For Teachers

Career research projects for high school students, career research projects – essays and written products, career research projects – digital presentations, about the author, peter brown.

How to Write a Career Research Paper: Tips for Students & Teachers

- Trent Lorcher

- Categories : High school english lesson plans grades 9 12

- Tags : High school lesson plans & tips

The Need for Good Topics

After receiving the 27th research paper with a URL across the bottom of the page, I suspected plagiarism . I realized I had to make English research paper topics more agreeable, so I began teaching students how to write a career research paper. It worked.

Here’s a testimonial from a former student:

When I was in high school, I wanted to be a pipe maker. I followed your steps on how to write a career research paper. As I followed the process I realized that being a pipe maker could lead to compromising public photos, so I became an Olympic swimmer instead.

If the process of writing research papers can help Michael, it can help you. I now share with you my How to Write a Career Research Paper lesson plan, a lesson plan with a limitless number of English research paper topics.

The introduction of the research paper should include information about the writer and his or her interests. The body should examine the responsibilities, education requirements, potential salary, and employment outlook of a specific career. The conclusion should summarize what was learned.

A successful career paper should:

- discuss your career goals.

- describe your talents and interests.

- focus on one career.

- discuss career facts.

- cite sources correctly.

- look at the advantages and disadvantages of the possible career.

As with all essays, the process for writing a research paper begins with prewriting:

Brainstorm careers as a class:

Think of all the people you’ve talked to in the last 24 hours and jot down their career.

What careers appeal to you?

What careers do you think you’d be good at?

Skim the classified ads.

Look at Careerbuilder.com or Monster.com for career ideas.

Examine your goals . A career choice should take into account money, hours, advancement opportunities, and location. If your goals cannot be fulfilled in a particular career, it’s time to change careers or change goals.

Examine your skills and interests. Take note of what you are good at, and more importantly, what you would like to be good at.

Do some career research. Spend a day in the library and interview people doing a career that interests you. Document your sources as you search.

Pay special attention to the advantages and disadvantages of possible careers. I recommend making a chart.

Match the career with your goals, skills, and interests. That’s your topic.

Make an outline, cluster, or any of those other prewriting organizational techniques teachers always talk about.

Drafting and Revising

Include information about yourself–your goals, interests, talents– in the introduction . Be sure to end the introduction with a declarative sentence about the career you chose for the topic of your paper. In the body of your paper, present important information with commentary. Discuss the positives, negative, and skills you will need to improve to excel in this career. Be sure to discuss post secondary requirements, if any, and which schools offer the best programs.

When revising, use the following questions to make sure you covered what you need to cover:

- What are my career goals and how does the career I described reflect those goals?

- How does my chosen career suit my skills?

- What skills must I improve to succeed at my chosen career?

- Where can I go to learn the necessary skills?

- What do I need to improve personally to succeed at this career?

- Photo by Aringo (Flickr: Michael Phelps, Davis Tarwater) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0 )], via Wikimedia Commons

This post is part of the series: Different Types of Essays

Implement these strategies for different types of essays.

- Lesson Plan: How to Write a Reflective Essay

- Interpretive Essay Lesson Plan: How to Write a Literary Analysis

- Writing a Career Research Paper

- Lesson Plan: How to Write a Problem/Solution Essay

- American History Project Ideas: Capturing Oral History

Career Exploration Research Paper: Home

- Research Tools This link opens in a new window

Important Papers

- Career Rubric

Books from the Library

Click here to search for more books in the Library Catalog

From Noodle Tools Support

Step-by-step tutorials for Noodle Tools features

Creating your Noodle Tools account

Your Projects Tab

Your Sources Tab

Your Notecards Tab

Your Outline

- MLA Works Cited Checklist

- APA References Checklist

Create a Hanging Indent in Google Docs

Noodle Tools

Remember - a bibliography is not a list of URLs. Use Noodle Tools to properly format your citations.

With a Noodle Tools account, once you create bibliographies you can easily organize your research with note cards, outline your papers, and integrate with Google docs.

Users will log in via one of the following:

- Clicking the G Suite NoodleTools button (under the Google "waffle" menu)

- Entering their Google email on the login screen (under "Access via G Suite")

- New users can also go to: https://my. noodletools.com/logon/signin? domain=sau24.org

Need more information on citing sources?

Find more information on creating a Works Cited page, click on the Research Tools tab above. then click on the Cite Your Sources tab.

Assignment Details

Career Exploration Research Paper & Presentation

Career Exploration is an important part of your high school education because it gives you a focus for the future.There are many choices such as: the military, college, junior college, a trade school, a technical school, or right into a job.

Write a 2-3 page research paper on a career of interest. Collect research materials from the library and internet. You must include at least FOUR different sources. Your paper should be in MLA 8 format with a Works Cited page and IN-TEXT CITATIONS. You will also be presenting your career choice to your class . Use PowerPoint (or like format) to present the career using the same outline as your paper.

To help you focus your research follow the outline below:

Job Description/Duties – What does the job entail? What responsibilities would you have? Which responsibilities would you like or dislike?

Personal Characteristics and Skills Needed – What important personal characteristics do you think would be needed to be happy and successful in this occupation? Why does this career fit your personality? What personal values does this career provide that are important to you? (Examples: security, having fun, status, helping others, challenging…) What are some important skills your career requires?

Education Needed – What are the educational requirements of the job? What specific high school classes and activities would be most helpful in preparing for this career? What type of education or training would you need after high school? What schools offer this sort of training? How long is the course of study for this career? What is the potential total cost of training for this career?

Work Setting – How many hours would you generally work? What would your work environment be? Would you travel? Would your job be stressful? What would you like or dislike about the work setting?

Wages and Benefits – Entry wages: How much would a worker in this occupation generally start at? What is the range of wages that an experienced worker can earn? Will the worker receive insurance, sick leave, paid vacation? Will this occupation provide enough income for you to live as you plan? Does education make a difference in salary?

Employment Outlook - What is the occupational outlook for this career? Will I be able to pay back expenses for required education?

Personal Assessment - Explain why you think this occupation would be right for you. How does it fit your personality, interests, values, educational plans?

Citations - MLA 8 format, a MINIMUM of FOUR Sources, IN-TEXT citations and a WORKS CITED page are REQUIRED.

Suggested Resources:

An interview? Do you know someone who has this career?

Library Guide: https://jsrhs-sau24.libguides.com/career

Notes: 11/2/17 & 11/3/17

Rough Draft: 11/13/17

Final Draft: TBD

Presentation: TBD

Library Databases

EBSCO General research database which includes biography, primary sources, encyclopedia entries, magazine and newspapers.

Web Resources

25 Jobs you can get without a college degree

25 best paying jobs without a college degree

Career One Stop

Career Profiles

Targets and Competencies

WSP: Respect I can persevere to complete assignments that show original thinking, complete effort, and preparedness for learning. 1.2 I can produce clear and coherent writing following the writing process.

3.1 I can synthesize text evidence from multiple vetted sources and genres to support analysis.

3.2 I can integrate multiple valid sources of information presented in diverse formats and media.

4.3 I can present sophisticated information, findings, and supportive evidence in range of formal and informal tasks using style appropriate to purpose, audience. I can use various media to enhance my message.

Need More Help?

- Next: Research Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 10:38 AM

- URL: https://jsrhs-sau24.libguides.com/career

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, how do i write a research paper as a high school student.

