The University News

Why Three Day Weekends are Beneficial To Student’s Mental Health

Sophie Gloriod | November 18, 2021

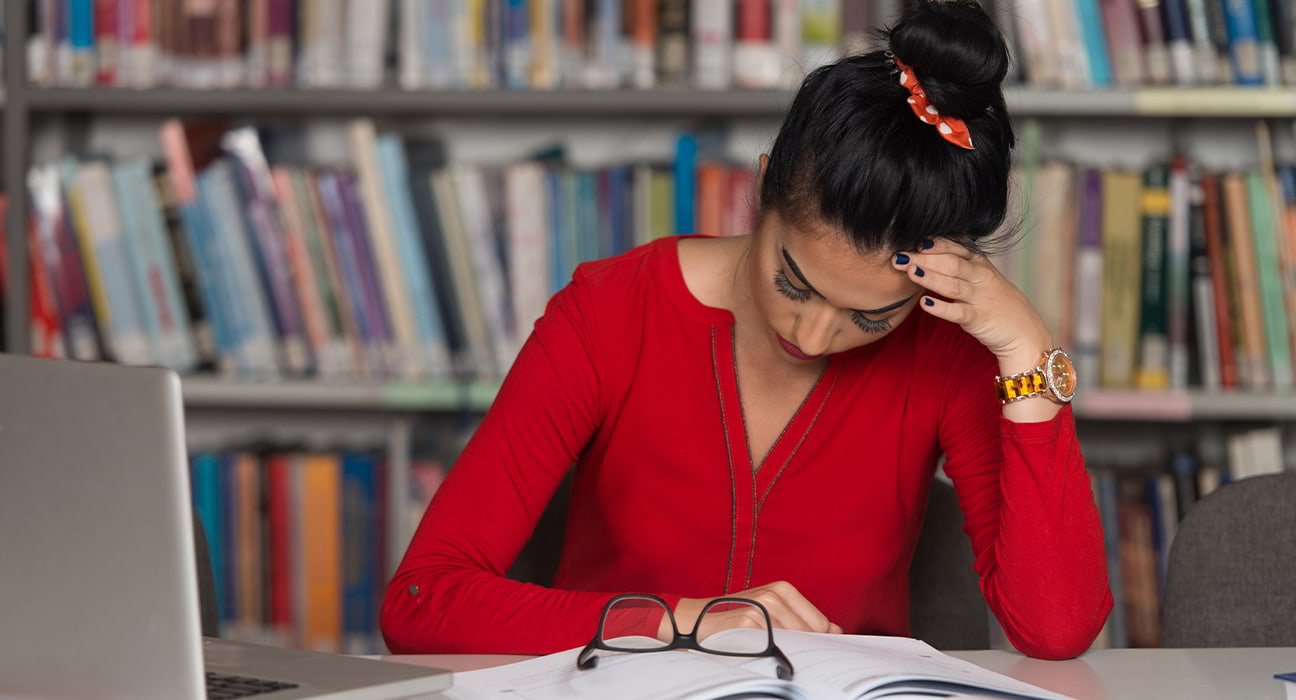

Everyone knows the stress that school brings. Whether you are currently a student, or graduated last year or 50 years ago, we all remember feeling overwhelmed and lost in piles upon piles of homework. More often than not, students feel that professors do not remember being a student and feeling these negative emotions. When students, especially younger students, find themselves feeling overwhelmed and lost academically, it can lead to them feeling those same emotions in other aspects of their life. This can negatively affect their mental health, causing them to feel even more stress.

College students are expected to juggle academics, navigating a new town, making new friends, living on their own for the first time and figuring out exactly who they want to be. On top of all of this, they usually have 15 hours of class time, not including the homework they must complete outside of class. The homework is usually much more complicated than the work done in class, and due to the large class sizes, professors are often not able to work closely with their students, leaving them feeling lost and alienated in the classroom.

All week, students look forward to the weekend as an escape from the busyness of the week. The weekend brings sleeping in and having free time to pursue activities they actually enjoy. However, more often than not, students spend most of the day Saturday and Sunday doing homework and chores. After sleeping in in an attempt to regain some of the lost sleep from the earlier week, students must focus on getting their homework, projects and exam prep completed. Not only are these days taken up from catching up from the previous week’s homework, but also attempting to get ahead for the upcoming week to prevent them from becoming overwhelmed. However, doing this takes up most of the weekend, leaving no time to relax and socialize with friends.

Back in September, SLU decided to cancel classes on a Friday, giving students a long weekend to try and help them improve their mental health. The administration had the right idea; giving students more time off does give them more time to complete their work and have time to themselves. However, one three-day weekend every month or so does not do much for their overall mental health. While every Friday does not need to be a day off, cancelling Friday or Monday classes more frequently will help students improve their time management skills, as well as better their mental health.

Having a three-day weekend lets students break up their work over three days instead of two. Hypothetically, if students use Friday to socialize and take some time to themselves, they can use Saturday to run errands and clean their living spaces, leaving Sunday to do homework and prep for the upcoming week. It also allows students to be able to sleep in on three days instead of just two. It is a proven fact that more sleep increases focus and overall health. Feeling well-rested also helps students stay motivated and helps them actually comprehend and understand what they are learning, instead of just memorizing for the exam.

Giving students a three-day weekend more often encourages them to prioritize their mental health. Especially nowadays, students feel that they are only worth love and respect if they excel in all of their classes. They do not feel encouraged to live in the moment and enjoy such an influential period of their life: college. Students are worth more than their grades; they are not at university to work themselves to death. They should feel encouraged to do their best and work hard, but not feel that they must sacrifice everything in order to succeed or earn an A in a class.

In the end, grades will change and in five years, no one is going to care if you aced or failed one paper. The health of students should be prioritized, mental health. If universities like SLU feel their students’ mental health is declining, they should take action. SLU felt a three-day weekend would be beneficial to improving mental health. Therefore, three-day weekends should become normalized. They should not be seen as a “break,” nor should professors be allowed to assign work over these days off. Giving students a three-day weekend will increase their free time, allowing them to practice better time management skills and improve their mental health.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Saint Louis University. Your contribution will help us cover our annual website hosting costs.

