Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

53k Accesses

426 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

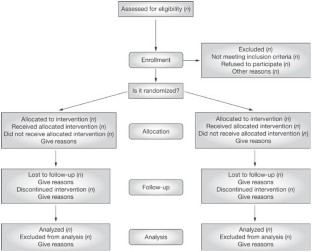

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

How to critically appraise an article

Affiliation.

- 1 Surgical Outcomes Research Centre, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Missenden Road, Sydney, NSW 2050, Australia. [email protected]

- PMID: 19153565

- DOI: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Publication types

- Decision Making*

- Evidence-Based Medicine*

Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies

- First Online: 05 August 2020

Cite this chapter

- Edward Purssell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3748-0864 3 &

- Niall McCrae ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9776-7694 4

9137 Accesses

There is great variation in the type and quality of research evidence. Having completed your search and assembled your studies, the next step is to critically appraise the studies to ascertain their quality. Ultimately you will be making a judgement about the overall evidence, but that comes later. You will see throughout this chapter that we make a clear differentiation between the individual studies and what we call the body of evidence , which is all of the studies and anything else that we use to answer the question or to make a recommendation. This chapter deals with only the first of these—the individual studies. Critical appraisal, like everything else in systematic literature reviewing, is a scientific exercise that requires individual judgement, and we describe some tools to help you.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) (2016) OCEBM levels of evidence. In: CEBM. https://www.cebm.net/2016/05/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/ . Accessed 17 Apr 2020

Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) (2017) Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide

Google Scholar

Daly J, Willis K, Small R et al (2007) A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J Clin Epidemiol 60:43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

Article PubMed Google Scholar

EQUATOR Network (2020) What is a reporting guideline?—The EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/about-us/what-is-a-reporting-guideline/ . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 4:e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

Article Google Scholar

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2016) The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 352:i1152. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1152

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Boutron I, Page MJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Lundh A, Hróbjartsson A (2019) Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019), Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) CASP checklists. In: CASP—critical appraisal skills programme. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Chapter Google Scholar

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al (2011) GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 64:1283–1293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D et al (2019) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp . Accessed 7 Mar 2020

Cochrane Community (2020) Glossary—Cochrane community. https://community.cochrane.org/glossary#letter-R . Accessed 8 Mar 2020

Messick S (1989) Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educ Res 18:5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018002005

Sparkes AC (2001) Myth 94: qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qual Health Res 11:538–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230101100409

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Aguinis H, Solarino AM (2019) Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: the case of interviews with elite informants. Strat Manag J 40:1291–1315. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3015

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA

Book Google Scholar

Hannes K (2011) Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K et al (eds) Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, London

Munn Z, Porritt K, Lockwood C et al (2014) Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: the ConQual approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-108

Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N et al (2013) ‘Trying to pin down jelly’—exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-46

Katikireddi SV, Egan M, Petticrew M (2015) How do systematic reviews incorporate risk of bias assessments into the synthesis of evidence? A methodological study. J Epidemiol Community Health 69:189–195. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204711

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE et al (2019) Chapter 9: Summarizing study characteristics and preparing for synthesis. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (2019) Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, London

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health Sciences, City, University of London, London, UK

Edward Purssell

Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, King’s College London, London, UK

Niall McCrae

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Edward Purssell .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Purssell, E., McCrae, N. (2020). Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies. In: How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_6

Published : 05 August 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-49671-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-49672-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Critical Appraisal: A Checklist

Posted on 6th September 2016 by Robert Will

Critical appraisal of scientific literature is a necessary skill for healthcare students. Students can be overwhelmed by the vastness of search results. Database searching is a skill in itself, but will not be covered in this blog. This blog assumes that you have found a relevant journal article to answer a clinical question. After selecting an article, you must be able to sit with the article and critically appraise it. Critical appraisal of a journal article is a literary and scientific systematic dissection in an attempt to assign merit to the conclusions of an article. Ideally, an article will be able to undergo scrutiny and retain its findings as valid.

The specific questions used to assess validity change slightly with different study designs and article types. However, in an attempt to provide a generalized checklist, no specific subtype of article has been chosen. Rather, the 20 questions below should be used as a quick reference to appraise any journal article. The first four checklist questions should be answered “Yes.” If any of the four questions are answered “no,” then you should return to your search and attempt to find an article that will meet these criteria.

Critical appraisal of…the Introduction

- Does the article attempt to answer the same question as your clinical question?

- Is the article recently published (within 5 years) or is it seminal (i.e. an earlier article but which has strongly influenced later developments)?

- Is the journal peer-reviewed?

- Do the authors present a hypothesis?

Critical appraisal of…the Methods

- Is the study design valid for your question?

- Are both inclusion and exclusion criteria described?

- Is there an attempt to limit bias in the selection of participant groups?

- Are there methodological protocols (i.e. blinding) used to limit other possible bias?

