- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

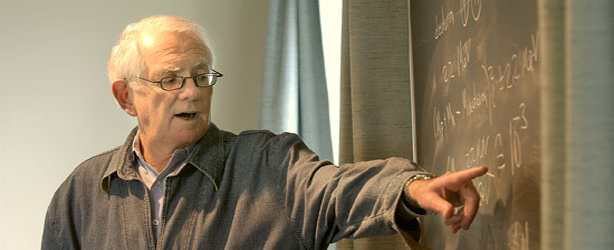

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

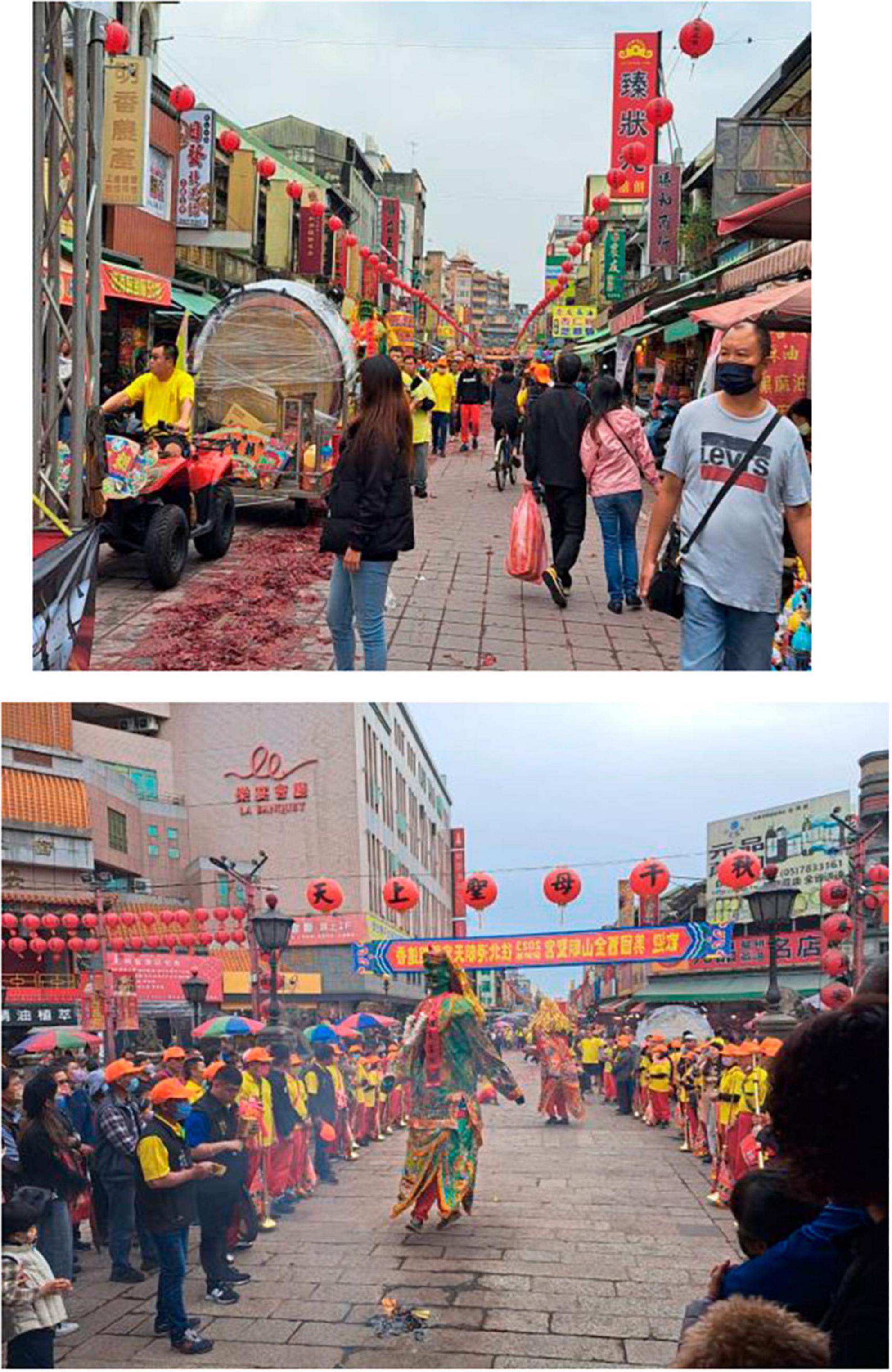

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: http://tlt.its.psu.edu/suggestions/cases/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the University of Buffalo.

Dunne, D. and Brooks, K. (2004) Teaching with Cases (Halifax, NS: Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education), ISBN 0-7703-8924-4 (Can be ordered at http://www.bookstore.uwo.ca/ at a cost of $15.00)

- Prospective Members

Making and Using Case Studies in the Classroom

naspaa tpac 2020 case study workshop.

Learn how to Teach With Case Studies and Make Your Own

Click below to check out an article on competency-based portfolios

Article: Case Studies Pedagogy

Download the slideshow presentation used by Blue Wooldridge:

Slide Show: A Strategic Contingency Approach to Instructional Design

Download the slideshow presentation used by Andrew Graham:

Slide Show: Case Study Formats and Learning Objectives

Special Thanks

Blue Wooldridge

Virginia Commonwealth University

Andrew Graham

Queen's University

Kathy Brock

We at NASPAA would like to give a big thank you to our amazing presenters!

If you have any questions about our training modules or about how you can attend our next conference, please feel free to reach out to us at [email protected]

An identity project: a case study of two inservice elementary stem teachers’ experiences with a comprehensive professional development

- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2024

- Volume 3 , article number 63 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Carolyn A. Parker 1 &

- Nicholas Lehn 1

85 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper describes the experiences of two teachers, Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik, who participated in a comprehensive National Science Foundation-supported science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) professional learning experience. This comparative case study describes how Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik leveraged the justice-oriented curriculum of a STEM professional learning opportunity to transform their identities as educators while influencing their instructional practices. The professional learning experience included access to a justice-oriented curriculum introduced through monthly content-focused experiences, regular faculty learning communities, and support from an expert onsite coach. Evidence of transformed identities and instructional practices is derived from semi-structured in-depth interviews and video recordings of classroom teaching and learning. Analysis of the interview data suggests that Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik found the professional learning experience transformative and that the experience served as a pedagogical identity project. Evidence from the classroom videos suggests that Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s instructional practices shifted, becoming more justice-oriented and student-centered. Moreover, Ms. Santiago’s practices shifted in a manner more aligned with an engaged teaching approach. We conclude that the comprehensive STEM professional learning experience served as a pedagogical identity project while positively influencing the instructional practices of Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik. Implications for preservice and in-service teacher education are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Constructivism—Jerome Bruner

