Doblaje Wiki

Hola, ¡bienvenido a Doblaje Wiki!. Antes de iniciar te pedimos de favor que te tomes un poco de tiempo para leer el reglamento de la comunidad y de esta manera, sepas qué hacer y qué no hacer en materia de ediciones de páginas entre otros.

Por favor, ¡deja un mensaje a alguno de los administradores disponibles si podemos ayudarte con cualquier cosa!.

- Películas de Universal Studios

- Películas de IFC Films

- Películas de 2010s

- Doblajes de 2010s

- Películas de 2015

- Películas basadas en hechos reales

- Drama biográfico

- Drama histórico

- Doblajes exclusivos de Estados Unidos

- Películas transmitidas por HBO

- Películas transmitidas por Showtime

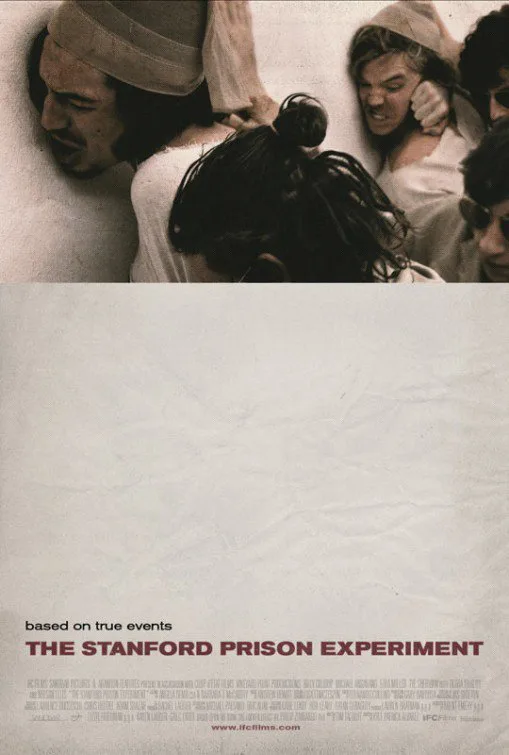

The Stanford Prison Experiment

- Comentarios (0)

The Stanford Prison Experiment es una película del 2015 basada en el libro "The Lucifer Effect", dirigida por Kyle Patrick Alvarez y escrita por Tim Talbott y Philip Zimbardo . La película está protagonizada por Billy Crudup , Michael Angarano y Moises Arias .

Datos técnicos [ ]

| Puesto | Versión | |

|---|---|---|

| 1ra versión | 2da versión | |

| Título de la versión doblada | El experimento de la cárcel de Stanford | Experimento en la prisión de Stanford |

| Lugar | México | Venezuela |

| Estudio de doblaje | ||

| Dirección del doblaje | ||

| Producción | Rodrigo Castillo | |

| Versión al Español Latinoamericano | ||

Reparto [ ]

| Personaje | Actor original | Actor de doblaje | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal | Showtime | ||

| Dr. Philip Zimbardo | |||

| Christopher Archer | |||

| Daniel Culp / 8612 | |||

| Peter Mitchell / 819 | |||

| Dra. Christina Maslach | |||

| Jeff Jansen / 1037 | |||

| Paul Vogel | |||

| Mike Penny | |||

| Tom Thompson / 2093 | Chris Sheffield | ||

| Jacob Harding | |||

| Hubbie Whitlow / 7258 | Brett Davern | ||

| Karl Vandy | |||

| Gavin Lee / 3401 | |||

| Matthew Townshend | James Frecheville | ||

| Jesse Fletcher | |||

| Paul Beattie / 5704 | Jesse Carere | ||

| Jim Randall / 4325 | Jack Kilmer | ||

| Kyle Parker | |||

| Prisionero 416 | |||

| Jerry Sherman / 5486 | |||

| Anthony Carroll | |||

| Marshall Lovett | |||

| John Lovett | |||

| Padre MacAllister | Albert Malafronte | ||

| Sra. Mitchell | Kate Butler | ||

| Andrew Ceros | |||

| Mary Ann | Danielle Lauder | ||

| Henry Ward | |||

| Warren | Jim Klock | ||

| Jim Cook | Fred Ochs | ||

| Título y letreros | N/A | ||

- 1 Sonic 3: La película

- 3 Ranma ½ (2024)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Stanford Prison Experiment

- Participants

- Setting and Procedure

In August of 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues created an experiment to determine the impacts of being a prisoner or prison guard. The Stanford Prison Experiment, also known as the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, went on to become one of the best-known studies in psychology's history —and one of the most controversial.