Decoding the Pentagon’s ongoing audit deficiencies

A love letter to the Alamo Drafthouse

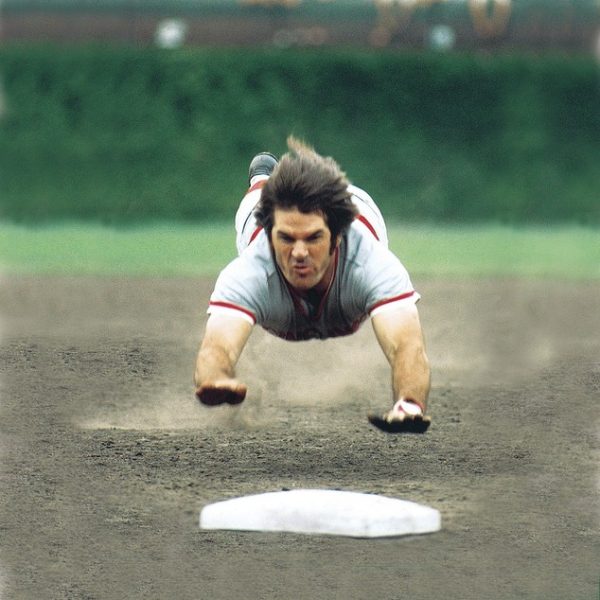

In defense of Pete Rose

Are you confident?

- Letters to the Editor

An open letter to SLU administration

How lonely are SLU students?

Arts & Life

Three romance books for oblivious boyfriends

Election 2024:

A rest-free April:

When, not if

The Student News Site of Saint Louis University

- Study Abroad

- Puzzle Solutions

- Advice Column

- Advertising

- Commenting Policy

- Rights and Permission

- Privacy Policy

- Saint Louis University: A Community In Mourning

- 2020 Election

- State of the University

- It’s Been a Year

Comments (13)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

BS • Mar 21, 2024 at 1:03 pm

Add more for younger students not JUST collage students.

brayan hernadez • Jan 26, 2024 at 11:09 am

CAN YOU ADD MORE THINGS THAT HELP STUDENTS

Lucy • Jun 7, 2023 at 7:25 pm

I found this helpful.

vito • May 10, 2023 at 2:21 pm

i love how they wrote this, this is so true

jonny • May 3, 2023 at 8:37 pm

hi this really help to inspire me

Catherine • Feb 19, 2023 at 7:13 pm

This was inspiring

LilyB • Jan 26, 2023 at 12:15 pm

this is great it should be sent to the board of education let us be off on Wednesday like a mid-week break

AndyA • Feb 19, 2023 at 1:34 pm

Totally agree with that.

EvieW • Mar 13, 2023 at 3:50 pm

I agree that this is great but then again the whole point of this argument is that it gives us a 3 day weekend. If it’s in the middle it’ll be hard to have to keep transitioning so quickly.

Derek Melvin • Sep 28, 2022 at 7:59 am

I think this is good because kids wont be glued to the comuters

Rayyan Hussain • Aug 27, 2022 at 6:21 pm

I think they should be 3 days of the weekends for students first of all it is very good for mental health for the students and not only for health also for religious reasons Muslims have a really special prayer on Fridays which they have to normally miss every Friday because of school so the Muslim students will be able to read the their important prayers on Friday which is very good so I think this is beneficial for students which it should be a thing.

Kittyluv2022 • Apr 21, 2022 at 10:00 pm

I love this article

MarioDaPimp♂️ • Mar 14, 2022 at 2:10 am

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

The Caravan

Students shouldn’t have homework on weekends.

Jonathan Kuptel '22 , Staff Writer | November 7, 2021

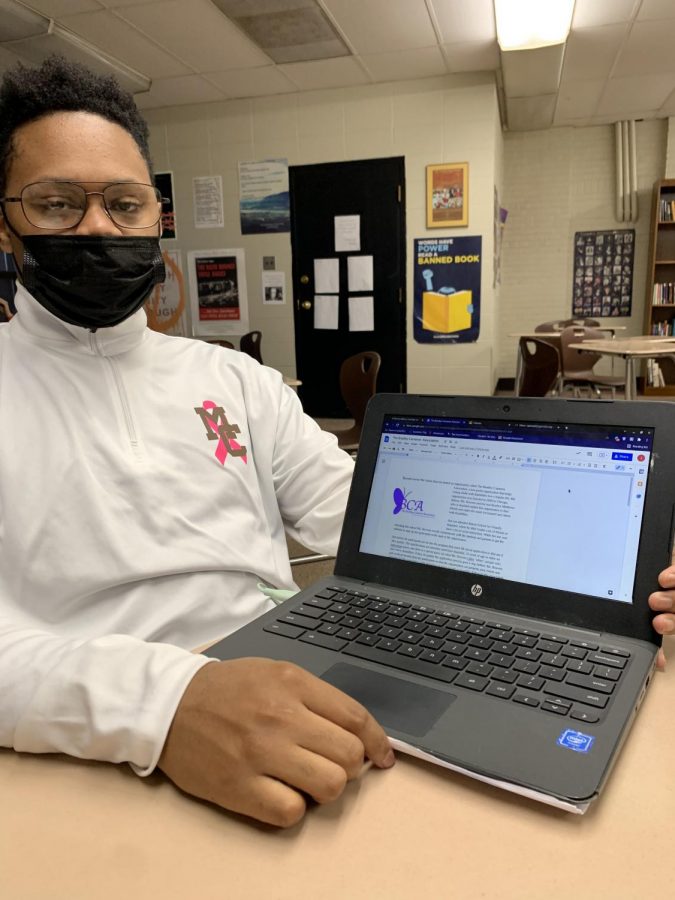

Jonathan Kuptel

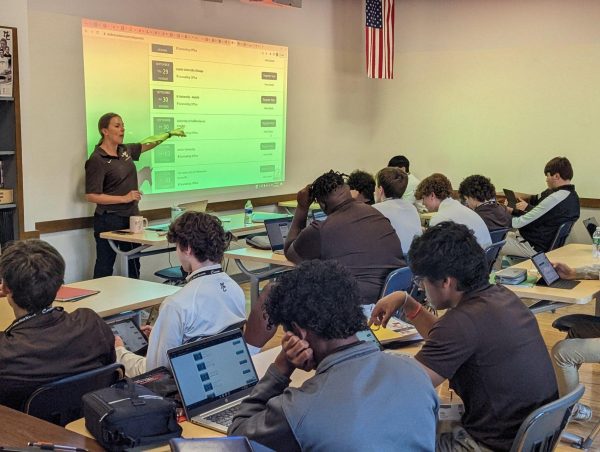

MC senior Imari Price works on a assignment for 21st-Century Media class.

Teachers and students have different opinions about homework. Saying it is not fair is the usual argument, but being fair is not the issue. It is about students being prepared. Daily homework assignments can be difficult, and weekends homework assignments are worse. Students operate best when they are well-rested and ready to go. A weekend with no homework would help them to be fresh and ready on Monday morning. Weekend assignments tend to be longer and more difficult.

