Search the world's largest collection of clinical case reports

Browse case reports by:

Publish in BMJ Case Reports

Global health case reports.

These are case reports that focus on the causes of ill health, the social determinants of health and access to healthcare services, prevailing local and national issues that affect health and wellbeing, and the challenges in providing care to vulnerable populations or with limited resources.

Read the full collection now

Images in… :

31 July 2023

Unusual association of diseases/symptoms :

24 January 2024

14 July 2023

Obstetrics and gynaecology :

5 March 2024

Case report :

18 October 2023

Case Reports: Rare disease :

Case Reports by specialty

- Anaesthesia

- Dentistry and oral medicine

- Dermatology

- Emergency medicine

- Endocrinology

- General practice and family medicine

- Geriatric medicine

- Haematology

- Infectious diseases

- Obstetrics and gynaecology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Paediatrics

- Respiratory medicine

- Rheumatology

Global Health Competition

Every year BMJ Case Reports selects authors of global health case reports to join our editorial team as a global health associate editor.

This is an opportunity to gain some editorial experience or join our team on research and educational projects. Students and graduates may apply.

Simply select Global Health Competition when you submit.

Latest Articles

Case Reports: Findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease :

26 June 2024

20 June 2024

Journal of Medical Case Reports

In the era of evidence-based practice, we need practice-based evidence. The basis of this evidence is the detailed information from the case reports of individual people which informs both our clinical research and our daily clinical care. Each case report published in this journal adds valuable new information to our medical knowledge. Prof Michael Kidd AO, Editor-in- Chief

Join the Editorial Board

We are recruiting Associate Editors to join our Editorial Board. Learn more about the role and how to apply here !

- Meet the Editors

Get to know the Editors behind Journal of Medical Case Reports !

megaflopp / Getty Images / iStock

Requirements for case reports submitted to JMCR

• Patient ethnicity must be included in the Abstract under the Case Presentation section.

• Consent for publication is a mandatory journal requirement for all case reports . Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from the patient (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 18, or from the next of kin if the patient has died). For more information, please see our editorial policies .

Report of the Month

Superior mesenteric vein thrombosis due to covid-19 vaccination.

Vaccines have made a significant contribute to sowing the spread of the COVID-19 infection. However, side effects of the vaccination are beginning to appear, and one of which, thrombosis, is a particular problem as it can cuase serious complications. While cases of splanchnic venous thrombosis (SVT) after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccinations have been reported, cases of SVT mRNA-1273 vaccines are rare.

In this case report, clinicians describe a patient presenting with superior mesentric vein thrombosis following a COVID-19 vaccination, and examine the relationship between the mRNA-1273 vaccines and intestinal ischemia.

- Most accessed

Hepatitis A virus infection associated with bilateral pleural effusion, ascites, and acalculous cholecystitis in childhood: a case report

Authors: Fatima Breim, Bakri Roumi Jamal, Lama Kanaa, Saleh Bourghol, Besher Jazmati and Samia Dadah

Hemothorax caused by injury of musculophrenic artery after ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy: a case report

Authors: Jing-ru Yang, Sai Wu, Jian Li, Xiao-juan Tian, Zhuo-xi Xue and Xiao-yan Niu

Double vertical interrupted suture for optimal adaptation and stabilization of free gingival graft around dental implants: a case report

Authors: Neda Moslemi, Amirmohammad Dolatabadi, Seyedhossein Mohseni Salehimonfared and Fatemeh Goudarzimoghaddam

Mucinous cystadenoma and carcinoid tumor arising from an ovarian mature cystic teratoma in a 60 year-old patient: a case report

Authors: Amir Masoud Jafari-Nozad, Najmeh Jahani and Yoones Moniri

Bronchobiliary fistula after traumatic liver rupture: a case report

Authors: Teng Zhou, Wenming Wu, Chao Cheng, Hui Wang, Xiaochuan Hu and Zhenhui Jiang

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

An itchy erythematous papular skin rash as a possible early sign of COVID-19: a case report

Authors: Alice Serafini, Peter Konstantin Kurotschka, Mariabeatrice Bertolani and Silvia Riccomi

Red ear syndrome precipitated by a dietary trigger: a case report

Authors: Chung Chi Chan and Susmita Ghosh

How to choose the best journal for your case report

Authors: Richard A. Rison, Jennifer Kelly Shepphird and Michael R. Kidd

The Erratum to this article has been published in Journal of Medical Case Reports 2017 11 :287

COVID-19 with repeated positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR and then negative test results twice during intensive care: a case report

Authors: Masafumi Kanamoto, Masaru Tobe, Tomonori Takazawa and Shigeru Saito

Recurrent knee arthritis diagnosed as juvenile idiopathic arthritis with a 10-year asymptomatic period after arthroscopic synovectomy: a case report

Authors: Atsushi Teramoto, Kota Watanabe, Yuichiro Kii, Miki Kudo, Hidenori Otsubo, Takuro Wada and Toshihiko Yamashita

Most accessed articles RSS

A Guide to Writing and Using Case Reports

This thematic series, published in 2016, provides a valuable resource for clinicians who are considered producing a case report. It comprises of a special editorial series of guides on writing, reviewing and using case reports.

Aims and scope

Journal of Medical Case Reports will consider any original case report that expands the field of general medical knowledge, and original research relating to case reports.

Case reports should show one of the following:

- Unreported or unusual side effects or adverse interactions involving medications

- Unexpected or unusual presentations of a disease

- New associations or variations in disease processes

- Presentations, diagnoses and/or management of new and emerging diseases

- An unexpected association between diseases or symptoms

- An unexpected event in the course of observing or treating a patient

- Findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect

Suitable research articles include but are not limited to: N of 1 trials, meta-analyses of published case reports, research addressing the use of case reports and the prevalence or importance of case reporting in the medical literature and retrospective studies that include case-specific information (age, sex and ethnicity) for all patients.

Article accesses

Throughout 2022, articles were accessed from the journal website more than 4.17 million times; an average of over 11 ,400 accesses per day.

Latest Tweets

Your browser needs to have JavaScript enabled to view this timeline

Peer Review Mentoring Scheme

The Editors at Journal of Medical Case Reports endorse peer review mentoring of early career researchers.

If you are a senior researcher or professor and supervise an early career researcher with the appropriate expertise, we invite you to co-write and mentor them through the peer review process. Find out how to express your interest in the scheme here .

Call for Papers

The Journal of Medical Case Reports is calling for submissions to our Collection on COVID-19 – a look at the past, present and future of the pandemic . Guest Edited by Dr. Jean Karl Soler, The Family Practice Malta, Malta

About the Editor-in-Chief

Professor Michael Kidd AO FAHMS is foundation Director of the Centre for Future Health Systems at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, and Professor of Global Primary Care and Future Health Systems with the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Prof Kidd was the Deputy Chief Medical Officer and Principal Medical Advisor with the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, and Professor of Primary Care Reform at the Australian National University. He holds honorary appointments with the University of Toronto, the University of Melbourne, Flinders University, and the Murdoch Children's Research Institute, and is the Emeritus Director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre on Family Medicine and Primary Care. He is an elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences (FAHMS). In the 2023 King's Birthday Honours List he was made an Officer of the Order of Australia. Prof Kidd served as president of the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) from 2013-2016, and as president of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners from 2002-2006. He is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Medical Case Reports, the world's first PubMed-listed journal devoted to publishing case reports from all medical disciplines.

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 1.0 - 2-year Impact Factor 0.628 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 0.284 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 33 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 148 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 4,048,208 downloads 2,745 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

- Follow us on Twitter

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Clinical Cases

Litfl clinical cases database.

The LITFL Clinical Case Collection includes over 250 Q&A style clinical cases to assist ‘ Just-in-Time Learning ‘ and ‘ Life-Long Learning ‘. Cases are categorized by specialty and can be interrogated by keyword from the Clinical Case searchable database.

Search by keywords; disease process; condition; eponym or clinical features…

| Topic | Title | Keywords | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECG | ||||||

| ECG | WCT, ECG, Broad complex, fascicular, RVOT | |||||

| Toxicology | valproate, valproic acid, hyperammonemia | |||||

| Toxicology | valproate, valproic acid, hyperammonemia | |||||

| Toxicology | ||||||

| Metabolic | priapsim, intracavernosal, cavernosal gas, Ischaemic priapism, stuttering priapism, urology | |||||

| Metabolic | RTA, strong ion difference, hypocalcaemia | |||||

| Bone and Joint | DRUJ, dislcoation | |||||

| ICE | wellens, ECG, cardiac, delay | |||||

| ICE | SJS, stevens-johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, rash | |||||

| ICE | pneumothorax | |||||

| ICE | ||||||

| ICE | tibia, fracture, toddler, toddler's fracture | |||||

| ICE | ECG, EKG, hyperkalaemia, hyperkalemia | |||||

| ICE | dengue, returned traveler, traveller | |||||

| ICE | Lisfranc | |||||

| ICE | mountain, mount everest, alkalaemia, alkalemia | |||||

| ICE | pancreatitis, alcohol | |||||

| ICE | segond fracture | |||||

| ICE | Brugada | |||||

| ICE | STEMI, hyperacture, myocardial ischemia, anterior | |||||

| ICE | eryhthema nodosum, panniculitis | |||||

| ICE | BOS fracture, battle sign, mastoid ecchymosis, bruising | |||||

| ICE | Galleazi, fracture dislocation | |||||

| Toxicology | methylene blue, Methaemoglobinemia, methemoglobin | |||||

| Toxicology | clozapine | |||||

| Toxicology | Methamphetamine, body stuffing, body packer, body stuffer | |||||

| Toxicology | TCA, tricyclic, overdose, sodium channel blockade | |||||

| Toxicology | alprazolam, BZD, benzo, benzodiazepine, benzodiazepines, flumazenil | |||||

