More From Forbes

4 social experiments that will improve your career.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

From a young age, I’ve been fascinated with how people meet and form relationships. While researching and writing The 2 AM Principle , I tested many famous theories and studies about human behavior.

These mini experiments and games provided essential insights for my career. Whether you are an entrepreneur trying to grow your business or someone trying to get ahead in their career, these experiments can help you understand your leadership style, make connections, and build confidence.

1. The Rejection Game

Human beings are overwhelmingly concerned with rejection. The fear of not being accepted stops us from taking many actions for our benefit. Yet, being turned down is never as bad as we think. The Rejection Game helps us realize this and overcome our fear.

It works like this: Go up to complete strangers and ask them for something that would seem worthy of a rejection. The request can be anything that puts you out of your comfort zone, but here are some examples to get started:

- Ask a random woman or man for their number.

- At a restaurant, ask a group if you can join them for dinner.

- Ask a stranger to run a race with you.

- Ask strangers to do the “Running Man”, “Nae/Nae” or some other dance fad with you.

- Ask someone at the gym to teach you their workout routine.

Will a percentage of people say no to you? Without a doubt, but it won’t be nearly as many as you think. You will realize how hard it is to get rejected, second you will toughen up and won’t fear rejection as much.

Social experiments can help boost your confidence and career.

2. The Favor Game

The favor game is similar to the rejection game. You ask people to perform favors for you but not for the sake of rejection. Instead, you ask for favors to understand how far strangers or acquaintances will go to support you. It is based on a concept popularized by Ben Franklin. To win over an adversary, Franklin asked for a favor: to borrow a rare book. The two men ended up becoming lifelong friends.

According to the Ben Franklin effect, we like people more when we do them favors because we have invested our time and given them support.

The key is to stack favors from small to large. If you ask people for directions, ask them for the time first. People will go surprisingly far to be helpful. They may lend you their car, help you move, lend you money and so on.

You will discover how much your community is willing to support and be there for you. If you discover that people aren’t willing to do favors for you, then your requests may be too large. Another possibility is that you haven't been a good friend or you’re spending time with the wrong people.

3. The “E” Test

As an indicator of leadership and perspective, Professors Adam Galinsky and Maurice Schweitzer , developed the “E” test. In it, a person is asked to trace the letter “E” on his or her forehead. Did you write the “E” so that other people could read it? According to Galinsky and Schweitzer, you are focused on others, which suggests that you consider the perspectives of those around you.

If you wrote it so that it can be read from your viewpoint, then you are self-focused, which is common in those in powerful positions. It is suggested that those who are focused on others may not have what it takes to be a ruthless leader, but it isn’t definite.

4. The Cash Register Experiment

In his book Give and Take , Wharton professor Adam Grant proposes that we assume other people are like ourselves. If you want to know how honest you or someone else is, ask a simple question: How much does the average store employee steal from their cash register?

Did you pick a big number or a small number? The higher the number, the less likely a person is to be honest. Once again, this experiment is suggestive but not definitive.

I have found these experiments and games invaluable. These insights have led me to invite a duty-free cashier in the Stockholm Airport to quit her job and travel the world with me after 10 seconds of meeting and befriend Kiefer Sutherland over a battle of Jenga. However, the greatest impact by far was on my confidence and ability to stay calm in any situation.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Social Psychology Experiments: 10 Of The Most Famous Studies

Ten of the most influential social psychology experiments explain why we sometimes do dumb or irrational things.

Ten of the most influential social psychology experiments explain why we sometimes do dumb or irrational things.

“I have been primarily interested in how and why ordinary people do unusual things, things that seem alien to their natures. Why do good people sometimes act evil? Why do smart people sometimes do dumb or irrational things?” –Philip Zimbardo

Like famous social psychologist Professor Philip Zimbardo (author of The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil ), I’m also obsessed with why we do dumb or irrational things.

The answer quite often is because of other people — something social psychologists have comprehensively shown.

Each of the 10 brilliant social psychology experiments below tells a unique, insightful story relevant to all our lives, every day.

Click the link in each social psychology experiment to get the full description and explanation of each phenomenon.

1. Social Psychology Experiments: The Halo Effect

The halo effect is a finding from a famous social psychology experiment.

It is the idea that global evaluations about a person (e.g. she is likeable) bleed over into judgements about their specific traits (e.g. she is intelligent).

It is sometimes called the “what is beautiful is good” principle, or the “physical attractiveness stereotype”.

It is called the halo effect because a halo was often used in religious art to show that a person is good.

2. Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort people feel when trying to hold two conflicting beliefs in their mind.

People resolve this discomfort by changing their thoughts to align with one of conflicting beliefs and rejecting the other.

The study provides a central insight into the stories we tell ourselves about why we think and behave the way we do.

3. Robbers Cave Experiment: How Group Conflicts Develop

The Robbers Cave experiment was a famous social psychology experiment on how prejudice and conflict emerged between two group of boys.

It shows how groups naturally develop their own cultures, status structures and boundaries — and then come into conflict with each other.

For example, each country has its own culture, its government, legal system and it draws boundaries to differentiate itself from neighbouring countries.

One of the reasons the became so famous is that it appeared to show how groups could be reconciled, how peace could flourish.

The key was the focus on superordinate goals, those stretching beyond the boundaries of the group itself.

4. Social Psychology Experiments: The Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford prison experiment was run to find out how people would react to being made a prisoner or prison guard.

The psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who led the Stanford prison experiment, thought ordinary, healthy people would come to behave cruelly, like prison guards, if they were put in that situation, even if it was against their personality.

It has since become a classic social psychology experiment, studied by generations of students and recently coming under a lot of criticism.

5. The Milgram Social Psychology Experiment

The Milgram experiment , led by the well-known psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, aimed to test people’s obedience to authority.

The results of Milgram’s social psychology experiment, sometimes known as the Milgram obedience study, continue to be both thought-provoking and controversial.

The Milgram experiment discovered people are much more obedient than you might imagine.

Fully 63 percent of the participants continued administering what appeared like electric shocks to another person while they screamed in agony, begged to stop and eventually fell silent — just because they were told to.

6. The False Consensus Effect

The false consensus effect is a famous social psychological finding that people tend to assume that others agree with them.

It could apply to opinions, values, beliefs or behaviours, but people assume others think and act in the same way as they do.

It is hard for many people to believe the false consensus effect exists because they quite naturally believe they are good ‘intuitive psychologists’, thinking it is relatively easy to predict other people’s attitudes and behaviours.