- Do the research methods limit the influence of confounding variables?

- Are the outcome measures valid for the health condition you are researching?

Critical appraisal of…the Results

- Is there a table that describes the subjects’ demographics?

- Are the baseline demographics between groups similar?

- Are the subjects generalizable to your patient?

- Are the statistical tests appropriate for the study design and clinical question?

- Are the results presented within the paper?

- Are the results statistically significant and how large is the difference between groups?

- Is there evidence of significance fishing (i.e. changing statistical tests to ensure significance)?

Critical appraisal of…the Discussion/Conclusion

- Do the authors attempt to contextualise non-significant data in an attempt to portray significance? (e.g. talking about findings which had a trend towards significance as if they were significant).

- Do the authors acknowledge limitations in the article?

- Are there any conflicts of interests noted?

This is by no means a comprehensive checklist of how to critically appraise a scientific journal article. However, by answering the previous 20 questions based on a detailed reading of an article, you can appraise most articles for their merit, and thus determine whether the results are valid. I have attempted to list the questions based on the sections most commonly present in a journal article, starting at the introduction and progressing to the conclusion. I believe some of these items are weighted heavier than others (i.e. methodological questions vs journal reputation). However, without taking this list through rigorous testing, I cannot assign a weight to them. Maybe one day, you will be able to critically appraise my future paper: How Online Checklists Influence Healthcare Students’ Ability to Critically Appraise Journal Articles.

Feature Image by Arek Socha from Pixabay

Robert Will

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Critical Appraisal: A Checklist

Hi Ella, I have found a checklist here for before and after study design: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools and you may also find a checklist from this blog, which has a huge number of tools listed: https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2018/01/12/appraising-the-appraisal/

What kind of critical appraisal tool can be used for before and after study design article? Thanks

Hello, I am currently writing a book chapter on critical appraisal skills. This chapter is limited to 1000 words so your simple 20 questions framework would be the perfect format to cite within this text. May I please have your permission to use your checklist with full acknowledgement given to you as author? Many thanks

Thank you Robert, I came across your checklist via the Royal College of Surgeons of England website; https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/dissecting-the-literature-the-importance-of-critical-appraisal/ . I really liked it and I have made reference to it for our students. I really appreciate your checklist and it is still current, thank you.

Hi Kirsten. Thank you so much for letting us know that Robert’s checklist has been used in that article – that’s so good to see. If any of your students have any comments about the blog, then do let us know. If you also note any topics that you would like to see on the website, then we can add this to the list of suggested blogs for students to write about. Thank you again. Emma.

i am really happy with it. thank you very much

A really useful guide for helping you ask questions about the studies you are reviewing BRAVO

Dr.Suryanujella,

Thank you for the comment. I’m glad you find it helpful.

Feel free to use the checklist. S4BE asks that you cite the page when you use it.

I have read your article and found it very useful , crisp with all relevant information.I would like to use it in my presentation with your permission

That’s great thank you very much. I will definitely give that a go.

I find the MEAL writing approach very versatile. You can use it to plan the entire paper and each paragraph within the paper. There are a lot of helpful MEAL resources online. But understanding the acronym can get you started.

M-Main Idea (What are you arguing?) E-Evidence (What does the literature say?) A-Analysis (Why does the literature matter to your argument?) L-Link (Transition to next paragraph or section)

I hope that is somewhat helpful. -Robert

Hi, I am a university student at Portsmouth University, UK. I understand the premise of a critical appraisal however I am unsure how to structure an essay critically appraising a paper. Do you have any pointers to help me get started?

Thank you. I’m glad that you find this helpful.

Very informative & to the point for all medical students

How can I know what is the name of this checklist or tool?

This is a checklist that the author, Robert Will, has designed himself.

Thank you for asking. I am glad you found it helpful. As Emma said, please cite the source when you use it.

Greetings Robert, I am a postgraduate student at QMUL in the UK and I have just read this comprehensive critical appraisal checklist of your. I really appreciate you. if I may ask, can I have it downloaded?

Please feel free to use the information from this blog – if you could please cite the source then that would be much appreciated.

Robert Thank you for your comptrehensive account of critical appraisal. I have just completed a teaching module on critical appraisal as part of a four module Evidence Based Medicine programme for undergraduate Meducal students at RCSI Perdana medical school in Malaysia. If you are agreeable I would like to cite it as a reference in our module.

Anthony, Please feel free to cite my checklist. Thank you for asking. I hope that your students find it helpful. They should also browse around S4BE. There are numerous other helpful articles on this site.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Risk Communication in Public Health

Learn why effective risk communication in public health matters and where you can get started in learning how to better communicate research evidence.

Why was the CONSORT Statement introduced?

The CONSORT statement aims at comprehensive and complete reporting of randomized controlled trials. This blog introduces you to the statement and why it is an important tool in the research world.

