An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Mental Health Evaluation for Gender Confirmation Surgery

Affiliation.

- 1 New Health Foundation Worldwide, 1214 Lake Street, Evanston, IL 60201, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 29908617

- DOI: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.002

The requests for medically necessary surgical interventions for transgender individuals have steadily increased over the past several years. So too has the recognition of the diverse nature of this population. The surgeon relies heavily on the mental health provider to assess the readiness and eligibility of the patient to undergo surgery, which the mental health provider documents in a referral letter to the surgeon. The mental health provider explores the individual's preparedness for surgery, expectations, and surgical goals and communicates with the surgeon and other providers to promote positive outcomes and inform multidisciplinary care.

Keywords: Gender; Gender dysphoria; Gender-affirming; Mental health; Surgery.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons. Wesp LM, Deutsch MB. Wesp LM, et al. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017 Mar;40(1):99-111. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. Epub 2016 Dec 22. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017. PMID: 28159148 Review.

- Healthcare costs and quality of life outcomes following gender affirming surgery in trans men: a review. Defreyne J, Motmans J, T'sjoen G. Defreyne J, et al. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017 Dec;17(6):543-556. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2017.1388164. Epub 2017 Oct 9. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017. PMID: 28972413 Review.

- Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Men (Female-to-Male). Gorton RN, Erickson-Schroth L. Gorton RN, et al. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017 Mar;40(1):79-97. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.005. Epub 2016 Dec 12. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017. PMID: 28159147 Review.

- Gender-affirming hormones and surgery in transgender children and adolescents. Mahfouda S, Moore JK, Siafarikas A, Hewitt T, Ganti U, Lin A, Zepf FD. Mahfouda S, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Jun;7(6):484-498. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30305-X. Epub 2018 Dec 6. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019. PMID: 30528161 Review.

- WHOQOL-100 Before and After Sex Reassignment Surgery in Brazilian Male-to-Female Transsexual Individuals. Cardoso da Silva D, Schwarz K, Fontanari AM, Costa AB, Massuda R, Henriques AA, Salvador J, Silveira E, Elias Rosito T, Lobato MI. Cardoso da Silva D, et al. J Sex Med. 2016 Jun;13(6):988-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.370. Epub 2016 Apr 21. J Sex Med. 2016. PMID: 27117529

- Qualitative Assessment of the Experiences of Transgender Individuals Assigned Female at Birth Undergoing Gender-Affirming Mastectomy for the Treatment of Gender Dysphoria. Christiano JG, Punekar I, Patel A, McGregor HA, Moskow M, Anson E. Christiano JG, et al. Transgend Health. 2024 Apr 3;9(2):143-150. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2022.0056. eCollection 2024 Apr. Transgend Health. 2024. PMID: 38585246

- Readiness assessments for gender-affirming surgical treatments: A systematic scoping review of historical practices and changing ethical considerations. Amengual T, Kunstman K, Lloyd RB, Janssen A, Wescott AB. Amengual T, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Oct 20;13:1006024. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1006024. eCollection 2022. Front Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 36339880 Free PMC article.

- Correlations between healthcare provider interactions and mental health among transgender and nonbinary adults. Kattari SK, Bakko M, Hecht HK, Kattari L. Kattari SK, et al. SSM Popul Health. 2019 Nov 29;10:100525. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100525. eCollection 2020 Apr. SSM Popul Health. 2019. PMID: 31872041 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

- W.B. Saunders

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Preparing for Gender Affirmation Surgery: Ask the Experts

Preparing for your gender affirmation surgery can be daunting. To help provide some guidance for those considering gender affirmation procedures, our team from the Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health (JHCTGEH) answered some questions about what to expect before and after your surgery.

What kind of care should I expect as a transgender individual?

What kind of care should I expect as a transgender individual? Before beginning the process, we recommend reading the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards Of Care (SOC). The standards were created by international agreement among health care clinicians and in collaboration with the transgender community. These SOC integrate the latest scientific research on transgender health, as well as the lived experience of the transgender community members. This collaboration is crucial so that doctors can best meet the unique health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse people. It is usually a favorable sign if the hospital you choose for your gender affirmation surgery follows or references these standards in their transgender care practices.

Can I still have children after gender affirmation surgery?

Many transgender individuals choose to undergo fertility preservation before their gender affirmation surgery if having biological children is part of their long-term goals. Discuss all your options, such as sperm banking and egg freezing, with your doctor so that you can create the best plan for future family building. JHCTGEH has fertility specialists on staff to meet with you and develop a plan that meets your goals.

Are there other ways I need to prepare?

It is very important to prepare mentally for your surgery. If you haven’t already done so, talk to people who have undergone gender affirmation surgeries or read first-hand accounts. These conversations and articles may be helpful; however, keep in mind that not everything you read will apply to your situation. If you have questions about whether something applies to your individual care, it is always best to talk to your doctor.

You will also want to think about your recovery plan post-surgery. Do you have friends or family who can help care for you in the days after your surgery? Having a support system is vital to your continued health both right after surgery and long term. Most centers have specific discharge instructions that you will receive after surgery. Ask if you can receive a copy of these instructions in advance so you can familiarize yourself with the information.

An initial intake interview via phone with a clinical specialist.

This is your first point of contact with the clinical team, where you will review your medical history, discuss which procedures you’d like to learn more about, clarify what is required by your insurance company for surgery, and develop a plan for next steps. It will make your phone call more productive if you have these documents ready to discuss with the clinician:

- Medications. Information about which prescriptions and over-the-counter medications you are currently taking.

- Insurance. Call your insurance company and find out if your surgery is a “covered benefit" and what their requirements are for you to have surgery.

- Medical Documents. Have at hand the name, address, and contact information for any clinician you see on a regular basis. This includes your primary care clinician, therapists or psychiatrists, and other health specialist you interact with such as a cardiologist or neurologist.

After the intake interview you will need to submit the following documents:

- Pharmacy records and medical records documenting your hormone therapy, if applicable

- Medical records from your primary physician.

- Surgical readiness referral letters from mental health providers documenting their assessment and evaluation

An appointment with your surgeon.

After your intake, and once you have all of your required documentation submitted you will be scheduled for a surgical consultation. These are in-person visits where you will get to meet the surgeon. typically include: The specialty nurse and social worker will meet with you first to conduct an assessment of your medical health status and readiness for major surgical procedures. Discussion of your long-term gender affirmation goals and assessment of which procedures may be most appropriate to help you in your journey. Specific details about the procedures you and your surgeon identify, including the risks, benefits and what to expect after surgery.

A preoperative anesthesia and medical evaluation.

Two to four weeks before your surgery, you may be asked to complete these evaluations at the hospital, which ensure that you are healthy enough for surgery.

What can I expect after gender affirming surgery?

When you’ve finished the surgical aspects of your gender affirmation, we encourage you to follow up with your primary care physician to make sure that they have the latest information about your health. Your doctor can create a custom plan for long-term care that best fits your needs. Depending on your specific surgery and which organs you continue to have, you may need to follow up with a urologist or gynecologist for routine cancer screening. JHCTGEH has primary care clinicians as well as an OB/GYN and urologists on staff.

Among other changes, you may consider updating your name and identification. This list of resources for transgender and gender diverse individuals can help you in this process.

The Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health Team at Johns Hopkins

Embracing diversity and inclusion, the Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health provides affirming, objective, person-centered care to improve health and enhance wellness; educates interdisciplinary health care professionals to provide culturally competent, evidence-based care; informs the public on transgender health issues; and advances medical knowledge by conducting biomedical research.

Find a Doctor

Specializing In:

- Gender Affirmation Surgery

- Transgender Health

Find a Treatment Center

- Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health

Find Additional Treatment Centers at:

- Howard County Medical Center

- Sibley Memorial Hospital

- Suburban Hospital

Request an Appointment

Gender Affirmation Surgeries

Facial Masculinization Surgery

Facial Feminization Surgery (FFS)

Related Topics

- LGBTQ Health

- Gender Affirmation

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Preparation and Procedures Involved in Gender Affirmation Surgeries

If you or a loved one are considering gender affirmation surgery , you are probably wondering what steps you must go through before the surgery can be done. Let's look at what is required to be a candidate for these surgeries, the potential positive effects and side effects of hormonal therapy, and the types of surgeries that are available.