“You Never Told Me”: The Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) of Israel Education

The impacts of covid-19 on early childhood education: capturing the unique challenges associated with remote teaching and learning in k-2.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Public schools in Baltimore City have long strived to meet their students’ needs under the weight of societal obstacles contributing to socioeconomic reproduction, including systemic racism and violence [ 23 ]. This weight was exemplified by the 2015 death of Freddie Gray and the nationally televised riots that followed. Contrary to how mass media portrayed the City's youth during this challenging time, Baltimore-based sociologists DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist, and Edin [ 8 ] found that the majority of young people growing up in Baltimore actively resist pernicious stereotypes of involvement in drugs and violence by pursuing post-secondary education and careers. This finding was supported by the authors of Coming of Age in the Other America who also found that many young people in Baltimore graduated from high school, and went on to higher education or found jobs, further rejecting the stereotype that “poor children growing up in Baltimore are less likely to escape poverty than those growing up in any other city in the nation,” [ 8 ], p. xv]. Students who successfully overcame these obstacles were able to break free of the “legacy of deep racial subjugation, intergenerational poverty, and resource-depleted neighborhoods” and often engaged with what the authors termed an “identity project,” a consuming passion that acted as a life raft and helped students transcend daily challenges and hardships [ 8 , p. 11].

In this paper, we extend and apply the localized work of DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist, and Edin [ 8 ] through a comparative case-study approach examining the professional identity transformation of two Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS) elementary school teachers, Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik. Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik participated in a five-year, comprehensive, professional learning program supported by a National Science Foundation Mathematics and Science Foundation partnership, STEM Achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools (SABES), which through their participation became an identity project, supporting them to transform their instructional practices and enact a or more engaged, justice-oriented approach with their students.

1.1 STEM achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools (SABES)

SABES was established in 2012 as a community partnership initiative focused on grades 3–5 between BCPS and The Johns Hopkins University Whiting School of Engineering. The project focused on three distinct Baltimore neighborhoods, the Pimlico/Arlington/Hilltop area, the Greater Charles Village/Barclay region, and the Highlandtown neighborhood. SABES provides a student-centered, justice-centered science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) curriculum for grades 3–5 [ 30 , 32 ]. A comprehensive and intensive professional learning experience support the teachers who adopt SABES’ justice-centered curriculum and includes subject-specific coursework, grade-level collaborative professional learning communities, and in-school coaching by an expert science coach.

Our analysis of interviews and classroom observations with Ms. Santiago and Ms. Jelenik indicates their involvement with SABES’ comprehensive professional learning program served as a pedagogical identity project, consuming their professional lives while transforming their identity as educators. Subsequently their identity transformation fueled a change in their instructional practices to what bell hooks [ 16 ] described as engaged teaching, especially for Ms. Santiago.

1.2 Baltimore City Public Schools

Researchers have found that economically impoverished school districts like Baltimore City Public Schools (BCPS) often face many challenges, such as chronic shortages of experienced educators, low student achievement on standardized measures, and a lack of financial resources [ 12 , 13 , 17 , 23 , 30 ]. BCPS is no exception. BCPS serves approximately 85,000 students, eighty-four percent of whom are eligible for free- or reduced-price meals, a marker of poverty in Maryland. Pre-pandemic data from the 2019 Nation’s Report Card [ 27 ] tell a story of a challenged district. The average score on the National Assessment of Education Progress of eighth-graders who attend BCPS was 243, fifteen points lower than the average score of 258 for public schools in other large cities. BCPS’s students' academic achievement is among the lowest in Maryland. In science, in 2019, only 7.2% of students scored at or above proficient on the state’s fifth-grade science test, compared to 29.1% of students statewide [ 27 ].

Moreover, following national trends, science in elementary schools is greatly deemphasized. According to the most recent National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education [ 3 ] of 7600 science and mathematics teachers across the United States, students in elementary classrooms spent an average of 20 min per day on science far less than the 87 or 58 min per day spent on reading or mathematics, respectively.

However, contrary to the national narrative of diminished science instruction, the two teachers in our comparative case study, Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik, embraced teaching the SABES justice-oriented STEM curriculum to their elementary-aged students and used the comprehensive professional learning experience to transform their professional identities and instructional practices. This assertion is supported by data from six transcribed interviews, 31 video recordings of their classroom STEM instruction (totaling 16 h of footage), and field notes. The evidence indicates that both teachers enacted the justice-oriented curriculum while incorporating the tenets of SABES professional learning in ways compatible with an identity project [ 8 ]. Moreover, the instructional transformation, particularly for Ms. Santiago, was compatible with what bell hooks [ 16 ] described as engaged teaching, teaching “in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students [ 16 , p. 13]”.

2 Literature review

2.1 educator identity.

A teacher’s identity influences how they enact instruction, influences their professional learning, and their career trajectory [ 36 ]. Within the domain of science, teacher identity is uniquely contextual [ 9 ]. By studying science teacher identity, we can better prepare and support teachers to teach science at the elementary and secondary classroom.

Teacher identity can be described in a multitude of ways. Darragh [ 7 ] divides identity into five categories: participative, narrative, discursive, psychoanalytic, and performative. Gee [ 10 ] describes four ways to view identity: nature-identity, institution-identity, discourse identity, and affinity-identity. It is important to note that one’s identity is complex, and no matter how a researcher categorizes identity, the categories cannot be thought of as separate from one another. We must consider categories of identity as related and influenced by one another.

Our study is primarily guided by what Darragh [ 7 ] describes as participative identity. In particular, participative identity as constructed through participation and engagement in a social group. This definition of participative identity builds on Lave and Wenger’s [ 19 ] and Wenger’s [ 38 ] notion of “communities of practice within which one’s participative identity is situated; “a layering of events of participation and reification by which our experience and its social interpretation inform each other” [ 38 , p. 151].

Very recently, Chen and Mensah [ 5 ] incorporated Lave and Wenger [ 19 ] as well as Wenger [ 38 ] situated learning theoretical framework in their examination of science teachers. Chen and Mensah [ 5 ] poisted that participation within a CoP supported the development of a science teacher identity while developing the knowledge and skills necessary to teach. As their teaching practices and participation in the CoP developed, their study’s participants became part of their science teaching community while developing an increased sense of identity as science teachers.

Holland et al.’s [ 15 ] identity and agency in cultural, figured worlds framework describes the process of identity development with figured worlds or socially constructed frames of reference. The framework provides a perspective for how individuals navigate their cultural and social environment, drawing from cultural models to construct one’s identity while exercising individual agency. The process is active. The individual actively engages with their cultural and social environment, constructing a figured world through interaction governed by cultural norms, social structures, and power dynamics.