The students have a difficult day with classes, practices, and going to school. By Friday, (test day) they are near exhaustion. Most tests are given on Fridays. Homework on Monday-Thursday is time-consuming. Some weekends will include assignments in more than 1 class. Those who go to Mount Carmel are near the end of their rope by 2:40 PM on Friday. I have had other discussions with the senior class and we all feel pretty tired at the end of the day at 2:40 PM. A free weekend helps to get prepared for the next grind to start. No homework weekends assures better sleep cycles and a body that has recovered and refreshed. Weekends include chores around the house and family commitments. This plus weekends assignments lead to a lack of sleep. This means Monday will have a positive attitude. No homework on weekends also means more family time. This is a bonus.

Alfie Kohn in his book The Homework Myth: Why Are Kids Get Too Much Of A Bad Thing says, “There is no evidence to demonstrate that homework benefits students.” The homework on weekends starts in elementary school and continues throughout high school.

Mr. Kohn states that homework on weekends starts in elementary school and continues throughout high school. This supports the argument that weekend homework starts in elementary school and now students at Mount Carmel High School have to deal with weekend assignments. The weekend assignments take too much time and are a waste of students’ time.

Nancy Kalish , author of The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children And What We Can Do About It, says “simply busy work” makes learning “a chore rather than a positive, constructive experience.”

Receiving weekend homework that is not discussed in class and counts only as “busy work” is counterproductive. Students finish the assignments because they are required to be done. When the homework is not reviewed on Monday, it leads to frustration. Busy homework that serves no purpose is never a good idea.

Gerald LeTender of Penn State’s Education Policy Studies Department points out the “shotgun approach to homework when students receive the same photocopied assignment which is then checked as complete rather than discussed is not very effective.” Some teachers discuss the homework assignments and that validates the assignment. Some teachers however just check homework assignments for completion. LeTender goes on to say, “If there’s no feedback and no monitoring, the homework is probably not effective.” Researchers from the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia had similar findings in their study “ When Is Homework Worth The Time?” Researchers reported no substantive difference in the grades of students who had homework completion. Adam Maltese, a researcher , noted , “Our results hint that maybe homework is not being used as well as it could be. Even one teacher who assigns busy shotgun homework is enough to be a bad idea.

Students come to know when homework is the “shotgun approach.” They find this kind of assignment dull. Students have no respect for assignments like this. Quality assignments are appreciated by students.

Etta Kralovec and John Buell in their book How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, And Limits Learning assert that homework contributes to a corporate style, competitive U.S. culture that overvalued work to the detriment of personal and familial well being. They go on to call for an end to homework, but to extend the school day.

Cooper, Robinson, and Patalc, in 2006 warned that homework could become counter productive. Homework is counterproductive when it is a (shotgun) assignment. To reiterate, not all homework is bad. Bad homework which is not reviewed in class just plain “busy work” is not positive and could be counterproductive.

Sara Croll, Literacy Coach and Author, believes too much homework causes stress for students. Diana Stelin, teacher, artist, and mother says, “I’m absolutely in favor of this ban. Homework is homework, it doesn’t matter what class it comes from. What it does is create negative associations in students of all ages, takes away their innate desire to learn, and makes the subject a dreaded chore.”

When students come to dread their homework, they do not do a great job on these assignments. Making students do a lot of homework isn’t beneficial because they get drowsy when they work at it for hours and hours at a time. It is hard for the brain to function properly when it is tired and boring.

Pat Wayman, Teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com says, “Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll.” “Their brains and their bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.”

No homework on weekends is not just a wish, but it is supported by all of these educators and authors. They all champion limiting homework are totally opposed to homework assignments. Educators and students agree that no homework on weekends is a good idea. Meaningful homework, a longer school day, and discussion of homework are what these educators and authors encourage.

My dreaded, but also rewarding, junior year

Appreciating some of MC’s most dedicated workers

Surrounded by my brothers: a senior reflection

Is it time to eliminate class rankings?

Running a 10k for the first time alongside my brothers

Straggling students need to step up for Walkathon fundraising

Mount Carmel benefits from trimesters

Students would benefit from financial planning, life skills

Nothing beats events in the Alumni Gym

MLK exemplified the values of Mt. Carmel

The student news site of Mount Carmel High School

- Journalism at Mount Carmel

- pollsarchive

- Sports Center

- Special Issues

- Conferences

- Turkish Journal of Analysis and Number Theory Home

- Current Issue

- Browse Articles

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting and Indexing

- Aims and Scope

- American Journal of Educational Research Home

- Social Science

- Medicine & Healthcare

- Earth & Environmental

- Agriculture & Food Sciences

- Business, Management & Economics

- Biomedical & Life Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Engineering & Technology

- Materials Science & Metallurgy

- Quick Submission

- Apply for Editorial Position

- Propose a special issue

- Launch a new journal

- Authors & Referees

- Advertisers

- Open Access

- Full-Text PDF

- Full-Text HTML

- Full-Text Epub

- Full-Text XML

- Panos Petratos, Daniel Herrera, Emre Soydemir. Academic Success and Weekend Study Time: Further Evidence from Public Elementary School Students. American Journal of Educational Research . Vol. 9, No. 2, 2021, pp 67-71. https://pubs.sciepub.com/education/9/2/2 ">Normal Style

- Petratos, Panos, Daniel Herrera, and Emre Soydemir. 'Academic Success and Weekend Study Time: Further Evidence from Public Elementary School Students.' American Journal of Educational Research 9.2 (2021): 67-71. ">MLA Style

- Petratos, P. , Herrera, D. , & Soydemir, E. (2021). Academic Success and Weekend Study Time: Further Evidence from Public Elementary School Students. American Journal of Educational Research , 9 (2), 67-71. ">APA Style

- Petratos, Panos, Daniel Herrera, and Emre Soydemir. 'Academic Success and Weekend Study Time: Further Evidence from Public Elementary School Students.' American Journal of Educational Research 9, no. 2 (2021): 67-71. ">Chicago Style

Academic Success and Weekend Study Time: Further Evidence from Public Elementary School Students

While there is general belief that students who study during weekends is more likely to succeed academically, empirical evidence on this postulation happens to be very limited in the extant literature. We provide evidence on this postulated association between academic success, and weekend study time by comparing responses from public elementary school students. A Survey is conducted for fifth and sixth grade students who are happen to be more mature relative to prior grade school students. The findings show that in general weekend study time is positively associated with greater academic success. We also examine the role of parental support and find that parental support leads to less weekend study time. The findings are consistent with the view that weekend study time results in greater academic success and parental support creates more free time for students during weekends.

1. Introduction

While there is general belief that students who study during weekends is more likely to succeed academically, empirical evidence on this postulation happens to be very limited in the extant literature. Particularly, there is not enough evidence on the amount of hours a student needs to study during weekends to reap the highest productivity. Weekend study time varies greatly among elementary school students. While there is some evidence on parental involvement, the association between academic success and weekend study time is less obvious. In this paper, we provide further evidence by investigating whether academic success is associated with weekend study time. In particular, a survey is conducted to examine the postulated association by comparing survey responses from fifth and sixth grade students.