Gender affirmation surgery, also known as gender confirmation surgery, is performed to align or transition individuals with gender dysphoria to their true gender.

A transgender woman, man, or non-binary person may choose to undergo gender affirmation surgery.

The term "transexual" was previously used by the medical community to describe people who undergo gender affirmation surgery. The term is no longer accepted by many members of the trans community as it is often weaponized as a slur. While some trans people do identify as "transexual", it is best to use the term "transgender" to describe members of this community.

Transitioning

Transitioning may involve:

- Social transitioning : going by different pronouns, changing one’s style, adopting a new name, etc., to affirm one’s gender

- Medical transitioning : taking hormones and/or surgically removing or modifying genitals and reproductive organs

Transgender individuals do not need to undergo medical intervention to have valid identities.

Reasons for Undergoing Surgery

Many transgender people experience a marked incongruence between their gender and their assigned sex at birth. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has identified this as gender dysphoria.

Gender dysphoria is the distress some trans people feel when their appearance does not reflect their gender. Dysphoria can be the cause of poor mental health or trigger mental illness in transgender people.

For these individuals, social transitioning, hormone therapy, and gender confirmation surgery permit their outside appearance to match their true gender.

Steps Required Before Surgery

In addition to a comprehensive understanding of the procedures, hormones, and other risks involved in gender-affirming surgery, there are other steps that must be accomplished before surgery is performed. These steps are one way the medical community and insurance companies limit access to gender affirmative procedures.

Steps may include:

- Mental health evaluation : A mental health evaluation is required to look for any mental health concerns that could influence an individual’s mental state, and to assess a person’s readiness to undergo the physical and emotional stresses of the transition.

- Clear and consistent documentation of gender dysphoria

- A "real life" test : The individual must take on the role of their gender in everyday activities, both socially and professionally (known as “real-life experience” or “real-life test”).

Firstly, not all transgender experience physical body dysphoria. The “real life” test is also very dangerous to execute, as trans people have to make themselves vulnerable in public to be considered for affirmative procedures. When a trans person does not pass (easily identified as their gender), they can be clocked (found out to be transgender), putting them at risk for violence and discrimination.

Requiring trans people to conduct a “real-life” test despite the ongoing violence out transgender people face is extremely dangerous, especially because some transgender people only want surgery to lower their risk of experiencing transphobic violence.

Hormone Therapy & Transitioning

Hormone therapy involves taking progesterone, estrogen, or testosterone. An individual has to have undergone hormone therapy for a year before having gender affirmation surgery.

The purpose of hormone therapy is to change the physical appearance to reflect gender identity.

Effects of Testosterone

When a trans person begins taking testosterone , changes include both a reduction in assigned female sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned male sexual characteristics.

Bodily changes can include:

- Beard and mustache growth

- Deepening of the voice

- Enlargement of the clitoris

- Increased growth of body hair

- Increased muscle mass and strength

- Increase in the number of red blood cells

- Redistribution of fat from the breasts, hips, and thighs to the abdominal area

- Development of acne, similar to male puberty

- Baldness or localized hair loss, especially at the temples and crown of the head

- Atrophy of the uterus and ovaries, resulting in an inability to have children

Behavioral changes include:

- Aggression

- Increased sex drive

Effects of Estrogen

When a trans person begins taking estrogen , changes include both a reduction in assigned male sexual characteristics and an increase in assigned female characteristics.

Changes to the body can include:

- Breast development

- Loss of erection

- Shrinkage of testicles

- Decreased acne

- Decreased facial and body hair

- Decreased muscle mass and strength

- Softer and smoother skin

- Slowing of balding

- Redistribution of fat from abdomen to the hips, thighs, and buttocks

- Decreased sex drive

- Mood swings

When Are the Hormonal Therapy Effects Noticed?

The feminizing effects of estrogen and the masculinizing effects of testosterone may appear after the first couple of doses, although it may be several years before a person is satisfied with their transition. This is especially true for breast development.

Timeline of Surgical Process

Surgery is delayed until at least one year after the start of hormone therapy and at least two years after a mental health evaluation. Once the surgical procedures begin, the amount of time until completion is variable depending on the number of procedures desired, recovery time, and more.

Transfeminine Surgeries

Transfeminine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people who were assigned male at birth.

Most often, surgeries involved in gender affirmation surgery are broken down into those that occur above the belt (top surgery) and those below the belt (bottom surgery). Not everyone undergoes all of these surgeries, but procedures that may be considered for transfeminine individuals are listed below.

Top surgery includes:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization

- Nose surgery: Rhinoplasty may be done to narrow the nose and refine the tip.

- Eyebrows: A brow lift may be done to feminize the curvature and position of the eyebrows.

- Jaw surgery: The jaw bone may be shaved down.

- Chin reduction: Chin reduction may be performed to soften the chin's angles.

- Cheekbones: Cheekbones may be enhanced, often via collagen injections as well as other plastic surgery techniques.

- Lips: A lip lift may be done.

- Alteration to hairline

- Male pattern hair removal

- Reduction of Adam’s apple

- Voice change surgery

Bottom surgery includes:

- Removal of the penis (penectomy) and scrotum (orchiectomy)

- Creation of a vagina and labia

Transmasculine Surgeries

Transmasculine is an umbrella term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people who were assigned female at birth.

Surgery for this group involves top surgery and bottom surgery as well.

Top surgery includes :

- Subcutaneous mastectomy/breast reduction surgery.

- Removal of the uterus and ovaries

- Creation of a penis and scrotum either through metoidioplasty and/or phalloplasty

Complications and Side Effects

Surgery is not without potential risks and complications. Estrogen therapy has been associated with an elevated risk of blood clots ( deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli ) for transfeminine people. There is also the potential of increased risk of breast cancer (even without hormones, breast cancer may develop).

Testosterone use in transmasculine people has been associated with an increase in blood pressure, insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities, though it's not certain exactly what role these changes play in the development of heart disease.

With surgery, there are surgical risks such as bleeding and infection, as well as side effects of anesthesia . Those who are considering these treatments should have a careful discussion with their doctor about potential risks related to hormone therapy as well as the surgeries.

Cost of Gender Confirmation Surgery

Surgery can be prohibitively expensive for many transgender individuals. Costs including counseling, hormones, electrolysis, and operations can amount to well over $100,000. Transfeminine procedures tend to be more expensive than transmasculine ones. Health insurance sometimes covers a portion of the expenses.

Quality of Life After Surgery

Quality of life appears to improve after gender-affirming surgery for all trans people who medically transition. One 2017 study found that surgical satisfaction ranged from 94% to 100%.

Since there are many steps and sometimes uncomfortable surgeries involved, this number supports the benefits of surgery for those who feel it is their best choice.

A Word From Verywell

Gender affirmation surgery is a lengthy process that begins with counseling and a mental health evaluation to determine if a person can be diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

After this is complete, hormonal treatment is begun with testosterone for transmasculine individuals and estrogen for transfeminine people. Some of the physical and behavioral changes associated with hormonal treatment are listed above.

After hormone therapy has been continued for at least one year, a number of surgical procedures may be considered. These are broken down into "top" procedures and "bottom" procedures.

Surgery is costly, but precise estimates are difficult due to many variables. Finding a surgeon who focuses solely on gender confirmation surgery and has performed many of these procedures is a plus. Speaking to a surgeon's past patients can be a helpful way to gain insight on the physician's practices as well.

For those who follow through with these preparation steps, hormone treatment, and surgeries, studies show quality of life appears to improve. Many people who undergo these procedures express satisfaction with their results.

Bizic MR, Jeftovic M, Pusica S, et al. Gender dysphoria: Bioethical aspects of medical treatment . Biomed Res Int . 2018;2018:9652305. doi:10.1155/2018/9652305

American Psychiatric Association. What is gender dysphoria? . 2016.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people . 2012.

