- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Virtual onboarding.

How to Get Your New Hire on Board – Online

Book Insights

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

Daniel H Pink

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 2

NEW! Pain Points - How Do I Decide?

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Finding the Best Mix in Training Methods

Using Mediation To Resolve Conflict

Resolving conflicts peacefully with mediation

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Herzberg's motivators and hygiene factors.

Learn how to Motivate Your Team

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Case-based learning.

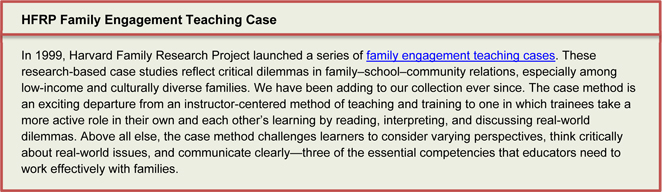

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios. The cases present a disciplinary problem or problems for which students devise solutions under the guidance of the instructor. CBL has a strong history of successful implementation in medical, law, and business schools, and is increasingly used within undergraduate education, particularly within pre-professional majors and the sciences (Herreid, 1994). This method involves guided inquiry and is grounded in constructivism whereby students form new meanings by interacting with their knowledge and the environment (Lee, 2012).

There are a number of benefits to using CBL in the classroom. In a review of the literature, Williams (2005) describes how CBL: utilizes collaborative learning, facilitates the integration of learning, develops students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn, encourages learner self-reflection and critical reflection, allows for scientific inquiry, integrates knowledge and practice, and supports the development of a variety of learning skills.

CBL has several defining characteristics, including versatility, storytelling power, and efficient self-guided learning. In a systematic analysis of 104 articles in health professions education, CBL was found to be utilized in courses with less than 50 to over 1000 students (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). In these classrooms, group sizes ranged from 1 to 30, with most consisting of 2 to 15 students. Instructors varied in the proportion of time they implemented CBL in the classroom, ranging from one case spanning two hours of classroom time, to year-long case-based courses. These findings demonstrate that instructors use CBL in a variety of ways in their classrooms.

The stories that comprise the framework of case studies are also a key component to CBL’s effectiveness. Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano (2002, p.66) describe how storytelling:

Is a method of negotiating and renegotiating meanings that allows us to enter into other’s realms of meaning through messages they utter in their stories,

Helps us find our place in a culture,

Allows us to explicate and to interpret, and

Facilitates the attainment of vicarious experience by helping us to distinguish the positive models to emulate from the negative model.

Neurochemically, listening to stories can activate oxytocin, a hormone that increases one’s sensitivity to social cues, resulting in more empathy, generosity, compassion and trustworthiness (Zak, 2013; Kosfeld et al., 2005). The stories within case studies serve as a means by which learners form new understandings through characters and/or scenarios.

CBL is often described in conjunction or in comparison with problem-based learning (PBL). While the lines are often confusingly blurred within the literature, in the most conservative of definitions, the features distinguishing the two approaches include that PBL involves open rather than guided inquiry, is less structured, and the instructor plays a more passive role. In PBL multiple solutions to the problem may exit, but the problem is often initially not well-defined. PBL also has a stronger emphasis on developing self-directed learning. The choice between implementing CBL versus PBL is highly dependent on the goals and context of the instruction. For example, in a comparison of PBL and CBL approaches during a curricular shift at two medical schools, students and faculty preferred CBL to PBL (Srinivasan et al., 2007). Students perceived CBL to be a more efficient process and more clinically applicable. However, in another context, PBL might be the favored approach.

In a review of the effectiveness of CBL in health profession education, Thistlethwaite et al. (2012), found several benefits:

Students enjoyed the method and thought it enhanced their learning,

Instructors liked how CBL engaged students in learning,

CBL seemed to facilitate small group learning, but the authors could not distinguish between whether it was the case itself or the small group learning that occurred as facilitated by the case.