There appears to be several distinct results that contribute to the existing literature. First, the findings show that greater academic success is associated with weekend study time. Greater academic success is reported for students who study more than one hour across the board in all subjects. Students tend to do better in mostly in ELA subject and least in science subject with weekend studying. Consequently sixth graders report studying more during weekends than 5 th graders. Studying less than one hour does not lead to any significant results between self-reported grade point average for all of the subjects. Lastly, parental involvement leads to less weekend study.

The findings are consistent with the view that academic success is associated with greater focus as depicted by the length of studying of at least more than one hour. Less weekend study time results from parental involvement. The findings are also consistent with the view that kids with parental involvement have more free time during weekends.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section two presents the literature review, section three describes data and methodology, section four reports findings and section six concludes.

2. Review of Literature

Erdogdu et al 1 examine factors associated with academic success. They find that access to internet, students’ possession of his/her own room in the house, parents’ education levels, students’ native language, school size and student per teacher ratio all have an effect on academic success.

Bahar et al 2 examine the impact of sociometric status and other correlates association with academic success. Bahar finds that gender, family, perceived social support from someone special to be meaningful predictors of academic success.

Calcagno et al 3 looks at institutional predictors of academic success. The study finds negative association with relatively large institutional size, proportion of part time faculty and minority students.

Erten and Burden 4 investigate to what extent do 6 th grade students attribute their performance in a school based achievement test. They find that ability attribution, interest attribution and teacher attribution to be the best predictors of test performance.

Pong 5 examines schools with greater concentrations of students who have single parent and stepfamilies. The study finds that schools that are predominated by students from single parent families and stepfamilies negatively affect their students’ achievement even after controlling for individual demographic characteristics and family background. This negative effect is attributed to low socioecomic status of single parent families and stepfamilies.

In this study we keep other factors constant and focus on the little examined association between weekend study time and academic success. The following hypotheses are tested in investigating the postulated association between parental involvement and weekend study time. First hypotheses conjectures that parental involvement for GATE students is associated with less weekend study time and greater academic achievement. Second hypothesis null statement is that Math, Science and ELA grades are higher with less weekend study time for NON-GATE students with parental support. Last hypothesis null statement is that the Math, Science and ELA grades are better for GATE students than non-GATE students both with parental support.

3. Data and Methodology

The survey was constructed using quantifiable questions. Thus, open ended questions were avoided. Surveys were administered anonymously. Surveys were printed and distributed by hand to fifth and sixth grade student population enrolled at Julien Elementary School. A Survey construction software 6 is used to enter survey data in digital format. Google spreadsheet was used to conduct statistical analysis to measure responses such as how self-reported student grades in Math, Science and ELA subjects are associated with parental involvement and without parental involvement in projects and homework. The dependent variables were, math grades, ELA grades and Science grades. Independent Variables were, weekend study time, parental involvement, gender, hours spent, GATE (gifted and talented education) and non-GATE distinction. Weekend study time was asked in categories that show hourly intervals from zero to five hours and more. Among 277 surveys that are printed, 238 surveys are collected and entered on the spreadsheet

4. Empirical Findings

GATE students who reported receiving parental involvement constituted 78 percent of the entire GATE student cohort. However, non-gate students who reported receiving parental involvement constituted 84 percent of the entire non-gate student cohort. Thus, a higher percentage of non-gate students reported receiving more parental involvement than gate students. This finding is consistent with the view that gate students perhaps need less parental involvement to achieve academic success than non-gate students.

Table 1 reports weekend study time and average self-reported grade point average for 5 th and 6 th grade math, science and ELA subjects. Non-GATE students who do not report studying during weekends appear to have a lower self-reported grade point average than those students who report studying during weekends. The picture is a bit more complex for GATE students. Interestingly, GATE students who report not studying during weekends appear to have a higher self-reported grade point average than those students who report studying during weekends. Perhaps the former cohort is subject to a different level of peer pressure or they spend more hours during studying during week days. Another explanation may be that these students have more parental support that removes the need to study during weekends.

Table 1. 5 th and 6 th Grade Weekend Study Time and Self-reported subject GPA

- Tables index View option Full Size Next Table

Table 2 reports average weekend study time for fifth and sixth grade non-GATE and GATE students. The responses reveal that non-GATE 5 th grade students spend on average 39 minutes studying during weekends. The study time is longer for 6th grade students who report studying on average 41 minutes. GATE students in 5 th grade report studying on average 53 minutes, longer that non-GATE 5 th grade students. Non-GATE 6 th grade students report studying on average 41 minutes. Thus they appear to study a bit longer than 5 th grade non-GATE students. GATE 6 th grade students report studying on average 1 hour and 8 minutes, longer than non-GATE students and 5 th grade GATE students. The findings are consistent with the view that 6 th grade requires more study weekend study time than 5 th grade in general. The findings are also consistent with the view that GATE students study longer during weekends than non-GATE students both in 5 th and 6 th grades

Table 2. Weekend Study Time

- Tables index View option Full Size Previous Table Next Table

Ordinary least squares estimations of the entire sample between weekend study time and self-reported grade point average for each of the three subject does not reveal any statistically significant results for any subjects. However, when we only count weekend study time reported more than 1 hour, the estimations reveal some meaningful results.

Table 3 reports the ordinary least squares regression results of the postulated association between weekend study time for more than 1 hour only self-reported grade point average of 5 th and 6 th grade students. The dependent variable self-reported math subject grade point average and the independent variable is weekend study time of more than one hour 3 . The weekend study time of more than one hour coefficient appears to be positive and statistically significant at the conventional significance levels. Thus, the findings are consistent with the view that weekend study time of more than one hour is associated with greater likelihood of academic achievement by about 0.32 points but weekend studying of less than one hour does not lead to any significant association between the two variables.

Table 3. Self-Reported Math GPA and Weekend Study Time of > 1 Hour

Table 4 reports the ordinary least squares regression results of the postulated association between weekend study time for more than 1 hour only and self-reported grade point of average of 5 th and 6 th grade students. The dependent variable self-reported science subject grade point average and the independent variable is weekend study time of more than one hour 3 . The weekend study time of more than one hour coefficient also appears to be positive and statistically significant at the conventional significance levels. Thus, the findings are consistent with the view that weekend study time of more than one hour is associated with greater likelihood of academic achievement in science field by about 0.26 points but weekend studying of less than one hour does not lead to any significant association between the two variables.