Tomlins L. Prescribing for transgender patients . Aust Prescr . 2019;42(1): 10–13. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2019.003

T'sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of transgender medicine . Endocr Rev . 2019;40(1):97-117. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00011

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877-884. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Seal LJ. A review of the physical and metabolic effects of cross-sex hormonal therapy in the treatment of gender dysphoria . Ann Clin Biochem . 2016;53(Pt 1):10-20. doi:10.1177/0004563215587763

Schechter LS. Gender confirmation surgery: An update for the primary care provider . Transgend Health . 2016;1(1):32-40. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0006

Altman K. Facial feminization surgery: current state of the art . Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2012;41(8):885-94. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2012.04.024

Therattil PJ, Hazim NY, Cohen WA, Keith JD. Esthetic reduction of the thyroid cartilage: A systematic review of chondrolaryngoplasty . JPRAS Open. 2019;22:27-32. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.07.002

Top H, Balta S. Transsexual mastectomy: Selection of appropriate technique according to breast characteristics . Balkan Med J . 2017;34(2):147-155. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.0093

Chan W, Drummond A, Kelly M. Deep vein thrombosis in a transgender woman . CMAJ . 2017;189(13):E502-E504. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160408

Streed CG, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: A narrative review . Ann Intern Med . 2017;167(4):256-267. doi:10.7326/M17-0577

Hashemi L, Weinreb J, Weimer AK, Weiss RL. Transgender care in the primary care setting: A review of guidelines and literature . Fed Pract . 2018;35(7):30-37.

Van de grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming aurgery: A follow-up atudy . J Sex Marital Ther . 2018;44(2):138-148. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender confirmation surgeries .

American Psychological Association. Transgender people, gender identity, and gender expression .

Colebunders B, Brondeel S, D'Arpa S, Hoebeke P, Monstrey S. An update on the surgical treatment for transgender patients . Sex Med Rev . 2017 Jan;5(1):103-109. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.08.001

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > European Psychiatry

- > Volume 30 Issue S1: Abstracts of the 23rd European...

- > Psychiatric Assessment of Transgender Adults for Sex...

Article contents

Psychiatric assessment of transgender adults for sex reassignment surgery.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 April 2020

While pre-surgical assessments by an internist are relatively common, those by psychiatrists are much more rare. With the exception of bariatric surgery and live donor organ transplantation, sex reassignment surgery (SRS) is the only category of surgeries for which a mental health assessment is routinely done as part of the standard of care. This presentation will outline the assessment process as performed at the Gender Identity Clinic at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, which sees and approves individuals in the Canadian province of Ontario seeking to have sex reassignment surgery through the provincial health care insurance plan.

There are three main tasks of the assessment, diagnosis / differential diagnosis, eligibility assessment, and readiness assessment. Diagnosis, while controversial among some in the transgender community, is generally required by most medical professionals and insurance plans that might cover surgical transition procedures. In Ontario diagnosis is a regulated professional activity and can only be done formally by physicians and clinical psychologists.

Eligibility relates to certain specific requirements broadly applied to those seeking surgery that are outlined in international standards of care. For genital surgery, this includes one year of living a full time, continuous gender role experience (GRE) in the chosen gender role.

Readiness is the part of the assessment that most resembles a general psychiatric assessment, in which a full biopsychosocial formulation of the client's current status leads to recommendations for improving readiness for SRS.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 30, Issue S1

- C. McIntosh (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(15)30128-0

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Gender Affirmative Surgery Psychological Evaluations

If you or a loved one are in the process of transitioning or are looking to have a gender affirmative surgery, we want to help .

Deep Eddy Psychotherapy offers psychological evaluations for gender affirmative surgery candidacy for our clients (ages 18 and up). Our clinicians are dedicated to helping the transgender, non-binary, genderqueer, and gender-expansive community by providing this evaluation service along with individual, group, and couples therapy .

We also recognize that transphobia and transmisogyny are interwoven into our society and that the mental health profession has had an unfortunate history of perpetuating these ideas. Our therapists are committed to being part of the change for good and live more fully within our values – you deserve nothing less.

Ready to sign up to get an evaluation? Don’t wait – contact us today. Please read on to learn more about gender affirmative surgery evaluations and answers to common questions.

What is a gender affirmative surgery evaluation?

Under the current guidelines, transgender, non-binary, and gender non-conforming clients seeking gender affirmative surgeries must have letters from mental health providers attesting to whether they meet the guidelines for surgical intervention established by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH).

Anyone who is seeking an attestation letter must meet with a mental health provider for an evaluation (typically just an interview, but occasionally more than one session) to determine whether they are good candidates for surgery. Based on the results of the evaluation, the provider will write a letter summarizing your candidacy and their recommendations.

Do you need an evaluation for hormone replacement treatment (HRT)?

No. In Texas (and in most other states), we now use an informed consent model in place for HRT. So, you no longer need letters from mental health providers in order to receive HRT.

What does a gender affirmative surgery evaluation assess for?

At Deep Eddy Psychotherapy, our clinicians recognize the inherent gatekeeping role that mental health providers have in this compulsory letter-writing process, and we seek to reduce any undue gatekeeping while also having to work within the structure of the WPATH Standards of Care.

Our clinicians who provide this service have a welcoming and affirmative stance toward gender-diverse clients and want to help clients receive the gender-affirming medical care they seek. We have training and experience in this area, and we actively consult with each other about the process.

We say all of this so that you can rest easier knowing that our process is designed with your rights in mind. Our goal is not to keep you from getting the surgery you need, but rather to ensure that you are the right fit and have the support you need to succeed.

Some of the things your evaluator might ask about might include:

- Your gender story

- Past and current emotional wellbeing

- Social supports you can lean on

- What sorts of surgical interventions you are seeking

- Your understanding of the risks and benefits of surgery

Our providers understand that there is no one gender story narrative. Your story is unique and does not have to be tied together with a sense of certainty. Likewise, our providers understand that your past and current emotional wellbeing could be impacted by both gender dysphoria and the effects of living in a cisnormative society, and we want to give you the support you deserve.

In addition to us asking you questions, we also welcome questions from the interviewee. We recognize how hard it is to get to this point, and we want to be here for you however we can.

Who can write an attestation letter?

In Texas, some insurance companies require all letters to be written by doctoral level (PhD or PsyD) clinicians. Some insurance companies and surgery centers allow master’s level clinicians (LMFT, LCSW, LPC) to provide letters, but not all will. To make matters a bit more complicated, some insurances and some procedures may require multiple letters from different providers.

Before scheduling a session, it can be helpful to talk with your insurance company and/or surgery center about what they each require in the letter and who can write the letters.

If you do not have insurance, as advocates for equity and social justice, we do not want the ability to pay to keep you from receiving a letter from a mental health professional. Please feel free to reach out to us if you have financial need, and we can let you know which clinicians have sliding scale spots open for this service at the time.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 12 April 2011

Gender reassignment surgery: an overview

- Gennaro Selvaggi 1 &

- James Bellringer 1

Nature Reviews Urology volume 8 , pages 274–282 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

4016 Accesses

153 Citations

41 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Pathogenesis

- Reconstruction

- Urogenital diseases

This article has been updated

Gender reassignment (which includes psychotherapy, hormonal therapy and surgery) has been demonstrated as the most effective treatment for patients affected by gender dysphoria (or gender identity disorder), in which patients do not recognize their gender (sexual identity) as matching their genetic and sexual characteristics. Gender reassignment surgery is a series of complex surgical procedures (genital and nongenital) performed for the treatment of gender dysphoria. Genital procedures performed for gender dysphoria, such as vaginoplasty, clitorolabioplasty, penectomy and orchidectomy in male-to-female transsexuals, and penile and scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals, are the core procedures in gender reassignment surgery. Nongenital procedures, such as breast enlargement, mastectomy, facial feminization surgery, voice surgery, and other masculinization and feminization procedures complete the surgical treatment available. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health currently publishes and reviews guidelines and standards of care for patients affected by gender dysphoria, such as eligibility criteria for surgery. This article presents an overview of the genital and nongenital procedures available for both male-to-female and female-to-male gender reassignment.

The management of gender dysphoria consists of a combination of psychotherapy, hormonal therapy, and surgery

Psychiatric evaluation is essential before gender reassignment surgical procedures are undertaken

Gender reassignment surgery refers to the whole genital, facial and body procedures required to create a feminine or a masculine appearance

Sex reassignment surgery refers to genital procedures, namely vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty, labioplasty, and penile–scrotal reconstruction

In male-to-female gender dysphoria, skin tubes formed from penile or scrotal skin are the standard technique for vaginal construction

In female-to-male gender dysphoria, no technique is recognized as the standard for penile reconstruction; different techniques fulfill patients' requests at different levels, with a variable number of surgical technique-related drawbacks

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Principles and outcomes of gender-affirming vaginoplasty

Sexual function of transgender assigned female at birth seeking gender affirming care: a narrative review

The effect of early puberty suppression on treatment options and outcomes in transgender patients

Change history, 26 april 2011.