In reality, people show a number of predictable biases, such as the false consensus effect, when estimating other people’s behaviour and its causes.

7. Social Psychology Experiments: Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory helps to explain why people’s behaviour in groups is fascinating and sometimes disturbing.

People gain part of their self from the groups they belong to and that is at the heart of social identity theory.

The famous theory explains why as soon as humans are bunched together in groups we start to do odd things: copy other members of our group, favour members of own group over others, look for a leader to worship and fight other groups.

8. Negotiation: 2 Psychological Strategies That Matter Most

Negotiation is one of those activities we often engage in without quite realising it.

Negotiation doesn’t just happen in the boardroom, or when we ask our boss for a raise or down at the market, it happens every time we want to reach an agreement with someone.

In a classic, award-winning series of social psychology experiments, Morgan Deutsch and Robert Krauss investigated two central factors in negotiation: how we communicate with each other and how we use threats.

9. Bystander Effect And The Diffusion Of Responsibility

The bystander effect in social psychology is the surprising finding that the mere presence of other people inhibits our own helping behaviours in an emergency.

The bystander effect social psychology experiments are mentioned in every psychology textbook and often dubbed ‘seminal’.

This famous social psychology experiment on the bystander effect was inspired by the highly publicised murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964.

It found that in some circumstances, the presence of others inhibits people’s helping behaviours — partly because of a phenomenon called diffusion of responsibility.

10. Asch Conformity Experiment: The Power Of Social Pressure

The Asch conformity experiments — some of the most famous every done — were a series of social psychology experiments carried out by noted psychologist Solomon Asch.

The Asch conformity experiment reveals how strongly a person’s opinions are affected by people around them.

In fact, the Asch conformity experiment shows that many of us will deny our own senses just to conform with others.

Author: Dr Jeremy Dean

Psychologist, Jeremy Dean, PhD is the founder and author of PsyBlog. He holds a doctorate in psychology from University College London and two other advanced degrees in psychology. He has been writing about scientific research on PsyBlog since 2004. View all posts by Dr Jeremy Dean

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.

The Science of Improving Motivation at Work

The topic of employee motivation can be quite daunting for managers, leaders, and human resources professionals.

Organizations that provide their members with meaningful, engaging work not only contribute to the growth of their bottom line, but also create a sense of vitality and fulfillment that echoes across their organizational cultures and their employees’ personal lives.

“An organization’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

In the context of work, an understanding of motivation can be applied to improve employee productivity and satisfaction; help set individual and organizational goals; put stress in perspective; and structure jobs so that they offer optimal levels of challenge, control, variety, and collaboration.

This article demystifies motivation in the workplace and presents recent findings in organizational behavior that have been found to contribute positively to practices of improving motivation and work life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in the workplace, motivation theories in organizational behavior, employee motivation strategies, motivation and job performance, leadership and motivation, motivation and good business, a take-home message.

Motivation in the workplace has been traditionally understood in terms of extrinsic rewards in the form of compensation, benefits, perks, awards, or career progression.

With today’s rapidly evolving knowledge economy, motivation requires more than a stick-and-carrot approach. Research shows that innovation and creativity, crucial to generating new ideas and greater productivity, are often stifled when extrinsic rewards are introduced.

Daniel Pink (2011) explains the tricky aspect of external rewards and argues that they are like drugs, where more frequent doses are needed more often. Rewards can often signal that an activity is undesirable.

Interesting and challenging activities are often rewarding in themselves. Rewards tend to focus and narrow attention and work well only if they enhance the ability to do something intrinsically valuable. Extrinsic motivation is best when used to motivate employees to perform routine and repetitive activities but can be detrimental for creative endeavors.

Anticipating rewards can also impair judgment and cause risk-seeking behavior because it activates dopamine. We don’t notice peripheral and long-term solutions when immediate rewards are offered. Studies have shown that people will often choose the low road when chasing after rewards because addictive behavior is short-term focused, and some may opt for a quick win.

Pink (2011) warns that greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible, and seven deadly flaws of rewards are soon to follow. He found that anticipating rewards often has undesirable consequences and tends to:

- Extinguish intrinsic motivation

- Decrease performance

- Encourage cheating

- Decrease creativity

- Crowd out good behavior

- Become addictive

- Foster short-term thinking

Pink (2011) suggests that we should reward only routine tasks to boost motivation and provide rationale, acknowledge that some activities are boring, and allow people to complete the task their way. When we increase variety and mastery opportunities at work, we increase motivation.

Rewards should be given only after the task is completed, preferably as a surprise, varied in frequency, and alternated between tangible rewards and praise. Providing information and meaningful, specific feedback about the effort (not the person) has also been found to be more effective than material rewards for increasing motivation (Pink, 2011).

They have shaped the landscape of our understanding of organizational behavior and our approaches to employee motivation. We discuss a few of the most frequently applied theories of motivation in organizational behavior.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation, also known as dual-factor theory or motivation-hygiene theory, was a result of a study that analyzed responses of 200 accountants and engineers who were asked about their positive and negative feelings about their work. Herzberg (1959) concluded that two major factors influence employee motivation and satisfaction with their jobs:

- Motivator factors, which can motivate employees to work harder and lead to on-the-job satisfaction, including experiences of greater engagement in and enjoyment of the work, feelings of recognition, and a sense of career progression

- Hygiene factors, which can potentially lead to dissatisfaction and a lack of motivation if they are absent, such as adequate compensation, effective company policies, comprehensive benefits, or good relationships with managers and coworkers

Herzberg (1959) maintained that while motivator and hygiene factors both influence motivation, they appeared to work entirely independently of each other. He found that motivator factors increased employee satisfaction and motivation, but the absence of these factors didn’t necessarily cause dissatisfaction.

Likewise, the presence of hygiene factors didn’t appear to increase satisfaction and motivation, but their absence caused an increase in dissatisfaction. It is debatable whether his theory would hold true today outside of blue-collar industries, particularly among younger generations, who may be looking for meaningful work and growth.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory proposed that employees become motivated along a continuum of needs from basic physiological needs to higher level psychological needs for growth and self-actualization . The hierarchy was originally conceptualized into five levels:

- Physiological needs that must be met for a person to survive, such as food, water, and shelter

- Safety needs that include personal and financial security, health, and wellbeing

- Belonging needs for friendships, relationships, and family

- Esteem needs that include feelings of confidence in the self and respect from others

- Self-actualization needs that define the desire to achieve everything we possibly can and realize our full potential

According to the hierarchy of needs, we must be in good health, safe, and secure with meaningful relationships and confidence before we can reach for the realization of our full potential.

