Danielle Anne Lynch

Music, theology, education, liturgy, more challenges of teaching religious education.

The post I wrote in 2015 on the challenges of teaching RE consistently is top of the list of my posts, and I’ve been contemplating writing a follow-up post for years! And now I have… To the three challenges I outlined there (whilst I was still fresh to Australia, having moved from the UK only a month earlier) – 1. challenge misconceptions; 2. breadth or depth?; and 3. clarifying the purpose of RE – I would add three more in this musing: 4. relevance to the lives of young people; and 5. the holistic growth of the students; and 6. professional development of teachers. This is not intended to be a comprehensive list of challenges, as indeed many they are, nor have I outlined each in as much depth as I could. There is probably another post to be had in four years time.

4. Relevance to the Lives of Young People

We’ve seen the census data. Even taking into account that the Australian census changed the order of options to put ‘no religion’ at the top of the list, there has been a marked decline in affiliation with religion in Australia, as there has in the UK and many other countries. However, young people have many big questions that they want to explore: we might call these unanswerable questions, profound questions, ultimate questions, or something else. Having space and time to air these and explore possible responses is an essential part of developing critical thinking skills. We need to teach students to think critically about their interactions and encounters in the world, how they live and who they want to become, and the challenges that they are likely to encounter. What is evident is that many young people want to make a positive difference in the world. However, some are unsure how to do that, and need much guidance from their teachers. Others have clear ideas and can be supported to develop them further.

For many young people, the teachings of religious traditions are simply not relevant to their lives: they do not even register, so out of touch with reality are the traditions perceived to be. Yet they are the source of thinking material for students to consider their profound questions. However, w e must teach students to be prophetic when they encounter religious traditions critically: they must name positive qualities and failings according to the evidence. The crisis of abuse in the Catholic Church is a major stumbling block for many people to even engage on any level with the religious institution (not to mention broader issues of hypocrisy, discrimination, etc.). Some might be inclined to name this as a challenge all on its own, yet I don’t think that is so, because when teachers engage authentically with students around this issue, this becomes relevant to their lives, and allows them an important role in the truth-telling that is required for the process of healing to even begin.

5. The Holistic Growth of the Students

OK, so this one ties in with number 2 – the purpose of RE – but my thinking has developed on this since 2015. One of the reasons for this has been my involvement in the creation of a new program of Religious Education for senior students (Year 11 and 12) in Cairns Diocese, Catholic Faith in Action. One anecdotal account which demonstrates this: Year 11 visit a nursing home to spend time with the residents, building cross-generational relationships, listening and telling stories together. They get to experience the joy of the residents in having new faces in their midst, people who are there just to be present with them, and they feel affirmed in their innate value just as human beings. When we discuss ethical issues around the value and quality of life, importance of relationships, human dignity, and social justice (to name some of the important ones) the students have a new perspective.

Another reason is my role as Director of Mission, in which I focus much energy helping students engage in community service and liturgy. What I have seen is that the more students are invited into these other parts of the mission life of a school, the more likely they are to engage in the sort of academic work required to progress in the study of religion. Moreover, if, as was St Marcellin Champagnat’s great aim, the aspiration of the Catholic school is to teach students to be ‘good Christians and good citizens,’ understanding themselves as spiritual beings and the importance of contributing to society is essential. The Marist theme this year, ‘Holy Today,’ encourages us to recognise the extraordinary in the ordinary: to do the small things well knowing the impact of doing so extends far beyond our imaginations.

6. The Professional Development of Teachers

The RE department in which I work seems to have a revolving door. Due to frequent staffing changes, for many reasons, the make-up of the department is regularly changing. This being my only experience of school life in Australia, I don’t know how representative that is of secondary schools. It existed to a much lesser extent in one of the schools I taught in back in England. What it means is that we often have teachers in front of a Religion class who have limited subject knowledge and experience in teaching Religion. So how do we support them to teach religion well? As much as it pains me when my Year 11 class report to me literal interpretations of scripture (especially Creation accounts) as if such beliefs they are representative for all Christians, I realise that somewhere (or perhaps everywhere) in their history of learning in religion, we have failed them.

There are a few things I’ve done to try to improve the quality of teaching in religion over the last five years. The first is to create a bank of resources to be used and developed by teachers in their teaching. This gives a consistency of approach with a baseline of knowledge to (hopefully) allow students to develop their understanding. Obviously, there are many textbooks which do the same thing, but with the technological resources we have, this includes primarily powerpoint and video resources. Flipped learning is a pedagogical tool we have used in the department. The second is to offer a broad range of professional development and formation experiences. Obviously it makes sense to target this learning on the staff who consistently teach in the department, but it is also worthwhile for staff across the school, regardless of teaching subject, such that all teachers develop their understanding of the Catholic faith, which is helpful when they are called on to teach religion. An understanding of the tradition and charism gives teachers the confidence to teach religion. Understanding fundamental principles of Catholic anthropology, social justice, etc. also allows teachers to be authentic witnesses, living out the Gospel values. Evidently, this encourages the holistic growth of teachers as well as students! Most importantly, teachers need to hear “You are enough!” often and genuinely in order to trust in their own ability to teach religious education effectively.

So there they are, three more challenges of teaching religious education (particularly in a Catholic school).

Photo by Clark Tibbs on Unsplash

Share this:

One comment.

[…] part 2 for more […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Religion and Education Around the World

- 7. How religion may affect educational attainment: scholarly theories and historical background

Table of Contents

- 1. Muslim educational attainment

- 2. Christian educational attainment

- 3. Educational attainment among the religiously unaffiliated

- 4. Buddhist educational attainment

- 5. Hindu educational attainment

- 6. Jewish educational attainment

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Data sources by country

Religion and education, two of humankind’s most ancient endeavors, have long had a close relationship. Historians and social scientists have written about this relationship and about how the two may influence each other.

This chapter presents a broad overview of scholarly research into the ways religion can affect educational achievement. It is not an exhaustive survey of the academic literature, but instead a brief summary of some explanations proposed to account for attainment differences among religious groups. Religion is certainly not the only reason for this variance; many other factors may play an equal or greater role, including economic, geographic, cultural factors and political conditions within a country or region.

The chapter begins with an historical look at ways in which scholars suggest that various religions have influenced education, especially the spread of literacy among laypeople. This section also explores how historical patterns sometimes help explain contemporary patterns in educational attainment. Next, this chapter considers hypotheses about how the cultural norms and doctrines of a religious group may affect educational attainment. It concludes with a look at some leading theories for the stark differences in educational attainment between Christians and Muslims living in sub-Saharan Africa.

Looking to the past

Contemporary access to schooling – a solid pathway to educational attainment – depends on a country’s educational infrastructure. In many instances, the foundations of that infrastructure are based on facilities originally built by religious leaders and organizations to promote learning and spread the faith.

In India, the most learned men (and sometimes women) of ancient times were residents of Buddhist and Hindu monasteries. In the Middle East and Europe, Christian monks built libraries and, in the days before printing presses, preserved important earlier writings produced in Latin, Greek and Arabic. In many cases, these religious monasteries evolved into universities.

Other universities, particularly in the United States and Europe, were built by Christian denominations to educate their clergy and lay followers. Most of these institutions have since become secular in orientation, but their presence may help explain why populations in the U.S. and Europe are highly educated.

Apart from their roles in creating educational infrastructure, religious groups were foundational in fostering societal attitudes toward education.

