples include national panel surveys on topics like health, aging, employment, and economics. Panel studies are a type of prospective study .

Cohort Study

- A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study that samples a group of people sharing a common experience or demographic trait within a defined period, such as year of birth.

- Researchers observe a population based on the shared experience of a specific event, such as birth, geographic location, or historical experience. These studies are typically used among medical researchers.

- Cohorts are identified and selected at a starting point (e.g. birth, starting school, entering a job field) and followed forward in time.

- As they age, data is collected on cohort subgroups to determine their differing trajectories. For example, investigating how health outcomes diverge for groups born in 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

- Cohort studies do not require the same individuals to be assessed over time; they just require representation from the cohort.

Retrospective Study

- In a retrospective study , researchers either collect data on events that have already occurred or use existing data that already exists in databases, medical records, or interviews to gain insights about a population.

- Appropriate when prospectively following participants from the past starting point is infeasible or unethical. For example, studying early origins of diseases emerging later in life.

- Retrospective studies efficiently provide a “snapshot summary” of the past in relation to present status. However, quality concerns with retrospective data make careful interpretation necessary when inferring causality. Memory biases and selective retention influence quality of retrospective data.

Allows researchers to look at changes over time

Because longitudinal studies observe variables over extended periods of time, researchers can use their data to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

High validation

Since objectives and rules for long-term studies are established before data collection, these studies are authentic and have high levels of validity.

Eliminates recall bias

Recall bias occurs when participants do not remember past events accurately or omit details from previous experiences.

Flexibility

The variables in longitudinal studies can change throughout the study. Even if the study was created to study a specific pattern or characteristic, the data collection could show new data points or relationships that are unique and worth investigating further.

Limitations

Costly and time-consuming.

Longitudinal studies can take months or years to complete, rendering them expensive and time-consuming. Because of this, researchers tend to have difficulty recruiting participants, leading to smaller sample sizes.

Large sample size needed

Longitudinal studies tend to be challenging to conduct because large samples are needed for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

Participants tend to drop out

Not only is it a struggle to recruit participants, but subjects also tend to leave or drop out of the study due to various reasons such as illness, relocation, or a lack of motivation to complete the full study.

This tendency is known as selective attrition and can threaten the validity of an experiment. For this reason, researchers using this approach typically recruit many participants, expecting a substantial number to drop out before the end.

Report bias is possible

Longitudinal studies will sometimes rely on surveys and questionnaires, which could result in inaccurate reporting as there is no way to verify the information presented.

- Data were collected for each child at three-time points: at 11 months after adoption, at 4.5 years of age and at 10.5 years of age. The first two sets of results showed that the adoptees were behind the non-institutionalised group however by 10.5 years old there was no difference between the two groups. The Romanian orphans had caught up with the children raised in normal Canadian families.

- The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents (Marques Pais-Ribeiro, & Lopez, 2011)

- The correlation between dieting behavior and the development of bulimia nervosa (Stice et al., 1998)

- The stress of educational bottlenecks negatively impacting students’ wellbeing (Cruwys, Greenaway, & Haslam, 2015)

- The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal (Sidney & Schaufeli, 1995)

- The relationship between loneliness, health, and mortality in adults aged 50 years and over (Luo et al., 2012)

- The influence of parental attachment and parental control on early onset of alcohol consumption in adolescence (Van der Vorst et al., 2006)

- The relationship between religion and health outcomes in medical rehabilitation patients (Fitchett et al., 1999)

Goals of Longitudinal Data and Longitudinal Research

The objectives of longitudinal data collection and research as outlined by Baltes and Nesselroade (1979):

- Identify intraindividual change : Examine changes at the individual level over time, including long-term trends or short-term fluctuations. Requires multiple measurements and individual-level analysis.

- Identify interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Evaluate whether changes vary across individuals and relate that to other variables. Requires repeated measures for multiple individuals plus relevant covariates.

- Analyze interrelationships in change : Study how two or more processes unfold and influence each other over time. Requires longitudinal data on multiple variables and appropriate statistical models.

- Analyze causes of intraindividual change: This objective refers to identifying factors or mechanisms that explain changes within individuals over time. For example, a researcher might want to understand what drives a person’s mood fluctuations over days or weeks. Or what leads to systematic gains or losses in one’s cognitive abilities across the lifespan.

- Analyze causes of interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Identify mechanisms that explain within-person changes and differences in changes across people. Requires repeated data on outcomes and covariates for multiple individuals plus dynamic statistical models.

How to Perform a Longitudinal Study

When beginning to develop your longitudinal study, you must first decide if you want to collect your own data or use data that has already been gathered.

Using already collected data will save you time, but it will be more restricted and limited than collecting it yourself. When collecting your own data, you can choose to conduct either a retrospective or prospective study .

In a retrospective study, you are collecting data on events that have already occurred. You can examine historical information, such as medical records, in order to understand the past. In a prospective study, on the other hand, you are collecting data in real-time. Prospective studies are more common for psychology research.

Once you determine the type of longitudinal study you will conduct, you then must determine how, when, where, and on whom the data will be collected.

A standardized study design is vital for efficiently measuring a population. Once a study design is created, researchers must maintain the same study procedures over time to uphold the validity of the observation.

A schedule should be maintained, complete results should be recorded with each observation, and observer variability should be minimized.

Researchers must observe each subject under the same conditions to compare them. In this type of study design, each subject is the control.