For a full discussion of other theories of psychological needs and the importance of need satisfaction, see our article on How to Motivate .

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne effect, named after a series of social experiments on the influence of physical conditions on productivity at Western Electric’s factory in Hawthorne, Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s, was first described by Henry Landsberger in 1958 after he noticed some people tended to work harder and perform better when researchers were observing them.

Although the researchers changed many physical conditions throughout the experiments, including lighting, working hours, and breaks, increases in employee productivity were more significant in response to the attention being paid to them, rather than the physical changes themselves.

Today the Hawthorne effect is best understood as a justification for the value of providing employees with specific and meaningful feedback and recognition. It is contradicted by the existence of results-only workplace environments that allow complete autonomy and are focused on performance and deliverables rather than managing employees.

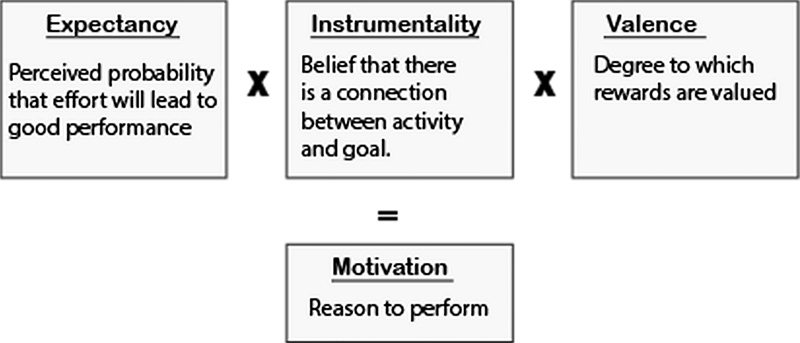

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory proposes that we are motivated by our expectations of the outcomes as a result of our behavior and make a decision based on the likelihood of being rewarded for that behavior in a way that we perceive as valuable.

For example, an employee may be more likely to work harder if they have been promised a raise than if they only assumed they might get one.

Expectancy theory posits that three elements affect our behavioral choices:

- Expectancy is the belief that our effort will result in our desired goal and is based on our past experience and influenced by our self-confidence and anticipation of how difficult the goal is to achieve.

- Instrumentality is the belief that we will receive a reward if we meet performance expectations.

- Valence is the value we place on the reward.

Expectancy theory tells us that we are most motivated when we believe that we will receive the desired reward if we hit an achievable and valued target, and least motivated if we do not care for the reward or do not believe that our efforts will result in the reward.

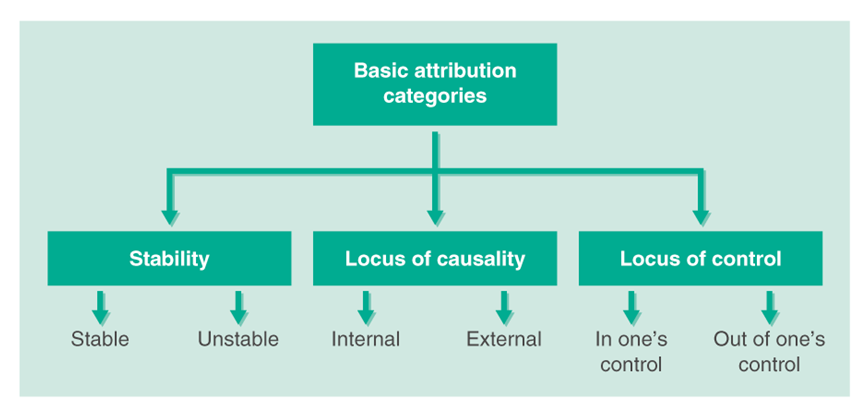

Three-dimensional theory of attribution

Attribution theory explains how we attach meaning to our own and other people’s behavior and how the characteristics of these attributions can affect future motivation.

Bernard Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution proposes that the nature of the specific attribution, such as bad luck or not working hard enough, is less important than the characteristics of that attribution as perceived and experienced by the individual. According to Weiner, there are three main characteristics of attributions that can influence how we behave in the future:

Stability is related to pervasiveness and permanence; an example of a stable factor is an employee believing that they failed to meet the expectation because of a lack of support or competence. An unstable factor might be not performing well due to illness or a temporary shortage of resources.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

According to Weiner, stable attributions for successful achievements can be informed by previous positive experiences, such as completing the project on time, and can lead to positive expectations and higher motivation for success in the future. Adverse situations, such as repeated failures to meet the deadline, can lead to stable attributions characterized by a sense of futility and lower expectations in the future.

Locus of control describes a perspective about the event as caused by either an internal or an external factor. For example, if the employee believes it was their fault the project failed, because of an innate quality such as a lack of skills or ability to meet the challenge, they may be less motivated in the future.

If they believe an external factor was to blame, such as an unrealistic deadline or shortage of staff, they may not experience such a drop in motivation.

Controllability defines how controllable or avoidable the situation was. If an employee believes they could have performed better, they may be less motivated to try again in the future than someone who believes that factors outside of their control caused the circumstances surrounding the setback.

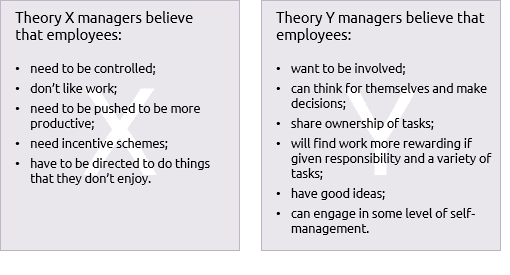

Theory X and theory Y

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories to describe managerial views on employee motivation: theory X and theory Y. These views of employee motivation have drastically different implications for management.

He divided leaders into those who believe most employees avoid work and dislike responsibility (theory X managers) and those who say that most employees enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace (theory Y managers).

To motivate theory X employees, the company needs to push and control their staff through enforcing rules and implementing punishments.

Theory Y employees, on the other hand, are perceived as consciously choosing to be involved in their work. They are self-motivated and can exert self-management, and leaders’ responsibility is to create a supportive environment and develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity.

Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation and the role that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

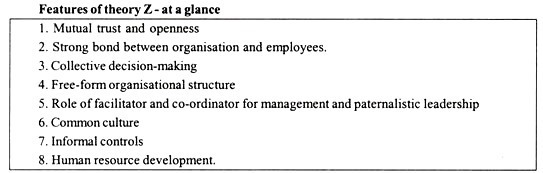

Taking theory X and theory Y as a starting point, theory Z was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. The theory combines American and Japanese management philosophies and focuses on long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

Its noble goals include increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life, focusing on the employee’s wellbeing, and encouraging group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

There are several implications of these numerous theories on ways to motivate employees. They vary with whatever perspectives leadership ascribes to motivation and how that is cascaded down and incorporated into practices, policies, and culture.