I'm working on a research paper for a competition and it's my first time doing this. Any tips or resources on how to tackle a research paper at the high school level? Thanks!

First off, congratulations on taking the initiative to participate in a research paper competition! Writing a research paper can seem daunting, but breaking it down into steps will make the process more manageable. Here's a step-by-step guide on how to tackle a research paper at the high school level:

1. Choose a topic : Start by selecting a subject that interests you and fits the competition's guidelines. It's important to choose a focused topic rather than a too general or too narrow one.

2. Conduct preliminary research : Familiarize yourself with the topic by looking up related articles, books, and online resources. Note any significant themes, questions, or perspectives that stand out to you during this initial phase.

3. Develop a research question : Based on your early findings, develop a research question that guides your investigation. A strong research question should be clear, focused, and complex enough to require thoughtful analysis.

4. Gather detailed information : Use databases, journals, books, and other reliable sources to collect data related to your research question. Keep track of your sources for citation purposes.

5. Organize and evaluate : As you gather information, analyze the material and look for key points, patterns, and trends. Organize your findings in a logical manner (by theme, chronology, or viewpoint).

6. Develop a thesis : Your thesis statement should be a concise argument that answers your research question and captures the central idea of your paper. This will help guide your writing.

7. Create an outline : Establish a structure for your paper by outlining the introduction, body, and conclusion. This will help you organize your thoughts, create a logical progression of ideas, and keep your paper focused on the main points.

8. Write the paper : Begin by writing a draft of your paper following your outline. Start with the body paragraphs, covering the main points and evidence for each, and then move on to the introduction and conclusion.

9. Revise and edit : After completing your draft, review it for content, organization, grammar, and style. Solicit feedback from peers and teachers who can provide constructive criticism and help you improve the paper.

10. Cite your sources : Use the appropriate citation style (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.) to document your sources in-text and in a bibliography or works cited page at the end of your paper.

To learn more, read this blog post: https://blog.collegevine.com/how-to-write-research-paper-in-high-school/

Don't forget to carefully follow your competition's specific guidelines and submission criteria throughout the process. Good luck with your research paper!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to help high school students with career research.

High school students often tire of being asked, “What are your career plans?” Some students have no idea how to answer the question. Others may give a rote answer just to stop the questions. There are actually so many career choices available that high school students can pursue that they need direction in order to discover their own interests and skills. They may discover that opportunities are available they never even thought of before. Here are just a few suggestions that may help in career research for high school students.

Brainstorming

This may seem like a simple suggestion, but it is a good first step. Students should make a list of things they like and do not like to do and classes they like and do not like. For example, do they like history class but hate math class or vice versa? Do they like to work in groups or do they prefer to work alone? Do they like to work indoors or outdoors?

Assessment tests

There a variety of assessment tests that may be administered at high schools. If not, they can be found online. Some examples are:

- Myer-Briggs Test: This analyzes personality characteristics and how a person interacts with people or if they prefer not to interact with people at all.

- Strong Interest Inventory: This helps students who are having trouble identifying their interests and helps focus on what a student truly enjoys doing.

- Self-Directed Search: This test focuses on identifying skills and interests.

- Skill Scan Test: This focuses on seven specific skills and assists a student in determining which skills they have or want to develop.

Assessment tests are just stepping stones to identifying potential careers. Results should not be used to direct a person to or away from a specific career but should be used only as tools to help identify career choices.

Research potential careers

A few specific careers can be identified in order to pursue career research for high school students. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes an Occupational Outlook Handbook which provides detailed information for every possible job including:

- Job description

- Specific employers or types of employers

- Salary ranges

- Expected job growth over the next few years

- Educational requirements

- Where the jobs are located

Informational interviews

Students may know or can be introduced to someone who works in a job the student is interested in pursuing as a career. Guiding the student to develop interview questions of the professional person can be helpful. Students can get real answers to their career questions from people who actually work every day in the career of interest. Students can be guided to ask questions such as:

- How did the person train for the job?

- What does the person like best about the job?

- What does the person dislike about the job?

- What has the person learned that they wish they had known before pursuing the career?

- What advice does the professional have concerning what the student should and should not do in pursuit of the career?

Job shadowing

Some schools have job shadowing programs that give students the opportunity of actually working with a professional in the career of the student’s choice. The student arranges to spend several hours with the professional to “shadow” them and see exactly what they do on a daily basis.

If the school does not have a shadowing program established students can contact the local Chamber of Commerce for business directories and suggestions of professionals who may be contacted. Students can then set up individual job shadowing experiences.

You may also like to read

- How Teachers Can Help Prevent High School Dropouts

- Why Anxiety in Teens is So Prevalent and What Can Be Done

- Why Kids and Teens Need Diverse Books and Our Recommended Reads

- Websites that Help Students with High School Math

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Career and Technical Education , High School (Grades: 9-12)

- Teacher Toolkits and Curated Teaching Resourc...

- Online & Campus Master's in TESOL and ESL

- Online & Campus Master's in Higher Education ...

Perceived support and influences in adolescents’ career choices: a mixed-methods study

- Open access

- Published: 02 September 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jenny Marcionetti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7906-8785 1 &

- Andrea Zammitti 2

2493 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Support and influences on adolescents’ career choices come from a variety of sources. However, studies comparing the importance given to various sources of support are few, and none have analyzed differences in the support provided by mothers and fathers. This study aimed to examine quantitatively the importance given to support from various sources in a sample of 432 Swiss adolescents at two points in time in the period of choice and to explore qualitatively experiences related to support given/received by 10 mother–child dyads in the career choice process. The overall results endorse the mother as the main source of support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Associations between social support, career self-efficacy, and career indecision among youth

Reciprocal effects between parental support and career maturity in the developmental process of career maturity

Configuration of Parent-Reported and Adolescent-Perceived Career-Related Parenting Practice and Adolescents’ Career Development: A Person-Centered, Longitudinal Analysis of Chinese Parent–Adolescent Dyads

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the arrival of adolescence, career planning becomes very important (Gati & Saka, 2001 ). Among the main difficulties that adolescents have to overcome, there are school–professional choices (Lodi et al., 2008 ). In fact, around the age of 14–15 years, adolescents must make choices about their future and can live a condition of indecision and insecurity that is associated with difficulties in making decisions and with procrastination or avoidance of the choice task (Nota & Soresi, 2002 ). This process is certainly not facilitated by the 21st-century context, in which it is increasingly difficult to make predictions, ask for suggestions, or choose (Soresi & Nota, 2015 ).

It is widely recognized that parental support plays a fundamental role in career development of sons and daughters (Whiston & Keller, 2004 ), and in particular the support provided by mothers (Colarossi & Eccles, 2003 ; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992 ; Levitt et al., 1993 ). School actors, principally teachers, have also been found to be an important source of support for career choices (Wong et al., 2021 ). Although various studies agree on the importance of adolescents perceiving social support to deal with the career choice process (Whiston & Keller, 2004 ), still few have been interested in understanding what the most important sources of this support are (e.g. Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ; Gushue & Whitson, 2006 ), distinguishing not only between parents, school guidance counselors, and teachers but also between mothers and fathers, and also investigating whether the adolescent’s gender might influence this perception. In addition, few have studied adolescents’ perceptions of influences they have had and support received relating to the career choice and at the same time their parents’ perceptions of influence and support provided using a qualitative approach.