Measures of central tendency in clinical research papers: what we should know whilst analysing them

Learn more about the measures of central tendency (mean, mode, median) and how these need to be critically appraised when reading a paper.

- CASP Checklists

- How to use our CASP Checklists

- Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- Subscriptions

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

How to Critically Appraise a Research Paper

Research papers are a powerful means through which millions of researchers around the globe pass on knowledge about our world.

However, the quality of research can be highly variable. To avoid being misled, it is vital to perform critical appraisals of research studies to assess the validity, results and relevance of the published research. Critical appraisal skills are essential to be able to identify whether published research provides results that can be used as evidence to help improve your practice.

What is a critical appraisal?

Most of us know not to believe everything we read in the newspaper or on various media channels. But when it comes to research literature and journals, they must be critically appraised due to the nature of the context. In order for us to trust research papers, we want to be safe in the knowledge that they have been efficiently and professionally checked to confirm what they are saying. This is where a critical appraisal comes in.

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, value and relevance in a particular context. We have put together a more detailed page to explain what critical appraisal is to give you more information.

Why is a critical appraisal of research required?

Critical appraisal skills are important as they enable you to systematically and objectively assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers. When a research article is published, who wrote it should not be an indication of its trustworthiness and relevance.

What are the benefits of performing critical appraisals for research papers?

Performing a critical appraisal helps to:

- Reduce information overload by eliminating irrelevant or weak studies

- Identify the most relevant papers

- Distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and belief

- Assess the validity of the study

- Check the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

How to critically appraise a research paper

There are some key questions to consider when critically appraising a paper. These include:

- Is the study relevant to my field of practice?

- What research question is being asked?

- Was the study design appropriate for the research question?

CASP has several checklists to help with performing a critical appraisal which we believe are crucial because:

- They help the user to undertake a complex task involving many steps

- They support the user in being systematic by ensuring that all important factors or considerations are taken into account

- They increase consistency in decision-making by providing a framework

In addition to our free checklists, CASP has developed a number of valuable online e-learning modules designed to increase your knowledge and confidence in conducting a critical appraisal.

Introduction To Critical Appraisal & CASP

This Module covers the following:

- Challenges using evidence to change practice

- 5 steps of evidence-based practice

- Developing critical appraisal skills

- Integrating and acting on the evidence

- The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)

- Online Learning

- Quasi-Experimental Design

- The Role of Homogeneity in Research

- PICO Search Strategy Tips & Examples

- What Is a Subgroup Analysis?

- What Is Evidence-Based Practice?

- What Is A Cross-Sectional Study?

- What Is A PICO Tool?

- What Is A Pilot Study?

- Different Types of Bias in Research

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) for assessing multiple types of evidence

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected]

Contributor: Jennifer Kruse, Public Health Agency of Canada – Conceptualization and project administration

Series information

Scientific writing

Collection date 2017 Sep 7.

Healthcare professionals are often expected to critically appraise research evidence in order to make recommendations for practice and policy development. Here we describe the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) currently used by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The CAT consists of: algorithms to identify the type of study design, three separate tools (for appraisal of analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews), additional tools to support the appraisal process, and guidance for summarizing evidence and drawing conclusions about a body of evidence. Although the toolkit was created to assist in the development of national guidelines related to infection prevention and control, clinicians, policy makers and students can use it to guide appraisal of any health-related quantitative research. Participants in a pilot test completed a total of 101 critical appraisals and found that the CAT was user-friendly and helpful in the process of critical appraisal. Feedback from participants of the pilot test of the CAT informed further revisions prior to its release. The CAT adds to the arsenal of available tools and can be especially useful when the best available evidence comes from non-clinical trials and/or studies with weak designs, where other tools may not be easily applied.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals, researchers and policy makers are often involved in the development of public health policies or guidelines. The most valuable guidelines provide a basis for evidence-based practice with recommendations informed by current, high quality, peer-reviewed scientific evidence. To develop such guidelines, the available evidence needs to be critically appraised so that recommendations are based on the "best" evidence. The ability to critically appraise research is, therefore, an essential skill for health professionals serving on policy or guideline development working groups.

Our experience with working groups developing infection prevention and control guidelines was that the review of relevant evidence went smoothly while the critical appraisal of the evidence posed multiple challenges. Three main issues were identified. First, although working group members had strong expertise in infection prevention and control or other areas relevant to the guideline topic, they had varying levels of expertise in research methods and critical appraisal. Second, the critical appraisal tools in use at that time focused largely on analytic studies (such as clinical trials), and lacked definitions of key terms and explanations of the criteria used in the studies. As a result, the use of these tools by working group members did not result in a consistent way of appraising analytic studies nor did the tools provide a means of assessing descriptive studies and literature reviews. Third, working group members wanted guidance on how to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing a body of evidence.