The effectiveness of these approaches is further determined by whether individual preferences for motivation are considered. Nevertheless, various motivational theories can guide our focus on aspects of organizational behavior that may require intervening.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory , for example, implies that for the happiest and most productive workforce, companies need to work on improving both motivator and hygiene factors.

The theory suggests that to help motivate employees, the organization must ensure that everyone feels appreciated and supported, is given plenty of specific and meaningful feedback, and has an understanding of and confidence in how they can grow and progress professionally.

To prevent job dissatisfaction, companies must make sure to address hygiene factors by offering employees the best possible working conditions, fair pay, and supportive relationships.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs , on the other hand, can be used to transform a business where managers struggle with the abstract concept of self-actualization and tend to focus too much on lower level needs. Chip Conley, the founder of the Joie de Vivre hotel chain and head of hospitality at Airbnb, found one way to address this dilemma by helping his employees understand the meaning of their roles during a staff retreat.

In one exercise, he asked groups of housekeepers to describe themselves and their job responsibilities by giving their group a name that reflects the nature and the purpose of what they were doing. They came up with names such as “The Serenity Sisters,” “The Clutter Busters,” and “The Peace of Mind Police.”

These designations provided a meaningful rationale and gave them a sense that they were doing more than just cleaning, instead “creating a space for a traveler who was far away from home to feel safe and protected” (Pattison, 2010). By showing them the value of their roles, Conley enabled his employees to feel respected and motivated to work harder.

The Hawthorne effect studies and Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution have implications for providing and soliciting regular feedback and praise. Recognizing employees’ efforts and providing specific and constructive feedback in the areas where they can improve can help prevent them from attributing their failures to an innate lack of skills.

Praising employees for improvement or using the correct methodology, even if the ultimate results were not achieved, can encourage them to reframe setbacks as learning opportunities. This can foster an environment of psychological safety that can further contribute to the view that success is controllable by using different strategies and setting achievable goals .

Theories X, Y, and Z show that one of the most impactful ways to build a thriving organization is to craft organizational practices that build autonomy, competence, and belonging. These practices include providing decision-making discretion, sharing information broadly, minimizing incidents of incivility, and offering performance feedback.

Being told what to do is not an effective way to negotiate. Having a sense of autonomy at work fuels vitality and growth and creates environments where employees are more likely to thrive when empowered to make decisions that affect their work.

Feedback satisfies the psychological need for competence. When others value our work, we tend to appreciate it more and work harder. Particularly two-way, open, frequent, and guided feedback creates opportunities for learning.

Frequent and specific feedback helps people know where they stand in terms of their skills, competencies, and performance, and builds feelings of competence and thriving. Immediate, specific, and public praise focusing on effort and behavior and not traits is most effective. Positive feedback energizes employees to seek their full potential.

Lack of appreciation is psychologically exhausting, and studies show that recognition improves health because people experience less stress. In addition to being acknowledged by their manager, peer-to-peer recognition was shown to have a positive impact on the employee experience (Anderson, 2018). Rewarding the team around the person who did well and giving more responsibility to top performers rather than time off also had a positive impact.

Stop trying to motivate your employees – Kerry Goyette

Other approaches to motivation at work include those that focus on meaning and those that stress the importance of creating positive work environments.

Meaningful work is increasingly considered to be a cornerstone of motivation. In some cases, burnout is not caused by too much work, but by too little meaning. For many years, researchers have recognized the motivating potential of task significance and doing work that affects the wellbeing of others.

All too often, employees do work that makes a difference but never have the chance to see or to meet the people affected. Research by Adam Grant (2013) speaks to the power of long-term goals that benefit others and shows how the use of meaning to motivate those who are not likely to climb the ladder can make the job meaningful by broadening perspectives.

Creating an upbeat, positive work environment can also play an essential role in increasing employee motivation and can be accomplished through the following:

- Encouraging teamwork and sharing ideas

- Providing tools and knowledge to perform well

- Eliminating conflict as it arises

- Giving employees the freedom to work independently when appropriate

- Helping employees establish professional goals and objectives and aligning these goals with the individual’s self-esteem

- Making the cause and effect relationship clear by establishing a goal and its reward

- Offering encouragement when workers hit notable milestones

- Celebrating employee achievements and team accomplishments while avoiding comparing one worker’s achievements to those of others

- Offering the incentive of a profit-sharing program and collective goal setting and teamwork

- Soliciting employee input through regular surveys of employee satisfaction

- Providing professional enrichment through providing tuition reimbursement and encouraging employees to pursue additional education and participate in industry organizations, skills workshops, and seminars

- Motivating through curiosity and creating an environment that stimulates employee interest to learn more

- Using cooperation and competition as a form of motivation based on individual preferences

Sometimes, inexperienced leaders will assume that the same factors that motivate one employee, or the leaders themselves, will motivate others too. Some will make the mistake of introducing de-motivating factors into the workplace, such as punishment for mistakes or frequent criticism, but negative reinforcement rarely works and often backfires.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

There are several positive psychology interventions that can be used in the workplace to improve important outcomes, such as reduced job stress and increased motivation, work engagement, and job performance. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted in recent years to verify the effects of these interventions.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Psychological capital interventions

Psychological capital interventions are associated with a variety of work outcomes that include improved job performance, engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey, 2014; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan 2017). Psychological capital refers to a psychological state that is malleable and open to development and consists of four major components:

- Self-efficacy and confidence in our ability to succeed at challenging work tasks

- Optimism and positive attributions about the future of our career or company

- Hope and redirecting paths to work goals in the face of obstacles

- Resilience in the workplace and bouncing back from adverse situations (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017)