Moore utilized Holland et al. [ 15 ] to frame the development of three African American science teachers’ identities. This framework helped guide a more personalized and individual understanding of each teacher informed by their experiences in culturally constructed worlds (e.g., race, gender, class, ethnicity, age, and religion), their classroom practices, and their professional learning, helping to develop assertions on how each teacher negotiated power and their roles as science teachers.

Teacher identity frameworks share the complex and contextualized nature of teacher identity development. Each framework emphasizes the importance of social interactions in identity development, mainly when situated within a teacher’s immediate school context. Each framework also emphasized the ever-changing nature of identity development. Educator identity is not static and is heavily influenced by context. In our study, participation is an all-encompassing professional development experience [ 2 ].

2.2 Justice-centered science curriculum and pedagogy

In the context of STEM education, Basu and Calabrese-Barton [ 4 ] incorporated the ideas of socially just teaching in their exploration of how implementing democratic science pedagogy and curriculum can transform a secondary science classroom. They state that a goal of “democratic science pedagogy is to explore ways of teaching science for social justice among diverse school populations by drawing on the ideas and assets of students and teachers” [ 4 , p. 72]. Through interviews, focus groups, analysis of artifacts, and classroom observations, six teachers and twenty-one students expressed differing interpretations of what a classroom's democratically active science instruction could look like. Students described three common concepts of democratic science pedagogy: freedom and choice, community and caring, and leadership. They went on to express the need for the classroom to be caring, friendly, and peaceful. Basu and Calabrese-Barton [ 4 ] provided general examples of teachers’ and students' ideas for a democratic science classroom that included supporting students’ funds of knowledge and valuing students’ voices, which they believe may enhance student motivation and desire to learn. SABES curriculum was justice-oriented because it drew for the assets of each neighborhood SABES served. For example, the Highlandtown area of Baltimore City has experienced rapid growth of emerging English language students, primarily from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. SABES intentionally incorporated lessons that would draw on the ideas of students from Central America. The curriculum supported pedagogy was student centered, specifically instructional practices that supported student discourse and discussion [ 24 , 28 ].

Through the lens of critical ethnography, Seiler and Gonsalves [ 34 ] worked with two teacher candidates co-teaching in a high school in West Philadelphia. Guided by the words, “We can learn whatever you want in science” [ 35 , p. 90], and by student interest and input, the two teacher candidates worked with their students to co-develop the course curriculum. They predicted that student agency would improve through a participatory, democratic process. Finding the role of a decentralized facilitator challenging, two co-teachers expressed that when they were viewed as facilitators of instruction by their students, they felt that student agency improved. Seiler and Gonsalves [ 35 ] concluded that teachers could establish a facilitator role during science teaching by incorporating a more liberation-oriented approach in a classroom. The SABES curriculum not only includes topics readily encountered in Baltimore, but is very student-centered, supporting the students to explore science while the teacher serves as a facilitator, aligning to what Seiler and Gonsalves described as a participatory and democratic process and pedagogy.

Aligned to the work of Seiler and Gonsalves [ 35 ], Morales-Doyle [ 26 ] found that science teachers becoming classroom facilitators also help correct long-standing inequalities in science education by empowering students to become transformative change agents via embracing justice-centered science pedagogy. Embedded within both critical theory and Ladson-Billings’ [ 18 ] culturally relevant pedagogy, Morales-Doyle describes justice-centered science pedagogy as a framework where students must experience academic success, develop cultural competence, and develop a critical consciousness through relevant, Baltimore-centric curriculum and more student-centered pedagogies. He positions justice-centered science pedagogy as one way to challenge oppression by addressing inequality in science education. Morales-Doyle [ 26 ] identifies a need for studies that focused on empirical analyses of socially transformative science education in urban school settings. Our study and this paper fills this need as identified by Morales-Doyle.

Chen and Mensah [ 5 ] and Varelas, Segura, Bernal‐Munera, and Mitchener [ 37 ] examines the interaction between teacher identity and more inclusive, justice-focused pedagogy and found that a social justice orientation is influenced by the larger institutional context and more local school-based context of each educator. Moreover, the design of science professional learning along with a more student-centered, justice-oriented curriculum are effective in supporting teachers to transform their science teacher identities. Our study extends the work of Chen and Mensah [ 5 ] and Varelas, Segura, Bernal‐Munera, and Mitchener [ 37 ] by examining the confluence of a justice-centered elementary STEM curriculum to transform the science teaching identities and the instructional practices of two Baltimore City elementary teachers.

3 Theoretical framework

Our theoretical framework of a justice-focused approach supports us to understand the factors influencing our study’s two participants interaction with SABES science curriculum and professional learning, the two teachers science teaching identity, and their instructional practices.

3.1 Science teacher identity: Lave and Wenger’s (1991) situated learning theory and Wenger’s (1998) Communities of Practice (CoP)

Situated learning theory guides identity formation, according to Lave and Wenger [ 19 ]. Situated learning theory includes the following key tenets: (a) Legitimate peripheral participation that supports the novice learner to participate in meaningful peripheral participation. This means that over time, the novice learner becomes more and more involved in the community’s activities. As the novice learner becomes more involved, the individual transitions from a more novice learner to a more active and expert participant. During this transition from novice to expert, the individual's identity is shaped; (b) A connection between learning and the individual's identity. Engagement with the CoP must shape and form the individual’s identity; (c) Each learner, through participation in and interaction with the CoP develops a sense of belonging, negotiating their role while shaping and reshaping their identity; (d) Identity Negotiation: AS the individual interacts with the CoP, they iteratively negotiate their role in the CoP and their identity. By participating in the CoP and interacting with other learners, participants develop an identity fundamentally a part of the collective identity of the CoP [ 37 ].

3.2 Engaged teaching

In Teaching to Transgress (1994), bell hooks [ 16 ] describes the development of the ideas of engaged pedagogy as a means to overcome the “overwhelming boredom, uninterest, and apathy” [ 16 , p.10] that she feels characterizes the way that professors and students felt about their teaching and learning experiences. Drawn from anti-colonialist, critical, feminist, and multicultural theories, hooks [ 16 ] describes engaged teaching as “not merely to share information but to share in the intellectual and spiritual growth of our students. To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin [ 16 , p. 13].” She believes that engaged teaching is much more demanding than conventional, critical, or feminist pedagogies because of the emphasis on both teachers' and students’ well-being. “Teachers must be actively committed to a process of self-actualization that promotes their well-being if they are to teach in a manner that empowers the student. [ 16 , p. 15].” While traditional education is often delivered in a way that is disengaged from real life, hooks believes that students want a relevant and meaningful education. Engaged pedagogy focuses on empowering teachers and students in a process that connects to and enriches their lives. When connecting lives, the knowledge supports a more profound and sustained academic engagement. Socially just teaching emphasizes improving the learning and life opportunities of typically marginalized students.

4 Research context and methodology

Our comparative case study with Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik and their classrooms is part of the broader work of SABES. Although SABES’s research agenda does not explicitly focus on individual teachers, as we analyzed our data, Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s prolonged and seemingly transformative engagement with SABES could not be overlooked. Therefore, we delved deeper into their interviews and classroom observations and explored the following three research questions, developing a case study for each teacher.

How did Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik describe the change in their educational identity as they experienced SABES?

How did Ms. Santiago and Ms. Jelenik enact SABES’s justice-oriented approach with their students?

How did Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s embrace of SABES's justice-oriented STEM approach support engaged teaching, as described by bell hooks [ 16 ]?

4.1 Context of the study

SABES is driven by the belief that a justice-oriented elementary STEM teaching, guided by rigorous curriculum documents, must also be authentic, student-centered, and reflective of individual teachers’ beliefs. SABES includes an in-school curriculum, teacher professional learning, a neighborhood-focused afterschool program, and community events. SABES required that participating schools commit to teaching STEM to grade 3–5 students for an average of at least forty-five minutes each day [ 30 , 32 ].

There are three ways that SABES engages directly with students. In school, students are taught with a Baltimore-centric STEM curriculum. The curriculum draws from the wealth of knowledge in Baltimore City and includes units on the Chesapeake Bay, water quality (lead pipes is a huge issue in Baltimore City) and other salient and local topics. In an afterschool setting, students engage in a program that focuses on long-term, problem-based, student-directed projects that integrate STEM principles, particularly engineering, in ways relevant to their lives and communities [ 29 , 32 ]. For example, at the time of this study, one group of students identified the need to develop a low-cost and accessible way to decrease the amount of lead in their school’s water fountains. This spurred the students to explore water filters. Although the students’ solutions were not logistically feasible to adopt across the schools of Baltimore City, the students learned a tremendous amount about filters, and the topic was identified and explored by the students. The adults facilitated their exploration. Finally, community-based organizations help organize local STEM events for SABES that bring teachers, students, families, other community members, and university-based partners together to collaboratively learn about local STEM topics, while celebrating students’ projects, increasing family awareness and enhancing interest in STEM and STEM careers.

Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s professional learning experiences included STEM Academies; courses designed to teach STEM content knowledge aligned to the project’s elementary STEM curriculum. SABES offers three content-specific academies: physical science, earth and space science, and life science. Each STEM Academy consists of twelve two-and-a-half-hour sessions held every other week during the academic school year. Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik completed all three content-specific STEM academies.

Moreover, SABES aims to develop master teachers to lead STEM academies in building elementary science teaching capacity in the district and ensuring continued professional learning beyond the grant's lifetime. As SABES matured and Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik became more involved, they served as master teachers, leading and teaching several STEM Academies.

4.2 Ms. Santiago and Ms. Jelenik

Our study participants, Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik, teach at Flint Hill Elementary/Middle School. Flint Hill School has a predominantly African-American student population (89.79%), a 93.40% attendance rate, and 79.10% of students receiving free and reduced meals, a marker of poverty in Maryland. Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik have been involved in SABES since it was implemented in the school district in 2012.

Ms. Santiago identifies as female and Latinx. She was in her mid-20 s and was relatively new to teaching when the program began in 2012. Originally from California, she moved to Baltimore after graduating from UC Berkeley as a general education elementary teacher. Ms. Santiago became a teacher at her current school, which is only a few blocks from the university. She initially taught 4th and 5th grade before becoming her school’s middle school engineering teacher and STEM Coordinator.

Mr. Jelenik identifies as male and White. He has been teaching at Flint Hill School for 16 years. He went to a Baltimore-based university for his undergraduate degree. One summer, while he was still in college, he joined a university-sponsored program offered to help close the summer learning gap for lower-income students. He was placed at Flint Hill Academy that summer, and they offered him a job teaching math and reading upon graduation. Mr. Jelenik also began an elementary school basketball program at his school.

Finally, the first author, Carolyn Parker identifies as a White female who has worked in STEM education for almost 30 years. Her teaching and research have been situated within the greater Washington-Baltimore area and have focused on inclusive STEM education in K-12 schools. Nicholas Lehn, the second author, is in his early 30 s, a self-identified White male with a master's degree who grew up in the suburbs within the greater Washington-Baltimore area where SABES was implemented.

4.3 Research methods

Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik participated in six interviews and focus groups from January 2015 to September 2016, which were transcribed. Two researchers coded these transcriptions, emphasizing how the two teachers’ view of elementary STEM education in a high-poverty urban setting changed as SABES was implemented. The interviews were also coded based on how each teacher’s identity as an elementary STEM teacher was transformed via their participation in SABES. Guided by our research questions and in the tradition of grounded theory, we utilized constant comparative analysis [ 34 ].

In addition to the interviews, thirteen classroom periods of science instruction (8 of Mr. Jelenik and 5 of Ms. Santiago) were observed, and video and audio were recorded between October 2014 and December 2016, totaling 16 h of recorded observation. Utilizing a similar technique as Gamez and Parker [ 11 ], we watched each video, taking notes to develop a data repository for each teacher and class. We focused on the instructional topic and how Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik structured the learning activities. These classroom observations were also coded based on how each teacher enacted pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), facilitated STEM learning, fostered students’ finding their voice in the classroom, facilitated prosocial student–student interactions in group settings, and used local or more student-friendly localized touchstones in their lessons. These codes provided empirical evidence of the implementation of the hands-on STEM curriculum and the identity transformation of Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik described in the case studies.

The protocol for our study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board based on the institution's ethical standards and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

5 STEM achievement in Baltimore Elementary Schools as an identity project

As we explored how SABES supported Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s adoption of SABES’s approach to STEM teaching, we found that both Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik valued the role SABES played in their teaching and the lives of their students. SABES’s innovative curriculum and professional learning serve as an identity project for the two teachers. Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik’s involvement became a participative identity project [ 7 , 8 ], an all-consuming passion that focused their teaching constructed through participation and engagement in a social group; a community of practice [ 19 , 37 ]. This identity project, situated within the context of a community of practice of science teachers [ 5 ], helped Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelinek “transcend daily challenges and hardships” [ 8 , p. 11] of teaching in a high-poverty urban setting. SABES transformed Ms. Santiago's and Mr. Jelinek’s teaching identity from a more teacher-centered approach to a more student-centered approach aligned with bell hooks' concept of socially just teaching in the elementary classroom.

5.1 Ms. Santiago—educating future engineers

SABES professional learning gave Ms. Santiago her first exposure to an elementary, comprehensive STEM approach. Ms. Santiago often tells her students that she never knew about engineering growing up. She “never knew about the career in my elementary, middle school, high school, nothing… [she] had friends [in college] who were engineering majors, but still technically did not even know what [her]friends were majoring in” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016).

Ms. Santiago identified so fully with SABES that had she been exposed to STEM classes growing up, she “would have been an engineer. Point blank. It suits [her] personality. It is fun, I would have been an engineer had somebody exposed me to it” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016).

She reflects that for her, “science and throwing science in with STEM has become, literally, my entire life” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). This statement strongly aligns with both Suarez & McGrath’s [ 36 ] idea that a teacher’s identity reflects their instruction, professional learning, and career trajectory as well as two of Gee’s [ 10 ] four descriptions of identity: discourse-identity and affinity-identity. Ms. Santiago grew with SABES, saying she joined:

The summer after my very first year of teaching. Then, I jumped straight into STEM academies. I then jumped into the STEM certificate with the IHE associated with SABES while finishing my last STEM academy on top of Professional Learning Communities (PLC) and curriculum and everything else. But you know what? I love it all. The amount that I have learned is literally a college degree's worth, in my opinion. I did not have any of the science knowledge that I had. (Focus Group, September 28, 2016)

Her statement clearly demonstrates that the strength of SABES's justice-oriented curriculum, comprehensive professional learning support, and the STEM certificate have not only amounted to “a college degree’s” worth of knowledge but have completely shaped her career trajectory. Her “sole mission” as a teacher has become “creating engineers…. I tell them all the time, I want to see their names, somewhere in the future, creating something that solves some sort of world problem. Where I can… be like, ‘I taught that kid” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). This supports bell hooks concept of engaged teaching, truly caring for the success and well-being of her students [ 16 ].

Ms. Santiago describes how participation in SABES transformed her teaching in general and the impact it had on the structure and values of the school itself. With regards to the impact SABES had on her pedagogy outside of STEM, Ms. Santiago concludes that being “introduced to STEM and SABES so early on in [her] teaching career” shaped the way she teaches her “other subjects… and the kind of student-centered classroom approach that I taught [is] because of the curriculum” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). This effect on broader identity shaping her approach to pedagogy outside of STEM is a reflection of her deepened identity as a science teacher as described by Chen and Mensah [ 5 ] and Suarez & McGrath [ 36 ].

SABES has also transformed the school itself, as Ms. Santiago believes that her school would not have any life science or engineering programs if it were not for SABES. This transformation was not only curricular as Flint Hill School now has a state-of-the-art engineering classroom and laboratory funded and built with support from JHU’s Whiting School of Engineering.

Ms. Santiago’s investment in and identification with SABES extended even further beyond teaching STEM, or STEM influencing how she taught non-STEM subjects, to the point of giving up her planning periods to teach it and her summer break to create and revise SABES’s curriculum. This all-encompassing investment and identification with SABES is, as Ms. Santiago describes, felt by her students as well. She described days when she “hated going to resource” because her students wanted to “stay and finish science” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). The fact that Ms. Santiago was readily willing to give up her planning period so that her students could spend more time learning STEM reflects her investment in the curriculum and mission of SABES. Ms Santiago’s commitment extends to the summer as well, spending time to improve The Ms. Santiago reflects:

All summer was STEM stuff. STEM curriculum writing. STEM PD.

writings… because… you feel like you should. Especially. when you're somebody now who's been developed so much through SABES…. You're like, 'I can do this, and if I don't do this, then… who else is? Do they have the same background? Do they have the same knowledge?' (Focus Group, September 28, 2016)

Congruent with DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist, and Edin’s [ 8 ] concept of an identity project, Ms. Santiago adopted the focus of SABES whole cloth. SABES’s approach to elementary STEM education is now a part of her core identity as an educator. She so powerfully identifies with SABES community of practice [ 2 , 5 , 19 , 37 ] to the point of expressing a strong sense of ownership and stewardship over the work and a strong desire to improve and give back to a program that fundamentally shaped her personal and professional identity. This sense of ownership and stewardship over SABES is indicative of Lave and Wenger's [ 19 ] situated learning theory, as the novice has become the expert.

In addition to developing her students’ interest in STEM, Ms. Santiago hopes that teaching SABES’s STEM curriculum will make her students more engaged, confident, and willing to take risks. Furthermore, congruent with bell hooks’ [ 16 ] engaged teaching, Ms. Santiago wants her students to have a more “‘inquisitive’ nature instead of 'the teacher is just going to give me all the answers’” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016) . Her reflections indicate a significant pedagogical shift from the teacher as a “giver” of information to individual, student-driven learning. This shift coincides with a similar shift from a general education teacher to a STEM facilitator, “'I’m here to watch to make sure nobody hurts themselves…. And you notice, the more you let the kids do that, the more amazing the results are” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). Some of the students that Ms. Santiago had during her second year participating in SABES “ended up naming themselves the Flint Hill School Risk Takers” because “taking risks is just something they do now” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016).

The spillover effect of SABES on other content areas, like reading and writing, is echoed by Ms. Santiago's students. She says that her students are applying the steps of the Engineering Design Process (EDP) “without even knowing they are, like asking those questions, trying to figure out what the problem is in other subjects” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). In addition to applying the EDP outside of STEM class, her students are engaged with reading and writing, saying they “want to write because they’re excited. When they’re reading about STEM, they're reading something that they are interested in” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016).

Ms. Santiago was amazed by the objects that her students have created in her engineering classes, “We’re doing, for example, aerospace vehicles right now. I’m like, ‘You guys need to become engineers and create those things…. Nobody’s working on that. That can be your work’” (Focus Group, September 28, 2016). Her students’ passion for STEM and a strong desire to be on the engineering track all show how much Ms. Santiago and her students have been transformed by their participation with SABES.

6 Mr. Jelenik—taken under SABES wing

Like Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik has also been influenced by his participation in SABES. Mr. Jelenik has been teaching much longer than Ms. Santiago, recently completing his eighteenth year at Flint Hill Elementary School. Despite being a more veteran teacher, Mr. Jelinek has embraced SABES similarly to Mrs. Santiago, serving as an identity project.

Sixteen years ago, when Mr. Jelenik was still an undergraduate student, he knew that working in a Baltimore City elementary school was essential to him. As an undergraduate student in Baltimore, he participated in a program called “Teach the City of the Study,” an earlier initiative the university implemented that attempted to close the summer learning gap. In his second year with the program, he was placed at Flint Hill School, where he volunteered with the students on Mondays and Wednesdays. The school offered him a job the following year. Mr. Jelenik was passionate about supporting the learning of Baltimore City’s youth even before his first official year as a teacher.

Mr. Jelenik’s interest in STEM was present, although underdeveloped, early in his career. Although he both “liked science” and “liked the idea of finding stuff out,” though he “wouldn’t really say that starting off, [he] had any passions or anything like that in science” (Interview, November 15, 2016). When he first started teaching, he taught all subjects. However, the focus was on reading and math. They “mandated a lot of how much you have to teach reading in a day, two and a half hours, and then an hour and a half of math” and that “there wouldn’t be any time for science or social studies”' (Interview, November 15, 2016). This statement supports the National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education [ 3 ] finding about the significant reduction in minutes per day allocated for science instruction compared to reading and math. It is a sentiment shared by both Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik, reflecting the historical de-emphasis on science in the District’s elementary schools. However, counter to the District’s message, Mr. Jelenik “always thought to [himself], ‘That’s unfair for the kids not to have [science]’” (Interview, November 15, 2016).

Mr. Jelenik is thankful that SABES mentored him. In an interview three years after he became a part of the program, Mr. Jelenik felt:

super lucky that [he] happened to be here, and SABES picked [him] up and took [him] under its wing. I'm a way better teacher now than I would've been if SABES hadn't come along. I probably would still be in textbooks reading chapters and doing worksheets rather than having science come alive in the classroom (Interview, November 15, 2016).

Like Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik’s identity as an educator transformed via participation in SABES, aligned to Lave and Wenger’s [ 19 ] notion of participative identity constructed within SABES’s community of practice. When asked what made a difference in his STEM instruction, Mr. Jelenik mentioned the “different courses in the academies, the professional development, “as well as the logistical and materials help” (Interview, June 12, 2016).

Like Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik discussed the positive changes he saw in his students after he started participating in the SABES project. He said his students “don’t need a lot of encouragement [or] motivation" and "jump right into it,” especially for units like the rollercoaster and electricity units (Interview, November 15, 2016), two of his favorites. According to Mr. Jelenik, this curriculum teaches them other skills, like “how to get along well with each other” during collaborative small group work and to “solve a problem or be creative in how you are going to solve this problem” (Interview, November 15, 2016). His students also learn from each other. In small group work, “someone figured it out, and then the rest of the class feeds off of that.” (Interview, November 15, 2016). Mr. Jelenik described a classroom similarly described by Seiler and Gonsalves [ 35 ], a democratic, justice-oriented classroom built on cooperation, collaboration, and creative problem-solving.

Despite the benefits of participating in the SABES’ program, Mr. Jelenik said there had been some challenges. He reflected that he probably does “a better job of having a whole group discussion” than “having them talk in their little groups of four” (Interview, November 15, 2016). Mr. Jelenik highlighted his “vision of what STEM should be: doing things and then explaining those things” (Interview, November 15, 2016). This more teacher-oriented approach to instruction is also reflected below in the video recordings of Mr. Jelenik’s classroom instruction and the stark contrast of Ms. Santiago's more student-driven approach.

7 Instruction in Ms. Santiago’s and Mr. Jelenik’s classroom

To better understand how Ms. Santiago’s and Mr. Jelenik’s identities as elementary teachers were transformed by their participation in SABES and their implementation of the curriculum, 13 classroom instruction periods were observed over two years. Recordings include the engineering design challenge, which occurred over three days at the end of each unit. Although both teachers taught at the same school, have been participating in SABES since its inception, and participated in numerous PLC opportunities, it transformed the identities of both teachers in different ways, resulting in different degrees of instructional transformation.

8 Topics that were taught during the classroom observations

While Mr. Jelenik has taught 4th grade at Flint Hill for four years, Ms. Santiago only taught 4th grade for one year before becoming a 5th-grade teacher. She then transitioned to STEM lead of the middle school engineering program and, therefore, out of the direct scope of SABES. As a result of their minimal overlap, the “Seashell Unit,” which reflects Baltimore’s proximity to the Chesapeake Bay was the only common unit observed and recorded by the research team (see Table 1 below for a complete list of the units taught by both teachers). For this unit, 4th-grade students learned about different types of shells and how to identify them. Ms. Santiago adapted the unit to include fossils and “fossil imprints” of real-world items like keys and leaves localized to Baltimore City. Although there was some overlap in how both teachers taught the unit and approached the content, there was substantial evidence of divergence in their implementation, which is not uncommon in large-scale curriculum projects [ 30 ].

Informed by lens of a justice-oriented, student centered approach, five theoretical themes emerged from analyzing the videos of Mr. Jelenik’s and Ms. Santiago’s instruction. These five themes were identified because they aligned well with our theoretical construct of justice-oriented teaching and provide evidence for Mr. Jelenik’s and Ms. Santiago’s identity transformation, and their subsequent shift in instructional practices.

Enactment of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK): enacted localized science pedagogical content knowledge informed by their participation in SABES via their adherence to, modification of, and implementation of the curriculum.

Facilitation of STEM Learning: approached interactions with their students on a class, small group, or individual level as a facilitator rather than an instructor, reflective of justice-oriented pedagogy.

Enhancement of Student Voice: fostered student voice during instruction, promoting student engagement with the scientific material and transforming their identities as scientists, reflective of justice-oriented pedagogy and, in the case of Ms. Santiago, engaged teaching.

Fostering Student-to-Student Interactions: fostered prosocial student-to-student interactions during STEM instruction, reflective of justice-oriented pedagogy.

Use of Local Touchstones: incorporated elements of local knowledge and pop-cultural touchstones during their lesson instruction, reflective of justice-oriented curriculum.

We will describe each theme’s evidence in the next section, beginning with the science unit both teachers taught on seashells and then analyzing instruction from the non-overlapping units describing the relationship between participation in SABES, the identity transformation of Mr. Jelenik and Ms. Santiago, and the eventual influence of their instructional practices evidenced by the five theoretical themes identified in the videos of classroom instruction.

9 Pedagogical approaches and adherence to, modification of, and implementation of SABES’s curriculum

9.1 enactment of pck through facilitation: the sea shell units.

When we observed Ms. Santiago teaching the unit on seashells, she demonstrated localized PCK by emphasizing the description of the shell's characteristics while reinforcing student independence throughout the lesson. Ms. Santiago gave each group of students a bag of shells collected in and around the Chesapeake Bay and fossils to identify by examining their characteristics and then had one speaker from each group model how the students were supposed to present to the class, “I think this fossil is [X] because [Y]….” (Classroom Observation, January 27, 2014) Ms. Santiago ended the lesson by having each student create their fossil imprint by following the directions on a handout using cement and an object in a milk carton.

Throughout the lesson, Ms. Santiago reinforced student independence by responding to student questions that supported student autonomy such as “what does your handout say?” (Classroom Observation, January 27, 2014) rather than simply providing the students with the answer. This is an example of Ms. Santiago's transformation via SABES, as she wanted to develop independence within her students, embodying the facilitator's role that is integral to a justice-focused approach.

In contrast, Mr. Jelenik supported his students differently. Mr. Jelenik spent the first 15–20 min of the lesson with the whole class using teacher-centered instruction by reviewing a PowerPoint of seashell vocabulary. Following this instruction, the students then completed a hands-on shell identification task in small groups, reinforcing scientific vocabulary terms.

After observing that several groups of students struggled with the difference between bivalve and univalve shells, Mr. Jelenik led the class in a discussion.

Mr. Jelenik: Why would there have to be another piece to this shell? Student: To protect the mollusk Mr. Jelenik: Good. Do you think if this shell was just one piece, would the creature be protected? Student: No, because it needs the other piece so it can open and close. Mr. Jelenik: Exactly, so we’ve established that this is a bivalve. (Classroom Observation, January 24, 2014)

During this lesson, Mr. Jelenik walked each group through identifying the same shell, a bivalve with a straight hinge and grooves. He also modified the lesson by modeling how to present their findings to the class before having one person from each group present one of the shells they identified to the class.

9.2 Enactment of PCK through facilitation in non-overlapping units

Mr. Jelenik and Ms. Santiago adapted lesson plans by showing their students a prototype of what they would build. During the “Weather Watchers” unit, Ms. Santiago showed her students a prototype of the barometer they would make before dismantling it. Before the engineering design challenge for the “It’s Electric” unit, where students had to build and wire a cardboard house, Mr. Jelenik showed his students a prototype of the house that previous students had built. He emphasized the house's simplicity, as he did not want students to spend time creating a cardboard box mansion “with 15 rooms and a garage” when the challenge is to wire a house with two rooms. Unlike Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik kept the prototype on display while students planned and built their houses.

Congruent with engaged teaching, Ms. Santiago identifies her role as a facilitator for her students. At one point during a lesson in the “Weather Watchers” unit, Ms. Santiago asked her students.

Ms. Santiago: If you have any questions, what do you do? Class: Raise your hand Ms. Santiago: Am I going to give you the answers? Class: No Ms. Santiago: I am not going to give you any answers, but I will help you out (Classroom Observations, September 29, 2015)

Her role as a facilitator promotes student independence, confidence, self-reliance, and problem-solving skill development, reflective of a justice-oriented approach. The approach is also reflective of her transformation via her participation in SABES, an aspect she identified during her interviews. As evidence of co-developing the lesson plan with her students, Ms. Santiago told her class that it was “up to the students” if they wanted to make one barometer or two.

After discussing how students define what engineers do, Mr. Jelenik sees an opportunity to make a significant point. Most of the students mentioned either building or fixing electronic objects. However, one student mentioned that engineers design and build bookcases. Mr. Jelenik seized on this suggestion, which led to an unplanned but fruitful discussion about how bookcases and non-electronic objects are also designed and built by engineers (Classroom Observation, December 2, 2016).

During each unit's engineering design challenge portion, the curriculum supports the teacher’s role shifting from teacher-centered instruction to student-centered facilitation. When facilitating students should be allowed to work through problems and arrive at potential solutions relatively independently. Aligned with engaged teaching and the intent of SABES's curriculum, Ms. Santiago described her role during the engineering design challenges as “allowing the students to” “do what [they] gotta do.” (Teacher Focus Group, September 28, 2016).

Contrary to Ms. Santiago’s more student-centered approach, Mr. Jelenik’s role in instruction is more teacher-directed. In addition to setting more restrictive parameters, Mr. Jelenik spent 7 min discussing SABES's required supplies instead of letting the students figure things out for themselves (Classroom Observation, December 7, 2016). Additionally, Mr. Jelenik required each group to seek his approval of their plan for their model before they could start getting materials, limiting students' ability to modify their design, an essential component of the iterative engineering design process (Classroom Observation, December 7, 2016). As described earlier in the paper, these observations provide evidence of Mr. Jelenik’s internal struggle between his years spent teaching in a more teacher-centered classroom and his burgeoning teacher-as-a-facilitator identity.

9.3 Enhancement of student voice: the seashell unit

An integral part of SABES curriculum is emphasizing a justice-oriented student-centered instruction through student-centered pedagogy alongside student presentations, which supports student discourse and their ability to articulate their ideas about STEM. Ms. Santiago fosters student voices by asking students to describe their understanding of STEM using everyday language with some technical language. In one example, Ms. Santiago reinforces student usage of vocabulary terms when one student says, “I think… I predict that this is a seashell with a straight line.” to which Ms. Santiago replies, “So it has grooves? That is a characterization. So it has grooves, a straight hinge.” Notably, this student voiced academic vocabulary examples, such as “I think” and “I predict” in their answer. (Classroom Observation, January 27, 2014).

Ms. Santiago also lets her students respond to each other’s points and ideas without interrupting, thereby allowing them to build off each other’s ideas, creating a student-driven co-construction rather than one with the teacher as an intermediary. When she does speak after several students have had the opportunity to share, she says, “OK, so I think we can all agree that that is Minnie Mouse. I like that Student 1 gave us a few characteristics about why he thought it was Minnie Mouse, and like he said, not Mickey. I like that Student 2 added on the whiskers and Student 3 added on the ears” (Classroom Observation, January 27, 2014). Reflective of a student-centered, justice-oriented approach, Ms. Santiago simultaneously synthesized the three previous students' responses while giving positive feedback on their statements.

Like Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik also emphasized characterizations in his seashell lesson. However, Mr. Jelenik’s students rooted their descriptions in the more technical vocabulary terms from the lesson, reflecting the vocabulary review that Mr. Jelenik did to begin the lesson. In one example, students were asked to spot differences between two shells:

Student 1: One of the grooves for the left picture is taller, and the other one has little circles in it. Mr. Jelenik: OK, so one looks like lines, and the other is a little circular. Student 2: The one on the right has hinges. Mr. Jelenik: Nice, yes, it has hinges. What kind of hinge does it have? Class: Straight hinge (Classroom Observation, January 24, 2014)

Later in the class, Mr. Jelenik led his students to identify several different shells and had one student from each group present:

Student 1: The shell was a bivalve because it has a round hinge at the bottom and another part, so I’m going to say bivalve and go to number 2. Mr. Jelenik: I think what you’re saying is really smart. Does anybody agree or disagree? Student 2: I think it's a bivalve because it's going to have another piece to it at the bottom, is missing, the other shell that didn't have another piece they look rounded. I think it's going to be two shells, like [student 1] said. Mr. Jelenik: I thought it was a really smart thing that [student 2] said because he thought that there was a hinge, so that probably means there are two pieces. (Classroom Observation, January 24, 2014)

These opportunities to speak in front of the class and reinforce the science concepts the students are learning while allowing them to find their voice in the classroom and develop their public speaking skills.

9.4 Enhancement of student voice: non-overlapping units

The teacher’s ability to foster students’ autonomy and voice during classroom instruction occurs during several units. In one class, Ms. Santiago asked her class, “What is an adaptation?” One student responded, “an adaptation is a feature that all living things have that help them survive in their habitat.” Without missing a beat, another student said, “I agree with [the first student] because when we were getting our habitats, you told us that an adaptation was to help parts of animals to help them survive in their habitats.” Following this discussion, several other students gave specific examples of adaptations, such as a beaver’s teeth or stripes, a bear’s claws, or a Komodo dragon’s poison in its mouth. After several minutes, Ms. Santiago responded that she “appreciates… that [the students] did not just tell me the adaptation, but you told me how it helped the animal survive.” (Classroom Observation, October 5, 2015). She allowed multiple students time to answer the question in this example. She waited to respond until several students raised ideas, thereby maximizing student participation, student discourse, and the freedom to influence classroom discussion, an essential aspect of Ms. Santiago’s identity transformation and an example of her more engaged approach.

In contrast to Ms. Santiago’s more student-centered approach to classroom discussion and Q&A, Mr. Jelenik’s approach is more teacher-to-student. In discussing the types of forces that get a roller coaster to move through a track, Mr. Jelenik asked the class, “What force is responsible for the roller coaster leading up the hill?” One student responded with “the machine.” Mr. Jelenik said, “Right, the machine. And then what makes the roller coaster go down the hill? Gravity, right?” A minute or so later, one student points out that “the energy changes… from potential to kinetic and from kinetic to….” Without allowing the student to finish, Mr. Jelenik said, “To thermal, through friction. What kind of energy comes out of a roller coaster besides kinetic, thermal?” (Classroom Observation, April 22, 2015). In this example, Mr. Jelenik interrupted the discussion by filling in the answer he was looking for (gravity and thermal energy). While Ms. Santiago allows students to respond to each other and build on each other’s answers without interruption, Mr. Jelenik responds after every student, subtly and not-so-subtly shaping the discussion himself. Mr. Jelenik’s more teacher-centered approach is less reflective of justice-oriented pedagogy, reflecting only a partial transformation via his participation in SABES.

9.5 Fostering student-to-student interactions: the seashell unit

How Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik give their students feedback while working in small groups reflects their differences in adopting a justice-centered approach. When Ms. Santiago discovered a mistake one of her students made, she had the student walk her through their thought process and what they needed to do differently:

Ms. Santiago: [Student 1] how much [water] did you put in here? Student 1: One and a half [cups]. Ms. Santiago: How much does it tell you to add? Student 1: One and a half [cups]. Ms. Santiago: Read the directions again. Student 1: Oh! One half [cup]. (Classroom Observation, July 27, 2014)

In addition to this exchange representing an example of the cross-curricular nature of SABES material involving both reading and math, Ms. Santiago indirectly helped her student realize their own mistake instead of giving them the correct answer.

In contrast to Ms. Santiago’s feedback style, Mr. Jelenik directly points out his students’ mistakes and talks them through the correct approach. When tasked with using deductive reasoning to identify a shell correctly:

Mr. Jelenik: Is it a bivalve or univalve? Student 1: Univalve. Mr. Jelenik: It is not a univalve, it has to have another part covering it, so it’s a bivalve. Is the outer surface smooth or shiny? No, it’s rough with grooves, is it flat or a dome? Student 1: Flat. Mr. Jelenik: This is a dome, see? It’s a dome, so [this shell] is a kitten’s paw. So take a look at this [other shell] again because you mislabeled it. (Classroom Observation, July 27, 2014)

Although Mr. Jelenik led his students through the correct thought process to the right answer, he neither allowed his students to find the correct answer for themselves nor answered all of the questions. There are also points when Mr. Jelenik stops the student entirely before they even consider the process themselves, saying, “Wait, wait, wait. Stop, stop, stop. You need to look at this [the instruction sheet]. This will tell you what letter [each shell] is” (Classroom Observation, January 24, 2014). These are both examples of Mr. Jelenik’s struggle to reach their understanding instead of more teacher-controlled discourse, examples of a partial transformation via his participation in SABES.

9.6 Fostering student-to-student interactions: non-overlapping unit

The differences between how Ms. Santiago and Mr. Jelenik provided feedback to their students while facilitating are reflected in other units. During the “Amazing Adaptations” unit, Ms. Santiago gave positive feedback to her students and incorporated the teaching material into that feedback. During a task where students had to write letters to an animal, Ms. Santiago told one small group of students, “I’m very happy with your letters [to the polar bear]. You and your hairy feet that help it stay warm in your cold environment.” (Classroom Observation, October 5, 2015). Later that class, after students colored butterflies that had to camouflage with objects in the classroom, Ms. Santiago told the class, “I really liked [student’s] butterfly that is camouflaged with the slide [on the smart board]. That was creative, [because she] had to draw the letters onto it… and actually had to shade it beige” (Classroom Observation, October 5, 2015). Not only did Ms. Santiago provide positive feedback to her students, but she also identified specific aspects of the student's work that showed evidence of learning.

Unlike Ms. Santiago, Mr. Jelenik alternated between doing the entire exercise for the student and starting the task while letting them finish it. In one unit on electricity, students had to sequentially arrange paper strips of the engineering design process steps and glue them in order. Mr. Jelenik noticed one student did not have their steps in the correct order and told the student, “That’s ‘create,’ you want ‘ask.’ Wait a minute” before taking the strips and putting them all in the correct order. In another small group exercise, students had to wire a cardboard house. Mr. Jelenik walked over to one group and took the scissors and wire, saying, “all right, I'm going to cut this. So you want to connect this now to the bottom. And if I were you, I would use the glue stick” (Classroom Observation, October 2, 2015).

9.7 Teacher’s use of local knowledge and pop-cultural touchstones: the sea shell unit

Ms. Santiago modified the lesson plan to identify clay “fossil” imprints of keys, leaves, and two cultural touchstones: Mickey and Minnie Mouse. Throughout the shell and fossil identification lesson, Ms. Santiago had her students describe characteristics such as the holes and triangles in the key, the distinctive ears that Mickey and Minnie Mouse have, and Minnie Mouse’s bow (Classroom Observation, January 27, 2014). Ms. Santiago’s approach more student-centered, engaged approach contrasted with Mr. Jelenik’s emphasis on students reciting definitions.

9.8 Teacher’s use of local knowledge and pop-cultural touchstones: non-overlapping units