| Toxicology | lithium, neurotoxicity, acute toxicity | |||||

| Toxicology | baclofen, GABA, Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate, GHB | |||||

| Toxicology | Carbamazepine, toxidrome, carbamazepine cardiotoxicity, Tegretol, multiple-dose activated charcoal, MDAC | |||||

| Toxicology | Hepatotoxicity, Acetaminophen, Schiodt score, hepatic encephalopathy, N-acetylcysteine, NAC | |||||

| Toxicology | beta-blocker, B Blocker, | |||||

| Toxicology | Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome, cyclical vomiting, THC, delta-nine-tetrahydrocannabinol | |||||

| Toxicology | Colchicine | |||||

| Toxicology | Clonidine | |||||

| Toxicology | Bath salts | |||||

| Toxicology | Mephedrone | |||||

| Toxicology | Bromo-DragonFLY, M-ket, Kmax, Mexxy, Meow-Meow, Mephedrone, Methoxetamine, Naphyrone, NRG-1, Salvia, K2, Spice | |||||

| Toxicology | ixodes holocyclus, tick, paralysis, | |||||

| Toxicology | cyanide, carbon monoxide | |||||

| Toxicology | hypoglycemia | |||||

| Toxicology | Ciguatera, Scombroid, fugu, puffer fish | |||||

| Toxicology | ethylene glycol, HAGMA, high anion gap metabolic acidosis, osmolar gap, Fomepizole, alcohol, ethanol | |||||

| Toxicology | iron toxicity, Desferrioxamine chelation therapy | |||||

| Toxicology | chloroquine | |||||

| Toxicology | corrosive agent | |||||

| Toxicology | Antidote | |||||

| Toxicology | Oculogyric crisis, OGC, acute dystonia, Acute Dystonic Reaction, butyrophenone, Metoclopramide, haloperidol, prochlorperazine, Benztropine | |||||

| Toxicology | Tricyclic, Theophylline, Sulfonylureas, Propanolol, Opioids, Dextropropoxyphene, Chloroquine, Calcium channel blockers, Amphetamines, ectasy | |||||

| Toxicology | verapamil, calcium channel blocker, cardiotoxic, HIET, high-dose insulin euglycemic therapy, | |||||

| Toxicology | aroma, smell | |||||

| Toxinology | snake-bite, snake bite, Brown snake, Black, Death adder, Taipan, sea snake, tiger | |||||

| Toxicology | Anticholinergic syndrome, Malignant hyperthermia, Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, Serotonin toxicity | |||||

| Toxicology | Serotonin toxicity, Serotonin syndrome, toxidrome | |||||

| Toxicology | proconvulsive, venlafaxine, tramadol, amphetamines, Bupropion, Otis Campbell | |||||

| Toxicology | TCA, tricyclic, overdose, sodium channel blockade, Amitriptyline | |||||

| Toxicology | anticoagulation, warfarin | |||||

| Toxicology | Mickey Finn, pear, | |||||

| Toxicology | thyrotoxic storm, Thyroxine, T4 | |||||

| Toxinology | white-tailed spider, Lampona, L. cylindrata, L. murina | |||||

| Toxicology | Citalopram, SSRI, | |||||

| Toxicology | warfarin | |||||

| Toxicology | warfarin, accidental ingestion, toddler | |||||

| Toxicology | ||||||

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming | |||||

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming, penetrating, barb, steve irwin, | |||||

| Toxinology | Marine, envenoming, Blue-Ringed Octopus, BRO, Hapalochlaena | |||||

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Chironex fleckeri, Box Jellyfish | |||||

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Jack Barnes, Carukia barnesi, Irukandji Syndrome, Darwin | |||||

| Toxinology | Jellyfish, marine, Jack Barnes, Carukia barnesi, Irukandji Syndrome | |||||

| Toxicology | Strychnine, opisthotonus, risus sardonicus | |||||

| Toxicology | naloxone, Buprenorphine | |||||

| Toxinology | snake-bite, snake bite, SVDK | |||||

| Toxinology | Red back spider, redback, envenoming, RBS | |||||

| Toxinology | Red back spider, redback, envenoming, RBS | |||||

| Toxicology | ||||||

| Toxicology | Acetaminophen, N-acetylcysteine, NAC | |||||

| Pediatric |

| Henoch-Schonlein Purpura, HSP, Henoch-Schönlein | ||||

| Pediatric |

| adrenal insufficiency, glucocorticoid deficiency, NAGMA, endocrine emergency | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Penile Zipper Entrapment, foreskin, release, Zip | ||||

| Pediatric |

| diarrohea, vomiting, hypokalemia, hypokalaemia, dehydration | ||||

| Pediatric |

| infantile colic, TIM CRIES, crying baby | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Pyloric stenosis, projectile vomit, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, HPS, Rankin | ||||

| Pediatric |

| respiratory distress, wheeze, foreign body, RMB, CXR, right main bronchus | ||||

| Pediatric |

| airway obstruction, stridor, severe croup, harsh cough, heliox, intubation, sevoflurane | ||||

| Pediatric |

| boot-shaped, TOF, coeur en sabot, Tetralogy of Fallot | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Spherocytes, Shistocytes, Polychromasia, reticulocytosis, anemia, anaemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, HUS | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Reye syndrome, ammonia, metabolic encephalopathy, aspirin | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Ketamine, procedural sedation, pediatric sedation | ||||

| Pediatric |

| Foreign Body, ketamine, laryngospasm, Larson's point, laryngospasm notch | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, eye trauma, Eyelid laceration, lacrimal punctum | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Retrobulbar hemorrhage, haemorrhage, RAPD, lateral canthotomy, DIP-A CONE-G, cantholysis | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, corneal abrasion, eye trauma, eyelid eversion | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, commotio retinae, eye trauma, traumatic eye injury | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Traumatic iritis, hyphaema, hyphema, | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, lens dislocation, Anterior dislocation of an intraocular lens | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, visual loss, loss of vision , blind | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Central retinal vein occlusion, CRVO, branch retinal vein occlusion, BRVO | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Central retinal artery occlusion, CRAO, cherry red spot, Branch retinal artery occlusion, BRAO | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, miosis, partial ptosis, anhidrosis, enophthalmos, horner | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, visual loss, Amaurosis fugax, TIA, transient ischemic attack | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Pre-septal cellulitis, preseptal cellulitis, peri-orbital cellulitis, Post-septal cellulitis, post septal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, AION, giant cell arteritis, GCA, Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Herpes simplex keratitis, dendritic ulcer | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Conjunctival injection, conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis, Adenovirus, trachoma, bacterial, viral, Parinaud oculoglandular conjunctivitis | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Chemical injury, cement, alkali, burn, chemical conjunctivitis, colliquative necrosis, liquefactive | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Ultraviolet keratitis, keratopathy, solar keratitis, photokeratitis, welder's flash, arc eye, bake eyes snow blindness. | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Parinaud, adie, holmes, tabes dorsalis, neurosyphylis, argyll Robertson, small irregular | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, anterior Uveitis, HLA-B27, hypopyon | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, POCUS, ONSD, | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Blowout fracture, infraorbital fracture | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, endophthalmitis, sympathetic ophthalmia, penetrating eye trauma | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, tobacco dust, Posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous debris, retinal tear, retinal break, Washer Machine Sign, Eales disease | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, dendriform keratitis, Hutchinson sign | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Siedel, FB, rust ring, Corneal foreign body, Seidel test | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Papilloedema, Papilledema, pseudopapilloedema | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, optic disc, optic neuritis, Marcus-Gunn, papillitis, multiple sclerosis, funduscopy, optic atrophy, papilledema | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, retinal break, POCUS, retinoschisis, Retinal detachment | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, cupping, glaucoma, optic neuropathy, tonometry, intraocular pressure, open angle, closed angle, gonioplasty, Acute closed-angle glaucoma | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Subconjunctival hemorrhage | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, Meibomitis, blepharitis, entropion, ectropion, canaliculitis, dacryocystitis | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, blepharospasm, blink, blinking | ||||

| EYE |

| Iritis, keratitis, acute angle-closure glaucoma, scleritis, orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) | ||||

| EYE |

| ophthalmology, fixed, dilated, pupil, holmes-adie, glass eye | ||||

| ECG |

| Wenckebach, AV block, SA, deliberate mistake, SA block | ||||

| ECG |

| dual chamber AV sequential pacemaker | ||||

| ECG |

| anterior AMI, De Winter T waves, LAD stenosis | ||||

| ECG |

| LMCA Stenosis, ST elevation in aVR, Left Main Coronary Artery | ||||

| ECG |

| LMCA, Left Main Coronary Artery Occlusion, ST elevation in aVR | ||||

| ECG |

| VT, BCT, WCT, Brugada criteria, Verekie | ||||

| ECG |

| severe hypokalaemia, spironalactone, rhabdomyolysis, ECG, u wave, diabetic ketoacidosis | ||||