This study has long been a staple in textbooks, articles, psychology classes, and even movies. Learn what it entailed, what was learned, and the criticisms that have called the experiment's scientific merits and value into question.

Purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment

Zimbardo was a former classmate of the psychologist Stanley Milgram . Milgram is best known for his famous obedience experiment , and Zimbardo was interested in expanding upon Milgram's research. He wanted to further investigate the impact of situational variables on human behavior.

Specifically, the researchers wanted to know how participants would react when placed in a simulated prison environment. They wondered if physically and psychologically healthy people who knew they were participating in an experiment would change their behavior in a prison-like setting.

Participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment

To carry out the experiment, researchers set up a mock prison in the basement of Stanford University's psychology building. They then selected 24 undergraduate students to play the roles of both prisoners and guards.

Participants were chosen from a larger group of 70 volunteers based on having no criminal background, no psychological issues , and no significant medical conditions. Each volunteer agreed to participate in the Stanford Prison Experiment for one to two weeks in exchange for $15 a day.

Setting and Procedures

The simulated prison included three six-by-nine-foot prison cells. Each cell held three prisoners and included three cots. Other rooms across from the cells were utilized for the jail guards and warden. One tiny space was designated as the solitary confinement room, and yet another small room served as the prison yard.

The 24 volunteers were randomly assigned to either the prisoner or guard group. Prisoners were to remain in the mock prison 24 hours a day during the study. Guards were assigned to work in three-man teams for eight-hour shifts. After each shift, they were allowed to return to their homes until their next shift.

Researchers were able to observe the behavior of the prisoners and guards using hidden cameras and microphones.

Results of the Stanford Prison Experiment

So what happened in the Zimbardo experiment? While originally slated to last 14 days, it had to be stopped after just six due to what was happening to the student participants. The guards became abusive and the prisoners began to show signs of extreme stress and anxiety .

It was noted that:

- While the prisoners and guards were allowed to interact in any way they wanted, the interactions were hostile or even dehumanizing.

- The guards began to become aggressive and abusive toward the prisoners while the prisoners became passive and depressed.

- Five of the prisoners began to experience severe negative emotions , including crying and acute anxiety, and had to be released from the study early.

Even the researchers themselves began to lose sight of the reality of the situation. Zimbardo, who acted as the prison warden, overlooked the abusive behavior of the jail guards until graduate student Christina Maslach voiced objections to the conditions in the simulated prison and the morality of continuing the experiment.

One possible explanation for the results of this experiment is the idea of deindividuation , which states that being part of a large group can make us more likely to perform behaviors we would otherwise not do on our own.

Impact of the Zimbardo Prison Experiment

The experiment became famous and was widely cited in textbooks and other publications. According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, the Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated the powerful role that the situation can play in human behavior.

Because the guards were placed in a position of power, they began to behave in ways they would not usually act in their everyday lives or other situations. The prisoners, placed in a situation where they had no real control , became submissive and depressed.

In 2011, the Stanford Alumni Magazine featured a retrospective of the Stanford Prison Experiment in honor of the experiment’s 40th anniversary. The article contained interviews with several people involved, including Zimbardo and other researchers as well as some of the participants.

In the interviews, Richard Yacco, one of the prisoners in the experiment, suggested that the experiment demonstrated the power that societal roles and expectations can play in a person's behavior.

In 2015, the experiment became the topic of a feature film titled The Stanford Prison Experiment that dramatized the events of the 1971 study.

Criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment

In the years since the experiment was conducted, there have been a number of critiques of the study. Some of these include:

Ethical Issues

The Stanford Prison Experiment is frequently cited as an example of unethical research. It could not be replicated by researchers today because it fails to meet the standards established by numerous ethical codes, including the Code of Ethics of the American Psychological Association .

Why was Zimbardo's experiment unethical?