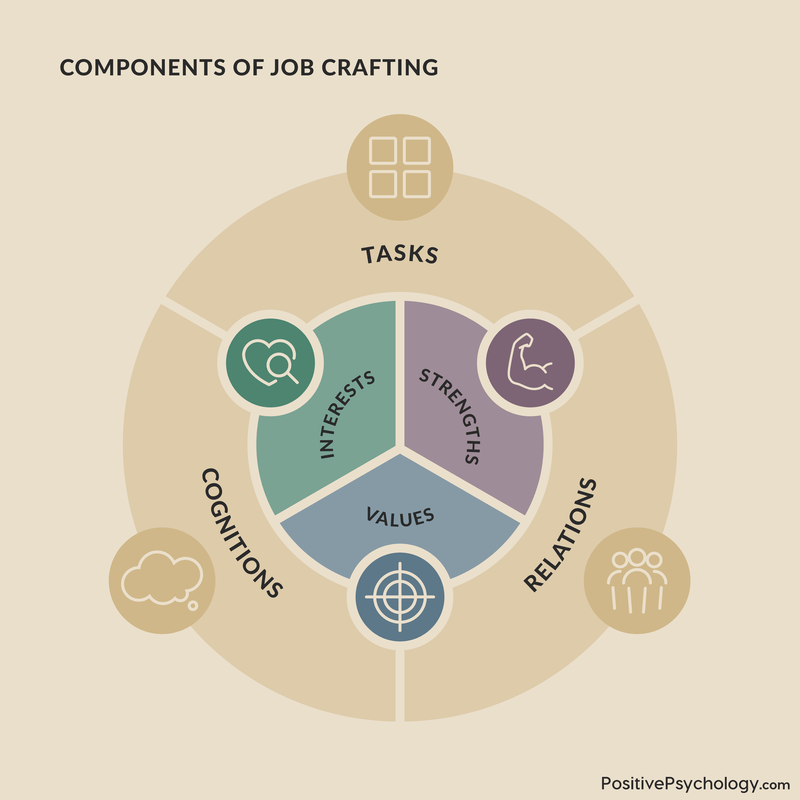

Job crafting interventions

Job crafting interventions – where employees design and have control over the characteristics of their work to create an optimal fit between work demands and their personal strengths – can lead to improved performance and greater work engagement (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012; van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016).

The concept of job crafting is rooted in the jobs demands–resources theory and suggests that employee motivation, engagement, and performance can be influenced by practices such as (Bakker et al., 2012):

- Attempts to alter social job resources, such as feedback and coaching

- Structural job resources, such as opportunities to develop at work

- Challenging job demands, such as reducing workload and creating new projects

Job crafting is a self-initiated, proactive process by which employees change elements of their jobs to optimize the fit between their job demands and personal needs, abilities, and strengths (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Today’s motivation research shows that participation is likely to lead to several positive behaviors as long as managers encourage greater engagement, motivation, and productivity while recognizing the importance of rest and work recovery.

One key factor for increasing work engagement is psychological safety (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety allows an employee or team member to engage in interpersonal risk taking and refers to being able to bring our authentic self to work without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Edmondson, 1999).

When employees perceive psychological safety, they are less likely to be distracted by negative emotions such as fear, which stems from worrying about controlling perceptions of managers and colleagues.

Dealing with fear also requires intense emotional regulation (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003), which takes away from the ability to fully immerse ourselves in our work tasks. The presence of psychological safety in the workplace decreases such distractions and allows employees to expend their energy toward being absorbed and attentive to work tasks.

Effective structural features, such as coaching leadership and context support, are some ways managers can initiate psychological safety in the workplace (Hackman, 1987). Leaders’ behavior can significantly influence how employees behave and lead to greater trust (Tyler & Lind, 1992).

Supportive, coaching-oriented, and non-defensive responses to employee concerns and questions can lead to heightened feelings of safety and ensure the presence of vital psychological capital.

Another essential factor for increasing work engagement and motivation is the balance between employees’ job demands and resources.

Job demands can stem from time pressures, physical demands, high priority, and shift work and are not necessarily detrimental. High job demands and high resources can both increase engagement, but it is important that employees perceive that they are in balance, with sufficient resources to deal with their work demands (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010).

Challenging demands can be very motivating, energizing employees to achieve their goals and stimulating their personal growth. Still, they also require that employees be more attentive and absorbed and direct more energy toward their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Unfortunately, when employees perceive that they do not have enough control to tackle these challenging demands, the same high demands will be experienced as very depleting (Karasek, 1979).

This sense of perceived control can be increased with sufficient resources like managerial and peer support and, like the effects of psychological safety, can ensure that employees are not hindered by distraction that can limit their attention, absorption, and energy.

The job demands–resources occupational stress model suggests that job demands that force employees to be attentive and absorbed can be depleting if not coupled with adequate resources, and shows how sufficient resources allow employees to sustain a positive level of engagement that does not eventually lead to discouragement or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

And last but not least, another set of factors that are critical for increasing work engagement involves core self-evaluations and self-concept (Judge & Bono, 2001). Efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control, identity, and perceived social impact may be critical drivers of an individual’s psychological availability, as evident in the attention, absorption, and energy directed toward their work.

Self-esteem and efficacy are enhanced by increasing employees’ general confidence in their abilities, which in turn assists in making them feel secure about themselves and, therefore, more motivated and engaged in their work (Crawford et al., 2010).

Social impact, in particular, has become increasingly important in the growing tendency for employees to seek out meaningful work. One such example is the MBA Oath created by 25 graduating Harvard business students pledging to lead professional careers marked with integrity and ethics:

The MBA oath

“As a business leader, I recognize my role in society.

My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow. Therefore, I promise that:

- I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

- I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

- I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

- I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

- I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

- I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

- I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust, and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards. This oath, I make freely, and upon my honor.”

Job crafting is the process of personalizing work to better align with one’s strengths, values, and interests (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Any job, at any level can be ‘crafted,’ and a well-crafted job offers more autonomy, deeper engagement and improved overall wellbeing.

There are three types of job crafting:

- Task crafting involves adding or removing tasks, spending more or less time on certain tasks, or redesigning tasks so that they better align with your core strengths (Berg et al., 2013).

- Relational crafting includes building, reframing, and adapting relationships to foster meaningfulness (Berg et al., 2013).

- Cognitive crafting defines how we think about our jobs, including how we perceive tasks and the meaning behind them.

If you would like to guide others through their own unique job crafting journey, our set of Job Crafting Manuals (PDF) offer a ready-made 7-session coaching trajectory.

Prosocial motivation is an important driver behind many individual and collective accomplishments at work.

It is a strong predictor of persistence, performance, and productivity when accompanied by intrinsic motivation. Prosocial motivation was also indicative of more affiliative citizenship behaviors when it was accompanied by motivation toward impression management motivation and was a stronger predictor of job performance when managers were perceived as trustworthy (Ciulla, 2000).

On a day-to-day basis most jobs can’t fill the tall order of making the world better, but particular incidents at work have meaning because you make a valuable contribution or you are able to genuinely help someone in need.