Table 4. Self-Reported GPA and Weekend Study Time > 1 Hour

Table 5 reports the ordinary least squares regression results of the postulated association between weekend study time for more than 1 hour only and self-reported grade point average of 5 th and 6 th grade students. The dependent variable ELA subject grade point average and the independent variable is weekend study time of more than one hour 3 . The weekend study time of more than one hour coefficient again appears to be positive and statistically significant at the conventional significance levels. Thus, the findings are consistent with the view that weekend study time of more than one hour is associated with greater likelihood of academic achievement in the ELA field by about 0.39 points, the most increase among the three subjects. However as in the previous results weekend studying of less than one hour does not lead to any significant association between the two variables.

Table 5. Self-Reported GPA and Weekend Study Time > 1 Hour

Table 6 reports the ordinary least squares regression results of the postulated association between weekend study time and parental involvement. The dependent variable is weekend study time and the explanatory variable is binary variable of parental involvement where a value of one indicates parental involvement and a value of zero indicates no involvement. The parental involvement coefficient appears to be negative and statistically significant at the one percent significance level. Thus, the findings are consistent with the view that parental involvement is associated with less weekend study time for 5 th and 6 th graders.

Table 6. Parental Involvement & Weekend Study

- Tables index View option Full Size Previous Table

5. Conclusions

We examine whether there is any association between academic success and weekend study time by comparing responses from public elementary school fifth and sixth grade students. The findings show that in general academic success is associated with more weekend study time. While findings are statistically significant, there appears to be no a significant association between academic success and weekend study time for all time interval reported. However, when we exclude the intervals reported less than one hour the results become statistically significant pointing to a positive association between weekend study time of more than one hour and self-reported grade point average for all of the three subject fields, math, science and ELA. The results are consistent with the view that generally it takes about one hour to focus on studying and as study time increases following the first hour productivity begins to increase. The most impact from studying during weekends is observed on the ELA subject followed by math and science fields, respectively. Lastly, the findings are consistent with the view that parental involvement, leads to less study time, giving students more time to undertake other activities such as extracurricular interests.

1. Does your Parent/Guardian/Other Family Member help you with your school work, homework or project? (if you get help only sometimes, please choose “Yes”)

2. If you answered Yes to question 1, state those days your work together with your Parent/Guardian/Other Family Member?

c. Wednesday

d. Thursday

f. Saturday

3. If you answered Yes to question 1, please state the length of the time on average per day spend for school work/homework/project? Please estimate.

a. 0 to 10 minutes

b. 10 to 20 minutes

c. 20 to 30 minutes

d. 30 to 45 minutes

e. 45 minutes to 1 hour

f. 1 hour to 1 and half hours

g. 1 and a half hours to 2 hours

h. 2 hours to 2 and a half hours

i. 2 and a half hours to 3 hours

j. 3 hours to 3 and a half hours

k. 3 and a half hours to 4 hours

l. Greater than 4 hours

m. If you wish to do so, you can write the more precise time here below in terms of minutes or hours ________

4. Current grade in Mathematics:

5. Current grade in Science:

6. Current grade in ELA:

8. Name of school you are attending:

a. Dennis Earl

c. Medeiros

e. Other (please specify) __________

9. Are you a student enrolled in the GATE program at your school?

10. Do you spend additional hours during the weekends for schoolwork/homework/project?

11. If you answered Yes to question 10, please state the weekend days spent for this purpose

a. Saturday

c. Both Saturday and Sunday

12. If you answered Yes to question 10, please state the average time spent per day during weekends.

13. Do you receive tutoring services from a paid individual/s?

14. If you answered Yes to question 13, please state the average time spent per day on paid tutoring by a separate individual

a. 0 to 30 minutes

b. 30 minutes to 1 hour

c. 1 hour to 1 and half hours

d. 1 and a half hours to 2 hours

e. 2 hours to 2 and a half hours

f. Greater than 2 and a half hours

Published with license by Science and Education Publishing, Copyright © 2021 Panos Petratos, Daniel Herrera and Emre Soydemir

Cite this article:

Normal style, chicago style.

- Google-plus

- View in article Full Size

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

Access provided by

Download started.

- PDF [1 MB] PDF [1 MB]

- Figure Viewer

- Download Figures (PPT)

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore

- Sing Chen Yeo, MSc Sing Chen Yeo Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

- Jacinda Tan, BSc Jacinda Tan Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

- Joshua J. Gooley, PhD Joshua J. Gooley Correspondence Corresponding author: Joshua J. Gooley, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders Program, Duke-NUS Medical School Singapore, 8 College Road, Singapore 117549, Singapore Contact Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

Participants

Measurements, conclusions.

- Sleep deprivation

Introduction

- Dewald J.F.

- Meijer A.M.

- Kerkhof G.A.

- Scopus (1036)

- Google Scholar

- Gooley J.J.

- Scopus (232)

- Chaput J.P.

- Poitras V.J.

- Scopus (543)

- Crowley S.J.

- Wolfson A.R.

- Carskadon M.A

- Scopus (390)

- Roenneberg T.

- Pramstaller P.P.

- Full Text PDF

- Scopus (1135)

- Achermann P.

- Scopus (351)

- Gradisar M.

- Scopus (80)

- Watson N.F.

- Martin J.L.

- Scopus (84)

- Robinson J.C.

- Scopus (667)

- Street N.W.

- McCormick M.C.

- Austin S.B.

- Scopus (16)

- Scopus (297)

- Scopus (299)

- Twenge J.M.

- Scopus (146)

- Galloway M.

- Scopus (66)

- Huang G.H.-.C.

- Scopus (121)

Participants and methods

Participants and data collection, assessment of sleep behavior and time use.

- Scopus (1328)

- Carskadon M.A.

- Scopus (562)

Assessment of depression symptoms

- Brooks S.J.

- Krulewicz S.P.

- Scopus (62)

Data analysis and statistics

- Fomberstein K.M.

- Razavi F.M.

- Scopus (56)

- Fuligni A.J.

- Scopus (237)

- Miller L.E.

- Scopus (439)

- Preacher K.J.

- Scopus (23296)

- Open table in a new tab

- View Large Image

- Download Hi-res image

- Download (PPT)

- Scopus (34)

- Scopus (17)

- Scopus (59)

- Scopus (164)

- Scopus (85)

- Maddison R.

- Scopus (61)

- Lushington K.

- Pallesen S.

- Stormark K.M.

- Jakobsen R.

- Lundervold A.J.

- Sivertsen B

- Scopus (350)

- Scopus (31)

- Afzali M.H.

- Scopus (224)

- Abramson L.Y

- Scopus (1256)

- Spaeth A.M.

- Scopus (110)

- Gillen-O'Neel C.

- Fuligni A.J

- Scopus (77)

- Felden E.P.

- Rebelatto C.F.

- Andrade R.D.

- Beltrame T.S

- Scopus (75)

- Twan D.C.K.

- Karamchedu S.