| ECG |

| pacing, pacemaker, post-op, Mobitz I, Wenckebach, AV block | ||||

| ECG |

| bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia, CPVT, digoxin toxicity | ||||

| ECG |

| congenital, short QT syndrome, SQTS, AF, Atrial fibrillation | ||||

| ECG |

| RVOT, broad complex tachycardia, BCT, Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Tachycardia, VF, Arrest, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy, ARVC | ||||

| ECG |

| NSTEMI, inverted U wave, | ||||

| ECG |

| tricyclic antidepressant, TCA, Doxepin, QRS broadening, cardiotoxic | ||||

| ECG |

| AIVR, Accelerated idioventricular rhythm, Isorhythmic AV dissociation, Sinus arrhythmia, idioventricular | ||||

| ECG |

| LAD, LBBB, High left ventricular voltage, HLVV, WPW, Broad Complex Tachycardia | ||||

| ECG |

| tachy-brady, AVNRT, flutter, polymorphic VT, VF, torsades de pointes, R on T, Cardioversion | ||||

| ECG |

| LBBB, Wellens, ECG, proximal LAD, occlusion, rate-dependent, inferior ischaemia | ||||

| ECG |

| SI QIII TIII, PE, PTE pulmonary embolism, PEA arrest, RBBB, LAD | ||||

| Cardiology |

| HOCM, STE, aVR, LMCA, torsades des pointes. TDP | ||||

| Cardiology |

| aortic arch, right sided, diverticulum of Kommerell | ||||

| Cardiology |

| IABP, CABG, shock, circulatory collapse | ||||

| Cardiology |

| electrical alternans, ECG, pulsus paradoxus | ||||

| Cardiology |

| Intra-aortic Balloon Pump, Waveform, dicrotic notch | ||||

| Cardiology |

| DeBakey, TAA, aortic dissection, CTA | ||||

| Cardiology |

| Tetraology of Fallot, BT shunt, Blalock-Tausig, ToF | ||||

| Cardiology |

| PVP, cement, embolus, Percutaneous Vertebroplasty | ||||

| Cardiology |

| Pulmonary Embolism, PTE, PE, McConnell, thrombolysis, echo | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Missed posterior shoulder dislocation | ||||

| Paediatrics |

| rash, neck nodule, Kawasaki | ||||

| Paediatrics |

| rash, fever, scarlet, strawberry, Group A Beta Haemolytic Streptococci (GABHS) | ||||

| Tropical Travel |

| diphtheria, pseudomembrance, grey tonsils, pseudomembrane, tonsillitis, diphtheria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, gram-positive bacillus | ||||

| Urinalysis |

| purple, urine, indican, indican | ||||

| Urinalysis |

| brown, urine, rhabdomyolysis | ||||

| Urinalysis |

| green, urine, propofol, PRIS | ||||

| Urinalysis |

| green, urine | ||||

| Urinalysis |

| orange, urine | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Nail, trauma, hematoma, subungual, haematoma, nail-bed | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Extensor tendon, hand injury, extensor digiti minimi, | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Thumb, fracture, base, phalanx, metacarpal, Edward Hallaran Bennett, bipartate | ||||

| Paediatrics |

| Food allergy, enterocolitis, | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| FOOSH, wrist fracture, FOOSH - 'fall onto outstretched hand', Barton fracture, John Rhea Barton | ||||

| Paediatrics |

| pulled elbow, nursemaid, hyperpronation | ||||

| Cardiology |

| Phlegmasia, dolens | ||||

| Cardiology |

| ICC, intercostal, intra-cardiac, iatrogenic | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Compartment syndrome, Volkmann, fasciotomy | ||||

| Bone and Joint |

| Ankle, compound, fracture, dislocation, Six Hour Golden Rule, saline, iodine | ||||

| ENT |

| retropharngeal abscess, posterior pharynx, mediastinitis, Lemierre syndrome, Fusobacterium necrophorum | ||||

| ENT |

| enlarged tonsils, pharyngitis, tonsillitis | ||||

| Toxicology | Colgout, colchicine, label, fenofibrate | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Mary Mallon, Salmonella typhi, typhoid, typhoid mary | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Dengue Fever, single-stranded RNA virus, Aedes, mosquito, Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS), Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF) | |||||

| Tropical Travel | AIDS, Human immunodeficiency virus, lentivirus, anti-retroviral, | |||||

| Tropical Travel | tuberculosis | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Falciparum, Vivax, Ovale, Malariae, Knowlesi, Plasmodium | |||||

| Tropical Travel | cholera, gram-negative comma-shaped bacillus, rice water stool, John Snow Pump, V. cholerae, vibrio | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Entamoeba histolytica, protozoan parasite, Amoebic dysentery, Flask Shaped amoebic trophozoite, Bloody stool, | |||||

| Tropical Travel | shigellosis, Shigella, Enterotoxin, dysentery, | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Tetanus, Tetanispasmin, Clostridium tetani, lock jaw, Opisthotonus, Autonomic dysfunction, toxoid | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Rabies Immunoglobulin | |||||

| Tropical Travel | Koplik, measles, rash, rubeola, Morbilivirus, | |||||

| Trauma | permissive hypotension, MBA, MVA, widened mediastinum, pleural effusion, ICC | |||||

| Trauma | knife, penetrating chest wound | |||||

| Trauma | knife, penetrating chest wound | |||||

| Trauma | TBSA %, Burns Wound Assessment, Total Body Surface Area | |||||

| Trauma | Arterial pressure index (API), DPI (Doppler Pressure Index), Arterial Brachial Index or Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) | |||||

| Trauma | crush injury, degloving, deglove, amputation | |||||

| Trauma | hip dislocation, Allis reduction, pelvic fracture | |||||

| Trauma | Pelvis fracture, stabilization, stabilisation, | |||||

| Trauma | pelvic stabilization, Pelvis fracture, stabilisation, Pre-peritoneal packing | |||||

| Trauma | massive transfusion protocol, Recombinant Factor VIIa, Thromboelastography (TEG) | |||||

| Trauma | Critical bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, haemorrhagic shock, lethal triad, acute coagulopathy of trauma | |||||

| Trauma | penetrating abdominal trauma | |||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | penetrating chest trauma wound, stab, | |||||

| Trauma | Right Main Bronchus, RMB, Tracheostomy, Tooth, foreign Body | |||||

| Trauma | Lobar collapse, aspiration, blood clot | |||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm with strangulation of viscera | |||||

| Trauma | eschar, burns, full thickness, | |||||

| Trauma | supine hypotension syndrome | |||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | iPhone | |||||

| Trauma | oleoma, lipogranuloma, | |||||

| Trauma | oral commissure, lingual artery hemorrhage, | |||||

| Trauma | polymer fume fever, dielectric heating, super-heating, thermal injury | |||||

| Trauma | DRE, Digital rectal exam examination trauma | |||||

| Trauma | Injury Severity score, ISS, golden hour, seatbelt sign | |||||

| Trauma | primary secondary survey | |||||

| Trauma | extradural hemorrhage, EDH, Monro-Kellie | |||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | ||||||

| Trauma | GU, trauma, penis, penile, urethra, bladder, rupture | |||||

| Pulmonary | swine flu, pneumomediastinum, CXR | |||||

| Pulmonary | Thrombocytopenia, antiphospholipid syndrome | |||||

| Pulmonary | Hermann Boerhaave, Boerhaave syndrome, esophagus rupture, oesophagus | |||||

| Pulmonary | ||||||

| Pulmonary | pneumococcal pneumonia, HIV, bronchoscope, anatomy, RMB | |||||

| Pulmonary | subcutaneous emphysema, FLAAARDS, | |||||

| Pulmonary | respiratory acidosis, hypercapnoea | |||||

| Pulmonary | hypersensivity pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar haemorrhage, alveolar infiltrates | |||||

| Pulmonary | Lung collapse, recruitment maneuver, bronchoscopy | |||||

| Pulmonary | Vocal cord dysfunction, VCD, paradoxical vocal cord motion, PVCM, posterior chinking | |||||

| Pulmonary | pneumococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin-resistant | |||||

| Pulmonary | DOPES, | |||||

| Pulmonary | asthma | |||||

| Pulmonary | dyssynchrony, mechanical ventilation, PEEP, Plateau pressure | |||||

| Pulmonary | pneumomediastinum, tracheostomy, trachy, complication | |||||

| Pulmonary | PERC rule, D-Dimer, Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria, HAD CLOTS, | |||||

| Pulmonary | AMS, acute mountain sickness, high altitude, High-altitude cerebral edema, HACE, HAPE, High-altitude pulmonary edema | |||||

| Pulmonary | ||||||

| Resus | Pulseless electrical activity, PEA | |||||

| Resus | intraosseous access, EZ-IO, | |||||

| Resus | ||||||

| Resus | Rocuronium, suxamethonium, succinylcholine, non-depolarising muscle relaxant, sugammadex, safe apnoea time | |||||