Methodological Considerations

Important methodological considerations include testing measurement invariance of constructs across time, appropriately handling missing data, and using accelerated longitudinal designs that sample different age cohorts over overlapping time periods.

Testing measurement invariance

Testing measurement invariance involves evaluating whether the same construct is being measured in a consistent, comparable way across multiple time points in longitudinal research.

This includes assessing configural, metric, and scalar invariance through confirmatory factor analytic approaches. Ensuring invariance gives more confidence when drawing inferences about change over time.

Missing data

Missing data can occur during initial sampling if certain groups are underrepresented or fail to respond.

Attrition over time is the main source – participants dropping out for various reasons. The consequences of missing data are reduced statistical power and potential bias if dropout is nonrandom.

Handling missing data appropriately in longitudinal studies is critical to reducing bias and maintaining power.

It is important to minimize attrition by tracking participants, keeping contact info up to date, engaging them, and providing incentives over time.

Techniques like maximum likelihood estimation and multiple imputation are better alternatives to older methods like listwise deletion. Assumptions about missing data mechanisms (e.g., missing at random) shape the analytic approaches taken.

Accelerated longitudinal designs

Accelerated longitudinal designs purposefully create missing data across age groups.

Accelerated longitudinal designs strategically sample different age cohorts at overlapping periods. For example, assessing 6th, 7th, and 8th graders at yearly intervals would cover 6-8th grade development over a 3-year study rather than following a single cohort over that timespan.

This increases the speed and cost-efficiency of longitudinal data collection and enables the examination of age/cohort effects. Appropriate multilevel statistical models are required to analyze the resulting complex data structure.

In addition to those considerations, optimizing the time lags between measurements, maximizing participant retention, and thoughtfully selecting analysis models that align with the research questions and hypotheses are also vital in ensuring robust longitudinal research.

So, careful methodology is key throughout the design and analysis process when working with repeated-measures data.

Cohort effects

A cohort refers to a group born in the same year or time period. Cohort effects occur when different cohorts show differing trajectories over time.

Cohort effects can bias results if not accounted for, especially in accelerated longitudinal designs which assume cohort equivalence.

Detecting cohort effects is important but can be challenging as they are confounded with age and time of measurement effects.

Cohort effects can also interfere with estimating other effects like retest effects. This happens because comparing groups to estimate retest effects relies on cohort equivalence.

Overall, researchers need to test for and control cohort effects which could otherwise lead to invalid conclusions. Careful study design and analysis is required.

Retest effects

Retest effects refer to gains in performance that occur when the same or similar test is administered on multiple occasions.

For example, familiarity with test items and procedures may allow participants to improve their scores over repeated testing above and beyond any true change.

Specific examples include:

- Memory tests – Learning which items tend to be tested can artificially boost performance over time

- Cognitive tests – Becoming familiar with the testing format and particular test demands can inflate scores

- Survey measures – Remembering previous responses can bias future responses over multiple administrations

- Interviews – Comfort with the interviewer and process can lead to increased openness or recall

To estimate retest effects, performance of retested groups is compared to groups taking the test for the first time. Any divergence suggests inflated scores due to retesting rather than true change.

If unchecked in analysis, retest gains can be confused with genuine intraindividual change or interindividual differences.

This undermines the validity of longitudinal findings. Thus, testing and controlling for retest effects are important considerations in longitudinal research.

Data Analysis

Longitudinal data involves repeated assessments of variables over time, allowing researchers to study stability and change. A variety of statistical models can be used to analyze longitudinal data, including latent growth curve models, multilevel models, latent state-trait models, and more.

Latent growth curve models allow researchers to model intraindividual change over time. For example, one could estimate parameters related to individuals’ baseline levels on some measure, linear or nonlinear trajectory of change over time, and variability around those growth parameters. These models require multiple waves of longitudinal data to estimate.

Multilevel models are useful for hierarchically structured longitudinal data, with lower-level observations (e.g., repeated measures) nested within higher-level units (e.g., individuals). They can model variability both within and between individuals over time.

Latent state-trait models decompose the covariance between longitudinal measurements into time-invariant trait factors, time-specific state residuals, and error variance. This allows separating stable between-person differences from within-person fluctuations.

There are many other techniques like latent transition analysis, event history analysis, and time series models that have specialized uses for particular research questions with longitudinal data. The choice of model depends on the hypotheses, timescale of measurements, age range covered, and other factors.

In general, these various statistical models allow investigation of important questions about developmental processes, change and stability over time, causal sequencing, and both between- and within-person sources of variability. However, researchers must carefully consider the assumptions behind the models they choose.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different observational study designs where researchers analyze a target population without manipulating or altering the natural environment in which the participants exist.

Yet, there are apparent differences between these two forms of study. One key difference is that longitudinal studies follow the same sample of people over an extended period of time, while cross-sectional studies look at the characteristics of different populations at a given moment in time.

Longitudinal studies tend to require more time and resources, but they can be used to detect cause-and-effect relationships and establish patterns among subjects.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies tend to be cheaper and quicker but can only provide a snapshot of a point in time and thus cannot identify cause-and-effect relationships.

Both studies are valuable for psychologists to observe a given group of subjects. Still, cross-sectional studies are more beneficial for establishing associations between variables, while longitudinal studies are necessary for examining a sequence of events.

