- Politics & Social Sciences

- Anthropology

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- ISBN-10 0198575017

- ISBN-13 978-0198575016

- Publisher Clarendon Press

- Publication date August 21, 1997

- Language English

- Dimensions 9 x 1.5 x 11.4 inches

- Print length 632 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Clarendon Press (August 21, 1997)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 632 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0198575017

- ISBN-13 : 978-0198575016

- Item Weight : 5.15 pounds

- Dimensions : 9 x 1.5 x 11.4 inches

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

Top reviews from other countries.

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Home

- Research Collections

- Interdisciplinary and Peer-Reviewed

Koobi Fora research project, volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology

3.0.CO;2-6">

Collections

- Anthropology, Department of

Remediation of Harmful Language

The University of Michigan Library aims to describe library materials in a way that respects the people and communities who create, use, and are represented in our collections. Report harmful or offensive language in catalog records, finding aids, or elsewhere in our collections anonymously through our metadata feedback form . More information at Remediation of Harmful Language .

Accessibility

If you are unable to use this file in its current format, please select the Contact Us link and we can modify it to make it more accessible to you.

- DOI: 10.2307/530627

- Corpus ID: 131748378

Koobi Fora Research Project, Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- Creighton Gabel , G. Isaac

- Published 21 January 1999

- Journal of Field Archaeology

31 Citations

A technological analysis of the oldowan and developed oldowan assemblages from olduvai gorge, tanzania.

- Highly Influenced

- 10 Excerpts

Hominin diversity and high environmental variability in the Okote Member, Koobi Fora Formation, Kenya.

Crevasse‐splay and associated depositional environments of the hominin‐bearing lower okote member, koobi fora formation (plio‐pleistocene), kenya, new excavations in the mnk skull site, and the last appearance of the oldowan and homo habilis at olduvai gorge, tanzania, an integrated study discloses chopping tools use from late acheulean revadim (israel), semiotics and the origin of language in the lower palaeolithic, earliest african evidence of carcass processing and consumption in cave at 700 ka, casablanca, morocco, lithic raw material procurement through time at swartkrans: earlier to middle stone age, geoarchaeological analysis of two new test pits at the dmanisi site, republic of georgia, paleosol carbonates from the omo group: isotopic records of local and regional environmental change in east africa, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Daily Deals

- Help & Contact

- Watch List Expand watch list Loading... Sign in to see your user information

- Recently Viewed

- Bids/Offers

- Purchase History

- Saved Searches

- Saved Sellers

- Collect & Spend Learn more

- Expand Basket Loading... Something went wrong. View basket for details.

Picture 1 of 1

Koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology by glynn ll. isaac, barbara isaac (hardcover, 1997).

- BOOKS etc. (470282)

- 99.6% positive Feedback

- View all details

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.

Refresh your browser window to try again.

All listings for this product

Item 1 koobi fora research project: volume 5 - 9780198575016 koobi fora research project: volume 5 - 9780198575016, item 2 koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology, about this product, product information.

- This is the fifth volume in the important Koobi Fora series on human origins, covering archaeological finds from excavations at East Turkana in northern Kenya. Volume 5 concentrates on the evidence from the period between 1.9 and 0.7 million years ago and reconstructs the behaviour of early human ancestors. The book answers such questions as: How were the stone tools made and utilized? How large were the groups of hominids, and how mobile? Do animal bones really give us a true impression of what food they ate? The stone artefacts, bones, and features of the ancient landscape recorded in this book provide a solid basis for further work on human evolution.

Product Identifiers

- Publisher Oxford University Press

- ISBN-13 9780198575016

- eBay Product ID (ePID) 90077901

Product Key Features

- Series Koobi Fora Research Project

- Author Glynn Ll. Isaac, Barbara Isaac

- Publication Name Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

- Format Hardcover

- Language English

- Subject Archaeology, Anthropology, Biology, History

- Publication Year 1997

- Type Textbook

- Number of Pages 632 Pages

- Item Height 314 mm

- Item Width 228 mm

- Item Weight 2389 g

Additional Product Features

- Editor Glynn Ll. Isaac, Barbara Isaac

- Country/Region of Manufacture United Kingdom

Best-selling in Adult Learning & University

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- Best-selling in Adult Learning & University

Secrets Of Mental Math: The Mathemagician's Guide to Lightening Calculation and Amazing Maths Tricks by Arthur Benjamin, Michael Shermer (Paperback, 2006)

The miraculous cure for and prevention of all diseases what doctors never learned by jeff t bowles (paperback, 2019), the hairy bikers eat to beat type 2 diabetes: 80 delicious & filling recipes to get your health back on track by hairy bikers (paperback, 2020), the manipulated man by esther vilar (paperback, 2008), the personal mba: a world-class business education in a single volume by josh kaufman (paperback, 2012), never split the difference: negotiating as if your life depended on it by chris voss, tahl raz (paperback, 2017), last voyage of the lucette: the full, previously untold, story of the events first described by the author's father, dougal robertson, in survive the savage sea. interwoven with the original narrative. by douglas robertson (paperback, 2005).

- £13.99 Used

Save on Adult Learning & University

Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days.

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- Save on Adult Learning & University

The Miraculous Cure For and Prevention of All Diseases What Doctors Never Lea...

Type 2 diabetes cookbook for beginners 1500 days of easy & tasty recipes for ..., prince2® 7 managing successful projects - official manual for prince2 v7 exams, die with zero: getting all� you can from your money and - paperback english, ks1 english targeted practice book handwriting year 1 ideal for catch up and le, cognitive behavior therapy : basics and beyond, hardcover by beck, you may also like.

Current slide {CURRENT_SLIDE} of {TOTAL_SLIDES}- You may also like

Koobi Fora research project, volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology

- John D. Speth

- Earth Science

- Classical Studies

Similar works

Deep Blue Documents at the University of Michigan

This paper was published in Deep Blue Documents at the University of Michigan .

Having an issue?

Is data on this page outdated, violates copyrights or anything else? Report the problem now and we will take corresponding actions after reviewing your request.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 June 2023

Early Pleistocene cut marked hominin fossil from Koobi Fora, Kenya

- Briana Pobiner 1 ,

- Michael Pante 2 &

- Trevor Keevil 3

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 9896 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

1 Citations

1438 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Archaeology

- Biological anthropology

Identification of butchery marks on hominin fossils from the early Pleistocene is rare. Our taphonomic investigation of published hominin fossils from the Turkana region of Kenya revealed likely cut marks on KNM-ER 741, a ~ 1.45 Ma proximal hominin left tibia shaft found in the Okote Member of the Koobi Fora Formation. An impression of the marks was created with dental molding material and scanned with a Nanovea white-light confocal profilometer, and the resulting 3-D models were measured and compared with an actualistic database of 898 individual tooth, butchery, and trample marks created through controlled experiments. This comparison confirms the presence of multiple ancient cut marks that are consistent with those produced experimentally. These are to our knowledge the first (and to date only) cut marks identified on an early Pleistocene postcranial hominin fossil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nubian Levallois technology associated with southernmost Neanderthals

The earliest cut marks of Europe: a discussion on hominin subsistence patterns in the Orce sites (Baza basin, SE Spain)

New hominin remains and revised context from the earliest Homo erectus locality in East Turkana, Kenya

Introduction.