There is considerable debate among scholars over the degree to which Islam has encouraged or discouraged secular education over the centuries. Some experts note that the first word of the Quran as it was revealed to Prophet Muhammad is “Iqra!” which means “Read!” or “Recite!”; they say Muslims are urged to pursue knowledge in order to better understand God’s revealed word. Early Muslims made innovative intellectual contributions in such fields as mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, medicine and poetry. They established schools, often at mosques, known as katatib and madrasas. 31 Islamic rulers built libraries and educational complexes, such as Baghdad’s House of Wisdom and Cairo’s Al-Azhar University, to nurture advanced scholarship. Under Muslim rule, southern Spain was a center of higher learning, producing such figures as the renowned Muslim philosopher Averroes. 32

But other scholars contend that these educational attainments, and the regard that Muslims had for intellectual inquiry in realms outside religion, were gradually attenuated by a complex mix of social and political events over several centuries. These events included foreign invasions, first by the Mongols, who destroyed the House of Wisdom in 1258, and then by Christians, who pushed Muslims out of Spain in 1492. Some scholars argue that the educational decline began earlier, in the 11th and 12th centuries, and was rooted in institutional changes. In particular, contends Harvard University Associate Professor of Economics Eric Chaney, the decline was caused by an increase in the political power of religious leaders who prioritized Islamic religious learning over scientific education. 33 Their growing influence helped bring about a crucial shift in the Islamic approach to learning: It became dominated by the idea that divine revelation is superior to other types of knowledge, and that religious education should consist of learning only what Islamic scholars had said and written in the past. 34

In the view of some historians, this shift severely constricted intellectual inquiry in the Muslim world as the natural sciences, critical questioning and art were downplayed. 35 Education became primarily the study of established, traditional religious and legal canons. This change also tightened religious scholars’ control over the education of Muslims in Africa and the Middle East – a hold that was not broken until colonial governments and Christian missionaries introduced Western-style educational institutions. 36

Some scholars argue that the decline in secular learning and the narrowing of intellectual inquiry among Muslims have been exaggerated, or did not take place. Columbia University history professor George Saliba writes: “In particular, the decline of Islamic science, which was supposed to have been caused by the religious environment … does not seem to have taken place in reality. On the contrary, if we only look at the surviving scientific documents, we can clearly delineate a very flourishing activity in almost every scientific discipline” after the 12th century. 37

Nowadays, Islamic religious leaders and religious schools still have great influence on education in some Muslim-majority countries, but they compete with government and private schools offering secular topics.

- Christianity

In the view of some scholars, the 16th-century Protestant Reformation was a driving force for public education in Europe. Protestant reformers promoted literacy because of their contention that everyone needed to read the Bible, which they viewed as the essential authority on doctrinal matters. Driven by this theological conviction, religious leaders urged the building of schools and the translation of the Bible into local languages – and Reformation leader Martin Luther set the example by translating the Bible into German.

[which was]

In more recent times, religion was a prime motivator in establishing U.S. schools run by faith groups – including Quakers, Protestants and Catholics – that educated generations of immigrant families. 38

Historically, however, Christianity and science often have come into conflict with each other, as illustrated by the 17th century clash between astronomer Galileo Galilei and the Roman Catholic Church, as well as the condemnation by prominent religious leaders of Charles Darwin’s 1859 theory of human evolution. The Scopes Monkey trial in 1925 further highlighted the rift between science and some branches of Christianity over the theory of evolution, a contentious relationship that endures even today. 39

In sub-Saharan Africa, meanwhile, scholars describe how religious missionaries during colonial times were the prime movers in constructing educational facilities and influencing local attitudes toward education. These missionary activities, the scholars conclude, have had a long-lasting positive impact on access to schooling and educational attainment levels in the region.

Research by Baylor University sociologist Robert D. Woodberry, for instance, suggests that Protestant missionaries in Africa “had a unique role in spreading mass education” because of the importance they placed on ordinary people’s ability to read scripture. As a result, they established schools to promote literacy wherever they went and translated the Bible into indigenous languages. 40

Harvard University economics professor Nathan Nunn, who contends that education was “the main reward used by missionaries to lure Africans into the Christian sphere,” says that in addition to establishing schools, “missionaries may have altered people’s views about the importance of education.” 41

Woodberry and Nunn conclude, however, that Protestant and Catholic missionaries had differing results. Except where they were in direct competition with Protestant missionaries, Catholic missionaries concentrated on educating African elites rather than the masses, Woodberry observes. And Nunn notes that Protestant missionaries placed greater stress than Catholics on educating women. As a result, Protestants had more long-term impact on the education of sub-Saharan African women. 42

Scholars of Buddhism note that Siddhartha Gautama, the religion’s founder, often is called “teacher” because of his emphasis on “the miracle of instruction.” He considered learning essential for attaining the Buddhist goal of enlightenment. 43

“In many ways, Buddhism is particularly dedicated to education because unlike many other religions it contends that a human being can attain his or her own enlightenment (‘salvation’) without divine intervention,” writes Stephen T. Asma, a professor of philosophy at Columbia College Chicago.

Buddhism is “also extremely empirical in its approach, suggesting that followers try the experiment of dharma (i.e., Buddha’s Four Noble Truths) for themselves to see if it improves their inner freedom,” Asma notes, adding: “Because the philosophy of Buddhism takes this pragmatic approach favoring education and experiment, Buddhism has little to no formal disagreement with science (as evidenced by the Dalai Lama’s ongoing collaboration with neuroscientists).”

This theoretical openness to scientific knowledge, however, did not always play out at the practical level within Buddhist communities, Asma contends. “Powerful Buddhist monasteries, especially in China and Tibet, frequently resisted modernization (including science) for fear of foreign influence and threats to entrenched Buddhist power structures,” he writes. 44

Despite this tension between theory and practice, Buddhism has been a major influence on the educational systems of many places, especially India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and Tibet. From around the fifth century onward, Buddhist monasteries emerged as centers of education, not just for monks but also for laymen. Several monasteries became so large and complex that they are considered prototypes of today’s universities. In India, the most famous of these educational centers – Nalanda, in what is now Bihar state – is said to have had 10,000 students from many different countries, and offered courses in what then constituted philosophy, politics, economics, law, agriculture, astronomy, medicine and literature. 45

For Hindus, education vanquishes a fundamental source of human suffering, which is ignorance, says Anantanand Rambachan, a professor of religion at St. Olaf College. As a result, education has been highly valued in Hinduism since the religion’s inception in ancient times. Hindu scriptures urge adherents to seek knowledge through dialogue and questioning, and to respect their teachers. “Learning is the foundational stage in the Hindu scheme of what constitutes a good and a meaningful life,” Rambachan says. Since ignorance is regarded as a source of human suffering, he adds, “the solution to the problem of ignorance is knowledge or learning.”

The Hindu esteem for education is reflected in different ways. To start with, the most authoritative Hindu scriptures are the Vedas, a word that comes from the Sanskrit root word vd , which means knowledge, Rambachan says.

University of Florida religion professor Vasudha Narayanan says Hindus regard two types of knowledge as necessary and worthwhile. The first, vidya, is everyday knowledge that equips one to earn a decent and dignified life. The second, jnana , is knowledge or wisdom that brings awareness of the divine. This is achieved by reading and meditating on Hindu scriptures.

Historically, the caste system in India was a huge barrier to the spread of mass literacy and education. Formal education was reserved for elite populations. But in the seventh and eighth centuries, the vernacular language of Tamil began to be used for religious devotion in southern India, which led to greater access to all kinds of knowledge for a wider group of people. “That is when you start having men and women of different castes composing poems of praise for God, poems that are still recited in temple liturgy today,” Narayanan says.

Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, both secular and religious education came to be seen by Hindus as a universal right, and it gradually began to be extended to all members of the faith. Still, today, the vast majority of Hindus (98%) live in developing countries – mainly India, Nepal and Bangladesh – that have struggled to raise educational standards in the face of widespread poverty and expanding populations, which helps explain why Hindus have relatively low educational attainment compared with other major religious groups.

High levels of Jewish educational attainment may be rooted in ancient religious norms, according to some recent scholarship. The Torah encourages parents to educate their children. This prescription was not mandatory, however, until the first century.

Sometime around 65 C.E., Jewish high priest Joshua ben Gamla issued a religious decree that every Jewish father should send his young sons to primary school to learn to read in order to study the Torah. A few years later, in the year 70, the Roman army destroyed the Second Temple following a Jewish revolt. Temple rituals had been a pillar of Jewish religious life. To replace them, Jewish religious leaders emphasized the need for studying the Torah in synagogues. They also gave increased importance to the earlier religious decree on educating sons, making it a compulsory religious duty for all Jewish fathers. Over the next few centuries, a formal school system attached to synagogues was established.