1. Are longitudinal studies qualitative or quantitative?

Longitudinal studies are typically quantitative. They collect numerical data from the same subjects to track changes and identify trends or patterns.

However, they can also include qualitative elements, such as interviews or observations, to provide a more in-depth understanding of the studied phenomena.

2. What’s the difference between a longitudinal and case-control study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively and cannot be used to calculate relative risk. Longitudinal studies, though, can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In case-control studies, researchers study one group of people who have developed a particular condition and compare them to a sample without the disease.

Case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies are conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. Does a longitudinal study have a control group?

Yes, a longitudinal study can have a control group . In such a design, one group (the experimental group) would receive treatment or intervention, while the other group (the control group) would not.

Both groups would then be observed over time to see if there are differences in outcomes, which could suggest an effect of the treatment or intervention.

However, not all longitudinal studies have a control group, especially observational ones and not testing a specific intervention.

Baltes, P. B., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1979). History and rationale of longitudinal research. In J. R. Nesselroade & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), (pp. 1–39). Academic Press.

Cook, N. R., & Ware, J. H. (1983). Design and analysis methods for longitudinal research. Annual review of public health , 4, 1–23.

Fitchett, G., Rybarczyk, B., Demarco, G., & Nicholas, J.J. (1999). The role of religion in medical rehabilitation outcomes: A longitudinal study. Rehabilitation Psychology, 44, 333-353.

Harvard Second Generation Study. (n.d.). Harvard Second Generation Grant and Glueck Study. Harvard Study of Adult Development. Retrieved from https://www.adultdevelopmentstudy.org.

Le Mare, L., & Audet, K. (2006). A longitudinal study of the physical growth and health of postinstitutionalized Romanian adoptees. Pediatrics & child health, 11 (2), 85-91.

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Social science & medicine (1982), 74 (6), 907–914.

Marques, S. C., Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2011). The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 12( 6), 1049–1062.

Sidney W.A. Dekker & Wilmar B. Schaufeli (1995) The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: A longitudinal study, Australian Psychologist, 30: 1,57-63.

Stice, E., Mazotti, L., Krebs, M., & Martin, S. (1998). Predictors of adolescent dieting behaviors: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12 (3), 195–205.

Tegan Cruwys, Katharine H Greenaway & S Alexander Haslam (2015) The Stress of Passing Through an Educational Bottleneck: A Longitudinal Study of Psychology Honours Students, Australian Psychologist, 50:5, 372-381.

Thomas, L. (2020). What is a longitudinal study? Scribbr. Retrieved from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., Meeus, W., & Deković, M. (2006). Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20 (2), 107–116.

Further Information

- Schaie, K. W. (2005). What can we learn from longitudinal studies of adult development?. Research in human development, 2 (3), 133-158.

- Caruana, E. J., Roman, M., Hernández-Sánchez, J., & Solli, P. (2015). Longitudinal studies. Journal of thoracic disease, 7 (11), E537.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- What’s a Longitudinal Study? Types, Uses & Examples

Research can take anything from a few minutes to years or even decades to complete. When a systematic investigation goes on for an extended period, it’s most likely that the researcher is carrying out a longitudinal study of the sample population. So how does this work?

In the most simple terms, a longitudinal study involves observing the interactions of the different variables in your research population, exposing them to various causal factors, and documenting the effects of this exposure. It’s an intelligent way to establish causal relationships within your sample population.

In this article, we’ll show you several ways to adopt longitudinal studies for your systematic investigation and how to avoid common pitfalls.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

A longitudinal study is a correlational research method that helps discover the relationship between variables in a specific target population. It is pretty similar to a cross-sectional study , although in its case, the researcher observes the variables for a longer time, sometimes lasting many years.

For example, let’s say you are researching social interactions among wild cats. You go ahead to recruit a set of newly-born lion cubs and study how they relate with each other as they grow. Periodically, you collect the same types of data from the group to track their development.

The advantage of this extended observation is that the researcher can witness the sequence of events leading to the changes in the traits of both the target population and the different groups. It can identify the causal factors for these changes and their long-term impact.

Characteristics of Longitudinal Studies

1. Non-interference: In longitudinal studies, the researcher doesn’t interfere with the participants’ day-to-day activities in any way. When it’s time to collect their responses , the researcher administers a survey with qualitative and quantitative questions .

2. Observational: As we mentioned earlier, longitudinal studies involve observing the research participants throughout the study and recording any changes in traits that you notice.

3. Timeline: A longitudinal study can span weeks, months, years, or even decades. This dramatically contrasts what is obtainable in cross-sectional studies that only last for a short time.

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Studies

- Definition

A cross-sectional study is a type of observational study in which the researcher collects data from variables at a specific moment to establish a relationship among them. On the other hand, longitudinal research observes variables for an extended period and records all the changes in their relationship.

Longitudinal studies take a longer time to complete. In some cases, the researchers can spend years documenting the changes among the variables plus their relationships. For cross-sectional studies, this isn’t the case. Instead, the researcher collects information in a relatively short time frame and makes relevant inferences from this data.

While cross-sectional studies give you a snapshot of the situation in the research environment, longitudinal studies are better suited for contexts where you need to analyze a problem long-term.

- Sample Data

Longitudinal studies repeatedly observe the same sample population, while cross-sectional studies are conducted with different research samples.

Because longitudinal studies span over a more extended time, they typically cost more money than cross-sectional observations.