- Scopus (26)

Conflict of interest

Acknowledgments, appendix. supplementary materials.

- Download .docx (.51 MB) Help with docx files

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Article info

Publication history, identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.04.011

User license

For non-commercial purposes:

- Read, print & download

- Redistribute or republish the final article

- Text & data mine

- Translate the article (private use only, not for distribution)

- Reuse portions or extracts from the article in other works

Not Permitted

- Sell or re-use for commercial purposes

- Distribute translations or adaptations of the article

ScienceDirect

- Download .PPT

Related Articles

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Information

- Download Conflict of Interest Form

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Style Guidelines for In Memoriam

- Download Online Journal CME Program Application

- NSF CME Mission Statement

- Professional Practice Gaps in Sleep Health

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Activate Online Access

- Information for Advertisers

- Career Opportunities

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Press Releases

- More Periodicals

- Find a Periodical

- Go to Product Catalog

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Session Timeout (2:00)

Your session will expire shortly. If you are still working, click the ‘Keep Me Logged In’ button below. If you do not respond within the next minute, you will be automatically logged out.

- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

Managing Anxiety, Assignment & Exam Stress

Let’s start with the good news - experiencing some amount of stress or anxiety is an indication that you’re human. It’s how your body reacts to the demands and challenges it faces. It is natural to feel anxious prior to an exam or stressed while juggling assignment prep.

While stress and anxiety can sometimes be overwhelming, they can also be an energising and healthy pressure that encourages you to grow your capabilities and take control of your situation.

So how can you strike a balance between too little an too much stress? This blog will cover some techniques you can utilise to help reduce and manage your stress and anxiety levels during assignment periods and leading up to your exams.

Slow Down to Speed Up

When you're feeling overwhelmed, it's easy to fall into the trap of thinking that working harder and longer is the only solution. However, this can actually lead to burnout and a decline in your performance. By taking the time to slow down and prioritize your health, you can recharge your batteries and approach your work with renewed focus and energy.

There are many ways to slow down and take care of yourself, such as practising mindfulness, exercising regularly, getting enough sleep, and eating a healthy diet. These activities may seem like luxuries when you're under the pressure of exams and assignments, but they are essential for maintaining your mental and physical health.

Remember that your grades or your academic achievements do not define you. Taking care of yourself is a crucial part of your journey as a student, and it will ultimately help you achieve your goals in a more sustainable and fulfilling way. So, take a deep breath, slow down, and prioritize your health and well-being - it's the best investment you can make in your academic and personal success.

Early Bird or Night Owl?

Not everyone is the same, and no one size fits all when it comes to the best time of day for productivity. And it’s unproductive to try and force yourself to study when your focus and productivity levels are low. You are better off trying to try and use those times as your downtime to relax, catch up with friends, exercise, or do something you enjoy, and then make use of the times that work best for you.

Ask yourself these two questions:

- When during the day do I have the greatest amount of energy and concentration?

- When do I have the fewest interruptions and distractions?

For some, that might be first thing in the morning. For others, they might find the mornings challenging and have a habit of procrastinating until midday anyway. So rather than making yourself feel guilty for procrastinating, schedule in that time as downtime and kick off your studying session at midday.

Messy Workspace, Messy Headspace

The physical environment of your workplace has a significant effect on the way that you work. Cluttered spaces can have negative effects on our stress and anxiety levels, as well as our ability to focus, our eating choices, and even our sleep.

A Good Routine

Hopefully, you already have a good routine in place, but if not, there has never been a better time to start. Self-care doesn’t have to cost a lot of money or take up heaps of time. Start with the basics, making sure you get enough sleep, drink enough water, eat regular meals and snacks, and get in some movement or time outdoors. Then look to build on this through self-care that helps you to relax. Remember - relaxing is not one activity. It’s the outcome of that activity and how it makes you feel. And what works for your friends may not work for you. Experiment and see what works best for you! From journaling, reading, different types of exercise, stretching, and meditating, the options are endless. Pay attention to how you feel after each activity. Ask yourself, does this make me feel grounded and at ease? If so, schedule some time each day to help you shake off the tension of studying or to unwind after an exam.

Sleep!

Not only can sleep deprivation worsens anxiety, but getting enough sleep is vital to feeling and performing your best, which is particularly important around exam time. Don’t stay up late the night before or get up too early on the morning of. A good night’s sleep is more valuable than a few hours of revision.

Write Down Worries

It’s been proven that if you take a few moments to write about your fears just before you take an exam, it will help to reduce your anxiety and improve your performance. Write down what you are stressed about, why you are stressed, and what the outcome would be if those worries were realised. By writing down your worries, it can help you to put everything into perspective and help you to feel lighter and less tense by emptying your worries from your mind and onto the paper.

Move your Body

You don’t need to run a marathon every day, but the movement is just as key to a healthy mind as it is to a healthy body. Exercise is considered healthy stress on the body, which can actually help your body fight off the effects of stress. Exercise in almost any form can act as a stress reliever.

Reach Out for Support

Having people to lean on is great for your mental health. Make sure you let those close to you know if you are feeling overwhelmed or preparing for an upcoming exam. Not only can they help to support you emotionally, but they can also be on hand to help you in other ways (healthy study snacks, anyone!). If you don’t feel as though you have people in your life that understand your stress and anxiety, that’s what TalkCampus is for! Jump onto their global community and chat with other students that get it.

Midday Mindfulness 29 May – 24 Jul 2024

Weekly Rolling Group 29 May – 31 Jul 2024

Student Resources

Want to learn more about the services available to students? Check out the resources available below.

TalkCampus | Peer-based mental health support app

Have you downloaded the TalkCampus app yet? It's a free mental health support service available to all UNSW students.

Mental Health Connect

Need some help navigating your feelings? All enrolled students at UNSW are eligible for free mental health counselling. Mental Health Connect is here to connect you to the care you need.

UNSW Health News & Events

Stay up to date with the latest news, events, workshops and health resources from UNSW Health & Wellbeing.

- The Unheard Plight of Caregivers

The Psychology of Grit

- Singing Boosts Language Proficiency in Brains Impacted by Stroke

- 23-year-long study shows teenage loneliness increases adult mental illness risk by 20%

- Groupthink or Growth? Rethinking Decision-Making Dynamics in Teams

Your cart is empty

7 Ways to Manage Assignment Stress in Students

- by Psychologs Magazine

- April 3, 2024

- 5 minutes read

The experience of attending university may be both thrilling and stressful at the same time. Beginning college, tests, homework due dates, living with strangers, and future-focused thoughts can all cause stress. Stress is a normal emotion that is meant to assist you deal with difficult circumstances. It might be beneficial in moderation since it motivates you to put in your best effort and work hard—for example, during exams. However, extreme stress or the belief that you are unable to control your stress can result in mental health issues including anxiety and depression. It might also have an impact on your academic standing. Let’s find some effective strategies to help students manage assignment stress with some practical tips.