To address these issues, a review of existing critical appraisal tools was conducted. We found that the majority of existing tools were design-specific, with considerable variability in intent, criteria appraised and construction of the tools. A systematic review reported that fewer than half of existing tools had guidelines for use of the tool and interpretation of the items ( 1 ). The well-known Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating-of-evidence system and the Cochrane tools for assessing risk of bias were considered for use ( 2 ), ( 3 ). At that time, the guidelines for using these tools were limited, and the tools were focused primarily on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials. For feasibility and ethical reasons, clinical trials are rarely available for many common infection prevention and control issues ( 4 ), ( 5 ). For example, there are no intervention studies assessing which practice restrictions, if any, should be placed on healthcare workers who are infected with a blood-borne pathogen. Working group members were concerned that if they used GRADE, all evidence would be rated as very low or as low quality or certainty, and recommendations based on this evidence may be interpreted as unconvincing, even if they were based on the best or only available evidence.

The team decided to develop its own critical appraisal toolkit. So a small working group was convened, led by an epidemiologist with expertise in research, methodology and critical appraisal, with the goal of developing tools to critically appraise studies informing infection prevention and control recommendations. This article provides an overview of the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT). The full document, entitled Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit is available online ( 6 ).

Following a review of existing critical appraisal tools, studies informing infection prevention and control guidelines that were in development were reviewed to identify the types of studies that would need to be appraised using the CAT. A preliminary draft of the CAT was used by various guideline development working groups and iterative revisions were made over a two year period. A pilot test of the CAT was then conducted which led to the final version ( 6 ).

The toolkit is set up to guide reviewers through three major phases in the critical appraisal of a body of evidence: appraisal of individual studies; summarizing the results of the appraisals; and appraisal of the body of evidence.

Tools for critically appraising individual studies

The first step in the critical appraisal of an individual study is to identify the study design; this can be surprisingly problematic, since many published research studies are complex. An algorithm was developed to help identify whether a study was an analytic study, a descriptive study or a literature review (see text box for definitions). It is critical to establish the design of the study first, as the criteria for assessment differs depending on the type of study.

Definitions of the types of studies that can be analyzed with the Critical Appraisal Toolkit*

Analytic study: A study designed to identify or measure effects of specific exposures, interventions or risk factors. This design employs the use of an appropriate comparison group to test epidemiologic hypotheses, thus attempting to identify associations or causal relationships.

Descriptive study: A study that describes characteristics of a condition in relation to particular factors or exposure of interest. This design often provides the first important clues about possible determinants of disease and is useful for the formulation of hypotheses that can be subsequently tested using an analytic design.

Literature review: A study that analyzes critical points of a published body of knowledge. This is done through summary, classification and comparison of prior studies. With the exception of meta-analyses, which statistically re-analyze pooled data from several studies, these studies are secondary sources and do not report any new or experimental work.

* Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit ( 6 )

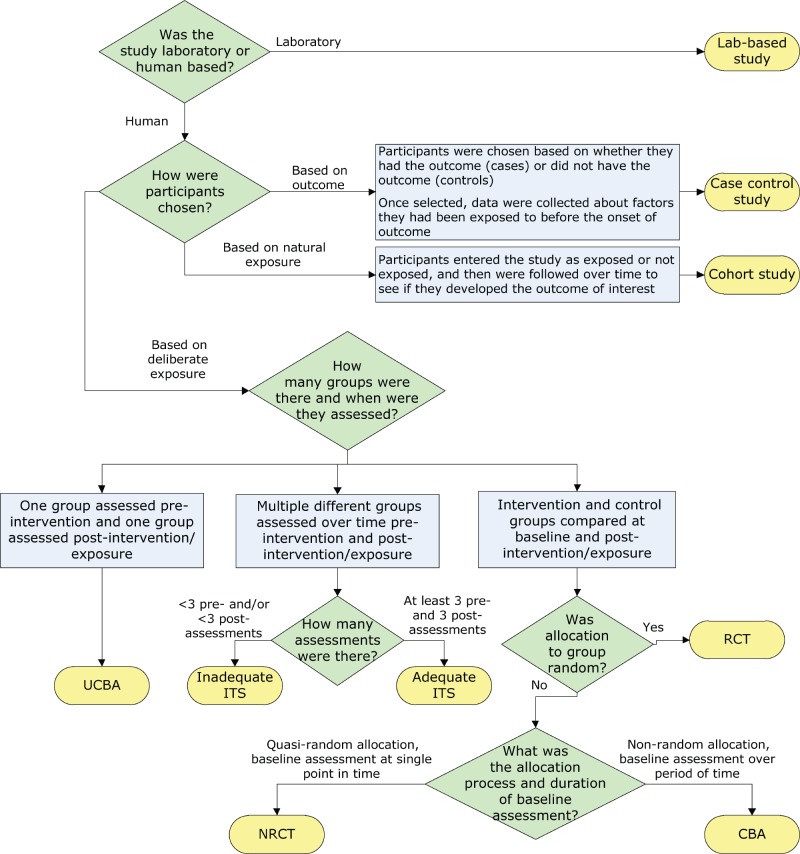

Separate algorithms were developed for analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews to help reviewers identify specific designs within those categories. The algorithm below, for example, helps reviewers determine which study design was used within the analytic study category ( Figure 1 ). It is based on key decision points such as number of groups or allocation to group. The legends for the algorithms and supportive tools such as the glossary provide additional detail to further differentiate study designs, such as whether a cohort study was retrospective or prospective.