While it is assumed that Pliocene and early Pleistocene hominins were sometimes the victims of predation by the many taxa of larger carnivores with which they coexisted, taphonomic evidence for such interactions in the form of carnivore chewing damage or tooth marks on hominin fossils is relatively uncommon. In 2011, Hart and Sussman 1 listed 10 hominins dated to between 6 million years ago and 50,000 years ago with evidence of terrestrial carnivore or raptor predation; this list does not include carnivore damage on Australopithecus anamensis fossils from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya 2 , 3 and Australopithecus africanus fossils from Member 4 of Sterktfontein, South Africa 4 ; a tooth mark on the pelvis of the AL 288–1 (“Lucy”) Australopithecus afarensis partial skeleton from Hadar, Ethiopia ( 5 , though see 6 for an alternate interpretation of this mark); tooth marks on the Paranthropus robustus SK 54 cranium from Swartkrans, South Africa 7 ; and at least two Homo habilis specimens from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania with evidence of crocodile predation 8 .

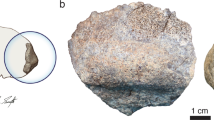

In July 2017, one of us (Pobiner) undertook a pilot study of the taphonomy of published hominin postcranial fossils from the Turkana region of Kenya dated to ~ 1.8 to 1.5 Ma, with an expectation of potentially finding some carnivore damage on these fossils. However, she unexpectedly observed potential butchery marks on a single fossil: KNM-ER 741 (Fig. 1 ). This observation was unexpected because while butchery marks left by hominins on animal fossils beginning by at least the early Pleistocene point to increased meat and marrow acquisition during the evolution of the genus Homo 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 and hundreds of cut marked fossils of other animals have been identified from the Okote Member of the Koobi Fora Formation 13 , 14 , 15 , no cut marks on hominin fossils from this temporal and geographic area have been reported.

Complete view of tibia (KNM-ER 741) and magnified area that shows cut marks perpendicular to the long axis of the specimen. Scale = 4 cm.

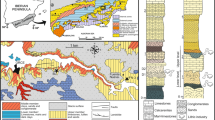

In 1970, Mary Leakey found the proximal half of a left tibia, KNM-ER 741 16 , 17 . A surface discovery, Leakey retrieved the fossil from exposures of the Okote Member, Koobi Fora Formation in Area 1 of the Ileret region. While 15 additional hominin specimens were found during the same research expedition in 1970, no additional information is available regarding the discovery of this fossil and the information about it in the Koobi Fora monograph does not specify whether other hominin fossils were found nearby. Its stratigraphic position is noted as “Ileret member, c. 2–4 m above the top of the Lower/Middle Tuff (collection unit 5)” with a depositional environment of “Fluvial, probably the edge of a channel” and additional notes that “The sand matrix on KNM-ER 741, a surface find, indicates association with the channel lens rather than more proximal fine-grained sediments” ( 16 , 17 : 110). Anna K. Behrensmeyer’s unpublished field notes from her 1973 documentation of the context of the site indicate that some faunal specimens were found in the general vicinity of the KNM-ER 741 discovery; a few may have been collected. Her field notes include a description of the surfaces of the tibia as relatively fresh with slight weathering of the bone grain, fine longitudinal cracking which could be pre-depositional weathering, and no major cracks. She observed some dissolution and whitening of the surface, some sand was in the trabeculae exposed along the edge of the proximal articulation, the marrow cavity was hollow without matrix, and the distal break (on the midshaft) had both fresh and ancient fractures (A.K. Behrensmeyer, pers. comm. ).

KNM-ER 741 was originally attributed to Australopithecus boisei when it was first published by Richard Leakey 16 , 17 and then described by Leakey and colleagues 18 . Two decades later, Alan Walker revised the taxonomic attribution of this specimen to Homo erectus based on comparison with KNM-WT 15000, the “Turkana Boy” or Nariokotome partial juvenile skeleton 19 . The entry about KNM-ER 741 in the Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution says “current conventional taxonomic allocation is H. erectus or Hominin gen et sp. indet.” and “because so little is known about the tibial morphology of early hominins other than Australopithecus afarensis it may be premature to rule out the possibility that it belongs to Homo habilis or Paranthropus boisei ” 20 . Due to the taxonomic uncertainty of this fossil, we simply refer to it in this study as a hominin (hominin gen. et sp. indet). The age of the fossil is estimated to be about 1.45 Ma 20 .

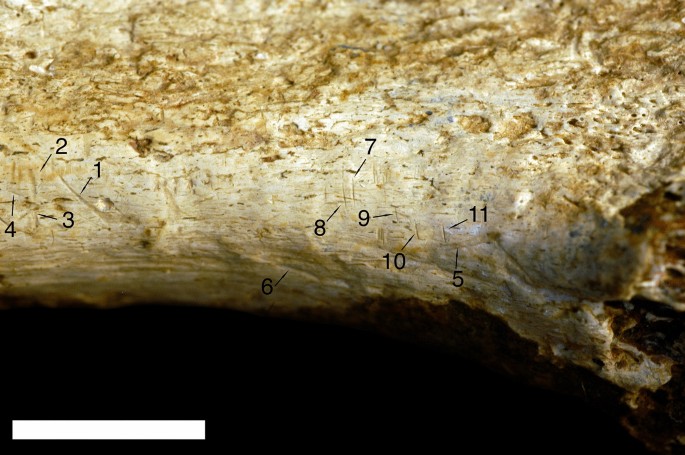

While examining KNM-ER 741 at the National Museums of Kenya Nairobi Museum, Pobiner identified a series of bone surface modifications on the medial side of the proximal shaft which appeared consistent with stone tool cut marks (Fig. 1 ). Pobiner created an impression of 11 of these marks with dental molding material. After she returned to the US, Pobiner sent the molds to Pante and Keevil for analysis and comparison to marks on modern bones made by known processes without any contextual or other information about the bone the marks were on, although Pante knew that she had been doing research at the National Museums of Kenya.

This fossil specimen is a nearly complete proximal tibia with the proximal end, proximal shaft, and midshaft present. The specimen has a transverse and longitudinal (not spiral) ancient and modern fracture on the distal shaft. Most of the surface of this fossil specimen is darkly colored (likely manganese stained) with a poorly preserved, rough appearing cortical surface due to weathering, abrasion, and/or some other physical or chemical process. In the original description of the fossil, it is noted that “the margins of the articular surfaces have been abraded” ( 16 , 17 :110). However, the relatively small area where these marks occur is yellow-whitish colored with very good cortical bone surface preservation. No other bone surface modifications were observed on any other parts of the specimen outside of this area. No information on whether this specimen has undergone any preparation since it was discovered exists, though no preparation or excavation damage was detected. The marks observed and described here are the same color as the rest of the bone surface, so they are unlikely to be modern damage. No cleaning of the marks or any other preparation of this fossil was carried out during this study.

The majority of the bone surface modifications identified and studied here are short, narrow linear marks with a straight trajectory and a closed-V-shaped cross section, oriented in the same direction: transverse and slightly oblique to the long bone axis. The V-shape of these marks and their straight trajectories are strong indicators that they are cut marks 21 . They are not shallow, fine, randomly oriented striae which are randomly distributed on various parts of the fossil; these features are characteristics of sedimentary abrasion 21 . The marks also do not look similar to other non-anthropogenic agents which can inflict linear marks, such as insects, plant roots, or raptor beaks 22 . While internal striations were not observed, this feature can be difficult to observe without higher (at least 40×) magnification. Shoulder effects were observed on some of the marks (Fig. 2 ). Flaking effects were not observed on these marks. Flaking effects are more likely to occur with retouched versus unretouched flakes 21 , and in our experience are less often identified on fossilized bones when compared to modern butchered bones. These marks all occur in the same general area on the shaft of the bone; some are isolated while others occur in groups, adjacent to each other in patches. While it is possible that the marks occurred recently (after the bone was fossilized), we think this is unlikely because the color of the marks is not different from the color of the area of the bone on which they occur, and the marks are neither randomly oriented nor randomly distributed.

3D model of marks 7 and 8 identified as cut marks by the quadratic discriminant model.