Types of Longitudinal Studies

The three main types of longitudinal studies are:

- Panel Study

- Retrospective Study

- Cohort Study

These methods help researchers to study variables and account for qualitative and quantitative data from the research sample.

1. Panel Study

In a panel study, the researcher uses data collection methods like surveys to gather information from a fixed number of variables at regular but distant intervals, often spinning into a few years. It’s primarily designed for quantitative research, although you can use this method for qualitative data analysis .

When To Use Panel Study

If you want to have first-hand, factual information about the changes in a sample population, then you should opt for a panel study. For example, medical researchers rely on panel studies to identify the causes of age-related changes and their consequences.

Advantages of Panel Study

- It helps you identify the causal factors of changes in a research sample.

- It also allows you to witness the impact of these changes on the properties of the variables and information needed at different points of their existing relationship.

- Panel studies can be used to obtain historical data from the sample population.

Disadvantages of Panel Studies

- Conducting a panel study is pretty expensive in terms of time and resources.

- It might be challenging to gather the same quality of data from respondents at every interval.

2. Retrospective Study

In a retrospective study, the researcher depends on existing information from previous systematic investigations to discover patterns leading to the study outcomes. In other words, a retrospective study looks backward. It examines exposures to suspected risk or protection factors concerning an outcome established at the start of the study.

When To Use Retrospective Study

Retrospective studies are best for research contexts where you want to quickly estimate an exposure’s effect on an outcome. It also helps you to discover preliminary measures of association in your data.

Medical researchers adopt retrospective study methods when they need to research rare conditions.

Advantages of Retrospective Study

- Retrospective studies happen at a relatively smaller scale and do not require much time to complete.

- It helps you to study rare outcomes when prospective surveys are not feasible.

Disadvantages of Retrospective Study

- It is easily affected by recall bias or misclassification bias.

- It often depends on convenience sampling, which is prone to selection bias.

3. Cohort Study

A cohort study entails collecting information from a group of people who share specific traits or have experienced a particular occurrence simultaneously. For example, a researcher might conduct a cohort study on a group of Black school children in the U.K.

During cohort study, the researcher exposes some group members to a specific characteristic or risk factor. Then, she records the outcome of this exposure and its impact on the exposed variables.

When To Use Cohort Study

You should conduct a cohort study if you’re looking to establish a causal relationship within your data sets. For example, in medical research, cohort studies investigate the causes of disease and establish links between risk factors and effects.

Advantages of Cohort Studies

- It allows you to study multiple outcomes that can be associated with one risk factor.

- Cohort studies are designed to help you measure all variables of interest.

Disadvantages of Cohort Studies

- Cohort studies are expensive to conduct.

- Throughout the process, the researcher has less control over variables.

When Would You Use a Longitudinal Study?

If you’re looking to discover the relationship between variables and the causal factors responsible for changes, you should adopt a longitudinal approach to your systematic investigation. Longitudinal studies help you to analyze change over a meaningful time.

How to Perform a Longitudinal Study?

There are only two approaches you can take when performing a longitudinal study. You can either source your own data or use previously gathered data.

1. Sourcing for your own data

Collecting your own data is a more verifiable method because you can trust your own data. The way you collect your data is also heavily dependent on the type of study you’re conducting.

If you’re conducting a retrospective study, you’d have to collect data on events that have already happened. An example is going through records to find patterns in cancer patients.

For a prospective study, you collect the data in real-time. This means finding a sample population, following them, and documenting your findings over the course of your study.

Irrespective of what study type you’d be conducting, you need a versatile data collection tool to help you accurately record your data. One we strongly recommend is Formplus . Signup here for free.

2. Using previously gathered data

Governmental and research institutes often carry out longitudinal studies and make the data available to the public. So you can pick up their previously researched data and use them for your own study. An example is the UK data service website .

Using previously gathered data isn’t just easy, they also allow you to carry out research over a long period of time.

The downside to this method is that it’s very restrictive because you can only use the data set available to you. You also have to thoroughly examine the source of the data given to you.

Advantages of a Longitudinal Study

- Longitudinal studies help you discover variable patterns over time, leading to more precise causal relationships and research outcomes.

- When researching developmental trends, longitudinal studies allow you to discover changes across lifespans and arrive at valid research outcomes.

- They are highly flexible, which means the researcher can adjust the study’s focus while it is ongoing.

- Unlike other research methods, longitudinal studies collect unique, long-term data and highlight relationships that cannot be discovered in a short-term investigation.

- You can collect additional data to study unexpected findings at any point in your systematic investigation.

Disadvantages and Limitations of a Longitudinal Study

- It’s difficult to predict the results of longitudinal studies because of the extended time frame. Also, it may take several years before the data begins to produce observable patterns or relationships that can be monitored.

- It costs lots of money to sustain a research effort for years. You’ll keep incurring costs every year compared to other forms of research that can be completed in a smaller fraction of the time.

- Longitudinal studies require a large sample size which might be challenging to achieve. Without this, the entire investigation will have little or no impact.

- Longitudinal studies often experience panel attrition. This happens when some members of the research sample are unable to complete the study due to several reasons like changes in contact details, refusal, incapacity, and even death.

Longitudinal Studies Examples

How does a longitudinal study work in the real world? To answer this, let’s consider a few typical scenarios.

