Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.5: Goodwill Messages and Recommendations

Learning objectives.

2. ENL1813 Course Learning Requirement 1 : Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences. (A1, B1, H1, M1, S1, T1)

a. Format and write short documents such as routine correspondence (T1.4)

Share the love! Rather than an optional cherry on top, goodwill messages are as essential to healthy professional relationships as they are in personal ones. Thank-you, congratulatory, and sympathy notes add an important, feel-good human touch in a world that continues to embrace technology that isolates people while being marketed as a means of connecting them. The goodwill that such messages promote makes both sender and receiver feel better about each other and themselves compared with where they’d be if the messages weren’t sent at all. In putting smiles on faces, such notes are effective especially because many people don’t send them—either because they feel that they’re too difficult to write or because it doesn’t even occur to them to do so. Since praise for some can be harder to think of and write than criticism, a brief guide on how to do it right may be of help here.

Goodwill Messages and Recommendations Topics

8.5.1: The 5 S’s of Goodwill Messages

8.5.2: thank-you notes, 8.5.3: congratulatory messages, 8.5.4: expressions of sympathy, 8.5.5: replying to goodwill messages, 8.5.6: recommendation messages and reference letters.

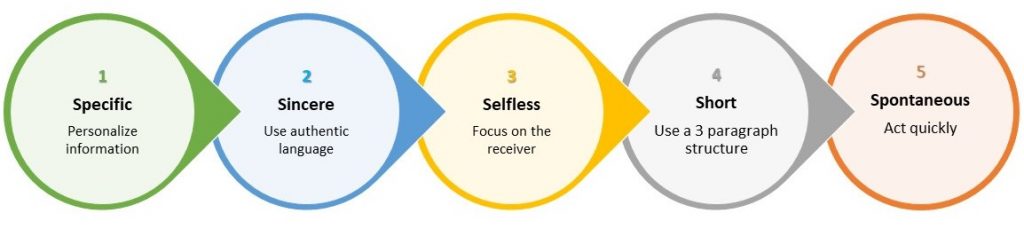

Whether you’re writing thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy, follow the “5 S” principles of effective goodwill messages:

- Specific: Crafting the message around specific references to the situation that it addresses will steer such messages away from the impression that they were boilerplate template statements that you plagiarized.

- Sincere: A goodwill message will come off as genuine if it’s near to what you would say to the recipient in person. Avoid cliché Hallmark-card expressions and excessive formality such as It is with a heavy heart that I extend my heartfelt condolences to you in these sad times.

- Selfless: Refer only to the person or people involved rather than yourself. The spotlight is on them, not you. Avoid telling stories about how you experienced something similar in an attempt to show how you relate.

- Short: Full three-part messages and three-part paragraphs are unnecessary in thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy, but appropriate in recommendations that require detail. Don’t make the short length of the message deter you from setting aside time to draft it.

- Spontaneous: Move quickly to write your message so that it follows closely on the news that prompted it. A message that’s passed its “best before” date will appear stale to the recipient and make you look like you can’t manage your time effectively (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 144).

Return to the Goodwill Messages and Recommendations Topics Menu

In the world of business, not all transactions involve money. People do favours for each other, and acknowledging those with thank-you notes is essential for keeping relations positive. Such messages can be short and simple, as well as quick and easy to write, which means not sending them when someone does something nice to you appears ungrateful, rude, and inconsiderate. Someone who did you a favour might not bother to do so again if it goes unthanked. Such notes are ideal for situations such as those listed in Table 8.5.2:

Table 8.5.2: Common Reasons for Expressing Thanks in Professional Situations

In most situations, email or text is an appropriate channel for sending thank-you messages. As we shall see in §10.3.3 below, sending a thank-you note within 24 hours of interviewing for a job is not just extra-thoughtful but close to being an expected formality. To stand out from other candidates, hand-writing a thank-you card in such situations might even be a good idea.

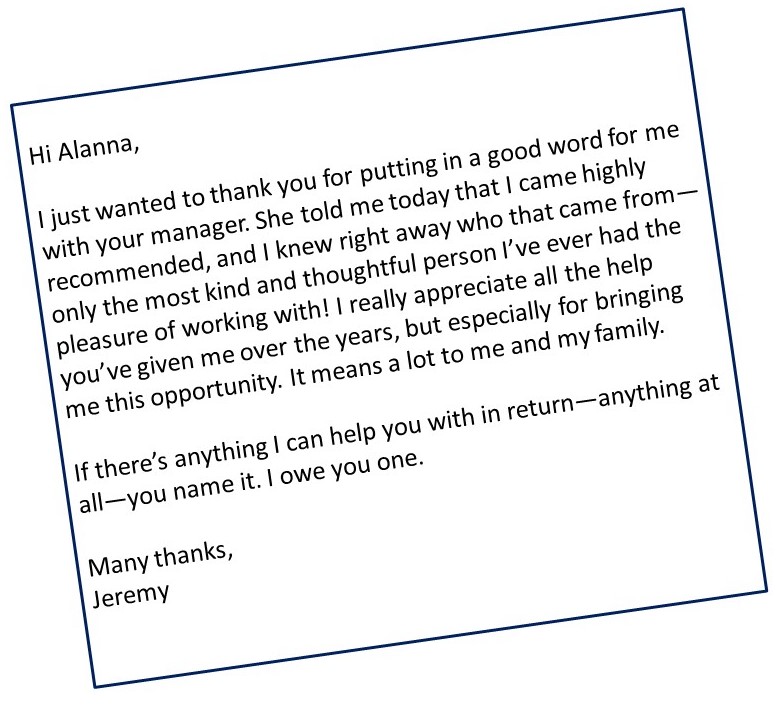

Following the 5 S’s of goodwill messages given above in §8.5.1 , a typical thank-you email message for a favour might look like the following:

I just wanted to thank you for putting in a good word for me with your manager. She told me today that I came highly recommended, and I knew right away who that came from—only the most kind and thoughtful person I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with! I really appreciate all the help you’ve given me over the years, but especially for bringing me this opportunity. It means a lot to me and my family.

If there’s anything I can help you with in return—anything at all—you name it. I owe you one.

Many thanks,

Notice that this message is short, specific to the situation that prompted it, sincere, relatively selfless, and spontaneously sent the day of the incident that prompted it. It would certainly bring a smile both to the recipient and sender, strengthening their professional bond.

Celebrating the successes of your professional peers shows class and tact. It’s good karma that will come back around as long as you keep putting out positive energy. Again, the 5 S’s apply in congratulatory messages, especially selflessness. Such messages are all about the person you’re congratulating. You could say, for instance, I really admire how you handled yourself with such grace and poise under such trying circumstances in the field today.

Few situations require such sincerity and care with words as expressions of sympathy. Misfortune comes upon us all, and tough times are just a little more tolerable with the support of our friends, family, and community—including those we work with. When the loved-one of a close associate dies, for instance, expressing sympathy for their loss is customary, often with a card signed by everyone in the workplace who knows the bereaved. You can’t put an email on the mantle like you can a collection of cards from people showing they care.

What do you say in such situations? A simple I’m so sorry for your loss , despite being a stock expression, is better than letting the standard Hallmark card’s words speak for you (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 147). In some situations, laughter—or at least a chuckle—may be the best medicine, in which case something along the lines of Emily McDowell’s witty Empathy Cards would be more appropriate. McDowell’s There Is No Good Card for This: What to Say and Do When Life Is Scary, Awful, and Unfair to People You Love (2016) collaboration with empathy expert Kelsey Crowe, PhD, provides excellent advice. Showing empathy by saying that you know how hard it can be is helpful as long as you don’t go into any detail about their loss or yours. Remember, these messages should be selfless, and being too specific can be a little dangerous here if it produces traumatic imagery. Offering your condolences in the most respectful, sensitive manner possible is just the right thing to do.