These developments signaled “a profound transformation” of Judaism, according to economic historians Maristella Botticini of Bocconi University and Zvi Eckstein of the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya. Judaism became, they write, “a religion whose main norm required every Jewish man to read and to study the Torah in Hebrew and to send his sons from the age of 6 or 7 to primary school or synagogue to learn to do so. … Throughout the first millennium, no people other than the Jews had a norm requiring fathers to educate their sons.” 46

This religious obligation meant that male Jews, to a greater degree than their contemporaries, were literate, which gave them an advantage in commerce and trade. Jewish scholarship was enhanced in the early Middle Ages, beginning in the late sixth century, by the emergence of Talmudic academies of Sura and Pumbedita in what is now Iraq. In the late Middle Ages, centers of Jewish learning, including the study of science and medicine, emerged in what is today northern Spain and southern France.

Until the early 19 th century, however, most education of Jewish boys was primarily religious. That began to change with the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment movement initiated by East and Central European Jews.

This intellectual movement sought to blend secular humanism with the Jewish faith and to encourage openness to secular scholarship among Jews. It revived Hebrew as a language of poetry and literature, which reflected the reformers’ appreciation of their Jewish religious heritage. At the same time, they were strong proponents of reforming Jewish education by including secular subjects, such as European literature and the natural sciences. This educational project often brought the reformists into conflict with more orthodox Jewish religious leaders. 47

Contemporary religious norms and doctrines, including teachings on gender

Scholars also have explored how religions’ cultural norms and doctrines may affect educational attainment by determining which subjects are taught in schools, how much emphasis is placed on religious knowledge versus secular education, and if there is gender parity in educational attainment. 48

There has been considerable research on ways in which religious teachings on gender roles may be linked to women’s educational attainment. Some scholars have noted that from the Reformation onward, Protestant groups encouraged educating women, with effects that still resonate today. “Martin Luther urged each town to have a girls’ school so that girls would learn to read the Gospel, evoking a surge of building girls’ schools in Protestant areas,” write economic professors Sascha O. Becker, of the University of Warwick, and Ludger Woessmann, of the University of Munich. Looking at 1970 data for European countries, the two conclude that countries with higher shares of Protestants were “clearly associated” with greater parity between men and women in years of education. 49

Woodberry and Nunn, experts on missionary activity in sub-Saharan Africa, both highlight the Protestant missionaries’ insistence that girls and women be educated. In the missionaries’ view, “ everyone needed access to ‘God’s word’ – not just elites,” writes Woodberry. “Therefore, everyone needed to read, including women and the poor.” 50

By contrast, cultural and religious norms in Muslim societies often hinder women’s education. Lake Forest College political scientist Fatima Z. Rahman examines how family laws in Muslim-majority countries can affect women’s higher education. She finds that when a country’s family laws closely conform to a strict version of sharia, or Islamic law, the share of women in higher education is smaller. This is not the case when family laws are based on more general Islamic precepts. The stricter laws “impose a limit on physical mobility which is typically required for pursuing higher education or a career,” Rahman concludes. 51 There are signs that this could be changing, however, as women make gains in higher education in some conservative Muslim countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council – including Saudi Arabia.

Some academic studies have probed ways a particular religion’s attitude toward secular knowledge – whether it is seen as a necessity for spiritual growth or as a distraction from achieving personal salvation – can affect the pursuit of formal education. In this regard, sociologists Darren E. Sherkat, of Southern Illinois University Carbondale, and Alfred Darnell, a visiting lecturer at Washington University in St. Louis, find that “fundamentalist beliefs and conservative Protestant affiliation both have significant and substantial negative influences on educational attainment.” Young followers of fundamentalist religious leaders, they add, “will likely limit their educational pursuits.” They suggest that Christians who regard the Bible as inerrant – that is, as the error-free word of God – are less likely to enroll in college preparatory classes and “have significantly lower educational aspirations than other respondents.” 52

While Darnell and Sherkat focus their research on Christians in the United States, their observations about how religious attitudes toward secular knowledge may affect attainment offer possible insights into attainment patterns seen in other religions and other parts of the world.

Some scholars, however, hypothesize that higher levels of religious observance and engagement produce greater educational attainment. They posit that religious involvement enhances an individual’s social capital in the form of family and peer networks, which promote educational success. University of Texas sociologists Chandra Muller and Christopher G. Ellison, in a study of U.S. teenagers, find that there is “a positive influence of religious involvement on several key academic outcomes,” such as obtaining a high school diploma. 53 Similarly, in her study of women raised as conservative Protestants, University of Illinois economics professor Evelyn L. Lehrer observes that those who frequently attended religious services during adolescence completed one more year of schooling than their less observant peers. 54

Strong social capital also is proposed by Paul Burstein, a sociologist at the University of Washington, as a topic needing further research to explain the high educational attainment of Jews. Research focused on the social capital approach, Burstein argues, provides “a framework for showing how Jewish religious beliefs and practices, and the organizations created to sustain them, help Jews acquire skills and resources useful in the pursuit of secular education and economic success.” 55

Burstein argues that previous studies looking at “beliefs or behaviors that are specifically Jewish,” or at Jewish “marginality” – either from traditional Judaism or Western society in general – have not offered complete explanations for Jewish educational success.

While this chapter looks at the impact of religion on education, there are also theories on education’s impact on religion – perhaps most notably, that high educational attainment could potentially lead to a shedding of religious identity. If this is true, one might expect higher percentages of religiously unaffiliated people in parts of the world with high educational attainment. A sidebar in Chapter 3 explores data relating to this question, finding mixed results. 56

The puzzle of sub-Saharan Africa’s attainment gap

As noted earlier in this report , the difference between Christian and Muslim educational attainment in sub-Saharan Africa is among the largest intraregional gaps in the world. The region’s rapid projected population growth – both Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa are expected to double in number by 2050 – suggests that determining the reasons for the attainment gap will only grow in importance. 57

Some scholars suggest that the source of the Christian-Muslim attainment gap is rooted in the location of Christian missionary activity during colonial times. Missionary-built educational facilities were often located in what became heavily Christian areas rather than predominantly Muslim locales. 58 For example, while school establishment was widespread as a result of missionary activity in many regions under British colonial rule, in northern Nigeria, which is now overwhelmingly Muslim, British colonial administrators discouraged missionary activity, including development of missionary schools. Historic differences between colonial policy and missionary activity in northern and southern Nigeria are likely an important factor in the present-day Christian-Muslim education gap in Nigeria. 59

Some Muslims, in any case, feared that missionary schools would attempt to convert their children to Christianity. 60

As a result, Christians gained an educational edge over Muslims that lasted decades. Writes Nunn: “The presence of Christian missionaries, particularly Protestant missionaries, has been shown to be strongly correlated with increased educational attainment and the effects appear to persist for many generations.” 61

In his study of Christian versus Muslim primary school enrollment, Holger Daun, an expert in educational policy at Stockholm University, argues that religion counts as much as economic factors in determining attainment. He finds no definitive explanation for the gap, but posits that one factor may be that religious schools set up by local Islamic leaders are viewed as an alternative to government schools. Some of the Islamic schools follow the curricula of state schools, while others teach only religious subjects. 62

Melina Platas, an assistant professor of political science at New York University-Abu Dhabi, argues that the Christian-Muslim attainment gap, particularly in Muslim-majority areas, is only partly explained by poverty and access to schools. Surveys she conducted in Malawi found that Muslims and Christians express similar demands for formal education and do not perceive a trade-off between religious and formal schooling that would affect educational attainment. 63

She offers two alternative explanations for further research. One, she writes, is that parents with low levels of education are less able to help their children attend and succeed in school “even if they have similar expectations for the economic returns of schooling as more educated parents.” This intergenerational pattern may be stronger in Muslim-majority areas, where many parents have low educational attainment.