Of the 11 marks measured, 9 were classified as cut marks and 2 as tooth marks (Table 1 , Figs. 3 and 4 ). Six of the cut marks were classified with posterior probabilities near or above 90% indicating a high level of confidence in the identification (see Fig. 3 for an image that identifies all of the analyzed marks). This accords with the qualitative observations and descriptions of the marks above. The two marks classified as tooth marks were compared with 163 known marks inflicted by bone crunching carnivores (Hyaenidae, Canidae, Crocodylidae), and 58 known marks from flesh specialist carnivores (Felidae). The quadratic model can discriminate between bone crunching carnivores and flesh specialist felids (only represented by African lions) with 77% accuracy. Results show both marks classify with marks made by flesh specialists with posterior probabilities of 100% (see Fig. 5 for a comparison between mark 5 and a modern lion tooth mark).

Results of quadratic discriminant analysis. Archaeological specimens are identified by their given ID numbers. Circles encompass 50% of the data for each mark type. The model is shown in two dimensions here, but has a third canonical dimension.

Nine marks identified as cut marks (mark numbers 1–4 and 7–11) and two identified as tooth marks (mark numbers 5 and 6) based on comparison with 898 known bone surface modifications using a quadratic discriminant analysis of the micromorphological measurements collected in the study. Scale = 1 cm.

A closeup of mark 5 and the processed 3-D model compared with a modern lion tooth mark.

Human anthropophagy: definitions and taphonomic criteria

Anthropophagy is often used synonymously with cannibalism, but the former can be defined as occasional consumption of humans by other humans while the latter usually implies a cultural practice 23 . Cannibalism is defined as the act of consuming tissues of individuals of the same species 24 and occurs in over 1300 species of animals in the wild, including several primates 25 . In the case of this hominin fossil tibia, we do not know the identity of the species of the consumer (the species which inflicted the butchery marks) nor the consumed (the species of the hominin tibia). Because of this lack of information, we cannot make a claim of cannibalism based on the evidence presented here. However, due to the possibility that an individual of the same species of hominin to which the tibia belongs also inflicted the cut marks on the tibia, we include a discussion about hominin anthropophagy, which can include cannibalism.

Previous researchers have defined and described the various motivations or contexts for human cannibalism in different ways, including: survival; gastronomic or dietary; aggressive; psychotic or criminal; warfare; affectionate; funerary, ritual, spiritual, or magical; and medicinal (e.g., 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ). These types of cannibalism have also sometimes been subdivided into social divisions that include aggressive (consuming enemies) versus affectionate (consuming friends or relatives), or endocannibalism (consumption of individuals within the group, usually associated with sacred beliefs and spiritual regeneration of the deceased) versus exocannibalism (consumption of outsiders, usually associated with hostility and violence) 26 .

Biological anthropologists and archaeologists have generated taphonomic criteria for different kinds of cannibalism to better understand the intent of anthropogenic modification of hominin skeletal remains. These include abundant anthropogenic modifications on more than 20% of human remains; intensive processing of bodies; greater abundance of cut marks related to defleshing and filleting than dismembering; the presence of human tooth marks or chewing damage; and the similar treatment of human and animal remains 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 . Differentiating between nutritional and ritual cannibalism is primarily based on a comparison of the taphonomic traces on and post-processing discard patterns of hominin and non-hominin remains 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 33 . Evidence for marrow and brain extraction are additional indications of nutritional cannibalism, while ritual cannibalism might be inferred in instances of defleshing without marrow extraction 25 . Saladié et al. 33 recently found that high frequencies of anthropogenic modifications (> 30%) are common after an intensive butchering process intended to prepare a hominin body for consumption in different contexts, contradicting previously held assumptions about cut mark intensity. A full discussion of these past behaviors and the criteria used to identify them are outside the context of this study, though they are briefly summarized here; in order to apply these criteria, richer contextual evidence than what was found with KNM-ER 741 is necessary.

A more recent study by Bello et al. of four archaeological sites (one interpreted as cannibalism and three interpreted as funerary defleshing and disarticulation after a period of decay) determined that a distinction between butchery marks reflecting cannibalism of fresh bodies and secondary burials of bodies at various stages of decomposition can be made based on frequency, distribution, and micromorphometric characteristics of cut marks 34 . This study concluded that cannibalized sites exhibit higher frequencies of cut marks overall, but especially disarticulation cut marks on both persistent and labile joints, while secondary burial sites exhibit low frequencies of cut marks on labile joints because they have been naturally disarticulated over time. Bello et al. found that disarticulation cut marks at the cannibalized site (Gough’s Cave, UK) were deeper and wider than filleting marks at all four archaeological sites, but that filleting marks on long bones associated with larger muscles (humerus, femur, and tibia) were wider and deeper than those on other long bones (radius, ulna, and fibula). They also found that cut marks on the bones from the funerary defleshing sites (Lepenski Vir, Padina, and Vlasac, Serbia) were wider and deeper than cut marks found on other butchered animals at the site, implying the use of more strength to deflesh human bodies, possibly due to “the difficulty in removing remnant tissue on partially desiccated remains” ( 34 :739).

Given the lack of evidence in the Early Pleistocene for primary or secondary burial, or other ritual behaviors, we think only one of the three functional types of human cannibalism outlined by Fernández-Jalvo et al. 26 is potentially applicable to this study: nutritional cannibalism. Nutritional cannibalism occurs for the sole purpose of obtaining food and can be divided into two categories: (1) incidental cannibalism, which is focused on survival; this occurs in periods of food scarcity or due to catastrophes, i.e., is starvation-induced; (2) long duration cannibalism, which is also called gastronomic or dietary cannibalism; humans are simply part of the diet of other humans.

Features of human tooth marks on bones have been identified through experimental studies and applied to some fossil assemblages with other evidence of cannibalism (e.g., 22 , 35 , 36 ). Fernández-Jalvo and Andrews 35 identified bent ends/fraying on thin bones such as ribs and vertebrae apophyses; crenulated or chewed edges, often with a double arch puncture; tooth punctures usually left by molars or premolars which are most often triangular, dispersed, small (< 4 mm), and occur infrequently; and shallow linear marks left by incisors which are usually superficial, less deep and distinct than carnivore tooth scores, and not easily distinguishable without magnification. Saladié et al. 36 further identified furrowing and scooping out of long bone epiphyses; crenulated and saw-toothed edges on flat bones, sometimes associated with notches; longitudinal cracks; crushing; peeling and bent ends; and pits, punctures, and scores. In their study, tooth punctures and pits tended to have irregular contours, including crescent shapes; tooth scores were primarily shallow, some with flaking on the shoulder or bottom of the groove, and a few with microstriations on the core walls and bottoms. These experimental studies were conducted on sheep, pig and rabbits, including some juveniles and subadults, and some raw and some cooked samples 35 , 36 . While there are currently no human tooth marks in our comparative sample, based on the lack of other features of human tooth marks and chewing damage outlined in previous research, and the fact that human tooth marks have most often been identified on modern and fossil bones of smaller sized taxa and skeletal elements than this hominin tibia, we think it is possible but unlikely that the tooth marks on this fossil hominin tibia are hominin tooth marks.

The two BSM classified as tooth marks are most similar to those produced by a felid (Fig. 5 ). In our known sample of tooth marks, felids are only represented by the modern lion. While often considered to be hunters, lions are opportunistic in acquiring carcass foods and scavenge frequently. In wooded habitats lions kill between 78 and 88% of their food, but only kill about 47% of their food in open habitats 37 . This is most likely the result of an abundance of hyenas, from which lions frequently scavenge, and the visibility of vultures that can be followed to kills by lions in open habitats 37 . Lions will also scavenge from leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs, jackals, and when available, from animals that died from disease or malnutrition 37 . Given the variability in lion behavior and the presence of both cut marks and tooth marks on the fossil hominin tibia, it is not possible to infer the cause of death of the individual, or even the primary consumer. However, the location of the cut marks on the posterior tibia shaft suggests that flesh was likely on the carcass at the time that the cut marks were inflicted.