Zimbardo's experiment was unethical due to a lack of fully informed consent, abuse of participants, and lack of appropriate debriefings. More recent findings suggest there were other significant ethical issues that compromise the experiment's scientific standing, including the fact that experimenters may have encouraged abusive behaviors.

Lack of Generalizability

Other critics suggest that the study lacks generalizability due to a variety of factors. The unrepresentative sample of participants (mostly white and middle-class males) makes it difficult to apply the results to a wider population.

Lack of Realism

The Zimbardo Prison Experiment is also criticized for its lack of ecological validity. Ecological validity refers to the degree of realism with which a simulated experimental setup matches the real-world situation it seeks to emulate.

While the researchers did their best to recreate a prison setting, it is simply not possible to perfectly mimic all the environmental and situational variables of prison life. Because there may have been factors related to the setting and situation that influenced how the participants behaved, it may not truly represent what might happen outside of the lab.

Recent Criticisms

More recent examination of the experiment's archives and interviews with participants have revealed major issues with the research method , design, and procedures used. Together, these call the study's validity, value, and even authenticity into question.

These reports, including examinations of the study's records and new interviews with participants, have also cast doubt on some of its key findings and assumptions.

Among the issues described:

- One participant suggested that he faked a breakdown so he could leave the experiment because he was worried about failing his classes.

- Other participants also reported altering their behavior in a way designed to "help" the experiment .

- Evidence suggests that the experimenters encouraged the guards' behavior and played a role in fostering the abusive actions of the guards.

In 2019, the journal American Psychologist published an article debunking the famed experiment. It detailed the study's lack of scientific merit and concluded that the Stanford Prison Experiment was "an incredibly flawed study that should have died an early death."

In a statement posted on the experiment's official website, Zimbardo maintains that these criticisms do not undermine the main conclusion of the study—that situational forces can alter individual actions both in positive and negative ways.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is well known both inside and outside the field of psychology . While the study has long been criticized for many reasons, more recent criticisms of the study's procedures shine a brighter light on the experiment's scientific shortcomings.

Stanford University. About the Stanford Prison Experiment .

Stanford Prison Experiment. 2. Setting up .

Sommers T. An interview with Philip Zimbardo . The Believer.

Ratnesar R. The menace within . Stanford Magazine.

Jabbar A, Muazzam A, Sadaqat S. An unveiling the ethical quandaries: A critical analysis of the Stanford Prison Experiment as a mirror of Pakistani society . J Bus Manage Res . 2024;3(1):629-638.

Horn S. Landmark Stanford Prison Experiment criticized as a sham . Prison Legal News .

Bartels JM. The Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory psychology textbooks: A content analysis . Psychol Learn Teach . 2015;14(1):36-50. doi:10.1177/1475725714568007

American Psychological Association. Ecological validity .

Blum B. The lifespan of a lie . Medium .

Le Texier T. Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment . Am Psychol . 2019;74(7):823-839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401

Stanford Prison Experiment. Philip Zimbardo's response to recent criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

What the Stanford Prison Experiment Taught Us

In August of 1971, Dr. Philip G. Zimbardo of Stanford University in California conducted what is widely considered one of the most influential experiments in social psychology to date. Made into a New York Times best seller in 2007 ( The Lucifer Effect ) and a major motion picture in 2015 ( The Stanford Prison Experiment ), the Stanford Prison Experiment has integrated itself not only into the psychology community but also popular culture. The events that occurred within this experiment, though disturbing, have given many people insight into just how much a situation can affect behavior. They have also caused many to ponder the nature of evil. How disturbing was it? Well, the proposed two-week experiment was terminated after just six days, due to alarming levels of mistreatment and brutality perpetrated on student “prisoners” by fellow student “guards.”

The study aimed to test the effects of prison life on behavior and wanted to tackle the effects of situational behavior rather than just those of disposition. After placing an ad in the newspaper, Zimbardo selected 24 mentally and physically healthy undergraduate students to participate in the study. The idea was to randomly assign nine boys to be prisoners, nine to be guards, and six to be extras should they need to make any replacements. After randomly assigning the boys, the nine deemed prisoners were “arrested” and promptly brought into a makeshift Stanford County Prison, which was really just the basement of the Stanford Psychology Department building. Upon arrival, the boys’ heads were shaved, and they were subjected to a strip search as well as delousing (measures taken to dehumanize the prisoners). Each prisoner was then issued a uniform and a number to increase anonymity. The guards who were to be in charge of the prisoners were not given any formal training; they were to make up their own set of rules as to how they would govern their prison.