It wouldn’t go over well if someone thanked you for your help and you just stared at them silently. The normal reaction is to simply say You’re welcome! Replying to goodwill messages is therefore as essential as writing them. Such replies must be even shorter than the messages that they respond to. If someone says a few nice things about you in an email about something else, always acknowledge the goodwill by saying briefly “Thank you very much for the kind words” somewhere in your response. Without making a mockery of the situation by thanking a thank-you or shrugging off a compliment, returning the love with nicely worded and sincere gratitude is the right thing to do (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 147).

Recommendation messages are vital to getting hired, nominated for awards, and membership into organizations. They offer trusted-source testimonials about a candidate’s worthiness for whatever they’re applying to. Like the résumé and cover letter they corroborate, their job is to persuade an employer or selection committee to accept the person in question. To be convincing, recommendation and reference letters must be the following:

- Specific: Recommendation and reference letters must focus entirely on the candidate with details such as examples of accomplishments, including dates or date ranges in months and years. A generic recommendation plagiarized from the internet is worse than useless because it makes the applicant look like they’re unworthy of a properly targeted letter.

- True: Exaggerations and outright lies will hurt the candidate when found out (e.g., in response to job interview questions and background checks). They will spoil the chances of any future applicants who use recommendations from the same untrustworthy source if the employer sees that source cross their desk again.

- Objective: An endorsement from a friend or family member will be seen as subjective to the point of lacking any credibility. Recommendations must therefore come from a business owner, employer, manager, or supervisor who can offer an unbiassed assessment.

Not all employers require recommendation letters of their job candidates, so only bother seeking a recommendation letter when it’s asked for. Opinions are divided on whether such documents are actually useful, since they are almost always “glowing” because they tend not to say anything negative about the applicant despite the expectation that they be objective. Some employers—especially in larger organizations—are instructed not to write recommendation letters (or are limited in what they can say if called for a reference) because they leave the company that writes them open to lawsuits from both the applicant and recipient company if things don’t work out.

On the other hand, recommendation letters provide potential employers with valuable validation of the job applicant’s claims, so it’s worth knowing how to ask for one and what to ask for if they’re required as part of a hiring process. Even if it may be some years before you’re in a position to write such letters yourself, knowing what information to provide the person who agrees to write you a recommendation is useful to you now. Indeed, since most managers are busy people, they might even ask you to draft it for them so they can plug it into a company letterhead template, sign it, and send it along. If so, then you could ghost-write it using the following section as your guide.

8.5.6.1: Recommendation Letter Organization

A recommendation letter is a direct-approach message framed by a modified-block formal letter using company letterhead (see §7.1 above). The most effective letters are targeted to an employer for a specific job application, though it’s not uncommon to request a “To Prospective Employers” recommendation letter without a recipient address to be distributed as part of any job application. In any case, the following represents the standard expectations employers have for recommendation letter content and organization:

- Identify the applicant by name , the position sought, and the confidential nature of the letter—e.g., This confidential letter is written at the request of Elizabeth Barrie in support of her application for the position of Legal Assistant at Bailey & Garrick Law .

- Clarify the writer’s relationship to the applicant and the length of its duration—e.g., For three years I have been Ms. Barrie’s supervisor at Stanton & Sons Legal Counsel and can therefore say with confidence that she would be a valuable addition to your firm .

- Identify the job applicant’s previous duties—e.g., Ms. Barrie began working for us as a part-time legal research assistant during her studies in the Law Clerk program at Algonquin College. She began with mainly clerical duties such as preparing official legal documents and archiving our firm’s records.

- Give examples of the applicant’s accomplishments and professional attributes. Wherever achievements are quantifiable, include numbers—e.g., After initiating and executing a records digitization project involving over 12,000 files, Ms. Barrie conducted more extensive legal research activities. Her superior organizational skills and close attention to detail made her a highly dependable assistant that our six associate lawyers and two partners relied on heavily to conduct research tasks. Her conscientiousness meant that she required very little direction and oversight when performing her duties.

- Compare the applicant to others—e.g., Without a doubt, Ms. Barrie has been our most productive and trusted legal assistant in the past decade.

- Summarize and emphatically state the endorsement —e.g., Any law firm would be lucky to have such a consummate professional as Ms. Barrie in their employ. I highly recommend her without reservation. If you would like to discuss this endorsement further, please contact me at the number above.

Because honesty is of paramount importance in a recommendation letter, including specific evidence of performance flaws wouldn’t be out of place, especially if used in a narrative of promotion and improvement. Including criticism of the candidate helps the credibility of the endorsement because it makes it more believable. After all, no one is perfect. Criticism resolved by a narrative of improvement, however, strengthens the endorsement even further. Consider, for instance, how good this looks:

Ms. Barrie tended to sacrifice quantity of completed research tasks to quality, completing perhaps 17 out of an expected 25 assignments per day. However, she increased her speed and efficiency such that, in her last year with us, she was completing more tasks with higher accuracy than any other assistant we’ve ever had.

Of course, this general frame for recommendations can be adapted and either extended or trimmed for channels other than letters. LinkedIn, for instance, allows users to endorse each other, but the small window in which the endorsement appears favours a smaller wordcount than the typical letter format. In that case, one paragraph of highlights and a few details is more appropriate than several paragraphs, especially if you can get several such endorsements from a variety of network contacts.

8.5.6.2: How to Request a Recommendation Letter

When a recommendation is necessary, be sure to ask a manager or supervisor who’s known you for two years or more if they can provide you with a strong reference. If they can’t—because they’re prohibited from doing so by company policy or they honestly don’t think you’re worthy of an endorsement—they’ll probably just recommend that you find and ask someone who would. Don’t be shy about asking for one, though. If they aren’t directed otherwise, management understands that writing such messages is part of their job. They got to where they are on the strength of references and recommendations from their previous employers, and the “pay-it-forward” system compels them to provide the same for the people under—people like you. That way, you too can move up in your career.

Knowing that every employment situation you’re in provides an opportunity for a reference when it’s time to move on, you should always do your best so that you can get a strong reference out of it. Even in jobs that you dislike or that bore you, strive to exemplify the advice on employer-impressing professional behaviour given throughout §10.2 below. Consider also that if a résumé lists references at the end but omits them for certain job experiences, a hiring manager will wonder why you weren’t able to get a reference for that job. It certainly could have been due to company policy prohibiting managers from providing references for legal reasons or conflict with management that was entirely their fault (not all managers are decent human beings as we shall discuss in §11.1.3.3 below); without the full picture, however, the omission opens the door to doubts about the candidate.

Key Takeaway

2. Write a thank-you note to the partner who wrote you an endorsement in LinkedIn following the advice in §8.5.2 and §8.5.5 above.

Guffey, M.E., Loewy, D., & Almonte, R. (2016). Essentials of business communication (8th Can. ed.). Toronto: Nelson.

Communication at Work Copyright © 2019 by Jordan Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Unit 28: Goodwill Messages and Recommendations

Learning objectives.