The present study thus had two main aims, each pursued with a specific approach. The first, using a quantitative approach, was to examine the importance of different sources of support in a sample of adolescents at two points in time in their last year of compulsory school. The second, with a qualitative approach, was to delve into the experience related to support given/received by 10 mother–child dyads in the career choice process.

Parental influences

Parents are a major source of interpersonal support and can influence their children’s self-efficacy and professional expectations, their interests, and career goals (Kenny & Medvide, 2013 ). It has been shown that adolescents consider it normal to be influenced by their parents in career choices and do not think that decisions will be made only by them (Bernardo, 2010 ). Indeed, the expectations of parents contribute to obtaining positive career outcomes (Fouad et al., 2008 ). However, this is valid only when the adolescent believes he can meet these expectations (Leung et al., 2011 ); when the adolescent does not feel up to meeting the expectations of parents, there is the risk of developing psychological distress (Wang & Heppner, 2002 ). Hence, parental support in this area can foster aspirations, exploration, and career planning (Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ; Ma & Yeh, 2010 ) but as long as it is actually perceived as support (Garcia et al., 2012 ).

Career concerns have to do with the stress of planning a future task (Cairo et al., 1996 ; Savickas et al., 1988 ). They represent anxiety about the fact that the individual is managing something important for their professional future (Code & Bernes, 2006 ). Students who find themselves making a choice must deal with this stress and manage the choice also based on the expectations of family, peers, and educational institutions (Creed et al., 2009 ). The career choice process, therefore, implicates emotions (Blustein et al., 1995 ) that involve both the adolescent and their parents. These emotions can stimulate action and make sense of the career development process within the family setting (Young et al., 1997 ). However, they can also be associated with prolonged indecision (Gati et al., 2011 ) and make mothers overly concerned, especially when adolescents hardly discuss their future plans (Kobak et al., 1994 ). Indeed, the behavior of parents concerning the choices of their children can be support, when they help them make choices by providing them with guidance, but also interference, when they excessively control the choices their children make, or lack of engagement, due to disinterest or other factors such as financial problems, overwork, or other (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ).

What has been expressed up to now indicates that parents can be a valid resource that provides instrumental and emotional support to the adolescent in transition increasing self-efficacy in career decision-making (Lent et al., 2003 ), professional and career adaptability (Kenny & Bledsoe, 2005 ; Parola & Marcionetti, 2021 ), career exploration (Kracke, 1997 ), and diminishing indecision about career choices (Guerra & Braungart-Rieker, 1999 ; Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016a ; Parola & Marcionetti, 2021 ). On the other hand, they can also constitute a risk factor in career choices when they interfere too much or lack engagement in this process (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ; Zhao et al., 2012 ).

Colarossi and Eccles ( 2003 ) conducted a study considering the perception of parental support on adolescents in the development of self-esteem or depression; the peculiarity of this study is that parental support was distinguished in support received from fathers and support received from mothers. Indeed, a limitation of research on parental support is that it is often considered as a single measure, without separating maternal and paternal support and considering the gender of the adolescent. The authors have shown, in fact, that the effects are different for male and female adolescents. In particular, male adolescents perceive greater support from fathers than females whereas it has been found that there are no significant differences concerning the perception of the support received from the mothers. Finally, fathers, compared to mothers, teachers and peers were perceived as providers of a smaller amount of support. This study is consistent with other research carried out in this area (Colarossi, 2001 ; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992 ; Levitt et al., 1993 ) and underlines the idea that it is important to differentiate maternal and paternal support. Indeed, according to Leaper et al. ( 1998 ), mothers show a tendency to use more supportive language than fathers and are more involved when it comes to the school and educational decisions of their children. According to this, Ginevra et al. ( 2015 ) and Porfeli et al. ( 2013 ) showed that mothers perceive themselves as more supportive than fathers in the career development of their children. Other authors also confirm these results, which underlines the greater role of mothers compared with fathers in their children’s career choices (e.g., McCabe & Barnett, 2000 ).

School influences

In middle schools, school counselors and career guidance specialists are often the main personnel responsible for monitoring and helping students in sustaining the career choice (Gysbers & Lapan, 2009 ; Multon, 2006 ). This is also the case in Southern Switzerland, where this study has been conducted. However, in studies made in other countries, it emerged that students do not always see their services as sufficient, or helpful (Mortimer et al., 2002 ). Hence, in many countries more responsibility has been given to teachers for supporting their students’ career development. On the one hand, teachers can give “general support” that can promote the development of different career and life competencies during their classes (Kivunja, 2014 ). In this sense, Lei et al. ( 2018 ) say that teachers provide general support in both giving social support, which involves emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal support, and promoting self-determination. Indeed, the teacher supports the development of autonomy, decision-making, and intrinsic motivation, which increase in adolescents the motivation to pursue life and career goals. On the other hand, teachers can give specific career-related support. For Wong et al. ( 2021 ) specific career-related support is “anything a teacher does that can facilitate the career planning of students” (Wong et al., 2021 , p. 132) such as inquiring about career paths, helping students identify their interests, giving information about jobs, and providing help in setting goals. Teacher support has been proven to have a significant impact on the development of students’ career aspirations, future orientation, career exploration, and planning (Alm et al., 2019 ; Hirschi et al., 2011 ; Rogers & Creed, 2011 ).

Studies that have compared the importance of various sources of support in the career decision-making process seem to point to teachers as the most important source of support (although the differences are never huge). These studies are few in number and have been conducted on quite diverse samples in terms of culture and age and considering different career-related outcomes. For example, Gushue and Whitson ( 2006 ) in the USA have shown that teachers support has more effect than parental support on the level of African American ninth-grade public high school students’ positive expectations about the career chosen. The study from Di Fabio and Kenny ( 2015 ) with Italian high school students suggests that teacher support contributes more than peer support in increasing resilience, perceived employability, and self-efficacy. Cheung and Arnold ( 2010 ) found that teacher support is more effective than parental and peers’ support in predicting career exploration in Hong Kong university students. Finally, Kenny and Bledsoe ( 2005 ) in a sample of US urban high school students showed that support from family, teachers, close friends, and peer beliefs about school all contributed significantly to the explanation of the four dimensions of career adaptability, school identification, perceptions of educational barriers, career outcome expectations, and career planning. Moreover, they analyzed the different contribution of each relational variable when controlling for the others, finding that family support contributed to explaining variance in perceived educational barriers and career expectations; teacher support contributed to explaining variance in school identification; and perceived peer beliefs contributed to explaining perceived educational barriers and school identification. The results thus seem to indicate that different actors may contribute differently to support the choice process. This suggests that all actors can play an important role in providing support. However, no study to our knowledge has captured adolescents’ perceptions with respect to which figure has been most supportive in this process. It is indeed important that not only does the support offered have a concrete effect on the choice process, but also that it is recognized, otherwise risking being interpreted as “lack of engagement,” and positively valued by the adolescent, otherwise risking being interpreted as “interference” (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ).

Methodologies to study career-related social support

Social support can be provided by close relatives such as parents and siblings and by other persons more or less trained to give it, such as career counselors and teachers. It can also be of different types; for instance, Cutrona and Russell ( 1990 ) and Cutrona ( 1996 ) distinguished between emotional support (the support given through love and empathy, concern, comfort, and security), social integration or network support (the support given by the feeling part of a group with people who hold similar interests and concerns), esteem support (the support that boosts others self-confidence through respect for others qualities, belief in another’s abilities, and validation of thoughts, feelings, or actions), information support (the factual input, advice, or guidance and appraisal of the situation), and tangible assistance (the support through instrumental assistance with tasks or resources). Moreover, the support received, and then perceived, can be influenced by one’s tendency and ability to ask for it (Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016b ). The same goes for the ability to give support and then to feel efficient in giving it. Finally, all these aspects can be influenced by cultural differences (Ishii et al., 2017 ).