In the version of this article initially published online, the statement regarding the frequency of male-to-female transsexuals was incorrect. The error has been corrected for the print, HTML and PDF versions of the article.

Meyer, W. 3rd. et al . The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association's standards of care for gender identity disorders, sixth version. World Professional Association for Transgender Health [online] , (2001).

Google Scholar

Bakker, A., Van Kesteren, P., Gooren, L. & Bezemer, P. The prevalence of transsexualism in The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 87 , 237–238 (1993).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Selvaggi, G. et al . Gender identity disorder: general overview and surgical treatment for vaginoplasty in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 116 , 135e–145e (2005).

Article Google Scholar

Benjamin, H. (ed.) The Transsexual Phenomenon (Julian Press Inc., New York, 1966).

World Professional Association for Transgender Health [online] , (2010).

Zhou, J. N., Hofman, M. A., Gooren, L. J. & Swaab, D. F. A sex difference in the human brain and its relation to transsexuality. Nature 378 , 68–70 (1995).

Kruijver, F. P. et al . Male-to-female transsexuals have female neuron numbers in a limbic nucleus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 , 2034–2041 (2000).

Swaab, D. F., Chun, W. C., Kruijver, F. P., Hofman, M. A. & Ishuina, T. A. Sexual differentiation of the human hypothalamus. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 511 , 75–105 (2002).

Garcia-Falgueras, A. & Swaab, D. F. A sex difference in the hypothalamic uncinate nucleus: relationship to gender identity. Brain 131 , 3115–3117 (2008).

Cohen-Kettenis, P. & Kuiper, B. Transseksualiteit en psychotherapie [Dutch]. Tijdschr. Psychoth. 3 , 153–166 (1984).

Kuiper, B. & Cohen-Kettenis, P. Sex reassignment surgery: a study of 141 Dutch transsexuals. Arch. Sex. Behav. 17 , 439–457 (1988).

Kanhai, R. C., Hage, J. J., Karim, R. B. & Mulder, J. W. Exceptional presenting conditions and outcome of augmentation mammoplasty in male-to female transsexuals. Ann. Plast. Surg. 43 , 476–483 (1999).

Kanagalingm, J. et al . Cricothyroid approximation and subluxation in 21 male-to-female transsexuals. Laryngoscope 115 , 611–618 (2005).

Bouman, M. Laparoscopic assisted colovaginoplasty. Presented at the 2009 biennial World Professional Association for Transgender Health meeting, Oslo.

Rubin, S. O. Sex-reassignment surgery male-to-female. Review, own results and report of a new technique using the glans penis as a pseudoclitoris. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 154 , 1–28 (1993).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fang, R. H., Chen, C. F. & Ma, S. A new method for clitoroplasty in male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 89 , 679–682 (1992).

Selvaggi, G. et al . Genital sensitivity in sex reassignment surgery. Ann. Plast. Surg. 58 , 427–433 (2007).

Watanayusakul, S. SRS procedures. The Suporn Clinic [online] , (2010).

Melzer, T. Managing complications of male to female surgery. Presented at the 2007 World Professional Association for Transgender Health biennial meeting, Chicago.

Gilleard, O., Qureshi, M., Thomas, P. & Bellringer, J. Urethral bleeding following male to female gender reassignmetn surgery. Presented at the 2009 World Professional Association for Transgender Health biennial meeting, Oslo.

Beckley, I., Thomas, P. & Bellringer, J. Aetiology and management of recto-vaginal fistulas following male to female gender reassignment. Presented at 2008 EAU section of genitourinary surgeons and the EAU section of andrological urology meeting, Madrid.

Monstrey, S. et al . Chest wall contouring surgery in female-to-male (FTM) transsexuals: a new algorithm. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 121 , 849–859 (2008).

Mueller, A. & Gooren, L. Hormone-related tumors in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 159 , 197–202 (2008).

Selvaggi, G., Elander, A. & Branemark, R. Penile epithesis: preliminary study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 126 , 265e–266e (2010).

Selvaggi, G. & Elander, A. Penile reconstruction/formation. Curr. Opin. Urol. 18 , 589–597 (2008).

Gilbert, D. A., Jordan, G. H., Devine, C. J. Jr & Winslow, B. H. Microsurgical forearm “cricket bat-transformer” phalloplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 90 , 711–716 (1992).

Bettocchi, C., Ralph, D. J. & Pryor, J. P. Pedicled pubic phalloplasty in females with gender dysphoria. BJU Int. 95 , 120–124 (2005).

Monstrey, S. et al . Penile reconstruction: is the radial forearm flap really the standard technique? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124 , 510–518 (2009).

Selvaggi, G. et al . Donor-site morbidity of the radial forearm free flap after 125 phalloplasties in gender identity disorder. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 118 , 1171–1177 (2006).

Hoebeke, P. et al . Impact of sex reassignment surgery on lower urinary tract function. Eur. Urol. 47 , 398–402 (2005).

Agrawal, V. & Ralph, D. An audit of implanted penile prosteses in the UK. BJU Int. 98 , 393–395 (2006).

Hoebeke, P. B. et al . Erectile implants in female-to-male transsexuals: our experience in 129 patients. Eur. Urol. 57 , 334–340 (2010).

Vesely, J. et al . New technique of total phalloplasty with reinnervated latissimus dorsi myocutaneous free flap in female-to-male transsexuals. Ann. Plast. Surg. 58 , 544–550 (2007).

Selvaggi, G. et al . Scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals: a novel scrotoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 123 , 1710–1718 (2009).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Gender Surgery Unit, Charing Cross Hospital, Imperial College NHS Trust, 179–183 Fulham Palace Road, London, W6 8QZ, UK

Gennaro Selvaggi & James Bellringer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

G. Selvaggi and J. Bellringer contributed equally to the research, discussions, writing, reviewing, and editing of this article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James Bellringer .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Selvaggi, G., Bellringer, J. Gender reassignment surgery: an overview. Nat Rev Urol 8 , 274–282 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2011.46

Download citation

Published : 12 April 2011

Issue Date : May 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2011.46

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A bibliometric and visualisation analysis on the research of female genital plastic surgery based on the web of science core collection database.

- Xianling Zhang

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2024)

Chest Feminization in Transwomen with Subfascial Breast Augmentation—Our Technique and Results

- James Roy Kanjoor

- Temoor Mohammad Khan

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2023)

Vaginoplasty in Male to Female transgenders: single center experience and a narrative review

- Luca Ongaro

- Giulio Garaffa

- Giovanni Liguori

International Journal of Impotence Research (2021)

Urethral complications after gender reassignment surgery: a systematic review

- L. R. Doumanian

Overview on metoidioplasty: variants of the technique

- Marta Bizic

- Borko Stojanovic

- Miroslav Djordjevic

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

This page has been archived and is no longer being updated regularly.

The psychological challenges of gender reassignment surgery

July/August 2007, Vol 38, No. 7

Print version: page 53

Surgery and hormonal therapy are increasingly common treatments for gender dysphoria, but the prejudice and discrimination transgender individuals face post-transition can cause significant psychological distress, says Marci Bowers, MD, a surgeon who performs gender reassignment surgery in Trinidad, Colo., and is herself transgender.

Post-change, many men and women deal with rancorous divorces, custody battles, job loss and rejection by family members, she has found. Some even commit suicide, continues Bowers, who will speak about the psychological impact of transgendersurgery at APA's 2007 Annual Convention.

"It's a wonder that anyone transitions-the penalties are so severe," she says.

Bowers wants to help dispel the myths and misperceptions surrounding transgender surgery-among them that transitioning individuals are really gay men or lesbians in denial or that they are mentally ill.

"Because dysphoria is currently listed as a psychological disorder, transgender [people] are assumed to be mentally ill," she explains. "This doesn't allow them to be treated equally, no matter how visually compelling the change is."

This stigma can have far-reaching psychological effects, Bowers says. "The transition provides great barriers to intimacy, and for a person's psychological well-being, intimacy is very important."

Psychologists can help transgender people overcome such barriers as therapists and also by researching and raising awareness about the social and economic barriers transgender people face.