Students and Stress

Every student experiences stress at some point, whether it’s from having five assignments due on the same day or what seems like endless back-to-back tests. And you have to be superhuman if you don’t.

The American College Health Association (ACHA) reports that 12.7% of college students report having excessive stress, while 44.9% report having stress levels that are above normal. It’s normal for students to experience periods of extreme stress due to the numerous obligations and demands placed on them by their academic programs. However, you need to identify the source of your stress and learn coping mechanisms when it interferes with your everyday tasks.

Also Read: NMC Sets up National Task Force to Address Mental Health of medical students

Students may experience increased stress, and anxiety as a result of the pressure to serve well academically and complete their assignments. It can be extremely stressful to constantly, worry about turning in homework on time and getting good grades.

Here are the ways by which assignment stress can be reduced in College Students:

Making a study schedule:.

The reason most students fail or are unable to complete the given assignment at the right time is that they don’t have a study schedule that corresponds with their academic schedule. They underestimate the amount of study time required to complete tasks and overestimate the amount of time they have available. Also, they mistakenly believe they have enough time to finish their assignments on time because of their current schedule—or lack thereof. They begin too late, get behind, and ultimately take shortcuts. Reaching parity is nearly unattainable.

Making a study timetable is just meant to help you figure out when you have time to study, which will help you become more efficient at task scheduling. This implies that you must schedule time on your calendar for tasks other than studying. Stress levels rise, grades decline, and important time spent with friends, taking care of oneself, or spending time with family is lost.

Set Priority:

College students who prioritize their responsibilities will be more productive, organized, and less likely to feel overwhelmed. Setting priorities can also assist students in achieving their objectives, lowering stress, and managing their time better. You can know what homework assignments to perform and when to finish them if you prioritize your tasks. Setting priorities for your assignment will also aid you when making templates for your homework schedule and completing assignments before the due date.

Also Read: NIMHANS help tribal department for school students’ well-being and mental health

Time Management and Plan:

Although it requires discipline and experience, effective time management can greatly increase your productivity, lower your stress level, and help you succeed as a college student overall.

To keep your obligations, projects, and assignments organized, make a to-do list or utilize a task management app. Establish due dates for all of your tasks and make a realistic timetable that allows time for studying, going to class, finishing assignments, and taking breaks. Acknowledge that unforeseen circumstances or shifts in priorities can happen, and be ready to modify your goals and timetable as necessary. Be adaptable and modify your time management techniques to take into account new information.

Understanding what is required of you before taking on any projects, assignments, or chores lowers your chance of making mistakes. You can finish a task more quickly and accurately if you ask questions to clarify the topic. For instance, you can ask questions that lead to useful responses if an assignment isn’t giving you a sense of direction. Asking clarifying questions might also help you troubleshoot unclear instructions. This will aid in reducing the Anxiety and also improve the performance.

Maintaining your physical and mental health is essential while stressing over incomplete assignments. Exercise, which might include taking a stroll or any other physical activity, is one powerful self-care tactic. You can also de-stress by indulging in a hot bath or relaxing with calming music. Effective stress management techniques can include writing, mindfulness or meditation, and socializing with loved ones. Make sure you eat healthily, exercise frequently, get adequate sleep, and take breaks to refuel. Maintaining your mental well-being through mindfulness exercises or getting help when required can also keep you concentrated and productive.

Break Large Tasks into Smaller steps

It is beneficial to divide a large work into smaller, more manageable ingredients when faced with it. You can prevent tension and procrastination by doing this. Procrastinators frequently lament how overwhelming and unachievable the task seems when they wait until the last minute. If you are prone to procrastination, creating a prioritized to-do list could be beneficial. Work your way down the list, setting reasonable deadlines for yourself.

Even if something isn’t completed right away, there are situations when writing something down can make you feel better about it. As you complete the tasks at hand, make time for yourself to focus on them in short bursts. Multitasking or task-switching can be stressful in and of itself. The work is less daunting and more manageable when priorities are established and the larger project is divided into smaller tasks.

Also Read: Stress from pre-board exams among students: how to minimize exam stress?

Seek Professional Help

Professionals in mental health can offer evidence-based therapies, like counseling and medication, to assist manage symptoms and enhance general functioning. Higher levels of contentment, happiness, and life quality may result from this. Seek assistance before you feel that you can no longer manage the stress. Take the time to speak with a professional or find out what resources your school provides for mental health issues. A mental health specialist can identify the sources of your stress, create a mental health plan, and plan constructive strategies to manage stress.

At last, the idea behind assigning tasks comes from the way that pupils learn. It facilitates the assessment of students’ subject-matter comprehension by teachers. Assignments broaden their knowledge base and help them acquire a variety of practical abilities. Education experts say that if students acquire and hone these skills, learning a subject is not insurmountable. Moreover, having a hectic amount of assignments can drain your mental well-being. It’s also important to look after you through the ways of stress management.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9169886/

- https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/16-ways-relieve-stress-anxiety

Share This Post:

The role of chatbots in mental health services: how does it impact people, kolam and cognition, leave feedback about this cancel reply.

- Rating 5 4 3 2 1

Related Post

Exploring the Many Facets of Intelligence in Children

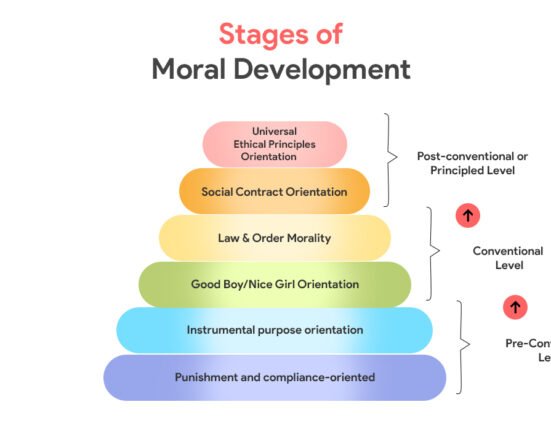

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

Exceptionality: Special Education Insights

Top 12 Psychology Books That Are A Must-Read

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

A Blog About Parenting: Coping Skills, Behavior Management and Special Needs

50 Best Stress-Relief Games and Activities for Students

Stress relief games and activities for students: Find effective ways to help your kids or students lower stress and deal with their big worries in healthy ways.

Stress arises when we face challenges or pressures that may seem beyond our ability to handle. It’s a reaction to feeling overwhelmed, a negative emotion that signals our body’s need to prepare for action or change.

Anxiety and stress share similarities as they both involve emotional responses to challenges or perceived threats. Stress tends to be a short-term response to a specific trigger, for example, exams or bullying. Anxiety, however, can linger even in the absence of the initial trigger.