A researcher wants to know the effects of a low-carb diet on weight loss. So, he gathers a group of obese men and kicks off the systematic investigation using his preferred longitudinal study method. He records information like how much they weigh, the number of carbs in their diet, and the like at different points. All these data help him to arrive at valid research outcomes.

Use for Free: Macros Calories Diet Plan Template

A researcher wants to know if there’s any relationship between children who drink milk before school and high classroom performance . First, he uses a sampling technique to gather a large research population.

Then, he conducts a baseline survey to establish the premise of the research for later comparison. Next, the researcher gives a log to each participant to keep track of predetermined research variables .

Example 3

You decide to study how a particular diet affects athletes’ performance over time. First, you gather your sample population , establish a baseline for the research, and observe and record the required data.

Longitudinal Studies Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Are Longitudinal Studies Quantitative or Qualitative?

Longitudinal studies are primarily a qualitative research method because the researcher observes and records changes in variables over an extended period. However, it can also be used to gather quantitative data depending on your research context.

- What Is Most Likely the Biggest Problem with Longitudinal Research?

The biggest challenge with longitudinal research is panel attrition. Due to the length of the research process, some variables might be unable to complete the study for one reason or the other. When this happens, it can distort your data and research outcomes.

- What is Longitudinal Data Collection?

Longitudinal data collection is the process of gathering information from the same sample population over a long period. Longitudinal data collection uses interviews, surveys, and observation to collect the required information from research sources.

- What is the Difference Between Longitudinal Data and a Time Series Analysis?

Because longitudinal studies collect data over a long period, they are often mistaken for time series analysis. So what’s the real difference between these two concepts?

In a time series analysis, the researcher focuses on a single individual at multiple time intervals. Meanwhile, longitudinal data focuses on multiple individuals at various time intervals.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- cohort study

- cross-sectional study

- longitudinal study

- longitudinal study faq

- panel study

- retrospective cohort study

- sample data

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Selection Bias in Research: Types, Examples & Impact

In this article, we’ll discuss the effects of selection bias, how it works, its common effects and the best ways to minimize it.

11 Retrospective vs Prospective Cohort Study Differences

differences between retrospective and prospective cohort studies in definitions, examples, data collection, analysis, advantages, sample...

Cross-Sectional Studies: Types, Pros, Cons & Uses

In this article, we’ll look at what cross-sectional studies are, how it applies to your research and how to use Formplus to collect...

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

What is a Longitudinal Study?: Definition and Explanation

In this article, we’ll cover all you need to know about longitudinal research.

Let’s take a closer look at the defining characteristics of longitudinal studies, review the pros and cons of this type of research, and share some useful longitudinal study examples.

Content Index

What is a longitudinal study?

Types of longitudinal studies, advantages and disadvantages of conducting longitudinal surveys.

- Longitudinal studies vs. cross-sectional studies

Types of surveys that use a longitudinal study

Longitudinal study examples.

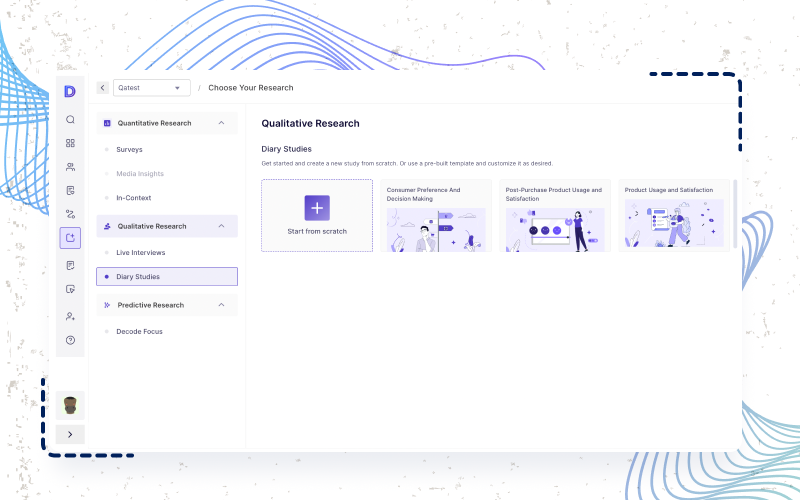

A longitudinal study is a research conducted over an extended period of time. It is mostly used in medical research and other areas like psychology or sociology.

When using this method, a longitudinal survey can pay off with actionable insights when you have the time to engage in a long-term research project.

Longitudinal studies often use surveys to collect data that is either qualitative or quantitative. Additionally, in a longitudinal study, a survey creator does not interfere with survey participants. Instead, the survey creator distributes questionnaires over time to observe changes in participants, behaviors, or attitudes.

Many medical studies are longitudinal; researchers note and collect data from the same subjects over what can be many years.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Longitudinal studies are versatile, repeatable, and able to account for quantitative and qualitative data . Consider the three major types of longitudinal studies for future research:

Panel study: A panel survey involves a sample of people from a more significant population and is conducted at specified intervals for a more extended period.

One of the panel study’s essential features is that researchers collect data from the same sample at different points in time. Most panel studies are designed for quantitative analysis , though they may also be used to collect qualitative data and unit of analysis .

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Cohort Study: A cohort study samples a cohort (a group of people who typically experience the same event at a given point in time). Medical researchers tend to conduct cohort studies. Some might consider clinical trials similar to cohort studies.

In cohort studies, researchers merely observe participants without intervention, unlike clinical trials in which participants undergo tests.