--L. Meyers

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Readiness assessments for gender-affirming surgical treatments: a systematic scoping review of historical practices and changing ethical considerations.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2 The Pritzker Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3 Galter Health Science Library, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) are terms that refer to individuals whose gender identity differs from sex assigned at birth. TGD individuals may choose any variety of modifications to their gender expression including, but not limited to changing their name, clothing, or hairstyle, starting hormones, or undergoing surgery. Starting in the 1950s, surgeons and endocrinologists began treating what was then known as transsexualism with cross sex hormones and a variety of surgical procedures collectively known as sex reassignment surgery (SRS). Soon after, Harry Benjamin began work to develop standards of care that could be applied to these patients with some uniformity. These guidelines, published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), are in their 8th iteration. Through each iteration there has been a requirement that patients requesting gender-affirming hormones (GAH) or gender-affirming surgery (GAS) undergo one or more detailed evaluations by a mental health provider through which they must obtain a “letter of readiness,” placing mental health providers in the role of gatekeeper. WPATH specifies eligibility criteria for gender-affirming treatments and general guidelines for the content of letters, but does not include specific details about what must be included, leading to a lack of uniformity in how mental health providers approach performing evaluations and writing letters. This manuscript aims to review practices related to evaluations and letters of readiness for GAS in adults over time as the standards of care have evolved via a scoping review of the literature. We will place a particular emphasis on changing ethical considerations over time and the evolution of the model of care from gatekeeping to informed consent. To this end, we did an extensive review of the literature. We identified a trend across successive iterations of the guidelines in both reducing stigma against TGD individuals and shift in ethical considerations from “do no harm” to the core principle of patient autonomy. This has helped reduce barriers to care and connect more people who desire it to gender affirming care (GAC), but in these authors’ opinions does not go far enough in reducing barriers.

Introduction

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) are terms that refer to any individual whose gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth. Gender identity can be expressed through any combination of name, pronouns, hairstyle, clothing, and social role. Some TGD individuals wish to transition medically by taking gender-affirming hormones (GAH) and/or pursuing gender-affirming surgery (GAS) ( 1 ). 1 The medical community’s comfort level with TGD individuals and, consequently, their willingness to provide a broad range of gender affirming care (GAC) 2 has changed significantly over time alongside an increasing understanding of what it means to be TGD and increasing cultural acceptance of LGBTQI people.

Historically physicians have placed significant barriers in the way of TGD people accessing the care that we now know to be lifesaving. Even today, patients wishing to receive GAC must navigate a system that sometimes requires multiple mental health evaluations for procedures, that is not required of cisgender individuals.

The medical and psychiatric communities have used a variety of terms over time to refer to TGD individuals. The first and second editions of DSM described TGD individuals using terms such as transvestism (TV) and transsexualism (TS), and often conflated gender identity with sexuality, by including them alongside diagnoses such as homosexuality and paraphilias. Both the DSM and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) have continuously changed diagnostic terminology and criteria involving TGD individuals over time, from Gender Identity Disorder in DSM-IV to Gender Dysphoria in DSM-5 to Gender Incongruence in ICD-11.

In 1979, the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association 3 , renamed the World Profession Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) in 2006, was the first to publish international guidelines for providing GAC to TGD individuals. The WPATH Standards of Care (SOC) are used by many insurance companies and surgeons to determine an individual’s eligibility for GAC. Throughout each iteration, mental health providers are placed in the role of gatekeeper and tasked with conducting mental health evaluations and providing required letters of readiness for TGD individuals who request GAC ( 1 ). As part of this review, we will summarize the available literature examining the practical and ethical changes in conducting mental health readiness assessments and writing the associated letters.

While the WPATH guidelines specify eligibility criteria for GAC and a general guide for what information to include in a letter of readiness, there are no widely agreed upon standardized letter templates or semi-structured interviews, leading to a variety of practices in evaluation and letter writing for GAC ( 2 ). To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to summarize the available research to date regarding the evolution of the mental health evaluation and process of writing letters of readiness for GAS. By summarizing trends in these evaluations over time, we aim to identify best practices and help further guide mental health professionals working in this field.

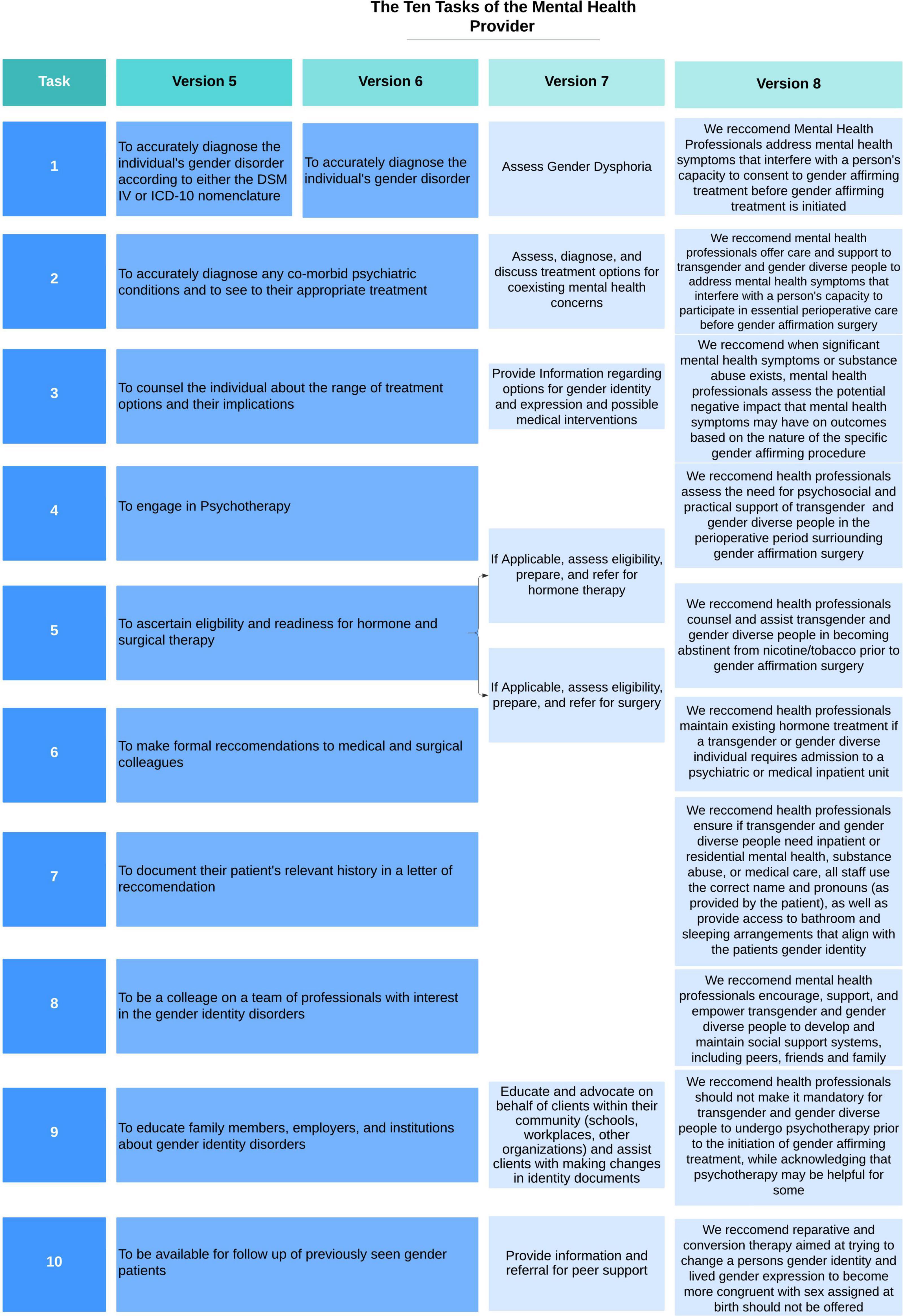

The review authors conducted a comprehensive search of the literature in collaboration with a research librarian (ABW) according to PRISMA guidelines. The search was comprised of database-specific controlled vocabulary and keyword terms for (1) mental health and (2) TGD-related surgeries. Searches were conducted on December 2, 2020 in MEDLINE (PubMed), the Cochrane Library Databases (Wiley), PsychINFO (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Scopus (Elsevier), and Dissertations and Theses Global (ProQuest). All databases were searched from inception to present without the use of limits or filters. In total, 8,197 results underwent multi-pass deduplication in a citation management system (EndNote), and 4,411 unique entries were uploaded to an online screening software (Rayyan) for title/abstract screening by two independent reviewers. In total, 303 articles were included for full text screening ( Figure 1 ), however, 69 of those articles were excluded as they were unable to be obtained online or through interlibrary loan. Both review authors conducted a full text screen of the remaining 234 articles. Articles were included in the final review if they specified criteria used for mental health screening/evaluation and/or letter writing for GAS, focused on TGD adults, were written in English, and were peer-reviewed publications. Any discrepancies were discussed between the two review authors TA and KK and a consensus was reached. A total of 86 articles met full inclusion criteria. Full documentation of all searches can be found in the Supplementary material .