Other studies have also reported on the effectiveness of CBL in achieving learning outcomes (Bonney, 2015; Breslin, 2008; Herreid, 2013; Krain, 2016). These findings suggest that CBL is a vehicle of engagement for instruction, and facilitates an environment whereby students can construct knowledge.

Science – Students are given a scenario to which they apply their basic science knowledge and problem-solving skills to help them solve the case. One example within the biological sciences is two brothers who have a family history of a genetic illness. They each have mutations within a particular sequence in their DNA. Students work through the case and draw conclusions about the biological impacts of these mutations using basic science. Sample cases: You are Not the Mother of Your Children ; Organic Chemisty and Your Cellphone: Organic Light-Emitting Diodes ; A Light on Physics: F-Number and Exposure Time

Medicine – Medical or pre-health students read about a patient presenting with specific symptoms. Students decide which questions are important to ask the patient in their medical history, how long they have experienced such symptoms, etc. The case unfolds and students use clinical reasoning, propose relevant tests, develop a differential diagnoses and a plan of treatment. Sample cases: The Case of the Crying Baby: Surgical vs. Medical Management ; The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide ; The Haemophilus Vaccine: A Victory for Immunologic Engineering

Public Health – A case study describes a pandemic of a deadly infectious disease. Students work through the case to identify Patient Zero, the person who was the first to spread the disease, and how that individual became infected. Sample cases: The Protective Parent ; The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker ; Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case. Sample cases: Mortgage Crisis Call (abstract) ; The Case of the Unpaid Interns (abstract) ; Police-Community Dialogue (abstract)

Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not. Sample cases: SELCO-Determining a path forward ; Project Masiluleke: Texting and Testing to Fight HIV/AIDS in South Africa ; Mayo Clinic: Design Thinking in Healthcare

Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater. Sample cases: David Geffen School of Drama

Recommendations

Finding and Writing Cases

Consider utilizing or adapting open access cases - The availability of open resources and databases containing cases that instructors can download makes this approach even more accessible in the classroom. Two examples of open databases are the Case Center on Public Leadership and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Case Program , which focus on government, leadership and public policy case studies.

- Consider writing original cases - In the event that an instructor is unable to find open access cases relevant to their course learning objectives, they may choose to write their own. See the following resources on case writing: Cooking with Betty Crocker: A Recipe for Case Writing ; The Way of Flesch: The Art of Writing Readable Cases ; Twixt Fact and Fiction: A Case Writer’s Dilemma ; And All That Jazz: An Essay Extolling the Virtues of Writing Case Teaching Notes .

Implementing Cases

Take baby steps if new to CBL - While entire courses and curricula may involve case-based learning, instructors who desire to implement on a smaller-scale can integrate a single case into their class, and increase the number of cases utilized over time as desired.

Use cases in classes that are small, medium or large - Cases can be scaled to any course size. In large classes with stadium seating, students can work with peers nearby, while in small classes with more flexible seating arrangements, teams can move their chairs closer together. CBL can introduce more noise (and energy) in the classroom to which an instructor often quickly becomes accustomed. Further, students can be asked to work on cases outside of class, and wrap up discussion during the next class meeting.

Encourage collaborative work - Cases present an opportunity for students to work together to solve cases which the historical literature supports as beneficial to student learning (Bruffee, 1993). Allow students to work in groups to answer case questions.

Form diverse teams as feasible - When students work within diverse teams they can be exposed to a variety of perspectives that can help them solve the case. Depending on the context of the course, priorities, and the background information gathered about the students enrolled in the class, instructors may choose to organize student groups to allow for diversity in factors such as current course grades, gender, race/ethnicity, personality, among other items.

Use stable teams as appropriate - If CBL is a large component of the course, a research-supported practice is to keep teams together long enough to go through the stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965).

Walk around to guide groups - In CBL instructors serve as facilitators of student learning. Walking around allows the instructor to monitor student progress as well as identify and support any groups that may be struggling. Teaching assistants can also play a valuable role in supporting groups.