- understand the different types of goodwill messages

- write different types of goodwill messages

- know the 5 S’s of goodwill messages

Introduction

Share the love! Goodwill messages are as essential to healthy professional relationships as they are in personal ones. Thank-you, congratulatory, and sympathy notes add an important, feel-good human touch in a world that continues to embrace technology that isolates people while being marketed as a means of connecting them. The goodwill that such messages promote makes both sender and receiver feel better about each other and themselves compared with where they’d be if the messages weren’t sent at all. In putting smiles on faces, such notes are effective especially because many people don’t send them—either because they feel that they’re too difficult to write or because it doesn’t even occur to them to do so. Since praise for some can be harder to think of and write than criticism, a brief guide on how to do it right may be of help here.

The 5 S’s of Goodwill Messages

Whether you’re writing thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy, follow the “5 S” principles of effective goodwill messages:

- Specific: Crafting the message around specific references to the situation that it addresses will steer such messages away from the impression that they were boilerplate template statements that you plagiarized.

- Sincere: A goodwill message will come off as genuine if it’s near to what you would say to the recipient in person. Avoid cliché Hallmark-card expressions and excessive formality such as It is with a heavy heart that I extend my heartfelt condolences to you in these sad times.

- Selfless: Refer only to the person or people involved rather than yourself. The spotlight is on them, not you. Avoid telling stories about how you experienced something similar in an attempt to show how you relate.

- Short: Full three-part messages and three-part paragraphs are unnecessary in thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy, but appropriate in recommendations that require detail. Don’t make the short length of the message deter you from setting aside time to draft it.

- Spontaneous: Move quickly to write your message so that it follows closely on the news that prompted it. A message that’s passed its “best before” date will appear stale to the recipient and make you look like you can’t manage your time effectively (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 144).

Types of Goodwill Messages

Thank-you Notes

In the world of business, not all transactions involve money. People do favours for each other, and acknowledging those with thank-you notes is essential for keeping relations positive. Such messages can be short and simple, as well as quick and easy to write, which means not sending them when someone does something nice for you appears ungrateful, rude, and inconsiderate. Someone who did you a favour might not bother to do so again if it goes unthanked. Such notes are ideal for situations such as those listed in Table 28.1:

Table 28.1: Common Reasons for Expressing Thanks in Professional Situations

In most situations, email or text is an appropriate channel for sending thank-you messages. In fact, sending a thank-you note within 24 hours of interviewing for a job is not just extra-thoughtful but close to being an expected formality. To stand out from other candidates, hand-writing a thank-you card in such situations might even be a good idea.

Notice that this message is short, specific to the situation that prompted it, sincere, relatively selfless, and spontaneously sent the day of the incident that prompted it. It would certainly bring a smile both to the recipient and sender, strengthening their professional bond.

Congratulatory Messages

Celebrating the successes of your professional peers shows class and tact. It’s good karma that will come back around as long as you keep putting out positive energy. Again, the 5 S’s apply in congratulatory messages, especially selflessness. Such messages are all about the person you’re congratulating. You could say, for instance, I really admire how you handled yourself with such grace and poise under such trying circumstances in the field today.

Expressions of Sympathy

Few situations require such sincerity and care with words as expressions of sympathy. Misfortune comes upon us all, and tough times are just a little more tolerable with the support of our friends, family, and community—including those we work with. When the loved-one of a close associate dies, for instance, expressing sympathy for their loss is customary, often with a card signed by everyone in the workplace who knows the bereaved. You can’t put an email on the mantle like you can a collection of cards from people showing they care.

What do you say in such situations? A simple I’m so sorry for your loss , despite being a stock expression, is better than letting the standard Hallmark card’s words speak for you (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 147). In some situations, laughter—or at least a chuckle—may be the best medicine, in which case something along the lines of Emily McDowell’s witty Empathy Cards would be more appropriate. McDowell’s There Is No Good Card for This: What to Say and Do When Life Is Scary, Awful, and Unfair to People You Love (2016) in collaboration with empathy expert Kelsey Crowe, PhD, provides excellent advice. Showing empathy by saying that you know how hard it can be is helpful as long as you don’t go into any detail about their loss or yours. Remember, these messages should be selfless, and being too specific can be a little dangerous here if it produces traumatic imagery. Offering your condolences in the most respectful, sensitive manner possible is just the right thing to do.

Replying to Goodwill Messages

It wouldn’t go over well if someone thanked you for your help and you just stared at them silently. The normal reaction is to simply say You’re welcome! Replying to goodwill messages is therefore as essential as writing them. Such replies must be even shorter than the messages that they respond to. If someone says a few nice things about you in an email about something else, always acknowledge the goodwill by saying briefly “Thank you very much for the kind words” somewhere in your response. Without making a mockery of the situation by thanking a thank-you or shrugging off a compliment, returning the love with nicely worded and sincere gratitude is the right thing to do (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 147).

Recommendation Messages and Reference Letters

Recommendation messages are vital to getting hired, nominated for awards, and membership into organizations. They offer trusted-source testimonials about a candidate’s worthiness for whatever they’re applying to. Like the résumé and cover letter they corroborate, their job is to persuade an employer or selection committee to accept the person in question. To be convincing, recommendation and reference letters must be the following:

- Specific: Recommendation and reference letters must focus entirely on the candidate with details such as examples of accomplishments, including dates or date ranges in months and years. A generic recommendation plagiarized from the internet is worse than useless because it makes the applicant look like they’re unworthy of a properly targeted letter.

- True: Exaggerations and outright lies will hurt the candidate when found out (e.g., in response to job interview questions and background checks). They will spoil the chances of any future applicants who use recommendations from the same untrustworthy source if the employer sees that source cross their desk again.

- Objective: An endorsement from a friend or family member will be seen as subjective to the point of lacking any credibility. Recommendations must therefore come from a business owner, employer, manager, or supervisor who can offer an unbiassed assessment.

Not all employers require recommendation letters of their job candidates, so only bother seeking a recommendation letter when it’s asked for. Opinions are divided on whether such documents are actually useful, since they are almost always “glowing” because they tend not to say anything negative about the applicant despite the expectation that they be objective. Some employers—especially in larger organizations—are instructed not to write recommendation letters (or are limited in what they can say if called for a reference) because they leave the company that writes them open to lawsuits from both the applicant and recipient company if things don’t work out.

On the other hand, recommendation letters provide potential employers with valuable validation of the job applicant’s claims, so it’s worth knowing how to ask for one and what to ask for if they’re required as part of a hiring process. Even if it may be some years before you’re in a position to write such letters yourself, knowing what information to provide the person who agrees to write you a recommendation is useful to you now. Indeed, since most managers are busy people, they might even ask you to draft it for them so they can plug it into a company letterhead template, sign it, and send it along. If so, then you could ghost-write it using the following section as your guide.

Let’s view how to write letters of recommendations before looking at the individual sections of the letter.

Recommendation Letter Organization

A recommendation letter is a direct-approach message framed by a modified-block formal letter using company letterhead (see unit 20 ). The most effective letters are targeted to an employer for a specific job application, though it’s not uncommon to request a “To Prospective Employers” recommendation letter without a recipient address to be distributed as part of any job application. In any case, the following represents the standard expectations employers have for recommendation letter content and organization:

- Identify the applicant by name , the position sought, and the confidential nature of the letter—e.g., This confidential letter is written at the request of Elizabeth Barrie in support of her application for the position of Legal Assistant at Bailey & Garrick Law.

- Clarify the writer’s relationship to the applicant and the length of its duration—e.g., For three years I have been Ms. Barrie’s supervisor at Stanton & Sons Legal Counsel and can therefore say with confidence that she would be a valuable addition to your firm.

- Identify the job applicant’s previous duties—e.g., Ms. Barrie began working for us as a part-time legal research assistant during her studies in the Law Clerk program at Algonquin College. She began with mainly clerical duties such as preparing official legal documents and archiving our firm’s records.