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating article review process.

In total, 86 articles were included for review. Eleven articles were focused on ethical considerations while the remaining 75 articles focused on the mental health evaluation and process of writing letters of readiness for GAS. Version 8 of the SOC was published in September of 2022 during the review process of this manuscript and is also included as a reference and point of discussion.

Prior to the publication of the standards of care

Fourteen articles were identified in the literature search as published prior to the development of the WPATH SOC version 1 in 1979. Prominent themes included classification, categorization, and diagnosis of TS. Few publications described the components of a mental health evaluation, and inclusion and exclusion criteria, for GAS. Many publications focused exclusively on transgender females, with a paucity of literature examining the experiences of transgender males during this timeframe.

Authors emphasized accurate diagnosis of TS, highlighting elements of the psychosocial history including early life cross-dressing, preference for play with the opposite gender toys and friends, and social estrangement around puberty ( 3 ). One author proposed the term gender dysphoria syndrome, which included the following criteria: a sense of inappropriateness in one’s anatomically congruent sex role, that role reversal would lead to improvement in discomfort, homoerotic interest and heterosexual inhibition, an active desire for surgical intervention, and the patient taking on an active role in exploring their interest in sex reassignment ( 4 ). Many authors attempted to differentiate between the “true transsexual” and other diagnoses, including idiopathic TS; idiopathic, essential, or obligatory homosexuality; neuroticism; TV; schizophrenia; and intersex individuals ( 5 , 6 ).

Money argued that the selection criteria for patients requesting GAS include a psychiatric evaluation to obtain collateral information to confirm the accuracy of the interview, work with the family to foster support of the individual, and proper management of any psychiatric comorbidities ( 5 ). Authors began to assemble a list of possible exclusion criteria for receiving GAS such as psychosis, unstable mental health, ambivalence, and secondary gain (e.g., getting out of the military), lack of triggering major life events or crises, lack of sufficient distress in therapy, presence of marital bonds (given the illegality of same-sex marriage during this period), and if natal genitals were used for pleasure ( 3 – 5 , 7 – 13 ).

Others focused the role of the psychiatric evaluation on the social lives and roles of the patient. They believed the evaluation should include exploring the patient’s motivation for change for at least 6–12 months ( 8 ), facilitating realistic expectations of treatment, managing family issues, providing support during social transition and post-operatively ( 13 ), and encouraging GAH and the “real-life test” (RLT). The RLT is a period in which a person must fully live in their affirmed gender identity, “testing” if it is right for them. In 1970, Green recommended that a primary goal of treatment was that, “the male patient must be able to pass in society as a socially acceptable woman in appearance and to conduct the normal affairs of the day without arousing undue suspicion” ( 14 ). Benjamin also noted concern that “too masculine” features may be a contraindication to surgery so as to not make an “acceptable woman” ( 7 ). Some publications recommended at least 1–2 years of a RLT ( 3 , 7 , 11 , 15 ), while others recommended at least 5 years of RLT prior to considering GAS ( 12 ). Emphasis was placed on verifying the accuracy of reported information from family or friends to ensure “authentic” motivation for GAS and rule out ambivalence or secondary gain (e.g., getting out of the military) ( 10 ).

Ell recommended evaluation to ensure the patient has “adequate intelligence” to understand realistic expectations of surgery and attempted to highlight the patient’s autonomy in the decision to undergo GAS. He wrote, “That is your decision [to undergo surgery]. It’s up to you to prove that you are a suitable candidate for surgery. It’s not for me to offer it to you. If you decide to go ahead with your plans to pass in the opposite gender role, you do it on your own responsibility” ( 8 ). Notably, many authors conceptualized gender transition along a binary, with individuals transitioning from one end to the other.

In these earliest publications, one can start to see the beginning framework of modern-day requirements for accessing GAS, including ensuring an accurate diagnosis of gender incongruence; ruling out other possible causes of presentation such as psychosis; ensuring general mental stability; making sure that the patient has undergone at least some time of living in their affirmed gender; and that they are able to understand the consequences of the procedure.

Standards of care version 1 and 2

Changes to the standards of care.

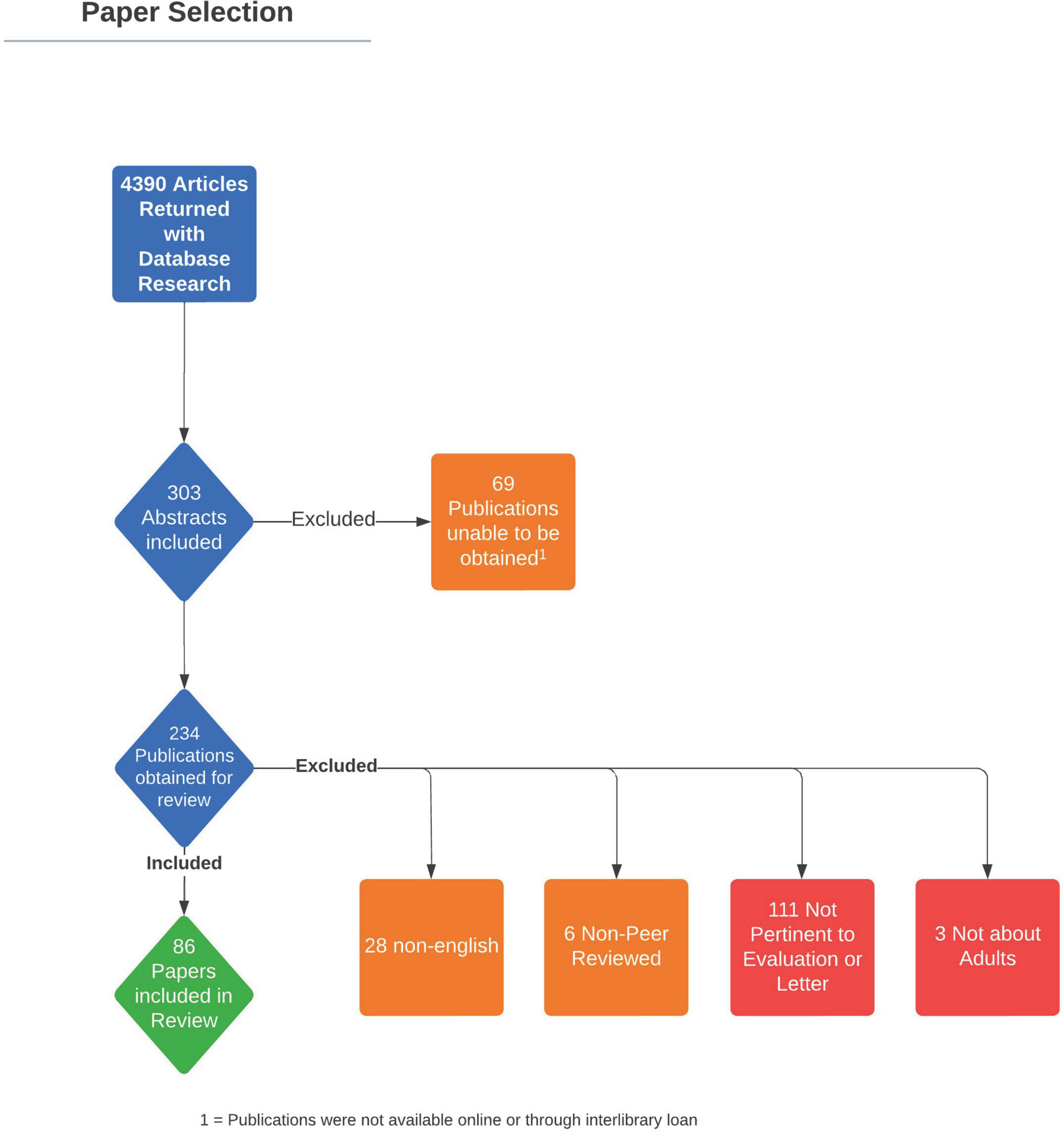

The first two versions of the WPATH SOC were written in 1979 and 1980, respectively and are substantially similar to one another. SOC version three was the first to be published in an academic journal in 1985 and changes from the first two versions were documented within this publication. The first two versions required that all recommendations for GAC be completed by licensed psychologists or psychiatrists. The first version recommended that patients requesting GAH and non-genital GAS, spend 3 and 6 months, respectively, living full time in their affirmed gender. These recommendations were rescinded in subsequent versions ( 16 ). Figure 2 reviews changes to the recommendations for GAC within the WPATH SOC over time.