Figure 1. Algorithm for identifying the type of analytic study.

Abbreviations: CBA, controlled before-after; ITS, interrupted time series; NRCT, non-randomized controlled trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UCBA, uncontrolled before-after

Separate critical appraisal tools were developed for analytic studies, for descriptive studies and for literature reviews, with relevant criteria in each tool. For example, a summary of the items covered in the analytic study critical appraisal tool is shown in Table 1 . This tool is used to appraise trials, observational studies and laboratory-based experiments. A supportive tool for assessing statistical analysis was also provided that describes common statistical tests used in epidemiologic studies.

Table 1. Aspects appraised in analytic study critical appraisal tool.

The descriptive study critical appraisal tool assesses different aspects of sampling, data collection, statistical analysis, and ethical conduct. It is used to appraise cross-sectional studies, outbreak investigations, case series and case reports.

The literature review critical appraisal tool assesses the methodology, results and applicability of narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

After appraisal of individual items in each type of study, each critical appraisal tool also contains instructions for drawing a conclusion about the overall quality of the evidence from a study, based on the per-item appraisal. Quality is rated as high, medium or low. While a RCT is a strong study design and a survey is a weak design, it is possible to have a poor quality RCT or a high quality survey. As a result, the quality of evidence from a study is distinguished from the strength of a study design when assessing the quality of the overall body of evidence. A definition of some terms used to evaluate evidence in the CAT is shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. Definition of terms used to evaluate evidence.

* Considered strong design if there are at least two control groups and two intervention groups. Considered moderate design if there is only one control and one intervention group

Tools for summarizing the evidence

The second phase in the critical appraisal process involves summarizing the results of the critical appraisal of individual studies. Reviewers are instructed to complete a template evidence summary table, with key details about each study and its ratings. Studies are listed in descending order of strength in the table. The table simplifies looking across all studies that make up the body of evidence informing a recommendation and allows for easy comparison of participants, sample size, methods, interventions, magnitude and consistency of results, outcome measures and individual study quality as determined by the critical appraisal. These evidence summary tables are reviewed by the working group to determine the rating for the quality of the overall body of evidence and to facilitate development of recommendations based on evidence.

Rating the quality of the overall body of evidence

The third phase in the critical appraisal process is rating the quality of the overall body of evidence. The overall rating depends on the five items summarized in Table 2 : strength of study designs, quality of studies, number of studies, consistency of results and directness of the evidence. The various combinations of these factors lead to an overall rating of the strength of the body of evidence as strong, moderate or weak as summarized in Table 3 .

Table 3. Criteria for rating evidence on which recommendations are based.

A unique aspect of this toolkit is that recommendations are not graded but are formulated based on the graded body of evidence. Actions are either recommended or not recommended; it is the strength of the available evidence that varies, not the strength of the recommendation. The toolkit does highlight, however, the need to re-evaluate new evidence as it becomes available especially when recommendations are based on weak evidence.

Pilot test of the CAT

Of 34 individuals who indicated an interest in completing the pilot test, 17 completed it. Multiple peer-reviewed studies were selected representing analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews. The same studies were assigned to participants with similar content expertise. Each participant was asked to appraise three analytic studies, two descriptive studies and one literature review, using the appropriate critical appraisal tool as identified by the participant. For each study appraised, one critical appraisal tool and the associated tool-specific feedback form were completed. Each participant also completed a single general feedback form. A total of 101 of 102 critical appraisals were conducted and returned, with 81 tool-specific feedback forms and 14 general feedback forms returned.

The majority of participants (>85%) found the flow of each tool was logical and the length acceptable but noted they still had difficulty identifying the study designs ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Pilot test feedback on user friendliness.

* Number of tool-specific forms returned for total number of critical appraisals conducted

The vast majority of the feedback forms (86–93%) indicated that the different tools facilitated the critical appraisal process. In the assessment of consistency, however, only four of ten analytic studies appraised (40%), had complete agreement on the rating of overall study quality by participants, the other six studies had differences noted as mismatches. Four of the six studies with mismatches were observational studies. The differences were minor. None of the mismatches included a study that was rated as both high and low quality by different participants. Based on the comments provided by participants, most mismatches could likely have been resolved through discussion with peers. Mismatched ratings were not an issue for the descriptive studies and literature reviews. In summary, the pilot test provided useful feedback on different aspects of the toolkit. Revisions were made to address the issues identified from the pilot test and thus strengthen the CAT.