- Give examples of the applicant’s accomplishments and professional attributes. Wherever achievements are quantifiable, include numbers—e.g., After initiating and executing a records digitization project involving over 12,000 files, Ms. Barrie conducted more extensive legal research activities. Her superior organizational skills and close attention to detail made her a highly dependable assistant that our six associate lawyers and two partners relied on heavily to conduct research tasks. Her conscientiousness meant that she required very little direction and oversight when performing her duties.

- Compare the applicant to others—e.g., Without a doubt, Ms. Barrie has been our most productive and trusted legal assistant in the past decade.

- Summarize and emphatically state the endorsement —e.g., Any law firm would be lucky to have such a consummate professional as Ms. Barrie in their employ. I highly recommend her without reservation. If you would like to discuss this endorsement further, please contact me at the number above.

:strip_icc():format(webp)/personal-recommendation-letter-samples-2062963-FINAL-715b3f885476415c81c3c2cd49fac712.png)

Because honesty is of paramount importance in a recommendation letter, including specific evidence of performance flaws wouldn’t be out of place, especially if used in a narrative of promotion and improvement. Including criticism of the candidate helps the credibility of the endorsement because it makes it more believable. After all, no one is perfect. Criticism resolved by a narrative of improvement, however, strengthens the endorsement even further. Consider, for instance, how good this looks:

Ms. Barrie tended to sacrifice quantity of completed research tasks to quality, completing perhaps 17 out of an expected 25 assignments per day. However, she increased her speed and efficiency such that, in her last year with us, she was completing more tasks with higher accuracy than any other assistant we’ve ever had.

Of course, this general frame for recommendations can be adapted and either extended or trimmed for channels other than letters. LinkedIn, for instance, allows users to endorse each other, but the small window in which the endorsement appears favours a smaller wordcount than the typical letter format. In that case, one paragraph of highlights and a few details is more appropriate than several paragraphs, especially if you can get several such endorsements from a variety of network contacts.

How to Request a Recommendation Letter

When a recommendation is necessary, be sure to ask a manager or supervisor who’s known you for two years or more if they can provide you with a strong reference. If they can’t—because they’re prohibited from doing so by company policy or they honestly don’t think you’re worthy of an endorsement—they’ll probably just recommend that you find and ask someone who would. Don’t be shy about asking for one, though. If they aren’t directed otherwise, management understands that writing such messages is part of their job. They got to where they are on the strength of references and recommendations from their previous employers, and the “pay-it-forward” system compels them to provide the same for the people under—people like you. That way, you too can move up in your career.

Knowing that every employment situation you’re in provides an opportunity for a reference when it’s time to move on, you should always do your best so that you can get a strong reference out of it. Consider also that if a résumé lists references at the end but omits them for certain job experiences, a hiring manager will wonder why you weren’t able to get a reference for that job. It certainly could have been due to company policy prohibiting managers from providing references for legal reasons or conflict with management that was entirely their fault (not all managers are decent human beings as we shall discuss in unit 29 ); without the full picture, however, the omission opens the door to doubts about the candidate.

Key Takeaway

Guffey, M.E., Loewy, D., & Almonte, R. (2016). Essentials of business communication (8th Can. ed.). Toronto: Nelson.

LinkedIn Learning. (2014). Productivity tutorial: Writing a letter of recommendation | lynda.com [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OB882puILhM

Price, M. (2019). Tips for writing a personal recommendation letter. The Balance. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/personal-recommendation-letter-samples-2062963

Communication at Work Copyright © 2019 by Jordan Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

18.2 Special-Occasion Speeches

Learning objectives.

- Identify the different types of ceremonial speaking.

- Describe the different types of inspirational speaking.

M+MD – Birthday Speech – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Many entertaining speeches fall under the category of special-occasion speeches. All the speeches in this category are given to mark the significance of particular events. Common events include weddings, bar mitzvahs, awards ceremonies, funerals, and political events. In each of these different occasions, speakers are asked to deliver speeches relating to the event. For purposes of simplicity, we’ve broken special-occasion speeches into two groups: ceremonial speaking and inspirational speaking.

Ceremonial Speaking

Ceremonial speeches are speeches given during a ceremony or a ritual marked by observance of formality or etiquette. These ceremonies tend to be very special for people, so it shouldn’t be surprising that they are opportunities for speech making. Let’s examine each of the eight types of ceremonial speaking: introductions, presentations, acceptances, dedications, toasts, roasts, eulogies, and farewells.

Speeches of Introduction

The first type of speech is called the speech of introduction , which is a minispeech given by the host of a ceremony that introduces another speaker and his or her speech. Few things are worse than when the introducer or a speaker stands up and says, “This is Joe Smith, he’s going to talk about stress.” While we did learn the speaker’s name and the topic, the introduction falls flat. Audiences won’t be the least bit excited about listening to Joe’s speech.

Just like any other speech, a speech of introduction should be a complete speech and have a clear introduction, body, and conclusion—and you should do it all in under two minutes. This brings up another “few things are worse” scenario: an introductory speaker who rambles on for too long or who talks about himself or herself instead of focusing on the person being introduced.

For an introduction, think of a hook that will make your audience interested in the upcoming speaker. Did you read a news article related to the speaker’s topic? Have you been impressed by a presentation you’ve heard the speaker give in the past? You need to find something that can grab the audience’s attention and make them excited about hearing the main speaker.

The body of your introductory speech should be devoted to telling the audience about the speaker’s topic, why the speaker is qualified, and why the audience should listen (notice we now have our three body points). First, tell your audience in general terms about the overarching topic of the speech. Most of the time as an introducer, you’ll only have a speech title and maybe a paragraph of information to help guide this part of your speech. That’s all right. You don’t need to know all the ins and outs of the main speaker’s speech; you just need to know enough to whet the audience’s appetite. Next, you need to tell the audience why the speaker is a credible speaker on the topic. Has the speaker written books or articles on the subject? Has the speaker had special life events that make him or her qualified? Lastly, you need to briefly explain to the audience why they should care about the upcoming speech.

The final part of a good introduction is the conclusion, which is generally designed to welcome the speaker to the lectern. Many introducers will conclude by saying something like, “I am looking forward to hearing how Joe Smith’s advice and wisdom can help all of us today, so please join me in welcoming Mr. Joe Smith.” We’ve known some presenters who will even add a notation to their notes to “start clapping” and “shake speakers hand” or “give speaker a hug” depending on the circumstances of the speech.

Now that we’ve walked through the basic parts of an introductory speech, let’s see one outlined:

Specific Purpose: To entertain the audience while preparing them for Janice Wright’s speech on rituals.

Introduction: Mention some common rituals people in the United States engage in (Christmas, sporting events, legal proceedings).

Main Points:

- Explain that the topic was selected because understanding how cultures use ritual is an important part of understanding what it means to be human.

- Janice Wright is a cultural anthropologist who studies the impact that everyday rituals have on communities.

- All of us engage in rituals, and we often don’t take the time to determine how these rituals were started and how they impact our daily routines.

Conclusion: I had the opportunity to listen to Dr. Wright at the regional conference in Springfield last month, and I am excited that I get to share her with all of you tonight. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Wright (start clapping, shake speaker’s hand, exit stage).

Speeches of Presentation

The second type of common ceremonial speech is the speech of presentation . A speech of presentation is a brief speech given to accompany a prize or honor. Speeches of presentation can be as simple as saying, “This year’s recipient of the Schuman Public Speaking prize is Wilhelmina Jeffers,” or could last up to five minutes as the speaker explains why the honoree was chosen for the award.