Evidence for Pleistocene hominin butchery marks on hominins

There is uncontested evidence for cannibalism in European Neanderthals from sites in Belgium (Troisième Caverne of Goyet), France (Moula-Guercy and Padrelles), Spain (Cueva del Sidrón and Cueva del Boquete de Zafarraya), and Croatia (Krapina) (see 24 , 25 and references therein). There is also evidence for both anthropogenic defleshing and cannibalism in Homo sapiens from sites in Ethiopia (Herto), Poland (Maszycka Cave), the UK (Gough’s Cave), and possibly Germany (Brillenhöhle) (see 23 and references therein). Yet there are still only a handful of Pleistocene sites with evidence for hominin cannibalism 24 , 25 , and only four published examples of postmortem defleshing on hominin fossils other than Neanderthals and Homo sapiens . We describe these examples in more detail here, in order from youngest to oldest.

Though slightly younger than the Early Pleistocene at ~ 600,000 years old, the first observation of cut marks on an early hominin was made by White 38 on the Bodo cranium from the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia. White identified 17 areas with diagnostic cut marks on the Bodo cranium and used scanning electron microscopy to investigate some of the cut marks. He also studied crania of modern apes intentionally defleshed with steel knives during the early 1900s now housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History for comparison. He was able to match the placement and orientation of each set of the Bodo cut marks among these apes, despite differences in gross cranial morphology and tool type employed. He interpreted the marks on the Bodo cranium as patterned intentional postmortem defleshing of this specimen by a hominin with a stone tool 38 .

There is some evidence for processing on some of the at least 30 Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus individuals from Caune de l ‘Argo (also known as Arago Cave) in Tautavel, France, most dated to the ~ 680,000 year old Middle Pleistocene middle G and F levels. While a systematic taphonomic study of this site has not yet been undertaken, de Lumley 39 described the remains, primarily from level G, as showing the presence of abundant cut marks on skulls and limb bones and green breakage of long bones. The difference in skeletal part profiles of hominins and non-hominin animals from Arago Cave led de Lumley to suggest that the hominin bones present at the site—skulls, mandibles, long limb bones, and a pelvic girdle—were anthropogenically selected and possibly related to ritualistic cannibalism. Cole 25 noted that postcranial remains at this site were processed differently than cranial remains, also raising the possibility of ritual cannibalism. However, Saladié and Rodríguez-Hidalgo 24 propose that the near absence of axial bones at Arago Cave could be the result of other processes, such as post-depositional destruction (which is more likely to affect these skeletal elements) or difficulties in taxonomic identification; they suggest that the taphonomic damage on the Arago hominins may not be due to ritual behavior.

Fernández-Jalvo et al. 26 , 40 first identified butchery marks among the ~ 772,000 to 949,000 year old Homo antecessor remains from Gran Dolina, which is part of the karstic site complex of the Sierra de Atapuerca in northern central Spain. The taphonomic analyses of human fossils from the TD6-Aurora Stratum of Gran Dolina, using a binocular light microscope as well as scanning electron microscopy, included identification not only of cut marks (including slicing marks, chop marks, and scraping marks), but also of percussion pits, peeling, conchoidal fracture, and adhering flakes. They found evidence of hominin-induced breakage, butchery marks, and human tooth marks on 44.5% of Homo antecessor bones, including many different skeletal elements, suggesting scalping, skinning, disarticulation, evisceration, and defleshing aimed at meat, marrow, and brain extraction 26 , 40 . The patterning of butchery damage on the Homo antecessor remains was generally similar to the patterning of damage on the non-human animal remains and was consistent with those bones that held the most nutritional value, as was the spatial distribution of human and non-human animal remains 26 , 40 . They found no evidence of ritual treatment and interpreted the butchery mark damage on the assemblage as evidence for nutritional cannibalism, more likely gastronomic cannibalism than survival cannibalism. Carbonell et al. 41 described human meat consumption by Homo antecessor at this site as “frequent and habitual” and concluded that this nutritional cannibalism was accepted and included in their social system. After comparing the age profiles of the butchered Homo antecessor individuals to the age profiles seen in cannibalism associated with intergroup aggression in chimpanzees, Saladié et al. 42 concluded that the Gran Dolina hominins periodically hunted and consumed individuals from another group. With evidence for processing of 11 individuals—2 adults, 3 adolescents, and 6 children 26 —this is arguably the earliest firm evidence of systematic cannibalism in the hominin fossil record, and the only such evidence from the Early Pleistocene.

In 2000, Pickering et al. 43 published what are currently accepted as the oldest cut marks on a hominin fossil: cut marks inflicted by a stone tool on the right maxilla of Stw 53, a partial skull from Sterkfontein Member 5 (or possibly a hanging remnant of Member 4—an area called the STW 53 infill) in South Africa. This skull was first found in 1976 by Alun Hughes and is generally attributed to Homo habilis but is also sometimes argued to represent Australopithecus . Pickering et al. noted that the morphology of the marks, their anatomical placement, and the lack of random striae on the specimen all support an interpretation of this linear damage as cut marks 43 . They state that the location of the marks on the lateral aspect of the zygomatic process of the maxilla is consistent with that expected from slicing through the masseter muscle, presumably to remove the mandible from the cranium, in an act of disarticulation. The age of this fossil is somewhat uncertain; Pickering and Kramers 44 suggest an age between 2.6 and 2.0 Ma, but Wood 20 thinks it is younger, between 2.0 and 1.5 Ma. A more recent reassessment of these marks by Hanon et al. 45 including macro- and microscopic observations concluded that they are not evidence for hominin butchery, but the result of natural processes. They noted that Clarke 46 mentioned that the zygomatic bone of Stw53 was discovered with sharp-edged chert blocks lying against it, which could produce linear marks under sedimentary pressure, and assert that the morphology of these marks is more consistent with trampling marks. Because the marks are located on the masseter muscle insertion of the zygomatic maxillary process they also looked for corresponding marks on the masseter muscle insertion area of the temporal bone, which might be expected in the process of disarticulation or defleshing, but did not find any. While this more recent analysis of the purported cut marks on Stw 53 has not been replicated or confirmed, given the uncertain age of Stw 53, KNM-ER 741 is now at least among the oldest hominin fossils with evidence of hominin butchery marks, and currently is the oldest known hominin butchery marked postcranial fossil.