Retrospective study: A retrospective study uses already existing data, collected during previously conducted research with similar methodology and variables.

While doing a retrospective study, the researcher uses an administrative database, pre-existing medical records, or one-to-one interviews.

As we’ve demonstrated, a longitudinal study is useful in science, medicine, and many other fields. There are many reasons why a researcher might want to conduct a longitudinal study. One of the essential reasons is, longitudinal studies give unique insights that many other types of research fail to provide.

Advantages of longitudinal studies

- Greater validation: For a long-term study to be successful, objectives and rules must be established from the beginning. As it is a long-term study, its authenticity is verified in advance, which makes the results have a high level of validity.

- Unique data: Most research studies collect short-term data to determine the cause and effect of what is being investigated. Longitudinal surveys follow the same principles but the data collection period is different. Long-term relationships cannot be discovered in a short-term investigation, but short-term relationships can be monitored in a long-term investigation.

- Allow identifying trends: Whether in medicine, psychology, or sociology, the long-term design of a longitudinal study enables trends and relationships to be found within the data collected in real time. The previous data can be applied to know future results and have great discoveries.

- Longitudinal surveys are flexible: Although a longitudinal study can be created to study a specific data point, the data collected can show unforeseen patterns or relationships that can be significant. Because this is a long-term study, the researchers have a flexibility that is not possible with other research formats.

Additional data points can be collected to study unexpected findings, allowing changes to be made to the survey based on the approach that is detected.

Disadvantages of longitudinal studies

- Research time The main disadvantage of longitudinal surveys is that long-term research is more likely to give unpredictable results. For example, if the same person is not found to update the study, the research cannot be carried out. It may also take several years before the data begins to produce observable patterns or relationships that can be monitored.

- An unpredictability factor is always present It must be taken into account that the initial sample can be lost over time. Because longitudinal studies involve the same subjects over a long period of time, what happens to them outside of data collection times can influence the data that is collected in the future. Some people may decide to stop participating in the research. Others may not be in the correct demographics for research. If these factors are not included in the initial research design, they could affect the findings that are generated.

- Large samples are needed for the investigation to be meaningful To develop relationships or patterns, a large amount of data must be collected and extracted to generate results.

- Higher costs Without a doubt, the longitudinal survey is more complex and expensive. Being a long-term form of research, the costs of the study will span years or decades, compared to other forms of research that can be completed in a smaller fraction of the time.

Longitudinal studies vs. Cross-sectional studies

Longitudinal studies are often confused with cross-sectional studies. Unlike longitudinal studies, where the research variables can change during a study, a cross-sectional study observes a single instance with all variables remaining the same throughout the study. A longitudinal study may follow up on a cross-sectional study to investigate the relationship between the variables more thoroughly.

The design of the study is highly dependent on the nature of the research questions . Whenever a researcher decides to collect data by surveying their participants, what matters most are the questions that are asked in the survey.

Knowing what information a study should gather is the first step in determining how to conduct the rest of the study.

With a longitudinal study, you can measure and compare various business and branding aspects by deploying surveys. Some of the classic examples of surveys that researchers can use for longitudinal studies are:

Market trends and brand awareness: Use a market research survey and marketing survey to identify market trends and develop brand awareness. Through these surveys, businesses or organizations can learn what customers want and what they will discard. This study can be carried over time to assess market trends repeatedly, as they are volatile and tend to change constantly.

Product feedback: If a business or brand launches a new product and wants to know how it is faring with consumers, product feedback surveys are a great option. Collect feedback from customers about the product over an extended time. Once you’ve collected the data, it’s time to put that feedback into practice and improve your offerings.

Customer satisfaction: Customer satisfaction surveys help an organization get to know the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction among its customers. A longitudinal survey can gain feedback from new and regular customers for as long as you’d like to collect it, so it’s useful whether you’re starting a business or hoping to make some improvements to an established brand.

Employee engagement: When you check in regularly over time with a longitudinal survey, you’ll get a big-picture perspective of your company culture. Find out whether employees feel comfortable collaborating with colleagues and gauge their level of motivation at work.

Now that you know the basics of how researchers use longitudinal studies across several disciplines let’s review the following examples:

Example 1: Identical twins

Consider a study conducted to understand the similarities or differences between identical twins who are brought up together versus identical twins who were not. The study observes several variables, but the constant is that all the participants have identical twins.

In this case, researchers would want to observe these participants from childhood to adulthood, to understand how growing up in different environments influences traits, habits, and personality.

LEARN MORE ABOUT: Personality Survey

Over many years, researchers can see both sets of twins as they experience life without intervention. Because the participants share the same genes, it is assumed that any differences are due to environmental analysis , but only an attentive study can conclude those assumptions.

Example 2: Violence and video games

A group of researchers is studying whether there is a link between violence and video game usage. They collect a large sample of participants for the study. To reduce the amount of interference with their natural habits, these individuals come from a population that already plays video games. The age group is focused on teenagers (13-19 years old).

The researchers record how prone to violence participants in the sample are at the onset. It creates a baseline for later comparisons. Now the researchers will give a log to each participant to keep track of how much and how frequently they play and how much time they spend playing video games. This study can go on for months or years. During this time, the researcher can compare video game-playing behaviors with violent tendencies. Thus, investigating whether there is a link between violence and video games.