| Resus | FEAST, trial, research, pediatric, fluid resuscitation | |||||

| Resus | ||||||

| Resus | ||||||

| Resus | ||||||

| Resus | ICC, intercostal | |||||

| Resus | Mechanical ventilation | |||||

| Oncology | SVC obstruction | |||||

| Oncology | Tumour lysis syndrome, Tumor lysis syndrome | |||||

| Oncology | lung metastases braine mets testicular cancer BEP chemotherapy, Cannonball metastases | |||||

| Oncology | re-expansion pulmonary oedema edema | |||||

| Metabolic | abdominal aortic aneurysm, AAA, rupture, CT, rhabdomyolysis, creatine kinase | |||||

| Metabolic | hypokalemia, hypokalaemia, periodic paralysis, u wave | |||||

| Metabolic | CATMUDPILES, OGRE, NAGMA, HAGMA, USED CARP, hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis | |||||

| Metabolic | anion gap, pyroglutamic acidemia, HAGMA, high-anion gap, high anion, 5-oxoprolinemia, γ-glutamyl cycle, staph aureus, sepsis | |||||

| Metabolic | HAGMA, high-anion gap, high anion, hypernatraemia, hypernatremia | |||||

| Metabolic | hypokalaemia, hypokalemia, potassium, systemic bromism, coke, pepsi, coca-cola | |||||

| Metabolic | CATMUDPILES, renal failure, HAGMA, LTKR | |||||

| Metabolic | ||||||

| Metabolic | acute hepatitis, arterial blood gas, fulminant hepatic failure, lactic acidosis, lactic acidosis with hypoglycaemia, metabolic acidosis, metabolic muddle | |||||

| Metabolic | hyperammonaemia, hyperammonemia | |||||

| Metabolic | Hyponatraemia, hypertonic saline, ultramarathon, runner, EAH, pontine myelinoysis | |||||

| Metabolic | Hyponatraemia, hypertonic saline, pontine myelinoysis, Osmolality, desmopressin, SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone secretion | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | Appendagitis, Epiploic, Abdominal pain, CT abdomen | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | CT abdomen, Small bowel obstruction, SBO | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | cathine, cathione, khat, hepatitis, cathionine | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | rectal foreign body, FB | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | abdominal compartment syndrome, intra-abdominal pressure, intra-abdominal hypertension, IAH, ACS | |||||

| Hematology | fibrinolytic, VTE, Wells, PERC | |||||

| Hematology | factor VIIa, rFVIIa, novoseven | |||||

| Hematology | Critical Bleeding, Massive Transfusion, Tranexamic Acid, TxA, MTP | |||||

| Hematology | Dyshemoglobinemia, Acute myeloid leukemia, AML | |||||

| Immunological | angiodema, angioedema, lip sweliing | |||||

| Immunological | frusemide, furosemide, lasix, sulfa, | |||||

| Immunological | wegener, GPA, granulomatosis, palpable purpura | |||||

| Obstetric | amniotic fluid embolism, DIC, obstetric complication, disseminated intravascular coagulation, schistocytes, | |||||

| Microbial | CSF, Meningococcal meningitis, | |||||

| Microbial | fulminant bacterial pneumonia, septic shock, Pneumococcus, Streptococcus pyogenes, urinary pneumococcal antigen, | |||||

| Microbial | Legionella, community acquired pneumonia | |||||

| Microbial | Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, Toxic-shock syndrome | |||||

| Microbial | ||||||

| Microbial | ||||||

| Microbial | Norovirus | |||||

| Toxicology | Coma, similie, metaphor, flashcard, toxidromes, anticholinergic, cholinergic, PHAILS, OTIS CAMPBELL, PACED, FAST, COOLS, CT SCAN | |||||

| Neurology | HIV, Mass effect, CNS lesion, Brain lesion | |||||

| Neurology | pancoast, argyll robertson, holmes-adie, coma, pinpoint, pin-point, horner syndrome | |||||

| Neurology | rule of 4, rules of four, brainstem, weber syndrome, wallenberg | |||||

| Neurology | rule of 4, rules of four, brainstem, Nothnagel syndrome, benedikt, claude, | |||||

| Neurology | ||||||

| Neurology | ||||||

| Neurology | ||||||

| Neurology | Unilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, medial longitudinal fasciculus, MLF, INO, one-and-a-half syndrome | |||||

| Neurology | GSW, gunshot wound, bullet, TBI, Codman ICP monitor, Trans-cranial doppler, Near-infrared spectroscopy, NIRS, cerebral microdialysis catheter | |||||

| Neurology | BPPV, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, Dix-Hallpike test, semont, epley, dix hallpike, brandt-daroff | |||||

| Neurology | Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis, teratoma | |||||

| To err is human | cognitive error, bias, entrapment | |||||

| To err is human | rule of thumb, heuristic, satisficing, cognitive bias, metacognition | |||||

| To err is human | | Anchoring Bias, confirmation, satisficing, clustering bias | ||||

| Cardiology | ||||||

| Paediatric | pediatric |

LITFL Top 100 Self Assessment Quizzes

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to write a medical...

How to write a medical case report

- Related content

- Peer review

- Seema Biswas , editor-in-chief, BMJ Case Reports, London, UK ,

- Oliver Jones , student editor, BMJ Case Reports, London, UK

Two BMJ Case Reports journal editors take you through the process

This article contains...

- Choosing the right patient

- Choosing the right message

- Before you begin - patient consent

- How to write your case report

- How to get published

During medical school, students often come across patients with a unique presentation, an unfamiliar response to treatment, or even an obscure disease. Writing a case report is an excellent way of documenting these findings for the wider medical community—sharing new knowledge that will lead to better and safer patient care.

For many medical students and junior doctors, a case report may be their first attempt at medical writing. A published case report will look impressive on your curriculum vitae, particularly if it is on a topic of your chosen specialty. Publication will be an advantage when applying for foundation year posts and specialty training, and many job applications have points allocated exclusively for publications in peer reviewed journals, including case reports.

The writing of a case report rests on skills that medical students acquire in their medical training, which they use throughout their postgraduate careers: these include history taking, interpretation of clinical signs and symptoms, interpretation of laboratory and imaging results, researching disease aetiology, reviewing medical evidence, and writing in a manner that clearly and effectively communicates with the reader.

If you are considering writing a case report, try to find a senior doctor who can be a supervising coauthor and help you decide whether you have a message worth writing about, that you have chosen the correct journal to submit to (considering the format that the journal requires), that the process is transparent and ethical at all times, and that your patient is not compromised in your writing. Indeed, try to include your patient in the process from the …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 1

- What is a case study?

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Roberta Heale 1 ,

- Alison Twycross 2

- 1 School of Nursing , Laurentian University , Sudbury , Ontario , Canada

- 2 School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Roberta Heale, School of Nursing, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON P3E2C6, Canada; rheale{at}laurentian.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102845

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

What is it?

Case study is a research methodology, typically seen in social and life sciences. There is no one definition of case study research. 1 However, very simply… ‘a case study can be defined as an intensive study about a person, a group of people or a unit, which is aimed to generalize over several units’. 1 A case study has also been described as an intensive, systematic investigation of a single individual, group, community or some other unit in which the researcher examines in-depth data relating to several variables. 2

Often there are several similar cases to consider such as educational or social service programmes that are delivered from a number of locations. Although similar, they are complex and have unique features. In these circumstances, the evaluation of several, similar cases will provide a better answer to a research question than if only one case is examined, hence the multiple-case study. Stake asserts that the cases are grouped and viewed as one entity, called the quintain . 6 ‘We study what is similar and different about the cases to understand the quintain better’. 6

The steps when using case study methodology are the same as for other types of research. 6 The first step is defining the single case or identifying a group of similar cases that can then be incorporated into a multiple-case study. A search to determine what is known about the case(s) is typically conducted. This may include a review of the literature, grey literature, media, reports and more, which serves to establish a basic understanding of the cases and informs the development of research questions. Data in case studies are often, but not exclusively, qualitative in nature. In multiple-case studies, analysis within cases and across cases is conducted. Themes arise from the analyses and assertions about the cases as a whole, or the quintain, emerge. 6

Benefits and limitations of case studies

If a researcher wants to study a specific phenomenon arising from a particular entity, then a single-case study is warranted and will allow for a in-depth understanding of the single phenomenon and, as discussed above, would involve collecting several different types of data. This is illustrated in example 1 below.

Using a multiple-case research study allows for a more in-depth understanding of the cases as a unit, through comparison of similarities and differences of the individual cases embedded within the quintain. Evidence arising from multiple-case studies is often stronger and more reliable than from single-case research. Multiple-case studies allow for more comprehensive exploration of research questions and theory development. 6

Despite the advantages of case studies, there are limitations. The sheer volume of data is difficult to organise and data analysis and integration strategies need to be carefully thought through. There is also sometimes a temptation to veer away from the research focus. 2 Reporting of findings from multiple-case research studies is also challenging at times, 1 particularly in relation to the word limits for some journal papers.

Examples of case studies

Example 1: nurses’ paediatric pain management practices.

One of the authors of this paper (AT) has used a case study approach to explore nurses’ paediatric pain management practices. This involved collecting several datasets:

Observational data to gain a picture about actual pain management practices.

Questionnaire data about nurses’ knowledge about paediatric pain management practices and how well they felt they managed pain in children.

Questionnaire data about how critical nurses perceived pain management tasks to be.