Platas suggests that a second possible explanation, particularly for Muslim-majority areas, is that some Muslims may believe that secular government schools are Christian-oriented. As during the colonial period, therefore, they may fear that attending these schools poses a threat to their religious identity and to the practice of their faith. 64

Sociologist Nicolette D. Manglos-Weber of Kansas State University offers a similar insight based on her research in 17 sub-Saharan African countries, finding that “religious identity shapes the odds of completing primary school.”

“At both national and local levels,” she writes, “there is an association between Christian groups and the state, which potentially discourages those of other religions from seeing state-sponsored schools as legitimate.”

As a result, Muslims may not favor state-sponsored schooling for their children to the same degree that Christians do, preferring instead to send them to Islamic religious schools. Muslim participation is even lower in countries that have mandatory teaching of religion in government primary schools, Manglos-Weber adds. She characterizes the perceived lack of legitimacy as a “legacy of the historical links between Christian missionization and the colonial project.” 65

In sum, scholars are still exploring the reasons behind differences in educational attainment between Muslims and Christians in sub-Saharan Africa. The gaps appear to be partly a result of historical developments, especially Christian missionary activity and colonial policy. A host of contemporary economic, social, cultural and religious factors may also play a role.

- Hefner, Robert W. and Muhammad Qasim Zaman, eds. 2007. “Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education.” ↩

- For descriptions of the intellectual climate under early Islam, see Sardar, Ziauddin. 1993. “ Paper, Printing and Compact Disks: The Making and Unmaking of Islamic Culture .” Media, Culture and Society. Also see Ahmad, Imad-ad-Dean. 2006. “Signs in the Heavens: A Muslim Astronomer’s Perspective on Religion and Science.” ↩

- Chaney, Eric. 2016. “ Religion and the Rise and Fall of Islamic Science .” Harvard University working paper. ↩

- For descriptions of this intellectual shift and its consequences, see Sardar, Ziauddin. 1993. “ Paper, Printing and Compact Disks: The Making and Unmaking of Islamic Culture .” Media, Culture and Society. Also see Ahmad, Imad-ad-Dean. 2006. “Signs in the Heavens: A Muslim Astronomer’s Perspective on Religion and Science.” Also see Bulliet, Richard W. 1994. “Islam, the View from the Edge . ” Also see Tibi, Bassam. 1993. “The Worldview of Sunni Arab Fundamentalists: Attitudes Toward Science and Technology.” In Marty, Martin E. and R. Scott Appleby, eds. “Fundamentalisms and Society.” Also see Halstead, J. Mark. 2004. “ An Islamic Concept of Education .” Comparative Education. ↩

- Chaney, Eric. 2016. “ Religion and the Rise and Fall of Islamic Science .” Harvard University working paper. Also see Sardar, Ziauddin. 1993. “ Paper, Printing and Compact Disks: The Making and Unmaking of Islamic Culture .” Media, Culture and Society. Also see Ahmad, Imad-ad-Dean. 2006. “Signs in the Heavens: A Muslim Astronomer’s Perspective on Religion and Science.” ↩

- Hefner, Robert W. and Muhammad Qasim Zaman, eds. 2007. “Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education.” Hefner and Zaman write: “However different their details, the educational transformations in the broader Muslim world all had one thing in common. The ulama’s {religious scholar’s} monopoly on education had been broken once and for all. … The new educational pluralism brought intensified competition between supporters of general as opposed to religious education, and fierce public debate over the place of Islam in an imagined postcolonial community.” ↩

- Saliba, George. 2007. “Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance.” For other scholars who argue that the constrictions on intellectual innovation have been exaggerated by historians, see Hourani, Albert. 1991. “A History of the Arab Peoples.” Also see Hallaq, Wael B. 1984. “ Was the Gate of Ijithad Closed? ” International Journal of Middle East Studies. ↩

- Although Christian Sunday schools are now usually devoted to religious instruction, their roots lie in the British Sunday school movement started in 1780s. Launched by Christian religious leaders, the schools initially were intended to teach literacy to poor children. Their textbook was the Bible. ↩

- In 1633, the Roman Catholic Church’s Inquisition sentenced Galileo to house arrest for the rest of his life and banned his writings after finding him “vehemently suspect of heresy” for contending that the earth revolved around the sun. The church regarded this view – later accepted as scientific fact – as contrary to Holy Scripture. England’s highest-ranking Catholic official, Henry Cardinal Manning, denounced Darwin’s views as “a brutal philosophy – to wit, there is no God, and the ape is our Adam.” Samuel Wilberforce, the Anglican Archbishop of Oxford and one of the most highly respected religious leaders in 19th-century England, also condemned the theory of evolution by natural selection. The defendant in the Scopes Monkey Trial, high school teacher John Scopes, was convicted of violating a Tennessee law banning the teaching of human evolution in government-funded schools. ↩

- Woodberry, Robert D. 2012. “ The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy .” American Political Science Review. Woodberrry’s principal argument is that the Protestant missionaries helped spread democracy in Africa when they prioritized education and literacy as a means of conversion. “(I)n trying to spread their faith, (they) expanded religious liberty, overcame resistance to mass education and printing, fostered civil society, moderated colonial abuses and dissipated elite power,” he writes. “These conditions laid a foundation for democracy.” ↩

- Nunn, Nathan. 2012. “ Gender and Missionary Influence in Colonial Africa .” In Akyeampong, Emmanuel, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn and James A. Robinson. 2014. “Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective.” Also see Nunn, Nathan. 2010. “ Religious Conversion in Colonial Africa .” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 100. ↩

- Woodberry, Robert D. 2012. “ The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy .” American Political Science Review. Also see Nunn, Nathan. 2012. “ Gender and Missionary Influence in Colonial Africa .” In Akyeampong, Emmanuel, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn and James A. Robinson, eds. 2014. “Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective.” ↩

- Meshram, Manish. 2013. “Role of Buddhist Education in Ancient India,” International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature. See also “ Buddhist Attitude to Education .” ↩

- Asma email correspondence with Pew Research Center. Also, Asma, Stephen T. 2010. “Why I am a Buddhist: No-Nonsense Buddhism With Red Meat and Whiskey.” ↩

- Meshram, Manish. 2013. “Role of Buddhist Education in Ancient India,” International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature. ↩

- Botticini, Maristella and Zvi Eckstein. 2012. “The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History, 70-1492.” ↩

- Sachar, Howard M. 2005. “A History of the Jews in the Modern World.” ↩

- Melina Platas, assistant professor of political science at New York University-Abu Dhabi, notes religion’s impact on curricula in her 2016 dissertation, “The Religious Roots of Inequality in Africa”: “The doctrine espoused by religious organizations can serve to increase or decrease the demand for certain types of education or certain skills among their constituents,” she writes. ↩

- Becker, Sascha O. and Wößmann, Ludger. 2008. “ Luther and the Girls: Religious Denomination and the Female Education Gap in 19 th Century Prussia .” Discussion Paper No. 3837. The Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn. ↩

- Rahman, Fatima Z. 2012. “Gender Equality in Muslim-Majority States and Shari’a Family Law: Is There a Link?” Australian Journal of Political Science. ↩

- Darnell, Alfred and Darren E. Sherkat. 1997. “ The Impact of Protestant Fundamentalism on Educational Attainment .” American Sociological Review. A related study by Louisiana State University sociologist Samuel Stroope et. al finds that biblical literalism is “negatively associated with college completion.” See Stroope, Samuel, Aaron B. Franzen and Jeremy E. Uecker. 2015. “ Social Context and College Completion in the United States: The Role of Congregational Biblical Literalism .” Sociological Perspectives. ↩

- Muller, Chandra and Christopher G. Ellison. 2001. “ Religious Involvement, Social Capital, and Adolescents’ Academic Progress: Evidence from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988 .” Sociological Focus. Sociologist Mark D. Regnerus at the University of Texas at Austin finds similar results, writing that youths’ “involvement in church activities has a positive relationship with both educational expectations and math and reading achievement.” He finds that this holds true across income levels. “ Shaping Schooling Success: Religious Socialization in Educational Outcomes in Metropolitan Public Schools .” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. ↩