Figure 2. Changes to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care around gender affirming medical and surgical treatments over time.

Results review

Five articles published between 1979 and 1980 were included in this review. Again, emphasis was placed on proper diagnosis, classification and consistency of gender identity over time ( 17 , 18 ).

Wise and Meyer explored the concept of a continuum between TV and TS, describing that those who experienced gender dysphoria often requested GAS, displayed evidence of strong cross-dressing desires with arousal, history of cross-gender roles, and absence of manic-depressive or psychotic illnesses ( 19 ). Requirements for GAS at the Johns Hopkins Gender Clinic included at least 2 years of cross-dressing, working in the opposite gender role, and undergoing treatment with GAH and psychotherapy ( 19 ). Bernstein identified factors correlated with negative GAS outcomes including presence of psychosis, drug abuse, frequent suicide attempts, criminality, unstable relationships, and low intelligence level ( 18 ). Lothstein stressed the importance of correct diagnosis, “since life stressors may lead some transvestites to clinically present as transsexuals desiring SRS” ( 20 ). Levine reviewed the diagnostic process employed by Case Western Reserve University Gender Identity Clinic which involved initial interview by a social worker to collect psychometric testing, followed by two independent psychiatric interviews to obtain the developmental gender history, understand treatment goals, and evaluate for underlying co-morbid mental health diagnoses, with a final multidisciplinary conference to integrate the various evaluations and develop a treatment plan ( 21 ).

Standards of care version 3

Version 3 broadened the definition of the clinician thereby broadening the scope of providers who could write recommendation letters for GAC. Whereas prior SOC required letters from licensed psychologists or psychiatrists, version 3 allowed initial evaluations from providers with at least a Master’s degree in behavioral science, and when required, a second evaluation from any licensed provider with at least a doctoral degree. Version 3 recommended that all evaluators demonstrate competence in “gender identity matters” and must know the patient, “in a psychotherapeutic relationship,” for at least 6 months ( 16 ). Version 3 relied on the definition of TS in DSM-III, which specified the sense of discomfort with one’s anatomic sex be “continuous (not limited to a period of stress) for at least 2 years” and be independently verified by a source other than the patient through collateral or through a longitudinal relationship with the mental health provider ( 16 ). Recommendation of GAS specifically required at least 6–12 months of RLT, for non-genital and genital GAS, respectively ( 16 ).”

Nine articles were published during the timeframe that the SOC version 3 were active (1981–1990). Themes in these publications included increasing focus on selection criteria for GAS and emphasis on the RLT, which was used to ensure proper diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Recommendations for the duration of the RLT ranged anywhere between 1 and 3 years ( 22 , 23 ).

Proposed components of the mental health evaluation for GAS included a detailed assessment of the duration, intensity, and stability of the gender dysphoria, identification of underlying psychiatric diagnoses and suicidal ideation, a mental status examination to rule out psychosis, and an assessment of intelligence (e.g., IQ) to comment on the individual’s “capacity and competence” to consent to GAC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), and Lindgren-Pauly Body Image Scale were also used during assessments ( 24 ).

Authors developed more specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for undergoing GAS with inclusion criteria including age 21 or older, not legally married, no pending litigation, evidence of gender dysphoria, completion of 1 year of psychotherapy, between 1 and 2 years RLT with ability to “pass convincingly” and “perform successfully” in the opposite gender role, at least 6 months on GAH (if medically tolerable), reasonably stable mental health (including absence of psychosis, depression, alcoholism and intellectual disability), good financial standing with psychotherapy fees ( 25 ), and a prediction that GAS would improve personal and social functioning ( 26 – 29 ). A 1987 survey of European psychiatrists identified their most common requirements as completion of a RLT of 1–2 years, psychiatric observation, mental stability, no psychosis, and 1 year of GAH ( 27 ).

Standards of care version 4

World Professional Association for Transgender Health SOC version four was published in 1990. Between version three and version four, DSM-III-R was published in 1987. Version four relied on the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for TS as opposed to the DSM-III criteria in version three. The DSM-III-R criteria for TS included a “persistent discomfort and sense of inappropriateness about one’s assigned sex,” “persistent preoccupation for at least 2 years with getting rid of one’s primary and secondary sex characteristics and acquiring the sex characteristics of the other sex,” and that the individual had reached puberty ( 30 ). Notable changes from the DSM-III criteria include specifying a time duration for the discomfort (2 years) and designating that individuals must have reached puberty.

Six articles were published between 1990 and 1998 while version four was active. Earlier trends continued including emphasizing proper diagnosis of gender dysphoria ( 31 , 32 ), however, a new trend emerged toward implementing more comprehensive evaluations, with an emphasis on decision making, a key element of informed consent.

Bockting and Coleman, in a move representative of other publications of this era, advocated for a more comprehensive approach to the mental health evaluation and treatment of gender dysphoria. Their treatment model was comprised of five main components: a mental health assessment consisting of psychological testing and clinical interviews with the individual, couple, and/or family; a physical examination; management of comorbid disorders with pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy; facilitation of identity formation and sexual identity management through individual and group therapy; and aftercare consisting of individual, couple, and/or family therapy with the option of a gender identity consolidation support group. Psychoeducation was a main thread throughout the treatment model and a variety of treatment “subtasks” such as understanding decision making, sexual functioning and sexual identity exploration, social support, and family of origin intimacy were identified as important. The authors advocated for “a clear separation of gender identity, social sex role, and sexual orientation which allows a wide spectrum of sexual identities and prevents limiting access to GAS to those who conform to a heterosexist paradigm of mental health” ( 33 ).

This process can be compared with the Italian SOC for GAS which recommend a multidisciplinary assessment consisting of a psychosocial evaluation and informed consent discussion around treatment options, procedures, and risks. Requirements included 6 months of psychotherapy prior to initiating GAH, 1 year of a RLT prior to GAS, and provision of a court order approving GAS, which could not be granted any sooner than 2 years after starting the process of gender transition. Follow-up was recommended at 6, 12, and 24 months post-GAS to ensure psychosocial adjustment to the affirmed gender role ( 34 ).

Other authors continued to refine inclusion and exclusion criteria for GAS by surveying the actual practices of health centers. Inclusion criteria included those who had life-long cross gender identification with inability to live in their sex assigned at birth; a 1–2 years RLT (a nearly universal requirement in the survey); and ability to pass “effortlessly and convincingly in society”; completed 1 year of GAH; maintained a stable job; were unmarried or divorced; demonstrated good coping skills and social-emotional stability; had a good support system; and were able to maintain a relationship with a psychotherapist. Exclusion criteria included age under 21 years old, recent death of a parent ( 35 ), unstable gender identity, unstable psychosocial circumstances, unstable psychiatric illness (such as schizophrenia, suicide attempts, substance abuse, intellectual disability, organic brain disorder, AIDS), incompatible marital status, criminal history/activity or physical/medical disability ( 36 ).

The survey indicated some programs were more lenient around considering individuals with bipolar affective disorder, the ability to pass successfully, and issues around family support. Only three clinics used sexual orientation as a factor in decision for GAS, marking a significant change in the literature from prior decades. Overall, the authors found that 74% of the clinics surveyed did not adhere to WPATH SOC, instead adopting more conservative policies ( 36 ).