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to the needs of infection control professionals reviewing literature that generally did not include clinical trial evidence. The toolkit was designed to meet the identified needs for training in critical appraisal with extensive instructions and dictionaries, and tools applicable to all three types of studies (analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews). The toolkit provided a method to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing the strength of a body of evidence and assigning a grade. Recommendations are then developed based on the graded body of evidence. This grading system has been used by the Public Health Agency of Canada in the development of recent infection prevention and control guidelines ( 5 ), ( 7 ). The toolkit has also been used for conducting critical appraisal for other purposes, such as addressing a practice problem and serving as an educational tool ( 8 ), ( 9 ).

The CAT has a number of strengths. It is applicable to a wide variety of study designs. The criteria that are assessed allow for a comprehensive appraisal of individual studies and facilitates critical appraisal of a body of evidence. The dictionaries provide reviewers with a common language and criteria for discussion and decision making.

The CAT also has a number of limitations. The tools do not address all study designs (e.g., modelling studies) and the toolkit provides limited information on types of bias. Like the majority of critical appraisal tools ( 10 ), ( 11 ), these tools have not been tested for validity and reliability. Nonetheless, the criteria assessed are those indicated as important in textbooks and in the literature ( 12 ), ( 13 ). The grading scale used in this toolkit does not allow for comparison of evidence grading across organizations or internationally, but most reviewers do not need such comparability. It is more important that strong evidence be rated higher than weak evidence, and that reviewers provide rationales for their conclusions; the toolkit enables them to do so.

Overall, the pilot test reinforced that the CAT can help with critical appraisal training and can increase comfort levels for those with limited experience. Further evaluation of the toolkit could assess the effectiveness of revisions made and test its validity and reliability.

A frequent question regarding this toolkit is how it differs from GRADE as both distinguish stronger evidence from weaker evidence and use similar concepts and terminology. The main differences between GRADE and the CAT are presented in Table 5 . Key differences include the focus of the CAT on rating the quality of individual studies, and the detailed instructions and supporting tools that assist those with limited experience in critical appraisal. When clinical trials and well controlled intervention studies are or become available, GRADE and related tools from Cochrane would be more appropriate ( 2 ), ( 3 ). When descriptive studies are all that is available, the CAT is very useful.

Table 5. Comparison of features of the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) and GRADE.

Abbreviation: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to needs for training in critical appraisal, assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs, and a method for going from assessing individual studies to characterizing the strength of a body of evidence. Clinician researchers, policy makers and students can use these tools for critical appraisal of studies whether they are trying to develop policies, find a potential solution to a practice problem or critique an article for a journal club. The toolkit adds to the arsenal of critical appraisal tools currently available and is especially useful in assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs.

Authors’ Statement

DM – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

TO – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

KD – Conceptualization, review and editing, supervision and project administration

Acknowledgements

We thank the Infection Prevention and Control Expert Working Group of the Public Health Agency of Canada for feedback on the development of the toolkit, Lisa Marie Wasmund for data entry of the pilot test results, Katherine Defalco for review of data and cross-editing of content and technical terminology for the French version of the toolkit, Laurie O’Neil for review and feedback on early versions of the toolkit, Frédéric Bergeron for technical support with the algorithms in the toolkit and the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control of the Public Health Agency of Canada for review, feedback and ongoing use of the toolkit. We thank Dr. Patricia Huston, Canada Communicable Disease Report Editor-in-Chief, for a thorough review and constructive feedback on the draft manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

- 1. Katrak P, Bialocerkowski AE, Massy-Westropp N, Kumar S, Grimmer KA. A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004. Sep;4:22. 10.1186/1471-2288-4-22 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. GRADE Working Group. Criteria for applying or using GRADE. www.gradeworkinggroup.org [Accessed July 25, 2017].

- 3. Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org

- 4. Khan AR, Khan S, Zimmerman V, Baddour LM, Tleyjeh IM. Quality and strength of evidence of the Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2010. Nov;51(10):1147–56. 10.1086/656735 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Public Health Agency of Canada. Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in healthcare settings. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/guide/summary-sommaire/tihs-tims-eng.php [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 6. Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP40-119-2014-eng.pdf [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 7. Public Health Agency of Canada. Hand hygiene practices in healthcare settings. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/nosocomial-occupational-infections/hand-hygiene-practices-healthcare-settings.html [Accessed December 4, 2015].