These datasets were analysed separately and then compared 7–9 and demonstrated that nurses’ level of theoretical did not impact on the quality of their pain management practices. 7 Nor did individual nurse’s perceptions of how critical a task was effect the likelihood of them carrying out this task in practice. 8 There was also a difference in self-reported and observed practices 9 ; actual (observed) practices did not confirm to best practice guidelines, whereas self-reported practices tended to.

Example 2: quality of care for complex patients at Nurse Practitioner-Led Clinics (NPLCs)

The other author of this paper (RH) has conducted a multiple-case study to determine the quality of care for patients with complex clinical presentations in NPLCs in Ontario, Canada. 10 Five NPLCs served as individual cases that, together, represented the quatrain. Three types of data were collected including:

Review of documentation related to the NPLC model (media, annual reports, research articles, grey literature and regulatory legislation).

Interviews with nurse practitioners (NPs) practising at the five NPLCs to determine their perceptions of the impact of the NPLC model on the quality of care provided to patients with multimorbidity.

Chart audits conducted at the five NPLCs to determine the extent to which evidence-based guidelines were followed for patients with diabetes and at least one other chronic condition.

The three sources of data collected from the five NPLCs were analysed and themes arose related to the quality of care for complex patients at NPLCs. The multiple-case study confirmed that nurse practitioners are the primary care providers at the NPLCs, and this positively impacts the quality of care for patients with multimorbidity. Healthcare policy, such as lack of an increase in salary for NPs for 10 years, has resulted in issues in recruitment and retention of NPs at NPLCs. This, along with insufficient resources in the communities where NPLCs are located and high patient vulnerability at NPLCs, have a negative impact on the quality of care. 10

These examples illustrate how collecting data about a single case or multiple cases helps us to better understand the phenomenon in question. Case study methodology serves to provide a framework for evaluation and analysis of complex issues. It shines a light on the holistic nature of nursing practice and offers a perspective that informs improved patient care.

- Gustafsson J

- Calanzaro M

- Sandelowski M

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

- Biochemistry

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Pharmacology

- Anesthesiology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Clinical Neuroanatomy Cases

- Clinical Nutrition Cases

- Acid-Base Disturbance Cases

- Chest Imaging Cases

- Family Medicine Board Review

- Fluid/Electrolyte and Acid-Base Cases

- G&G Pharm Cases

- Harrison’s Visual Case Challenge

- Internal Medicine Cases

- Medical Microbiology Cases

- Neuroanatomy Cases

- Pathophysiology Cases

- Principles of Rehabilitation Medicine Case-Based Board Review

- Browse by System

- Internal Medicine Med-Peds Pediatrics

- Browse by Curriculum

| Below is a limited selection of Case Files content on AccessMedicine. Click here to browse the full set of Case Files on , which requires a separate institutional purchase. |

Basic Science

| Date | Medical Condition | Therapeutic Goals | Drug-Therapy Problem | Recommendations and Interventions | Monitoring Parameters, Desired Endpoints, and Frequency | Follow-up plan |

|---|

- Research Guides

- University Libraries

- Medical Sciences Guides

Medical Residents & Fellows--Library Resources

- Case Studies, Videos, Images

- General Resources

Multimedia/Teaching Resources

Case Studies

Multimedia resources - general, access medicine videos, specialty videos, power point presentations, audio resources.

- Departments/Specialties

- Drugs/Pharmacy

- Research/Scholarly/Citation Management

- Integrative Medicine

- Step 3 Review

- Physician Wellness Resources

- Author Profile

- Access Case Files

- Case Files Collection Offers Case Files content in an interactive format. Helps students learn and apply basic science and clinical medicine concepts in the context of realistic patient cases. Features the complete collection of basic science, clinical medicine, and post-graduate level cases from 23 Case Files series books, and the personalized functionality to let users mark their progress through cases.

- Cases on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the Health Professions Educator, 1e, 2023

- Kumar & Clark's Cases in Clinical Medicine, 4e, 2021

- Lippincott Health Library Clerkship/Clinical Rotations Cases Case studies in family medicine, internal medicine, OB/GYN, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery. Can be broken down into any one of these topics.

- NEJM Clinical Cases Resource Center The Clinical Cases Resource Center on NEJM.org offers a wealth of interactive case studies and educational resources formulated specifically for teaching, continuous learning, and professional development.

- Bates' Visual Guide to Physical Examination, 2023 (videos) A companion website to Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. Videos provide an evidence-based approach for physical examination techniques. Includes information on abnormalities and differential diagnoses. Categories of videos include Physical Examination, Communication & Interpersonal Skills, and OSCE Clinical Skills.

- ClinicalKey Hundreds of images and videos to select from.

- Instructor's Resources - Access Medicine

- JoVE Science Education videos Videos provide basic medical instruction.

- New England Journal of Medicine Multimedia

- Ovid Multimedia

- Procedural Videos - AccessMedicine

- Procedure Videos (formerly Procedures Consult) This link opens in a new window A procedure reference tool that offers access to complete details on how to prepare for, perform and follow up on the most common procedures. Many are demonstrated with videos. To set up a Procedure Video group to create and manage assignments, please contact the Medical Sciences Library ([email protected] or 979-845-7428).

- Access Medicine Contains a wide variety of medical videos, Including many Procedural Videos for Emergency Medicine/Intensive Care, Pediatrics, Gastroenterology/Hepatology, Gynecology, Neurology, Orthopedics, Dermatology, and Pulmonary Medicine

- Access Emergency Medicine These videos are part of a comprehensive set of study materials and review questions for the emergency medicine residency. Each module consists of 1 week of material. There are two rounds for each topic; Round 1 is designed for years 1-2 of residency, while Round 2 is designed for years 2-4 of residency. Completion of this curriculum is designed to give the residents a thorough multi-modality review of EM major topics.

- Access Neurology Contains videos on EEG, Movement Disorders, and Physical Exam. Also includes an interactive neuroanatomy atlas, lectures and animated tours of the brain and nervous system.

- Access Pediatrics Contains a comprehensive list of of videos for pediatrics practice.

- Access Pharmacy Contains videos and animations on pharmacology, arranged by organ systems. Harrison's Pathophysiology Animations are also available.

- Access Surgery Contains a large variety of procedural surgical videos arranged by organ system. Also contains videos from Zollinger's Video Atlas of Surgical Operations.

- Andreoli and Carpenter's Cecil Essentials of Medicine, 10e, 2022 Link to 20 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- Atlas of Cardiac Surgical Techniques, 2e, 2019 Link to 22 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- The Atlas of Emergency Medicine Videos, 5e, 2021 Virtual and ultrasound videos.

- Blumgart's Video Atlas : Liver, Biliary, & Pancreatic Surgery, 2e, 2021 Link to 121 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents". Virtual surgical procedures are sometimes later in the videos.

- Counseling and Therapy in Video Over 500 videos allow students and scholars to see, experience, and study counseling. Many videos include supplementary materials to aid in classroom discussions and assignments.

- Green's Operative Hand Surgery, 8e, 2022 Link to 59 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- Hagberg and Benumof's Airway Management, 5e, 2023 Link to 30 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents"

- Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 21e, 2022 Virtual and ultrasound videos.

- Insall & Scott Surgery of the Knee, 6e, 2018 Link to 256 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- Morrey's The Elbow and Its Disorders, 5e, 2018 Link to 42 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care, 7e, 2019 Over 200 videos on emergency and critical care.

- Textbook of Critical Care, 8e, 2024 Link to 51 videos by clicking on "Videos" button under "Table of Contents".

- Access Medicine Instructor's Resources

- Access Medicine Run the List Podcast Discussions on key principles of internal medicine, around board-style case vignettes from the acclaimed Harrison’s Self Assessment and Board Review.

- Access Medicine Symptom to Diagnosis Podcast A case-based discussion of signs, symptoms and diagnostics tests to improve clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice.

- Case Files Podcasts Features a series of conversational, informative podcasts correlated with the cases featured in Case Files Collection

- Harrison's Podcasts

- The Symptom to Diagnosis Podcasts A case-based discussion of signs, symptoms and diagnostics tests to improve clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice.

- USMLE Images for the Boards : a comprehensive image-based review, 1e, 2013

- VisualDX This link opens in a new window A Web and mobile enabled visual clinical decision support system used to build a differential by selecting symptoms and other parameters. View descriptions of possible matches, critical alerts, and images to support selection of the best diagnosis.