Interrupt strategically - Only every so often, for conversation in large group discussion of the case, especially when students appear confused on key concepts. An effective practice to help students meet case learning goals is to guide them as a whole group when the class is ready. This may include selecting a few student groups to present answers to discussion questions to the entire class, asking the class a question relevant to the case using polling software, and/or performing a mini-lesson on an area that appears to be confusing among students.

Assess student learning in multiple ways - Students can be assessed informally by asking groups to report back answers to various case questions. This practice also helps students stay on task, and keeps them accountable. Cases can also be included on exams using related scenarios where students are asked to apply their knowledge.

Barrows HS. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3-12.

Bonney KM. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 16(1): 21-28.

Breslin M, Buchanan, R. (2008) On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design. Design Issues, 24(1), 36-40.

Bruffee KS. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and authority of knowledge. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Herreid CF. (2013). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science, edited by Clyde Freeman Herreid. Originally published in 2006 by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA); reprinted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) in 2013.

Herreid CH. (1994). Case studies in science: A novel method of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(4), 221–229.

Jonassen DH and Hernandez-Serrano J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

Krain M. (2016) Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 27(2), 131-153.

Lee V. (2012). What is Inquiry-Guided Learning? New Directions for Learning, 129:5-14.

Nkhoma M, Sriratanaviriyakul N. (2017). Using case method to enrich students’ learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1):37-50.

Srinivasan et al. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74-82.

Thistlethwaite JE et al. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34, e421-e444.

Tuckman B. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-99.

Williams B. (2005). Case-based learning - a review of the literature: is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med, 22, 577-581.

Zak, PJ (2013). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved from: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

- International

- Business & Industry

- MyUNB Intranet

- Activate your IT Services

- Give to UNB

- Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning

- Teaching & Learning Services

- Teaching Tips

- Instructional Methods

- Creating Effective Scenarios, Case Studies and Role Plays

Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays

Printable Version (PDF)

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course. See Research Findings on University Teaching Methods .

Typically you would use case studies, scenarios and role plays for higher-level learning outcomes that require application, synthesis, and evaluation (see Writing Outcomes or Learning Objectives ; scroll down to the table).

The point is to increase student interest and involvement, and have them practice application by making choices and receive feedback on them, and refine their understanding of concepts and practice in your discipline.

These types of activities provide the following research-based benefits: (Shaw, 3-5)

- They provide concrete examples of abstract concepts, facilitate the development through practice of analytical skills, procedural experience, and decision making skills through application of course concepts in real life situations. This can result in deep learning and the appreciation of differing perspectives.

- They can result in changed perspectives, increased empathy for others, greater insights into challenges faced by others, and increased civic engagement.

- They tend to increase student motivation and interest, as evidenced by increased rates of attendance, completion of assigned readings, and time spent on course work outside of class time.

- Studies show greater/longer retention of learned materials.

- The result is often better teacher/student relations and a more relaxed environment in which the natural exchange of ideas can take place. Students come to see the instructor in a more positive light.

- They often result in better understanding of complexity of situations. They provide a good forum for a large volume of orderly written analysis and discussion.

There are benefits for instructors as well, such as keeping things fresh and interesting in courses they teach repeatedly; providing good feedback on what students are getting and not getting; and helping in standing and promotion in institutions that value teaching and learning.

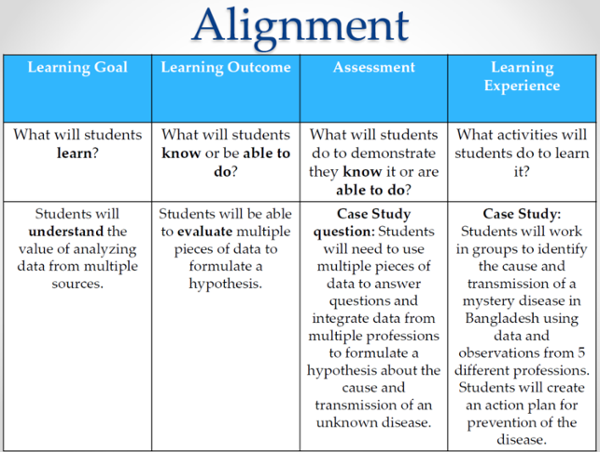

Outcomes and learning activity alignment

The learning activity should have a clear, specific skills and/or knowledge development purpose that is evident to both instructor and students. Students benefit from knowing the purpose of the exercise, learning outcomes it strives to achieve, and evaluation methods. The example shown in the table below is for a case study, but the focus on demonstration of what students will know and can do, and the alignment with appropriate learning activities to achieve those abilities applies to other learning activities.