- 8. Ha S, Paquette D, Tarasuk J, Dodds J, Gale-Rowe M, Brooks JI et al. A systematic review of HIV testing among Canadian populations. Can J Public Health 2014. Jan;105(1):e53–62. 10.17269/cjph.105.4128 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Stevens LK, Ricketts ED, Bruneau JE. Critical appraisal through a new lens. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2014. Jun;27(2):10–3. 10.12927/cjnl.2014.23843 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Lohr KN. Rating the strength of scientific evidence: relevance for quality improvement programs. Int J Qual Health Care 2004. Feb;16(1):9–18. 10.1093/intqhc/mzh005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Crowe M, Sheppard L. A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011. Jan;64(1):79–89. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Young JM, Solomon MJ. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009. Feb;6(2):82–91. 10.1038/ncpgasthep1331 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 9 th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Chapter XX, Literature reviews: Finding and critiquing the evidence p. 94-125. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (348.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

How To Write a Critical Appraisal

A critical appraisal is an academic approach that refers to the systematic identification of strengths and weakness of a research article with the intent of evaluating the usefulness and validity of the work’s research findings. As with all essays, you need to be clear, concise, and logical in your presentation of arguments, analysis, and evaluation. However, in a critical appraisal there are some specific sections which need to be considered which will form the main basis of your work.

Structure of a Critical Appraisal

Introduction.

Your introduction should introduce the work to be appraised, and how you intend to proceed. In other words, you set out how you will be assessing the article and the criteria you will use. Focusing your introduction on these areas will ensure that your readers understand your purpose and are interested to read on. It needs to be clear that you are undertaking a scientific and literary dissection and examination of the indicated work to assess its validity and credibility, expressed in an interesting and motivational way.

Body of the Work

The body of the work should be separated into clear paragraphs that cover each section of the work and sub-sections for each point that is being covered. In all paragraphs your perspectives should be backed up with hard evidence from credible sources (fully cited and referenced at the end), and not be expressed as an opinion or your own personal point of view. Remember this is a critical appraisal and not a presentation of negative parts of the work.

When appraising the introduction of the article, you should ask yourself whether the article answers the main question it poses. Alongside this look at the date of publication, generally you want works to be within the past 5 years, unless they are seminal works which have strongly influenced subsequent developments in the field. Identify whether the journal in which the article was published is peer reviewed and importantly whether a hypothesis has been presented. Be objective, concise, and coherent in your presentation of this information.

Once you have appraised the introduction you can move onto the methods (or the body of the text if the work is not of a scientific or experimental nature). To effectively appraise the methods, you need to examine whether the approaches used to draw conclusions (i.e., the methodology) is appropriate for the research question, or overall topic. If not, indicate why not, in your appraisal, with evidence to back up your reasoning. Examine the sample population (if there is one), or the data gathered and evaluate whether it is appropriate, sufficient, and viable, before considering the data collection methods and survey instruments used. Are they fit for purpose? Do they meet the needs of the paper? Again, your arguments should be backed up by strong, viable sources that have credible foundations and origins.

One of the most significant areas of appraisal is the results and conclusions presented by the authors of the work. In the case of the results, you need to identify whether there are facts and figures presented to confirm findings, assess whether any statistical tests used are viable, reliable, and appropriate to the work conducted. In addition, whether they have been clearly explained and introduced during the work. In regard to the results presented by the authors you need to present evidence that they have been unbiased and objective, and if not, present evidence of how they have been biased. In this section you should also dissect the results and identify whether any statistical significance reported is accurate and whether the results presented and discussed align with any tables or figures presented.

The final element of the body text is the appraisal of the discussion and conclusion sections. In this case there is a need to identify whether the authors have drawn realistic conclusions from their available data, whether they have identified any clear limitations to their work and whether the conclusions they have drawn are the same as those you would have done had you been presented with the findings.

The conclusion of the appraisal should not introduce any new information but should be a concise summing up of the key points identified in the body text. The conclusion should be a condensation (or precis) of all that you have already written. The aim is bringing together the whole paper and state an opinion (based on evaluated evidence) of how valid and reliable the paper being appraised can be considered to be in the subject area. In all cases, you should reference and cite all sources used. To help you achieve a first class critical appraisal we have put together some key phrases that can help lift you work above that of others.

Key Phrases for a Critical Appraisal

- Whilst the title might suggest

- The focus of the work appears to be…

- The author challenges the notion that…

- The author makes the claim that…

- The article makes a strong contribution through…

- The approach provides the opportunity to…

- The authors consider…

- The argument is not entirely convincing because…

- However, whilst it can be agreed that… it should also be noted that…

- Several crucial questions are left unanswered…

- It would have been more appropriate to have stated that…

- This framework extends and increases…

- The authors correctly conclude that…

- The authors efforts can be considered as…

- Less convincing is the generalisation that…

- This appears to mislead readers indicating that…

- This research proves to be timely and particularly significant in the light of…

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Critical Appraisal tools

Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers in order to establish:

- Does this study address a clearly focused question ?

- Did the study use valid methods to address this question?

- Are the valid results of this study important?