- Assessing Competence in Medicine and Other Health Professions, 1e, 2018

- Cinemeducation : a comprehensive guide to using film in medical education Paper copy available in MSL@RoundRock W 418 C5749 2005

- Curriculum Development for Medical Education : a six-step approach, 4e, 2022

- Evidence-based medicine : how to practice and teach EBM, 5e, 2019

- Healthy Presentations : how to craft exceptional lectures in medicine, the health professions, and the biomedical sciences, 1e, 2021

- The Master Adaptive Learner : from the AMA MedEd Innovation Series, 1e, 2020 Call Number: W 18 M4231 2020 Print copies available in MSL@Bryan, MSL@College Station, MSL@Dallas, and MSL@Houston

- A Primer for the Clinician Educator : supporting excellence and promoting change through storytelling, 1e, 2023

- Remediation Case Studies : helping struggling medical learners, 1e, 2021 Print copy available in MSL@College Station W 18 G934rc 2021

- Successful Doctoral Training in Nursing and Health Sciences : a guide for supervisors, students and advisors, 1e, 2022

- Survey Methods for Medical and Health Professions Education : a six-step approach, 1e, 2022 Print copy available in MSL@College Station W 20.5 S9631 2022

- Teaching Evidence-Based Medicine : a toolkit for educators, 1e, 2023

- Teaching Writing in the Health Professions : perspectives, problems, and practices, 1e, 2021

- Written Assessment in Medical Education, 1e, 2023

- << Previous: General Resources

- Next: Departments/Specialties >>

- Last Updated: Jun 17, 2024 8:43 AM

- URL: https://tamu.libguides.com/residents

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2024

Circulating small extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease: a case–control study of neuro-inflammation and synaptic dysfunction

- Rishabh Singh 1 ,

- Sanskriti Rai 1 ,

- Prahalad Singh Bharti 1 ,

- Sadaqa Zehra 1 ,

- Priya Kumari Gorai 2 ,

- Gyan Prakash Modi 3 ,

- Neerja Rani 2 ,

- Kapil Dev 4 ,

- Krishna Kishore Inampudi 1 ,

- Vishnu V. Y. 5 ,

- Prasun Chatterjee 6 ,

- Fredrik Nikolajeff 7 &

- Saroj Kumar 1 , 7

BMC Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 254 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

194 Accesses

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Chronic inflammation and synaptic dysfunction lead to disease progression and cognitive decline. Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are implicated in AD progression by facilitating the spread of pathological proteins and inflammatory cytokines. This study investigates synaptic dysfunction and neuroinflammation protein markers in plasma-derived sEVs (PsEVs), their association with Amyloid-β and tau pathologies, and their correlation with AD progression.

A total of 90 [AD = 35, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) = 25, and healthy age-matched controls (AMC) = 30] participants were recruited. PsEVs were isolated using a chemical precipitation method, and their morphology was characterized by transmission electron microscopy. Using nanoparticle tracking analysis, the size and concentration of PsEVs were determined. Antibody-based validation of PsEVs was done using CD63, CD81, TSG101, and L1CAM antibodies. Synaptic dysfunction and neuroinflammation were evaluated with synaptophysin, TNF-α, IL-1β, and GFAP antibodies. AD-specific markers, amyloid-β (1–42), and p-Tau were examined within PsEVs using Western blot and ELISA.

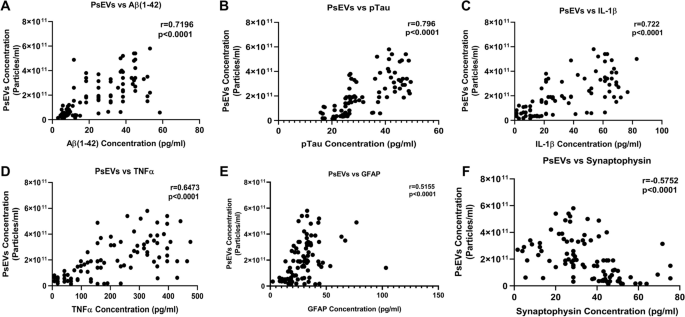

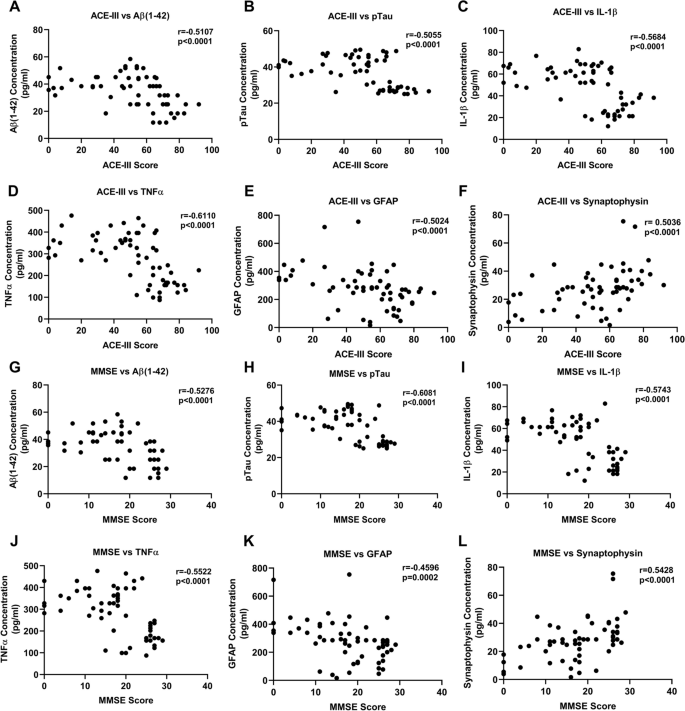

Our findings reveal higher concentrations of PsEVs in AD and MCI compared to AMC ( p < 0.0001). Amyloid-β (1–42) expression within PsEVs is significantly elevated in MCI and AD compared to AMC. We could also differentiate between the amyloid-β (1–42) expression in AD and MCI. Similarly, PsEVs-derived p-Tau exhibited elevated expression in MCI compared with AMC, which is further increased in AD. Synaptophysin exhibited downregulated expression in PsEVs from MCI to AD ( p = 0.047) compared to AMC, whereas IL-1β, TNF-α, and GFAP showed increased expression in MCI and AD compared to AMC. The correlation between the neuropsychological tests and PsEVs-derived proteins (which included markers for synaptic integrity, neuroinflammation, and disease pathology) was also performed in our study. The increased number of PsEVs correlates with disease pathological markers, synaptic dysfunction, and neuroinflammation.

Conclusions

Elevated PsEVs, upregulated amyloid-β (1–42), and p-Tau expression show high diagnostic accuracy in AD. The downregulated synaptophysin expression and upregulated neuroinflammatory markers in AD and MCI patients suggest potential synaptic degeneration and neuroinflammation. These findings support the potential of PsEV-associated biomarkers for AD diagnosis and highlight synaptic dysfunction and neuroinflammation in disease progression.

Peer Review reports

The progressive neurodegenerative condition known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by cognitive decline as a result of the formation of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and chronic neuroinflammation that leads to neurodegeneration [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Synapse loss is a crucial pathophysiological event in disease progression, and synaptic proteins have been extensively studied due to earlier perturbations [ 4 , 5 ]. The pathological hallmark of AD, amyloid-β plaques, originates from the imprecise cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase generating amyloid-β peptide forms [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Primary amyloid-β peptide forms are Aβ40 and Aβ42, where the majority of the amyloid-β plaques in AD brains are composed of Aβ42 [ 10 ]. Many point mutations in APP and γ-secretase cause familial early-onset AD, favoring Aβ42 formation, causing amyloid-β peptides prone to aggregate as fibrils and plaques [ 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Hyperphosphorylation of tau causes the formation of NFTs. The combined effect of accumulation of NFTs, amyloid-β fibrils, and plaques leads to neuronal function loss and cell death [ 15 , 16 ]. Aβ plaques activate immune receptors on microglia, thereby releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that mediate neuroinflammation, which, if it reaches a chronic level, causes damage to brain cells, including axonal demyelination and synaptic pruning [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. In addition to these, other proteins, including the neurofilament light (NFL) protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and synaptic proteins, have also been identified as AD biomarkers [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Understanding the intricate dynamics of AD in terms of its varied pathophysiological manifestations, such as neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and proteinopathy, is essential for developing potential therapeutic interventions for AD and biomarker discovery. In clinical practice, cognitive assessment tools such as the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE-III) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) are used to diagnose AD. These tools evaluate verbal fluency and temporal orientation, although results may be influenced by subject bias [ 29 , 30 , 31 ].

In recent years, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) or exosomes have been acknowledged as crucial mediators of communication and signaling within the body, contributing significantly to the transmission of cellular cargo in various health and disease states. They also play a notable role in disseminating protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases [ 32 ]. sEVs are bi-layered membrane vesicles that have a heterogeneous group of (< 200 nm in diameter) that are found in different human body fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, and ascites, and that are actively released by all cell types [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. For their functions in various physiological and pathological circumstances, sEVs are the most extensively researched type of EV [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. sEVs exchange information between cells by transferring bioactive components (nucleic acids and proteins) [ 39 ]. As the sEVs’ composition bears the molecular signature of the secreting cell and bears an intrinsic property of transversing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) in both directions [ 40 , 41 ], they are a target of constant research in neurodegenerative disease. Furthermore, sEVs released by neuronal cells are crucial in transmitting signals to other nerve cells, influencing central nervous system (CNS) development, synaptic activity regulation, and nerve injury regeneration. Moreover, sEVs exhibit a dual function in neurodegenerative processes, as sEVs not only play an essential role in clearing misfolded proteins, thereby exerting detoxifying effects and providing neuroprotection [ 42 ]. On the other hand, they also have the potential to participate in the propagation and aggregation of misfolded proteins, particularly implicated in the pathological spread of Tau aggregates as indicated by both in vitro and in vivo studies [ 43 ]. As a protective mechanism, astrocytes (most abundant glial cells) accumulate at the locations where Aβ peptides are deposited, internalizing and breaking down aggregated peptides [ 44 ]. However, severe endosomal–lysosomal abnormalities arise in astrocytes when a significantly large amount of Aβ accumulates within astrocytes for a prolonged period without degradation [ 45 , 46 ]. Astrocytes then release engulfed amyloid-β (1-42) protofibrils through exosomes, leading to severe neurotoxicity to neighboring neurons [ 44 ]. Additionally, it has been found that the release of amyloid-β by microglia in association with large extracellular vesicles (Aβ-lEVs) damages synaptic plasticity and modifies the architecture of the dendritic spine [ 47 ]. Thus, sEVs can be a compelling subject for the investigation to understand AD’s inflammation and synaptic dysfunction [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ].