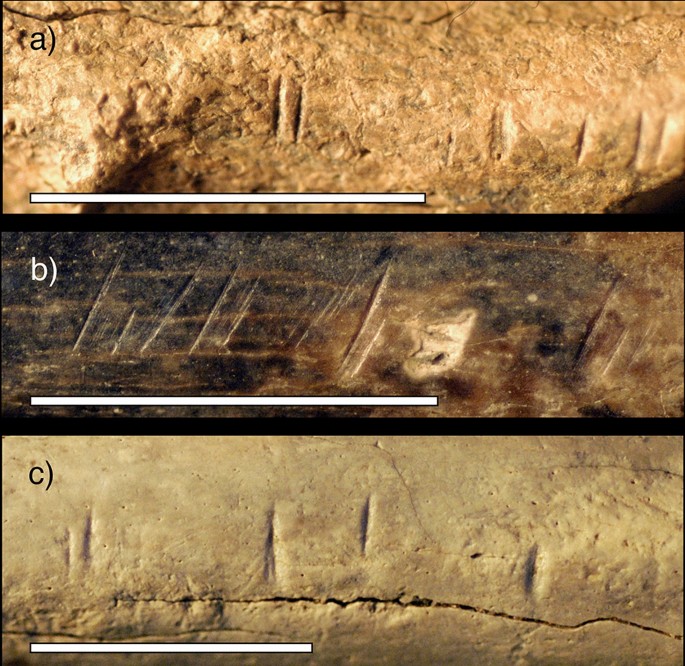

Previous research on butchery marked fauna from multiple sites from the Okote Member of Koobi Fora show that at this time (~ 1.5 million years ago), hominins were consistently using stone tools to deflesh, disarticulate, and extract marrow from a variety of species and sizes of animals from different habitat settings 13 , 14 , 15 . While the morphology of the butchery marks on the Okote Member sites is variable 47 , some generally resemble the marks on KNM-ER 741 (Fig. 6 ). Quantitative analyses of the bone surface modifications on the KNM-ER 741 tibia demonstrate a high level of confidence that the majority were produced by hominins. But what was being cut, exactly, on KNM-ER 741—and why? The cut marks are located on the posterio-medial border of the proximal tibia shaft, near the origin of the popliteus muscle, which rotates the knee medially and flexes the knee joint. The popliteus origin is situated beneath the gastrocnemius, which would have had to be removed for access to the cut marked area. We interpret the location of the cut marks to be more likely the result of defleshing than disarticulation. We conclude that if anthropophagy occurred after the defleshing of KNM-ER 741, it was an opportunistic, practical, and functional activity which occurred simply in the context of obtaining food, rather than one imbued with ritual meaning.

Close up photos of three fossil fauna specimens from archaeological surface finds and excavations in the Okote Member of Koobi Fora (Pobiner 47 ), showing similar cut marks to those found on KNM-ER 741. ( a ) FwJj14B 5097, a bovid size 3 mandible with cut marks on the inferior margin, found in situ ( b ) FwJj14A 1016-97, a bovid size 3 radius midshaft with cut marks, found on the surface ( c ) GaJj14 1056, a large mammal scapula with cut marks along scapular margin, found on the surface. Scale = 1 cm.

Pobiner used a 10X hand lens and bright, high-incident light to look for bone surface modifications on hominin postcranial bones at the National Museums of Kenya, including KNM-ER 741, following methods outlined in Blumenschine et al. 48 . She used Coltene President Plus light body dental molding material to create an impression of the marks analyzed in this study.

The quantitative analysis of bone surface modifications (BSM) followed the protocol presented in Pante et al. 49 . 3-D models of each of the 11 studied BSM were created from an impression of the surface taken from the area of interest on the tibia using a Nanovea ST400 white-light non-contact confocal profilometer equipped with a 3 mm optical pen (objective) that has a resolution of 40 nm on the z-axis. The resolution on the x-axis was set to 5 um and 10 um on the y-axis. Processing and analysis of the 3D model was carried out using Digital Surf's Mountains ® following Pante et al. 49 . Processing included removing outliers, filling in missing data points, and removing the underlying form of the bone. Data collected through the analysis from the entire 3-D model of the BSM were volume, surface area, maximum depth, mean depth, maximum length, and maximum width. Additional data were collected from a profile taken from the deepest point of the BSM including area of the hole, depth of the profile, roughness (Ra), opening angle, and radius of the hole.

These data were statistically compared with a sample of 898 BSM of known origin, including: 402 cut marks from a variety of stone tool types and raw materials; 278 tooth marks from crocodiles and five species of mammalian carnivores; 130 trample marks produced by cows on substrates including sand, gravel, and soil; and 88 percussion marks from both anvils and hammerstones (see Supplemental document 1 for details on the model structure, influential variables, canonical data, and box-cox transformation values). Surface area and depth of the profile were excluded from the statistical analyses because they are highly correlated with volume and maximum depth, respectively, which can lead to overfitting of data. All experimental data were transformed using the Box-Cox method to normalize the distributions for each variable and the same transformations were applied to the archaeological data. Comparisons were carried out using the quadratic discriminant function in JMP® statistical software. The accuracy of the quadratic function in correctly classifying the experimental BSM was 84% when using a 25% validation set. Prior probabilities were set equal to the occurrence of each mark type in the dataset to offset the disproportionate representations of each mark type in the experimental sample.

Data availability

All study data are included in the article.

Hart, D. & Sussman, R. W. The influence of predation on primate and early human evolution: impetus for cooperation. In Origins of Altruism and Cooperation (eds Sussman, R. W. & Cloninger, C. R.) 19–40 (Springer, 2011).

Chapter Google Scholar

Leakey, M. G., Feibel, C. S., McDougall, I., Ward, C. & Walker, A. New specimens and confirmation of an early age for Australopithecus anamensis . Nature 393 , 62–66 (1998).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ward, C. V., Leakey, M. G. & Walker, A. C. The new hominid species Australopithecus anamensis . Evol. Anth. 7 , 197–205 (1999).

Article Google Scholar

Pickering, T. R., Clarke, R. J. & Moggi-Cecchi, J. Role of carnivores in the accumulation of the Sterkfontein Member 4 hominid assemblage: A taphonomic reassessment of the complete hominid fossil sample (1936–1999). Am. J. Phys. Anth. 125 , 1–15 (2004).

Johanson, D. C. et al. Morphology of the Pliocene partial hominid skeleton (A.L. 288-1) from the Hadar formation, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anth. 57 , 403–451 (1982).

Kappelman, J. et al. Reply to: Charlier et al. 2018. Mudslide and/or animal attack are more plausible causes and circumstances of death for AL 288 (‘Lucy’): a forensic anthropology analysis. Medico-Legal Journal 86(3) 139–142, 2018. Med.-Legal J. 87 (3), 121–126 (2018).

Brain, C. K. The Hunters or the Hunted. An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy (The University of Chicago Press, 1981).

Google Scholar

Njau, J. K. & Blumenschine, R. J. Crocodylian and mammalian carnivore feeding traces on hominid fossils from FLK 22 and FLK NN 3, Plio-Pleistocene, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. J. Hum. Evol. 63 (2), 408–417 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pobiner, B. L. The zooarchaeology and paleoecology of early hominin scavenging. Evol. Anth. 29 , 68–82 (2020).

Barr, W. A., Pobiner, B., Rowan, J., Du, A. & Faith, J. T. No sustained increase in zooarchaeological evidence for carnivory after the appearance of Homo erectus . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (5), e2115540119 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Plummer, T. L. et al. Expanded geographic distribution and dietary strategies of the earliest Oldowan hominins and Paranthropus . Science 379 (6632), 561–566 (2023).

Espigares, M. P. et al. The earliest cut marks of Europe: A discussion on hominin subsistence patterns in the Orce sites (Baza basin, SE Spain). Sci. Rep. 9 , 15408 (2019).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pobiner, B. L., Rogers, M. J., Monahan, C. M. & Harris, J. W. K. New evidence for hominin carcass processing strategies at 1.5 Ma, Koobi I, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 55 (1), 103–130 (2008).

Merritt, S. R. Investigating hominin carnivory in the Okote Member of KoIFora, Kenya with an actualistic model of carcass consumption and traces of butchery on the elbow. J. Hum. Evol. 112 , 105–133 (2017).

Merritt, S. R., Mavuso, S., Cordiner, E. A., Fetchenhier, K. & Greiner, E. FwJj70: A potential early stone age single carcass butchery locality preserved in a fragmentary surface assemblage. J. Arch. Sci. Rep. 20 , 736–747 (2018).

Leakey MG, Leakey RE, editors. Koobi Fora Research Project Volume 1: The Fossil Hominids and an Introduction to Their Context, 1968-1974. Oxford University Press; 1977. 191 pp.16.