- Are these valid, important results applicable to my patient or population?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, you can save yourself the trouble of reading the rest of it.

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples.

Critical Appraisal Worksheets

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostics Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet

- IPD Review Sheet

Chinese - translated by Chung-Han Yang and Shih-Chieh Shao

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostic Study Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognostic Critical Appraisal Sheet

- RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

- IPD reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Sheet

German - translated by Johannes Pohl and Martin Sadilek

- Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Therapy / RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

Lithuanian - translated by Tumas Beinortas

- Systematic review appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Diagnostic accuracy appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Prognostic study appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- RCT appraisal sheets Lithuanian (PDF)

Portugese - translated by Enderson Miranda, Rachel Riera and Luis Eduardo Fontes

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Diagnostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Prognostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – RCT Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Evaluation of Individual Participant Data Worksheet

- Portuguese – Qualitative Studies Evaluation Worksheet

Spanish - translated by Ana Cristina Castro

- Systematic Review (PDF)

- Diagnosis (PDF)

- Prognosis Spanish Translation (PDF)

- Therapy / RCT Spanish Translation (PDF)

Persian - translated by Ahmad Sofi Mahmudi

- Prognosis (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (MS-Word)

- Educational Prescription Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

Explanations & Examples

- Pre-test probability

- SpPin and SnNout

- Likelihood Ratios

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Critical appraisal of the literature. Why do we care?

Avaliação crítica da literatura. por que nos importamos, juliana carvalho ferreira, cecilia maria patino.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Issue date 2018 Nov-Dec.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

PRACTICAL SCENARIO

Investigators conducted a noninferiority, double-blind clinical trial involving 4,215 patients with mild asthma, randomly assigned to receive twice-daily placebo plus budesonide-formoterol used as needed vs. maintenance therapy with twice-daily budesonide plus terbutaline as needed. They found that budesonide-formoterol used as needed was noninferior to twice-daily budesonide concerning the rate of severe asthma exacerbations but was inferior in controlling symptoms. 1

HOW TO CRITICALLY APPRAISE THE MEDICAL LITERATURE

As clinicians, when we read a paper reporting the benefit of a given intervention, we make a judgment regarding whether we should use those results to inform how we care for our patients. In our example, after reading the paper, we ask ourselves: should a clinician working in a public hospital in Brazil start prescribing budesonide-formoterol as needed rather than maintenance budesonide for her patients with mild asthma? What criteria should guide her decision to adopt a new intervention? One may think that if a study is published in a high-impact, peer-reviewed journal, it is of high quality and should therefore be used to guide clinical decision making. However, if the population included in the study or the context is different from her population, that may not be the case. Therefore, examining the external validity of a study is critical to informing local practice.

Other commonly used criteria are related to evaluating the quality of the evidence by evaluating the type of study design used. The pyramid of evidence puts meta-analyses at the top (as providing the highest quality of evidence), followed by systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials; then come observational studies (cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies); whereas case reports and case series are categorized as offering the lowest quality of evidence. Although those criteria may be helpful, making a detailed appraisal of a paper, taking into account aspects other than the study design, is a skill that researchers and clinicians can learn and apply when reading the literature.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers that helps us establish if the results are valid and if they could be used to inform medical decision in a given local population and context. There are several published guidelines for critically appraising the scientific literature, most of which are structured as checklists and address specific study designs. 2 Although different appraisal tools may vary, the general structure is shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. How to appraise medical literature.

The items in Table 1 are a guide to appraising the content of a research article. There are also guidelines for appraising the quality of reporting of health research which focus on the reporting accuracy and completeness of research studies. 3 These two types of appraisal (content and reporting) are complementary and should both be used, because it is possible that a research paper has high reporting quality but is not relevant to the context in question.

KEY MESSAGE

Critical appraisal of the literature is an essential skill for researchers and clinicians, and there are easy-to-use guidelines. Clinicians have the responsibility to help patients make health-related decisions, which should be based on high-quality, valid research that is applicable in their context.

- 1. Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O’Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Zhong N, Keen C, et al. As-Needed Budesonide-Formoterol versus Maintenance Budesonide in Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1877–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715275. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . Oxford (UK): CASP; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Equator network . Oxford (UK): Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford; https://www.equator-network.org [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (498.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Harnessing nature-based solutions for economic recovery: A systematic review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Nature-based Solutions Initiative, Department of Biology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Nature-based Solutions Initiative, Department of Biology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Economics, Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute for New Economic Thinking, Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Roles Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Instituto de Montaña, Lima, Peru

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Nature-based Solutions Initiative, Department of Biology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- Alexandre Chausson,

- Alison Smith,

- Ryne Zen-Zhi Reger,

- Brian O’Callaghan,

- Yadira Mori Clement,

- Florencia Zapata,

- Nathalie Seddon

- Published: October 28, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000281

- Reader Comments