Conducting a longitudinal study with surveys is straightforward and applicable to almost any discipline. With our survey software you can easily start your own survey today.

GET STARTED

MORE LIKE THIS

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Trend Report: Guide for Market Dynamics & Strategic Analysis

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Longitudinal Study?

Tracking Variables Over Time

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amanda Tust is a fact-checker, researcher, and writer with a Master of Science in Journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amanda-Tust-1000-ffe096be0137462fbfba1f0759e07eb9.jpg)

Steve McAlister / The Image Bank / Getty Images

The Typical Longitudinal Study

Potential pitfalls, frequently asked questions.

A longitudinal study follows what happens to selected variables over an extended time. Psychologists use the longitudinal study design to explore possible relationships among variables in the same group of individuals over an extended period.

Once researchers have determined the study's scope, participants, and procedures, most longitudinal studies begin with baseline data collection. In the days, months, years, or even decades that follow, they continually gather more information so they can observe how variables change over time relative to the baseline.

For example, imagine that researchers are interested in the mental health benefits of exercise in middle age and how exercise affects cognitive health as people age. The researchers hypothesize that people who are more physically fit in their 40s and 50s will be less likely to experience cognitive declines in their 70s and 80s.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Longitudinal studies, a type of correlational research , are usually observational, in contrast with cross-sectional research . Longitudinal research involves collecting data over an extended time, whereas cross-sectional research involves collecting data at a single point.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers recruit participants who are in their mid-40s to early 50s. They collect data related to current physical fitness, exercise habits, and performance on cognitive function tests. The researchers continue to track activity levels and test results for a certain number of years, look for trends in and relationships among the studied variables, and test the data against their hypothesis to form a conclusion.

Examples of Early Longitudinal Study Design

Examples of longitudinal studies extend back to the 17th century, when King Louis XIV periodically gathered information from his Canadian subjects, including their ages, marital statuses, occupations, and assets such as livestock and land. He used the data to spot trends over the years and understand his colonies' health and economic viability.

In the 18th century, Count Philibert Gueneau de Montbeillard conducted the first recorded longitudinal study when he measured his son every six months and published the information in "Histoire Naturelle."

The Genetic Studies of Genius (also known as the Terman Study of the Gifted), which began in 1921, is one of the first studies to follow participants from childhood into adulthood. Psychologist Lewis Terman's goal was to examine the similarities among gifted children and disprove the common assumption at the time that gifted children were "socially inept."

Types of Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal studies fall into three main categories.

- Panel study : Sampling of a cross-section of individuals

- Cohort study : Sampling of a group based on a specific event, such as birth, geographic location, or experience

- Retrospective study : Review of historical information such as medical records

Benefits of Longitudinal Research

A longitudinal study can provide valuable insight that other studies can't. They're particularly useful when studying developmental and lifespan issues because they allow glimpses into changes and possible reasons for them.

For example, some longitudinal studies have explored differences and similarities among identical twins, some reared together and some apart. In these types of studies, researchers tracked participants from childhood into adulthood to see how environment influences personality , achievement, and other areas.

Because the participants share the same genetics , researchers chalked up any differences to environmental factors . Researchers can then look at what the participants have in common and where they differ to see which characteristics are more strongly influenced by either genetics or experience. Note that adoption agencies no longer separate twins, so such studies are unlikely today. Longitudinal studies on twins have shifted to those within the same household.

As with other types of psychology research, researchers must take into account some common challenges when considering, designing, and performing a longitudinal study.

Longitudinal studies require time and are often quite expensive. Because of this, these studies often have only a small group of subjects, which makes it difficult to apply the results to a larger population.

Selective Attrition

Participants sometimes drop out of a study for any number of reasons, like moving away from the area, illness, or simply losing motivation . This tendency, known as selective attrition , shrinks the sample size and decreases the amount of data collected.

If the final group no longer reflects the original representative sample , attrition can threaten the validity of the experiment. Validity refers to whether or not a test or experiment accurately measures what it claims to measure. If the final group of participants doesn't represent the larger group accurately, generalizing the study's conclusions is difficult.

The World’s Longest-Running Longitudinal Study

Lewis Terman aimed to investigate how highly intelligent children develop into adulthood with his "Genetic Studies of Genius." Results from this study were still being compiled into the 2000s. However, Terman was a proponent of eugenics and has been accused of letting his own sexism , racism , and economic prejudice influence his study and of drawing major conclusions from weak evidence. However, Terman's study remains influential in longitudinal studies. For example, a recent study found new information on the original Terman sample, which indicated that men who skipped a grade as children went on to have higher incomes than those who didn't.

A Word From Verywell

Longitudinal studies can provide a wealth of valuable information that would be difficult to gather any other way. Despite the typical expense and time involved, longitudinal studies from the past continue to influence and inspire researchers and students today.

A longitudinal study follows up with the same sample (i.e., group of people) over time, whereas a cross-sectional study examines one sample at a single point in time, like a snapshot.

A longitudinal study can occur over any length of time, from a few weeks to a few decades or even longer.

That depends on what researchers are investigating. A researcher can measure data on just one participant or thousands over time. The larger the sample size, of course, the more likely the study is to yield results that can be extrapolated.