Despite the complex nature of social support, there are few studies in which adolescents were asked who the most important people were in providing support in the process of school and career choice by directly asking them for their opinion on the matter. As mentioned earlier, we believe it is important that the support offered (by parents, school and career counselor, teacher, or peers) is also perceived and evaluated positively, lest it instead be deemed lacking in engagement or experienced as interference (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ). Moreover, the studies carried out to investigate the importance of different sources of career-related support for adolescents are mostly quantitative in nature, although there are some exceptions (e.g., Schultheiss et al., 2001 ; Young & Friesen, 1992 ). There is also a lack of studies investigating how parents–child relationships are influential in the career development process and the parents and children’s cross-perceptions of them and of the emotionality felt in them.

An interesting way to fill some of these research gaps is to use a mixed-methods research design. What is unique about these methods is that they allow both quantitative and qualitative approaches to be used in a single research study or set of related studies. To do this there are various ways that can make one or the other of these approaches precede the other and give different or equal importance to them (Creswell & Creswell, 2017 ; Stick & Lincoln, 2006 ). For example, in a first phase, quantitative data can be collected through the administration of a questionnaire. Then, the descriptive data provided in this phase of the study can be used to guide the subsequent qualitative data collection with face-to-face interviews. Thus, mixed method research utilizes a quantitative and qualitative approach to create a stronger research result than either method individually (Malina et al., 2011 ).

Quantitative data collected by sample-administered questionnaires and analyzed by the well-known statistical methods allow generalizability of collected data to the broader population (Creswell & Creswell, 2017 ). Instead, semi-structured interviews are a useful qualitative method to explore perceptions, experiences, and ideas on specific topics (Gill et al., 2008 ; Taylor, 2005 ; Wengraf, 2001 ). Semi-structured interviews have already been used for studies on career development support (e.g., Parola & Marcionetti, 2020 ; Schultheiss et al., 2001 ). To analyze information collected with semi-structured interviews, there are different methods. Content analysis allows making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context (Krippendorff, 1980 ; Mayring, 2000 ). The aim of this approach is to provide knowledge, new insights, and new representations of facts. It implies choosing some categories linked to the research question that are used to analyze a conversation or a text. This method has the advantage of permitting the identification of the main themes contained in a message and the way the message is expressed. However, it has the disadvantage of being quite sensitive to the researcher’s aims and corpus of data (Tomasetto & Selleri, 2004 ). Another useful method of analysis is thematic analysis that allows identifying, organizing, and explaining themes in a dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2012 ). It is simple to use, flexible, and allows anyone to easily read the results, enabling social and psychological interpretations of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ; Javadi & Zarea, 2016 ). For these reasons, thematic analysis is one of the most common methods of analysis in qualitative research (Guest et al., 2012 ). If mixed approaches (combining quantitative and qualitative approaches) for data collection are becoming more popular, few studies have so far combined content and textual analyses of interviews (e.g., Zambelli et al., 2020 ).

Aims of the study and methodological approach for data collection

Given that studies seem to indicate that (a) there is a differential perception of support providers between boys and girls, and (b) teachers are important support providers (Wong et al., 2021 ), in some cases even more effective than parents (e.g. Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ) and school guidance counselors (e.g. Gysbers & Lapan, 2009 ; Multon, 2006 ), the first aim of this study was to understand, from the point of view of adolescents, which are the main providers of support for career decision-making process at the end of compulsory school (at the beginning and at the end of the last year) and what are the eventual differences in perceptions between boys and girls. Few studies have considered the differences between mother and father, which is why they were given importance in this study. The specific research question guiding this part of the study was thus “which sources of support are most influential in career exploration and decision-making of adolescents?”. We felt it necessary that the answer to this question could be generalized to a large population of adolescents to be sure to focus the qualitative part of the study on the most important actors and content. Hence, this question was divided into sub-questions which then formed the questionnaire submitted to the adolescents. It was in fact considered important to explore: (a) whether the students had used the guidance service offered at school; (b) whether they had gone to the school and vocational guidance counsellor alone or accompanied (and by whom); (c) whether they were helped by someone in the choice process inside or outside school; (d) whether they felt they needed further help in choosing a school or a profession for the following year; and (e) who they considered to be the main source of support for this choice. The questionnaire was administered at two points in time, at the beginning and at the end of the last compulsory school year, to take into account and control for eventual variations in support perception at two important moments of the career choice process. In fact, for some teenagers, the summer period before the start of the school year is an opportunity to test some choices with company internships and meetings with potential employers. For others, the most important period is placed later in the school year, since the possibility of accessing some schools depends on academic success.

Based on the results that emerged in this first phase of the study, we considered that many studies have been published about the theme of the influence of parents on children, but that it is not always easy to trace the depth of a parent’s influence on a son or daughter’s career choices (Whiston & Keller, 2004 ). In fact, most of the previous studies have investigated the influences of parents on the career development of children in a quantitative way or have taken into consideration only the point of view of the children, mainly, or that of the parents. The second aim of this study was therefore to explore this aspect with a qualitative approach by involving 10 mother–child dyads to explore their possibly different points of view and emotionality. The choice to consider only mothers in this second qualitative part of the study was made bearing in mind the results obtained in the first quantitative part of the study. However, the goodness of this choice was also underpinned by the adolescents contacted for this second phase: when asked for a parental contact to discuss the topic of school and career choice, all spontaneously provided their mother’s. The two main specific research questions guiding this second part of the study were thus “what role do parents play in their child’s career decisions from the perspective of the mothers and of the children?” and “what sentiments emerge during the career decision-making process in mothers and children?”. Specific information about the participants involved in the two phases of the study, how they were involved, and the procedures for data collection and analysis will be laid out in the next section.

Participants

The study was conducted in southern Switzerland, in the Swiss Canton of Ticino, where the official language is Italian. In southern Switzerland, adolescents aged approximately 14 or 15 years, after middle school must choose between continuing a general education at a high school or starting an apprenticeship that usually involves spending three days at the company and two at a vocational school. Some full-time vocational schools also complete apprenticeship training. This choice can be difficult; indeed, access to high schools and some apprenticeships is limited to only those students with good academic achievement. Moreover, apprenticeships that provide part of the training with a company are accessible only to those adolescents who have found an employer. In this context, social support is crucial. A school guidance counselor is present in the middle school a few days a week and is available for one-on-one meetings with students; they may be accompanied by parents or family members if they wish. At the time of study, teachers have no institutionally defined role in supporting their students’ career choices. Only the class referent teacher, the penultimate and final year of middle school, is responsible for providing them, during class time, with information on the school and career guidance website ( www.orientamento.ch ) or first-hand information on available apprenticeship positions provided by the school guidance counselor.

Hence, students from 7 of 35 middle schools situated in various geographic locations (city, city’s periphery, and schools located in small villages in the valleys) were involved in the first part of the study. There were 432 participants at the two data collections (in October and May of the last year of compulsory school), 224 boys and 208 girls. During each questionnaire administration, the students received information about the aim of the study and were reassured about the confidentiality of their answers. The questionnaires were completed in an IT classroom during an ordinary lesson and under the supervision of the first author.