- Lehrer, Evelyn L. 2004. “ Religiosity as a Determinant of Educational Attainment: The Case of Conservative Protestant Women in the United States .” Review of Economics of the Household. ↩

- Burstein, Paul. 2007. “ Jewish Educational and Economic Success in the United States: A Search for Explanations .” Sociological Perspectives. ↩

- Some studies suggest that religion and education are inversely related. For example, a 2015 study of education’s effect on Turkish women found a reduction in forms of religious expression (as measured by wearing a headscarf, praying regularly, attending Quranic studies and fasting) in women who had more years of schooling. Gulesci, Selim and Erik Meyersson. “ ‘For the Love of the Republic’ Education, Religion and Empowerment .” Working paper. A second study of Canadians in 2011 finds, “An additional year of education leads to a 4-percentage-point decline in the likelihood that an individual identifies with any religious tradition.” The author contends “that increases in schooling could explain most of the large rise in non-affiliation in Canada in recent decades.” Hungerman, Daniel M. 2011. “ The Effect of Education on Religion: Evidence from Compulsory Schooling Laws .” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. However, in Chapter 3 we demonstrate that the relationship between affiliation and education varies by country and that there are more countries in which young affiliated people have more education than there are countries in which young unaffiliated people have the advantage. ↩

- Population estimates are from the 2015 Pew Research Center report “ The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 .” ↩

- Nunn, Nathan. 2010. “ Religious Conversion in Colonial Africa .” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 100. Also see Woodberry, Robert D. 2004. “ The Shadow of Empire: Christian Missions, Colonial Policy, and Democracy in Postcolonial Societies .” ↩

- For discussion, see Frankema, Ewout H.P. 2012 “The origins of formal education in sub-Saharan Africa: was British rule more benign?” European Review of Economic History. Also see Thurston, Alex. 2016. “Colonial Control, Nigerian Agency, Arab Outreach, and Islamic Education in Northern Nigeria, 1900-1966” in Launay, Robert, ed. “Islamic Education in Africa: Writing Boards and Blackboards.” Also see Melina Platas. 2016. “The Religious Roots of Inequality in Africa.” Dissertation. ↩

- See Moore, Leslie C. 2006. “Learning by Heart in Qur’anic and Public Schools in Northern Cameroon.” Social Analysis. Moore writes of Cameroon: “Public schooling is believed by many Muslims to interfere with the social, moral, and spiritual development of their children. Time spent in public school is time not spent in Qur’anic study and in learning tasks and responsibilities from one’s father or mother. Moreover, parents are concerned that their children do not learn much of any use at school, and that much of what they do learn — nasaaraaji (things of the whites) — is counter to the norms of Islam and Fulbe culture.” ↩

- Nunn, Nathan. 2014. “ Gender and Missionary Influence in Colonial Africa .” In Akyeampong, Emmanuel, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn and James A. Robinson. 2014. “Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective.” Melina Platas also writes in her 2016 dissertation, “ The Religious Roots of Inequality in Africa ”: “Seeking to avoid unrest that may have come from proselytization among Muslim populations, colonial administrators were not only more likely to prevent missionaries from establishing churches but also Christian-founded schools and health facilities in areas with Islamized political institutions as compared to those without.” At the same time, Platas finds some evidence for a contradictory trend: That Muslim-run schools increased when missionary-built schools appeared in or close to Muslim-majority areas. “There is some evidence,” she writes, “that Muslims responded to missionary investments by building their own schools, but these remained relatively few in number throughout the colonial period.” ↩

- Daun, Holger. 2000. “ Primary Education in sub-Saharan Africa – a moral issue, an economic matter, or both? ” Comparative Education. ↩

- Some studies, however, suggest that many Muslim parents prefer their daughters attend traditional Islamic schools, because they preserve traditional female roles and may preserve religious values (See Ogunjuyigbe, Peter O. and Adebayo O. Fadeyi. 2002. “Problems of Gender Differentials in Literacy and Enrolment Among the Yorubas of South- West Nigeria.” Journal of Social Sciences. Indeed, a 2010 study of women in three villages in Nigeria finds that a Quranic education is more common than other types of school among young Muslim women. See Adiri, Farouk, Habiba Ismail Ibrahim, Victor Ajayi, Hajaratu Umar Sulayman, Anita Mfuh Yafeh and Clara L. Ejembi. 2010. “Fertility Behaviour of Men and Women in Three Communities in Kaduna State, Nigeria.” African Journal of Reproductive Health. ↩

- Platas, Melina. 2016. “The Religious Roots of Inequality in Africa.” Dissertation. The perception of government schools with Western-style curricula being seen as a tool for conversion of Muslim students also is discussed in Csapo, Marg. 1981. “Religious, Social and Economic Factors Hindering the Education of Girls in Northern Nigeria.” Comparative Education. ↩

- Manglos-Weber, Nicolette. 2016. “Identity, Inequality and Legitimacy: Religious Differences in Primary School Completion in sub-Saharan Africa.” Forthcoming in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Religion & Politics

How people in South and Southeast Asia view religious diversity and pluralism

Religion among asian americans, in their own words: cultural connections to religion among asian americans, in singapore, religious diversity and tolerance go hand in hand, 6 facts about buddhism in china, most popular, report materials.

- Appendix C: Mean years of schooling by country, religion and gender

- How Religious Groups Differ in Educational Attainment

- Estimates of Education by Religious Group data spreadsheets

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

New document on Catholic Education: identity and challenges

By Isabella Piro

The underlying principle of the new “Instruction” issued by the Congregation for Catholic Education is that educating is a passion that is always renewed. The document released today by the Congregation is entitled "The Identity of Catholic Schools for a Culture of Dialogue". It is a concise and practical tool based on two motivations: "the need for a clearer awareness and consistency of the Catholic identity of the Church's educational institutions throughout the world," and the prevention of "conflicts and divisions in the essential sector of education". The document falls within the goals of the Global Compact on Educational, desired by Pope Francis, so that the Church may remain strong and united in the field of education, and thus carry out its evangelizing mission and contribute to the construction of a more fraternal world.

The Church is mother and teacher

In particular, the Instruction highlights that the Church is "mother and teacher": its educational action, therefore, is not "philanthropic work", but an essential part of its mission, based on fundamental principles, first and foremost the universal right to education. The other principles that are developed are: the responsibility of everyone - first of all of the parents, who have the right to make educational choices for their children in full freedom and according to conscience, and of the State which has the duty to make different educational options available within the framework of the law – and within these, the Church’s basic principle for education in which evangelization and integral human promotion are intertwined. Also considered is the formation of teachers, so that they may be witnesses of Christ; collaboration between parents and teachers and between Catholic and non-Catholic schools; the concept of Catholic schools as "communities" permeated by the evangelical spirit of freedom and charity, thus providing formation and promoting solidarity. In a multicultural world, we are also reminded of "a positive and prudent sex education," a not insignificant element that students must receive as they grow up.

The culture of care

Catholic schools, the document highlights, also have the task of educating for a "culture of care," in order to convey those values based on the recognition of the dignity of every person, community, language, ethnicity, religion, peoples, and all the fundamental rights that derive from it. A culture of care is precious "compass" for society, forming people dedicated to listening, constructive dialogue and mutual understanding.

In constant dialogue with the community

In constant dialogue with the entire community, Catholic educational institutions must not be a closed model, in which there is no room for those who are not "totally" Catholic. Warning against this attitude, the Instruction recalls the model of an "outgoing Church": "We must not lose the missionary impulse to close ourselves in an island - the document reads - and at the same time we need the courage to witness to a Catholic "culture" that is universal, cultivating a healthy awareness of our own Christian identity".