Over the course of six days, a shocking set of events unfolded. While day one seemed to go by without issue, on the second day there was a rebellion, causing guards to spray prisoners with a fire extinguisher in order to force them further into their cells. The guards took the prisoners’ beds and even utilized solitary confinement. They also began to use psychological tactics, attempting to break prisoner solidarity by creating a privilege cell. With each member of the experiment, including Zimbardo, falling deeper into their roles, this “prison” life quickly became a real and threatening situation for many. Thirty-six hours into the experiment, prisoner #8612 was released on account of acute emotional distress, but only after (incorrectly) telling his prison-mates that they were trapped and not allowed to leave, insisting that it was no longer an experiment. This perpetuated a lot of the fears that many of the prisoners were already experiencing, which caused prisoner #819 to be released a day later after becoming hysterical in Dr. Zimbardo’s office.

The guards got even crueler and more unusual in their punishments as time progressed, forcing prisoners to participate in sexual situations such as leap-frogging each other’s partially naked bodies. They took food privileges away and forced the prisoners to insult one another. Even the prisoners fell victim to their roles of submission. At a fake parole board hearing, each of them was asked if they would forfeit all money earned should they be allowed to leave the prison immediately. Most of them said yes, then were upset when they were not granted parole, despite the fact that they were allowed to opt out of the experiment at any time. They had fallen too far into submissive roles to remember, or even consider, their rights.

On the sixth day, Dr. Zimbardo closed the experiment due to the continuing degradation of the prisoners’ emotional and mental states. While his findings were, at times, a terrifying glimpse into the capabilities of humanity, they also advanced the understanding of the psychological community. When it came to the torture done at Abu Ghraib or the Rape of Nanjing in China, Zimbardo’s findings allowed for psychologists to understand evil behavior as a situational occurrence and not always a dispositional one.

Learn More About This Topic

- How does a situation cause violent behavior?

- What is social psychology?

Know a mentally disturbed person who doesn’t think much of others? Make sure you apply the right epithet.

Recommended from the web

- Visit the Stanford Prison Experiment official website

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Stanford Prison Experiment

- Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment

Carried out August 15-21, 1971 in the basement of Jordan Hall, the Stanford Prison Experiment set out to examine the psychological effects of authority and powerlessness in a prison environment. The study, led by psychology professor Philip G. Zimbardo, recruited Stanford students using a local newspaper ad. Twenty-four students were carefully screened and randomly assigned into groups of prisoners and guards. The experiment, which was scheduled to last 1-2 weeks, ultimately had to be terminated on only the 6th day as the experiment escalated out of hand when the prisoners were forced to endure cruel and dehumanizing abuse at the hands of their peers. The experiment showed, in Dr. Zimbardo’s words, how “ordinary college students could do terrible things.”

Researchers: Philip Zimbardo, Craig Haney, W. Curtis Banks, David Jaffe

Primary Consultant: Carlo Prescott

Additional research assistance, clerical assistance, and critical information provided by: Carolyn Burkhart, David Gorchoff, Christina Maslach, Susan Phillips, Anne Riecken, Cathy Rosenfeld, Lee Ross, Rosanne Saussotte, and Greg White.

Prison constructed by: Ralph Williams, Bob Zeiss, and Don Johann

Police cooperation through: James C. Zurcher, Chief of Police, City of Palo Alto; Joseph Sparaco, Officer, Police Department, City of Palo Alto; and Marvin Herrington, Director of Police, Stanford University

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, twenty-four male students are selected to take on randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. In 1971, twenty-four male students are selected to take on randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. In 1971, twenty-four male students are selected to take on randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building.

- Kyle Patrick Alvarez

- Tim Talbott

- Philip Zimbardo

- Ezra Miller

- Tye Sheridan

- Billy Crudup

- 130 User reviews

- 91 Critic reviews

- 67 Metascore

- 4 wins & 3 nominations

Top cast 38

- Daniel Culp …

- Peter Mitchell …

- Dr. Philip Zimbardo

- Dr. Christina Maslach

- Christopher Archer

- Anthony Carroll

- John Lovett

- Gavin Lee …

- Prisoner 416

- Jerry Sherman …

- Jeff Jansen …

- Jesse Fletcher

- Kyle Parker

- Paul Beattie …

- Hubbie Whitlow …

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia Although never mentioned in the movie, the real life experiment was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research and was of interest to both the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps as an investigation into the causes of conflict between military guards and prisoners.