When preparing a speech of presentation, it’s always important to ask how long the speech should be. Once you know the time limit, then you can set out to create the speech itself. First, you should explain what the award or honor is and why the presentation is important. Second, you can explain what the recipient has accomplished in order for the award to be bestowed. Did the person win a race? Did the person write an important piece of literature? Did the person mediate conflict? Whatever the recipient has done, you need to clearly highlight his or her work. Lastly, if the race or competition was conducted in a public forum and numerous people didn’t win, you may want to recognize those people for their efforts as well. While you don’t want to steal the show away from winner (as Kanye West did to Taylor Swift during the 2009 MTV Music Video Awards, for example http://www.mtv.com/videos/misc/435995/taylor-swift-wins-best-female-video.jhtml#id=1620605 ), you may want to highlight the work of the other competitors or nominees.

Speeches of Acceptance

The complement to a speech of presentation is the speech of acceptance . The speech of acceptance is a speech given by the recipient of a prize or honor. For example, in the above video clip from the 2009 MTV Music Video Awards, Taylor Swift starts by expressing her appreciation, gets interrupted by Kanye West, and ends by saying, “I would like to thank the fans and MTV, thank you.” While obviously not a traditional acceptance speech because of the interruption, she did manage to get in the important parts.

There are three typical components of a speech of acceptance: thank the givers of the award or honor, thank those who helped you achieve your goal, and put the award or honor into perspective. First, you want to thank the people who have given you the award or honor and possibly those who voted for you. We see this done every year during the Oscars, “First, I’d like to thank the academy and all the academy voters.” Second, you want to give credit to those who helped you achieve the award or honor. No person accomplishes things in life on his or her own. We all have families and friends and colleagues who support us and help us achieve what we do in life, and a speech of acceptance is a great time to graciously recognize those individuals. Lastly, put the award in perspective. Tell the people listening to your speech why the award is meaningful to you.

Speeches of Dedication

The fourth ceremonial speech is the speech of dedication . A speech of dedication is delivered when a new store opens, a building is named after someone, a plaque is placed on a wall, a new library is completed, and so on. These speeches are designed to highlight the importance of the project and possibly those to whom the project has been dedicated. Maybe your great-uncle has died and left your college tons of money, so the college has decided to rename one of the dorms after your great-uncle. In this case, you may be asked to speak at the dedication.

When preparing the speech of dedication, start by explaining how you are involved in the dedication. If the person to whom the dedication is being made is a relative, tell the audience that the building is being named after your great-uncle who bestowed a gift to his alma mater. Second, you want to explain what is being dedicated. If the dedication is a new building or a preexisting building, you want to explain what is being dedicated and the importance of the structure. You should then explain who was involved in the project. If the project is a new structure, talk about the people who built the structure or designed it. If the project is a preexisting structure, talk about the people who put together and decided on the dedication. Lastly, explain why the structure is important for the community where it’s located. If the dedication is for a new store, talk about how the store will bring in new jobs and new shopping opportunities. If the dedication is for a new wing of a hospital, talk about how patients will be served and the advances in medicine the new wing will provide the community.

At one time or another, almost everyone is going to be asked to deliver a toast . A toast is a speech designed to congratulate, appreciate, or remember. First, toasts can be delivered for the purpose of congratulating someone for an honor, a new job, or getting married. You can also toast someone to show your appreciation for something they’ve done. Lastly, we toast people to remember them and what they have accomplished.

When preparing a toast, the first goal is always to keep your remarks brief. Toasts are generally given during the middle of some kind of festivities (e.g., wedding, retirement party, farewell party), and you don’t want your toast to take away from those festivities for too long. Second, the goal of a toast is to focus attention on the person or persons being toasted—not on the speaker. As such, while you are speaking you need to focus your attention to the people being toasted, both by physically looking at them and by keeping your message about them. You should also avoid any inside jokes between you and the people being toasted because toasts are public and should be accessible for everyone who hears them. To conclude a toast, simply say something like, “Please join me in recognizing Joan for her achievement” and lift your glass. When you lift your glass, this will signal to others to do the same and then you can all take a drink, which is the end of your speech.

The roast speech is a very interesting and peculiar speech because it is designed to both praise and good-naturedly insult a person being honored. Generally, roasts are given at the conclusion of a banquet in honor of someone’s life achievements. The television station Comedy Central has been conducting roasts of various celebrities for a few years.

In this clip, watch as Stephen Colbert, television host of The Colbert Report , roasts President George W. Bush.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BSE_saVX_2A

Let’s pick this short clip apart. You’ll notice that the humor doesn’t pull any punches. The goal of the roast is to both praise and insult in a good-natured manner. You’ll also see that the roaster, in this case Stephen Colbert, is standing behind a lectern while the roastee, President George W. Bush, is clearly on display for the audience to see, and periodically you’ll see the camera pan to President Bush to take in his reactions. Half the fun of a good roast is watching the roastee’s reactions during the roast, so it’s important to have the roastee clearly visible by the audience.

How does one prepare for a roast? First, you want to really think about the person who is being roasted. Do they have any strange habits or amusing stories in their past that you can discuss? When you think through these things you want to make sure that you cross anything off your list that is truly private information or will really hurt the person. The goal of a roast is to poke at them, not massacre them. Second, when selecting which aspects to poke fun at, you need to make sure that the items you choose are widely known by your audience. Roasts work when the majority of people in the audience can relate to the jokes being made. If you have an inside joke with the roastee, bringing it up during roast may be great fun for the two of you, but it will leave your audience unimpressed. Lastly, end on a positive note. While the jokes are definitely the fun part of a roast, you should leave the roastee knowing that you truly do care about and appreciate the person.

A eulogy is a speech given in honor of someone who has died. (Don’t confuse “eulogy” with “elegy,” a poem or song of mourning.) Unless you are a minister, priest, rabbi, imam, or other form of religious leader, you’ll probably not deliver too many eulogies in your lifetime. However, when the time comes to deliver a eulogy, it’s good to know what you’re doing and to adequately prepare your remarks. Watch the following clip of then-Senator Barack Obama delivering a eulogy at the funeral of civil rights activist Rosa Parks in November of 2005.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRsH92sJCr4

In this eulogy, Senator Obama delivers the eulogy by recalling Rosa Parks importance and her legacy in American history.

When preparing a eulogy, first you need to know as much information about the deceased as possible. The more information you have about the person, the more personal you can make the eulogy. While you can rely on your own information if you were close to the deceased, it is always a good idea to ask friends and relatives of the deceased for their memories, as these may add important facets that may not have occurred to you. Of course, if you were not very close to the deceased, you will need to ask friends and family for information. Second, although eulogies are delivered on the serious and sad occasion of a funeral or memorial service for the deceased, it is very helpful to look for at least one point to be lighter or humorous. In some cultures, in fact, the friends and family attending the funeral will expect the eulogy to be highly entertaining and amusing. While eulogies are not roasts, one goal of the humor or lighter aspects of a eulogy is to relieve the tension that is created by the serious nature of the occasion. Lastly, remember to tell the deceased’s story. Tell the audience about who this person was and what the person stood for in life. The more personal you can make a eulogy, the more touching it will be for the deceased’s friends and families. The eulogy should remind the audience to celebrate the person’s life as well as mourn their death.