(Smith, 18)

What’s the difference?

Scenarios are typically short and used to illustrate or apply one main concept. The point is to reinforce concepts and skills as they are taught by providing opportunity to apply them. Scenarios can also be more elaborate, with decision points and further scenario elaboration (multiple storylines), depending on responses. CETL has experience developing scenarios with multiple decision points and branching storylines with UNB faculty using PowerPoint and online educational software.

Case studies

Case studies are typically used to apply several problem-solving concepts and skills to a detailed situation with lots of supporting documentation and data. A case study is usually more complex and detailed than a scenario. It often involves a real-life, well documented situation and the students’ solutions are compared to what was done in the actual case. It generally includes dialogue, creates identification or empathy with the main characters, depending on the discipline. They are best if the situations are recent, relevant to students, have a problem or dilemma to solve, and involve principles that apply broadly.

Role plays can be short like scenarios or longer and more complex, like case studies, but without a lot of the documentation. The idea is to enable students to experience what it may be like to see a problem or issue from many different perspectives as they assume a role they may not typically take, and see others do the same.

Foundational considerations

Typically, scenarios, case studies and role plays should focus on real problems, appropriate to the discipline and course level.

They can be “well-structured” or “ill-structured”:

- Well-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can be simple or complex or anything in-between, but they have an optimal solution and only relevant information is given, and it is usually labelled or otherwise easily identified.

- Ill-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can also be simple or complex, although they tend to be complex. They have relevant and irrelevant information in them, and part of the student’s job is to decide what is relevant, how it is relevant, and to devise an evidence-based solution to the problem that is appropriate to the context and that can be defended by argumentation that draws upon the student’s knowledge of concepts in the discipline.

Well-structured problems would be used to demonstrate understanding and application. Higher learning levels of analysis, synthesis and evaluation are better demonstrated by ill-structured problems.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be authentic or realistic :

- Authentic scenarios are actual events that occurred, usually with personal details altered to maintain anonymity. Since the events actually happened, we know that solutions are grounded in reality, not a fictionalized or idealized or simplified situation. This makes them “low transference” in that, since we are dealing with the real world (although in a low-stakes, training situation, often with much more time to resolve the situation than in real life, and just the one thing to work on at a time), not much after-training adjustment to the real world is necessary.

- By contrast, realistic scenarios are often hypothetical situations that may combine aspects of several real-world events, but are artificial in that they are fictionalized and often contain ideal or simplified elements that exist differently in the real world, and some complications are missing. This often means they are easier to solve than real-life issues, and thus are “high transference” in that some after-training adjustment is necessary to deal with the vagaries and complexities of the real world.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be high or low fidelity :

High vs. low fidelity: Fidelity has to do with how much a scenario, case study or role play is like its corresponding real world situation. Simplified, well-structured scenarios or problems are most appropriate for beginners. These are low-fidelity, lacking a lot of the detail that must be struggled with in actual practice. As students gain experience and deeper knowledge, the level of complexity and correspondence to real-world situations can be increased until they can solve high fidelity, ill-structured problems and scenarios.

Further details for each

Scenarios can be used in a very wide range of learning and assessment activities. Use in class exercises, seminars, as a content presentation method, exam (e.g., tell students the exam will have four case studies and they have to choose two—this encourages deep studying). Scenarios help instructors reflect on what they are trying to achieve, and modify teaching practice.

For detailed working examples of all types, see pages 7 – 25 of the Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS) pdf .

The contents of case studies should: (Norton, 6)

- Connect with students’ prior knowledge and help build on it.