Piccinin AM, Knight JE. History of longitudinal studies of psychological aging . Encyclopedia of Geropsychology. 2017:1103-1109. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_103

Terman L. Study of the gifted . In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. 2018. doi:10.4135/9781506326139.n691

Sahu M, Prasuna JG. Twin studies: A unique epidemiological tool . Indian J Community Med . 2016;41(3):177-182. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.183593

Almqvist C, Lichtenstein P. Pediatric twin studies . In: Twin Research for Everyone . Elsevier; 2022:431-438.

Warne RT. An evaluation (and vindication?) of Lewis Terman: What the father of gifted education can teach the 21st century . Gifted Child Q. 2018;63(1):3-21. doi:10.1177/0016986218799433

Warne RT, Liu JK. Income differences among grade skippers and non-grade skippers across genders in the Terman sample, 1936–1976 . Learning and Instruction. 2017;47:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.10.004

Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations . Chest . 2020;158(1S):S65-S71. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernández-Sánchez J, Solli P. Longitudinal studies . J Thorac Dis . 2015;7(11):E537-E540. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Insights AI

Table of Content

What is a longitudinal study definition, types, and examples.

Is your long-term research strategy unclear? Learn how longitudinal studies decode complexity. Read on for insights.

Have you ever wondered why certain questions can only be answered by going back in time?

Imagine being able to predict the long-term success of a new marketing campaign—not necessarily just from the first click-through rates, but from tracking the customer journey month after month or even year after year. This might include tracking brand awareness , purchase behavior, and customer satisfaction at appropriate intervals. This is where longitudinal studies, like time travelers, enter the research world to decode change and development across individuals, populations, and entire societies.

In this blog, we not only define what longitudinal studies are but also explore the different types and find real-world examples that prove the advantage of this research approach.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

A longitudinal study is a type of research where the scope of the study is observed and studied in the same set of people over a long period of time. This could be from a few weeks to many years.

They are most often found in different fields like health, economics, and medicine. They serve to give knowledge of the passage of events without knowing what is happening.

A company may conduct a study to observe how things change with time without interfering with what's happening. For example, an e-commerce company may ask the same questions to the same people every few months or years to determine whether the advertisement is working or whether more people are falling in love with their products.

Types of Longitudinal Studies

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies follow specific groups, or cohorts, of individuals over time. These groups usually share a common characteristic, such as being born in the same year or living in the same area. Researchers observe how this group changes and develops, often focusing on the impact of certain exposures or events on their health, behavior, or other outcomes.

Key Points:

Selection: Participants are chosen based on a shared characteristic.

Focus: Studying the effects of exposures or experiences on the group.

Example: The Nurses' Health Study , a large prospective cohort study launched in 1976, has followed over 100,000 female nurses to investigate various risk factors for chronic diseases like heart disease, cancer, and dementia. By observing their health and lifestyle choices over decades, researchers have gained valuable insights into the long-term impact of different factors on health outcomes.

Panel Studies

Panel studies involve collecting data from the same group of individuals at multiple time points. Unlike cohort studies, panel studies focus on the same people rather than forming groups based on shared characteristics. This allows researchers to examine individual-level changes over time.

Selection: Representative sample of a larger population.

Focus: Observing general trends and changes within the sample.

Example: The American National Election Studies (ANES) is a long-running panel study that surveys a representative sample of the US population every two years. This allows researchers to track changes in public opinion on various political and social issues over time, revealing trends in voter preferences and societal attitudes.

Retrospective Studies

Retrospective studies look back in time to collect data on past events or behaviors. Researchers gather information from participants about their past experiences and then follow up with them to track outcomes. These studies are useful for investigating long-term effects or rare events.

Data source: Existing records, medical charts, surveys, etc.

Focus: Analyzing past data to identify trends and associations.

Example: The Danish National Birth Cohort study utilizes existing data from national registries, following all individuals born in Denmark since 1996. Researchers can analyze their health records, educational attainment, and socioeconomic data to identify risk factors for various health conditions. By analyzing historical data over a long period, researchers can investigate the long-term consequences of early-life exposures on health outcomes later in life. This can inform preventative measures and interventions during critical developmental stages.

Pros & Cons of Longitudinal Studies

Advantages of longitudinal studies, understanding change.

They can give some of the most valuable insights into the way people, population, or phenomena change over time, enabling a researcher to trace trends, patterns, and causal relations that would be invisible in a snapshot view.

Cause-and-effect Insights

Longitudinal studies—though not conclusive—can add to the understanding of potential cause-and-effect relationships by tracing how changes in one variable herald changes in another.

Rare Events

They can trace events that are rare and that, in a snapshot study, might not be seen. It provides data about rare occurrences.

Generalizability

Longitudinal studies can yield generalizable results depending on sample size and ways of selecting the sample.

Disadvantages of Longitudinal Studies

Time and resource intensive.

Conducting longitudinal studies can take years and usually requires hundreds of hours of time, resources, and sustained participant engagement. Thus, this is often the major barrier, particularly for long-term studies.

Participants who drop out of a study can also affect generalizability and introduce bias. The researcher will need to develop strategies to minimize attrition and control for possible biases.

Taking repeated data from the same participants can be expensive and will require a substantial amount of funding and logistical planning.

Delayed Results

Due to its extended duration, it may take years to notice meaningful changes and to obtain definitive results. This must be braved with challenges, while the research area requires an immediate solution.

Longitudinal studies have significant advantages in the study of change and development through time. However, there are substantial challenges in the design and conduct of such research that need to be pondered carefully.

Ways to Collect Longitudinal Study Data