In this study, we reported that protein levels are associated with AD pathology, neuroinflammation, and synaptic dysfunction in plasma-derived small extracellular vesicles (PsEVs). Our objective was to understand the pathophysiological process, neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and Aβ pathology through sEVs. Our study revealed a significant correlation between the concentration of cargo proteins derived from PsEVs and clinical diagnosis concerning ACE-III and MMSE scores. Furthermore, the levels of these studied proteins within PsEVs could differentiate between patients with MCI and AD. Thus, our study sheds light on the potential of PsEVs in understanding AD dynamics and offers insights into the underlying mechanisms of disease progression.

Subject recruitment

A total of n = 35 AD patients and n = 25 subjects with MCI were recruited from the Memory Clinic, Department of Geriatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Additionally, n = 30 healthy AMC (volunteers) were recruited. The inclusion criteria were as follows: a clinical diagnosis of MCI and AD patients using ACE-III and MMSE tests. The exclusion criteria encompass medical conditions such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, liver disease, hematological disorders, or stroke, as well as psychiatric conditions, substance abuse, or any impediment to participation. Controls were healthy, age-matched adults without neurological symptoms. AMC was 60–71, MCI was 65–79, and AD was 70–80 years of age range (Table 1 ). Neuropsychological scores, viz., ACE-III and MMSE, were recorded before subject selection.

Study ethical approval

The institutional ethics committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, granted the study ethical permission. The study has been granted the ethical approval number IECPG-670/25.08.2022. Following the acquisition of the written informed consent, all participants were enrolled.

Sample collection

One milliliter of blood was drawn from each participant using venipuncture, and blood collection vials were kept on ice during collection. The blood was centrifuged at 1700 g for 20 min at 4 °C to remove the cells, and the straw-colored plasma was collected. It was further clarified by centrifuging for 30 mi at 4 °C at 10,000 g. Finally, cleared plasma was stored at − 80 °C until further use. The samples were used for the downstream experiment after being thawed on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 g.

Isolation of PsEVs

The PsEVs were extracted by chemical-based precipitation from the plasma samples of AD patients, MCI patients, and AMC, as discussed previously [ 53 , 54 ]. In brief, 180 μL of plasma sample was used and filtered with 0.22 μm filter (SFNY25R, Axiva), followed by overnight incubation with the chemical precipitant (14% polyethylene glycol 6000) (807,491, Sigma). The samples underwent an hour-long, 13,000 g centrifugation at 4 °C the next day. Before being resuspended in 200 μL of 1X PBS (ML116-500ML, HiMedia), the pellet was first cleaned twice with 1X PBS. Before downstream experiments, the sEVs-enriched fraction was further filtered through a 100-kDa filter (UFC5100, Millipore).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

5000-fold dilution in 1X-PBS buffer was used for the NTA of PsEVs. In the ZetaView Twin system (Particle Metrix, Germany) sample chamber, 1 mL of diluted PsEVs sample was introduced. The following parameters were used throughout three cycles of scanning 11 cell locations each, and 60 frames per position were collected (video setting: high, focus: autofocus, shutter: 150, 488 nm internal laser, camera sensitivity: 80, cell temperature: 25 °C. CMOS cameras were used for recording, and the built-in ZetaView Software 8.05.12 (Particle Metrix, Germany) was used to analyze: 10 nm as minimum particle size, 1000 nm as maximum particle size, and 30 minimum particle brightness.

Transmission electron microscopy for morphological characterization

Transmission electron microscopy was employed to investigate PsEVs’ ultrastructural morphology. The resultant PsEVs pellet was diluted with PBS using 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). A carbon-coated copper grid of 300 mesh (01843, Ted Pella) was used to adsorb the separated PsEVs at room temperature for 30 min. After blot-drying, the adsorbed grids were dyed. For 10 s, 2% aqueous uranyl acetate solution (81,405, SRL Chem) as negative staining. After blotting the grids, they were inspected using a Talos S transmission electron microscope (ThermoScientific, USA).

Western blot

Based on the initial volume of biofluid input, all samples were normalized, i.e., 180 μL and the sample loading dye (2 × Laemmle Sample buffer) was mixed with PsEVs sample, and 20 μL equal volume was loaded to run on an 8–12% SDS PAGE [ 53 , 55 ]. After the completion of SDS-PAGE, protein from the gel was subjected to the Wet transfer onto the PVDF membrane of 0.22 μm (1,620,177, BioRad). The membrane-blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (D0024, BioBasic) in Tris (TB0194, BioBasic) base saline containing 0.1% of Tween 20 (65,296, SRL Chem) (TBST) using the BioRad Western blotting apparatus (BioRad, USA). Following this, overnight incubation of primary antibodies of CD63 (10628D, Invitrogen), CD81 (PA5-86,534, Invitrogen), TSG101 (MA1-23,296, Invitrogen), L1CAM (MA1-46,045, Invitrogen), synaptophysin (ADI-VAM-SV011-D, Enzo life sciences), GFAP (A19058, Abclonal), amyloid-β (1–42) oligomer (AHB0052, Invitrogen), phospho-Tau (s396) (35–5300, Invitrogen), interleukin 1β (IL-1β) (PA5-95,455, Invitrogen), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (E-AB-33121, Elabscience), and β-actin (AM4302, Invitrogen) were done at 4 °C. The membranes were washed with TBST buffer four times before at RT incubating with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit (AB6721, Abcam), anti-mouse (31,430, Invitrogen). The Femto LUCENT™ PLUS-HRP kit (AD0023, GBiosciences) was used to develop the blot for visualizing the protein bands utilizing the method of enhanced chemiluminescence.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

According to the previous protocol, ELISA was carried out. [ 53 ]. PsEV samples were subjected to freeze–thaw cycles; next, PsEVs were ultrasonicated for two minutes, with a 30-s on-and-off cycle, at an amplitude of 25. Following this, they underwent a 10-min centrifugation at 10,000 g, at 4 °C, and the obtained supernatant was used. The samples were kept at 37 °C before loading into the ELISA plates. The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (23,225, ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to quantify the total protein concentration using BSA (D0024, BioBasic) as a reference. The ELISA kit was used to detect the presence of protein in 100 μL of PsEV sample are as follows: amyloid-β (1–42) (E-EL-H0543, ELabsciences), p-Tau (s-396) (E-EL-H5314, ELabsciences), IL-1β (ITLK01270, GBiosciences), TNF-α (ITLK01190, GBiosciences), GFAP (E-EL-H6093, ELabsciences), and synaptophysin (E-EL-H2014, ELabsciences). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed for every step of the process. A 96-well microplate spectrophotometer (SpectraMax i3x Multi-Mode Microplate Reader, Molecular devices) was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

Data and statistical analysis

The mean age values, ACE-III score, and MMSE score were ascertained using descriptive statistical analysis Table 1 . GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used for statistical data analysis, including NTA concentration, Western blotting densitometric analysis, and ELISA. Unpaired student t -test and ANOVA were used for group analysis, and statistical significance was determined. p < 0.05 was used to assess significance. The Image J software (NIH, USA) was used for the densitometry analysis. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the efficiency of distinguishing the case from controls. Correlation analysis was conducted between the concentration of PsEVs and the levels of ELISA proteins, including amyloid-β (1–42), p-Tau, IL-1β, TNF-α, GFAP, and synaptophysin, and additionally between the PsEVs-derived levels of amyloid-β (1–42) β1-42, p-Tau, IL-1β, TNF-α, GFAP, and synaptophysin with ACE-III and MMSE values. ROC curve is a probability curve utilized to assess the accuracy of a test. The test’s ability to distinguish between groups is indicated by the area under the curve (AUC), which acts as a quantitative measure of separability. An outstanding test typically exhibits an AUC close to 1, signifying a high level of separability. Conversely, a subpar test tends to have an AUC closer to 0, indicating a poor ability to distinguish between the two classes.