Leakey, R. E. Further evidence of lower Pleistocene hominids from East Rudolf, North Kenya. Nature 231 (5300), 241–245 (1971).

Leakey, R. E. Further evidence of lower Pleistocene hominids from East Rudolf, North Kenya, 1972. Nature 242 (5394), 170–173 (1973).

Walker A, Leakey R, editors. The Nariokotome Homo Erectus Skeleton. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1993. 458 pp.

Wood, B. Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution 1922 (Wiley, 2011).

Book Google Scholar

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., de Juana, S., Galán, A. B. & Rodríguez, M. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks. J. Arch. Sci. 36 (12), 2643–2654 (2019).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. Atlas of Taphonomic Identifications. 1001+ Images of Fossil and Recent Mammal Bone Modification 360 (Springer, 2016).

Cole, J. Assessing the calorific significance of episodes of human cannibalism in the Palaeolithic. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 44707 (2017).

Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Saladié, P. & Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. Archaeological evidence for cannibalism in prehistoric western Europe: From Homo antecessor to the Bronze Age. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 24 (4), 1034–1071 (2017).

Cole J. Consuming passions: Reviewing the evidence for cannibalism within the Prehistoric archaeological record [Internet]. Ass–mblage: Sheff. Grad. J. Archaeol. 9 (2006).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Carlos Díez, J., Cáceres, I. & Rosell, J. Human cannibalism in the Early Pleistocene of Europe (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 37 (3), 591–622 (1999).

Turner, C. G. I. & Turner, J. A. Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest (University of Utah Press, 1999).

Knüsel, C. & Outram, A. Fragmentation of the body: Comestibles, compost, or customary rite?. Soc. Archaeol. Funer. Remains 1 , 253 (2006).

White, T. Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346 (Princeton, 1992).

Tutt, C. M. A. Cannibalism among fossil hominids: Is there archaeological evidence?. Totem: Univ. West Ontario J Anth. 11 (1), 113–120 (2003).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. Butchery, art or rituals. J. Anthro. Archeo. Sci. 3 (3), 383–392 (2021).

Villa, P. et al. Cannibalism in the Neolithic. Science 233 (4762), 431–437 (1986).

Saladié, P. et al. Experimental butchering of a chimpanzee carcass for archaeological purposes. PLoS ONE 10 (3), e0121208 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bello, S. M., Wallduck, R., Dimitrijević, V., Živaljević, I. & Stringer, C. B. Cannibalism versus funerary defleshing and disarticulation after a period of decay: Comparisons of bone modifications from four prehistoric sites. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 161 (4), 722–743 (2016).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. & Andrews, P. When humans chew bones. J. Hum. Evol. 60 (1), 117–123 (2011).

Saladié, P., Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A., Díez, C., Martín-Rodríguez, P. & Carbonell, E. Range of bone modifications by human chewing. J. Arch. Sci. 40 , 380–397 (2013).

Schaller, G. B. The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator Prey Relations (Chicago University Press, 1972).

White, T. D. Cut marks on the Bodo cranium: A case of prehistoric defleshing. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 69 (4), 503–509 (1986).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

de Lumley, M.-A. L’homme de Tautavel. Un Homo erectus européen évolué Homo erectus tautavelensis. L’Anthropologie 119 (3), 303–348 (2015).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Díez, J. C., de Castro, J. M. B., Carbonell, E. & Arsuaga, J. L. Evidence of early cannibalism. Science 271 (5247), 277–278 (1996).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Carbonell, E. et al. Cultural cannibalism as a paleoeconomic system in the European Lower Pleistocene. Curr. Anthropol. 51 (4), 539–549 (2010).

Saladié, P. et al. Intergroup cannibalism in the European Early Pleistocene: The range expansion and imbalance of power hypotheses. J. Hum. Evol. 63 (5), 682–695 (2012).

Pickering, T. R., White, T. D. & Toth, N. Brief communication: Cutmarks on a Plio-Pleistocene hominid from Sterkfontein, South Africa. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 111 , 579–584 (2000).

Pickering, R. & Kramers, J. D. Re-appraisal of the stratigraphy and determination of new U-Pb dates for the Sterkfontein hominin site, South Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 59 (1), 70–86 (2010).

Hanon, R., Péan, S. & Prat, S. Reassessment of anthropic modifications on the Early Pleistocene hominin specimen Stw53 (Sterkfontein, South Africa). Bull. Mém Soc. Anthropol. Paris 30 , 49–58 (2018).

Clarke R. Australopithecus from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. In: The Paleobiology of Australopithecus . 2013. pp 105–23.

Pobiner B. Hominin-carnivore interactions: evidence from modern carnivore bone modification and Early Pleistocene archaeofaunas (Koobi Fora, Kenya; Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania). 2007; PhD Dissertation, Rutgers University.

Blumenschine, R. J., Marean, C. W. & Capaldo, S. D. Blind tests of inter-analyst correspondence and accuracy in the identification of cut marks, percussion marks, and carnivore tooth marks on bone surfaces. J. Archaeol. Sci. 23 , 493–507 (1996).

Pante, M. C. et al. A new high-resolution 3-D quantitative method for identifying bone surface modifications with implications for the Early Stone Age archaeological record. J. Hum. Evol. 102 , 1–11 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Pobiner acknowledges the Peter Buck Fund for Human Origins Research for funding support and the National Museums of Kenya for permission to study KNM-ER 741 and logistical support. Pante acknowledges the College of Liberal Arts and Department of Anthropology and Geography, Colorado State University for funding the purchase of the profilometer used in the study, and also Emily Orlikoff, April Tolley, and Matthew Muttart for their contributions to the creation of the actualistic database of bone surface modification models. We thank Jennifer Clark for specimen photography, Peter Nassar for assistance with human tibia anatomy and musculature, and Tom Mukhuyu and Anna K. Behrensmeyer for archival research assistance. We also thank the editor, four reviewers, and Mica Glantz for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Human Origins Program, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 20013, USA

Briana Pobiner

Department of Anthropology and Geography, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, 80523, USA

Michael Pante

Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA

Trevor Keevil

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.P. designed the project. B.P. conducted the study of the original fossil material. M.P. and T.K. conducted the analysis comparing the ancient marks on the fossil tibia to the modern marks and interpreted the results. M.P. produced the tables and figures. B.P. and M.P. wrote the manuscript. B.P., M.P., and T.K. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Briana Pobiner .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pobiner, B., Pante, M. & Keevil, T. Early Pleistocene cut marked hominin fossil from Koobi Fora, Kenya. Sci Rep 13 , 9896 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35702-7

Download citation

Received : 19 December 2022

Accepted : 22 May 2023

Published : 26 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35702-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Did our human ancestors eat each other carved-up bone offers clues.

- Lilly Tozer

Nature (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Higher Education Textbooks

- Science & Mathematics

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera, scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology Hardcover – Import, 12 June 1997

Return policy.

Tap on the category links below for the associated return window and exceptions (if any) for returns.

10 Days Returnable

You can return if you receive a damaged, defective or incorrect product.

10 Days, Refund

Returnable if you’ve received the product in a condition that is damaged, defective or different from its description on the product detail page on Amazon.in.

Refunds will be issued only if it is determined that the item was not damaged while in your possession, or is not different from what was shipped to you.

Movies, Music

Not returnable, musical instruments.

Wind instruments and items marked as non-returnable on detail page are not eligible for return.

Video Games (Accessories and Games)

You can ask for a replacement or refund if you receive a damaged, defective or incorrect product.

Mobiles (new and certified refurbished)

10 days replacement, mobile accessories.