Speeches of Farewell

A speech of farewell allows someone to say good-bye to one part of his or her life as he or she is moving on to the next part of life. Maybe you’ve accepted a new job and are leaving your current job, or you’re graduating from college and entering the work force. Whatever the case may be, periods of transition are often marked by speeches of farewell. Watch the following clip of Derek Jeter’s 2008 speech saying farewell to Yankee Stadium, built in 1923, before the New York Yankees moved to the new stadium that opened in 2009.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJrlTpQm0to

In this speech, Derek Jeter is not only saying good-bye to Yankee Stadium but also thanking the fans for their continued support.

When preparing a speech of farewell, the goal should be to thank the people in your current position and let them know how much you appreciate them as you make the move to your next position in life. In Derek Jeter’s speech, he starts by talking about the history of the 1923 Yankee Stadium and then thanks the fans for their support. Second, you want to express to your audience how much the experience has meant to you. A farewell speech is a time to commemorate and think about the good times you’ve had. As such, you should avoid negativity during this speech. Lastly, you want to make sure that you end on a high note. Derek Jeter concludes his speech by saying, “On behalf of this entire organization, we just want to take this moment to salute you, the greatest fans in the world!” at which point Jeter and the other players take off their ball caps and hold them up toward the audience.

Inspirational Speaking

The goal of an inspirational speech is to elicit or arouse an emotional state within an audience. In Section 18.2.1 “Ceremonial Speaking” , we looked at ceremonial speeches. Although some inspirational speeches are sometimes tied to ceremonial occasions, there are also other speaking contexts that call for inspirational speeches. For our purposes, we are going to look at two types of inspirational speeches: goodwill and speeches of commencement.

Speeches to Ensure Goodwill

Goodwill is an intangible asset that is made up of the favor or reputation of an individual or organization. Speeches of goodwill are often given in an attempt to get audience members to view the person or organization more favorably. Although speeches of goodwill are clearly persuasive, they try not to be obvious about the persuasive intent and are often delivered as information-giving speeches that focus on an individual or organization’s positives attributes. There are three basic types of speeches of goodwill: public relations, justification, and apology.

Speeches for Public Relations

In a public relations speech, the speaker is speaking to enhance one’s own image or the image of his or her organization. You can almost think of these speeches as cheerleading speeches because the ultimate goal is to get people to like the speaker and what he or she represents. In the following brief speech, the CEO of British Petroleum is speaking to reporters about what his organization is doing during the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCfa6AxmUHw

Notice that he keeps emphasizing what his company is doing to fix the problem. Every part of this speech is orchestrated to make BP look caring and attempts to get some amount of goodwill from the viewing public.

Speeches of Justification

The second common speech of goodwill is the speech of justification, which is given when someone attempts to defend why certain actions were taken or will be taken. In these speeches, speakers have already enacted (or decided to enact) some kind of behavior, and are now attempting to justify why the behavior is or was appropriate. In the following clip, President Bill Clinton discusses his decision to bomb key Iraqi targets after uncovering a plot to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mpWa7wNr5M

In this speech, President Clinton outlines his reasons for bombing Iraq to the American people and the globe. Again, the goal of this speech is to secure goodwill for President Clinton’s decisions both in the United States and on the world stage.

Speeches of Apology

The final speech of goodwill is the speech of apology. Frankly, these speeches have become more and more commonplace. Every time we turn around, a politician, professional athlete, musician, or actor/actress is doing something reprehensible and getting caught. In fact, the speech of apology has quickly become a fodder for humor as well. Let’s take a look at a real apology speech delivered by professional golfer Tiger Woods.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xs8nseNP4s0

When you need to make an apology speech, there are three elements that you need to include: be honest and take responsibility, say you’re sorry, and offer restitution. First, a speaker needs to be honest and admit to doing something wrong. The worst apology speeches are those in which the individual tries to sidestep the wrongdoing. Even if you didn’t do anything wrong, it is often best to take responsibility from a public perception perspective. Second, say that you are sorry. People need to know that you are remorseful for what you’ve done. One of the problems many experts saw with Tiger Woods’s speech is that he doesn’t look remorseful at all. While the words coming out of his mouth are appropriate, he looks like a robot forced to read from a manuscript written by his press agent. Lastly, you need to offer restitution. Restitution can come in the form of fixing something broken or a promise not to engage in such behavior in the future. People in society are very willing to forgive and forget when they are asked.

Speeches for Commencements

The second type of inspirational speech is the speech of commencement , which is designed to recognize and celebrate the achievements of a graduating class or other group of people. The most typical form of commencement speech happens when someone graduates from school. Nearly all of us have sat through commencement speeches at some point in our lives. And if you’re like us, you’ve heard good ones and bad ones. Numerous celebrities and politicians have been asked to deliver commencement speeches at colleges and universities. One famous and well-thought-out commencement speech was given by famed Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling at Harvard University in 2008.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nkREt4ZB-ck

J. K. Rowling’s speech has the perfect balance of humor and inspiration, which are two of the main ingredients of a great commencement speech.

If you’re ever asked to deliver a commencement speech, there are some key points to think through when deciding on your speech’s content.

- If there is a specific theme for the graduation, make sure that your commencement speech addresses that theme. If there is no specific theme, come up with one for your speech. Some common commencement speech themes are commitment, competitiveness, competence, confidence, decision making, discipline, ethics, failure (and overcoming failure), faith, generosity, integrity, involvement, leadership, learning, persistence, personal improvement, professionalism, reality, responsibility, and self-respect.

- Talk about your life and how graduates can learn from your experiences to avoid pitfalls or take advantages of life. How can your life inspire the graduates in their future endeavors?

- Make the speech humorous. Commencement speeches should be entertaining and make an audience laugh.

- Be brief! Nothing is more painful than a commencement speaker who drones on and on. Remember, the graduates are there to get their diplomas; their families are there to watch the graduates walk across the stage.

- Remember, while you may be the speaker, you’ve been asked to impart wisdom and advice for the people graduating and moving on with their lives, so keep it focused on them.

- Place the commencement speech into the broader context of the graduates’ lives. Show the graduates how the advice and wisdom you are offering can be utilized to make their own lives better.

Overall, it’s important to make sure that you have fun when delivering a commencement speech. Remember, it’s a huge honor and responsibility to be asked to deliver a commencement speech, so take the time to really think through and prepare your speech.

Key Takeaways

- There are eight common forms of ceremonial speaking: introduction, presentation, acceptance, dedication, toast, roast, eulogy, and farewell. Speeches of introduction are designed to introduce a speaker. Speeches of presentation are given when an individual is presenting an award of some kind. Speeches of acceptance are delivered by the person receiving an award or honor. Speeches of dedication are given when a new building or other place is being opened for the first time. Toasts are given to acknowledge and honor someone on a special occasion (e.g., wedding, birthday, retirement). Roasts are speeches designed to both praise and good-naturedly insult a person being honored. Eulogies are given during funerals and memorial services. Lastly, speeches of farewell are delivered by an individual who is leaving a job, community, or organization, and wants to acknowledge how much the group has meant.

- Inspirational speeches fall into two categories: goodwill (e.g., public relations, justification, and apology) and speeches of commencement. Speeches of goodwill attempt to get audience members to view the person or organization more favorably. On the other hand, speeches of commencement are delivered to recognize the achievements of a group of people.

- Imagine you’ve been asked to speak before a local civic organization such as the Kiwanis or Rotary Club. Develop a sample speech of introduction that you would like someone to give to introduce you.

- You’ve been asked to roast your favorite celebrity. Develop a two-minute roast.