- Goofs When Dr. Zimbardo speaks with his colleague, the colleague says that he will see him at the beginning of the semester. Stanford does not have semesters; rather, it has a quarter academic calendar.

Daniel Culp : I know you're a nice guy.

Christopher Archer : So why do you hate me?

Daniel Culp : Because I know what you can become.

- Connections Featured in WatchMojo: Top 10 Creepiest Historic Events That Are Scarier than Horror Movies (2020)

User reviews 130

- boboceaelena

- Feb 20, 2021

- How long is The Stanford Prison Experiment? Powered by Alexa

- July 17, 2015 (United States)

- United States

- Official site

- Untitled Stanford Prison Experiment Project

- Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA

- Coup d'Etat Films

- Sandbar Pictures

- Abandon Pictures

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Jul 19, 2015

Technical specs

- Runtime 2 hours 2 minutes

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Stanford prison experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment es una película del 2015 basada en el libro "The Lucifer Effect", dirigida por Kyle Patrick Alvarez y escrita por Tim Talbott y Philip Zimbardo. La película está protagonizada por Billy Crudup , Michael Angarano y Moises Arias.

L'experiment de la presó de Stanford és un conegut estudi psicològic sobre la influència d'un ambient extrem, la vida a la presó, en les conductes desenvolupades per les persones, dependent dels rols socials que desenvolupaven (captiu, guàrdia). Va ser dut a terme el 1971 per un equip d'investigadors liderat per Philip Zimbardo de la Universitat de Stanford.

The Stanford prison experiment ( SPE) was a psychological experiment conducted in August 1971. It was a two-week simulation of a prison environment that examined the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors. Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo led the research team who administered the study.

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) was a psychology experiment to see the effects of becoming a prisoner or a prison guard on human behaviour and psychology. [1] The experiment ran from 15 to 21 August 1971. It was led by Dr Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is a 2015 American docudrama psychological thriller film directed by Kyle Patrick Alvarez, written by Tim Talbott, and starring Billy Crudup, Michael Angarano, Ezra Miller, Tye Sheridan, Keir Gilchrist, Olivia Thirlby, and Nelsan Ellis.The plot concerns the 1971 Stanford prison experiment, conducted at Stanford University under the supervision of psychology ...

Stanford Prison Experiment, a social psychology study in which college students became prisoners or guards in a simulated prison environment.The experiment, funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, took place at Stanford University in August 1971. It was intended to measure the effect of role-playing, labeling, and social expectations on behaviour over a period of two weeks.

The Stanford Prison Experiment: A Film by Kyle Patrick Alvarez. The Lucifer Effect: New York Times Best-Seller by Philip Zimbardo. Welcome to the official Stanford Prison Experiment website, which features extensive information about a classic psychology experiment that inspired an award-winning movie, New York Times bestseller, and documentary ...

The Stanford marshmallow experiment was a study on delayed gratification in 1970 led by psychologist Walter Mischel, a professor at Stanford University. [ 1] In this study, a child was offered a choice between one small but immediate reward, or two small rewards if they waited for a period of time. During this time, the researcher left the ...

Philip George Zimbardo (/ z ɪ m ˈ b ɑːr d oʊ /; born March 23, 1933) is an American psychologist and a professor emeritus at Stanford University. [1] He became known for his 1971 Stanford prison experiment, which was later severely criticized for both ethical and scientific reasons.He has authored various introductory psychology textbooks for college students, and other notable works ...

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a psychological experiment conducted in August 1971.It was a two-week simulation of a prison environment that examined the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors. Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo led the research team who administered the study. [1]

In August of 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues created an experiment to determine the impacts of being a prisoner or prison guard. The Stanford Prison Experiment, also known as the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, went on to become one of the best-known studies in psychology's history —and one of the most controversial.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. PrisonExp.org. In August of 1971, Dr. Philip G. Zimbardo of Stanford University in California conducted what is widely considered one of the most influential experiments in social psychology to date. Made into a New York Times best seller in 2007 ( The Lucifer Effect) and a major motion picture in 2015 ...