After the last data collection, 10 pairs of mothers and children for a total of 20 participants were selected to participate in the second part of the study. In the selection of the adolescents, taken from those who participated in the first part of the study and of whom we knew a range of information, some criteria were considered. First, adolescents were selected from two middle schools, a “urban” school and a “valley” school, and at the time of the last quantitative data collection, they provided a telephone number. Second, they had just finished compulsory school and were in the moment of transition between compulsory school and another type of education. Third, the type of education was considered: in the questionnaire, five adolescents said they would enroll in a general high school and five in vocational education and training (VET). Fourth, career decidedness was taken into account: in each school, two adolescents were sure of their educational choice, two had yet to confirm this choice, and one was not sure about it. Fifth, gender was considered: six were girls, and four were boys. Sixth, when reached on the phone, they gave their availability for an interview and provided a parent’s contact information. The parent was contacted and, after explaining the purpose of the study, gave his/her consent and that of their child to participate. We did not specifically ask which parent (mother or father) we wanted to conduct the interview with; however, all 10 adolescents provided the telephone number of the mother, who was also described as the parent principally supporting them in the educational choice and in the moment of transition.

In the questionnaires administrated at the beginning and at the end of the last compulsory school year, students were asked about their gender (masculine/feminine), the middle school in which they were enrolled (multiple choice question, with only one choice possible), about how many meetings with the school counselor they had (exact number requested) and with whom they meet them (multiple choice question, with more than one choice possible), who was helping or helped them make the career choice (multiple choice question, with more than one choice possible), and who helped them the most (multiple choice question, with only one choice possible). In the first questionnaire, students were also asked to indicate whether they felt they need more support (yes/no) and from whom (open question). In the second questionnaire, they were also asked about the type of future career education desired (high school/VET in full time school/VET with apprenticeship), their career decidedness (answer on a scale from 1 = not at all decided to 6 = completely decided), and, after having explained that the study also included interviews with a selection of them and their parents, if they agreed to give it, they provided a telephone number (open question).

Concerning the interviews, mothers and children were met separately at home or in a quiet place that they chose. Both were briefed on the objectives of the research and gave the informed consent to participate. All participants were informed that the data would be processed in aggregate form, without ever mentioning their names. Participants were asked for permission to record the interview. All participants agreed to register. The recording was transcribed and analyses were subsequently carried out. To investigate the areas of interest, semi-structured interviews were used, divided into the following parts: (1) an introduction referring to the description of themselves (or children) and their family, school progress, and relationships with peers, and (2) a section devoted to influences on choice. Semi-structured interviewing is a versatile and flexible data collection method, which can be modified according to the purpose of the research (Kelly, 2010 ). One of the main advantages is that this type of interview allows the interviewer to improvise questions, based on the responses of the participants (Hardon et al., 2004 ; Polit & Beck, 2010 ; Rubin & Rubin, 2005 ). Questions are determined before meeting the interviewee (Rubin & Rubin, 2005 ), to cover the main research topics (Taylor, 2005 ). However, the interview is not followed rigidly and rigorously; the basic idea is to explore the area of interest by providing participants with indications on what to talk about (Gill et al., 2008 ). This makes the semi-structured interview a simple method of data collection (Wengraf, 2001 ). In the present study, the interviews were conducted by the first author, adequately trained to conduct semi-structured interviews, as indicated by the literature (Kelly, 2010 ; Wengraf, 2001 ).

Data analysis

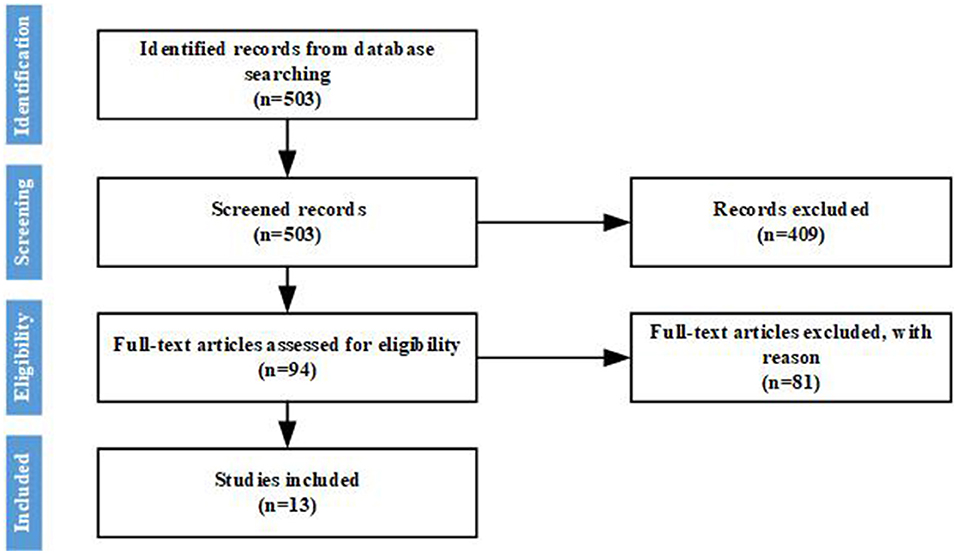

Descriptive analysis of data collected with questionnaires were performed with SPSS. This involved conducting frequency analysis of responses. Since some response categories had low n , especially after dividing them by gender, it was not considered appropriate to carry out more in-depth analyses to see if the differences in response between the first and second data collection were significant, which, moreover, was not an aim of the study.

To analyze the transcriptions of interviews, we used thematic analysis, accompanying this analysis with the use of a software for qualitative analysis (Nvivo 12). This allowed us not only to identify nodes and themes that we considered most relevant but also to show some relationships between them. Thematic analysis is a qualitative analytic method, useful and flexible for psychology research (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ). This method allows the identifying, organizing, and explaining of themes in a dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2012 ). Braun and Clarke ( 2006 ) developed a thematic analysis model divided into six phases: Phase 1: Familiarizing Yourself with the Data. This phase requires that the researcher reads and rereads textual data to highlight items potentially of interest. This phase involves an active reading of the qualitative content, starting to think about the meaning of the data. Phase 2: Generating Initial Codes. Codes represent labels for a data feature, a summary to describe its content, a shortcut that allows the researcher to quickly identify a topic. Phase 3: Searching for Themes. This phase requires the researcher to move from codes to themes. A theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” (Braun & Clarke, 2006 , p. 82). Phase 4: Reviewing Potential Themes. This phase requires the researcher to review the encoded data and perform a check on the quality of the encodings. Phase 5: Defining and Naming Themes. In a good thematic analysis, the themes should have a clear focus and purpose and be related but not overlapping. Together, the themes provide an overall history of the data. It is possible to have sub-themes within a theme. Phase 6: Producing the Report.

All the interviews were transcribed and then analyzed with the help of the NVivo 12 software. Where necessary, the software made it possible to identify the words most used in the answers, analyze the sentiments with respect to the proposed themes, and identify the differences in the nodes and sentiments between mothers and children. Sentiments are particular nodes divided into positive and negative. Each of these two nodes has two child nodes: a lot and moderately. We also used the NVivo software to highlight the themes we had identified from the thematic analysis. The software also allows you to indicate the attributes (in our case Mother-Son). The assignment of attributes makes it possible to distinguish information about the speaker (whether it is the mother or the child) and consequently to be able to explore the data with subsequent analyses. Specifically, thanks to the assignment of the Mother-Son attributes, we were able to use the matrix coding query that allows you to check how two elements relate to each other. Thanks to the fact that Influences within the Family, External Influences, and Sentiments were coded, we were able to verify how all these codes related to the mother or child attribute (QSR international, 2021 ).