Characterization and validation of isolated sEVs

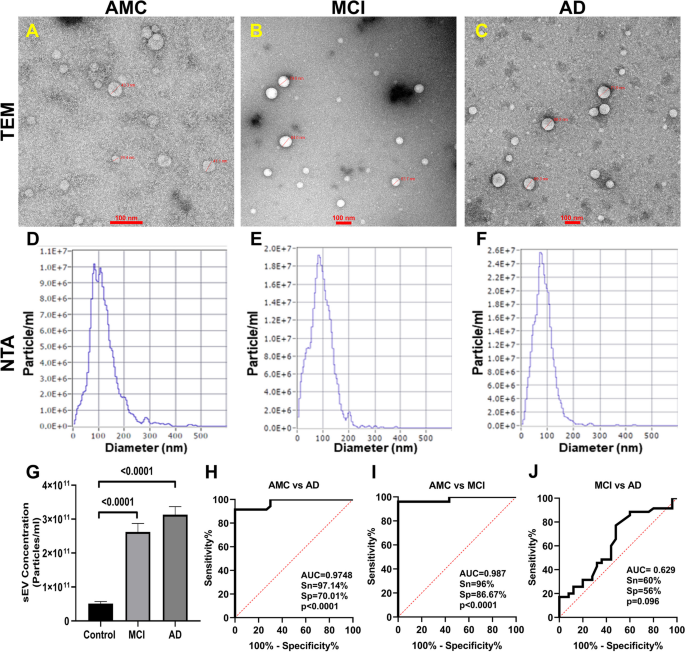

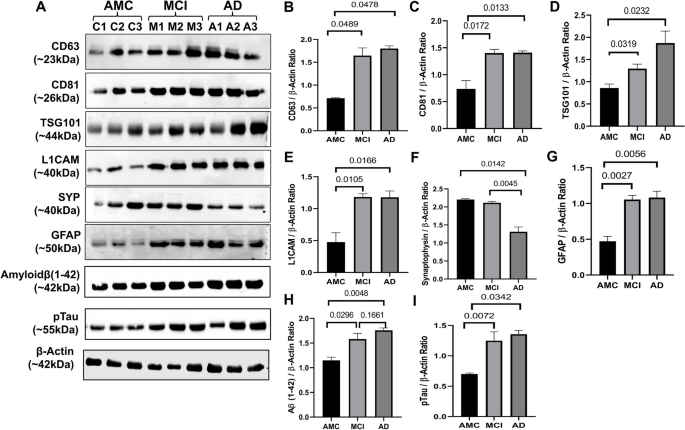

PsEVs were isolated, characterized, and validated following Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) 2018 guidelines, which suggest a protocol for documenting work specifically with extracellular vesicles [ 56 ]. PsEVs from AMC, MCI, and AD subjects were morphologically characterized by transmission electron microscopy, and spherical lipid bi-layered vesicles were observed in the size range of sEVs (Fig. 1 A–C). In Fig. 1 D–F, the size distribution and concentration of PsEVs were observed in the size range of 30–200 nm in diameter by NTA, which is within the sEVs’ size range. The mean concentration of PsEVs in AMC, MCI, and AD patients were 5.12E + 10, 2.6E + 11, and 3.13E + 11 particle/ml, respectively, with higher concentrations of PsEVs in MCI and AD than in AMC ( p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1 G). To differentiate AD from AMC, ROC and AUC analyses were performed where the AUC = 0.9748, with a sensitivity of 97.14% and specificity of 70.01% (Fig. 1 H), while in AMC versus MCI, AUC = 0.987, sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 86.67% (Fig. 1 I). Furthermore, we could also differentiate between MCI and AD, AUC = 0.629, sensitivity of 60%, and specificity of 56% (Fig. 1 J). Validation of PsEVs was done using immunoblot for sEVs-specific markers (CD63, CD81, and TSG101), which showed a significant increase in expressions in MCI and AD than in AMC (CD63, p = 0.0489, 0.0478 (Additional File 1 : Fig. S1); CD81, p = 0.0172, 0.0133 (Additional File 1 : Fig. S2); TSG101 p = 0.0240, 0.0329 (Additional File 1 : Fig. S3)) for AD and MCI respectively (Fig. 2 A–D). Additionally, higher L1CAM (neuron-associated marker) expression was observed in MCI ( p = 0.0100) and AD ( p = 0.0184) (Additional File 1 : Fig. S4) compared to AMC (Fig. 2 E). All densitometric values were normalized against β-actin, which was used as a loading control (Additional File 1 : Fig. S7).

Isolation and analysis of PsEVs. The isolated PsEV morphology characterize by transmission electron microscopy from age-matched healthy controls (AMC) ( A ), mild-cognitive impairment (MCI) patients ( B ), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) ( C ). The size distribution of PsEVs subpopulation (nm) versus the concentration (particle/ml) in AMC ( D ), individuals with MCI ( E ), and AD ( F ). Comparison of the sEVs concentration of AD, MCI, and AMC patients ( G ). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of PsEVs concentration in AMC v/s AD ( H ), AMC v/s MCI ( I ), and MCI v/s AD ( J ) (scale bar 100 nm)

Validation of PsEVs expression analysis of different markers in PsEVs in age-matched controls (AMC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer’s disease patients (AD) ( A ). Densitometric analysis of CD63 ( B ), densitometric analysis of CD81 ( C ), densitometric analysis of TSG101 ( D ), densitometric analysis of L1CAM ( E ), densitometric analysis of synaptophysin ( F ), densitometric analysis of GFAP ( G ), and densitometric analysis of amyloid-β (1–42) oligomer ( H ). All densitometric values were normalized against β-actin

Differential expression of amyloid-β (1–42), p-Tau, synaptophysin, GFAP markers, and levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in PsEVs

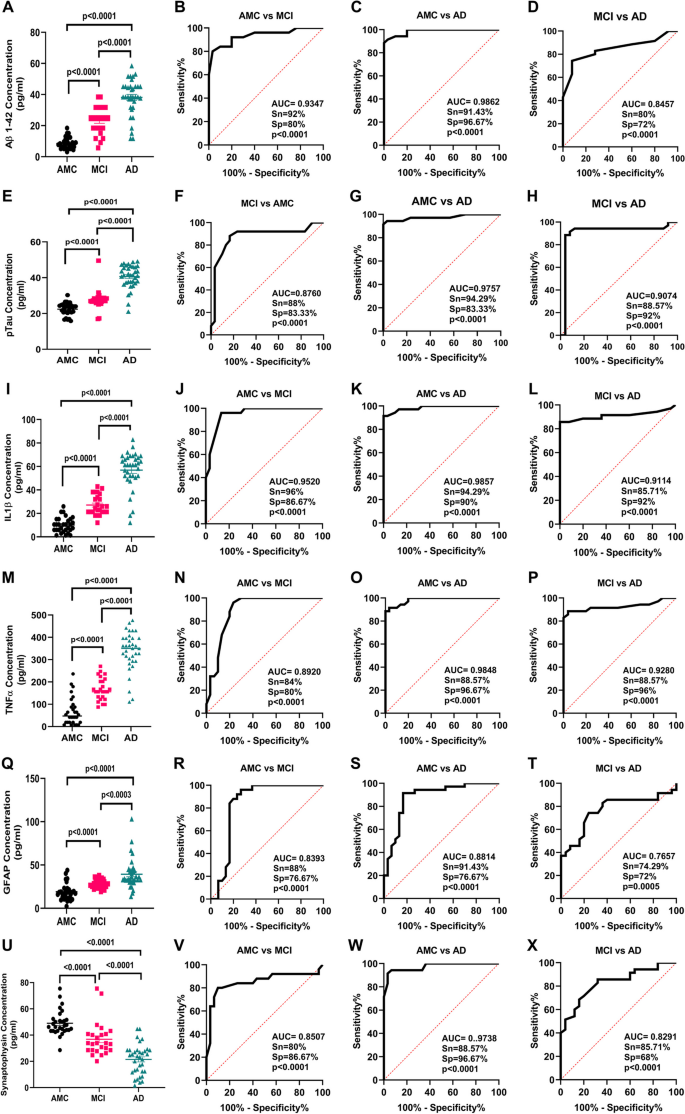

Using ELISA, we measured levels of amyloid-β (1–42) and p-Tau in PsEVs from AMC, MCI, and AD patients. The significant increase of amyloid-β (1–42) and p-Tau among the groups (Fig. 3 A–H). Amyloid-β (1–42) levels were higher in MCI compared to AMC ( p < 0.0001) and more significant in AD than in MCI and AMC ( p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3 A). Similarly, in comparison to MCI and AMC, p-Tau levels were significantly higher in AD ( p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3 E). Similar levels of both markers were found in their Western blots (Fig. 2 ). We checked GFAP (astrocytic marker) and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) to evaluate neuroinflammation. For proinflammatory markers, IL-1β and TNF-α levels showed a significant increase among the three groups ( p < 0.0001 for IL-1β and TNF-α) (Fig. 3 I, M). When comparing AD to MCI and AMC, the GFAP concentration in PsEVs was significantly higher ( p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3 Q). Similar trends were observed with Western blot analysis (Fig. 2 , Additional File 1 : Fig. S6, S9). Their elevated levels suggest prominent neuroinflammatory conditions contributing to potential neuronal damage. The elevated levels of these neuroinflammatory markers could be due to the activation of astrocytes and microglia and the subsequent increase in the secretion of PsEVs containing proinflammatory proteins, which suggests prominent neuroinflammatory conditions that may contribute to neuronal damage [ 57 ]. While synaptophysin concentration in PsEVs was downregulated in AD and MCI compared to AMC ( p < 0.0001) in ELISA (Fig. 3 U), it shows synaptic dysfunction. We also checked synaptophysin levels in PsEVs in Western blotting, finding it was downregulated in AD compared to MCI and AMC ( p = 0.0045, 0.0142), indicating synaptic degeneration in AD (Fig. 2 , Additional File 1 : Fig. S5). In MCI, synaptophysin levels did not significantly differ from AMC (Fig. 2 F). This aligns with synaptic loss in AD, reflected in lower neuropsychological test scores indicating more pronounced cognitive impairment compared to MCI and AMC.