- Develop a speech of commencement for your public speaking class.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.7 Goodwill Messages

Goodwill messages are as essential to healthy professional relationships as they are in personal ones. Thank-you, congratulatory, and sympathy notes add an important, feel-good human touch in a world that continues to embrace technology that isolates people while being marketed as a means of connecting them. The goodwill that such messages promote makes both the sender and receiver feel better about each other and themselves compared with where they’d be if the messages weren’t sent at all. In putting smiles on faces, such notes are effective especially because many people don’t send them—either because they feel that they’re too difficult to write or because it doesn’t even occur to them to do so. Since praise for some can be harder to think of and write than criticism, a brief guide on how to do it right may be of help here.

The 5 S’s of Goodwill Messages

Whether you’re writing thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy, follow the “5 S” principles of effective goodwill messages:

- Specific: Crafting the message around specific references to the situation that it addresses will steer such messages away from the impression that they were boilerplate template statements that you plagiarized.

- Sincere: A goodwill message will come off as genuine if it’s near to what you would say to the recipient in person. Avoid cliché Hallmark-card expressions and excessive formality such as It is with a heavy heart that I extend my heartfelt condolences to you in these sad times.

- Selfless: Refer only to the person or people involved rather than yourself. The spotlight is on them, not you. Avoid telling stories about how you experienced something similar in an attempt to show how you relate.

- Short: Full three-part messages and three-part paragraphs are unnecessary in thank-you notes, congratulatory messages, or expressions of sympathy. Don’t make the short length of the message deter you from setting aside time to draft it.

- Spontaneous: Move quickly to write your message so that it follows closely on the news that prompted it. A message that’s passed its “best before” date will appear stale to the recipient and make you look like you can’t manage your time effectively (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 144).

Thank-you Notes

In the world of business, not all transactions involve money. People do favours for each other, and acknowledging those with thank-you notes is essential for keeping relations positive. Such messages can be short and simple, as well as quick and easy to write, which means not sending them when someone does something nice to you appears ungrateful, rude, and inconsiderate. Someone who did you a favour might not bother to do so again if it goes unthanked. Such notes are ideal for situations such as those listed in Activity 7.6 below.

Activity 7.6 | Types of Thank-you Messages

In most situations, email or text is an appropriate channel for sending thank-you messages. Sending a thank-you note within 24 hours of interviewing for a job is not just extra-thoughtful but close to being an expected formality. To stand out from other candidates, hand-writing a thank-you card in such situations might even be a good idea.

Following the 5 S’s of goodwill messages given above, a typical thank-you email message for a favour might look like the example in Activity 7.7.

Activity 7.7 | Sample Thank-you Message

Notice that this message is short, specific to the situation that prompted it, sincere, relatively selfless, and spontaneously sent the day of the incident that prompted it. It would certainly bring a smile both to the recipient and sender, strengthening their professional bond.

Congratulatory Messages

Celebrating the successes of your professional peers shows class and tact. It’s good karma that will come back around as long as you keep putting out positive energy. Again, the 5 S’s apply in congratulatory messages, especially selflessness. Such messages are all about the person you’re congratulating. You could say, for instance, I really admire how you handled yourself with such grace and poise under such trying circumstances in the field today.

Expressions of Sympathy

Few situations require such sincerity and care with words as expressions of sympathy. Misfortune comes upon us all, and tough times are just a little more tolerable with the support of our friends, family, and community—including those we work with. When the loved-one of a close associate dies, for instance, expressing sympathy for their loss is customary, often with a card signed by everyone in the workplace who knows the bereaved. You can’t put an email on the mantle like you can a collection of cards from people showing they care.

What do you say in such situations? A simple I’m so sorry for your loss , despite being a stock expression, is better than letting the standard Hallmark card’s words speak for you (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 147). In some situations, laughter—or at least a chuckle—may be the best medicine, in which case something along the lines of Emily McDowell’s witty Empathy Cards would be more appropriate. McDowell’s There Is No Good Card for This: What to Say and Do When Life Is Scary, Awful, and Unfair to People You Love (2016) collaboration with empathy expert Kelsey Crowe, PhD, provides excellent advice. Showing empathy by saying that you know how hard it can be is helpful as long as you don’t go into any detail about their loss or yours. Remember, these messages should be selfless, and being too specific can be a little dangerous here if it produces traumatic imagery. Offering your condolences in the most respectful, sensitive manner possible is just the right thing to do.

Replying to Goodwill Messages

It wouldn’t go over well if someone thanked you for your help and you just stared at them silently. The normal reaction is to simply say You’re welcome! Replying to goodwill messages is therefore as essential as writing them. Such replies must be even shorter than the messages that they respond to. If someone says a few nice things about you in an email about something else, always acknowledge the goodwill by saying briefly “Thank you very much for the kind words” somewhere in your response.

Fundamentals of Business Communication Revised (2022) Copyright © 2022 by Venecia Williams & Nia Sonja is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

5 Ways to Establish Your Credibility in a Speech

Establishing credibility during a speech doesn't have to be difficult.

Jessica A. Kent

If you’ve ever given a speech or a presentation, you’re probably familiar with the most popular advice: Have a clear thesis. Know your audience. Write out your key talking points on note cards. Be aware of your body language. Practice, practice, practice.

But there’s one element of delivering a speech that you must include to increase both your audience’s engagement and your subject level authority: credibility. Building credibility will help you gain trust and boost your impact.

To make your public speaking more effective, here are five ways to build credibility with your audience that will increase trust, engagement, and impact.

What is Credibility?

We evaluate other people’s credibility every day. You may hear lawyers in courtrooms ask if a witness is credible. And in a time where fake news abounds, we ask about the credibility of websites, TV personalities, and commentators.

At the heart of credibility is believability. It is essentially asking, “Can this person be believed?” Credibility not only means believing that what someone says is true, but trusting them as well. You don’t trust your family member’s medical advice to be credible, but you trust your doctor’s.

It’s the same thing with public speaking. You must have credibility when delivering your speech and your audience must see you as trustworthy and believable. Credibility is a two-way street: You can present yourself as credible, but your audience also has to believe your credibility as well.

The Importance of Building Credibility with Your Audience

Here are a few reasons why building credibility is so important while delivering a speech or talk.

Attention and engagement : If audience members view you as credible, they are more likely to be engaged in listening to you. Polls show that those who trust leaders have six times the engagement than those who don’t . Listeners will pay more attention to you, which allows you to make more of an impact.

Call to action : Credibility helps your audience take you seriously and will convince them to consider the argument you’re trying to prove or to the information you’re teaching. They’ are also more likely to act on the information, or respond to your call to action. Additionally, personalization and speaking directly to your audience’s needs can boost audience response to call to action by more than 200% .

Perceived authority and future engagement : If your audience sees you as a credible and authoritative source on the subject, they’ll be more likely to engage with your work further. 68% of people see someone who has expertise in their field as a thought leader and this leverage will help you continue to increase your prestige and influence.

The Elements of Speaker Credibility

The first element of speaker credibility is not only the knowledge a speaker shares, but also how they gained that knowledge.

For example, if someone was presenting about the impact of community health programs and had spent years working to develop community programs, the audience would believe the speaker’s credibility due to their knowledge gained by experience.

However, if you do not have this experience and are presenting on a newly-learned topic, you can prove your credibility in other ways. A speaker can raise their credibility by explaining the research they did to prepare the speech, using data points to prove their thesis in the speech, and citing examples to fortify their argument. Showing that you invested time and effort to learn about a topic gives you the credibility to talk about it and can serve to increase your audience’s trust.

In Aristotle’s Rhetoric , he argues that one of the elements that contribute to a speaker’s “mode of persuasion” is their character. A speaker’s confidence, body language, engagement with the audience, positive tone, upbeat attitude, and care with which they share their subject matter can do as much to establish credibility as knowledge and examples.