- Be presented in a real world context that could plausibly be something they would do in the discipline as a practitioner (e.g., be “authentic”).

- Provide some structure and direction but not too much, since self-directed learning is the goal. They should contain sufficient detail to make the issues clear, but with enough things left not detailed that students have to make assumptions before proceeding (or explore assumptions to determine which are the best to make). “Be ambiguous enough to force them to provide additional factors that influence their approach” (Norton, 6).

- Should have sufficient cues to encourage students to search for explanations but not so many that a lot of time is spent separating relevant and irrelevant cues. Also, too many storyline changes create unnecessary complexity that makes it unnecessarily difficult to deal with.

- Be interesting and engaging and relevant but focus on the mundane, not the bizarre or exceptional (we want to develop skills that will typically be of use in the discipline, not for exceptional circumstances only). Students will relate to case studies more if the depicted situation connects to personal experiences they’ve had.

- Help students fill in knowledge gaps.

Role plays generally have three types of participants: players, observers, and facilitator(s). They also have three phases, as indicated below:

Briefing phase: This stage provides the warm-up, explanations, and asks participants for input on role play scenario. The role play should be somewhat flexible and customizable to the audience. Good role descriptions are sufficiently detailed to let the average person assume the role but not so detailed that there are so many things to remember that it becomes cumbersome. After role assignments, let participants chat a bit about the scenarios and their roles and ask questions. In assigning roles, consider avoiding having visible minorities playing “bad guy” roles. Ensure everyone is comfortable in their role; encourage students to play it up and even overact their role in order to make the point.

Play phase: The facilitator makes seating arrangements (for players and observers), sets up props, arranges any tech support necessary, and does a short introduction. Players play roles, and the facilitator keeps things running smoothly by interjecting directions, descriptions, comments, and encouraging the participation of all roles until players keep things moving without intervention, then withdraws. The facilitator provides a conclusion if one does not arise naturally from the interaction.

Debriefing phase: Role players talk about their experience to the class, facilitated by the instructor or appointee who draws out the main points. All players should describe how they felt and receive feedback from students and the instructor. If the role play involved heated interaction, the debriefing must reconcile any harsh feelings that may otherwise persist due to the exercise.

Five Cs of role playing (AOM, 3)

Control: Role plays often take on a life of their own that moves them in directions other than those intended. Rehearse in your mind a few possible ways this could happen and prepare possible intervention strategies. Perhaps for the first role play you can play a minor role to give you and “in” to exert some control if needed. Once the class has done a few role plays, getting off track becomes less likely. Be sensitive to the possibility that students from different cultures may respond in unforeseen ways to role plays. Perhaps ask students from diverse backgrounds privately in advance for advice on such matters. Perhaps some of these students can assist you as co-moderators or observers.

Controversy: Explain to students that they need to prepare for situations that may provoke them or upset them, and they need to keep their cool and think. Reiterate the learning goals and explain that using this method is worth using because it draws in students more deeply and helps them to feel, not just think, which makes the learning more memorable and more likely to be accessible later. Set up a “safety code word” that students may use at any time to stop the role play and take a break.

Command of details: Students who are more deeply involved may have many more detailed and persistent questions which will require that you have a lot of additional detail about the situation and characters. They may also question the value of role plays as a teaching method, so be prepared with pithy explanations.

Can you help? Students may be concerned about how their acting will affect their grade, and want assistance in determining how to play their assigned character and need time to get into their role. Tell them they will not be marked on their acting. Say there is no single correct way to play a character. Prepare for slow starts, gaps in the action, and awkward moments. If someone really doesn’t want to take a role, let them participate by other means—as a recorder, moderator, technical support, observer, props…

Considered reflection: Reflection and discussion are the main ways of learning from role plays. Players should reflect on what they felt, perceived, and learned from the session. Review the key events of the role play and consider what people would do differently and why. Include reflections of observers. Facilitate the discussion, but don’t impose your opinions, and play a neutral, background role. Be prepared to start with some of your own feedback if discussion is slow to start.