J. B. Ciulla

Prosocial motivation was shown to enhance the creativity of intrinsically motivated employees, the performance of employees with high core self-evaluations, and the performance evaluations of proactive employees. The psychological mechanisms that enable this are the importance placed on task significance, encouraging perspective taking, and fostering social emotions of anticipated guilt and gratitude (Ciulla, 2000).

Some argue that organizations whose products and services contribute to positive human growth are examples of what constitutes good business (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004). Businesses with a soul are those enterprises where employees experience deep engagement and develop greater complexity.

In these unique environments, employees are provided opportunities to do what they do best. In return, their organizations reap the benefits of higher productivity and lower turnover, as well as greater profit, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety. Most importantly, however, the level of engagement, involvement, or degree to which employees are positively stretched contributes to the experience of wellbeing at work (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004).

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Daniel Pink (2011) argues that when it comes to motivation, management is the problem, not the solution, as it represents antiquated notions of what motivates people. He claims that even the most sophisticated forms of empowering employees and providing flexibility are no more than civilized forms of control.

He gives an example of companies that fall under the umbrella of what is known as results-only work environments (ROWEs), which allow all their employees to work whenever and wherever they want as long their work gets done.

Valuing results rather than face time can change the cultural definition of a successful worker by challenging the notion that long hours and constant availability signal commitment (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011).

Studies show that ROWEs can increase employees’ control over their work schedule; improve work–life fit; positively affect employees’ sleep duration, energy levels, self-reported health, and exercise; and decrease tobacco and alcohol use (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

Perhaps this type of solution sounds overly ambitious, and many traditional working environments are not ready for such drastic changes. Nevertheless, it is hard to ignore the quickly amassing evidence that work environments that offer autonomy, opportunities for growth, and pursuit of meaning are good for our health, our souls, and our society.

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

Related reading: Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Anderson, D. (2018, February 22). 11 Surprising statistics about employee recognition [infographic]. Best Practice in Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.bestpracticeinhr.com/11-surprising-statistics-about-employee-recognition-infographic/

- Avey, J. B. (2014). The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21( 2), 141–149.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (vol. 3). John Wiley and Sons.

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations , 65 (10), 1359–1378

- Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3–52). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104) . American Psychological Association.

- Ciulla, J. B. (2000). The working life: The promise and betrayal of modern work. Three Rivers Press.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 (5), 834–848.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology , 863) , 499–512.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly , 44 (2), 350–383.

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin.

- Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 315–342). Prentice-Hall.

- Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (1), 80–92.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal , 33 (4), 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (2), 285–308.

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review , 76 (2), 265–290.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management and the worker, its critics, and developments in human relations in industry. Cornell University.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4 , 339-366.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Lam, J. (2013). Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of occupational health psychology, 18 (2), 157.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E., Tranby, E., & Huang, Q. (2011). Changing work, changing health: Can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429.

- Pattison, K. (2010, August 26). Chip Conley took the Maslow pyramid, made it an employee pyramid and saved his company. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/1685009/chip-conley-took-maslow-pyramid-made-it-employee-pyramid-and-saved-his-company

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2) , 1-9.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 25) (pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

- von Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands–resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 31 (3), 686–701.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26 (2), 179–201.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Good and helpful study thank you. It will help achieving goals for my clients. Thank you for this information

A lot of data is really given. Validation is correct. The next step is the exchange of knowledge in order to create an optimal model of motivation.

A good article, thank you for sharing. The views and work by the likes of Daniel Pink, Dan Ariely, Barry Schwartz etc have really got me questioning and reflecting on my own views on workplace motivation. There are far too many organisations and leaders who continue to rely on hedonic principles for motivation (until recently, myself included!!). An excellent book which shares these modern views is ‘Primed to Perform’ by Doshi and McGregor (2015). Based on the earlier work of Deci and Ryan’s self determination theory the book explores the principle of ‘why people work, determines how well they work’. A easy to read and enjoyable book that offers a very practical way of applying in the workplace.

Thanks for mentioning that. Sounds like a good read.

All the best, Annelé

Motivation – a piece of art every manager should obtain and remember by heart and continue to embrace.

Exceptionally good write-up on the subject applicable for personal and professional betterment. Simplified theorem appeals to think and learn at least one thing that means an inspiration to the reader. I appreciate your efforts through this contributive work.

Excelente artículo sobre motivación. Me inspira. Gracias

Very helpful for everyone studying motivation right now! It’s brilliant the way it’s witten and also brought to the reader. Thank you.

Such a brilliant piece! A super coverage of existing theories clearly written. It serves as an excellent overview (or reminder for those of us who once knew the older stuff by heart!) Thank you!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Encourage Clients to Embrace Change

Many of us struggle with change, especially when it’s imposed upon us rather than chosen. Yet despite its inevitability, without it, there would be no [...]

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

Daring Leadership Institute: a groundbreaking partnership that amplifies Brené Brown's empirically based, courage-building curriculum with BetterUp’s human transformation platform.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Find your coach

-1.png)

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

Experimentation brings innovation: Create an experimental workplace

Jump to section

What’s experimentation in the workplace?

Why you should foster a culture of experimentation

How to build a culture of experimentation: 8 ways.

Confronting the challenges of innovation

Success through failure

In an increasingly noisy digital age, you need your product or service to stand out so people choose you over other companies.

To find solutions that get your target audience’s attention, you can foster a culture of experimentation in your workforce. Allowing employees to try — and fail — is how you’ll find innovative ideas that change the game.

What’s experimentation in the workplace?

Experimentation in the workplace involves asking employees to question the status quo, try out ideas even if they fear failure , and embrace change . Leaders also encourage cross-departmental brainstorming to break down silos which increases the chance teams land on innovative ideas brought about through collaboration.

Encouraging experimentation also involves bringing together unique perspectives across professional hierarchies. Managers encourage upward communication from entry-level employees about what to try and procedures to change. And leaders might ask staff of every level to present their ideas, trials, and failures to team members.

An experimental workforce also prioritizes research on industry trends and innovations to pivot quickly when new technologies arise. They try to be one of the first companies to embrace these advancements.

Pinning innovation into the fabric of your business requires drive, conviction, and constantly returning to the drawing board. But it pays off. Here are a few benefits of encouraging experimentation in your workforce:

- Saves you money: Trying out ideas helps you decide if a solution is worth investing in. Rather than diving into the market headfirst with all your resources, experimentation separates good ideas from bad ones.

- Increases everyone’s knowledge: Open brainstorming and testing expand your business’s cognitive diversity. The more comfortable people feel sharing, the wider the pool of experiences and perspectives all employees can learn from.