This item is eligible for free replacement/refund, within 10 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different/wrong item delivered to you. Note: Please keep the item in its original condition, with MRP tags attached, user manual, warranty cards, and original accessories in manufacturer packaging. We may contact you to ascertain the damage or defect in the product prior to issuing refund/replacement.

Power Banks: 10 Days; Replacement only

Screen guards, screen protectors and tempered glasses are non-returnable.

Used Mobiles, Tablets

10 days refund.

Refunds applicable only if it has been determined that the item was not damaged while in your possession, or is not different from what was shipped to you.

Mobiles and Tablets with Inspect & Buy label

2 days refund, tablets (new and certified refurbished), 7 days replacement.

This item is eligible for free replacement, within 7 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged or different item delivered to you. In case of defective, product quality related issues for brands listed below, customer will be required to approach the brands’ customer service center and seek resolution. If the product is confirmed as defective by the brand then customer needs to get letter/email confirming the same and submit to Amazon customer service to seek replacement. Replacement for defective products, products with quality issues cannot be provided if the brand has not confirmed the same through a letter/email. Brands -HP, Lenovo, AMD, Intel, Seagate, Crucial

Please keep the item in its original condition, with brand outer box, MRP tags attached, user manual, warranty cards, CDs and original accessories in manufacturer packaging for a successful return pick-up. Before returning a Tablet, the device should be formatted and screen lock should be disabled.

For few products, we may schedule a technician visit to your location. On the basis of the technician's evaluation report, we will provide resolution.

This item is eligible for free replacement, within 7 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different item delivered to you.

Please keep the item in its original condition, with brand outer box, MRP tags attached, user manual, warranty cards, CDs and original accessories in manufacturer packaging for a successful return pick-up.

Used Laptops

Software products that are labeled as not returnable on the product detail pages are not eligible for returns.

For software-related technical issues or installation issues in items belonging to the Software category, please contact the brand directly.

Desktops, Monitors, Pen drives, Hard drives, Memory cards, Computer accessories, Graphic cards, CPU, Power supplies, Motherboards, Cooling devices, TV cards & Computing Components

All PC components, listed as Components under "Computers & Accessories" that are labeled as not returnable on the product detail page are not eligible for returns.

Digital Cameras, camera lenses, Headsets, Speakers, Projectors, Home Entertainment (new and certified refurbished)

Return the camera in the original condition with brand box and all the accessories Product like camera bag etc. to avoid pickup cancellation. We will not process a replacement if the pickup is cancelled owing to missing/damaged contents.

Return the speakers in the original condition in brand box to avoid pickup cancellation. We will not process a replacement if the pickup is cancelled owing to missing/ damaged box.

10 Days, Replacement

Speakers (new and certified refurbished), home entertainment.

This item is eligible for free replacement, within 10 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different/wrong item delivered to you.

Note: Please keep the item in its original condition, with MRP tags attached, user manual, warranty cards, and original accessories in manufacturer packaging for a successful return pick-up.

For TV, we may schedule a technician visit to your location and resolution will be provided based on the technician's evaluation report.

10 days Replacement only

This item is eligible for free replacement, within 10 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different/wrong item delivered to you. .

Please keep the item in its original condition, original packaging, with user manual, warranty cards, and original accessories in manufacturer packaging for a successful return pick-up.

If you report an issue with your Furniture,we may schedule a technician visit to your location. On the basis of the technician's evaluation report, we will provide resolution.

Large Appliances - Air Coolers, Air Conditioner, Refrigerator, Washing Machine, Dishwasher, Microwave

In certain cases, if you report an issue with your Air Conditioner, Refrigerator, Washing Machine or Microwave, we may schedule a technician visit to your location. On the basis of the technician's evaluation report, we'll provide a resolution.

Home and Kitchen

Grocery and gourmet, pet food, pet shampoos and conditioners, pest control and pet grooming aids, non-returnable, pet habitats and supplies, apparel and leashes, training and behavior aids, toys, aquarium supplies such as pumps, filters and lights, 7 days returnable.

All the toys item other than Vehicle and Outdoor Category are eligible for free replacement/refund, within 7 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different/wrong item delivered to you.

Vehicle and Outdoor category toys are eligible for free replacement, within 7 days of delivery, in an unlikely event of damaged, defective or different/wrong item delivered to you

Note: Please keep the item in its original condition, with outer box or case, user manual, warranty cards, and other accompaniments in manufacturer packaging for a successful return pick-up. We may contact you to ascertain the damage or defect in the product prior to issuing refund/replacement.

Sports, Fitness and Outdoors

Occupational health & safety products, personal care appliances, 7 days replacement only, health and personal care, clothing and accessories, 30 days returnable.

Lingerie, innerwear and apparel labeled as non-returnable on their product detail pages can't be returned.

Return the clothing in the original condition with the MRP and brand tag attached to the clothing to avoid pickup cancellation. We will not process a replacement or refund if the pickup is cancelled owing to missing MRP tag.

Precious Jewellery

Precious jewellery items need to be returned in the tamper free packaging that is provided in the delivery parcel. Returns in any other packaging will not be accepted.

Fashion or Imitation Jewellery, Eyewear and Watches

Return the watch in the original condition in brand box to avoid pickup cancellation. We will not process a replacement if the pickup is cancelled owing to missing/damaged contents.

Gold Coins / Gold Vedhanis / Gold Chips / Gold Bars

30 days; replacement/refund, 30 days, returnable, luggage and handbags.

Any luggage items with locks must be returned unlocked.

Car Parts and Accessories, Bike Parts and Accessories, Helmets and other Protective Gear, Vehicle Electronics

Items marked as non-returnable on detail page are not eligible for return.

Items that you no longer need must be returned in new and unopened condition with all the original packing, tags, inbox literature, warranty/ guarantee card, freebies and accessories including keys, straps and locks intact.

Fasteners, Food service equipment and supplies, Industrial Electrical, Lab and Scientific Products, Material Handling Products, Occupational Health and Safety Products, Packaging and Shipping Supplies, Professional Medical Supplies, Tapes, Adhesives and Sealants Test, Measure and Inspect items, Industrial Hardware, Industrial Power and Hand Tools.

Tyres (except car tyres), rims and oversized items (automobiles).

Car tyres are non-returnable and hence, not eligible for return.

Return pickup facility is not available for these items. You can self return these products using any courier/ postal service of your choice. Learn more about shipping cost refunds .

The return timelines for seller-fulfilled items sold on Amazon.in are equivalent to the return timelines mentioned above for items fulfilled by Amazon.

If you’ve received a seller-fulfilled product in a condition that is damaged, defective or different from its description on the product detail page on Amazon.in, returns are subject to the seller's approval of the return.

If you do not receive a response from the seller for your return request within two business days, you can submit an A-to-Z Guarantee claim. Learn more about returning seller fulfilled items.

Note : For seller fulfilled items from Books, Movies & TV Shows categories, the sellers need to be informed of the damage/ defect within 14 days of delivery.

For seller-fulfilled items from Fine Art category, the sellers need to be informed of the damage / defect within 10 days of delivery. These items are not eligible for self-return. The seller will arrange the return pick up for these items.

For seller-fulfilled items from Sports collectibles and Entertainment collectibles categories, the sellers need to be informed of the damage / defect within 10 days of delivery.

The General Return Policy is applicable for all Amazon Global Store Products (“Product”). If the Product is eligible for a refund on return, you can choose to return the Product either through courier Pickup or Self-Return**

Note: - Once the package is received at Amazon Export Sales LLC fulfillment center in the US, it takes 2 (two) business days for the refund to be processed and 2- 4 business days for the refund amount to reflect in your account. - If your return is due to an Amazon error you'll receive a full refund, else the shipping charges (onward & return) along with import fees will be deducted from your refund amount.