Standards of care version 5

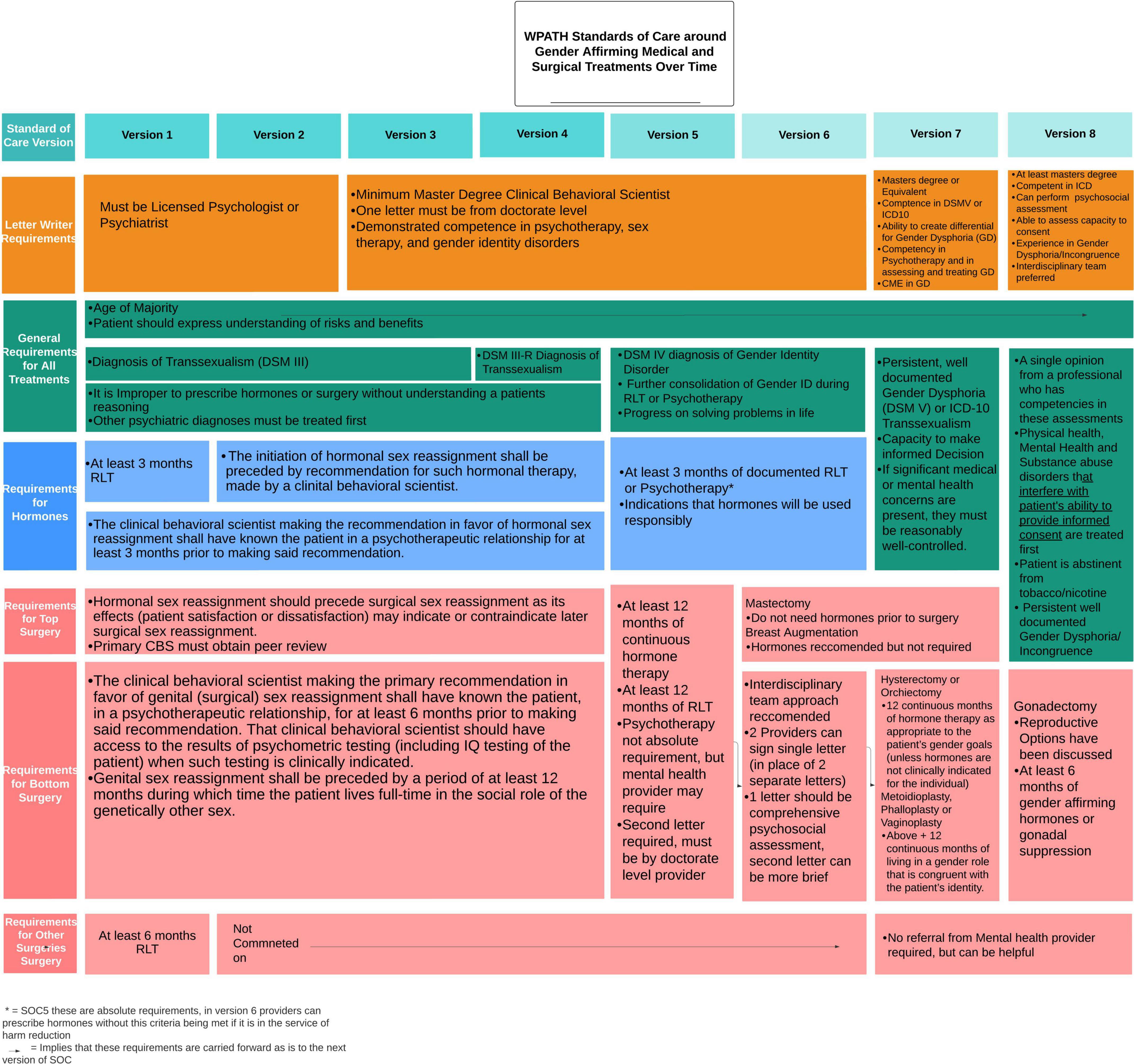

Published in 1998, version five defined the responsibilities of the mental health professional which included diagnosing the gender disorder, diagnosing and treating co-morbid psychiatric conditions, counseling around GAC, providing psychotherapy, evaluating eligibility and readiness criteria for GAC, and collaborating with medical and surgical colleagues by writing letters of recommendation for GAC ( Figure 3 ). Eligibility and readiness criteria were more explicitly described in this version to refer to the specific objective and subjective criteria, respectively, that the patient must meet before proceeding to the next step of their gender transition. The seven elements to include in a letter of readiness were more explicitly listed within this version as well including: the patient’s identifying characteristics, gender, sexual orientation, any other psychological diagnoses, duration and nature of the treatment with the letter writer, whether the author is part of a gender team, whether eligibility criteria have been met, the patient’s ability to follow the SOC and an offer of collaboration. Version five removes the requirement that patients undertake psychotherapy to be eligible for GAC ( 37 ).

Figure 3. Changes to the ten tasks of the mental health provider within the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care over time.

Five articles were published between 1998 and 2001 while version five was active. Two of these articles were summaries of the SOC ( 37 , 38 ). Themes in these publications included continued attempts to develop comprehensive treatment models for GAS.

Ma reviewed the role of the social worker in a multidisciplinary gender clinic in Hong Kong. Psychosocial assessment for GAS included evaluation of performance in affirmed social roles, adaptation to the affirmed gender role during the 1-year RLT and understanding the patient’s identified gender role and the response to the new gender role culturally and interpersonally within the individual’s support network and family unit. She noted five contraindications to GAS: a history of psychosis, sociopathy, severe depression, organic brain dysfunction or “defective intelligence,” success in parental or marital roles, “successful functioning in heterosexual intercourse,” ability to function in the pretransition gender role, and homosexual or TV history with genital pleasure. She proposed a social work practice model for patients who apply for GAS with categorization of TGD individuals into “better-adjusted” and “poorly-adjusted” with different intervention goals and methods for each. For those who were “better-adjusted,” treatment focused on psychoeducation, building coping tools, and mobilization into a peer counselor role, while treatment goals for those who were “poorly-adjusted” focused on building support and resources ( 39 ).

Damodaran and Kennedy reviewed the assessment and treatment model used by the Monash gender dysphoria clinic in Melbourne, Australia for patients requesting GAS. All referrals for GAS were assessed independently by two psychiatrists to determine proper diagnosis of gender dysphoria, followed by endocrinology and psychology consultation to develop a comprehensive treatment plan. Requirements included RLT of minimum 18 months and GAH ( 40 ).

Miach reviewed the utility of using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), a revision of the MMPI which was standardized using a more heterogeneous population, in a gender clinic to assess stability of psychopathology prior to GAS, which was only performed on patients aged 21–55 years old. The authors concluded that while the TGD group had a significantly lower level of psychopathology than the control group, they believed that the MMPI-2 was a useful test in assessing readiness for GAC ( 41 ).

Standards of care version 6

Published in 2001, version six of the WPATH SOC did not include significant changes to the 10 tasks of the mental health professional ( Figure 3 ) or in the general recommendations for content of the letters of readiness. An important change in the eligibility criteria for GAH allowed providers to prescribe hormones even if patients had not undergone RLT or psychotherapy if it was for harm reduction purposes (i.e., to prevent patient from buying black market hormones). A notable change in version six separated the eligibility and readiness criteria for top (breast augmentation or mastectomy) and bottom (any gender-affirming surgical alteration of genitalia or reproductive organs) surgery allowing some patients, particularly individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB), to receive a mastectomy without having been on GAH or completing a 12 month RLT ( 42 , 43 ).

Thirteen articles were published between 2001 and 2012. One is a systematic review of evidence for factors that are associated with regret and suicide, and predictive factors of a good psychological and social functioning outcome after GAC. De Cuypere and Vercruysse note that less than one percent of patients regret having GAS or commit suicide, making detection of negative predictive factors in a study nearly impossible. They identified a wide array of positive predictive factors including age at time of request, sex of partner, premorbid social or psychiatric functioning, adequacy of social support system, level of satisfaction with secondary sexual characteristics, and surgical outcomes. Many of these predictive factors were later disproved. They also noted that there were not enough studies to determine whether following the WPATH guidelines was a positive predictive factor. In the end they noted that the evidence for all established evaluation regimens (i.e., RLT, age cut-off, psychotherapy, etc.) was at best indeterminate. They recommended that changes to WPATH criteria should redirect focus from gender identity to psychopathology, differential diagnosis, and psychotherapy for severe personality disorders ( 44 ).