Results from the questionnaires

At the beginning of the ninth grade, 14.4% of adolescents (13.4% of boys; 15.4% of girls) already had a meeting with the school guidance counselor. There were 62 students who had had a meeting; 43.5% of them met the counselor alone (27; 46.7% of boys; 40.6% of girls), and the others in the presence of the mother (32 out of 35 meetings; 50.0% of the meetings of boys, 53.1% of those of girls) and/or the father (7 out of 35 meetings; 10.0% of the meetings of boys, 12.5% of those of girls), or a brother or sister (4 out of 35 meetings; 3.3% of the meetings of boys, 9.3% of those of girls).

A total of 47.9% of the students (207; 47.3% of boys and 48.6% of girls) indicated that no one was helping them making a choice at this moment: 72.5% of them (150) said they did not need help; others (57: 19 boys and 38 girls) cited that, as a possible source of support, they might need their parents (28: 10 boys and 18 girls) and/or the school counselor (21: 8 boys and 13 girls); 13 (4 boys and 9 girls) did not know; and only 3 cited a teacher or “the school” (2 boys and 1 girls). Of the 52.1% of the students who received or were receiving support (225), 91.5% indicated the mother as a source of support (89.8% of the boys and 93.5% of the girls), 75.5% the father (80.5% of the boys and 70.1% of the girls), and 27.5% a brother or sister (28.8% of the boys and 26.2% of the girls). Other relatives or other people were cited by 16% of students, respectively. At the question “from whom, among those people, are you receiving the most important help?,” 64.0% indicated the mother (53.4% of boys and 75.7% of girls), 24.0% the father (34.7% of boys and 12.1% of girls), 6.2% a brother or sister (5.9% of boys and 6.5% of girls), 4.0% other persons (3.4% of boys and 4.7% of girls), 1.3% other relatives (1.7% of boys and 0.9% of girls), and 0.4% their stepmother or stepfather (0.8% of boys and 0.0% of girls).

At the second data collection, i.e., 1 month before the end of compulsory school, 46.8% of adolescents already had a meeting with the school guidance counselor. There were 202 students who had had a meeting; 42.6% met the counselor alone (86; 44.2% boys; 41.1% girls), and the others in the presence of the mother (103 out of 116 meetings; 47.4% of the meetings of boys; 54.2% of those of girls) and/or the father (32 out of 116 meetings; 18.9% of the meetings of boys; 13.1% of those of girls), or a brother or sister (2 out of 116 meetings; 0.01% of the meetings of boys; 0.01% of those of girls).

At this time, 39.1% of the students indicated that no one was helping them make a choice (169; 42.0% of boys and 36.1% of girls). Of the 60.9% of the students stating that someone was helping them (263), 86.6% indicated the mother as a source of support (82.3% among boys and 91.0% among girls), 60.5% the father (68.5% of the boys and 52.6% of the girls), and 20.9% a brother or sister (24.6% of the boys and 17.3% of the girls). Other relatives were cited by 12.9% and other people by 23.2% of students, respectively.

At the question “from whom, among those people, are you receiving the most important help?,” in line with result obtained in the previous data collection, 63.1% indicated the mother (56.2% among boys and 69.9% among girls), 20.5% the father (26.9% among boys and 14.3% among girls), 4.6% a brother or sister (4.6% among boys and 4.5% among girls), 1.2% a stepfather or stepmother (1.6% among boys and 0.8% among girls), 7.6% other persons (7.7% among boys and 7.5% among girls), and 3% other relatives (3.1% among boys and 3.0% among girls).

Results from the interviews

As indicated by Braun and Clarke’s ( 2006 ), we first familiarized ourselves with the data and generated preliminary codes. After, we generated the possible themes and subthemes that were examined and labeled. Finally, we produced the final report. Table 1 shows the established themes and subthemes. We have enriched the table by also indicating the number of times each theme or subtheme appears and how many persons cited it. Two themes emerged and are presented in the following paragraphs. Indeed, the sources of influence on choices were divided into two alternatives: influences and support that come from members of the family (Theme 1) and influences and support that come from outside (Theme 2). For each alternative, a parent-node and some child-nodes were formed and presented.

Theme 1: Influences within the family

Influences within the family were coded as follows: (1) influences from the mother (for example, Claudia, who said, “[my mother] did not oblige me but helped me... according to her I went more that way and she was right ” ), (2) influences from the father’s side (for example, Valeria, who, in response to “who helped you?,” said “Mom and dad”), (3) influences from brothers or sisters (for example, Davide, who said, “I was lucky because I have two older brothers and they also went to high school. So, I see the way more open”) and, finally, (4) no influence attributable to family members (for example, Fabrizio, who said, “I chose alone,” or the mother of Claudia, who said “on the choice we have not influenced any of our daughters”). The references of this coding have been presented in Table 2 .

To further understand the differences in the answers within the mother–child couple, we conducted a matrix coding query using Nvivo 12. It is a query that allows you to encode two elements (QSR international, 2021 ). The results of this query are summarized in Table 2 . The mothers involved in the study seemed to agree that no family member had any influence on the choice. In fact, all the encodings concerning the “Influences within the family” node are relative to the “None” child-node.

Livia’s mother: [My husband and I] have never said “our daughter must necessarily become a doctor or a lawyer”; the most important thing is that the profession must like her. Whatever she chooses, we do support her [...]. Anything she wants to do will be fine, the important thing is that she does it with her head, thinking well. Fabrizio’s mother: He [my son] went alone to do the career guidance interview, without telling me anything. He was curious to know what the path to being an engineer is and he inquired. I have not influenced him in this. I asked him if he wanted to be accompanied, but he preferred not to and did it all by himself. That was fine for me.

The answers given by the students are more diverse. They perpetuate the influence on the part of the mother on their choice and secondarily on the part of the father or brothers/sisters. All these influences are described as supportive, and it is interesting to note that the “father” node never appears alone but is generally associated with the “mother” node. Only four adolescents declared that they have not perceived particular influences from the family.

Davide: We talked about it as a family, with mum and dad. Interviewer: And in all this, you have managed yourself? Carlo: My mother, she was the one who looked for alternatives to the computer, also did things right on the curriculum vitae. She helped me, yes. Interviewer: And was it you pushing or were you both together? Carlo: A little bit of both. But she said to me “come on, why don’t you want to go and do this internship or see this thing?”. After I said yes, however, it was she who found the places, it was she who... yes, she helped me a lot. Interviewer: Who was helping you? Valeria: Mom and dad.