Clear qualifications and legislation

Another focal point of the document is the need for clarity of competencies and legislation: it can happen, in fact, that the State imposes on Catholic public institutions "behaviors that are not in keeping" with the doctrinal and disciplinary credibility of the Church, or choices that are in contrast with religious freedom and with the very Catholic identity of a school. In such cases, it is recommended that "reasonable action be taken to defend the rights of Catholics and their schools, both through dialogue with state authorities and through recourse to the competent courts."

To educate is always an act of hope

The Instruction concludes by emphasizing that Catholic schools "constitute a very valid contribution to the evangelization of culture, even in countries and cities where an adverse situation stimulates the use of creativity to find adequate paths," because, as Pope Francis says, "to educate is always an act of hope."

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here

Why Fewer People Are Religious Today: 19 Simple Reasons

Posted: May 27, 2024 | Last updated: May 27, 2024

Religion, in one form or another, has been a part of the human experience since mankind first questioned the world's origins, their roles in life, and the concept of an afterlife. Since then, it has shaped our societies, morals, and lifestyles. Yet recent trends indicate a decline in religious affiliation worldwide. Here's a deeper look at 19 factors contributing to this phenomenon.

Modern Family Structure

The traditional multi-generational household is becoming less common, meaning that older, more religious generations are less likely to pass their traditions and beliefs onto their children and grandchildren. Single-parent homes, blended families, and older parents are all more common, and children in these homes tend to attend fewer religious services and rituals.

Increased Secularization

Church and state have become entirely separate in most progressive countries, and this has contributed to secularization, the waning power and influence of religion over people's daily lives. The Guardian states that this has been happening in the U.K. since World War II, and "the number of people identifying as Christian has fallen from 66% to 38% over the same period."

Scientific Progress

One reason people turn to religion is to answer life's 'mysteries' with divine answers or mystical explanations. However, as scientific experimentation and research provide reliable, proven answers to questions about our universe, our place in it, and human biology, religion has become outdated, irrelevant, and unnecessary.

Individualism

Modern Westernized societies tend to emphasize individual rights, self-expression, and personal fulfillment. This can sometimes clash with religious doctrines that demand conformity and obedience to a set of beliefs or a higher power. Younger individuals, in particular, may feel that faith and organized religion don't value their personal identity enough.

Broader Worldview

One reason religion dominated ancient civilizations is that most people couldn't travel and were forced to accept the 'word' of God or a certain faith because they had no chance to gain alternative perspectives. As the internet and travel have made the world more open and accessible, this has changed, making people more open-minded and globally aware.

Social Media

Social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter provide a way for those questioning religious authority to share alternative viewpoints and discuss alternative ways of thinking. Skeptics can easily find communities that challenge traditional beliefs, no matter where they live, while religious institutions struggle to maintain their control over the flow of such information.

Social Morality

Concepts of right and wrong are increasingly seen as social constructs rather than rules dictated by religious teachings. Carleton Newsroom asserts that many things in the Bible (like homophobia and sexism) are unacceptable to modern Christians because they don't fit modern ideas about equality and tolerance. Over time, this erodes people's faith in religion as a whole.

Perceived Hypocrisy

Newsworthy events like religious scandals and financial dishonesty by religious leaders or within religious organizations can severely damage trust in religion and cause disillusionment. When the actions of religious figures contradict their teachings, it can cause followers to question the entire system and ask difficult questions that the Church often fails to answer convincingly.

Materialism

Spirituality and faith can be overshadowed by modern consumerism and the pursuit of material success, like home and car ownership. Young people are constantly bombarded with messages that insist their happiness depends on a specific purchase or lifestyle. When people focus on making money and acquiring things, religion can become less relevant in their daily lives.

Urbanization

The shift towards urban living can weaken religious communities, which tend to be most powerful and controlling in close-knit rural communities that share worship and other religious practices. In the fast-paced, anonymous city, a strong sense of belonging isn't easy to find, and people may also feel free to pursue 'immoral' or non-religious pursuits without judgment.

Delayed Settling Down

As we live longer and enjoy improved health beyond middle age, people are generally delaying marriage, having children, and settling down. This shift in early priorities makes religion less influential because younger generations move around more, experience alternative lifestyles, and are generally less susceptible to being indoctrinated by religious communities.

Emphasis on Choice

Science Direct writes, "Many religions promote restrictions on personal liberties such as divorce, abortion, gender parity, or gay marriage." This can lead people to question the faith they were raised in and explore alternative paths that allow for greater independence from religious teachings and more freedom to live in the way they choose.

Decline of Religious Education

In some countries, religious education in schools is becoming less common or has even been entirely removed from the curriculum. This can lead to younger generations having less exposure to religious teachings, rituals, and traditions, which can make them more open-minded and less likely to blindly follow a faith-based lifestyle.

Geographic Mobility

Being able to move around freely makes it difficult for religious communities to gain deeply ingrained support, particularly if they are isolated or extreme. Without a faithful social circle, individuals might struggle to maintain their faith or fulfill specific requirements for prayer or worship. This can lead to alternative lifestyles and new ways of thinking.

Reason and Logic

As people have improved access to education and shared knowledge, their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities have improved, which often leads to religious skepticism. When intelligent people question religious tenets or long-held beliefs, they are often met with blanket denial or unsatisfactory explanations, causing many to abandon their faith because of logic and reason.

Personal Spirituality

Being spiritual doesn't necessarily mean being religious. Whole Person maintains that being spiritual means feeling connected to oneself, mankind, ancestors, and nature, and it can be achieved through whatever method feels meaningful to you, including prayer, meditation, seeing nature, tarot cards, etc. Many people prefer this less restrictive form of spiritual connection.

Mistrust of Authority

A general distrust of authority figures, including politicians, CEOs, and religious leaders, is on the rise. Social media and other news outlets expose scandals and hypocrisy, leading people to question the motives and pronouncements of those in power, including religious institutions. This skepticism can make individuals more rebellious and increasingly likely to reject religion in general.

Alternative Ways to Help

Many secular organizations are now addressing social issues that used to be traditionally assisted by religious groups. Activities like volunteering, campaigning for social justice, and providing social support or a sense of community are all undertaken by organizations and charities without religious affiliation, giving people an alternative way to 'give back' and feel worthwhile.

Changing Definitions

The very definition of "religion" is evolving. Traditional, structured religious institutions are becoming less relevant, while individual interpretations of spirituality are gaining acceptance. People might claim to have their own sense of 'religion' due to personal spiritual practices and morals that they choose and adhere to on their own terms.