- Provides a way to implement systematic changes: Experiments allow you to systematically break down changes into smaller pieces. Rather than launching a complex new service, you can progressively build, test, modify, and release interventions.

- Drives growth: A ccording to a study by McKinse y, crisis-fueled experimentation was the main driver of organic growth for companies during the pandemic . Companies that refocused quickly, invested more resources, and experimented with new technologies accelerated faster than others.

- Everyone enjoys greater success: The quicker you fai l, the faster you'll reach success if you’re resilient . So leaders who make their staff feel comfortable rather than afraid of the occasional disapp ointment increase their chance of success.

- Increases employee retention : Employees want to feel valued at work . And you can showcase this value by listening to and trying out their ideas.

- Boosts employee morale: A/B testing allows employees to clearly see their accomplishments because of the quantified results . They can also more easily share this information — in a spreadsheet, during a presentation — than qualitative accomplishments like “My yearly review went very well.”

- Encourages curiosity: Inquisitive employees are more likely to ask deeper questions and avoid “status quo” solutions. This curiosity can lead them to unique ideas or problem-solving outcomes compared to staff that are encouraged to think inside the box.

Unironically, creating a culture of experimentation involves running experiments to fig ure out what works best for your business. Here are eight methods for encouraging innovation at work:

1. Practice humility

Humility in leadership means accepting your knowledge gaps and mistakes. And when you’re vulnerable with your staff and admit you don’t have all the answers, you gain their trust and make them feel comfortable trying out ideas .

A fundamental step in creating a culture of experimentation is opening the floor to everybody in the organization. Rather than taking charge of brainstorming or being responsible for coming up with every solution, step aside and listen to help workers fine-tune their ideas.

2. Make failure your friend

In a culture of experimentation, everything won’t go as planned. But that’s the point. Experimentation shows you the right path to innovation by illuminating the roads that lead to nowhere.

When you accept failure as part of the process and not a roadblock to success, you also build important soft skills . This includes being cognitively flexible , resilient to challenges , and motivated to tackle tasks and achieve goals .

3. Drive with data

You can’t test ideas if you don’t know where you currently stand in your market. You won’t know who you’re targeting and how to measure success. So conduct market research and assess customer data to understand where your solution fits.

If your marketing department doesn’t have a dedicated team of research analysts, consider hiring a consultant. They’ll help run controlled experiments, build case studies, and outline risks and benefits. This allows you to unify subjective ideas with data-driven insights to launch effective and creative solutions .

4. Don’t reinvent the wheel

Your team doesn’t need to invent an entirely new solution to your target audience’s problem. Experimentation also involves improving current products and services. You’ll try out several tweaks to a current offering to see whether it satisfies your clients even more.

Workplace experimentation could even be internally-focused. You might rearrange in-office seating to see how it affects productivity or experiment with a new conferencing system during hybrid meetings . Encourage experimentation in your workforce by constantly trying new things to find the most effective option.

5. Encourage initiative

Clarify for everyone in the company that you’ll reward those who show initiative — no matter the experiment results. This public encouragement builds their confidence to follow through on instincts, share ideas, and develop skills fearlessly.

For example, encourage your sales team to experiment with new methodologies, client acquisition techniques, or workflow platforms to streamline processes. Then, allow all employees to offer feedback on the changes so their voices feel heard and valued and your sales team can gain fresh perspectives.

6. Don’t hate, collaborate

Regular brainstorming sessions effectively generate a wide pool of ideas. They also establish a teamwork-focused company culture and encourage diverse perspectives .

No matter the brainstorming technique you choose, discuss the session’s focus and agenda beforehand so everyone feels prepared and well-informed. The right balance of freedom to pursue curiosities and structure to fine-tune ideas will help keep experiments firmly planted on the ground.

7. Learn with A/B testing

You’ll likely identify multiple solutions to the same problem, so use A/B testing to narrow down the best choice. Test every iteration of an idea on the same users to choose the best solution to improve and launch.

Before conducting these tests, identify key metrics so everyone on your team understands what success looks like for each solution. When testing ideas for improving an app’s interface, a metric might be the number of call-to-action buttons clicked.

8. Resist the temptation to micromanage

If you tend to micromanage , you might need to adopt a new leadership model . Micromanagement can make employees feel their ideas and contributions aren’t valuable, so they’ll stop sharing. And experimentation might feel like a waste of time since you'll likely re-work methods or results to suit your style.

Instead, show you trust your employees’ creativity and competence by giving them the freedom to try new methods. When they bring a viable idea to the table, offer them resources to try it out even if there’s a chance it fails.

Confronting the challenges of innovation

Changing your business’s culture is a holistic process that touches every aspect of the organization, lik e leadership style , re source allotment, and keeping up morale in the face of failures. Here are a few challenges to encouraging experimentation:

- Resistance to change: Whether you’re a large-scale organization or startup, the leadership team might not want to change “business as usual,” so prepare to show them the benefits of experimentation with data and testimony.

- To launch or not to launch: It won’t always be easy to decide whether the test results are enough to launch a new strategy that implicates the whole company. Your research might not be meticulous enough and the test market could skew results. Or maybe the new strategy unexpectedly takes precious resources from other initiatives.

- Pulling the plug: Humans often make decisions based on emotions . You may find it hard pulling the plug on experiments that teams are excited about, even when data-driven research suggests something won’t succeed in the market.

- Drained resources: Experimentation requires time and resources, as does helping your team learn from failures. But building cross-functional teams, recording tests on open-access documents, and setting time aside to analyze mistakes can help keep time and resources in check.

Embracing experimentation in the workplace is all about becoming comfortable with discomfort. It’s scary conducting new experiments to test solutions that might not work.

But nobody makes it on the first try — you can only reach success through a series of failures. So really, they’re not failures since they gave you the confidence and insights necessary to move forward.

To encourage your team to be more experimental, start by assessing your current company culture. Note areas where you tend to go with the most obvious solutions or where you’re in a bit of a rut. You might find you’re micromanaging every project, so employees don’t feel they have the freedom to try new things.

Or perhaps you haven’t found a streamlined A/B testing process yet. Once you’ve pinpointed your weak areas, work with the entire team to fix them one-by-one until you’ve successfully created an experimentation culture.

Understand Yourself Better:

Big 5 Personality Test

Madeline Miles

Madeline is a writer, communicator, and storyteller who is passionate about using words to help drive positive change. She holds a bachelor's in English Creative Writing and Communication Studies and lives in Denver, Colorado. In her spare time, she's usually somewhere outside (preferably in the mountains) — and enjoys poetry and fiction.