Stanfordexperimentet. Två "vakter" med en fånge med ögonbindel. En grupp "fångar" i en cell. "Fångar" och Philip Zimbardo. En "fånge" bryter ihop. Stanfordexperimentet var ett socialpsykologiskt experiment som sades undersöka de psykologiska effekterna av upplevd makt, med fokus på kampen mellan fångar och fångvaktare. [ 1]

Das Stanford-Prison-Experiment (deutsch: das Stanford-Gefängnis-Experiment) war ein psychologisches Experiment zur Erforschung menschlichen Verhaltens unter den Bedingungen der Gefangenschaft, speziell unter den Feldbedingungen des echten Gefängnislebens. Der Versuch wurde 1971 von den US-amerikanischen Psychologen Philip Zimbardo, Craig ...

About. Carried out August 15-21, 1971 in the basement of Jordan Hall, the Stanford Prison Experiment set out to examine the psychological effects of authority and powerlessness in a prison environment. The study, led by psychology professor Philip G. Zimbardo, recruited Stanford students using a local newspaper ad. Twenty-four students were ...

On a quiet Sunday morning in August, a Palo Alto, California, police car swept through the town picking up college students as part of a mass arrest for violation of Penal Codes 211, Armed Robbery, and Burglary, a 459 PC. The suspect was picked up at his home, charged, warned of his legal rights, spread-eagled against the police car, searched ...

The Stanford prison experiment was a psychological experiment conducted in the summer of 1971. It was a two-week simulation of a prison environment that examined the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors. Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo led the research team who administered the study. Participants were recruited from the local ...

The Stanford Prison Experiment: Directed by Kyle Patrick Alvarez. With Billy Crudup, Michael Angarano, Moises Arias, Nicholas Braun. In 1971, twenty-four male students are selected to take on randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building.

Experimentul Stanford (în original, în engleză Stanford Prison Experiment) a fost un experiment psihologic care a produs câteva descoperiri senzaționale în domeniul psihologiei umane.S-a descoperit o schimbare radicală a comportamentului individului în condițiile de viață dintr-un penitenciar.Experimentul a fost inițiat în anul 1971 de psihologul american Philip Zimbardo, de la ...

The following 24 files are in this category, out of 24 total. Emanuel Celler letter to Philip Zimbardo.pdf 1,272 × 1,650, 2 pages; 5.29 MB. Plaque Dedicated to the Location of the Stanford Prison Experiment (2).jpg 324 × 214; 10 KB. Plaque Dedicated to the Location of the Stanford Prison Experiment.jpg 543 × 350; 84 KB.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is an utterly gripping, chilling narrative... Oct 4, 2021. It's an important film to watch for anyone interested in criminal justice, social justice or simply the ...

Stanford-gevangenisexperiment. Het Stanford-gevangenisexperiment is een spraakmakend sociaal-psychologisch experiment dat in 1971 werd uitgevoerd in de kelders van de Universiteit van Stanford. Het experiment was opgezet door Philip Zimbardo en werd door hem geduid als een bewijs van situationisme ("de externe situatie bepaalt persoonsgedrag").

Stanfordský vězeňský experiment. Takzvaný stanfordský vězeňský experiment je v psychologii jedním z nejznámějších a nejkontroverznějších experimentů. Byl řízen a proveden roku 1971 americkým psychologem Philipem Zimbardem. Spočíval v uzavření určitého počtu dobrovolníků do uměle vytvořeného vězení v rolích ...

The best scene in "The Stanford Prison Experiment" deals with an actual prisoner and serves to highlight my disdain for how the film trades emotion and details for exploitative shocks. The fantastic Nelsan Ellis (last seen in " Get On Up ") plays Jesse, an ex-con brought in by Zimbardo's team as an expert witness to their proceedings.

The Stanford prison experiment was a study of the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. The experiment was conducted in 1971 by a team of researchers led by Psychology Professor Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University.Twenty-four undergraduates were selected out of 70 to play the roles of both guards and prisoners and live in a mock prison in the basement of the Stanford ...