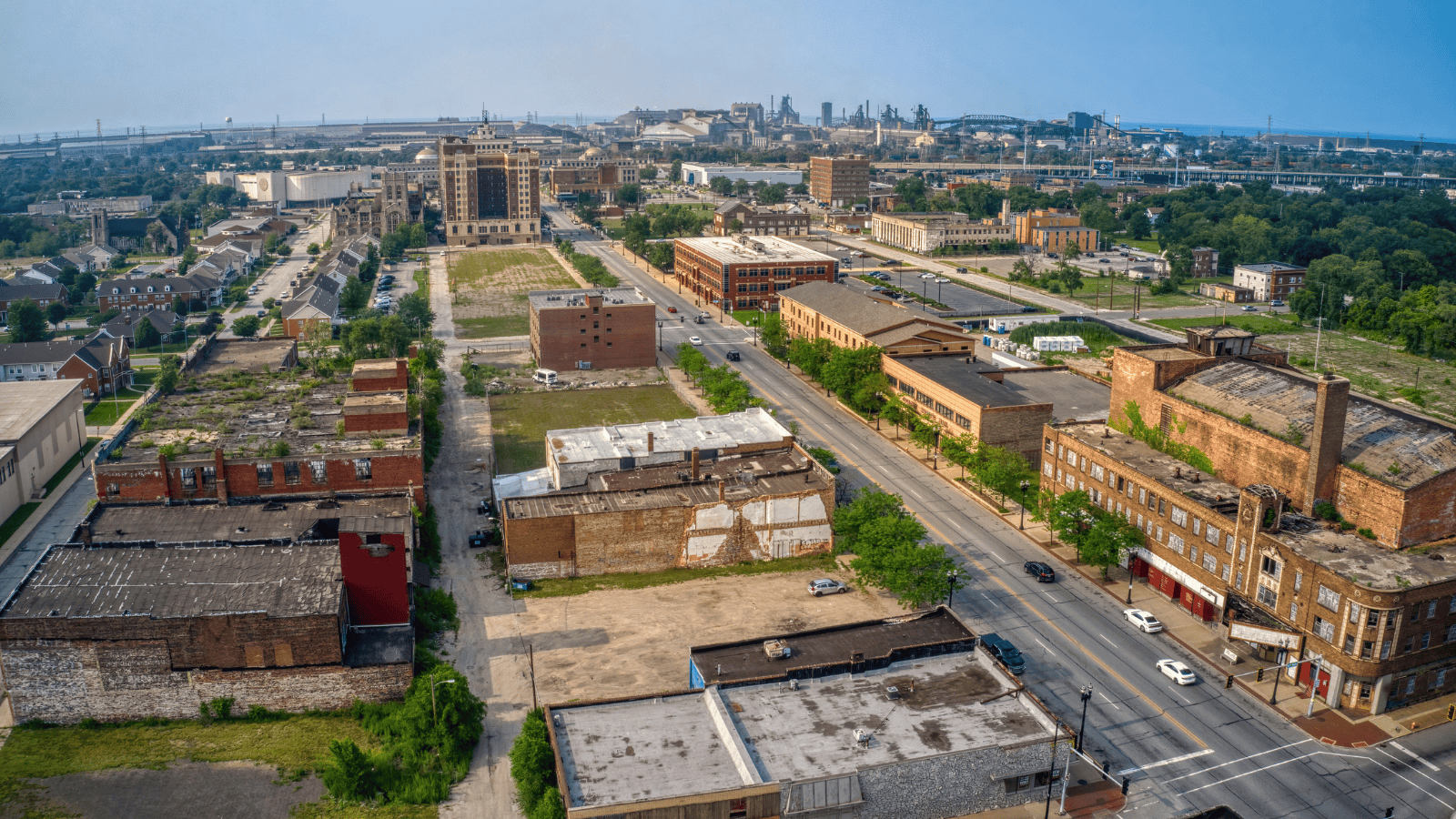

Up Next: 17 Places in the U.S. Where Even Truck Drivers Won’t Stop

Truck drivers tend to be hardy souls—well-seasoned travelers who aren't often afraid to rest up or refuel in risky locations. However, there are certain U.S. locations that even the most road-weary trucker refuses to stop at for fear of criminal activity or natural dangers. Here are 17 such locations that even experienced truck drivers approach with trepidation (or not at all).

17 PLACES IN THE U.S. WHERE EVEN TRUCK DRIVERS WON’T STOP

17 Things Guests Actually Notice Right Away About Your House

Inviting people into your home is a big deal. You may be very house-proud or house-conscious, and if you are either, you’ll likely get anxious about hosting. If this sounds like you, stop worrying and focus on the following 17 things that guests actually notice right away about your house.

17 THINGS GUESTS ACTUALLY NOTICE RIGHT AWAY ABOUT YOUR HOUSE

The 17 Unhappiest States in America

The US has hit an all-time low position in the World Happiness Index, tumbling to 23rd in 2024. However, it’s important to remember that location is an important factor; many US states are very happy, unlike the following 17 US states that appear to be the most unhappy.

THE 17 UNHAPPIEST STATES IN AMERICA

More for You

20 Hollywood Stars Who Disappeared from Sight

18 Things That Will Happen if 70 Becomes the New Retirement Age in the US

"The First Time I Visited The US I Thought This Was A Restaurant Scam": Non-Americans Are Sharing The Things That Are Totally Common In The US But Bizarre In Other Countries

"It did have an effect on my kidney function" – Alonzo Mourning shares how painkillers nearly ended his career

The Best Pizza in Every State

Mechanic shares photo of unexpected object that punctured vehicle's tire: 'This will be increasingly common'

NBA Fans Outraged After Blatant Dirty Foul By Jaylen Brown

Judge's Jury Instructions Could Change Trump Trial Outcome: Jury Consultant

Are you ready for your first year of retirement? Here are 4 things you might not expect — but definitely need to prepare for

Reports: Umpire Ángel Hernández, after long and controversial run in Major League Baseball, set to retire

“I cried unmercifully for like an hour” - Charles Barkley vowed to get back at Ms. Gomez for making him miss the graduation ceremony

20 Best Sandwiches in America You Need to Try At Least Once

WNBA Legend Sue Bird Makes a Clear Demand of Caitlin Clark

5 Bad Habits To Avoid For Extending The Life Of Your Car's CVT Transmission

The High-Speed X-Plane That Could Revolutionize Warfare

‘The decision I needed to make’: Kevin Costner took out a mortgage on seaside Santa Barbara estate to fund epic western project, sending accountant into a ‘conniption fit’

Cyclist shares frustrating video of driver not paying attention while violating bike lane rules: 'You'd think people would be more aware'

How to Tell If Your Phone Is Tapped: 7 Warning Signs

New ‘Protected Intersection’ Design Looks Awful, But Actually Makes Sense

Carnival and Royal Caribbean make huge new casino deals

Problems of religious literacy in Indonesian education

- Published: 17 May 2024

Cite this article

- Bagong Suyanto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2634-048X 1 ,

- Mun’im Sirry 2 na1 ,

- Rahma Sugihartati 1 na1 ,

- Drajat Tri Kartono 3 na1 &

- Muhammad Turhan Yani 4 na1

This article explores three questions: What is the perception of teachers concerning religious literacy? Is religious literacy an appropriate framework to combat religious intolerance? Do school teachers, principals, and policy makers support interreligious initiatives, including teaching the religions of the world and interreligious site visits? To answer these questions, we conducted interviews with 97 teachers from 24 high schools in four cities (Batu, Jember, Lamongan, and Nganjuk) in East Java. We also invited high school principals, teachers, and representatives from the Office of Education in the city of Surabaya to share their perspectives at our Focus Group Discussion (FGD). This article documents and analyzes teachers’ voices cautioning against teaching students about other religions as well as counter-voices encouraging religious literacy. The findings of this study will have an important implication for thinking creatively about various approaches to religious literacy and possible reform of teacher education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Challenges of Religious Literacy in Education: Islam and the Governance of Religious Diversity in Multi-faith Schools

School Religious Education in the Classroom: A Reading from the Catholic and Colombian Context

Religious Fundamentalism as a Challenge for (Inter-)religious Education

“Pancasila” is the official ideology of the Indonesian state. The word means “five principles,” namely, monotheism, humanitarianism, unity, democracy, and justice.

Ali, N., Afwadzi, B., Abdullah, I., & Mukmin, M. I. (2019). Interreligious literacy learning as a counter-radicalization method: A new trend among institutions of Islamic higher education in Indonesia. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, 32 (4), 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2021.1996978

Article Google Scholar

Ashraf, M. A. (2019). Exploring the potential of religious literary in Pakistani education. Religions, 10 (424), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070429

Badan Pusat Statistik (2019/2020). Jumlah Sekolah, Guru, dan Murid Madrasah Aliyah (MA) di Bawah Kementerian Agama Menurut Provinsi, 2019/2020. https://www.bps.go.id/indikator/indikator/view_data_pub/0000/api_pub/80/da_04/1BPS

Bramadat, P., & Seljak, D. (Eds.). (2009). Religion and ethnicity in Canada . University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442686137

Book Google Scholar

Brömssen, K., Ivkovits, H., & Nixon, G. (2020). Religious literacy in the curriculum in compulsory education in Austria, Scotland and Sweden: A three-country policy comparison. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 41 (2), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2020.1737909

Burritt, A. M., & Massam, K. T. (2020). Interreligious dialogue, literacy and theologies of storytelling: Australian perspectives. Teaching Theology and Religion, 23 (4), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/teth.12554

Byrne, C. (2014). Religions education, social inclusion and interreligious literacy in England and Australia. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 27 (2), 153–177. https://doi.org/10.1558/jasr.v27i2.153

Cronshaw, D. (2021). Finding common ground: Grassroots dialogue principles for interreligious learning at university. Journal of Religious Education, 69( 1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-020-00128-0

De Lissovoy, V. (1954). A sociological approach to religious literacy. The Journal of Educational Sociology, 27 (9), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.2307/2264041

Dinham, A., Arat, A., & Shaw, M. (2021). Religion and Belief Literacy: Reconnecting a Chain of Learning . Bristol University Press.