This post explores practical stress management activities for students. We’ll cover strategies suitable for the classroom and others that may be more effectively practiced at home.

Stress and anxiety aren’t just challenges for adults; they’re very much part of kids’ lives, too.

A Gallup survey conducted from March 13 to 30, 2023, involving 2,430 U.S. college students in four-year programs, revealed that 66% reported feeling stressed, and 51% experienced worry during much of the preceding day.

A survey organized by the American College Health Association (ACHA ) identified key factors impacting students’ academic performance, including:

- Anxiety affecting 30.4% of the students

- Stress impacting 37.3% of the students.

Why Are Students Stressed Out?

Students might face stressful situations as a normal part of their day-to-day experiences, for example:

- Heavy workload : Assignments, projects, and studying can pile up.

- Exams : The pressure to perform well on tests can be overwhelming, so exams are often perceived as stressful events.

- Time management : Balancing school, activities, and personal life is challenging.

- Future concerns : Worrying about college admissions or career paths.

- Social pressures : Navigating friendships, social media, bullying, or peer competition.

- Personal issues : Dealing with personal or family health, relationships, or financial problems.

- Lack of sleep : Sacrificing sleep for study or activities leads to exhaustion.

- Limited relaxation : Not having enough time to relax or pursue hobbies.

- Learning difficulties : Struggling with course material or learning disabilities.

Signs of Stress in Students

Teachers may observe signs of stress in their students through behaviors and changes that manifest in the classroom environment:

- Lack of participation in students who used to be active

- Drop in grades or the quality of homework and classwork.

- Fidgeting, sweating, or signs of nervousness during presentations or tests.

- Withdrawal from classmates during group activities or social times like lunch.

- Reacting more emotionally or aggressively to feedback, criticism, or normal interactions.

- Headaches or stomachaches that lead to frequent visits to the school nurse.

- Signs of tiredness or lack of energy, possibly due to poor sleep.

- Struggle with focus and attention in class

- Difficulty completing tasks.

- Significant changes in behavior, such as starting conflicts or acting out.

- An increase in absences or lateness can be a sign of avoiding school due to stress

Benefits of Implementing Stress Relief Strategies in the Classroom

Students may benefit from stress relief games and activities. Potential advantages include:

- Reduce stress, helping students feel calmer and lower anxiety.

- Increase focus, leading to better learning and concentration.

- Break the monotony , making school more enjoyable.

- Build resilience by teaching different ways to handle stress.

- Promote mental health and well-being.

Stress-Relief Games and Activities for Students

Teach your kids or students some basic stress relief techniques. This section outlines essential skills and techniques complemented by a variety of stress-relief games and activities.

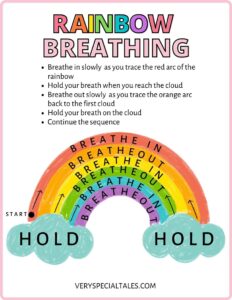

Deep Breathing / Breathing Exercises

Deep breathing skills would be a great addition to the school curriculum.

Deep breathing is one of the most effective yet easy-to-implement calming tools. Taking deep breaths lets your student manage stress discreetly without drawing attention or feeling embarrassed.

Turn it into a game by teaching them fun breathing techniques like the lion breathing or the bumble bee breathing. Other fun breathing techniques include using shapes (squares, triangles, stars, etc.) that the child will trace with their finger while practicing deep breathing.

Related: 14 Fun Breathing Exercises for Kids for Home or the Classroom

Tensing and Relaxing Muscles

Tensing and relaxing muscles is an effective stress relief technique. This method reduces stress by creating muscle tension and then releasing it, helping to ease the body’s stress symptoms.

Prepare DIY Stress Balls

Preparing stress balls can be a fun classroom activity. You can teach your students that squeezing and releasing a stress ball in their hand helps relieve tension (with an added benefit, as it also strengthens the muscles!)

The class can then create their own DIY stress balls (this DIY stress balls tutorial shows two simple ways to create them in less than three minutes).

Fidgeting may help some students focus and self-regulate.

Some research has shown that kids with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may find fidgeting beneficial, as physical movement may help concentration and focus.

If you wish to explore this topic further, I have a detailed post on using fidget toys in the classroom .

Mindfulness in The Classroom

“Mindfulness is the awareness that arises from paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally ” Kabat-Zinn.

Mindfulness practice can be a useful tool for helping kids of all ages regulate their emotions and control their impulses and worries.

Simple mindfulness games and activities can help you introduce and develop these skills in your children while they play and have fun.

In this article, we explore 20 great mindfulness activities for kids .

Physical Exercise

Regular physical activity can reduce symptoms of stress and anxiety.

Regular exercise promotes relaxation and enhances mood, offering immediate stress relief even in small amounts.

Teach Problem-Solving Skills

Teaching problem-solving skills can act as a stress reliever by equipping children with the ability to tackle challenges methodically and with confidence.

Explore with your students the key components of problem-solving:

- Identifying the problem

- Analyzing the problem

- Generating solutions

- Evaluating all possible solutions (Pros and Cons Analysis)

- Selecting the best solution based on our analysis and judgment.

- Implementing the best solution

- Monitoring progress and results

- Reflecting on the outcomes

Teach Planning and Organizational Skills

Teaching planning and organizational skills helps students manage their workload more effectively, reducing the feeling of being overwhelmed, which can lead to stress. These skills enable students to break tasks into manageable steps, prioritize their work, and meet deadlines more efficiently, fostering a sense of competence and reducing anxiety. Related reading: 30+ Time Management Tips & Activities for Kids

Coloring Activities

Research suggests that coloring or drawing activities may help reduce anxiety and decrease heart rate.

So, let your students grab a coloring book and see the negative feelings disappear while they engage in a creative activity.

Related reading:

- 18 Anxiety drawing ideas for kids (and adults!)

- Anxiety coloring pages for kids

Anxiety Affirmations

Anxiety affirmations are self-statements that we can use in situations that we perceive as a threat.

Those stressful situations may trigger negative thoughts that we can question with statements that

- challenge unhelpful thoughts

- focus on our strengths

- highlight personal values

- remind us of calming strategies to help us cope with physical symptoms

- contribute to a positive growth mindset

Two engaging activities that leverage the power of affirmations can bring creativity and positivity into the classroom:

- Creating Written Affirmations : This activity involves students writing their own positive affirmations. It’s a reflective exercise that encourages them to think about their strengths and aspirations, helping them build a positive mindset.

- Designing Affirmation Cards : Students can take a more artistic approach to creating affirmation cards. This involves both writing affirmations and decorating cards to reflect the positive message. It’s a creative way to engage with affirmations and adds a personal touch to their positive thoughts.