An engineering role play adaptation

Boundary objects (e.g., storyboards) have been used in engineering and computer science design projects to facilitate collaboration between specialists from different disciplines (Diaz, 6-80). In one instance, role play was used in a collaborative design workshop as a way of making computer scientist or engineering students play project roles they are not accustomed to thinking about, such as project manager, designer, user design specialist, etc. (Diaz 6-81).

References:

Academy of Management. (Undated). Developing a Role playing Case Study as a Teaching Tool.

Diaz, L., Reunanen, M., & Salimi, A. (2009, August). Role Playing and Collaborative Scenario Design Development. Paper presented at the International Conference of Engineering Design, Stanford University, California.

Norton, L. (2004). Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS): A practical introduction to problem-based learning using vignettes for psychology lecturers . Liverpool Hope University College.

Shaw, C. M. (2010). Designing and Using Simulations and Role-Play Exercises in The International Studies Encyclopedia, eISBN: 9781444336597

Smith, A. R. & Evanstone, A. (Undated). Writing Effective Case Studies in the Sciences: Backward Design and Global Learning Outcomes. Institute for Biological Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Campus Maps

- Campus Security

- Careers at UNB

- Services at UNB

- Conference Services

- Online & Continuing Ed

Contact UNB

- © University of New Brunswick

- Accessibility

- Web feedback

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

bok_logo_2-02_-_harvard_left.png

Case Study At-A-Glance

A case study is a way to let students interact with material in an open-ended manner. the goal is not to find solutions, but to explore possibilities and options of a real-life scenario..

Want examples of a Case-Study? Check out the ABLConnect Activity Database Want to read research supporting the Case-Study method? Click here

Why should you facilitate a Case Study?

Want to facilitate a case-study in your class .

How-To Run a Case-Study

- Before class pick the case study topic/scenario. You can either generate a fictional situation or can use a real-world example.

- Clearly let students know how they should prepare. Will the information be given to them in class or do they need to do readings/research before coming to class?

- Have a list of questions prepared to help guide discussion (see below)

- Sessions work best when the group size is between 5-20 people so that everyone has an opportunity to participate. You may choose to have one large whole-class discussion or break into sub-groups and have smaller discussions. If you break into groups, make sure to leave extra time at the end to bring the whole class back together to discuss the key points from each group and to highlight any differences.

- What is the problem?

- What is the cause of the problem?

- Who are the key players in the situation? What is their position?

- What are the relevant data?

- What are possible solutions – both short-term and long-term?

- What are alternate solutions? – Play (or have the students play) Devil’s Advocate and consider alternate view points

- What are potential outcomes of each solution?

- What other information do you want to see?

- What can we learn from the scenario?

- Be flexible. While you may have a set of questions prepared, don’t be afraid to go where the discussion naturally takes you. However, be conscious of time and re-focus the group if key points are being missed

- Role-playing can be an effective strategy to showcase alternate viewpoints and resolve any conflicts

- Involve as many students as possible. Teamwork and communication are key aspects of this exercise. If needed, call on students who haven’t spoken yet or instigate another rule to encourage participation.

- Write out key facts on the board for reference. It is also helpful to write out possible solutions and list the pros/cons discussed.

- Having the information written out makes it easier for students to reference during the discussion and helps maintain everyone on the same page.

- Keep an eye on the clock and make sure students are moving through the scenario at a reasonable pace. If needed, prompt students with guided questions to help them move faster.

- Either give or have the students give a concluding statement that highlights the goals and key points from the discussion. Make sure to compare and contrast alternate viewpoints that came up during the discussion and emphasize the take-home messages that can be applied to future situations.

- Inform students (either individually or the group) how they did during the case study. What worked? What didn’t work? Did everyone participate equally?

- Taking time to reflect on the process is just as important to emphasize and help students learn the importance of teamwork and communication.

CLICK HERE FOR A PRINTER FRIENDLY VERSION

Other Sources:

Harvard Business School: Teaching By the Case-Study Method

Written by Catherine Weiner

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.