Google Scholar

Enstedt, D. (2022). A response to Wolfart’s ‘Religious Literacy’: some considerations and reservations. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 34 , 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-bja10079

Francis, M., & Dinham, A. (2015). Religious Literacies: The Future. In A. Dinham & M. Francis (Eds.), Religious literacy in policy and practice (pp. 257–270). Bristol University Press.

Fujiwara, S. (2010). On qualifying religious literacy: Recent debates on higher education and religious studies in Japan. Teaching Theology and Religion, 13 (3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9647.2010.00615.x

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1999). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

Halafoff, A., Singleton, A., Bouma, G., & Rasmussen, M. (2020). Religious literacy of Australia’s Gen Z teens: Diversity and social inclusion. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 41 (2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2019.1698862

Handayani, L.S. (2018). Jumlah Madrasah Negeri Masih Minim. Republika, September 14, 2018. https://republika.co.id/berita/pf10gi366/jumlah-madrasah-nesgeri-masih-minim

Hannam, P., Biesta, G., Whittle, S., & Aldridge, D. (2020). Religious literacy: A way forward for religious education. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 41 (2), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2020.1736969

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counselling research designs. Journal of Counselling and Development, 89 (3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Kujawa-Holbrook, S. A. (2015). Interreligious learning. Religious Education, 110 (5), 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344087.2015.1089715

Lester, E. (2008). World religions in modesto: findings from a curricular innovation. Religion and Education, 35 (1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2008.10012412

Lester, E., & Roberts, P. (2009). How to teach world religions brought a truce to the culture wars in Modesto, California. British Journal of Religious Education, 31 (3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200903112219

Long, J. D. (2018). Site visits in interfaith and religious studies pedagogy: Reflections on visiting a Hindu temple in Central Pennsylvania. Teaching Theology and Religions, 21 (2), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/teth.12427

Moore, D.L. (2006). Overcoming Religious Illiteracy: A Cultural Studies Approach. World History Connected (November): https://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/4.1/moore.html

Moore, D. L. (2007). Overcoming religious illiteracy: A cultural studies approach to the study of religion . Palgrave MacMillan.

Moore, D. L. (2015). Diminishing religious literacy: Methodological assumptions and analytical frameworks for promoting the public understanding of religion. In A. Dinham & M. Francis (Eds.), Religious literacy in policy and practice (pp. 27–38). Bristol University Press.

Mosher, L. (2022). What is interreligious studies. In L. Mosher (Ed.), The georgetown companion to interreligious studies (pp. 3–14). Georgetown University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Parker, L., & Raihani, R. (2011). Democratizing Indonesia through education? Community participation in Islamic schooling. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39 (6), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211416389

Pew Research (2010). US Religious Knowledge Survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research, Religion & Public Life. www.pewforum.org/2010/09/29/u-s-religious-knowledge-survey

Prothero, S. (2007). Religious Literacy: What every American needs to know—and doesn’t . Harper Collins.

Prothero, S., & Kerby, L. (2015). The irony of religious illiteracy in the USA. In A. Dinham & M. Francis (Eds.), Religious literacy in policy and practice (pp. 55–75). Bristol University Press.

Purwadi, A., & Muljoatmodjo, S. (2000). Education in Indonesia: Coping with challenges in the third millennium. Journal of Southeast Asian Education, 1 (1), 79–102.

Sanders, J., Foyil, K., & Graff, J. M. (2010). Conveying a stance of religious pluralism in children’s literature. Children’s Literature in Education, 41 , 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-010-9102-3

Saputra, R. E. (2018). Api Dalam Sekam: Keberagamaan Generasi Z . Jakarta: Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat.

Sirry, M. (2024). Youth, education, and Islamic radicalism: Religious intolerance in contemporary Indonesia . University of Notre Dame Press.

Sofjan, D. (2020). Learning about religions: An Indonesian religious literacy program as a multifaith site for mutual learning. Religions, 11 (433), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090433

Soules, K. E., & Jafralie, S. (2021). Religious literacy in teacher education. Religion & Education, 48 (1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2021.1876497

Subedi, B. (2006). Preservice teachers’ beliefs and practices: Religion and religious diversity. Equity & Excellence in Education, 39 (3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680600788495

Syafruddin, D., Darmadi, D., Umam, S., & Ropi, I. (Eds.). (2018). Potret Guru Agama: Pandangan tentang Toleransi dan Isu-Isu Kehidupan Keagamaan . Jakarta: Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat.

Wahid, A. (1999). Pondok Pesantren Masa Depan . Bandung: Pustaka Hidyah.

Ward, L. (1953). The right to religious literacy. Religious Education, 48 (6), 380–383.

Wolfart, J. C. (2022). ‘Religious literacy’: Some considerations and reservations. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 34 , 407–434. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-bja10074

Wright, A. (1993). Religious education in the secondary school: Prospects for religious literacy . David Fulton Publishers.

Young, R. F. (2009). Interreligious literacy and hermeneutical responsibility. Theology Today, 66 , 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/004057360906600305

Zuhdi, M. (2022). Promoting religious literacy through education in the multi-culture Indonesia. Journal of Public Values, 4 , 37–41.

Zuhdi, M., & Sarwenda, S. (2020). Recurring issues in Indonesia’s Islamic education: The needs for religious literacy. Analisa: Journal of Social Science and Religion, 5 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v5i1.1038

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Indonesian Directorate General of Higher Education for its generous support. This research is part of the International Research Collaboration, 2023.

Funding was provided by Direktorat Riset Dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat

Author information

Mun’im Sirry, Rahma Sugihartati, Drajat Tri Kartono, and Muhammad Turhan Yani contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Airlangga University, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

Bagong Suyanto & Rahma Sugihartati

Department of Theology, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 46656, USA

Mun’im Sirry

Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Sebelas Maret University, Solo, Indonesia

Drajat Tri Kartono

Faculty of Social Scienses and Law, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia

Muhammad Turhan Yani

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bagong Suyanto .

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement.

This study was conducted in compliance with the standards of ethical research established by the University of Airlangga in Surabaya.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Suyanto, B., Sirry, M., Sugihartati, R. et al. Problems of religious literacy in Indonesian education. j. relig. educ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-024-00228-1

Download citation

Accepted : 15 April 2024

Published : 17 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-024-00228-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Religious literacy

- Interreligious learning

- High school

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Contemporary Challenges for Religious and Spiritual Education, edited by Arniika Kuusisto and Terence Lovat, is an academic book through and through.This text had originally been printed as the August 2014 special issue of the Journal of Beliefs & Values.At the beginning of the book, packaged as Contemporary Challenges for Religious and Spiritual Education, the editors note that they believe ...

About this report. This analysis, updated on Oct. 3, 2019, was originally published in 2007 as part of a larger series that explored different aspects of the complex and fluid relationship between government and religion. This report includes sections on school prayer, the pledge of allegiance, religion in school curricula, and the religious liberty rights of students and teachers.

About this book. This book brings together new thinking and research on religious education's complex and evolving role in the multicultural, diverse postmodern era. It facilitates new realism and understanding of the current situation from empirical and reflective accounts relating to a variety of countries and political contexts, as well as ...

need for religious education courses in schools and the challenges that come along with religious education is one that other countries are also engaging in. There is expanding research on teachers' perspectives of the validity and challenges of religious education in the UK, Sweden, Norway, Australia and Germany, where such courses are ...