Explore our Communication Professional & Executive Development courses.

5 Ways You Can Establish Credibility During Your Presentation

What are some ways to build your credibility so your audience trusts you as a speaker and source for information? These five tips will prepare you to have a credible impact when you deliver your speech.

1. Talk about yourself, your interests, and why you’re qualified.

One of the ways to establish credibility in your speech is to tell your audience why they should trust you to teach or inform them about a particular topic. Introduce yourself at the beginning and explain why you’re an authority on the given subject. You can offer examples of your past successes in the field, your educational background, and why you are personally invested in the topic.

Studies have shown that those who are aware of an author or speaker’s credentials perceive them to “ have a higher level of expertise and their information to be more credible .” Having an interest in, family connection to, or qualifications for the topic you’re speaking about increases your credibility.

2. Connect to your audience by speaking to them and their needs, and offer them a new way of thinking.

Audiences want to know what they’re going to get out of your talk. Consider how you’ll teach them something new, offer new strategies to take back to their workplace, or challenge them to look at the world in a different way.

If your audience knows very little about the topic, use language that is easy to understand to make the information more accessible.

Using “you” when addressing an audience is also proven to be an effective way to connect. This type of personalized engagement with the audience will show that you care about them and what they take away from the talk.

3. Cite sources, show data, and tell stories.

As with any research paper, study, or article, using sources to reinforce what you’re saying gives you credibility because another expert’s credibility is backing you up. For example, if you’re giving a speech on the benefits of technology in the medical field, citing studies that have already proven its benefits will help your audience be more willing to believe your argument. It also shows that you’ve done your research, and you’re placing your topic amidst an ongoing conversation. Additionally, telling a story increases audience retention by upwards of 70% .

4. Use open and friendly body language, take your time speaking, and make eye contact.

Studies show that upwards of 90% of what someone communicates is through their body language. We’ve all experienced situations where we’re more inclined to engage with someone who makes eye contact, has a friendly tone, faces us directly, and has a confident stance.

The same should be true for public speaking. The way you portray yourself while delivering your speech can help boost your credibility, and an audience will be more responsive to someone who portrays themselves as confident and approachable.

5. Offer to take questions at the end.

Listening to and answering questions at the end of your speech or presentation can be another chance to demonstrate your credibility with your audience. If asked, you can elaborate on the content you spoke about, talk about the research you conducted, and tell more stories that relate to your topic. It’s also a more informal time where you can further connect with individuals in the audience.

How Harvard Can Help with Your Public Speaking

Whether you’re preparing a speech to give in a class, compiling a presentation for coworkers or stakeholders, or planning your first TED Talk, Harvard can help you accomplish your public speaking goals with classes offered through Harvard’s Division of Continuing Education Professional & Executive Development.

If you want to learn ways to gain credibility during your speech and better connect with your audience, our course “ Communication Strategies: Presenting with Impact ” can help.

Centering around oral presentations and small group activities, this course can help you not only craft and deliver a speech, but can teach you how to inject credibility into that speech so that you build trust with your audience. Learning how to effectively communicate to your audience in both words, body language, and narrative style is a key skill that everyone — especially business professionals — should possess.

Commit to being a better public speaker and communicator today by learning more about the course here .

Explore all Harvard DCE Professional & Executive Development courses.

About the Author

Jessica A. Kent is a freelance writer based in Boston, Mass. and a Harvard Extension School alum. Her digital marketing content has been featured on Fast Company, Forbes, Nasdaq, and other industry websites; her essays and short stories have been featured in North American Review, Emerson Review, Writer’s Bone, and others.

How to Create Positive Customer Experiences for Your Business

Developing positive customer experiences is all about building relationships—and your reputation.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

- Noise to Signal Cartoon

Speaking at a rally? Here’s how to make it count.

by Rob Cottingham | Feb 20, 2017 | Speaking , Speechwriting | 0 comments

If you work with a mission-driven organization, you may find yourself speaking at a political rally soon. (Maybe sooner than you think, the way things are going.)

You may be there to offer a short greeting and encouragement, or to deliver a rousing featured address, or something in between. Either way, there’s a lot you can do to ensure your rally speech stands out and makes a difference.

I’ve written plenty of speeches for rallies and protest marches over the years, and it’s taught me a lot about what works and what doesn’t. And for this post, I’m supplementing my advice with insight from someone with an abundance of first-hand speaking experience: Tzeporah Berman , an internationally renowned environmental campaigner who has been speaking at rallies for a quarter century.

Planning your rally speech

Know your goals..

As with everything else you’re doing, your speech needs to spring from a theory of change . What do you and your organization want your remarks to accomplish? Do you want to introduce yourselves to an audience that isn’t familiar with you and your work? Reassure allies who may not be aware of your support? Ask people to donate money or volunteer their time? Inform the crowd of a major piece of news?

Whatever your goal, be sure it aligns with both your organization’s strategy and the rally’s overall purpose…and then let it drive your message. (And there’s a goal you know you’ll want to achieve: helping ensure the participants have a positive, engaging experience.)

Know the one thing you want people to remember.

A clear focus is helpful to pretty much every speech — but nowhere is it more important than at a rally. Your audience has an uphill battle in listening attentively to you: the acoustics are almost always less than ideal; they’ve probably been on their feet for a while, so they’re physically uncomfortable; and there’s probably a lot of background noise and chatter.

So give them every possible chance to understand where you’re coming from. And say it more than once: repetition not only aids memory, but increases the odds an audience member will hear your message at least once.

Advocate for the audience.

Time passes differently at a rally. Just because the organizers offer you 20 minutes after a long lineup of other speakers doesn’t mean you have to take it. “Short, short, short,” Tzeporah says; five minutes is a healthy chunk of time for a rally speech. Once they pass the 10-minute mark, only the most gifted speakers are likely to earn much goodwill from the audience — or giving them anything they’ll retain afterward. Work with the organizers to keep the timing humane.

Read — and heed — the agenda.

You can mention some of the speakers who have preceded you, or who are coming up — especially if they, or their organizations or missions, help underline a point you’re going to make. If you’re coming on right after a performance, you can refer to it and bridge to your topic. On the other hand, if three speakers before you are likely to cover the same ground you want to till, think about how you can approach it differently.

Writing your rally speech

Get right to the point..

Long preambles don’t serve anyone. There may well be things you need to say at the outset to thank and recognize people, groups and communities. But don’t dwell on these (especially if every other speaker is going to be saying the same thing). You’ll use up your audience’s attention long before you get to what you really want them to remember.

Keep it simple.

My friends at The NOW Group talk about a “connection, contrast, solution” structure: connect emotionally with your audience to establish common ground, draw a contrast with the point of view you’re opposing, and describe the solution you support. Many activists, including Tzeporah, draw on Marshall Ganz’s “ Story of self, story of us, story of now ” approach, which parallels NOW’s in many ways. (I first came across it through Jennifer Hollett , now head of news and government at Twitter Canada.) And classic storytelling covers three acts: establishing, developing and resolving a dramatic conflict.

Whatever structure you use, make it a simple one that sticks to your message — and ends on an emotional high note.

Establish who you are.

Tzeporah points out that there’s a good chance most of the rally audience won’t know you, and may not know your organization, Unless the rally emcee delivers a long introduction (which you don’t want them to do), you’ll want to begin by establishing who you are, what you represent and how you connect to the issue at hand.

And don’t be afraid to get personal here; your audience wants to know you share their passion.

Motivate, don’t educate.

The people at a rally are almost certainly already on your side. You want to motivate and inspire them with your speech, and build their sense of common purpose.