**For products worth more than INR 25000, we only offer Self-Return option.

2 Days, Refund

Refunds are applicable only if determined that the item was not damaged while in your possession, or is not different from what was shipped to you.

- Print length 632 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Clarendon Press

- Publication date 12 June 1997

- Dimensions 22.86 x 3.81 x 28.96 cm

- ISBN-10 0198575017

- ISBN-13 978-0198575016

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Clarendon Press (12 June 1997)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 632 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0198575017

- ISBN-13 : 978-0198575016

- Item Weight : 2 kg 340 g

- Dimensions : 22.86 x 3.81 x 28.96 cm

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 100%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from India

Top reviews from other countries.

- Press Releases

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell under Amazon Accelerator

- Protect and Build Your Brand

- Amazon Global Selling

- Become an Affiliate

- Fulfilment by Amazon

- Advertise Your Products

- Amazon Pay on Merchants

- COVID-19 and Amazon

- Your Account

- Returns Centre

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- 100% Purchase Protection

- Amazon App Download

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Interest-Based Ads

Last updated 2nd August 2024: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. As we resolve the issues resulting from this, we are also experiencing some delays to publication. We are working hard to restore services as soon as possible and apologise for the inconvenience. For further updates please visit our website https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Cambridge World Prehistory

- > The Early Prehistory of Western and Central Asia

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents Summary for Volumes 1, 2 and 3

- Volume 1 Maps

- Volume 2 Maps

- Volume 3 Maps

- About the Contributors

- VII. Western and Central Asia

- 3.1 The Early Prehistory of Western and Central Asia

- 3.2 Western and Central Asia: DNA

- 3.3 The Upper Palaeolithic and Earlier Epi-Palaeolithic of Western Asia

- 3.4 The Origins of Sedentism and Agriculture in Western Asia

- 3.5 The Levant in the Pottery Neolithic and Chalcolithic Periods

- 3.6 Settlement and Emergent Complexity in Western Syria, c. 7000–2500 bce

- 3.7 Prehistory and the Rise of Cities in Mesopotamia and Iran

- 3.8 Mesopotamia

- 3.9 Anatolia: From the Pre-Pottery Neolithic to the End of the Early Bronze Age (10,500–2000 bce )

- 3.10 Anatolia from 2000 to 550 bce

- 3.11 The Prehistory of the Caucasus: Internal Developments and External Interactions

- 3.12 Arabia

- 3.13 Central Asia before the Silk Road

- 3.14 Southern Siberia during the Bronze and Early Iron Periods

- 3.15 Western Asia after Alexander

- 3.16 Western and Central Asia: Languages

- VIII. Europe and the Mediterranean

3.1 - The Early Prehistory of Western and Central Asia

from VII. - Western and Central Asia

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2014

- 3.9 Anatolia: From the Pre-Pottery Neolithic to the End of the Early Bronze Age (10,500–2000 bce)

Introduction: The Levantine Corridor

The region that is the focus of this chapter is but a small stretch of land enjoying Mediterranean climate, located between the Mediterranean Sea to the west and one of the harshest deserts on earth to the east. The Levantine Corridor (Goren-Inbar & Speth 2004), despite its small size, has been subject to one of the most intensive archaeological efforts anywhere. Here some of the world’s most important prehistoric sites have been discovered during almost one hundred years of excavation. Together with new sites, they remain the source for many of the cutting-edge questions and debates in palaeoanthropology today. The story of the Levant in early prehistory is first of all the story of a corridor, the main pathway leading out of Africa taken by continuous waves of human groups reaching out for new territory in Eurasia. Some of the very early evidence for human presence outside of Africa is succeeded in the region by indications of subsequent Lower Palaeolithic dispersals, followed by the earliest movement of anatomically modern humans out of Africa during the Middle Palaeolithic.

Our current focus on the Levantine Corridor, to the exclusion of the remainder of Asia, is due to the fact that Central Asian data are almost nonexistent to date. R. Dennell provides the few data from Central Asia in his recently published book (Dennell 2009), and the reader is advised to consult this monumental work. Yet even this scholar, who has focused considerable attention on Asia, wrote: “The Palaeolithic record of the west region, covering an area c. 16 times larger than Britain, is largely unknown, and mostly comprises surface artifact collections that are not datable” (Dennell 2009: 325). Central Asia is clearly a key region for the discussion of the most significant questions in early prehistoric archaeology today. Currently, political and geographical difficulties stand in the way of scholars working in these vast regions, but exciting discoveries will surely emerge with the advance of research in the future.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- The Early Prehistory of Western and Central Asia

- By Gonen Sharon , The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Edited by Colin Renfrew , University of Cambridge , Paul Bahn

- Book: The Cambridge World Prehistory

- Online publication: 05 August 2014

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139017831.086

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- Sign in

- My Account

- Basket

Items related to Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5: Plio-Pleistocene...

Koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology - hardcover.

This specific ISBN edition is currently not available.

- About this title

- About this edition

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- Publisher Clarendon Press

- Publication date 1997

- ISBN 10 0198575017

- ISBN 13 9780198575016

- Binding Hardcover

- Number of pages 632

- Editor Isaac Glynn Ll. , Isaac Barbara

Convert currency

Shipping: US$ 12.14 From Italy to U.S.A.

Add to basket

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Koobi fora research project: volume 5: plio-pleistocene archaeology (eng).

Quantity: Over 20 available

Seller: Brook Bookstore On Demand , Napoli, NA, Italy

Seller Rating:

Condition: new. Questo � un articolo print on demand. Seller Inventory # 1198099ae3491fe563dba27c43200649

Contact seller

Koobi Fora Research Project : Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology

Quantity: 5 available

Seller: GreatBookPrices , Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 67033-n

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK , Castle Donington, DERBY, United Kingdom

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5

Seller: moluna , Greven, Germany

Einband - fest (Hardcover). Condition: New. Dieser Artikel ist ein Print on Demand Artikel und wird nach Ihrer Bestellung fuer Sie gedruckt. This volume, the fifth in the important Koobi Fora series on human origins, reports archaeological finds from excavations at East Turkana in northern Kenya. Volume 5 concentrates on the evidence from the period between 1.9 and 0.7 million years ago for reco. Seller Inventory # 594410579

- Arts & Crafts

- DIY & Tools

- Electronics

- Health & Beauty

- Kitchen & Appliances

- Movies & TV

- Stationery & Office

Koobi Fora Research Project: Volume 5 - Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology (Hardcover)

Or split into 4x interest-free payments of 25% on orders over R50 Learn more

Product Description

Customer reviews, no reviews or ratings yet - be the first to create one, product details.

| Clarendon Press | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Koobi Fora Research Project | |

| June 1997 | |

| Supplier out of stock. If you add this item to your wish list we will let you know when it becomes available. | |

| , | |

| 314 x 228 x 37mm (L x W x T) | |

| Hardcover | |

| 632 | |

| 978-0-19-857501-6 | |

| 9780198575016 | |

| 0-19-857501-7 |

Be the first to know about our latest deals & promos! Subscribe Now

- New Customer

- Competitions

- Subscriptions

- Gift Vouchers

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Contact Details

COPYRIGHT © 2024 AFRICA ONLINE RETAIL (PTY) LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Khutaza Park, 27 Bell Crescent, Westlake Business Park. PO Box 30836, Tokai, 7966, South Africa. [email protected] All prices displayed are subject to fluctuations and stock availability as outlined in our Terms & Conditions

The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 24 December 2014

- pp 2145–2165

- Cite this reference work entry

- Friedemann Schrenk 3 ,

- Ottmar Kullmer 3 &

- Timothy Bromage 4

6249 Accesses

3 Citations

8 Altmetric