Theme 2: External influences

As regards the second alternative relating to influences, we have coded the parent-node as “external influences,” dividing it into the following child-nodes: (1) school guidance counselor, who collects the responses of the participants who referred to it at the time of the choice (for example, Fabrizio, who said, “I went to the Counselour, he gave me some help”), (2) classmates, when the influences came from classmates (for example, Davide, who said, “I saw that other classmates also chose the same thing and I felt more convinced”), (3) espoprofessioni (expoprofessions), or those who during the choice consulted the event dedicated to the professions (for example, Carlo’s mother, who said, “In September there was the event Espoprofessioni and we went”) and (4) word of mouth, when the adolescent received support from family acquaintances and friends (for example, Claudia’s mother, who said, “We had the advantage of personally meeting a doctor and we asked him for a hand”). The number of references is summarized in Table 1 . Also in this case, through the NVivo 12 software, we used a matrix coding query to further understand the differences between mothers and children in the perception of support coming from the outside. The results are shown in Table 2 . In the case of both the mothers and the students interviewed, we found that many times, during the interview, reference was made to the figure of the school guidance counselor. However, the support received was not always rated as satisfactory, in particular by three mothers and two children. Here are two examples:

Interviewer: [...] do you think the school or school guidance counselor should do something more? Livia’s mother: Yes, the counselor is not good. I must be honest. We went to the guidance office, but they put in front of the options “this, this and this” and that’s it. But even the counselor is not that he said much. He didn’t give much help. Instead, he should have asked my son what interests him, but he didn’t, for example. Interviewer: Have you seen the counselors? Claudia: I saw him, but I must say that he didn’t give me much help. My mother came once too but he didn’t help us at all.

Although to a lesser extent, some external influences come from classmates, word of mouth, or from having participated in the Espoprofessioni event, as emerged with these interviewees:

Livia’s mother: [...] We went [to the Espoprofessioni] by chance and stopped to talk to those in the health sector, medical help; there were the various schools, which illustrate their particularities. Carlo: When there were the Espoprofessioni, in that shed, we went to see and we started to decide a bit.

A final analysis we conducted was that relating to sentiment, which is used to evaluate feelings with respect to a theme. Sentiment nodes behave differently than other nodes. NVivo 12 allows you to code two parent sentiment nodes: positive and negative. Each of them has two child nodes: very and moderately. Automatic software setup aggregates child nodes to parent nodes (QSR international, 2021 ). Based on our analyses, we identified 11 positive sentiment nodes (of which 7 were positive, 2 very positive, and 2 moderately positive) and 40 negative (of which 21 were negative and 19 moderately negative). By way of example, we report some quotations of positive and negative sentiment. Parts of speech have been classified as positive sentiment:

Interviewer: [...] Are you afraid of the first day of school? Davide: No, no, in fact I can’t wait to start because I know it’s a new school. Interviewer: Are you worried about your son’s future? Fabrizio’s mother: No. Not for him. Because he finds a job for the profession he chooses anyway.

Parts of speech have been classified as negative sentiment:

Interviewer: Do you have any fears for the next few years, or do you feel calm? Federico: I’m a little afraid of what it will be like, yes; how hard it will be, yes; I have a little bit of that because I arrive from middle school, I don’t really know what the school will be like there. Federico’s mother: The context is difficult. Because it is a situation that can evolve in different ways, it is not very easy. Or the situation changes because a change is needed otherwise it is very hard. There is a lot of competition. The loss of quality in work, this need to do everything immediately, everything quickly, everything in the short term, little planned. This kind of future worries me about my son.

We were interested in verifying how these sentiments were distributed in the attributes of mother and student. The results, obtained through a matrix coding, are summarized in Table 2 . Most of the sentiment encodings have been found in the mother attribute. In general, mothers have a greater number of negative sentiments, while children have approximately equal numbers of positive and negative sentiments. This indicates that, regarding the choices and the future of the students, the mothers seem to be more concerned, while the children are also enthusiastic and curious about the new opportunities.

Data collected from the first and second questionnaires endorse the mother as the main source of support, followed by the father and other family members. These results confirm those of other studies conducted differentiating mothers and fathers as providers of social support (Colarossi & Eccles, 2003 ; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992 ; Levitt et al., 1993 ) and career-related support (Ginevra et al., 2015 ; McCabe & Barnett, 2000 ; Porfeli et al., 2013 ). Indeed, in this study, the mother is the one who most frequently participates in meetings with the school guidance counselor, regardless of her child’s gender. The mother is usually mentioned as a source of support by 91.5% of adolescents at the beginning and by 86.6% of those at the end of the last school year, although fathers are also seen as such by a good portion of the children (by 75.5% of adolescents at the beginning and 60.5% of those at the end of the last school year). The mother, followed by the father, is declared as the most important source of support. However, in line with the study of Colarossi and Eccles ( 2003 ), the data also show that daughters are more likely to perceive their mothers as sources of support and sons more likely to perceive their fathers as such, although contrary to the finding of their study in this study fathers are perceived as the second source of support, before teachers and peers. The support that adolescents, regardless of their gender, perceive as most available and also as the most important therefore comes first and foremost from their family. Gender seems to slightly differentiate the perception of support, perhaps because gender differences related to cognitive and relational styles (Eagly et al., 2004 ) lead girls to feel closer to their mother and boys to their father. Another explanation might be that the different types of professions considered by girls and boys, still largely influenced by gender stereotypes and therefore perceived as more feminine or masculine, make it more spontaneous to ask the mother or father about them. Even today, a boy is more likely to consider becoming a bricklayer than a girl, and if so, he is more likely to ask his father rather than his mother for information.

In the first part of this study, adolescents who are still making a choice and say they need more help, after parents, most often cite the school guidance counselor, while teachers are only rarely mentioned as a possible source of support. This finding seems to differ from those of other studies that highlighted the importance of support given by teachers, more than that given by parents or peers, for example, in enhancing positive career expectations in adolescents (Gushue & Whitson, 2006 ), in giving information and fostering self-efficacy in career decision-making (Cheung & Arnold, 2010 ), in fostering school identification (Kenny & Bledsoe, 2005 ), and contributing to increasing resilience, perceived employability, and self-efficacy (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2015 ). The low importance given to teachers as a source of support in relation to career choices by adolescents in this study can be explained in several ways. First of all, the “general support” that can be given by teachers in daily classes for developing important competencies that also facilitate career choices (Kivunja, 2014 ) may not be perceived as directly supporting choices by adolescents. Second, because of the way career-related support is organized in middle school in Southern Switzerland at the time of study, specific support for career decision-making is not among teachers’ main tasks. Hence, not all teachers act to facilitate the career planning of students that involves inquiring about career paths, helping them identify their interests, giving information about jobs, and helping them in setting educational and career goals (Wong et al., 2021 ). Finally, for both adolescents and their parents, in Switzerland, it is important, yes, to make a first career choice, but it is also important that this choice be crowned by successful enrollment in a school or entering into an apprenticeship contract. Hence, the most important help to achieve this last step can most easily be given by parents, as it emerges also from interviews, and, eventually, by the school guidance counselors who help the adolescent searching for practical information and, for those enrolling in VET, for an employer. Teachers for this last step can do little, aside from passing information provided by the school guidance counselor. This is perhaps also because the school guidance counselors are perceived as more important than teachers in this study, differently from other previous studies (Gysbers & Lapan, 2009 ; Multon, 2006 ).

The school guidance counselor, although emerging as a relatively important figure, is seen individually by less than half of the students over the last two years of compulsory schooling, and more than a half of them are accompanied by the mother. Although school guidance counselors are thus perceived as a source of support by a proportion of adolescents, they are definitely not the first source nor the one perceived as most useful, as highlighted in other studies (Mortimer et al., 2002 ) and also suggested by the results of the interviews conducted with this study.