How experiential learning encourages employees to own their learning

What’s convergent thinking how to be a better problem-solver, celebrating art, allyship, and authors for black history month, betterup named a 2019 “cool vendor” in human capital management: enhancing employee experience by gartnerup your game: a new model for leadership, 9 must-haves for a stellar candidate experience, what is a disc assessment and how can it help your team, 18 excellent educational podcasts to fuel your love of learning, how to create a culture of accountability in the workplace, gpa on a resume: when and how to include it, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, discover 4 types of innovation and how to encourage them, how tacit knowledge drives innovation and team outcomes, learn what disruptive innovation is and how to foster it, fundamental attribution error: how to recognize your bias, why creativity isn't just for creatives and how to find it anywhere, 37 innovation and creativity appraisal comments, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Personal Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

The 7-day, science-backed experiment that can spark a culture of kindness

Cultivating kindness at work boosts productivity, motivation, and even retention, according to recent research. Use these simple strategies to inject some good vibes into your team interactions.

As one of the first lessons you learned in life, being kind to others may be something you take for granted. But research shows that kindness has tangible value across many aspects of life–and that value includes business value.

“There is now a plethora of data showing that when individuals engage in generous and altruistic behavior, they actually activate circuits in the brain that are key to fostering well-being,” explains Richard Davidson , author and founder of the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin.

When those positive feelings carry over to the workplace, things get even more interesting. A study reported on by KindCanada.org, found that employees who experienced frequent doses of kindness of work had:

- 26% more energy

- 36% more job satisfaction

- 44% greater commitment to their organization

- 30% greater motivation to learn new skills and ideas

The science behind kindness

When you’re kind to someone—even to yourself —your brain releases serotonin and dopamine. These are feel-good neurotransmitters , causing your brain to light up with satisfaction, pleasure, reward, and well-being.

Those reward signals are so powerful that they can trigger a chain reaction in interactions with other people. One study found that employees who were treated kindly were 278% more generous to coworkers compared to a control group. So if you’re thanked for a job well done, then you’re more likely to pay it forward by complimenting someone else.

The 7 days of kindness experiment

Oxford University and Kindness.org ran a study to quantify the value of kindness. They found that just seven days of small, random acts of kindness were enough to bring significantly more joy to the study participants’ lives. And the more acts of kindness people were exposed to, the greater the benefits.

Seven days of small, random acts of kindness bring serious changes to your life (and work life).

It just takes one person on your team to set the tone and model kind behavior for everyone. Once you’ve set that baseline, you can work together as a group to weave kindness into your meetings, daily work life, and workplace culture.

Challenge your teammates to commit to seven days of practicing random acts of kindness and see how it impacts productivity and morale.

Create a culture of kindness

Starting with seven days of random acts of kindness can be the first step toward creating a culture of kindness. To go even further:

- Get inspired by even more ideas for random acts of kindness from the Random Acts of Kindness organization

- Assign and rotate weekly kindness leaders on your team

- Challenge yourself and your team to keep up the kindness at work and at home

- Dedicate a few minutes of team meetings to kindness (give kudos, treats, and progress updates)

- Start every one-on-one meeting by complimenting the other person on something that went well

- Have team members write down each daily act of kindness they did in a Trello note and make a Trello Board that showcases kindness in the office

- Show your appreciation to others through kudos, celebrations, gifts, and acknowledgement

- Inspire other teams and departments to do the same

- Write kindness into your company policies and philosophy

Thinking bigger than small, random acts of kindness

Entrepreneur James Rhee gave a powerful TED talk on the value of kindness at work , in which he shared how kindness became such an important part of his organization’s culture and business philosophy.

Inspired from the top down, goodwill and kindness connected his company leaders, employees, and customers. Kindness set the tone for their branding, customer service, sales, marketing, and internal communications. Everything. It was infectious and even saved the company from bankruptcy.

“We had the courage to establish a culture of kindness in the workplace,” Rhee said. “It was a strategic priority day in and day out—and yeah, there were moments as individuals we failed. But as a collective, we were very successful in changing attitudes about the transformative power of kindness at work.”

Make it your philosophy to be kind at work and in life. Be kind to yourself and to others. Start with just seven days of small, random acts of kindness and see if it inspires you and others to do the same.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Ideas for Psychology Experiments

Inspiration for psychology experiments is all around if you know where to look

Psychology experiments can run the gamut from simple to complex. Students are often expected to design—and sometimes perform—their own experiments, but finding great experiment ideas can be a little challenging. Fortunately, inspiration is all around if you know where to look—from your textbooks to the questions that you have about your own life.

Always discuss your idea with your instructor before beginning your experiment—particularly if your research involves human participants. (Note: You'll probably need to submit a proposal and get approval from your school's institutional review board.)

At a Glance

If you are looking for an idea for psychology experiments, start your search early and make sure you have the time you need. Doing background research, choosing an experimental design, and actually performing your experiment can be quite the process. Keep reading to find some great psychology experiment ideas that can serve as inspiration. You can then find ways to adapt these ideas for your own assignments.

15 Ideas for Psychology Experiments

Most of these experiments can be performed easily at home or at school. That said, you will need to find out if you have to get approval from your teacher or from an institutional review board before getting started.

The following are some questions you could attempt to answer as part of a psychological experiment:

- Are people really able to "feel like someone is watching" them ? Have some participants sit alone in a room and have them note when they feel as if they are being watched. Then, see how those results line up to your own record of when participants were actually being observed.

- Can certain colors improve learning ? You may have heard teachers or students claim that printing text on green paper helps students read better, or that yellow paper helps students perform better on math exams. Design an experiment to see whether using a specific color of paper helps improve students' scores on math exams.

- Can color cause physiological reactions ? Perform an experiment to determine whether certain colors cause a participant's blood pressure to rise or fall.

- Can different types of music lead to different physiological responses ? Measure the heart rates of participants in response to various types of music to see if there is a difference.

- Can smelling one thing while tasting another impact a person's ability to detect what the food really is ? Have participants engage in a blind taste test where the smell and the food they eat are mismatched. Ask the participants to identify the food they are trying and note how accurate their guesses are.

- Could a person's taste in music offer hints about their personality ? Previous research has suggested that people who prefer certain styles of music tend to exhibit similar personality traits. Administer a personality assessment and survey participants about their musical preferences and examine your results.

- Do action films cause people to eat more popcorn and candy during a movie ? Have one group of participants watch an action movie, and another group watch a slow-paced drama. Compare how much popcorn is consumed by each group.