In fact, the 20 interviews conducted in the second part of this study, and in particular the 10 carried out with the adolescents, confirm the importance of the mother as the first source of influence on career-related choices for them. As observed in other studies (Bernardo, 2010 ), it seems that adolescents consider it normal to be influenced by their parents in career choices. Influence from the mother is always perceived as a positive one by the child interviewed. Moreover, it is interesting to highlight that all the mothers affirm not to try to influence their child’s choice. However, referring to the support categories defined by Cutrona and Russell ( 1990 ) and by Cutrona ( 1996 ), what emerges from the interviews is that, regardless of the child’s gender, mothers provide both tangible assistance and information support (see Carlo and Claudia’s quotations), esteem (see Fabrizio or Livia’s mother’s quotations), and emotional support (see Livia’s mother or Davide’s quotations). The fact that mothers qualify this support behavior as a “non influence” on their child’s choice is an important aspect since studies have shown that this type of support is associated with greater career exploration, whereas when parents try to influence their children’s choices (Interference behavior), children experience more difficulty in career choices (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009 ; Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016a , 2016b ). The father, among the influences perceived within the family, is at second place, followed by a sister or a brother. However, the father is always cited together with the mother, further highlighting the importance of the mother for the career decision-making process of their child. As for sisters and brothers, they are an influence on choice when they are older and have already made their choice. In this case, the brother or sister, by telling and showing their experience in their chosen education, can be a role model to follow (or not to follow).

Regarding external influences, among the most frequently cited is the school guidance counselor; however, this professional figure, as has already been found in other studies (Mortimer et al., 2002 ), is not always perceived as helpful. The kind of support provided described in the interviews (see Livia’s mother quotation) seems to be purely informative, and perhaps both mothers and children expected more than information that they could probably have found on their own. The 20 interviewees, however, referred to only two school guidance counselors, so it is not the case to draw conclusions about the support provided by this professional category from these interviews. It should also be mentioned that the guidance counselors in cooperation with the Division of Vocational Training of Southern Switzerland organize every 2 years the Espoprofessioni event ( https://www4.ti.ch/decs/dfp/espoprofessioni/home/ ), which is cited as a source of useful information by two mothers and two children. Two other sources of external influence were word of mouth, i.e., the influence of family acquaintances and friends, cited by two mothers and by their children, and the classmates, cited by two adolescents. If acquaintances and friends also permit the facilitation of the organization of internships and eventually of finding an employer (i.e., they provide tangible assistance), classmates making the same choice further convince the adolescent that he/she made a good choice. According to the categorization of Cutrona and Russell ( 1990 ) and Cutrona ( 1996 ), this last type of support, more indirect, might be seen as esteem support as well as social integration/network support.

Hence, although all these figures and sources of influence play a role in the adolescent career decision-making process, this role differs both in the phase at which they intervene, in the type, and, we can assume, in its importance. In each case, mothers emerge as a kind of emotional safe haven from which children can explore themselves and professions. They encourage and accompany the child in this exploration, sometimes pointing out a possible course, which they nevertheless let the child choose whether to follow or not. At the time of the study’s conduction, other sources of support for career choice seem to be more marginal; they are tools from which to draw information or from which to get confirmation that the choice can be implemented. It is therefore not surprising that, regarding sentiments associated with the career choice, results show that though adolescents, feel both positive and negative emotions, mothers have a greater number of negative emotions. Mothers, personally involved in this important process, worry both about the choice their children have to make in the present and about their children’s future careers. Although this concern, much more typical in women/mothers than in men/fathers (e.g., Robichaud et al., 2003 ), may seem negative in some ways, it can nevertheless be the ignition engine for the career decision-making process of adolescents (Young et al., 1997 ), who are not always ready to initiate it spontaneously.

Limitations and future directions

This study allows more light to be shed on perceptions related to sources of support and influence in adolescents’ career choices, also taking into account both the gender of the adolescent and the distinction between mother and father. First, using a quantitative approach, it allowed them to be put in order of importance, and highlighting some differences in their perception related to the adolescent’s gender. Second, with a quali-quantitative analysis approach, it permitted the highlighting of the sources of influence and support in career choice perceived by 10 mother–child dyads and to highlight some differences in perception and emotionality between the two figures.

However, there are two limitations of this study to take into account. The first concerns the fact that, in the first part of the study, the adolescents’ perceived sources of support were taken into account, but without going into the type of support provided or the actual effectiveness of it. Also, the limited number of participants when divided into the various subgroups of males and females and those who saw the school guidance counselor did not allow for statistical tests to be conducted to assess reliably differences in perceptions between males and females. Moreover, only 10 mother–child dyads referring to two middle schools were interviewed. Extending the number of interviewees referring to a bigger number of middle schools, and thus, of school guidance counselors, might have permitted further investigation of the perceived effectiveness of this figure in supporting career choices. Moreover, a bigger number of interviews, also involving fathers (hence, also involving father–children dyads or father–mother–children triads), could have permitted a deeper investigation into the eventual differentiating discourses in relation to the influence and type of support provided by the mother and by the father. Finally, although the results are encouraging in indicating the presence of family support for career choice, it would be interesting to study the causes and effects of too invasive support (interference) or even of a lack of support (lack of engagement), considering the effect of gender, both of the adolescent who suffers it and of the parent who enacts it.

Knowing what the main sources of support for career choice perceived by adolescents are is important, and despite its limitations, this study permits the shedding of some more light on this subject. The fact that it is primarily the mother who supports her son or daughter indicates, for example, that specific interventions aimed at developing competencies for supporting choices in external sources of support should be directed primarily to this figure. The fact that daughters perceive (and expect?) even more support from their mothers than boys may also indicate that, where this support is lacking, they are even more likely to struggle than boys, who also more often consider fathers as a source of support. As already highlighted by other studies, it would be important to put more emphasis on the role of the guidance counselor, who, although perceived as a possible source of support, is still an underutilized figure and not always judged effective in providing help in the school setting. Unlike a guidance counselor who provides their services outside of school, this figure in school is limited in the time they have to follow up with students, and this may also affect the effectiveness of their intervention. An alternative could be to increase the amount of time this figure is in school or the type of support/intervention provided. Instead of face-to-face interviews, the literature seems to indicate that group interventions aimed at developing specific knowledge and competencies useful in career decision-making might be most effective in helping young people make choices and implement them (e.g., Mahat et al., 2022 ; Nota et al., 2016 ; Zammitti et al., 2020 ). Teachers might be involved, together with school guidance counselors, in providing these interventions. Indeed, as the figure who, after parents, spends the most time with adolescents and best knows each one of them, the teacher should be more involved in supporting students’ choices, especially given the positive outcomes of studies in which this figure is trained to make available this kind of support (e.g., Wong et al., 2021 ). Teacher support should be career-specific (Wong et al., 2021 ) but also, and perhaps mainly, a general informational, instrumental, and emotional support aiming at the development of competencies useful also for career decision-making process, such as self-exploration and awareness, decision-making competencies, relational competencies (for asking and providing support), autonomy, and self-determination (Kivunja, 2014 ; Lei et al., 2018 ).

Alm, S., Laftman, S. B., Sandahl, J., & Modin, B. (2019). School effectiveness and students’ future orientation: A multilevel analysis of upper secondary students in Stockholm Sweden. Journal of Adolescence, 70 , 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.11.007

Article Google Scholar

Bernardo, A. B. (2010). Exploring Filipino adolescents’ perceptions of the legitimacy of parental authority over academic behaviors. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31 (4), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.03.003

Blustein, D. L., Prezioso, M. A., & Schultheiss, D. P. (1995). Attachment theory and career development: Current status and future directions. Counseling Psychologist, 23 (3), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000095233002

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa